RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old print

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old print

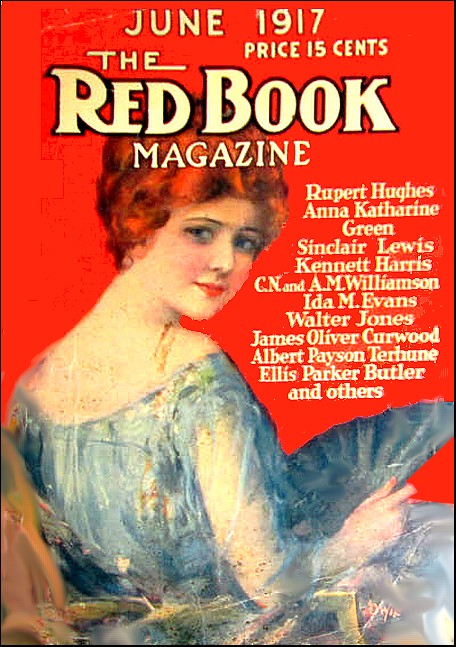

The Red Book Magazine, June 1917, with "The Ghost Patrol"

DONALD PATRICK DORGAN had served forty-four years on the police-force of Northernapolis, and during all but five years of that time he had patrolled the Forest Park section. He had seen Forest Park grow from a selvage of outskirts into a mass of streets, and he had contributed to whatever was sound and generous in that growth. And he had seen the beginnings of Little Hell, where the toughs who were not enterprising enough to stand the struggle in the downtown slums huddle in a degenerate colony of shacks and goats and baskets of stolen coal. Gradually what had been his beat became a dozen beats, and he was narrowed down to a station in Little Hell.

Don Dorgan might have been a sergeant, or even a captain, but it had early been seen at headquarters that he was a crank about Forest Park. For hither he had brought his bonny lass of a wife, and here he had built their shack, tar-papered it himself, and clapboarded it; here his wife had died, and here she was buried. It was believed that he slightly cracked about the section, but there was nothing cracked in his method of tackling a yegg, and it was so great a relief in the whirl of department politics to have a man who was contented with his job, that the Big Fellows were glad of Dorgan, and kept him there where he wanted to be, year after year, patrolling Forest Park.

For Don Pat Dorgan had the immense gift of loving people, all people. In a day before anyone in Northernapolis had heard of scientific penology, Dorgan believed that the duty of a policeman with clean gloves and a clean heart was not to club men and bring them in to the station, to secure a conviction from the magistrate or a cigar from a cub assistant district attorney, but rather to keep people from needing to be arrested. He argued with drunken men and persuaded them to hide out in an alley and sleep off the drunk. When he did arrest them, it was because they were sedately staggering home intent on beating up the wives of their bosoms. Any homeless man could get a nickel from Dorgan, and a road-map of the doss-houses. To big bruisers he spoke slowly, and he beat them with his nightstick where it would hurt the most but injure the least. Yet to little girls crying over spilled parental beer he was a gentle guardian, and the babe would go trotting off with funds for a new growler—and sometimes for a new doll. Along his beat, small boys might play baseball, provided they did not break windows or get themselves in front of motor-cars. The pocket in his coat-tail was a mine; here were secreted not only his midnight sandwiches, his revolver and handcuffs and a comic supplement for his private diversion in spare hours, but also a bag of striped candy for his youthful clients, and a red rubber ball.

Children and wife of his own he had none at all, save in Forest Cemetery, whither he went every Sunday after mass; but to a whole community he was a benign father. When the Widow Maclester's son took to the booze, it was Don Dorgan who made him enlist in the navy. Such things were Don's work—his art. Joy of his art he had when Kitty Silva, who had gone wrong, repented and became clean-living; when Micky Connors, whom Dorgan had known ever since Micky was a squawking orphan, became a doctor, with a large glass sign lettered J.J. Connors, M.D., D.S., and a nurse, by golly, to let a poor man in to see the great Doctor Connors!

DORGAN never played favorites among his children; but he did

have for one boy and girl a sneaking fondness that transcended

the kindliness he felt toward the others. They were not weak,

this boy and girl; their bones were not cooked macaroni, like the

spines of most of the crawlers in Little Hell. They were Polo

Magenta, son of the Italian-English-Danish jockey who had died of

the coke, and Effie Kugler, daughter of that Jewish delicatessen

man who knew more of the Talmud than any man in the

Ghetto—Effie the pretty and plump, black-haired and

quick-eyed, a perfect armful for anyone. Polo Magenta had the stuff

of a man in him, though he had started badly, when his widowed father

had lost his nerve and his rating, and had taken to the white stuff

and to beating Polo.

