It has happened, times out of number, that in mid-Africa, in India, in the deserts of Transjordan*—on an ant-heap in the drought, or in the mud of the tropical rain—I have felt a yearning for white lights, a dress suit and a tall silk hat, that corresponds, I suppose, in some degree to the longing a city man feels for those open spaces and far countries which it has been my destiny to wander in and to write about. A traveler, if he is wise, comes home at intervals to meet old friends and to remind himself that a gentler, more conventional world exists, in which events occur and problems arise, and in which delightful people live and move and have their being.

[* Transjordan—The Emirate of Transjordan was an autonomous political division of the British Mandate of Palestine, created as an administrative entity in April 1921 before the Mandate came into effect. It was geographically equivalent to today's Kingdom of Jordan, and remained under the nominal auspices of the League of Nations, until its independence in 1946. Excerpted from Wikipedia. ]

Writing books is only another phase of living life—reliving it, perhaps, in which the appeal of the stiff white shirt transforms itself into a desire to write "civilized" stories. So this story, which is in an entirely different field from my usual haunts in Africa and India, may be said to represent a home-coming, between long journeys; and I hope the public, which has followed me with such encouraging persistence to comparatively unknown places, will concede that I still know how to behave myself in a civilized setting.

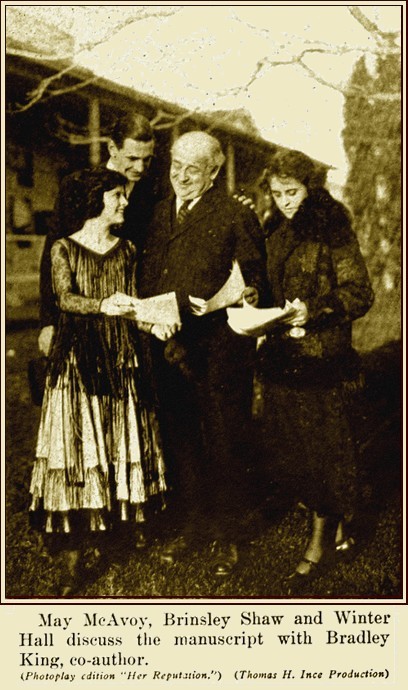

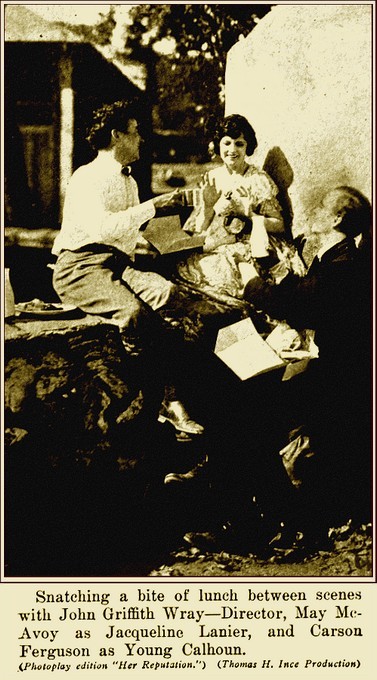

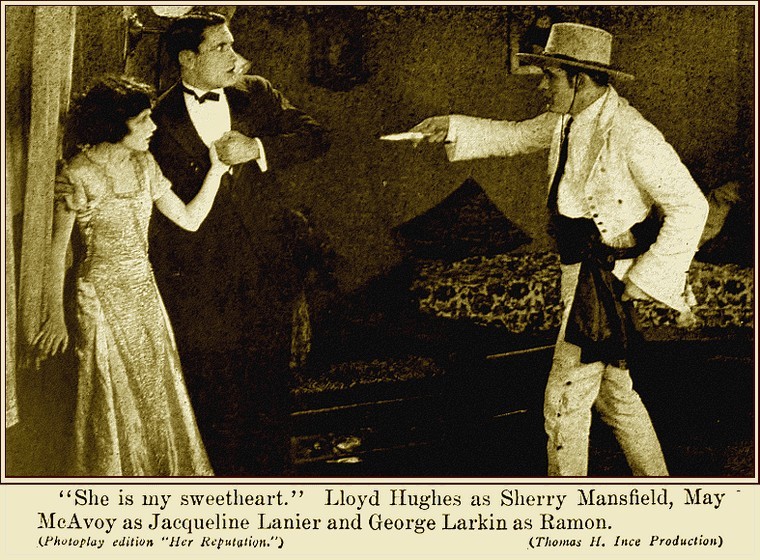

But this story is no more mine than is the life of the big cities into which I plunge at long, uncertain intervals. To Bradley King, chief of the Thomas H. Ince staff of editors, belongs the credit for the plot; her genius, art and imagination, and the creative vision of my friend Thomas Ince combined to produce a plan of narrative, now lavishly offered to the eye in a motion picture, which appealed me so strongly that the impulse to transform it into a written book was irresistible. The writing has been a delight to me, and I trust it may prove as entertaining to the public.

Bradley King detected, tracked, ran down and caught the idea for the story —a much more difficult thing to do than those who have never hunted such elusive game will ever guess. She trained it to perform; I wrote this book; and Mr. Ince has made the picture. We hope the book will be accepted by the reader, as it was written, purely to entertain; and that fellow newspaper men will recognize the friendly and entirely sympathetic illustration of the way in which the mighty and far-reaching power of the Press occasionally is abused by individuals.

—T.M.

There is an hour of promise, and a zero hour; the promise first; and promises are sometimes even sweeter than fulfillment. Jacqueline Lanier was unconscious of her hour of blossoming, and so the outlines of young loveliness had not been hardened by habitual self-assertion. Since she came under Desmio's care her lot had been cast in very pleasant places, and she was aware of it, wondering a little now and then, between the thrills of appreciation; but at seventeen we are not much given to philosophy, which comes later in life when we are forced to try to explain away mistakes.

She had come into the world a stormy petrel, but Consuelo and Donna Isabella were the only ones who remembered anything of that, and Consuelo took as much pains to obscure the memory as Donna Isabella did in trying to revive it. Both women were acceptable because everything whatever that belonged to Desmio was perfect—must be. Jacqueline used to wonder what under heaven Desmio could have to confess to on the occasions when he went into the private chapel to kneel beside Father Doutreleau. She herself had no such difficulties; there were always thoughts she had allowed herself to think regarding Donna Isabella. It had cost Jacqueline as much as fifty pater nosters on occasion for dallying with the thought of the resemblance between Donna Isabella and the silver-and-enamel vinegar cruet on the dining-room sideboard. And there was always Consuelo, fruitful of confessions; for you accepted Consuelo, listened to her comments, and obeyed sometimes—exactly as might happen.

Consuelo presumably had been born middle-aged and a widow, and so would remain forever, as dependable as the silvery Louisiana moon that made the plantation darkies love-sick, and as the sun that peeped in every morning between the window-sill and the lower edge of the blind.

You brush your own hair at the convent, but that makes it no less desirable to have it brushed for you at home during the Easter Congé, especially if the hair grows in long dark waves like Jacqueline's. At the convent you stand before a small plain mirror, which in no way lessens the luxury of a chair at your own dressing-table, in your own delightful room fronting on the patio balcony, in Desmio's house, while Consuelo "fixes" you.

At the convent you wear a plain frock, all the girls dressed alike; but that does not detract from the virtue of silken underwear and lacy frocks at home.

"Hold your head still, Conchita!"

All Easter week Consuelo had been irritable, and Jacqueline's blue eyes watched curiously in the mirror the reflection of the duenna's plump face and the discontented set of the flexible mouth. There was a new atmosphere about the house, and the whole plantation vaguely re-suggested it, as if Desmio's indisposition were a blight. Yet Desmio himself, and the doctor and Father Doutreleau, and Consuelo had all been at pains to assure her that the illness was nothing serious. True, Donna Isabella had dropped ominous hints; but you could not take Donna Isabella's opinions quite seriously without presupposing that there was nothing good in the world, nor any use hoping for the best.

"Why are you worried, Consuelo?"

The critical lips pursed, and the expression reflected, in the mirror became reminiscent of younger days, when a child asking questions was discreetly foiled with an evasive answer.

"Because your hair is in knots, Conchita. At the convent they neglect you."

"I am supposed to look after myself in the convent."

"Tchutt! There is no reason why they should teach you to neglect yourself."

"They don't. The sisters are extremely particular!"

"Tchutt! They don't know what's what! It's a mystery to me they haven't spoilt your manners—"

"Why—Consuelo!"

"Nobody can fool me. You'll never have to look after yourself, Conchita —whoever says it!"

That was one of those dark sayings that had prevailed all week. Jacqueline lapsed into silence, frowning; and that made Consuelo smile, for as a frown it was incredible; it was just a ripple above lake-blue eyes.

