RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

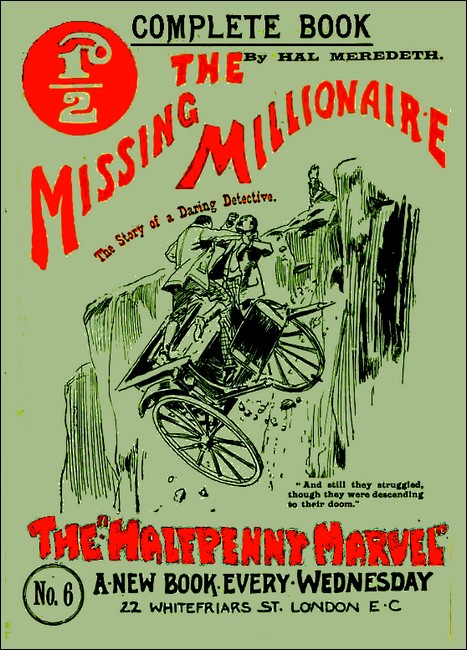

The Halfpenny Marvel, 13 December 1893 with "The Missing Millionaire"

The Detective and His Visitor—A Strange Story of Treachery—The Missing Millionaire.

"MR. FRANK ELLABY wishes to see you, sir."

"Good!" answered Mr. Sexton Blake. "Let him come up, and at once."

The clerk withdrew, and his master gazed thoughtfully at the grimy window of his office in New Inn Chambers.

"So," he muttered, "my wealthy client has come at last, thanks to the influence of my friend Gervaise, of Paris. I wonder what kind of mission it is he has in hand that is to bring me in such high rewards? Gervaise says it may keep me busy for a year or two."

Sexton Blake belonged to the new order of detectives. He possessed a highly-cultivated mind which helped to support his active courage. His refined, clean-shaven face readily lent itself to any disguise, and his mobile features assisted to clinch any facial illusion he desired to produce.

The door again opened, and a tall, handsome man, whose cheeks were bronzed by travel, and whose grey eyes were large and prominent, entered.

"Mr. Blake, I believe?" he said, as he paused on the threshold.

"Very much at your service, Mr. Frank Ellaby. Pray take a seat, and let me hear what I can do for you. Mr. Gervaise prepared me for a visit from you. But I am quite in the dark as to the nature of the business you desire me to undertake."

"It will prove more troublesome than dangerous," said the visitor, with a slight smile. "I will tell you my story, and then you will understand exactly what I want.

"My sister and myself were left orphans before we had finished our schooling. Some friends sent her out to Australia, where I believe she obtained a comfortable situation. It is unnecessary for me to bore you with a description of my struggles for existence. When I was about twenty I, like thousands of other men, old and young, took a sever attack of gold fever. I was determined to get to the Antipodes by hook or by crook, and try my luck at the diggings. If I came across my sister, well and good, although I did not start with any design of finding her. I had one object in view, and one only—that was wealth!

"I have obtained my desire," he added, with a heavy sigh, "But my heart is empty, and my life desolate!

"Out in Australia I met a man and his wife, with whom I became so friendly that he and I became partners in a claim, at which we toiled for months without finding one grain of gold. He was some years older than myself, and he went by the name of Calder Dulk. I don't suppose it was his real title, for I know now that there was nothing true about him.

"In those days I would have trusted him with my life. He, again, was younger than his wife, who was a tall, majestic woman, of French extraction wonderfully accomplished, fiercely ambitious, and altogether unscrupulous.

"I always mistrusted her, and, unfortunately, I had not the art to conceal my dislike.

"Just when we were despairing of ever having any luck, and were thinking of seeking our fortune in some other part, we struck a rich vein of the precious ore, and found ourselves wealthy.

"Like many before us, this sudden success turned our heads. Nothing would do but we must hasten to Melbourne and enjoy ourselves.

"A few days after we arrived there I accidentally found the house where my sister lived. I got there just in time to bid her good-bye for ever. She was dying. A beautiful, golden-haired girl of perhaps four years of age was playing in the room.

"'Frank,' gasped my sister, 'I swore to the mother of little Rose there, when she lay on her deathbed, that I would protect her child until she came of age. Take the same oath to me, Frank, so that I may die in peace.'

"There was, of course, no refusing this request at that awful moment, so I most solemnly took the vow she wished.

"'In that cabinet, standing in the corner over there, you will find some papers which will explain who her parents were,' my sister continued, speaking with great difficulty, for life's lamp was at its last flicker. 'When you have perused them you will understand how precious she is, and how important it is that she is well guarded till she becomes a woman and can claim her own!'

"As she ceased speaking she pressed my hand in hers. Smiling on me, she passed into the eternal sleep.

"This sad event so distressed me that I could do nothing in connection with the child or anything just then. Calder Dulk led me away from the place to the hotel where we were staying. He advised me to remain alone and keep quiet until the morning, which I did.

"When the morrow came both he and his wife had disappeared, and they had taken every ounce of gold I possessed with them! Nor was this all. They had run off with the child, too, not forgetting to secure the papers relating to her birth, to which my sister attached so much importance.

"I need not tell you what my emotions were under this stinging reversal of my fortune, at this horrible breach of faith, and at my inability to keep the oath I had so recently made to my dying sister.

"I was powerless to follow them, for I had not sufficient money even to pay the hotel bill. There was nothing I could do but return to the diggings, and by hard labour again woo the favour of the goddess of chance.

"I swore then in my heart that, if I ever did attain wealth, I would spend every farthing of it, if necessary, in hunting down the traitor who had betrayed me, and in finding the child who was so infamously stolen from my protection! So, Mr. Sexton Blake, I am here to obtain your co-operation in this search, which must never cease till my end is attained!

"How long is it since this double robbery was committed?" asked the detective.

"Fourteen years."

"Whew! That's a long time. Dulk and his wife may be dead; the girl has become a woman."

"And a beautiful one, too, I am sure. You see," Mr Ellaby explained, "for a long, long time my luck was so bad that I scarcely succeeded in keeping body and soul together. It is only recently that the wheel of fortune has taken a turn. Then, as always happens, gold poured in on me till I was tired of gathering it."

"Have you heard anything of these people since?'"

"Absolutely nothing. But your friend, Gervaise, of Paris, believes that Madame Dulk has visited the French capital quite recently. While there she plundered the aristocracy in a most grand and daring manner. No one answering the description of her husband was seen to visit her. As she has undoubtedly left France, it is surmised that she is either in England or America."

"A very wide address," said Blake, with a smile. "If she is a high-toned adventuress, and is in London, she will be easily found. But you are giving me a tall order. When Stanley was sent to Africa to find Livingstone, his search was at least limited to one continent. The whole world is before me. But I will do my best."

"Do that, and whether you fail or succeed, you shall have your own reward. Day and night I shall be at your service to aid you, and you may direct me as you choose."

"We will work together, and I can promise you heartiness on my part. But, I fear if we find Calder Dulk that I shall have helped to bring about a murder."

It was the detective who spoke.

"What do you mean?" demanded Ellaby.

"Simply this: you wish to meet him, so that you kill him!"

"When I get him will be time enough for me to decide what I shall do with him," replied the other. "I know you cannot give me any useful advice off-hand. I must let you have a little time to digest my story. Meanwhile, will you lunch with me? I have been away from England so long that it will be safer for both of us if I trust to you to select the restaurant."

"With pleasure," said Blake. "Let us stroll as far as Charing Cross. I think best when I am walking. Come round this way," he added, when they stood in Wych Street, and he pointed to St. Clement's Danes. "I must give a minute's call in Arundel Street."

Two other men were watching them from a neighbouring doorway. They took great care not to be seen.

"That's our man," said one to the other, indicating Frank Ellaby. "Once we secure him we shall be as well off as anyone need ever want to be. He's worth millions! You shadow him, Scooter, and make no mistake about it. If you let him give you the slip it will be as much as your skin is worth."

"No, thanks," laughed the first speaker. "That job is not in my way at all."

In the narrowest part of the Strand, between the two churches, the detective and Frank Ellaby became separated in the roadway, and by some evil chance to latter was knocked down and run over by a carelessly-driven hansom cab.

