RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

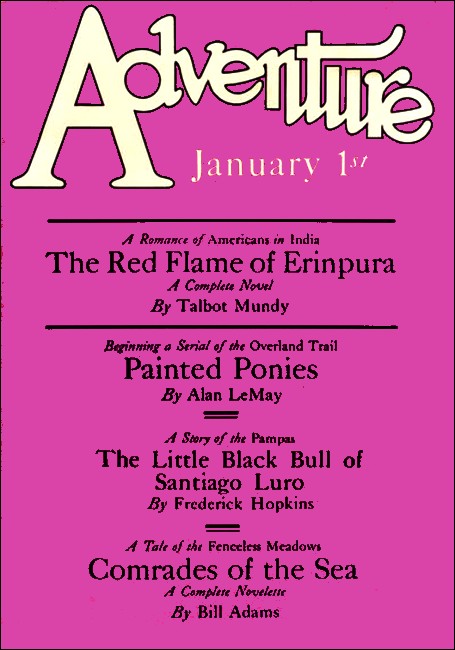

Adventure, 1 January 1927 with "The Red Flame of Erinpura"

THERE was a voice outside, and nothing else except the creaking of an evenly pulled punkah-cord that passed through a piece of gas-pipe in the wall into the only other room. On the mat on the floor, and under it, were scorpions, so that if a man rolled off the bed he had to pull his boots on, having shaken them to make sure no kraits were lurking coiled up near the toe. And over the rust-stained ceiling-cloth there raced an endless series of rats which seemed to know exactly where the cloth was rotten.

According to his own thermometer, bought from and guaranteed in writing by a Bombay cheap-Jack, John Duncannon's temperature underneath his tongue was one hundred and nine and a half; therefore, he doubted everything, the scorpions included. When he took the thermometer out of his mouth it rose steadily to one hundred and thirty-two degrees Fahrenheit, as he ascertained by laying it down on the bed and resting his chin on his elbows to keep his head from shaking.

"I don't feel dead," he muttered. "Still—this might be hell. I wonder how I got here?"

He stared at the bare stained stucco walls and could see nothing about them that was in the least familiar. There was a framed notice printed in two languages tacked to a door that led into the other room. He had looked into the other room. It was exactly like the one he occupied, with a similar pair of caned cots, four chairs, two wash-stands, coconut fibre mat and teak-wood table. The exertion had made his head swim so that he could not read the printed notice. Anxious not to fall on the floor amid the scorpions, he had returned to the bed, on his way taking the thermometer out of the kit-bag on the table.

He recognized his own baggage, or at any rate most of it, lying about on the floor. There were two rifles in leather cases and a shot-gun in a canvas sling, a small trunk, a suitcase, an awful thing the English call a hold-all—which could not be made to hold anything and keep its shape—and a bag containing books and papers. There was also a genuine Mexican saddle screwed up in a wooden box—or at least he supposed the saddle was inside the box, and even found enough mental energy to hope that it might be. Somebody must have opened the suitcase, because he found himself lying in pyjamas; and his clothes were on the table, rather neatly folded. He had looked at the watch which had stopped at 12:30, but whether noon or midnight, or how long ago, there was no guessing.

Within easy reach, on a chair beside the bed—which was spread, by the way, with his own blankets—was a half-filled whisky bottle and a chipped enameled jug containing tepid water. There was no tumbler, but there were fragments of glass on the floor under the bed.

A door led out of the room, apparently to a veranda, but it was locked from the outside and so, apparently, was a similar door leading to the same veranda from the other room.

There were beetles swimming in the water in the jug, and the cork being out of the whisky-bottle, quite a lot of ants had drowned themselves in that. The beetles that swam were devoid of all sense of direction, so it was difficult to rescue them, what with his hand shaking and one thing and another, but he got most of them out at last and found when he gulped the warm water that he could think more definitely—although either the taste of the water was horrible or else—

"Was I drunk?" he wondered.

He believed not, although he was not sure. For one thing, he habitually drank so seldom and then so temperately that there was almost nothing more improbable than that he should drink himself unconscious. But on the other hand, there were those incredible scorpions on the floor. He blinked at them. And then there was the voice outside—one that he was sure he had never before heard.

"Am I in jail?" he wondered.

But the place did not look like a jail. It was neither strong enough nor clean enough. He did not know whether they provided punkahs for the prisoners in Indian jails, but rather thought not; and if they did, then it was likely they would grease the rope where it passed through the pipe in the wall.

The funny thing was that he could not remember anything about the past few days, although he recognized his luggage, knew his name, his home address in Bangor, Maine, and could remember why he came to India. His brain quite readily recalled the circumstance of landing in Bombay from a P. & O. liner whose passengers behaved as if they were the rather weary gentlemen and ladies in attendance at a languid royal court. He recalled that even when you went on deck in your pyjamas before breakfast you did not speak to any one without being first introduced—not, that is, unless you did not mind being snubbed; and the officers seemed to expect you to touch your hat to them.

He remembered it was hot the day he landed, and that when you drank a long drink the whole of your shirt was wringing wet five minutes afterward. He could recall the vaguely insolent official who had examined his passport and passed him out of a corrugated iron-roofed shed into a street that was a splurge of many colours. He had gone thence to a horrible hotel, because the decent ones were full of Englishmen who had made their reservations in advance.

In a hired Ford that had a linen top with bright red tassels he had made the social rounds and left a dozen letters of introduction; and on the whole he had been well received, although it had amused him to discover that, as a person with commercial affiliations, he was not considered eligible for the best clubs.

However, people had been civil; they had invited him to dinners at their homes, and in less than a week he had learned enough from a dozen different points of view to realize that business in India would not be in the least like anything he had experienced anywhere else. Not that the discovery disturbed him in the least; Turner, Sons and Company had not picked him out from a hundred eligibles for nothing. He had come to India to hold his tongue and use his wits; moreover, he was well aware that he had used them fairly shrewdly.

"Then how did I get into this fix?" he asked himself, drinking some more of the disgusting water.

He decided he must have help, though he hated to ask for it until he could feel more self-confident. Not given much to dandiness in dress—in fact, preferring well-worn clothes to new ones—nevertheless, like many other men who loathe the latest fashions, he preferred to appear shaven before strangers. He could feel a three-day stubble on his chin, and his dense, unmanageable, crisp dark hair he knew was like a mop.

For a while he listened to the voices outside; his head did not ache so much since he had drunk about half of the water and he began to hear a little better. There was a squeaky, shrill voice and a baritone one, full, possessing a wide range, resonant and decidedly pleasing. The squeaky voice suggested an unoiled wheel; the other was human and, to an attentive ear, good-natured.

It was at least ten minutes before it dawned on John Duncannon's slowly recovering brain that both voices were speaking English, the squeaky one vilely mispronouncing it, the other mouthing it with evident familiarity and no more than a trace of Oriental accent, but with a peculiar economy of unimportant words.

"Must make," said the strong voice.

"Squeezit? Squeezit? What is that?" the other demanded. New words seemed to irritate him.

"Ignoramus! Obsolescent savage! In what second-handed, six-weeks'-course-in-English-and-perfection-guaranteed bazaar handbook did you pick out your vocabulary like a parrot choosing easy nuts? Gampati! Whoi! Should India swadeshi win, what jargon should we wrangle in? But why quote poetry to persons preferring dunghill snort of swine? Are Burmans persons? Tell me that? Or are they warts on a Darwinian landscape? Hari bol! Have you heard of the U.S. United States—thou, whose skin is like a parchment with the mantrams rubbed off by scratching yourself against shoot-no-rubbish signs?"

"Have heard, yes, certainly of U.S.A.," the squeaky voice answered. "But what is squeezit?"

"Krishna! Surface that thou art of improfundity! Know cricket?"

"Yes. Sahibs play cricket— 'How's 'a-at? A-out! Over!' Bat—ball—run—sweat—tea-time!"

"Baseball," said the big voice, "is cricket without tea-time, played in U.S.A. Biff—yow—pop-bottle on umpire's ear—crowd roars—stand collapses—big man in prison-costume pitches bat at anybody nearest—everybody runs, trying brain everybody else with hard ball—people called fans throw hats from sun-shiny side of paddock and yell 'Slide, you bloody idiot!' Person who did not hit ball—was standing elsewhere—sits down as admonished—slides on rump, heels first, for home plate, arriving one inch ahead of ball, with which man in armor seeks to brain him. That is baseball—hot stuff—very! Have seen. Was in U.S.A. Paid dollars two for seat plus twenty-cent tax. Peanuts extra."

