RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Adventure, 1 November 1928,

with first four chapters of "The Gunga Sahib"

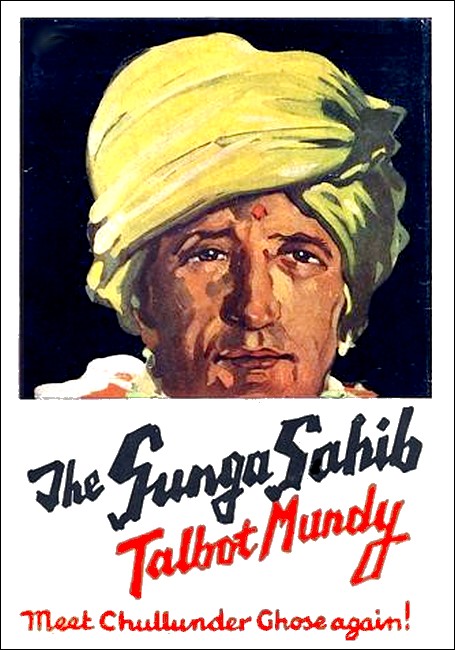

"The Gunga Sahib," D. Appleton Co., New York, 1934

"JUSTICE, destiny and love, these three are blind," says one of the lesser known commentators on the laws of Manu. But what the devil that had to do with Ben Quorn was a question that did not even occur to him. It did not even bore him. He ignored it. His job of digging graves in Philadelphia left him lots of time for reading. Nowadays, at five or ten cents a volume, a grave-digger can accumulate as good a library as anybody needs. Quorn was an omnivorous reader, on all sorts of subjects; and well-read books that can be carried in the pocket make their readers skeptical of writers—of philosophers for instance, and especially of journalists who quote philosophy. Just now, having finished a grave for a notorious millionaire whom he pitied for having to leave all that money behind him, Quorn was on a barrel in the tool-shed, studying the Morticians' Monitor—an aggressively cheerful publication that flaunts a fighting motto on the title page: "They're dying one a minute. Are you getting your share of the funerals?"

"One funeral's enough for any man!" said Quorn to himself. He had seen too many of them. He was restless.

That reference to the Laws of Manu was on the second page, which is always reserved for intellectual trifles and embalmed jokes of the "smile that leaves no sting" persuasion. Quorn turned to the Want Ads—one and a half columns on the inside back page. The top half-column on the left-hand side contained in heavy black type the advertisement: "Your face is your fortune. Improve it with Calverley's Soap." Beneath that was an electrotype of a movie hero with a he-man chin, whose face could have been improved by almost anything. Quorn thought about his own face for the ten thousandth time; it had become a habit. His face puzzled him, as it did other people. He stroked it, to remember what it looked like.

It was an ordinary sort of face at first glance. But people who looked twice, usually looked a third time. It made him look much older than he actually was. It was the only reason why he dug graves for a living instead of being some one's butler, or perhaps a bishop. Nobody trusted him much, and that was a strange thing, because he had discovered he could trust himself. His eyes held all the amber unbelief in ethics of a he-goat's; their imponderable purpose made most people suspect him of being a satyr or an anarchist. As a matter of fact he was a rather conservative fellow, who saved his money and preferred Shakespeare to Mencken, although he harbored a suspicion that poetry and music are a bit immodest.

So far Quorn is comprehensible, and he could even understand himself. Having read three and a half dollars' worth of five-cent books on psychology, behaviorism and kindred subjects, he felt he knew as much as the experts—maybe more. But why did he like elephants? There was nothing in Freud or Jung or Adler about elephants. And why did elephants like him? There was nothing in natural history to explain that. He could not stay away from the elephants when a circus came to town; they fascinated him. It seemed he fascinated them, too, although he never fed them, merely watched them. He had sometimes bribed elephant keepers to let him sit up all night with their charges. He liked their smell. He liked everything about them. But when questioned about it he usually only scratched the birth-mark on his forehead, just over the pineal gland. The question puzzled Quorn more than any one else. He seemed intuitively to know all about elephants; and because their home was India he had read a lot of books about the country and had a curious longing to go there. Last night he had dreamed he was in India. Coincidence? Here, at the foot of the right-hand column of the inside back page of the paper he was reading, was a Want Ad that made him almost bristle with curiosity. Work was over for the day. He shoved the folded paper in his pocket, washed himself and set forth to find the advertiser, at a good respectable address in an old-fashioned part of the city. He was shown into a private library and not kept waiting.

"Are you a reliable single man?" a ministerial, middle-aged person asked him; he resembled nothing so much as a heron in spectacles. Quorn gave references, answered questions and agreed to be examined by a doctor. He got along astonishingly well with his inquisitor, who was almost the first person who had ever stared at him without becoming suspicious. He was almost suspiciously unsuspicious.

"How many fellers have had this job?" Quorn asked him. "Is it one of these short-lived propositions?"

"Two men have had it. One died. The other complained of being lonely," his informant answered. "I myself was in Narada once, for three days. It is a very romantic, mysterious, beautiful place, and I enjoyed it immensely. But the circumstances are peculiar. There is usually a British official Resident, sometimes with his family; but no other Occidental is allowed in Narada for more than three days at a time, excepting our one caretaker. If you are seriously interested, I will tell you all about it."

It appeared that Narada, a tiny but extremely ancient Indian State, is almost independent, being subject only to the terms of a treaty with the British-Indian Government that dates from Clive's time. The State contains one large city that is principally palaces and temples. Nobody knows why, and nobody cares, but when its ruler pays his biennial official visit to the British Viceroy, he rides all the way to Delhi—a journey of three weeks—on the back of an elephant, whose howdah is heavy with gold and silver. He returns to Narada on a different elephant, and is afterwards very expensively disinfected by Hindu priests, although he is not a Hindu by religion, but an Animist as far as anybody can discover. The Hindu priests can make him do incredibly severe and costly penances whenever he breaks the least of their ceremonial laws. His tyranny is consequently tempered by discretion.

There is an army, limited by the treaty to one hundred and twenty officers, whose only serious duty is to guard the palace. It is commanded by the equivalent of a colonel, and looks fierce because the men all dye their whiskers and eat lots of pepper. The palace contains what guide-books would undoubtedly describe as priceless treasures; but the guide-books don't mention Narada, because of that ancient treaty, which permits no visitors, no explorers, no investigation of antiquities, and no Christian missionaries.

The latter clause of the treaty was long evaded, however, by a missionary sect, whose persuasion is so peaceful and numbers so insignificant, that even Narada's sensitive nerves were hardly conscious of the quiet intrusion. The sect was heavily endowed at some old lady's death, and for fifty years or so the mission flourished. The Reverend John Brown, adopting something of Narada's method, which includes subtlety and breaking laws while seeming to obey them, bought an ancient palace from a dissolute heir to the throne and converted that to begin with. Behind its greenish limestone garden walls he modernized the buildings. He imported plumbing, books, and school desks. He started an elementary school of medicine, that would have caused an immediate riot if he had not possessed more than normal tact; but he called it a revival of ancient Hindu magic. He even offered to supply the local priests with free drugs in any quantity; so that numbers of babies began to be born with unafflicted eyes, which led to tolerance.

There was even gratitude. A junior priest of an obscure temple, after being suitably protected by incantation, was actually sent to hang a garland around the Reverend John Brown's neck. That created a scandal, of course, but the Hindu hierarchy lived it down. The Reverend John Brown converted all Narada finally to the use of quinine. Then he died. He was promptly cremated, Hindu style, to lay his ghost before anyone could interfere, and his ashes were sent home to Philadelphia.

Death has a way of inspiring much diplomacy. It occurred to several people that there might be trouble about that cremation, because one of the principal heathen practices against which the Reverend John Brown preached was the burning of dead men's bodies. It was a very important detail of his doctrine. Quorn's informant even interrupted the flow of his narrative to emphasize that:

"It is because you so evidently believe in burying the dead, Mr. Quorn, that I shall support your application before the board of trustees. You are the only gravedigger who has applied for the post. How can the dead ever rise again if thoughtless people burn their bodies?"

Realizing the importance of the injury done to the late John Brown, the priests of Narada decided to set a diplomatic backfire before trouble should ensue. So they sent a deputation to Delhi, with a band of music, and painted elephants, to demand that the illegal Christian mission should be withdrawn. Meanwhile, half of the Maharajah's army guarded the empty mission, or pretended to, while the mails went to and fro across several oceans and the files of the British Embassy in Washington grew fat with memoranda, minutes, references and such similar documents with which delay is diplomatically fortified until dilemma dies a natural death.

