RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

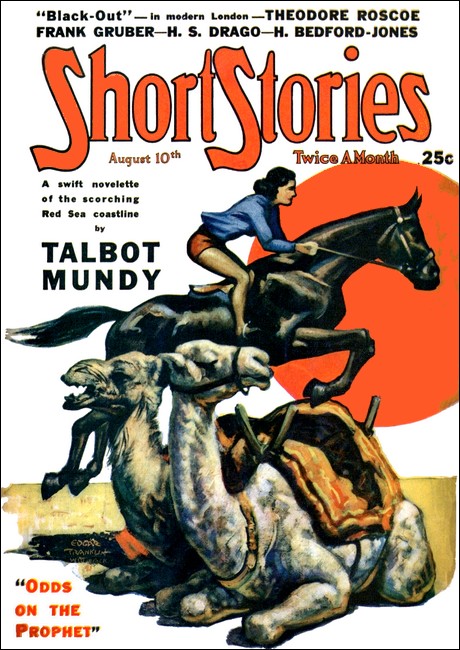

Short Stories, 10 August 1941, with "Odds on the Prophet"

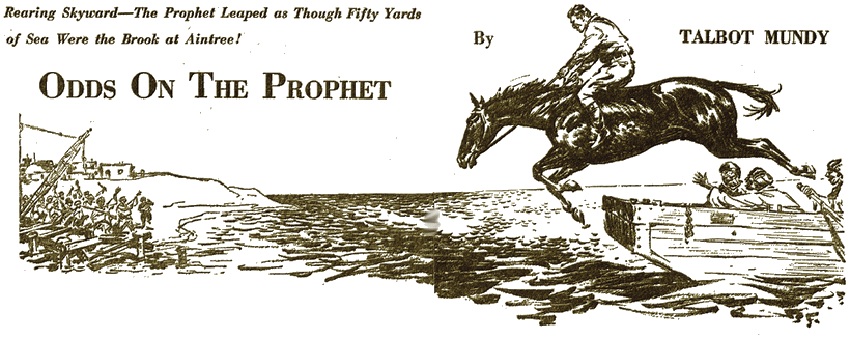

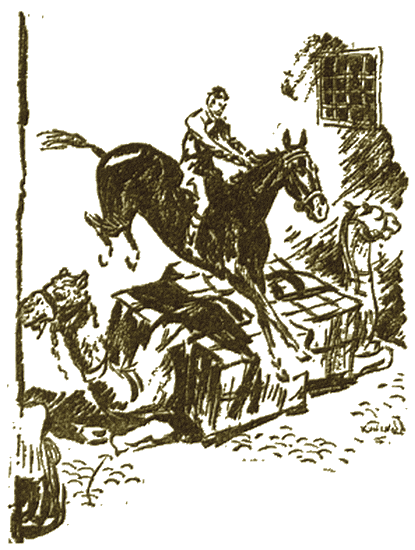

Rearing skyward, The Prophet leaped as though fifty yards of sea were the brook at Aintree!

THE Arabian inhabitants of Zakkum speak of the place as "the Jewel in the Prophet of God's girdle, more lovely than Hodeidah." But there are lots of people who don't admire Hodeidah; and the Lord Mohammed may have had peculiar taste in jewelry. The name Zakkum means "The Hell Tree." There is one tree there, outside the city, beyond the "Gate of the Doomed." It is used for execution purposes; critics from Hodeidah, for instance, are lashed to its barkless dead branches to stare at the hot sky. But Max Rector knew nothing of that, because Roddy Nolan had not yet told him. The advantage of not telling Max before one had to was that Max couldn't air wisdom about things he had never heard of. Roddy was looking for breaks—looking for them in the dark. He didn't want an argument

It was a hot night, even for the Red Sea coastline, where it is always scorching hot, raw-cold or stormy, and its storms come straight from hell. That is why it produces nothing else than fanatics—fanatical camels, customs, fleas and men, to say nothing of women. The moonless, breathless humidity was made more noticeably silent by the intermittent crash of a ground-swell, amid coral reefs and on the fangs of the stinking beach. It made the beach seem nearer than it was. The main street of Zakkum was a diagonal gully between blank white walls that looked like night turned solid. The sky was an ebony vault; the stars swung beneath it like colored electric bulbs. It was tragically stagey. Max had smashed his electric torch when he stepped ashore; there was no light to show where street curs lay; the Arabs stumbled over them and kicked them, cursed and yelping, to perdition, lancing the stuffy silence without relieving it. Hooded, cloaked and arrogantly masculine, but femininely curious, the Arabs walked slowly, those in front continually turning to stare and delaying the others. They had the unselfconscious self-assertiveness of small boys at an accident and the solemnity of mutes at a funeral. They breathed all the available air and that made Max Rector half-hysterical; he was more than a nuisance in that mood; he was dangerous. Roddy Nolan was an old-timer on the Red Sea littoral; he had been a buyer of horses, camels, sheep and goats during the World War. He did not know Zakkum except by reputation, but he did know Arabs. He knew how important it was to make a good impression. He was remembering his Arabic. He asked no questions.

"There!" he exclaimed suddenly. "Didn't I tell you? You can find a Greek wherever the Devil overdid it and forgot to wipe up."

A door in the left-hand wall had opened. Sudden, yellow lamplight splurged on the white wall opposite.

"What the hell good is a Greek?" Max Rector grumbled.

"'When you shake hands with a Greek, count your fingers,' say the Turks. But there's luck where Greeks are—"

"Good luck? Whose?"

"Not always good, but always something doing. Greeks are luck. They're like oil in engine bearings. That's what luck is—oil for opportunity. It's quite unmoral. You take it or leave it."

"Mention engine bearings to me and—"

"Oh, forget em." Roddy had heard enough about Max's troubles. "A Greek," he said, "can live and like it where they'd put an Armenian on the spot for one per cent as much chicanery. This one looks good."

"God, man! You're an optimist!"

"So is he, or he couldn't live here."

"You're bughouse." Max Rector meant that. He always sincerely believed anyone mad who had an idea, or who knew something he didn't know.

THE crowd of Arabs surged into the zone of light, through it, and revealed the Greek standing in his doorway, in an ill-fitting pair of soiled khaki pants and a clean shirt. He had close-clipped black hair and a Mephistophelian mustache. His face was as pock-marked as the surface of the moon, and as yellow, but he was not bad looking. His eyes were soft and liquid with a sort of wistful intelligence. He had a shapely and yet peculiarly vulgar looking nose. Through his open shirt the sweat shone on black hair that curled on his muscular chest and shoulders.

"Evening, gents." He grinned familiarly. "I'm Paulos Kamarajes—John D. Wanamaker-Macy-Altman-Montgomery Ward-Sears Roebuck of Zakkum. Cash and carry. U.S. dollars are as good as any money. What can I do for you?"

The Arabs crowded even closer, uncountable, smelling of leathery sweat, dead fish and burlap; only the nearest faces looked half-real, framed in the deceiving, hoary dignity of flowing head-dress; those that crowded behind and beyond were ghosts that belched, having had their supper, too much coffee, tobacco, no doubt kat, the green leaf that semi-stupefies them so that they believe the Red Sea Coast is civilized and sane.

"Make these creatures scram," Max Rector exploded. That was a real explosion. He was too respectable to swear if he could possibly restrain himself. He shoved two Arabs. They resented it; their slow grins in the yellow light looked deadlier than spoken threats.

"These are sons of the Prophet," said Kamarajes. He said it with emphasis. Evidently some one in the crowd knew enough English to get the gist of an insult. Max could think of nothing complimentary to say, so he piped down, wiping sweat on his silk shirt-sleeve, careful to hit no one with his elbow.

Roddy stated fundamentals: "We want word with the local ruler. I don't know why these people guided us to your place."

"I told them to, as soon as I saw you drop anchor," said Kamarajes. "The local ruler is away from home. These people don't like it that you have brought a guard ashore. They ask, do you think them bad men who might abuse you? I said to them let me be interpreter. They won't abuse you if you leave it to me."

Roddy thought it as well to give the Greek fair warning. It might limit the scope of obliquity. So he answered: "Thank you. I speak Arabic."

