RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861-1942)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861-1942)

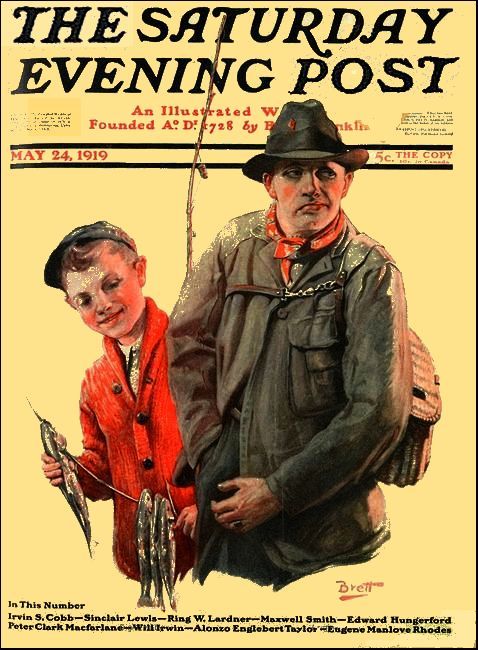

The Saturday Evening Post, 24 May 1919, with "The Watcher Across the Road"

TAFFORD curls among plump little hills, and year by long year dreaming it smiles in sleep. Twenty miles away the chimneys of Lacarose curdle the yellow air, but here are only soft sky and silver poplars and streets of old red brick. It is a place of homes.

Because he loved home, and patting the heads of horses, and talking with neighbors, better than fame among people he neither knew nor liked, Dr. Win Verity had remained here instead of becoming an association-addressing surgeon in Lacarose. He believed that in deepening peace he would stroll on to the good last sleep—that is, he believed it till the arrival of Mr. Eddie Klopot.

That event was accompanied by thunder, publicity, cyclones, preferred stock and jazz music. Klopot went from the train to the best hotel; he spoke insinuatingly to the landlord; and an hour later he was being interviewed by the reporter—who was also the city editor—of the Tafford Weekly Banner.

Two days later the Banner appeared, and on the front page it announced that after inspecting all of North America and the adjacent isles of the sea Mr. Klopot had selected Tafford as the perfect town in which to manufacture the Klopot Gasoline Farm Tractor. Klopot admitted that Tafford excelled in transportation facilities, nearness to raw materials, and low cost of living for labor.

In closing he referred with approval to the stars, the Union, Andrew Jackson, and the smiling children of contented workmen; and drew the conclusion that no matter what the knockers might say, he was a booster for the fair city of his adoption. He was here to stay. All he asked of Tafford was a neighborly hand in greeting. Within ten years the town was going to develop such pep, punch and speed that it would show its tail light not only to Lacarose but also to Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Detroit.

Doctor Verity was the unelected president of an informal club which met on the corner in front of Robinson's drug store. The members smoked pipes and told long stories, and in summer they carried their coats. After reading the Banner Doctor Verity speculated to the group:

"Transportation facilities. H'm, yes. Two cars of tractors would choke this branch line so that the superintendent would commit suicide. Still, we have one advantage: The transportation right in the town itself is all that could be asked. I can get Uncle Eben to rush my trunk down to the depot on his wheelbarrow any time—unless he has the rheumatism or doesn't feel like working. Labor conditions. H'm, yes. Excellent. No strikes here. Nobody with energy enough to strike. Near to steel—yes indeed—factories in Lacarose just full of steel; probably be glad to lend us a hatful. Well, gentlemen, before I adjourn to a small but savage game of seven-up I'll lay you a bet that inside of a week Brother Klopot will be selling stock. And every D. B. on my books will buy that stock!"

Doctor Verity was wrong.

Klopot did continue to be profuse and exclamatory in interviews, but he did not offer one share of stock for sale. It came out that he represented a company of New York millionaires. And he actually bought a large plot near the station; he actually let contracts for the construction of a plant!

Five large concrete buildings were presently being erected. It was more activity than Tafford had seen in fifty years. The town and all the fat territory about were agitated. The dairymen drove their cars into town on Sundays to stare at the walls of concrete and the windows of steel and wire glass.

Klopot had become the chief booster and almost the pioneer of Tafford. He had brought on Mrs. Klopot—a large, extremely corseted woman, who smiled anxiously and said nothing. He had rented the handsome Senator Berkins home. He invited the men to poker parties, while his wife had the women in for afternoon coffee. He joined the Order of Ravens, the Jolly Seven and the largest church. He knew every baby by its sex and every car by its ignition trouble. He contributed a hundred dollars to the funeral of Widow Durfee. He said that he was going to live in Tafford the rest of his life, and that he stood for liberty, happiness and prosperity.

The corner-drug-store club could not make him out. Doctor Verity and Alec Parsons—the veteran banker—still insisted that some day the town would come home and find that Klopot had stolen everything except the hot kitchen stoves. But less and less did the others agree with these croakers.

Smoking Klopot's cigars, recalling Klopot's handshake, they defended their playmate; and one day Dr. Nick Evans, Doctor Verity's younger rival—a gambler, a drinker, and a brilliant and homicidal performer of unnecessary operations—burst out of his sneaking awe of the old doctor and snorted:

"Oh, for heaven's sake, wake up! This town has got to progress. Don't be a piker!"

Once the club would have quaked at such impertinence to the president, but now heads nodded. Doctor Verity fumblingly put on his eyeglasses and looked about. Silently he went up to his shabby office. Here in this creaking old chair he had for a generation and more worried out not only his own troubles but those of every sick mother and every injured farm hand. He looked across the clean public square to the clean belt of sky. He pressed his hands close and sighed.

Klopot's friends began in intervals of poker games or chat in the hotel office to hint to him: "Not selling any stock, old man? Nice factory you're building."