"The truth is, Mr. Quorn, that we have not been very diplomatic. Mahatma Gandhi, of whom you have perhaps heard, has made things very difficult for us. We made the serious mistake, some years ago, of asking him to espouse our cause. He did so, with the best of intentions. But the result was that the Indian Government opposed us more firmly than ever. And there was a man named Bamjee, a telegraphist, who mixed himself up in everything. He read our telegrams, and he was a shrewd little bat of a man. He was the nigger in the wood-pile, if you will excuse my language. It was he who suggested a compromise, to which we were finally forced to agree after he had helped himself to almost everything removable. He did exceedingly well for himself; he became the Maharajah's purchasing agent, an office that he himself invented and applied for. The compromise provided that there should be no more mission work, but that the buildings and what remains of their contents should be allowed to continue as the Reverend John Brown left them, until we can find a purchaser for the property. We are permitted to maintain one caretaker on the spot, who must be a citizen of the United States, unmarried and of good personal character. The caretaker has no duty, and no privileges other than to see that the mission property is undisturbed until we sell it. However, we are under no compulsion to find a purchaser. Our caretaker is particularly not to interfere with native women."

"Sounds like a cinch of a job," said Quorn, whose eyes, he knew, made many women shudder. He had read all about women in five-cent books, in order to discover how to get along without them. "Women don't mean much in my life," he admitted.

His informant nodded. That was Quorn's only unpleasant moment during the entire interview. He would have preferred that this stranger should not understand so readily why women were not a serious problem, as concerned himself.

"There is only one other important point," his informant continued. "This Bamjee person, of whom I spoke, died recently. Unfortunately, his successor as purchasing agent for the Maharajah is an unspeakable Machiavellian monster named Chullunder Ghose, who appears to have fallen heir to all of Bamjee's secrets. He is an intriguer of the most objectionable type. It would be unwise to offend him—equally unwise to become at all intimate with him. Do you think you possess tact enough to govern yourself in such a situation?"

"Men who look like me have tact ground into 'em," Quorn answered simply.

Two days later Quorn was summoned before a board of trustees, questioned narrowly about his morals, certified as sane and physically fit by a physician, sworn before a notary public, given a two-page contract along with an order for suitable clothing, a phrase-book and a dictionary, and supplied with a ticket to India, second-class.

"You are off to a land," said the chairman, "where people believe in the Wheel of Destiny."

"Destiny?" said Quorn, scratching the birth-mark on his forehead. "I've read books about it. Seems to me it's ju st another word for horse-feathers."

BEN QUORN traveled seventy miles from rail-head in a two-horse tonga and installed himself in the comfortable gate-house of the Narada mission, along with a one-eyed Eurasian servant named Moses who did the cooking and helped him to learn the language. Each in his own way they were men of strong opinions, Quorn especially. There being little to do, they would sit for hours on tilted chairs, blue-shirted against the whitewashed gate-house wall and argue about Noah's Deluge, or the curious statement in the Book of Genesis that light was created before the sun. Quorn considered all his neighbors, from the unapproachable Maharajah down to the untouchables who swept the street, as heathen. That was the only word he had for them, but it was no worse than the word they had for him, so there was no spite wasted. He became a well-known figure, cleanly dressed and shaven, wandering without much curiosity through sun-baked, crowded streets. Before long, people took no more notice of him than they did of the sacred neem trees; or of the sacred monkeys catching fleas on one another; or of the sacred bulls, thrusting their way through alleys packed with humans to steal grain from the bags in the open shop-fronts; or of the sacred peacocks strutting and screaming on walls that guarded sacred mystery from public gaze.

So many things in Narada are sacred that it is simplest to take the Apostle Paul's advice and hold that there is nothing common or unclean, not even the temple dirt.

When men had nearly ceased to notice Quorn, they grew almost friendly. They ceased to become darkly silent when he drew near. Moses was not a bad language teacher, so that after a while Quorn was able to chat with strangers in the street. It puzzled him that they should be so courteous to him. He spoke to Moses about it, but Moses only stared into his eyes and smiled. It was several weeks before it gradually dawned on Quorn that what had been a handicap at home was here an asset. It appeared that men understood, or thought they did, that strangeness in his eyes, which he himself did not understand.

But the East guards understanding carefully and hides it with all sorts of subterfuge. When Quorn strolled in the great roofed market-place, at least a thousand pairs of eyes would glance furtively toward the wall at the far end, but no one spoke to him about it. Even when he and Moses once went marketing together he missed the explanation. Half Oriental, half inclined in consequence to keep all secrets hidden, but equally half inclined to lay them bare, Moses led him to that end wall, where broken sunlight played on partly ruined carving. The wall was almost unguessably ancient, and there was not enough left of the carving to tell a connected story, even to an antiquarian; but there was an obvious elephant, the lower half of a woman who had jewels on her feet and ankles, and the head and shoulders of a man in a turban. Farther along the wall appeared the same man riding on the elephant, with the lady up behind him in a funny little howdah; but most of the rest of the carving was too fragmentary to present a picture.

"Some say you look like that man," Moses volunteered. Then he looked away, pretending to be interested in a woman.

Quorn stared, unaware that he was being watched through the corners of hundreds of eyes. The market had almost ceased its chaffering.

"Some heathen god?" he asked at last.

"No, not a god," said Moses. "Onlee some old sacred personage of veree ancient time."

Then the Western half of Moses—the part that could not keep secrets—stole a moment's freedom from the Oriental half that could.

"Once," he said, "there was a man named Gunga, toward whom the gods were veree friendly. He is said to have been veree brave and pious, although not absolutelee obedient. Because of his braveree the gods selected him to rescue a princess who was living her life in durance vile. So he came for her on an eleephant, which eleephant was also chosen for the purpose by the gods. But because this personage named Gunga was veree brave and veree willing, and yet onlee partlee obedient, he did not fineesh what he had to do. He got down from the eleephant to see about something or other; so the eleephant is supposed to have believed the Gunga personage had grown faint hearted. Therefore the eleephant slew him, or so it is said, because an eleephant is not an animal conspicuous for temperate emotions. Consequentlee the princess was recaptured by her proud and veree angree father; and she lived all the rest of her life in the durance vile from which had been hoping to escape. For this the gods were sorree, so the storee is. Therefore the gods said someday Gunga must return to fineesh what he had begun. Then that carving was made on this wall. Some say the gods commanded that also. That is the legend. And now these people say you look like Gunga."

"Bunk," Quorn answered. "Heathen priests 'ud lie about nothin' at all, and pious idolaters 'ud believe 'em. Horse-feathers!" He turned away with his hands in his pockets.

"Oh yes, certainlee," said Moses, and withdrew, tortoise- fashion, into the Oriental half of him that was ashamed and afraid of the half that told secrets.

Quorn sent Moses home to prepare dinner and to chase pariah dogs and sacred monkeys out of the mission compound. He had pretended not to be interested, but as a matter of actual fact he was puzzled by that ancient carving. He recognized it did look like himself. As usual when puzzled, he grew discontented. When discontented he always went to see the Maharajah's elephants. There was something about the big brutes that made him feel less homesick. So it was discontent, not destiny that introduced him to the Maharajah's purchasing agent.

Babu Chullunder Ghose was an enormous person, probably nearly fifty years old; but he looked younger because of a genial disposition and a pair of remarkable brown eyes. He possessed a prodigious stomach, wore a very brightly colored turban and the graceful Bengali costume which displayed one huge thigh. He had a small, black cotton sunshade and a silver-mounted cane with which he terrified the chief mahout; he was accusing that miserable grafter of having stolen and resold a quantity of the elephants' rations. The moment Quorn entered the compound the babu spotted him. He squandered a cascade of brilliant insults on the head of the chief mahout, struck him with the silver-mounted cane and almost ran to greet Quorn. He was as suddenly bland as he had been angry.

"Cheerio, top o' the morning to you, how d'ye do and look who's here, by Jiminy! Mister Quorn, I take it? Caretaker at the mission. Soft job. Lots of time for meditation. Meditation leads us into mischief. Mischief is the devil, and the devil is still at the old stand. I am His Highness' purchasing agent—soft job also—first soft job in five··and- twenty years, I wish to tell you—first time in the history of this inelegantly scandalous babu that people praise me to my fat face. Let us sit down. Let me tell you what you wish to know. I know it all. Compendium of cyclopaedic, up-to-date and useless information—this babu, yours truly."

