RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

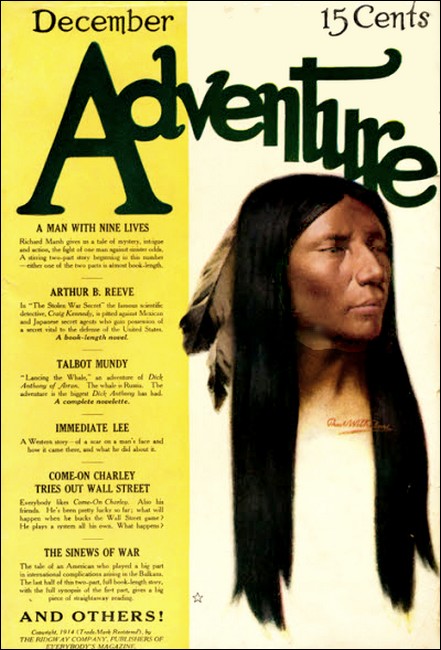

The eight stories in this series were first published in Adventure in August, September, October, November and December 1913, and in January, February and March 1914.

Severely abridged but well-illustrated versions of the stories appeared as a serial in The Washington Herald in December 1915-January 1916. RGL has published these in one volume under the title The Thrilling Adventures of Dick Anthony of Arran.

Adventure, Dec 1914, with "The Lancing of the Whale"

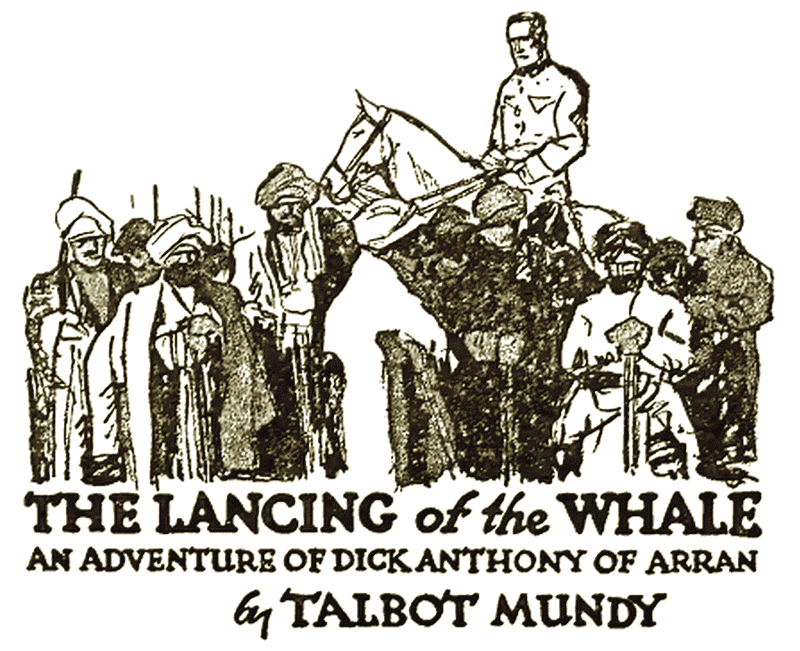

Headpiece from Adventure, Dec 1914

DICK ANTHONY surveyed a sun-baked plain, and knew his victory to be a Pyrrhic one; but, unselfconscious to the last degree, he happened to be chiefest of the men—in the true, tremendous meaning of that word—to whom danger was never more nor ever less than notice to put out their utmost. Russia had wronged him for her own ends; he had hit back hard at Russia, careless for his own wrongs, but mortified by Persia's, and now twice running he had taught Cossacks how defeat feels; but in that minute, as he watched the stricken enemy slink off toward the sky-line and knew there would be vengeance later on, he no more feared the future than he thought of flinching from his own half-drilled rabble.

He was possessed with the same quiet piety that seems to have marked most great leaders. His only fear he ever seemed to know was that perhaps he might not do his duty; but he was no vain visionary; when he dreamed dreams and loosed imagination's rein, his habit was to work and fight until the dreams came true. He could recognize grim fact, and was too hard-headed to ignore it. He admitted to himself now that his two quick victories within a week meant little more than two spur-marks on Russia's hide—very little more than two sure fighting-cues. Russia still held all the lines of communication with the outer world, and all the arteries of news; Russia had six million men to his three thousand. Russia had money—statesmen—influence—and all the hidden power of a huge political machine.

He had to stir himself if he was to save Persia from the Russian yoke! This last success was likely to bring men flocking to his standard; but the East is the East still, and the first reverse would set them deserting again in droves. Action, and only action—swift, unexpected and well-planned—could help him or Persia, But then he was a man of action, first and last.

"Back to the hills!" he ordered, shutting his binoculars away and gathering his charger's reins.

Russian dead and wounded lay scattered over two square miles of plain, and the walled city of Astrabad lay helpless for the taking; but shrewd calculation underlay his order for a prompt retreat. To have loosed his men now, with leave to plunder, would have wasted time and have forwarded no cause but Russia's. In the end he believed that his appeal would lie to the outer world, and he meant to give that world no good excuse for listening to Russia's lies about brigands in North Persia and the dire consequent necessity for Cossacks to protect foreigners and foreign country.

His ragged line stood still gazing in wonder at him in the flush of his new success, gaping belief, now, more than ever of Usbeg Ali Khan's wild story, that made him Alexander of Macedon reincarnated. But he cantered down among the spaced-out companies, letting the sunlight flash along the blade of his strange jeweled claymore, and his voice was like the cracking of great whips, as he made his will known, his seat in the saddle that of a man who is obeyed.

"Back!" he ordered. "Back to your hills again!"

"Plunder!" they murmured. "Let us loot the city first!"

They only asked leave to do what Cossacks in their place would probably have done without asking leave at all and what Persians have always done since history evolved from fable; they asked blood for blood—loot for loot—vengeance for vengeance—payment for ravished homes. And they were backed in their demand by Usbeg Ali Khan, the Afghan gentleman-adventurer, who thought no victory complete without its logical corollary.

"Let them loot, bahadur!" he advised, riding up to Dick's side. "What other payment have they for their services? Let them pay themselves, as the custom is; then, exact full credit for it, and work them the harder afterwards!"

Dick wheeled on him, spinning his big horse in one of those swift movements that were as disconcerting as they were characteristic For a moment two chargers pawed the air, and Usbeg Ali Khan believed his hour had come, for Dick's eyes gleamed strangely and his jaw was set hard; the Afghan had not quite learned yet to recognize the sign of reached decision; he mistook it for cold anger on occasion.

"I made you second-in-command! What are you doing here? Take the left wing and answer for your men's behavior! Join your command, sir!"

He made a sweeping gesture with his claymore toward a half-mile line of men, and his words were loud and clear enough for half of them to hear, for his voice crashed and reverberated when he had roused himself for action.

"The whole line will retire!" he thundered. "Usbeg Ali Khan will lead the rear-guard!"

Without another word he spurred to the far end of the other wing where his seven hundred horsemen were drawn up and Andry Macdougal leaned, swearing soft, endearing oaths at the machine-gun. The thing had answered to the big man's touch that dawn like magic, dealing death by wholesale, so—since his heart was like a little child's in most things—he all but wept his admiration for the thing.

"Where awa'?" called Andry. "Where awa', Mr. Dicky?"

Dick reined in, and the huge man laid a hand on the charger's withers.

"Back to the hills, Andry. Are your men in hand?"

"Ou-aye!"

The great, grim Scotsman turned to look at what he called his "thirty yoke o' humans," and they seemed to come to life beneath his gaze.

"Man—Mr. Dicky—they think I'm the de'il—an' when I luke at yon dead Roosians I'm no' sae verra sure the chiels are no' recht! They'll do what I say or I'll prove I'm a de'il, an' they ken that verra weel! Aye! They're certainly in han'!"

"Then lead the way! Lead off with your gun! Back along the way we came!"

"But—Mr. Dicky—"

"What?"

Dick's eyebrows—generally level and at rest—began to rise impatiently. When a man knew the meaning of discipline, he seldom cared to accept less than the real, quick, ready thing from him.

"About Marie?"

"Marie who?"

"Man! Her that's waitin'-wumman on the Princess yonder!"

Dick scowled at the horizon, A cloud of dark dust curled and eddied above a low hill and stampeding Cossacks; beyond the cloud, he knew, was the Princess who had interfered and played with him, until he was outlaw who had once been a proud Scots gentleman. It was only human to connect the Princess and her maid together in one comprehensive loathing, and to forget for the moment that the maid had fallen victim to Andry's gargoyle charms—that she loved the huge man—and that she had already given proof of her devotion.

"She's helped us, Mr. Dicky, an' she'll help again. We ought to send a mon to keep in touch wi' her—some lad wi' brains, who'd spy an' run messages."