The financier mourned: "No, hang it, I can't. I wish I could let you boys in on this. In five years Klopot-Tafford tractors will be plowing the fields of South Africa and Argentina, as well as the States. But the big interests behind me—they've got the ownership sewed up so light there won't be a look-in for anybody, unless they just happen to increase the capitalization. But I'm glad to say that we'll bring a lot of money in here when we begin to manufacture and a thousand or so workmen settle here."

Obviously he was a person of transparent truth. Were the men who were building the factory not already spending their money at the stores? But it was exasperating to think of not getting hold of good dollars from South Africa and the Argentine.

After three months of such frustration not only Klopot's nearer and dearer friends but every anxious widow in adjacent villages and every dairy farmer in the Winesap Valley were clamoring for stock. It was unjust that the monopolists of Wall Street should keep them from having a chance! Every Sunday every Taffordite walked down past the rising factory, yearned over the assembly plant, the forge house, the warehouse and offices, the paint shop, the new railroad siding, the barracks for workmen, and the macadamized highroad which cut across what had been a swamp. They foamed with desire to be part owners in these visible glories.

Their desire became a clamor when the first Klopot tractor appeared. The Banner announced the event for Saturday farmers' market day. At three o'clock Saturday afternoon a mechanical grizzly waddled down Main Street, with a nine-piece band before it and Klopot in his new sedan behind. The tractor was not too large; it was compact and quick-turning; but the huge spiked wheels gave an impression of power. It shone in green and gold, the sulky seat was gilded; and the casing of the roaring motor, high in a cage above the radiator, was of nickel and shining brass.

When it stopped and the crowd saw on the radiator plate the legend "Klopot Tractor, Made in Tafford" they felt that fame had come to their town, and that they must force the mysterious money powers to let them share that fame.

Doctor Verity, watching with Alec Parsons from the polite windows of the Parsons State Bank, was perplexed. He pointed out what no one else in town seemed to notice:

"Nice animal, that tractor, and I'm glad to learn that we could manufacture it here in Tafford. One thing does bother me though: It wasn't manufactured here! None of the machinery has been used yet in Klopot's plant—there aren't even any workmen to assemble a tractor out of standard parts."

"No, and probably never will be," said Alec Parsons. "Of course be had this built for him some place and shipped in. I doubt if there will ever be another Klopot tractor, even assembled. Why should there be? One is enough to sell stock on. Well, I guess the raid begins now, doc."

The next number of the Banner announced in a full-page advertisement that there would be a meeting of the citizens of Tafford and the surrounding country at G. A. R. Hall, come Tuesday, with free movies, and an address by Edgar P. Klopot on Do You Want to Be a Millionaire? It was a beautiful advertisement. It looked astonishingly like a market garden with a border of red and yellow cannas, and a field of alfalfa beyond, and flax in flower beyond that. It was divided into compartments, some devoted to the philosophy of will power and foresight, some expressing Klopot's gratitude to the citizens of Tafford for having so much energy and "clear-as-the-morning-headedness."

But the central plot, the asparagus and cantaloupes of the verbal market garden, was a denial that Klopot wanted "either now or, by golly, afterward" to sell any stock. He had yielded to the solicitation of his friends, and was trying to arrange it so that those who simply demanded stock might possibly have a chance to buy. He was able to murmur the good news that in answer to his pleas the directors had agreed slightly to increase the capitalization. He was wiring to New York, and hoped to be able to reserve a few shares for himself and his friends. But he could make no promises. He was frightfully afraid that the entire issue of new stock would by next Tuesday all be snatched up on Wall Street.

"Hook, bait—" groaned Doctor Verity.

"—and sinker," Alec Parsons continued.

"I'll be at the meeting. I must wake up," said Doctor Verity.

He sauntered into Robinson's drug store. He picked out the best cigar in the case and carefully cut off the end. He strolled behind the prescription counter and told the pharmacist to charge Mrs. Reverend Deems only forty cents for the prescription she would be bringing in, and to put the rest on his own bill. Then he smiled.

"Got it!" he said.

He called Central, got long distance, finally got George Arnold, in the Arnold Motor Works, in Lacarose.

Arnold was a maker of trucks and pleasure cars. He had once come from Lacarose with his wife to get Doctor Verity to operate on her for cancer of the throat. He had offered to build the doctor a hospital in Lacarose. Each year he sent the doctor a box of five hundred cigars; and each year the doctor snorted: "Now I'm not going to be a darn fool; I'm going to be selfish with these and smoke 'em all myself." And each year he managed to hold out at least fifty of the five hundred for himself—or anyway, forty.

Doctor Verity talked to George Arnold for seven minutes, and hung up.

On Tuesday evening when the doctor and Alec Parsons went to the great Klopot meeting they were accompanied by a small pleasant man with curly hair, whom the doctor casually introduced as a Mr. Arnold.

All of Tafford, most of the farmers from the valley—even a few merchants from North Tafford and Selim—crowded the hall. When Eddie Klopot elbowed through, his small red face glistening, there was a fluttering "That's him!" The sensation grew when with him on the platform appeared Doctor Verity's rival, Dr. Nick Evans; and Alec Parsons' rival as banker, Tom Curry.

There are towns in which business rivalry creates two cliques as serious as those rising from church divisions or politics. Alec always called in Doctor Verity; the doctor banked with Alec. Doctor Evans and Curry also stood together; and together in Curry's roadster they slipped off to Lacarose for what they called "a time." Evans and Curry had the advantage of youth. Now and then when Doctor Verity felt too old and tired to make a night call another good patient went to Evans. Many of the younger citizens felt that Verity and Alec Parsons were old fogies. And now when they saw Evans and Curry on the platform with Klopot they were sure that they would be able to snatch a little tractor stock away from Wall Street.

Tom Curry introduced his dear friend Ed Klopot. Mr. Klopot's speech was a good show, he amplified his garden-plot advertisement. After his seventh expression of gratitude for being allowed to live in Tafford he explained the financial situation of the company.

He confessed that formerly he had not expected to sell any stock. But he saw how unfair that would be to his neighbors. He was glad to announce that his pleas to the directors had met with partial success, he would be able to let a few people acquire small blocks.