He took Quorn by the arm. He led him to a shed, where there were canvas chairs beneath a lean-to roof. He snapped his fingers and commanded liquor. In almost a moment there were whisky pegs in two long glasses, brought by a servant who knew how to excite thirst by making the ice tinkle musically.

"Self am hedonist, like Mencken, save and except I know too much to write for magazines. I drink to your distrust of me. I like it," said the babu.

Facing the shed in a wide ellipse within a high stone wall the elephants stood picketed beneath enormous trees. They tossed up the dust with their trunks and created a haze like a golden veil. They swayed to elephantine music utterly inaudible to man; perhaps it was the music of the spheres.

Quorn drank, then spoke as he reached for his pipe and filled it, knowing that tobacco made him tactful:

"I've been warned o' you. As one man to another, I've been cautioned you're a hot snipe. It was told me straight, in Philadelphia, that trustin' rattlesnakes is common sense compared to lettin' you get chummy."

"Quite true," said the babu, sighing. But his eyes laughed. "Never having had a decent reputation, self am public benefactor. There was not enough humility or virtue for us all. A half-share would be mortifying. So I contributed my portion to the public. Having got along without it I am like a charter member of a colony of German nudists. Such uncomfortable clothing as morality would annoy me. How do you like our Maharajah?"

"Never saw him," said Quorn.

"Live in hope. He is an eyeful as they say in U.S.A. United States," the babu answered. "He is out riding. Three of his wives have been consulting an astrologer, who told them that the moon is in a quarter likely to afflict and weaken his Highness' obstinacy. So they chose last night to air their views about a contemplated new—to put it diplomatically—wife, of whom they have heard rumors—very well authenticated rumors. They consider he already has enough wives and a lot too many more expensive women. They proceeded to convince him of the same profound truth. In plain words, they were women in his hour of ease. So he got drunk to relieve his headache. After being drunk he always has a much worse headache, because he mixes his drinks. So he rides abroad looking for some one to punish. He is a prince with a high sense of duty on such occasions."

"Three wives, has he?" Quorn asked.

"Five wives. Two have taken to religion. But that is not all of it. He has a daughter whose mother is dead. She has modernistic views. She acquired them from reading modern books, including Kant, Mencken, Ingersoll, Ring Lardner and Eleanor Glynn. She has refused to marry anybody not of her own choosing. But how shall she choose, since he keeps her behind the purdah? How shall she meet men? Do you see the dilemma? She is a cause of much perplexity not only to herself, but to her father also, she being his only child and the heir to his throne. He hates her, but what can he do about it?"

"Ship her to the U.S.A. and keep her short o' pocket-money," Quorn suggested.

"He does part of that. He keeps her short of money," said the babu. "Just now there is very great perplexity. Visiting Narada are some emissaries from his Highness the Maharajah of Bohutnugger, who is an eighteen-gun man of enormous influence; his royal ancestral tree is traceable for seven thousand years, where it becomes lost in Darwinian haze. Through these semi- official intermediaries he has condescended to suggest that if there were sufficient added money, he might perhaps be willing to lay his polygamous heart in the dust at the feet of the Princess Sankyamuni."

"She's our nabob's daughter?" Quorn asked.

"Yes. And that would manifestly be a fine alliance. But the infernal nuisance is that these semi-official representatives are too inquisitive. As usual with elderly gents who have looked for virtue in the arms of Venus, the Maharajah of Bohutnugger is a stickler for the social graces in his own domestic circle. Do I bore you?"

"No," said Quorn. "I don't believe you, that's all. I'm jus' curious to find out why you're kidding me."

"Enviable ingrate! I continue. Should these emissaries of his Highness learn that Princess Sankyamuni smokes, has modern views, can only be restrained with difficulty from escaping from the palace precincts and from showing her beautiful face to strangers, what then? All negotiations would be called off. Worse, though—much worse: stung by disillusionment, those emissaries of the Maharajah of Bohutnugger would immediately spread malicious scandal. It would cause the Maharajah of Narada's face to blush the color of his turban, which is usually yellow. He would rather have the girl killed, although one must admit that he is normally too lazy to murder anyone, even his own daughter, except on the deadliest provocation."

"Why tell me all this?" Quorn asked him.

"To disturb you," said the babu. "If I like a man at first sight, I invariably tell him secrets, to discover his reaction to them. That is thoroughly immoral, but it often saves me from making mistakes later on."

"Ain't going to be no later on," Quorn answered. "Me and you are destined to be strangers. I'll be civil to you, that's all."

"Ah!" Chullunder Ghose shone with amusement. His intelligent eyes became liquid with silent laughter. "Having been the destinee of too much trouble, as for me I don't believe in destinee at all. To hell with it."

"Same here," Quorn agreed. Then he finished his drink by way of emphasis. The babu emerged from his chair, with astonishing lack of effort in such a big-bellied man, and beckoned to a sais to bring his pony. He mounted the animal, Quorn marveling that even such a stocky little mount as that could carry such a huge weight.

"Neither of us then believes in destiny? Both are skeptics? Good," said the babu, smiling as he gathered up his reins and opened his sunshade. "Destiny, however, may not be a skeptic. How if destiny believes in us? Have you considered it? Auf wiedersehen—come and have a drink with me at any time."

He rode off, riding admirably. Seen from behind he resembled the pot-bellied Chinese god of Luck, all confidence, good temper and amused indifference to human morals.

Quorn stuck his hands in his pockets. "That guy's up to no good," he remarked to himself. Then he strolled across the compound to observe the elephants.

BEFORE he had been three weeks in Narada, Quorn had struck up quite an acquaintance with the biggest elephant of all, Asoka, who was chained by one leg to the picket farthest from the compound gate. He was a monster possessed of immeasurable dignity and was reputed, too, to have a temper like a typhoon, although Quorn had seen no evidence of that. He and the great animal were satisfied to stare in silence at each other, neither betraying a trace of emotion. Asoka swayed and fidgeted, as all elephants do. Quorn stood still. A mahout watched, squatting beneath a neem tree with his naked brats around him, all dependent for their living on the elephant and all ungrateful, but aware of obligations.

Quorn's back being toward the compound gate, he did not see the Maharajah enter—did not even hear him ride in followed by a group of mounted squires. The Maharajah was a handsome man, magnificently horsed. He looked too lazy to be dangerous; but his squires kept well out of range of his riding whip. He wore a blood-red turban, possibly suggestive of his inner feelings; and he spent ten or fifteen minutes at the congenial task of cursing the ancestors, immediate and distant relatives, the female family and person of the head mahout, to whom, after threatening to have him thrashed to death, he gave reluctant leave to live because a substitute might be an even more disgusting scoundrel.

Meanwhile, destiny being a dead superstition, some other influence touched the trigger of the unseen mechanism that propels events. Perhaps it was the fact that Quorn found time a little heavy on his hands. For the first time in his entire experience of elephants he had the curiosity to find out whether or not Asoka would obey his orders. He commanded the brute to lie down. To his agreeable surprise, Asoka slowly descended to earth, like a big balloon with the gas let out, and thrust out a forefoot for Quorn to sit on. Quorn did not understand that gesture, but he sensed some sort of invitation and drew nearer. Then, smiling at his own foolishness, wondering what Philadelphia would think of it, he vaulted on to the great brute's neck, thrusting his knees under the ears, as he had seen mahouts do. He felt younger and ridiculous, but rather pleased. He thought he could imagine worse things than to have to ride elephants all day long.

It was at that moment, just as Quorn was mounting, that the mahout's brats, underneath the neem tree, caught sight of the Maharajah riding forward down the track between the avenue of big trees in the middle of the compound. They yelled with one voice to Asoka to get up and salute the Heavenborn. Quorn held on, exclaiming—

"Hold her, now there, steady!"

But Asoka knew no English. He rose like a leisurely earthquake. Quorn tried to think of ways to get down, but his nerves were suddenly, and utterly for the moment, paralyzed. Asoka raised a forefoot, threw his trunk in air, and screamed the horrible salute that Hannibal, a thousand viceroys and kings, some wise men and a host of fools have been accepting as their due since elephants were first made captive. It sounded like Paleolithic anguish.