"No," said Dick, smiling as he mentally compared the gnarled hard-bitten six-feet five beside him with the little French maid's inches. He was no ladies' man, whatever Andry might be. "If she loves you, she'll prove it. She'll either come to you or send a message. We'll put her affections to the test. Get your gun away!"

"Na-na! She's affectionate enough!" the giant grumbled "She's no' at a' like the Jezebel her mistress!"

"Did you hear my order?"

"Ay! Stan' by y'r traces, there! Tak' hold!"

Sixty tired men sprang from the ground to do his bidding instantly, and Dick rode on to where all the Russian reserve ammunition lay piled on commissariat-wagons, horsed from the stables of Russian officers.

"Forward!" he ordered, pointing to the hills; and the cavalcade began to move.

AT the far end of the other wing Usbeg Ali swallowed his own

thoughts of plunder and forced Dick's will on men whose ideal

might be Persia liberated, but whose immediate yearning, like his

own, was for the loot in Astrabad bazaars. His especial choice

would have been leave to sack the treasury, and it went hard with

him to turn his back on the thirty-foot-high wall that frowned

less than two miles away; yet it seemed to him that there was too

much of the hand of Allah in Dick's destiny for him to forget

discipline and glut his own desire.

"Bismillah!" he muttered in his beard. "The fellow strokes his stubborn chin, looks up once to heaven, and then knows what to do! I tell tales of him that I invented and the tales prove true ones! I prophesy about him, and the prophecies come true! Who am I, that I should doubt the hand of Allah! Nay—I am a soldier, and I have my orders!" He rode like a thunderbolt, once up and once again down the line, shouting for close order; and since close order presaged movement of some kind they obeyed him readily enough.

"Loot!" they began to murmur. "Lead us to the loot!"

"Persians!" he thundered at them. "Who is afraid?"

No Persian ever will admit he is afraid, until he thinks that he will gain by the admission. No one answered him. They all grinned.

"Has not every word of mine come true? Said I not that this Dee-k-Anthonee is the Great Iskander born again at Allah's bidding? Is he not? Said I not that he carries in his fist the Great Iskander's sword? Does he not? Saw any—ever—such a sword, with such a jewel in its hilt? Said I not that Cossacks would melt away before him as sheep before a wolf? And did they not? Where are the Cossacks? Run they not yonder? Saw any of you—or your fathers—ever—Cossacks running away before? Who is afraid to follow to another, greater victory?"

They looked from left to right, and from right to left again. They looked behind them, to where their dead and wounded lay in a little cluster; and they looked in front, at the Russian dead and wounded scattered about the plain—twenty or thirty to their one. Away to their right, behind them, they could see Dick Anthony lead off in the direction of the hills, and it seemed to them that they were being offered choice between obedience and whatever its opposite might prove to be.

A company commander—one of Usbeg All's seven loyal Afghans—sensed the indecision and gave tongue to his own thought on the matter.

"Zindabad Dee-k-Anthonee Shah!" he yelled.

That yell brought memories of black nights in the mountains, when they had chosen Dick by acclamation as their leader, had sworn obedience to him, and had learned from him a little of the naked honesty that was his creed. Not even the East forgets so suddenly its oath of loyalty or the memories rekindled by a rallying-cry.

"Zindabad Dee-k-Anthonee Shah!" they chorused; and from Dick's contingent in the distance came an echoing shout, yelled at the limit of enthusiastic lungs. Where Dick was, there was never any doubt about men's sentiment; it was only where his voice did not reach and he was not visible that they thought of disobedience.

"In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, I guarantee another victory!" roared Usbeg Ali, careless of promises, so that the moment was his own. "There will be another, greater battle, and plunder that surpasses yonder at the rate of ten to one! Gather up the wounded! Gather up the dead! Follow Dee-k-Anthonee! Back to the hills now, where new plans are cooking! Forward! March!"

There was still a little murmuring. From the first, these had been half-hearted men; these were they who had lagged on the long march down from the mountain-top, and had followed Dick's swift-moving force more with a view to picking up the jettison, that an army in a hurry always scatters in its wake, than because they had much stomach for campaigning in his strenuous way. It had suited Dick to confirm his judgment of Usbeg Ali Khan by trusting him to get these laggards moving; also, it had suited him to lead away his best men first, and save them from contamination; but to the left-behind it looked as if he had bade them follow because he knew he could not make them lead.

"Loot!" yelled a tattered rifleman. "Let us loot the city and then follow!"

But a kick from Usbeg All's toe rooted the man's front teeth out, and his wheeling charger sent the fellow stumbling from the ranks.

"Where are my own men? Who are my men?" thundered Usbeg Ali.

All the captains of companies, and their subordinates, were his. Either they were Afghans who had followed him through Asia, from personal regard and hope of fighting, or they were Persians whom he had promoted, and who therefore honored him. They were lustful for loot as he, or anybody, but the contagion of his soldier-spirit seized them, and they served him now almost before the challenge left his lips. They sprang into life and spurred along the line, upbraiding—shouting—swearing— promising—encouraging—praising—calling down God's judgment on all unbelievers. In five minutes more the dead and wounded had been gathered up; the line was in fours, and moving.

"Sons of unbelieving mothers!" Usbeg Ali roared at them. "Gentiles! See—ye offspring of deserting Cossacks, without any honor, and devoid of sense of shame! Yonder, in front of us march Persians—true Persians!"

He pointed to where the sun-rays lit on Andry Macdougal's machine-gun—brighter now than ever it had been before the Cossacks lost it. He pointed to where Russian wagons trailed, loaded with Russian ammunition, headed for the hills and rear-guarded by Dick's horsemen.

"Yonder march true-believers! Yonder go the men whom Dee-k-Anthonee has chosen for his own! Would ye stay behind, like little dirty jackals whimpering around the city dung-hills? Even the Cossacks have a little honor! Have ye none?"

Shame seized them. They began to march with a will, in silent earnest. They began to try to prove themselves as good or better than the men ahead, and no whit behind them in their loyalty to Dick. They began to overtake the column; and soon Dick Anthony saw fit to notice them. He sent a messenger to Usbeg Ali and, aloud, the horseman shouted a demand for more speed; but under his breath he assured the Afghan he might take his time.

"Dee-k-Anthonee says, 'Flatter them!' He needs them fit and willing for a certain service!" the man whispered.

So, gradually Usbeg Ali changed his tone, and with a soldier's tongue, that can be far more cunning than a courtier's in its own rough way, he worked hard to put them in a good conceit. By the time they reached the foothills they were no better soldiers than they had been but they had begun to think themselves each a young Napoleon, with a field-marshal's baton in his haversack.

Dick halted where the foothills rose abruptly from the level land, and the horses could no longer drag the heavy wagons fast enough to keep up with climbing infantry. There on a sloping hillside, facing another hill and out of sight of Astrabad, they held a solemn burying of dead. At one end of the long, wide trench they dug, Dick stood bareheaded, waiting while the Moslem prayers were said; and then the parting volleys rattled over Persians who had never been so honored while they lived.

"Who are we, that he should treat our dead thus?" they wondered, Persian-wise disparaging the compliment while gloating secretly.

"Ha! This is a new rule, and a better one! Since the Great Iskander there was never such a man as this! He knows what is meet, and makes it so!"

When the echo of the parting volleys had died down, even the leg-weary rear-guard were in a mood for anything; and Dick lost no time, nor any single whisp of an advantage that circumstance had blown his way. His treatment of the dead had been sincere, his every single act was always; but he knew the value of impressions on the Oriental mind and had no least compunction about turning them to use.

He ordered the wounded taken from the wagons where they lay on the cartridge-boxes. He ordered bough-litters made for them, and told off carriers. Next, out came the cartridge-boxes, and he served out two hundred rounds a man. There were thousands on thousands of rounds left over, and he had them packed on the horses. Then he ordered:

"Haul the wagons by hand along that ridge! Draw them up in line!"

They obeyed him, wondering. In full view of the distant city they arranged a barricade of wagons, overturning them and locking each to each until the whole was like a wall.

"Now, guard them for me until my return!" Dick ordered, riding down to where the rear-guard watched inquisitively. Usbeg Ali stared wide-eyed, but Dick bade him lead the advance-guard now, straight up toward the mountains.

"Lead off with the horse!" he ordered. "Throw out a screen ahead and on either flank. Wait for me unless I have caught up before you reach the fifth mile."

"But, bahadur—"

"What?"

"Listen! Burn those wagons!" urged the Afghan. "They are no use—not any use—they are a target and a hindrance—nothing more!"

"They are more use than a little!" answered Dick. "My whole plan hinges on them."