"But," he thundered, "I want you to one and all understand that I'm not trying to sell stock. I have been surprised to learn that even in our enterprising and enlightened community there are a few knockers who go about hammering the brains and toil of their neighbors, and because they haven't had the pep and jazz to succeed in a big smashing way they're trying to drag others down—for company in misery, I suppose." (Laughter.) "Some of these—there being ladies present I can't call 'em what I want to!" (Laughter.) "But some of these pussyfooting human woodpeckers have been gum-shoeing around saying that Ed Klopot wants to stick his neighbors with bum stock! Let me tell you right here and now: If you don't want Klopot stock—don't buy it! Every share can be sold in New York. And if anybody thinks there's one single detail in my plans that even faintly resemble a fakery let him have the manhood and decency to stand up right here and now and say so, and not go sneaking round back yards, like a snake in the grass! Now come on!"

Klopot glared at the audience. Everyone stirred and looked uncomfortable. Doctor Verity began to uncoil his stooped thinness but Alec Parsons put a cautioning hand on his knee.

"Apparently, then, I have you all with me," exulted Klopot.

He plunged into a financial explanation which shone like the orange back of a new Liberty Bond. He wound up with a résumé of the advantages of Tafford as a center for manufacturing. He specialised on the fact that scrap iron could be purchased right here in the neighborhood. Every one of his friends, he said, knew of piles of broken machinery on farms; or of discarded stoves, iron shelf brackets and rusty sinks in back yards. This local supply was enough to provide the cast-iron portion of thousands of tractors. Neighbor nodded to neighbor. This was close to home. They did remember such junk piles.

And now, Klopot smiled greasily, were there any questions, before the movies?

Doctor Verity rose lean, gray, polite. How much did Mr. Klopot expect to pay for such local scrap iron, he queried.

Klopot snapped: "Ten dollars a ton, delivered."

The doctor drawled: "My friend Arnold here, who knows something about manufacturing motors, says he is now paying eighteen dollars a ton, not at the factory but f. o. b. Buffalo!"

Klopot shot back: "I'm sorry for your little friend, doc, but I'm not responsible if he doesn't know how to buy in quantity! I'll take a day off some time and teach him how!"

Everybody laughed. Before the laughter had rustled out, before Doctor Verity could go on and introduce Arnold, Doctor Evans was inquiring from the platform:

"What is the minimum percentage of profit on tractors, Mr. Klopot?"

Nick Evans' voice was as loud as Nick's silk shirts. It drowned the cheeping effort of Doctor Verity to continue. Klopot answered instantly and fully. One might almost have supposed that question and answer had been rehearsed. Doctor Verity sat down. The instant Klopot finished, the movies began; and the shaking was over.

After the meeting the town gossips drifted into Robinson's drug store. Doctor Evans was there, and Tom Curry. Curry did not show his usual smooth deference to Doctor Verity; he attacked him:

"Look here, doc, I kind of get the idea that you're against progress. I don't believe you want to see the town grow!"

They all listened. Doctor Verity answered slowly:

"Tom, you expect me to deny that. The fashion to-day is to believe that a town is blessed in proportion to the amount of smoke in the atmosphere. But I'm not going to deny it. Even if I did grant that Klopot will bring growth, which I do not grant, I still would not be interested in him. I know that lots of people like hustle, noise and smoke. All right, bless 'em, let 'em go to the big cities, and good luck. But I insist that some of us ought to have the right to live in towns that are distinguished by their quiet, their leisure. And aside from the question of what you or I want the town to be is the question of what it can be. This town has never grown much, and it never will, any more than a lot of thousand-year-old towns in Europe, because it has no economic cause for large growth. Its only reason for existing is to serve a certain agricultural district. All the spread-eagle boosting in the world won't give it water power or coal mines or a harbor. If people would recognize the limitations of a town they would save a lot of heartbreak, and waste of money and oratory."

Tom Curry broke in on Doctor Verity's lecture with a growling "Well, all right, if you want to be a knocker I'm sorry for you. Me, I'm a booster, first, last and all the time."

As he walked home with Parsons, Doctor Verity complained: "Alec, I wish I could get some one to define these terms 'booster' and 'knocker' for me. Is boosting exclusively confined to a fictitious increase of real-estate values? And Alec, I do hate to think of how the angel Gabriel is going to fail when he comes down with his trumpet and tries to make an impression on Tom Curry. Come in, Alec?"

DOCTOR VERITY found that overnight he had dropped into the class of old grouches. So he kept silence and miserably watched his people crowding to beg Klopot's selling agents to accept their money.

Within a week of the meeting a crew of eighteen clever young men had appeared in the Tafford territory, and offices for stock-selling had been opened with ice cream and eloquence. In Tafford Klopot had taken the whole first floor of the Barnes Block; had here installed the one Klopot tractor in existence, and piled a long table with extremely illustrated literature. A uniformed guide showed all visitors about the Klopot plant, where they could behold every feature of modern manufacturing except manufacturing.

Noon meetings addressed by agile and articulate salesmen, and sometimes in a benign paternal manner by Klopot himself, were staged in town. Presently there were other offices, not only in the villages of the state but also in Lacarose. Tafford was being advertised—and Tafford was happy.

No longer did people in the city say: "You come from Tafford? Where's that?" Now they responded: "Oh, from Tafford, eh? That's where they're making these Klopot tractors."

When the state securities commission made its examination of Klopot stock it was the testimony of the Tafford delegation and its lawyer which kept certain pernicious busy bodies on the commission from prohibiting the sale of the stock.

Salesmen in flivvers with suitcases full of financial poetry interviewed every farmer for fifty miles; appeared at every grange meeting, every farm auction. As soon as the novelty of having a local factory had lessened, interest was rearoused by freakish display. The one and original Klopot tractor paraded through ten towns, in the sulky seat a Turk in turban and astoundingly large blue pants, who wrapped up candy in Klopot circulars and threw it to the crowds.