The Maharajah was riding a new, young horse that had not yet been broken to the voice of elephants. The horse reared, terrified. The Rajah spurred him. Four-and-thirty elephants at pickets scattered up and down the compound, taking their signal from Asoka, trumpeted a goose-flesh raising chorus, each of them raising a forefoot and stamping the dusty earth until a cloud went up through which the sun shone like a great god, angry.

Terror, aggravated by whip and spurs and by the cries of the mahouts, became a thousand devils in the Maharajah's horse's brain. Strength, frenzy, speed and will were his to get to hell from that inferno. He shed the Maharajah—spastically, as a cataclysm sheds restraint. He fled, as life goes fleeing from the fangs of death—a streak of sun-lit bay with silver stirrups hammering his flanks, and a broken rein to add, if it were possible to add to anything so absolute and all-inclusive as that passion to be elsewhere.

Asoka trumpeted again, accepting all that tumult as applause. The Maharajah sprawled in smelly dirt, too angry to be stunned, too mortified to curse his squires. But panic warned those gentry that their master's royal anger would be vented on themselves; and they were conscious of too many undetected crimes against him to feel able to defy injustice. They must act, to direct injustice elsewhere. So some fool struck Asoka as the source of the catastrophe, struck him across his friendly, sensitive, outreaching trunk with a stinging whalebone riding whip.

Then genuine disaster broke loose naturally—upward of four tons of it, with Quorn on top. A green and golden panorama veiled in smelly haze, with sacred monkeys scampering like bad thoughts back to where bad thoughts come from, wherever that is; and a crowd of frantic horses, shouting mahouts and screaming children darting to and fro, was opened, split asunder and left gasping at Asoka's great gray rump. It had an absurd tail, like an elongated question mark suggesting that all speculation was useless as to what would happen next.

The unbelievable had happened. Never before, in more than forty years, had Asoka broken faith by snapping that futile ankle-ring. He had always played fair. He had pretended the rusty iron was stronger than the lure of mischief, thus permitting an ungrateful, dissolute mahout to spend the price of a new steel ring on arrack, which is worse than white mule whisky, and more prolific of misjudgment.

And now Quorn and Asoka were one unit, provided Quorn could keep his balance, and his knees under those upraised ears. He had never before ridden on an elephant. The only earthquake motion he had ever felt was on the steamer on the way to India, and there had been something then to cling to, as well as fellow passengers to lend him confidence. He was alone now—as alone as an unwilling thunderbolt, aware of Force that was expelling him from something that he understood, into an unknown but immediate future where explosion lay in wait.

"Whoa, blood! Steady!"

Asoka screamed contempt of consequences. Quorn's helmet fell over his eyes; he did not dare to lift a hand to push it back in place. He was drenched in sweat. He felt the low branches of trees brush past him and was aware of danger, colored green, that went by far too swiftly to be recognized. The speed was beyond measurement; it was relative to Quorn's imagination and to nothing else except Asoka's wrath. They four were one—two animals, two states of consciousness, with one goal, swiftly to be reached but unpredictable.

They passed through the compound gate like gray disaster being born. Several sarcastic godlets on the ancient gateposts grinned good riddance. And because the road led straight toward the market, headlong forward went Asoka, caring nothing whither so he got there, and then somewhere else. Carts went crashing right and left. A swath of booths and tents were laid low. Fruit stalls, egg stalls, sticky colored drink stalls, peep-shows, fortunetellers' tents and vegetable curry stalls lined the long road amid piles of baskets. An indignant elephant goes through and not around things. All that trash went down as if a typhoon struck it, each concussion a fresh insult to Asoka. He was red- eyed. He was a rebel against the human race.

Quorn ceased to wonder what would happen. Fear had gone its limit. He recovered that state of consciousness that makes some men superior to elephants. Not that he felt superior—not yet by any means; he felt like nothing on the edge of chaos. But he had begun to speculate in terms of why, instead of what.

"Why me?" he wondered. "Easy, feller, easy! Where d'you kid yourself you're going, fathead? Let me down and then smash all you want to! Who-o-a, Irish!"

There were dozens of collisions, there was a mile of ruin in his wake, before it occurred to Quorn that he was speaking the wrong language. By that time there was a black umbrella threaded on Asoka's trunk like a rat-preventer on a ship's cable. He was catastrophically anxious to be rid of the incomprehensible thing, and Quorn had to cling to his perch like a monkey. That umbrella changed mere passion into a deliberate determination to destroy, and Quorn could sense that. He did his utmost to guide the elephant away from the market-place. He might as well have tried to turn the sun from its course.

Quorn's helmet was struck by a roof-beam as they charged in through the cluttered entrance; it collapsed, shapeless, looking like a twisted turban—like the turban on the man named Gunga on the carving on the end wall. For perhaps five seconds, malignantly choosing his mark, Asoka paused in the market entrance. Panic struck the crowd dumb, and for a moment motionless. The drama took Quorn by the spine and stiffened him. He sat majestically, unapproachably aloof as if there on purpose, obeyed by the monster he rode. Then he raised his hand. He shouted to them. But he could not remember afterwards what words he used.

Asoka screamed and burst into the throng. And there is no wrath like an elephant's. It is a prehistoric passion. It is elemental, learned in the dawn of time when Nature brewed the future in a cauldron of floods and earthquakes, burning trash like white-hot lava and obliterating errors with sulphurous deluge. Asoka's taught, trick loaded memory was in abeyance. Herd memory, subconscious, filled him with a horror of all newness. There is almost nothing that is not new to that primeval instinct—new, abominable, loathsome, to be trodden and unmade.

Down went the market stalls—cloth, eggs, brassware, chickens, crockery, imported clocks, curry and spices, cooked food, benches, baggage, basketry—smashed into a smear of vanity that once was. Humans in white-eyed droves fled this and that way, witless, aimless, shrilling, praying to a thousand gods—as if the gods cared! There was a dreadful din under the roof, like the braying and cracking of battle, until the Maharajah's soldiers came, astonishingly fierce of wax and whisker but above all careful not to harm Asoka, who was expensive, or the crowd that was cheap but not unfriendly in its own way.

The soldiers made a vast and most important counter-demonstration. They brought three bugles into action. They fired blank volleys; and in the pauses of that startling din they made the vast roof thunder with reverberating martial commands. And being well drilled, they avoided danger, which was excellent example. There began to be plenty of room for Asoka. Havoc fully finished, and the noise being intolerable, Asoka glimpsed the sunlight in the entry and went avalanching forth in quest of a less nerve-wracking field of battle.

Some said afterwards that Quorn shouted on the way out, though others doubted that, and Quorn never remembered. But all agreed that he had raised his right arm, as if his right hand held an ankus, and that his gesture, position, attitude were those—exactly—of the Gunga sahib, he who rode the elephant amid the broken carving of the end wall. It was agreed by all, including many who did not see it and who therefore knew much more about it, that all he lacked to make resemblance perfect was the funny little howdah up behind him. His smashed helmet looked exactly like the Gunga sahib's turban. His coat was gone; he had thrown it away; he sat in flapping, loose, bazaar- made shirt-sleeves. People who believe in such nonsense as reincarnation and destiny may be excused for having stared hard at the carving on the wall. There is no law against comparing one thing with another. Men, whose stalls and goods and money have been smashed into an uninsured and eggy chaos, need some sort of superstitious comfort to help them endure it. There was grief, but there was no wrath, in the wake of that awful event. It was karma, grievous but inevitable.

"Patience bringeth peace," observes the commentator on the Laws of Manu. "Anger aggravates. Be gentle, O ye sufferers, lest worse befall you."

ASOKA went ahead, up-street, in straight spurts. He was growing winded. Nearly a score of dogs ceased licking sores and scratching their verminous pelts, to let themselves be swept into the current of excitement. Asoka became the pursued. He hated dogs; but an offensive, uninvited, unclean pack of yellow curs, each in a little dust cloud of his own, ears up, tail between legs and anatomy tautened in spasms of energy, yelped at his heels. It was enough to make a herd of elephants hysterical. Asoka went in search of solitude. He deserted the city.

It was the sort of day that might have almost tamed a locomotive, so hot was the sun. The very palms and mangoes seemed to cast a shriveled shadow. Sound itself fainted with weariness. Sweat died still-born. Dust enwrapped everything. Asoka's ton- weight footsteps fell on silent earth. He was a great gray ghost bestridden by a wraith, dry throated, talking to himself.

