RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

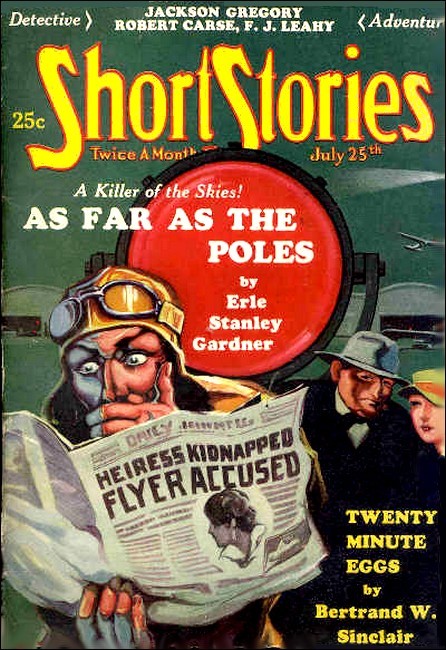

Short Stories, 25 July 1933, with "Was It Murder?"

"The Baronets of Mertonbridge Hall do not murder

their

wives," said the butler. Did he know what he was

talking about?

I DO not profess to explain what I am going to set down. I hold no positive opinion on things psychic, one way or the other. Men of unassailable integrity have given the world their experience on such matters, which are open for all to read, and my contribution can add nothing to the wealth of material already collected. Nevertheless, for what it is worth, I am committing it to paper. I do it for my own satisfaction only: For reasons which will be obvious, these words must never see the light of day in print. Because they either tell of a coincidence so amazing as to be well-nigh incredible or else Sir Bryan Mertonbridge, sixteenth Baronet, of Mertonbridge Hall, Sussex, is a cold-blooded murderer. And, since his house-parties for Goodwood are famous throughout the county it were madness for a humble bank manager to bring such an accusation against him, when proof is impossible.

It happened four years ago, but let it not be thought that time has clouded my memory. The incidents of that night in June are as clear in my mind as if they had occurred yesterday. Sometimes I wake now with the woman's last dying scream ringing in my ears, and, jumping out of bed, I pace up and down my room, asking myself again and again the same old question. Was it a coincidence or was it not?

THE sea mist started to blow over the Downs about eight

o'clock on the evening when it took place. It came like a dense

white wall, blotting out the surrounding landscape, and covering

the windscreen with a film of moisture more difficult to see

through than heavy rain. My destination was Brighton, but, never

dreaming that such a mist would come down on me, I had left the

main coast road, and had taken a narrow inland one that wound

along the foot of the Downs, connecting up a few scattered farms

and hamlets that still escaped the daily ordeal of the charge of

the motor heavy brigade. The road was good but narrow, with a

ditch on each side, so that caution was necessary owing to the

mist making the grass slippery. The trouble, however, was the bad

visibility, and, after a time, my rate of progress was reduced to

less than ten miles an hour. Another difficulty was due to

indifferent signposting, the few that there were showing only the

next village and no large town.

I had been creeping along for about a quarter of an hour when I came to four cross-roads, and, getting out of the car, I approached the signpost, one arm of which fortunately indicated Worthing. Once on the main road, things might be better, so I decided to take it. But having slightly overshot the mark, I had to back the car and it was then the mishap occurred. I reversed too far, and the back wheels skidded into the ditch.

At first I thought nothing of it, but after repeated attempts to get her out, which only resulted in the wheels spinning round, I began to grow uneasy. And then came the final blow. There was a sharp click, and the wheels ceased to move, though the engine was still running in gear. Either the cardan shaft, or one arm of the back axle, had broken. The car was helpless: it was now a question of being towed out.

I lit a cigarette and sized up the position. My map was a small-scale one, embracing the whole of England, and I knew the crossroads where I was would not be marked. The light was failing rapidly: worse still, the sea mist was beginning to turn into genuine rain. My chances of finding a garage, even if I knew where to look for one, which could send out a breakdown gang at that hour, were remote. In fact, it was evident that the car would have to remain where it was till the morning. But I failed to see why I should keep it company. Sooner or later, I must come to some habitation of sorts, where I could be directed to an inn, or whose owner would perhaps put me up for the night. Anyway, I could not stop where I was, so leaving the car in the ditch, I took the road for Worthing.