He was carried to the opposite pavement in an insensible condition. Mr. Sexton Blake feared that he was killed outright.

A tall, handsome woman pressed her way through the crowd, which at once surrounded the injured man.

Her hair was as white as snow, and her eyes were coal-black in colour. It was a face time had treated tenderly. It was determined and commanding, too.

"Let your friend be brought to my house," she said to Blake. "It is close here—only round the corner in Norfolk Street. He may die before he can be taken to the hospital. A doctor lives opposite to where I reside."

Gratefully indeed did the detective accept this opportune proposal. Apart altogether from the common sympathies of humanity, which were strongly developed in Blake, he had selfish reasons for desiring to keep this exceedingly wealthy client alive.

It happed, fortunately, that the front apartment leading off the hall, in the Norfolk Street house, was a bedroom, and here they laid the unconscious man.

In a few minutes Dr. Tuppy, from opposite, was by his side making a careful examination of his injuries.

"One rib fractured," he said. "Severe scalp wounds. No danger. Quiet, good nursing, and my advice will soon put him on his feet again. He must not, on any account be removed for some days. I don't know, madame —"

He paused to be supplied with the name of the lady who had called him in.

"Vulpino," she said, in a musical voice.

"Well, I don't know, Madame Vulpino, whether you can possibly allow the gentleman to stay in your rooms, but I can assure you that he can only be conveyed out of them, at present, at the risk of his life."

"I would not turn an injured dog from my roof," said madame, with a touch of emotion. "He shall stay here till he can be taken away with safety. I have an elderly woman with me who will nurse him."

"Excellent," said the doctor.

"Believe me, he shall want for nothing."

"You are indeed a good Samaritan, madame," declared Blake. "My friend is a man of means, and any expenses you may be put to—"

She closed his speech with a proud wave of her hand, which clearly indicated that she would not accept any money recompense for the inconvenience she was putting herself to.

"Now, my dear sir," said Dr. Tuppy, "you can do nothing more for your friend. He is in excellent hands. I will see the nurse, and give her my instructions. He will soon recover consciousness, and then he must have absolute quietness. Of course, you may come round in the morning and see how he is."

Blake, quite easy in his mind, left his new client in the house in Norfolk Street, and set about a careful consideration of the problem which had been put before him, and attending to such other matters as he had in hand.

The next day, at ten o'clock, he called to see how Ellaby was progressing.

The door was opened by a typical specimen of the London lodging-house "slavey."

"Well," he said, good humouredly, "how is my friend this morning?"

"Wot friend? Oh, the gent as was ill yesterday. He's gone."

"Gone? Impossible! How did he go?"

"That's just what missis says when a lodger gets out without paying what he owes. Why sir, how can I tell you how they goes?"

"Madame Vulpino is in, I suppose?" said the detective, as he tried to persuade himself that the girl was talking foolishly, and at random.

"She has gone, too," was the answer. "That was her room he was taken into. Her time was up last night, and she went, and paid up, too. She gave me half-a-crown, and told me not to bother her when she was getting her luggage into the cab. So I didn't. I just went to sleep in the kitchen. My misses was out at the time."

"Will you let me look into Madame Vulpino's room?" said Blake, more perplexed than ever detective was yet.

"Why, of course I will, sir," laughed the girl. "You can come and live in it if you like to pay the rent regular, and gas, and coals, and boots is extra, and I does the boots."

There was no doubt about it. Frank Ellaby was not in that house, nor could any information be obtained as to how he had left it. To make matters worse, no one knew anything about Madame Vulpino.

As for Dr. Tuppy, he simply shrugged his shoulders.

"You are all strangers to me," he said, "and I only know three things about you. First, you call me from my lunch in a dreadful hurry. Second, the removal of the patient last night was quite against my instructions, and will probably kill him. Third, I have received no fee!"

"Frank Ellaby has fallen into bad hands," thought Sexton Blake, as he made his way to his office, feeling very vexed with himself. "Not only into bad hands, but, I fear, powerful ones. I must try and rescue him, whatever it costs me. There can be little doubt that he has been followed from Australia by some desperate gang, who know how wealthy he is. They have succeeded in capturing him in the simplest way possible. They have him in their power, while he is quite helpless. It means a race now between my brains and another London mystery, and I'll back myself to win!"

Frank Ellaby Finds Himself Bound and Helpless in a Cab—At the Old Water Mill.

TO keep the events in this remarkable history abreast of one another as much as possible, we will leave the detective to take his own way of discovering the whereabouts of his rich client, and concern ourselves with Mr Frank Ellaby's own movements.

When he regained his senses he found that he was gagged, and bound hand and foot.

He was in some kind of vehicle which carried no lights. As it jolted along a rough, dark road, it rattled like a ramshackle old four-wheeler. He was stretched along it from the back to the front seat. A piece of plank covered the space between, and gave him additional support.

His injuries occasioned him great pain. At present his senses were numbed, as though the effects of some powerful drug were still clinging to him. He dimly recalled the accident which had befallen him. From then to now was a blank.

He consoled himself at first with the thought that he was being conveyed to some infirmary where he would find ease, and receive kind treatment. But if this was the intention of those who had placed him in the cab, why was he gagged and bound?

The air grew keener, and the part through which they passed more and more silent, till Frank judged that they must now be in the open country. Suddenly the vehicle pulled up with a jerk, which nearly sent the injured man to its other side.

"Wake up, my beauty," said a rough voice.

The door of the cab opened, and Frank's body was prodded playfully with a heavy bludgeon.

"We have reached our destination. You must try and walk into our picturesque country retreat, for you are a bit too heavy for me to carry."

By the aid of the bright moon, Ellaby saw that the gaunt, spectral building which stood before him and back from the road in murky ugliness had been a water-mill.

The big wheel was there yet, dripping with slimy weeds. The moon's rays made the still water look green and murderous. The house itself was as forbidding a structure as it is easy to imagine.

The door of the evil place opened. A man carrying a lantern emerged and came towards them. He wore a mask. His voice appeared familiar to Frank, though, at that moment, he could not identify it.

"Is it all right, Bill Bender?" he asked, addressing the rough driver.

"Quite right. Now, my young swell, I'll just undo the strap which holds your legs, and with a little support from me, you will be able to walk inside. Why, bless me, if you haven't got a lovely gold lever, as big as a turnip, and a chain strong enough to hold a horse. I'll take care of these trifles for you, and if you want any civility from me, you had better make no fuss about this little incident.

"You see," continued the ruffian, "if I have any of your nonsense I can give you a touch with this"—he tapped the prisoner's head with a life-preserver—"or you can have a dose of this."

He produced a pistol, and the barrel gleamed in the moonlight.

"But there," he added, with a coarse laugh, "it won't be any good for you to try on anything. We are a thousand miles from everywhere, as the saying is, and if you try to escape, all you will find will be a watery grave."

They had removed Frank's gag now. Although he was in great pain he addressed them with the utmost coolness and assurance.

"I am too ill and weak to make any attempt to escape, especially from any place which promises warmth, rest, and shelter. Pray help me in, and let me lie down."

"We have ventured to take a few liberties with you to-night," said the man who wore the mask, "but we do not contemplate treating you with violence. To-morrow, however, will show us whether you are a reasonable, or an unreasonable, man—whether we must resort to force or not."

"To-morrow will be time enough for that or any other discussion. To-night my pain is so great I can hardly stand. I beg of you to take me indoors. The man who guards me to-night will have an easy task."

"I am glad to see you take matters so coolly. You shall have all the attention this place affords. Let me warn you. You are as far from human aid here as though you were in your tomb."

A Threat of Torture—Left to Starve to Death.

"HOW is your patient getting on now?" The man who had worn the mask asked this question of the ruffian he had called "Bill Bender."

The former was sitting before a well-spread table, enjoying a hearty meal, and the latter had just returned from the room which was to prove Frank Ellaby's prison.

"Beautiful!" was the answer. "I never saw a man in his position take things so cool and comfortable. He could not be more contented in his own hotel."

"I'd rather he made a fuss. He'll prove all the more troublesome to us in the end. These calm, determined men are more difficult to deal with than excitable people."