And Klopot stock kept selling.

It has then estimated that within four months of the time of the first big meeting one million dollars' worth was sold within seventy miles of Tafford. But certainly Doctor Verity was wrong in muttering to Alec Parsons that Klopot and his agents would now pin the million in their inside vest pockets and depart. They must have put several hundred thousand back into the business, for the crew of eighteen salesmen was increased to forty, with a school for their instruction; and twenty more actual, tangible Klopot tractors appeared. Some of them were to be seen plowing fields along the most frequented state roads; some of them, haughty and ribbon-tied, were exhibited in the stock-selling offices; and a row of five stood in the Klopot factory warehouse, to convince doubters that the company was keeping its promises.

Neither Doctor Verity nor Alec Parsons was able to discover that these tractors actually had been manufactured in Tafford; that any of the handsome machinery at the factory had ever been used. But they did not often express this doubt. They were not popular in Tafford. The smallest boy was able to see that Verity and Parsons were knockers, were pikers, were enemies of the people. For they still declined to buy Klopot stock.

Six different salesmen had approached Doctor Verity. Some had threatened; some had begged. One had offered to give the doctor ten shares if he would buy five. It was this man whom Doctor Verity drove to the door, yelling; "You'll have to chloroform me before you get my name on your list of stockholders!"

In number the old fogies who still followed Verity and Parsons were not important, but they happened in slowly acquired wealth to represent more than half the capital in the territory. Wise old farmers kept coming to Verity and Parsons, asking their advice about Klopot stock, and the answer they got was; "Don't you think we can do all the cheating necessary round here, Mike? If you must give away your money give it to me."

To each of these doubters was sent an engraved invitation to attend another huge public meeting. It was to be addressed by a conservative old banker from North Tafford, who, it was announced, had agreed after investigation that Tafford had the best situation in the United States for the manufacture of tractors. This meeting, to be held the coming Thursday, was heralded by red-and-black three-sheets on every blank wall for miles. The posters stated, along with a great deal of other verbiage:

The Klopot Tractor Company wants to keep its stock out of the hands of the get-rich-kwick kwitters! We're here to stick and lick. We like the boys that put the sell in hustle, but to support us in our work of making TENS OF THOUSANDS of tractors, we want the wary, cagy, walk-round-and-give-em-the-double-O men, who are looking for an investment that will guarantee luxury in old age as well as slip an extra hundred bones in the weekly paypokes rite now!

Let's pay our respects to certain crabs that have been crawling round trying to queer our beloved city. Tafford is by location and inherent vigor the best burg in these here U. S. for up-to-the-split-second industry. If any hammer-heaver feels he is too good to be patriotic, if he is so jealous of the live ones that he's willing to keep our dear native town from progressing, then let him move on. We don't want him here!

The day after the appearance of these manifestoes, side by side with them blossomed others, which made the citizens stop, read, giggle and shout; 'Come here, see this, Henry!" The new ones ran:

Brer Taffordite, do you know you have a chance to make millions? Do you know there may be diamonds in Greenland?

Arctic explorers report that beneath only about forty feet of snow, ice and frozen earth, in Greenland, there may possibly be deposits of coal. And everybody knows, that both coal and diamonds are made of carbon.

Therefore we announce the formation of the

Greenland Diamond Discovery Corporation!

Do you realize that Tafford is the one perfect place for the headquarters and incidentally the stock-selling of this corporation? 'Cause why? Think it over. Tafford is cold and snowy in winter, like Greenland. Tafford land is green in summer. And lots of Taffordites wear arctics.

Come to the big meeting next Friday, and hear how patriotic we are in wanting your money. Free movies, free talk, free jazz, pep, punch.

Alexander Parsons, Prest.

Winfield Verity, Secy.

THERE were six hundred people at the Klopot jubilation at

G.A.R. Hall on Thursday, but at least a thousand at the Greenland

Diamond Corporation meeting the night after. In his speech

outlining the plans of the new corporation Doctor Verity used

Klopot's own words; and when he innocently asserted: "We don't

want your money, fellow citizens; what we want is your

friendship," then the people who had not bought Klopot stock

snickered.

When the doctor asked for questions a man who lived next door to him, and who was known to play cribbage with him every Saturday evening, rose to demand: "But look here, Mister Secretary, you people haven't found any diamonds yet, have you?"

Doctor Verity beamed. "No indeed! But we've had twenty-one of them manufactured for us in Detroit, and we're going to show them to people so that they can see what nice diamonds we'll find if we ever find any."

There was a little laughter just a rustle of it.

The next day the sale of Klopot stock in Tafford fell to one- half.

A week later Klopot's best salesmen packed and went on to the neighboring town of Selim, A week after that there was a Selim meeting to advertise the Greenland Diamond Corporation. It was led by a doctor who had graduated in the same class with Doctor Verity of Tafford.

But it was the Greenland Diamond meeting in Lacarose that roused the liveliest attention. In that city it was conducted by Jerry Jumps, the famous monologist, playing Lacarose in vaudeville. On the platform was a Klopot tractor, obtained from the motor show. No one referred to Mr. Klopot or his company, but after a pause Jerry Jumps crossed over, stared at the tractor, and in a puzzled way mused: "I was down in Tafford the other day, and the folks there said these fruit grew on trees. Ain't it wonderful what they expect us city hicks to believe?"

The most important Lacarose paper, which circulates all over Tafford County, reported the meeting with caricatures which included a view of the Klopot tractor.

In the week after that meeting not more than a thousand dollars' worth of Klopot stock sold in all of Lacarose and Tafford County.

Then a jovial open-faced man came to Doctor Verity's office, and pulling out real money he besought: "I want to buy some Greenland Diamonds stock, doctor."

The man did not look like such a complete idiot as to have taken the joke seriously.

The doctor smiled, shook his head: "None for sale."