"Maybe," said the Greek. "But I know Zakkum. You better tell those sailors off your yacht to go back. They might be abused badly if they don't go. You are safer without them."

It was Max's yacht. They were his men, paid to applaud his whimsies. If Max should explode like a fulminate cap, he might detonate that bo'sun and eight men, and they were likely to start something even more expensive than an engine breakdown. Roddy consulted Max in whispers.

"D'you want us killed or kidnapped?" Max retorted.

"Either trust my judgment or use your own. Suit yourself," said Roddy. He could keep his own temper but not Max's also.

"All right, have it your own way," Max shrugged off the responsibility and shouted: "Bo'sun, take your men back to the beach. If the crowd bothers you there, push off in the boat, but stay close inshore. I'll fire a pistol if I want you. Come then in a hurry."

"Aye, aye, sir." The feet of nine invisible men trudged away into the darkness, like a noise offstage; they suggested an army in the wings.

"Dammit, they'll believe I've met a woman," Max grumbled.

"Perhaps you have," said Kamarajes. "You have come to the right place."

"Oh, are you a madam?" Max asked. He couldn't resist parading his respectability. His was a millionaire morality, contemptuous, swift to nail labels on lies; and a lie was whatever he didn't believe.

BUT the Greek had been insulted by Arab experts; whoever has endured that and survived it, can keep his temper if nothing else. He chuckled. "Come in, gents." He stood aside, speaking to the almost invisible crowd in fluent Arabic. He appeared to have influence; they began drifting away. When he entered he bolted the door behind him. "I have promised by the nine-and-ninety names of Allah, that I will tell them your business," he announced. "That should keep them quiet. How about a drink, gents. There's no ice, but I've Johnny Walker, Haig and Haig, Mattel, Benedictine, Curaçao—"

"Sell 'em?" Max asked, remembering something he had heard about Arab religion and prohibition. He had forgotten his cue to pipe down.

"Swap 'em. Seed pearls—skins—hides—coffee—oyster-shell. This is prohibition country—not Wahabi, mind you—not yet. The Wahabis* are coming, but not yet. You don't get crucified—not yet—for touching liquor. But it's against religion, and sin's expensive—twenty-five or thirty bucks a bottle. This is on the house, though. What's yours? How about a cocktail?"

* The Wahabis, ruled by Ibn Saoud, are a fanatically puritan sect that has already conquered Mecca and is ambitious to bring all Arabia under its grim domination.

"No ice? Scotch for me," said Roddy Nolan. "Let me smell that bottle."

Max saw the point of accepting hospitality. He did his best to be gracious. "Me, too, if that isn't poison."

"Gents," said Kamarajes, "those Arabs are dangerous on a quart of the real thing. Bootleg hootch 'ud make 'em cuckoo; they'd skin me alive. What 'ud make a tough coon sentimental in the Loop, 'ud set these bozos to Kukluxing infidels. I'm an infidel, and so are you, so let's be honest. I sell straight goods."

He glanced around the store with an air of being amused by his own pride. It was a big square room with a stench of hides that came through shutterless windows opening on a courtyard in the rear. There were shelves stacked with the usual trade goods, a huge chest for the liquor, a table, four chairs, an iron cot, and several heaps of cushions on the mat-covered floor. The place was scrupulously clean. A bullet-headed Swahili man-servant leaned in through one of the windows awaiting orders; he was silhouetted, black against a patch of starlit sky. Roddy tossed off a short drink and sat down. Max followed suit, pulling a wry face; he hated anything he felt was forced on him; he was one of those men who enjoy their own bounty and resent other people's.

"Tell him," he said, revealing fat lips as he wiped his yellowish mustache, "if only to convince you you're crazy. Go on, tell him."

"Tell me anything," said Kamarajes "Gents, I'm here to get a living. I don't eat sand. There's no luck in dirty money. But if you've a proposition—"

"We've a horse," said Roddy.

The Greek whistled softly to himself; his luminous, humorous eyes grew slightly narrower. "A horse—here?" he said. "You'd have something rarer now, if you took Irishmen to Chicago or Jews to New York. If you'd any kind of hop, for instance bhang now, I could sell that. I could use a gross of Jew's harps, or a couple of cases of women's make-up, I could pay a fair price for silk socks or wrist-watches, or alarm-clocks. Guns and ammunition, if they're good, are worth their weight in silver. I'll buy old magazines or Victrola records. But a horse—"

"It's a racehorse," said Roddy. "My friend here, Mr. Max Rector, very kindly offered to convey my horse and me to India. The yacht's engines have broken down; the chief engineer doesn't know yet how long repairs may take. The heat and close confinement are not doing the horse any good. I would like to bring him ashore, where he can get exercise. I noticed a scow tied to the jetty; we could use that to get him ashore; and we've plenty of fodder. How about it? Can I get permission and protection from the local shaikh?"

The Greek whistled softly again. "You'd better call him Sultan—Sultan Ayyub. He is touchy. What's it worth to me if I arrange it?"

"Fifty dollars," Max said promptly. His father had made the fortune. Max had increased and preserved it by inheriting prudence along with the dollars.

KAMARAJES concealed emotion by wiping his face with a sweat-cloth. "Have you liquor aboard?" he asked after a moment. "You're not a dry ship, are you? Sell me liquor at cost—all you have—and I'll treat you high, wide and handsome!"

He looked and spoke like a reasonably square shooter, his eyes were alert, not furtive. But Max awaited a nod from Roddy before he answered; he preferred to have someone to blame if necessary. Even so he was ungracious.

"See my steward in the morning. He might spare you a case or two of gin or something."

The Greek rolled himself a cigarette. "You want me to fix it with the Sultan for the horse to come ashore, and be protected, and have exercise—"

"Yes, and get aboard again safely, as soon as the yacht's engines have been repaired," said Roddy.

"I might manage it. Can you sell me ammunition?"

Max scowled. "With a British sloop likely to turn up? I don't want my yacht confiscated, thank you."

The Greek's smile suggested he knew plenty about British sloops, but also plenty about the shirt-fronts of respectability behind which beat the hearts of rogues.

"It wouldn't matter," he said, "if the ammunition don't fit. These guys can make a rifle from an iron bedpost. It's loaded shells they'll pay pearls for."

Max shut his mouth tight and scowled so that his glasses slipped down off his nose.

"Nothing doing. I will make you a present of three cases of gin. I would be breaking the law to sell you liquor."

Kamarajes leaned his weight on his hands on the table, glancing from one man to the other, studying faces. His own face revealed cunning and humor but not much malice—no more than a man needs for business purposes. He seemed to make up his mind to reserve Roddy for a later, subtler and perhaps more profitable effort He addressed himself to Max:

"Sir, I perceive you're a man of principle." He wiped the table with a bartender's sweep of the arm. "You wouldn't wrong man or woman, I can tell that."

"Not if I knew it," Max answered.

Roddy drew a sharp breath as if Max had hurt him. Kamarajes' eyes laughed; not being Max Rector's guest, he gave not a Red Sea damn for Max's smugness.

"I'll bet women get a square deal from you, mister."

"I didn't come here to deal with women," Max retorted. "If this is a bad-house—"

"It's a good-house, but a bad country," said Kamarajes.

"Anyhow, no women." Max had climbed on his high horse and proposed to remain there. It is a long time since the fall of Troy, but very few Greeks have forgotten how to put hollow horses to use. Roddy watched the Greek as if it were a poker game, but the Greek kept his eyes on Max.

"Sure a woman couldn't tempt you, Mister?"

"No," Max answered. "Get that into your head. I'm not interested."

Kamarajes turned his back to get the whiskey bottle from the shelf behind him. Roddy saw him glance at the Swahili servant framed in the open window. The Swahili nodded. Kamarajes faced them again and refilled the glasses.

"Good," he said. "That's all I wanted to know. Let the women alone and you're safe in any country. Here's luck, gents." He emptied his own glass at a gulp.

"Can I count on you," he looked straight at Max, "not to get me in dutch with the Sultan if I let you see a young girl that he keeps his special eye on?"

"Certainly," Max answered.

"Not if she falls for you?"

Max felt and looked flattered; Roddy was the younger man but not nearly so handsome. The Greek showed good sense.