The boy worshiped motors as his father had worshiped horses. At fourteen, when his father died, he was washer at McManus' Garage; at eighteen he was one of the smoothest taxi-drivers in the city. At nineteen, dropping into Kugler's Delicatessen for sausages and crackers for his midnight lunch, he was waited upon by Effie, and desired her greatly.

Thereafter he hung about the little shop nightly, till old Kugler noticed and frowned upon them—upon Polo, the gallantest lad in Little Hell, supple in his chauffeur's uniform, straight-backed as the English sergeant who had been his grandfather, pale-haired like a Dane, altogether a soldierly figure, whispering across the counter to blushing and hot-blooded Effie. Now, old Kugler knew of Polo, as did everyone in Little Hell. Polo was a Goy, and Kugler had sworn that he would shoot Effie before he would let her marry a Goy. Also, Polo was a driver of an abomination of speed, such as threatened Kugler every time he crossed Minnis Place to call upon Rashpushkin, the cobbler and scholar. And Polo was the son of a drug-fiend.

Kugler would growl that he was a poor man, but he did not want the money from Polo's purchases, and would Polo please go away and never come back to the shop. Then for an hour he would roar at Effie, and say what he would do to her if she ever again spoke to Polo. He wouldn't have done anything of the sort, but he believed that by violence he was saving her—the child of sparse living and honest scholarship—from marrying a cosmopolitan degenerate and becoming one of the thin-blooded, wasted wives of Little Hell who furtively sneaked into family entrances to forget their husbands. Effie wept, promised not to see Polo again and went to her room behind the shop to devise ways of seeing him again—which she did.

Kugler discovered their meetings. He lurked at the door and prevented Polo from driving past and picking her up.

So Effie became pale with longing to see her boy; Polo took to straight Bourbon, which is not good for a taxi-driver racing to catch trains. He had an accident, once; he merely smashed the fenders of another car; but one more of the like, and the taxi-company would let him out. He grew sullen, and began to remember his father's mumblings about all the world being against them. Already Polo was ripe for real citizenship in Little Hell, the land of failures.

THEN Patrolman Don Dorgan, who had watched all this, or

gathered it from bootblack gossip, sat in on the game. He decided

that Polo Magenta should marry Effie, and in his simple-hearted

way he started to bring this marriage about, without consultation

either of priest or rabbi. He told Polo that he would bear a

message from him to the girl, and while he was meticulously

selecting a cut of sausage for sandwich, he whispered to her that

Polo was waiting, with his car, in the alley off Minnis Place.

Aloud he bawled: "Come walk the block with me, Effie, you little

divvle, if your father will let you. Mr. Kugler, it isn't often

that Don Dorgan invites the ladies to go a-walking with him, but

it's spring, and you know how it is with us wicked cops. The girl

looks as if she needed a breath of fresh air."

"That's r-r-r-right," said Kugler. "You go valk a block with Mr. Dorgan, Effie, and mind you come r-r-r-right back."

Effie trotted beside him, a pretty picture of a naïve lassie going out with Uncle Don Dorgan, while her heart was flame and roses with the thought that she was to see Polo.

Dorgan stood like a lion at the mouth of the alley where, beside his taxi, Polo Magenta was waiting. Dorgan couldn't help overhearing; he was no eavesdropper, but as he caught the cry with which Effie came to her lover, he remembered the evenings long gone when he and his own sweetheart had met in the maple lane that was now the scrofulous Minnis Place.

"Hello, kid," he heard Polo say, after a time, with the harshness of shy love.

"This is a dead swell meeting-place, eh? This is me new garage. Lemme introduce you to old Miss Garbage Can, me new partner."

"Oh, Polo, I'd meet you anywhere. The days have been like dead things, never seeing you nowhere."

"Gee, we're getting to be poets! On the level, kid, I know how you mean. I got to thinking you're like a sunset, one of these eight-cylinder humdinger sunsets, all fire and blood and glory. It hurts, kid, to get up in the morning and have everything empty, knowing I won't see you any time. I could run the machine off the Boulevard and end everything, my heart's so cold without you."

"Oh, is it, Polo, is it really?"

"Say, look, we only got a couple minutes. I've got a look in on a partnership in a repair-shop in Thornwood Addition. If I can swing it, we can beat it and get hitched, and when your old man sees I'm prospering—"

While Dorgan heard Polo's voice grow crisp with practical hopes, he bristled and felt sick. For Kugler was coming along Minnis Place, peering ahead, hunched with suspicion. Dorgan tried to widen out his shoulders to block the alley. He dared not turn to warn the lovers, or even to shout, for already Kugler was hurrying toward him.

Dorgan smiled. "Evening again," he said. "It was a fine walk I had with Effie. Is she got back yet?"

