RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

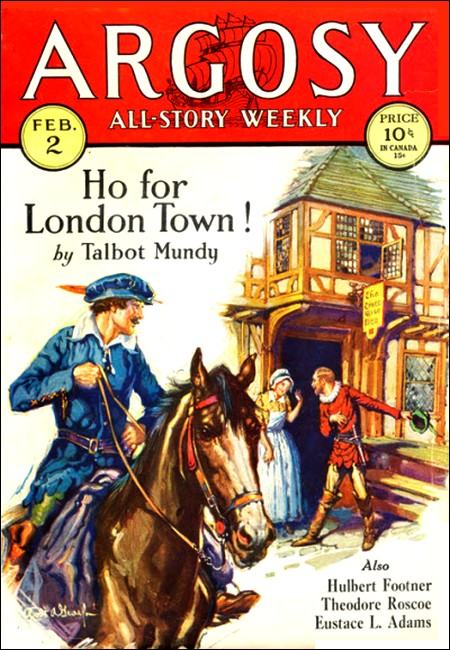

Argosy All-Story, 2 Februay 1919,

with first part of "Ho for London Town!"

How in the year 1585 a certain Master

William Halifax set forth to win

fame, fortune and fair lady;

and how Will Shakespeare pointed the way.

THE manuscript of this story was discovered in the cellar of a house in Bloomsbury, London, in course of demolition. Such learned authorities as have seen the document are unanimous in denying its historical value, on the reasonable ground that its author is otherwise wholly unknown and his statements are at times apparently in conflict with recorded facts. Furthermore, they say, that period of which he writes produced more literary hoaxes than almost any other, and they add, that many of his statements, though not actually contradicted by the files of history, are not susceptible of proof.

The manuscript is therefore hardly sacrosanct, since men of such authority and learning have denied it credit; it has accordingly been edited, its more archaic phrases being rendered into modern English, and for words that have dropped out of common use or whose meaning has changed in the course of centuries, more modern words have been substituted to convey the writer's apparent meaning. Many phrases, also, have been modified or totally omitted out of deference to modern taste—a taste that would have seemed inexplicable in the days of Good Queen Bess.

Due to dampness, rats, and the indifference of the workmen who came on the manuscript, some pages from the beginning and from the end are missing or so damaged as to be undecipherable, but the remainder is clearly written in an upright hand that certainly suggests its author may have been the man of character he represents himself to be.

It begins:

SO I made up my mind I would leave Brownsover for good and all, for it offended me that such a coney-catching louse as Tony Pepperday should own my father's mansion. But I will say this for the chuff: ill-favoured caitiff though he was, he had the gift of self-advancement. He had married first into the gentry, which was marvellous enough; and then he served as bailiff of my father's estate until in the end he possessed the whole of it, and that so legally that none, not even his Grace of Leicester, could deny him right. There was not a horn-book printed that could teach him anything.

But in those days I had so much yet to learn, that now, after a lifetime spent in courts and tented fields and on the sea, and where not else, I am left wondering how so raw a youth as I ever made my way. I was so callow, I expected gratitude, and that from Tony, of all people in the world:

I had risked my father's anger (not a light thing, as they knew who ever gave him cause) by asking his leave to be betrothed to Mildred, Tony's wife's daughter by a former husband, Robert Jackson, who had lost his head and most of his estates befriending the Princess Elizabeth while Mary was Queen. I had brought my father to my view of it, and he a knight, though Tony was no better than a hind until Mildred's mother married him for the sake of protection for her child. Tony had been one of Bonner's men in Bloody Mary's reign, but now he was all for the new religion and the death of Jesuits.*

(* The Bishop of London who was responsible for the burning of many "heretics" in Mary's reign. He died in the Marshalsea prison and was buried at midnight to avoid a hostile demonstration.)<(p>

Tony, you may doubt not, was well pleased to marry the daughter to me for the sake of my position in the county—until my father fell by a violent death and it transpired that Tony had bought up liens on all his land and goods.

And now word reached me through the village barber that the banns might be forbidden, and much mystery about it. But to Tony's house I went, in my second-best suit, on my good roan horse Robin, and I told ham again how I loved his daughter Mildred, and she me. Nor did I forget to jog his memory of how my father had befriended him; and I spoke with such rein on my temper that I said no word at all concerning how he had deprived me of my heritage (since in truth there was little I could say reasonably, my father having incurred great debts that Tony lawfully had bought up).

Had I been a little wiser in the world's ways I might have wasted less breath and have been less astonished. Having all my father's lands, that miserable caitiff coveted my horse, too, knowing that the beast was mine, although he could not prove it. He beshrewed himself to think that anything of value had escaped his clutches. Me and my good name he valued now not at all, so swift is a pick-thank's somersault. First he visited his cellar to drink cordials, for he was naturally timid unless liquor fortified him; and when he came up into the room where he kept his books and papers, wiping his mouth on the back of his hand and stamping on the flags to warm his feet (for it was winter), he began to make too free with the name of Halifax, that but a week ago had been enough to make him doff his cap at mention of it.

"Will Halifax," said he, "you are a worse squibbe and a spendthrift than your father was, although Sir Harry was a brave enough knight, which I doubt you will ever be. I tell you, you shall have no girl of mine, nor any of my money."

I was sitting in a chair my father gave him, looking through a window at the good fat beeves he had acquired by virtue of a lien that he began to enforce the very day my father died. The hobbinoll's audacity so took my breath away that I could hardly answer him.

"I fear me, you will come to no good end," he went on, taking courage of my silence, "and shall I give my daughter to stand weeping at a gallow's-foot?"

Whereat, much wondering that such a coney-catching ban-dog should have bettered his station in life while many an honest gentleman went limping on a broken cause, I decided that patience no longer was seemly:

"If honesty is a cure for sin," said I, "you are like enough to roast in hell-fire, Tony Pepperday, when your time comes!"

I would have walked out there and then to keep my fists from drubbing him, which I had promised Mildred I would not do, even though he should vex me out of countenance. But where he thought a bargain might be had he recked little of hearing truths about himself, and doubtless he believed that all men itched after money as he did. He stayed me.

"I pity your need and will buy your horse," said he. "I will pay you a good price, although I doubt not you will squander it.

But I was not in mind to walk to London or to mince my speech.

"It puzzles me," said I, "that such a long-faced, shamble- smelling miser as yourself could foster a sweet maid like Mildred!

I had looked to get back by marriage part of what you cozened from Sir Harry. You may set that rashness to my youth's account and against it credit me a lesson learned; for by the stomacher of Good Queen Bess, when I have Mildred it shall be without your leave or your endowment! My father Sir Harry always told me gold is not a gentleman, and I perceive it keeps low company!"

With that I left him, honouring him too much with hot words wasted on ears that listened only for the chink of coin. He went hopping in a hurry to the milk-room by the cow-byre, crying to his daughter she should no more see me, and to keep herself within doors.

Not finding her, he followed footprints in the snow around the copse behind the house, until he came on Madge Ambleby the maid- of-all-work. And her tongue was brisker than his. As I mounted my horse in the yard I could hear the two of them hard at it, he swearing she had purposely decoyed him and she bidding him remember his years and behave more seemly. Might an honest wench not go, forsooth, to see that her master's geese were out of reach of foxes, without that old fox of a master risking his ears boxed for pursuing her like a horse after a mare? 'Od's teeth! the frosty morning rang with the clap-clapper of their tongues.

I rode along the hedgerow, where the horses had trodden the mud of the lane and there was no snow left to show a footstep, only cat's-ice in the holes. And when I reached the clump of beeches by the frozen pond where the lane turns into the high road, there was Mildred waiting for me in her new red cloak with its hood drawn up over her hair. She wore the Flemish stockings I had bought for her from Will o' Bruges last fairing time, and she had done on the little gold necklace that had been my mother's—something I had set aside before the sheriff's bailiffs came; and that, if Tony knew of it at all, had irked him little, since it came within his reach in any case.

By the whistling wind that blew across the common and shook the crisp snow from the elms, her hood was not much redder than her lips and cheeks. I lifted her up in front of me, and that which followed fired my blood. I bade her look her last on Tony Pepperday (for we could see him in the distance pegging around the yard with his stick and slamming shed doors, looking for her). I told her she should come with me to London, two of us on one horse. I would make her my lawful wife as soon as might be.