"Yes, but what is squeezit?

"Man of muddy intellect! A squeeze hit is as aforesaid—skin of teeth ahead of ball at home plate. We must do same, ball in this instance being symbol of slings and arrows same as Hamlet suffered, only worse; he, being prince, ate frequently. Thou, mummy of a boh's ambition! Thou negation of discernment! Within, possessed of money and banker's references, also valuable luggage, lies one of unimaginative tribe of gora-log, at present in extremis, which is doctors' way of saying 'e dunno where 'e are."

"Is he baseball player?" asked the squeaky voice.

"Gampati! He is bread, meat, victuals! Thou shadow of the puncture in a sieve! Thou stranded jetsam on the beach of imbecility! He lies within, doesn't he? He is locked in, isn't he? He has raved in delirium, hasn't he? He will wake up, won't he? Well, what is left to us but making squeeze hit and be home first before said white man's wits return and beat us out of fat emoluments?"

"Well, I am ready," said the thin voice. "Let us enter. Doubtless he has money in the—"

"Chapper-band! Nay, I insult the rainy-season thieves of Malabar! Beast of a Burman! Am I come to this, that I must sit still and be ogled by a sneak-thief?"

"But you robbed the—"

"Shush! I did not! The red-faced drunkard kicked me out of the first-class carriage by behime-end—and self having first-class ticket, generous employer having paid and self not having opportunity to trade same in and pocket difference. Should I entrust injured pride of bruised posterior to legal procrastination? So it happened that aforesaid angry drunkard's pocketbook containing not too many bank-notes made exit simultaneously. Personally—price was too low in exchange for injury to self-esteem, omitting bruises."

"But this is a different sahib, and his servants have run away," argued he with the high-pitched squeak. "There is only one punkah-wallah, who will also run—"

"He will not! I have threatened him with possession by Burmese devils if he should fail to pull the cord until relieved."

"But why? Do we want witnesses?"

"The gora-log die in the heat without punkahs."

"But if he were dead—"

"Crow! Jackal! Dung-beetle! Grave-robber! Ghoul! Burman! When you die, may barbers bury you. Gampati, may you richly recompense me in the next life for the destiny of this one that has made of me a consort with this necromantic vermin! Oh, though unimaginative proof of Darwin's dream! Thou tapeworm! That inside there is a specimen of homo sapiens—a young, clean, strong provoker of happenings—let us hope, not too well nursed by wisdom—let us pray, not noticeably provident—a buffalo for energy—a sentimentalist undoubtedly, since he is white. And we—what are we but parasites? Could we thrive off corpse? Are we priests? No. Are we wakils? No. Embalmers? No. Agents of political extortionism adding to bereavement of widow and children severe death penalty in form of cash down? No. Decrepit hyena! Even lice leave carcasses! Living American goose from U.S.A. lays golden eggs if suitably encouraged. Kill same—flesh and feathers—bah!"

"Then what shall I do?" asked the squeak.

"Shall act as indicated."

"Speak plainly."

"Paragon of imbecility! Blind owner of empty belly! Witless ingrate! Lo and look! Could generous Ganesha have done better for us? Ignorant, opulent, inquisitive, rash, lonely, lost white man, possessed of energy, lies sick from circumstances he has probably forgotten. Servants of same, being terrified, run, having bribed one punkah-wallah to remain, lest death ensue and therewith complications such as police investigation. Said servants, intending to summon medical aid, argue, quarrel, accuse one another, change minds and scatter—is it not so? Did we not hear portion of said arguments? Well and good. Verb. sap. Excellent. We arrive on scene. We wait for symptoms of return to compos mentis. Hearing call for help, we enter. We are astonished. Withers being wrung by indignation at predicament of stranded personage, bowels of compassion obligate us to express benevolence. Not so? Universe as is, on fifty-fifty basis, barring accident, delivers quid pro quo—same, speaking personally, taking form of cash emolument. What was that? Is it time to be astonished!"

John Duncannon lifted his head from an air-pillow that burned like a hot brick and swallowing more water, shouted:

"Ho there! Who are you? Come in!"

The effort made him weak and he lay down again, shutting his eyes because the walls whirled sickeningly. A key creaked in a lock, the door opened gingerly and a blast of hot wind entered, bringing dust with it. When he opened his eyes again he was aware of an immensely fat Bengali standing near the bed, examining the clinical thermometer with an expression of contemptuous amusement.

He was an extremely handsome babu. His face looked brainy and good-natured. The cunning of his large brown eyes was tempered by good humour. His bare legs, remarkable in a land of spindle-shanks, looked stout enough to have carried twice his weight, prodigious though that was. He wore a bright pink turban, rather soiled, a well-cut black alpaca jacket and elastic-sided boots, which were the only incongruity in an otherwise reasonable compromise between Eastern and Western costume.

"Salaam, Kumar Bahadur!" he said pleasantly.

"I don't understand you," Duncannon answered, his voice crackling with the heat.

"Salaam meaning peace where is no peace, but wishing same," said the babu. "Am Washingtonian democratist since short experience in U.S.A. All U.S.A. Americans are kings as per constitution, consequently kings' sons, unless Darwinian theory should be adopted as national religion by amendment—in which case ancestors would have to be sold at auction. Meanwhile, Kumar Bahadur, meaning son of a king, your Honour, is form of suitable salutation—same as how d'ye do."

"Who are you?" demanded Duncannon.

"Sri Chullunder Ghose."

"Sri?"

"Same being significant of high degree in Universal University, self being failed B.A., Calcutta, consequently persona non grata to certified nabobs of knowledge. General public notwithstanding, knowing good thing when it sees it, conferred title of Sri by acclamation; governing committees of less universal universities giving consent thereto by silence, same being very dignified.

"Who is your friend?" Duncannon asked.

"Assistant," the babu corrected. "Stays outside, being Burmese person of no social standing. Sits in dust where he belongs."

"Why do you talk English to him?"

Chullunder Ghose scratched his protruding stomach, possibly to help himself recover from surprise.

"Being savage from wilds of Burma, said miserable creature knows no other intelligible language," he answered nervously. Then, with the bedside air of a physician, "What can I do for your Honour?"

His coppery-ivory skin appeared to glow with human kindness; there was cunning mixed with it undoubtedly, but nothing that looked treacherous.

"What do you think you can do?" Duncannon asked. "I don't know how I got here, where I am or how to get away."

"Sahib, show me any man who knows any of those things and I will show you a god!" the babu answered. "'Nevertheless,' says Santayana, 'waking life is a dream controlled.' We must endeavour to control same. Can assist."

He whistled and a lean hand passed a bag in through the door. Chullunder Ghose deposited the bag on the table and pretended to grope among its contents while thoughtfully examining Duncannon's clothing.

"What have you there?" Duncannon asked. The bag looked much too businesslike.

"Medicaments. Am charlatan. Have cure-all remedies for all ills flesh is heir to. First must diagnose. Pray let me see the tongue."

He seized Duncannon's wrist but the patient shut his mouth tight.

"Hmn! Venesection indicated. Am extremely expert venesectionist."

"Nothing doing!" Duncannon remarked between set teeth.

"No? When were you in prison?" asked the babu.

Duncannon sat up.

"What do you mean?" he demanded.

"Tongue very white!" said Chullunder Ghose. "Am psychoanalyst. Who drank the whisky?"

"Ants, by the look of it!"

"New law of nature—marvellous!" said the babu. "Person lifting self upstairs by seat of breeches mere amateur compared to ants reducing level of liquid by lying in same!"

He stooped and sniffed at John Duncannon's hair, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand to hide a broad smile, and turned toward the bag.

"Will prescribe," he remarked. "Am intuitionist."

He whistled again and added three or four words in an undertone. The same lean hand that had produced the bag passed in a big brass chatty containing water. Chullunder Ghose felt it with his flexible fat hands and proceeded at once to reduce the temperature by wrapping it in wetted cotton cloth and standing it on the table where the hot wind through the open door blew all around it.

Next he proceeded to cool the room, pulling out one of Duncannon's sheets from the hold-all, wetting it thoroughly and hanging it over the door. The effect was instantaneous. Duncannon sighed relief and laid his head back on the pillow. Then Chullunder Ghose poured water from the chatty into a tall brass cup, added powder to it and brought the sizzling contents to the bedside.

"This," he remarked, "will save you from the bhagl-kana."

"What's that?"

"Bug-house!"

John Duncannon drank the sizzling stuff and stared. Almost at once he felt immensely better. His head ceased to throb. He discovered he could sit up and see clearly without the room beginning to whirl.

