RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

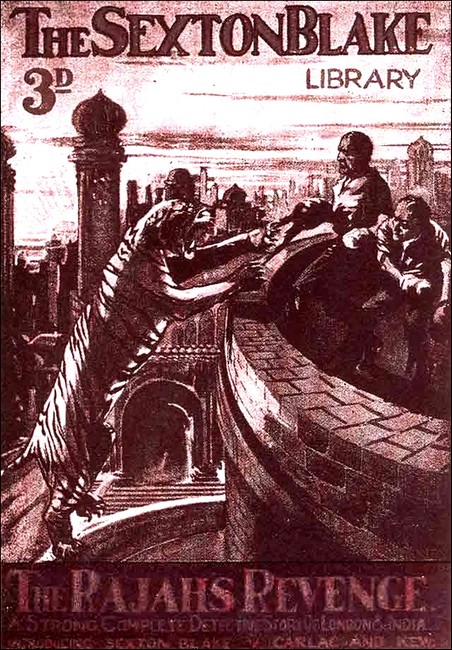

The Sexton Blake Library, December 1915, with "The Rajah's Revenge"

Sexton Blake

In Far Kashopore

KASHOPORE, the capital of Puljara, lies in the angle of a sluggish river. It is one of the chief cities in the North-West of India, and the caravan road that skirts the high walls of the town is always alive with life and movement.

A benign British Government may supply trains, but the native of India, true to his immemorial custom, prefers to travel by road, slowly, easily, with many halts and hindrances. All day long the red dust rises from the wide roadway, all day long the sun blazes through the iridescent haze; and from dawn until dusk, man, woman, child; horse, camel, sheep, and goat, trudge to and fro.

At the great gateway of the town an armed guard is posted. They are quartered in a red stone building inside the gate, and the sentinel on duty is dressed in khaki, with scarlet cuffs and collar. On the great turban is placed the mark of his Highness, the Rajah of Puljara, Mahommed Ali Kahn.

His Highness is an enlightened prince. He stands in favour with Britain, and his city is a model of cleanliness and prosperity. He cannot make his people clean—no power on earth could do that; but he has seen to it that the streets are cleared and that the lazy folk no longer deposit their garbage in that most convenient of places—the next-door neighbour's door!

The palace is a massive structure, standing isolate on the banks of the stream. A white wall divides it from the city, and along this wall are innumerable stalls, littered with commodities of all kinds. It is really the market-place of the town, and the voices of the hucksters and dealers arguing heatedly over the value of their wares resound all day.

About two o'clock on a blazing afternoon, two men emerged from a house close to the palace, and, turning to the left, made their way leisurely along the line of booths, beside the palace wall. They were a badly-assorted couple. Dressed in white drill, and wearing wide pith helmets, their faces, tanned though they were by the sun, were unmistakably European.

A sherbet-seller, from Mirzapore, jerked his thumb at them as they passed.

"The hawk and the bull are out again!" he cried, in his high-pitched vernacular, a cackle of laughter greeting his remark. And, indeed, his simile was well chosen.

One of the men in white, was a huge, broad-shouldered fellow, whose every movement hinted at the giant strength of his limbs. His face beneath the pith helmet might have been carved out of solid granite, so hard and fierce were the jaw and lips. His eyes were set deep in his head, and looked out at the swarming life seething around him, with the grim contempt of a man accustomed to be obeyed.

The other was the exact opposite. Small-limbed, almost dwarfish, with a great head and narrow, sloping shoulders, he tripped along vainly trying to keep in stride with the long, swinging movements of his companion.

But if the thin body was that of a weakling, there was no suggestion of that infirmity in the face. It was like a hawk. Keen, remorseless, thin of lip, long of nose, with small, beady eyes that were ever turning to right and left, restless, never still. The pith helmet did not hide the high-domed forehead, and one could see that the cranium was quite bald, a fact which added to the vulture-like appearance of the thin, cruel face.

A strangely assorted couple, truly, and yet well-matched.

Count Ivor Carlac and Professor Kew!

What had brought them to India? There was no one there to ask that question. India is one of the safest hiding-places in the world, and the unscrupulous European flourishes there, like a bay-tree.

They seemed to be prosperous, too. A diamond flashed on one of Carlac's fingers, for the huge criminal had always a weakness for gems; their clothes were of the finest, and the shopkeepers in the town knew that they had money to spend. They were living with a carpet-merchant, and had engaged a suite of rooms and servants, paying in advance. They had been in Kashopore over a week now, and seemed to be just ordinary sightseers, interested in the wonderful old city, with its long history of siege and battle, rapine and loot.

At the great iron gate that stood in the palace wall, Carlac halted for a moment. Through the magnificent scroll-work of the gate he could see the interior of the outer courtyard, with its tall cypress-trees, and mosaic paths. A trooper of the rajah's bodyguard came clanking to the gateway, a long, curved blade swinging at his supple thigh.

As the man emerged through the gate, Count Carlac hailed him.

"His Excellency, Colonel Bryce," he said, nodding to the palace.

The upright trooper clicked his heels together, and gave a real military salute. He had served his time with the Bengal Lancers, and had not forgotten his English training.

"His Excellency has gone out, to Briuth, on the Cashmere Road, sahib," came the reply, in perfect English. "He does not return until dusk."

A gleam of satisfaction came into Carlac's eyes as he thanked the trooper, and the man passed on.

"You are satisfied now, Kew?"

The little, wizened professor nodded.

"I was never so impetuous as you, my dear Carlac," he returned, in his thin, sibilant tones. "You always take things for granted; I always make sure." The big man laughed.

"Quite right," he returned; "and perhaps it is that which makes us such a suitable couple to run in harness together. Anyhow I vote that we start for the Cashmere Road. We have plenty of time. I know that Bryce and his daughter will not be returning until dusk, but we might as well see that everything is ready for them."

His lips lifted in a hard smile, that found a reflection in his companion's face.

"It is the first step in a big move," said Kew, as he turned away. "We have tackled many things in our time, but this is biggest of them all."

"All the more reason why we should succeed," came the reply. "It is only your small criminal—the area thief and clothes-snatcher—that fills our prisons. The big men keep outside." A shadow crossed Kew's face.

"Not always, Carlac," he returned, with a quick shiver. "We have both known what it is to serve under the broad arrow." They were striding along through the narrow, thronged streets, and presently they reached a portion where a great, black building thrust its forbidding walls up over the barrier of the palace. Kew pointed to the structure.

"And heaven help the man who was put in there," he went on. "English prisons are bad enough, but that one—ugh!"

It was the prison in which the rajah's evildoers were confined. Count Carlac glanced at it, and shrugged his shoulders.

"There is no chance of us finding quarters there," he returned, little dreaming how the future was to make him remember this remark, and to prove its falsity.

It took them the best part of half an hour to elbow their way through the good-natured crowds and emerge through one of the east gateways. The gate opened out on to a broad road, which ran on through a double row of tall trees, past paddy-fields and dykes, rising always until, with one long great sweep, it vanished into the hills beyond, tilting and winding until it struck the cart-road down to the Juman, thence on to Sringar.

They continued along the road, and finally Carlac came to a halt, at the end of the trees.

"What did Chandra Lai say?" he asked, turning to his companion. "Something about the old temple and the rajah's shooting-box, wasn't it?"

"Yes. That was the safest place for us to wait. The attack will be made from a paddy-field close to the temple. We can hear Chandra's signal from the temple."

They had a three-mile walk in front of them, but this was a by-road, and the only living thing they met was a dusty fakir, shuffling along in his rags, with his begging-bowl hanging from his lean waist.

Carlac, inspired by some feeling that he could not quite define, dropped a few pice in the bowl, and the fakir muttered his thanks.

"A gift to fortune—eh?" Kew said, with his dry smile. "It isn't often that you give anything away."

"I want to pull this particular business off," said the bigger rogue. "Don't forget that there are ten lakhs of rupees at the end of it, if we play our parts well." The small eyes of Professor Kew glinted avariciously. "Yes. One hundred thousand pounds," he said slowly, "and in gold!" His thin hands clenched, and he laughed, a thin, cackling sound.

"No awkward notes to be traced from place to place, no bonds or jewels to sell. Just gold. Good, clean, yellow gold. That is the sniff, Carlac."