But she set a hand across my mouth to stop such talk. And when she had done twisting at the little new moustache that I had grown to cut a figure with in London, and when I had boasted myself dry of lover's oaths and arguments (for love makes lawyers of us all) she slipped a purse into my hand. But whence she had the money she would not say, only this:

"All's fair in love, Will Halifax! My father cozened yours, and what he doesn't know won't rob sleep. Haste and win a fortune! Ride straight, fight hard, and remember me!"

Forgetfulness was likely to come limping after such a speech in any event, I take it, but I loved her, as I do yet. With her lips on mine I swore to myself not to be faced out of my livelihood by Tony Pepperday—nay, nor by fourtune neither; I would answer her challenge with deeds that should make England know me!

What with my horse Robin feeling the chill wind and kicking, and what with her pressing her fingers against my ribs where I am ticklish, she managed to free herself then, and right bravely she stood, smiling and waving to me, though the tears were like dew on her lashes and she trusted herself no more to speak.

So I rode away, with very fierce determination, thinking of the Dons whom I would beat to their knees and hold for ransom, and of the knighthood that Queen Elizabeth should presently bestow on me (for it was common talk that Queen Bess loved a man of mettle, and I had no doubt that I should bring myself by some means to her notice). But what was passing in Mildred's mind I knew not, neither greatly cared, provided she were true to me, not having learned yet that a woman's wit has several sorts of merit. I loved, but without that disposition to be fore-horse to a kirtle that has robbed some men I know of self-esteem—aye, and of the esteem of others.

I could see her standing there, her red cloak bright against the grey pond ice, until I topped the brow of the hill and paused to wave to her a last time. Then I turned my horse toward Walter Turner's house to get my saddlebags.

For I had stayed with Walter Turner since my father's death, which was how it happened that I had a good new suit and new hat preserved from the sheriffs men. Walter had begged the loan of them to wear at his cousin's wedding, and by the same good stroke of fortune he had borrowed my horse Robin. Whether the sheriff's men ever heard of it and looked the other way from loving- kindness, or whether they really believed my horse and German suit and hat were Walter's, is something that the Lord God will determine at the Judgement Seat.

There was another reason, besides his being beholden to me, why Walter Turner was a comfortable friend to leave behind, he being recently betrothed to Ann Guest and much enamoured of the girl as well as eager to pocket the rents that should come with her. It was with no small measure of confidence that I commended Mildred to his and to his sister's care, bidding them pass the time of day with her whenever an occasion offered and to lend her their encouragement against old Tony Pepperday's attempts to marry her to someone else.

With good cheer then, when they had buckled on my saddlebags, and Kate, at risk of greasing my best suit, had stuffed in two fat capons along with other eatables, I turned Robin's head toward London, malting no more speed (because the road was long) than was enough to keep the frost out of his joints and mine.

I felt as full of spirits as the good horse capering under me though, reckoning Mildred's purse which I was minded to keep against dire extremity, I had little enough money. "Naked and without a purse I came into the world," thought I, "and that journey may have been longer than this one, though I don't remember it. It shall go hard if I don't win fortune, and the Queen herself shall have to use her very sceptre to prevent me." (But I little knew the strength of Queen Elizabeth in those days, nor would I have believed her courage, nor the skill with which she reined men to her uses.)

I had a good short English sword, which my father began to teach me how to use before I knew my alphabet, and, notwithstanding I had heard the new Italian long-swords were all the rage in London, I had no doubt of giving a handsome account of myself in that particular.

Nor did I lack for schooling, as so many did who went to seek their fortunes at the court. We have a school at Rugby, near Brownsover, which Master Laurence Sheriff, the alderman, endowed before he died. And if the frequent soreness of my hams from caning is the measure of my scholarship, then few youths ever set forth better versed in Latin, to say nothing of French and Spanish that had cost me no pain, having learned them from my father and from the servants whom he had brought with him from foreign parts and kept until they died of old age and too much eating.

Circumstances had unfortunately robbed me of the favour of the Earl of Leicester, who was Lord-Lieutenant of our county and a great man at court, but I thought there could be few things more likely than that I should find service in some nobleman's retinue. It was common talk, too, that the Queen welcomed young men of good looks and breeding, to serve as pages, and I knew I did not lack for manners or appearance. Did not Mildred love me? That should put conceit in any man.

It suited me to be alone that morning; for a good horse snorting at the frosty air, his ears a-twitch to catch the roadside sounds, is better company than any chattering companion when a man sets forth to win his spurs and dreams of all the vanquishments he will accomplish. If a dream had only substance in it I was general of armies, admiral of fleets, and Mister Secretary Halifax, Lord Councillor of Queen Elizabeth, that minute!

So it sorrily displeased me when I saw a horseman resting at the signpost where the road turns in from Stratford. He had saddlebags like mine, and a bulging roll of blankets that looked as if a farmer's wife had packed them full of all the stuff she had for market. He was dressed in good stout woollen cloth, and wore an old felt hat with a goose-wing feather in it, so I took him for a farmer on his way to London.

I did not hail him and he let me ride abreast before he spoke, swinging himself into the saddle and smiling whimsically, as I noticed with the corner of my eye. I had a better horse than his, and I was better dressed. He had no right to speak to me.

"Well met, Sir Venturer!" quoth he. "I ride the same road. Though your horse's rump is comelier, maybe, than mine, 'tis not so comely that I yearn to see it all the way to London!"

It was his voice that pleased. It softened the edge of impudence. He was rather a swarthy fellow with a little chin- beard and upturned moustachios, much shorter than myself, but of the same age. He had brown eyes, wondrous dark and mocking, with a sort of sadness brooding in their depths.

I yielded room beside me and he drew abreast, gnawing a red apple. Presently he drew another from his saddlebag and offered it. Not willing to be churlish on a merry morning I rubbed the apple on my sleeve and bit deep. There was a worm in it. I showed him and he laughed.

"What, again?" said he. "There is a canker at the heart of all things. God made apples, but the devil used one to tempt Adam. Adam ate it, and the worms ate him. Which had the best of it, God or worm? Or did God win, who made the worm, so to win whichever way the die falls?"

I had no answer ready, being neither Puritan nor papist, but a man of sense, moreover, well on guard against such dangerous talk with strangers; for the land was full of Jesuits and of spies out watching for them, so that far too many honest men were rotting in the prisons for a word let fall by way of hasty jest. I asked his name instead, and whence he was.

"Will Shakespeare," he said, "of Stratford."

Then I placed him in memory. He was the lad who had married Ann Hathaway, a woman older than himself, in such haste that there was talk of it on all the countryside. Some said he had been made to marry her, but I doubted that tale. He was used to being whipped and stocked, for killing deer and for writing saucy doggerel, which sort of man is neither easy to compel nor usually reckoned a good catch. He could have run away, there being nothing to prevent since his father had come to poverty in old age, after being alderman. If what I had heard was true, his home, like mine, had been sold for debt, and there was no more to keep him in Stratford than me in Brownsover.

I took another view of the Ann Hathaway affair, the more so as I looked into the fellow's eyes. He was a man such as women throw their hearts at and go any lengths to snare—a witty-wise, good-looking fellow with a devil-may-care spirit on occasion and a way of mocking at himself that gave the clue to catching him into the hands of any wench whose reputation was worth gossip. Ann Hathaway had tempted him, I did not doubt, and had blamed him for it afterwards; and he, with a mixture of self-mockery and dignity, had put his head into the noose to make her an honest woman.

But though I had a feeling for a fellow in adversity I did not care to condescend to him too much.

"Stratford," I said, "is but a village by the Avon, where the middens stink in mid-street and the plague kills elders faster than the brats are born. No wonder you should leave the place!"

My words offended him. If I owned Stratford I would trade the whole place for a hundred rods of Brownsover, but I liked the fellow nonetheless for being angry. Good dogs love old kennels, though they stink. A good man boasts his township, even if the pigs lie ham-deep in the main street mud.

"From which Elysium are you?" he asked. "Do the dungheaps smell o' roses where you come from? I can see your horse drops much like any other animal."

I told him, Brownsover. He laughed.

