RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

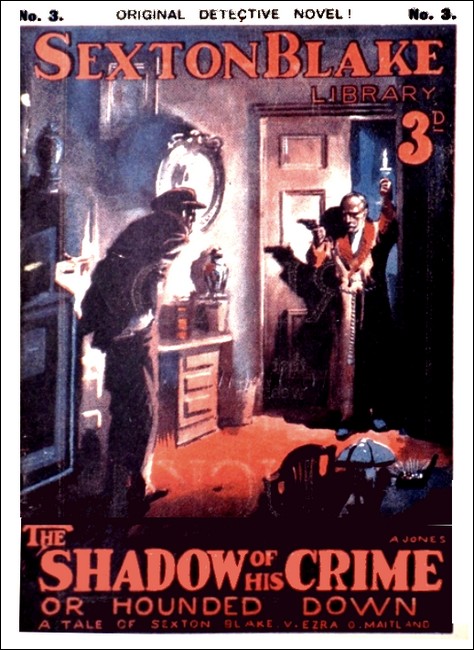

The Sexton Blake Library, Nov 1915, with "The Shadow of His Crime"

Sexton Blake

I. — Clench and Cavendish, Financiers

THE clerks in the spacious general offices of Messrs. Clench and Cavendish, Financiers and Company Promoters, of Throgmorton Avenue, were preparing to leave for the night, but in the private sanctum of the partners, there were many signs suggesting that work was not yet at an end.

Jasper Clench, a tall, lean man, with a pale, shrewd face, lit by keen grey eyes, was poring over a private ledger, whilst his partner, Richard Cavendish, was seated at the opposite side of the table, counting the immense pile of bank-notes before him, and making them up into batches of £5,000.

Richard Cavendish presented in appearance a striking contrast to his stern-visaged partner. Cavendish was a trifle short and stout, and possessed a merry, fresh-complexioned countenance, and a pair of twinkling black eyes. He at all times looked sleek and prosperous, from the top of his well-oiled head to the toes of his immaculate patent boots, and it was for this reason that when a client was doubtful about some investment he or she had made with the firm, it was Mr. Cavendish who attended to the reassuring interview.

Cavendish was the owner of a glib tongue, and a manner as sleek and oily as his looks. He could talk the most doubtful would-be investor over to his side, and convince one who had lost heavily by the collapse of one of the firm's companies, that he was taking a pessimistic view of matters, and ought to try again.

Despite Richard Cavendish's powers of oration, however, both partners realised that the time had arrived when London was decidedly too hot for them.

During the last six months the number of dissatisfied clients calling at the offices had unpleasantly increased. The Easy Investment Syndicate, the Cape Diamond Concessions, and the Greshamly Rubber Company—all three concerns, which Clench and Cavendish had floated upon public money—had somehow gone smash, and now clients were becoming far too inquisitive over their "Great Eagle" shares.

Two days ago, an aggressive American client, handling a dog-whip suggestively, had tried by force to gain an entry into the private sanctum; and only yesterday there had been the widow who had openly wept before the clerks and declared that she had been swindled.

The Great Eagle Gold Mining Co. was the last "little affair" with which Messrs. Clench and Cavendish had amused themselves.

A well-known mining engineer—who, by the way, was now very much missing from Britain, and enjoying some of the firm's money upon the Continent—had journeyed to Brazil, where the site of the Great Eagle properties was situated, and he had sent home a glowing report that the ground was positively teeming with the precious metal.

Upon the strength of this, Messrs. Clench and Cavendish had sent out thousands of alluring prospectuses, and filled the pages of the Press with hosts of gripping advertisements, and their energies had not been in vain.

There are always plenty of people in this curious world of ours who are stupid enough to think that by expending a little capital, they can become millionaires without the slightest trouble to themselves, and the abundance of "fish" Clench and Cavendish's "nets" had caught pleased the swindlers mightily.

They did not trouble that when the crash came many thousands of hard-working men and women would lose their lives' saving—their all! Like all men of their class, they were selfish to the last degree, and they were out for every pound they could rake in.

But now, as we have already said, investors wanted news as to how the Great Eagle Properties were progressing, and the company promoters knew that it was time they discreetly withdrew from the scene of their scoundrelly operations.

Jasper Clench closed the ledger and locked it carefully, and, lighting a cigar, he sat watching his partner until the latter had completed his count of the notes, and had stowed them away in a portmanteau, which stood by his side upon a chair.

"Well?" Clench asked, in the hard voice that was characteristic of him. "You found my calculation was correct?"

Richard Cavendish rubbed his fat hands together, and smiled his suave smile.

"Precisely," he murmured. "The notes total just over two hundred and fifty thousand pounds, and there's a like sum in easily-negotiable securities—altogether half a million, my friend. Half a million to bolt with! It's not so bad!"

Clench nodded; but he did not return the other's smile. Indeed, it was seldom that he troubled to evince any sign of pleasure. He was always the hard, calculating man, whose one thought was the making of money. Mammon was the god he worshipped, and nothing else mattered.

"There will be another ten thousand to add to our haul by the first post to-morrow morning," he said thoughtfully, as he examined the end of his weed to make quite certain it was burning evenly. "That foolish old woman at Merton promised to send me a cheque for the shares she wishes to take up, immediately she arrives home to-night. I convinced her that the cheque must be left open, and advised her to send it by registered post. As soon as it comes to hand in the morning, we can cash it, and get along to your yacht."

Cavendish drummed his fingers upon the table and looked doubtful.

"Wouldn't it be almost as well to leave to-night?" he asked slowly. "The yacht could sail by this evening's tide."

Clench made a deprecating gesture with his hands. "And leave old Mrs. Burton's ten thousand behind?" he asked, with something like a sneer in his voice. "Bah, man, where is your nerve?"

"I don't know about nerve!" his partner retorted. "To be too daring is to be foolhardy. The police are paying us far too much attention of late. The big man, whom I spoke of the day before yesterday, was hanging about again to-day, when I went out to lunch."

Clench sat a little more upright in his chair. "You are sure of that?" he asked sharply.

"Yes," Cavendish agreed. "There maybe no harm in him, but to my way of thinking, he looks very like Scotland Yard."

He shuddered perceptibly. "I'm not anxious to see the inside of one of her Majesty's prisons. With all our other coups we have left a loophole through which we could wriggle and clear ourselves; but with this Great Eagle business we could do nothing but return the bulk of the money we have netted, leaving but a most inadequate profit for ourselves, if we wanted to escape doing time for fraud. We planned to make this our last great coup—to leave England with every penny of the public's money—and there's no sense in hanging back to add a paltry ten thousand to the half-million we've already cleared."

"Oh, we shall escape safely enough," the other protested, "and we shall take every sovereign with us. Let me see you lock that bag away in the safe, then we'll leave until the morning. Hark! That is our cab drawing up, now."

Cavendish hesitated, fidgeting with his podgy fingers.

"Then you are going to stick to your original plan?" he asked.

Clench's cold, grey eyes looked back into those of his partner, and his thin lips curled into a sneer of contempt.

"Of course!" he snapped. "You ought to have been a woman. You haven't the pluck to be a man—and a rogue. Put the stuff away, and let us get out into the open air. The atmosphere of this stuffy place makes my head ache."

He watched his partner whilst he took up the portmanteau and placed it within the massive safe, which stood behind the door. When Cavendish had locked the safe, Clench turned to the door leading to the general offices, unlocked it and passed through.

"I'm going next door to buy some cigars," he said, over his shoulder. "I'll see you in the cab."

Richard Cavendish nodded, then stood looking after him with clenched hands. The merry light had died from his eyes, and his face was not at the moment a pleasant spectacle to behold. The flabbiness seemed to leave his cheeks, his jaw was harshly set, and his whole aspect was sinister in the extreme.

"You sneering, pig-headed brute!" he snarled, when his partner had passed out of hearing. "You can stay and be nabbed if you're so minded, but you won't have me with you when you are arrested. I've tried to talk sense to you, but you won't listen, so I've got to look after myself. I'm going to take my share to-night, and by morning my yacht will be miles out to sea."

Over the City hung that curious stillness that is always noticeable after about ten o'clock at night and Throgmorton Street was deserted save for the solitary constable, who was steadily pacing along upon his beat, his footsteps scarcely audible by reason of the thick galoshes covering his boots.