Dusk saw them moving along the edge of a high growth of canes, and Carlac caught sight of a dark, round dome, showing up the waving heads of the thick plantation. "The temple," he said.

Five minutes later they found themselves entering the dark interior of the ruined place of worship. It was just a little wayside shrine erected to some forgotten god, and as Kew went deeper into it, there came from its depths a sibilant hiss!

The master criminal drew back, smiling, into the shadows. Kew's nerves had always been like steel.

"All right, my friend," he murmured. "We won't disturb you or your brood. You keep inside, and we'll be content with the entrance."

One of the big blocks of masonry that formed the shrine had fallen, and Carlac and Kew seated themselves on the hewn stone. The hush of an Indian summer was brooding over the scene. Now and again there came to their ears the soft rustling of some fugitive breath of wind, running along the tops of the waving cane. Once a night-bird, at least a yard wide from tip to tip, came dipping towards the doorway, only to poise and flutter back as it caught sight of the two motionless men at the entrance.

"A-r-r-r!"

A long call, such as the camel man voices to his team, sounded. Ivor Carlac leaped to his feet. "That's Chandra. They are coming!" Kew also arose.

"Plenty of time yet, my friend," he returned. "We have got to wait until the attack is made. Our noble rescuer part must be done well if we are to make the proper impression."

They plunged into the thick growth on the left, and found a path which led them through the field. There was a faint light from the stars, and Carlac, moving ahead, was able to pick his way.

At last they reached the dry ditch that divided the field from the road, and, dropping into this, Carlac began to follow its tortuous course.

"Help! Help!"

A sweet English voice, lifted in terror, broke the silence.

The wizened professor, staggering along behind his giant companion, chuckled aloud.

"There it goes! All right, my dear Miss Bryce. Be scared to death if you like. All the better for us. We are coming!" A hundred yards was covered at a run, then Carlac leaped out into the road. Ahead of him he saw a mass of indistinct shapes gathering around a couple of plunging horses. "Halt! Halt, there!" he cried, in his deep, commanding voice.

Kew leaped to his side, and together the precious pair darted headlong into the welter of struggling figures. Carlac caught sight of a tall, thin man in khaki, struggling desperately with three white-robed forms.

Like a bull Carlac charged straight into the melee. His powerful hand gripped one of the attackers by the neck, and a jerk saw the native go sprawling on his face into the ditch.

Thud!

Carlac's fist shot out, catching the second man on the jaw. With a howl of pain the man released his hold on Colonel Bryce, and went reeling back to measure his length on the dusty road. "Bravo! Well hit, sir!" the colonel gasped, as he found himself free.

Kew had gone on towards the horses, where the flutter of a white dress told him who the other victim was. A brawny ruffian had wrapped his arms around Muriel Bryce's slender body, and had dragged her clean out of the saddle. Kew with a monkey-like quickness, darted round and leaped full on the fellow's back.

His thin hands, with their hard knuckles, dug into the neck, just where it joined the spine. It is an old trick of the ju-jitsu expert, and by it a man can be rendered senseless. Muriel's captor shrieked aloud at the numbing pressure, then his hold gave, and, with a swing of his body, he released himself from Kew. Kew plunged forward again, but the man, leaping aside, flung himself across the road and vanished, with a rustle, into the field.

It had all happened so swiftly that when Colonel Bryce looked round he found that the swarming band of rascals had vanished, leaving his daughter and the two figures in white drill on the road.

Kew had stepped forward and caught at the horses' bridles, soothing the frightened animals.

"By James, gentlemen, that was what I call a neat little rescue!"

The quiet, cultured voice of the British officer sounded, and Bryce crossed towards his daughter, who caught at him quickly.

"Oh, dad!" she cried, clinging to him for a moment.

All traces of excitement had died away from Bryce. He patted his daughter on the cheek, then turned and smiled through the dusk at the huge figure of Carlac.

"It's all over, my dear," he said, "thanks to the quick intervention of these gentlemen. But, by James, I must admit that the rascals fairly had us!"

Kew came forward leading the horses, and Bryce held out his hand.

"I am extremely obliged to you, sir," the courtly gentleman said. "I had been warned about this attack, but I paid no attention to it. As matters have turned out, the warning was more serious than I thought." Carlac smiled inwardly. It had been part of his plan to warn Bryce of the impending attack. "These hounds were evidently determined to have you, sir," Carlac said.

"Not much doubt about that," Colonel Bryce returned. "But the way you polished them off was a perfect eye-opener. You must be tremendously strong."

He looked admiringly at the great, massive frame of the master-criminal. Carlac had always been proud of his strength, which was far above the ordinary.

"I am glad that I was able to help you, sir," he returned. "And now, as it is all over, perhaps you had better mount. It is getting late."

Bryce started forward, and caught Carlac by the arm.

"My dear fellow, you don't think that I am going to let you go like this," he broke out. Again Carlac was playing a part. He wanted to make it appear as though reward was far from his thoughts. "But it is all over, sir," he said, "and you and your daughter have a long ride in front of you."

"I don't care twopence about that!" the colonel returned. "I insist on knowing your names. Hang it, man, even if you do not think much of what you have done, we have a different opinion! Eh, Muriel?" The slender girl nodded her shapely head.

"I was frightened to death," she admitted. "That brute dragged me clean out of the saddle."

A shudder ran through her frame at the memory of the tenacious arms and the hot breath of the ruffian so close to her face.

"I am glad that we arrived in time, Miss Bryce," Kew put in, in his suave tones. "It was your scream that we heard."

The girl turned round at the mention of her name.

"Then you know my father and I?"

It was a slip, but Kew covered it at once.

"We saw you ride out from the palace this afternoon," he explained. "We are living quite close to the palace, at the house of Saljar Ral, a carpet-importer.

"Ah, I've heard about you!" said Bryce. "You have been living in Kashopore for about a week, I believe? You are Count Kaldross and Doctor Kay?"

There were the names that Kew and his companion had chosen. They were near enough to the real ones to save their owners from making mistakes. "My name is Kay," the wizened man returned, bowing to Muriel.

"Well, look here, doctor!" the colonel went on. "I don't know how long you are going to be in Kashopore, but I insist on you both being my guests until you leave!"

"We are going to England on the twenty-third," said Carlac, with a swift glance through the dusk at his companion.

Colonel Bryce, little dreaming of the trick that was being played on him, rubbed his hands together.

"Nothing could be better," he returned; "for I, too, am going to England on that date! In fact, we're all going—Muriel as well. It is quite a big..." He stopped, as though he had been about to reveal more than he ought to. "Anyhow, I insist on you both coming to see me to-morrow morning!" the colonel went on. "I will leave orders at the main gate of the palace, and you will be brought at once to my quarters. You promise me that?"

He held out his hand to Carlac, and the count shook it.

"If you really insist, colonel," he returned. "But, at the same time, I think that you are making much of nothing. Anything that my friend and I did, we were only too glad to do. There is no need of going any further in the matter."

But before the colonel and his daughter cantered off, they had been assured that the two men would call on the following day, Kew stood in the centre of the roadway watching the horses until the darkness had swallowed them up. Then, turning his head, he glanced into the canes.

"Chandra!"

A rustle, and a stout, squat figure came waddling over the ditch.

"Is the sahib pleased with his servant?" the fat Bengali asked, with a grim chuckle.

"Yes; it was well done. Here!"

There was a chink of gold, and the stout palm closed tightly.

"And there's an extra rupee for the man I attacked," said Kew, in his thin tone. "Tell him to rub oil on his neck to-night, and by the morning the pain of it will have gone." Chandra laughed aloud.

"The sahib has fingers like steel," he said. "The man swears that he felt the life being drawn out from behind his ears, as one draws water from a bag." '"Twas only a Japanese wrestling trick," said Kew, "It was taught me by the emperor's own wrestler, in Tokyo." Chandra vanished into the dark field; then Kew joined Carlac. "Was Chandra satisfied?"

"Yes. I gave him twenty pounds. He and his gang never had so much money in their lives before. They moved along the road at a slow pace, Carlac's brow drawn, his lips set.

"The first move to get at his Highness's war-chest has panned out well enough," he began at last; "but we've a long way to go yet."