Roddy after all, was a horsey pauper, sportily plucky and all that kind of thing, but unimportant. Affluence does stamp a man; it gives him responsibility and experience. But it stirs cupidity in women. The Greek was quite right. He glanced sideways at Roddy.

"I'd as soon meet a rattlesnake as a woman in this place, but bring her in, if you want to. I don't mind. She shan't get into mischief with us, believe me."

"That's a promise?"

"Yes, for both of us."

Roddy lighted a cigarette. A child could have understood the gesture; but Max was no child; he was born a millionaire; other people had to keep his promises or get left.

The Greek turned to the Swahili. "Al Sitt Lillilee," he ordered.

The Swahili vanished. Hardly a second later the latch clicked on the door between the two wide windows.

ALL doors are dramatic even in the day-time; that one of packing case pine, between two windows that framed starlit night, appeared to turn a page of mystery. Max Rector's idea of genuine drama was the rise and fall of stock market prices, but it stirred even him. It opened slowly, as if of its own volition. There was nothing. Then she stood there, as if she had come from nowhere, born of the star sprayed night behind her. With yellow lamplight on her face, she looked like a lithograph framed by the jetsam lumber of the door-posts. There was no guessing her age—eighteen—nineteen—twenty—perhaps older.

"Gypsy!" Max said after a moment, half-contemptuously. Like a roulette ball, his thought had to hurry as soon as it could into one of the regulation funk-holes. Having called her a Gypsy, he knew now what to expect, and it wasn't dividends.

Roddy corrected him. "White, by gad!"

Knowing a good bit about Gypsies is part of a professional horseman's necessary education. This girl was not one—definitely not. She had a Gypsy's stance—motionless rhythm. Lillilee? Lee might be an English Gypsy's name. But Lilly? Her face was pure Nordic. Ice-experience was in it, softened by laughter and tropical sun. She might be even Scandinavian; she had blue eyes. That Gypsy look was assumed, or perhaps imposed by association. Roddy stood up. Max remained seated. The Greek watched them, standing back to the wall, with his foot on one rung of a chair.

"Don't forget yourself," Max warned in a loud whisper. "Remember, we promised." It was quite clear what he thought of any girl discovered in that place.

Roddy, after that one explosive contradiction of Max's guess, stood silent. He knew enough to be puzzled, but little enough to be certain of only one thing: that the girl was not the Greek's property. He felt almost sure she belonged to herself; she looked so confidently curious and sure of her own right to opinions. Nevertheless, she could not be free or she would certainly not be in Zakkum, unveiled, desirable, young. Armed sloops patrol that coastline in a constant vigil against slave-runners. But there are five hundred thousand slaves in the world; slaves do reach Arabian markets, and some of them like it. The Swahili servant probably had been a slave; perhaps the Greek had freed him. Was the girl one? White female slaves are not unknown. They are not even rare. They bring enormous prices. But at eighteen or twenty they have usually lost even the look of white ancestry.

She stood looking from one to the other, unsmiling, evidently not embarrassed, but as keenly observant as if she were buying horses. She was not dressed like an Arab woman. Roddy noticed an American mail order catalogue and two or three thumbed old copies of Vogue on one of the shop shelves. The flowing line of a thin yellow silk shawl thrown loosely over a white smock made her look tall at first glance, but she was actually less than middle height and slim, healthily sun-burned and as leanly strong as a dancer in training. Perhaps not really beautiful, thought Roddy, or was she? Certainly not pretty—surely fascinating. She knew what to do with her hands, which is rare except among the thoroughly savage or over-civilized, and she was evidently neither one nor the other. It occurred to Roddy that the Greek was just as curious as himself as to how she would behave.

Max broke the silence. "What does she do?" he asked. "Dance the hootchikootch?"

"She does whatever she likes," said Kamarajes. "The last man who tried to abuse Lilly Lee got his feet beaten to jelly with the ribs of date-palms. If anyone tried a second time he'd be buried up to the neck in the sand with his face to the sun; and he'd be smeared with a little honey, although honey's expensive and the flies in these parts don't need much tempting. That's why I warned you. She enjoys the Sultan's special favor."

THE girl smiled suddenly. She looked like a boy then, with her shapely, alert looking head and dark bobbed hair; the gloom behind her had made it impossible to see what her hair was like until she walked straight toward Roddy. She offered a strong, sunburned hand. He shook it. Then she sat on the table and threw off the filmy yellow drape; that made her look not at all like a boy, but even more self-confident. There was nothing defeated about her appearance. She had the teeth of a healthy young savage and a tongue that was nearly as red as her lipstick. Her dark-blue eyes were frankly inquisitive and bright with good humor. She was not in the least ashamed to show her bare legs, and they were good to look at. Max studied them, frowning, but he kept on looking.

"Well?" she said, smiling at Roddy. She was moist from the heat, but she smelt as wholesome as a weaned calf.

Roddy hardly knew what to say, but it is a safe rule in Arabia not to begin by asking questions. He felt for the range from behind conventional banality:

"It's hot," he said. "Phew!" Then he turned his chair toward her and sat down, wiping his face on a damp handkerchief.

"Yes, I heard all that through the window," she answered—fluent English, confused accent. "You have a horse. The horse is on a ship. The ship is broken. The engine-driver says you wait until he mends it. Who is that man?"

Max used his thumb to raise the ends of his mustache, hesitating between a smile and a frown. Roddy came to his rescue:

"He owns the yacht."

"Yes, I heard that, but who is he? Why doesn't he signal for help? Is he afraid of the ships that might come? What has he been doing? Running guns? I heard talk about guns."

"No, I haven't," said Max. He wiped his glasses. "What business is that of yours, Miss? Who are you?"

"My name is Lilly Lee. I have a radio. I pick up Jerusalem, Barcelona, Paris, Dresden, Berlin, London. Haven't you a radio on your ship? All ships have them. Can't you send an S.O.S.?"

Max tried to talk down to her. "If I wish to.** He had too recently faced a public investigation to enjoy a witness chair or even a suggestion of one. He had come away to forget such horrors. But the girl made him feel timid, so he looked pompous. She was purposely making him angry, and Max knew it.

"Why don't you wish to?" she demanded.

"I carry a crew that can make repairs."

"Stingy, eh? You don't wish to pay—what do you call it?—salvation?"

"Salvage," Max corrected. "Do you call that stingy?" He tried to seem amused, but his face betrayed him.

"Stingy? I heard you offer Paulos fifty dollars. That is how many pounds? How many francs? Then you said you would give him three cases of hootch—three only. Do you call that generous?"

"I don't carry hootch on my yacht. What do you take me for, a bootlegger?" Max exploded. "Where did you learn English? It's a pity they didn't teach you to mind your own business—and decent manners at the same time."

"HAH!" She smiled at Roddy; the change of expression made her look simultaneously five years older and five years younger—young with mischief, aged by obscene experience. It must have been obscene. She swore a streak of scandalous Arabic, then barrack-room French, measuring off the last joint of the little-finger of her left hand, pointing it at Max. "You look haughty, but you don't know that much! I have met people like you, and I know lots or sorts of manners." Then she turned again toward Roddy, changing her tone of voice.

"Why have you your horse on his ship?"

Roddy fell in with her mood as the likeliest means of changing it. She might talk if he told her the truth.

"To get the horse to India."

"But why on his ship?"

"I was broke. Do you know what being broke means?"

She chuckled. "Don't I! Will you sell the horse in India?"

"No. Race him."

"Is he a jump horse or a flat horse?"

"Both," Roddy answered. "He has won as a steeplechaser and on the flat, too."

She appeared pleased. "You ride?" she demanded.

Roddy nodded. She looked him over—head to heel, shoulders, hands—

"Yes," she said, "you ride. That other man doesn't. He plays cards. He eats too much. He buys things and sneers at the people who make them. You will go from here to India? Will you put in at Aden on the way?"

Roddy glanced at Max. Max shook his head. She seemed to approve. But she was not satisfied yet.

"Why not Aden?"

"Quarantine," Max answered disgustedly. "They'd keep me anchored there a fortnight, after having visited this damned hole. Why? Why do you ask?"

She ignored him, but she seemed pleased to know he was not going to Aden. "If it were your ship," she said, smiling at Roddy.