FOR twenty minutes I trudged along without meeting a soul or

seeing the sign of a house. The rain was now pouring down, and,

having no mackintosh, I was rapidly becoming wet to the skin. And

then, just as I was beginning to despair of finding anything, the

road swerved sharply to the right, and I saw a pair of heavy iron

gates in front of me. Beyond them was a small house—evidently the

lodge to some big property.

It was in complete darkness, but at least it was something made of bricks and mortar, and, pushing open one of the gates, I approached it and knocked on the door. There was no answer, and, after a while, I realized it was empty. I went all round it in the hope of finding a window unlatched. Everything was tight shut; short of breaking a pane, there was no hope of getting in.

By that time the water was squelching in my shoes, and I was seriously cogitating as to whether it would not be worth while to smash a window, when it struck me that, if this was a lodge, the big house must be fairly close at hand. So once again I started off up the drive: no one could refuse a dog shelter on such a night.

It was almost dark, and, save for my footsteps on the gravel and the mournful dripping of the water from the trees, no sound broke the silence. Was I never going to reach the house?

At length the trees bordering the drive stopped abruptly, and there loomed up ahead of me the outlines of a large mansion. But even as I quickened my pace, my heart began to sink, for, just as at the lodge, I could see no light in any window. Surely, I reflected, this could not be empty, too.

I FOUND the front door. It was of oak, studded with iron

bolts, and, by the light of a match, I saw a heavy, old-fashioned

bell-pull. For a few moments I hesitated; then, taking my courage

in both hands, I gave it a sharp pull, only to jump nearly out of

my skin the next second. For the bell rang just above my head,

and the noise was deafening. Gradually it died away, and, in the

silence that followed, I listened intently. If there was anyone

in the house, surely they must have heard it; to me the row had

seemed enough to wake the dead. But the minutes passed, and no

one came. I realized that this house was empty, too.

Cursing angrily, I turned away; there was nothing for it but to foot it back again. And then I saw a thing which pulled me up sharp; a small window to one side of the front door was open. I thought of that foul walk along the drive, and I made up my mind without more ado. Ten seconds later I was inside the house.

The room in which I found myself was a small cloak-room. Hats and coats hung on pegs around the walls: two shooting-sticks and a bag of golf-clubs stood in one corner. So much I saw by the light of a match, but another more welcome object caught my eye—an electric-light switch. I had already made up my mind that, should anyone appear, I would make no attempt to conceal myself, but would say frankly who I was, and my reasons for breaking in. And so I had no hesitation in turning on the light as I left and walked along a passage which led from the room. A door was at the end of it, and I pushed it open, to find myself in a vast paneled hall.

Holding the door open to get the benefit of the light from the cloak-room I saw more switches beside me, and in a moment the place was brightly illuminated. It was even bigger than I had at first thought. At one end, opposite the front door, was a broad staircase, which branched both ways after the first flight. Facing me was a large open fireplace with logs arranged in it—logs, which, to my joy, I saw were imitation ones fitted for an electric fire. In the middle stood a long refectory table, whilst all round the walls there hung paintings of men in the dress of bygone days. The family portrait gallery; evidently the house belonged to a man of ancient lineage. All that, however, could wait; my first necessity was to get moderately dry.

I turned off some of the lights and crossed to the fireplace, where I found the heat switch without difficulty. By this time I was sure that the house was empty, and, having returned to the cloak-room to get an overcoat, I took off my clothes and sat down in an armchair in front of the glowing logs.

(I know these small details seem irrelevant, but I am putting them down to prove that my recollection of that night is still perfect.)

The hall was in semi-darkness. Two suite of armor standing sentinel on either side of the staircase gleamed red in the light of the fire: an overhead cluster threw a pool of white radiance on the polished table in the center. Outside the rain still beat down pitilessly, and as I looked at my steaming clothes I thanked Heaven for that open window. And after a while I began to feel drowsy. A leaden weight settled on my eyelids; my head dropped forward; I fell asleep.