"You see, to tell the truth, I think there may be something to your scheme. Could work the Greenland coal, and—uh—and the diamonds under big glass sheds, even with a fifty-below temperature."

"Nope. No stock for sale," grinned the doctor.

The man left his office, grumbling. The doctor telephoned down to the drug store. The younger clerk of the store followed the jovial-faced inquirer, who went round the corner and spoke to a man in a sedan. The man in the car was Eddie Klopot; and with him was a police officer. The jovial-faced man seemed disappointed; Klopot seemed furious.

When Doctor Verity had this report from the drug clerk he looked over a legal memorandum made out by Alec Parsons before the state securities commission had authorized the sale of Klopot stock. It was to the effect that in that state the penalty for fraudulent stock selling was from one to ten years in the penitentiary. "Glad I restrained my tendency to be a joky old thing, and didn't let our friend have any stock," sighed Doctor Verity.

Just after the rumor that Klopot stock had entirely stopped selling in the county Klopot himself came to the doctor's office.

"Well, doc, you think you've got us. I admit that the boobs who won't listen to arguments will listen to burlesque. But I have one trick; I can do one thing that will start my stock booming again and make a darned fool out of you. Want me to do it; or will you quit kidding my company?"

"Do something dreadful to me, Eddie? Go ahead and do it," crooned Doctor Verity.

"All right, I will," said Klopot. He did.

Distressing news came to the doctor and Alec Parsons. They jumped into Alec's flivver and hustled to the Klopot plant. They saw forty or fifty workmen with bundles and telescopes get out of the train from Lacarose. They saw carloads of pig iron. They saw smoke coming from the beautiful but hitherto purely decorative chimneys of the factory. They heard a crashing from the forge house.

Doctor Verity muttered: "Klopot is actually going to make tractors! He isn't going to run away! He's done the one vile trick that I didn't think any consistent crook was capable of! He's turned honest! Alec, you and I will have to leave town!"

FOR more than six months the Klopot Tractor Company had been manufacturing tractors. It is true that they weren't much like the original models that had been displayed. But Klopot explained in advertisements that he was "conducting epoch-making experimentation in increase of tractive impulse with decrease of fuel-consuming factors." It is true that, where actually used by misguided persons for prosaic tasks like harrowing or running a silage cutter, the new machines showed sullen natures, and a tendency to strike in the middle of the morning. But it must be said that Klopot kept repair men ready to rush out and give free service. It is true, according to Alec Parsons' analysis of the financial statements of the company, that, allowing for overhead, each tractor was selling at about ten dollars less than cost.

And Klopot was making no effort to sell stock. It could be bought, but he had dismissed his salesmen, closed his branch offices, turned all his interest to manufacturing.

Only Verity and Parsons held out against him, and after six months of edifying industry at the factory Parsons said to Doctor Verity: "We must give him credit. Perhaps he really has turned honest. Perhaps he will put the shop on a paying basis."

"Nope," the doctor insisted. "People don't turn honest; not overnight, anyway. They either are honest or they aren't. And yesterday I noticed that a couple of the stock salesmen are back in town. He'll have a new campaign, and it'll be a terror. Why, Alec, there won't be any money left in town for me to win at cribbage; and then what will I do with my evenings? He's taking plenty of time, and when he does start—it will be the end. No one will listen to our Greenland Diamond joke, now that he's been manufacturing. I do want to be just to Klopot. If the town really were prospering in manufacturing I'd just cuss and move out to my farm, but the junction delays on this crooked branch line would kill all transportation, to say nothing of costs. No, what would be a good use of his plant—the only one—would be to turn the buildings into a technical school, beginning of a college. Tafford would make an excellent college town. Come, let's get started mischief-making before Klopot does, Alec."

The doctor went to New York the next day. He was vague in his information to the Banner reporter regarding his reason for going.

In New York he called on a national association of advertisers and advertising agents, an organization that had fought as hard for the exclusion of fraudulent advertising as for the extension of honest advertising. Yes, the secretary said, they had noticed the activities of Mr. Klopot. No agency would handle his account.

Doctor Verity offered out of his much-nibbled fortune to pay the cost of having Klopot's earlier record dug up. The secretary refused. The association would be glad to do that work, he said. In fact— He called a stenographer and dictated telegrams to certain advertising men and credit men in points as distant as St. Louis and San Diego, Seattle and Jacksonville.

Twelve days after Doctor Verity had returned home he received the biography of Mr. Edgar Klopot. Mr. Klopot had never been in jail. He had apparently never used an alias except possibly in 1902, for which year his activities had not been discovered. He had always been adjudged not guilty. Yet as Doctor Verity read he whistled between his teeth, and admired: "The man is a wonder!"

KLOPOT was enjoying himself. The Tafford county grand jury had refused to bring an indictment against him. The agents of the post office and of the state securities commission had said ugly things, but they had not been able to touch him. He had shut up that meddling fool, Doctor Verity. And for the first time in years he was pausing before the final cleanup to play at being a solid manufacturer, a person of importance.

He was popular. Klopot stock had paid two big dividends. Or course it would never pay any more of them. Already Klopot was reassembling the stock-selling crew for the fireworks—after which, he thought, he would try the Isle of Pines. But meantime he was beloved by the widows and orphans and viewed with awe by the business men. His car was always waiting. When he rushed to the station, into the hotel restaurant, people muttered "That's Klopot." Telegrams and long-distance calls were always coming to his office. Even his stenographer took him seriously, and she was unusually pretty. She wore his roses to dances.

It was that stenographer whom he heard outside his private room arguing with a man: "Job? Factory work? Then you see the employment manager; next building, second door on the right. You mustn't bother Mr. Klopot."

"Oh, Klopot will want to see me. He's an old friend of mine. He'll give me a job. I'll wait. I just love waiting," a man's voice answered the stenographer.