"It isn't." Roddy almost shuddered at the thought of owning such a monstrous encumbrance. But he felt a sudden impulse to soothe Max Rector's feelings by stressing his own unimportance. Max was after all his host. "All I own in the world," he said, "is a horse and about a thousand dollars." He nodded his head toward Max. "There's your Prince Bountiful." He had almost said butter-and-egg man.

She continued to ignore Max. But she spoke to Roddy as one insider to another:

"You may bring your horse ashore just as soon as you wish."

"Thanks," said Roddy. He was not going to let anything in Arabia surprise him, but he was still skeptical. "Can you give permission?"

"I do anything I like, except to go away from Zakkum."

"She is watched," said Kamarajes. "But she has protection. Oh, boy!"

"And I have these," she added.

She produced a knife and a pearl-handled automatic, from somewhere up under her smock. The knife was a beautiful, slim-bladed thing with an ivory handle. She appeared to wish Max to notice them.

"Do you ever use them?" Roddy asked, wondering why she should think Max dangerous.

"Oh, yes."

Kamarajes chuckled. "She is watched, I tell you." He walked to the window and leaned out. Almost instantly a man peered in, not an Arab, though he wore the Arabian headdress. His coal-black face had the seldom mistakable, sexless concentration of a eunuch's. He had a wide scar from a cut that had severed his nose, but in spite of the disfigurement the face was not unpleasant; they were a sort of old nurse's features, skeptical but tolerant. He strolled away, smiling. Kamarajes, with his back to the window, grew communicative, his pock-marked face betraying, but not explaining some secret motive.

"Gypsy Lee brought her here. That was during the War, when she was little." He rolled another cigarette, watching Lilly Lee's face. "He was not her father—"

"How do you know?" the girl interrupted. "Nobody knows."

Kamarajes shrugged his shoulders. "And the woman said to be her mother wasn't her mother. She died of thieving. If she had stolen from men—" He shrugged again. "But she stole from women, so there was real trouble. Those other fool Gypsies stuck up for the thief, so the whole damned lot got taken for a ride—all except this one. They were ridden to the hell tree. But she was a little girl. And she isn't a Gypsy. I don't know what she is. Neither does she. I think they stole her somewhere. I took her to school in Jerusalem, but the Sultan stopped paying the bills—"

"You're a liar," she interrupted.

"Well," said Kamarajes, "do you want me to tell the truth?"

"No. I will tell it."

SHE was having a marvelous time, enjoying mid-stage. She seemed sure she could manage the Greek. She seemed to wish to make a good impression on Roddy. It was a puzzle why she should treat Max so contemptuously, unless she saw through his morality to the selfishness beneath. Max had been stodgily moral about women ever since a patient mistress turned up at his father's funeral and claimed common law rights. He still resented what that had cost him.

"Let's go back to the ship," Max said. He yawned to conceal irritation. "It's late. There's nothing amusing here. I'm anxious to see how they're coming along in the engine-room."

"You go," the girl retorted. "Leave this owner-of-a-horse" (she used an Arabian word) "to talk to me. Paulos shall lend you a guide."

Kamarajes seconded the motion. "Sure," he said, moving a kerosene lamp so that his own face should be more in shadow.

Max sagged back into his chair, looking sulkily suspicious. "Oh, well. There's no risk of bad weather; I guess the yacht's all right. If we take quinine we may escape malaria. Let's hope we catch nothing worse." He slapped at a mosquito.

The girl stuck the point of her knife in the table and flicked it until it thrummed. Then she faced Roddy and took up her story where the Greek had left off.

"It was Sultan Ayyub's father who paid for me at the school, although it was Paulos who took me to El Kudz*."

* Jerusalem.

Roddy interrupted: "Why Jerusalem?"

"Because I was to be brought up an unbeliever but knowing plenty. Nobody knows enough; but I know more than any Arab woman."

"It was easy to send money to Jerusalem," Kamarajes explained. "She could go to school there without forgetting what she learned here. When they educate girls in Arabia it has to be practical. Arabs say a man can learn laws and make women obey. But a girl, if she gets an education, and only about one in a hundred thousand does, is supposed to learn how to break rules and get away with it. Moslem women have to wear the burka. That's like prohibition. Lilly Lee would have been a moll behind a burka. She'd have been no more good than any other moll. As it is, she's okay. I took her to a little mission run by Syrian Christians. Money talks; so they didn't."

"And I ran away," said the girl.

"At once?" asked Roddy.

"Oh, no. I stayed three years, until I'd learned enough of that stuff. I have tried to forget most of it, except the three Rs. After I ran away, Paulos put the money for my schooling into his own pocket—didn't you, Paulos?"

"Should I have paid it to the mish'naries—for nothing?" he retorted. "All that money?"

"Sultan Abu Nakib died and his son Ayyub succeeded him," she continued. "Ayyub found out about me and about what Paulos had done with the money. Ayyub isn't a strong man. So he isn't merciful. He beat Paulos and put him in prison. But I didn't know about that. I had gone away with Gypsies, because I liked them. They didn't tell me what I mustn't do but what I can do if I learn how. I'm good at learning. So I went with them all through Europe—Syria, Turkey, Roumania, Hungary, Germany, France, England—up to mischief always. Sometimes bad mischief. Not always lucky. But they taught me to dance very well and to sing not so well; and I learned lots of languages—until we got into trouble in England and I was sent to a reform school. That was worse than Zakkum! Much worse! But I ran away when Czarbo and the rest of them were let out of prison; they weren't in long—nine months—they'd only stolen—and I learned good English—didn't I?—can't I talk it?"

Max looked as though he thought she talked too well. He refused to be interested—blew his nose and kept his face averted.

"Go on. I'm listening," said Roddy. "You will listen," said Max, "to a tale too many one of these days."

THE girl stared at Max a moment and then continued:

"Czarbo had been training me for the stage. We followed circuses and country fairs, but he always said the stage is the thing to aim at. So he trained me strictly, and he used to beat me, but not often. He was too old, and I don't think he liked me enough to beat me too much. And besides, I'm not a Gypsy and he knew that I wouldn't stand what Gypsies will. Czarbo taught me how to get money, and yet never to give men what they're trying to buy. He taught about morals and the difference between hypocrisy and good sense. Czarbo meant to sell me sooner or later; I knew that. When they let him out of prison he decided it was time for us to go to America. But when we got there they wouldn't admit us. We were sent back, and when we got to England they wouldn't let us land there either. But Czarbo had money enough to take us to France, and the French let us in, because Czarbo bribed someone. And then we were broke. Czarbo thought it time to sell me, though he didn't say so. He was afraid there'd be trouble about it, because I'm not a Gypsy and he knew I'd raise hell. I don't choose to be sold. Czarbo himself had taught me why not."

Max snorted.

"Carry on," said Roddy.

"I always do carry on, as you call it. But it isn't always simple. I was carrying on in Marseilles when Dimitros found me. I was dancing in a cabaret near the docks, and singing on the docks when steamers came. Czarbo was dead, and it was difficult to keep the nervis of the Vieux Port from making me a mere piece of meat in their market. I had to make them fight about me. They fought with knives and slew each other. But Czarbo's women—there were three of them—had gone; I didn't like them, and they didn't like me. I had learned I couldn't live alone in Marseilles when Dimitros saw me."

"Who is Dimitros?" asked Roddy.

"Paulos' partner. He escaped when Ay-rub—"

"You mean Sultan Ayyub?"

"Yes, when Sultan Ayyub beat Paulos and put him in prison. Dimitros said Paulos would die unless I went to Zakkum and explained things. Ayyub would tire of feeding him and would let him starve, or perhaps tie him to the hell-tree. But Dimitros begged me not to go back. He said I'd probably forgotten Arabic, and I'd be put in Ayyub's harem or something worse. He said he'd make my fortune in Marseilles. I didn't wish to be sold by Dimitros. Some day I myself will sell me, for my own price."

"How much?" Max asked.

She ignored him, except that she turned away a little. "So, I came to Zakkum to help Paulos."

"How did you get here?" Roddy asked her.