"Crashing the gates o' death, I'd call it! He ain't thinkin'. He ain't lookin'. All he's doin' is to get the hell from here. He don't care where he goes until he hits what stops him. Wish I was in Philadelphia!"

But it was no use wishing. One had to do something. There was a wall in the distance—a good, high, solid looking stone wall that should stop a steam-roller. Quorn decided he would try to guide the elephant straight at the wall. It might be possible. The brute was getting dog-tired. Quorn remembered how short- sighted elephants are. A sort of instinct told him what to do. If he could get near enough to the wall there were overhanging branches; he could grab those and swing himself up to safety. He began to urge the elephant, not guessing that his voice might stir the monster to a last tremendous effort. But it happened.

They went at the wall like a battering ram, and the wall was rotten. There was a shock that almost threw Quorn over backward. The wall shook, tottered, and fell inward into dusty heaps. Asoka swayed into the gap, then staggered forward, stumbled on some masonry, and fell. He lay sobbing, heaving, near enough to an artificial fish-pond to smell water and too spent to reach it. Quorn was pitched into a woeful heap and rolled into the pond, among the frightened frogs. He felt mud on the bottom; it frightened him, although the water was not very deep. He groped for something to take hold of—heard a voice and touched a hand. It was a little one—a woman's or a child's. He seized it. Then another, stronger hand took hold of him and he felt himself dragged to dry land.

"Will you kindly let me use my lip-stick?" said a woman's voice, in English. He discovered he was still holding the small hand, and there was something in it, so he let go. Then he began to be able to see distinctly, and it occurred to him at once that he was probably dead, because he had never even dreamed of such a girl as this one. She was using her lip-stick calmly, making faces in a tiny mirror; and what with her pale-blue dress, and her eyes, and her sandaled feet, and dark hair, she was so lovely that he blinked at her speechless. Quite unconscious that his middle finger had been smeared with lip-stick carmine, he began scratching his forehead. Were those stories true, that his mother had told him about angels, when he was knee-high to her apron- string?

It was the voice of Chullunder Ghose that brought him back to earth. He recognized that instantly.

"Sahiba, solitude has taken wings, like easy money! This babu advises you go home."

Quorn turned to stare at him—fat, bland, imperturbable, but vehement. He was a man with a plan, one could see that. It occurred to Quorn he might be interrupting an important interview. He removed his battered helmet from respect for a lady's presence, then felt at his head and discovered his skull was almost baked through by the sun's heat. His eyes wandered; he saw a shawl of golden gauzy silk that hung from a branch of some shrubbery. He was afraid of the Indian sun; without stopping to think whose the shawl might be, he seized it and bound it on his head like a turban. Then he turned again toward the lady, and for the first time she was able to observe his eyes and the crimson caste-mark he had made unconsciously above them with his lip- sticked middle finger. She uttered an exclamation, almost screaming. Quorn hastened to reassure her:

"You've no call to fear me, missy. Me and him committed trespass, but we didn't mean no harm."

He turned from her to look at him—Asoka, sobbing and tossing his trunk in futile efforts to reach water. "Hey, you," he ordered the babu, "panee lao! Fetch a bucket quick, he's famished."

Chullunder Ghose merely gestured toward some bushes, where Quorn spied an expensive, imported watering can that had been abandoned among the flowers by a gardener who probably preferred the ancient goat-skin mussuk. Quorn fetched the can and filled it at the pond, then grabbed Asoka's trunk and thrust it into the receptacle.

"There, ye darned old ijjit, suck your fill an' sober up."

The water vanished, to be squirted down Asoka's dusty throat while Quorn refilled the can. A second and a third dose went sluicing down the same course. Then Quorn himself took a drink, and the relief it gave him stirred imagination. He sat down on Asoka's forefoot.

"There, don't carry on. 'Tweren't your fault. And it weren't my doing neither. Quit your grieving. There's been no harm done that money can't set right again. There's always somebody got money. You're all bruised up, an' you're scared, but you've had your fun, so now act sensible."

Asoka seemed to recognize the note of friendship. He left off moaning. He even touched Quorn's shoulder with his trunk. But his eyes did not lose their madness until Quorn began talking to him in the native tongue, remembering the phrases he had heard mahouts use when their charges were ill-tempered or in trouble.

"Prince of elephants! A prince, a maharajah, of the hills, a bull of bulls, a royal bull! Did they offend him? He shall have a howdah made of gold and emeralds! They shall paint him blue and scarlet! He shall lead the line of elephants! He shall carry kings on his back!"

The poor, bewildered brute responded, swaying his head to and fro and permitting Quorn to rub the edges of his ears. He gurgled for more water. Quorn persuaded him to rise and led him to the fish-pond.

"In you go, you sucker!"

He was obeyed so swiftly that a dozen fish were splashed out on the wave displaced by four descending tons. Quorn picked up the fluttering fish by the tails and tossed them in again. Reveling amid the ruin of the lotus plants, Asoka lay still. Quorn began to wonder what to do next.

"I'm the only friend he's got on earth this minute. They'll shoot him sure, unless I take the blame for all that damage. Maybe I'd better talk to that babu."

He followed the sound of voices, peered between some shrubbery and saw the babu squatting comfortably in the presence of the lady. She was seated above him, on the marble railing in front of an exquisite garden-house. Her eyes, as she watched the curl of the smoke of a cigarette, were half-hidden beneath languorous, dark lashes that somehow failed to conceal excitement. She had pearly skin, with just a hint of color, and the great dark pearls that she wore as earrings beneath a turban of cloth of gold were like drops of the juice of youth and life exuding from her.

"O daughter of the moon," the babu argued in his mellow baritone, "this may be wonderful, but is it wise? Suppose these garden walls have ears?"

"They have," she answered, "but they don't understand English, so say what you like, except that you mustn't contradict me."

"Heavenborn sahiba, may this babu talk of commonplaces? If the question may be forgiven, does it not occur to your superb imagination that this situation is desperate? This babu will be accused of aiding and abetting your escape. Not only shall I lose my perquisites, but I shall be caused to eat slow poison—ground glass probably."

"Yes, any fool would know that," she retorted. "Use your wits then, babu-ji."

"But, daughter of astonishment, I have no wits for such a situation! She, on whom his eighteen-gun-saluted majesty of Bohutnugger chooses to bestow his royal heart, has fled from the parental roof! His emissaries will insult your royal parent in an expert manner. Who could forgive that? It is not that your royal parent really minds your modern views. I think he secretly enjoys them. But he has to think about the priests, who are scandalized. And a scandalized priest is a serious matter! How can you get away from here? There is no way. To remain here is to be discovered. And discovery means—O Krishna, what does it not mean? It means shame, sahiba. Your royal parent—"

She interrupted him: "He is like a parent in somebody's novel. It could never occur to him how ashamed I would be if he could force me to marry some one I had never seen. I wouldn't love such a man, not even if he were so lovable that it would kill me not to love him."

"Krishna!" the babu exploded. "In addition they will blame me for providing you with modern books! They will blame me with excruciating details such as hunger in a dungeon! Probably your father will incarcerate you until you agree to be religious and become a temple ministrant."

"Oh no, the priests wouldn't have me," she answered. "You see, they know I know too much. Either I go to America, or—

"Do you know where America is?" he exploded. "Do you know about the Quota, how they count heads and reject all immigrants who are not respectable? Unmarried but beautiful ladies are never respectable in U.S.A. United States. How will you get as far as Bombay? You have neither clothes nor money for such a journey."

"That is for you to attend to," she retorted. "I have made up my mind to be independent. I have run away. I have done my part. Now you attend to your part."

"Krishna! Who shall explain things to a woman?"

"There is no need for explanations. Either take me to America, or else accept this destiny and—

"I tell you, there is no such thing as destiny," the babu interrupted. "That man is a common laborer—"

She made a scornful gesture. "What of it? You are a common babu. I am a common princess. If, as you say, there is no such thing as destiny—

"Damn destiny!"

"I see you are after all only a boastful rogue," she answered. "You are not really an adventurer. You are afraid. Very well, you may leave me. I will manage my own affairs."

Chullunder Ghose sighed. "Honesty is rotten policy," he remarked with an air of finality. "I have honestly tried to dissuade you. As a dissuadee you are a failure. Very well then, let us succeed at something. What do you wish me to do?"

She threw away her cigarette and lit another one, and though there was mischief in her smile, there underlay the mischief something that looked dangerously like intelligence. There was a bit of a frown, like a vague cloud on her forehead. There was a certain not unpleasant firmness of the lips. At the back of her brilliant eyes was something more than mere audacity.