He had moved out into the street, and was standing between Kugler and the alley-mouth, his arms akimbo.

Kugler ducked under his arm, and saw Effie cuddled beside her lover, the two of them sitting on the running-board of Polo's machine, their cheeks together, their hands firm clasped.

"Effie, you will come home now," said the old man. There was terrible wrath in the quietness of his graybeard voice.

The lovers looked shamed and frightened.

Dorgan swaggered up toward the group. "Look here, Mr. Kugler: Polo's a fine upstanding lad. He aint got no bad habits—to speak of. He's promised me he'll lay off the booze. He'll make a fine man for Effie—"

"Mr. Dorgan, years I have respected you, but—Effie, you come home now," said Kugler.

"Oh, what will I do, Mr. Dorgan?" wailed Effie. "Should I do like Papa wants I should, or should I go off with Polo?"

For once in his life of decisions in matters that concerned life and death and imminent disaster, Dorgan was feebly indecisive. He respected the divine rights of love, but also he had an old-fashioned respect for the rights of parents with their offspring.

"I guess maybe you better go with your papa, Effie. I'll talk to him—"

"Yes, you'll talk, and everybody will talk, and I'll be dead, thank Gawd, and not have to listen to your gassing," cried young Polo. "Get out of my way, all of you."

Already he was in the driver's seat and backing his machine out. It went rocking round the corner.

NEXT morning Dorgan heard that Polo had been discharged by

the taxi-company for speeding through traffic and smashing the

tail-lights of another machine; then that he had got a position

as private chauffeur in the suburbs, been discharged for

impudence, got another position and been arrested for joy-riding

with a bunch of young toughs from Little Hell. He was to be tried

on the charge of stealing his employer's machine.

Dorgan brushed his citizen's clothes, got an expensive hair-cut and shampoo, and went to call on the employer, a righteous-whiskered man, who refused to listen to maundering defenses of the boy, declaring he would press the charge.

Dorgan called on Polo, in his cell.

"It's all right," Polo said. "I'm glad I was pinched. Course I hope they won't give me a long stretch, but I needed something to stop me, hard. I was going nutty, and if somebody hadn't slammed on the emergency, I don't know what I would have done. Seemed like I was in a snowstorm running a car I couldn't control. Now I've sat here reading and thinking, and I'm right again. I always gotta do things hard, booze or be good. And now I'm going to think hard, and I aint sorry to have the chance to be quiet."

Indeed, Polo looked like a young zealot, with his widened eyes and uplifted face; and as Dorgan left him, the officer murmured an awkward prayer of thankfulness. Dorgan brought away a small note in which, with much misspelling and tenderness, Polo sent to Effie his oath of deathless love. To the delivery of this note Dorgan devoted as much skill and loyalty as he had ever shown in the legal performance of his duty, though it involved one bribery, to get a youth to toll Kugler away, and one shocking burglarious entrance, to reach the room where Effie was locked up, a prisoner of bitter paternal love.

Dorgan appeared as a character-witness at the trial, but Polo was sentenced to three years in prison, on a charge of grand larceny.

That evening Dorgan climbed, panting, to the cathedral, and for an hour he knelt with his lips moving, his spine cold, as he pictured young Polo shamed and crushed in prison, and as he discovered himself hating the law that he served.

One month later Dorgan reached the age-limit, and was automatically retired from the Force, on pension.

He protested; he declared that he was as sound as ever, and clearer-headed than any ambitious young probationer; but the retirement-rule was inviolable. In a moment of reform sentiment, to keep political favorites from being provided with soft berths, the city council had voted that retired policemen should not be employed even in station-house and prison posts.

Dorgan had no purpose in existing, once his work was done—nothing to do but hoard his pension and savings, and rot away into honorless death. He went to petition the commissioner himself. It was the first time in five years, except on the occasions of the annual police-parades, that he had gone near headquarters, and he was given a triumphal reception. Inspectors and captains, reporters and aldermen, and the commissioner himself, shook his hand, congratulated him on his forty-five years of clean service. But to his plea they did not listen. It was impossible to find a place for him. They heartily told him to rest, because he had earned it.

Dorgan nagged them. He came to headquarters again and again, till he became a bore, and the commissioner refused to see him. Dorgan was not a fool. He realized from the change in the door-man's tone that they all wanted to get rid of him. He went shame-facedly back to his shack, and there he remained.

For two years he huddled by the fire and slowly became melancholy mad—gray-faced, gray-haired, a gray ghost of himself.

AT first Dorgan attempted to coach his successor on the beat,

but the successor was a capable patrolman, and neither needed nor

desired Dorgan's tips about the desirability of watching Bootjack

Sorolla, and of helping the Widow Flynn. He could see for

himself, he resentfully told Dorgan, and what he could not see he

could learn from his partner on the beat.

