RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

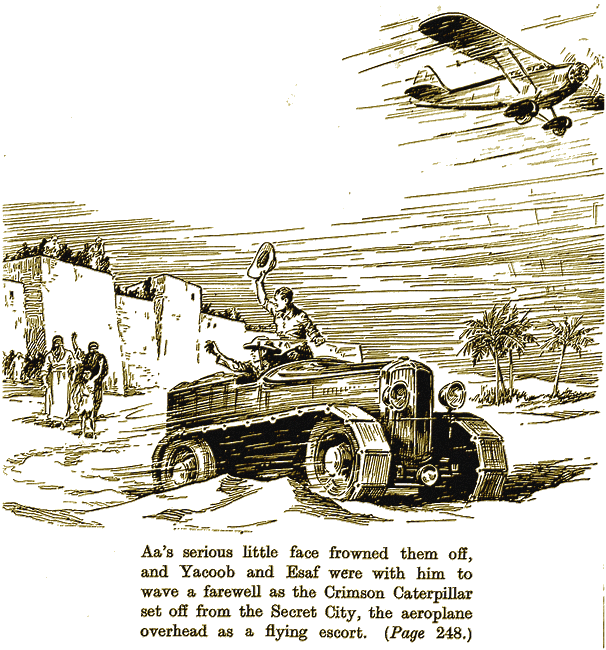

Dust Jacket of "The Crimson Caterpillar,"

Sampson Low & Marston, London, 1935 (restored)

Cover of "The Crimson Caterpillar,"

Sampson Low & Marston, London, 1935

Title Page of "The Crimson Caterpillar,"

Sampson Low & Marston, London, 1935

GASTON JAMBONNE rotated his thumbs as he nursed his hands on an ample paunch. He laughed loudly as two youths were shown into his office by a coal-black Kabyle of gigantic stature. Jambonne laughed loudly; but he did not smile.

"Hahaha! Now that we three are quite alone, shut off from all the world, we can talk. It is a great delight to see you—two so gallant youths of the two great races of Europe. Hahaha!"

The Algerian half-caste spoke in French, and laughed like no one else that Tony Mase had heard hitherto.

The English boy, as familiar with French as with English, fixed his dark eyes on the speaker; the laugh might be meant as a welcome, but Tony missed the smile that should accompany every laugh.

Gaston Jambonne shot a glance from out crafty eyes at the English boy, then extended a pudgy hand towards the French youth.

"Shake hands, my brave Henri. You come to sign the contract, yes? It is a great exploit you undertake—a journey that may astonish the world. Hahaha!"

Henri Leprince's eyes gleamed with satisfaction. Cousin of Tony Mase, he was a generous-hearted Frenchman, with all the gaiety and gallantry of his nation. The French youth told himself he had every reason to be satisfied. He had established his strange occupation at length; Jambonne had entrusted to him an undertaking that would establish his fortunes.

"Verily, Monsieur Gaston Jambonne, we will prove ourselves your trusty couriers across the Great Desert," cried the French youth. "And we will prove to you the wondrous worth of ma chère Crimson Caterpillar."

The Crimson Caterpillar of which its owner was so proud was a wonderful little motor car specially built for desert traffic. Only the previous year the Sahara had been crossed by motor cars for the first time—motor cars fitted with chenilles, an attachment to the wheels similar to that used for the Tanks in the Great War. Henri Leprince's car had a caterpillar wheel which would take it anywhere over Saharan sands, would carry merchandise and transact business at a speed that the swiftest camel could not hope to attain. Henri was prepared to undertake any employment that was honest; and this last commission, given by Gaston Jambonne, to cross two thousand miles of desert to Timbuctoo, promised to be the climax of his fortunes.

Henri had decreed that Tony Mase should be his companion on this adventurous voyage to the heart of the Sahara. Henri's and Tony's mothers were sisters.

Tony Mase's father had been an officer in the British Army, and in the Retreat from Mons, during the Great War, had been hidden from pursuing Uhlans by a brave Frenchwoman whom he afterwards married. When peace was signed they had settled in England, where their son Anthony was born. Tony in due course was sent to an English Public School; but war wounds early robbed him of his father, and his mother had a hard struggle to give her boy a fitting education. So early in his teens Tony Mase and his mother had joined their French relatives at Algiers, as there were no near relatives of his father left in England.

"Hahaha! it is a great secret, this voyage across the Sahara," declared Gaston Jambonne, watching the cousins narrowly. "We will startle the commercial world in Algiers. We will see our goods delivered in Timbuctoo in record time. It takes six months by ordinary pack camel to complete the journey to the Heart of the Sahara, but your wonderful little car, mon brave, will do the trick in eighteen days. Hahaha!"

"Eighteen days from Touggourt!" put in Tony Mase, naming the town that was on the edge of the desert, where the Crimson Caterpillar would start her journey after being unloaded from the train. "Eighteen days from Touggourt, Monsieur Jambonne?"

"Hahaha! Yes-yes," agreed the Algerian with his customary gurgles, shooting a glance at the English boy whose persistent gaze he seemed to resent. "Certainly I mean eighteen days from Touggourt. Have I not been liberal with you, Henri my brave one, and have I not promised similar liberality on your return from Timbuctoo?"

Henri Leprince nodded gratefully at his employer's appeal, the French youth turned to his cousin. "To-day the generous Monsieur Gaston has paid into my bank account the equivalent of one hundred pounds of your English money, Tony, and he has promised another hundred pounds to be paid over immediately on our return."

"But what if we are killed?" Tony addressed his query to the trader.

Jambonne laughed loudly as if it were a huge joke.

"Hahaha! Are you the sort of fellows that get killed? No, no, my so brave heroes; you will conquer all difficulties; for I have my agents to assist you in every oasis of the Sahara, and they, knowing the power of the House Jambonne, will bend every effort to further your journey, and to guard you from all dangers of the Desert—from thirst and starvation, from wild animals and fierce winds, from marauding bands of Tuaregs, from all robbers and—"

"But even your swiftest mehari could not keep pace with our car, Monsieur Jambonne," Tony interpolated. "Your camel rider would be left far behind three minutes after the Crimson Caterpillar had got going."

"Hahaha! It will surprise you, English boy, the efficiency of the House Jambonne. And unless your so wonderful Crimson Caterpillar should blow up and go skywards in little bits—"

"Trust ma chère Crimson Caterpillar to win through, monsieur," interrupted Henri icily. Any aspersions on his beloved bus were regarded as a personal insult to himself.

Jambonne was all love and compliments forthwith. "I but suggested the wildly impossible, mon ami, even as our little English hero did when he hinted that the House Jambonne could not protect its agents against the happenings of the desert. Hahaha!"

"We will be back in Algiers by March the Sixth as I have promised, Monsieur Jambonne," asserted Henri Leprince, tapping his chest with a confident Gallic gesture.

"I do not doubt it, my trebly brave hero," the Algerian half-caste responded. "Hahaha! what an epic journey lies ahead of you! And how my friend and agent in Timbuctoo, Sidi ben Baar, will marvel at the swift delivery of the salt bars. Ha! what was that? Is there a listener—an eavesdropper?"

The factor sprung from his chair, pulled open a drawer, snatched forth a revolver and pointed it in the direction of the slight rustling that Tony could only just detect.

The room was half office, half reception room, high up in Jambonne's private house in the Arab quarter. There was only one window looking out over the port of Algiers, and that was a grille of iron bars rather than a window of glass. The iron-studded door had clanged-to behind the youths as the giant Kabyle porter had retired. There was one big table, at which the Algerian sat, and a divan on which he might recline. Rows of ledgers stood on shelves to right and left, and a series of pigeon-holes filled with papers occupied the wall behind him. Two wicker chairs, on which the cousins sat, completed the furniture of the office. It looked impossible for anyone to hide there.

But Jambonne had knelt and pulled upward the draping of the divan.

"There certainly came to my ears the movements of a spy," said Jambonne, as he let the hangings of the divan drop over the vacant space revealed. "Ha! I have it. There is someone boring a hole in the wall through which they may hear our secrets. Ha!"

There was a sound of something scratching or disturbing papers in one of the pigeon-holes behind Jambonne's seat.

"I have you, foul eavesdropper," cried the Algerian as he flung himself against the nest of small compartments, and from one of them tore paper after paper frantically with one hand, whilst with the other he menaced the tiny hole.

Tony was curling his lips at the half-caste's frenzied fear; Henri was puzzled at his employer's sudden onslaught on the pigeon-hole.

"Do not move," Jambonne cried. "I have you covered. I see your eye—it glistens. My bullet will pierce your brain, you double-dyed villain."