"Dope?" he asked suspiciously.

"Squeeze miss! Close call—very. Bhagl-kana yawning! Memory any better?"

"Yes," Duncannon answered. Still vague mental pictures of the last three days were forming in his mind and, strangely enough, they travelled backward. He had recollection now of being carried on a stretcher in the darkness by a group of men who spoke only at long intervals, in a language of which he knew not one word. Then he remembered a temple—or was it a cave below a temple? All at once he recalled the person described as a Gnani, whom he had visited, contrary to the advice of Galloway, who was some sort of government official at Mount Abu.

The babu watched him, scratching a fat jowl, his huge head a little to one side.

"Where am I?" Duncannon asked suddenly.

"Dak-bungalow—Hanadra—territory of the Maharajah of Sirohe," said the babu.

Duncannon's face took on a new shade of perplexity. He remembered now that he had acted recently without respect for law or custom.

"Sit down," he said, gesturing toward a chair. The babu sat, drawing his legs up native fashion under him, pulling off the elastic-sided boots and letting them fall to the floor.

"How far am I from Mount Abu?" Duncannon demanded.

"As crow flies, ten—twelve—fourteen miles, said Chullunder Ghose. "Nevertheless, two sides of triangle are longer than third side according to laws of geometry, Euclid still prevailing over Einstein. To return to Mount Abu you must climb four thousand feet, and we will all cuss Newton who invented gravity and made us sweat much."

"I heard you say my servants have run away."

The babu nodded.

"Am hopeful person," he added blandly.

"What do you mean?"

"Am hoping your Honour heard nothing else."

"Did you notice a tiger-skin anywhere?" Duncannon asked.

"No, sahib."

"That's strange. I suppose my servants stole it. I have a hunting permit. I came down from Mount Abu to shoot a tiger; shot one, too—a beauty. I was cautioned by a gentleman named Galloway—a magistrate, I think he is—who issued the permit, not to go near any temples and particularly not to interfere with a certain Gnani. But I did visit a temple, and come to think of it, I guess I met the Gnani."

"Naturally!" said Chullunder Ghose, folding his hands over his stomach. He was enjoying himself.

"I must return to Mount Abu," Duncannon went on. "I'm expecting some mail at the post-office. Do you suppose I can manage without anybody knowing where I've been?"

"Am expert manager," Chullunder Ghose said, looking upward at the ceiling where a snake apparently was pursuing a rat across the ceiling-cloth. "Am exoteric pragmatist," he added, looking down again. "On esoteric plane am all benevolence. Wisdom being priceless, make no charge for same, but for necessary application of philosophy to fact this babu should have recompense."

He betrayed suppressed excitement by producing a handkerchief and catching it adroitly two or three times between the toes of his right foot. Otherwise he was as calm as a bronze Buddha.

"You mean you would like me to pay you for that medicine?" Duncannon asked. He knew very well that was not the babu's meaning, but as he began to feel better his natural shrewdness counselled him to begin to take the upper hand. But he was dealing with a man at least as shrewd as himself. The babu smiled and made a shoulder-gesture that was charitable, generous, sublime, indifferent to all temptation.

"Am altruistic charlatan. No charge. Not being M.D., medical etiquette does not oblige me to submit bill—in fact, might go to prison did I do same. It is time for second dose of restorative."

He got off the chair as actively as a man of half his weight, washed the brass cup and mixed a strong-smelling potion in it, measuring extremely small spoonfuls of powder from a dozen packages and mixing them with water.

"Learning in daily newspapers of ravages of bootleg liquor," he said, passing the cup to Duncannon, "this babu made journey to United States to offer thaumaturgical assistance on basis of fifty-fifty, but fell foul of medical trust, who caused police investigation. Sad to relate, was arrested. Offered to prove conclusively by demonstration before magistrate, chief of police and editors of daily papers that this secret compound is elixir vitae, neither more nor less. Bidding them produce two men in delirium tremens, two drug addicts in last stages of disillusion and two politicians for the purpose of experiment, was fined two hundred dollars, same being sum total remaining in wallet after paying lawyer, and was ordered deported as undesirable—packages of drugs all confiscated—democratic, very! Drink, sahib!"

Duncannon made a wry face as he swallowed the strong-smelling stuff; but almost at once he felt a comfortable glow and all his strength returning.

"What do you suppose has been the matter with me?" he asked.

"Ignorance!" said Chullunder Ghose. "Clear case of congenital ignorance. Osseous formations on western occiput inducing self-esteem so adamantine no advice can permeate. Plus curiosity. Plus pride aroused by shooting tiger. Plus fact that tiger was pet pussy-cat belonging to temple of great Gnani. Plus underlying eagerness aroused by business. Total—serious derangement of biliary organs. Symptoms—fever, headache and a smell of a peculiar incense in the hair. Are you married?"

"No."

"But engaged to be married?"

"No. Why?"

The babu sighed and looked relieved.

"Because I get along very nicely always until love affair casts cloud over horizon."

"Are you a bachelor yourself?"

"Sahib, weep for me. Have wife and seven children! Am martyr at stake of emancipation. My wife is new female—poetess, political economist, lecturess—uneconomical, very. Rigorous, though obsolescent prejudices have excluded me from caste affiliations, all because of her, thus slamming doors of richly paid professions in my face."

"Do you know India?"

"All of it, sahib!" In quest of stray emoluments for sake of wife and family, have wandered from Columbo to Lhasa and from Karachi to Calcutta serving many sahibs most discreetly. Wisdom being priceless, all remuneration is an insult. Pocket same for sake of wife and family. Insult me, sahib. Probe the depth of this babu's humility!"

"What can you do, for instance?"

The babu's face grew wreathed in an ingratiating, wise, suggestive smile.

"Can get secret information," he said, pursing up his lips.

"What makes you think I need secret information?"

Chullunder Ghose chuckled and scratched his stomach with the nails of both hands.

"U.S.A. United States sahibs don't call on holy men to sell them shaving soap!" he answered. "Nor do holy men put kibosh on foreign gentlemen to cause gap in memory, unless said gentlemen behaved with inquisitive and indiscreet assertiveness."

"Do you know the Gnani?" Duncannon asked.

The babu drooped his eyelids, either modestly or else to hide the fact that he was thinking.

"We do not speak of knowing him," he answered after thirty seconds. "Should you ask me, does the holy and benevolent one exert himself to know of my existence, I would answer."

"Well? Does he?"

"There is no knowing how much he knows," the babu answered slyly. "At certain times he exerts himself; at others not. Shall I diagnose? Shall I tell you, sahib, why you forced yourself into his presence?"

John Duncannon hesitated. He could not remember yet the circumstances of his visit to the Gnani, though very dimly somewhere in his brain, or else in his imagination, was a picture of a gaunt grey-bearded face with burning eyes that glared at him indignantly. He more than half-suspected that the wise course would be to try to forget the Gnani altogether, especially if it were true that he had shot the old gentleman's pet tiger. However—business first. He had a sense of loyalty to the firm that amounted almost to religion; and it had dawned on him that he would have to find some native intermediary if he hoped to forestall Lichtig, Low and Pennyweather, who were on the same trail as himself. This man might do, but he must first make sure of him.

"Tell you what," he said at last. "If you can tell without moving off that chair why I went to the Gnani, I'll hire you."

"Oil!" said the babu promptly. He threw the handkerchief again and caught it in his toes. "Am hired?" he asked. "How much emolument?"

"Expenses and a sum of—"

Duncannon paused.

Chullunder Ghose's face grew rigid; his expression was that of a gambler who has staked his last coin and awaits the outcome.

"—thirty thousand rupees—that's the equivalent of ten thousand dollars—if I get what I'm after."

Chullunder Ghose exploded an enormous gasp.

"Sahib," he said, "in the hope of that much money I would go in search of Golden Fleece, Holy Grail, Eldorado and Fountain of Youth! Am hired! Accept! Shall have to cheat you out of the expense account, having wife and seven children; but you will save money, nevertheless. Will write expenses in a little book. You audit same, for sake of appearances, and count the cash, which is the important thing. But the merciful man is merciful to his babu, so you will look the other way when this babu makes bargains—yes?"

"In reason," Duncannon warned him.

"Sahib, I will walk on tip-toe of discretion."

NORMAN ST. CLAIR GALLOWAY was much more than a magistrate. He was a bear-leader of rajahs on vacation at Mount Abu, which is a hill station in Rajputana. In the temporary absence of the local magistrate he had issued a hunting permit to John Duncannon, scrawling the words "acting pro. tem." underneath the official seal and his wholly illegible signature.

