RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

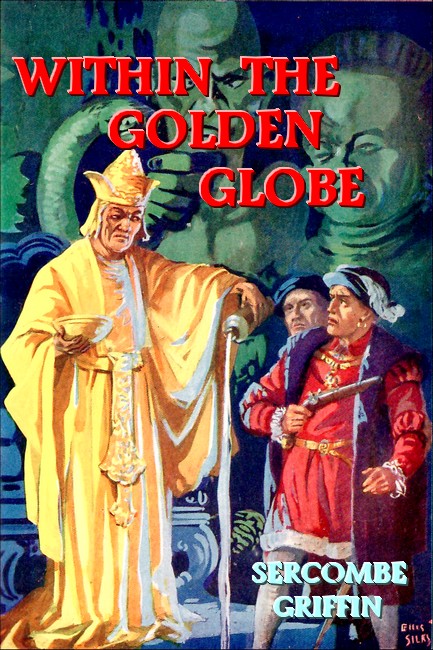

Dust Jacket of "Within the Golden Globe,"

George Harrap & Co., London, 1934 (restored)

Cover of "Within the Golden Globe,"

George Harrap & Co., London, 1934

Title Page of "Within the Golden Globe,"

George Harrap & Co., London, 1934

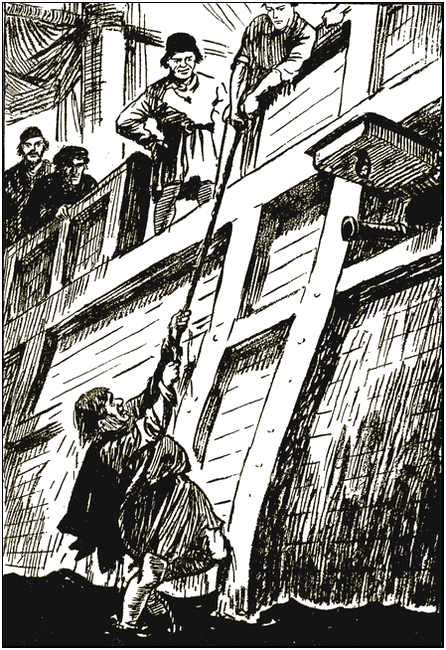

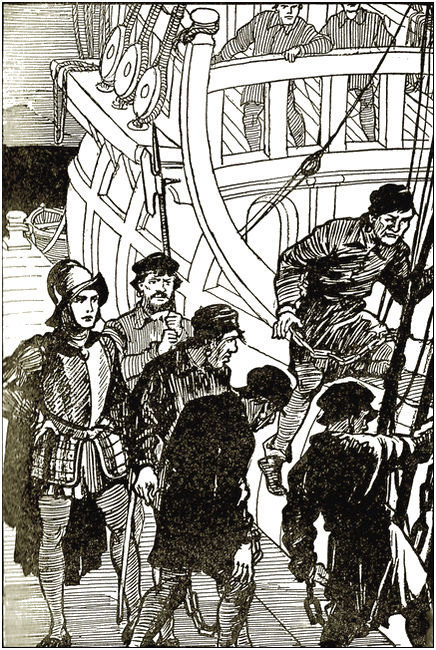

Frontispiece.

Then he slowly turned the flask upside down.

"IN truth, nephew Ralph, we have ventured forth once and again since first we met in distant Martavan, yet our doings have been prosaic enough," Roger Coombe remarked, as he lounged back on the settle, his thin, nervous hands held out towards the blazing logs on the hearth. "Save for our brush with the Barbary pirates nigh the Pillars of Hercules, and our share in repulsing the French raiders at Seaford, we have lived as lazily as fat King Hal at Hampton Court."

"Hush!" whispered Ralph, listening intently, for his keen young ears had caught the sound of footsteps ascending the stairs to the apartment where the two sat in their home in Bristol town. "Remember, Uncle, that men have suffered death for daring to assert that King Henry was like to die."

"Pah!" the fearless Roger replied. "The eighth Henry is become a very tyrant now that corpulence and disease have him prisoner. But his cruel hands and his Star Chamber cannot get hold of us here away in the West of England."

"Hush!" again hissed Ralph. "Verily, sir, some one cometh."

The door of the chamber swung suddenly open, and swiftly closed again.

Before the Coombes stood a slim, beady-eyed man clad in black velvet doublet and hose, a black velvet cap coming down about his clean-shaven face, black pointed cloth shoon enabling him to move noiselessly.

"Roger Coombe?" he inquired, in soft, silky tones, his eyes fixed on the elder man as if to read his very soul.

"Yea," responded Roger sleepily, forthwith hooding his eyes under heavy lids; he was a consummate actor was Roger Coombe. "Prithee pardon my servitor for failing to conduct thee hither with due deference."

"I come secretly," purred the stranger in black. "And having concluded my business with thee, depart as stealthily. Yet know"—and the silky tones grew hard and menacing—"that life and death are in the balances.... Dismiss this youth, and I will confide to thee that which thou must do forthwith."

Roger Coombe appeared to stifle a yawn.

"Be seated, good stranger. My nephew is my confidant in all my affairs, companion in all my adventures, so—"

"Yet must he leave our presence," urged the man in black, still standing.

Ralph hesitated, then, seeing his uncle did not speak, tiptoed, and unhitched from the chimney-piece a hanging dagger brought by the Coombes from beyond the Indies. This fearsome- looking weapon he placed at his uncle's right hand on the settle.

"Permit me to retire, Uncle," Ralph said.

"Go, nephew, yet remain within hearing. Perchance our guest may need refreshment."

"I need none," said the man in black velvet softly. "Yet, ere thy fearful nephew withdraw, let him know that no harm is intended thee or himself. Also know, both of ye, that harm may not come to me, for I am shielded by the Star Chamber."

At mention of this dreaded, despotic Court, which had committed so many judicial murders, Ralph Coombe shuddered.

"Where no harm is intended, gentle stranger," drawled Roger Coombe, "no fear is felt. Go, nephew."

Reluctantly the youth passed to the door; he feared the man in black velvet, shuddered at his stealthy tread, and mistrusted the purring tones, with their undercurrent of menace.

Ralph's fears were scarcely lessened when, in the passage from the open door, he found a man-at-arms on guard without. The black-garbed visitor had made certain there should be no eavesdropping.

Ralph passed into the front room, which overlooked the main street, every sense alert, seeking the menservants who did the work of the house. His uncle, himself, and those two lackeys were the only ones inhabiting the house on St Mary-le-Port, which was the seafarers' home.

It was ten o'night, and save for a few roisterers at the tavern by the waterside every one was abed.

How had the sinister stranger gained admission? The two servants had not come, as the custom was, to announce: "All—is—well! The house—is—locked—up." Swiftly Ralph stepped to the casements, then, hearing a movement on the floor above, turned, and ran lightly upstairs.

"Tyrrell! Amory!" he whispered loudly, as he tapped upon their bedroom door. "Are you there?"

"Abed and forbidden to come forth, young master," answered Tyrrell, his voice broken with terror. "'Tis the Star Chamber that forced us to fail in our devoirs to our employer."

At mention of this instrument of cruel tyranny Ralph Coombe must needs be satisfied of his servants' fidelity, for none might resist the Star Chamber and live!

But—but—but what had the Star Chamber to do with Roger Coombe? And—and—and what was happening in that downstair sitting-room to which the black-velveted stranger had gained entry?

Ralph would have rejoined his uncle forthwith, but the man-at- arms forbade, standing across the passage and pointing the youth to the front room overlooking the street.

Again he passed to the casements, and this time he unlatched them and looked forth into the night.

Dimly he made out a motionless rider at the front doorway of the house, a musket in the holster at his side, a glinting helmet on his head. In his hands were bunched up the reins of two riderless steeds, those of the two men within the house, as Ralph rightly guessed.

Hearing a noise behind him, he sprang back from the window, to see the door of the chamber swiftly close—to hear a key rasp in the lock.

He was prisoned.

And what might be happening to that fearless uncle of his? The Coombes were inured to peril under the open skies, but this sinister messenger of the Star Chamber, who had crept to their very fireside, Ralph feared, he scarce knew why.

He rattled the handle of the door, but found neither exit nor response to his demand to be freed.

And lo! when once again he flung wide the casements the soldier on horseback below, hitching the reins of the riderless horses over the pommel of his saddle, threatened Ralph with his musket.

A night-watchman, carrying a lantern in one hand and in the other a truncheon, was chanting: "All—is—well! Half- past ten on a frosty Jan'ry night! All—is—well!" when he caught sight of Ralph beckoning.

Thereupon he rushed towards the mounted man, waving aloft his lantern and brandishing his truncheon bravely.

The soldier held out something that glinted in the moonlight, a metal star that he dangled in the watchman's eyes.

"All is well!" hurriedly chanted the intimidated man with the truncheon. "Half-past ten on a frosty Jan'ry night! All—is—well!"

"Nay, 'tisn't," shouted an indignant Ralph, "when men are prisoned in their own houses."

But he was menaced again by the mounted man, and withdrew within the room.