From time to time, during his two years of hermitage, Dorgan came out to visit his old neighbors. They welcomed him, gave him drinks and news, but they did not ask his advice. They had appreciated him, but there is magic in that symbol of authority, a uniform, and they were not big enough to see that Don Dorgan was bigger than his uniform.

So he had become a living ghost, before the two years had gone by, and he talked to himself, aloud.

Northernapolis was developing from a big, scattered village to a compact metropolis, as all American cities develop, and during these two years the police-force was metropolitanized. There were a smart new commissioner and smart new inspectors and a smart new uniform—a blue military uniform with flat cap and canvas puttees and shaped coats—to replace the comfortable sloppy gray coat, baggy trousers and high gray helmet of Dorgan's day. When Dorgan saw the boys in their new trimness, with backs straighter and voices more precise, he jeered; but secretly he felt that he was altogether behind the times. After his first view of that uniform, at the police-parade, he went home and took down from behind the sheet-iron stove a photograph of ten years before—the Force of that day, proudly posed on the granite steps of the city hall. They had seemed efficient and impressive, then, but—his honest soul confessed it—they were like rural constables beside the crack corps of to-day.

Presently he took out from the redwood chest his own uniform, but he could not get himself to put on its shapeless gray coat and trousers, its gray helmet and spotless white gloves. Yet its presence comforted him, proved to him that, improbable though it seemed, the secluded old man had once been an active member of the Force.

With big, clumsy, tender hands he darned a frayed spot at the bottom of the trousers, and carefully folded the uniform away. He took out his nightstick and revolver, and the sapphire-studded star the Department had given him for saving two lives in the collapse of the Anthony Building. He fingered them and longed to be permitted to carry them... All night, in dream and half-dream and tossing wakefulness, he pictured himself patrolling again, the father of his people.

Next morning he again took his uniform, his nightstick and gun and shield out of the redwood chest, and he hung them in the wardrobe, where they had hung when he was off duty, in his days of active service. He whistled cheerfully and muttered: "I'll be seeing to them Tenth Street devils, the rotten gang of them."

RUMORS began to come into the newspaper-offices of a

"ghost-scare" out in the Forest Park section. An old man declared

that he had looked out of his window at midnight, and seen a dead

man, in the uniform of years before, standing on nothing at all.

A stranger to the city told a curious story of having come home

to his apartment-hotel, the Forest Arms, some ten blocks above

Little Hell, at about two in the morning, and of having stopped

to talk with a strange-looking patrolman, whose face he described

as a drift of fog about burning, unearthly eyes. The patrolman

had courteously told him of the building up of Forest Park, and

at parting had saluted, an erect, grave, somehow touching figure.

Later the stranger was surprised to learn that the regulation

uniform was blue, not gray.

A saloonkeeper of Little Hell came to the Ninth Precinct station, crossing himself and wailing that he had "been doing a favor to a bunch of kids, letting them have a can of beer for a party," when a ghost in a shabby old police-uniform had peered through the window at the back of the back room, mournfully shaken his head and pointed a thin finger at the pail, till the saloonkeeper had fearfully driven the boys away without their beer. He had called the bartender and ventured out into the yard, but no one was there, and so he knew that one risen from the dead had made himself known.

After this there were dozens who saw the "Ghost Patrol," as The Chronicle dubbed the apparition; some spoke to him, and importantly reported him to be fat, thin, tall, short, old, young, and composed of mist, of shadows, of optical illusions and of ordinary human flesh. Also he was proven by the most reputable citizens—names and addresses given by The Chronicle, to the vast increase in circulation for one day at neighborhood news-stands—to be a myth, a hoax, a mystery, a particularly fine genuine ghost. Sometimes the Patrol was a whole squad of spooks, and once he was recognized as a police-chief who had died twenty years before.

Then a society elopement and a foreign war broke, and Ghost Patrol stories were forgotten.

ONE evening of early summer, the agitated voice of a woman

telephoned to headquarters from the best residence-section of

Forest Park that she had seen a burglar entering the window of

the house next door, which was closed for the season. The chief

himself took six huskies in his machine, and all hung with guns

and glory, they roared out to Forest Park and surrounded the

house. The owner of the agitated voice, a female in curl-papers

and a consciousness of being a highly dramatic figure, stalked

out to inform the chief that just after she had telephoned, she

had seen another figure crawling into the window after the

burglar. She had thought that the second figure had a revolver

and a policeman's club.

So the chief and lieutenant crawled nonchalantly through an unquestionably open window giving on the pantry, at the side of the house. Their electric torches showed the dining-room to be a wreck—glass scattered and broken, drawers of the buffet on the floor, curtains torn down. They remarked "Some scrap!" and shouted: "Come out here, whoever's in this house. We got it surrounded. Kendall, are you there? Have you pinched the guy?"