A mouse sprung to the floor, and Jambonne collapsed on to his chair.

"Hahaha! How did you like my acting?" asked Jambonne, slipping his revolver swiftly back into the drawer. "Hahaha!"

But Tony Mase knew it had not been acting and wondered at the fear the factor showed over such a small matter as a trading journey.

"Hahaha! Henri my brave boy," continued the Algerian, wiping sweat from his brow with a red silk handkerchief. "It is thus I impress my agents with the urgency of the work they undertake for me. You dear boys, so generous, do not guess how my competitors seek to wrest my trade secrets from me. And it may be that they will place another car to compete with me on this journey across the Sahara."

"There is no second Crimson Caterpillar in North Africa," declared Henri proudly.

"That is why I engaged you, Monsieur Henri Leprince. Hahaha! Yet be as secretive as moles, as silent as serpents, as impenetrable as marble, for, believe me, the future of a colonial empire—of commerce, may rest on your young shoulders!"

"Vive la France!" cried Henri, solemnly saluting.

But Tony bent to do up his boot-lace. He didn't relish heroics and wasn't at all sure that he trusted Monsieur Gaston Jambonne.

The factor, following the mouse incident, recovered his composure with a perfect tornado of laughter, then produced a document for Henri to sign.

It was merely a legal agreement between Gaston Jambonne and Henri Leprince, drawn up in the roundabout long-winded way beloved by lawyers of all races, stating that a consignment of salt bars should be duly delivered by the said Henri Leprince for the aforesaid Gaston Jambonne to Sidi ben Baar in Timbuctoo, and if the aforesaid Sidi ben Baar desired to be delivered to the aforesaid Gaston Jambonne certain goods to be carried by the aforesaid Henri Leprince on the return journey, the said goods must be delivered on or before March the Sixth following. In return for which service, shorn of all its legal verbiage, the document stated that Henri should receive the equivalent of one hundred pounds before he started and a second hundred on his return.

The French youth signed without further ado, though Tony whispered that there ought to be some further consideration of the document first.

Jambonne noted the English boy's caution. "Hahaha! A mere formality amongst friends, Leprince my brave one. I know you well enough, Henri, to realise that you would accept my word. You have known me longer than this English boy who is but new to our colony. I do not hesitate to trust my most private affairs to so valiant a hero as Henri Leprince."

The French youth bowed low. "My utmost service is at your disposal, monsieur. We start to-morrow as you have desired, Monsieur Gaston Jambonne."

But unromantic Tony merely raised the query: "Who pays for the petrol, Monsieur Jambonne?"

"Hahaha! The English infant has the trading instincts of his race. Is it not plainly stated in the contract that all expenses of the journey are paid by the House Jambonne? The House Jambonne has resources that the President of the Republic may well envy."

The hero-worshipping Henri murmured: "You are wonderful, monsieur," seeing in Jambonne a king of commerce, a pioneer who would open the undiscovered hinterland of the Black Soudan, and a patron who would place Henri Leprince on the very pinnacle of industrial fame.

"Hahaha! It is indeed a gay and wondrous journey that lies ahead for you two heroes," concluded the Algerian factor, pressing the push of an electric bell. "To-morrow at ten o'clock, I will meet you at the railway station to see your Crimson Caterpillar duly entrained for the midday departure. Hahaha! Hahaha!"

There was a prodigious tap on the iron-studded door, five times repeated.

Jambonne arose and crossed the floor. "The door to my sanctum once shut cannot be opened except from the inside, and the knock you now hear is a signal which is changed each day. So no intruder can disturb my serenity."

"Except a mouse!" Tony Mase could not keep himself from blurting out.

Jambonne shot a glance that was not kind at the English boy, then laughed uproariously. "Hahaha! these English they are droll, my Henri. But we, my brave one, must take responsibility upon our shoulders, and think only of the goal."

The Algerian half-caste pulled back a bolt, turned a handle, and the massive door swung hack to reveal the same giant Kabyle who had conducted the youths into his master's presence.

There was a swift interchange of words in a dialect that neither of the cousins could understand, then, with a tornado of "Hahahas!" behind them, they were led once more down the stairs by the black Kabyle.

"A great adventure!" exclaimed Henri as the cousins passed out into the narrow street where scarcely a ray of sunshine could penetrate.

"A great venture!" said Tony Mase.

For whilst the French youth was brimming over with confidence, the English boy, remembering the unsmiling eyes of Gaston Jambonne, was not so sure that everything was as straightforward as the Algerian factor would have the cousins believe.

"ALREADY we are shadowed, Henri," remarked Tony Mase, kneeling to fumble with his boot-lace and to cast a sidelong glance at a tall figure in an Arab burnous who was following in their wake.

"The wonderful Jambonne has deputed a servant to see that we reach our house in safety, Tony, suspicious one," responded the jubilant Henri who was busy building commercial castles-in-the-air of which Gaston Jambonne was the architect.

The cousins had parted from the Algerian factor only a few minutes before. It was the watchful Tony who had spied the tall figure in the shadowed doorway opposite Jambonne's residence. An Arab he seemed; but Tony could not see his face, the burnous cloaked the stranger from head to foot. But he was following them—Tony was certain.

Night was falling swiftly, and the crowd grew in numbers as the steep streets of the upper town were left behind, and the boulevards of the town of Algiers were neared.

"Take this short cut, Tony," advised Henri. "You will see that your fancied spy will not follow us."

The cousins dived into a narrow alley, so narrow that when pack mules passed, the youths were forced to press back against whitewashed walls or iron-studded doors with over-hung casements above.

Came sudden cries of alarm, shouts of warning, and screams of pain.

A bolting, bucking, biting mule sent the Algerian crowd fleeing for safety up the narrow alley. And the mule followed.

Tony and Henri were borne backward by the press of scared natives. A Moor with a broken leg was dragged backwards by two black servants. An unfortunate little bootblack was lifted high in air by the mule's rear hoofs, and the little fellow fell on the cobbles a motionless bundle of rags.

Tony would have pressed to the rescue, but he was jammed by the crowd about him.

"Tackle the beast, somebody," he shouted.

His shout was answered by no other than the hooded man who had shadowed the cousins. "Well spoken, boy. Better a dead mule than a crippled shoeblack."

The mysterious man's massive shoulders had forced a way through the crowd till he faced the bucking mule with a knobbed stick.

Raising his weapon aloft with two hands, the hooded stranger with incredible celerity brought it down with a thud between the mule's ears.

The biting mule stood swaying on its four feet, all the fight taken out of it. Wider and wider straddled the four legs.

Tony laughed aloud at the grotesque appearance of the animal. "That blow has made the mule a perfect ass," he said.

But Henri was too enthused at the shrewd blow of the stranger to heed his cousin's joke. "Bravo, gallant rescuer," he said, clapping the hooded stranger on the back. "You have saved all our lives."

But the man of the knobbed stick had bent to lift the little bootblack.

A skinny old Jew ran up, demanding compensation for his injured mule. Whereupon the crowd turned their attention to the owner of the mule which had caused all the trouble.

A black soldier clapped a great hand about the skinny neck of the Jew, and propelled the protesting Israelite down the alley with forceful knees.

The crowd, forgetting their rescuer, followed the soldier, demanding satisfaction of the Jew who set savage mules on innocent Algerians.

"Ungrateful canaille!" remarked Henri, then turned to the hooded man who was bearing the injured bootblack in his arms. "How can we thank you for your heroism?"

"I seek no publicity," said the stranger speaking in French, as he had done throughout the incident. "But at the midnight hour, Henri Leprince, I will come to the red rose bower in your garden. Fail me not, there is more in this than your wildest imaginings."

Suddenly under overhanging casements a door opened and a light shone forth. The lantern dipped twice and was shrouded.

"Au 'voir!" whispered the hooded stranger. And, bearing the injured cireur in his arms, he disappeared into the shadows.

There came the clanging of a door, and only a stupefied mule remained to prove the prowess of the mystery man who had faded from sight.

"By the Tower Eiffel!" exclaimed Henri. "Who is that magician who knows the red rose bower hidden in the depths of our walled garden? I wonder if he really is in the employ of Monsieur Jambonne. I should like to have seen his face."

"I saw it," said Tony triumphantly. "When he lifted his stick to fell the mule, his hood fell aside. The face was the face of a white man. And certainly I should recognise it again, for our rescuer's nose was a crooked one."

"The man with the crooked nose—we meet him at midnight!" cried Henri, striking a dramatic pose.

"Wait and see!" said Tony, who was always so practical that he annoyed his imaginative cousin.