There was the clink of a spur in the passage without, and, listening intently, Ralph thought he could detect the soft, cat- like tread of the man in black velvet.

The baleful visitors were departing.

There was the clatter of hooves on the cobbles of the street, then the dree-op! dree-op! of receding horseshoes.

Ralph put out his head—to glimpse the backs of two soldiers disappearing into the night, and he sensed rather than saw the sinister figure in black velvet who rode before them.

Again the rasp of key in lock! And this time a door flung wide.

Roger Coombe stood in the entry. His eyes gleamed with excitement, every inch of him seemed to be quivering with keen delight.

"We go on a yet greater adventure than ever yet we have essayed, nephew Ralph!" he cried.

"Whither?"

"To far Cathay, thou son of Cathay Coombe," Ralph's uncle cried, reminding the boy of the exploits of the father who had died on his last voyage to the Far East.

"When, Uncle?"

"Immediately 'Zekiel Zobb can join us, Ralph."

"For what purpose, sir?"

"That I may not tell thee, lad," Roger Coombe replied, his face grown suddenly grave. "But I can promise thee we will, Deo volente, tread where Englishmen never yet have trod, see sights no adventurer yet has seen, hear strange tongues and barbaric music such as no one in these islands yet has heard, and return with such a treasure as will astonish all his Majesty's subjects."

"Is that what Black Velvet promises, Uncle?"

"Yea, and in earnest of his promises he will deposit one thousand golden guineas with Master Nicholas Morris, thy guardian and my thrice-worthy friend, the which thousand guineas are to be doubled when we return to England with our mission accomplished."

"And why has Black Velvet chosen thee for the mission, Uncle?" the youth asked.

"He tells me it has come even to the ears of the King himself how that we went where Englishmen never yet had gone when we tracked that Treasure of Gems in far-off Pegu. Wherefore Black Velvet, as thou hast dubbed him, says there are no others that may undertake this new quest of his, none so fitted for the task as the Coombes."

"I trust this Black Velvet will do all that he promises," Ralph said.

"In any case, dear nephew, 'tis a great adventure," declared Roger Coombe.

"And therefore thou and I, Uncle, must undertake it, guineas or no guineas."

But on the morrow, as the mysterious visitor had promised, lo! there came to the house of Nicholas Morris a cavalcade of his Majesty's musketeers, and they left with that worthy merchant a thousand golden guineas!

A SWIFT messenger was dispatched to fetch Ezekiel Zobb to Bristol Town. Along the shores of the Severn Sea to the port of Watchet the man galloped, with but short rest for his horse, seeking the faithful servitor, without whom the Coombes undertook no sea venture.

At Watchet the tubby little seaman had been celebrating Christmas among the companions of his boyhood, telling them strange stories of the wondrous new lands beyond the Indies, where he had been Court fool to a mighty Mongolian king.

The messenger cantered on to the quay when Zobb was in the midst of his recital. But instantly the little sailorman ceased to speak as the newcomer cried, "I seek Ezekiel Zobb!"

Zobb dug a fat thumb into his own chest.

"Roger Coombe wants thee," the messenger cried, "in the city of Bristol!"

"Zhall I get up behind thee, vriend?" the little mariner queried. "Zure az me name is 'Zekiel Zobb I be ready to gallop to Bristow Town thic zecond."

"Pray, gallant seaman," responded the weary horseman, "remember my horse and I have travelled without stint, and the gallant beast—not to mention my poor self—must needs eat and sleep ere we return."

"Zartain zure ye zhall," responded the faithful Zobb, "but I be goin' thic zelfzame zecond if zo be I can vind a hoss."

The messenger had come provided with money. Zobb's companions provided the mule.

So Zobb arrived in Bristol Town by dint of travelling all night—in spite of the footpads who put a bullet through his cap—surprising the Coombes, who were as yet not ready to set out.

"Here I be, zonny!" he cried, coming up behind Ralph, and clapping his horny hand on his young master's shoulder.

Ralph dropped the barrel of cured pork he was carrying to lade the pack-horses. "Dear old comrade!" he cried when he had got over his surprise. "We're off on high adventure with Uncle Roger."

"An' high time, too! Zure as me name is 'Zekiel Zobb, I be zinkin' in the doldrums, be grown dull as ditchwater vor lack of veeling me life is in danger. When there's new worlds to be vound, zartain zure 'tiz no time vor younkers like us to be droning away our time in idleness. Let's dance a zuccess to our new venture, Ralph zonny."

Whereupon in that crowded warehouse the volatile little seaman grasped Ralph's hands, and the two executed a sailor's hornpipe, scattering Nicholas Morris's serving men to right and left, and almost causing the pack-horses and sumpter-mules outside to stampede.

The departure of the party journeying to London was hastened. Roger Coombe was the leader of the convoy, which consisted chiefly of merchant adventurers and their merchandise. But there were others—a lady returning to Court, riding in a horse- litter, two other ladies, riding side-saddle, accompanied by their husbands and followed by servants, who rode pillion, man and maid. And there were a number of monks, with staff in one hand and rosary in the other, who trudged at the heels of the party, unfortunate men who had been driven out of their cloistered retreats at the time of the suppression of the monasteries.

It was one of these cowled and robed wayfarers that early sought to attach himself to Ralph, who rode a pony.

"Thou art a brave young rider," he said.

"I am of the Reformed religion," Ralph replied, hoping to fling off the monk, who clung to his pony's bridle. He did not trust those fierce black eyes that peered up at him from under the close-drawn cowl.

"And peradventure, son," whispered the man in the monk's attire, "thou art nearer the Truth than any one of these berobed wayfarers that follow thy train."

Ralph conned the man keenly; it was not uncommon to find a monk, turned adrift in an unsympathetic world, ready to change his belief if thereby he could find a living.

"What do you want?" Ralph asked bluntly.

The fierce black eyes blazed, but with an effort the man controlled himself, and quietly asked, keeping his eyes fixed on Ralph's face, "Whither dost thou travel, son?"

And Ralph, scarce knowing what possessed him, was about to reply meekly enough when Roger Coombe came cantering back from the van of the cavalcade.

"Art making friends with one of the black-frocks?" Roger Coombe queried, a trifle testy in his manner.

Confused, Ralph passed a hand over his brow.

"Verily I believe the fellow did bewitch me. 'Twas not I who made friends with the monk, but the monk who forced his company on me, Uncle."

"Did he ask whither we were bound, Ralph?" queried Roger Coombe, looking after the man as he slipped off betwixt pack- horses and case-wares.

"Yea, Uncle, he questioned whither we travelled."

"Of a truth I knew it!" exclaimed Roger Coombe. "There be those who mark our movements, though whether they be spies of the Star Chamber or enemies seeking to frustrate our purpose I cannot guess."

"What do they seek, Uncle Roger?"

The merchant adventurer smiled an enigma of a smile.

"They seek that which they may not find," he said, hooding his eyes till but the veriest twinkle shone forth. "I have but now warned 'Zekiel Zobb to attend to nought else but his mules, and to converse with no man. Our destination must remain a profound secret."

"Seeing, good Uncle, I know not the name of the city that we seek—if city it be—I am scarce likely to betray our destination."

"Thou knowest, Ralph, that we travel to far Cathay," whispered Roger Coombe. "That fact must remain a profound secret. In due course I will tell thee more. 'Tis not that I mistrust Zobb or thyself, but I know there be those who would not stop at torture to extract the secret that is hidden in my brain. 'Tis mighty difficult for the genial 'Zekiel to keep silent."

Indeed, had the Coombes but known it, at that very moment a man in monkish garb, with fierce black eyes, was helping Zobb to hoist a fallen bale back on to a sumpter-mule's rump.

"Thou earnest much goods to London Town, son," said the seeming monk when the task had been accomplished, and he surveyed the string of twenty beasts under the rollicking seaman's charge. "Surely thou dost travel farther!"

Zobb was seldom serious.

"Yea, holy father, needs must we carry a right royal load, zeeing we be calling on King Harry at Hampton Court."

The fierce black eyes gleamed expectantly, and he swiftly questioned, "Thou dost visit Hampton Court, son?"

"Maybe and maybe not, holy father," responded Zobb, with a wink of the farthermost eye. "An' if thou wilt promise to impose no penance, zure I don't mind runnin' up a score in the matter o' lies. Mayhap I be bozom crony wi' comrade Harry, both being inclined to corpulence, an' his nose being as knobbly as mine."

"Have a care, son!" breathed the monk in the seaman's ear. "'Tis high treason to insult his puissant Majesty. The Star Chamber has made away with men, so that not a hair remained to prove they had lived, for lesser offence than thine.... What is the mission of thy master, Roger Coombe?"

Zobb recalled the advice Roger had given him but five minutes agone, and answered, "Me name be Jerry Tellnaught, and me maizter's mission to make meat-patties vor King Harry at Hampton Court."

A vindictive look crossed the face beneath the cowl. "Dost jest with me?" the man barked.