Indian maharajahs, rajahs, nabobs, nizams, chiefs and minor princes being nearly seven hundred in number, and no two alike, no two having quite the same measure of authority or nearly the same personal peculiarities, the overruling British Raj has had to invent ways and means of tempering their eccentricities—elastic means, adjustable to circumstance. Hence Norman Galloway, so used to stepping into other people's shoes and sawing horns off other men's dilemmas that a mere morning substituting for a magistrate was not worth comment at the club.

His own office was in his bungalow—in a big room opening on a veranda with a view of the lake and the enchanting Aravalli range of hills beyond it. Being a bachelor, the remainder of the house was given up to saddlery, polo-sticks, spears, guns, sporting prints and a very spacious sideboard—known as the high altar—containing alcoholic stimulants. There was a stable at the rear containing twenty ponies, each one of which had a sais of its own, and there were seldom less than fifty turbaned individuals of one sort or another, who had permission, or who received pay to do something, or nothing, around the premises.

The office was frequently empty. So was the bungalow. So were the grounds, of all except two or three gardeners, whose main task was to see that other people's servants did not steal too many of the potted plants to grace their masters' dinner-tables. There would be mornings when Norman Galloway would ride off an hour before sunrise, followed by a pack-train loaded up with tents and enough supplies for a small army; and he would return, as a rule after dark, when some particular emergency in some remotely distant native state had been snubbed, adroitly snipped or coaxed into re-submergence. Whereafter one more secret paper would be filed away in the already overcrowded pigeonholes and an incident of which no newspaper and not more than five or six officials had heard even a rumour would be closed.

Naturally, Norman Galloway's official title revealed next to nothing of his actual authority. A consultation of the Blue Book would reveal that he had passed in seven languages, had been an army major and had occupied more than a dozen appointive temporary posts. His present rank appeared to be Assistant to the Secretary of the Home Department; but that might mean anything—and did.

His office was as unilluminating as his title. There were maps on all four walls, a very big desk with next to nothing on it, a smaller desk for the Parsee clerk, who was usually arguing with messengers outside, a swivel-chair, two armchairs and a basket for waste paper, in which a cat slept when the terrier would let her. There was also a steel safe, usually open and apparently containing nothing except cigars.

It was a hot morning—for Mount Abu, that is. The heat from the plains was creeping upward on the south wind; the lake was shimmering with hardly a cloud reflected on its surface; the mountain range was hazy, with evasive outlines and a glimpse here and there of scintillating granite. Norman Galloway sat in riding-breeches, long boots, spurs and a Norfolk jacket in the swivel-chair straight in the draft from the open window.

He was clean-shaven, with heavy grey eyebrows, greyish hair and a sunburned, florid face. His cheeks, and the end of his nose, were crisscrossed with bluish veins resembling the silk filaments in a United States dollar bill, and there was a deep white scar, two inches long, on one side of his chin. But it was a friendly sort of face; the blue eyes, wise and humorous, looked tolerant.

He was more than middle height and would probably grow fat when pensioned, but for the present his frame was wire-hard, though he possessed the knack of resting easily, tilting backward in the chair with his head against the wall behind him.

Facing him uncomfortably in one of the armchairs sat the scion of an ancient race of Rajputana, Rundhia Kanishka Singh. He resembled a lizard, if a lizard can be imagined in long riding-boots with six-inch spurs, a suit of neutral-coloured silk and a blue turban with the end a yard long hanging over his shoulder. In a petulant, querulously spoiled way he was handsome. Since he was only twenty-two or so, the inroads of hereditary vice had not had time to make his face look puffy. His almost amber-coloured eyes were dull with sulkiness, not with drugs. He had the beautiful old-ivory complexion of an inbred race, and his little black mustache was waxed into points that made him look aristocratic and distinguished, offsetting the lazy carriage of his shoulders. He was tall for his weight, which was probably hardly a hundred and twenty pounds, and he had very small hands and feet; his wrists, as strong as steel, were almost small enough to go through an ordinary napkin-ring. He wore no jewellery.

"I will marry a white woman. Then you will see!" he said angrily. He expressed his indignation rather by suppressing it than by any noticeable emphasis.

Norman Galloway put his hands behind his head and blew cigar smoke at the ceiling.

"My good fellow," he said, smiling, "how much experience have you had yet of bucking against the central government? You know, however much I personally admire an independent spirit, I obey orders."

The younger man's face grew vaguely darker. The eyes narrowed just a trifle. Galloway, rolling the cigar between his fingers, noticed.

"And if I should die today," he went on pointedly, "there would come another in my place who might be less sympathetic."

"My father will die very soon now and I shall be in his place," said the princeling. "He has been what you call a wise ruler. That means he has taken orders from you. He has stayed home. He has subscribed to famine funds. He has bought as much of the government loans as he could possibly afford. He has lent you troops to act as baggage-guards in your European war. He has swallowed all sorts of indignities. I am going to be different."

"My dear boy," Galloway blew cigar smoke again at the ceiling and his voice was patient to the verge of condescension, "your father began, let me tell you, by doing his best to be what you call different. It isn't mentioned nowadays and I don't want to dig up a forgotten issue, but the reason why he was not encouraged to grow personally rich was just that very 'difference' that you propose for yourself. He was likely to use sudden wealth unwisely—"

"By which you mean, without first asking your permission!" said Rundhia Singh.

"Why yes, I daresay I meant that, if you prefer to put it that way. You see, ruling princes are in the peculiar position that, while nominally independent, they must actually look to us to keep them on the throne. That makes us, so to speak, the guarantors. We're like the endorsers of a note. We're liable. So you see, it's only fair that we should specify the terms on which that guarantee shall hold good. The risk is entirely sufficient without adding to it by giving young princes permission to do anything they please.

"You spoke of marrying a woman not of your own race. Two or three rajahs have tried that. There are always women of a certain character, or lack of it, who can be found to undertake the obvious risk of—er—racial incompatibility. Most of them do it for money. You haven't money—none to speak of—none that would attract a latter-day adventuress. I see your point, of course. You think that, though we can control your financial transactions, we could not control your wife's if you should put your money in her name.

"Well, that may be; I express no opinion for the moment as to that. But I can tell you this, that there is at least one rajah who married a woman of my race and settled an enormous fortune on her—a vastly greater fortune than anything you can control or hope to acquire. The wife lives in the south of France and spends the money; and the rajah, I assure you, has nothing whatever to spend. He keeps up what appearances he can in a palace long ago grown shabby, and grows old regretting that impulse to be 'different.' I would be sorry to see you make the same mistake."

Rundhia Singh uncrossed his knees and rapped at one of his long boots with a rhino riding-whip. He stared at the toe of the boot, his lips moving as if he were choosing and rejecting phrases.

"You were rich," he remarked suddenly.

"Yes," said Galloway, "I lost the greater part of a considerable fortune through the failure of a bank. What of it?"

"You could be rich again if you would be my real friend instead of talking like an idiotic English schoolmaster!"

Galloway laughed. Rundhia Singh stood up and with a gesture like a woman's, shook the end of the turban over his shoulder.

"Well, I will go to the club," he said, and hesitated, then added with a thin smile: "You are throwing away a fortune."

Galloway threw the end of his cigar into an empty flower-pot near the window and held out his hand.

"So long then. Look in again whenever you feel inclined for a chat. I wish you'd ride one of my ponies—he needs skilful schooling. Will you? Good—I'll send him to the club this afternoon.

Galloway stood motionless until he heard the prince's pony go cantering up the drive; then he bit the end off another cigar and shouted—

"Framji!"

Entered a benevolent appearing, handsome, middle-aged man in a black alpaca frock coat, wearing the Parsee headdress that is like a polished cow's hoof upside down. His features were as refined as those to be seen in Persian miniatures. His manner was that of an up-to-date mortician, bland, alert, exceedingly considerate, tactful and unobtrusive. He kept his hands folded in front of him and waited to discover whether or not the situation justified a smile.

"Who's available, Framji, for serious work?"

"Sivaji."

"Good. Send Sivaji to Tonkaipur, and let him stay there until he finds out what young Rundhia Singh is holding up his sleeve. Incidentally, let him find out, if he can, whether the rajah is dying a natural death or whether it's poison. Young Rundhia Singh is growing much too cocky about coming to the throne, and he just now hinted he would like to bribe me. That means he expects to make a bag of money. Sivaji must ferret out the facts."

"Yes, sir."