"Does he, or does he not resemble Gunga sahib?" she demanded. "Do I, or do I not resemble Sankyamuni, whose namesake I am? Did he, or did he not come on an elephant and find me in a difficulty? Let us take advantage of it."

"Do you know what the risks are?" the babu asked her. "It will be you, and I, and this man Quorn, whom neither of us knows, against a universe!"

"Cheese it!" said Quorn to himself. "It's in my contract not to interfere with native women. That lets me out."

He stole away silently, back to Asoka who was enjoying himself in the pond.

"Come on out, old-timer," he commanded. "Me an' you are in trouble enough without extras. I reckon I need a friend as bad as you do. Out you come. No sulking."

But Asoka was not yet quite amenable. He came out, but he stubbornly refused to face the gap in the wall. Quorn decided to look for a gate, and the elephant followed him meekly enough around a clump of bamboos, along a pathway. There were vine- covered arches at intervals; the big beast knocked down two of them, but there was no return of panic. They arrived, around the corner of an empty house, at a stone-paved stable yard where ancient vehicles and rotting lumber were crowded in confusion. Along one side there was a shed, in which Quorn spied new-cut sugar-cane. He made Asoka lie in mid-yard, broke a rotten door and appropriated as much of the cane as he could carry.

"There now, that's for being daddy's good boy. Eat it, and we'll go home."

He left Asoka munching sugar-cane and went in search of a gate that might open on the main road. He found one, but it was fastened with a lock and chain and he struggled with that for fifteen minutes, trying to smash the padlock with a stone, until it suddenly occurred to him that he could lift the light gate off its hinges. Then he hurried back, for fear Asoka might be up to mischief. But it was not Asoka. He had already become a mere lay- instrument of mischief.

There were servants on the scene—three gardeners. The princess was directing operations. Chullunder Ghose, as muscular as all three gardeners in one, was helping to drag out through a stable door a funny little ancient howdah and some rat-gnawed harness that had to be moistened before it would bend. The howdah was crimson and in fairly good condition; there was only room for one person in it. It had four upright poles that supported a gilded roof, precisely like that on the howdah borne by the elephant carved on the wall of the market-place. The gardeners were afraid to approach the elephant, so Chullunder Ghose kicked them with astonishing force and agility. Then they started to try to lift the howdah to Asoka's back.

There was only one thing to be done, because nobody took the slightest notice of Quorn's protests. Unexplainably, but definitely that was Quorn's elephant. The equation contained plenty of unknowns, but pride was a basic element. He felt responsible; he could not have the elephant misbehave himself. So he went to Asoka's head and kept him quiet while the unaccustomed crew toiled at the howdah and finally strapped it in place, Asoka heaving himself without a protest, to let the great buckles be passed under his belly. Then the babu drove the gardeners away, commanding one to unlock the gate and another to fetch his pony.

"It is dangerous," he said. "Sahiba, should this elephant misbehave himself, then the harness will break, and—

"We have nothing to lose," she interrupted. "If the gods have a sense of humor—

"But there aren't any gods," said the babu.

"So much the better," she answered, "we needn't give them a thought. We shall know in an hour whether we also are nothing at all. It is all we can do. It is all or nothing."

She turned and smiled at Quorn. He was aware of being analyzed—read like a book. He was vaguely offended. But for his pride in having tamed an elephant he would have bowed to her and walked away. When she spoke to him after a moment her voice was rich and low, and there was humor in her eyes, but that only increased his suspicion and made him feel obstinate.

"Did anybody ever call you Gunga sahib?" she asked him.

"No, Miss."

"Many people will, from now on."

"My name, Miss, is Ben Quorn."

"We are destined, I think, to be friends, Mr. Quorn."

"No, Miss, I believe not. I was sworn before a notary to avoid all women for as long as I'm in India."

She became immediately serious. "A vow?" she answered. "Nobody should dare to try to break that. I am sorry. Is it out of the question for you to escort me to the palace?"

"No, Miss."

Quorn felt disarmed. He was not at all sure he had answered her wisely. She was a heathen. She was in league with a babu whom he had been warned not to trust. He did not understand their game, but he had overheard enough to realize that their conspiracy included himself in some way. Still, there was no harm in taking her home, he supposed. Afterwards, he would return Asoka to his picket in the compound; and if she and the babu could involve him any deeper than that, they would have to be mighty clever.

He made Asoka rise. The babu dragged a ladder from the shed and set it up against the howdah. The princess appeared to expect Quorn to offer a hand. He felt it would be surly to refuse that. She hardly touched his hand. She was as active as a kitten. But that one touch affected him strangely. It was not exactly thrilling; it was confidential; it made him feel as if she trusted him. And then the babu's manner also produced an effect that thoroughly disturbed Quorn's self-command, although he did not realize it at the moment. He was conscious of the babu watching him intently. A suspicion stole into his mind that Chullunder Ghose expected him to use the ladder in order to get to his seat on the elephant's neck; in other words, the babu knew him for an amateur.

"Take that dam' ladder away," he ordered.

All or nothing, eh? Well, they were not the only two who could accept that gamble. He had seen mahouts mount scores of times, and he knew the right word of command. He went and stood beside Asoka—spoke, low voiced—and was obeyed. Asoka curled his trunk around him—it was like being gripped by a python—raised him high in the air, where he felt for one agonized moment as if he were doomed to be smashed into pulp on the ground—and then set him in place exactly, gently, astride the broad neck with his back to the howdah.

Chullunder Ghose had found an ancient ankus in the shed to which he had returned the ladder. He gave it to the elephant, who passed it up to Quorn.

"To the manner born!" said the babu. "It is too bad you are honest. Good mahouts are rogues, invariably. Honesty is dam-bad policy, believe me, I have tried it!"

"Silence!" the princess commanded. "Don't annoy him." And again Quorn felt an unfamiliar emotion that intrigued him strangely, even while it increased his sense of danger.

A gardener brought the babu's pony. He mounted, opened his black sunshade and led the way, hugely incongruous, riding with wonderful dignity and yet, somehow or other, a clown. He was play-acting. Even the bewildered Quorn could see that. A dramatic impulse seemed to seize them all as they passed out through the opened gate into the road, Asoka swaying homeward with the stately pageant-stride that durbar elephants all learn and always use unbidden, as if by instinct, when there is importance in the air. Quorn sat upright, with the butt of the ankus resting on his thigh—coatless—in a bazaar shirt, somewhat soiled—in a yellow turban—with a crimson caste-mark on his forehead. And his agate eyes were luminous with wonder that suggested mystic and inscrutable design, unless one knew what thoughts were surging through his puzzled and suspicious brain.

QUORN was a fellow whose thought took the definite form of words before it meant much. He seldom—almost never muttered to himself. But he carried on a conversation in his brain, which was the same thing plus reticence. He liked to dig at problems, almost in the way he used to dig graves, shovelful by shovelful, one thought at a time and no hurry.

"This here old prodigal son, he needs a massage and a hot towel. Reckon I can lie him out o' trouble somehow. Elephants are elephants. He's easy. But the rest of it smells to me like politics. This ain't a circus."

But it did look like a circus. All Narada seemed to be pouring along the highway to discover what had happened to Asoka. The crowd was excited, hot, breathless, expecting something terrible, and in a mood to be thoroughly entertained by almost anything, so be it staggered imagination. The sun shone through the cloud of dust they raised, on to a drunken riot of color all in motion. And the crowd beheld a miracle. There was no doubt about that whatever.

When Asoka had burst forth like a typhoon through the city, he had had no howdah on his back. When Quorn had ridden forth, he had had no turban on his head, no ankus and no caste-mark. There had been no princess in any way connected with the incident. And yet, here came the elephant, moving as if impelled by dignity and destiny combined. On his back was an ancient crimson howdah, such as nobody had seen in use for generations. Riding in the howdah was a gloriously dressed and radiantly beautiful young woman, unveiled. No one in the crowd had ever before seen her face to face, because the purdah custom had prevented that. But everyone had seen the carving on the market wall. What should not a breathless crowd believe—the more incredible the better?

Furthermore, there was the loud voice of Chullunder Ghose, riding ahead and shouting to them in their own tongue:

"Way there! Way for the Wheel of Destiny! The gods now finish what the gods began!"