The man glanced into Throgmorton Avenue as he drew abreast of it, but the courtway was apparently as empty as the thoroughfare in which he stood, and he passed on indifferently, inwardly counting the hours before he would be off duty and able to seek his bed.

The pad-pad of the constable's footsteps died away into silence, and they had scarcely done so, ere a dark figure emerged from the shadows cast by the buildings in the court. It was a short, stout form, and as the moonlight fell upon the man's face the features of Richard Cavendish were revealed.

Cavendish, who was carrying a gladstone bag, boldly stepped across the court and paused before the door of the building wherein lay the offices rented by his partner and himself. He tried the door, and to his satisfaction he found that it was unlocked, a fact that showed that one of the porters or cleaners was still within the building.

Cautiously, for he had no special desire to be observed, the stout swindler pushed open the door, and glided into the hall, then upon tip-toe he made his way to the door, upon which, even in the semi-gloom, could be read the legend "Clench and Cavendish-Private."

Cavendish took a bunch of keys from his pocket, inserted one in the lock and turned it noiselessly. A moment later he stood within the office, breathing hard in his excitement, the door once again securely fastened behind. He lost no time now in carrying out his object, he whipped out a pocket electric torch, and, keeping the white beam of light low, so that it should not be seen by anyone who might chance to pass the glass door, he guided his footsteps to the safe, wherein lay the gigantic sum with which he had arranged with his scoundrelly partner to decamp upon the morrow.

Yet again, the swindler's bunch of keys was produced, and he placed one in the lock of the safe. There was a soft click, then Cavendish had tugged open the massive door and the contents of the safe lay at his mercy.

He took a grip upon the handles of the portmanteau, and, lifting it out, he placed it upon a chair. Then he picked up his gladstone and stood it upon the table.

At that moment Richard Cavendish had no intention of defrauding his co-swindler. He merely meant to possess himself of his share of their ill-gotten gains, and to sail away with all speed in his yacht, which was lying at anchor off London Bridge. But when he opened the portmanteau, and once again feasted his gaze upon its valuable contents, a sudden gleam of avarice leapt into his eyes, and he was assailed by an overmastering statue carved in stone, although his brain was working quickly. In the darkness his eyes were still glinting greedily, and his lips were compressed temptation.

"Why not take all?" he whispered to himself, staring down in fascination at the rolls of notes and securities. "After all, it is not Clench's money!" It did not occur to him that neither was it his. "He has swindled honest men and women to obtain it, and it would only be a case of the biter bit."

Richard Cavendish put out his electric torch and stood as motionless as a thin straight line.

What should he do? he asked himself. He had never liked Clench—indeed, during the last few weeks of their partnership, he had began to feel that he hated him. Time after time he had been stung to the quick by some sneering remark of his partner's, and—

Richard Cavendish closed the portmanteau with a snap and locked it, and now his mind was made up.

"I'll do it!" he muttered. "I'll take the whole half-million. With a sum like this I need never return to Britain. I can change my name, and live a life of luxury and ease. And when my son grows up, he will never know that his father was once dishonest—a swindler! Somehow I'm glad that—" He shrugged his shoulders impatiently. "At times, I am a sentimental fool!" he rasped. "I mustn't waste time! The farther away from British shores my yacht can be by the morning the better! If Clench overtook me, he would kill me!"

He took up the portmanteau and, staggering beneath its weight, he crossed to the door. He turned the key, passed out, and relocked the door behind him; then without being seen by a living soul, he quitted the building and made his way into Throgmorton Street, where he hailed a passing hansom.

Richard Cavendish had taken the whole coup. Jasper Clench, swindler, had been swindled!

II. — A Dramatic Arrest and a Vow of Bitter Vengeance

THERE was a deep frown upon the brow of Jasper Clench as his cab slowly conveyed him through the dense fog that, with the coming of dawn, had descended upon London like an all-enveloping blanket. That morning he had called at his partner's private house in order that they might journey to the City together as was their custom, but to his surprise he had discovered that Cavendish had left home with his baby son and the child's nurse late upon the preceding night, and had not since returned.

Clench had made endless inquiries of the servants as to the reason for his partner's sudden departure from home, but none of them appeared to know what reason their master could have for his somewhat peculiar action.

It never occurred to Clench for a moment that his fellow-conspirator might have stolen a march upon him, yet he felt curiously worried by what he had ascertained, and a hundred times he had cursed the fog during his journey from suburban Wimbledon to town.

The swindler sighed with relief as the Jehu at last guided his horse into Throgmorton Street, and he lost no time in alighting and paying off the man when the court in which his offices were situated was reached.

As he groped his way through the choking mist into Throgmorton Avenue the company promotor collided violently with a bulky form, and he trust it unceremoniously out of his path.

"Where the deuce are you coming to?" the man queried pugnaciously. "Do yer want all the blessed path?"

Jasper Clench paid no heed, but kept straight on until he disappeared through the doorway of his office-buildings, and the burly man, who might have been a well-to-do tradesman, if one might judge by his general aspect and attire, indulged in a grim smile.

"You seem in a hurry, Mr. Clench," he muttered beneath his breath. "I wonder what has become of your precious partner? I don't think he's passed in yet; still, he may have arrived early."

He turned and whistled softly, and almost instantly the figures of three more men loomed out of the fog. They were all of a similar stamp to the fellow with whom the swindler, Clench, had collided—big, burley, and strong. They, too, might have been men of a hard-working, tradesman class, yet when one looked the second time one was struck by something strangely official in their bearing.

"How long have you been waiting about here, Hemmings?" the first man asked, addressing one of the newcomers.

"Since eight o'clock, sir."

"Ah! Clench has just gone to his office. Have you seen anything of the man Cavendish?"

"No sir, I've kept my eyes skinned, but he hasn't passed me to the best of my knowledge!" The questioner nodded.

"Right!" he answered gruffly. "Keep within hailing distance. If the other beauty don't turn up soon, we will make sure of getting Clench first. Cut away with you. We mustn't be seen together."

The three large men disappeared into the fog once more, and the first man entered the courtyard and took up his stand at a spot whence it was just possible through the mist to observe any person leaving or entering the building wherein Clench and Cavendish carried on their questionable business.

Jasper Clench had stopped to speak to his head clerk. He had made enquiries as to whether his partner had put in an appearance, but it was only to be answered in the negative, he still wore a puzzled frown as he unlocked the door of his private room and passed within.

His first action was to examine the contents of the letter-box, and a cynical twitching of his thin lips proclaimed that he was experiencing a feeling as near to pleasure as he was capable of, as he selected a registered envelope, addressed in a feminine hand. The missive, had, of course, been signed for by one of his clerks and afterwards slipped into his private box.

He ripped the letter free from its covering and saw, as he had expected, that it contained the promised cheque for ten thousand pounds, promised him by his client of Merton, he stowed it carefully away in his pocket and hummed a tune as he turned to his table.

The air, however, ceased with startling abruptness, and the swindler stood staring at the gladstone bag which was in evidence before him. That it was his partner's property he realised at once, for it bore the initials "R.C." upon its side, but what bewildered Clench was that he was sure the bag had not been in the office upon the previous evening.

"Now what the dickens can this mean?" Clench said in a puzzled tone. "The clerks say he has not been in, yet the first think I find—"

He stopped short, uttered a gasping cry, and fairly leapt over to the safe, the door of which was standing a few inches ajar. With shaking hands he wrenched open the massive steel door, then he went reeling backwards, his always pale face the colour of chalk, every drop of blood gone from his lips.

"Gone!" he screamed hoarsely. "Gone!"

Like a drunken man he swayed to his knees before the safe, groping blindly within as though he could not put faith in the evidence of his eyes.

"Gone!" he raved again. "The cur! The dirty, thieving hound! The treacherous scoundrel! He has robbed me—robbed me! I—"

The door opened sharply and the bulky form of the man who had been waiting in the court without stepped quickly into the office. He was followed by his three companions, who stood in the background.

Clench gained his feet, clutching at his temples, and his wild eyes fixed themselves vacantly upon the stern faces of the intruders.

"What—what does this mean?" he asked shakily. "I can see no one this morning. I—"

"You will have to see me, I think, Mr. Jasper Clench," the foremost man snapped grimly. "I am Detective-Inspector Rayner, of Scotland Yard, and I hold a warrant for your arrest upon a charge of fraud!"