The Parsee's classically perfect features eased into a smile of confidential understanding.

"Sivaji will need money," he remarked.

"Usual pay and expenses," Galloway answered. "Not an anna more. Give him fourteen days' advance and send him packing. Tell him if he succeeds there'll be a present out of the private fund; if not, it's his last important assignment. He's to report direct to me in writing as often as necessary, and he's not to use the ordinary mail. Registered won't do either. He must send his reports by runner and we'll pay the messenger at this end. That's all."

Framji vanished with the unobtrusive tread of a distinguished personage's butler. Galloway sat down at the desk, drew out a bulging envelope and proceeded to study the contents, turning sheet after sheet of closely written manuscript face downward as read. He was presently disturbed by an assistant Hindu clerk, who murmured something to him in a voice like a strangled parrot's.

"Show him in!" he snapped, and went on reading.

There came a heavy, yet active tread, beneath which the office floor creaked; then heavy regular breathing. Some one stood before the desk, but Galloway took no notice until he had finished the papers and returned them to the desk drawer, which he locked.

"So it's you?" he said then, staring.

"Have walked up from Hanadra," said Chullunder Ghose. "Have also answered likewise thirty thousand questions, tongue cleaving to roof of mouth in consequence."

"Boy!" Galloway struck a bell on the desk. "Sit down—that big chair will bear up under you." Then to the white-robed servant who appeared in answer to the bell: "Give Chullunder Ghose a mango-bass with ice in it."

"Am not so rigorously bound by caste as all that," said Chullunder Ghose, his fat face widening in a grin.

"Oh, all right. Bring the brandy at the same time."

Nothing further was said until the tinkling tall glass appeared on its silver tray and brandy had been poured into the mango-juice and imported soda-water.

"In the hope that I may dance at your Honour's wedding!" Chullunder Ghose remarked then, drinking deep.

"You fat rascal, what have you been doing now?" asked Galloway. "If you're in trouble, mind you, I told you last time it would be useless to come to me again."

"Adamantine drasticism! Sahib, it is easier to rid oneself of fatness than of rascally proclivities. Am orthodox immoralist. Difference between me and other people is, that they act legally for immoral reasons, whereas this babu acts illegally for moral ones. Am just now duck in clover."

"Duck? In clover?"

"Quack-quack! Certainly. Am wandering physician—mystifex—uncertified M.D. with troupe of performing Burmese charlatans. Can pull teeth, cure colic, cast a horoscope—permit me, sahib—can cast good one now this instant. Saturn being in conjunction with moon in constellation Scorpio, on Friday thirteenth, much intrigue is indicated. Verb. sap."

"Spill the beans, confound you!"

"Beans too precious, sahib. Show me basket first. Maybe there are holes in it."

Galloway stroked his chin, one elbow on the desk.

"All right," he said after a moment, "you may speak in confidence."

"Prerogative of deity! Who other than an immortal God—or an Englishman—would dare to say that, knowing he will not be mocked! Who other than a babu would believe him? Well—on this occasion there is bacon with the beans."

"Come on now, don't waste time. Explain yourself."

"Am impresario."

"Perhaps you'd like another drink before you go," said Galloway suggestively.

"Before I go, yes, but not yet! You wait and see!" the babu answered, visibly enjoying Galloway's impatience. He proceeded to mop sweat from his face with an enormous handkerchief for the purpose of keeping the official waiting.

"John Duncannon!" he said then, wiping the back of his neck, but watching Galloway, his eyes not missing the vague trace of irritation that the other let escape him.

"Well? What of him?"

"Yankee—American—U.S.A. Turner, Sons and Company, of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—tr-r-r-illionaires!"

"Damn!" remarked Galloway under his breath. Then aloud, "I might have known you'd not miss that bet!"

"Sahib, that is sweetest compliment, excepting one—have just received a month's expenses on account! Am now fiduciary—one might say in partnership with Turner, Sons and Company of Pittsburgh—P-A—Pay—no pun intended!"

Galloway lighted a cigar and let it go out again, crossed his legs, uncrossed them and sat staring at Chullunder Ghose.

"I could lock you up, of course," he remarked at the end of about two minutes.

"Nay-y-y! You bought pig in poke! You agreed this is matter of confidence!"

"Well—all right. Why is Mr. Duncannon here? I issued him a hunting permit and particularly cautioned him to keep away from temples. Information comes that he has been into a temple. What had you to do with that?"

"Nothing. This babu missed that bet! Was traipsing with personally conducted circus of world-famed Burmese magicians, through Sirohe country where peasants prefer toothache, the bellyache and barren wives to parting with a small emolument. Arrived at Hana-dra destitute of all but honour and five baskets containing performing snakes. Mutinous Burmese adherents were contemplating murder—of me! I had no money for their wages. Found U.S.A. tr-r-r-illionaire decidedly hokee-mut in government dak. Hired self to same for fabulous remuneration—plus expenses."

"What do you mean by fabulous remuneration?"

"Over the hills and far away—payable on receipt of goods!" Chullunder Ghose explained. "Must help self from expense account."

"What's his object?"

"Oil!" said the babu; and his smile was oilier than the word. His fat face beamed amusement. Galloway looked serious.

"I'm told he forced his way into a temple after he had shot the Gnani's tiger."

"So am told. In fact, our Uncle Sam admits it. Nevertheless, the Gnani made short work of him. Tee-hee! Sahib, his hair smelt like Parsee tower of silence! The holy Gnani doubtless gave him soma, causing sleep, obliterating memory. Croesus Americanus probably thought it was milk! From personal olfactory investigation this babu imagines that his Reverence's servants, doubtless in absence of orders to contrary, defiled intruder's sleeping head with asafetida on way to dak bungalow, where they seem to have carried him in stretcher, there leaving him to die or otherwise, this babu engineering otherwise."

"Well, I'm due at the club," remarked Galloway. "Where is your American?"

"At Kaisar-i-Hind Hotel."

"I'll have a talk with him."

"Same might have advantages—likewise disadditto," said Chullunder Ghose, finishing his drink and setting the glass prominently on the desk.

Galloway rang the bell and ordered more drink. When the servant had gone Chullunder Ghose drew his legs up under him and holding the refilled tumbler in his right hand, looked very straight at Galloway across the rim of it.

"Somebody knows something," he said, then poured the contents of the tumbler down his throat. "As thus," he went on, gasping as he set the tumbler down, "somebody went to United States with story of much oil in Rajputana."

"Who?" demanded Galloway.

"Not me!" the babu answered. "Must have been immoralist, selling same misinformation to rival concerns. Lichtig, Low and Pennyweather of New York—also tr-r-rillionaires—have clapped hot noses on same cold scent! Curtis Pennyweather, no less, of Lichtig, Low and Pennyweather, is already in Mount Abu."

"I know it. He lunches with me at the club," said Galloway and leaned back staring at the ceiling. "Well, what do you suggest?" he asked, throwing away the spoiled cigar and biting the end off another one.

"Am thinking, now fat is in fire, better cook something," Chullunder Ghose remarked, also staring at the ceiling. "U.S.A. Americans are very used to circumventing obstructiveness, being trained by prohibition. Shut lid here—peep out through crack there. Pad-lock? Remove hinges! Impose cash penalties? Form company to capitalize deficit thus created and sell stock in same at premium! Clap in prison? Convert prison into comfortable club, from behind convenient walls of which they control presidential election. Hang? Electrocute? Return as spooks at seances and manipulate affairs of nation by frightening old ladies of both sexes, who have vote! Only one way to put ultimate kibosh on hundred-per-cent U.S.A. Americans—same as dynamite—touch her off!—give her her head!—let her go, Gallagher!—step on her!—attaboy!—boof!—stand back!—and tidy up mess afterward! Positively something will happen. Better watch."

Norman Galloway nodded.

"You propose then to bear-lead this Mr. Duncannon all over Rajputana?"

"Sahib, like modern commander-in-chief, this babu will direct campaign from rear, being thus in good strategic situation for about-face."

"I may as well tell you now as later," said Galloway firmly, "that there will be no prospector's permits issued."

Chullunder Ghose folded his hands on his stomach and appeared well pleased with the announcement.

"Main point is, sahib, this babu having established official confidence by coming straight with information to proper authority, expects—"

"No use!" said Galloway. "There's no fund from which to pay you a retainer."

If possible Chullunder Ghose looked even more pleased.

"—expects concessions."

"Such as—?"

"Look-the-other-way-iveness! There might be now and then irregularities not easily explainable at once. This babu is habitually most discreet."