"We have prepared our ground," said Kew, "here in Kashopore, and in London, at Downe Square—everything possible has been arranged. It all depends on the rajah now. If he still sticks to his plan—still decides to hand over his war-chest to Colonel Bryce for safe transit from Puljara to London—then we have little to trouble over. The ten lakhs of rupees are as good as ours."

"We've got to get Colonel Bryce to ask us to join his party when he starts," said Carlac.

"I'll bet you that he does that to-morrow! Why shouldn't he?" Kew smiled to himself in the dusk. "We've proved ourselves very useful, even as a bodyguard. No, you need have no fear on that point, Carlac. When his excellency Colonel Bryce, military adviser and British representative at the court of his Highness the Rajah of Puljara, leaves for England on a very important mission, he will have two additional members of his suite—you and I.'"

The lights of the city presently loomed in front of them, and they entered the gateway, a sentinel moving out to open the wide gates. For in Kashopore, in common with many other cities in India, the main gates of the city were still closed from sunset to sunrise.

Under ordinary circumstances Carlac and Kew might have been forced to spend the night in one of the dak-bungalows that are always to be found close to a big city for the use of belated travellers, but this time they were allowed in at once.

"His excellency the colonel-sahib's orders," was the reply which the tall sentinel gave when questioned by Kew.

The wizened man turned and grinned at his companion as they passed on into the narrow thoroughfare.

"There you are!" he said mockingly. "Already you have proofs that our worthy friend the colonel thinks a great deal of us. By to-morrow morning you may rest assured that we will belong to his personal suite."

Carlac smiled at the cold, mocking voice.

"I think you're right, Kew," he returned. "And, by Jove, we must take full advantage of it. We have a clear field, and if we fail it will be our own fault. Within a couple of months from now we ought to be sharing a hundred thousand pounds."

The magnificent gift which the Rajah of Puljara had promised to England, ten lakhs of rupees, had caused no little stir when it was first announced. The rajah himself had arranged that he should hand over the treasure to His Majesty King George, and the Indian potentate was travelling to London to perform that ceremony. It was this news that had first stirred the cupidity of Kew and his companion.

They studied up every detail concerning the gift. They read every report, and discovered the following facts:

The money, in solid gold, was kept in an iron-bound chest in the palace at Kashopore.

The chest itself was a historical one, for it had been presented to his Highness by his people on ascending the throne. Kew, setting to work in his grim way, soon found a photograph of the chest in a local museum, together with an exact description of its measurements. The curator of the museum little dreamed to what use his information concerning the treasure-chest was going to be put. That same night Kew sent off a long letter to a certain address in London, where an antique dealer, a perfect master at the art of faking old furniture lived.

The two scoundrels also discovered that Colonel Bryce, the British representative at Puljara, was a prime favourite with the old rajah, and that the colonel had been commissioned to take charge of all the details concerning the great gift. He had to travel to England with the precious chest, and await the arrival of the rajah, who was due to follow by a later steamer that sailed a week after.

Here then was the best opportunity to steal the chest. A project that fascinated the master intellects of the two criminals. It wanted courage and daring and skill, attributes which both men had to a high degree.

It was Carlac who discovered that Colonel Bryce owned a house in London, in Downe Square. He got the address of the house, and, to add another link to their long chain, another letter was sent off, this time to a certain Flash Harry, one of Carlac's old gang.

The rest of the plot consisted in the two men worming their way into the confidence of the genial colonel, and this, thanks to a very old but useful trick, had now been accomplished.

"We have absolutely nothing to fear," said Kew that evening, as he and Carlac sat in the quietly-furnished room that they had rented in the carpet-dealers's house. "Chandra Lai would never betray us; he would be clapped in the rajah's jail as an accomplice as quick as possible. To-morrow, at the very urgent entreaties of our friend the colonel, we will take up quarters in the palace, and remain there until the party starts for England."

He rubbed his lean hand over his bald skull, grinning the while. Perched on the heap of high cushions, with his thin legs tucked under him and the light from the lamp shining full on his yellow face, he looked more of the bird of prey than ever.

"This is the sort of affair that I delight in," he said. "There are risks attached to it. You and I, Carlac, have to face the powers of two Governments, the British and the Puljara. There is not the slightest doubt but what the treasure will be guarded day and night. He, he! We have our work cut out for us!"

Carlac had flung his huge frame on a low divan and was pulling at a long pipe. He blew a fragrant cloud from his lips before making a reply.

"You seem pleased to find it difficult," he put in, at last. "And I suppose you're right. There is only one thing I hope, and that is that a certain man, whom we both know, is kept out of it." Across Kew's face the shadow of a scowl spread. He leaned forward.

"Why do you talk of that individual?" he asked hoarsely. "We have had quite enough of him in the past!"

"Oh, I don't know," Carlac returned, "the thought just came into my head!"

"Then banish it!" snapped his companion. "That man has been a thing of evil omen to me, and to you. Without his interference we would both have been rich men now. Able to move about the world and enjoy everything that came our way."

He started to his feet suddenly, and raised his clenched fists in the air. The lamp threw his grotesque shape on the dull wall behind him. He looked like some demon from an old-world picture, in his long, loose robes.

"I swear that if Sexton Blake crosses my path this time, I will not rest until one of us goes under," he muttered, his voice thin with suppressed feeling. "Too long he has been like a Nemesis in my path. There must be an end to one of us, and if he intervenes now, let him look out for himself!"

Then, just as suddenly as it had risen, his rage died away, and he was his old, cool, inscrutable self again, smiling out of his lashless eyes at Carlac.

"Sounded frightfully dramatic and all that, I suppose," Kew said; "but I mean it. And now, let's get ready for our visit to-morrow."

He seemed to be assured of his welcome at the palace, for he packed everything in readiness for the move.

And neither he nor Carlac were disappointed. Colonel Bryce met them on the marble steps that led into his private suite, and the colonel's handshake was of the warmest.

"I was afraid that you would not come," he admitted, leading the way down a tapestry-hung corridor and into a spacious, well-lighted room, where at a table a sturdy youngster, in neat-fitting khaki, was seated, hard at work on a heap of documents. "Vernon, here is Count Kaldross and Dr. Kay. They have turned up you see."

Lieutenant Vernon, attache to the colonel, drew his long legs beneath him, and arose to shake hands. He had a keen, bronzed, good-looking face, a typical young officer such as one meets anywhere in clubland.

"Pleased to meet you, gentlemen," he said, revealing a set of white, even teeth; "and I'm jolly glad you've turned up. Miss Bryce was doubtful about it, and it was quite on the cards that I should have to go and hunt for you, although I hadn't the remotest idea where the dickens I could find you."

Carlac was studying the bronzed face, and a slow smile crossed his heavy jowl. Vernon was a member of Colonel Bryce's suite, and was, therefore, a potential enemy.

"I don't think that we have much to fear from you," he decided. "A brainless cub. And all the better for that!"

It is not always advisable to judge a man by his first impressions. Lieutenant Vernon was young and rather dandy in the matter of dress; but he was not altogether without brains, as the future was to prove.

Nothing could exceed the warmth of the welcome that the two arch-scoundrels received. Muriel Bryce was particularly kind to them both, and Vernon, head over heels in love with the beautiful girl, was inclined to scowl a little when he found himself so very much in the background.

It was arranged that Kew and Carlac should take up their residence at the palace, and they did so. And it was also arranged by the colonel that they should travel to England together.

"My dear chap, it is my convenience that I am studying," the colonel admitted. "I might tell you that this journey of mine is going to be a most anxious one."

They were seated at the dinner-table, with cigars and liqueurs. Carlac had cunningly suggested that the presence of his companion and himself might embarrass the travellers.

"In what way, colonel?" Kew's voice was quite steady.

"Well, I'm taking with me a chest with a king's ransom in gold inside it," the colonel returned. "And, 'pon my word, I don't like the job one little bit."

"Colonel Bryce is referring to the rajah's gift to our King," Vernon put in. "I suppose you've heard about that?"

His grey eyes were fixed on Carlac, but that individual was a master of the art of self-control.

"I'm afraid I haven't," he returned. "Kay and I have been in the hills—Tibet and Darjeeling—for the past two months. We were quite out of touch with civilisation."

The colonel arose to his feet.