Jasper Clench clutched at the edge of the table for support, his knees shaking beneath him, his mouth agape with surprise and horror.

"It's a lie!" he stammered, his voice almost hysterical. "It's a foul lie! I am an honest businessman and—"

"You will have every opportunity of proving it!" Inspector Rayner answered gruffly, as he took a sharp step forward and snapped the handcuffs upon the swindler's trembling wrists. "I don't mind telling you, however, that I wouldn't give a brass farthing for your chance! James Teddington, the engineer sent out to prospect the Great Eagle Mining Properties, has died as a result of an accident in Paris. Before he breathed his last he confessed how you and your partner had bribed him, how he had found not an atom of mineral on your land, but had sent home a false report that the place was a modern Tom Tiddler's ground. Now, I'm telling you no more. I must warn you that anything you say may be taken down in writing and used at your trial in evidence against you!"

"Great heavens, this is terrible—terrible!" Clench moaned. "And to think that my partner has escaped—escaped with every penny of the money we have made together! Curse him, I say! I'll serve my time! I'll—"

"What's that?" Rayner asked sharply, startled out of his official manner. "You said your partner, Cavendish, has gone with the money?"

"Every penny of it!" Jasper Clench laughed horridly, mirthlessly. "Every penny of it!" he raved. "We were to have sailed with our haul in his yacht this morning, but you'll find it weighed anchor last night! Oh, yes, you'll find it gone, right enough! Oh, I pray and hope that you may find the viper—I would serve a double sentence to know that he will suffer as I shall suffer!"

His eyes blazed like living coals with the awful hatred that consumed him.

"Whether he be caught or not!" he cried hoarsely, "I'll be even with him! If I have to serve ten—fifteen years I will not forget! When I come out, I'll hound him down! I'll hound him down, you hear me! And when I find him, I will deal out to him the most bitter vengeance ever devised by the brain of mortal man!"

The Reception at Sir Digby Cranston's.

OUTSIDE the residence of Sir Digby Cranston, in Berkeley Square, an awning had been erected from the gate to the imposing entrance and a strip of carpet ran beneath, reaching to the edge of the pavement. The windows were ablaze with lights, and all through the evening a host of carriages and motor broughams had rolled up to discharge elegantly-cloaked ladies and immaculate debonair men, at whom the loungers who hung about the spot gaped with something very like awe.

Sir Digby Cranston, who was a very wealthy gentleman and a keen and well-known collector of precious stones, was holding a reception to celebrate the return of his only child, Elice, from France, where she had been nobly acting as a Red Cross nurse, and although the evening was as yet young, a vast and distinguished gathering had put in an appearance.

A myriad festooned lights illuminated the spacious reception-room, playing upon the khaki uniforms of the officers, the conventional black coats of the civilians, and the pearly white shoulders of the women. An orchestra, concealed in an alcove behind a cluster of ferns and palms, was playing a dreamy air.

A gentle breeze, scented with the sweet, refreshing odour of roses, was wafted from the direction of the archway forming the entrance to the conservatory, fanning the faces of the guests as they chatted vivaciously together.

Sir Digby, a distinguished-looking man of sixty, attired in faultless evening dress, stood by his daughter's side as she received the fresh arrivals. Elice was a charming girl of twenty-one, simply yet daintily gowned, and it was noticeable that her right arm rested in a sling, venturing too near the firing line to tend the wounded and dying, she had been wounded by a splinter of shell, and she was a girl to be admired, for she had bled for her country.

Sir Digby Cranston's eyes were continuously straying across the room to where a woman sat alone, slowly using her fan, the lights lending additional charm and lustre to her fair golden hair.

The nobleman was a widower, and perhaps this was the reason for his obvious fascination where this woman was concerned. To merely say that she was beautiful would be to most inadequately describe her. She was dazzling, there was something about her—personality perhaps—that irresistibly invited attention and held the gaze.

She might have been twenty-five—perhaps a little less, and her complexion was pale and creamy. Her eyes were dark and melting, her lips full and alluringly red, and she made a picture such as surely no artist could faithfully portray. She was attired in some glistening stuff that fell sheerly away from her rounded shoulders; and Sir Digby told himself that he had never seen this woman look so charming.

And yet she was not of high birth. She was simply his private secretary, and he knew her as Miss Hammond, from Chicago. Upon many occasions since the girl had come to him with testimonials from an American millionaire, Sir Digby had seriously thought of asking her to be his wife, yet it was possible that he would have suffered with a stroke of apoplexy could he have known her true identity, or have guessed that her glorious masses of hair were merely a skilfully-made wig.

Broadway Kate, the wife of Ezra Q. Maitland, the man who surely could be termed the greatest criminal at large, found it convenient at times to assume male attire, and for this reason she was wont to keep her hair cropped to her well-shaped head, merely adjusting a wig, such as she was now wearing, when appearing as a member of the fair sex.

For many years Kathleen Maitland had been a criminal. When she had first married her husband, Ezra, he had been a successful and straight-forward business man in New York, and they had been supremely happy. Their happiness, too, had increased a hundredfold when they had been blessed with a child—a baby girl.

Olive, their little daughter, had reached the age of four, then misery—misery in a hideous form—had descended upon them like a thunderbolt. Little Olive had fallen ill and died, and this had turned Kate's husband, for the bad.

It had been small swindles and robberies that he had indulged in at first; but soon, confident with success, Maitland had engaged in colossal crimes that had startled the world. Where the man led, the woman had followed, and thus Kate became her husband's partner in crime.

Maitland was possessed of a cool, reasoning brain, and time after time he had outwitted the astute American detective, Fenlock Fawn, who continuously failed to obtain any definite evidence against the master criminal.

New York, Petrograd, Paris, and London had been visited by Maitland in turn, and in each city he had succeeded in hoodwinking the police and detectives until, in the last-named, he crossed the path of Sexton Blake, the famous logician and criminologist of Baker Street.

The alert, clever brain of the master detective had been pitted against that of the master criminal, and upon each occasion, although Maitland's supreme conceit had not allowed him to admit it at first, Sexton Blake had proved that he was the better man, and the criminal had only escaped the clutches of the law by, metaphorically speaking, the skin of his teeth.

Broadway Kate sat abstractedly fanning herself until she heard Sir Digby announce that some private theatricals were about to take place in an adjoining room, then she rose to her feet and carelessly strolled to the archway leading into the conservatory.

Through this she passed and made her way between the long lines of ferns, palms, and rare blossoms until she gained the small garden at the rear of the premises.

She crossed a corner of the miniature lawn, and approached a clump of evergreens. As she reached them a dark form of a man emerged from the shadows.

"It that you, Ezra?" she asked, in a low tone.

"Bet on it!" the man who had met her agreed. "Waal, how are things shaping?"

"Real fine, I guess," Kate replied quickly. "As I thought, the jewels have been on view during the evening!"

Ezra Q. Maitland—the man was he—chuckled softly and pressed his wife's hand in the darkness. "Good girl!" he said appreciatively. "And they will be in the house all night?"

"Yes," Kate informed him. "Old Sir Digby will lock them in his safe, which he considers to be as secure as the Bank of England. You have had made the key of which I gave you the wax impression?" Maitland grinned.

"You bet I have," he drawled. "I wasn't likely to let the grass grow under my feet. Kate, we are in luck! If there's any truth in the rumours I've heard, Sir Digby's collection of sparklers are worth something like two hundred thousand pounds, and even in dealing with that thief, Israel Samuels, we ought to clear seventy or eighty thou."

The woman lit one of her daintily scented cigarettes.

"Have you written to Sammuels?" she asked.

"Yes, I've replied to his note," Maitland answered, "and he's open to do the deal whenever I bring the stuff along. But I mustn't stay. If you were found talking to me out here, it would be difficult to explain my presence. By the way, where is the safe situated?"

"In Sir Digby's study!"

"And the position of that?"

"Over there to the right. You can see the French windows quite plainly from here."

"Good! I shall be right along just before dawn. I suppose they'll keep this poppy show up to well into the early hours of tomorrow morning?" Kate nodded.

"I reckon they are bound to," said she. "I shouldn't come here until well after three!"

"Make it half-past," Maitland said, after a moment's thought. "That will give me time to do the job and make myself scarce before daylight. You will be able to open the windows for me, of course?"