"You'd better be! If you get into serious trouble you must take the consequences. Mind you, I shall watch you, so you'd better bear that in mind and report to me at intervals. Now I must hurry or I'll be late for lunch."

THE club at Mount Abu overlooks the polo-ground, which is a rather undersized field blasted from the rock and spread with mud; being fast in consequence, it lends itself to the extremely skilful technique of the Indian-born player, and at almost any hour of the day the benches are ablaze with colour where the world's most critical exponents of the game sit watching their friends at practice. Many of the princes of Rajputana spend the summer season at Mount Abu and they all have retinues of impecunious relatives. The club veranda is usually a splurge of sunshades, straw hats, topees, drab riding-coats and here and there the rose or yellow splendor of the headdress of a maharajah.

Which is why the visitor to India invariably jumps to the conclusion that no British-Indian officials ever do any work, not realizing that overworked men and their wives must come away from the hot plains now and then for a vacation.

So it was nothing new to Galloway when Pennyweather greeted him on the club veranda with rather tolerant superiority. The rigor of his nerve-devouring creed had lined and tightened Pennyweather's face and ruined his digestion until he looked like a yellowish old man instead of fifty-five or so. But his dark eyes shone with intelligence; he was very well dressed in a dark-grey suit, had a pleasant voice and his smile looked genuine as he shook hands with the slow withdrawing movement of a man who liked to study every one he met. But he seemed to have nothing to say and made haste to introduce his daughter.

"Dad's so grateful, or, at any rate, he ought to be!" she said. "He can't eat hotel food. He has had nothing but bottled jujubes since we left the ship."

"Beef and pepsin lozenges," corrected Pennyweather.

Galloway grinned genially.

"Soup, canned lobster, curried goat—with a cocktail first and coffee afterward," he announced and Pennyweather winced.

Galloway looked at the girl with the bachelor's eyes, that are so much more critical and superficially more discerning than a married man's. He thought her overdone. There seemed a little too much art in her deliberate simplicity, a little too much confidence about her lack of shyness, too much restraint in not wearing more expensive clothes and too much care not to appear over-cultured.

But there is no pleasing some people.

"First trip East?" he asked her.

He expected her to make some cliché comment on the mystery of India or on the disillusioning lack of it. He was ready with appropriate banalities to counter with. But she surprised him.

"No. I have stayed twice with an aunt in Ahmednaggar. She runs a hospital for women—great fun."

"Missionary!" thought Galloway. "Good God!"

Aloud, he said—

"You don't look old enough to enjoy that sort of thing!"

"I can even enjoy curry—and Dad's punishment!" she answered. "He is paying for having broken rules for forty years. He ate fried eggs and pie at quick lunch counters, when he could easily afford to be sensible."

"Aren't you hard-hearted?" asked Galloway.

"Dreadfully. I hate bunk. You can't hate properly and compromise."

Galloway decided he disliked her, although her looks were in her favour. She was rather small, with quantities of bronze hair, dark-grey eyes and an agreeable voice that he thought was too well cultivated. He supposed that if he talked chiefly to the father he would be just about able to endure her company through lunch.

But the father appeared cautious about making conversation, ignoring the food served to him, refusing drink and feeding himself on tablets from a bottle in his waistcoat pocket. He encouraged his daughter to do the talking.

"Deb's amusing," he said. "Make her work. I'm only a dry old money-maker. Besides, I'm not feeling well.

"With a name like Deborah—Deborah Pennyweather—think of it!—I couldn't take life lying down, now could I?" she asked, looking straight at Galloway. "It made me fighting mad to have to live with such a tag tied to me."

"You'll be changing it before long," Galloway suggested. "What do you expect to do in India?"

"Provide Dad with healthy excitement. He has done nothing for nearly forty years but go to the office six days a week and read market reports all day Sunday. Since Mother died home doesn't mean a thing to him. He doesn't even know how many gardeners we keep. The only visitors he sees are doctors. Bunk, bunk, bunk! I'm educating him—making him study something else than the clock on the library mantelpiece and the ticker at the office. Am I, or am I not, a holy terror when I once get started, Dad?"

"She was born at full speed and won't run down," said Pennyweather mildly. "She's been expelled from two schools."

"They tried to teach me bunk!" said Deborah. "You can't lead any one except a zany by the nose unless you explain why and where and what it's all about. Dad isn't a zany. And if you prod him hard enough he kicks. I had to think up something sensible for him to do and invent a cast-iron reason for it. I knew it wasn't any use telling him to take up literature or golf or go fishing. And nobody worth thinking of would marry him; he has too much money and too little imagination what to do with it. I had to invent a business reason or he'd never have understood. And it had to hold water or he wouldn't play."

"You call this play?" asked Pennyweather, glancing at the curry in the dish.

"Never mind, Daddy, you'll eat crow before I've done with you!" said Deborah. "I met a swami. Know what they are?"

"Rather! There are several varieties," said Galloway.

"Well, this one was the other kind. He had no use for a dollar bill. He wanted billions. He was full of Sanskrit phrases done into journalese, but he knew how to talk turkey, and just now he's in prison, due to talking turkey raw. He didn't know I'd been to India, but he did know Dad has money, so he cut short the beatitudes and made a proposition. He asked for twenty-five-seventy-five, and I beat him down to ten-ninety before I even showed the thing to Dad, and not a cent down, mind you. Dad knocked off an extra five, allowing him five per cent of the gross; and if we pull it off he'll be on easy street when they let him out of Sing Sing."

"What was his name?" asked Galloway.

"Swami Ullagaddi Hiralal."

Galloway's face reddened visibly. He set his knife and fork down, staring, ready to explode.

"I'll bite. What is it?" asked Deborah.

"A lean man with an ascetic looking face—hole in the lobe of one ear—one front tooth missing from the upper jaw?"

She nodded.

"He was in jail at Baroda for stealing," said Galloway. "When he came out of jail Professor Abercrombie of the Glasgow Archeological Foundation took him on as interpreter for a tour through Rajputana examining ruins. A tiger killed Abercrombie and only bits of his body were found. I myself shot the tiger a week afterward. Most of the servants ran away and Ullagaddi Hiralal along with them. 'Ullagaddi' means 'little onion,' but he left no scent that any one could follow, and I always supposed it was he who took Abercrombie's papers."

"It certainly was," said Deborah. "There was a map and a full report of an enormous oil-deposit, all in Abercrombie's handwriting.

"Those fellows can forge anything," said Galloway. "I've seen—"

"Put up your money! Do you think I'd take that swami's word for anything? Or that Dad would leave the ticker without checking up? We—I went to the publisher of Abercrombie's book on 'Traces of Hittite Occupations near the Dead Sea,' and they let me look at the manuscript. I swiped a page to show to Dad and he called in an expert. We had it photographed and made slides and projected a word from the manuscript on top of a word from the map, and then another word from the report. They fitted. Then Dad looked up Abercrombie's rep, bought copies of all his books, decided he was the sort of man who would say 'if today is Monday, as seems to be approximately accurate within several places of decimals, and allowing for the changes in the calendar made by Julius Caesar on the advice of Sosistrates, then the inference is that tomorrow almost certainly will be Tuesday!'"

"Yes, he talked and wrote like that," said Galloway.

"Well, his report on the oil was in words of two syllables. He had seen, smelt, tasted, analyzed and measured up. Besides that, Dad found out that Abercrombie was the man who found oil somewhere up in Assam and never made a cent out of it—simply gave the secret away."

"Yes, he did that. Yes," said Galloway. "Go on. Where's the report and the map? I'd like to see 'em."

"So would I!" said Deborah. "I'm in Dutch—dragged Dad all this way and let him lose the papers! Can you beat it? Had them all right when we left the ship. Dad would have taken the next ship back, only it was he who lost them; and I'll say this much for him: he plays fair. They were in his trunk at the hotel. We went out to see the Elephanta Caves and when we came back they were gone. Lock picked. Nothing else missing."

"Whom had you talked to?" asked Galloway.

"Nobody. The only one who could have spilt the beans is Swami Ullagaddi Hiralal. They let 'em write letters from prison, you know. He might have written to a friend in Bombay. Maybe he talked things over in Sing Sing with some of our more experienced get-rich-quicksters. They'd be sore with him for only sticking out for five per cent; they're mostly in, you know, for promising five per cent a week to ministers and honest farmers; and they're all of them worse suckers than the people who buy their blue-sky bond issues, or they wouldn't be in Sing Sing. Ullagaddi Hiralal may have formed a syndicate. He only got a year and a day, I think it was. If he's caged up with some of our choicest native sons they may have coaxed him to write to an accomplice over here to steal the working plans."