SUDDENLY, as so often happens when one is beat, I was wide

awake again. Something had disturbed me—some noise, and as I

listened intently, I heard it again. It was the sound of wheels

on the drive outside, and of horses. It was as if a coach and

four were being driven up to the door, but the strangeness of

such a conveyance at that hour of the night did not strike mc for

the moment. I was far too occupied in trying to think what excuse

I was going to make for my presence in such unconventional garb.

And then, even as with a jangling of bits, the vehicle pulled up

by the front door, I realized to my amazement, that my clothes

had been removed.

I tried to puz2le it out—to collect myself, but before I could think what I was going to say, the door was flung open and a great gust of wind came sweeping in, making the candles on the table gutter. Candles! Who had put candles there, and turned out the electric light? And who had laid supper?

I looked again towards the door; a woman had come in, and my embarrassment increased. She swept towards the table, and stood there, one hand resting on it, staring straight in front of her. Of me she took no notice whatever, though it seemed inconceivable that she had not seen me. And then, as she remained there motionless, my amazement grew. Her dress was that of the Stuart period.

The front door shut, and a man came into the circle of light. Magnificently handsome, with clean-cut aquiline features, he was dressed as the typical Cavalier of King Charles' time. And as he stood, drawing off his driving gauntlets, I realized what had happened. He was the owner of the house, and there had been a fancy-dress ball. Still, I was glad I had a man to explain things to.

He threw his gloves into a chair, and came straight towards me. And the words of explanation were trembling on my tongue, when he knelt down almost at my feet, and stretched out his hands towards the blaze. He seemed oblivious of my presence, but what was even more amazing was the fire itself. For now great flames roared up the chimney from giant logs that blazed fiercely.

I glanced again at the woman; she had not moved. But on her face had come an expression that baffled me. Her eyes were resting on the man's back, and in them was a strange blending of contempt and fear.

The man rose and turned towards her, and instantly the look vanished, to be replaced by one of bored indifference.

"Welcome, my love," he said, with a bow, "to your future home."

Was it my imagination, or was there a sneer in his voice?

"You honor me, Sir James," she answered, with a deep curtsey. "From a material point of view it leaves nothing to be desired."

"Your Ladyship will perhaps deign to explain?"

"Is it necessary?" she said, coldly. "The subject is tedious to a degree."

"Nevertheless," he remarked—and now there was no attempt to conceal the sneer, "I must insist on an explanation of your Ladyship's remark."

"Ladyship!" Her face was white, and her eyes, for a moment, blazed hatred. "Would to God I had no right to the title."

He shot his lace ruffles languidly.

"Somewhat higher in the social scale, my love," he murmured, "than Mistress Palmer of Mincing Lane. The latter is worthy, no doubt—but a trifle bourgeois."

"Perhaps so." Her voice was shaking. "At any rate, it was honest and clean."

He yawned.

"They tell me your father is a pillar of respectability. In fact, I gather there is a talk of his being made an alderman, whatever that obscure office signifies."

"You coward!" she cried, tensely. "How dare you sneer at a man whose shoes you are not worthy to shine."

He raised his eyebrows and began to laugh silently.

"Charming, charming," he remarked. "I find you vastly diverting, my love, when you are in ill-humor. I bear no malice to the admirable Palmer, whose goods I am told are of passing fair quality. But now that you have become my wife I must beg you to remember that conditions have changed."

He reverently lifted a bottle, encrusted and cobwebby.

"From the sun-kissed plains of France," he continued. "The only other man in England who has this vintage is His Grace of Wessex. Permit me."

SHE shook her head, and stood facing him, her hands

clenched.

"What made you marry me, Sir James?" she said, in a low voice.

"My dear!" he murmured with simulated surprise. "You have but to look in yonder mirror for your answer."

"You lie," she cried. "I have but to look to your bank for my answer."

For a moment his eyes narrowed. The shaft had gone home. Then, with an elaborate gesture that was in itself an insult, he lifted his glass to his lips.