Dick shut his lips tight in a way that Usbeg AH was beginning now to recognize for the abrupt, blunt end of argument. He saluted and rode away.

"Now! 'Tention! listen!"

They had been leaning on their rifles, but the crack and resonance Dick gave his words brought them up standing like drilled men.

"Yonder in Astrabad there are not many Russians left, but those we have just worsted may rally and return. They are likely to. I am going on, a day's march from here. If you are attacked, you may send a man to warn me. Meanwhile you—Yussuf Ali—command this rear-guard. Stand here, and defend this position and these wagons until I come back. Don't trouble to conceal yourselves. Light fires tonight; let the Russians know where you are; and the best way to avoid attack will be to make the Russians think you are more numerous than you are. Fire on their patrols, should they send any; but don't dare warn me that you need help unless you are outnumbered! If I find you here on my return, good! But deserters from this post will be treated, wherever found, as traitors should be treated! You have seen your dead honored! I am ready to honor living men when they deserve it! To the wagons—forward—march!"

FIVE minutes later he left them digging trenches with whatever

tools they could improvise, and he rode away with no doubt in his

mind that they would stay there. In the first place, Yussuf Ali

was one of Usbeg Ali's trusted men, and second only to that arch-adventurer in soldier qualities. Then, too, it had been one thing

in the flush of victory to gaze and yearn at close quarters; it

was another now to lie and watch Astrabad from a distance, leg-weary and in expectation of attack. Nothing was more certain than

that they would see the rallying Cossack regiments return and

enter the city; nor were they likely to desert then—to

scatter and risk piecemeal Cossack vengeance; they knew that sort

of Hell's delight too well. They were likely to recognize, when

they were left alone to think, where, obeying whose orders, they

were safest.

"Forward!" ordered Dick, riding to the head of the remaining infantry.

"Rest here for the night!" they begged him. "We are weary men! We have fought and won a battle! Let it be the Cossacks' turn to march sore-footed!"

"Aye!" put in Andry, leaving his machine-gun to lend weight and height to the argument, "I'm a girt, strong, hefty mon ma'sel, Mr. Dicky, but I'm weary; what mus' they be?"

"Forward!" ordered Dick relentlessly, and led the way.

He went through no time-dusty foolishness of getting off his horse to walk and lead them. He was there, so it seemed to him, to lend them all he had of skill, and will, and strength; and he could do that best if he were fresh at the farther end. He was right; for had he walked, to suffer with them as some leaders would have done, those men of Persia—where neither man nor word nor motive had ever yet been rude—would have judged him an actor. As it was, they were slowly finding out that his words and actions stirred their hearts because the truth lay under them; each thing he did, and word be spoke was an expression of what he thought right, and therefore best, calling for neither excuse nor explanation. To them it would have seemed a sign of weakness to dismount and walk. To him it would have been a stupid waste of strength.

As usual, his mere presence put spirit in them, and the tired men tramped and climbed behind him with a will. Andry, looking back past his machine-gun to the ant-like column toiling up-hill, recalled a picture of Highlanders returning from a foray that had hung above his mother's mantel in the cottage on the Isle of Arran. Haunted by the memory of a little French maid's face that he had held between his great gnarled hands and kissed, his softer side was uppermost and maudlin sentiment met martial on common ground. There was a man beside him, who sweated under the leather bag, that held all Dick's wardrobe. Andry grabbed the bag, and opened it.

Out came Dick's bagpipes; Andry's cheeks bulged outwards and his temples took a purple hue as the drones began to hum their weird inharmony. Then, in a minute, the long straggling line picked up its feet and tried, in spite of rocks, to keep step to a tune to which forced marches have been made times without number.

Hie upon Hielan's

An' low upon Tay,

Bonny George Campbell

Rode out on a day.

Tired leg-muscles grew limber, and weary wills awoke as if by magic. Magic it was—the mad, soul-stirring lilt and laugh of Highland music that makes men forget themselves and tingle only for a hand in happenings. It lifted them; it drew them, till the gorges echoed to the thunder of their coming, and the birds sped scared away.

Up, up Dick led and Andry lured with tunes; and whatever goad—of instinct, intuition, information, or mere whim—was driving him, Dick said nothing and answered no questions. Not even when they came on the advance-guard, waiting for them on a plateau, and Usbeg Ali Khan rode back to report the trail all clear, would Dick give any details of his plan.

"Bahadur," said Usbeg Ali, "none can catch us. These men came down-hill by forced marches, and fought hard; why race them up-hill again?"

"I won't!" said Dick.

True to his word, Dick led the way now to the right instead of upward. Not for an instant did he slacken pace, but leaving Usbeg Ali to bring along the infantry, he hurried the advance-guard along hill-sides.

"Why hurry?" asked Usbeg AH, spurring after him, determined to get to the bottom of the reason for such haste. "The men are faint There is a limit to what men can do! What is the danger now, bahadur?"

"An army-corps at least! Two perhaps!"

"Where?"

"Over the Russo-Persian border!" answered Dick.

"Bahadur, that may be. One army-corps might be enough to ring us 'round and bring us to bay, even in such a mountain range as this; but even its cavalry could not come up with us for a week or two! An army-corps moves like a serpent on its belly, slowly and by fits and starts. It is the pace that kills, bahadur!"

Dick, spurring his horse up a narrow path between two rocks, turned his head and smiled.

"Killing and war go hand-in-hand!" he answered quietly.

"Bismillah!" swore the Afghan. "We have all too few men, and can spare none!"

"Then, we mustn't spare the Russians!" answered Dick hurrying on-

"Now, Allah give me understanding!"

Usbeg Ali swore into his black "beard and drew rein. He waited until the head of the main body had caught up with him, and one of his loyal seven drew aside to ask him questions.

"What is it, sahib? What is his plan? At this pace there will soon be none to follow!

"The music draws them on, and curiosity; but they are weary. It is all too swift and fierce! They will begin to desert in droves, and who can stop them? Then, when the hunting begins in earnest and the Cossacks ring him 'round—"

"May I be there!" laughed Usbeg Ali. "I would liefer die at his side than own all Russia! Forward! Forward!" he shouted, riding down the line to urge them. "Forward to more fighting!"

Andry's cheeks ached, and the sweat ran down his purple face in streams, but he played on manfully, stumbling over stones and stopping every now and then to lend his great shoulder to a wheel and help his tired gun-team. He played and watched, played and watched until he found the tune they seemed to like best; then he played that all the time:

O Logie of Buchan, O Logie the Laird,

They ha'e ta'en awa' Jamie that delved i' the yard,

Wha played on the pipe an' the viol so sma',

They hae ta'en awa' Jamie, the flower o' them a'!

He said, Think na lang, lassie, though I gang awa';

He said, Think na lang, lassie, though I gang awa';

For Simmer is comin', cauld Winter's awa',

An' I'll come an' see thee in spite of them a'!

The tune was not Persian, and no spark of Persian sentiment was in the words; but possibly the big man's thoughts about the maid, whose lips he longed to kiss again, lent pathos to the simple tune and rendered it acceptable to all who heard.

The Persians marched to it like men of iron, and before the sun was much more than half-way on his journey downward to the Western skyline they had come within sight of a cliff that overhung the plain.

Dick called a halt at last, when they reached the brow of it, and pointed to a fringe of trees behind which they might lie and rest.

"No camp-fires, now! No watch-fires tonight! No noise! Eat your rations cold and sleep where you lie!" he ordered.

"Bahadur, I am second-in-command; may I not know the secret?" asked Usbeg Ali. "Am I likely to betray a confidence?"

Dick smiled. He well knew the Afghan's loyalty. But he knew too who had told those utterly amazing tales about Iskander come to life again, and he judged that such poetical imagination would be better not too freely fed. An oath was an oath, and the Afghan could keep one; but silence had ever been Dick's favorite weapon; loud words and a little boasting were the seasoning of war to Usbeg Ali. The Afghan could make songs, and sing them in Persian, that would set a whole army by the ears without divulging anything. Dick wanted his army quiet—incurious—at rest.

"There's no secret, Usbeg Ali. I've got suspicions by dawn I'll know the truth. Help me pick watchmen now! Use all your wits—we need eyes, ears, and silence!"

Together they walked in and out among the men, watching them munch dry corn and make ready to sleep the night through; and now the wisdom, in at least one way of Dick's forced marching was apparent. It was plain that he considered secrecy as to his present whereabouts highly important; but the man who had said there were no traitors, even in that hard-marching host, would have been laughed at. There are always traitors in the East. Disappointed of their loot that morning, there were gentry with him who under other circumstances would have loved an opportunity to go over to the Russians with information of Dick's whereabouts that would be worth a price. But he had tired them utterly, both horse and man. Even the most discontented were glad to lie down where he bade them lie, and sleep where he let them sleep.