"Maybe!" laughed Zobb, and sprung athwart his mule, to canter to the head of the cavalcade, where the leading horse, a veteran of the highways, went stolidly on its way, shaking its head ever and anon, as if it knew full well that the bell attached to its bridle-rein must ring to warn travellers of an approaching convoy and to guide its fellow quadrupeds on their onward way.

'Zekiel Zobb might have been less merry had he heard the words of the supposed monk muttered in his thick black beard. "'Tis ill work to jest with Anthony Peke, as thou shalt learn ere another sun arises, wanton sailor man."

Somewhere on the downs of Gloucestershire the wayfaring monks stayed their journey, weary from their walking. There they would wait till another convoy passed on its way, giving them protection for a farther stage of their journey to the capital. But not every man garbed as a monk stayed in that Gloucester village; one, his habit tucked about his hips, galloped forth on a waiting horse in the wake of the continuing convoy. Yet before he sighted it he turned aside, and in a hollow of the downs found the party of horsemen that he sought.

It was late in the day when the Coombes and their travelling companions put up for the night at the inn not far from Newbury.

Roger, Ralph, and some half-dozen other merchant adventurers shared the sleeping chamber of the small hostelry, the ladies jointly sleeping in another apartment. The male servants found quarters in tap-room and kitchen, while Zobb and two others mounted guard over mules and horses in the barn. The three worthy fellows arranged to keep watch in turn.

It was in the small hours that 'Zekiel Zobb, taking his turn at slumber, awoke to find a hand clapped over his mouth, while two stout fellows held him in their muscular grip.

"Keep silent, and all will be well," hissed one in his ear. "Shout, and thy weasand shall be slit."

Zobb made a grimace, finding he was powerless. By the feeble light of a lantern he was able to see that the other two watchmen had been surprised and were in similar plight to himself.

There were other sturdy fellows present, and outside the barn Zobb could hear the champing of bits, the stamp of hooves. The strangers fell to examining the baggage of the Coombes—theirs, and not the baggage of the other travellers!

Zobb was gagged, and could ask questions only with his eyes.

Presently there came to him one garbed as a monk, fierce black eyes gleaming forth from under the cowl.

"Thou didst jest with me yester morn, son," he said, in menacing tones. "Yet know now that my business is no matter for jest. 'Tis life! And also death for such as disobey. And reward for thee if thou dost play thy part. There be golden guineas for thee if thou wilt but show us what we seek. Canst thou tell me where Roger Coombe keeps his private matters—in which load?"

Zobb nodded, but there was a twinkle of laughter in his eyes which should have warned Anthony Peke that 'Zekiel would not betray his master.

The gag was removed from about Zobb's mouth, though he was still held in the grip of two guards.

"Zartain zure I ought not to tell thee, holy father, where zuch things be hid," the demure-looking little mariner said. "But they be in the bottom-most bundle yonder under the case-ware. Only have a care the mules don't kick thee, they don't relish being disturbed in their dreams."

To Zobb's disappointment he was promptly gagged again, and the night-riders made a simultaneous attack upon the pile of baggage under the big cart near which the mules were tethered.

The alert little mariner had counted much on the commotion that might arise. But Anthony Peke was no bungler. The barn door was tightly closed and guarded. And though one of the mules let out with its back legs on being disturbed, the man who was kicked was swiftly hushed by the monk himself.

At length the bale indicated by Zobb was hauled forth and opened. To reveal—an assortment of under-garments!

Anthony Peke strode up to the sailorman, who had assumed a look worthy of a village idiot.

"'Tis papers we seek—not shifts!" he exclaimed in fierce anger, removing the gag roughly from Zobb's mouth.

'Zekiel gaped.

"Thee axed vor private matters, holy father, zartain zure. Hast thee not got what thee wanted?"

The man in monk's habit held a pistol to Zobb's temple. "Verily, mariner, we will find what we seek. I know not whether thou be fool or knave. Yet understand this—raise but a whimper of warning, and it will be the signal for thy death."

"I know nought of private papers, holy father," protested Zobb, truthfully enough.

"If I thought thou wert wilfully deceiving me, fellow," responded Peke angrily, "this moment should see thy brains bespattering the baggage."

"Nay, worthy father, 'twere a shame to spoil yon shifts but now come clean from the washing woman," Zobb said solemnly and slowly. Then swiftly he roared out, "Help! Mur—"

For a moment it looked as if the furious Peke would have fired, but the men holding Zobb flung a cloth about their captive's head, effectually muffling his bellowing voice in its folds.

Zobb's cry of alarm, however, had awakened more than one in the inn; among those who looked forth from the attics was Ralph Coombe.

Roughly rousing his uncle, Ralph cried: "Zobb is in trouble, I fear! Follow fast after me. Highwaymen be at our baggage, mayhap."

And the youth, fully clad as he was, ready for an early start at daybreak, rushed down the stairs, raising the house with his shouts.

Already mine host was unfastening the bolts of the door.

Ralph was the first to hasten across the cobbles of the courtyard to the stables. As he did so he saw a cowled and robed figure spring swiftly to horse and go galloping forth into the night, followed by a string of riders.

It was found that nothing had been stolen, so no one was anxious to fare forth after the night-riders. Ezekiel Zobb was released, vowing vengeance, yet anxious to tidy up the barn, which looked as if used for its primitive purpose, with an influx of tithes littering the floor.

Roger Coombe, flinging a cloak about his shoulders, followed Ralph at some interval. Every one was crowding into the Tithes Barn to survey the confusion. For the moment the inn door was deserted.

Two of Peke's men, delegated for the purpose, took the opportunity offered. They too had been disguised as monks, like their master, and they had duly studied Roger Coombe's features for future occasion on the journey out from Bristol.

At the foot of the stairs Roger Coombe saw two men slip forth from out the stairway to the wine-cellar. Thinking naught of it, what was the adventurer's surprise to find himself pinioned and gagged before he could raise a shout for help!

By the dim light of a lantern the two myrmidons of Peke made a complete search of Roger Coombe's person. Like the rest of the travellers, as was customary under such conditions, the adventurer had slept in his travelling clothes.

"Give us the chart," whispered one of the men, "and thy life shall be spared."

Roger Coombe signalled the man to remove the gag.

While one held a pistol to his head, the other removed that which prevented Roger speaking.

"What chart dost thou seek?" asked Roger, conning the man with eyes sleepily hooded.

"That which Black Velvet gave thee," promptly replied his assailant.

"Prithee, good strangers, who serve me thus ruthlessly, the chart avails nought to any wight save myself," protested Roger Coombe, in guileless fashion. But his eyes bent to his pointed shoon.

The men, not unpractised in highway robbery, grabbed at Roger's right foot, and pulled off the tapering shoe with its upturned end. As they bent a smile passed swiftly over the merchant adventurer's face, to be replaced with a look of tragic indignation as they conned his countenance when they found within the upturned end of the shoe a securely folded parchment.

He was about to raise a shout when the first man flung his hand over Roger's mouth and promptly gagged him ere he could utter a sound.

The two men were in a ferment to be gone. They did not stay to examine their find, which they had not the slightest doubt was the chart their master desired. Twisting rope about wrists and ankles, securing the gag in his mouth, the two men flung Roger Coombe helpless among the wine-barrels.

Sauntering forth amid the hubbub, the two night-riders found their horses where they had tethered them in the orchard, and swung forth along the highway in triumph, congratulating themselves that they had accomplished that which Anthony Peke had set them to do.

It was Ralph who presently found that his uncle had disappeared; but even as he was gathering a party to pursue the mysterious raiders it was told him that some one lay bound in the wine-cellar.

Roger Coombe had kicked right lustily on the cellar door with his heels.

"What happened to thee, Uncle?" Ralph asked when presently they were alone.

Roger Coombe laughed heartily, then he said, "They made me captive."

"Prithee, Uncle, I see no joke in this dastardly attack on thy person."

"Nay, dear nephew, thou wouldst not unless thou didst know what really happened."

"Which was—"

"That my assailants sought a chart to a hidden city," Roger replied, with his eyes dancing with laughter, "and found—"

"What?" cried Ralph, as his uncle paused. "What?"

"An apothecary's charm for warts and corns, set forth in fair Latin!" exclaimed Roger Coombe, his features rippling with laughter.

THEY were lodged in a tavern nigh the Tower in London Town—Roger Coombe, his nephew Ralph, and 'Zekiel Zobb.

In the seclusion of their private chamber uncle and nephew sat chatting of their adventure at Newbury two days before.

"When the thieves who carried off thy cure for warts and corns, Uncle, find they have gotten no chart of a hidden city, verily they will make another murderous attack on thy person."

"Nay, Ralph," Roger declared, and his keen eyes roved round the apartment, "we are under the protection of the spies of the Star Chamber. Doubtless our assailants of Newbury, led by that cowled monk—who may or may not be as holy as he appeared—hasted to get their work done, knowing that once in London Town we should be safe in the shadow of Sir Black Velvet. They have made their attempt to secure that which is so much desired by those who are aware of its existence."

"You speak in riddles, Uncle. Do you refer to the chart of the hidden city?"

Roger Coombe swept a heavy book from the table, and the sound drowned Ralph's last remark.