"Oh, that wasn't difficult. I have acted boy all over Europe. I used to ride Czarbo's horses, when he had any. I used to help Czarbo to steal horses; that was how we got into trouble in England. I stole five hundred francs from Dimitros, and I gave them to a Frenchman to smuggle me on a big passenger ship to Alexandria. I nearly got caught in Alexandria; I had to hide amid drums of gasoline on the dock. But I got away all right. I told a rich Jew that my mother was dead. Jews love their mothers. That Jew paid my fare on the train to Cairo, and his wife gave me food for the journey. Then I begged my way to Sawakin, by pretending I had been lost and left behind by a family of pilgrims on their way to Mecca."

"How did you cross the sea to Zakkum?"

"The way the slaves all get here. That's simple. Don't you know about it? I offered myself to a dealer in slaves. If you cost them nothing, and you look good, you can always bargain to be taken to the market you prefer. They might get into very bad trouble if they broke faith with a slave who knows the law, and isn't afraid of the police. I had to let that dealer know I'm a woman, because that made me perfectly safe. Spoiled goods bring low prices. And besides, he was an Arab, from Makalia, and they're good with women. After I was safe on the dhow I told him why I wished to go to Zakkum. He had ten other slaves in his dhow, and those he sold in Zakkum, but he refused to sell me. He was a good man. All his slaves were fat and happy when they landed. He let me make my own terms, although, of course, he made his, too. He made a profit. That's how Paulos got out of Ayyub's prison. I have been here three years."

"Do you like it?" Roddy asked her.

"I hate it. But I can't get away."

"You've only to appeal to a consul," said Max, in a voice like a banker refusing a loan. Max could make common sense sound hateful.

SHE stared at him for a moment and then answered scornfully: "Which consul? Of what country? Where is my country?"

"Any consul would report you to the League of Nations."

"Oh, yes? What would they do? Marry me to the Prince of Wales?"

Max glared at Kamarajes. "What's wrong with you, that you don't take her away from here? Of what country are you a citizen?"

"None," said Kamarajes. "I can't get a passport."

"Why not? How did you get to Jerusalem?"

"Any o' your business?" the Greek asked.

Max stood up, shoving his chair away noisily. "Come along," he said. "Haven't you had enough? Let's get back to the yacht."

"What were the terms you made?" asked Roddy. He made a gesture to Max to wait a minute.

"Paulos out of prison. Me to have my liberty in Zakkum and be Ayyub's—"

"Spy," said Kamarajes.

"Until Ayyub chooses me a man agreeable to him. But I must also agree. He can't give me unless I'm willing."

"Would you break the bargain?" Roddy asked her.

She nodded. "Ayyub broke his."

"He did not," said Kamarajes. There was pride in his voice.

"Well, he tried to. But I'm popular. I raised hell. Ayyub didn't dare. So now he wants me to go to Mahmoud ben Amara, who is a fat barfush* with a harem in Mecca and makes money cheating pilgrims. Ayyub owes him lots of money. But that was not in the bargain either."

* Blackguard.

"We can't interfere," said Max. "I don't suppose the law can help you. By your own account, you're here of your own free will. If you're as popular as you say, your Arab friends should help you."

"They want me here," she answered and turned her back to him.

"Well, it seems you made your own bed," said Max. He walked up to Roddy and touched his shoulder. "Are you coming?

"How about the horse?" asked Roddy.

THE girl glanced at Kamarajes. "First thing in the morning," said the Greek. "I'll be out there myself with the scow. Another drink, gents? No? All right. Two of my men shall see you to the beach. If you've any old newspapers or magazines—"

"Perhaps my steward has some." Max unbolted the door. He jerked it open. "Are you coming, Roddy?"

Roddy shook hands with Lilly Lee. "Were you telling us lies?" he asked, smiling.

She looked straight in his eyes. "You know dam-well I wasn't."

"Any woman who wants to be is safe with Arabs," said Kamarajes. "Arabs are all right But it can't last forever. And then what?"

"See you in the morning," Roddy answered. He didn't know "what." He followed Max. Two of the Greek's black servants accompanied them with lanterns as far as the beach, where the boat's crew waited. Max sulked until they reached the yacht, half a mile out from the shore. When they reached the dock he blew up.

"Nolan, you're crazy. You're an example of perpetual motion—out of one trouble and into another. I believe you'd go long of hot air if a crook had the nerve to ask you money for it You wouldn't be broke if you weren't a madman. Dammit, man, you swallowed that girl's patter like a rube at a circus side-show. Couldn't you see she was playing you?"

Roddy had seen that perfectly. He leaned against the bulwark rail, looked up at the stars and then cupped his hands to light a cigarette. What was the use of saying anything? A man whose entire fortune consists of a heat-crazed stallion and about a thousand dollars can't afford to be quarrelsome, and he was not a quarrelsome fellow anyhow. But a disagreeable man with a huge yacht is in poor case too, unless he likes to be lonely. It is easier to fill a hotel with good companions, especially after one's financial secrets have been scornfully investigated and exposed to public derision. Max was sensible enough to guess that Roddy Nolan might prefer to take his chance in Zakkum rather than be hectored, no matter how much he needed hospitality. He changed his tenor:

"If you'd had as many women try to blackmail you as I've had, you'd be more suspicious. Roddy, my boy, you're too good-natured and too trusting. Take my advice and keep out of trouble."

"Yes, you have trouble enough," said Roddy.

That smoothed Max; he loved the subtle flattery of being told his troubles were a Titan's. He became grossly condescending:

"Fall for her, if you choose, old fellow. I'm no lady-killer, but I know what the biological urge is. But don't be a sucker. Don't get that knife in your back. Keep your eye on that Greek. Above all, don't bring the girl to the yacht. She might make endless trouble. International law is dangerous stuff to monkey with. There isn't exactly a Mann Act on the high seas, but—"

"Oh, the hell with her," said Roddy. What he meant was, the hell with Max Rector, but he had to get along with the man somehow, and it was useless to try to explain his view that only those whom Max could call suckers enjoy life. Genuine suckers are rare, but have few regrets. Not being greedy, they don't have to bury their greed later on in the ashes of disillusion. A proper sportsman, according to Roddy's view, expects less profit than entertainment, but gets plenty of that; it doesn't trouble him much to be called a sucker by the sort who think that fear is righteous and greed is principle. Roddy had frequently betted his boots on a hunch, and had frequently lost. But he also had frequently won, and he had seldom been bored, except by such people as Max. He had a horse, a thousand dollars, his health and the ability to enjoy them all. But he wanted to live to enjoy them. He knew that the biological urge is a short means to a sure and dreadful death, for a foreigner on the Arabian coast-line. He despised Max for being such an ass as not to know that.

He strolled aft for a look at his horse, stalled in a huge crate between the motor-driven ventilators. Max went down to the engine-room, to insult the engineer with platitudes and to annoy the sweat-wet crew, who toiled in the glare of electric light amid dismantled engines. Roddy gave the horse a carrot, talked to him a bit, and then sat on the top of the horse-box, gazing at the stars, wondering why, in a world of about two billion people and a hundred and ninety-six million square miles, he, Roddy Nolan, should meet such a girl as Lilly Lee, in such a place as Zakkum, because of a broken-down Diesel-electric engine. Is there such a thing as destiny? Or is everything chance? There are traps that leave devilish little to chance; he knew that. He could see the bait. He could guess the trap. But why? What for?

"Well," he remarked to himself at last. "If the stars know anything, they don't tell a fellow like me. I guess the only way to find out is to bite and sec what happens."

MAX had few respectable gifts, not even a real flair for navigation (which is very different from seamanship). His genius was for what he called "the conservation of resources;" other people called it hogging dollars. Master as well as owner of the Blue Heron the trick, as he would have called it, of commanding respect from junior officers eluded him as completely as the art of making friends and keeping them. Of the three certificated officers who had signed in New York for a voyage around the world, not one remained. Max had had to pick up substitutes in Marseilles and Alexandria, and he had had to take pot luck at that. All three were already insulted and dissatisfied. Worse yet, his original engineer had told him, in Alexandria, to hire the Devil, if the Devil felt like being made a fool of; he had gone ashore with his belongings, and had raised hell at the consulate. Max had had to "compensate" him. After several days' delay he had found a middle-aged Scotsman out of a job; he didn't like him or trust him, but he had to take him; and either MacNamara didn't thoroughly know diesel-electric engines, or else he had obeyed Max too implicitly against his better judgment. Anyhow, the engines were in a devil of a mess. Daybreak found the sleepless MacNamara, wild-eyed and half-naked, interrupting Max in silk pajamas at his morning tea on the bridge deck.