Not even gold would have tempted them to move before they were compelled. There was no small-talk passing between companies—no running here and there to interchange ideas. They lay and munched their corn under the nodding trees, rejoicing in the cool, while below them on the plain the heat-haze shimmered and kites circled above dust-whirls, or swooped to gorge. Soon, most of them fell asleep, to dream of peace, and plenty, and green pastures.

Then, as Gideon did once in the Bible story, Dick took steps to choose a handful from his host, on whom he could depend. He and Usbeg walked here and there, here and there, in and out among the companies, looking for men whose eyes were bright still, and who were not too tired to answer jest with jest. Traitors make poor and unready jesters as a rule.

"Where is thy shame?" demanded Usbeg Ali of a man who washed his trousers in a brook and displayed more anatomy than cities would consider legal.

"Lent to the Cossacks—they had need of it!" the fellow laughed.

"Take that one, bahadur!" advised Usbeg Ali, and Dick beckoned to him.

"Thou!" called Dick to another one who grubbed himself a shallow trench in which to lie. "What buriest thou?"

"My share of the loot!" the fellow answered

"Come!" said Dick. "I'll use you."

It took them two hours to pick a hundred and fifty men; but at last they had three fifty-man platoons to take the strain in turn; and then they pushed a living fringe far forward, beyond the low foothills to the hot plain. Dick posted them, though Usbeg Ali went with him to see, and Usbeg Ali listened to the orders that he gave; but the Afghan learned little.

"Now for the closest watch that ever army kept!" commanded Dick. "The man caught nodding, dies! The first man to get information wins promotion on the spot! I'm short of good sergeants!"

He had learned the trick of managing his Persians. A whip behind, spurs at each flank, and reward held out ahead are good for horse and man—West and East—cultured and uncultured—leader and led; but they are particularly useful south of Alexandria or east of the Levant. Dick's earlier qualms—that all good men must have when first called on to be drastic—had gone, and though he loved liberty more passionately now than ever in his life, he understood that to get general efficiency he must deal ruthlessly with individual offenders. By nature he was just—by training quick—by instinct always wide-eyed; on the watch for what was good and right, and instant to acknowledge it: they had found that out. Above all they had found him that rarest of all rare things in the East, a man of his word; so they believed in him when he threatened them, and when he promised them reward they knew it was a real prize that they might strive for with assurance.

"We will watch as the night-birds watch for mice!" they promised.

"Two hours!" said Dick. "Two hours, and then relief for four—then two hours' watch again!"

When the last fixed-post had been attended to, he and Usbeg Ali walked back through gathering gloom to the foot of the over-hanging cliff, where Dick had ordered a grass bed made for himself, raised on four cleft sticks.

"I'm going to sleep here," he said, "where they can find me quickly. I've a lucky trick of taking sleep in concentrated doses, by ten minute at a time—learned it small-boat sailing in the Kyles of Bute."

"A God-given trick, bahadur! Praise Him who gave!"

"You haven't slept, to my knowledge, for two nights."

"I am a soldier—!"

"And a must uncommon good one, Usbeg Ali!"

"Sahib, I—"

"Don't interrupt? Go up to where the men lie; sleep until dawn!"

"Sahib. I—"

"It is an order, Usbeg Ali!"

So the Afghan went, regretfully—almost resentfully—yet sore-eyed from long wakefulness; and soon his snores sang second to Andry Macdougal's rasping salutation of the sleep-god. The whole host was sleeping almost before the sun went under, and none but the shadow-lurking outposts saw four horsemen, one by one, go racing past along the plain at chance, uncertain intervals.

Dick's orders were for silence and no attempt was made to shoot the gallopers; three slipped by untouched. So the fourth nun, riding within sound of the third's hoof-thunder, gathered confidence. He rode full pelt into a trap; they tripped his horse with a pegged rope, and pounced on him to strip him, and whether he broke his neck in falling or they broke it for him they reported him to Dick as dead. When they had torn every strip of clothing from his body they discovered a letter tucked into his sock, and hurried to Dick with it, quarreling while they ran as to who of them had earned reward. Dick—leaping from his bed before they were within ten yards of him—promoted all five instantly.

Then he struck match after match, and burned his fingers in his eagerness to read the message, chuckling to himself and thanking the god Of good adventurers because he knew enough Russian to understand the fifty words scrawled on a piece of unofficial paper. No need of an interpreter! No one to share the news! Nobody, then, to warn the Russians! For the hundredth time his trick of keeping silent had served him well! For the dozenth time Usbeg Ali Khan, who would have scoffed at the suggestion, would wonder at the subsequent event! Men who would have almost surely feared to venture had he hinted at his aim, would thunder in his wake at dawn, and trust him well enough to follow later, on the staggering, amazing trail he meant to tackle next.

"Only Russia—of all the nations in the world—could have made such a dismal mess of things!" he told himself. "I suppose only Russia could afford it!" he added as an afterthought.

AT dawn, when the drifting grayish mists were rising to

proclaim the hour of prayer, he found Usbeg Ali

Khan—adventurer, idealist, and true-believer—rising

from a prayer-mat, facing Mecca.

"Look!" said Dick, pointing through a rift in the mist to the plain below.

"At what, bahadur?"

"Look!"

Something moved, slowly, like a darker bank of mist amid the rest—half a thousand feet below, and ten miles distant—noiseless apparently; and yet there was a hint of something that suggested thunder.

"Allah!" said the Afghan.

"See 'em?"

"By the blood of Allah's prophet!" said the Afghan, "Guns!"

"And we need artillery!" said Dick.

"Bahadur—!"

"I guessed it, Usbeg Ali—wasn't sure. Now, hurry! Get word around among the men to make no noise—not a sound! I'm going down to warn the outposts to make sure no traitor gets away to warn the Russians. Look! They've been traveling since midnight—they're halting for breakfast!"

"Bahadur," said Usbeg Ali, "Allah fights on the right side—always! It was Allah made me love artillery!"

"In a few hours we will have guns!" answered Dick.

NEVER, probably, since in the dawn of ages Asia first began to writhe under the hates and loves, the devilish desires and passion-bred wars of individuals, had the hot plains outside Astrabad seen fury such as rent the Princess Olga Karageorgovich while Dick's little army wound its way toward the hills.

The Cossacks—peppered into a retreat by Andry's machine-gun—routed by Dick's charge—volleyed at until they dared not turn to look at what did, or did not pursue them—raced by her beyond control or prospect of it.

"Cowards!" she screamed. "Curs!"

Spurring in among them, spitting scorn and screeching terrible, unfeminine abuse, she galloped to the low hill Dick had pointed out to her but twenty minutes gone, and toward which the men were now stampeding. Her horse was made frantic by the passion that exuded from her as lightning flickers from the storm-clouds. She was feeling still the pressure of Dick's iron arm around her waist. It seemed to burn like a red-hot band. While he had held her on his horse she loved him—god of lost women, how she loved him! When he set her on another horse, and rode away, her hot she-tiger love turned into hate at last, and her teeth chattered at the thought of how she had risked authority, liberty, life itself for him.

She did not stop to remember that Dick had never sought her help, or accepted even her acquaintance without protest. It was nothing to her, had no bearing on the case, that she had interfered with him, tricked him, ruined him, and thrust herself On him uninvited, She only hated him, and vowed that she would teach that proud Scots gentleman the difference between help from her and hindrance—between her friendship and her enmity—between her love that he had scorned and the full flood of her hate that he had brought down on himself.

She looked around her, wild but yet unblinded by her rage, and took in the situation with a swift understanding that would have done credit to a war-scarred veteran. She saw a Cossack officer, half-way up the rising ground, doing his level best to rally the fleeing men. She rode to him—bumped her horse into him. He had a knout in his hand, as many Russian officers still do have, whatever printed regulations and the censored news may say.

"Give it to me!" she demanded; and he hesitated.

So she leaned out of the saddle and snatched it from him, spat at him, called him poltroon, and then—bewitching, hate-propelled, amazing—charged into the middle of the tide of men and lashed at them left and right. Her chestnut hair was down, and her helmet off; her eyes blazed like living fires and her parted lips emitted hisses that were thoughts too savage to take shape. She might have been Medusa; and there came a man—the officer supposed to be commanding—who felt his heart turn to stone—cold, crumbling chalk—at sight of her.

"Ha!" she screamed at him. "Here comes the fellow who knew better!"

A little fat, a little gray above and behind the ears, he tramped in tight riding-boots behind his men, purple-faced and hoarse from efforts to control the uncontrollable. Her order had been not to attack Dick Anthony; he had over-ridden it. She—for her own ends as well as Russia's—had desired Dick hunted, but not caught or killed; he—blaming her for previous disaster—had decided to attack, and to keep to himself the credit for Dick's capture or his death. He had defied her secret power—had snapped his fingers at her telegrams from Petersburg that gave her all authority beyond the Atrak River; and now be grew paler as he faced his Nemesis.