"Hush! Even the walls have eyes," the wary adventurer whispered. And with a swift glance he indicated a portrait hanging in the darkest corner of the chamber.

Ralph stared at the corner—stifled an exclamation. He could have sworn the life-size portrait blinked!

Roger Coombe's lids drooped over his eyes as they were wont to do when their owner was particularly watchful.

"Have no fear, nephew. 'Tis to this inn our friend, Sir Black Velvet, did invite us, and so powerful a personage is he that I doubt if any other in this kingdom, save only his puissant Majesty, Henry the Eighth of that name, would dare molest us."

"But the portrait—I mean to say, Uncle, what of his lordship of the Black Velvet?"

The sudden change of query had been wrought by the click of Roger's finger and thumb. In days when danger had lurked on every hand the two Coombes had used the same sign to warn each other of lurking peril.

"Aha! Sir Black Velvet was a right wary visitor. He came on certain business, but he left me with a physician's prescription for warts and corns which I allowed those villains at Newbury to steal," went on Roger Coombe, his eyes almost hooded completely.

Ralph knew, however, by the glint of his uncle's eyes and the soft clicking finger and thumb that his uncle was playing a part, and that the portrait which blinked called the tune.

"I trust, Uncle, this chivalrous gentleman of the Black Velvet will permit me to join thee in the expedition which is afoot."

"That permission, Ralph, depends on thy discretion. Wilt come with me to the Spanish Main or through the North-east Passage? Nor question my leading? Nor be over-curious concerning that which I go to seek?"

"Thou hast tested my devotion in the past, Uncle Roger Coombe"—and Ralph spoke as much for the benefit of his uncle as for that portrait that blinked—"and thou knowest that we have ventured together in enterprises more hazardous than even Sir Black Velvet could provide for us."

There had been curious noises coming from the direction of the mysterious portrait in the shadows. A voice followed, a soft, silky voice, whose owner was clad—in black velvet!

"Perchance I can supply adventures enow to satiate thy peril- hungry spirit, young Coombe."

Ralph gave a swift glance at the portrait. The eyes no longer blinked; there were but pools of blackness where the eyes had been. Sir Black Velvet no longer spied; he had stepped into the room from out the space made by the sliding of a secret panel in the wainscot. Ralph rose to his feet, and bowed to the mysterious visitant.

"We have watched thy nephew closely, Roger Coombe," continued Black Velvet, turning to address the older man, "and he passes the tests."

"Oh, may the saints reward thee, sir!" cried the delighted youth. "I could not bear to be parted from my uncle, however hazardous the enterprise thou hast for us."

"Yet there is one final test," Sir Black Velvet declared. "He who sends you both on this great emprise would fain see you in the flesh ere he entrusts the priceless chart to your keeping. Likewise this same patron would see the sailorman, Zobb. And, having satisfied his august self that ye three are worthy of his trust, he will give into thy keeping, Roger Coombe, that chart which thou must guard with thy life. And shouldst thou perish, thy nephew here must guard it till there is accomplished that for which it is given thee."

"If there be naught in the project save what a true man may undertake, Sir Black Velvet, thou mayst rely on us to serve this unknown patron till we have accomplished our high enterprise. Thou hast so whetted our appetites, Sir Black Velvet, for the hazards ahead that we long to be away. When may we present ourselves to our august patron?" Roger was wide-eyed now.

"To-morrow, at three of the clock, I will bring horses and conduct thee, Roger Coombe, and thy nephew here, and that other man of strange name to be interviewed by one whom ye shall not see."

And Black Velvet, in his black velvet shoon, passed almost noiselessly to the door.

Roger bowed his head in acquiescence, while Ralph sprang to open the door for their visitor.

But the door swung open without Ralph's aid. An obsequious landlord and an armed soldier stood in the antechamber. They pressed to one side to let Black Velvet pass.

Ralph Coombe, though jubilant at the adventure ahead, was not sorry to see the back of the emissary of the Star Chamber. Black Velvet's cold, grey eyes seemed to pierce one's inmost thoughts.

"I'm right glad he's gone, Uncle," said Ralph, aware of the same sinister searching of those grey, cruel eyes.

Roger Coombe's finger and thumb clicked yet again, and he flung a warning glance at the portrait in the corner.

Eyes were still focused on uncle and nephew. But they were not cold, grey ones!

"Hahahaha!" came a chuckling laugh from out the wainscot. Whereupon watchful blue eyes disappeared from out the portrait to reappear in the room, after some fumbling and an expletive in broad Somerset.

"Zure and zartain, there be no cause vor vear," said 'Zekiel Zobb. "I bin looking after ye.... Black Velvet and one musketeer came into the tavern, and Black Velvet and one musketeer have gone away down street, whilst landlord went back to his bar."

And the Somerset sailorman went on to tell his story in the dialect he always used. The faithful fellow had kept close guard on his masters, and when Black Velvet arrived he had stalked him and seen him enter a secret door from the passage outside. Then when the man-at-arms and the landlord had passed to the antechamber he had secreted himself, and promptly taken Black Velvet's place when that mysterious individual vacated the space behind the picture.

"I pray thee, 'Zekiel, be not over-rash," begged Roger Coombe. "There is much more in this strange business than ever I can fathom. I know not the name of our ultimate employer, for it seems that Sir Black Velvet is but his agent. I only know that golden guineas are as plentiful as apples in Somerset orchards. As to the enemies who attacked us at Newbury, who they may be I cannot guess, though I know they strike athwart Black Velvet's plans."

"Ask Black Velvet hisself," advised 'Zekiel.

Roger Coombe said he would. But Black Velvet, when questioned on the following afternoon, gave little information. "'Tis Spanish work!" was all he would say. "Yet beware, Roger Coombe, of one named Anthony Peke."

Black Velvet had come to fetch the trio of adventurers to be inspected by their unnamed patron, and was attended by a gay cavalcade.

The party rode forth from the courtyard of the tavern, led by that black-garbed man on the handsome black horse which he always bestrode when abroad in the streets. He was the one sombre figure amid the posse of gay, liveried servants and armoured soldiers accompanying him. Horses were provided for the Coombes and Zobb, and each of the trio was attended by two lackeys, who rode close at their elbows.

"'Tis zartain zure," quoth 'Zekiel Zobb, "that Black Velvet don't mean to let us get lost, Ralph zonny."

The cavalcade clustered across London Bridge, and the fortified gates at the southern end were swiftly swung open at a mere gesture of Black Velvet's hand.

Thereafter the course of the river Thames was followed, save for certain short cuts where the river curved, till open country road was reached.

At a wayside inn a halt was called, and refreshment was promptly brought to the riders, whose advent, it seemed, was expected.

"Whither do we go, sir?" inquired Roger.

"To thy patron's garden," responded Black Velvet curtly. "Yet the way thither shall be hidden from thee and thy two companions' eyes."

With the words, and at a signal of his black-gauntleted hand, the leader of the cavalcade summoned servants, who proceeded to blindfold the three West Countrymen.

Roger Coombe uttered a protest.

"Such are my orders," said Black Velvet, in his silkiest tones. "It is only mine to obey. And, seeing how great an enterprise thou art embarked upon, Roger Coombe, it ill becomes thee to take offence in the small matter of a kerchief across thy eyes."

"Marry, 'tis not the kerchief I resent!" retorted Roger. "'Tis the want of trust."

"Fear not but what, when thou hast passed thy employer's scrutiny, thou shalt be trusted to the uttermost," Black Velvet responded, and he gave the order for the cavalcade to continue its journey.

For another hour the trio rode with hooded eyes. Ever and anon there came to their ears the sound of the river, and once Ralph felt sure, by the hollow sound produced by the horses' hooves, that a bridge had been crossed. Presently the soft pad-pad of horses' feet told the adventurers that they were riding across greensward—fields or, peradventure, a park.

Came the sound of trotting horses, a clattering of accoutrements, and a sudden halt.

"Pray descend from your steeds," came the command from Black Velvet, and outstretched hands helped the blindfolded men to their feet.

Zobb, unable to restrain his curiosity, put hands to his kerchief to unhood his eyes—only to have his hands seized from behind and tied up behind his back.

"No harm is intended, rash seaman," came the silken tones of Black Velvet. "Yet raise not the wrath of the mighty by any unseemliness, lest harm come to thy masters."

The argument effectually muzzled Zobb.

Thereupon each of the blindfolded ones felt himself led gently enough by two men-at-arms—to judge by clatter of accoutrements—across sward to firmer ground—it might be a drive or a garden path.

For some distance they were taken along this firmer ground, and then suddenly found themselves released. They heard the sound of retreating footsteps.

"It is permitted ye to unhood, but stir not one step from where ye stand," came the voice of Black Velvet, raised a key higher than usual.

All three were glad to lower their bandages forthwith. They blinked in the sunlight, and looked round them. There were none but their three selves to be seen, and thickset hedges on both sides of them.

Black Velvet's voice came from the other side of the left-hand hedge.

"Ye cannot come to me nor can I come to you. Yet from where each stands the business of the afternoon can be transacted. Hush, and doff your caps!"