At the rose bower in the garden of the Leprinces the two cousins awaited the man with the crooked nose.

"If the man who followed us and rescued us from the hoofs of the mule is not a spy of Monsieur Jambonne," said Henri, "maybe he is a trade rival who would worm the secret of our desert journey out of us."

"At least he is no Jew trader," Tony responded. "His face was that of a Frenchman."

"Why not that of an Englishman, Tony?"

"No, Henri, he was no Englishman. His features were too—refined," retorted Tony, anxious to say the right word that wouldn't offend his French cousin, though "refined" didn't exactly express his British prejudice.

The cousins constantly argued as to which was the finest race. Henri Leprince asserted that the British were superior fellows—for politeness' sake! Tony as stoutly maintained that the French were by far the most gallant nation—though the word "gallant" had a restricted meaning to Tony if truth be told. Both asserted loudly that his cousin's countrymen were the noblest, and both were quietly convinced in their own hearts that no nation surpassed his own.

So, whilst awaiting the arrival of the mysterious stranger who had dogged their steps, the cousins launched into the ever-recurring topic. And no stranger with a crooked nose came to stay their argument.

The eastern horizon was greying with the coming of morn when the cousins gave up their vigil.

"It was foolish to heed the word of a stranger; his words may be as crooked as his nose," Henri said.

"He spoke like a true man," asserted Tony. "I trust no ill has come to him. I feel, somehow, that we shall see him again."

At 10 a.m. the cousins met Gaston Jambonne and his giant Kabyle at the Goods Department of the Algiers railway station, as had been arranged.

"Isn't she a beauty?" exclaimed Henri as he and Tony hasted into the yard where the Crimson Caterpillar rested by the truck on which she was shortly to be hoisted.

The Crimson Caterpillar was a compact little car, a Citroën of the 10 h.p. type, with two seats for chauffeur and companion. The rear of the car was fitted with a considerable rumble, leaving ample space for merchandise. But the unique feature that made Henri's car capable of crossing the desert was her chenilles or "caterpillars."

These ingenious contrivances consisted, in principle, of an endless rubber band, a sort of supple moving rail which unrolled as the car proceeded over sand; thus, as it were, laying down her own railway track and picking it up again behind her. There were modifications in her structure that might have puzzled a novice till he was reminded that it was vastly important to protect the Crimson Caterpillar from sand which might invade her bearings. In her construction the consumption of water had been reduced to a minimum by adding condensers and sheaves of lateral wings on the radiators. She was well-named the Crimson Caterpillar, for Henri had ordered her bonnet to be a bright crimson, and everywhere the enamel published part of her name whilst the chenilles published the rest.

"Hahaha!" roared Jambonne waddling up to Henri. "We have already loaded the salt bars." And he pointed to his giant porter.

The Kabyle grinned like one guarding a great secret.

"Listen to me, my hero Henri," continued the Algerian factor. "I desire you to tell my friend Sidi ben Baar when you arrive in Timbuctoo that this—" he pointed to a block of salt at the base of the pile packed in the rumble—"is the best bar—the best bar, mark you, Henri, the Best Bar! Sidi ben Baar always retains the best bar for his own consumption, and I have marked it with a crescent so!"

The Algerian pointed out the sign scratched with a dagger on the soft surface of the bar of salt. Beyond noting their employer's instruction, the youths took little notice of that crude mark on which the whole success or failure of their desert venture was to depend!

"Sidi ben Baar shall be shown the crescent sign, Monsieur Jambonne," declared the conscientious Henri.

"Good! Now, for a space, I go," said Jambonne hurriedly, as he and the Kabyle swiftly passed behind a nearby shed.

The Customs officials were coming.

The official was friendly with Henri and was aware of the business rectitude of the young Frenchman. "This is indeed your car, Leprince?" he asked. "It is not the car of Gaston Jambonne?"

"The Crimson Caterpillar is my very own property, sir," replied Henri. He was going on to say that, though employed by Jambonne, the factor had no share in the car's ownership.

"Your cargo is—?" came the query sharply.

"—is but salt, monsieur," Henri replied.

"And you are sure you carry nought but salt? No smuggled goods, such as firearms?"

"Nothing but salt, sir," declared Henri. "See! there is every inch already occupied with salt and such provisions of food and oil as will be necessary to carry us to Timbuctoo."

The official came close to Henri. "We do not trust a certain Gaston Jambonne. But you are a true Frenchman, and your salt may be passed." Wherewith the official scratched certain chalk marks on the tarpaulin which was forthwith flung over the Crimson Caterpillar by the Customs officers.

"The preliminaries of our enterprise are successfully accomplished, Tony," declared Henri. "The Crimson Caterpillar will be hoisted to the railway truck, and the car will not be touched again till Touggourt is reached. And then it will mean little more than lowering ma chère Caterpillar to the desert sand. In fact the consignment of salt will not be touched till it is unladened by Sidi ben Baar in Timbuctoo."

So thought Henri Leprince, having no foreknowledge of the existence of a certain strange boy called Aa!

"Anyhow it's time we got back to lunch," said Tony, consulting his wrist-watch.

But as they summoned a taxi to take them home for the final farewell, the Customs officials having disappeared, Gaston Jambonne and his giant Kabyle reappeared.

The trader would leave nothing to chance. The Kabyle would remain in the vicinity of the Crimson Caterpillar till it went south by the Biskra express which the cousins were joining at midday.

"I can't understand all this fuss about a few bars of salt," said Tony to Henri as they were borne home to lunch.

Henri smiled in a superior manner. "Salt, my ignorant English cousin, is as valuable as silver in the distant deserts. Without constant supplies of salt Timbuctoo, an ancient city as old as Time, now the capital of our Saharan empire, could have existed but a few years. Twice a year the Azalayi for centuries past has set out from Timbuctoo, under military escort, to fetch some two or three thousand bars of the precious commodity from the salt mines of Taoudenit. All Timbuctoo turns out in festive fashion to greet the returning Salt Caravan with thrum of tom-tom, blare of trumpet and the huzzas of twenty differing tongues—so important to the life of the desert metropolis is the Azalayi. . . . Jambonne says that our little consignment arriving just before the ordinary supplies come in, will mean much money for Sidi ben Baar and much profit to himself."

"And what merchandise are you to bring back, Henri?" the cautious English boy asked.

"My benefactor did not say, for he did not know. Sidi ben Baar might desire us to bring back costly carpets, rare feathers, ivory or gold dust."

The taxi-cab was passing through the Mustapha suburb of Algiers at the moment. Tony sprang to his feet.

"Look!" he cried. "I saw the man's face."

A car was drawn up before a private residence perched high above a flight of steps. A man in Arab burnous had been lifted out, and was being borne on a stretcher through the iron gates at the foot of the stone stairs.

"Who is it?" cried Henri as he signalled the taxi driver to stop.

"The Frenchman with the crooked nose," cried Tony. "Now we know why he didn't keep his appointment at the rose bower."

"Foul play!" exclaimed Henri springing from the cab.

But the car that had brought the wounded man to the gates whisked off in a cloud of dust. And the stretcher passed through gates that clanged-to behind it.

A villainous porter glared at the clamouring cousins.

"Whose house is this, garçon?" Henri demanded through the bars of the gates.

"What business is that of yours?" was the retort. "May not a doctor keep a private hospital without a passer-by wanting to inspect his patients! Indeed, youths have been known to come into danger from this evil habit of curiosity."

The man's manner was menacing.

"But I demand to see your master," cried Henri.

"He cannot come. He is operating on a patient—cutting out his liver," responded the man with an evil grin. "Such is the only cure for curiosity."

Tony was consulting his watch. "Our train leaves in less than an hour," he urged. "And we have yet to lunch and say our farewells."

"But yes," responded Henri, jumping again into the taxi-cab, "we must not desert our Crimson Caterpillar. Though we leave an unsolved mystery behind us, Tony."

"SOON we reach. Touggourt, mon brave," Henri remarked as the train bearing the cousins and the Crimson Caterpillar neared the end of the journey to railhead. "Before us the illimitable Sahara!"

Tony grinned at the outstretched palms of his cousin. "My dear Henri, the desert ahead is but a mere three and a half million square miles, so you mustn't say it hasn't limits."

"Oh! you prosaic English, you have no poetry," retorted the Frenchman. "But certainly it is a desert big enough to conceal its boundaries, big enough for a regiment to lie down and die in."

"But the Crimson Caterpillar is not the sort of creature to lie down and die in the desert, is she?" chaffed Tony.

"Trust ma chère Caterpillar to win through," said Henri solemnly, his good-humour restored.