"None ever heard of Brownsover," said he, "until they started Rugby School—and such a poor school, and poor scholars, that a pair of barns was reckoned good enough. In Stratford we use the Town Hall—all the upper story."

"Aye," I answered, "where the beadle can better observe you, lest you go a-poaching sooner than learn your conjugations."

So we bickered for a while in mutual disparagement, each, cock-a-doodle-do-ing his own dunghill, and not either of us offering his scholarship in proof. And in truth I was afraid to do | that, having absorbed the most part of my schooling from a peeled ash sapling, which is excellent for horsemanship, making the roughest saddle easy, but not sweetening irregular Greek: verbs.

But by noon we were friends and sat together on a rail beside: the road to feed our horses and ourselves. So better was my capon than the venison he carried that I could not help but offer him a drumstick; and when he had made short work of that I broke off a wing for him, whereafter we slaked our thirst with icy water from a nearby brook and by and by we grew so friendly that when we reached a tavern called "King Harry's Head" we had to stop to pledge each other in canary wine. Then on, again, as chattersome as wenches at a maying.

We told each other all there was to know about ourselves. His wife Ann, so he said, unlike good wine, was hardly mellowing with age. She loved to sit in church o' Sundays and quote sermons at him all the week, so that he knew by heart so many sins as it would take a lifetime to commit the half of them. For himself, he better loved to rest him merry and to write such airy nothings as imagination conjured into words, whereas Ann tolerated no such nonsense, as she called it, in the house, but used his scribbled sheets to light the oven fire.

"And it's bad bread that she bakes, Will." We already called each other Will and Will. "Bread as much resembling belly-comfort as the unoathed, funless Heaven that she prates about resembles good cheer for a hospitable soul."

He had a thought go into the butcher-trade, having learned that, for he had to kill his father's calves when the family fortune dwindled, and not knowing much else except how to shoot deer and dress the venison, which he confessed he could do far better than his wife could cook the meat, she burning it, he said, as if the hell she prated of were something near at hand.

But he was gentle-minded and not hankering for the Smithfield shambles.

"Ludd knows, Will," he said, "it is a pity we must kill the poor brutes with pleading eyes that look at us so soft and melancholy."

I thought him likelier to make a parson than a butcher, but I learned a little more of him that evening and changed my mind about the parsonage. We bedded at the "Three Wise Men," a roadside tavern, and a good one, kept by a one-legged rogue named Bellamy, who had owned a sixty-fourth share of a privateer that fell in with a Spanisher from the Americas, all loaded down with silver bars. So, though he lost a leg, he sold it for a high price, and he had married as buxom a wench as ever sliced a loaf against her bosom. She was all the way from Bristol and, having neither kith nor kin to weep with when old salty timber-toe was in his cups, she laughed instead with any merry traveller who came along. Both I and Will were merry, being young.

So while we stalled our horses and scraped the mud from them (to save a hostler's fee next morning) I saw fit to drop a hint or two to friend Will. For it is a strange thing how a lover's loyalty can make him jealous of another's peccadillos. I have learned to rest well satisfied if my own behaviour offends me not too much, and other men's incontinencies vex me not at all. But I was young in those days.

"Will," I said, "our hostess hath a hospitable eye and you, a married man, must of necessity act seemly, being not so far from home but that a rumour might reach Stratford."

For a while he scraped his horse's fetlocks, whistling to himself to keep the dust out of his teeth.

"Women," he answered presently, "resemble rhymes and tunes in this: the easiest to catch are they that, as it were, impatronize themselves until they seem more inescapable than empyreal destiny. Those are the sort that lose their zest, and like the ale left in a tankard over-night they bear not later scrutiny. When yesterday's sour ale has dulled the drinker's wit doth he not charge his belly all anew with vintage to restore the vibrance of his brain. 'Tis even as with tunes: the dull ones so obsess the memory that not the very lark's excited welcome to the spring can drive their limping measures out of mind. Shall a man steep himself in merry music to forget care—in the joy of living and he love not death?"

"Then shrewish wives," said I, "excuse incontinence?"

"Excuse," said Will, "is coward's courage. He who makes excuse defends himself against another's conscience like a school-boy stuffing pigskin in his breeches to defeat a teacher's cane. To be in love with wisdom is to follow precept; but to love and yet be wise is to invade the province of the angels, which is trespass. Foolishness and love go hand-in-hand to many a hey-day that the dry-wise never know. Did you not tell me on the road, in words as red and white as roses, of a maid named Mildred? Do her grey eyes fade so soon from memory?"

I was offended, so I combed my horse's tail a while, with an eye to his heels, he not loving to be handled when his nose was in the manger.

"Which has the better," Will asked presently, "the gallant with a rosebud out of reach, or he who treads a blown bloom underfoot?"

Whereat he went into the inn ahead of me, and when I reached the hearthside he was seated in the best chair, with a mug of sack beside him, and the woman on her knees at the fire making toast, which any of the kitchen wenches might have done—and done better, for she burned it, what with listening to Will and looking sideways at him.

I had lingered at the pump to wash myself and polish up my brass spurs, sticking the pheasant-feather in my new hat at an angle that matched better with my smart moustachios. But Will had let the woman wipe the road-muck from his boots before she made the toast, and presently she sat on the arm of the chair to stitch his sleeve where he had torn it, giving me her back to gaze on.

'Od's blood, how the fellow talked! I soon began to change my mind about Ann Hathaway: though she had been as virginal inclined as Queen Elizabeth she must have lost her head and heart to him. I thought of old King Solomon, who had a thousand wives, and understood how he conducted all that courtship!

Will could make a verse offhanded when the sparks flew upward from a faggot; when the gusty wind blew smoke out of the chimney- mouth he likened that to dead men's spirits coming back for one last look at comfortable earth before they soared amid the melancholy loneliness of starry space; he likened scraping muddy boots to the forgiving care of angels probing underneath men's scabby sins to find the virtue that redeems them.

She was as drunk with honeyed words ere long as Titus Bellamy, her man was drunk with spiced canary in the inner room. Bellamy's brain remembered feats of daring he had heard of, and, if anyone believed him, he had sent more Dons to roast in hell-flame than the Smithfleld butchers had killed Christmas beeves since the Lord Harry himself was King of England. If he believed himself he should have slept ill, thinking of his end.

When Will and I had supped, Dame Bellamy attending on us and loading a board before the hearth with fare that would have watered the mouth of a prince to smell of it—cold pigeon pie, there was, with eggs, and fat ham, and a chine of pork, and sausage, and honied apple dumplings soused in cream, and Leicester cheese, and pickles—I forget what else—I went into the back room to sit facing Bellamy before the fire to listen to him.

I would rather have listened to Will, but I was envious, and Mistress Bellamy thought nothing of my new moustachios. Nor had I any gift of speech to take the wind out of Will Shakespeare's sail and keep him from the port he had in mind. I would have liked the woman's flattery, and I would have liked the smug feeling of virtue to be won, perhaps, by skating over thin ice. But I was young; and if we came into the world with as much good sense as living teaches us, this world would be another kind of place, or so I think.

Besides, good Will was even then fumbling at the doorway of her virtue where she offered such warm welcome to the stranger at her gate.

Will Halifax becomes the owner of a "gimcrack"

in a red box and Will Shakespeare acquires a mare.

THAT whole night long I listened to Titus Bellamy. He

grew more talkative the more he drank. And so I have no knowledge

of what Will did, not though vinegary Ann should hale me before

judges for a questioning.

In addition to me and Bellamy there were five men on the settles on either side of the fire in that back room, and by midnight four of them were snoring, doubtless having heard his tales an hundred times but preferring to sleep before the fire because it cost less than a bed.

He who sat beside me was a leathery-faced and leather- jacketed, sharp-nosed fellow with a pair of merry blue eyes, Jeremy Crutch by name, whom I remembered to have seen at Coventry Assizes, where they tried him for some felony and let him go for lack of evidence. I knew his reputation well. Some said he was a Jesuit, although my father had gone bail for him when he was charged at Coventry, which I think he would never have done had he thought him a Jesuit—rash though my father sometimes was, and ready to befriend even masterless men.

That had been the first time that a masterless man found bondsman while awaiting trial in our part of England, and there had been plenty to advise my father that a knight should risk his substance in a worthier cause. Truly enough, if Jeremy had chosen to abscond my father must have fallen into bankruptcy, he being already deep in debt, as I discovered when he died.