"You can't tell me!" exclaimed Consuelo, nodding to her own reflection in the mirror as she put the last few touches to the now decorously ordered hair. Next day's rearrangement at the convent would fall short of this by a whole infinity.

"Can't tell you what, Consuelo?"

Pursed lips again. But the evasive answer was forestalled by a knock on the door, and Jacqueline drew the blue dressing-robe about her; for there was no doubt whose the knock was, and you never, if you were wise, appeared in disarray before Donna Isabella. You stood up naturally when she entered. As the door moved Consuelo's face assumed that blank expression old servants must fall back on when they dare not look belligerent, yet will not seem suppressed.

"Jacqueline—"

Donna Isabella alone, in all that house, on all that plantation, called her Jacqueline and not Conchita.

"—don't keep the car waiting."

Jacqueline glanced at the gilt clock on the dressing-table. There was half an hour to spare, but she did not say so, having learned that much worldly wisdom. She watched Donna Isabella's bright brown eyes as they met Consuelo's. Consuelo left the room.

Donna Isabella Miro stood still, looking like one of those old engravings of Queen Elizabeth, until the door closed behind her with a vicious snap in token of Consuelo's unspeakable opinion.

It was one of her characteristics that she kept you standing at attention quite a while before she spoke.

She had her brother's features, lean and aquiline, almost her brother's figure; almost his way of standing. Dressed in his clothes, at a distance, she might even have been mistaken for him. But there the resemblance ended. To Jacqueline, Don Andres Miro had been Desmio ever since her three-year-old lips first tried to lisp the name. It had been easiest, too, to say "Sabella," but at three and a half the Donna had crept in, and remained. At four years it had frozen into Donna Isabella, without the slightest prospect of melting into anything less formal.

"I hope, Jacqueline, that in the days to come you will appreciate how pleasant your surroundings were."

"Do I seem not to appreciate them, Donna Isabella?"

The older woman smiled—her brother's smile, with only a certain thinness added, and an almost unnoticeable tightening of the corners of the lips.

"I hope Don Andres' kindness has not given you wrong ideas."

"Donna Isabella, how could Desmio give anybody wrong ideas? He's— he's—"

Words always failed when Jacqueline tried to say what she thought of Desmio.

"He is absurdly generous. I hope he has not ruined you, as he would have ruined himself long ago, but for my watchfulness."

"Ruined me? How could he?"

"By giving you wrong notions, Jacqueline."

"Wrong, Donna Isabella?"

Jacqueline had all her notions of life's meaning from Desmio. His notions! None but Donna Isabella would have dreamed of calling them by that name! They were ideals; and they were right—right—right—forever right!

"Wrong notions about your future, Jacqueline. Fortunately"—how fond she was of the word fortunately! "Don Andres can never adopt you legally. There is no worse nonsense than adopting other people's children to perpetuate a family name, and we have cousins of the true stock."

Lanier blood is good, and Jacqueline knew it; but, as Consuelo said, the convent had not spoiled her manners. She said nothing.

"So—incredibly kind though Don Andres has been to you—you have no claim on him."

The frown again—and a half-choke in the quiet voice; "Claim? I'm grateful to him! He's—"

But words failed. Why try to say what Desmio was, when all the world knew?

"Do you call it gratitude—after all he has done for you— knowing what his good name and his position in the country means to him —to make a scene—a scandal—at church on Easter Sunday, of all days in the year, with nearly everybody in the county looking on?"

"I made no scene, Donna Isabella."

"Jacqueline! If Don Andres knew that Jack Calhoun had walked up the middle of the aisle during High Mass, and had given you an enormous bouquet which you accepted—"

"Should I have thrown the flowers into the aisle?" Jacqueline retorted indignantly. "I put them under the seat—"

"Accepted them, with half the county looking on!"

"I didn't want to make a scandal—"

"So you encouraged him!"

Jacqueline controlled herself and answered calmly, but the incorrigible frown suggested mirth in spite of her and Donna Isabella's lean wrists trembled with suppressed anger.

"I have always avoided him. He took that opportunity for lack of a better, Donna Isabella."

"Can you imagine a young gallant bringing flowers to me during High Mass?"

It was easy to believe that the whole world contained no gallant brave enough for that effrontery! Her narrow face was livid with malice that had seemed to increase since Desmio's illness.

"If Don Andres knew that for months Jack Calhoun—"

"Let me tell him!" urged Jacqueline. Her impulse had been to tell him all about it long ago. He would have known the fault was not hers, and would have given her good advice, instead of blaming her for what she could not help; whereas Donna Isabella—

Donna Isabella stamped her foot.

"I forbid! You cause a scandal, but you never pause to think what it will mean to those it most concerns! As if your name were not enough, you drag in one of the Calhouns—the worst profligates in Louisiana. The shock will kill him—I forbid you to say a word!"

One learns obedience in convents.

"Put your frock on now, and remember not to keep the car waiting. You can say good-by to Don Andres in the library, but don't stay too long in there. He mustn't be upset. Try this once to be considerate, Jacqueline."

There is virtue even in spitefulness, for it makes you glad when people go, which is better after all than weeping for them. Jacqueline's quick movement to open the door for Donna Isabella failed to suggest regret. Consuelo's—for her hand was on the door-knob on the far side— deliberately did not hint at eavesdropping; she was buxom, bland, bobbing a curtsey to Donna Isabella as she passed, and in haste to reach the closet where the frocks hung in two alluring rows.

"The lilac frock, Conchita?"

Then the door closed, a pair of heels clip-clipped along the balcony, and Consuelo's whole expression changed as instantly as new moons change the surface of the sea. With a frock over her arm she almost ran to Jacqueline, fondling her as she drew off the dressing robe.

"What did she say, honey? Conchita—was she cruel? Was she unjust?"

But at seventeen we are like birds, who sing when the shadow of the hawk has passed, and Jacqueline's smile was bright—invisible for a moment —smothered under a cloud of lilac organdy.

"Careful, Consuelo! There's a hook caught in my hair!"

Whereat much petting and apology. Clumsy, Consuelo—kindness crystallized—and adding injury to insult! Consuelo self-abased:

"Mi querida—tell me—did she speak of that young cockerel?"

There are some fictions we observe more carefully the more opaque they are. Consuelo had been listening, and Jacqueline knew it. The evasive answer works both ways.

"She said I must be quick, Consuelo."

Hats—a galaxy of hats—Consuelo would have had her try on half a dozen, but Jacqueline snatched the first one and was gone, as a young bird leaves the nest. Sunlight streamed into the patio and touched her with vague gold as she sped along the balcony. Down the wide stone stairs latticed shadows of the iron railing produced the effect of flight, as if the lilac organdy were wings. Then—for they teach you how to walk in convents —across the courtyard between flowers and past the gargoyle fountain toward Desmio's library, Jacqueline moved as utterly unconscious of her charm as Consuelo, watching in the bedroom doorway, was aware of it.

And something of the fear that she had seen in Don Andres' eyes of late, clutched at the old nurse's heart. Lanier beauty—Lanier grace— the Lanier heritage of sex attraction—Jacqueline had them all. An exquisite tropical butterfly, fluttering on life's threshold, unconscious of covetous hands and covetous hearts that would reach out to possess her. What lay ahead of those eager little feet?

"Oh, Mary, take care of her!" she muttered—adding more softly, "Poor Calhoun!" Then thoughts reverting to Donna Isabella—"She would turn my honey-lamb out into the world! Not while I live! Not while I have breath in me!"

But Jacqueline's only thought was Desmio. It banished for the moment even the memory of Donna Isabella. We can be whole-hearted at seventeen; emotions and motives are honest, unconcerned with side-issues. She entered the library as she always did, frank and smiling, glad to see him and have word with him, and as she stood for a moment with the sunlight behind her in the doorway, he rose to greet her. Father Doutreleau rose too, out of the depths of an armchair, eager to persuade his friend to sit down again, but neither priest nor physician lived who could persuade Don Andres to forego courtesy.

"So you are on your way again, Conchita—and so soon!"

"It was your wish that I should attend the convent Desmio."

"How is the heart?" she asked him.

"Yours, Conchita! You should know best!"

So he had always spoken to her. Never, from the day when Consuelo carried her in under the portico, and Desmio had taken her into his arms and keeping, had he ever treated her as less than an equal, less than a comrade.

He was not more than middle-aged, but his hair and the grandee beard were prematurely gray. Short lines about the corners of his bright brown eyes hinted that to walk the earth with no dignity is no way of avoiding trouble and responsibility. He sat in the high-backed chair as one of his forebears might have sat to be painted by Velasquez, and it called for no great power of imagination to visualize a long rapier at his waist, or lace over the lean, strong wrists. Yet, you were at ease in his presence.