"We can soon knock the nonsense out of him. What made you cover up your face with that mask to-night, Mr. Calder Dulk?"

"Why, you see," came the slow answer, "after he has paid his ransom, I don't want it to be in his power to take proceedings against me when he is once more free."

"When he is once more free?" repeated Bender, with a low chuckle. "You don't mean that he ever shall get free? One you have got his money, he will only be a danger to you alive. He'll have to go where the rest have gone."

"I neither contemplate, nor do I recommend, violence," said Dulk, with a queer look in his eyes; "when we obtain possession of the cash, I shall leave him here, and you can do what you like with him."

"Thanks; and I shan't forget to keep my eyes on you, either," muttered the rascal.

Frank was put into a comfortable bed, in a warm room, and he was well supplied with everything in the way of nourishment he could desire.

He felt that whoever had bandaged his injuries had done the work with some skill.

There was no window to the apartment, and all escape from it was prevented by a iron-bound oaken door, which was secured by bolts and an iron bar on the outside.

Except for the fact that he was a prisoner in that sinister building, and probably in imminent peril of his life, he might have felt as contented there as in any other place he could have been taken to.

After a long and grave consideration of his present position, he came to the unjust conclusion that Mr. Sexton Blake had proved a scoundrel, and for his own ends had made him a prisoner.

"Yes," thought Frank, "it must be Blake. Not another soul in London knows who I am, or what I am worth! I wonder how much he will want to set me free? I wonder whether I shall ever yield to his infamous demands? I think not. He has played a dangerous game, and he shall suffer for it, Unless they kill me outright. He could not have planned the accident which befell me, but my helplessness may have suggested this cunning plot. Opportunity is the great tempter. I suppose to-morrow my gaolers will tell me their intentions."

When he awoke on the following day, he felt refreshed, and so hungry, that he looked forward eagerly for the appearance of breakfast.

Frank had a remarkably strong constitution, which travel, hardship, and exposure had hardened, and not shattered.

In spite of Doctor Tuppy's prognostication, his sudden and queer removal had not retarded his recovery. He felt in himself that a few days would see him on his feet again, and in fair health. His only visitor the next day was "Bill Bender."

He brought a jug of coffee and a couple of slices of bread and butter.

"We are not going to feed you up with high-class food," said the man, "because it might fire your blood, and we mean to keep you nice and cool." This fare, rough as it proved, was very welcome to Frank.

"Now," continued the ruffian, drawing a packet of papers from his pocket, "I'm going to leave these things with you for your careful and best consideration. One is a cheque on the London Joint Stock Bank for twenty thousand pounds. Oh, my fine millionaire! We've got friends in Paris, who told us which was your London bank."

"Gervaise, of course," Frank thought; "he has planned this with Sexton Blake. I have plunged my head right into the hornets' nest."

"All you have to do," continued "Bill Bender," with a grin, "is to sign this cheque, and then, in case you should not have so much cash as that at the bank, here's a little power of attorney for you to put your name to. It authorised Mr. Cornelius Brown to realise on any stocks or shares, bonds or certificates, personal or real estate, you may possess. Once you have signed these different documents, and we have secured what we have justly earned, you will be free to leave this place and enjoy yourself as you may think best. So it just rests with you, Mr. Frank Ellaby, how long you remain here. We can wait for years, if necessary. You have not one living person on earth likely to trouble themselves whether you are alive or dead!"

How true this was Frank knew only too well, and to his sorrow.

"I can't prevent you from leaving the papers here," he said quietly; "but I will never sign one of them as long as I live!"

"That's what you think now, but we will make you change your mind soon."

"I should be a fool to sing."

Frank spoke carelessly. "So long as you want my authorisation to those papers, you will keep me alive for the gratification of your own greed; but once that is satisfied, it will not matter to you whether I am alive or dead. While I am alive I have hope."

"Well, I never thought of that! How clever you are! But, look here; this matter has been put into my hands, and I am going to work it off quick. I don't suppose you are a bit more frightened of death than I am; but there's something worse than that, and it's torture. If you won't come to any reasonable terms, I'll starve you into submission! Do you hear?"

"You cur!" said Frank, contemptuously. "Why, you would run a mile from me, if I had my strength, and we were on equal terms. As it is, I'll bring you to the earth!"

On the little table by the bedside the man had placed a metal ink-pot and a pen, with the papers to which he wished Frank to put his signature.

The prisoner seized this pewter inkstand, and hurled it, with all the force he could command, full in the face of his brutal custodian.

The blow was unexpected, and Bill dropped to the ground like a log of wood.

Frank thought that the moment for his escape had come, and he tried to struggle into his clothes.

Alas! he was so weak that he had to sink on to the bed, and cling to it, trembling from the effects of his recent exertions.

This gave "Bill Bender" time to regain his feet, and he soon had his prisoner back again between the sheets.

"So that's a sample of temper, is it?" snarled Bill. "I shall look our for you in future. You take my advice. Sign those papers while you have a chance. I'm a bit rough to deal with when I'm put out, and you have marked my figure-head for life. Until those papers are signed you don't get bit nor sup from me."

With a curse Bill left Frank Ellaby to recover from his prostration as best he could. For two days Frank had neither food nor drink given him.

In one way he suffered terribly, but this heroic treatment helped his injuries to heal up in a miraculously short space of time.

He then began to consider whether, after all, he had not better attach his signature to the documents which were still at at the side of his bed.

If he did not do the bidding of these wretches, it was certain they would starve him to death!

Circumstanced as he was he could lose nothing by agreeing to their terms. If he ever did get free he promised himself that he would punish Mr. Gervaise, of Paris, and Mr. Sexton Blake, of London, most severely for their villainy. He hoped, too, that he would be able to make them disgorge the money they had wrenched from him.

Little did he imagine that both these wrongly suspected gentlemen were at that very moment doing all they could to find and rescue him!

The next time "Bill Bender" put his head into the room, with the question whether his prisoner had come to his senses yet, Frank Ellaby said—

"I have signed all you wished me to. Bring me something to eat and to drink. When you have got your money I suppose you will see that I am released from here?"

"Not much," said Bill, with a coarse laugh, as he thrust the papers into the breast pocket of his heavy overcoat "Now, listen to me. If you had not been so obstinate, I would have done fair and honest by you. But you've bee pig-headed, and you've kept me from my pleasures and enjoyments. More than that, you have marked my face. The consequence of which is that I'm going to leave you here to starve. You can't escape. No one can come to you. Here you shall remain and slowly starve to death."

With this speech the ruffian left the room, bolting and barring the door behind him. "He tells the truth for once," groaned Frank, "there is no help of hope for me. I see nothing before me but a dragging out of an existence which will be torture till the end of its last thread!"

Gervaise, of Paris, Appears on the Scene—The "Red Lights" of London—The Newspaper Boy's Story—Finding the Old Mill—Dragging the pool—Discovery of a Body.

"SO far all my searchings have been in vain. I have failed to find any trace of Mr. Frank Ellaby."

So said Sexton Blake to his fellow-worker, Detective Gervaise, of Paris, to whom he had telegraphed directly it became know that the millionaire had disappeared.

"I blame myself very much for this catastrophe," said Gervaise, gloomily. "I should have described that woman to you, and have put you on your guard against her. She was as anxious to secure Ellaby as he was to find and punish her. She wanted me to shadow him before he called on me to get information concerning her. I intended coming to England, to put on her track, and I calculated that your speedy discovery of her would bring a substantial reward from our wealthy friend. You have already guessed that this Madame Vulpino and Mrs. Calder Dulk is one person. This unfortunate accident has played havoc with my plans. Fate seems to have worked altogether in favour of Ellaby's enemies."

"On the night of his disappearance," said Blake, "the woman, accompanied by a shabbily-dressed man, drove from Norfolk Street to Charing Cross Station, where she took two tickets for Paris. She and her companion both entered the Continental train, but it is quite certain they never went by it. They must have left it when it was on the point of starting."