Could anything be simpler? Could anything be more authentic? Why should anybody not believe it? Up went a roar of recognition—such a tumult as perhaps Darius heard when multitudes acclaimed him King of Kings.

"The Gunga sahib! The Gunga sahib and the Princess Sankyamuni!"

Messengers were sent post-haste to warn the priests of thirty temples that a prophecy was coming true at last. And there is competition among temples. It was almost like Lindbergh coming home to the United States, such streams of rival welcoming committees raced to be first to pay official honors. Priests turned out in hundreds with bands of music. They choked the road. Asoka had to slow down. It was all that Chullunder Ghose could do, using his lungs and his wits to their utmost, to get the crowd moving again. And the delay gave time for garlands to be brought—long chains of flowers that were tossed to Quorn, that fell draped on Asoka's shoulders and all over the crimson howdah, until the Princess looked forth from a perfect bower and Asoka trod crushed blossoms underfoot.

There is nothing so convincing as flowers, unless it be a procession behind bands of music. Through Narada's streets there surged such a procession as those ancient buildings had not seen for centuries. The sacred peacocks screamed from garden walls. The sacred monkeys jabbered and grimaced from trees as green as jade. And Quorn sat silent, wondering, aware he was the hero of it all, but not at all enjoying the heroics. He was more contemptuous than actually timid.

"Heathen!"

It was a heavy iron ankus that he held. He could have thrown it and easily hit the babu. It was tempting to do that, and he never really knew why he didn't.

"He's making a monkey of me. Well, I'll fix him afterwards."

He almost forgot the Princess, until she called to him to take her to the palace. Asoka had been following the crowd, that flowed toward the center of the city where the larger temples stood. But Chullunder Ghose led up a winding street toward the park-like suburb where the palace was. Asoka obeyed the pressure of Quorn's knee; so that the order of procession became suddenly reversed, Asoka leading and the crowd surging behind him. That gave Chullunder Ghose a chance to gallop forward as fast as his overburdened pony could set foot to earth; and by the time Asoka reached the palace the babu had interviewed the Maharajah, who had evidently had quite a number of brandies and soda as a sequel to the morning's accident. Sober, he would very likely not have dreamed of doing it, but he was decidedly not sober. He donned his royal robes and jewels. And he came on foot to meet the thunderous procession at the splendid entrance gate.

The crowd heard nothing, because the crowd itself was making too much noise. But the crowd saw, which was the all important point. It saw the great gate close behind Asoka, as if destiny had turned a page and was about to write new history. Perhaps it was Chullunder Ghose who put the thought in some one's mind. He was certainly not in the palace grounds when the gate closed. At any rate, somebody started a shout going, and it caught on, in little explosions, until the whole crowd roared in unison and the Maharajah's brandied face grew darker with concern.

"Bande Sankyamuni! She is free! She is free! This time the Gunga sahib did it! She is free! She is free!"

Less than a dozen priests and half-a-dozen members of the crowd had managed to follow behind Asoka before the gate was shut tight by the Maharajah's servants. The priests had promptly grouped themselves around the Maharajah, to prevent him from feeling or appearing too important. He turned toward them, and they were as baffled as he was. He spoke a few words and they answered in whispers. Then he shrugged his shoulders. He appeared not altogether unhappy. He sent somebody running toward the palace, and went on talking with the priests until a group of women from the royal zenanah came and waited on the Princess. Quorn made Asoka kneel. The Princess almost jumped into the arms of veiled, excited women who flung a silken sheet around her and then hurried her away.

Quorn remained on Asoka's neck. He doubted what to do next. But he knew exactly what to do when he saw the Maharajah start toward him. He would hold his tongue. He would not tell what had happened. It was none of his business.

The Maharajah came as close as he could get. He examined Quorn's eyes. For a minute at least, they stared straight at each other in silence, Quorn's resentment gaining, until at last the Maharajah spoke, in good plain English, awkwardly pronounced:

"Well, well. You're a strange coincidence. You realize, of course, that you'd be an impossible nuisance in Narada? You must go home. How much shall I give you?"

That was the first really great moment of Quorn's life. It was the first time that anyone ever had offered to bribe him. Instinct warned him that heroics was the one thing to avoid.

"This elephant's in trouble, sir," he answered. "I've a contract job here, I'm not going to the States, so forget it. You protect this elephant, and I won't trouble you. If they should shoot him—"

"Shoot him?" said the Maharajah. "I would kill the man who did it! You must go home."

Quorn fell on silence, closing his lips grimly.

"But you see," said the Maharajah, "you don't know India. It mightn't be healthy for you after this. There are more ways of dying than there are of living. Has that thought occurred to you?"

"As long as I mind my job I reckon I'll be safe enough," Quorn answered, and the Maharajah stared at him again at least a minute. Then he lighted a cigar, strode to and fro a dozen paces and resumed the stare.

"You're a damned strange coincidence," he said at last. "Can you manage that elephant? Can you return him to his picket? All right, do it. I will send a man to talk to you tomorrow."

Somebody opened the gate. Asoka arose and headed homeward, passing through the dense crowd outside like an alibi through circumstantial evidence. The crowd roared. Hundreds followed through the winding streets. But there was new news; something else was stirring, and by the time they reached the compound where the other elephants stood swaying at their pickets Quorn had no more than a following of small boys and a few dozen caste- less women. Some police drove them away. The head mahout attempted to get rid of Quorn as easily. Quorn smiled. He could show an eye-tooth when he did that.

"You send a man for my servant," he answered. "Moses is to fetch my supper here and bring a cot too. I sleep here. You understand that? Right alongside of Asoka. Now don't argue. Do it. Would you care to kiss that?" He showed the man the tightened knuckles of his left fist. "Something's happened to me," he remarked to himself, as he watched the head mahout despatch a messenger for Moses. "Somehow it's the same day. But I'm not the same man."

SUNRISE discovered Asoka munching an enormous loaf of hot bread and Quorn drinking tea on a chair within ten feet of him. He was reading a five-cent book entitled Maxims of Napoleon. He had no use whatever for the Corsican. He considered him a scoundrel. What puzzled and intrigued him was that such a scoundrel should have been so philosophically wise.

"A guy who didn't have to be a king, but went and was one—a guy who might ha' been a poet, but who went and was a politician—a guy who could have had it easy, and who went to Roosia—just imagine that—was crazy. He was as crazy as this here elephant was yesterday. He ran amok through Europe. Yet he talked wise. Get this one: 'It is much wiser to despise the judgments of certain men than to seek to demonstrate their insignificance and versatility.' True, ain't it? Yet the guy who said it lets the English ship him off to St. Helena jes' as simple minded as a communist asking the cops for board an' lodging!—It 'ud be like me if I should ask that balm for an introduction to an easy billet."

That last thought was brought into being by the sight of Chullunder Ghose on pony-back, riding toward him. Quorn stuffed the booklet in his pocket and studied the man. He noticed that the pony was tired. The babu needed shaving. He dismounted without betraying fatigue, but his eyes looked as if he might have been up all night. Somebody brought him a chair. He demanded a cup and saucer and drank some of Quorn's tea while they stared at each other in silence.

"I wouldn't trust you," the babu said at last, "with one small secret. You're a moralist. You believe in righteousness. Same is the excuse which solemn nobodies depend on to explain their unscrupulous acts. You are a prig with irreligious eyes—in other words a fraud. I get you."

"What would you call yourself?" Quorn retorted, charging his pipe with his thumb.

Chullunder Ghose finished the tea and then stared at the leaves in the teacup before he answered:

"Mark Twainian definition fits me as its own skin fits a herring. An honest man, said Mark Twain, is a hellion who will stay bought. That is what is known as verb sap."

"Uh-huh? Some one bought you lately?" Quorn asked.

"No, not lately," said the babu. "I could find no purchaser. So I bought myself—long ago. I paid a high price. And I have stayed bought like any other trouble that was in the market."

Quorn stared, smoking, leaning on his elbows. He signed to a mahout to bring grass for Asoka.

"Go on," he said. "Are you the man that Maharajah said he'd send to talk to me? I'm listening, but I'm believing nothing."

"Good, then I can tell the truth." Chullunder Ghose opened his black sunshade and balanced it over his shoulder against the rising sun. That gave him an advantage; he could watch Quorn's face, whereas his own was in shadow—not that Quorn cared. "The truth is only dangerous when somebody believes it," he went on. "I was cheap at the price, and the price was a high old time, by Jiminy. I have had it. And there is worse to come."