"Well, if you care to come along with me, I'll show you the thing we've got to travel with. It might interest you." Muriel, who was seated next to Vernon, noted a frown cross the handsome face, as the two strangers arose and followed their host.

"What are you frowning at?" the girl asked, with a quick, roguish laugh. Vernon turned to her.

"The colonel is much too trusting," he said. "Of course, I know that the treasure-chest is safe enough here in Kashopore. No man could get it outside the palace and live to tell the tale. But, later on, it might be different." Muriel laughed.

"Stuff and nonsense!" she said. "I think that you are in a very suspicious mood this evening, Mr. Vernon. You surely don't think that these two men are likely to steal the chest?" "Well, I—I—"

Muriel arose to her feet, her nose in the air.

"I'm surprised at you!" she went on. "After all, these gentlemen saved dad and I, and if that doesn't make them worth cultivating in your eyes, then you don't think very much of—of me!" She was about to hurry away, when Vernon, leaping forward, caught her by the arm.

"You know that I think all the world of you, Muriel," he said, in a deep, passionate voice. "Why do you tease me like this?" The girl looked up into his love-filled eyes, then her own melted. With a quick movement she leaned forward and gave him a butterfly-like kiss.

"I'm not teasing, dear," she said. "Only, I do think you are much too suspicious. I really think that it's this stupid war-chest. I shall be glad when it has been safely handed over to the rajah." Vernon released her, and stepped back a pace.

"Perhaps it is the beastly chest," he returned. "And you are certainly quite right. I, too, will be jolly pleased when it has gone. It's far too heavy a responsibility for my liking."

Colonel Bryce had lead the way down a narrow flight of stairs and into a small, vaulted room. He lighted a lamp, and held it aloft.

"There is the war-chest," he said.

It was a massive, solidly-made receptacle. The carving was deep, and toned with age. Iron bands, riveted through the solid wood, gave it an appearance of strength.

Kew and Carlac stepped forward to examine the chest. Despite the fact that they had nerves like steel, neither could control the swift thrill that ran through their veins.

Here was the very treasure that they had set out to obtain, by foul means or by fair. Locked beneath that heavy lid were piles upon piles of golden coins. A king's ransom!

"You do not seem to take much trouble to guard it, colonel," Carlac said. "I did not notice any sentries."

Colonel Bryce laughed.

"No man in the world could shift that chest from here," he said. "Try and move it." Carlac caught at the stout handle, and put out all his vast strength. The chest did not budge an inch. "Gold is heavy, you see," their host went on. "It takes four men to shift it. Besides, there is not a soul in Puljara would dare even to lay his finger on that chest. It is the rajah's property, and sacred. It means death to anyone who touches it without his permission."

The two rogues followed him back into the dining-room. Kew was quiet and thoughtful, leaving the conversation to his companion.

For as they stood over the chest there had come to the wizened professor a foreboding that he could not define. The breath of some far-off danger, chilling his soul. "Death to anyone who touches it!"

That black prison that they had passed in the morning. Would it one day open its gates to swallow—

With an effort he drew his thoughts back, and into his beady eyes there came the old look of greed and avariciousness. These two passions that had turned him from a skilled, clever physician, one of the greatest surgeons that the world had ever known, into a hunted criminal, with every man's hand against him.

"I'll risk it," he thought, his vulture face hard and set. "It is a far cry from London to Kashopore, and the rajah cannot reach me in England."

Was he right or wrong?

Tinker and Muriel

"THAT'S the worst of a great, hulking dog like you, Pedro. You cannot be taken out in the daytime, like an ordinary pup! You're too big and hefty, and people want to make a fuss of you."

Tinker, his hand tight on the strong leather leash that was attached to the collar of the great bloodhound, Pedro, voiced his grumble in what was rather a kindly tone.

As a matter of fact, the young detective was only too glad to snatch every opportunity he could get to take the big hound out for a stroll. Pedro, under ordinary circumstances, usually lived in the East End, for there was no convenience for him at Baker Street. But Tinker was constantly bringing the dog to the chambers, and there it remained until the old landlady fired up and insisted on it being taken back to its quarters.

"She hasn't grumbled yet, old man," the youngster went on; "but that's because you're getting jolly artful. Who taught you to stow yourself away below my bed every time the old dear comes upstairs—eh?"

He laughed as he spoke, and Pedro, turning his huge head, gave a wave of his tail that was as eloquent as speech.

They had turned westward, through the maze of streets that lie between Baker Street and Edgware Road. Crossing that busy thoroughfare, Tinker went on down a broad, quiet street, and presently turned into a small square. He was heading for Hyde Park, but was shaping a rather erratic course. He had nothing much to do, and London, in the half-gloom that the fear of Zeppelins had necessitated, had its fascination.

"Well, if that isn't most annoying!"

Tinker was almost within touching distance of the stooping figure before he realised that it really was a human being. The voice was a charming silvery one, and Tinker came to a halt. As he did so the girl looked up, and gave vent to a little gasp as she saw the slender youngster with the huge hound by his side.

"Goodness, how you frightened me!" she gasped, rising to her feet.

It was quite thirty yards to the nearest lamp post, but there was just sufficient light to allow Tinker to see that the face turned towards him was a charming one, and that the girl was in evening dress, without a hat. A soft cloak had slipped from one smooth, white shoulder, and she drew it into its place again, at the same time running a small hand through her hair.

"I'm very sorry, miss," Tinker began, raising his hat.

"Oh, that's quite all right!" came the laughing reply. "But—well, it was really that great dog with its big eyes that made me jump!"

"Have you—have you lost anything?"

"Yes; and I'll never be able to find it, either. It is a jewelled comb."

"Where did you lose it?"

The girl waved her hand vaguely.

"Somewhere about here," she returned. "I just came out for a breath of fresh air, and walked across to the gardens. I did not notice that I had dropped the comb until I came back here." She looked down at the pavement.

"It is one of a set, and very valuable. An Indian rajah made me a present of them on my last birthday. I believe they are worth about sixty pounds each!"

"Phew! You don't want to lose a thing worth that amount, miss!"

She seemed a sweet, friendly woman. She chatted away in a bright manner, and Tinker decided that she was worth helping. He knew that there would be very small chance of her getting her ornament back again if she waited until the morning. Your London milkman, dustman, and newspaper boy are as honest as the day, but there are others less honest who haunt the better-class thoroughfares in the small hours—vagrant prowlers, like the carrion dogs of the Oriental cities, seeking whatsoever chance may throw in their way, from gutter and drain.

"I suppose it isn't really worth while searching," she went on, with a little sorrowful shrug of her shoulders. "I'm sure that no human being could find my comb on a dark night like this."

Tinker smiled, and his hand slipped down the leash, loosening it.

"You're quite right, miss," he returned, "no human being could find your comb, but there's an old fellow here who has something better to guide him than eyes." The girl looked round as though expecting to see a third person. Tinker smothered a laugh. "I mean the dog, miss," he said, "he is a bloodhound, the wisest and best in the world." His companion turned towards him with a quick swing.

"That dear old doggie?" she said. "Do you really mean to say that he can find—"

"Give me one of your combs," said Tinker.

The girl handed him the jewelled ornament out of her hair without a moment's hesitation. It was a little proof of instinctive trust, which made Tinker all the more eager to help. "Here, Pedro!" he said. The hound snuffled at the comb. "Oh, poor thing! How can you expect him to find it?"

"Seek!"

It was certainly a hard task. As a rule Pedro's work was the tracing of human beings. Tinker stepped back, watching the hound. It was a real test, and his pride in the wonderful sagacity of his beloved companion would not dare him to think of defeat.

"Seek, old man—seek!"

There came from the hound a half impatient snuffle. Pedro glanced first at Tinker, then at the intent, eager girl by his side. Then the big hound stepped out on the roadway, and his muzzle nosed at something on the ground.

With a quick laugh and a cry of delight, the girl darted towards the dog, stooped, and lifted the object.

"He—he thinks we were both such fools!" she cried, tucking one slender arm round Pedro's massive throat. "And so we were, you dear thing!"

"Did he find it?" Tinker asked.

The girl held up her hand; the comb was sending a red, dull glow from between her fingers.

"Of course he did! Don't you see what it was? These great big eyes of his had found it long ago, and he was just thinking to himself how foolish we both were."