"You will come to see me, Desmio?"

His answering smile was much more eloquent than if he had said "of course." It implied that his indisposition was only temporary; it mocked his present weakness, and promised improvement, asking no more for himself than a moment's forbearance. If he had said wild horses should not prevent him from visiting Jacqueline at the convent, words would have conveyed less than the smile.

"I shall come to the convent to listen to the Sister Superior's report of you—and shall return to Father Doutreleau to sit through a sermon on pride!"

"Desmio, you are incorrigible."

"So says Father Doutreleau! The fault is yours, Conchita. How shall I not be proud of you?"

Jacqueline leaned on the arm of the chair and kissed him, making a little moue at Father Doutreleau, who sat enjoying the scene as you do enjoy your patron's happiness. There was a world of understanding in the priest's round face, and amusement, and approval; better than most, he knew Don Andres' sheer sincerity; as priest and family confessor, it was his right to approve the man's satisfaction in such innocent reward. But it was the priest's face that cut short the farewell. Jacqueline detected the swift movement of his eyes, and turned to see Donna Isabella in the door.

"Consuelo is waiting for you in the car, Jacqueline."

Don Andres frowned. He disliked thrusts at Jacqueline. For a moment his eyes blazed, but the anger died in habitual courtliness toward his sister. Blood of his blood, she was a Miro and entitled to her privileges.

"Good-by, Conchita," he said, smiling.

Jacqueline's hand, and Father Doutreleau's kept him down in the chair, but he was on his feet the moment she had started for the door. She glanced over her shoulder to laugh good-by to him, but did not see the spasm of pain that crossed his face, or the uncontrolled movement of the hand that betrayed the seat of pain. She did not see Father Doutreleau leaning over him or hear the priest's urging:

"Won't you understand you must obey the doctor?"

All Jacqueline heard was Donna Isabella's voice beside her, as usual finding fault:

"Perhaps, while you are at the convent we may be able to keep Don Andres quiet. At the convent try to remember how much you owe to Don Andres' generosity, Jacqueline—and don't dally with the notion that he owes you anything. Good-by."

And so to the convent, with Donna Isabella's farewell pleasantry not exactly ringing (nothing about that acid personage could be said to ring, true or otherwise) but dull in her ears. Consuelo did not help much, she was alternately affectionate and fidgety beside her—fearful of Zeke's driving, and more afraid yet of the levees, where the gangs were heaping dirt and piling sand-bags against the day of the Mississippi's wrath.

Consuelo bemoaned the dignified dead days of well matched horses. But, like everything else that was Desmio's, Jacqueline loved the limousine. Stately and old-fashioned like its owner, it was edged with brass, and high above the road on springs that swallowed bumps with dignity. Desmio's coat-of-arms was embroidered on the window-straps; and, if the speed was nothing to be marveled at, and Zeke's driving a series of hair-breadth miracles, it had the surpassing virtue that it could not be mistaken for anybody else's car. Men turned, and raised their hats before they could possibly have seen whether Desmio was within or not.

"You throw away your smiles, Conchita!"

"Should I scowl at them, Consuelo?"

"Nonsense, child! But if you look like an angel at every jackanapes along the road, what kind of smile will you have left for the right man, when the time comes—the Blessed Virgin knows, that's why young Jack Calhoun—"

Jacqueline frowned.

"Mary, have pity on women!" she muttered half under her breath. "I wish I might tell Desmio."

"Tchutt! You must learn for yourself, Conchita. Don Andres has enough to trouble him."

The frown again. Learn for herself. In the convent they teach you the graces; not how to keep at bay explosive lovers. Though he had seized every opportunity for nearly a year to force himself on her notice, she had never been more than polite to Jack Calhoun, and she had been a great deal less than polite since she had grown afraid of him.

Consuelo had studied that frown for seventeen years.

"You'll be safe from him in the convent, honey," she said, nodding, and Jacqueline smiled.

But as they drove along the convent wall toward the old arched gateway —the smile changed suddenly, and something kin to fear— bewilderment at least—wonder, perhaps, that the world could contain such awkward problems—brought back the frown, as Consuelo clutched her hand.

"Look daggers at him, child!"

You can't look daggers with a face like Jacqueline's. That is the worst of it. You must feel them first, and faces are the pictured sentiments that we are born with, have felt, and wish to feel. Not even at Jack Calhoun could she look worse than troubled. And it needed more than trouble—more than Consuelo's scolding—more than Zeke's efforts at the throttle and scandalized, sudden manipulation of the wheel, to keep Jack Calhoun at a distance. He had been waiting, back to the wall, twenty paces from the gate, and came toward them sweeping his hat off gallantly. One hand was behind him, but it would have needed two men's backs to hide the enormous bouquet. Love —Calverly—Calhoun brand, which is burning desire—was in eyes and face—handsome face and eyes—lips a little too much curled—chin far too impetuous—bold bearing, bridled —consciousness of race and caste in every well-groomed inch of him. He jumped on the running-board as Zeke tried vainly to crowd him to the wall, and the bouquet almost choked the window as he thrust it through.

"Miss Jacqueline—"

But a kettle boiling over on the stove was a mild affair compared to Consuelo. She snatched the flowers and flung them through the opposite window.

"There, that for you!" She snapped her fingers at him, and Jacqueline learned what looking daggers means. "I know you Calhouns! Be off with you!"

Jack Calhoun laughed. He liked it. Lambs in the fold are infinitely more sweet than lambs afield. He loved her. He desired her. So should a Calhoun's wife be, as unattainable as Grail and Golden Fleece, that a Calhoun might prove his mettle in the winning. He had a smile of approval to spare for Consuelo; her wet cat welcome left him untouched, just as Jacqueline's embarrassment only piqued his gallantry.

"Miss Jacqueline—"

He had a set speech ready. He had phrased and memorized it while he waited. By the look of his horse, tied under a tree a hundred yards away, he had been there for hours, and it was a pity that the fruit of all that meditation should be nipped by the united efforts of a Consuelo and a Negro coachman. But so it fell; for Zeke leaned far out from the driver's seat and tugged at the big bell-handle by the gate; and Consuelo, leaning her fat shoulder on the car door, opened it suddenly, thrust herself through the opening and, forced Jack Calhoun down into the dust.

"That much for you!" she exploded, and he laughed at her good-naturedly; so that even Consuelo's angry brown eyes softened for the moment. He had breeding, the young jackanapes, and the easy airy Calhoun manners. She almost smiled; but she could afford it, for the convent gate swung open and lay-sister Helena stepped out under the arch to greet Jacqueline.

Jack Calhoun was balked, and realized the fact a second too late. He ran around the limousine; but by the front wheel Zeke blocked the way with the wardrobe trunk, and Jacqueline was already exchanging with Sister Helena the kiss the convent rules permitted.

Accept defeat at the hands of women and a Negro coachman, God forbid! Jack Calhoun ran around the limousine again, jumped through the door and out on the convent side, too quick for Consuelo, who tried in vain to interpose her bulk.

"Miss Jacqueline—!"

Sister Helena drew Jacqueline over the threshold. That was sanctuary. Not even a Calhoun would trespass there without leave; and there were Zeke and Consuelo, beside ample lay-help near at hand. Also, there was human curiosity —the instinct of the woman who had taken vows, which in no way precluded interest in another's love-affair.

"May I—won't you say good-by to me, Jacqueline?"

Why not! What wrong in shaking hands at convent gates? Sister Helena glanced at Consuelo, but Consuelo was inclined to pass responsibility; her guardianship ended where the convent wall began, and she was definitely frankly jealous of the sisters. She looked vinegary, non-committal.

"It will be so long before I can see you again!"

Jacqueline shrank back for no clear reason, but instinctively. There was a look in his eye that she did not understand. It suggested vaguely things the convent teaching did not touch on, except by way of skirting deftly around them with mysterious warnings and dim hints. The wolf knows he is hungry. The lamb knows she is afraid. The onlooker reckons a sheepfold or a convent wall is barrier enough.

"Won't you tell me good-by, Jacqueline?"

She held out her hand, with the other arm around Sister Helena, ashamed of her own reluctance. Why! By what right should she refuse him common courtesy? He had never done a thing to her but pay her compliments. Jack Calhoun crossed the threshold, seized her hand and kissed it. She snatched the hand away, embarrassed—half-indignant—still ignorant of causes.

"There—there—now you've had your way—be off with you!" Consuelo thrust herself between them, back toward Jacqueline and face to the enemy.