"The booking to France was a mere blind—to lead you on to a false scent. There can be no doubt that the woman is still in London, and probably not far off. Very likely the man who accompanied her was Dulk himself. Within a day or so someone will turn up at the London Joint Stock Bank with a cheque signed by the missing man. As we have warned the authorities at the bank to detain any such messenger, I hope to reach the conspirators through that means. There can be no doubt that their object is to extort money from their prisoner—"

"And when they have succeeded what will become of him?" suggested Blake.

"Ah, that is just where all the danger comes in," said Gervaise gravely.

"I wonder if the 'Red Lights, have any hand in this kidnapping?"

"Who and what are the 'Red Lights,' my friend?"

"It is a new and formidable society of professional lawbreakers of every class. Its conception was due to the fertile brain of a young, well-educated fellow named Leon Polti. It was his idea to join together into one powerful association the most expert operators in all branches of crime. The cleverest burglar throws in his lot with the most accomplished forger, and so on through the whole list of police offences. The notion is a brotherhood of crime, with meeting places, and correspondents all over the country, working for the common good of their own combination, and to the hurt of honest people.

"If Polti could realise his highest ideal and conduct such a gigantic organisation, on strictly business principles, and with keen method, I fear the police would be beaten at every turn, and crime would be triumphant in the land! Luckily, rogues never do agree together for long.

"They will observe no laws—not even their own. So Polti's vast scheme will remain a dream, and nothing else, to the end of time. This case we have in hand looks something like the work of his gang. Watching and waiting for the rich man coming from Australia, and sending the woman over to Paris to shadow him, suggests his methods. I daresay I can find him. He knows me. We will see if we can discover anything of his doings."

At this point their conversation was interrupted by the appearance of a shaggy, flaming head of red hair, which thrust itself into the office through the half-opened doorway.

"Well," interrogated Blake, "what do you want?"

"Please, governor, I'm the boy wot stands about the top of Essex Street, selling papers, and you've given me many a 'brown,' you has."

A body followed the head, and there stood disclosed to the two detectives, a short, bright-faced boy, who looked like nothing so much as an animated bundle of rags. His tattered trousers barely touched his knees, and strips of time-eaten cloth fluttered round his thin, discoloured arm.

"I've got no 'browns' for you to-day," said Blake, waving his hand impatiently.

"Oh yes, you has, sir," the street boy answered, with a knowing shake of his glowing locks. "Wait till you 'ear wot 'ive got to tell yer, and then I think you'll be good for a 'bob.' It's like this 'ere. Tommy Roundhead says as 'ow you want to find out about a 'toff as was taken out of a house in Arundel Street, late Thursday night. Well, I can tell you all about that 'ere. 'Cos, why? I helped in the job myself."

"If you can help me to find that gentleman," said Blake, with sudden energy, "I'll make a man of you! We won't trouble about shillings. Pounds and pounds shall be spend on you."

"We can decide what to do when we have hear his tale," said Gervaise, with more caution.

"It's like this, governor. I was walking down Arundel Street, wondering where I should pitch myself for the night, when a four-wheeler drives up, and stops at that house. The driver jumps off the box, and I see, at once, that he weren't a reg'lar cabby. 'Ere young Vesuvius!' 'e cries, 'old the 'osse's ead.' The door of the 'ouse opens without him knocking or ringing. I sees that there's a sort of bed made up in the cab. In a minute or two the driver comes out with another man. Between them they carries a third man, who, if he ain't dead, 'as lost 'is senses. They puts this helpless chap inside, and the coachman, springs on to his box again. 'I shall be there before you,' says the man who is standing on the pavement. He puts 'is 'and in 'is pocket, and, after fumbling about a bit, he pulls out 'arf a sovereign.'Take that,' he says to me, 'I ain't got noffink smaller.' He walks away quick.

"'Well,' thinks I, 'if I gets 'arf a quid for 'olding the 'oss while they puts the swell into the cab, perhaps I shall get a bit more if I'm there to 'old it when they take 'im hout'. So I gets up on the back of the cab, and clings on. But, bless you! I was taken right away to Barking. I didn't get off because I made sure the cab would be coming back again. At last we stops before a tumble-down old water-mill. Then the driver brings out a blunderbuss, or sumfink deadly, and a reg'lar hold-fashioned life-preserver. I take to me 'eels in case they should want to give me one on the 'ead. I waits about hoping to see the cab go back. But they puts in the stable there, and I 'as to walk. I falls in with a tramp, and he sneaks my half sovereign. Then the police collars me for being a vagabond, and that's how it is I ain't been at my hold pitch the last day or two."

"This is new indeed!" exclaimed Gervaise. "Can you lead us to this old mill?"

"It's a hawful lonely place," said the boy, "but I think I can find it again."

"Le us go at once," suggested Gervaise.

"We must lose no time," agreed Blake, meditatively, "but we need to go to work with extreme caution. I don't like that remote water-mill. It looks murderous in my eyes. I our man is still there, and alive, his gaolers may offer a desperate resistance. The quickest way will be to take the train to Barking."

"Can't do it, governor," declared the lad; "I shall never find the place if I don't go the same way as that four-wheeler did."

So they hired a hansom, and it took half a day to light on the spot where "Bill Bender" had threatened Frank Ellaby with bludgeon and pistol.

"The place is deserted," said Blake. "I fear the worst."

"We shall have no difficulty in getting in," said Gervaise, as he threw the weight of his body against a rotten and ill-secured back-door, which at once flew open.

The rats infesting the place scampered before them as they walked through the musty passages and gloomy rooms.

Upstairs they came on a heavy door, barred and bolted on the outside. Their hearts beat high as they undid these fastenings.

They felt sure they were on the point of entering the room where Mr. Ellaby had been kept prisoner. Would they find him there now, was the question which trembled on the lips of both, but neither spoke.

They were not hopeful of discovering him alive, for he had not answered the shouts they had raised on entering the building. Was his murdered body to meet their horrified gaze?

"Empty, as I expected," said Gervaise. "What a strong room it is? It might have been built for a prison cell. He has been here, that is quite clear. There is his bed, his writing materials—"

"And," said Blake, "an absence of water and of other food!"

"They left him to starve to death!" Gervaise added excitedly, "but he has escaped by tearing the fire-grate from its settings. See how loose the bricks behind are. He could not have had great difficulty in making the hole through which he must have crawled. There is a room beyond—long, narrow. We must follow his example, and see where it leads to."

"His footprints on the dusty floor can still be traced," said Blake. "The open window at the end shows he escaped that way. Why has he not communicated with me?"

"Because," answered Gervaise impressively, "his body lies at the bottom of that still, black-looking pool. You observe, this window is exactly over the old wheel of the water-mill. He must have stepped on to it. His weight would make it revolve; he would be hurled into the water. Probably one of the flanges would strike his head, and render him insensible. Then the weeds would catch him in their deadly embrace.

"See! There is his hat floating on the green scum! We must have this water dragged!" As soon as they could procure drags and other aids, the pond was most effectually dragged. After some hours' work, and with much difficulty, they brought a corpse to the bank, about which lank weeds still clung.

"Unhappily, we are too late to preserve the life of Frank Ellaby, for here his body undoubtedly lies. The one thing left for us is to make our very best effort to bring his murderers to justice." It was Gervaise who spoke.

"And that we will do as certainly as we stand here," answered Sexton Blake.

The Vicar's Secret—A True Lover—The Cheque for £20,000—Arrested.

IN this chapter we must take the reader to the old-fashioned Sussex village of Downslow, and to the ivy-clad rectory there, in the library of which sat the Rev. Frederick Briarton, in grave conversation with Ernest Truelove, a farmer's son, who was on the eve of leaving his old home for London, with the intention of entering one of its medical schools and winning a surgeon's diploma.

"I will not conceal from you my satisfaction at knowing that you have won the love of my dear Rose," said the clergyman, "for I have confidence in your high regard for truth and honour. I am old, and it is idle for me to hope that I can be much longer in this world. I shall die the happier for knowing that Rose has linked her life with one who will do his utmost to shield her from its storms. But, my dear boy, I have a secret to confide to your keeping, which may make you desire to withdraw from the engagement you have entered into."

"Nothing can possibly happen to make me do that," said Ernest fervently.

"Prepare yourself for a shock, my friend. Rose is not a daughter of mine! I do not even know who her parents are."