There was an unearthly silence, as of some one breathing in terror, a silence more thick and anxious than any mere absence of sound. They tiptoed into the drawing-room, where, tied to a davenport, was that celebrated character, Butte Benny.

"My Gawd, Chief," he wailed, "get me outa this. De place is haunted. A bleeding ghost comes and grabs me and ties me up—gee, honest, Chief, he was a dead man, and he was dressed like a has-been cop, and he didn't say nawthin' at all. I tried to wrastle him, and he got me wit' a full Nelson and got me down; and oh, Chief, he beat me crool, he did, but he was dead as me great-granddad, and there was coffin slime on his cheeks, and you could see de light trough him. Let's get outa this. I'll confess anything—frame me up and I'll sign de confession. Me for a nice, safe cell for keeps!"

The man was sweating and hysterical. His eyes bulged. He was tied firmly to the davenport.

"Some amateur cop done this, to keep his hand in. Ghost me eye!" said the chief. But in sight of the burglar's panting terror, his own flesh felt icy, and he couldn't help looking about for the unknown, for the dead that walked.

"Let's get out of this, Chief," said Lieutenant Saxon, the bravest man in the strong-arm squad; and with Butte Benny between them, they fled through the front door, leaving the pantry-window still open. Neither of them would for anything have gone back to close it. They didn't handcuff Benny. They couldn't have lost him! He tucked his hand into the chief's arm and leaped into the car; and at headquarters he held a royal court, with his tale of the Ghost Patrol, till he was requested to be so good as to step into one of the nice, new cement cells that they could guarantee to be unhaunted.

NEXT morning when a captain came to look over the damages in

the burglarized house, he found the dining-room crudely

straightened up, and the pantry-window locked.

The chief assigned young Jack Barnes, of the detective bureau, to trail the Ghost Patrol. Jack Barnes did not find the Ghost. But when the baby daughter of Simmons, the plumber of Little Hell, was lost, and the neighbors in their shiftless way tried to find her, two men distinctly saw a gray-faced figure in a battered old-time police helmet leading the lost girl through unfrequented back alleys. They tried to follow, but the mysterious figure knew the egresses better than they did; and they went to report at the station-house. Meantime there was a ring at the Simmons door, and Simmons found his child on the doormat, crying but safe, dirty with days of crouching in cellars and wagons, but with her hair awkwardly tidied. In her hand, tight clutched, was the white-cotton glove of a policeman.

Simmons gratefully took the glove to the precinct station. Thence it was sent to the chief.

The chief was a stodgy, beef-gorging, beer-valiant man, but as he held the glove he shook his head with a profound and sentimental sadness. It was a regulation service glove, issued only by the department. At first sight it seemed immaculate, but it had been darned with white-cotton thread till the original fabric was almost overlaid with short, inexpert stitches; it had been whitened with pipe-clay, and from one slight brown spot, it must have been pressed out with a hot iron. It was as touching as the gown of a poor, proud, pretty girl. Inside it was stamped, in now faded rubber stamping: Dorgan, Patrol, 9th Precinct. So at last the chief understood the identity of the Ghost Patrol. He took the glove to the commissioner, and between these two harsh, abrupt men there was a pitying silence surcharged with respect.

"We'll have to take care of the old man," said the chief at last.

Again was a detective assigned to the trail of the Ghost Patrol, but an older, more understanding man than young Jack Barnes. The detective saw Don Dorgan come out of his shack at three in the morning, stand stretching out his long arms, sniff the late-night dampness, smile as a man will when he starts in on the routine of work that he loves. He was erect; his old uniform was clean-brushed, his linen collar spotless; in his hand he carried one lone glove. For all the momentary glow of his smile, his eyes were absent of expression. He looked to right and left, slipped into an alley, prowled through the darkness, so fleet and soft-stepping that the shadow almost lost him. He stopped at a shutter left open and prodded it shut with his old-time long nightstick. Then he stole back to his shack and went in.

THE next day the chief, the commissioner and a self-appointed

committee of inspectors and captains came calling on Don Dorgan

at his shack. The old man was a slovenly figure, in open-necked

flannel shirt and broken-backed slippers. It seemed impossible

that this civilian recluse could have been the trim figure that

the detective had described seeing the night before. His cot-bed

was disheveled; his dishes sat in circles of grease on the table;

his old uniform was nowhere in sight. Yet Dorgan straightened up

when they came, and faced them like an old soldier called to

duty. The dignitaries sat about awkwardly on bed and wood-box and

pails, as ill at ease as schoolboys calling on their teacher,

while the commissioner, being a man of politics, tried to explain

that the Big Fellows had heard Dorgan was lonely here, and that

the department fund was, unofficially, going to send him to Dr.