She made a pretty picture, stooping there in the shadows, one arm round the hound's neck, her small mouth open, her white teeth gleaming.

"Good old Pedro!" said Tinker.

He was genuinely delighted with the hound, and as the girl arose, he reached out and replaced the leash.

"But you mustn't go like that!" his companion said. "I—I am really very much obliged, and—and—"

She was just about to offer some sort of reward, but the movement that Tinker made brought her to a halt. She flushed in the darkness, then, with a laugh, held out her hand.

"My name is Muriel Bryce," she said; "I live at number five. Won't you please give me your name? I should love to come and see this dear, clever dog some time."

Tinker hesitated for a moment, then gave his name and address.

"I'm afraid that you won't have much chance of seeing Pedro there, however," he added; "it is only now and again that we have him with us."

"Well, I'll risk it, and—and thank you so much again. Good-night!"

Muriel and Tinker shook hands; then, after a pat on the hound's head, the slender figure tripped off down the pavement and turned into the porch of a small house. She waved to Tinker as she vanished, and the lad raised his cap.

"Now that is what I call a real English lady, Pedro," Tinker murmured, as he resumed his walk—"no side, no swank—just real good breeding!"

At the corner of the square he glanced up and read the name.

"Downe Square—never heard of it before."

He saw now that it was a very tiny oasis of a place, with not more than half-a-dozen houses on each side. Bayswater and Mayfair are dotted with just such similar havens of quiet.

Tinker went on down the street that led from the square, and presently there turned the corner a slow-moving taxi. The driver was keeping close to the kerb, and was looking up at the houses as he moved along.

Catching sight of Tinker and the dog, the driver slipped his clutch for a moment.

"Where's Downe Square, mister?" he asked.

Before Tinker could reply an extraordinary thing happened. The door furthest away from the pavement opened, and a figure in a dark cloak leaped out, swinging towards the driver.

"Keep your mouth shut, you fool!" a harsh voice rasped. "If you don't know the way, keep quiet!"

Tinker saw the cloaked figure lean forward and knock the driver's foot aside, so that the spinning clutch was re-engaged and the taxi shot forward.

"Here, what the blazes—"

There was a jar and a crash, and the driver took control of his vehicle again. The cab stopped and the driver, infuriated at this high-handed proceeding, leaped from his seat. "Yer might have bust the blinkin' keb up!" he bellowed. "Wot do yer mean by it, hey?"

Tinker and Pedro stood on the edge of the kerb to watch the scene. The driver, obviously enraged, danced up to his passenger, his fists clenched.

"Come on, yer monkey-faced skunk!" he bawled. "I'll giver yer, interferin' with my—"

He never completed his remark. As he rushed at the cloaked form an arm was extended, and Tinker heard a faint coughing sound. Chough!

There was no flash, no report, but the driver, as though struck by some deadly missile, threw up his hands and fell flat on his back in the middle of the road. The cloaked figure, wheeling round, without as much as another glance at the heap at his feet, sped off up the street and vanished.

It was only then that Tinker really moved in the matter. Pedro, for some unaccountable reason, had commence to strain and whimper at his leash.

"All right, old man," Tinker murmured. "I don't suppose that the driver's very much hurt. Probably a punch in the jaw, although neither you nor I saw the blow. He stepped out towards the man lying in the road.

"Come along, old chap!" said Tinker, stooping forward. "You can't be so badly hurt as—"

He touched the driver, and at the pressure of his fingers the shoulder moved round and the head fell back. Tinker peered for a moment into the upturned face, with its fixed, dull eyes and drawn back lips. A cry of utter amazement broke from the young assistant. "Good heavens, he is dead!"

There was no mistake about it. The unfortunate man had been terribly punished for his brief and natural anger. The discovery shocked Tinker, and for a moment he stood irresolute; then, realising that there was only one course to pursue, he drew a police-whistle from his pocket and sent a shrill summons through the deserted streets.

Pheep! Pheep!

An answering call came, and two minutes later a stalwart constable came upon the scene. A half-a-dozen words from Tinker gave the man the bare details of the affair, and also the identity of the speaker. "I've seen you often, Mr. Tinker," the constable said; "and, anyhow, I recognise your dog."

He pointed to Pedro. The hound was still betraying a curious impatience, and his head was turned always in the direction of the square—the direction that the mysterious fare had taken.

"Not much good of you trying to follow him," Tinker said; "you haven't even got his scent."

Yet Pedro still strained and whimpered, and it was only when Tinker, at the suggestion of the constable, took the dead man's place at the wheel of the cab, that the hound gave up his importunities. The driver had been lifted into the vehicle, and, with the constable inside with his gruesome charge and Pedro on the step beside him, Tinker drove the taxi to St. Hugon's Hospital.

"I should say that he died of suffocation." The house-surgeon gave his verdict in the uncertain voice of a man in doubt. "Yet, on your story, it does not seem possible."

Tinker and the constable, with an inspector who had come from the nearest police-station, were standing in the surgeon's room. The brief examination of the body had just concluded.

"It beats me!" the young detective returned. "As far as I could see, there wasn't a blow struck. The other man simply stretched out his hand and there was a soft sort of cough, and the driver went down like a nine-pin!"

There was nothing further for him to do at the hospital, and he and the inspector went out together. The officer was obviously ill at ease.

"A nice sort of case to have to tackle," he grumbled. "No blow struck, the surgeon not really sure how the poor beggar came by his end, and—and not so much as a clue to go on to find the man that did it."

"Except that he had asked the driver to take him to Downe Square," Tinker put in. The inspector shook his head.

"We're not even sure of that," he returned. "The driver asked you for Downe Square, but how are we to know that his fare was actually going there? It might have been one of the streets off it, or the driver might even have been looking for a short cut."

There was certainly a possibility that the inspector's gloomy diagnosis of the case was correct.

"And to-morrow the papers will be full of it. 'Another Crime of the Darkness. What are our police doing?' That's the sort of headline they'll put up, I'll bet!"

Despite the tragedy that he had witnessed, Tinker could not help smiling at the tone of voice.

"Anyhow, it is not your fault," he said, consolingly. "No man could have foreseen what happened."

Yet when he parted with the inspector Tinker felt that in someway or other he had been the indirect cause of the crime. He had no reason to apply to justify this assumption, yet deep in his heart the feeling arose and grew that it was the fact of the driver stopping to ask him the way that had resulted in his death.

Then a sudden thought flashed into his mind, and he came to a halt.

"By Jove! It is possible that the murderer recognised me?"

He remembered that he had been standing under a lamp-post when the taxi drew up. Anyone inside the vehicle could easily have seen his face.

Then Pedro's strange behaviour formed another link. Had the hound, with its deeper sagacity, recognised some old enemy?

Tinker looked down at the big hound with a half-rueful expression on his face.

"By jiminy, my son, I'm beginning to think that you and I play the wrong roles. It ought to be you that had charge of the leash, and I ought to be wearing that collar. You've proved to-night once that your eyes were keener than mine—and I shouldn't be surprised if you were right the second time."

It was too late to do anything now, however. The criminal, stranger or ancient enemy, had made good his escape. It would have been worse than useless to attempt to trace him, even with the aid of the hound. Pedro might have been able to follow the man had they started at once, but now it would be necessary to get some article of clothing belonging to the unknown—and that was an impossibility.

"No; you've got clear away, whoever you are," Tinker muttered. "And the only question that concerns me now is: why did you want to keep the address that you were going to away from me?"

He could find no answer to that problem then, and indeed, clever though the youngster was, he was not to be blamed for that.

Tinker could not know that it was the sight of his keen, well-remembered face, and more particularly the sinewy shape of the great bloodhound, that had aroused a sudden panic of fear in the heart of a rogue.

Professor Kew's iron nerve had deserted him for the moment—for it was he who was seated in the vehicle.

He had come back from a momentous visit. Earlier that afternoon he had gone to the address of the antique-dealer, and had been shown the result of his letter.

A great chest, the exact counterpart—carrying, iron bands, everything—of that which stood in the strong room in No. 5, Downe Square!

A taxicab, had been chartered, and Kew had seen the chest safely handed over to a lynx-eyed individual, who had been introduced to him by Carlac as "Flash" Harry.