"You have succeeded in surprising me," said young Truelove. "I love Rose for herself alone, and I care not whose child she is!"

"She is the essence of goodness and purity. Many years ago I was chaplain to one of Her Majesty's prisons. A few days before I resigned that appointment to commence duties at a small living in Yorkshire, which had been presented to me, one of the female convicts, a handsome and accomplished woman, sent for me, and, upon her knees, implored me to protect a little girl her arrest and sentence had compelled her to leave in the care of some rough, illiterate people living at Hammersmith. She said that the child was not her own, that it had a great future before it, and that when she was released she would repay me for my trouble, and restore the child to its proper sphere. As I had not been blessed with any children of my own, I was ready enough to adopt Rose. My poor dead wife grew devotedly attached to her, and she was brought up as our own daughter. The time soon came when I began to feel terror lest her convict guardian should appear at our home, and blight its happiness by claiming our darling Rose.

"By the will of an uncle I was practically compelled to change my old name of Sparrow to the one I now bear—Briarton. I have moved about a good deal, too, and perhaps that is why the woman has not found me. I am glad to have eluded her. I would go very much against my moral grain to have to deliver up so pure and gentle a girl to a woman who has once worn a convict's dress. I have never had the courage to tell Rose the truth. She firmly believes herself to be my child."

"Let her die in that faith," said Truelove, promptly.

"It would be cruel to her to tell her the truth now, and no useful purpose would be served. She herself is too good for me to believe that her parents were bad. I will work hard, and in a little over three years I shall secure my diploma; then I can give her a name which shall be her very own, and she can defy anyone who may wish to claim her."

After this, Ernest spent a long time with Rose herself, till the hour came when he had to drive to the station and catch his train. They had repeated their mutual vows over and over again.

When evening prayers were said in the vicarage, the rector introduced a fervent one for the safety and prosperity of Ernest Truelove, amid the pitfalls and temptations of the huge metropolis.

Meanwhile this young gentleman, having spent an hour or so in Brighton, was dashing on to London at express speed, his regrets at leaving his old friends and the scenes of his youth lightened by this sense of the vivid change which was now to colour the daily routine of his life.

His only fellow-passenger was a young fellow who looked about his own age, but he might have been older. Slight in build, with a creamy skin, and large dark, fascinating eyes, a round smooth chin, and a delicate mouth, he was decidedly effeminate in appearance, and yet there lurked in his every graceful movement a suspicion of sinewy and uncommon strength.

The two had easily fallen into conversation, and this had led to an exchange of cards.

The stranger's bore the name of—

"Leon Polti."

"So," said the latter, to whom the innocent Ernest had confided much of his past history and many of his plans for the future, "you want comfortable lodgings in the centre of London? Ah! Now I don't think you can do better than take up your quarters at the house where my sister and I are temporarily located—99, Bernard Street, Russell Square. It's no distance from Charing Cross Hospital. The landlady is the most obliging creature I ever met with, and the cooking is capital. I know she has a bed and sitting-room to let. Probably you don't mind if they are a bit high up. You can drive home with me to-night. There will be no harm in seeing the place, even if you should elect not to take the apartments."

"I am very much obliged to you," said Ernest. "I have no doubt the place will suit me very well indeed. I suppose, though, I shall have to go to an hotel to-night?"

"Not a bit of it! If you like the accommodations, Madame Dulk, the landlady, will make you perfectly comfortable at once."

Ernest was charmed with the house and with his new friends.

The same evening he dined with Mr Polti, and he saw that this gentleman lived in quite high style. The table was spread with delicacies, in and out of season, and there were famous wines.

"My sister is out of town to-night," said his host. "I hope to introduce you to her to-morrow."

On the following morning he encountered a dark young lady on the stairs. The likeness to Leon Polti was so striking that he could not doubt her near relationship to that gentleman, so he ventured to address her.

"Oh, yes," said, with a laugh, which disclosed a set of brilliant teeth, "I am Nizza Polti. My brother has told me so much about you. I hope we shall be great friends. Some business has called him away; he will not be back for a few days. But," she added, "Madame Dulk generally sits with me in the evening, and any time you like we shall be glad if you will join us."

The days passed very pleasantly with Ernest. Some evenings he saw Nizza, and on others Leon. Their own affairs so fell out that they were never able to be together when young Truelove was in the house.

One evening as Leon was sitting with the medical student in the latter's room, Madame Dulk tapped at the door, and brought word that a gentleman waited below to see Mr. Polti on most urgent business. "Bother him!" said Leon. "Can't he come in the morning?"

"No. He says it is imperative that you see him now."

"He shall wait till I have finished this cigar, at any rate. Tell him so, whoever he may be. I hate these inquisitive people," he added, with a yawn, to Ernest.

When he did at last deign to descend the stairs he found Calder Dulk waiting for him. He took him into another room.

"You have an odd way of disturbing one at most inconvenient moments," said Leon. "Well, what is it you want me for?"

"The rat in his cage has eaten his cheese," replied Dulk, harshly, annoyed at the other's assumption of cool indifference. "In other words, Mr. Frank Ellaby has signed all the papers you made out for him to put his signature to. I've got them with me. It's for you to turn them into good current gold. Our part of the business is finished, and that has been the roughest and the worst section of it. Now you can put in some of your 'fine' work, as you call it."

"I'm afraid you have come in a sneering mood, Dulk." Polti drawled his words out lazily. "And really it does not become so jovial a fellow as yourself. What has been done with Ellaby?"

"I left him to 'Bill Bender.' You know what he generally does with them."

"It's always force, and never persuasion, with you people," said Leon contemptuously.

"These papers seem to be all right," he continued. "They shall have my attention as soon as possible, and you will all know the result."

"That won't do for me," said Dulk fiercely. "I mean having the lion's share of this plunder. Why, if it hadn't been for me you would not have known of the existence of this Frank Ellaby. But for my wife's promptitude it might have taken you months to capture him. Those papers represent an actual little gold mine. It is through our work, and through the work of no one else, that they have been obtained, and we mean being paid in full! You talk about us all being equal. You are like the man in the play. He wanted his followers to be equal so long as he was chief. No doubt you would like to be crowned 'Monarch of Criminals,' and 'King of Crime,' and all that kind of thing; but we are not quite such fools as to give way to you."

"You amuse me, Dulk," said Leon, throwing himself back in his chair, and smiling dangerously. "Perhaps you will condescend to remember that, but for me, there would have been no house in Arundel Street to take your victim to—the man you have twice plundered. But for me there would have been no old mill in which to torture him into subjection. But for me you would not now have good broadcloth on your back. But for me the only possible roof for you would be the strong one of the gaol. You want the lion's share of this money? You shall have it all, my friend. Take back your papers; do what you will with them. I wash my hands of the affair, of you, of your wife. You cannot play either the role of knave or honest man. Well, I am better without you. Good-night."

"Leon, Leon," plead Dulk, with a white, anxious face, "don't talk like that! You know I dare not work those papers! Come, come; forgive me! I spoke hastily; I did not mean what I said. Take the papers again. Work as you choose with them; I make no conditions."

"Make conditions!" repeated Leon. "The world must turn inside out before you will ever be able to dictate to me. Leave those documents. Go away. I will see what can be done. It is a risky business, and I know the hazard better than any of you. If a hitch occurs, there must be instant flight from here."

"Yes," said Polti himself, when he was alone; "I see that I am in most danger from my own followers. They would kill me to gain possession of Frank Ellaby's money. Dulk is the most likely man to strike the first blow. Knowing where my peril lies I can evade it. Extreme caution and swift flight will save me, and nothing else. I thank thee, Fate, for throwing that innocent youth Ernest Truelove in my way!"

On the following morning the student again met Nizza Polti on the stairs.

"My brother has been unexpectedly called away this morning before you were awake," she said in her pretty way, shedding the full light of her eyes on his face. "He wants you to do a small favour for him, and I am sure you will. It is only to get a cheque cashed at the London Joint Stock Bank, and meet him to-night at Charing Cross Railway Station with the money. He is going to Paris with it."

"I shall be delighted to be of any service to him, and to you," said Ernest. "Why! this cheque is for £20,000! Quite a fabulous amount!"