Calhoun backed away, hardly glancing at Consuelo, watching Jacqueline over the fat black-satined shoulders. There was acquisition in his eyes now —the look of the practiced hunter whose time is not quite yet, but who has gauged his quarry's points and weakness. Three paces back he bumped into Zeke with the trunk. The trunk fell on his feet but he ignored it; if it hurt him, none but he knew; Zeke's protestations fell on deaf ears. Midway between gate and limousine he stood watching the trunk rolled in, and Consuelo's wet- eyed leave-taking—watched Consuelo come away, and saw the great gate slowly closing—watched like a hunter. Then, with the gate half-shut, he caught Sister Helena's eye, and the appeal in his made her pause. Hearts melt under dark-blue habits easily. The gate re-opened by as much as half a foot, disclosing Jacqueline again. Eyes met hers brimming full of tenderness for Consuelo, who had said such foolishness as nurses do say—tender, and then big with new surprise.

It was Jack Calhoun's heart leaping now. Had he won already? Was she as glad as all that for another glimpse of him? The hot blood rose to his temples, and the hot assurance to his lips. He would have been no Calverly-Calhoun if he could keep that tide within limits.

"I love you, Jacqueline—I love you!" he almost shouted. Then the gate shut—tight. He heard the chain-lock rattle and the key turn; and he laughed.

Consuelo's voice beside him brought him out of reverie.

"She's not for you—not for the likes of you!"

"Did you hear me say I love her, Consuelo?"

He was watching Consuelo's face, pondering how to turn an adversary into a confederate, probing to uncover her weakness. She being Consuelo, and he a Calverly-Calhoun, he was absolutely certain to guess wrong as he was sure his guess would be infallible.

Consuelo looked almost panic-stricken, and Jack Calhoun's lip curled again in that heredity-betraying smile. He thought he saw the joint in her armor. Old nurses, pension in view, may well dread dismissal and the search for new employment. Doubtless Don Andres would visit his wrath on Consuelo if he should think she had failed in her task as duenna. He knew the Calhoun reputation and could guess what Don Andres thought of it.

"I will call on Don Andres," he repeated.

"No, no!" She was almost imploring now. "Worry on Miss Jacqueline's account would kill him! He is seriously ill. You must—"

"What then," he interrupted. His hand went to his pockets, and the offer of a bribe was plain enough if she would care to take it.

"What then, Senor? Aren't you a Calhoun? Aren't you a gentleman?"

He put his hands behind him—legs apart—head thrown back handsomely. He had Consuelo at his mercy; he was sure of it; and none ever accused the Calverly-Calhouns of being weakly merciful.

"To oblige you, Consuelo, I'll say nothing to Don Andres at present —provided you reciprocate."

"In what way, Senor?"

He laughed. "One may safely leave fond nurses to discover ways and means," he answered. "Are letters mailed to young ladies at the convent censored by the nuns?"

"Of course, Senor. What are you thinking of?"

"If you will smuggle in a letter to Miss Jacqueline, I will not mention to Don Andres that you have permitted me more than one interview with her. Otherwise,—my sentiments toward her being what they are—you leave me no alternative."

For a second his eyes glanced away from Consuelo's. She understood the glance; Zeke was listening. Jack Calhoun's smile left his lips and crept into his eyes. Consuelo began to stammer something, but he interrupted.

"I will write a letter to Miss Jacqueline. Tomorrow I will call on Don Andres to inquire after his health. If you should meet me in the patio, and take the letter, I will make no intimate disclosures to Don Andres. Are we agreed?"

Consuelo bit her lip, and nodded.

"Tomorrow then—in the patio—shortly before noon. Don't disappoint me!"

Consuelo could not trust herself to answer, but stepped into the limousine, nodding to him a second time through the window. Words would have choked her. Jack Calhoun, smiling as his father used to smile when ships left port with contraband, gave Zeke a fifty-dollar bill—checked the old darky's exclamations with a gesture—waved the limousine on its way —and stood watching until it was nearly out of sight. Then he went for his horse and rode homeward at full gallop, using the spurs unmercifully.

"My Jacqueline! My Jacqueline!" he sang as he rode. "I love her and she's mine! My Jacqueline!"

The gangs mending a levee had to stop work and scatter to let him pass. His horse knocked a man down, and a foreman cursed him for it, calling him by name.

"Ye daren't get off that horse and act like a man! Ye're all dogs, you Calhouns!"

Jack did not hesitate a second, but reined it and dismounted. When he rode away five minutes later the foreman was a bruised and bleeding wreck, unfit for work for a week to come.

Consuelo, leaning back against the cushions in the limousine, her fat bosom heaving as if she had run uphill, did not dare trust herself to let a thought take shape for twenty minutes. She could not have defined her own emotions. Fury—indignation—fear for Jacqueline—contempt for Zeke, who had accepted a bribe—an old nurse's faithful love, that can be tigerish as well as sacrificing—a ghastly, sinking sense of the dilemma facing her—and helplessness, were all blended into one bewildering sensation. And through that drummed the certainty that she, Consuelo, must do something about it.

She knew that Don Andres loved Jacqueline with infinitely more delight that he had loved his own daughter, whose resemblance to Donna Isabella had been too obvious, even at the age of ten, to stir paternal sympathies. Her death, leaving him with no direct heir and a widower, had hurt his family pride more than his affection, and it was not until Jacqueline entered his household that his inmost heart was really touched. Jacqueline, at three, had stepped into an empty place, and filled it. Spanish herself, Consuelo knew the depths of Don Andres' distaste for public scandal. Gossip and the name of Calverly-Calhoun were almost synonymous terms. Gossip and Don Andres Miro were as fire and water.

Zeke being nearest, was the first who must be dealt with. She began at once:

"How much did he give you, Zeke?" she asked, sliding back the glass panel behind the driver's seat.

Zeke attended to the driving thoughtfully for a good long minute before he showed her the crow's-footed corner of an eye and a silhouette of snub nose over pursed protruding lips.

"Didn't yo' see?"

He returned to his driving. His shoulders grew eloquent of marvelous unconcern for Consuelo, or anything connected with her.

"You—Zeke—why did he give it to you?"

Another minute's silence—then Zeke's eye, wide-open trying to look around the corner of his head, and thick lips opened impudently:

"He likes muh—don't you s'pose?"

Enough of Zeke. He would tell what he knew, or not tell, with or without exaggerations, as Calhoun might instruct. Meanwhile, he would use his own discretion, and by night the servants' hall would have three versions of the affair, as surely as Zeke would have a headache on the morrow. And by morning Donna Isabella would have her own embittered version of the scandal.

Consuelo leaned back again against the cushions, thinking. Hers was a lone hand. Somewhere midway between master and domestics, with no clearly defined position in the household now that Jacqueline was growing up, she had the distrust of both sides to contend with. Insofar as she ever came in contact with Don Andres he was kind and courteous to her, but Donna Isabella had taken care to prevent confidential relations between master and nurse, and pride kept Don Andres from interfering with his sister's authority in the household. Yet she did not dare go to Donna Isabella and take her into confidence. As well ask a she-wolf to be sympathetic.

And she knew the Calverly-Calhouns—knew that Jack Calhoun would hesitate at nothing. Worse still—the boy had brains. It was likely enough to dawn on him that Donna Isabella was the key to the situation. What was to prevent him from approaching her? And what was more likely than that Donna Isabella would exaggerate the scandal? Her jealousy knew no limits. She might succeed in convincing Don Andres that marriage to Jack Calhoun was the only way to prevent Jacqueline from becoming a subject of light gossip of the countryside.

There was one way left then—deadly dangerous to herself. She must go to Don Andres, and tell him everything. That thought brought memories. Once—a year or two before the convent days—there had been a governess, who had dared to approach Don Andres with complaints about Donna Isabella's injustice to Jacqueline. Of all insufferable indignities the one Don Andres tolerated least was tale-bearing against those whom it pleased him to honor, and the governess had left the house that night. She had been young, with new positions open to her; Consuelo, well past fifty, with about three hundred dollars in a savings bank, had no delusions as to how the world would treat her, once dismissed. But she thought of Jacqueline, and the little dancing frown above the lake-blue eyes:

"Mother of God, protect me! I will tell Don Andres," she said, half- aloud, as if afraid to hear her own voice. She crossed herself, knelt in the limousine, and prayed.

She was dry-eyed—dry-lipped—businesslike, when the limousine rolled under the portico and Zeke waited for her to climb out as she pleased. Consuelo would have scolded him for it at any other time, but she was in no mood for trivialities; great resolution had her by the shoulders; she rang the old-fashioned door-bell with a jerk and a clang that startled her. But they knew it was only Consuelo, and the footman kept her waiting.

She heard his footsteps at last on the tiles, and heard him pause in the hall, midway between patio and front door, where dining-room and drawing-room opened off to the right and left. When he came to the door his black face was a dumb enigma, and she saw beyond him the figure of Donna Isabella, frowning sourly under the drawing-room portière. She would have walked past with the usual old-fashioned bobbing curtsey, but Donna Isabella stopped her:

"Why do you use the front door, Consuelo?"