"I wish we could have followed up the mystery of the man with the crooked nose," Tony continued, remembering the incident outside the villa in Algiers. "Was he friend or rival? Why should he visit you secretly? And how did he receive his injuries? And whose was the house he was carried into?"

"The Villa Agadaas was the name painted on the gates, thou unobservant one. And I have left the affair in the hands of my father, who has promised to send a wire to the post bureau in Touggourt. He will put the matter in the hands of the police, if enquiries are not satisfactory."

"Anyhow, he will have had time to investigate," said Tony wearily; "it seems years since we left Algiers."

Though much interesting time had been spent studying maps and the prospective route across the desert to the exclusion of all other topics, the cousins' thoughts came back to the alarming affair of the man with the crooked nose, and they were anxious to learn what news awaited them from Monsieur Leprince, senior. According to schedule, they were to spend an afternoon and a night at Touggourt before bidding adieu to civilisation.

As the train steamed into the station where they were to alight, they looked forth on fair prospects of verdure bordered by sand.

"An emerald set in gold," cried Henri fantastically.

"A diving board whence we plunge to a sticky death," corrected Tony, who was wont to damp down his cousin's Gallic exuberance.

"Pah! you illogical fellow, did you not say but an hour ago that ma chère Caterpillar was not the creature to lie down and die in the desert? Certainly we shall win through."

Their first care on disembarking was to see their car safely shunted to a siding. Following which an adjournment to the Hotel Djouf was to be made. Gaston Jambonne had arranged for the youths' reception there. Such was the scheme outlined by Henri as the cousins descended from the train.

Their feet had scarcely touched ground before they were the centre of a clamouring, hustling crowd of touts and interpreters of all shades of colour, jabbering in the tongues of Babel.

"I Tommy-Tom, quite English," announced a coal black Makhazni from the interior, concentrating his attention on Tony. "I spik same you, oh yes."

Meantime an ancient Moor was informing Henri that he—the Moor—was three-quarters French and could speak the language of Paris.

"This is more than a joke," cried Tony, Jerking his knee into a too-adjacent body, the fingers whereof were seeking to find his purse.

The pickpocket doubled up and backed. Only to be replaced by other rogues in that sea of coloured humanity.

"Gendarme!" cried Henri from out his encircling pests.

But no policeman put in an appearance.

Tony yelled to two Zouaves to come to the rescue, when all at once, there was a miraculous change in the situation.

An Arab leaning on a crutch limped forward, said a few words on the outskirts of the scrimmage, and the crowd melted like snow before a solution of salt. So that the cousins found themselves facing one lone cripple.

"Gaston Jambonne bade me take you to the Hotel Djouf," said the miracle worker in the lingua franca of the Sahara. "I am your obedient servant."

"What are your fees?" demanded practical Tony.

"I am already paid," said the crippled Arab proudly. "I am of the House Jambonne."

The Arab stumped ahead of the cousins, and although touts of every degree of rascality bore down on the visitors, at a sign from the cripple they instantly withdrew.

"Your car is guarded," said Jambonne's agent when Henri would have turned to inspect the Crimson Caterpillar. "You can see her when you have dined."

It was a strange city there on the outskirts of civilisation. From Moorish cafés came the shrill squeaks of reed pipes, the tireless tattoo of tom-toms, the ceaseless jingle of tambourines. On curious stalls traders exhibited the trophies of the desert for sale, whilst quite modern emporiums showed European products behind plate glass.

Passing the cousins on the side walk were weird figures from out the desert world, natives to whom as yet Tony could attach no name. There were stately sheiks wearing robes fashionable in Father Abraham's time, there were colonial lieutenants flaunting gay uniforms that would be the vogue on the Bois de Boulogne a year hence. Everywhere there were bright patches of colour, the garish dress of Spahi, Turco and Zouave.

Tired from their journey the travellers were glad to see the sign "Hotel Djouf."

"What a glorious array!" cried Henri as they passed a great clump of blooms amidst a beautiful background of flowering shrubs and feathery ferns within the hotel grounds.

"But there's a queer ornament in the garden," Tony exclaimed, pointing to a cowled figure squatting like a statue amidst the flowers.

"Probably a marabout or saint of sorts," remarked Henri carelessly.

Tony, however, noted that the cowled head turned slowly as they passed, and the English boy felt sure that piercing eyes were following their every movement with more than necessary interest.

The cripple led the cousins to a stalwart Soudanese hall porter. "A servant of the House Jambonne," he whispered.

The Soudanese porter became their devoted slave. The cripple seated himself at the door of the hotel.

After a meal amidst diners not one of whom was white, the cousins set out, under the guidance of the crippled Arab, for the post bureau to see if messages awaited them there.

There was a telegram from Henri's father.

Henri's brow knit as he read. "The Villa Agadaas was deserted when my father visited it," he told Tony, "and the house agents whom he saw later assert that the Villa has had no tenant for six months. The visitors left no clue, and the police pooh-pooh my father's information."

There was another telegram—from Gaston Jambonne. "Depart at dawn—secretly."

The cripple assured Henri that the Crimson Caterpillar was guarded by the agents of the House Jambonne, but Henri could not rest till he had inspected the car which had been unladen from the railway truck and was ready for an early start. A motor mechanic was polishing the crimson bonnet when the French youth arrived.

"Ma chère Caterpillar, at any rate, is ready to comply with our employer's orders," Henri declared, "but I wonder why Jambonne sends this telegram. What new development has made necessary this sudden departure that he commands?"

"There's more in this than meets the eye, as the pugilist said of the blow that knocked him out," remarked Tony. The English boy, though he jested, left nothing to chance; he was curious about the cowled figure that sat In the hotel garden.

"He is a holy marabout from the desert," the Soudanese porter told Tony. "There he has sat for ten days, living on such fare as the hotel flings to the dogs. He does not even solicit alms nor chant passages from the Koran."

As he looked from his bedroom before retiring, Tony saw the marabout still sitting there.

He was determined to probe the mystery, not leave enquiries till too late, as in the affair of the Villa Agadaas.

He slipped out into the garden without Henri's knowledge. He passed close to the cowled figure.

There came a softly spoken question in a tongue Tony did not understand.

"Do you want word with me, holy man?" Tony asked in French.

In broken French came the response. "What do you carry to the city of Timbuctoo?"

"My cousin and I are taking bars of salt, holy man."

"Take you the salt to Sidi ben Baar?" came the query that made Tony grow cautious.

"Why ask that, holy man?"

"Is there nought but salt in thy car?" the marabout asked, and as he leaned anxiously forward, the cowl parted to reveal—a weird white face and curious yellow eyes that gleamed like a cat's.

"I swear we carry nothing but salt, holy man," Tony found himself saying in answer to compelling yellow eyes. "Good night."

"Au revoir!" said the marabout as he drew his cowl about his strange whitish-grey face with the catlike eyes.

Tony quickly found his cousin and told him of the strange interview amongst the flowers of the garden.

"I will speak with the mystery man myself," Henri said.

But when they came to the place where the marabout had sat, the man had completely disappeared, and only the wail of some reed instrument came weirdly to their ears from the verge of the desert.

IT was early morning when the cousins, following Jambonne's telegraphed instructions, set out from the Hotel Djouf. The proprietor had refused all payment: was he not the servant of the House Jambonne?

The crippled Arab was awaiting them, and bore them company.

"That marabout who sat amongst the flowers—who was he?" Tony asked the Arab.

But the cripple evidently knew nothing certain of the mysterious man who had disappeared; it would seem that the marabout, at least, was not of the House Jambonne. "He was a Tuareg—one of the Veiled Ones," was the only information that their Arab companion could give.

"The Veiled Ones—who are they?" Tony asked Henri.

"The Veiled People, as the Tuaregs are known throughout the Sahara, are the aristocracy of the Desert," Henri explained. "They are of a southern race of Berbers, and, what is a curious fact for an African race, they are white men—almost."

"Our marabout of the flower bed was whiter than a white man," Tony declared, "his face was as white as a bladder of lard. Perhaps he was a leper."

Henri gave a gesture of dissent. "The Tuareg is white and proud of his colour; he is a warrior, and his Berber ancestors twice invaded Europe in the early days of history. He dwells away in the wild mountain fastnesses of the Sahara, whence he is wont to come forth to raid and kill. For the Tuaregs are fighters by heredity and training, though our French Colonial administration is bringing them into something like submission. No, Tony, your Tuareg marabout is not a leper."

"I wish you could have seen his face, though I didn't see much, certainly. He wore a sort of veil almost to his eyes—I suppose that is why the Tuaregs get the name of Veiled Ones?"