It was the initial move of their great scheme in London, and the professor had been weighing over the various details on his return journey to Downe Square. Then, as though by sheer chance, he had caught sight of the lad and dog—the loyal servants of the only man in the world that Kew hated and feared.

And what followed had been the result of that panic. His death-tube that he always carried had not failed him, and he had escaped.

But he was in a welter of fear as he entered the quiet home of the man he intended to victimise, and he made for his bedroom at once, to pace up and down, hands behind back, his vulture head on his breast.

He had killed a man, but that thought did not trouble him. It was the appearance of Tinker so close to Downe Square that kept the brooding man, pacing up and down long into the night.

At the Antique Dealer's

"HE was such a hard-workin' chap, sir"—the tearful voice had a subdued pathos in it—"and he didn't have an enemy in the world. Heaven knows what me and the kiddies are going to do now."

Sexton Blake glanced compassionately at the drab figure seated on the edge of one of the comfortable chairs in his consulting-room. Tinker, always nervous in front of a grief-stricken woman, cast a quick, appealing look at his master.

When "Mrs. Todd" had been announced by the landlady, neither Blake nor his assistant had any idea who she was. But her opening remarks soon told Tinker that it was his adventure of the previous evening that had brought her here. She was the wife of the dead taxi-driver, and it appeared that the police-inspector had sent her on to Baker Street.

"Why was he killed?" the woman asked again, turning a tear-stained face to Blake. "He never 'armed anyone in his life. I know that my Joe was a bit hasty-tempered-like, but he never did no harm to anyone."

Sexton Blake was a busy man, and the case of the murdered taxi-driver was hardly one of the type that he cared to tackle. It was one of those street crimes that the police make their province, and under ordinary circumstances Blake would have taken no part in the investigations.

But the appeal of the poor and destitute class always made a big impression on the great detective's charity. And this forlorn creature, in her tears and misery, had found the best way of appealing to him for help.

Half an hour later, when he dismissed her, there was a shadow of hope in her faded eyes. Tinker saw his master slip something into the work-worn hand, and heard the woman's murmur of thanks. When Blake came back into the consulting-room, he eyed Tinker with the ghost of a smile on his finely-chiselled lips.

"So your little stroll last night had a sequel to it—eh?"

Tinker flushed.

"I didn't want to trouble you, guv'nor," he explained. "I knew that you were busy enough as it was. Besides, there was really nothing to be done."

"That was quite right, old chap," said Blake; "but this poor woman puts a different complexion on the affair. By a foul deed she has been robbed of the bread-winner of her little home. That is a far greater tragedy in the lives of the poor than of the well-to-do. We must try and help her, Tinker."

He glanced at the notes he had taken. The woman lived in Whitechapel, and the cab was garaged close by. It was her husband's own private property, having been bought by instalments.

Blake had taken the number of the vehicle, and also the place that it usually stood when out for hire.

"It's not going to be an easy task," he said; "but there is just a remote chance of us tracing the taxi's movements yesterday, Anyhow, we will have a try."

It was a hard task.

They found out that Todd had not been seen on his usual stand on the previous day. Inquiries at the garage, however, gave Blake the information that Todd had been hired for a wedding, that had kept him busy for the whole of the afternoon. The wedding-party had gone to an hotel, and finally Todd and two other drivers had taken their guests to their respective homes.

"The job must have kept him on the go until about eight o'clock, sir," the garage-owner said; "then, I suppose he went on to try and pick up a casual or two. But, maybe, Steve Jones could help you to find out what happened afterwards. He was with Todd at the wedding-party."

Blake got the address of Steve, and finally ran his man to earth, in a little flat in a high tenement building. Steve had evidently not yet turned out for his usual day's work. He was a short, thick-set man, and seemed inclined to talk.

Blake's news concerning Todd's death seemed to shock his listener. After giving Jones a brief account of the tragedy, the detective began to question him.

"Yes, that's right," said Steve; "me and Todd was both at the wedding. And, by jiminy, I thought that they was never going to finish. It was arter six o'clock before they left the hotel—and some of 'em wasn't half lively, either."

"Where did you go?"

"Oh, Todd and me drove off together," the driver explained. "We got our money, and then, as we was both jolly hungry, we went down to the shelter in Shapper Street, and had a bite. While we was there a 'phone message came for a taxi, and I went off first. Todd thought there might be a chance of picking up something and he followed me."

"Did you see him again?"

Steve was silent for a moment.

"I couldn't swear to it, you see, mister," he said at last; "and, as this might mean a police court job, I likes to be sure." The great detective smiled at the man's caution.

"You are quite right," he said; "it is always best to be careful. Still you are not giving evidence on oath now, and if there is any little point that you think might help, let me have it."

"Well, sir, it's like this. I stopped at the address where the 'phone message came from, and picked up my fares. They were a long time about it, and they'd got some heavy luggage with them. But when I turned to leave, I did think that I saw Todd's cab. It was crawling down the pavement towards me, and I gave him a wave of the hand. But there was a gent, signalling at the same time, and, if it really were Todd, he didn't see me. You know, it's pretty dark in London at night-time.

"Where did you pick up your fares?"

"Anton's, 30a, Luer Road. It's an antique furniture shop."

Blake nodded his head. "I know Anton," he said.

"He's a queer chap, that," Jones put in; "but it weren't him that I took in my cab. They was customers of his, I reckon. They'd bought an old box, or something, from him. Blimey! It was heavy! I'd to get down and give them a hand to fix it on the luggage-step."

Small, almost trivial, details, these. Yet Blake's vast brain treasured them all. It is only by a system of this kind that, bit by bit, scrap by scrap, the great mysteries of the world are solved. "And how far away was the cab which you thought might have been Todd's?"

"Just underneath the next lamp-post," said Jones. "Of course, mister, I ain't swearing that it was his—only at the back o' my mind I do think that it was."

"You would make a very good witness, Jones," Blake said quietly, "and one that could be relied upon." The taxi-driver stood up.

"I'd like to do something to 'elp, sir," he said. "Todd was one of the best, he was. It's a blinkin' shame that he should be murdered. He never did anyone any harm. Maybe a bit hot-tempered, but that's nothing."

Tinker had waited at the entrance to the building, and when Blake appeared, the young assistant glanced keenly at his master.

"Any luck, guv'nor."

"I shouldn't like to venture an opinion just yet, Tinker," Blake returned, "but we have a little line to work on now." This time it was to Anton's place that Blake journeyed, by taxi. As he entered the frowsy, dingy shop, the thin, lean-faced proprietor came forward. Anton recognised Blake at once, and held out his hand, the usual inscrutable smile on his lips. "And how is Mr. Blake?"

Blake returned the greeting, and looked around him. No one had ever been able to point an accusing finger at Lew Anton. His business was at least genuine. He was a maker of false antiques. His little workshop at the back of the premises had seen more spurious Chippendale and Jacobean furniture turned out to deceive even the connoisseur than any other maker in London.

"Nothing in the almost antique line for you this morning, I suppose?" Anton went on, rubbing his long, clever fingers together. They were stained and hacked by much handling of tools and polishes, for Anton did most of his better-class work himself.

"No, Anton, I'm not on the buy. I want a little information." The antique dealer pursed his lips.

"You know my unvarying rule, Mr. Blake. A customer's business with me is a sacred trust."

"That's all right, old chap!" laughed Blake, who understood the man perfectly. "I'm not going to find out whether somebody's cherished treasures are really genuine, or samples of your work." Anton looked relieved, and half apologised. "It wouldn't be fair to them, you know," he explained.

"What I want to find out is the movements of a certain taxi-driver," said Blake. "He was observed to pick up a fare close to your shop, and I was hoping that you might have noted it."

"That's a difficult question," the dealer murmured. "When is it supposed to have happened?"

"Last night. Just about the same time as a customer of yours 'phoned for a taxi to take away a box from here."

"Ah, yes! That was between eight and nine, I should think. I couldn't swear to the time, of course."

"That would be about the time."

Blake briefly repeated the details what he had had from Jones. Anton listened quietly, then shook his head.

"I'd like to help you, but I'm afraid I cannot," he said at last, "for, as a matter of fact, I did not go out of my shop. The—the article that was being taken away was very weighty, and I had to send my assistant along with the customer to help carry it to the taxi."