Silence. Pursed lips. Attention.

"The fact that you are an old servant is no excuse for forgetting your manners."

Consuelo's manners at that moment were a galleon's in full sail down- wind. She had cut her cables—thrown away her charts—was forth on life's last adventure.

Forget her manners? She dipped her pennant and sailed on, leaving Donna Isabella to put what construction she might choose on utter silence.

Straight to her own room. Off with her hat and cape, firm-lipped and resolute—crossing herself before the image of the Virgin. Out again, straight to the patio and toward the library.

Then, at the library door, sudden weak knees and emptiness. The zero hour! She was keyed up for sacrifice; but what if it should be in vain?

Her knuckles rapped the door—so hard that they hurt before she could prevent them.

"Come!"

Too late! "O Mother of God, put courage into me, and words into my mouth! I don't know what to say to him "

The door was shut behind her, and she was midway across the room, hardly knowing how it had happened. Don Andres was in the high-backed chair, laying down a book, his other lean, long, veined hand resting on the chair-arm.

"What is it, Consuelo?"

Then, suddenly, all fear and all discretion to the winds! Words came —from somewhere—sounding to Consuelo like another woman's speaking in a voice she hardly knew.

"Don Andres—have I been a good servant to you?"

"I have always thought so, Consuelo."

He was too courteous to seem surprised. His eyes looked kind, not critical. How could it be that such a man had enemies? Consuelo dropped on her knees on the floor beside the footstool, clasping her hands on her bosom.

"Don Andres—I come to you as your servant now! I mean no harm to any one, and if I offend you, dismiss me and I will go in silence. Only hear me to the end first!"

"You may tell me what is in your mind, Consuelo."

"Don Andres—it is about Miss Jacqueline—Mr. Jack Calhoun is making love to her. He made a scene at the convent gate, and I could not keep him away from her, although I tried!"

He nodded, looking grave. He was perfectly sure how faithfully Consuelo would have tried.

"He made a scene at church on Easter Sunday."

Don Andres frowned.

"Why has Jacqueline not told me of all this?"

"She was forbidden—she wished to, Don Andres,—she was forbidden months ago to tell you anything."

"Did you advise her not to tell me?"

"God forbid! Don Andres, that innocent has never had another secret from you. As God is my witness, there is nothing in her life until this, that you did not know."

He nodded again. There was only one other individual in the household who might have imposed restraint. But his nod was in recognition of Consuelo's tact in not mentioning the individual's name.

"Does she respond to Mr. Calhoun's attentions?"

"She fears him, Don Andres! What does she know of men? She shrinks away from him, and he pursues her! She does not understand. She only knows there is something that she doesn't understand. He fascinates her—he has made up his mind—he is set on winning her—and—Don Andres—you know those Calverly-Calhouns!"

He overlooked the last part of her speech. The Calverly-Calhouns for generations had been his equals.

"Have you had speech with him with reference to this?" he asked after a moment's pause.

So Consuelo told him all that Jack Calhoun had said, and of the bribe to Zeke, and of her own unspoken promise to meet Jack Calhoun in the patio next day and take a letter from him. She stammered over the last part, for she had not been in that household fourteen years without knowing the master's method with servants who consented to intrigue. His deep frown frightened her —it was only a matter of moments now.

"Stand up, Consuelo," he said at last, and she struggled to her feet, biting her lip, awaiting her dismissal.

"Did he offer you money?" he asked.

"I don't think he dared, Don Andres."

"You agreed to smuggle his letter into the convent?"

"Don Andres—what else could I dot?—I haven't the power to manage him otherwise—I'm an old woman, and he laughs at me— unless he thinks he can use me he'll go to—to some one else—and they'll make a scandal between them to—to—"

The nod again—cryptic—dry. The dark eyes deadly serious. A too long pause, as if he were unmercifully framing words. The thin lips tightly set.

"You were always a good servant, Consuelo."

Were! So the end had come. Her heart sank, for the awaited is not less terrible when it arrives. She bowed her head, remembering she would go in silence.

"I am not ungrateful for good service, or unconscious of my obligation to reward it. You may leave that part to me. But I will tolerate no insubordination in my house. You understand me?"

She did not. She looked hurt now—amazed. She had never been insubordinate. A little of the meekness left her: She would not go in silence after all. She would tell him to his face what a faithful servant suffered constantly at Donna Isabella's lips—how much had to be endured for his sake—she would seize an old woman's privilege of speech and pour out all she knew! But he spoke again before she could begin and even in that moment of indignation she could not force herself to interrupt him.

"You must continue as if this interview with me had never taken place. You understand?"

Slowly his meaning dawned on her.

"Am I not dismissed?" she asked, her face reddening.

He ignored the question. "There must be no impudence or disobedience. No dark looks, Consuelo. No suggestion of an understanding with me behind another's back. No Spying. No tales to me. No indignities to—any one."

Consuelo bobbed her old-fashioned curtsey. Words would have been empty in the presence of that magnificent consistency. For his pride's sake she would let Donna Isabella drive nails into her—poison her—malign her —and she would say nothing! Followed emotion, making the stout bosom nearly burst the black satin bodice. Tears. Smothered, sobs into a handkerchief.

"There—that will do." He loathed anything undignified. "I will ask Donna Isabella to excuse you from duty until tomorrow morning."

Consuelo went without another word. Don Andres did not pick up the book again but sat staring into vacancy—alone—dismally lonely, and too proud to admit it even to himself. The house, and his whole life, were empty without Jacqueline. She was all the brightness he had ever known and to send her to school at the convent was his master-sacrifice. He broke into a smile as he thought of her, and the smile died away into a swordsman's frown, teeth showing through the parted lips, as he remembered stage by stage the fight he had waged for her—a memory that Consuelo's news had only sharpened. So an affair with Jack Calhoun was to be the next difficulty! He wondered how deeply Isabella was already mixed in it.

Well he understood his sister Isabella. She had opposed his determination to accept the child's guardianship; and that failing, she had tried to wean Jacqueline away from him and make her a dried-up image of herself—even as she had succeeded in doing with his own only child. But his own child had been a Miro. He did not disguise from himself that the Miro blood was dying—the direct Miro line near its end. Isabella had succeeded with that daughter of his; the weak twig of an ancient tree had come easily under her sway, had wilted under it, and died. But nothing in Jacqueline's nature had provided Isabella any thing to work on. Rather she responded to his own lavished affection and Consuelo's mothering; and that had given Isabella deeper offense than the original crime of introducing the child into the household.

He had made up for Isabella's bitterness, by giving Jacqueline every advantage and every privilege within his means. And the means of the Miros in Louisiana are beyond the scope of most men's dreams.

So the house was lonely now Jacqueline was at the convent—felt like a tomb, for all its decorous luxury. Don Andres Miro, possibly the best loved, certainly the richest and most respected among the old Louisiana Settlers, felt like a man with no occupation left. He was much too proud to feel sorry for himself; he would have smiled if run through with a rapier. But pride heals no heart-ache—fills no empty nest.

And Calverly-Calhoun? He knew that breed! No scion of that stock for Jacqueline! He had intimately known two generations of Calhouns, and could guess the hourly anguish of the women they had married. Good women don't reform bad men, they only irritate them; he knew that. He would rather, if necessary, see Jacqueline married to some young fellow without family, but of decent means and good repute, who would know enough to appreciate her and treat her with respect. But there was fortunately no hurry about that, and only need for vigilance. Meanwhile—

He would have one more try—if necessary he would call in the United States Attorney-General himself—to find some flaw in the Miro trust deed. If, subject to provision for his sister Isabella, he might leave by will the whole of his estates to Jacqueline, then—

Again the proud smile. That would be a true gift given from the heart —the reply complete to Isabella—and, by no means the least amusing part of it, a full expression of contempt for John Miro, his distant cousin, now heir legal and presumptive, whose Lynn shoe-factory was a disgrace and scandal to the Miro name. If by any legal means it might be possible, he would bequeath to Jacqueline every last acre and investment of the Miro fortune.

To that end he must preserve his health. It was important that he should have his wits about him and the strength to see possible law-suits to a conclusion; for it was no part of his determination to leave a mere document behind him, over which and his dead body Jacqueline should have to fight the gum shoe-maker. She would have no chance unless, he, Andres Miro, should do the fighting for her. He would do that, bitter though he knew the fight might be.