"Here comes the man who planned this business!" she jeered. "Cossacks! Seize him! Make him prisoner! Arrest the gray-haired imbecile! He led you into this shambles in the teeth of orders! Seize him!"

None listened to her, though the men who ran took care to avoid her flicking whip-lash. None took any notice of the Colonel, recovering his breath and fingering the automatic pistol at his belt. He stood figuring his chances—his word against her word, his record against her secret influence, his honest purpose against her sheer wickedness.

"Arrest him!" she screamed. "I will have him court-martialed! He shall pay for this in full!"

But they were in no mood to listen to a woman; strong men had failed to check their course. She was young; she looked young, even in her fury; age had not won respect from them that day. They hurried past her, and the Colonel waited, still fingering the pistol. She rode toward him, and her knout cracked as she came. He drew the pistol just as two lieutenants stopped running, caught sight of the impending duel, and hurried to intercede. She saw them. Wild-eyed, with an oath that would have made a common soldier wince, she flogged her horse and rode at him; but as she came he turned the pistol muzzle upward, pressed it underneath his chin, and fired.

Balked of her first intent, and so wilder yet, she flogged his dead body, cutting weals across the livid face. She snatched at her horse to try and make him trample on the corpse; but, true to instinct, each time the brute came to it he jumped or swerved aside, and she wrenched his jaw savagely, swinging him back to try again, flogging like a mad she-devil. She lashed at the corpse and her horse until the two lieutenants were nearly close enough to interfere; then she rode off with a laugh after the routed Cossacks, and began the savagest lone-handed fight one woman ever entered on.

She turned them, though it took two hours. She brought them to a halt at last—rallied them—faced them about—and led them back; and how she did it, only she knew. There were men behind her when she came, whose faces streamed blood where her whip-lash had descended; there was an officer whose blood ran in his eyes. They followed her like beaten dogs, tramping in fours as if in leash, too dazed and frightened to remember anything, or to do anything but obey her dumbly and march numbly at her bidding, back to Astrabad. For the second time within a week shamed Russian soldiers were to enter through the city-gate and march under the eye of the inhabitants.

Her French maid—the little maid who had succumbed to Andry's Gargantuan charms—rode behind the men, too frightened to let her mistress see her if it could be helped, yet much too scared to ride away. She was sobbing—sobbing for her grim, tremendous Andry, who would have put a great iron arm around her and would have told her not to "fash hersel'." She would have ridden into Hell smiling behind Andry; but to ride into Astrabad again behind the Princess was another matter, and she rode in tears.

They were challenged—brought to a halt outside the gate. None but Olga Karageorgovich could have gained admission without fighting, for the barracks were all burning and the city's inhabitants were up in arms. Once in the city, none but she could have led men unmolested through the streets; for with Dick's good leave, the Persians had already looted every stick of Russian property that could be found, and the sight of fire—the very name of plunder—had aroused them. They were in no mood to knuckle under any more to Cossack tyranny.

But she said, "Open!" And they opened. She said, "Forward!" And the Cossacks trudged in unattacked!

Two-thirds of the officers were dead, and the remainder were too cowed and spent to think of disputing her usurped command. They knew that she had authority from somewhere, and of some kind; and Russians are taught early in official life not to question orders from above, whoever hands them on. They had heard of the Okhrana, that gives orders to the Czar; they suspected she was of that secret government, They guessed that her voice—her account of things, and no one else's—would be listened to in Russia, where the secret strings are pulled. It seemed better to them to march sullenly beside their men, and not call attention to themselves.

"Open!" she ordered; and the gate swung wide. Harridan, more beautiful than even their Moslem dreams of houris in Mohammed's paradise, astride like a man, but in very feminine attire, knout-armed, and the knout's lash bloody, helmetless, her hair streaming over her charger's flanks in five-foot-long chestnut streams, obeyed—by men who two hours gone were utterly beyond obedience—almost a girl in years, but one whose eyes blazed and whose soft red lips moved silently in a rage too wild for words, that most un-Persian of all women dazed the lean riflemen who held the gate, appalled them, refilled them with fear of Russia and a quick resolve to run no risks.

So she rode in at the head of little more than two half-regiments, reckless of the dead and dying on the plain outside and thoughtful only of Russia's grip that must be re-clenched on Northern Persia. Gone was her passion for Dick Anthony—gone up in a blaze of anger, and replaced by a hate for him that was inhuman in its devilish determination. Gone was the thought of serving Dick by playing the Okhrana false—gone any hope of seeing him a king.

She wanted him dead now—a dead, disfigured Dick whom she could spurn and spit on. In her imagination she could see him dead—still proud, still smiling that disdainful, resourceful smile of his; and she knotted up her fingers in an ecstasy of wickedness, gloating over the thought of how her whip would slice the smile into red unrecognition.

Not a minute did she waste. The wires were down and the Caspian cables cut; she had the field all clear, and none now would be likely to oppose her orders. She seized new buildings for the Cossacks, raided the bazaars and seized an ample store of food, arrested twenty of the leading citizens, and whipped them—set Astrabad a-thunder with the preparation for new, resolute beginnings.

At first she imagined Dick would attack the city, and she started to fortify the place. The flogged inhabitants soon brought out cartridges that Dick's quick foray had overpassed, and the provisions that she plundered were enough to feed her men until relief could come. But then, looking out toward the foothills from a high muezzin's tower, she saw Dick's line of wagons and believed that he proposed to entrench himself in that position.

"Idiot!" she laughed, gazing through binoculars. "He waits for more men! He will wait an hour or two too long!"

It was useless, yet, to try to send her Cossacks out against the wagon-barricade. They could loot the bazaar, but their fighting pluck was gone.

"Guns!" she muttered. "I must smash that wagon barricade with guns!"

But the guns had been sent to harry Dick in his former fastness up in the Elburz Mountains. First had gone half the available infantry to hunt him from the bills, and the guns had followed later to pound him and his men to fragments when they broke for open country. It had been that expedition she inveighed against, for she believed they could reach Dick and smash him; and then she had loved him.

But Dick stole a march on infantry and guns alike; he had burst on Astrabad unheralded and unexpected. She blenched, now, at the thought of how he had ridden in and had carried her out again for his own honor's sake. Contemptuously he had set her in a safe place and had ridden off, so, she cursed Mm through set teeth and cursed again because the guns were not there to pound him into bits.

They had sent for the guns when Dick first showed at dawn, and she had advised waiting for them so that Dick might not be hurried; for she loved him then.

Now, she cursed because prudence and her own orders would prevent the guns from coming until the infantry—at least a day ahead—could turn, overtake them, and be escort.

"Gallopers!" she ordered. "Four! No, six!"

She wrote a letter, and made six copies of it, ordering the guns to hurry back and not wait for their escort, explaining in fifty words that Dick Anthony was entrenched near the city, and that therefore the road below the foothills must be clear. She sent them one at a time at intervals, in case of accidents. Two got by unobserved. The following three were seen.

It was the last man whose letter reached Dick Anthony.

WREATHED in the rising mist, Dick Anthony stood silent on the cliff's projecting lip and gazed through binoculars. He seemed breathless, although behind him—like the hum of an angry hornet-host—his men buzzed excitement and amazement that would not be stilled. Some sculptor might have carved him from a pinnacle of granite, to preach resolution and inspire a conquered folk to rise.

"Silence!" demanded Usbeg Ali.

"Silence!" swore a hundred officers who ran quickly here and there, for some men would not keep cover without a rap or two on the head from a sword-hilt.

"In the bazaars at home ye begged for backsheesh—backsheesh!" growled Usbeg Ali, his black beard bristling with military ardor, and his big spurs jingling as he strode among them. "Under the Cossack whips ye begged for mercy! Oi-oi! Mercy, baba! Oi-oi-oi! Now ye want to boast before the time! Hey! What a change in such a little while! Watch him! Does he boast? Does he speak? Or is he thinking? Aye—Persians—it is good to think!"

Dick Anthony had finished thinking, almost. He was thanking Providence that had made him a soldier's son and had set him to studying war while he was in his 'teens; that had made him hunger, since he was old enough to play with a toy sword, for the laurels only fighting-men may gather; that had made him always dream of leading some day that Highland regiment whose Colonel was an Anthony times without number, all down the ringing, reeking page of history.

Those boyhood dreams had been his inspiration, to strive—to study—to attain. For all his one spare shirt and boots that were beginning to be worse for wear, the man who stared so earnestly at far-away artillery was a finished, educated soldier. Thorough in everything, he had even made himself an expert on the bagpipes because, in his opinion, there was nothing that a Colonel should not know; he had meant, when his day came to command a regiment, to be able to choose his own pipe-major without assistance or advice. Artillery was not his service, but he knew all the books could tell him about guns.