"My brother's transactions often run into five figures." she answered, with a smile. "If the cheque were for a small sum, I could do the business myself. He prefers to trust it to you, because you are stronger and cleverer than I am."

"Directly I have had my breakfast I will go to the bank," declared Ernest, in his impulsive way.

"There is not such a great hurry. So long as you are at the bank by eleven o'clock, that will do."

Just as Ernest was leaving the house a cab drew up at the door. To his great surprise, it contained Rose and the Rev. Frederick Briarton.

It chanced that just as these two reached the house, Madame Dulk was standing at the dining-room window, and she had a clear view of them.

She drew back hastily. Gleams of satisfaction shot from her eyes.

"At last I have found him!" she said to herself. "The clergyman to whom I confided the child. Doubtless that is Rose herself, grown into a beautiful woman. I will lose no time in regaining my prize. My husband and Polti and the rest may have their big hauls, but I shall now be better off than any of them!"

"Dad had to come up to London by the very first train on some business in the City," Rose explained.

She was flushed with excitement, and with the delight she felt at seeing her lover again. "So I coaxed him to let me come, too."

"We thought we would give you a surprise," laughed the vicar, "and join you in a little lunch, if you have such a handy thing in the house."

"Only too delighted to see you," said Ernest; "but I must go to the City myself. We can all go together in the cab you have come by, and talk as we go.

"My business is with the Joint Stock Bank," he added, "and it won't occupy many minutes. After that I shall be entirely at your service. What do you think, Mr. Briarton? I'm going to change a cheque for twenty thousand pounds!"

The figures were sufficiently large to impress the rural clergyman, and to awe Rose.

Ernest briefly explained how he chanced to be in possession of so valuable a piece of paper.

They watched him, as he, with a great air if importance (which he could not resist), entered the bank. They saw him emerge from its portals, and then a dreadful thing happened.

A tall, broad man tapped him on the shoulder.

Before he could say a word a pair of handcuffs were thrust on his wrists. Two other men came from across the road with a seeming air of authority. They were seized, too, and treated in the same way.

The police had taken Ernest Truelove into custody. They had also arrested Mr. Gervaise, of Paris, and Mr. Sexton Blake, very much to the complete dismay of both these notable detectives.

Calder Dulk and Leon Polti watched these proceedings from a safe corner, and then made off with all the speed possible.

Poor Rose uttered a cry of distress, and the Reverend Mr. Briarton sprang on to the pavement and was at once in the midst of the excited group, standing shoulder to shoulder with Mr. Frank Ellaby!

The Release of the Prisoners—Flying from Justice—"I Will Kill You Both."

"SO I have made a good haul, and caught you all at once," said Ellaby, with a grim smile. "I am sorry you have turned out a rogue, Gervaise, for I had formed another opinion of you. I did hope that you, Sexton Blake, were honest, yet you have joined in as vile a conspiracy against my life and fortune as man could devise. As for you," he added, addressing Ernest Truelove, "you have a noble, manly face, which makes me sorry to see you associated with these rascals."

"I do not know what all this means," declared the Rev. Frederick Briarton, "but I do aver that this young gentleman never did a dishonourable action in his life, and, if you dare to detain him, it will be at your own peril. He was simply asked to get this cheque cashed by people who lodge in the house where he has apartments."

"It was Leon Polti's sister," Ernest commenced.

"Ah!" Blake interrupted, "this, as I guessed, is the work of the 'Red Light,' and I hope we shall be able to capture and convict the whole gang. I forgive you, Mr. Ellaby, for thinking I had something to do with your kidnapping; but had you gone to Scotland Yard, instead of to the City Police, you would have heard that Gervaise and myself have toiled day and night to rescue you. Only yesterday we discovered and old mill. We had the pond dragged, and we found one body which, at first, we thought was yours—"

"No, I am still alive," said Frank, "though I did get a ducking there. I hope, Blake, your tale is true."

"If we all drive to Scotland Yard, you will soon be satisfied on that point. It's my opinion, Mr. Ellaby, that this young man has simply been the dupe of the daring Polti crowd."

"I am a clergyman of the Church of England," said Mr. Briarton; "and I have known Ernest Truelove for many years. I am convinced he is incapable of committing a criminal action. I must insist on his immediate release from custody."

"Oh, Rose, Rose!" said Ernest, as his fiance joined the throng. "I do wish you had been spared the pain of seeing me so disgraced."

"So your name is Rose?" questioned Frank Ellaby, regarding her fair, fresh young face with interest. "Many years ago I had a little girl stolen from me bearing that name. She must be about your age now. I would give much to find her."

"That is a matter we can discuss some other time," declared the rector, and with such significance that a sudden hope sprung up in Frank's heart. "Ernest Truelove must be released!"

It took very little time to prove how far from the truth was the charge against Messrs. Sexton Blake and Gervaise, to whom Mr. Ellaby made a most handsome apology.

Nor was it long before this gentleman was persuaded to withdraw every imputation against Ernest Truelove; and later, when he knew more of him, he decided to make him reparation for the wrong to which he had been subjected.

They all journeyed to Bernard Street, hoping to effect the capture of Madame Dulk and Nizza Polti, if not of Polti himself.

No one answered their repeated knocks or continuous ringing of the bell.

"The birds have flown," said Blake. "No doubt Mr. Truelove was shadowed to the bank. When he was seen to be taken into custody the warning note was sounded, and the ducks have taken unto themselves wings and vanished. Gervaise and I will see that the railway stations and the wharves are watched. Every effort shall be made to prevent the escape of the culprits. Now we know them there should not be any difficulty about this. You gentlemen had best make yourselves comfortable at some good family hotel where I can visit you later on, and report progress. Say the Silver Bell, at Charing Cross. I really don't think you can help us now in any way. Too many cooks, you know, spoil even good broth."

"All my personal belongings are in that house," said Ernest, ruefully looking up at its windows.

"I daresay you will get your luggage all right," returned Gervaise, with a smile, "but that is a department of our business which can well afford to wait. We have got a moment to lose, so farewell, my friends!"

Gervaise was right. Every second was previous. Already much valuable time had been squandered.

Even as he spoke, Calder Dulk and Nizza Polti stood on the platform of King's Cross Station ready to step into a fast train soon to start for one of the Northern centres.

The appearance of Mr. Frank Ellaby outside the bank had filled Dulk with the direst consternation. He judged there could be no safety for him in England now, especially as Ernest was in custody, and could put them on the track of Madame Dulk, who had gone he knew not where.

"Ah!" he said, when he and Nizza had settled themselves in the carriage, and the train was almost on the move, "we shall get out of London all right, and then entire escape won't be so very difficult."

The whistle sounded, and the great engine gave on mighty gasp of relief.

They were on the move, when the door was torn open, and a man threw himself into the carriage. "Keep still," he yelled, placing himself opposite them. "If you move an inch I'll shoot you both like the dogs you are." He pointed a pistol at each head.

"So," he continued, "you've got possession of the plunder, and you mean to cheat me out of my share—me, who has done all the work, too! It isn't the first time you have tried on that game; but it shall be the last. You look very pretty in that woman's disguise, Leon Polti; but it won't work with me, because I know it. I always swore if a pal played me false that I would kill him. I mean to kill you both!"

They knew that their first stoppage was Peterborough, and that they were completely at the mercy of this desperate man, who was none other than Bill Bender, and who laughed to scorn the terrors of the law.

A Struggle for Life—Thrown from the Train.

IT was some time before the two men recovered from their surprise. "Don't be a fool, Bill Bender. We have not got a farthing of Frank Ellaby's money. The game is up; the detectives are after a lot of us. We are flying out of London, and mean to lie quiet in the country for a time; that's why we are in this train."

It was Calder Dulk who spoke, half pleadingly, and with somewhat of a reassuring tone to Bill Bender, who still covered him and Nizza Polti with his pistols.

Dulk looked very helpless with the muzzle of the deadly weapon pointed straight at his heart.

"You always were an idiot, Bender," said Nizza, talking in his natural voice—for Nizza and Leon were one.