"Yes."

"Good!" Maitland said again, as he turned to depart. "I'll get right along and lie low until the right time! Say!"—he suddenly swung round upon his heel—"give me a kiss, girl! I've not seen you for four whole days!"

Kate held up her lips to his, and just for a moment the master-criminal held her in his arms, then he released her and vanished silently into the gloom. The woman stood staring in the direction he had gone for nearly a quarter of a minute before she moved to retrace her steps to the house.

"How I wish we could start afresh!" she muttered, a catch in her voice. "How happy we could be, just he and I together and—"

She tilted her shoulders and sighed wearily.

"That can never be," she said, "until we have made the tremendous coup we have been planning for so many months—a haul that would keep us in luxury in some distant land for the rest of our lives!"

Maitland at Work.

ONE by one the lights in the windows of Sir Digby Cranston's mansion had been extinguished until the house was enshrouded in darkness, and the strip of garden at the rear was only illuminated by the waning light of the moon.

From a distance came the voice of a clock chiming the half-hour after three, and the sound had scarcely died away ere Ezra Q. Maitland, his coat collar turned up to hide any vestige of white, a mask concealing the upper portion of his sinister features, stole along the alleyway which was connected with a garage, and which ran along at the rear of the wall enclosing Sir Digby's garden.

When Maitland reached the nobleman's premises, he paused and listened intently, smiling grimly as, after a second or two, he assured himself that all was silent as the grave.

With a quick, neat spring, he gripped the top of the garden wall with his muscular hands and drew himself up, to afterwards drop noiselessly to the other side. Stealthily he stole over the tiny lawn and darted behind a clump of bushes at the spot where he had previously met his wife.

Crouching down, but out of sight, Maitland lay peering through the bushes. He knew that it was past the time at which he told Kate he would arrive, and he wondered how long she would keep him waiting. He cursed softly as the dew from the grass found its way through his clothes and damped his flesh with its icy touch. The morning was cold for the time of year, and the criminal's wait was to be anything but a pleasant one.

Ten minutes, a quarter of an hour dragged by, and he wished he could smoke a cigar. He took one from his case, but hesitated for the present to light it, fearing its glowing end might be observed by someone from one of the windows.

Maitland lay watching the French windows of Sir Digby's study for another five minutes; then, with an impatient gesture, he placed the cigar between his teeth and felt for a match.

He swore under his breath as he discovered that he had omitted to bring with him his vesta case, and he began rummaging in his pockets in the hopes of finding a stray Inciter.

At last he found one in his vest-pocket, struck it upon his trousers, and applied it to his weed; then he lay puffing at the smoke until a light suddenly sprang up within the study.

The master-criminal gave something like a sigh of relief, and, tossing away the cigar, he rose to his feet, for the windows had opened, and the slender form of his wife emerged on to the lawn. She was attired in a neat travelling costume, and carried a small bag, and it was noticeable that her hair was now of raven black, also her complexion was more ruddy and the curve of her brows had changed.

"Is all quiet?" Maitland asked, as he reached her side.

"Yes," Kate replied. "You can get right along with the job; but you'd better be quick."

"Why are you late?" her husband asked. "I've been fooling around for the last five-and-twenty minutes."

"I am sorry," Kate replied, "but I fell asleep. I had had a tiring day. You'll have to look slick, because the butler is an early riser. He's often about a little before five."

"I reckon I shall be miles away by the time the old fool rubs the sleep from his eyes," the master-criminal grinned reassuringly. "Is it safe to leave these lights going?"

"Yes, I imagine so. No one can see them from the lane at the back."

"Right! Come along. Guess I'll give you a helping hand over the wall before I start work."

Broadway Kate hesitated, her eyes wistful.

"I'll stay with you until you've got the jewels," she said. "We—"

"Say you'll do nothing of the kind, my girl," her husband returned sharply. "There's always a chance of having to make a sudden bolt over jobs like this, and if you were with me you'd be in the way. Besides, I've no wish to let you sample prison life, and you're not taking the risk. Come along, and don't waste any more time."

Kate sighed resignedly, then allowed him to take her arm and gently propel her towards the wall.

Cunning and unscrupulous criminal though he was, Maitland had one redeeming feature—his great love for his wife. He worshipped the ground upon which she walked, and Kate, knowing this, was always ready to obey him without question.

By the wall they paused, and the master rogue spoke quickly to his fair companion.

"I reckon we'll give America a turn again after this Kate," he remarked. "I've been planning that for some time past, and I've arranged with Wang"—he was referring to his Chinese servant and confederate—"to meet at Euston. You will both catch the first possible train to Liverpool and meet me at the Great Central Hotel. Good-bye for the present."

"Good-bye, Ezra!" the woman returned, her lip quivering. "Be careful, and, mind, no violence if—"

"Don't worry," he interrupted. "I'll be successful, and the 'sparklers' will be in Samuels's hands before old Sir Digby finds out they are gone!"

He stooped and kissed her, then he assisted her over the wall and cautiously retraced his steps towards the house. Maitland entered the study, the windows of which Kate had, of course, left ajar. Almost at once he espied the safe, which was built into the wall upon the opposite side of the apartment. He lost no time in getting to work. He took from his vest pocket a glittering key, and, with deft fingers, inserted it in the keyhole of the safe.

He pressed it gently, then more firmly, only to finally curse beneath his breath, for the key would not turn.

Maitland drew the key from the lock and took from his pocket a tracing of the original one, which Kate had handed to him together with the wax impression she had managed to secure.

The criminal's eyes keenly studied the formation of wards, then he produced a tiny file and a miniature bottle of oil, for he had detected a slight difference at one point.

He set to work patiently, despite the tiresome task that lay before him. He had to proceed by guesswork, and he knew that if he filed the ward a little too much, there would be no chance of his gaining the haul he was seeking.

Four times he inserted the key in the lock to find that it would not turn, but at the fifth attempt there came a soft clicking sound as the lock of the safe shot backwards, and, with a chuckle of exultation, Ezra Q. Maitland pulled open the heavy door.

To discover the prize for which he was seeking was the work of a moment. No less than seven leathern cases lay within the safe, and, upon making a swift inspection, the American crook found, as he had expected, that they contained Sir Digby's famous collection of precious stones.

He removed the cases, and placed them upon the table, opening the lids in turn. Diamonds, rubies, sapphires, emeralds, and host of other gems were in evidence, and as the rays of the electric lights fell upon them, they glittered and scintillated until Maitland's eyes were dazzled.

He stood for a moment gazing exultantly at his coup, mentally resolving to ask from the fence*, Samuels, five thousand over the price he had originally intended to let it go at. His piercing eyes were glinting like stars through the holes in his mask, and their brilliance vied with that of the heap of stones lying before him.

[* Receiver of stolen goods.]

He roused himself from the spell the magnificence of the jewels had cast over him, and whipped two wash-leather bags from his pocket. He filled them to the brim with the sparkling gems, and concealed them about his person, but even now there was still quite a quarter of the collection left upon the table.

Maitland grabbed up a handful of the stones, meaning to place them in his breast-pocket, but before he could do so, he received one of the greatest and most alarming surprises of his life. The door of the study suddenly opened, to reveal Sir Digby Cranston, attired in a dressing-gown and slippers, carrying a candle in his left hand, a businesslike-looking revolver in his right.

The old nobleman came very near to worshipping his collection of jewels, and he was always nervous and restless, when they were in the house during the night, although he had always believed that his safe—the safe that Maitland had succeeded in opening in less than twenty minutes—was more or less burglar-proof. Upon the present occasion, he had lain awake for just over two hours after he had seen his last guest off, and retired to rest, and he had been obsessed with a strange feeling that his collection of gems was in danger.

He had tried to think that he was allowing himself to be over-imaginative, and stupidly nervous, but at last, unable to court repose, he had decided to journey down to his study to satisfy himself that all was well.

Despite his fears, Sir Digby had scarcely expected to find a burglar at work in the room when he pushed open the study door, and he was almost as surprised at seeing Maitland as was the master-criminal at suddenly being confronted by him.

Sir Digby took a startled step backwards, a cry of alarm bursting from his lips, then, in a glance, realising how matters stood—that he was in danger of losing the greater part of his treasures—he levelled his revolver and pulled upon the trigger.