He had been omnivorous. He had studied—read—invented—listened— (principally listened)—until he knew more of the art of war than many veterans of twice his years and a thousand times his experience. Besides his twin gifts for work and listening, he had a genius that could bridge gaps, and fill up the unknown with such shrewd guesswork that a problem would be answered in his mind almost before other men had grasped its nature.

Little did the Russians dream, when they laid their plans to harry and hunt him, that they had chosen for their quarry a brave gentleman who was more than match for their generals. They treated him almost as a joke. They half feared that he might lose courage, or that the Persians would soon tire of him and then their new brigand would no longer be a plausible excuse for marching men down over the Atrak River.

Even after his first swift victory, that sent a Cossack regiment marching in weaponless shame back to Astrabad, they had not taken him seriously. The army, defying the Princess, refused to be sacrificed again, and demanded his death or capture; but nobody believed the task would be very trying, of raking him out from his mountain stronghold and bringing him to bay on the plain. They sent infantry, in no great hurry, to draw a cordon through the hills and harry him down to the open land below; and they sent guns, in still less hurry, to wait on the plain and riddle his men with shrapnel when they broke for the open, or in case they tried to stand. But they failed to see the difference between Persian outlaws lacking a real leader and the same men led by Richard Anthony of Arran. They let the guns follow along without an escort!

For a moment—a short, swift-thinking moment—with a city at his mercy and his men all yelping for the loot—Dick Anthony had used that gift of his—had placed himself mentally in the enemy's position—had deduced, and had done the opposite to what anybody would expect.

"Bahadur!" said Usbeg Ali, drawing nearer now respectfully, yet somehow with a hint of insolence. He was angry that he had not been consulted. "When we first looked on Astrabad three days ago, I too saw those guns going the other way. I knew they had gone after us, and that we had given them the slip. But—who brought word that they were coming back without an escort?"

"I saw gallopers go off to warn them the minute we showed up," said Dick.

"But—"

"Didn't our scouts tell us about infantry, more than a day's march ahead of the guns? Weren't the guns likely then to wait somewhere for the infantry to overtake them on the way back?"

"Yet, here they are without the infantry!" said Usbeg All.

"Recall that barricade of wagons?"

"Aye."

"The Princess thinks we're all behind it, and she wants guns in a hurry to splinter it up! The guns waited first, then got a second message and came on alone."

"But who could have known she would reason that way? Who could have known she would not be cautious and warn the guns not to move until the infantry had overtaken them?"

The Afghan, too, was a soldier. He was old in war; and he had not quite forgotten his resentment at Dick's secrecy. It would have suited him well to prove Dick's reasoning at fault, whatever the chance outcome of the reasoning. He was forgetting his former recognition of the Hand of Allah!

"That was no soldier's chance to take, bahadur! That was a plan like a woman's—supposing this, and supposing that—without much fact to go on, and leaving over much to chance! A soldier should select one fact and build on it!"

Dick closed his binoculars, snapped them in their sling-case, and faced Usbeg Ali at last, with a good-humored smile that made the Afghan wish he had not spoken; it was almost affectionate and it was so expressive of intelligence that mere temper—mere resentment—could not stand against it.

"Would we have been better off," asked Dick, "scattered through city streets, with the men looting and the inhabitants getting more than tired of us? Would it have been better to wait there to meet guns and infantry combined?"

"We might have met guns and infantry together here," insisted Usbeg Ali. Easterns, when they harbor the least resentment, can be obstinate as mules.

"As it is we're luckier than I hoped for and we'll take 'em one by one! I'll trouble you to get your men in hand, Usbeg Ali. Get a thousand hidden along that ridge to our right—that ridge that reaches out across the plain. You'd better hurry—the gunners won't be long about breakfast.

"Wait! Play a waiting game! When they get well within range, open on them; they'll limber up and retire to look for their supports after they've answered with a round or two. Leave 'em to me, then. Don't follow—pepper 'em at long range, but don't break cover. Send Macdougal to me!"

In a minute Andry stood overtopping Dick by at least six deferential inches.

"I was thinkin', Mr. Dicky—"

"Oh. Another man with a grievance? Can't you bury it?"

Dick was in no mood for one of Andry's lectures on morality or any other subject. He had each move for that whole morning planned ahead, and his extraordinary eyes were gleaming. He was eager to begin, yet no more in a hurry than the captain of a ship that runs on schedule time—impatient only of unnecessaries. Usbeg Ali Khan, of Asia, was entitled to the same consideration as a little child. Andry, ex-private of the Line, could be treated as a full-grown man who understood.

"Na-na! If I'd a grievance, as ye ca' it, I'd inflict it on ma team! Ye canna grieve me while ye're the man ye ar-r-e. I was thinkin'—"

"What?"

"Ye'll do better if ye dinna gang too near yon guns. Send ither folks! Send less highly impor-r-tant bodies! Stan' ye here, on this cliff-top, Mr. Dicky, an' dir-r-ect the fechtin' like a general! Ye're o'er fond, mannie, o' exposin' y'rsel' to verra onnecessary but amazin' risks! Thinkin's your affair—the fechtin's oors—I'd have ye remember that! This expedition—or whatever else it is—wad be like a man wi' his head cut off, gin anything shud happen to ye—it 'ud tur-r-n to wu'ms, an' they'd a' run different ways!"

"Is that all?" asked Dick.

"That's a'."

"Then, get your gun away! D'you see that copse between two hillocks over to the right—no, that one, at this end of the long ridge? Well—Usbeg Ali Khan will hide his infantry along that ridge, and I want you with your machine-gun in the copse at this end of it. Keep out of sight and don't open on the Russians until they're so close that you can't miss. Don't shoot their horses —I want their guns, teams and all—d'you understand!"

"Aye—I ken."

"Then, start!"

"Wull ye no' promise ye'll keep out o' range, Mr. Dicky?" Dick laughed.

"I'll tell you what I promise you, my man!" he answered, "If you talk treason I'll reduce you to the ranks and make you carry my bag! Be off! Get your gun away!"

"Good-by, Mr. Dicky!"

The giant held out his hand and Dick shook it, squeezing until Andry's eyes watered.

"What's the matter, Andry? What's all the fuss about? D'you feel afraid?"

"Aye! I'm feared! We twa ha' tackled men taegither—day an' night—we've sailed stor-r-my seas—we've fought i' the dark—an' we've aye won. But this is the verra first time we take on guns, Mr. Dicky; I'd rayther ha'e ye promise to keep oot o' range! Wull ye no' promise—jus' this fir-r-st time?"

"No," said Dick swallowing a smile. "'Shun! Right about turn! To your gun! Quick! March!"

SO, while the gunners ate their breakfast, there crept between

them and Astrabad a long line of Persians who had a crow or two

to pick with Russia—men who needed little warning, now, to

keep under cover and be silent.

Most of them had seen Russian grape-shot go whistling through the streets of taken cities; Russian "temporary occupation" of Northern Persia had been of the time-honored Tartar type, including "education" of the natives. They knew about artillery, and could respect it; so they crept unheard, unseen.

On either hand from where Dick's high, projecting cliff-edge overhung the plain there went a long, low ridge, each in the rough shape of a semicircle, one concave and the other convex. Each ridge grew lower and flatter rapidly, as it left the foot-hills, until where it reached the plain it was little more than man high. Man high, though, each extended miles on either hand toward the distant Caspian, and there was no way of reaching Astrabad without crossing both of them. They were easy enough to cross, for a fairly well-worn track led straight over them at spots where the ridges bad been broken, either by the crossing of some ancient army or by the whim of nature.

A trumpet sounded. Leisurely the gunners seized their reins and mounted. They started at an easy walk—six guns, one following the other, with an extra ammunition-wagon to each gun and a quite considerable convoy of provisions. Ahead—only a little way ahead, and more because it was the rule than for precaution's sake—there rode what should have been the battery ground-scouts; nominally that was what they were—actually they were a screen that served to lull the rest into a false sense of security.

A second trumpet sounded for the trot; and for perhaps four hundred yards the column jogged and bumped along, with heavy wagons jolting in its wake, making the dull, rumbling thunder that rides ever with artillery. Then, an officer of the advance saw something on the ridge ahead that awakened his curiosity.

Instead of sending an alarm back, and letting the guns halt until he had investigated, he galloped ahead alone; and as he spurred—timed to a nicety—Dick Anthony led his seven hundred horsemen at a walk behind the other ridge. Now, the Russians were between two hidden bodies of an enemy and absolutely unsuspicious of the fact.