"I suppose your customer could not help me?"

The antique-faker smiled—a wintry smile.

"Now, of course, you are stepping on forbidden ground," he put in. "I dare not give you my customer's address!" Blake was well aware of the old fellow's prejudices, and the detective had to confess that Anton's attitude was the correct one.

No individual cares to have it known that his cherished antiques are really only clever fakes, and the mere fact of Anton supplying one with articles was quite sufficient to label them as fake. "That makes it rather awkward, Anton," said Blake, "for I am very anxious to trace this taxi." The lean proprietor shrugged his shoulders.

"I don't think that my customer could help you, in any case," he went on. "If you inquire, you will find that the chest"—he mentioned the article almost before he was aware of what he said—"has been taken to Paddington Station—left-luggage office. I believe it is intended to travel to the East."

That information certainly settled matters so far as that particular channel of information was concerned. Blake, clever though he was, could hardly be expected to trace an unknown proprietor of a left-luggage article through London!

"That has settled it!" the detective agreed, revealing no trace of disappointment on his face. "And now, have you anything to show me? I have five or six minutes to spare."

Anton's intellectual face lighted up; then a quick shadow of disappointment crossed it.

Blake had often visited the little shop, and his keen knowledge of antiques had made Anton relish his opinion.

"If you had only come along here yesterday, Mr. Blake," he said, "I would have shown you something worth while?"

He drew himself up, all the pride of the artist shimmering in his faded eyes.

"A masterpiece!" he said. "It is the best thing I have ever done! I would have defied even the great Hindu artist himself, who designed the original, to have made a more perfect duplicate!"

"But if it's gone, what's the use of arousing my desire to see it?" Blake laughed.

And then the pride of the artist conquered for a brief moment the caution of the man of business.

"After all, I don't suppose that there can be much harm!" Anton muttered, half to himself. "The chest is going back to India—probably on its way there now!"

He had no reason to think otherwise. Professor Kew, who was just a mere customer so far as Anton was concerned, had been cunning enough to tell the dealer that his work was to be sent out to India for comparison with the original. Kew had taken this course in order to arouse the professional pride of his dupe. He had been successful, for Anton's work on the chest was a masterpiece of elaborate and careful copying; but by the false statement, Kew was to lay himself open to future discovery.

"Yes, I'll show you the photographs."

He slid behind the counter, and returned presently with a sheaf of faded photographs. They were of the chest, and gave views of each carved side and top. Dim though the were, Blake could pick out the exquisite carvings and tracery. "And you really made a copy of this?" The face of the dealer flushed with pride.

"I was at it, day and night, for the best part of three months," he said, "and I give you my professional word that in every detail—line for line, grain, and finish—my duplicate equals the original!"

"Then, by Jove, I should have liked to see it!" said Blake. "It looks like one of those old Indian chests that one rajah sent to another in the old fighting days either as a war indemnity or as a peace offering."

"I don't know its history," said Anton, truthfully enough. "I was only interersted in the work."

Blake and Tinker spent half-an-hour in the old fellow's shop, and Anton came to the door to see them off.

"It's been very interesting, guv'nor," Tinker said, in his dry way, "but we haven't got much forra'der!"

"That's true!" the great detective returned. "And yet, I don't know! I am inclined to trust to the word of Jones. He is a cautious sort, and is not likely to make a mistake."

He glanced at his assistant.

"Anton is as close as an oyster, but both you and I know that some of his customers are very queer fish. I am half-inclined to think that the unknown fare who was picked up by Todd in Luer Road was the same man that murdered him."

"But it was much later than that when I saw the taxi at Downe Square, guv'nor.

"Yes, that's so. But we won't theorise any longer. I'm going to make another effort, and if this is unsuccessful I will confess myself at fault." Tinker placed his hand over his waistcoat.

"I could make an effort on a decent steak, guv'nor!" he said, and his lugubrious tone told Blake that he meant it.

It was now well on in the afternoon, and they had breakfasted early.

They turned into a restaurant, and had a meal; then Blake chartered another taxi.

"Paddington!" he said to the driver.

Tinker's eyes brightened as he caught the word.

"You think that—"

"I'm not going to think anything!" came the quiet reply. "I'm just experimenting."

An hour later, however, Tinker had proofs that the unerring instinct of his master had not been at fault. They traced the chest, to find that it had been left in the luggage department only a very short time, the owner returning an hour or so later and removing it. The porter, who assisted in the task, gave Blake a description of the two individuals who had claimed the weighty object.

"One of them was a big, burly gent,—looked like a Colonial—and the other was a tall and rather flashily dressed." A very meagre description, and neither of them tallying with Tinker's brief memory of the under-sized man in the long cloak.

The chest had been placed into a hooded cart, and the porter had not noted any name on the vehicle. And that was all they could discover about the chest.

But outside the station Blake found an intelligent railway policeman, who filled in a great gap.

He had seen Todd and his taxi, and had observed the cloaked man alight. He noted this particularly, because the cloaked man had ordered the driver to wait for him. The stranger had gone into the station, and had remained there for about half an hour. He had reappeared at last in company with a burly man, who had evidently entered the station by the Underground. The two men waited until a hooded cart had entered the covered portion of the station; then the cloaked figure had gone back into his taxi alone.

From the policeman's description, there was no doubt but that the man who had spoken to the unknown murderer was the same as had gone off with the spurious chest.

"And that is as far as we can go just now, Tinker," Blake explained, as they left the station. "You see, one of my theories was correct. The man who waited at the lamp-post outside Anton's shop was interested in the removal of the chest. We have proved that conclusively."

Tinker nodded.

"It's been a hot job, guv'nor," the lad said admiringly. "And it looks so blinkin' simple now it's been done!" Blake laughed.

"The whole art of following up clues depends on one's ability to eliminate the unnecessary, old chap," he explained. "I'm not going to theorise, and we must just accept what we have actually found. Todd, driving his cab, left Paddington at an hour that would just give him time to reach Downe Square about the moment that you were there. We have filled in all his day for him, and by doing so we have established one great fact—that is, that the man who engaged him in Luer Road was the actual murderer."

"That was the point, guv'nor," the quick-witted assistant agreed, "for, of course, Todd might have picked up half a dozen fares from the time Jones saw him last until I witnessed the crime."

They had both spent a thoroughly fatiguing day, and were glad to make their way back to Baker Street. A telephone message was waiting for Tinker, asking him to ring up the police-station. He did so, and heard the inspector's report.

"Nothing doing, guv'nor," the lad said, as he replaced the receiver. "They've been all round Downe Square and the neighbourhood, but no one seems to be able to help them. The inspector is inclined to think that it wasn't Downe Square that the taxi was making for, but some street beyond it. Perhaps he is right, you know, for the driver didn't ask for a number—only for the square itself?'

"That's a rock that we might very likely split on," said Blake. "However we'll see! The inspector is entitled to his own opinion, and certainly he ought to know the type of people who live in that neighbourhood."

A high tea was waiting for them, with fresh buttered toast and the scones that, on special occasions, the landlady condescended to bake for them. Tinker had a wolfish appetite, and made a great meal. Half-way through it, the door of the dining-room was pushed aside, and Pedro, yawning, came into the room, to lay his great head on Blake's knee and wave his strong tail.

"Hallo, you rascal!" Blake said, patting the sage head. "So you haven't been banished yet? Better lie low, then!" The entry of Pedro aroused an almost forgotten memory in Tinker's mind.

"I can find a good home for him, guv'nor," he announced with a grin, for he knew that Blake would not part with Pedro for all the gold in the world. "Indeed?"

"Yes, and, by jiminy, it's at Downe Square, too!" Blake looked up.

"It seems to me as though that square is bulking very large in your life, old chap."

"I'd forgotten all about Pedro," Tinker admitted. "The other affair wiped it clean away."

He gave his master an account of the little adventure in the gloomy square and the clever way in which Pedro had found the jewelled ornament.

"And the young lady said that she was coming round here to see old Pedro again!" Tinker grinned. "I'd like to see our old dame's face when she does come to the door and asks about 'that dratted dog'!"

"I'm afraid Miss Bryce will be doomed to disappointment unless she hurries up!" was Blake's remark. "And, by the way, her name sounds rather familiar. Do you know anything about her?"