"What perspicacity!" he murmured. "What deep insight into human nature! But surely, my dear Laura, you must have realized that a man in my position would hardly have married so far beneath him without some compensating advantage."

She turned white to the lips.

"So at last you have admitted it," she said in a voice hardly above a whisper. "Dear God! How I hate you."

"The point is immaterial," he cried harshly. "You are now Lady Mertonbridge; you will be good enough to comport yourself as such."

But she seemed hardly to have heard him; with her eyes fixed on the fire she went on almost as if talking to herself. And her voice was that of a dead woman.

"Lady Mertonbridge! What a hideous mockery! Two days after that travesty of a service I found you kissing a common tavern wench. A week later you were away for two nights, and I overheard your man and my tirewoman laughing over it. Whose arms did you spend those nights in, Sir James? Which of your many mistresses? Or was it perchance Lady Rosa?"

He started violently and then controlled himself.

"And what?" he asked softly, "may you know of Lady Rosa?"

"There are things that reach even Mincing Lane, Sir James," she answered. "Even there your infatuation has been heard of and the barrier that stood between you—no money. I do not know her; I hope I never shall. But at any rate she has been saved a life that is worse than death."

"Your ladyship is pleased to be melodramatic," he said angrily. "Shall I ring for your woman to prepare you for bed?"

"A moment, my lord," she answered quietly. "This matter had best be settled now."

HE paused, his hand already on the bell-rope.

"You do not imagine," she continued, "that after what you have admitted tonight, I should demean myself by continuing under your roof. Maybe you think that to be Lady Mertonbridge of Mertonbridge Hall is enough for an alderman's daughter. You are wrong. I admit my father was dazzled at the thought of such a match; I admit that I was deceived by your soft words and your flattery. But now, after just three weeks, the scales have dropped from my eyes; I know the truth. You married me for my money, and now you have tossed me aside like a worn-out glove. So be it; you shall have your money. That is nothing. But you will have it on my terms."

His face was mask-like, though his eyes were smouldering dangerously.

"And they are?"

"Tomorrow I return to my father. It is for you to make what excuse you like. Say," she added scornfully, "that an alderman's daughter felt herself unfitted for such an exalted position as that of your wife. If you choose to divorce me—which would doubtless be possible with your influence—the money will stop. You may remember that that clause was inserted in the marriage settlement; a pity for you, was it not, that my father feels so strongly about divorce. So I shall remain there, still your wife, and you will receive your money."

He still stood with his back to her, trying evidently to see how his new development affected him. And then she continued:

"It will, at any rate, have the merit of saving Lady Rosa, or some other poor woman, from the hell that I have suffered. Even Sir James Mertonbridge cannot commit bigamy."

AND at that he understood, and his expression became that of

a devil incarnate. If he divorced her, he lost the money; if he

did not, she remained his wife. But when he turned round, his

face was mask-like as ever.

"We will go further into this in the morning, Laura," he said quietly. "You are tired now, and I insist on your drinking a glass of wine.

Her strength seemed to have suddenly given out; she sat by the table, her head sunk on her outstretched arms. And even as I looked at her, with my heart full of pity, a dreadful change came over the face of the man who stood by her side. He had just seen the way out, and I stared at him fascinated, whilst my tongue stuck to the roof of my mouth.

Quietly he crossed to a cabinet that stood against the wall, and from it he took a small exquisite cut-glass bottle. Then he looked at his wife; she was still sitting motionless. With the bottle in his hand he returned to the table; then, standing with his back to her, he poured half its contents into a glass which he filled with wine.

"Drink, my love," he said softly, and I strove to warn her. But no sound came; I could only sit and watch helplessly.

She stretched out her hand for the glass with a gesture of utter weariness; she drank. And on the man's face there dawned a look of triumph. Once again I tried to shout, to dash from my chair and seize the glass. But it was too late. For perhaps five seconds she stared at him; then she sprang to her feet, her features already writhing in agony.

Through the great vaulted hall there rang out one piercing scream: "You murderer"—ere she sank down clutching at the table. And with that power of movement returned to me, and I rushed at the man, to find myself lying on the floor bathed in sweat.