However, Jeremy made no bid that night to claim acquaintance on the strength of my father's charity; nor had he the indecency to speak about my father's death, although he must have known the circumstances, which had been a nine days' gossip on all the countryside. He was thoughtful to give no offence, and he drank no more than I did—very sparingly, that is, since I take no pleasure in a next day's ride when half a merry morning goes to drive off fumes of wine.

Only when old Bellamy paused in his talk or lost the thread of reminiscence Jeremy Crutch would break his silence to ask questions—with a by-your-leave or if-your-honour-will-permit to me—to start the old ruffian off again describing doings on the Spanish Main or off the Portugais or on the road to India. For he claimed he had ventured all over the globe.

It was talk to make a young man's blood go galloping if anything but ice were in his veins—tales of strange seas, and the Inquisition, and of gold and silver bars in heaps—of fighting out of sight of land for galleons deep-laden with the plunder of Brazil—of Captain Francis Drake, whom all the world had heard of, and of mermaids and sea-monsters, and of John Hawkins and his traffic in blackamoors stolen from the Portuguese off Africa and sold, as many as lived the voyage out, to merchants in the New World.

No man ever heard more exciting tales than that old timber-toe could reel out through his shaggy beard; and not the half of them were half-true because they lacked, as I discovered later, half the fact—of suffering as well as deed. There were tales, too, of the past when the Lord Harry had beheaded a wife or two to show his independence of the Pope, and the men of Devon had begun to copy his example, privateering against any ship that carried the Pope's blessing.

He told, too, of the days when Mary, our great Queen's sister, wished to take Philip of Spain for husband—as indeed she did eventually, she being a Tudor, who would have her own way, cost what it might; and the men of Devon put to sea to keep Philip out of England, filling him so full of dread (for he is timorous) that he stayed away until the Devon men grew weary and turned to plundering elsewhere, so that Philip dared the voyage at last and married her, to England's misery and shame.

And though Bellamy lied, as having been foremost in all the exploits he recounted, he did no more than magnify himself into the boots of men who stormed over land and ocean, havocking more capably than he could talk. For I met many of those captains in the days to come, yet know not now which was the stormier, Don or English—aye, nor not alone they, but the French and Flemings, Turks, Venetians and Genoese—and a host of others. Under Gloriana men have had to carry bold blades who would leave their mark on memory.

Jeremy Crutch and I sat sleepless, hardly noticing each other, covering the pot-mouths with our hands when the yawning tavern- wench made shift to fill them. But Bellamy drank as a drain takes water and then roused the girl with a sailor's oaths because she nodded in a corner when his mug was empty.

There was word once or twice of a robbery, one Joshua Stiles, a London merchant on his way to Bristol, having yielded up his purse to someone in the dusk, three nights gone; and old Bellamy bragged loudly of the gibbet at a cross-roads nearby, where he swore such miscreants as did on land what honest men might do at sea with God's approval, ought to hang in chains for an example to the others. And he said something of a geegaw or a gimcrack that the merchant prized more highly than his purse, having been sorely grieved to part with it to a thief who would never know its value.

"Master Stiles swore to me," said Bellamy, "that he would rather have that geegaw back than hang the thief, though I forget how he described the thing. It may have been some box for sibbersauces for a woman, or a crucifix perhaps—some bauble. But he's no Papisher, not Joshua Stiles! He's a good, God- fearing, loyal subject of the Queen's most gracious majesty—I heard him say it!—saving, I don't doubt, when her excisemen stick their pimply noses in among the bales."

He would have talked more of the gimcrack, only that Jeremy turned him off to boasting of the loot he had seen in strange ports. Towards morning he grew stupid in his cups and returned to the gimcrack and the tale of the robbery, but then Jeremy got up and left us and by that time it behoved me to go out and feed the horses.

There was a heavy frost and thick white fog, so I found a lantern first and trimmed the wick before malting my way to the stables; and Jeremy, who seemed to know his way too well to need a lantern, rode off like a spectre as I crossed the stable-yard, none giving him God-speed nor he so much as whistling. He wore a hood like a friar's drawn up over his bead. The mare he rode was shrouded in the fog, but she looked like a beauty picking up her feet over the mixen.

It was warm within the stable, so, I took my time, and what with watering and feeding both the horses and repacking my two saddlebags, the cocks were crowing when I came out and there was a right goodly smell of eggs and bacon frying. I was wondering what all that good fare would be like to cost us when Will Shakespeare put his head through the kitchen door and catching sight of me came out to meet me. Whereat I told him what was in my mind about the reckoning.

"I have paid the shot for both of us," he answered, with that merry-winsome smile of his.

I demurred, well knowing he had little money in his purse and not yet realizing how any empty poke can sharpen wit. Will took my arm and answered:

"Study to live courteously, rendering to Caesar what is Caesar's, but to them whose hearts are golden seek to add no gilt, lest Satan mock thee! Vulgar and immodest jangle-bags are they who flout such trash as money in the face of kindness! Only they who know no other measure should be paid in minted money, that an hostler spits on or a toss-pot flings into the sawdust on a tavern floor! There is such hospitality as only loving-kindness can requite."

We lined our bellies well with eggs and bacon rashers fried by Mistress Bellamy, who bussed us both and thrust good bread and cheese into our saddlebags, beseeching us to come again; though me she urged, I knew, to keep herself in countenance.

She stood and watched us ride into the fog until we turned the corner of the road, her breath uprising like a kettle's, and I, to keep myself from asking questions, looked to my pistol priming, thinking that the night air might have damped it. It was well I did. Dry priming has emboldened more men to preserve themselves than ever bullets slew.

Most of that country was open common, but here and there was a hawthorn hedge seen dimly either side the road, soft-grey under the hoar-frost, with now and then the breath of a group of steers uprising on the far side. Trees loomed now and then like ghosts. There was hardly a sound except the ringing of our horses' hoofs on the frozen highway.

We came before long to a gibbet that was used for signpost where a road turned southward, and from there on, perhaps because the gibbet lent a melancholy hue to thought reminding us how cold it was, we let the beasts trot, cuffing our ears and clapping hands to make the blood flow,* wishing that the struggling sun might suck the mist.

(* Although Harvey is credited with the discovery of the circulation of the blood—which he announced in 1619—there is plenty of evidence, as for instance in Shakespeare's plays, that long before that time the blood was commonly understood to circulate. See Julius Caesar III i and Coriolanus I i.)

And of a sudden my horse shied, so unexpectedly that I was hard put to it to keep in the saddle. I almost unhorsed Will by bumping into him.

A man had come spurring from behind a hayrick set close to the road where there was a wide gap in the hawthorn hedge, and no rail, or else the rail was broken, or perhaps he had removed it. He drew rein nigh on top of us and I could see his pistol- muzzle—that and his mare's head, not much more, for the fog was thick.

"Buy your lives!" he bawled out.

I knew his voice. I recognized his mare's head. I bethought me of dry pistol-priming. Also I was envious of Will for last night's victory, and minded to persuade him there were times and places where my prowess might surpass his.

Priming nerved me, but my sword came first to hand. I was at the fellow, point first, sooner and more sudden than he looked for. He drew trigger and the flash and the report scared Will's ill-humoured horse into the ditch, but the bullet missed me, though I felt the wind of it. The next the fellow knew my point was at his throat and my left hand had his mare's head by the bridle.

Then in turn he knew me. "Halifax!" he muttered.

"Jeremy Crutch," said I, "that name of yours rings ominous! Belike you'll need a pair of crutches if I break your bones! Is this your gratitude for what my father did?"

"Unhand me," he answered, and there was more than disappointment in his voice. He felt shame. "Had I known it was you and your crony you should have passed and never seen me."

I took his sword and, grasping it between thigh and saddle, passed his rein over my arm, not having all that confidence in men's professions that had wrecked my father.

"I expected two of the Earl of Leicester's men," said Jeremy. "Such capons travel well lined."

"All that desperate?" I asked. "You'd better rob the Queen's men. She might send to bid the Lord Lieutenant do his duty, but the Earl would clap a hundred riders after you for saucy interference with his pig-stye cleaner."