Bristow's Private Asylum for the Aged and Mentally

Infirm—which he described as a pleasant and sociable

resort, and euphemistically called "Doc Bristow's Home."

"No," said Dorgan, "that's a private booby-hatch. I don't want to go there. Maybe they got swell rooms, but I don't want to be stowed away with a bunch of nuts."

They had to tell him, at last, that he was frightening the neighborhood with his ghostly patrol, and warn him that if he did not give it up, they would have to put him away some place.

"But I got to patrol!" he said. "My boys and girls here, they need me to look after them. Why, it's pretty near half a century I been pounding the pave. When it comes time to turn out, I got to go, like a guy's got to eat when he's hungry. Maybe the old man's just fooling himself into thinking the kids need him, but I sit here and I hear voices—voices, I tell you, and they order me out on the beat... Rats, send me up. Stick me in the bughouse. I guess maybe it's better, because if you don't, I'll hear old Pooch McGroarty, that's dead these twelve years, saying to me, 'Don, why aint you out on your beat?' and then I'll have to go. If I can't patrol, then—Say, tell Doc Bristow to not try any shenanigans wit' me, but let me alone, or I'll hand him something; I got a wallop like a probationer yet—I have so, Chief."

There was frightened sorrow in his eyes. The embarrassed committee left Captain Luccetti with him, to close up the old man's shack and take him to the asylum in a taxi. The Captain suggested that the old uniform be left behind.

When Don Dorgan arrived at the asylum shelf on which they were laying him, he was tight-wadded in a respectable old Sunday suit, with a high linen collar cutting his stringy throat, and his face redly uncomfortable from shaving and scrubbing.

The police pension-fund, with a bland violation of all rules for the distribution of the same, was paying for Dorgan's board at the asylum, and letting his own pension pile up, under the supervision of Dorgan's unofficial trustee, the chief himself, a man who had never been called "Honest Hank," or otherwise labeled as putatively dishonest.

So was Don Dorgan retired from the vocation of living and working.

DR. DAVIS BRISTOW was a conscientious but crotchety man who

needed mental easement more than did any of his patients. The

chief had put the fear of God into him, and he treated Dorgan

with respect, at first—gave him a comfortable bedroom with

carpet all over it, and two pictures, and more receptacles for

things than Dorgan even knew the use of.

The chief had kind-heartedly arranged that Dorgan was to have a "rest," that he should be given no work about the farm, such as wholesomely busied most of the patients; and all day long Dorgan had nothing to do but pretend to read chatty, helpful little machine-made books, and worry about his children.

Two men had been assigned to the beat, in succession, since his time; and the second man, though he was a good officer, came from among the respectable and did not understand the surly wistfulness of Little Hell. Dorgan was sure that the man wasn't watching to lure Matty Carlson from her periodical desire to run away from her decent, patient husband.

So one night, distraught, panting with inchoate fears, his eyes rolling with temporary madness, Dorgan lowered himself from his window, dropped ten feet, and through the sweet summer night he ran, skulking, stumbling, muttering, across the outskirts and around to Little Hell. He did not have his old instinct for concealing his secret patrolling. A policeman saw him, in citizen's clothes, holding a broken branch as though it were a locust, swaying down his old beat, trying doors, humming to himself. And when they put him in the ambulance and drove him back to the asylum, he wept and begged to be allowed to return to duty.

Dr. Bristow was nervously vexed by Dorgan's "silly escapade." He telephoned to the chief of police, demanding permission to put Dorgan to work, and set him at gardening.

This was very well indeed. For through the rest of that summer, in the widespread gardens, and half the winter, in the greenhouses, Dorgan dug and sweated and learned the names of flowers—to the people of Little Hell, flowers are altogether strangers, except upon the occasions of funerals. But early in January he began to worry once more. He told the super' that he had figured out that, with good behavior, Polo Magenta would be out of the pen' now, and need looking after. "Yes, yes,—well, I'm busy; sometime you tell me all about it," Dr. Bristow jabbered; "but just this minute I'm very busy."

ONE day in mid-January Dorgan awoke at dawn to a stinging

uneasiness. A snowstorm was blowing up, but he knew that there

was something else, out beyond the storm. His sixth sense of a

good policeman was aroused. All day long he prowled

uneasily—the more uneasy as a blizzard blew up and the

world was shut off by a curtain of weaving snow. He went up to

his room early in the evening. A nurse had been watching him, and

came to take away his shoes and overcoat, and cheerily bid him go

to bed.