The officer rode on and nothing happened. He reached the ridge at a point where low bushes crowned it. He rode over it and disappeared. Nobody heard the yell for help as he was dragged from his horse and knifed; nobody saw his body again, for the jackals finished it that night.

The rest of the battery continued to advance, sublimely ignorant of twitching fingers curled over triggers, and of a machine-gun whose mechanism purred to the testing of a canny, careful Scot, The Cossacks loosed their tunics—lit their pipes—and some of them began to sing.

It was that other sense all savage people have—that soldiers can acquire by dint of training—and that mobs sometimes betray—that wordless intuition of impending danger that brought the advance guard to a halt at last within a hundred yards of the ridge. They halted first, and then an officer called "Halt!" without exactly knowing why.

The order had but left his lips when a rifle-shot made the word his last one; and then instantly the whole long ridge became a line of spurting flame, and there was no advance-guard any longer—only a row of horses that stood patiently, and one loose horse that galloped back. Heads appeared above the ridge, and yells that made blood run cold were raised in a sudden storm of sound. It was the yells, and not rifle-firing that sent the trained horses galloping back at last, to throw the gun-teams in confusion and delay the business of "action front."

Training, good leading, courage, and the pride that rode with them because they trespassed on a foreign soil, all helped the Cossacks—those and bad shooting; for the Persians were excited and their aim was villainous. The Russians unlimbered and got into action with a speed that did them credit, and there were enough men left to man each gun and send a withering dose or two of grape shrieking on its way across the ridge.

But Andry's machine gun opened on them—pip—p-p-p-p-ip-ip-ip-p-pip—pip-pip! He was taking his time and picking off the gunners. When two guns faced 'round to attend to him there were only just enough men left to obey the instantly succeeding order to limber up and go. In a storm of bullets that seemed to slit the very universe in fragments, and that rattled off the barrels of the guns like hail on a window, the Cossacks hooked their teams up, turned, and fled—back in the direction of the mountains—back to meet the infantry who should be hurrying hot foot to catch up with them.

They rode straight toward Dick Anthony. He loosed but half his seven hundred, and rode straight at them! There would not have been room to turn had he used his whole force of mounted men; and he would have foregone the charge—would have shown himself, and waited for the Russians to surrender—but for his fear that the Cossacks might perhaps have time to break their breech mechanism. He wanted those guns entire, for a venture that no Cossack would have dared to dream of.

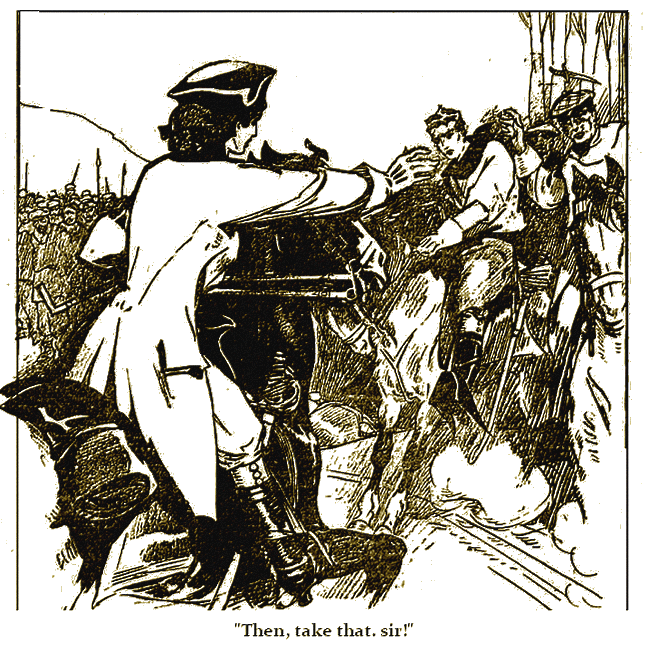

THERE was sword-work before the guns were taken, and Andry

Macdougal's fear for Dick came near to being justified. A major

of Cossacks, maddened at losing the battery that represented all

the pride he had, singled out Dick and met him halfway, blade to

blade. He knew the stories about Dick that had gone abroad in

constantly exaggerating circles; he knew it had been said that

Dick was an impostor and not the real Richard Anthony of Arran;

he remembered it all now as he rode, and in perfectly good French

he hurled it at Dick's head.

"Impostor" was the mildest word he used; but he grew silent when the chargers' heads were but six yards apart and he could see Dick's eyes—blazing, amazing eyes—that looked straight through him, over the hilt of a sword that did not move. Something of a duellist was Major Guchkov; he had met a man at dawn five times, and had survived untouched; he knew the sword well enough to prefer it to the chance of pistols, and full well enough to know a better swordsman when he met one. Now—as he watched that still, keen claymore point, that seemed to be unaffected by the charger's galloping—he recognized a better sword than his. When the points met and the sparks burst out along two glancing blades, he felt a better sword than his, and a wrist that gave him qualms of anticipation up and down the backbone. The odds were on Dick Anthony from the instant they touched points.

But a Cossack raced to his Major's aid, and Dick's good charger groaned, hamstrung and helpless. A Persian shot the Cossack dead as Dick dismounted, but the Russian major's sword missed Dick by the breadth of a breath of air.

"Ping!" came a shot from Andry's gun, in proof that a Scot's clan-loyalty is wide awake. "Ping-ping!" But the charger plunged, and the shots went wide; and then Dick was between Andry and the Russian, so the shooting ceased. Dick seemed to be half-paralyzed—as if the loss of his charger had bewildered him—for he stood with his sword-point down and seemed to wait for the inevitable end. Some of the Persians saw his plight, but none rode to his assistance; they had heard too much about his being Iskander reincarnated; this seemed tike anticlimax, and it struck them useless.

Only Andry, squinting down the barrel of his hot machine-gun, read the signs rightly and exulted. He had seen Dick fight in the old days on the Isle of Arran, when the bigger boys from other villages had come to make him prove his title to be leader or relinquish it for good. He knew Dick's trick of waiting, and in thirty seconds more he slapped the gun as if it were an understanding thing.

"I told ye so!" he murmured confidentially.

The Cossack major grew a little overconfident—a little bit too rash. Seeing Dick's drooped head and lowered sword-point, he imagined Dick was hurt. He recalled the offer of five thousand roubles for Dick Anthony alive or dead; and he considered that a dead Dick Anthony, from personal experience and all accounts, would be easier to take to Astrabad than a live one.

"Surrender!" he yelled; but he gave Dick no opportunity to yield. Instead, he rode in with a rush, to make an end; and Dick seemed to wait for him with almost resignation.

What actually happened then was too quick for anyone who witnessed it to describe correctly afterward. The major rode point-first, and there were some who swore that Dick's point rose in the nick of time and turned his upward. But most said that Dick ignored his sword completely, and it is certain Dick did not stand too long; nor, when he moved at last, did he take the officer on the side expected.

He sprang, if a man may be said to spring whose movement is too quick to see, crossed the horse in front, and seized the major's leg. He could have killed him then and there, for the horse raced on and Dick's grip was unbreakable; held as he was with a leg nearly torn out by the roots, the major could not bring his sword-arm into play. He kicked, but suddenly Dick sprang again; and this time the major shot clear out of the saddle on the off side, landing on his head and shoulder.

The next thing that the Russian knew was that Dick's foot was on him, and a claymore's two-edged point was at his throat.

"Did you mention the word 'surrender'?" Dick inquired.

"No!" swore the Russian from between set teeth.

"I'll put it differently. Will you surrender?"

"Sacré cochon! I surrender to no outlaw in the world!"

The Russian spoke in French, and Dick answered him in French with that eloquent smile of his that seemed to light up his whole face.

"Will you surrender your guns and men?" he asked.

"I surrender nothing!"

"What a rotten poor chooser you must be!" laughed Dick. "Here —you—and you!"

He called up half a dozen men and ordered one of them to snatch the major's sword away.

"Now, bind him hand and foot!"

He looked once keenly at all six of them, memorizing faces; each knew that he could pick all six again out of a thousand, should he wish to.

"I hold you six answerable for him!"

He had time to look around him then, and in a second his calm humor left him. His eyes blazed again and his lips became a straight, hard line. His Persians were butchering their Cossack prisoners! Dozens lay dead amid the gun-wheels and under the legs of horses. Fifty more were lined up, ready to be shot, and he was just in time to fling himself in front of them, and stop the volley that would have turned his battle-field to a shambles and his victory to a crime.

He cursed them. He called them cannibals. He mounted the captive major's horse and rode among them flogging them with a broken rein. He swore they deserved to have Cossacks ruling them. He swore he would never lead another Persian, or strike another blow for a country that bred only murderers and swine. He ordered them away from the guns—away from the prisoners and wounded—out of his own sight. And, when Andry left the machine-gun by the copse to walk across and talk Scots words of comfort to him, the big man found him sitting on the carcass of the hamstrung charger he had put out of its misery, his sword across his knees, his red, bare head between his hands, sobbing his heart out like a little child.