He laughed. "Let come a thousand," he retorted. "They should never find me. There is a ship in Plymouth Harbour, ready to weigh for the Spanish Main, and my mother's cousin sold me a place on board and one quarter of a sixty-fourth share, but it took all the money I had. A purse or two, to buy my share of liquor for the ship—"

"You might have sold this mare," I answered, eyeing her. She was a beauty. "Be you minded, Jeremy, to walk to Plymouth?"

"No," said he, "for by the rood I'd rather hang! I'll give you better though."

With that he put his hand inside his leather jacket, squinting down his sharp nose at my sword-point, for I trusted him not at all.

"There was mention of this last night," he said, and pulled out something in a leather pouch, of a size to lie snugly on the flat palm of the hand. "I risked my neck for it," he went on, "and you heard what Titus Bellamy said about its owner putting a high value on it. 'Od's blood, I would liefer have a purse of money, gallow's risk and all! Have it. It has brought me ill- luck. It may serve you better."

I took it, hardly looking, needing one hand for my sword and both eyes for Jeremy's face, although Will Shakespeare had dragged his horse out of the ditch and was standing near. Will had drawn his hanger, but I had my doubts that he could use the weapon half as well as Mistress Bellamy had used a toasting- fork.

"Now let me go," said Jeremy, "and I will make all haste to Plymouth."

But I saw that Will's horse had been lamed by falling in the ditch—a sorry beast, more eager for oats than work, and one that I doubt not had lazied many a league through knowing that Will's compassion was his weakness.

"You are like to miss your ship, Jeremy," said I, "for you have lamed the lazy beast that you shall ride. Get down off the mare and change saddles."

He made a wry face, offering me money rather, so that I knew it was a lie about his wanting to buy liquor for the ship. I quoted to him Will's words concerning knaves who measure kindness by its weight in coin, and then, discovering I lacked Will's gift of making words fit circumstance, I changed my argument:

"If I spare the hangman trouble, as my father already did once in your case," said I, "I think the hangman will hardly thank me, since he needs bread like the rest of us."

Whereat he got down and began to change the crupper buckles, his mare being smaller than Will's sorrel; however, I bade him leave the bridles as they were, his being the better and its bit more suited to the mare's mouth.

Then I took away his powder-flask and bullets, but I let him keep the empty pistol to shoot Dons with on the Spanish Main, assuring him that the Dons would live an hundred years apiece unless he practised to aim straighter. As for his sword, it was more like a butcher's knife than any proper weapon, so I gave that to Will Shakespeare, for use if he should go to sticking beeves in Smithfield.

Then I bade Godspeed to Jeremy, he needing it, or the devil might set the hangman on him after all. And when we had watched him ride away on Will's lame horse, toward the crossroad where the gibbet was, we rode on toward London, I well satisfied with having repaid Will the tavern reckoning. It pleased me mightily, and I began to whistle "Mary Ambree, which was a tune much favoured at the time.

Will said nothing until I piped a false note—something he endured less meekly than the bruise he had from falling in the ditch.

"That's a sharp wind, Will! Save it for the Puritans!" he said then, sucking at his teeth as if he had just bitten a sour gooseberry. "You have made an enemy. Why whistle up the devil with a witch's discord to avenge him?"

"Enemy?" said I. "I spared a rascal, though the law of England would have let kill."

"Leave law to lawyers," he retorted. "Those have made trouble enough without your aid. You shamed a rogue, and he will bear so dark a grudge against you as shall gnaw until he thinks he does God's service by ridding your soul of its body some dark night."

"Then would you have killed him?" I asked.

"He should have had my purse," Will answered. "God knows, there is not much in it—yet enough, maybe, to buy a laissez passer from a thief."

I mocked him at that for a lack-spunk who would spare a louse for fear the louse might call him to account. I said that shame, and plenty of it, was the proper physic for whatever remnant of a soul a cut-purse had.

He answered: "Are we preachers, Will, and ride we two to London to beg benefices, greedy for the burial fees and tithes, proposing to ourselves to live in dread of hell-fire while we prate about a sour-swill Heaven?"

"Give him back the mare then!" I retorted angrily.

"Why, how so?" he answered, smiling. "I am not offended that you took his beast, for faith! he staked it on the play of destiny and lost. But did you wisely when you stripped his self- esteem and left him naked to the frosty winds of conscience, that will freeze a merry fellow's soul until it better fits a caitiff's rind? You might have had the rogue's mare and his goodwill with it."

"Sweeter his spite than his love!" I retorted. "Do you choose your friends among the highwaymen?"

Whereat he told me the old nurse's tale about the fox and sour grapes—a silly enough fable, since a fox eats meat, nor never have I seen the fox that would as much as sniff up-wind for cabbages or any other fruit, were it ripe or out of reach or not.

"All life's a mirror," he went on, his hand upheld as if he were an actor and the whole world watching. (He could mock at angels like a small boy stoning geese and yet I think he seldom spoke but that he felt his words were being written in the Book the Angel of the Judgement keeps.) "The men and women we behold are but ourselves as we ourselves might be, should other influences sway us. Would we change the image? The grimaces that the glass throws back at us are answerable,* patterning their apish twistings to a moment's mood. And as a woman sets a bauble in her hair to grace the poor reflection that she sees, and, smiling at the erstwhile unadorned, beholds her mirror smile again, so all earth changes at a merry fellow's bidding. Look you how you pasture leaps out of a mist and sparkles its responses to the sun! A fair example yields more harvest than a gallows-tree, Will Halifax. The whistling urchins start the birds a-singing in the very shadow of a hawk's wing."

(In the English of the period—capable of answering—obliged to answer.)

Who could answer him? The man had music in his marrow and it flowed forth to a tune that made the hearer dumb, so, whether he were right or wrong, he seemed to have the right of it. He did not rant, as did the strolling players I had seen in Brownsover, when we boys all played truant at the price of caning and helped afterwards to pelt the players out of town. The player who could rave the loudest was the most admired, and the first, too, to be smeared with rotten eggs when the burgesses gave the whole troupe marching orders (as they said, because plays were an offence to morals, but, to tell plain truth, because they took too much money at the door).

But Will spoke honiedly, as if the import of his words were not in need of bellowings and windmill posturings to lend it weight. He spoke as to an universe (yet just as he had talked to Mistress Bellamy), seducing it to share his views by seeming to uncover to, the hearer's mind such thoughts as secretly had lain there.

Nonetheless, he made my vanity shrink small in me, and that is discontenting of a frosty morning when a man rides hoping to win fortune for himself. I drew the little leather package forth that Jeremy Crutch had parted with, and opened it, thinking to change the flow of talk into a shallower channel wherein haply I might hold my own.

Inside the bag there was a small flat box with what I took for golden hinges, though it may be they were brass. The wood was harder than my nail's edge, lacquered with a sort of carmine- coloured glaze as smooth to the feel of a finger as windowglass. There was a knob to press on, causing it to open like an oyster, and within was silk, more yellow than the rarest gold, whereon there lay a little figure of a demon, marvellously wrought of green stone, smooth and soapy to the touch of my hand.

It was a comic gimcrack, making us both laugh, although I thought of witchcraft on the instant. It had the trunk and features of an elephant, and yet the posture of a seated man, withal fat-bellied and seeming to ooze benevolence.* Before he had more than glanced at it Will pulled out his purse and offered to buy the thing.

(* The Hindu god Ganesha.)

Whereat when I had quoted to him in contempt of money his own words, he offered me the mare instead, which led to bantering, he saying that the better of the morning's bargain had not forfeited his right to trade again that day. I told him he should not be reckless, since the catechism teaches frugal living, but he answered that the catechism is the solemn and unlovely censure of the men who wrote it seeking to restrain in others generosity that they had lacked themselves.

I let him hold the thing, he turning it to make the sun's rays glimmer on the green stone, showing cloudy depths in it like shoal-water off the Devon coast in summer, and revealing all its skill of workmanship. He sighed at last and gave it back.

"There, pouch it again, Will," he said, "for I have seen too much."

Thereafter for a while he rode in silence, turning something over in his mind, his forehead bowed, now frowning and now smiling as he moved his lips—in the way, it might be, that his father used to taste ale* at Stratford.

(* Shakespeare's father's first public office was that of ale-taster.)