There came sounds of footsteps treading heavily; it might be four or six soldiers bearing some burden. They halted at a word of command. A hoarse, querulous voice spoke haughtily in an undertone.

Then it seemed to Ralph there was a stir among the leaves of the evergreen hedge, and afterwards Ralph averred that he caught sight of a spy-glass focused upon them.

But the voice held them—that deep, querulous voice with cruelty in its tones.

"Are ye loyal subjects?" came the question.

"Yea," responded Roger Coombe to the unknown. "We love this realm of England, and for her sake we have ventured across tempestuous oceans to undiscovered lands on the edge of the world."

"Well zaid, Maizter Coombe," added Zobb, clapping his hands.

"Silence, knave," came the cruel, querulous voice. Even Zobb was awed by the unknown speaker.

"Roger Coombe, thou shalt be rich for life," went on the hoarse voice, "if thou dost but bring back to this spot that for which I send thee to far Cathay." There was a deep groan of anguish, as if the speaker were smitten with sudden pains, a volley of oaths, then: "Obey my servant with whom thou hast already conversed. Disobey him in but the smallest particular, and thou shalt rue it to thy dying day."

There were whispered words, then the tramp of men retiring with a burden.

"A litter," Ralph said in an undertone to his uncle.

Roger Coombe held up a warning finger, and there was a tense silence. But with the departure of the unknown came a sense of relief, as if an evil influence were removed. At no moment in the mysterious enterprise was Roger Coombe so inclined to withdraw from the stern toils that gathered about the three adventurers.

The silken voice of Black Velvet, however, came purring through the hedge.

"Thy fortune is made, Roger Coombe, and the fortunes of thy companions."

"Zure as me name is 'Zekiel Zobb, I be main glad to hear that," remarked the sailorman. "That chap with the rheum in his voice gave me shivers down me back."

"Fare thee well for the nonce," spake Black Velvet. "I will rejoin thee later, Roger Coombe, if ye three do not find me first."

"That gives us permission to move!" exclaimed Ralph. And forthwith he hasted along the narrow path betwixt the two hedges, that were too high to peer over and too thick to peer through.

But haste as the trio might, no other view than that of two evergreen hedges met their gaze. There came choice of turnings, but they only passed from one circular path to another similarly girt with trimmed hedges of uniform height.

'Zekiel Zobb had taken to running, but he presently stopped short when he found his companions were out of sight. Not without difficulty the three found one another.

"Get thee on my shoulders, Ralph," cried Zobb, "an' zee if we do live in a world of hedges!"

The youth hoisted himself on the mariner's shoulders.

"Verily it is nought but hedge-tops that I see. We must be in a maze."

"Amazed have 'Zekiel Zobb been this last hour an' more," growled the sturdy sailorman. "Tell us summat vresh, Ralph Coombe."

"Beyond the hedge-tops there is a park of many trees," the youth continued, swaying ominously on Zobb's shoulders.

"And beyond the park is there not a palace?" eagerly questioned Roger Coombe.

"Not one that I can see," responded Ralph, and came toppling to earth.

On in the puzzle-garden the trio wandered, yet found no exit; indeed, half an hour later they found themselves where they had started.

"Zure 'tiz walking round ourselves we be," Zobb said. "I zwear this be the spot where Black Velvet spoke."

"In two minutes I will be wi' ye," came the silken tones of him whom they sought. And, as he had promised, so it came to pass. Black Velvet stood before them, smiling.

"My master," said he, "is satisfied that ye will penetrate to the hidden city of Lamayoorah, to bring back the treasure he covets. He desires me to hand thee this chart, Roger Coombe, and he commands ye all three to defend it to your last breath. Now ye must return to your tavern in such fashion as ye came."

BLINDFOLDED, as on the outward journey, the trio returned to London with their escort and Black Velvet. As they neared the confines of the city their eyes were unhooded.

"Verily I have learned little from my darkened journey, Sir Black Velvet," Roger Coombe said, as he scanned the unnamed man in whose hands were their destinies, watching him intently.

A ghost of a smile flickered over the pale features of Black Velvet.

"'Twas little thou wert expected to learn," he responded. "It was, rather, that thy patron desired to read thee and thy two companions. The Maze was grown by those who wished to see rather than to be seen. His—lordship is satisfied that thou art a true man; of thy prowess and that of thy young nephew Ralph, and of thy mariner servant, he was already assured. Indeed, so set is he on the project, so impatient to handle that which thou art sent forth to seek, that already at Blackwall a tall ship even now rides at anchor, waiting to fare forth to the far-distant city of the Grand Turk. Which ship is replete with all stores for thy voyage and for the overland journey which must follow thine arrival in Constantinople. The chart of that land journey thou earnest in thy bosom."

The two men rode ahead of the rest of the cavalcade. None could overhear their words.

Roger responded. "Thou didst tell me, Sir Black Velvet, that Spaniards, or a certain Anthony Peke, were my assailants at Newbury. When they discover how they have been duped it may be they will make further attempts. Who is this Anthony Peke?"

"The Star Chamber has thee under her care Roger Coombe," responded the man who would answer to no name save that of Black Velvet. He went on, ignoring the question that had been asked:

"Thy swift departure on to-morrow morning's tide will circumvent those who may watch for thy going. They will not anticipate thy sailing so soon, and, of a truth, thou wilt be well-nigh returned with the Golden Globe before ever the others get on thy tracks."

It was the first mention Black Velvet had made of a tangible object for the perilous venture into far Cathay.

"Which Golden Globe is to be found in the city of Lamayoorah?" queried Roger quickly. "And it contains—"

But Black Velvet was not to be caught napping.

"That which it is thy high honour to bring back with thee. That which is within is worth more than the Golden Globe itself. That which is within!"

"Yet if I know not what that which is within may be," argued Roger, "how do I know that my mission is successful? If I return with an empty globe of gold my patron may dub me mere fool."

"If thou dost return with the Globe of Gold," answered Black Velvet, "that which is within will be within."

"Thy words are like thyself—an enigma," retorted Roger.

"Hist!" said the man in black. "Here come the others at our heels."

Roger Coombe could learn no more for the moment, but that eve, in the seclusion of the tavern chamber, Black Velvet gave further directions.

Looking up under drooping lids, Roger saw shining eyes in the watchful portrait on the wall, and Black Velvet whispered his words.

"Surely no one can overhear us twain talking through the thickness of the walls about us," Roger remarked slyly.

"Walls have ears," Black Velvet responded.

"And sometimes eyes," said Roger softly.

Black Velvet looked up swiftly, but Roger was gaping, gazing at the door of the chamber.

"The keyhole is secure from prying eyes," Black Velvet said.

"Ah!" replied Roger, as if satisfied. "Thy sentry is without."

Black Velvet leaned forward, speaking low.

"Reaching the city of Constantinople, thou wilt go to the house of the English factor, Dick Darsall, who dwells in Pera nigh the fish market. Give him this symbol—a metal talisman in the shape of a star—and Darsall will supply all thy wants without one word of payment.... Remember, Roger Coombe, thy patron is very powerful."

"As powerful as—the King!" snapped out Roger, as he put the emblem of the Star Chamber within his bosom. "As powerful as King Henry!" he repeated.

But Black Velvet did not answer, only smiled faintly, whilst his grey eyes raked Roger through and through.

"I hid thee good-night and restful slumber, honest adventurer," said the man in black as he passed to the door, which opened before him.

After taking his evening meal in the common-room of the tavern, Roger retired to the bedroom for the night, Ralph using the same room as his uncle, for safety's sake.

Zobb would spend the night in no other place than the stable, where were the sumpter-mules and bales of belongings wanted on the voyage—and after. "Thic time 'Zekiel Zobb won't be caught napping like he wur at Newbury," declared that worthy. "Ef I do sleep 't'll be wi' open eyes an' ears."

The night was cold, and a lackey—a long-nosed, long- shanked fellow with shifty eyes—tapped at the bedroom door and asked whether the Coombes would require charcoal to take the chill off the night air.

"Tell our worthy landlord 'tis a kindly attention of which we will gladly take advantage," Roger replied.

The long-nosed lackey quickly returned with a pan of glowing charcoal, and placed it on the hearth, promptly retiring with no other word.

"Why couldn't the wood already on the hearth be lit?" Ralph asked. Somehow he liked not that serving-man of sly looks.

But his uncle was already abed, and sleepily murmured, "Don't forget thy prayers, nephew."

Soon both were asleep on the straw pallet beneath which Roger had hidden the precious chart handed him in such strange circumstances that afternoon.

Ralph woke gasping—to feel hands at his throat—his own hands! He was struggling for breath.

Roger Coombe lay snoring in stertorous fashion, his eyes open, staring with no sign of consciousness in them.

Ralph tried to rise, but his limbs refused to respond to his will. And then, lying there helpless, not sure that he wasn't dreaming, he saw a long-nosed lackey peer into the bedroom from the slowly opening door.

Ralph had himself locked the bedroom door, and the key lay beneath his head under the pillow.