The difficult days, he recognized, were coming. All that lay behind was child's-play compared to the road ahead. Obstruct Calhoun and there would be other suitors to be fenced with. When a rumor should creep abroad, as it inevitably must, that the estates might fall to Jacqueline, every needy adventurer on the countryside would add his importunities to the confusion. Then more than ever Jacqueline would need his comradeship and guidance. He must throw the weight of years aside, and attend to it that his company should be a pleasure to her and not a burden. To that end, he must resume his youth and be more spirited and companionable than any of the young bloods she should meet. Well—he considered that not impossible. Only he must get well. A man needs health before he can be young again; and doctors—he did not know how much faith to place in even his family physician; the man never seemed to know his own mind—but then, the Miros were ever a long-lived breed. Why theorize about disease, when long life was hereditary fact?

His reverie was interrupted by Father Doutreleau who came and went in that house pretty much as his own pleasure dictated. He was as close to Andres on the one hand as Jacqueline was on the other, so that apart altogether from his office of confessor, François Doutreleau was intimate in Miro's councils, knew his secrets, and was one of the three men who discussed them with him.

"Forgive me if I remain seated, François. It's your own medicine! Ring the bell, won't you, and we'll have some wine brought in."

There was wine enough in the Miro cellar to last another generation, and it was normal routine to have sherry and biscuits served in the library on afternoons when Miro was home. As a rule Doutreleau looked forward to it; his well filled figure and declining years responded gratefully to Old-World hospitality, and he knew good wine. But on this occasion he showed less than his usual satisfaction, and a hesitation that was rare with him. When Andres had filled two glasses, Doutreleau merely raised his glass and set it down untasted.

"What is new, François? Have you seen the papers?"

"Andres, I have distressing news for you. Be a brave man, and prepare yourself."

Doutreleau swallowed his wine at a gulp then. He had crossed the Rubicon.

"I trust it is not distressing to yourself, François. If it concerns me alone I shall find a way to bear it."

"It concerns us all. Andres—Doctor Beal has been to see me."

"I can well imagine your distress! The man has bored me with his platitudes for thirty years! Has he said you are too fat? I disagree with him. Take courage, François, and be comfortable. I am lean, and I assure you it has disadvantages."

"Andres, he has told me what he had not the courage to tell you."

"Pusillanimity! However—I myself have often confessed to you, François, sins that I would detest to have to tell the world."

"He spoke of you, Andres."

"And that distressed you, François! Take some more sherry. Choose a livelier subject for discussion next time!"

He understood there was genuinely bad news coming, and he prepared to meet it as he would meet death, or any other evil, proudly—conceding it no right to disturb his outer dignity.

"Andres, he has told me you have not long to live."

Not a flinch. Not a tremor of the steady eyelids. Not a moment's relaxation of the smile; rather it increased, and grew kindlier.

"So you were distressed to hear that of me, my friend? I am grateful for the compliment. Did Beal in his omniscience set the date of termination of my mortal activities?"

"He gives you a few months, Andres. Possibly a year."

"I hope he doesn't think I suspect him of malpractice! Assure him, I am convinced he has done his best!"

"Andres, I admire your courage. But to Jacqueline—to your household and dependents—to the parish—to myself—this is disaster. Won't you promise me to do all in your power to remain with us as long as possible? Won't you obey Beal? Won't you let him call in specialists? I want your promise, Andres, as friend to friend."

For a full minute Miro did not answer. When he spoke at last his voice was normal, suggesting no echo of battles going on within him.

"I would prefer to exact a promise from you first, François."

"Name it, my friend. If it is anything permissible—"

"Oh, none of the deadly sins! Promise to keep this news a secret, and to impress on Beal the same obligation."

"For myself, of course, I promise. But Beal will want to call in the specialists, and—"

"Let Beal be answerable for their silence. Impress that on him."

"Then you will see the specialists?"

"On that condition, yes. But not in this house, or there would be talk about it. Let Beal arrange for me to visit them."

François Doutreleau rose, turning his back to Miro, and then, still keeping his face averted, went behind Miro's chair, where he laid his hand on the iron-gray head that he had blessed so often, but never before so fervently.

"Brother—my friend—" he began, but his voice choked and he could not trust himself to speak.

Miro reached upward for the fat hand and drew it down to the chair-arm.

"I am proud of our friendship, François, although I am unworthy of it," he said in a steady voice; but he did not look up at the priest. "We shall be making an indecorous exhibition of ourselves unless we're careful. Would you care to leave me for a while to think this out alone? Suppose you take dinner with us? After dinner we can talk again."

Doutreleau walked to the door, saying a prayer under his breath, and Miro watched him, still smiling,—until the priest turned at the door.

"You will dine with us tonight then, François?"

Doutreleau nodded, for he could not trust himself to speak, and left the room.

Then, with no witnesses, Don Andres Miro sat at bay, looking death and its full consequences in the eyes. Little by little it dawned on him what his death would mean to Jacqueline. He had given so much thought to caring for her that his mind refused at first to readjust itself, and for a while he still thought of her as his ward, his heart's darling, whose destiny was in his keeping.

So this was the end of his plans! It might need years to engage the best legal talent in the land and force through the courts a new trust deed that should settle the estates on Jacqueline! If Beal was right, in a year at most the gum shoe-maker would be in possession, and Jacqueline at the mercy of the world and Isabella, with a few paltry thousands in cash to make her an even choicer prey for wolves.

He had raised her in exquisite luxury, and his death now would plunge her helpless and unprotected into the world he had prevented her from understanding!

What had he taught her, except gentleness and goodness? Nothing— unless pride, that would make her suffer in silence. He supposed that Consuelo perhaps might have told her things that a mother usually tells a young girl, but he rather doubted it, he had said nothing to Consuelo about that, and she was not given to taking liberties.

Haggard and worn—older than he had ever seemed—he leaned back in the chair and faced the facts—then suddenly grew resolute again. He was a Miro. He had months to live! The fire returned into his eye—the Miro heritage—the stubbornly resourceful Miro spirit that had never confessed defeat, nor ever yielded to a lesser force than Providence. Had he wronged Jacqueline? Then he had will to set the matter right, and time in which to think.

He thanked God that he saw the wrong before it was altogether too late. He was ready to flinch from nothing. Somehow, by some means, Jacqueline should not be loser by his guardianship; he, Andrew Miro, would attend to that, and then die cheerfully.

But how? Isabella could be absolutely counted on to thwart whatever plans he might make; he could not take Isabella into confidence. He could provide a moderate sum of money out of cash in hand, and deliver it to a trustee, to be paid to Jacqueline after his death; but the income from it would be no more than a pittance, and Jacqueline would be almost as unprotected as before. Nevertheless; that was something nothing like enough, but he would do that first.

He could make good provision for Consuelo, on condition that she keep watch over Jacqueline. But Consuelo's influence would wane as Jacqueline grew older, and, besides, he could hardly expect a spirited girl to submit forever to the dictates of an old nurse. To an extent, too, that would imply indignity to Jacqueline.

She was worthy of dignity—fitted by breeding and character to be heiress of the Miro fortune and estates. Yet he could not make her that, unless—unless—

There came another, new light in his eyes. He sat bolt-upright— smiled. The invisible, long rapier again. He hardly resembled a sick man, but a great adventurer, when the library door opened and Donna Isabella looked in, even more sourly than her wont. He rose with his usual courtesy to greet her.

"No wonder this house lacks discipline and the servants give themselves airs!" she grumbled.

"Surely nothing has displeased you, Isabella!"

"Something seems to have pleased you!" she retorted. "It will be dinner time in ten minutes, Andres, and you sit there grinning to yourself like a lunatic. How can you expect a well ordered household, when the master is late for his meals? Is it fair to me!"

Don Andres smiled without a visible trace of sarcasm, and bowed to her cavalierly as he left the room.

Donna Isabella nodded after him, thin lipped and exasperated. She would have liked him much better if he had turned on her and shown ill-temper.

"No disobedience! No insubordination! No indignities to any one!"

Consuelo went about her duties with those all too definite limitations humming in her head. All morning long Donna Isabella invented aggravating tasks, as if with the deliberate intention to force rebellion. All her efforts were unsatisfying; weariness was dubbed unwillingness; silent endurance was the sulks; a breathless answer was impertinence.

And it neared noon. Jack Calhoun was coming. Consuelo had made up her mind to get that letter from Jack Calhoun and to take it straight in to Don Andres. There would be no insubordination about that. Don Andres thereafter could take any course he pleased about it, and surely not even Donna Isabella could accuse her of remissness or intrigue.

But the worst of it was that Donna Isabella had a chair set in the patio, not far from the front hall, whence she could oversee everything, and Consuelo could think of no excuse for getting between her and the front door.

At last in desperation she suggested putting fresh flowers in the drawing- room.

"Always some excuse for being lazy!" snorted Donna Isabella. "Go and change the curtains on the bedroom windows."