"Not a word except that she's every inch a lady!" said Tinker gallantly. "And she wears wonderful combs—worth fifty pounds each, and were given to her as a birthday present from a rajah."

He heard his master give a quick breath, and looked. Blake's face had changed completely—the lines of deep thought about the eyes were plainly visible, the lips were set, and the whole countenance was set and grim.

"A birthday present from a rajah! And she lives in Downe Square!"

He rose abruptly from his chair and went out of the dining-room. Tinker heard the door of the study close, then quiet footfalls sounded. The lad reached out and patted Pedro.

"That's done it, old man," he said; "somehow or other the guv'nor's got his thinking cap on, and that means you and I will have to amuse ourselves for the rest of the evening." He knew that it was his remark that had roused some quick idea in the master brain of the man he admired. Tinker, shrewd and keen-witted, tried to discover what it was, but he failed.

"Can't be done," he muttered, pushing his chair back. "I am a jolly clever young man, but when the guv'nor get busy, you can push me back in among the 'also tried's,' Pedro. But I'll bet that whatever it is, there's nothing against the little lady you and I met last night. She was just a peach and a picture, and if I weren't a pal of yours, Pedro, I'd be jealous. For she certainly didn't put her arm round my neck, nor—nor kiss me under the ear!"

The Theft of the War Chest

In one of the rooms on the second floor of No. 4, Downe Square, there had gathered three men—Professor Kew, Count Ivor Carlac, and the third, an overdressed, sleek rascal, known to his associates as Flash Harry.

The house, situated next to No. 5, had long stood vacant, and the agents had only been too glad to let it on a short lease. Flash Harry, representing himself as the confidential secretary to a wealthy man who desired to keep his name out of the affair, had told the agents a very plausible story. He had made out that the house was to be used as a nursing home for wounded and convalescent colonials, hinting that his employer was a rich Canadian.

The first three months rent had been paid in advance, and a number of workmen had been engaged on the place. Carpenters and plasterers were constantly in and out of the house, lending colour to Flash Harry's story.

He himself furnished a couple of rooms and gave out that he would take up residence there as soon as the alterations were completed.

The local firm of builders who had undertaken the work of altering the house little dreamed that their legitimate business was serving to cover an elaborate fraud.

None of the neighbours thought that there was anything wrong when they heard the sound of hammer and chisel going long into the night. It was known that the work was being pushed forward at express speed so that the place might be ready for its future inmates as soon as possible.

Kew's active brain had organised the whole affair, and now he was there to make his final arrangements.

"I don't see what you've got to worry about, gents," Flash Harry commented: "everything has gone just like clockwork. I've had the grate and wall pierced, and there's a gap big enough for four men to walk through into the room next door. And the job has been done by my own pals—who daren't give me away."

He crossed to the black marble mantelpiece that looked solid enough, in all conscience, and tapped it.

"A fine piece of work," he grinned, "although I say it who shouldn't."

Carlac glanced across at him, then looked at Kew.

"I agree with you, Harry," the burly criminal returned; "you have done extraordinarily well. Our friend, however, seems to have developed nerves—and it's the first time I've ever known him to do the like."

Kew was seated on the edge of a chair, his shrivelled figure curled up in its usual bird-like pose. The hawk face lifted, and the beady eyes turned on Carlac.

"I have developed nerves—but that does not mean that I am afraid." he returned, in his clear thin tones. "It only means that we have to be little more cautious."

"But we've been cautious enough, haven't we?" Flash Harry commented. "Take that old chest, for instance; it came in here in full view of the workmen this morning—disguised as a sideboard. The trick of fitting false legs and a false back to it was a masterpiece, I reckon!"

He grinned towards the object he named. Already the legs and back had been moved from the great chest and a covering of tapestry had been flung across it as it stood in the corner of the room.

"I give you all that," the grim-visaged professor said. "It is not the chest nor the work that you have performed here that I am troubled over. It was the fact of meeting that young cub, Tinker."

He had made a confidant of Carlac in the matter, but the broad-shouldered criminal shook his head.

"I think that you were mistaken this time, Kew," he returned; "there is no conceivable reasons to connect Tinker's appearance with our presence here. It was just an unfortunate coincidence; and the only thing I find to regret in the business is what happened after you set eyes on him."

Kew's cruel lips lifted in a passionate smile.

"Meaning the death of the taxi man," he said. "Oh, I am not concerned about him! He was a blundering fool, and would have caused trouble. I had to get away at once and without being recognised. The man would have detained me—he had to be removed."

He dismissed the matter with a wave of his lean hand.

"But, still, I am prepared to give in to you in this case, Carlac," he said. "If you are of the opinion that Blake knows nothing about us, then let us carry the final move out."

"Now?"

Kew arose to his feet.

"Why not. It is just five o'clock. The faithful Abul will be squatting outside the door of the treasure-room, tulwar over his knees, his keen ears on the alert. We could not choose a better occasion."

Now that the cool voice proposed the actual deed, Flash Harry, a craven at heart, began to have qualms.

"Couldn't we wait for a bit," he muttered; "it's early yet. Perhaps later on there wouldn't be so much chance of us being heard. We—we might trip over something, then—"

"There are a hundred 'mights' that could happen," Kew's cutting voice returned; "what we have to do is to guard against all of them, and be very careful."

He turned his back on Harry, addressing Carlac.

"Now is the best time," he explained; "you and I are out of the house. We know that, this afternoon, Colonel Bryce and Lord Eagley, of the Foreign Office, both inspected the chest and its contents, assuring themselves that everything was correct. You hear the colonel say that that was going to be done. If the chest vanishes and the duplicate is put in its place now, who can blame us?"

The strong face of the tall criminal lighted up in a quick sarcastic smile.

"We don't want anyone to blame us," he returned grimly; "but, all the same, I think you're right. Now is the time."

He slipped out of his jacket and rolled up his sleeves, revealing the great bulging muscles of the forearm. Flash Harry eyed the powerful limb admiringly.

"I always said that the count ought to have been a wrestler," he said; "there's a muscle for you. Lord, he could tackle the pick of them, he could."

He had also removed his coat as he spoke, but Kew did not follow the example set by the other two. A sudden tense silence descended on the man. Carlac, with a quick, light tread, reached the chest and nodded to Flash Harry.

"We'll get it as near to the fireplace as we can," he whispered, in a low tone.

The chest had been weighted with heavy blocks of lead, and it was all that Flash Harry could do to carry his end across the room.

Kew had already removed the rugs and fire implements from the hearth. He looked up at Carlac, who nodded his head. "Right," the powerful man muttered.

Kew, stooping down, caught at the bars of the grate and pulled. Noiselessly the whole back portion of the fireplace swung upward and outward, leaving a gap four feet high and about four feet wide. Through the gap it was pitch dark, but the light from the room they were in shed a faint gleam into the interior beyond, revealing the edge of a carpet and an ornamental hearth.

"The glim—quick—out with it," Harry breathed. And Kew, leaping back to the gas-jet turned out the flame. Carlac lowered the corner of the chest, and stepping into the open gap, listened for a moment. There was no sound and at last he turned his head. "Pocket-torch!" he breathed. And a long slender tube was thrust into his hand.

A little bulb of light leaped from between his fingers and raced for a moment over the carpet, to settle at last on the square outlines of the rajah's war-chest. "Right, come on. Careful now!"

Anton's masterpiece was lifted, and with noiseless steps Carlac and Flash Harry entered the other room, dipping low to avoid the uplifted grate. They tip-toed across the chamber, and resting their own burden for a moment, tackled the heavy treasure-chest. It was almost more than they could manage; Carlac, strong as a bull, was capable of swinging his end, but Flash Harry, tug though he did until the sweat stood out in beads on his forehead, could not make it stir. Suddenly the man felt a breath at his side, and the voice of Kew sounded.

"Now lift!"

The great chest came up in answer to their combined efforts, and the slow painful journey towards the gap began. It was well for them that the chest had been deposited quite close to the grate of the room. They had only to carry it some ten or fifteen feet, and yet, by the time that it had been set down in the other room, Carlac was panting for breath. Flash harry collapsed over the top of the chest with a stifled groan.

"I—I'm—beat!" he muttered hoarsely.