"Well? What do you propose to do?" asked Galloway.

"See life!" she answered. "Dad can quote you market fluctuations since the year before the panic. I learned Tennyson's 'Princess' by heart. We've both got memories. We've pored over the report and stared at the map until it's not exactly easy to forget. It was like Treasure Island. Dad felt almost young. We're off after buried treasure!"

"There are formalities," said Galloway.

"Red tape? Oh, shucks! Let's talk horse! Colonel Falmouth, who came to New York with the polo team, told us you are the inside works of the Indian Government, and that anything you O.K. gets rubber-stamped. No use your denying it; we had the low-down on you before ever we left home."

"I'm simply the assistant to the Secretary for—"

"Bunk, bunk, bunk!" said Deborah. "I despise it! Why not say you won't, the way Dad did when I started in on him?"

"You'll have to pardon me, but what I meant was this—" said Galloway—"suppose I let you wander anywhere you please, and you get hurt? You know, this isn't the United States."

"You bet! They murder 'em one a minute in Chicago. This show's tame. How many murders have you had in Rajputana since the year of Queen Victoria's Jubilee? How many young girls disappeared?"

"Tigers, you know," said Galloway.

"I'll bet you fifty dollars to a tooth-pick," Deborah retorted, "that the autos kill more people on our main streets in one week than the tigers of the whole of India kill in a year! We'll be careful and not jay-walk when we see a tiger coming!"

"Snakes."

"Throw in your snakes. I'll bet the U.S.A. can beat your sudden death roll! Add Amritsar and I'll throw in Herrin! You'll have to think up a better excuse than the speed of the tiger-traffic!"

Galloway grinned. He liked it. He began to change his mind about her.

"Well, we mentioned red tape," he remarked. "There's lots of it. I might be able to get permission for you to go wandering through Rajputana. Mind you, I say 'might.' But suppose you should find oil, what then? Do you think you would own it? Let me tell you, every inch of land in Rajputana has been owned for generations; either it belongs to individuals, who cling to it like leeches from one generation to the next, or it belongs to temples and religious institutions that can't sell if they would; or it belongs in entail to one of the ruling princes, who lease it to life-tenants, who would never let you stick a shovel into it on any terms at all."

"Bunk!" Deborah retorted. "I've seen the statistics. There are gold-mines, coal-mines, salt-mines, diamond-mines, oil in Assam—you English want to keep it to yourselves. I know you! Listen: do you suppose Dad and I took the trouble to find out who is the one man in India who can pull plugs, without intending to—"

She hesitated. Her eyes had caught those of an Indian prince who was seated at a near-by table toying with a glass of sherry and bitters.

"Who's that sheikh in lizard-coloured silk?" she asked.

"Prince Rundhia Kanishka Singh. But please don't talk so loud. You were just going to offer to bribe me, weren't you? Please don't. It gets monotonous. You'd be the second this morning and—"

"Shucks!" exclaimed Deborah. "If I could buy you I'd have known it long ago and you'd be bought already. But they don't stay bought when they can be had that easy. Do they, Dad? But we know what you're up against. You want to irrigate about a third of Rajputana and you can't borrow the money in Europe? Am I right? Well, here's Dad with an automatic calculator in his head, bored stiff; he's so itching to talk business that he can't sleep. Explain your irrigation project to him, put one over on him if you can, and get your money for the water. Turn me loose to look for oil, with a water-tight concession guaranteed if I can find it."

"You don't understand," said Galloway. "I have nothing to do with irrigation projects. That's a different department."

Deborah stared at him open-eyed.

"Do you mean to tell me," she said, "that you don't realise what's being fed to you out of a spoon? Dad had to fire a secretary for taking thousand-dollar bribes just to bring bond offerings to his notice! Your Indian Government could no more get to him in New York than Debs could get the Presidency! Here he sits—wide open! All you've got to do is steer your scheme to him. He'll snap it, if it's good.

Prince Rundhia Kanishka Singh interrupted, strolling over from the other table to force introduction.

"Did you send that pony?" he asked in his pleasant voice. "I'll practise him before the game this afternoon."

He knew quite well that the pony had not yet come, but in the circumstances Galloway could hardly snub him for intruding. He had to be introduced, and Pennyweather felt the first vague thrill he had experienced in India; he was actually interested.

"One of the neighbouring kings?" he asked, standing and shaking hands with that peculiarly slow withdrawing movement.

"Not yet," the prince answered, "but they tell me you are a real one—one of the American money kings! Our little principalities will look to you like comic opera. Come and see one at close quarters. We will try to make it entertaining." Then, with a sly sidewise glance at Galloway: "You will see for yourself what might be done if it weren't for the restrictions. Come to Tonkaipur. We have some very interesting ruins in a desert that once blossomed like the rose but nowadays needs irrigation."

"There comes my pony," said Galloway pointedly, frowning through the window, and Rundhia Singh accepted the hint, but with a thin smile on his handsome face.

"Interesting, very!" remarked Pennyweather, glancing at his daughter when the prince had gone sauntering out of earshot.

"One of our least interesting and least reputable sons of reigning rajahs," said Galloway. "He'll be a nuisance if you let him."

"Oh, I met lots of them at Abednugar," Deborah retorted. "Usually when they're called disreputable it only means they're kickers. Believe me, they're the only ones that have any pep. You don't want 'em to have pep, for fear they'll kick over the traces. What are we going to do now? Watch the polo game?"

AT the rear of the club, out of sight of the polo ground, there was a marquee, under which maharajah's ponies were installed, protected from the flies and too much heat. Behind the marquee was a row of tents for saises, who, being much less valuable than ponies and much easier to replace, had to put up with very inferior accommodation. Behind the saises' tents were booths of dry boughs roughly thatched with grass, under whose shelter tradesmen dispensed sticky sweet-meats and amazing stuff to drink, told fortunes, sold forged testimonials of character, lent small sums of money at enormous interest and swapped the gossip of all Rajputana.

Those booths were not commonly there; the usual regulations had been suspended on account of a septennial pilgrimage by Jains, Shrawaks and Banians to a cavern on top of Mount Abu, in which is a block of granite impressed with the footprints of Data-Bhrigu, an incarnation of Vishnu. The pilgrims had hardly yet begun to gather from the faraway villages, but trade does not follow religion; it makes straight the path ahead of it, and the parasites of piety were ready in advance of time.

Behind the booths, in the sun, because no maharajah owned them, there were animals in all the stages of decrepitude. Having four legs, they were described by courtesy as horses, to distinguish them from the sheep and goats, which were also caricatures of the animals whose names they bore. They were all for sale, as were the up-ended two-wheeled carts which the miserable brutes had dragged up the fourteen miles of zigzag high road from the baking plains.

Beyond those, under a gnarled tree that had a bald hawk perched on its topmost dead branch, was a small tent in which a Burmese gentleman sold charms to the relations of unfortunates who had been taken to the European hospital. He boasted that the charms were so terrifically potent that, if enough of them were smuggled to the patient's bedside, the concerted efforts of the most experienced English doctors would fail of their purpose and the patient would get well. He did a steady business and was regarded as a public benefactor.

Behind his tent, protected by the shadow of the tree from much too much sunshine, and by the tent from the view of the one patroling Rajput "constabeel," Chullunder Ghose sat, comfortably chewing pan and keeping one eye on his troupe of performing Burmese wizards, who were permitting themselves to be bitten by cobras for the edification of a dozen children, three tired women and some city-born sahibs' servants—who would presently pay for the entertainment.

Squatted facing the babu was a gentleman from Bikanir, whose virtues were not illustrated on his face. He had narrow eyes, a retreating chin, a long nose with a wart near the end of it, high cheek-bones and skin of a sort of neutral tint midway between raw liver and wood-ash. His beauty was under discussion.

"Anup, your horses might be sold to a green sahib," said Chullunder Ghose. "Not all sahibs know a bad horse. But you yourself could not sell them, because if you had been born out of a mangy camel you could not look more like a buth than you do."

"That is my misfortune, O Mountain of Fatness," said Anup, "but if you had not inherited dishonesty from your female relatives, you would admit that my desert-bred charges are fit for a king's wedding."

"Yes, to be fed to the jackals, since a king with any reputation to uphold invites all creatures to make merry with him when he marries," said Chullunder Ghose. "The point is, Anup, that if the sahib who is honored by my discriminating service should see your ugly face, he would not buy your horses but would call for the police. Moreover, he would mistrust me for having regarded you with such favour as to have let you approach within three miles of him. Mine is a Melikin sahib, who uses gunpowder for snuff."