"Progress?" Max asked. Before he had shaved he was always in a supercilious mood.

To raise your eyebrows at a hard-bitten Scotsman is about as tactless as to stick out your tongue at an Irish cop. The dregs of MacNamara's suavity, if he ever had any, went overboard along with the sweat that he stripped off his brow with messy fingers.

"Aye. It depends what's progress. I have r-reached a deceesion to warm ye to tak' a tow, if ye can get it—back to Suez, I'd say. Come a westerrly, ye'd have a bad lee. Come a southerrly, ye'd lie worrse. Come a northerly, ye'd drag as sure as death an' taxes."

"How long?" Max asked.

"Ten days—meenimim. An' that's provided I can keep the crew contented wi' a bonus. They're a puir lot o' Bolsheviki—verra ineffeecient—an' they're feelin' the heat. They've the right o' it, claiming overtime, and—"

Max interrupted angrily. "They signed on to work, not to take a vacation."

"Aye. But they'll tak' no imposeetion. Ye'll gie a bonus, or ye're up against a deefficulty. That's my opeenion. Man, we've to tak' down an' reassemble half Schenectady. An' marrk those Arabs. It 'ud cost ye less to tak' a tow to Suez, than to fall foul o' such heathen as inhabit these parrts. Are ye insured against a cutthroat?"

The scow was coming, towed by two rowboats, surrounded by about twenty more. In the stern of the scow Kamarajes waved a slouch hat to Roddy Nolan, who already had the horse-box slung to his liking. All sorts of gadgets down below had been disconnected and there was no power available for the winch at the moment, but Roddy had made friends with the mate, so half the crew were standing by to man the derrick and lower the big crate overside. Roddy, in an effort to calm the stallion's mood, was up on the top of the box with the hose, but the water came up warm and sticky with little comfort in it. "The Prophet" was trying to kick the box to pieces. Having discovered very early in the voyage that the sailor, who volunteered as groom for the extra pay, was afraid of him, the horse had turned so savage that Roddy himself had to do the grooming and cleaning out, until Max, in disgust, had hired a Port Said Gypsy. But the Gypsy was also afraid, and had deserted at Suez. He was supposed to have jumped overboard after they put to sea; his name was still on the manifest, but the desertion had not been logged; Max had told the second officer to make the entry, but had given him such a hell of a bawling out for something else that the second officer had simply forgotten to do it. Max loathed the sight of the second officer; he had just ordered him off the bridge. To see Roddy, after all his guest, doing the work of a hired sailor, made him furious.

"Dammit," he exploded. "It's a holdup. Bolsheviki is right. These engines are supposed to be the last word—fool-proof."

"Aye. But they're no proof against temperamental improprieties."

"I believe it's a case of sabotage. However, I'll have to pay time and a half, I suppose. Blackmail, I call it. It's up to you to sec they earn the money."

"And a leetle liquor? It's bad in preenciple, but verra good practice if y'r conscience isn't over strong f'ry'r diplomacy."

Max scowled. "I will tell the steward."

"Mind ye," said MacNamara, "I can give ye power for the radio, an' my advice is to use that an' beg a tow to Suez. It may be costly, if we run into a head wind, but let the underwriters pay. We can patch her up here after a fashion. Aye. Ye can make Bombay, I don't doot, if the Arabs let ye. But ye don't know Arabs. Ye'd be in a predeecament if they discovered how helpless ye are."

THE word "helpless" enraged Max so that he couldn't think except that MacNamara probably was scheming to work a commission from the repair-yard in Suez. On that awful morning when he had sat in a witness-chair to be investigated on oath, a federal attorney had called him a "helpless product of chance and cupidity, quailing like a coward from the public scorn," merely because he had "not remembered" something or other. All the papers had carried it along with his picture. He had hardly cared to face even his stenographer. The surreptitious grins at the club had been unbearable. If he should take a tow to Suez now the papers would yelp with glee about it. He had come away to escape publicity, not to court it Besides, he wasn't helpless. He resented the imputation.

"The Arabs are all right," he said sulkily. "I made the necessary overtures to them last night. It's merely a question of being diplomatic. Mind your own business."

"Verra weel," said MacNamara. "But ye'll kindly log my statement of opeenion. And I tak' the liberty o' recommending ye to let none o' the crew go ashore."

MacNamara went below, fuming. Then came Kamarajes, with a slouch hat in his hand and a genial grin, climbing to the bridge-deck uninvited. He looked overexposed against the blue sky; on his face were deep dark shadows that made his smile look sinister.

"Good morning, Mister. Three cases of gin, you promised, and some old magazines—"

Max jumped up from the deck-chair. "Get off my bridge!" He suddenly remembered then that the Greek might prove useful, so he changed the tone of his arrogance. "My good man, don't you know it isn't customary to walk up to a yacht's bridge without being asked? I'll overlook it this time, but don't do it again. Go back to that scow, and I'll have your needs attended to. And by the way, while you're about it, tell those Arabs to keep away. You understand, I want no visitors. Tell 'em to keep off."

The Greek bowed beautifully and retired to overtake MacNamara and oil his way into the engineer's good graces. Max rang for the steward. When he had given his orders he watched Roddy on the top of the horse-box being lowered overside. He wondered how a man could find amusement in such undignified gymnastics. How could he laugh and enjoy himself, with nothing but a second-rate racehorse and about a thousand dollars between him and destitution? He'd get sunstroke if he wasn't careful.

He'd end in a poorhouse—not a doubt of it, unless he broke his neck first. Gentleman, yes; but what's a gentleman? Happy-go-lucky and popular, yes; but what's the use, unless a man knows how to get work done for him. Imagine a gentleman grooming his own horse. Not a bad chap—stupid—bound to lose out. It was perfectly obvious to Max why some men have no money.

Roddy waved from the scow. He pointed to the gin and magazines and made a foolish crack about The Prophet needing cigars, too, and an armchair. Max called back to him through a megaphone to be sure to keep women and bed-bugs off the yacht, and not to fall for any con game. "Don't even tell 'em your age," he shouted.

Kamarajes, wiping his mouth, made a run for the scow. The scow began slowly little more than drifting toward Zakkum, behind laboring tow-boats, over an oily sapphire sea on which the weed made parallel streaks of mauve and iodine. Roddy used binoculars to study out the problem of getting the horse to dry land. That ruinous jetty had looked good enough in darkness, but he could see now that it was fit for nothing but to dry fish-nets. Its derrick was a ruin of rusted iron and rotten wood.

"We will lay planks from the scow to the beach," said Kamarajes, noticing Roddy's frown. "What have you in that bag?"

"Oats."

"No, in that other bag."

"Oh, that? Mosquito netting. Flies 'ud drive The Prophet crazy."

"Oh! Is his name The Prophet?" The Greek went into roars of laughter. "That is a hell of a good joke! By Allah, that will make these Arabs cockeyed! I will tell them that you lead The Prophet by the nose—oh, ha-ha-ha-hah!"

HE BEGAN to tell it to the scow's crew and to shout it to the rowers. Arabs don't laugh at a joke of that sort; they take it seriously, mulling in their minds its subtleties and implications.

"They will tell that to each other all night long," said Kamarajes. "There is nothing they enjoy more than to sit on the roof with a pipe and argue is it blasphemous, or is it a good omen."

As they neared the beach the gruesome ugliness of Zakkum solidified out of the haze and shimmered in refracted sunlight. The inevitable yelling conference began among the boatmen. Each of them knew exactly how to get the horse ashore, but no two agreed. The conversation became as vivid as the beach stench, most of it taking the form of interruptions to advice yelled by someone else at Kamarajes, who ignored it, watching Roddy.

The scow was a left-over from the World War; it had very likely been a pontoon in the Suez Canal, and how it ever reached Zakkum was one of those inscrutable mysteries that in the end perish unsolved or give birth to impossible legend. For a wonder, it was decked; the deck was in fair preservation; the horse-box stood erect like a house on a scow in the Hudson River. The rowers having ceased their labor, for the more amusing effort of obscenely abusing one another, the scow swung beam on, about fifty yards from the beach. There was a crowd on the beach; it also had plenty to say and lots of lung-power, yelling contradictory advice, amid swarming flies whose drone was like the hum of billions of bees. It looked like an unpropitious landing place for a horse that had the temper of a dozen devils in him.