Presently he spoke as having strained the essence of his thought through judgement's mesh until its flavour suited him. He hardly looked at me. He might have been addressing crowds imagined in his mind and seen with inner eye:

"There is a virtue in a woman's eyes," said he, "that, looking, lures into a lover's soul until, though he be earthy of the earth, he will acquire him wings and soar up in an empyrean of such fiery ambition as shall purge his soul of dross. Yet he may look too long into that mystery, and too much see. Though Daedalus flew safe, incautious Icarus, greedy of attaining, winged into a realm where the increasing fervour of the orb of day o'ercame the very strength that lifted him and he was flung into such seas as swallow all who have not modesty.

"And so, as Homer sang, none other shall accomplish; though the frog-like singers swell themselves in emulation of the bull, they burst, nor leave more reputation than a shrunken bladder and a wind gone back to vacancy the fouler for their use.

"Such skill of handicraft, such mastery of medium and tool he had, who wrought that bauble, that I grow as green with envy as the stone is fashioned. Never envy aided. It is cankerous, ungodly rust that eats imprisoned virtue from a tempered blade, consuming and all viler for the stolen feast. That gimcrack stirs me marvellously, Will, for there was magic in the hand that wrought it such as lifts a veil and lets us glimpse a moment's godliness."

His speech was like an angel's, though I write it lamely. Memory be blamed. He made me set such value on the thing as superstition fastens to an heirloom and my mind went roving amid tales of talismans. I felt that gimcrack was a key to merry fortune.

And in truth, that morning, now the sun had sucked the mist away, was such as I have never seen except in England, with the hoarfrost sparkling and the crisp air breathing life into a man, the hedgerows soft-grey underneath their covering of rime, and all such weather as I fancy, breedeth kings—and men, too, to go earth glorious where jewelled grass in movement caught the sun: sailing forth and flout them in their teeth!

It was a magic morning. We began to sing, we two; for Will's moods were as changeful as our English weather. He could take the baritone and carol that against my booming bass until the horses ambled with a rare will and the frozen blackbirds chirruped back to us.

And he could make a song to any olden tune—such foolishness as lovers sing or nurses put the children off to sleep with, until we wearied of an air and Will set new words to another.

How Halifax and Shakespeare lodged at Roger Tunby's house near Cheapside.

WE slept that night at Oxford, at the Crown Inn, kept by

a merry man named Davenant whose wife, I thought, was as like to

lose her heart to Will as Mistress Bellamy had been. But Davenant

had not been married over-long, so that his wife was foremost in

his mind as yet and there was nothing to arouse Ann Hathaway's

jealousy—not that time.

After supper Will called for my gimcrack to amuse them, and he wove such tales around it as put all the chapbook writers out of countenance. I vow there never was such tongue as Will's, nor such imagination—no, nor such a voice to pluck at heartstrings, conjuring a sudden smile from tragedy and cloaking laughter with the mask of grief, until we knew not whether we should laugh or cry.

And so to bed at midnight, sheeted, nor no extra penny for the laundry, thanks to friend Will's entertainment.

So well we liked the Davenants, and they us, that we would have dallied at Oxford but for the shallowness of our exchequer, which persuaded us to journey on to London in one day, by way of Uxbridge, where it was market-day, and a host of people. There, because all men were in fear of horse-thieves, there being a ready market for stolen horses in Antwerp, we earned enough to pay for the bait for our own mounts by standing guard over about twenty others while their owners did Sunday errands; and by that means there entered a thought into Will's head that served him to good purpose later.

We lingered not long by the triple tree of Tyburn, where felons hung in chains from all three beams and great ravens perched above. There was an inn nearby, with benches from which whoever chose to buy ale at a penny more than custom might watch the hangman do his work.

Will grew gloomy, I remember, at the sight of that grim fruit on Tyburn Tree.

"Heaven looked on," he exclaimed, "nor took their part, nor pitied them!"

And so, nigh sunset, to the house of Roger Tunby, where I made bold to expect such hospitality as oftentimes my father had received from him, and he from us (for it had been my father's wont to entertain such reputable merchants as might come to Warwickshire from London).

Nor were we disappointed of good victuals, though the old chuff put the two of us to sleep in one bed and had us send our horses to a baiting stable, where we must pay the reckoning. But as it transpired later, that was fortunate, although at the time I thought a pox on such a starving tyke of a niggard host.

Old Tunby had been used to buy his wool in Warwickshire, and had made for himself such a name for honest dealing that he had as good as a monopoly without paying fee to the Crown. But growing old, and too fat to endure the journey, he had not been seen in our parts for a year or two, so that I hoped he might not have heard the scandal of my father's death. But London has long ears.

The old man bade me welcome and accepted Will as being friend of mine; but even his apprentices could see the spice of hospitality was lacking and that he no longer thought it a privilege to have a Halifax of Brownsover beneath his roof, but thought the cat now jumped the other way. He made short work of telling me it had been common talk in Paul's, and in all the taverns, these many days, how my father had slain one of the Earl of Leicester's followers and himself had been slain by another.

"And they say, Will Halifax," said he, "that Sir Harry slew his man to silence a witness who might have tipped the scale against him in a lawsuit for recovery of debt."

I wasted no breath on denial, though I knew my father's innocence of such foul motive. It was not his nature to act cowardly, nor had he ever cared enough for money to besmirch his knighthood on account of it. The shoe was on the other foot. The Earl of Leicester had despatched two men to seek a quarrel with him, knowing that my father had been privy to certain doings that it were highly inconvenient should reach the Queen's ears. Nevertheless, I had no proof of that, and he who had slain my father had been sent in great haste by the Earl into the Low Countries. Nor did I know exactly what the secret was that had cost Sir Harry his life.

I said to Roger Tunby while we sat at meat:

"I will clear my father's name in good time, he having given me a good enough one when he caused me to come into this world. And I have his kindness to remember, which shall spur me to the duty that I owe him. Nor will I reckon that debt paid before I make the author of foul rumour eat his words."

The old man screwed his mouth up. He was used to domineering his apprentices and took it ill that I should offer to him in his own house what might sound like a reproof. He drummed his knife- butt on the table-cloth. But the serving-wench mistook that for a summons, and when she came he changed his mind about answering me scurvily.

"More ale, Jane!" he commanded. "Less attention to a guest's good looks than to his comfort, or the 'prentices will take you for a vulgar trullibub! A pox on your curiosity, girl! Remember I am an host, and shame me not! Such slovenly neglect! More ale—more ale! And pour it handsomely! Not too much foam, as if, forsooth, this were a pickpenny roadside tavern! Just enough to fill the nostrils pleasantly with good smell while the palate takes the flavour!"

When the maid had served to turn his temper he addressed me fatherly:

"Will Halifax, you will best let bygones be. My own son Edward thought to merit fortune by being, as it were, the echo of myself, even as you aspire to be your father's echo and to do as he did. My good reputation was to be son Edward's stock-in-trade; my knowledge, his credit on 'change; my accomplishment, his boundary of what was worth the doing. He was so satisfied to be the son of Roger Tunby that my faults, which the Lord knows are more than enough, were as much virtues in his eyes as what small quality I have. He'd sooner be at breaking pates about some 'prentice-talk against me than advance himself by giving rumour manful deeds to bruit abroad. He'd sell what I "'Like father, like son, Edward,' said I, 'is a mare's nest. It's a sucked egg. It's as good as boasting that a man's son is his shadow on the wall. God forfend me from the sin o' blasphemy. The Holy Scripture says the children's teeth shall be set on edge, so that's the way of it and, sinner though I may be, I will not o'er-reach myself to break the Lord's Commandments. Powder-beef and pease-pudden,' said I, 'are more suitabler to make you feel your teeth than the brewis and pancakes you're getting. So to sea you go, and face the wrath o' man and nature for your own good name! My own name's good enough for me,' said I, 'and if I lose it lacking you to cudgel the pates of 'prentices, you may make a new name for yourself!' And to sea I sent him under Master Hezekiah Greene, bidding him bite Spanishers if his teeth should get too sharp on the ship's food for endurance. 'Bite 'em, Edward,' says I, 'in the Lord's name, not mine, and bring portuguese and angels* home with you. I'll add you two for each one, and thereto I'll give you this house o' mine to marry in so soon as men on 'change look envious at me because my son is lustier than theirs!'"