There were two deafening reports, one following sharply upon the other but it was Ezra Q. Maitland who had shown the most promptitude. Long experience had taught the master-criminal that at such times as these, it was the man who fired first who lived to tell the tale, and he had not hesitated when Sir Digby had flung up his right arm.

Like lightning, Maitland's hand had dropped to his hip, his fingers had gripped upon his weapon, which he had fired almost the instant it was out of his pocket without appearing to take the slightest aim, and Sir Digby's bullet tore its way harmlessly through one of the drawers of a roll-top desk, as the nobleman fell heavily upon his face.

Maitland did not stop to see how badly the old man was injured, not did he trouble about the remainder of the jewels. He spun round upon his heel and rushed madly through the windows, raced across the lawn with the speed of a hare, and gained the garden wall. With an agile spring he was sitting astride it, and as he dropped to the opposite side, he could hear the sounds of excited voices from the house, whilst lights were springing up in the windows.

The criminal cursed at what he considered his ill-luck, then pressing his elbows to his sides, he positively flew up the alleyway, and vanished into the gloom.

And back in the study, Sir Digby Cranston lay inert and still, the blood from and ugly wound upon his temple dyeing the expensive carpet, a dull, ominous red, whilst his daughter Elice, who had just rushed into the room, was upon her knees by his side.

"Help, help, help!" the girl cried wildly, her eyes dilated and filled with horror. "Help, help, murder! My father has been murdered!"

At Baker Street.

TINKER, assistant to Mr. Sexton Blake, the famous detective of Baker Street, yawned and rubbed his eyes, as the clock upon the mantelpiece of the consulting-room chimed the half-hour after four, and he rose from the great easy chair in which he had been reclining, and stretched his arms wearily above his head.

"Well, I'm jiggered!" the young detective muttered, still sleepy and dazed. "I must have dozed off in that chair last night whilst I was sitting up for the guv'nor. Great Scott! Half-past four! Then this means that the guv'nor hasn't been home all night! Pedro, you red-eyed old scoundrel why didn't you wake me?"

Sexton Blake's clever and sagacious bloodhound rose and stretched himself, much as his young master had done, and afterwards squatted upon the hearthrug, and blinked sleepily at the lad. Then he stalked forward and affectionately fawned upon Tinker, who patted his massive head.

"I suppose you're not to blame, Pedro," the lad went on. "I'll bet you were playing at shut-eye before me. What do you want? Some coffee?"

He indicated the coffee pot and Pedro bayed softly. It was seldom he refused anything either of his masters took to eat or drink. Tinker picked up a pair of Indian clubs, removed his coat, and indulged in a little invigorating exercise, whilst the hound watched him with superior indifference.

After a few minutes of this the young detective picked up the pot and vanished to make the promised coffee. When a quarter of an hour had elapsed he returned, poured himself out a cup of the steaming beverage, and gave Pedro his share, with much milk added, in a saucer.

"Now, where the dickens is the guv'nor?" Tinker mused, when both he and Pedro had quenched their thirst. "It's too bad of him to leave me in the lurch like this. Ugh! I feel cramped and sore sitting in that beastly chair all night, and I've got a kink in my giddy neck. It feels as though it's going to walk round the corner. It's no use turning in, now, so I'll wait till Mr. Blake turns up. Now, let me see. What did his note say?"

He drew a slip of paper from his pocket, and perused the hastily pencilled words upon it.

"Just discovered whereabouts of Fenson" (they ran). "I am going with Inspector Martin to arrest. You can sit up for me if you like, as I expect to be home just before midnight:—S.B."

Tinker frowned, and his young face momentarily took on a grave expression.

"Humph!" he grunted. "I'm hanged if I like this. Fenson is a dangerous beast, and wouldn't be taken without a struggle. I hope nothing happened to the guv'nor. Still, nothing can have happened! I should have heard from Scotland Yard before now if he had been injured. I wonder what's kept him."

He replaced the message in his pocket, and sat for a few seconds gazing thoughtfully at Pedro.

"My lad," he said, at length, "you might as well go through that latest trick I've taught you. I don't want you to forget it, and we haven't practised it for several days."

He groped beneath the couch, and brought forth a soldier's helmet and a toy gun, with a result that Pedro put his tail between his legs, and hastily vanished under the table.

"Come here, sir!" Tinker ordered, with mock severity in his tones. "Laziness is a vice—"

He made a quick grab, and, securing the hound's collar, dragged him from his cover.

"Good Pedro, stand up!" he commanded.

With a bored expression upon his doggy countenance, the hound rose upon his hind legs, and his young master clapped the helmet upon his head, and tucked the gun in the crook of his right fore-paw.

"Shoulder arms!" Tinker cried. "Quick march!"

Then, beating time to the refrain, he commenced to sing, whilst Pedro, looking utterly foolish and disgusted, solemnly marched across the room.

"When we're wound up the 'Watch on the Rhine'! How we'll sing, how we'll sing 'Auld Lang Syne'! You and I, Hurray! we'll cry! Everything will—"

The door opened sharply, and Sexton Blake and Detective Inspector Martin, of the C.I.D., stood upon the threshold of the room, regarding the bizarre spectacle in amused surprise.

"Well, I always thought so!" Inspector Martin remarked, "although I didn't like to air my opinion until I was sure. When a young man gets up at a little before five in the morning to qualify for the proprietor of an educated animal show, he needs to interview a brain specialist."

"Oh I'm not potty, sir," Tinker retorted, winking at his master. "I'm merely looking ahead."

"What do you mean?" Martin asked.

"Why, you see, sir," Tinker explained, as he took the helmet and gun from Pedro, and tossed them out of sight beneath the couch, "if the detective's business failed we could go in for a penny gaff. Pedro knows lots of tricks, Mr. Blake would make an excellent wizard and fortune-teller, with a little make-up and the togs, whilst you needn't be idle."

"And what could I do?" Martin suggested, with an air of condescending amusement.

"Why, if you let your hair and whiskers grow, you'd make a jolly fine Wild Man from Borneo!" Tinker answered coolly, "We'd shove you in a cage, and all you'd have to do would be to dance and howl a little and—"

"Be quiet, Tinker!" Sexton Blake ordered sternly, for he had seen that the cheeks of his official colleague had flushed wrathfully. "Suppose you give us some of that coffee I see you have made. We are both tired and worn out."

The famous detective removed his hat and light dust coat, and tossed them aside, then he sank wearily into an easy-chair, and signed to Martin to do the same. Sexton Blake had spoken the truth when he had stated they were both fatigued. His always pale face looked drawn and haggard, and there were dark marks about his eyes, whilst even Inspector Martin had lost some of his ruddiness of complexion, and looked heavy-eyed and worn.

Tinker poured out the required beverage, and handed a cup to both the inspector and his master. As Sexton Blake stretched forth his long, slender hand to take his cup, Tinker saw that his wrist was bandaged. "You are injured, sir!" he said anxiously.

"Only a graze, lad," the detective replied, with a shrug. "How is it you are up so early?"

"I haven't been to bed, guv'nor," Tinker explained. "I was waiting for you to come in, and fell asleep in the chair. I didn't wake till about half an hour ago."

"Fenson led us a dance!" Sexton Blake said. "We found him in an opium den down East, but he fought like a madman when we attempted to arrest him, managed to break free, and eventually gained the roofs. He had a revolver, and we couldn't get near him for some time. He gave us the slip altogether once, but, quite by chance, we got upon his track again, and he is now safely under lock and key. Hallo!"—as the telephone bell rang sharply and insistently—"whoever can be ringing up at this hour?"

Tinker crossed to the instrument, and took down the receiver.

"Hallo!" he said. "That is Sir Digby Cranston's house at Berkeley Square? Yes; these are Mr. Blake's rooms. He's in, but he's been upon a case all night, and—"

"What is the trouble, lad?" Sexton Blake asked, rising from his chair, his weariness leaving him as if by magic. "Sir Digby Cranston is a friend of mine. What has happened?"

Tinker swung round from the telephone, his face evincing the keenest excitement.

"It's Sir Digby's collection of jewels, guv'nor!" he announced quickly. "Nearly all the stones have been stolen, and Sir Digby, who surprised the burglar, has been badly wounded!" Sexton Blake elevated his eyebrows and whistled softly.