But once he was alone, in silence, he was maddened with anxiety. He had to go to his beat. He looked about the room. He deliberately tore a cotton blanket to strips and wound the strips about his thin slippers. He wadded newspapers and a sheet between his vest and his shirt. He found his thickest gardening cap. He quietly raised the window—instantly into the room the blizzard volleyed. He knocked out the light wooden bars with his big fist. He put his feet over the windowsill and dropped into the storm. It caught him, deafened him. He felt about, put his back against the wall, got his directions straight, and set out across the lawn. To his thin raiment the storm would have been intolerable, normally, but he was controlled by the sense of duty which forty five years of service had matured. With his gaunt form huddled, his hands rammed into his coat pockets, his large feet moving slowly, certainly, in their moccasin-like covering of cloth and thin slippers, he plowed through to the street, down it and toward Little Hell.

Don Dorgan had patrolled in blizzards before, and with a certain heroism in his make-up there was mingled a great deal of common sense. He knew that the blizzard would keep him from being traced by the asylum authorities for a day or two, but he also knew that he could be overpowered by it. He turned into a series of alleys, and found a stable with a snow-bound delivery-wagon beside it. He brought hay from the stable, covered himself with it in the wagon, and promptly went to sleep. When he awoke the next afternoon the blizzard had ceased, and he went on.

He came to the outskirts of Little Hell. Sneaking through alleys, he entered the back of McManus' red-light-district garage.

McManus, the boss, was getting his machines out into the last gasps of the storm, for the street-car service was still tied up, and motors were at a premium. He saw Dorgan and yelled: "Hello there, Don. Where did you blow in from? Aint seen you these six months. T'ought you was living soft at some old-folks' home or other."

"No," said Dorgan with a gravity which forbade trifling, 'I'm a—I'm kind of a watchman. Say, what's this I hear, young Magenta is out of the pen'?"

"Yes, the young whelp. I always said he was no good, when he used to work here, and—"

"What's become of him?"

"He had the nerve to come here when he got out, looking for a job; suppose he wanted the chancet to smash up a few of my machines too! I hear he's got a job wiping, at the K.N. round-house. Say, Don, things is slow since you went, what with these dirty agitators campaigning for prohibition—"

"Well," said Dorgan, "I must be moseying along, John."

THREE several men of hurried manner and rough natures threw

Dorgan out of three various entrances to the roundhouse, as one

who was but a 'bo seeking a warm place to doss, but he sneaked in

on the tender of a locomotive and saw Polo Magenta at work,

wiping brass—or a wraith of Polo Magenta. The greasy

overalls and the grease smeared upon his face did not conceal his

wretchedness. He was thin, his eyes large and passionate. He took

one look at Dorgan, who was stumbling over the tracks, snowy,

blue-fisted, his feet grotesque with wrapped and ice-clotted

rags, and leaped to meet him.

"Gosh, Dad—thunder—you know how good it is for sore eyes to see you, you old son of a gun."

"Sure! Well, boy, how's it coming?"

"Rotten."

"Well?"

"Oh, the old stuff. Keepin' the wanderin'-boy-to-night wanderin'. The warden gives me good advice, and I thinks I've paid for bein' a fool kid, and I pikes back to Little Hell with two bucks and lots of good intentions and—they seen me coming. The crooks was the only ones that welcomed me. McManus offered me a job, plain and fancy driving for guns: I turned it down and looks for decent work, which it didn't look for me none. There's a new cop on your old beat—just been there a month—you don't know him. Helpin' Hand Henry, he is; nobody ever heard him spreadin' no scandal about himself. He gets me up and tells me the surprisin' news that I'm a desprit young jailbird, and he's onto me—see; and if I chokes any old women or beats up any babes in arms or spits the lady tenement-house inspector in the eye, he'll be there with the nippers—see; so I better quit my career of murder. And he warns everybody in the dump against me.

"I gets a job over in Milldale, driving a motor-truck for the Pneumolithic Company, and he tips 'em off I'm a forger and an arson and I dunno what all, and they lets me out—wit' some more good advice, which this cop sees and raises it a couple. Same wit' other jobs."

"Effie?"

"Aint seen her yet. But say, Dad, I got a letter from her that's the real pure stuff—says she'll stick by me till her dad croaks, and then come to me if it's through fire. I got it here—it keeps me from going nutty. And a picture postcard of her—say, the poor kid looks as thin as me. You see, I planned to nip in and see her before her old man knew I was out of the hoosgow, but this cop I was tellin' you about wises up Kugler, and he sits on the doorstep with a preparedness button on and the revolutionary musket loaded up with horseshoes and cobblestones, and so—get me? But I gets a letter through to her by one of the boys."

"Well, what are you going to do?"

"Search me... There aint nobody to put us guys next, since you got off the beat, Dad."

"I aint off it! Will you do what I tell you to?"