(* Gold coins worth about $17.50 and $1.70.)

I have no doubt but that was good enough advice, but Will Shakespeare spied a hole where he could drive his wit in, so he piped up:

"Marry! Will you add two to every one that Will Halifax brings home? If so, I'll go to sea with him!"

"Is he my son? Are you?" old Tunby answered. "I have made him welcome for his father's sake, and I gave him some good advice for his own. But he is too old for a 'prentice, and I have no doubt he isn't old enough to let the maids alone, on top of being too well born to stomach trade. He must shift for himself. But this I will do. For his father Sir Harry's sake I'll speak a word for him to a master-mariner whose ship lies in the Thames by Greenwich."

Now I knew I should make him my enemy an I said no to that offer; yet I doubted it were wise to say yes, and by the look in Will's eyes I made certain he thought as I did. Old Tunby's offer was too sudden-kind. If he were seeking to get rid of me, as was not impossible, then it might be that he owed my father money, of which, indeed I had long entertained a suspicion, although I had no proof.

So, affecting a gratitude I did not altogether feel, I asked how soon he could arrange the matter. He answered it might need a few days, he not caring to take boat to Greenwich while the ague lingered in his bones, but that he looked to see the ague leave him with the first warm sunshine. Will and I might stay with him meanwhile if we would lend a hand among the 'prentices.

But I had seen men with the ague. If he had it, then I had it, too, and so had my horse Robin. Therefore, I began to feel sure that he hid some matter from me, since a reputable merchant would be hardly like to lie to a guest in his own house concerning such a simple matter unless his mind were on a greater and more complex issue, one lie leading to another.

So I made a show of doubt that a merchant-adventurer would accept my services on board ship without a few score pounds to boot to balance inexperience. He did not mislike that, mistaking it for modesty on my part—a virtue in which he declared too many youths were lacking.

After supper by the fireside he began to drink tobacco (which I thought a filthy habit until later on I met Sir Walter Rawleigh and from admiration of him learned to do the trick myself). When we had talked a while old Tunby's married daughter, Mistress Atkins, with a guard of noisy 'prentices, came from her own house half-a-mile away to pay her duty to him and to find fault with the serving-maids, since Tunby kept no woman in the house to manage them, being not so long a widower that he wished to replace his wife's tongue with another that might clack louder.

(* The Elizabethan term for pipe-smoking.)

After she had finished devilling the wenches, Mistress Atkins sat with us before the fire to do her sewing, deeply curious to learn how Will and I had come and for what foul purpose.

Presently I spoke to her about my Mildred, thinking that a youngish woman with her second child due about May Day might admire a tale of lovers' constancy. But she liked neither me nor my story and read me a shrew's sermon on it, vowing that young men who defied their elders ended by marrying ne'er-do-wells, the more bitterly to regret it the longer they lived.

I wished I had been silent about Mildred, but Will Shakespeare took the scolding merrily enough. He told her of his own wife in Stratford; whereat Mistress Atkins made bold to ask him how many pounds the year Ann had for keeping house the while her husband ruffled it in London.

Will's answer drew her anger as a good dog draws a bear: "Whoso puts," said he, "a burden on a horse should feed him. Should the poor brute haul the wain up heavy hills and feed his owner likewise with the very juices of his strength?"

The mean shrew flew into a passion, storming at her father that he wasted substance entertaining squibbes come begging with their hose patched on their heels. Masterless men, she called us, runagates, who should be haled before a magistrate and smartly whipped back to the parish where we shirked work; vagabonds, who might be spies for all an honest woman knew—Papish Jesuits, mayhap, in league against the Queen's grace, fattening ourselves on English beef in English homes the while we plotted with the Scotch Queen and the French!

In choler I rose from the settle to take my leave, late though the hour was. But Will stood up and nudged me until I caught his eye. There was such mischief there as gave me pause and he was smiling, although as for me the turkey-red went flaming up my temples and I could not speak for the wrath that boiled in me. Will pushed me back into the corner:

"Mistress," he said, "it were better done thus."

He struck an attitude, so sudden that she quailed. I, too, thought he would curse her. Tunby struggled to his feet, but sat down; I think he was not sorry to see his shrew-tongued daughter taken down a peg or two.

And of a sudden Will began to pour forth words that stung and bit like summer horse-flies. They were like a whip's crack. There was steel in them. Laden, they were, with the freight of a curse impending, all the dreadfuller because he never launched it; and his gestures, like a master-swordsman's, terrified by their restraint suggestive of a passion leashed and ready to be loosed, yet held in check.

For a minute—aye, more than a minute—I believed his venomous invective was assailing her; and so thought she, recoiling from him like a souse-wife* in a back-street broil.

(* A woman who pickles pigs' heads and feet.)

But it presently appeared that he was teaching her a better way to void her spleen, not voiding his on her. With subtlety beyond my cunning to detect, when she was browbeat into speechlessness, he passed her by, as floods go rolling by a broken dam, and left her, as it were, behind him wondering to watch him overwhelm all levels lower than herself. We three became the audience, and he the player showing us how virtue triumphs over vice.

And in time he paused—in good time. Subtle gesture changed him. He became the very creature he had overwhelmed with eloquence! He trembled and began to answer—stammered—tried to summon dignity—then turned away, recovering, to cloak his shame beneath a show of anger, coveting a passion that he could not feel, his very venom turned to water by the magic of his former speech. He seemed to try to gather new resources from the empty air, then hung his head and answered—nothing!

Presently he smiled, and seemed to take us into confidence; now he was Will of Stratford, we his hosts.

"All men," he said, "play many parts. And that which we think worthy in us often shows itself weak wretchedness when nobler presences appear. Vainglorious Goliath falls before a David's sling. A David cowers at a weak old man's rebuke. Our chiefest powers glow but in comparison with lesser; in the flame of higher genius they fall like dross into the ashes of our self- contempt—inestimable—ugly—oh, oblivion shall swallow no more proper food than weakness that we thought was strength and self-esteem that we mistook for godliness!"

He changed again. He took his seat, and like a cat before the hearth, drew comfort out of hospitality, contenting others with the spirit he exuded. Then he told us tales, so full of magic and the mystery of interest as kept us wakeful, until midnight saw the fire die low and Mistress Atkins had to beg grace of her father's roof. She sent two 'prentices to warn her husband she would not be home that night, old Tunby bidding the 'prentices tread slyly lest the night-watch catch them and the magistrates impose a penalty next day for being out when honest lads should lie abed.

Of the meeting with Benjamin Berden by chance, and of the opportunity that came of it.

I ROSE at dawn, leaving Will Shakespeare in the bed, and

I was in the street before the 'prentices took down the shutters,

finding my way to Burbage's mews where we had left the horses

overnight. Will meant to follow custom and sell the nag that

carried him to London, and we had heard the day before, along the

road from Uxbridge, how good horses were in fine demand since so

many knights and gentlemen had gone to the Low Countries at their

own costs to help Dutchmen fight the King of Spain.

But what with the purse my Mildred gave me, and Will Shakespeare's impudence having saved us so much tavern expense, I was not feeling so bankrupt after all, and the thought had found lodging in my head that two good nags would make a better showing than one.

So I aroused the drunken hostler, and he, thinking I would pay my reckoning, summoned Burbage from his bed, most scurvily ill- tempered to be called to pocket those few pence. I bade him offer me a price for Will's mare, and what with his mislike of being up so early, and with his thinking I could not afford the charges and would therefore sell the mare cheap, he bid low. Whereat I cried a pox on his Jew's avarice and came away before he could better the offer.

Then I returned to the house and wakened Will, who was a lusty sleeper, and I offered him the same price for the mare that Burbage bid me. Will accepted it without ado, it being nearly twice as much as he had hoped to get for his old sorrel that he started with from Stratford, although much less than the mare was worth. I paid him there and then, he smiling as I counted out the money.

"You will die rich or be hanged poor, one way or the other," he said, pulling on his hose, "but if you always leave your victims richer for the chousing, you will not lack mourners."

I grew half-ashamed of having paid him such a low price, although the mare was in a way part mine, since it was I who had forced the exchange with Jeremy Crutch, but Will read my humour.