"Yes," agreed Henri. "But now let's think of our Crimson Caterpillar and the epic journey before her."

"Humph!" growled Tony, "it seems to me that the Crimson Caterpillar leaves a mystery behind her wherever she goes—the wounded man with the crooked nose in Algiers, the sickly white marabout in Touggourt. I wonder what mystery awaits in Ouargla?"

"Always there is mystery in the desert, Tony, but we travel faster than mystery can follow," laughed the French youth.

"Don't know about that!" retorted the English boy. "Anyhow we can't travel faster than wireless."

Yet, curiously enough, an hour after the Crimson Caterpillar had faded into the blue immensity of the sand plains, came a wireless telegram to Touggourt for Henri Leprince. "Await me at Touggourt," said the message. "Of incredible importance. He of the Rose Arbour."

But by that time the Crimson Caterpillar had left the last Kouba, or Moslem tomb, of the Touggourt district far behind, and was proving the unique value of her "caterpillars" on the sebkra, the dried-up sea of aeons ago. Instead of getting sand-bogged every few minutes, as rubber tyres would have done, the Crimson Caterpillar's wheels raced steadily onward.

She did not need her back wheels cleared from sand, did not require spades and jacks and levers to raise her from pits of her own making, nor camels and mules and a crowd of hauling natives to drag her to firm ground, nor sacks nor boards nor fine wire netting for her front wheels to pass over.

"No no," boasted a proud owner. "Ma chère Caterpillar is no ordinary car, my Tony, she sees the sand, heaps it up in front of her, then planes it down and rolls along leaving her path behind her."

Only once in the first day was there any difficulty with the unique car. In the sand dunes of Temassine, where giant drifts of drinn grew, a pulley got stuck and fouled the caterpillar. Tony and Henri, however, soon put that to rights, and by evening the Crimson Caterpillar came in sight of the place where Henri planned to spend the night—Ouargla.

The slender minarets of the mosque showed above the battlements of the fort where France kept watch over her desert territory.

Soon the motorists were aware that their car had been seen, for a posse of horsemen under a French lieutenant issued from the fort and galloped towards the travellers.

The gallant Lieutenant addressed himself to Henri. "We give you welcome, Leprince, to the Golden Key of the Desert. We beg to be allowed to entertain so enterprising a couple of voyagers. With us we bear two steeds brought for your use. You will take the place of their riders who are skilled motor mechanics. These two may be trusted to take care of your car whilst you yourselves disport yourselves in our papote."

Henri stared at Tony. Tony stared at Henri. They would have liked a private conference: Gaston Jambonne had said they were to travel secretly, but here at the onset of their enterprise they were being given a military reception; here, in Ouargla, a town Henri had never visited, the young Frenchman's name was known and their arrival anticipated.

Henri stepped from the driving wheel to the sand. Bowing to the lieutenant, he said: "It is remarkable that you are aware of our coming, monsieur."

"Always in the desert it behoves us exiles to have as many eyes as a peacock, each eye glued to a field-glass, mon ami. On the morrow, all being well, you and the English boy shall continue your pilgrimage."

"Why should not all be well, monsieur le lieutenant?" Henri demanded with some heat.

The lieutenant shrugged his shoulders in reply. The two mechanics bounded into the seats vacated by the motorists. Two privates, holding the riderless horses, bade Henri and Tony mount, with eloquent gestures.

"Monsieur le lieutenant, never shall I forgive your mechanics if they hurt one rivet of ma chère Crimson Caterpillar," Henri exclaimed.

"They are experts, Leprince," said the officer tersely. "I beg you, if you can ride, to mount your horses forthwith."

Reluctantly Henri, with a rueful glance at his car, sprang to the saddle. Tony, urged by the insinuation that he might not be able to ride, was astride his horse quicker than his cousin.

Towards the battlements the cavalcade trotted, Tony wondering what the papote where they were to be entertained might be like.

Through the palm groves, headed by the lieutenant, the posse of horsemen passed; everywhere there were date palms and abundant water, for the underground river of the Wadi Mya has made Ouargla a place of fertility and importance through the centuries.

The Crimson Caterpillar followed in their rear; but after they had passed into the fort of Ouargla, Tony noticed that the car went in another direction—"to the garage in the town," as the lieutenant explained to an anxious Henri.

The papote proved to be the sergeants' mess, where gathered the non-commissioned officers of a detachment of France's Foreign Legion. It was a strange assortment of soldiers, one sergeant had been a Russian nobleman of Moscow, another sergeant had been an Italian ice-cream seller at Margate, a third officer was a Pole who cheerfully confessed to murder in Munich, a fourth was said to be an Englishman—a silent gentle flaxen giant with blue eyes.

The non-commissioned officers dressed for dinner in white blouses which were belted loosely over baggy, white corduroy breeches. Each sous-officier, apparently, could speak not less than four languages, but the conversation during dinner was mostly in French. Tony was surprised to find how elegant were their manners and how excellent was the meal. Indeed the sous-officiers of the Legion were no less refined than the lieutenant who had ridden forth to greet the motorists.

It was after dinner when Henri grew fidgety. "I must wish ma chère Caterpillar good repose," he said to Tony, and begged the Russian sergeant to conduct them to the garage where the Crimson Caterpillar was housed.

The Russian, however, though vastly polite, made no move to accede to the French youth's request. The Italian, with many elegant gestures, declared he feared the rigours of the Saharan night. The Pole apologised but ventured to think such a visit impractical, and, on being pressed, insisted it was against orders. The corporal of the blue eyes and flaxen hair, turning to Tony, said in English: "Don't take risks, my lad. It is best for you both that you do not see your Crimson Caterpillar to-night."

Henri heard, shrugged his shoulders and made his plans. So they sat talking of the wonders of the desert wastes, of star-spangled skies, and of rose-red dawns, and of pitiless raiders and the unknown lairs where the Veiled Ones hid.

"Beneath the desert sand an older civilisation lies buried," declared the Russian as he smoked cigarette after cigarette of yellow-hued paper and pungent aroma. "Once there were fertile lands where rivers flowed and beautiful lagoons gave life to groves of date palms and luscious tropical fruit; there were cities of wondrous beauty where dwelt a race now conquered by the invading sand."

"There is much treasure deep—deep down under centuries of sand," said the Pole, sucking at his pipe.

"Dig down a mile," said the corporal of blue eyes in Tony's ear, "and you'll find—you're tired!"

"But are there really buried cities beneath the sand?" Tony asked of the English-speaking corporal.

"Haven't a doubt of it," responded the handsome young giant, "but I wouldn't finance an expedition to dig 'em out—even if I had the money. Don't trust the Sahara, my lad, she'll swallow you and ask for more. The English have done well to keep away from her. Good night." And the corporal who wouldn't confess to a nationality or a name passed out of the mess-room, and out of Tony's life.

Shortly afterwards the two cousins were shown to their quarters—a barrack-like apartment with two camp beds.

They were left alone.

Henri examined the fastenings of a prison-like window. "Ma chère Caterpillar will not sleep without my good-night kiss," he said with a wink. Following which Gallic sentiment, Henri set about climbing through the window aperture.

Tony followed stealthily, whilst outside their bedroom door a private of the Legion kept watch.

With the utmost caution they crept towards the barrack gates.

Nearing a sleepy sentry who had received no orders regarding the visitors (the guard at the bedroom door was considered sufficient by those in authority), a bold Henri, and a no less confident Tony, saluted the black sentry, and left him gaping whilst they passed out into the night.

A lean native, nigh naked, rose up out of the shadows. "Of the House Jambonne," he whispered. "Whither shall I lead you?"

"To my car," was Henri's terse reply.

The lean native instantly loped off at such a pace that the two adventurers had all they could do to follow.

By narrow lanes, in the shadow of long, low buildings whence came the hum of voices, the trio passed to another part of the fortified town.

"Thy Crimson Caterpillar is there," said the lean one, pointing to a zinc-roofed shed. "And if I do not see you again, tell Monsieur Jambonne that Yussuf of Ouargla serves him faithfully." And the man disappeared as suddenly as he had arrived.

Before the cousins was a workshop whence flared kerosene lights, and through the open doorway could be seen privates of the Legion busy about the Crimson Caterpillar.

"We'll surprise them," said Henri indignantly. "They appear to be tampering with our goods."

At the words the furious French youth burst into the shed, brushing aside a bayonet that would have barred his entry.

Tony followed, giving the truculent sentry a punch—below the belt, I fear, for the man gasped.