No disobedience! No insubordination! But what were the Blessed Virgin and the saints all doing? Consuelo, with aching thighs, mounted the stairs to the balcony, and from one of the bedroom windows watched Jack Calhoun come cavaliering in to pay his compliments. She was not surprised that Donna Isabella should receive him courteously; Zeke had already disgorged his several versions of the scene at the convent gate, and Donna Isabella was no fool, to begin by snubbing a man who might help her to be rid of Jacqueline; she invited young Calhoun to sit beside her. Consuelo saw him glance repeatedly to right and left, and knew what he was looking for, but she could not make him see her at the bedroom window, though she prayed to at least a dozen saints to make him look upward, instead of around.

And, as Consuelo had admitted to herself, young Jack Calhoun had brains.

He was a man of his word, of course, but he had not promised to say nothing to Donna Isabella. He and Donna Isabella sat considering each other while he made polite inquiries about Miro's health; and he made a much better guess at her character than he had done at Consuelo's. In turn Donna Isabella summed him up perfectly. He was the necessary man headstrong, handsome, with a fortune not yet squandered.

"Don Andres is not well enough to see you. Have you any particular message for him?" she asked; and something in her bright eyes suggested expectation. He did not hesitate.

"Is he too ill for me to talk to him about Miss Jacqueline?"

"You may talk to me."

He proved a fluent talker, without convincing Donna Isabella in the least. But jealousy will hesitate no more than passion does, to gain its end.

"What chance have I?" he asked her finally.

"None, if you go to Don Andres and ask him."

"I am asking you."

"That is different. You say that she reciprocates your feelings?"

"My God! I believe so. Donna Isabella, I can see her eyes now— innocent and pure and wonderful! I said good-by to her at the convent gate. I kissed her hand.

And she stood watching me as I went, with her eyes full of love—My God! Donna Isabella, I would go through fire for Jacqueline! Her eyes haunt me!"

"Consuelo, of course, permitted you to talk with her?"

For a second his eyes met Donna Isabella's in a flash of scrutiny as swift as pistol-fire. The Calverly-Calhouns are born quick on the trigger.

"Aha! Yes. She's diplomatic, Consuelo is. I'm told the nuns read love- letters, and that's not decent—no more decent than it would be for me to employ Consuelo with out your knowledge. I have hopes of Consuelo's stocking, however, if you've no absolute objection! Of course, I give you my word I wouldn't put anything into a letter to Jacqueline that shouldn't pass a reasonable censor—but you know what nuns are."

Donna Isabella smiled—a wee bit mischievously, as old ladies may who are asked to forward love-affairs.

"What do you think Don Andres would say, if he heard I ever contemplated permitting anything of the sort?"

"Who cares what he'd say as long as he doesn't know?" Calhoun answered with one of his contagious laughs. "Come now, Donna Isabella, you were young once, and I'll bet you've been in love! Haven't I been frank with you? Aren't you going to lend a pair of surreptitious wings to Cupid? Jack Calhoun's your worshiper for ever more if you'll help him this once!"

"Don Andres would never forgive me."

"No need. He'll never know."

"Have you brought the letter with you?"

He produced it, and Consuelo, watching through the bedroom window, saw it change hands. Donna Isabella sat still for several minutes, turning it over and over in her fingers. Fascinated—unable to wrench her gaze away —Consuelo saw the library door open, and then close again, as if Don Andres had seen, or overheard, and, after deciding to interrupt, had changed his mind.

Donna Isabella heard the movement of the door, and took the hint. The letter went into her bosom. Jack Calhoun received his congé and was shown out by the footman. Donna Isabella went to the drawing-room, which Andres never visited if he could invent excuse for staying away, and five minutes later the footman came in search of Consuelo. On her way across the patio she passed Don Andres, but he gave her no inkling whether he knew what was going on or not. Nevertheless, the sight of him encouraged her.

Donna Isabella, seated in shadow in the drawing-room, kept Consuelo waiting with the sun in her face for several minutes before she condescended to speak at last.

"What do you mean by permitting Mr. Calverly-Calhoun to speak to Miss Jacqueline on her way to the convent?"

Consuelo did not answer. If she had spoken she would have rebelled; she held her tongue by a miracle.

"You have nothing to say? What do you mean by spying through a bedroom window all the time I was talking to Mr. Calverly-Calhoun?"

Absolute silence. No answer was possible, unless Consuelo chose to deny the fact or to be openly insolent. She would do neither. She merely hung on —clung to her faith in Don Andres and stood there, looking almost as miserable as she felt.

"If Don Andres were not so ill, I would report you to him." Donna Isabella paused between her sentences like an inquisitor selecting new implements of torture. "You have been careless and unfaithful. If Don Andres knew—"

Consuelo bit her lip—on the verge of rebellion—or tears, she hardly knew which.

"—but he must not know, for the present. Now you needn't look sullen at me; I am not going to discharge you."

Another pause—another long keen scrutiny. And then:

"I understand that you promised Mr. Calverly-Calhoun to take a letter to Miss Jacqueline."

No answer, but a little jerkily defiant nod. Donna Isabella had a definite purpose behind the morning's course of cruelty; she was demanding tears as evidence of good faith. Better for Consuelo to break down and have done with it!

"If you were not an old and trusted servant I would deal more harshly with you. Are you not ashamed to have so abused the confidence we have always placed in you?"

Donna Isabella was as near the end of her resources now as Consuelo was. Unless Consuelo were humbled, repentant, ashamed, she could not use her. She was growing really angry, but disguised it with an effort, forcing her voice to seem almost kind.

"I should have though that after all these years your affection for Miss Jacqueline would have been more faithful."

That did it! It was anger, but it served. Poor Consuelo burst into tears of indignation—rage—contempt—rebellion; flung herself on her knees and buried her face in an armchair. And Donna Isabella, smiling to herself, put her own interpretation on it all.

"There, there now, Consuelo. If you're sorry, I'll forgive you."

Sorry? Consuelo? She bit the chair to keep brimstone Spanish execration in.

"Come, come, Consuelo. If you're sorry it can possibly be mended. Sit up now and listen to me."

Never—not once in fourteen years—had Donna Isabella spoken half so kindly, and it enraged Consuelo all the more, for she was not an animal, to be first beaten and then tamed. But her natural Spanish shrewdness came to her rescue. Donna Isabella must need something and need it badly. So Consuelo went on sobbing.

"Come now, Consuelo. Sit up and stop crying, and we'll see what can be done."

Tears—idle tears—and rapt attention! Hands over ears, but lots of room between Consuelo's fingers to let words filter through!

"The harm's done now. We must make the best of it. Above all, in his present state of health, we must keep any scandal from Don Andres."

Nothing new about that! So another paroxysm of sobs and moans, interpreted by Donna Isabella as signs of panicky fear of her brother. She permitted herself another of her thin rare smiles.

"Come now, listen to me, Consuelo." She need not have worried. Consuelo was all ears. "You have promised to take the letter. We can't break promises, especially when they're made to people of the standing of Mr. Calverly-Calhoun. Besides, if you don't take the letter, I'm afraid he'll grow impetuous and perhaps do something we would all regret."

An old servant is either a consummate actress, or out of work. Consuelo let herself come slowly out of the weeping spell, consenting to sit on a chair at last, but using tears and handkerchief enough to hide her real emotion. So it was as simple as all that! She could have laughed into the handkerchief! Jack Calhoun had seen the key to Jacqueline and seized it —had he? Had he? Did Donna Isabella really think she could hoodwink an old nurse?

"We can't expect a young girl like Jacqueline not to lose her head over her first love-affair, Consuelo. You may take her the letter, but you must talk to her and warn her not to do anything rash."

More handkerchief. So that was it! She was to take a letter to turn a poor innocent's head, and then put thoughts of rashness into the same young head by preaching against it.

"I am agreeing to this, as much as anything to save your face, Consuelo."

The face went into the handkerchief, red and confused.

"I am going to count on you to be extremely circumspect and tactful."

Quite right. Depend on it! Consuelo nodded vehemently over the handkerchief, both hands holding it tightly to her face.

"You must impress on Miss Jacqueline the absolute necessity for keeping all this from Don Andres. He would be furious, and the shock might kill him."

More nods. Consuelo's black chignon bobbed to and fro like the top-knot on a mechanical mandarin.

"You must contrive to manage this without a scandal. Of course, when Don Andres learns that Miss Jacqueline is in love with Mr. Calhoun, he will give his consent, I suppose. I don't see how he can withhold it after all this clandestine business. So distasteful to him, Consuelo. I'm surprised you didn't think of that before you let it go so far. However, now it's too late to remedy that, we must consider Miss Jacqueline, and not break her heart as well as his. My own heart was broken at a very early age, Consuelo. It was the fault of my parents. They interfered, exactly as Don Andres would be likely to. I could not endure to see Jacqueline's heart broken as mine was, and her whole life blighted."