I STARED round foolishly; the electric lights were still

shining above me. My clothes lay by the glowing logs; the

refectory table was bare. The whole thing had been a dream.

Gradually I pulled myself together, though my hands still shook with the vividness of it. And then feverishly I began to get back into my clothes. They were not quite dry, but nothing would have induced me to spend another minute in that hall. The rain had ceased; the faint light of dawn was filtering through the windows by the front door. And ten minutes later, having left everything exactly as I had found it, I was walking down the drive. Anything to get away from that haunted spot.

For hours I wandered aimlessly, my mind still obsessed with the nightmare, until at half-past seven I found myself opposite a garage where a sleepy-eyed lad was beginning to stir himself. He called the owner, who promised to go out himself and tow in my car. And then I went to the inn across the road and ordered breakfast.

IT still seemed impossible to me that I had not

actually witnessed that crime of years ago. In fact, the

more I thought about it, the more did I believe that I had done

so. I am not psychic; but perhaps my brain had been so attuned on

that occasion that it had been receptive.

The landlord entered as I finished my meal, and proved communicative.

"Mertonbridge Hall, sir? It's about a mile away."

So I had been walking round in circles since I left.

"Funny you should ask," he continued. "Mr. Parker—the butler—has only just left. He spent the night here owing to the rain. The present baronet, sir? He's abroad at the moment. I gather things are a bit tight; same as with all of us. And Sir Bryan has always known how to spend his money. But if you're interested, sir, and you have nothing better to do you should go up to the Hall this afternoon. It's open to visitors between three and five every Tuesday, and Mr. Parker takes parties round."

And so at three o'clock I found myself once more walking up the drive. A motorcar passed me, full of Americans, another one stood at the front door. And, majestic in his morning coat, Mr. Parker received his visitors.

Fascinated, I stared round the hall. There was the chair I had sat in, there was the cabinet from which Sir James had taken the poison. And then, as my eyes glanced along the line of paintings, I saw the man himself. He was the third from the end, and he was wearing the clothes I had seen him in in my dream.

Mr. Parker droned on. I heard not one word till the name of Sir James caught my ear.

"Sir James was the third baronet, ladies and gentlemen; there you see his portrait. And it was to him that occurred a terrible tragedy in this very 'all."

HE paused impressively, marshalling us with his eye.

"Coming 'ome with his bride, he dismissed his servants, and sat down to supper at that hidentical table you see there in the middle of the room. Now, Sir Humphrey—Sir James' father—whose portrait is hanging next to him, was a great traveler. And he had collected, in the course of his wanderings, some rare antiques, which I am about to show you."

I was standing by the cabinet before he reached it, and he looked at me suspiciously.

"You see that bottle, now containing nothing more 'armful than water. But in those days it was filled with a deadly poison, manufactured by the Borgias themselves. Now what 'appened is not exactly clear, but it seems that after Sir James had pointed out the beauties of the collection to his young bride, he left her for a while to go upstairs. Suddenly a scream rang out, and dashing down, he found her dead on the floor. Distracted and 'eartbroken, he gazed wildly round, and found the bottle on the table, 'alf empty. What had 'appened can only be guessed at. Not wishing to frighten her, he had not told her that the bottle was filled with poison. And she, taking it out—it was specially made to taste good by them Borgias—must have thought it was some rare old liqueur. Anyway, she drank some; and there on the night of her 'ome-coming, she died."

So that was the story Sir James had told—and got away with!

"Months after, when his grief had lessened," he continued, "Sir James married the Lady Rosa Ferrington, and their eldest son—Sir Thomas—you see 'anging next his father—"

"I suppose," said a voice, "that it was an accident. No question about its being murder, was there?"

They all stared at me, and I realized the voice was mine.

"The Baronets of Mertonbridge 'All do not murder their wives," said Mr. Parker, icily.

"This hain't the movies, young man," remarked a stout woman, with a permanent sniff, indignantly following Mr. Parker's flock, and I could have laughed aloud.