The disguise was so perfect that only very few of his own followers knew that he did not possess a sister. By the aid of this change of costume he had more than once deceived his confederates, and passed freely out from among them, when very little would have made them tear him to pieces. "Put those silly things down. They are more likely to hurt you than me."

"I am glad you have turned up," Leon added in his cool, business way. "I wanted to see you. I fancy we may yet get hold of that money, and want your help, my friend Bender."

They had emerged from King's Cross tunnel now, and were beginning to whiz along at a rate which soon promised exciting speed.

"None of that for me," said Bill. "I've had lots of it from you, and I know you. Now then, young gentleman in the skirts, tumble up the gold. You had the cheque right enough, and you've got the money."

"Certainly I had the cheque," acknowledged Leon quietly, "but you don't suppose I was going to be so foolish as to present it myself?"

"No," growled Bill, "you've all been clever enough to leave me to be the only one who can be identified as being connected with this job. One wears a mask and the other hides himself. Then you try to do me out of the money and leave me to swing, while you enjoy yourselves with wine and other luxuries."

"I sent a young country friend of mine to the bank to get Frank Ellaby's cheque cashed," Leon spoke impressively, "and I suppose he got the money. Dulk and I watched from a safe distance to see if things were all right. All we know is, that when our young friend left the bank he was taken in charge by the police. Just pay particular attention to this, Bill—Frank Ellaby was there, too, waiting for him!"

"What!" exclaimed Bill, so astonished at the news that he relaxed a trifle of his vigilance.

"How could he have escaped from the mill? I made sure he was a corpse by this time. He won't rest till he finds me. Yah!" he exclaimed, with a sudden change of demeanour, "you think I am a kid, and you are trying to put me off with those fairy tales till we stop somewhere, where you think you can get help. Come on, pay up, or I'll fire."

"Don't be so thick-headed, Bill; I tell you we have not got the money. Besides, I should never think of swindling you; you are too useful to us. Why don't you search us? Perhaps that will satisfy you. You can commence with me."

"So I will," said the thoughtless ruffian, laying his pistols by his side.

Leon was full of tricks. This proposal was only a ruse to put Bill Bender off his guard, and to enable them to deprive him of his weapons. It would have succeeded admirably had not Leon been too quick.

He stretched his white hand over to secure the deadly weapons before Bill had half risen from his seat.

The burly bully saw what was intended, and Leon was felled to the floor of the carriage, rendered insensible, and his body kicked under a seat in less time than it takes to write these lines.

Thinking his opportunity had come, Calder Dulk now sprung on Bill Bender, to be received by him in his powerful grip.

Dulk was a man of weight and muscle.

Knowing the one he had to deal with, he was sure this must prove a struggle for very life.

Nothing would ever now persuade Bill that there had been no intention to deprive him of his share in the cheque obtained by such desperate means. His teeth were set. His eyes stood out of his head. His whole system throbbed with one idea, and it was a fierce one—to crush Dulk.

This so absorbed his every faculty that he did not hear the rush through the air of the train, the rattle of the carriages, or the frequent wild shrieks of the engine.

No pleadings for mercy from human tongue could touch him!

Dulk's veins rose up his forehead, knotted and black. His face was horror-stricken. He knew that a relentless demon was grappling with him, and it could only be by a superhuman effort that he could escape the death sentence written on that implacable face.

Strive his utmost he did, straining every muscle and nerve.

At one moment the two stood silent, and looking as firm as a pair of Roman wrestlers cut in marble. When the train gave a lurch they were thrown heavily with it. Then came a fierce, panting struggle on the floor. Some seconds one had the advantage, to be quickly wrenched from him by the other.

As they managed at last to struggle to their feet, they never for an instant released their hold on each other.

A thick hot breath fanned their cheeks as a blast from a furnace all the time. The solid seating on each side of them in the narrow passage of that compartment made it difficult for either to throw the other. So each strove with slow, persistent effort to reach the pulsating throat of the other. Bill Bender was the first to win in his deadly effort.

As his thumb and finger closed on Calder Dulk's throat, a groan of triumph escaped him. Now he could throw his whole weight against his victim, for with the latter's lack of breath the muscles of his arms and legs relaxed.

The two fell against the carriage door. A third of Dulk's body was already out of the open window, which had no protecting rail in the middle of it. Just then they were entering a tunnel.

"You are best out altogether!" growled Bill, lifting up the legs of the man, and letting him drop out into the darkness.

A crimson flash of light from the fire of the engine illuminated his ghastly white face as he was swallowed up by the relentless black of that stifling excavation.

"It's Leon Polti who has the money; that's certain, or he would not be got up like a girl," muttered Bill, and he at once commenced to roughly search that gentleman.

"The other has got it after all!" he cried, in disgust. "There all that money lies on the line for any navvy or porter, or anyone to have for the finding. I must have a try for it."

The signal towards the exit of the tunnel was against the train, and it slowed.

Bill took advantage of this opportunity, and he dropped gently off the footboard into the gloom.

Leon, now he was lone, sprang to his feet, and, taking down a small bag from the luggage-rail, he quickly made a complete transformation in his dress.

When the train stopped at Peterborough, and he stepped gingerly from his carriage, he appeared in such attire as would have befitted the most exacting up-to-date Bond Street swell.

"I am glad Bill and Dulk have both gone that way," he reflected, with an amiable smile. "It is an experience they are not likely to recover from, and they were beginning to get troublesome."

The Drugged Coffee—Coronet or Grave?

WHILE the detectives were pursuing their investigations, Frank Ellaby's party engaged quarters at that cosy and eminently respectable hostelry, the Silver Bell.

Here it naturally followed that Ernest should seek the companionship of Rose, and that Mr. Briarton and Frank Ellaby should exchange confidences one with another.

"From what you have told me," said the latter, "I have little doubt, in my own mind, that your Rose and the little girl my dying sister entrusted to my care are one and the same.

"The woman from whom you received her said no idle words when she declared that the child had a great future before her, for I can give her much wealth.

"Though I never liked Calder Dulk's wife, I did not regard her as a criminal. Though, seeing that she robbed me, the news need not surprise me. Odd, indeed, it is that I should once more be thrown into her clutches.

"Someone has truly said that we all live our lives twice over. Certainly, our experiences have a way of repeating themselves in the strangest manner.

"I quite agree with you, that it would be unwise to say anything to the young lady at present touching her real identity, which I fear we shall never discover, unless we can force that woman Dulk to give up the papers she stole from my sister's escritoire.

"If we once catch her, a promise to withdraw my prosecution against her may work wonders."

"I trust that she and her evil companions may soon be brought to justice," said the clergyman. "They might have ruined my friend, Ernest Truelove, who is so honest himself that he suspects no one. I will remain in London a few days, and see how the search progresses."

"Dad," cried Rose, entering the apartment at that moment, "there is to be a splendid concert at St. James's Hall tonight. Do, please, let us go."

"Certainly. We will all go," laughed Frank. "I will send round to the box-office and secure seats at once. Should Blake want us, we can leave word where we are to be found."

The concert-room was crowded, and on leaving it they became involved in the whirl of a fashionable crush.

Frank Ellaby had called for a cab. While they waited for it a rush from behind separated Rose from her friends.

"This way, miss," said a man to her; "the cab is waiting for you."

She followed the fellow in all simplicity, and soon she was sitting inside a soft, delicately-perfumed vehicle, which drove off at a furious rate before she realised what she had done. A lady, beautifully dressed, sat facing her. She smiled kindly on the young and agitated girl.

"There is some mistake. I have lost my friends. Oh, pray forgive me for getting into your carriage instead of into our cab. Please tell your coachman to stop," cried Rose in alarm.

"I saw your mistake, and it amused me," said the lady, "I dearly love a little joke. Tell me where you wish to go to my man shall drive us there."

"But my friends—" Rose commenced.

"You will be home before them, and will have the laugh against them. That is all. They deserve a taste of anxiety for losing you. The Silver Bell Hotel? I know it quite well. My house lies the same way, but it comes first.

"We will pause there for a moment, if you don't mind, and then I will take you to your own people."

The splendour of the equipage in which she found herself, and the aristocratic bearing of the white-haired lady, who patronised her with such an easy grace, were sufficient to lull all suspicion of foul play in Rose's mind.