The cousins were astounded to see the rumble of the Crimson Caterpillar emptied of salt bars and stores, whilst superintending the removal was the lieutenant, who, instead of asking the cousins to dine with him, had put them in charge of the sergeants' mess.

"What does this mean?" Henri demanded, striding up to the lieutenant.

The officer smiled, raised his sword in salute, and bowed low, replying with a smile: "A mere matter of custom."

"This is beyond a joke, sir," Henri cried. "Our goods duly passed the Customs officials at Algiers and the official said I need fear no further interference with my goods. Was not the Customs permit chalked on the tarpaulin?"

The lieutenant bowed again and said nothing.

"Why did you take my salt from the rumble, monsieur lieutenant?"

"To put it back again," responded the lieutenant blandly.

Nor could the cousins gain further information than that.

Henri would not move from the shed till he had seen every bar of salt replaced in the rumble, taking care that "the best bar" with the scratched crescent upon it, should take up the identical position at the base of the consignment, as Gaston Jambonne had decreed.

The cousins returned to their quarters under the guidance of a French private, but in the offing Tony caught sight of the agent of Gaston Jambonne who had brought them to the spot.

On the morrow the Crimson Caterpillar was bound to be in perfect condition, and Henri almost forgave the lieutenant seeing how efficiently the mechanics had cleaned, oiled and adjusted all the bearings. "He thought we were smugglers," explained Henri to his cousin, dismissing the subject, and waving a hearty farewell to the officers who saw them off.

"It is great gratification to find you true sons of France," shouted the lieutenant after them.

So once more the two intrepid motorists set their faces to the forlorn spaces ahead.

THE Crimson Caterpillar had not travelled far from Ouargla when Henri suddenly drew up.

The French youth pointed to a flat hill that dominated the sea of sand. "That is Gara Krima," he said, standing up in the car and saluting. "Thence the pioneers of France set out for the Niger. The Foureau-Lamy mission took two years on that journey, which we plan to accomplish in twenty days. Thus rapidly does Man conquer space and time, my brave one."

"Isn't it nearly lunch time?" was Tony's terse response. His cousin's Gallic sentimentality jarred on his own Saxon reticence; like most men of British blood, Tony grew more silent the more his emotion was stirred. Tony would counter Henri's eloquence with trivialities. Hence: "Isn't it nearly lunch time?"

"No, my cousin of stomach and no soul, we may not yet eat," was Henri's rejoinder. "Here we may study our maps."

The French youth, though prone to rhapsodise, was methodical and left as little to chance as Saharan expeditions permitted. He had maps of every section of his journey to Timbuctoo, and had carefully studied the work of the Citroën Expedition who had first accomplished the conquest of the Sahara by car. Each night of the prospective journey was scheduled to be spent at a particular spot so that Gaston Jambonne could follow his movements readily enough. And the Algerian trader himself had furnished information that was exclusive and proved marvellously accurate.

After leaving Ouargla the Crimson Caterpillar's next night was to be spent in the sand dunes of Kheshaaba, and the journey thither was, on the whole, somewhat monotonous.

"We are adrift on a desolate sea of sand," Henri remarked towards noon, "only the island of Gara Karim remains to direct our passage to the unknown wastes ahead where dangers lurk. It is indeed a sea of desolation wherein our gallant ship may be wrecked."

"Behold in the trough of the sea a shipwrecked mariner!" chaffingly cried Tony pointing to something that showed up like a tent on the monotonous sand plain ahead.

Yet was there no need to inspect that casualty of the desert closely. All was over; there was just a framework of bare bones, great curving ribs and a flat skull that reminded Tony of fossils of prehistoric animals seen at South Kensington Museum. The vultures, the jackals, the beetles and the ants had completed their work. Thirst and relentless heat had wrecked that ship of the desert, and its owner, leaving it to die, had continued his journey on another camel.

Soon Tony was to grow accustomed to such desert sights; indeed he grew almost to welcome them, for the skeletons of the camels indicated that the travellers were following customary routes across the wastes.

In the afternoon a yet more tragic relic came to the English boy's notice.

"See yonder, Henri," he said, handing his cousin his binoculars, "yonder is a stone cross."

Henri drew up and referred to a notebook. "Yes it is the grave of two brave missionaries of the Cross," he said, lifting his sun-helmet reverently. "The padres were massacred by Tuaregs, who have since raised this cross to the good fathers' memory. Everywhere in the desert lie the bones of the martyrs of Saharan progress, of missionaries, of scientists, of soldiers, of naturalists, of pioneers who gave their lives for the good of their Cause."

"I suppose we couldn't be classed as martyrs if we were killed," Tony slyly chaffed. "Dead traders aren't counted martyrs."

"I don't know, Tony," said Henri seriously. "Traders bring benefits to the lands whither they come in fair dealing. I believe that I can pray Le Bon Dieu to bless this our enterprise which brings life in the form of salt to a saltless land."

Yet had Henri Leprince known all, he would never have breathed that sentiment.

Strange and disappointing was their next experience.

"Look! Look!!" cried Henri, pointing through the shifting eddies of red sand stirred by the following wind. "A city of beauty in the wilderness, a very Nirvana in the howling wastes!"

Tony stared through the flickering fight. "The city ahead is not marked on our map? And where are the natives of this beautiful oasis?"

But even as the two cousins tried to focus the scene ahead—the purple palm groves, the shining lakes, the clumps of plantain, the fairy-like huts—it dissolved before their eyes. The purple palms merged in the purple of the horizon, the shining lake sank below the sand, the plantain clumps writhed like snakes and were whirled into nothingness, the huts danced to dissolution.

And only one spindly gum tree remained real in that mirage that had deceived them both.

Maybe it was a similar mirage that had lured a party of desert wayfarers to their doom, for not long after seeing the optical illusion of the mirage, Henri caused the Crimson Caterpillar to swerve in order to avoid something white half buried in the sand.

"Human skeletons," breathed Henri. "Seeking water where there was none, the poor beings, maybe white, maybe black, sank exhausted to the sand. See, one lies gazing at the sky from sightless sockets. And there rest two close together, hand still clasped in hand, brothers or chums perhaps."

"Or cousins," said Tony shuddering.

Henri sighed. "It happened long ago, for not a shred of clothing remains to prove their identity, and the bones are bleached white with sun and wind."

They gazed at the poor relics of humanity, then softly the car purred onward, its occupants silent with solemn thoughts.

The Crimson Caterpillar continued onward till nearly midnight, the way was clear before them and the going easy. But by that time the cousins had reached the limit of human endurance.

The tent was quickly rigged under the stars; it was their first night in the open. Tony found it surprisingly cold; the thermometer registered only 39 degrees Fahrenheit.

"I made fun of the blankets you were bringing, Henri," said Tony as he snuggled down into his hip-hole in the sand. "But it would have been no joke without them."

"If fuel were procurable, we would have made a fire, and been only too glad of it," Henri replied from out the depths of his blanket. "And the fire would have been useful to scare off jackals; though, on the other hand, it might have attracted desert robbers."

Tony grunted but did not continue the conversation, for in two minutes he was asleep, and Henri followed in three minutes with a snore.

An hour later, as the travellers lay there in profound sleep, a turbaned head appeared above the adjacent sand dune. He was black veiled so that only his restless eyes could be seen, and was clothed in a blue robe, carrying a long-shafted spear in one hand, a leather buckler in the other.

Below, in the hollow of the sand dunes, a white camel munched at scanty tufts of drinn.

The warrior grunted and crept nearer the sleepers. The stars shone brightly and showed the Crimson Caterpillar outlined against the sand.

The warrior placed his spear and shield on the ground, and, standing erect, revealed the sword, with its cross-guarded hilt, hanging by his side.

With incredible deftness he drew the double-edged weapon from its sheath and raised it before his litham, or black veil. He advanced with the silent step that only the desert-bred can take.

"El hamdulillah!" he murmured softly. ("All praise to Allah!")

A hyena howled dismally in the distance.

Whilst the Tuareg with the double-edged sword drew momentarily nearer the unconscious cousins.

TONY MASE, when at his Public School in England, had been a Scout, and, therefore, on first rising and prospecting around their camping place, he promptly found traces of their visitor of the night before.

"Hello! we are shadowed still," he cried to his cousin, showing him the spot where the Tuareg warrior had lain.

The French youth saw less than his Scout cousin; and indeed he felt guilty for not having arranged to keep watch throughout the night in turns, so he put the rosiest complexion on the discovery. "If a visitor came, which I much doubt, he was probably a desert policeman who was looking after our welfare."

"Hump!" growled Tony, stooping low and seeking further signs in the swiftly shifting sand.