Klopot prickled. That voice was familiar. He darted to the glass partition and peeped out. He knew the man—a narrow- headed person with a long jaw. He had been Klopot's associate in the flotation of worthless notes through a chain of country banks controlled by a trust company. For Klopot he had gone to jail. He was decidedly not a man to take a job as laborer. And he was not a man to wait willingly. What was the fellow's game? Why was he so leeringly good-natured?

Klopot sat crumpled, trying to make out the trick. He could not endure it. He rushed out, pushing his stenographer aside and faced the narrow-headed man. The man did not rise from the bench in the outside office. He sat and smiled, and his smile made Klopot more uneasy than shouted abuse.

"This is Mr. Klopot, isn't it?" purred the narrow-headed one.

As though he didn't know! As though he hadn't sat with Klopot in a hotel bedroom till four and five in the morning smoking many cigars, drinking many sharp nips or whisky, planning ways of capturing honest small-town banks for their chain. What the deuce did he mean by the question?

"Yes, yes! What can I do for you?" Klopot fenced.

"I just want a nice little job; nice honest one—pushing a wheelbarrow or tending a machine or something."

And he wore spats, and was recently manicured!

"Cut it out, Pete! What do you want? If you think you can make me come across—"

"How you do misjudge me, Edgardus! I want honest labor. Sweat- of-the-brow idea. My, how I admire the art of manufacturing! And I adore dear li'l Tafford. I want to stay here all my life. It's one swell distributive center."

The narrow-headed man smiled like an oversentimental woman; nor would he drop his pose. He insisted on getting work as common laborer—and he got it. With a contentment that was sinister he showed up in the yard, in overalls, to help load tractors on flat cars. He betrayed the fact that he was not broke by staying not at a workmen's boarding house but at the best hotel in town. When he encountered Klopot in the lobby the clumsy idiot pretended not to know him. From the window of his private office Klopot watched him for four days, watched him glance up grinning.

And at each grin Klopot repeated: "Now what is the game? I can't figure it out. He didn't try to sting me, and he didn't hit me for a white-collar job. Only thing I can see—he must have turned stool pigeon. Now what can he get on me?"

Every time his stenographer entered the room these days Klopot looked up, twitching, heart pounding. He put his private books away with extra care each evening, and jumpily as a man weakened by overwork he returned from his car to make sure the safe was locked. All the way home he tried to convince himself that the safe was in no danger. The narrow-headed man was an admirable forger, but no yegg. When he reached home every tiny crackling noise in the big rococo house made him rigid with dread.

After a week he was keeping himself only by force from rushing down into the factory yard to ask the spy what he would take to get out of this.

Klopot was getting a little comfort out of ordering an English mutton chop at the Tafford Hotel when he realized that the waiter was new to the place; that he had seen the waiter before; finally that this was the waiter who had been a club servant in San Antone when he had been planning the oil-field deal. The fellow had listened to Klopot's conferences at lunch at the club, there, and had later testified against him at the trial. Only by a technicality had Klopot escaped jail that time. How the deuce had the waiter got here? What was his game? He was pretending not to know his victim. When Klopot shakily gave his order the waiter said nothing but "Yes sir; mutton chop, potatoes O'Brien," before he trotted off.

Three minutes later Klopot cautiously turned and looked back at the service door. The waiter was standing by it, gazing at him and smiling.

The recently returned captain of the stock-selling crew dropped in to whisper to Klopot about working the racket of exchanging stock for Liberty Bonds. Klopot twisted about. The treacherous waiter was edging toward the table.

"Shut up, you fool!" Klopot snapped at the salesman.

"Why? What's the idea?"

"Will you close your trap!"

Klopot jumped up, leaving a two-dollar bill on the table. He glanced back from the door. The waiter had picked up the two- dollar bill. He was grinning—a contemptuous grin, of exposed teeth and creased brow and deep cheek wrinkles.

Late that afternoon glancing into the outer office Klopot saw his trusted private stenographer whispering to the narrow-headed loader of flat cars—ex-forger, ex-passer of the queer, ex- discounter of fraudulent notes. As Klopot watched them his hands trembled so that he had to grasp the door to keep them still.

When the man had gone Klopot called in the stenographer, but he was afraid to ask what he longed to ask. He couldn't seem to put words together. It was not till after half an hour of agonizing attempt to be brusque and casual about dictating letters that he managed to fling out: "What did that workman want—fellow that was in here little while ago?"

"He? The fresh thing! He wanted me to get the cashier to let him have two-dollar advance, and then he tried to jolly me. He was kind of funny though," said the stenographer, brightly, innocently—much too brightly, much too innocently.

Was she in it too? And what was it? Why, why, why did they take so cruelly long in springing it? He could have stood off a demand for blackmail a week ago, but now he felt weak, confused. And was it just blackmail? They were all laughing at him!

When the stenographer was gone there slunk in on him a feeling that someone was there, hidden in his private room. He rushed to the wardrobe, looked behind the files. No one. He dashed out to his car for a drive and fresh air.

A man was standing across the road from the factory. Klopot only half noticed the man, but as he drove on his subconscious mind kept worrying over some half memory. He simply had to return to the factory to look again at the loiterer. Why should anyone stand there, with nothing to see but the walls of the office building on one side of the road and a swamp on the other?

"Uh, Jim!" he called to his chauffeur. Jim turned round. He looked as though he was trying to keep from smiling. What did he mean by grimacing that way? Klopot stared at him helplessly. Jim too?

"Yes sir?" demanded the driver, slowing down.

"Oh, nothing. Go on," stammered Klopot.

He did not sleep well that night. From four of the following morning till eight, lying restlessly in the vast ugly bed of brass and painted iron, he waited till it should be time to rise and hurry to the factory, to find out about that unplaced man who had been waiting across the road from his office. It is one of the minor mysteries of living that after being agonizingly unable to sleep at a time when you should sleep you should doze off just at the time when you ought to get up. From eight till nine Klopot napped tranquilly, and after a mighty breakfast instantly served by the cowed maid and the plumply timid Mrs. Klopot he felt so rested that he was certain that his fancy about the watcher across the road had been silly nervousness.