"Says you."

"Yes, best time ever. Good time depends on upsetting equilibrium of status quo and vested interests, like bull in china-shop. Everything else is mere morality. You had a good time yesterday. So did the elephant."

"Uh-huh?"

"Yes you did. You didn't know it, that's all. Soft snap now is staring at you, but you can't see."

"I can see you're a crook," Quorn answered.

The babu nodded. "That is what exasperates me," he admitted. "You have enough intelligence to see that, yet you lack imagination. You, with your advantages! Excuse me if I smile. It is to save myself from weeping for you hypocritically. Hypocrisy is the only vice I don't permit myself."

"Advantages? Me?" Quorn thumbed his pipe and lighted it again. "If you knew, you wouldn't talk such boloney. I was a poor lad. Mother took in laundry. Since I was fourteen I've had one mean job after another, on account that my eyes scared even me when I looked in a looking-glass. I've got me a sort of education, but it gets me nowhere. You don't know what tough luck is."

"Perhaps not," said the babu. "I was only failed B.A., Calcutta University. I was expected to raise a family on Rupees thirty- five per month less fines for indiscretions. Am indiscretionist by nature. Solemn stupidity stirs my soul to Rabelaisian amusement. There were so many fines in consequence that I was owing the treasury money every pay-day. I assure you a sense of humor is a bad thing for a failed B.A., in a country ruled by white man's burden-bearers. Once the English get to India they seem to think that Rudyard Kipling wrote them; so unless you can get them to laugh at themselves they are so self-conscious that they creak like rusty bed-springs. Only one in two dozen can laugh at himself; that makes all the rest regard him as a bounder, so he has no influence. It was no use. I had to eschew respectability, and I have been happy ever since, all things by turns and nothing long, like U.S.A. American politics. I have been wayside conjurer—secret service agent—salesman of spells and potions—twice to the United States as lecturer on magic—twice deported on the ground of too hot competition with the native clergy—twice to Tibet—twice around the world. I know eight languages, Charlie Chaplin, Trotsky, Aimee Semple MacPherson and Albert Einstein. I have owned a hundred thousand dollars in actual money for several months. I have been in jail in seven countries. I have had a Chinese mistress and a Jewish secretary. I have been the intimate friend of men and women who walked this earth like gods. And I have been patronized by pompous and expensive nobodies. I have been to a garden party at Buckingham Palace, where I was mistaken for a Maharajah. I have been up in airplanes, and down in submarines. I have been condemned to death twice by angry governments and kissed on both cheeks by a Frenchman. I was run out of Russia, bare-footed over the snow through a forest, on an empty stomach. I have dined on ortolans in Paris, on rotten eggs in Pekin, and on raw wind to the northward of Lhassa."

"You seem to have seized your opportunities," said Quorn incautiously.

"They seized me." Chullunder Ghose paused. "I was a tidbit in their talons." He paused again. "But never saw I such an opportunity as this one."

"Purchasing agent, eh? I don't doubt there's graft. Watch out you don't lose your job."

Chullunder Ghose smiled, as one would at a child who spoke ingenuously. "Graft?" he answered. "Graft is for such as would cheat themselves at solitaire! Myself am cosmic opportunist, eager for gargantuan enjoyment. Graft is mouse-trap bait. It catches little mice like moralists and hypocrites, who are the self-same leopard with the spots exaggerated. No self-respecting immoralist could condescend to be a grafter. Graft is a system of petty rewards for pikers, such as noblemen, politicos and similar mistakes of nature. Graft is self-humiliation on the easy payment plan. Are you a grafter?"

"No," said Quorn, "I never had a chance to graft but once. I passed that chance up. Not that it's any o' your business."

"Graft," remarked the babu, "is the grave of opportunity. But perhaps you don't know a verb sap when you see one. Did you ever hear of the boy who struck the winning blow at Bunker Hill?"

"No, never heard of him."

"Have you heard of the cow that kicked the lamp that burned the house that Jack built? Have you seen Chicago? All due to a cow! Have you seen London? All due to a baker's ash- box—Pudding Lane to Pie Corner, all one ash-heap—all one cosmic opportunity. But perhaps you don't know history? Have you heard of Mahatma Gandhi's false teeth? He has had them made for him in prison by an expert dentist, as a signal that he means to starve himself to death. What do you think of that one?"

"I'd call that contrariness o' disposition."

The babu looked grieved by such stupidity. "Contrariness," he said, "is your complaint, Gandhi is a G. B. Shaw in bathing trunks without the whiskers to get in his way. He would rather die than lose, and he looks like losing, so why not die spectacularly? But if he wins, he's in training for dinner; he'll need teeth, so he gets some good ones. Gandhi is pure paradoxist. You are prudish, Pollyanna-minded quidnunc. You have been in training during many lean years to embrace an opportunity, and here is opportunity. You seem to think it is an opportunity to fiddle while India burns! You are a cow with a lamp all ready to be kicked, but you let it burn you instead of the barn! You have a chance to be a corner-stone of history. You can be laid with dignity, good humor and perhaps with profit. You prefer to be a Maharajah's goat, deported to save him trouble!"

That was a shrewd thrust. Quorn stiffened at the thought of that indignity.

"What's your lay-out?" he demanded. And he knocked out his pipe on the heel of his boot—a symptom that the babu noticed, analyzed and remembered for future reference. For the moment the babu merely remarked:

"It seems a pity they should shoot this elephant."

Quorn swallowed that too, hook, line and sinker. "Who says who'll do that? The Maharajah said he'd kill any one who dared try to shoot him."

"O-o-oh?" exclaimed the babu. "O-o-o-h! So you're as innocent as all that? You should go back to the U.S.A. United States and vote for prohibition! Do you really believe—that the word of a prince—in a tight place—is a rain-check? It is as breakable, I tell you, as the Ten Commandments! It is as worthless as a bankrupt's promissory note! It is worth exactly as much as a priest's forgiveness! That a man with such eyes as yours should be so innocent! Oh, what a life! What disillusionments! What waste of energy and plasm, that evolution, in a billion years, should breed no better than the face of Gunga sahib with the brains of a lump of institution pudding! That I should live to see it! Ignominy!"

"Whose ignominy?" Quorn demanded. He was skeptically curious. His wits were in low gear, racing to ascend to heights of more Olympian comprehension.

"Mine—-mine—mine!" said the babu, almost tearfully. "Should I give a damn for your ignominy? Besides, you haven't any. To have ignominy, one must have intelligence and self-respect. It is otherwise as marmalade to moonshine—neither is even aware of the other. Oh, the shame—the shame of it! I said to her, you have imagination. I staked my intelligence on it. I said: 'sahiba, there are no gods. There is no such thing as destiny. There is a word that covers this, which only Germans or the Chinese could appreciate—Comicosmiccoincidentalfortuity. The Law of Improbability, that governs the drawing of sweepstake tickets, has functioned. Unworthy aggregates of atoms though we are, Humor has attracted to us some one who would rather die than double- cross your Highness.' She did not know what double-cross means. I told her that to you the word means worse than alimony, worse than bugs in boarding-houses. I said 'Ben Quorn will desert neither you nor the elephant, whatever happens.' Oh well—I eat ashes. It is not the first time."

"I believe you'd double-cross your own self, you're that crooked," Quorn answered. "I wouldn't take your word for twice two. But she's a right nice young lady. I wouldn't see harm done to her, if I could help it. But I'd have to have her word on it. I wouldn't take yours. Have you come from her or from the Maharajah?"

"Am diplomatist," the babu answered. "Same means double-headed eagle looking both ways, sitting on two horns of a dilemma and on both sides of a fence. It isn't easy. However, the word is all over the City that you are Gunga sahib. It is very funny. The Maharajah was drunk when he met you at the palace gate. But he was not yet too drunk; and I had whispered to him. So he asked those priests who forced their way in, whether or not you are Gunga sahib. They said Yes, because they had no time to think; the crowd was demonstrating, and I was outside telling the crowd what words to yell. It happened he was very angry with the agents of the Maharajah of Bohutnugger, who have been giving themselves great airs and demanding too much money. Therefore what I whispered to him sunk in. Being drunk enough, he sent a scandalously unimportant messenger to tell those agents they may go home, seeing that his precious daughter is now next thing to a goddess and therefore much too good for such a brute as Bohutnugger."

"What's wrong with that?" Quorn asked. "She doesn't have to marry Bluebeard. Sounds all right to me."