"Let me speak!" he said, taking the receiver. "Ah, that is Miss Elice, is it not? Yes, I am Sexton Blake. When did the robbery occur?"

For several minutes the detective conversed with Sir Digby Cranston's daughter, who was at the other end of the wire, and ere he had finished, Inspector Martin was standing listening eagerly by his colleague's side. Curiously enough, like his friend, the Scotland Yard man seemed to have forgotten his fatigue, now that there was work to do.

"What has really happened, Blake?" Martin asked, as the detective hung up the receiver. "The man has got clear away?"

"Yes," Sexton Blake replied. "Sir Digby held a reception last night to celebrate the homecoming of his daughter, who has been acting as a Red Cross nurse at the front, and his renowned collection of precious stones were on view during the evening. He couldn't sleep when he went to bed, and had a presentiment that his jewels were in danger. He went downstairs just to satisfy himself that all was well, and upon entering the room in which his safe is situated, he found a masked man bending over the cases which had contained the gems, and which were standing upon the table.

"Sir Digby tried to fire, but the burglar managed to shoot first, and bolted with the best part of the collection!"

"Are you going to take up the case?" the official asked eagerly.

Sexton Blake nodded as he lit a cigar.

"Yes," he agreed. "As you may have heard me tell Tinker, Sir Digby is a personal friend of mine, so, tired though I admit I am, I cannot well refuse. Besides, this is no ordinary robbery. The Digby collection must be worth something like a couple of hundred thousand pounds! I have inspected it, so I know."

"Phew!" Martin ejaculated. "Do they know of the robbery at the Yard!"

"Yes; Detective-sergeant Jones is already upon the scene of the crime."

"Oh, is he!" Martin snorted. "That's the man who, quite by a fluke, got ahead of me in the Mortlake forgery business. Got ahead of me, mind you, his chief, and coolly took all the credit! I haven't liked the beggar since!"

"Naturally not!" Sexton Blake responded drily, and he wondered just what sort of a "fluke" had enabled his friend's subordinate to score. "Are you coming along to Berkeley Square?"

"Of course I am!" Martin answered. "I'm longing to dress Mr. High-and mighty Jones down!" he added aggressively. He grinned viciously. "Won't he be pleased when I turn up!"

"Suppose we leave off discussing this person with whom you seem to be riled!" Sexton Blake suggested mildly as he slipped into his dust-coat and donned his hat. "Minutes may count if we are to run the thief to earth and regain the jewels."

"Do I come with you, sir?" Tinker asked eagerly, as his master and the Scotland Yard man moved towards the door.

"No, my lad, not at present!" Sexton Blake returned. "But later there is a chance we may require both you and Pedro. If we do, I shall telephone, so don't go out upon any account."

Sir Digby's Story.

ELICE CRANSTON bent over her father as he stirred uneasily and awoke from the troubled sleep in which he had lain since the departure of his medical man.

The baronet was lying in his bed, and the ugly wound in his shoulder had been dressed after the bullet fired by Ezra Q. Maitland had been extracted. The old man's face was ghastly, his lips were bloodless, and his eyes unnaturally bright with the agitation that was obsessing him. The doctor had looked grave when he had made his examination, but he had given it as his opinion that with careful nursing Sir Digby would recover in due time.

The nobleman had refused to be warned as to allowing himself to become excited, and he had insisted upon telling his daughter what had happened in the study, requesting her to at once communicate with his friend, the great private investigator of Baker Street.

"I wonder how much longer Sexton Blake will be?" the baronet asked petulantly. "You—you said that he was up when you 'phoned, Elice?"

"Yes, dad," the girl replied, laying her cool white hand upon his feverish brow. "He promised to come here at once and he cannot be a great while. Ah, hark! There is someone upon the stairs now."

There came a tap on the door, and in response to the girl's order to "come in" the butler appeared.

"Mr. Sexton Blake and Detective-Inspector Martin have arrived, Miss Elice," the servant announced. "Shall I show them up?"

"Yes, yes!" Sir Digby exclaimed eagerly, before the girl could reply. "Let them come to me at once!"

"Dad, you must really keep calm," Elice insisted, with the gentle tone of authority in her sweet voice that her training as a nurse had gifted her with. "All the jewels in the world are not worth your life, and you know what Doctor Tilling said."

"Hang Tilling!" the baronet snapped, raising himself painfully upon his pillows, despite the restraining hand his daughter put out. "I want to sit up, Elice, so that I may tell Blake what has occurred! Confound you, sir!"—this to the butler—"Haven't I told you to show 'em up immediately!"

The man, who was a very old retainer, looked troubled, and glanced towards his young mistress. Elice inclined her head to show he was to obey, for she knew that the longer her father was kept waiting to see the famous criminologist to whom he wished to pin his faith, the worse his condition would become.

The butler disappeared, and presently returned to announce:

"Mr. Sexton Blake and Detective-Inspector Martin!"

Sir Digby turned so quickly that he jarred his wounded shoulder, and his face twitched with pain. He forgot his agony the next moment, however, as Sexton Blake and the burly red-faced official from the Yard entered the room and approached the bedside.

"I am glad that you have come, Mr. Blake," Elice said, as she gave the detective her hand. "Father is most anxious that you should take up his case!" Sexton Blake smiled into the girlish face.

"I don't think there will be any difficulty in that, Miss Elice," said he. "Fortunately, I am enabled to commence my investigations very soon after the crime has taken place, which often simplifies matters. With luck, I may pick up a clue that will enable my colleagues and myself to quickly get upon the track of the burglar. But let me introduce you to Detective-Inspector Martin, of Scotland Yard."

Formal greetings having been exchanged, Sexton Blake and Martin drew chairs near the bed.

"Do you feel able to give me the details of the case that are available, Sir Digby?" the private detective asked.

"Yes, yes, Blake!" Sir Digby returned quickly. "I've been badly injured, but, by James, if I were dying, I think I would use my last breath in doing all possible to help you get on the scoundrel's track! Three-quarters of my beautiful collection gone-stolen by this villain, who—"

"Do not distress yourself, Sir Digby," Blake interrupted soothingly, for a flush of colour had sprung into the old man's ashen cheeks, and he was shaking with intense agitation. "You may rely upon the best efforts of both Martin and I, and there can be no good purpose gained in your upsetting yourself. At what time did you come downstairs and find the burglar in your study?"

"Let me see! At about half-past four, I suppose it would be. I had a strange feeling that all was not well, and, just to satisfy myself, I rose and secured a revolver and candle, making my way downstairs. You can judge of the shock I received when I saw the masked man in the room. I threw up my weapon to fire at him, but he was took quick for me. He fired first, and I remembered no more until I found my daughter and Tilling—my doctor—stooping over me. I was in bed, and Tilling had dressed my wound. Mr. Blake, at all costs, whatever else you have to shelve, I implore you to leave no stone unturned to get my treasures back! I will compensate you for any loss you may sustain, pay any fee that—"

Sexton Blake held up his hand sharply.

"We are personal friends, Sir Digby," he reminded the nobleman quietly. "The question of fees need not be entered into—at least until the case is brought to a conclusion. What is the value of the stones that are missing?"

"I cannot accurately say, for I have not been well enough to check the part of the collection the scoundrel left behind him. Quite three-quarters of the collection have been taken, however, and I should imagine the thief's haul is a little less than one hundred and fifty thousand pounds in value."

"I see. Would it be possible for you to obtain me a detailed list of the stones that are missing?"

"Inspector Jones has already requested that," Sir Digby answered, "and I have promised to let him have it, although I had quite forgotten until now. Do you think you could compile the necessary particulars, Elice?" The girl looked doubtful.

"I doubt whether I could, dad," she replied. "You see, Mr. Blake"—turning to the detective—"I have been away from home practically since the outbreak of the war. Doubtlessly you have added to the collection during my absence, father."

"Yes," Sir Digby admitted, frowning. "And I have also exchanged and disposed of a certain number of stones. However, Miss Hammond could lay her hands upon the necessary lists and would be able to assist you, Elice."

"I wonder where Miss Hammond is?" Elice said thoughtfully. "It has just truck me that I have not seen her since the alarm was given."

"Humph! She must be a heavy sleeper then," the wounded nobleman grunted. "The shots that were fired roused the whole household, did they not?" Elice inclined her head.