"Rest you merry," he adjured me. "Let me not know what the proper price is. In the good enough our true contentment lies. The better, unattained, frets disposition. I am only happy when I see no summits out o' reach, nor no flights of imagination missed."

We ate our breakfast with the 'prentices, Mistress Atkins being gone betimes in great dread that her household might have fallen into sloth for lack of clacking tongue. But ere our meal was done old Roger Tunby came among us in his nightcap, with a great red shawl about his shoulders, to admonish the 'prentices and to bid me help them. He was full of spleen in the forenoons, showing whence his daughter had her sharpness, but methought he snailed and swounded* more than natural, as if he spurred a discontent to covermotives. I was more than ever sure he hoped to keep me occupied until he could send me long leagues out of reach.

(* Snails! and Swounds! were favourite oaths.)<(p>

The while I hesitated how I should avoid him without risking enmity, considering a lie about the horses, or a cousin's cousin to be found, or some such subterfuge, Will Shakespeare stole my privilege, like Jacob robbing Esau. He proposed himself in my place, vowing he could sell two bales of merchandise to my one and declaring I was likelier to quarrel than to lure new custom or retain the old.

Good shopmen, it appeared, were growing scarce, what with the war in Flanders and so many thoughts of our English volunteers going over there to fight the Dons. Our English merchants were harvesting a mint o' money selling good cannon and poor wool cloth to both sides, but they were having to pay high prices for ill-trained shopsters. So old Tunby hesitated, doubting Will and yet remembering the magic of his tongue that certainly might serve in wooing custom. While they argued I went up and mucked on my best suit with the pointed sleeves, made by Fugger of Augsburg.* I did don, too, my new short cloak of blue French velvet.

(* The famous German house of Fugger did a considerable business in ready-made clothing, whereas English woollens were getting a bad reputation abroad.)

When I came down Will was chaffering already with a purchaser of wool. Apparently he understood that trade (and by the rood, I have found little that he does not understand, except how to use weapons and act churlish). The 'prentices, who were sweeping out the kennel* before the shop, were in two minds, whether to listen to Will or to the common cryer, who was serving notice of an execution to be held at noon that day. I made my way to Cheapside unobserved (I thought) by any of them, and for a while I was hard put to it to bear myself with proper arrogance, so entertaining was the scene.

(* A gutter down the middle of the street.)

Adown the middle of Cheapside rode gentry, picking their way through crowds of 'prentices and loiterers of many nations.

There was a constant movement, wondrous pleasing to the eye, enhanced as it was by the colours of men's and women's costumes against the painted woodwork of the houses and the heaps of soiled snow. When I stepped aside to dodge a horseman I was seized by half a dozen 'prentices, who were like to tear my cloak off, so eager they were to drag me into their master's shop and sell me I know not what extravagances at double or treble the market price.

I was irked to think they took me for a country lout, being flattered that I carried myself already with a proper townsman's air, yet it was worth a man's life, almost, to incur their enmity. I saw one instance of their storminess. While I was giving and taking repartee right merrily, to hide my anger and to rid myself of the rogues who picked me for an easy prey, a horseman, spurring in his haste, knocked down a 'prentice.

Instantly there was a cry of "Clubs! Clubs!" The clamour sped up Cheapside until the whole street rang with it. The 'prentices left me, and swarms of others, like angered hornets, surged out of the shop-doors with their cudgels swinging. He on the horse made shift to gallop through their midst and faith, he sent a dozen of them down like ninepins, but he might have spared himself some drubbing had he put another face on it. They dragged him off his horse and cudgelled him until he lay stunned, whereafter they held him under a pump and soused him back to consciousness with his high boots full of water and his fine clothes muddied, mocking him for one of the Spanish ambassador's men and telling him his master, and his master's king to boot, were like to be hanged ere long with the other quartered Jesuits on London Bridge.

Yet they were merry rogues, right eager to be friendly in their own way, not intolerant, but liking not at all stiff manners in a stranger. They who had made a sort of prisoner of me were well contented when I gave them money to buy ale, and when I asked where the house of Joshua Stiles might be they sent one of their number to escort me. He was named Jack Giles—a stocky, bull-necked lad in a yellow jerkin that matched his freckles and a flat green cap that seemed to have been used for many purposes.

The place where Joshua Stiles did business was a great house built of brick, containing offices of more than a dozen merchants, close to the new Exchange that had been built by Sir Thomas Gresham. The house had a yard in its midst, in which scores of messengers and porters, and some sailors, warmed themselves at sea-coal fires that burned in iron pots. The snow, grey and sombre with soot, had been piled up in heaps that did not melt because so little sunshine came into the yard, but the firelight shone on the snow right handsomely.

A pompous jackanapes in livery stood at the entrance-gate and asked my business, seeming to take it ill that I was guided by a city 'prentice and not followed by a servant of my own, nor not on horseback; and while I pondered whether to bestow a largesse on the churl to change his humour I felt my cloak pulled from behind.

Marry, but I did not want to see Will Shakespeare then! There he stood, as pleased to find me as if I owed him money. His old- fashioned country suit looked shabby, and I wanted to ruffle it handsomely, not show myself to an important stranger for the first time in a bumpkin's company. I stepped back to the street to learn what brought him, masking my displeasure.

"Willy," he said, smiling, "Roger Tunby takes it ill that you should leave his house all raw, uncounselled and alone. He fears that you may fall among trim-witted fellows who will spoil you of that finery! He bade me follow you, and, if I would keep his goodwill, not to return without you. Marry! but he set no limit to the venture."

"How so?" I demanded, not exactly comprehending, though I read the mischief in his eyes and by the rood it softened my ill humour.

"Why, as day in search of night, and night of day, let mutual pursuit not cease until we meet in gloaming at our host's door," he retorted.

I could see that he had news for me, but he proposed to tell it in his own way, mocking-my impatience with an air of having all eternity to browse in.

"Let us steal a march on destiny," said he, "and for the moment be the fortune's favourites that hope accredits us. Insane ambition was the bane of Lucifer, but we're not angels, Will. A bird may whistle where a mitred abbot were ashamed to speak. So let imagination pluck that pheasant's feather from your hat and fly for both of us. I'll borrow wings from you. We'll both go looking for Will Halifax—yourself the genius of what he shall be, looking for the runagate that is, to make a man of him—and I, the counsellor, contributing such ill advice as Satan uses to keep homing souls from Heaven!"

It was half an hour before I had the story from him. I had hardly left old Roger Tunby's house that morning, it appeared, before the common carrier drew rein with letters out of Warwickshire that Tunby bore into the closet at the shop's rear with an air of secrecy. That left Will free to exchange a word or two of gossip with the carrier, who told him that one letter was from Tony Pepperday.

Remembering that Tony was my Mildred's lawful guardian who, by unhappy chance and monstrous, misliked me, Will plied the carrier with questions. And it seemed that the carrier, like many other folk, well understood what I knew not at all, that Roger Tunby wanted Mildred for his own son Edward, knowing what a comfortable dowry she should have and being so involved with Tony Pepperday in dealings that might otherwise turn to his disadvantage.

"Quoth the carrier," said Will, "the devil himself would need a long spoon should he sup with either of them."

"Can they marry a couple when one is abroad and the other unwilling?" I asked Will.

"Nay," said he, "but ships come home, and absence has a way of ending in the course of time! As for the maid's unwillingness, they say it is a woman's heritage to change her mind. You are not so puritanical, I take it, that design might forge no scandal for your Mildred's ears?"

For that speech I cursed him—albeit something gently, for I loved the man, although he could think of more ingenious disasters in a moment than the devil might invent in half a lifetime, and he aggravated discontent by watching like a groundling at a play to see the outcome. Yet he was the friendliest observer.

"I have heard," said he, "that this man Joshua Stiles, whom you seek, is after the Spanish fashion, more solemn than wise. Nay, I know no more than rumour—what the 'prentices have told me."

I did not want Will with me when I should meet Stiles, but neither did I wish to lack his friendship, so I thought of a way to be presently rid of him and at the same time to advantage both of us. I bade him bring the horses and to meet me where we stood as soon as might be, saying I would let him ride my roan. (For, I thought, if he should ride the mare again so soon he might forget the change of ownership.)