The lackey must have a duplicate key! But what was the fellow doing in the chamber at that time of night? Did he fear the charcoal might fire his master's inn? Ralph watched through a fringe of eyelashes.

The drugged youth wanted to shout—wanted to ask the lackey why he held a dripping cloth before his lantern jaws.

What a curious nightmare! How would it end? For lo! another figure came creeping into the bedroom—that of a soldier.

Then the soldier suddenly sneezed. And Ralph knew it was no dream!

The lackey, who was stealthily approaching the bed on which the Coombes lay, sprang round.

But muscular arms gripped him. There was a fierce struggle. Both went crashing to the floor.

A second man entered the apartment, gasped, and sneezed!

"Take that charcoal-pan from out the room, Will!" cried the muscular soldier, sitting astride the long-nosed lackey. "'Tis stored with some devilish drug that suffocates."

The newcomer addressed as Will, coughing and gasping, ran from out the room, bearing the pan the supposed lackey had placed there a short hour before.

The lackey lay felled on the floor, motionless.

The soldier of the Star Chamber rose, and, rushing to the casements, flung them open to admit fresh air.

"Nigh poisoned thee, lad," he said, as Ralph blinked and struggled to a sitting posture.

Ralph shook his uncle violently, and soon saw reason light the vacant eyes. The two Coombes, breathing deeply, took fresh air into their drugged lungs, replacing the fumes inhaled from the pan introduced by the man who had pretended to be a lackey of the tavern.

"What does it all mean?" Roger Coombe inquired, holding his throbbing head between his hands.

"It means that there be those who seek something that is hidden in this room, O worthy adventurer," responded the soldier who had saved them from suffocation. "Will yonder was set to watch thy door, but, an' I mistake not, his possett was drugged, and he slept on the bar settle instead of on the threshold of this room. It was well that more than one of the servants of the Star Chamber was set to watch over thy welfare. Disturb not thyself, good sir. A dozen men and more are buzzing round like so many bees, and intruders are like to get stung. We will remove this carrion from the floor, and purge thy chamber from all fumes."

"But what of my servant Zobb?" gasped Roger.

"A special guard of three soldiers watch over his safety."

"But they too may have been drugged!" Ralph cried.

"Nay," said the soldier. "I was one of them, and only now have I come from the merry mariner to see how Will was faring. 'Twas among the baggage we expected thieves, if anywhere. Thy foes be desperate, good sir, if they dare to brave the enmity of the Star Chamber."

Two more retainers entered the bedroom, and bore forth the unconscious lackey.

And when the Coombes bade farewell to mine host of the tavern on the morrow he pointed to Tower Hill, and there they saw that same lackey prisoned in the stocks. Each side of the long nose there was branded the letter 'F,' publishing to all the world that the man was a thief.

Black Velvet rode at Roger's side.

"I trow thou wouldst have been dead ere this had that villain got his way," said the man of the Star Chamber. "We met in the Star Chamber in the early hours, and nigh had decided to string up yon carrion to dance on empty air, but we knew right well he was but a helpless tool. It may be necessary to teach his master a lesson."

"Anthony Peke?"

"The same," responded Black Velvet. "But he walks in high places, and still enjoys some favour in King Henry's sight, seeing he played traitor to his former benefactress Catherine of Aragon, who once was Queen." The man in black was whispering in Roger's ear. "Peke has been our English spy in Spain, and is high in favour with the Emperor Charles. Harm done to Anthony Peke might be regarded as an affront to Spain, the which King Henry would fain avoid. Yet"—the cold, grey eyes stared, suggesting more than speech—"were Anthony Peke a nuisance to thee I know the Star Chamber would not inquire into the matter of a mere dagger having let out his blood."

"I'm not to be hired, as private assassin!" cried Roger Coombe indignantly.

"Nay, I did not ask it," purred Black Velvet, in his silkiest tones. "Yet, friend Roger, thou mayst find Anthony Peke less scrupulous, for, I have reason to know, that the Emperor Charles would give half his huge fortune to possess the Golden Globe—to grasp that which is within."

"'TIS right good to be afloat again," said Merchant Adventurer Roger Coombe, stretching aloft his arms to a sunlit sky.

"Aye, Uncle, and to be bound withal for the city of the Grand Turk," added Ralph, rubbing hands together in his glee.

"An' zure as me name is 'Zekiel Zobb, I be main glad to be out o' zound o' Black Velvet's purr," added their handy-man. "He wur too much of a cat wur thiccy man, an' made me feel no better than a mouse. But the cat's away, zo now we ull play, my maizters."

And the irrepressible mariner danced a hornpipe on the deck.

The trio of adventurers were aboard the tall ship Susan, fourteen days out from Blackwall. Contrary winds caused delay at Cowes, in the Isle of Wight, but, hugging the coast, they came at length to Plymouth, whence prosperous winds sent the Susan spanking southward, so that within three days they had sighted Cape Finisterre.

"With the wind at our backs," Roger declared, "we should touch at Cadiz within the week. 'Tis there our excellent shipmaster, Jeremy Tunder, may call for fresh water and supplies, though it may be he will elect to make all speed to the capital of the Grand Turk, staying the voyage only if there is dire need. Indeed, Tunder has orders to do my will rather than his own."

"'Tis as though we went on King's business," Ralph remarked jocularly.

Roger leaned forward, his face set in solemn lines.

"I am not so sure, nephew, but that it is the King's business on which we are embarked."

"Why d'you think it, Uncle?" asked a startled Ralph.

"'Twas the Maze at Hampton Court whither we were taken, or I'm a Hollander!"

"And who is Black Velvet?"

"Merely the servant of the Star Chamber and the King behind the Star Chamber. But hist! Here comes our good captain."

"Worshipful Master Roger," said Tunder, a cadaverous man with twinkling blue eyes, "if it be thy will we will not stay our voyage till we come to Mallorca. Our water will last if ye all grow no thirstier than at present."

"Mallorca be it!" said Roger Coombe, who was eager to test the chart reposing in the pocket-belt about his body.

Therefore it was that, passing Capo di Sant Vicente and Capo Santa Maria, the Susan was soon athwart Gibraltar, and, within another five days had anchored in the harbour of Port Sant Pedro, on the island of Mallorca.

Much friendliness was shown by the islanders to the ship's company, and casks of fresh water could be had for the fetching, said the Spaniards.

"Strange that they should not seek to make gain by the sale of the casks, as is their wont," remarked Roger.

"They are most polite—these Spanish officers," Ralph responded, as he spied through a porthole. "Already some of our seamen are ashore with the empty water-casks."

"'Tis not the going ashore that matters," Roger Coombe said grimly. "'Tis the getting back aboard that may be difficult."

"But England is at peace with Spain, Uncle?"

"Yea, but Spain is a treacherous ally," Roger replied, "and Charles covets the English islands for himself or his son Philip. Mark my word, Ralph, thou wilt yet live to see an armada fitted out to conquer our England.... No, Ralph, neither thou nor I will go ashore, however polite the Mallorcans may be."

"Come to the porthole, Uncle!" cried Ralph. "Look! A gay cavalcade advanceth to this very vessel. What think you they want with Captain Tunder?"

Roger, looking forth, saw a horseman approaching, gaily bedight, and at his heels a second cavalier in resplendent armour astride a white horse.

"'Tis the Viceroy's own self come to honour us, worshipful Roger Coombe!" bellowed Jeremy Tunder through the hatchway.

"Thou canst invite him aboard," Roger said, "but say no word, shipmaster, of my presence here."

The Spanish representative was prompt in mounting to the Susan's deck; indeed, insisted on his right to do so. He was a mean-featured little man, as his raised visor revealed. His armour was several sizes too big for him.

"He do rattle like a pea in a pod," declared Zobb in Ralph's ear, as the ship's company mustered to meet the Viceroy.

The little, ratlike eyes roved over the company and fell on Ralph.

"Ze cavalier Coombe, is it not?" queried the Viceroy.

Ralph sprang to attention—stared in amazement. His uncle had allowed him to come on deck, thinking he would be taken for one of the ship's apprentices. What should a viceroy of a Spanish island know of Ralph Coombe? Who had told the Spaniard that the Susan bore a passenger named Coombe?

Ralph bowed.

"What might so gallant a cavalier require of a poor English voyager?" he asked.

The Viceroy knew only a few words of English; he turned to the second cavalier, who was still in close attendance.

A second time Ralph was startled. The cavalier at the Viceroy's elbow had raised his visor, to reveal a face dominated by fierce, black eyes. Surely Ralph had seen those cruel eyes under a cowl on the road out of Bristol! And the figure? Yes, the cavalier was of the same height and bearing as that monk who had escaped from the inn at Newbury after the attack on Zobb!

The two cavaliers whispered together.

When the Viceroy turned again to Ralph, he spoke sharply in Spanish, and, turning to his companion, "Translate, Sir Anthony," he concluded.

Whereupon the second cavalier interpreted the words spoken in Spanish, not knowing that the Coombes understood that language. "His highness," said he, "desires to speak with the uncle, not with the boy nephew."