A slight wind was obscuring the footmarks, but the Scout was able to follow them to the place where the white camel had munched the drinn.

"The spy had a steed," he explained, pointing to unmistakable signs.

"A meharist," was Henri's verdict. "One of the Saharan goumiers, or native couriers on camels, trained by France to guard the wells or convey messages over immense tracts of uncharted desert on their slim-legged meharis. Once they were caravan robbers; France has converted them into caravan protectors. For see, my Tony, how he came and protected us whilst we slept."

"Bet he came and—bolted!" was Tony's explanation. "He was a mere frightened villager from back of the beyond, and, seeing the Crimson Caterpillar looming up in the moonlight, and hearing you snore, thought he had come on a dragon's lair."

But neither Henri nor Tony had given a correct solution of the Tuareg's visit: the agents of the House Jambonne were not all of the mercantile fraternity!

A breakfast of dried dates, bread and condensed milk with water was taken by the travellers, and then Henri proceeded to make observations and map out the day's run by the aid of compass and rising sun, Tony meantime giving the Crimson Caterpillar her breakfast of petrol and water.

So at length the car sped on her way through the immense sand dimes of Kheshaaba, making for Inifel and its fort, which Henri hoped to reach that night.

Spite of an hour's delay in getting clear of the maze of sand dunes, the cousins came to the Wadi Meya in the course of the afternoon.

It was a great relief to eyes grown sore with gazing at the monotonous, heat-radiating sand to look once again on green vegetation, on great gum-trees and clumps of acacia bushes. The Wadi Meya seemed a most beautiful park after the dreary wastes of the sand dunes. At the wells in the valley the motorists made a halt.

A solitary Tuareg on a white camel rode out from concealment, and without comment proceeded to help them get water from the well. Henri tried to speak with him, but the warrior mumbled behind his black litham in a tongue neither traveller could understand.

Tony laughed. "Depend upon it, Henri, that's your goumier who visited us last night."

"He is no meharist of France, he wears not her uniform," retorted Henri. "He is a solitary meharist, a Tuareg out of the Hoggar, looking for baksheesh."

When the French youth, however, offered their helper a silver coin, the Tuareg spurned it, lifted his shield in salutation, and rode off into the silent spaces of the desert. The representatives of the House Jambonne did not seek payment.

The Crimson Caterpillar having been given a drink of water as well as her drivers, the Wadi Meya was reluctantly left, and she faced the desert which had swallowed up their helper at the well.

"Maybe he is in ambush, Henri, waiting to entrap us amongst yonder piles of stone," Tony said an hour later.

But Henri explained that even the swiftest mehari could not have kept pace with the gallant Crimson Caterpillar, and could not possibly be ahead of them now. "As for those stones I don't understand them."

"A Stonehenge in the desert!" explained Tony, as the car drew up alongside a great circle of stones piled at regular intervals.

"No, Tony," contradicted Henri consulting a handbook, "it is historic, not prehistoric. Here the retreat of a Tuareg army, ladened with loot, was cut off by loyal Chaambas. Each brave warrior supplied himself with a small heap of stones, so that when javelins and arrows were exhausted he could still fight on with stones. And to commemorate the great victory achieved that day when the evil marauders were slain to a man, the Camel Guards, when they pass this way, always add further stones to the original tiny heaps of the warriors."

Towards evening the ground caused the Crimson Caterpillar some considerable difficulty. The caterpillars sank deep in the fine marl, and the wheels sent whirling skywards clouds of white dust that must have given notice of their arrival to watchers in Fort Inifel.

But there was no detachment of the Foreign Legion or the Camel Guards occupying the Fort when, at dusk, the cousins came to Inifel. The only occupants of the Fort were two wireless operators.

"There is a mad message awaiting you of the car," announced one of the men.

It was in cipher, and Henri decoded it with little difficulty. It was similar in purport to the message received at Touggourt. "Avoid all white men, and proceed at topmost speed to deliver the salt."

Said Tony lightly: "One would think the delivery of a few bars of salt a matter of life or death."

"It often is—to desert folk," said Henri gravely.

By the light of wicks floating in oil Henri set down the coded message for the wireless operators of the Foreign Legion to transmit to the factor in Algiers.

"The Customs troubled us at Ouargla, but all well and we go on quickly to our goal," was Henri's information which set the half-caste in Algiers stumping up and down his secret room, with the giant Kabyle sitting outside trembling.

Soon the Kabyle was summoned to accompany his master to the wireless depot, and a message was sent to an Arab agent of the House Jambonne in Taman Rasset.

Henri Leprince had been instructed to avoid this place, but must needs pass within some twenty miles. Panicky instructions were sent to the Taman Rasset agent to intercept the Crimson Caterpillar and deliver the following message: "The best bar must be delivered intact to our customer in Tim or fees will not be paid."

Jambonne's agent instructed an Arab, who had never sighted a motor car or seen an illustration of one, to take a written message to the above purport.

The ignorant Arab expected some sort of quadruped that rolled across the desert, an animal which had no legs, and snorted as it emitted its breath from its tail. Whether the Arab actually sighted the Crimson Caterpillar, or whether the man failed to intercept the car, I cannot say, but Henri never received the frantic message.

Certainly Tony, when passing through the district adjoining Taman Rasset, saw a motionless Arab meharist suddenly spring into life to flee incontinently from the shadow car gliding ghostily over the moonlit desert sand.

But this is anticipating the Crimson Caterpillar's progress. We left her at the deserted fort of Inifel, where the two French wireless operators found accommodation for both car and cousins.

It was the soundest sleep that the two travellers had enjoyed since leaving Touggourt, and they slept till the sun was high in the sky.

For the next few days, indeed, the Crimson Caterpillar went onward till late at night, the travellers having learnt that it was best to rest for a long period during the sweltering hours when the sun held sway. Under the light of moon or stars, with their headlights gleaming like silver on the sand, the car could make cautious progress without the engine getting overheated, as it invariably did in the torrid atmosphere of the Saharan noon.

So, by stony plateau, through gorges and defiles, by deserted bordj, through a land of thirst where camel and rider had met death in the past, over a yellow-red plain where the wheels of the car would have sunk hopelessly but for her caterpillars, by Saharan village whose kaid came forth at dawn to wish them Sabbagh el Kheir ("the top of the morning")—on, on to where the land grew greener and irrigation canals proved the presence of man, the travellers came to Insalah, the great oasis of the desert, with its palm groves and crenellated white walls.

There, however, their stay was only long enough to allow a skilled mechanic to overhaul the car and adjust the self-starter, whilst Henri and Tony attended to the purchase of provisions for the onward journey.

The Crimson Caterpillar, reconditioned, with full stocks of water and petrol, gaily swept onward from Insalah across the immense plain ahead, where the pale ochre of the desert imperceptibly intermingled with the bronze blue of the firmament. Twenty miles an hour was the Crimson Caterpillar's average that day and night.

Soon mountains crept up the skyline to the left. On inquiry Tony was told: "They are the mountain ranges of a land bigger than your Wales, mountains that are ten thousand feet in height. A whole country which was put down on the map as an 'oasis'!"

"An oasis as big as England!"

"Undoubtedly," declared Henri. "Your British traveller Buchanan climbed to six thousand feet in these mountains, and has written records of this little known land. Away in its inaccessible interior dwell the Tuareg raiders, who still pay loose allegiance to La Belle France."

"It's a jolly good thing we haven't to cross that country," Tony remarked as the mountains loomed higher and higher to their left.

"We may have to skirt some foothills of the Hoggar and negotiate some gullies before we once more reach the desert proper, my Tony," Henri explained.

Soon the Crimson Caterpillar was cruising quite close to high cliffs, and then she suddenly went gliding down through a narrow defile where the temperature equalled that of an oven.

It was not the sort of place to break down in the heat of the day, but some malign influence seemed to pursue the Crimson Caterpillar at this stage of her journey. First she got jammed at a narrow turn in the precipitous pass, and it took half an hour to get her free without damage to her chassis. Then, with the fearful heat of the inferno between the cliffs, the radiator boiled till it was useless pouring in more water.

"We must stop and cool," declared Henri, sweat pouring in a cascade from his face.

"Can one cool inside a furnace?" queried Tony, mopping his brow with a blanket.

An appreciable lowering of temperature in the radiator presently allowed the Crimson Caterpillar to proceed over the boulders and rocks of the narrow pass.

And then a perished tube caused one of the tyres to go flat.

It was another hour and a half before the cousins had changed tubes.

"This is our worst day yet," said an exhausted Henri as the sun went down and found the Crimson Caterpillar still floundering through the rocky defiles over the boulder-strewn way.