"Yes," she agreed. "It is indeed strange that Miss Hammond was not awakened."

"May I inquire who this Miss Hammond may be?" Sexton Blake queried.

"My secretary—an American girl of remarkable beauty and intelligence, Blake," Sir Digby answered. "You had better awaken her, Elice. She will not mind being disturbed under the circumstances." The girl rose to her feet and moved towards the door.

"I think," Sexton Blake suggested, "that, with your permission, Sir Digby, we will take a look at the study. I presume the jewels were locked in your safe before you retired?"

"Yes. The safe was opened with a duplicate key. It was left in the lock."

"Indeed! It would almost seem, then, that some person in the house was in league with the thief."

"Yes; although for the life of me, I can't think who it could be. All my servants have been with me for years, and I have every confidence in their honesty."

"Have you the key to hand?"

"No; but Mr. Jones, of Scotland Yard, has it. He is downstairs still, I expect. Oh, how I wish I had hidden my collection in this room! But, there, it is of no use repining now!"

The baronet sank back feebly upon his pillows, and Sexton Blake and Martin followed Elice from the room, as she beckoned them.

"I will take you to the study, gentlemen," she said.

The two detectives followed the girl down the imposing, thickly-carpeted staircase, and she quickly led them to the room in which Sir Digby Cranston had so dramatically surprised Maitland some two hours ago.

An alert-eyed young man, with a drooping moustache of a sandy hue, a fresh complexion, and square, determined chin, turned from the safe which he had been examining. He was quietly dressed in a dark grey suit, and there was little of the detective about him, although Martin, had he been inclined to admit the truth, could have told you that Detective-sergeant Jones was one of the ablest young officials at the Yard.

A constable stood respectfully in the background, watching his superior, and he drew himself up and saluted smartly as Martin swaggered in behind Sexton Blake. Elice whispered a word of excuse to the latter and left them.

"Hullo, Jones!" the worthy official growled. "So you've been put on this case."

Jones nodded coolly.

"Yes, sir," he answered. "The assistant commissioner sent for me as soon as we received the news of the robbery, and I came straight away here."

"Humph! Have you discovered anything of value?"

"Not a great deal, at present. The robbery was well planned. The burglar came prepared with a duplicate key."

"May I see it?" Sexton Blake requested.

Jones produced the article in question, and Sexton Blake took it between his long, white fingers. He scrutinised it closely, noting that one of the wards had been recently oiled and filed.

"Depend upon it, he had an accomplice in the house," Martin said. "It's a rotten old safe, anyway. If the fellow had not secured a duplicate of the key, he wouldn't have had much trouble with it. Fancy keeping jewels to the value of two hundred thousand pounds in a thing like this, Blake!"

"It is certainly unwise, my friend," Sexton Blake admitted, as he sank to his knees before the safe and examined it closely.

"Unwise! I call it sheer idiocy!" Martin growled. "Some people fairly ask to be robbed, and we chaps at the Yard get all the trouble. Why, in the hands of a cracksman who knows his work, that safe would be as easily opened as would an ordinary sardine tin! What're you looking for? Finger-prints?"

Behind his chief's back. Mr. Jones smiled. It struck him that what Sexton Blake was doing was rather obvious. The Baker Street detective had produced his lens and was going over every inch of the polished steel door and its brass fittings.

"I am afraid you'll be disappointed in that direction, Mr. Blake," Jones said. "I've already searched for impressions, and there's not a ghost of one!"

Sexton Blake paid no heed to him until he had made a thorough inspection of the door through his lens. Then he rose, smoothed the creases from his knees, and shook his head. "Not a sign of an impression," he said. "The man escaped through these windows, I take it?"

"Yes," Jones replied. "They were open when I arrived. Save for removing the jewels that were left behind, Miss Cranston had thoughtfully left the room just as it appeared when she rushed in to find here father upon the floor. She thought he was dead at first, for the front of his dressing gown was stained with blood, as also was the carpet."

Sexton Blake glanced keenly round him.

"And you have touched nothing since?" he queried.

"I have disturbed nothing, although I have, of course, made a thorough examination," the Scotland Yard man returned.

Sexton Blake backed towards the door, and, as was his custom, he made a survey of his surroundings, nothing escaping his keen grey eyes. He saw the dark, wet stain upon the carpet, which told him the spot at which Sir Digby Cranston had fallen when he had been wounded, and in his mind's-eye he imagined how the room had appeared when Elice had first entered.

He pictured the inert form of the nobleman lying stretched at full length upon the floor, the jewels scatted about the table, the safe yawning open, and the windows ajar. He stepped over to the gas-heating stove and stood before the massive fireplace, but there was nothing in or behind it—not even a scrap of paper—that would serve as a clue.

"Have you been in the garden as yet?" he asked, addressing Jones.

"I have taken a look round," the sergeant replied, "and I have found little save that I know the exact spot where our man scaled the wall. A brick had been dislodged and lay on the mould of the flower-bed beneath."

"A flower-bed is directly beneath the wall, then? There are surely some traces of footprints there?"

"Yes. I have the measurements here," Jones answered, as he drew a notebook from his pocket. "There was a woman in the business, I imagine."

"How do you know?" Martin asked eagerly.

"There are two sets of impressions at the foot of the wall," the detective-sergeant explained. "One set were made by a woman. You can tell by the shape of the heel."

Martin sniffed.

"Of coure you can!" he snapped. "I don't need to be instructed as to how to distinguish the footprints made by a man from those of a woman."

"I was not suggesting such a thing, sir," Jones retorted calmly. "I merely explained how I was fairly certain a woman was in the case. I say fairly certain, because even the elongated heel isn't always a proof that the marks were made by a member of the fair sex. I was once taken in very successfully by a crook who purposely wore ladies' shoes when at work."

"That's nothing to do with the matter in hand," Martin returned. "We've got to catch the man who stole Sir Digby Cranston's jewels, and whilst we are listening to your experiences as a detective, he's gaining a longer start of us. When you are as old as I and—"

"Let us get into the garden and investigate," Sexton Blake cut in, and his manner was impatient, for he had no wish to listen to a passage of arms between the rival officials. "We shall learn more there than is possible here, I think."

He stepped to the windows, released the catch, and a moment later stood on the strip of path that divided the house from the miniature lawn.

Sexton Blake moved slowly over the grass, his eyes scanning the ground, but he saw nothing to interest him until he stepped behind the bushes, in the cover of which Ezra Q. Maitland had lain in wait for his wife.

At once the detective saw that the grass was crushed and flattened, and he knew that someone had crouched at the spot for a considerable time. He sank to his knees, and beneath his lowered lids his eyes were steely and bright as he picked up the stump of a match which had been partly burnt.

"Our man believed in living in style, my friend," Sexton Blake said, looking up at Martin, who was standing over him, with Detective Jones by his side.

"How do you know?" the official asked, with a frown of puzzlement.

"Because this match enables me to deduce that he was recently frequented one of the most expensive and select hotels in the West End of London," Sexton Blake answered quietly.

"Oh, draw it mild!" the worthy official grinned. "How the deuce can you tell that from the stump of a match?"

"In this particular instance, quite easily," the Baker Street detective replied. "Take a look at it. It is not an ordinary match by any means!"

The Scotland Yard man took the charred fragment of wood from his colleague. Sexton Blake had been correct in stating that it was not an ordinary lucifer. It was broad and flat in shape, and stamped in the centre were the letters "R.H."

"I don't see that it affords us much information," Jones who was looking over his superior's shoulder, said indifferently.

"On the contrary," Sexton Blake objected, "it tells me that it was once in one of the match-stands in the American or buffet bar of the Royal Hotel in the Strand. These matches are peculiar to the institution in question, they being specially made for the proprietor, who has a mania for the initials signifying his hotel to appear on practically every article in use there. The glasses, the crockery-ware, the table-linen and cutlery all bear the initials 'R.H.' in some form or another.

"It is a habit of mine to notice facts that would escape, or only momentarily impress the average person. It is fairly safe to assume that our man, when taking a drink at one of the bars, discovered he was without matches, and took several from one of the stands before passing through to his rooms or making for the street. He must have been a resident at the hotel, otherwise he could not purchase refreshment at either of the bars."

"The reasoning is sound enough," Martin admitted, "But, after all, it does not identify the man who stole the jewels. Indeed, there is every reason for it to be possible that it was not he who dropped this fragment of match."