"Indeed, she felt that she was an intruder there, and she considered her hostess very gracious in treating her with such good humour. They pulled up outside a large but dismal-looking house.

"Here we are at my home," said the lady. "Come in with me, if only for a minute. Nay, I insist. You are too nervous to be left alone. Come! we shall yet reach the Silver Bell before your folks get there."

The door of the building opened, and without hands it seemed. Silently is closed behind them, leaving them in a dark passage.

"Take my hand," said her conductress in a more commanding voice.

"I will lead you to the light?"

Rose began to feel frightened now, but she had no choice but to follow her guide along the black corridor, down a number of steps, then to the still open air, again into another building, and up a high flight of stairs.

"Open for us, Belus—open!" said the woman.

Rose was now conscious that some creature was walking in front of them.

She could hear its breath coming and going quickly, but its footfall made no sound, and she wondered whether it was a monkey or a human being. Suddenly her eyes were blinded by a great flood of light.

She stood in one of the most lavishly-furnished rooms her imagination could conceive.

She saw that "Belus" was a dreadfully attenuated man. His skin was dry and yellow, and his flesh all withered up like that of a mummy, to which he bore a strong resemblance.

The horribleness of his appearance was increased by the fact that he had lost one eye, and one arm was gone.

These injuries were all on his left side, and they suggested that he had at some period of his existence been involved in a terrible accident. "Belus has been with me many years," said the strange lady, "and he is very faithful."

"Unto death," declared the ghastly-looking Belus.

"It is well said," laughed his mistress. "Unto death! Get us coffee," she added.

"Indeed, indeed," protested Rose, "I must not stay. Do, please, let me go to my friends. They will be quite upset at my disappearance."

"We will leave here within ten minutes," said the lady, smilingly. "The coffee will revive you. I shall feel hurt if you do not take it."

It proved a delicious decoction of the glorious Arabian berry, and it was served in tiny gold cups chased in a most elegant way; but it had not the effect of stimulating Rose. On the contrary, it made her so drowsy that in a couple of minutes she was sound asleep on the luxurious sofa on which she had been induced to sit!

Her hostess stood over her, and regarded her prostrate figure with an expression of evil triumph.

"What is this?" asked Belus, creeping to her side, "revenge or merely simply villainy?"

"Greed," answered the woman shortly. "This girl is worth much money to me.

"Hark! That is the duke's knock. Take care he does not enter here. Nor must he know of this girl's presence in this house. The time is not yet ripe for the disclosure I have to make. Go to him. You may tell him that I am here, and would see him on a matter of grave importance.

"Do my bidding well, my faithful Belus, and I will reward thee."

"Yes," muttered the man, as he seemed to melt from the room, "as you did before, with the loss of an arm and an eye. Your rewards are perfect, and so shall be my revenge!"

"Ah! my beautiful Rose," reflected the woman, unable to take her eyes off her prisoner.

"What is to be your fate? Are you destined for an early grave, or will you soon wear one of England's noblest coronets?"

One Thousand Pounds Reward—The Duke of Fenton—A Sudden Death.

"WHERE is Rose?" demanded Ernest, as the three men clustered round the cab. "She was by my side a second ago," said Frank Ellaby.

"It is but this moment that I spoke to her," declared Mr. Briarton. "It is ridiculous to suppose she has lost us."

They looked around in every direction. They waited till the crush had spent itself, and the pavement was pretty clear, and to their confusion they could see nothing of her. They returned to the hall; she was not there.

The neighbourhood was searched, police and cabmen questioned, and they could gain no tidings of the missing lady.

The extraordinary mystery of her disappearance appalled them. It was as though she had been suddenly swept off the face of the earth.

They made haste back to the hotel, hoping against hope, that, by some possibility, she might have reached it first. Only disappointment awaited them.

The clergyman and Ernest Truelove were both plunged into the deepest distress and consternation.

Frank Ellaby, too, was gravely concerned. It seemed absurd that he should no sooner find the girl he had been searching for all these years than he should allow her to be snatched from him again.

"It is past all comprehension," he said, "that with three of us to guard her, she should be taken from us in this miraculous way. It makes one believe in the supernatural. If money will bring her back she will soon be with us again. I will offer a thousand pounds reward for her recovery. The advertisements shall be sent to-night to all the daily papers."

"I thank you heartily for that generous decision," said Ernest, "but we must strain every nerve to find her ourselves."

"And pray fervently to the One above to bless and protect her," said Mr. Briarton.

Before the missives to the newspapers could be dispatched, Sexton Blake called on them to report such progress as he had made in the hunting down of the "Red Lights."

The discovery of the body of a murdered man in the pool by the old mill had made this a police business.

Mr. Blake's efforts were confined solely to the interests of Frank Ellaby, who had now greater reason than ever for desiring to secure Calder Dulk and his desperate wife.

The detective listened to the story of Rose's disappearance with some surprise.

"I can only suppose," he said, "that this is the work of the daring woman who stole the young lady before. How she managed to accomplish her purpose so easily, and in the full blaze of Piccadilly, I do not know.

"Doubtless her object is extortion. She is determined not to let you escape her, Mr. Ellaby. If the young lady is in her power, I can promise you that I will soon bring about her release. Now that I know this woman Dulk, it will not be long before I find her.

"They are an exceedingly slippery gang to deal with. For instance, I have absolute proof that Calder Dulk and Nizza Polti left King's Cross this morning by the North express, which makes its first stoppage at Peterborough.

"I wired to that old cathedral city to have these two people detained until I arrived there, and formally charged them. No one answered their descriptions was to be found in the whole train!

"Indeed, it chanced that there was only one lady 'on board,' and she is the daughter of a well-known clergyman.

"The train goes at a break-neck speed all the way, the guard is certain that no one left it en route, and that Nizza Polti and her male companion were in their carriage when is started from King's Cross. They have managed to do the vanishing trick to perfection."

"If that gang have succeeded in capturing poor Rose, they hold a trump card. I shall not dare to proceed against them for fear of imperilling her life. They are quite capable of using her as a shield to protect them from my vengeance."

It was Ellaby who spoke.

"That is true," Blake allowed ruefully. "But if they escape your active hostility, they have still to reckon with the police.

"The offer of a thousand pounds reward will bring a communication from some of them, I'm sure."

While this conversation was taking place in the Silver Bell Hotel, another, and even more important one, was being carried on in the strange house whither Rose had been so cleverly conveyed.

Madame Dulk had left her beautiful and unconscious prisoner still reclining on the luxurious couch.

Entering another apartment, more superbly furnished than the first, Madame found a tall, stoutly-built, aristocratic gentleman waiting for her.

He had keen, grey eyes, which glittered under his grey, heavy eyebrows. His white hair was clipped short to his military-looking head, and his moustache was well trimmed and intensely black.

"I received your message," he said in a cold haughty tone, "and I have come. What have you to tell me now?"

"Will your Grace not deign to take a seat?" said Madame, humbly. "The missing child is again found. Of course she has grown to be a woman now. She is beautiful, and would ornament the highest station in the land."

"Tut!" he spoke impatiently; "what an old story this is! Woman, if you are in difficulties and want money, why not tell me so, and take you chance whether I give it you or not? Why do you always try to touch my purse by some untruthful story?"

"Never, your Grace, never in my life!" protested Madame. "I have been mistaken before—that is all. I have never wilfully deceived you. This time I have made no error. I have seen the minister who took possession of her when I was in prison. She is with him now.

"But the danger which threatens you is to be found in the fact that the brother of the woman who had her as a baby in Australia is here, and with her. He came over expressly to find her, and to vindicate her rights.

"He is enormously rich, and he will spend all he is worth in striving to establish her true identity. With my assistance he might learn this in half-an-hour.

"Now it is for your Grace's consideration whether you will submit to be compelled by law to accept this young lady as the daughter of your late elder brother, and allow her to take over the estates you now posses.

"You can arrange matters with me so that the proof of Lady Rose Fenton's existence can be for ever destroyed, and she herself be removed to some safe place abroad.

"As she has never known the joys of the position she is legally entitled to, she can never miss them."