And then Ralph knew he must be in the presence of Anthony Peke, and no other! He was too surprised to speak.

It was 'Zekiel Zobb who came to the rescue. With a most woebegone face, the tubby mariner stepped out from the ranks of the seamen, wiping imaginary tears from sad eyes.

"My maizter is not yet dead," he wailed. "Yet, zure an' zartain, he ull be a dead un if ye worrit him."

Whereupon a wondering Ralph flew to the cabin below decks—to be greeted with a prodigious wink of his uncle's eye.

Roger Coombe and Ezekiel Zobb had done much in little time.

The merchant adventurer lay back in his bunk with a face whiter than the sheet drawn close about his bared neck—a little chalk goes a long way—a mouth drawn down at the corners (Roger was a consummate actor), and a feeble hand hanging limp over the side of the berth.

"Uncle, your enemy has come aboard," Ralph hissed. "The monk of the Bristol road, an' I mistake not. Perhaps Anthony Peke's own self!"

"Zobb recognized his assailant of the Newbury inn," Roger responded rapidly. "Wherefore our preparations. Return on deck, say I am too ill to be seen, and remember I have plague."

Anthony Peke, confident that the Coombes would never recognize in the interpreter of the Viceroy the monk of the Bristol road, declared that the Spanish representative of the island desired to pay his devoirs to so notable a voyager as Roger Coombe, and could not be content with seeing the boy Coombe.

Shipmaster Jeremy Tunder, to whom the words were addressed, bowed gravely. The captain knew there was more in the Susan's mission than he understood, and so remained silent, awaiting Ralph's return.

"My uncle is indisposed—to see visitors," Ralph explained.

"'Tiz my belief that Maizter Roger be zick of the plague," said Zobb, in a loud aside to a shipmate. But his remark was overheard by Anthony Peke, as 'Zekiel meant it to be.

Anthony Peke shivered.

"The Viceroy will send his barber-surgeon to see the invalid," he said, after a whispered consultation with the little Spaniard. "And if Roger Coombe can be moved he shall be taken ashore—to recover his health."

But that was the last thing that Ralph desired!

"We thank the Viceroy for his kind thought, and—and we will expect the good surgeon on the morrow."

"Nay, the case brooks no delay," Anthony Peke replied. "The surgeon comes within the hour."

"We must up-anchor and sail within the hour," Ralph declared, as the visitors went ashore, to gallop forthwith toward the town, which lay at some distance from the port. "Look, Master Tunder, there be men on horseback and on foot gathering in the woods overlooking the harbour, and if I mistake not they are dragging four or five brass pieces to the point overlooking the harbour entrance. The Mallorcans mean mischief, Master Tunder."

"Yet first must I get my men aboard," Tunder declared. "We will see how the plague-smitten one progresses."

But a lively Roger himself stepped up to the shipmaster ere he could descend to the cabin below.

"How soon may we sail, Master Tunder?" the merchant adventurer asked.

"When I get my men aboard, worshipful sir, begging your leave," the captain of the Susan said.

But though the trumpeter blew the blast of recall, the sailors failed to return to their ship. They had been lured into the city, and Majorca, the capital of the island, was three miles distant from the port.

Roger looked at Ralph. Ralph watched his uncle intently. Both knew the peril of their position, with those guns getting into position at the harbour mouth. Both knew the strength and ruthlessness of their enemies the Spaniards and that renegade Englishman Anthony Peke.

"We cannot leave our countrymen to the mercies of the rascally Mallorcans," Roger Coombe finally declared. "But we will prepare to tackle whatever betide."

As Anthony Peke had promised, a barber-surgeon, accompanied by a couple of fully-armed guards, came galloping back to the quay within the hour.

The barber-surgeon demanded to come aboard. While he was parleying with the captain Ralph looked out from the cabin where the supposed plague patient lay, and invited the two Mallorcan soldiers to look through the porthole.

One spoke to the other in Spanish after he had seen the apparently dying Roger.

"Marry! But 'twere better to let the heretic die where he lies than bring him ashore to infect good Catholics."

And the two guards sheered off from the ship's side.

The Susan lay but a few feet from the shore, and it was necessary to fling a gangway board to bridge the gap between ship and quay.

It was 'Zekiel Zobb who was deputed to attend to the insistent surgeon's shipment.

The deck of the Susan was some feet higher than the quay. The pompous surgeon ordered the first man-at-arms to precede him aboard.

The man obeyed reluctantly; he was mightily afeared of plague. He waited with drawn sword at the head of the gangway board, a primitive affair, with no handholds—in fact, little better than a mere plank.

The barber-surgeon, weighty in both body and mien, stepped haughtily on to the gangway to pace upward with much majesty and deliberation; not often did a heretic ship have the honour of receiving so distinguished a surgeon, he said to himself.

But as he said it there was a sudden commotion.

Zobb appeared to slip—fell heavily against the man-at- arms—deftly knocked the drawn sword into the water below, at the same time pushing the gangway sideways, so that it failed to bridge the gap between ship and shore.

The soldier fell to the deck, the surgeon fell to the water, while a hypocritical Zobb howled contrition for his clumsiness.

Jeremy Tunder, who was in the conspiracy, declared the seaman should be shot, drowned, and imprisoned for the rest of his clumsy life. Then, looking over the bulwarks, he shouted fulsome apologies to the purple face that looked furiously upward from out the bilge of the port.

It was Ralph who flung a rope to the drowning man, and Ralph who helped drag the dripping surgeon, bump! bump!! bump!!! up the slimy side of the ship.

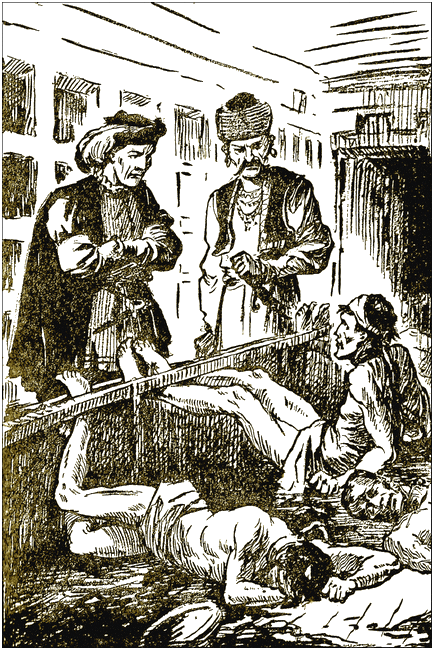

It was Ralph who helped drag the dripping

surgeon up the slimy side of the ship.

The surgeon was beside himself with fury, and was only pacified at the sight of 'Zekiel Zobb in irons. He refused to see the patient, though Ralph implored him to do so.

Covered with filth, and full of water and strange oaths, the barber-surgeon remounted his horse, and did not report his failure to see the plague-smitten man till it was too late for Peke to act.

But the Englishmen's difficulties were by no means over, for Roger Coombe insisted that the ship should not sail till all the sailors came safely aboard again.

And Anthony Peke held the four men as hostages—to be released in exchange for a chart which he knew to be in the possession of Roger Coombe.

"ZURE, me zonny, 'tiz old 'Zekiel az ull vind a way out o' thiccy quandary," declared the sturdy little mariner out of Watchet as he and Ralph sat in the shadow of the huge figurehead, a buxom, blue-eyed 'Susan,' looking seaward.

Ralph was low in spirit. This Anthony Peke seemed gifted with superhuman powers; he knew all that was afoot. How had he learned of the Coombes' swift departure? How had he contrived to outsail them? The man must have a spy among the very inner circle of the Star Chamber itself. Peke knew everything and everybody, mightily influential withal, the friend of emperors. Who were the Coombes to fight him? And how were they to get away with the coveted chart if Uncle Roger refused to sail without the missing mariners?

"Marry come up!" Ralph sighed as he scanned the preparations at the harbour mouth to prevent the Susan's escape and the line of watch-fires along the quay, where sentries paced. "I can't see how we can escape the machinations of Anthony Peke."

"Zwim!" was Zobb's solution of the problem. Whereupon the little sailor started to strip himself.

There came a hum of voices from the captain's cabin. Jeremy and Roger were deep in consultation. The sailor on watch with Zobb was more asleep than awake; he left the job to Zobb.

Ralph looked longingly at the enterprising mariner. What were his plans? ... 'Zekiel and he had faced many perils together in the past.... It was a hot night, and a swim would be mighty refreshing.... It would be a solution of the problem if the four missing mariners could be got aboard again.... But his uncle would aver that they swam to catch wild geese.... Yet if the men were only on board the Susan could sail on the instant, and chance the Mallorcans at the harbour mouth being unprepared.

Ralph found himself unloosening his doublet.

Zobb was already sliding down a rope hanging over the side of the ship farther from the quay.

Ralph followed, wearing only his trunk-hose.

As noiselessly as otters, the two Englishmen slipped through the water, keeping in the shadow of the fishing craft that dotted the harbour. They ran the gauntlet of the watch-fires on the quay without being detected by the sentries.

They were no longer hidden by the boats riding at anchor. But the night was dark, and they had reached an area where no lights shone.