"Oh, Andry—Andry—am I chargeable with that?" he asked. "Am I an Anthony, or—"

"Laddie, ye're a gude Scots gentleman!" said the big man, kneeling by his side.

"Is it worth it, Andry? We've been touching pitch, and we're defiled! I thought I could teach them to be decent—I thought I could make 'em deserve to win! I was wrong, Andry—I'm an ass—I should have pulled out right at the beginning!"

"Laddie!"

Once before Andry had seen him that way, when he broke a leg and with it the chance of ever getting an army commission by the front-door route. It had taken hours, then, for the tremendous, patient Scot to find a way of rousing him to his true form; but, sitting and arguing beside a convalescent chair he had found it at last, and he remembered now.

"Laddie—Mr. Dicky—d'ye no remember what the Cossacks did tae oor Persian prisoners? D'ye remember that mon's back where the whup had cut in criss-cross? Wad these puir de'ils no' hanker for revenge, wi' that example i' their minds?"

"Thanks, Andry!"

Dick stood up. He stared at a little herd of Russians who had thrown their weapons down—at fifty who lay dead—and at his own men, who stood about in no pretense at order, each with a horse's bridle-rein across his arm.

"You invited me to be your leader!" he said with a voice that rang again. "I refused, but you insisted; I agreed at last. Now—by the living God, I'll lead—and I'll lead men—not animals! There shall be a lesson here—now—that will be remembered while this campaign lasts! Stand still! Stand exactly where you are! I'll shoot the man who moves! Andry! Get back and cover them with your machine-gun! Hurry!"

MIDNIGHT found the Princess Olga Karageorgovich, chin on hand, staring at the distant Persian watch-fires that danced before a row of upset wagons. She sat in the little four-square space at the top of a muezzin's tower, and it suited her well, for there were openings on all four sides, through which she could look down on the city and half the countryside without once moving.

She believed Dick Anthony behind that row of fires; for, as a panther thinks his enemy is stealthy, and the wild-eyed bull-buffalo imagines his antagonist is bold, so she believed Dick Anthony would reason much as she did. She had no prudence in her being, nor did she believe he had any. She was all cunning, bravery, and tigerish desire; and although she had loved him for the naked honesty he lived and spoke, she ignored it utterly when planning his destruction. Now that no fate could be too mean for him in her eyes, no motive could be too sneaking to attribute to him; he had committed the worst of all offences—he had spurned her love; already she half believed him capable of cowardice, and she was sure he was a liar!

Reasoning, in her wild, swift-twisting way, ignoring facts, and trusting only prejudice, she had deduced that Dick was afraid to keep the city he had won. She knew that he knew there were guns to fear and she suspected he had seen the dust of them when he first looked down on Astrabad from his hill-top. She began to be glad she had found him out so soon—to comfort herself with the reflection that a man who flinched in the hour of his success would have failed her sooner or later anyhow. She believed him now to be waiting for reinforcements, and perhaps to be arguing with a swarm of discontented men. The only alternative suggestion she could make was that he meant to watch for the returning guns and then slip back to his mountain-top where he would think that he was safe.

Safe! She vowed, as she looked up at the silver stars, that never while she lived, and poison, a bullet, or cold steel could work, should Dick Anthony be safe from her! She would hunt him, track him down, kill him with her own hand if she must; but she hoped for, and was nearly certain of an ugly end in wait for him when the guns came back. She wrote another message and sent six more gallopers careering through the night; and this time each bore a little map that showed the line of Dick's probable retreat. The infantry were told, instead of following the guns, to climb into the foothills—hunt for Dick's trail—and lie on it in ambush. She had loved him with all her wanton might that morning; tonight, Hell raged in her, and her hate of him was something to be cultivated—nursed—and shielded.

Feverish hands, she knew, were laboring at the wires that had been cut. Within an hour from midnight she expected to be in touch again with Petersburg and the secret, swift-pulsing heart of half the world's treachery. The Okhrana, then, would have to know what the outcome was of the plan to use Dick Anthony.

The thought was disquieting. She had failed a time or two before, and so on this occasion they had warned her to succeed, or else be relegated to the fate that waited on her failure. Even then she would be envied by the world that reads, but does not know. There was a marriage waiting for her, and a word from the Czar of all the Russias would be enough to make her the legal property of a man the thought of whose boorishness and gilded gluttony brought shudders from her more than a thousand miles away. She must win! Death—any kind of death—would be better a million times than life on that man's Siberian estates.

But that thought brought others, and it seemed to her she had won! From the first the plan had been to make Dick Anthony an outlaw, so that Russia—or rather the Okhrana, that is Russia's bane—might have excuse for bringing down more troops to Persia. Were two defeats within a week—two routs—the bursting open of a Russian jail, and release of a prisoner—the looting of Russian stores and ammunition not enough? What great power in the world would stand that much without striking a blow back? What more excuse was wanted for the invasion of Persia by an army corps?

She began to see, now, that her vengeance on Dick Anthony might be accomplished better while at the same time making her own position doubly strong with the Okhrana. No doubt her masters would have grown suspicious. No doubt some telegrams had gone from discontented army-men complaining of her policy, that until now had presaged nothing but disaster; no doubt there must have been somebody with brains enough to see through her former regard for Dick. And it was known in Russia that she loved him, for once she had been unwise enough to demand him for herself as the price of her services!

It was good, she told herself, that the wires were down, and that the first message to flash along them when they were repaired could be one from her, claiming to herself full credit for the situation! She would wire them to start their army on the march southward! She would claim that she had deliberately sacrificed a regiment or two, in order to have ground enough for action! And, to allay suspicion, she would let them know now that she hated Dick—she would demand, instead of his life, his torture in her presence should he happen to be caught alive. In the secret code, whose key was memorized by not more than a dozen people, she began composing messages that would be short enough but would carry sufficient emphasis; and presently she descended the brick steps of the tower, humming to herself.

Through the dark, stifling streets she ran swiftly, though entirely unafraid, to a palace that had been assigned to her for quarters, before she and the military came to loggerheads. There, in a strong-box that was screwed to a heavy table, there were papers that contained the whole Russian depositions as well as a chart of Persia's weaknesses. Marked in red, on a one-inch-scale map, were the stations where large sections of an army-corps were camped in readiness; above the curved course of the Atrak River there were dotted red lines that represented routes, and there were figures that showed the number of men in each place. Letters of the alphabet denoted infantry, artillery, or guns. Other figures, close to the dotted lines, told how many days the troops in each station might require to reach the Atrak River. The particulars were not such as are printed on the standard maps; they represented Russia's way of keeping faith—the facts—the full of her intention to observe a promise and Persia's integrity.

She opened the box now and chuckled as she drew her finger over the map, sweeping every other minute at the moths that fluttered against the lamp or fell singed on her secret papers. Suddenly she slipped the map back into Its envelope (that was exactly like a dozen other envelopes) and called for her maid. "Marie!"

Red-eyed, the maid appeared from behind a curtain, walking as if in her sleep and frightened by bad dreams. She yawned, and the Princess scowled at her.

"Have you never finished sleeping? Bah! Isn't sleep like death? One lies in a frame—coffin or bed, no matter which— and thinks nothing—does nothing—useless —stupid. Are you stupid tonight, Marie?"

"Non, non, madame!"

The maid seemed terrified. She shrunk away, until she seemed afraid to shrink farther.

"Because I can help you to wake up, if necessary!"

"Non, non, madame! I am awake! I am not stupid! What is it that I am to do? I am wide awake!"

"Sit there!"

The Princess pointed to a chair at one end of her desk, and the maid sat on it, leaning both elbows in front of her. For a moment the Princess stared in a brown study at the white wall opposite, and any one who watched the maid at all closely might have seen that her eyes were never still; they searched the table inch by inch, missing nothing—even counting the envelopes that lay by the opened strong-box.

"Write!"

The maid seized a pen and looked for paper. The Princess lifted the big envelopes, drew about a quire of paper out from underneath them and tossed it on the pile impatiently. The maid picked up the paper, and with it the top envelope.

Of old, she had even been used as secretary when matters of great secrecy and import were in hand; for she was not supposed to understand them, and as a very general rule she did not. But an atmosphere of secrecy breeds curiosity, and the Princess would have been surprised to know how many documents the maid had read and memorized; it had become almost a habit with her to secrete papers—study them—and put them back; and now that she loved Andry, habit seemed duty to her. She stole anything, on the merest chance that it might prove to have some bearing on his fate.