He was merry as a hound pup when he climbed into his car. What a fool he had been to distrust his driver! No one could have said "Good morning" more normally than did Jim. The bulk of the factory buildings thrilled Klopot. He had done a big thing! Almost a shame that he'd soon be making the clean-up and skipping off with a million or so. Almost like to go on being honest. Cut it, now! No sappy sentiment! Isle of Pines—Costa Rica—

Down the road ahead loitering by the scum-filled marsh across from the factory was standing the man whom he had half noticed on the evening before.

Klopot crawled from the car like an old man. He most carefully did not look at the watcher across the road. He stumbled up to his office.

The windows of his private room faced the factory yard. From them while he was yanking off his light topcoat he saw the narrow-headed loader of flat cars glance up derisively.

The windows of the outer office gave on the highroad. Klopot crept out and looked down at the watcher by the swamp. After a moment he recognized the fellow. Klopot had seen him only once before, but that had been an interesting once. The watcher was the detective who had arrested him in Tacoma in the chain-store swindle. The detective stood down there, idling, then paced three steps to the right, three to the left and at each turn he peeped up at the office windows.

Once he crossed the road and for a moment talked with Klopot's driver, loafing on a box in the sun.

Suddenly, without apparent connection, Klopot recalled having heard a motorcycle following his car the evening before. His mind seemed to boil over with intolerable hot fear.

He yelped at his stenographer: "Called to Lacarose! Just time to catch the ten-five train." He darted into his private room, flung his coat over his shoulder, put his hat on askew, banged downstairs, crazily beckoned to his chauffeur, and shouted loud enough for the watcher across the road to hear: "Hustle, Jim! Give her the juice! Called to Lacarose. Got to catch Number Four."

Behind his car he heard a motorcycle. He looked back. It was the watcher.

He peered out from the parlor car on Number Four and saw the watcher on the station platform. Apparently the fellow was not taking the train. He was writing something on a sheet of yellow paper rested on a window ledge. Klopot could see that the yellow paper was a telegraph blank.

Klopot left the train two stations down the line, hired a motor, went cross-country to a junction, took a western express, left it after four stations, took a train for Buffalo, arrived there in the early morning, very cold, sleeplessly tired.

He was not quite sure, but he thought that a heavy, meaty man, a detectivelike man, stared at him rather hard in the Buffalo station.

He went to a hotel. He undressed wearily. He could scarce undo buttons; and to untie his cravat was thumb-pinching agony, during which he closed his eyes and swayed on his feet. But the moment he was in bed he was shaken into wakefulness. He could hear a rustling. He could not endure lying defenseless. He got out of bed, shivering bitterly in the late-night chill, and in the darkness sat hunched up on the edge of his bed.

He drew nearer to him the small water carafe on the bedside table. It was a sort of weapon.

He was sure that he heard the knob of the hall door turning. He dared not rush to open the door, look out. His shaky fingers crept toward the bedside lamp.

When the room flared out in light and was revealed as commonplace and solid and unmysterious and seemingly warmer he felt safe. But he could not go back to bed.

He slowly dressed and went downstairs. The night clerks stared at him—this man who had come in at four A. M. and now at five was up again. One of them whispered to the other.

What, Klopot wondered, had he whispered? Why had the other smiled?

Though he was burning-eyed and staggering he walked, walked, walked. Every policeman glowered at him—and at last one of them started to speak to him.

Klopot was glad.

Thank the Lord, the horrible waiting was over! But the policeman said only, "Kind of chilly."

At six Klopot crept into a cheap lunch room for breakfast. A man came in just afterward and ordered wheat cakes rather ostentatiously. He had a mustache, but otherwise he was curiously like the detective who had stared so hard in the Buffalo station. And the mustache was ridiculously black and trim. Wasn't it false? In the midst of his breakfast Klopot gave it up. He was beaten. There was no use in trying to escape. He would go back home and take what was coming to him.

He arrived in Tafford at eleven that night. The fact that he had stopped struggling had let him relax and nap through all that day's ride, careless of possible watchers and spies. He felt rested, and after a snarly good night to his wife he went coolly to bed.

In the morning he had a new reserve of strength. Let 'em follow him! Let 'em arrest him! A crack lawyer had gone over the articles of incorporation of the tractor company, and all stock- selling methods. No one could touch him till after the cleanup—and then he'd be abroad.

He was almost polite to his wife as they dressed in that huge bedroom, with its gilded vases, its toilet articles of ivory decorated with violets, its chintzes of huge red birds perched on blazing emerald roses. She was moved to mention her domestic business.

"I've had such a time since you went away!" she groaned. "What's trouble?"

"Lizzie left us, and I thought she would stay with us, she was such a good maid. But oh, I was so lucky. I got another maid right away—Miranda. She's even better than Lizzie. Doctor Verity sent her to me."

"He did? Don't know's I want any hired girl that that old grouch would send us!"

"Oh, but you'll like Miranda. She's the best cook! My, you just wait and see what a nice breakfast you'll have!"

Klopot felt safe, content. As he reached the breakfast table the paragon Miranda was bringing in the coffee urn. And he knew Miranda. And she was not Miranda. And she was not a cook.

She bobbed to him as though she had never seen him before. She went silently out to the butler's pantry. But Miranda was named Mary Deakins, and she was the daughter of a man whom Klopot had—well, a fellow whom he had rather neatly done out of half partnership in an aviation engine company, in K. C..

The fury of fear stiffened him. He wouldn't stand this sneaking pursuit! He'd fight! He sat straight and ate breakfast as though he were devouring his enemies. After it he stalked out to the pantry. Miranda was washing dishes. She looked at him mildly.

"Well?" he snarled.

"Yes sir?" politely.

Oh, he couldn't stand this silly make-believe! She was going to pretend that he was mistaken in recognizing her. He was too tired to play at games.

"Just want a glass of water," he said.