"Then he will like my horse," said Anup, "since the devils are in league with devils. That yellow one—nay, golden, one!—that your Honour says looks as if a mule begat him from a tiger is of just such a heart of your 'Melikin sahib. No such devil of a biting, kicking savage can be found this side of Bikanir. Hardly a rope will hold him, and when he gets loose he is so fleet of foot and so cunning that it takes a week to catch him. He has killed three men. He kicked the head of Kalyan's buffalo to pieces. True, he is nothing to look at, but let your sahib only ride him and—"

"He is not worth five rupees," remarked Chullunder Ghose.

The bargaining went on interminably and the yellow horse, looking meek enough to take a money-lender on his rounds, was led to and fro at the end of a halter by a child whose uniform consisted of a shoe-string. It was hours before Chullunder Ghose let even a hint escape him of the real purpose of his visit to that disreputable pilgrim's market-place.

"My sahib will need many horses," he remarked at last.

"Let him buy one to begin with!"

"He will buy many, from the dealer whom I indicate, he being wise in this, that he entrusts his purchases to me."

"Then buy my golden beauty, Shah Jehan!"

"He would even buy that yellow jackal-meat if I should say it. But there is no haste. A clever dealer would have time to scour the countryside and find the best to bring to him. Do brains hide anywhere behind that face of yours, O son of ugliness!"

"Lump of melting butter, it is not beauty that makes brains, or you would have bought my golden Shah Jehan for your 'Melikin sahib."

"You boast like the hot wind, but are you really clever?" asked Chullunder Ghose. "If I thought you were clever I might trust you with a little mission. Having thus proved you are clever, I might buy many horses from you and give you another little task, that might prove profitable."

"Mountain of ooze, there is none in Rajasthan as smart as I am! Do I not travel from village to village? Am I not known from Kashmir to Baroda? Do men not tell their secrets to me, knowing I know other secrets and can fit one to another as the key fits in the lock, thus straightening out difficulties at a profit to myself without ever telling one man's secret to another?"

"But you have never heard of Ullagaddi Hiralal," Chullunder Ghose said down-rightly, as if that ended the discussion.

"Never heard of him? Hah! I sold a horse to Abercrombie sahib, and that son of immorality Ullagaddi Hiralal was interpreter, pocketing twenty-five percent—may buths disturb his peace! A tiger slew Abercrombie sahib. Before the news had time to spread, Ullagaddi Hiralal resold the horse to me at half-price, pocketing it all, nor could I make him take an anna less. Has he cheated your Honour?"

"He has," said Chullunder Ghose.

"Then with a good will will I search for him and—what shall I do? Shall the kites feed?"

Chullunder Ghose scratched his stomach meditatively.

"This time Garudi must wait."

He referred to the god of the birds, to whom a corpse left where the birds can reach it is a sacrifice, according to some pious theologists.

"What then?" asked Anup, puzzled.

"He has crossed the Kali Pani," said Chullunder Ghose. "He told the 'Melikins he is a swami. They will believe anything. Therefore they locked him into the strongest prison where they keep the thugs and chappar-bands, telling him to make a miracle and get out if he could. So there he stays and they feed him cow-meat and the flesh of swine; and from thence he writes letters."

"Hari bol! Preserve us from his letters!" exclaimed Anup. "That which is spoken is already bad enough. That which is written—who shall guess the meaning of it or foretell the end?"

"He has a friend," remarked Chullunder Ghose.

"Not he! As a jackal among jackals was he. No man trusted him. They say his mother died of bamboo-fibre in her food, and that he never paid the barber who performed her last rites."

"He has a friend," Chullunder Ghose repeated. "If your ear is one tenth as awake as your beauty is asleep you will discover that a friend of his has been to Bombay recently. You will find that he is a man of good enough appearance, so that he could gain admission to a good hotel on some excuse or other. He can read the language of the gora-log and he can pick locks craftily. There can not be more than one man who could be reckoned a friend of Ullagaddi Hiralal, who would fit that description. If he has returned from Bombay you can find him as you search the countryside for horses. But you will not say for whom you wish the horses. If you are wise, and if you wish to sell many horses at a profitable price, you will make haste."

"Does your Honour wish proof of his death?" asked Anup.

"I desire a proof that you have found him."

"Then shall I bring him? It might be managed. Should he resist he might be gagged and bound and brought by night."

"Siva namashkar! Why should I waste eyesight on a friend of Ullagaddi Hiralal? I desire a proof that you have found him, and there is but one proof that will satisfy me."

"Name it, sahib."

"A man's garment might be another's, and his shoes might be another's, and a turban might be bought in the bazaar. Moreover, witnesses are liars, and a horse-thief such as thou art, is a liar beyond possibility of detection until Yama checks up the account. But the things that are written do not lie, at least in some respects."

"Hari bol!" said Anup piously.

"So you will bring me all the letters that you find in possession of this friend of Ullagaddi Hiralal. You understand me? All of them, retaining none!"

"Gampati! What if he has none?"

"Then I shall know you have not found him, and I will buy no horses; but I will recall to mind a little matter of a horse-theft that I used to know about and I will give my information to the jemadar at the thana who will go in search of you, he being a new paragon of virtue who believes promotion and preferment come to those who make the most arrests—which, though he is wrong in his belief, will not prevent you, Anup, from weaving coir mats in the prison and being very humble when the kotwal thumps you with a club for staring through your grating at the stars."

"Hari bol!" said Anup. "I will find this man and I will bring the papers to your Honour."

Chullunder Ghose scratched at his stomach for at least a minute without speaking. Then:

"I am thinking," he said, "that men will wonder why you wander in the plains in the hot weather at a time when the stealing and selling of horses can be best conducted in the hills. No man will believe you are about your proper business unless you have a likely tale for them."

"I can say I pursue my enemy," said Anup.

"Yes, but then every one who has ever sold a horse to you, or has done you any other ill turn, will suppose himself to be the enemy; and one of them will surely go to the police with a bribe and persuade the police to arrest you."

"Give me some money. I also can bribe the police," suggested Anup.

"Why should my good money fatten the police?" Chullunder Ghose retorted. "Do the rogues not have their salaries, while you and I pay takkus? Nay, but you shall say this: 'He who stays the servant settles with his sahib? They will ask you then, who is your sahib? You will say Galloway sahib, being careful to add no word to that by way of explanation, because if Galloway sahib should hear of it he might be very angry."

A gleam of cunning shone in Anup's eyes, which Chullunder Ghose instantly and accurately read.

"Have a care!" he remarked. "Do you see that cobra with its head out of the basket?"

"Tsshyah! Its fangs are drawn," said Anup.

"Maybe, and maybe not. That is the Burman's business. But none has drawn Galloway sahib's fangs; and if he should learn that you have used his name for purposes of buying horses cheaper than the market price or frightening the peasantry, you will find he can strike like a she-cobra whose eggs lie hatching! There are sahibs who think they know much, but know little; and there are sahibs who know much, but spend all their time thinking. Galloway sahib, who is paghl and can hardly think at all, knows everything and strikes more swiftly than a snake at the beginning of the rains! So use his name as you would ride a vicious horse that you wish to sell to a money-lender, with a great display of confidence but no unnecessary showing off, and with alertness lest a false touch on the rein start the horse kicking all four ways at once and spoil the bargain."

NOW "Gnani" means Knower. He on whom that most respectful title is conferred by the mysteriously operating and unanimous consent of an unlettered public that knows nothing of and cares still less for university degrees is not a person to be treated with contempt by any one.

The eyes of Justice are usually represented as being bandaged, lest she should see too much and be bewildered by the sheer complexity of human problems. But Contempt never had any eyes, nor ever saw a fraction of an inch beneath a surface. India, that does not despise a Gnani, is likelier to understand him than are India's critics, most of whom would be afraid to take a full-grown tiger by the tail, for instance.

A Gnani may be ignorant of Einstein's theory and may not have read Darwin on The Origin of The Species; he almost certainly does not know how to build a rheostat, has probably not ridden in a Ford car or seen a motion picture. Yet to say that because of these peculiarities and because he wears his hair long and not many clothes, and because he dislikes daylight and the gaping crowd, the Gnani is ignorant is to talk stark nonsense that affects the Gnani not at all.

A gentleman who lugs a bag of clubs around a golf-course for amusement has a point of view that differs from a Gnani's, but that may not be said to be superior without investigation. Gnanis are not easy to investigate.