"On the contrary, I do not think that there is much doubt about the lucifer having once been in the possession of the cracksman," Sexton Blake returned, with quiet conviction, as he took the scrap of wood from Martin's hand and carefully stowed it away in his wallet. "Look at the grass and note how it has been pressed down behind these bushes. The fact seems to indicate that the man lay here for some good while, possibly watching for the house to be wrapped in darkness before he made his attempt to steal Sir Digby's treasures."

"Or he may have been waiting for his accomplice," Detective Jones put in.

Blake nodded.

"You are, of course, referring to the woman whom you have deduced went over the wall with the man?" he said.

"Yes!"

"We will take a look at the footprints later," Sexton Blake answered. "For the present, there may be more to be found here. Phew!"

"What have you dropped on?" Martin asked, stooping eagerly forward, for Sexton Blake had given a long, low whistle. "This," Blake answered, holding up a partly-smoked cigar, which he had just unearthed from beneath the bushes.

"It's an Indian brand!" Martin said, as he took the find between his finger and thumb and sniffed at it.

"Precisely! It is a Trincomalee!"

"What!" Martin started. "The kind smoked by Ezra Q. Maitland?" he ejaculatedv oluntarily. "Jove, Blake do you think—"

"We must not jump to conclusions," the Baker Street detective protested, with a deprecatory gesture of his hands. "Trincomalees are certainly the brand of cigars smoked by Maitland and are very rare in England, but the finding of this butt here does not necessarily proclaim that the American was the burglar."

"As with the match," Jones said, "the cigar may not have been smoked by the criminal, although there's indication that it was."

"I fancy I follow the direction in which your thoughts are running," Sexton Blake said. "The cigar was thrown away almost immediately after it was ignited, which might mean that our man, supposing he was the smoker, saw that the time for him to act had arrived, necessitating his tossing the weed away."

"That's just what I was deducing, Mr. Blake. Do you think that Maitland has cropped up again in this affair? By James! It's more than likely when one comes to think of it! He's been quiet for a long while now, and Sir Digby Cranston's jewels would mean a haul that even Maitland would consider worth going for! The woman might have been his wife, eh?"

"It is more than likely," Blake agreed. "But let us prove the theory to be an actual fact before we rely upon it. Perhaps you'll lead us to the spot where the man and woman scaled the wall?" Jones nodded.

"This way, gentlemen!" said he.

He started off across the lawn, and presently paused before the wall that cut off the garden from the lane at the rear. He indicated with his foot a brick that lay in the soft mould of the flower-bed beneath, and pointed to the cavity it had recently filled.

Sexton Blake sank to his knees, quite heedless that the ground was damp with the dew that had fallen during the night. His brows were drawn together, his lips compressed, as he studied the footprints that were in evidence in the soft earth. As Jones had said, they appeared to have been made by a man and a woman, for one set was very small and dainty, whilst the heels of the person responsible for them had sunk deeply into the ground.

Blake rose and drew himself to the top of the wall with a quick, neat spring. He glanced from side to side, then once again dropped to earth and stood by his companions.

"Hallo!" Martin said at that moment. "What's wrong with Miss Cranston? She seems upset about something!"

Sexton Blake and Jones swung round in the direction in which he was looking. Elice had just emerged from the study windows and was hastening towards them in a manner that suggested something out of the common had occurred.

Her breath was coming a little sharply, and her cheeks were flushed with excitement, as she reached the three men.

"It's Miss Hammond, gentlemen," the girl answered quickly. "She has completely disappeared, and her bed has not been slept in!"

Sexton Blake's eyes glinted as instinctively he darted another glance at the impressions in the mould of the flower-bed. "I would suggest that you allow us to see her room," he said. Then, meaningly, "We have ascertained that a woman was mixed up in the robbery, Miss Cranston."

Elice, caught her breath and her eyes opened wide with astonishment.

"But, Mr. Blake," she protested, "you cannot think that my father's secretary had any connection with the man who committed the theft of the jewels?" The detective tilted his shoulders.

"We know that a woman, for some reason, climbed over the wall into the lane at the rear of the garden," the detective said, non-commitally. "Also, the duplicate key could not have been obtained by the burglar, without assistance from an accomplice in the house."

"But Sadie Hammond could have had no hand in the crime, Mr Blake!" Elice cried. "She came to my father with references from an American millionaire, and was one of the nicest of girls. We were very great friends, and I cannot for a moment believe her to be dishonest."

"Yet her sudden disappearance is peculiar, to say the least of it, Miss Cranston," Sexton Blake persisted. "With your permission, we shall take a survey of her apartment without delay."

"Of course, if you think it necessary, I will take you to her room."

"I believe it to be most necessary. Were the references from this—er—millionaire ever confirmed?"

"You mean did my father correspond with him to ascertain whether the testimonials were genuine?"

"Yes."

"I am almost sure that he did not, Mr. Blake. Dad was always a trifle lax in business matters."

"Exactly. I should not be surprised if these references proved to be forged, but we will cast no further doubts upon Miss Sadie Hammond's honesty until we have had an opportunity of searching her room. You said she was, as her name implies, an American, if I recollect rightly?"

"That is so. She hailed from Chicago."

Sexton Blake seemed thoughtful as he and his companions followed the girl back to the house and up to the first floor. Elice led them along a corridor, and paused before a door at the far end. Throwing this open, she displayed to view a tastefully-furnished bedroom.

One glance at the bed sufficed to tell the detectives that Elice had been right in stating that it had not been slept in. Sexton Blake ran his eyes over various pieces of furniture the room contained, and moved over to the dressing-table.

His eyes narrowed as he stood for a moment regarding the array of articles dear to the feminine heart which stood there. Bottles of perfume, a tiny jar of face cream, a box of rice powder, a tube of lip-salve, and an expensive box of assorted chocolates lay about in disorder.

Sexton Blake took up the stump of a tiny cigarette, but upon examination it proved to be a "My Darling" State Express, a brand that is specially sold for ladies and which could be purchased at any good-class tobacconists. Blake was about to turn away when he caught sight of a quantity of hairpins lying in an ornamental glass tray, and at once he was struck by the fact that they were of two distinct kinds.

Quite a dozen were composed of tortoise-shell, and were of an amber colour, whilst there were three of the ordinary black wire description. Blake turned to Elice.

"Your father's secretary was a blonde," he said.

It was a statement rather than a question.

"Yes, Mr. Blake. Her hair was very beautiful, and of a fair golden hue."

"Can you remember ever seeing here with her hair undressed? I mean, with it falling about her shoulders?"

"No," Elice replied slowly, after a pause. "Never to the best of my recollection."

"I rather thought not, Miss Elice," Sexton Blake said, a trifle drily. "Had you done so, you might have detected that what you believed to be tresses of natural and exceptional beauty were nothing more than a skilfully-made wig."

"A—a wig!" Elice gasped. "Why do you think that?"

"Because," Sexton Blake returned quietly, although there was suppressed excitement in his keen, grey eyes, "there is, in my mind, but little doubt that Sadie Hammond was merely an alias for Kathleen Maitland, or 'Broadway Kate,' as she is known by the police of nearly every civilised country in the world, one of the cleverest and most cunning female criminals of the twentieth century."

"Broadway Kate!" Elice seemed astounded, bewildered. "The wife of the man who attempted to steal the Great Belgian Relief Fund!" she said tensely.

"The same," Sexton Blake admitted.

"But what makes you so sure, Blake?" Martin asked eagerly. "You said just now, when you found the end of a Trincomalee cigar in the garden, that we could not be sure that it had belonged to Ezra Q. Maitland, although—"

"And since then," Blake replied, "I have secured a clue that has made me practically certain of the identities of the thieves. Let us put two and two together. We know that the secretary, who is known as Sadie Hammond, is of American origin. So is Broadway Kate. Secondly, the secretary came to Sir Digby, who, by the way, is a renowned collector of precious stones, with references that might quite easily have been forged.

"We must note that Miss Hammond would know that the jewels would be kept in the house all last night, for they were to be on view at the reception, and naturally could not be sent to the bank until this morning. Miss Hammond, in her position as private secretary to Sir Digby, would doubtless have frequent opportunities of taking a wax impression of the key of her employer's safe.