"Leave it to me," said Kamarajes.

"Sure," said Roddy. "You arrange it."

Kamarajes raised his hand and filled his lungs to harangue the crowd. Roddy slipped a bridle on The Prophet, opened the front of the box and mounted bareback as the stallion came ramping forth. The feel of Roddy's heels in his flanks acted like a hammer on dynamite. He reared skyward, lunged out with his forefeet, bucked, took the bit in his teeth and went over the end of the scow as if the fifty yards of sea between scow and beach was the Brook at Aintree.

No matter what theorists say, the Red Sea sharks are dangerous, even close inshore. Roddy knew that, but he slipped off to give the horse more buoyancy, and swam, bare-headed, watching his chance to re-mount in a hurry as soon as the horse's feet touched bottom. He almost missed it; the horse shied away from him. But an Arab waded in waist-deep and gave him a leg-up as The Prophet paused for one second and then lit out for the dry land in a plunging gallop. There was no sense whatever in trying to call a halt in that torturing swarm of beach-flies; in spite of the stallion's drenched hide they were stinging him already—stinging him frantic. Roddy gave him his head. They went up the principal street of Zakkum like Disaster on unshod feet.

There nearly was disaster. Two kneeling camels, rump to rump but overlapping, loaded with piled hides, blocked the full width of the narrow street. The man in charge of them did exactly the wrong thing; he snatched the camels' heads and tried to make room to pass. The Prophet reached them as they started swaying to their feet. He leaped them, loads and all. For the sheer excitement of feeling his legs at work, he lashed out and kicked one camel sideways into the other, so that they both rolled in the dust. Then on up-street past Kamarajes' place with a couple of dozen yelping curs in full pursuit.

Roddy sat still and looked around him. Seven furlongs ought to be about the limit for a horse so badly out of training; The Prophet would stop himself in a minute or two; he was blowing already. But the length of the city was much less than seven furlongs, and they were still going strong when they came to the Gate of the Doomed and went under it in a cloud of dust. It was an arch of stone and stucco, patched with gray mud, with broken mud walls to right and left. Vultures used it as a roost; as the horse galloped under the arch they took wing—ink-blots against azure. There was a slaughter-yard beyond, with more vultures; and beyond that stood the naked hell-tree, as white as bone in the early sunlight, vultures on every branch. Then the dismal looking cemetery, enclosed by a broken wall. Beyond that, desert—aching gray-white solitude as far as treeless hills on the horizon.

DOTS on the desert, the size of inserts, followed by a dust-haze, the dots growing larger. The Prophet slowed to a canter—presently to a walk. Roddy let him walk, patting his neck. The distant dots became horses—fifteen—twenty. Something followed in a cloud of blown sand. It looked like a field-gun. Roddy knew that Arabs have an instant prejudice in favor of anyone whose seat on a horse is superb. He might be vain about his horsemanship, but he was not conceited. He could ride, and he knew it. He knew Arabs would immediately perceive that, before anything else. True, The Prophet was blown; he had no saddle; Roddy was still wet and had lost his hat; but those were trifles. He made the stallion show off, until the Arabs reined their horses and their leader came slowly toward him.

He was a sly-faced man with a scant beard, in a yellow and white striped cloak and kuffiyeh, on a gray mare. He had a golden dagger at his waist and the last word in modern rifles in his right hand. There could be no doubt who he was—the Sultan Ayyub, on his way home, followed by his Ford car. It was drawn by four camels, and it probably contained some ladies of the harem, but they were well hidden behind awnings.

"Gasoline," thought Roddy, "is the right sugar for this canary." There were several drums of the stuff on the Blue Heron's deck, in reserve for the use of the tender; he wondered whether Max would part with any of it, but he knew Max's moods of stupid parsimony.

Stately greeting. "Peace in the name of the Most High. Peace be upon you. In the name of the Prophet, God's peace." Compliments invented in the dawn of time, by people to whom words are the mask of thought, the grace of courtesy—or else vile beyond limit of possible deed. An Arab's blasphemy is as imaginative as his compliments. They dismounted bowing lordly to each other. One of the Sultan's escort brought a head-doth, so that Roddy might cover his head and be unembarrassed; only a slave should be bareheaded. There was curiosity and much discussion of The Prophet, none had seen such a huge horse. He was unbelievable. One man, feeling the brute's tremendous jumping muscles, narrowly missed death from a fiery irritable hind-hoof.

Roddy told his story, in remembered Arabic that grew more fluent as he used it. And because one horseman thaws out to another and forgets prudence, he spoke of The Prophet's victories on the turf. But he spoke, too, of the yacht's predicament, not forgetting to praise Max Rector as a prince of good fellows, a father of honor, whom all men praise, whose fame precedes him over land and sea.

The Sultan nodded. He too, used time-honored phrases. All that he had was not good enough. Let the effendi only dignify him with his company as far as the palace; there the horse of horses should be stabled, groomed and fed as if he were that very stallion that Allah's Prophet rode to Heaven.

Roddy felt he was getting the breaks. This was better than being beholden to Kamarajes. True, it was likely to prove expensive; he would have to make a valuable present to the Sultan. But the horse would have expert handling by men who have forgotten more about horses than the West ever knew. Max could lie at anchor safely until the yacht's engines were repaired. There would be no risk of piracy, since friendship was now established. Roddy joined the cohort, breathing dust in their midst as they cantered toward the city.

He was not particularly worried when two of the Sultan's escort led The Prophet through a great gate in a white wall. He would have preferred to enter and see the horse stabled, but it didn't matter. To have insisted might have been a breach of etiquette; to keep the good start going smoothly seemed all-important for the moment.

The Sultan invited him into a courtyard lined with tired geraniums in tin cans. There was a waterless fountain, one date palm, and a savage baboon on a chain. Roddy and the Sultan drank coffee together from tiny silver cups. They ate dates from a silver dish, and stodgy pastry made with honey. The Sultan lent him a beautiful she-mule to ride away on, and then dismissed him with the gracious formula:

"Deprive me not too long of thy presence."

NOW that kind of she-mule is known as a Baghlah, and is notoriously difficult to ride. Perhaps the loan of the glossily lovely, long-eared illegitimate offspring of Balaam's ass was meant as a compliment to Roddy's horsemanship. A slave accompanied the animal; he was supposed to run ahead and clear the way, but he lagged far in the rear until the mule, which did everything except lie down and roll, reached a crowd at a cross-street. The crowd scattered at sight of the beast; no meeting of "reds" in Union Square was ever more efficiently dispersed by New York's "finest." Roddy was dispersed, too, into a pile of thorny camel-feed in an alley between two house-fronts, landing on head and shoulders. He was not hurt. Like most genuine horsemen, he was more amused than annoyed, after he had felt himself all over. The mule had bucked off her saddle and departed in the general direction of the desert in quest of room for self-determination. The sweating slave pursued her with an air of having a long day's task ahead. There was nothing more to be done about that.

Roddy stared about him. He could see at a glance why the Prophet of Allah forbade that the sound of women's voices in a dwelling should be audible from without. Neighbors have the right to prevent such a scandal and they normally do, like small town neighbors all the world over. But the Prophet of Allah had not foreseen the coming of radio, or he would undoubtedly have forbidden that also, along with wine and ham and more than four wives. One would have had to bootleg radio sets, like hasheesh, and release their deadly entertainment behind curtains in the dark.

Women in Paris, who had very likely never heard of the Prophet of Allah, were singing a French version of a New York torch song. The unnecessary words were no impediment; the Arabs perfectly understood the meaning of the music that poured through the slits of a Zakkum shutter. It was bad for business. It had emptied coffee shops. The crowd that had been scattered by the she-mule was already returning to be seduced, orally, by exotic rhythm that, according to the Prophet, bars the door of heaven, though suggesting its perpetual delights. Their Prophet had understood them perfectly. They even ignored Roddy, they were so preoccupied. Their eyes glowed with the ferocity of sunshine-incubated passion, censored and forbidden to emerge from the folds of pious dignity. They were being bad boys, all afraid of one another's evil thoughts, each ready to accuse the other. Into their midst rode Kamarajes on a big white donkey. His smile was discreet; it suggested the basis of mutual goodwill and forbearance. He, too, had his little peccadillos; if they had theirs, he could sympathize. He did so. Birds of a feather.