Zobb touched Ralph's shoulder, then pointed to a wooded spit of land.

Within two minutes they were ashore amid the trees.

"West Countrymen twain are the equal of half a hundred Dons, zonny," whispered Zobb as he led the way along a scarcely-to-be- discerned path through the wood.

There was no moon in the sky, and the rash rescuers reckoned the absent moon their best ally. But for an old sailor in his shift and a youth in his trunk-hose, both of them weaponless, to attempt the rescue of four comrades lodged in the gaol of Majorca Town was so mad an escapade that even reckless Roger Coombe could never have fathered it.

But chances are wont to come to men daring enough to seize them.

Zobb held up a warning finger—right under Ralph's nose. It was fearsomely dark under the dense, stunted trees.

Ralph listened keenly.

Voices! The sound of a tinder-box being scratched. A flicker of light, and the Englishmen saw two shaggy figures in a clearing bending over dry leaves, twigs, and heaped wood, which they were trying to kindle.

"Charcoal-burners?" Ralph hazarded.

Zobb frowned, and nodded his head. It was no time for speech, lest the peasants be startled into fight. With a finger he indicated himself, then pointed to the peasant to the left. Then, tapping Ralph, he singled out the figure to the right.

Two startled charcoal-burners had a sudden vision of 'two naked corpses in their shrouds'—as they afterwards described their assailants—leaping through the air to alight on their scared selves.

The ghosts, however, were sufficiently solid to bowl the Mallorcans completely over—bodily and mentally.

The prone peasants could not shriek, on account of the hands that covered their mouths—hands that were cautiously removed to be replaced by strips of torn shift. Zobb's attire grew yet more light.

Soon, however, both Englishmen were better clothed—as charcoal-burners!

The two unfortunate peasants were left bound in the adjoining rude hut which was their home, Zobb assuring them that he would return their clothes in due course. Also he informed them that if they dared to raise an alarm they might consider themselves as bad as dead—that was how he expressed it in broad dialect.

The Mallorcans could not understand a word of the little seaman's parting speech, but his grotesque antics almost scared them out of their few remaining senses, and they lay cowering under the grass mats Ralph flung over them.

So it came to pass that two seeming Mallorcan charcoal-burners came to the gates of Majorca Town at an hour when all respectable watchmen of a law-abiding city are dozing in their boxes.

Sleepily the warders at the gate allowed Ralph and Zobb to pass. The military authorities, under the instigation of Anthony Peke, had placed a triple number of guards at the port, but made no provision whatever for any attempt on the town itself.

Screened by the eaves of the low houses and the out-jutting upper stories, the two 'charcoal-burners' made their way to the centre of the city. Such wayfarers as were afoot at that hour of the night were themselves anxious to escape observation.

Only once were the supposed peasants challenged by a night- watchman.

Whereupon that rascal Zobb lurched shamefully in his walk, and made as if to embrace the indignant official.

"Peste! Thou drunken villager, get out of my way!" cried the watchman in Spanish. "I would verily clap ye both in gaol, but 'tis more than full with four English sailors, who take up as much room and make as much noise as forty Mallorcans. Get ye gone, and thank the saints ye are Mallorcans."

"Mallorcans indeed!" Ralph chuckled as the watchman fled.

And then they listened for the chanting sailors. They were within a short distance of the square, and soon they heard the sounds of revelry—vocal English merriment.

The prisoners were awake. And so was the weary gaoler! Try as he would, he could not sleep for the hideous row the heretics made. Seated outside the gaol, with his fingers to his ears, and his eyes closed, he did not note the approach of the two Englishmen.

The gaol—a circular stone building at the back of the market—was overlooked by no dwelling-house. If a second Mallorcan had been in sight of the prison that night he might have seen two charcoal-burners suddenly fling themselves on a nodding gaoler. But he would have heard little!

The fat little gaoler was deftly silenced with a dexterous blow of Zobb's mighty fist. There were occasions, the mariner said afterwards, when one could not observe the rules of the boxing art.

The Mallorcan gaoler gave one gasp at the impact of Zobb's punch below the belt, then subsided, while the seaman made certain arrangements of the gaoler's person.

Gaping in bewilderment, and more in consequence of the big round pebble with which he was gagged, the bewildered gaoler gave up his key.

Zobb handed it to Ralph, and Ralph promptly fitted it into the lock of the tollbooth.

The heavily nailed door of the prison swung open.

"'Tis 'Zekiel Zobb, iss sure!" exclaimed a Devonshire shipmate of the little Somerset sailor. "How be goin' to get us out, me dear?"

"Through the doorway, zaime way az I be bringin' thic gaoler in, forsooth!" responded Zobb, who was struggling to bring the Mallorcan to change places with his prisoners.

Ralph had run to unhitch the lantern hanging above the gaol door, to light the dark interior.

Zobb had not forgotten to bring a knife from the charcoal- burners' hut. Soon the cords about the Englishmen's legs were severed, and they could stretch their nether limbs.

The captives' wrists, however, 'Zekiel did not attempt to release.

"Zobb, me dear, are yeou not going to finish the job of freeing us?" the Devonian asked.

"Trust yer Uncle Zobb, comrade," snapped the tubby little seaman, busy with the tubby little Mallorcan. "Ye are goin' to change gaolers, ye sailor-men. Ralph, tie 'em all vour to yon chain."

Ralph gave a chuckle of delight; he guessed at Zobb's plan of escape. The little seaman was making yet another change of costume—from charcoal-burner to that of gaoler. Ralph realized with a grin of delight that Zobb and the gaoler were much of the same build.

Chuckling, the four sailors allowed Ralph to string them up to the rusty chain hanging from its staple—which came away with one wrench of the English boy's fist.

Zobb suddenly uttered a hiss of warning.

Steps approached. There was the clank of spurs!

"Douse the lantern," whispered Zobb, now completely disguised as a gaoler.

The interior of the gaol was left quite dark. The resourceful little mariner strolled confidently to the doorway, saluting as the officer strode up, and taking care his lifted hand should shroud his features.

"What are you doing inside the gaol, sirrah?" the young officer demanded in Spanish. "Your post is outside."

Zobb understood never a word, but beckoned mysteriously, and hastily withdrew into the darkness within.

Now, Alvarez was but a young officer lately arrived from Spain, and suspected no trap. He followed the beckoning finger—and felt a mighty fist!

"The Zaints be vavourin' us," said Zobb, as the young officer fell senseless. "Get thee into his uniform, Ralph, an' our game's az aizy az playin' knucklebones. Lizzen, all of ye. We be two Dons takin' ye back aboard the zhip by order of the Viz'roy. Ralph, haste thee to don the Don's gay colours."

The English youth soon transformed himself into a Spanish gallant, the helmet covering the upper part of the face, but not the lower. The young Alvarez wore a pointed beard; still, that was a small detail, and having gagged and bound the stripped officer, who showed signs of regaining consciousness, a prompt departure was ordered by gaoler Zobb.

The little procession set out as quietly and unostentatiously as was possible, choosing the byways and back lanes of the city.

Ralph, in the Spanish officer's uniform, led, his drawn sword held as its real owner had held it but five minutes before. Four abject-looking English seamen followed, securely chained, to judge by appearances. Bringing up the rear came the tubby little town gaoler. At least, that was how the procession presented itself to the three or four night-birds who sighted it.

Presently the party came to the main highroad to the port, and it was well that Zobb insisted they should turn aside to return the loaned costumes and the knife to the poor charcoal-burners. For no sooner were the Englishmen out of sight among the trees than there came trotting up from the port the military officer in command, and he would assuredly have asked why 'Alvarez' had dared to move the English captives without his orders.

The charcoal-burners, still cowering under their mats, and having no change of clothes to resort to, shivered afresh as there came to their ears the sound of clanking chains, and their hearts leapt in their bosoms as there came the thud of something being flung against their hut door. When morning came they were glad to find it was no dead body, but their own clothes, which the 'ghosts' had returned. They were overjoyed, and decided to say nothing of the black doings that were enacted before their very eyes on that night of mystery in Mallorca Isle, seeing that the 'ghosts' had been good to them.

At the port a mystified non-commissioned officer stared at the approach of the English captives. However, he was not prepared to dispute the doings of his superior officer, for had not the Seńor Capitano even now gone up to the town, and would he not have ordered Alvarez to return with the prisoners to the gaol if all was not well? It was strange policy to imprison the men in their own ship; orders had been so urgent for their capture and imprisonment in the town gaol. Yet with Alvarez in command, and fat old Stephano bringing up the rear, who was he to interfere? Certainly the early morning light was confusing to the senses. Alvarez's pointed beard was invisible, and Stephano's beard was red rather than its customary black.

Aboard the Susan were a woeful Roger Coombe and a doubly anxious Shipmaster Jeremy Tunder. The absence of yet two more of the ship's company had been noted when changing the watch.

"Ye can trust that old demon 'Zekiel Zobb to wriggle out of most difficulties," Roger asserted, trying to console himself and Tunder. "I only hope that daredevil nephew of mine won't dare too much."