"Sure."

"Then listen: You could go away where you wasn't known, but that would keep you from a chancet at Effie. So you got to start in right here in Northernapolis, like you're doing, and build up again. 'Tis a hard job, but figger it this way, boy: They didn't sentence you to three years but to six—three of 'em here, getting folks to trust you again. It aint fair, but it is. You're jugged here till you make good, and you got to get through it somehow, like you got through your stretch. See? You lasted there because the bars kep' you in. Are you man enough to make your own bars, and to not have 'em wished onto you?"

"Maybe."

"You are! You know how it is in the pen'—you can't pick and choose your cell or your work. That's how it is now. You got to start in with what they hand you. I'll love you, though, and Effie will, and we'll watch you. Oh, boy, do you know what a big thing the love of a lonely old man like me, without no kids of his own, is? If you fail, it'll kill me. You won't kill me?"

"No."

"Then listen: I'm middlin' well off, for a bull—savin's and pension. We'll go partners in a fine little garage, and buck John McManus—the louse-hound that he is. I was just down to his place; he's a crook, and we'll run him out of business. But you got to be prepared to wait, and that's the hardest thing a man can do. Will you?"

"Yes."

"When you get through here, meet me in that hallway behint Mullins' Casino. So long, boy."

"So long, Dad."

WHEN Polo came to him, in the not-too-warm hallway behind

Mullins' Casino, Dorgan demanded: "I been thinking; have you seen

old Kugler?"

"Aint dared to lay an eye on him, Dad. Trouble enough without stirrin' up more. Gettin' diplomatic."

"I been thinking. Sometimes the most diplomatic thing a guy can do is to can all this mayor's-office diplomatic stuff and go right to the point and surprise 'em. Come on."

Polo could not know with what agony lest he be apprehended before his work was done Dorgan came out into the light—the comparative flickering light—of Minnis Place and openly proceeded to Kugler's delicatessen shop. They came into Kugler's shop, without parley or trembling; and Dorgan's face—more wind-red now than gray or spectral—was impassive, as befits a patrolman, as he thrust open the door and bellowed "Evenin'!" at the dumb-stricken pair behind the counter, the horrified old Jewish scholar and the yearning maid fired at the sight of her lover.

Round these four trivial and obviously unromantic people was the trivial and unromantic peacefulness of small cream cheeses and absurd long, solemn, mottled sausages; of beans in pots and Saratoga chips in pasteboard boxes; yet there was a shock of human electricity as that bully of souls, Don Dorgan, straightened up, laid his hands on the counter and spoke.

"Kugler," said he, '"'you're going to listen to me, because if you don't, I'll wreck the works. You've spoiled four lives. You've made this boy a criminal, forbidding him a good, fine love, and now you're planning to keep him one. You've kilt Effie the same way—look at the longing in the poor little pigeon's face! You've made me an unhappy old man. But you been thorough! You included yourself! You made yourself, that's meanin' to be good and decent as the archbishop himself, unhappy by a row with your own flesh and blood. Some said I been off me nut, Kugler, but I know I been out beyont, where they understand everything and forgive everything—except maybe the stubbornness of old men that try to claw at young lives from the grave; and I've learnt that it's harder to be bad than to be good, that you been working harder to make us all unhappy than you could of to make us all happy."

It is very doubtful if, as a matter of fact, Kugler understood a single one of Dorgan's postulates. What he did understand was the emotion of it, the charging, swooping earnestness. Don Dorgan was a professional, trained to force weaklings to do the will of the law; and now in his ridiculous wrappings, with no uniform, no shield, no club, he was more superbly the man-mastering official than ever in his life before. His gaunt, shabby bigness seemed to swell and fill the shop; his moving shadow was gigantic, as a gas-light cast it upon the shelves of bottles and cans; his voice boomed and his eyes glowed with a will unassailable.

The tyrant Kugler was wordless, and he listened with respect as Dorgan went on, more gently:

"You're a godly man among the sinners, but that's made you think you must always be right. Are you willing to kill us all just to prove you can't never be wrong? Man, man, that's a fiendish thing to do. And oh, how much easier it would be to give way, oncet, and let this poor cold, boy creep home to the warmness that he do be longing so for, with the blizzard bitter around him, and every man's hand ag'in' him. Look—look at them poor, good children!"

Kugler looked, and he beheld Polo and Effie—still separated by the chill marble counter—with their hands clasped across it, their eyes met in utter frankness.

"Vell—" said Kugler wistfully.

Effie was around the counter, in Polo's arms, moaning: "My poor boy that was hurt so! I'll make it right!"

"So!" said Patrolman Dorgan. "Well, I must be back on me beat—at the asylum... I guess that will be me regular beat now."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.