"I'll get it, sir," she said, much too obediently. While she brought the bottle of spring water he tried to find something to say. There was nothing.

As he rode down to the factory he heard a motorcycle behind his car and saw that on it was the man who had been watching the factory from across the road.

The salesman who was to head the new drive on stock was waiting for Klopot at the office; and he gushed: "Tried to get you all day yesterday, chief. We better start the slaughter right away. What's the use of holding off?"

"Don't bother me. I can't think about it this morning," said Klopot, peeping out of a window of his private room.

The narrow-headed man was not in sight, though a flat car was being loaded. His absence bothered Klopot more than his grinning presence had.

The salesman was insisting: "We got to think about it, chief. I have plans for—"

"You and your plans go to hell! You get out of here!" bawled Klopot feebly.

He was frightened to find now trembly he was as he crawled to his desk chair, supporting himself by the edge of the desk. His hands rattled on the chair arms, his jaw shook loosely, his spine seemed to creak in his quivering back. He got hold of himself, but he could not work. He was waiting—and he did not know what he was waiting for.

In the middle of the morning his stenographer breathed at the door: "Man to see the telephone."

She was followed by a person whom despite his ridiculous disguise of overalls and cap pulled low Klopot knew as the detective that had been watching across the road. The fellow pretended to be testing the telephone. He tapped the base of the desk instrument with his pliers, and looked at the end of the receiver in the most sheepish way. Evidently he knew nothing about phones. And he kept glancing about the room, noting files, safe, desk drawers, windows.

"Love of Mike, do they think I'll fall for as old a trick as this? It had whiskers on forty thousand years ago!" Klopot raged. He sprang up, shook his fist, demanded: "Cut out the melodrama stuff, you boob! What do you want? Spring it! Any papers I can get you? Don't mind me, old chap!"

"What do you mean 'what do I want'? I'm from the telephone company. Something the matter with your line."

"Cut it! Cut it! Who are you shadowing for? Let's get down to cases!"

"Say, boss, do you get these brain storms often? You better see Doc Verity," growled the detective as he gathered his tools and swaggered out.

Doctor Verity! It was Verity who had sent the bogus Miranda to spy on him at home; Verity who had started the Greenland Diamond joke. The detective certainly had given Verity's game away!

Klopot locked the door, and for hours he brooded, till Doctor Verity's good nature had in his imagination turned to devilish cleverness.

It was late that evening when Klopot rang at Doctor Verity's door. The doctor admitted him, led him down a dingy hall to a room of shabby wall paper, an ancient black-walnut escritoire, a table with a hand of solitaire* laid out. Klopot fancied that the doctor had smiled at the door. He was desperately warning himself: "Now be careful, boy. Don't give yourself away, 'case the old fiend isn't really in on this." But he knew that he was too nerve-twitching to be careful.

"What is it, Mr. Klopot?" condescended the doctor.

"I've had enough."

"Enough of what?"

"You know."

"I really don't understand."

"Look here, doc!" Klopot was panting, begging, his hands out. "What do you want? What have you got?"

"I have rye, and Scotch, and I guess I could dig up a little apricot brandy; though since prohibition I don't—"

"Oh, please! Why do you want to torture me? Where did you find Miranda?"

"Miranda? Who is she?"

"Look here, doc; if I liquidate right now, and somebody, say, in Lacarose, takes over my machinery and raw materials and finished tractors, and the buildings bring anything like a fair price, the stockholders won't lose hardly more than ten rents on the dollar. I'm ready to be good. I'll talk fair if you will. What've you got up your sleeve? Who was the dick in the station at Buffalo?"

The doctor seemed to be relenting; to be admitting his knowledge of the pursuit. He smiled and settled in a big chair. Klopot sat down. If he could only win over this man—

"Who do you think the Buffalo man was? Mean to say you didn't recognize him?" chuckled the doctor.

"No, I didn't. I could make the others all right; but not him. Was he in the Oregon chemical case? Look here! They cleared me absolutely on that!"

His inner self kept shouting "Oh, be careful!" but he did not listen. If he could only win the doctor, make those eyes under the heavy brows smile again!

"No," yawned the doctor. "He wasn't in the Oregon case. You had a good line of defense there. But have you forgotten about the one year when you were so clever and managed to keep out of sight? That was pretty smart, what you put over then! How about the year 1902? Say 'long about April of that year! Let's see now: What was the name you used that year?"

"That's my business, doc!"

"Oh, all right. Good night, Mr. Klopot. By the way, are you going up by the depot? I want to get Jim—mean to say, I'd like to have your chauffeur send a little message for me, to—uh—to Buffalo."

"Quit! I'll be good. But don't think for one minute you can kid me into believing you know one darn thing about the Newfoundland fisheries deal or that you can show I was John Jefferson. Might just as well drop that. Now what do you want? What are you going to get out of this? Don't spring the love-of- the-dear-community stuff on me!

"I'll make it worth your while to work with me instead of against me. And I don't mean just ten thousand or so. I mean hundreds of—"

Klopot stopped, staring. From the adjoining room a respectable-looking man in a black derby was emerging. He held a pair of handcuffs. He was the man who had been watching from across the road.

He was droning: "That'll do it, doc. That's what we needed—what he was up to the year we lost track of him. So he's John Jefferson! Friend Jefferson is still wanted in Canada. We can put this bird away for five years!"

Klopot opened his mouth several times before he said feebly to the doctor: "You think you're a smart little sleuth hound, don't you?"

Doctor Verity smiled. "You do me too much honor. What you had after you was all of the big advertisers of America. And, Klopot, do you want to know who the detective in the Buffalo station was? Your conscience! We haven't had a single agent outside of Tafford! We let you create your own shadows. And you'll be delighted to know we didn't have one single definite thing on you till this moment, Mr. Jefferson! Don't you think it would be a good joke to name one of the buildings Jefferson Hall when we turn your factory into a technical school? Take him away, please. I want to finish this solitaire before I go to bed."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.