More tears into the handkerchief; then at last orderly, dutiful, controlled words, cautiously emitted between sobs:

"I will be careful and obedient, Donna Isabella!"

Truthful Consuelo! Careful! She would fight to keep young Calverly- Calhoun away from Jacqueline as she-wolf never fought for cub! Obedient? Watch her! She would take the letter—to the convent! She was jealous of the convent sisters—Yes, she would certainly take the letter.

"When, Donna Isabella?"

"Next week, when Don Andres sends the usual flowers and candy will be time enough."

There were hours, especially during the first few days after her return, when it seemed to Jacqueline that in the convent she had Desmio for her very own even more than when she was under his roof and able to see him constantly. For in the convent there was no Donna Isabella to make acrid comments and to interrupt her day-dreams with bitter fault-finding.

From the Sister Superior down to the darky gardener, they all knew Desmio and loved him. He had left his imprint on the place—windows for instance, in the chapel, and the big bronze bell. And he had promised to come to see her, so there was always that to look forward to, which took the drag out of routine.

Not that the life was irksome; far from it. Don Andres being her guardian and sponsor, Jacqueline received no definitely better treatment than the other girls, except that she was one of the few who had a single bedroom; but there was always an indefinite, and very pleasant suggestion that much was expected of her.

There was no loneliness; almost never a moment's solitude. No girls were allowed to wander alone, or even in pairs, among the trees and well shrubbed acres within the wall, there was always a sister in attendance on every group, whose presence grew to seem as natural as did the absence of anything really reprehensible.

No definitely better treatment; but indefinitely—yes. For it was well understood that Jacqueline was destined for high places, and young girls are at least as shrewd as their elders. There was keen competition to make friends with her, with an eye to the future. The flattery might have turned her head, if she had not been reared by a man who understood and scorned ever subterfuge of that stuff. She undoubtedly lorded it a little.

And she was good to see, in the neat blue convent dress, that could not hide a line of her young figure, or a graceful movement. Dancing was a part of the convent regimen, and there were private lessons by a visiting professional for those whose talent was worth cultivating. At Don Andres' request, Jacqueline had learned old Spanish dances, and since she would rather please him than anything else she could conceive of, she had thrown her heart into it, with the result that she walked as rhythmically as the poets sing; and the rest was sweetness, happiness, health and day-dreams.

For in a convent such as that one, what life may turn out to be after leaving is a dream not quite distinguishable from a pictured heaven. One could make magnificent conjectures, fairy prince or prancing horse included, with the saints to draw from and the stories of the saints to pattern human conduct by.

Jacqueline was not so afraid of Jack Calhoun from within the convent walls. And she did not think of Donna Isabella, lest suggestions of a tail and cloven hoofs should cause embarrassment and lead to irksome penances. The subject of Jack Calhoun leaked out in a recreation hour and rather thrilled her. There were girls who had witnessed the scene in church on Easter Sunday, and of all the rapturously fascinating, irrepressible and newsy themes in a convent, none can hold a candle to a love-affair.

Handsome Jack Calhoun! Young—wealthy, or so reputed—lord of a great plantation, with estates in Cuba, too, good family— horseman—with a reputation for gaiety that had reached young ears well filtered—

"Jacqueline, do tell—what did he say when he gave you the flowers?"

"Jacqueline, dear—does he—does he write to you?"

"Tell us all about it. We're simply crazy to hear!"

But Desmio had taught the art of self-command, and Donna Isabella's jealousy had bitten the teaching home. Jacqueline was not to be surprised into embarrassing admissions. And then Sister Michaela, wanting to know what the talk was all about, approached the group under the trees without seeming to cloak vigilance.

"What is the joke, Jacqueline?"

"I'll tell you if you like."

It was Sister Michaela's business to be told things. Except when she was ringing the convent bell, the chief excuse for her existence was that gift of hers for winning confidence.

She drew Jacqueline aside, and had the whole story of Jack Calhoun in two minutes, asking only three deft questions in a voice that would have coaxed out serpents from the sea, it was so bell-like and sympathetic.

"Have you spoken to him alone?"

"No, Sister Michaela, I don't know why, but he frightens me. I'm not afraid of any of the other men I meet."

"Have you talked about him to any one?"

"Only to Consuelo."

"Does Don Andres know anything of this?"

"No—or I don't think so. Donna Isabella and Consuelo said I mustn't tell him because of his ill-health. I wish I might tell him. Desmio always knows just what to do about everything."

Sister Michaela diagnosed much deeper than the surface, and her words went promptly to the very roots of what she saw:

"Don't take it seriously, Jacqueline. Don't believe too much. Remember this: Other people are not all as tender-hearted, and credulous as you are. They don't always say what they mean or always believe what they pretend to believe. As long as you know your own mind, and are good, you can afford to laugh at any one's unwelcome attentions."

"Consuelo told me to look daggers at him!" laughed Jacqueline.

"You?"

Sister Michaela smiled, and Jacqueline's frown appeared. She rather resented the suggestion that she could not look ferocious if she tried. From under her white bandeau,* Sister Michaela watched the frown as if it were plain writing by a moving finger in a language that she understood.

[* bandeau (French)—a narrow band for the hair.]

"Put not your trust in princes, Jacqueline," she said at last. "Some of them are frauds, and some are weak. Always trust your own intuition. That's the Blessed Virgin's voice that warns you."

Good advice, but not quite comforting. There was something ominous about it, as if Sister Michaela had foreseen dark events. She went off to toll the bell, leaving Jacqueline feeling rather depressed; but perhaps that was intended, since advice that leaves no sting is all the easier forgotten.

"Does she mean Desmio is the prince I should not trust?" Jacqueline wondered, and the frown vanished, as she threw that thought away, dismissed it, scorned it too utterly to waste displeasure on it. But she remembered Sister Michaela's words, and pondered them all through the French lesson, so that she had to be reprimanded for inattention; and if it had not been that a dancing lesson followed that she might have pondered them all day. But there was nothing ponderous or ominous about dancing, and it banished every consideration except high spirits and an appetite. When Sister Michaela tolled the bell for dinner there was nothing in Jacqueline's mood but laughter and a yearning for beef and vegetables; the future, insofar as it existed in her thoughts, was foreshortened to one day ahead, when she would have been back a week and Desmio would probably drive over in the limousine with his usual offering of candy for herself and flowers for the chapel altar.

Desmio! What on earth did she care for princes, as long as he came once a week! But the next day it was Consuelo, and not Desmio, who came. Consuelo was ushered into the great quiet drawing-room, where all guests were received, and was kept waiting there until she could interview the Sister Superior before Jacqueline was sent for. The request in itself was surprising, for Consuelo was well known at the convent and usually Jacqueline was brought straight to her and allowed to talk with her alone for half an hour. Consuelo strutted down the corridor fuming, bobbed her curtsey at the threshold, collapsed into becoming humility, was smiled at and addressed by name, bobbed her curtsey again and laid a sealed envelope on the desk.

"A letter for Miss Jacqueline, please."

A sweet wise smile by way of answer—a little nod of acknowledgment and a glance at the address on the envelope. Nothing incorrect, or even unusual. Letters intended for young ladies in the convent never reach them until after they have been opened and read, but Consuelo might have handed it to any of the sisters; nevertheless, it was very right and proper of Consuelo to take such full precaution. Anything else? Certainly she might see Miss Jacqueline. Another smile from under a snow-white bandeau; then the face disappeared as the head bent forward, and a hand such as Tintoretto painted went on writing, writing with a golden pen. Consuelo bobbed her way out backward, all the steam gone out of her.

Then Jacqueline in the drawing-room in the plain blue dress that Consuelo hated, and with her hair mismanaged scandalously, and Consuelo unaccountably wet-eyed, which led, of course, to instant urgent questions about Desmio. But Desmio had sent kind messages, along with the flowers and a veritable load of chocolates, and was feeling so much better that he hoped to be able to come neat week.

"Then why are you crying, Consuelo?"

"Honey, dear, I don't know—I've done my best for you, that's all. Oh, honey, and you so innocent! And them so bent on—Listen, be still a while and listen!"

Consuelo looked up through the tears at Jacqueline, who was standing beside her with her arm on the chair-back, wondering. The young heart was beating almost as violently as the old one. Every imaginable fear was in the air—the worse—the most unspeakable—that Consuelo might have fallen foul at last of Donna Isabella and have been dismissed.

"Conchita, don't admit a thing! Don't let them trick you into a confession that you've given that Calhoun boy as much as a glimpse of a smile!"

"But I have smiled, Consuelo."