Tony was driving, in order to give Henri a rest, and he tried to force some pace out of the sorely tried car, but midnight found the travellers still struggling with the difficulties of the defiles.

"We must give up the contest for the present, Tony," said Henri as he held his eyelids open to prevent himself falling to sleep.

Tony drew up in the shadow of a rock that was shaped like a negro's head. It was known to the marauding Tuaregs as the Black Goblin Eyrie.

Tony tumbled from his seat, so stiff that he actually rolled to the sand.

"And this, Henri, would you believe me? is Christmas Eve," cried Tony. "Personally I am not going to hang up my stocking or wait to spy on Father Christmas."

"It is certain that we ought to watch in turn, for the Tuaregs descend from the mountains to raid passing caravans at this spot. I did not point out certain gruesome relics we passed an hour ago, mon brave," said Henri, yawning with his head lolling helplessly on his slumped shoulders.

"I would rather be murdered than go without sleep," growled Tony, settling down in the sand.

"Pray the Good Lord that no evil visitor come here this night, Tony," breathed Henri reverently. "It is certain that neither of us can keep an eye open another minute."

And so it was that when, in the grey of Christmas dawn, the Veiled Ones came to the Black Goblin Eyrie, they found two youths deep in dreamless slumber.

DOG-TIRED, Tony and Henri had not pitched tent, but flung themselves down in the sand, where the moon flung the shadow of the Black Goblin Eyrie over them like a shroud.

The cliffs of the rugged gorge rose tier on tier to the sky. But from the Goblin Rock Eyrie to the desert wastes a dozen miles ahead the gorge ran due east.

Over the edge of that distant world of desert crept the harbingers of coming day.

It was the first flicker of dawn on Tony Mase's eyelids that made the English boy stir. He woke from a dream in which Gaston Jambonne had stood over him threatening to brain him with a bar of salt unless he showed the hiding-place of the man with the crooked nose. Even when he woke he could not disabuse himself of the idea that he was menaced—that someone was watching him.

He collected his scared thoughts, and stole a glance through half-opened lids at his cousin Henri. But his fellow-traveller lay face upward to the sky, breathing loudly, still asleep. Henri was not watching him. But someone was!

Tony turned on his side, saw the distant patch of sky far away on the verge of the desert, watched the rays of light deepen in the funnel of the ravine stretching eastward.

Suddenly the golden orb of the sun blazed up over the rim of the desert, shooting shafts of light to the very zenith of the heavens, chasing the last star from the sky.

There came a sudden stir, and Tony looked up to see the ravine palpitate with life—human life. He shook Henri's shoulder, which was silhouetted against the light.

"They've come," the English boy cried.

"Who?" queried Henri sleepily, peering blindly through half-opened lids.

"I don't know," Tony responded, and pointed to row after row of robed and veiled figures grouped before the Crimson Caterpillar.

"Pinch me, Tony, to prove I am not astride a nightmare," cried Henri. And, his cousin acting forthwith, sprang to his feet with a yell. "The Veiled Ones!"

Indeed it was a sight to make the bravest tremble. Immobile figures which had seemed part of the sand in the darkness, now flashed into life as the rays of the rising sun reached them.

"Thousands of them—the robbers of the desert," exclaimed Henri aghast. Which was an exaggeration, though an excusable one.

Certainly a hundred pair of eyes were focused on the waking youths, eyes that looked over the black litham of the Tuareg—the sinister warrior of the Sahara. The black webbing of the litham was wound round and round the lower part of the head and extended in thick folds to the chest, whilst above the brows was a turban, so that only a narrow strip of white face was visible. From shoulder to sandalled feet a robe of faded blue covered their virile forms. Each man wore suspended from his neck a black cord from which hung a cluster of small leather wallets—"amulets of Allah," as the Mussulman termed them, for the Tuaregs were Mahomedans of doubtful orthodoxy. At each warrior's side was girded his sword in a leather sheath. In one hand he bore a shield in the other a spear.

Henri recovered his presence of mind. "Sabbagh el Kheir. Allah karim," was his Arabic greeting to the assembled host.

There came a low chorus in response. It was in Tamashek, the language of the Tuaregs.

Then in unison the Tuaregs stooped to remove their sandals; it was the time of morning prayer.

"What are they going to do?" asked Tony.

"What we ought also to do," responded Henri solemnly.

The Veiled Ones, having removed their sandals, turned their bodies to face Mecca, extended arms above their head, crossed hands over the chest, repeated prayers from the Koran, then, placing hands on knees, they knelt and touched the sand with their foreheads. All of which was executed with the utmost reverence, to the accompaniment of a sort of chant.

"Perhaps it is as well that we imitate the heathen, only in our Christian way," said Henri quietly.

"Right-ho!" agreed Tony shyly.

So in that lonely desert place, morning prayers to their Maker rose from Mussulman and Christian alike.

When Tony opened his eyes again and rose to his feet, he felt that all fear had vanished, and he was ready to face whatever happenings this gathering of armed nomads might precipitate.

Prayer completed, the Tuaregs turned about and filed slowly past the Crimson Caterpillar, each warrior placing his finger tips to his brow as he passed the cousins and strode solemnly back to the bend in the defile where the Black Goblin Eyrie cast deep shadows.

"Doesn't look as if they meant to murder us, Henri," said Tony cheerfully. "They are riding off. Listen!"

There came to the cousins' ears the sound of grunts and swearing, of camels being released from the knee ropes that had tethered them.

"They are preparing to carry us off into captivity, my poor Tony," wailed the French youth. "But I'll punch your head, my boy, if you as much as flicker an eyebrow in fear."

"Where will they take us?"

"Probably to some inaccessible mountain retreat where Europeans have never penetrated, my poor cousin. Oh! Tony, why did I bring you on this journey of terror?"

But Tony had sprung to the driving wheel of the Crimson Caterpillar. "They haven't collared us yet," he cried. "Jump in, Henri." The French youth, however, was not quick enough.

Swiftly four stalwart Tuaregs came riding up on camels, filing by the car, then turning around and completely blocking the pass. From the shadows of the Black Goblin Eyrie came the roll of the tobol, or war drum.

The four riders bore the leather shield, the tapering spear, the girded sword. Henri and Tony grasped the revolvers in their pockets; they could not hope to overcome the Tuaregs, but they determined to sell their lives dearly.

The tobol rolled unceasingly.

One of the meharists, a chief to judge by his noble bearing and distinctive headgear, spoke. His fearless eyes singled out Henri.

"Hast thou anything to say to us, O Frank of the Engine?" he demanded in passably good French.

"Nothing, O valiant leader," responded Henri calmly. "Save only that I travel hence on my employer's business, and permit none to stay me."

These bold words seemed to please the Tuareg chief. "Thou art a man, though but a fledgling in years. Give us but a bar of salt, and you may continue your pilgrimage."

"Nay, chief, the salt is not mine," answered Henri. "It is the property of one Gaston Jambonne, a factor of Algiers, and we deliver the salt to his agent in Timbuctoo."

"Well spoken, O Frank of the Engine. Proceed on thy way." And the Tuaregs, at a word from their chief, filed past the Crimson Caterpillar to disappear in the shadows about the Black Goblin Eyrie.

"Now you see, my Tony, how precious a bar of salt may be, when a Tuareg army beg for a bar," said Henri, seating himself alongside his cousin.

"Tosh!" exclaimed Tony. "If they really wanted a bar of salt, they had only to take it. We couldn't have stopped them."

"There is honour even among Tuareg raiders, Tony," said Henri. "Above all when it concerns so precious a commodity as salt."

"Your explanation isn't good enough," retorted an interested English boy. "I want to see more of our friends the Tuaregs."

And before Henri could prevent him, Tony had jumped from the car to the sand—to go running to the bend in the pass where the camels had been tethered.

The band, however, were already on their way whence they had come. Such as were not mounted were summoning their steeds by name.

"Owrak!"

"Ajarnelel!"

"Tebzow!"

"Aweena!"

"Korurimi!"

And the beautiful, fleet-footed creatures, with their big, brown, liquid eyes, gave answering grunts to their masters' cries.

Releasing the knee ropes, the owner slapped his beloved steed's flank. The faithful camel knelt, and the Tuareg adjusted the slender riding saddle of his kneeling friend. No sooner perched on his saddle was the warrior than the mehari rose and, soft padding, swayed off with long strides after its companions. The riders, with words of endearment and gentle pressure of sandalled feet at the nape of the camel's neck, rose and dipped with every stride of the strange steed of the desert.