Dismounting, he flourished his slouch hat, offering his mount to Roddy with a bow that would have graced d'Artagnan. But it was not more than two hundred yards to Kamarajes' store on a parallel street. The Greek was evidently nervous about talking outdoors; he even put a warning finger to his lips, so Roddy fell into step with him and they turned a corner with the donkey's head between them. Even so the Greek said nothing until they had reached his doorway, where he shouted for a servant who came and led the donkey away. The Swahili of the previous night peered through a slit in the door before he opened it to admit them; then he said something sotto voce.

"Bring her," Kamarajes commanded in Arabic. The Swahili slipped out like a white-robed ghost and Kamarajes shut the door. He bolted it. "Everyone in Zakkum is a spy," he said, smiling at Roddy. "If there is no news, they invent it." Then, over his shoulder as he groped in the liquor chest: "I know what has happened to the horse already. Your confidence has been abused, Mister."

Roddy said nothing. In a flash of ghastly realization he almost lost self-control. He, too, knew what had happened to the horse. It dawned on him, suddenly. He stiffened himself. He felt fear at the pit of his stomach. Rather than speak he walked toward a window in the rear and stared at the piles of hides in the courtyard. The blue sky and the brazen sunlight made the whole scene shabbily unromantic; its keynote was the stinking piles of hides and the lousy vultures on the roofs. The wall on one side of the yard was formed by a long shed that might, or might not have a door in the wall at the far end. Beyond the end-wall was another courtyard and another long shed. Beyond that were the backs of houses in the next street; one was probably the house from which the radio music came. It sounded now like the distant dirge of dead hope.

"Have a drink. Take a good long shot," said Kamarajes. "You need it, Mister, after that swim."

"No, thanks." Roddy stared around him. He noticed Max Rector's gin, the bundle of old magazines and his own bags of horse-fodder and fly-netting. They had already been stowed away under the shelves and he resented it without any particular reason. He felt like picking the first quarrel he could find excuse for. Memory of the exasperating smugness he had had to endure from Max Rector made him grit his teeth. The certainty that Max would make the utmost of this new excuse for airing superior wisdom filled him with fury. The Greek recognized danger and at once poured oil on the troubled water. It might be inflammable oil, but it served the present purpose.

"MISTER, you made that too snappy. I said last night I'd have to tell your business to the Arabs. Someone went off in a hurry to tell Sultan Ayyub. That's why he returned. And now you've given him the horse—all Zakkum says it. I'd have warned you, but you jumped off the scow too quickly. If you want that horse back, you and I will have to do some smart thinking."

Roddy eyed him with frank suspicion. How could Kamarajes possibly know so soon, unless he had known sooner—in advance? If it was a steal, and if Kamarajes was in on the steal, the Sultan might be stingy about commissions and Kamarajes might be planning a coup for his own account. If so, the sooner Roddy knew about that for certain, the better.

"The horse wasn't a gift," he said. "You know that, and so does the Sultan. But what good would it do you if I get the horse back? I've no money. My friend who owns the yacht won't come across. There's nothing in it for you that I know." Kamarajes pushed the glass toward him. "Drink up, Mister. I wouldn't take your money; I know a sportsman when I see one. But there's mow in this than meets the eye, as the Tammany boss said on election day."

"Are you in on it?"

"Deal me in and then I'll help you, Mister."

Roddy's suspicion was stronger than ever. Like the pious Aeneas of old, he distrusted eleemosynary Greeks on all counts of any indictment. But he was beginning to regain his self-command and to think without imagining Max Rector's contemptuous comments. If it was true that Sultan Ayyub had already spread word that the horse was a gift, then that proved it was not a mistake he was making. It was move number two of a slick trick, thought of between night and morning. Roddy felt sure Kamarajes knew that.

"Did you say all Zakkum is talking about it—already?"

"You bet. No need for a telephone in this man's town. News spreads, when it's meant to."

"Do they say why I'm supposed to have given him the horse?"

"Sure they say, nothing for nothing. You came and asked protection for the yacht, while sailors mend the engines. What is more, you'll get it, Mister. That's to say, unless your friend gets ugly. Scratch a Red Sea Arab and you find a devil. Treat him civil, and he's all right."

"Smooth work," said Roddy. He drank the whiskey; there was no sense, at the moment anyhow, in quarreling with Kamarajes. He set the glass down with a bang. "Someone," he said, "thought quickly. Whoever carried the news to Sultan Ayyub in the desert, also tipped him what to do about it. He had the plan on ice when he met me."

Roddy felt eyes on the back of his head. Someone had peered in through the courtyard window. He turned. There was no one any longer at the window, but the door opened and in walked Lilly Lee. The Greek bowed extravagantly as if she were almost a stranger, but Roddy intercepted a glance between them. She walked straight up to Roddy and offered her hand, looking not much different by daylight, except that it was easier to recognize the Nordic spirit beneath the gypsy impress. Her face was sunburned, not naturally swarthy; it was clear, smooth, healthy. She had on an Arab woman's costume, but that made small difference; trousers and black cotton cloak could not hide athletic grace, they emphasized it, though they did reduce her apparent height. She was neat, trim, exciting to the eye, whatever else she might be. She carried in her hand the shawl that should have covered her head, and her dark blue eyes stared at Roddy with a fearless curiosity that disturbed him although he knew no reason why it should. He decided to take the offensive, to startle information from her.

"What do you stand to gain," he demanded suddenly, "by advising Sultan Ayyub to pretend my horse is a gift?"

Her answering smile concealed her thought; beneath it were infinities of unexplorable reserve. He knew he did not understand her. Perhaps he could not. She seemed to wish him to try. Her eyes danced with laughter. Her voice was excited:

"Freedom to leave Zakkum!"

RODDY refused to smile. He tried to stare her out of countenance. He had the white man's almost ineradicable, because almost unconscious attitude of social superiority. She might be white; in fact she certainly was, but she had lost her heritage.

There was a great gulf fixed between them. However, he didn't see that that mattered. He had no intention of getting involved, no matter what her morals; he deliberately bridled an impulse to kiss her and see what happened. He spoke sternly as if to a servant:

"So you thought you'd buy your liberty with my horse, without consulting me?"

Her smile flickered—faded, and her face grew quiet with ambushed purpose—intelligence biding its time. Her silence made him feel he had perhaps guessed wrongly. There was something winsome about her, but nothing weak. She brought to mind the picture of Cleopatra standing before Caesar on an unrolled carpet. She appeared to be deeply interested, perhaps puzzled, but perfectly sure of herself.

"Now I suppose you will be leaving Zakkum?" Roddy suggested.

"How?" she asked. She seemed to think he might know..

"It's usual, isn't it? Tricksters always spring their trap and clear out. Don't Gypsies? You were taught, you say, by Gypsies. Steal and run. Why don't you? Or are you planning to steal the yacht, too?"

She laughed. "Do you want your horse back?"

"I intend to have him."

That was stark bluff. Roddy felt ruined and desperate. He remembered Arabs well enough to know the only way to get his horse from Sultan Ayyub would be by bargaining. He had nothing with which to bargain. Even his thousand dollars was in the form of a personal draft on Bombay; it was not negotiable except at a bank, and there is no bank in Zakkum. He felt violent. Perhaps if he should tempt this girl out to the yacht in defiance of Max Rector's prohibition, she herself might solve the riddle.

She was probably the Sultan's evil genius. How else could she be free of Zakkum, unveiled and free to talk to strangers? Who else, except possibly Kamarajes, could have known enough of the circumstances to be able to advise the Sultan to act so promptly, and so neatly? Why not tempt the girl on board, and then tell the Sultan he could have her back in exchange for the horse?

But Roddy glanced at the rear window. There, in the courtyard, blocked against the blue sky, smiling, stout, secretive, was the eunuch; he had an automatic, a long dagger and an air of not needing to worry as long as he kept awake. From the street came the noise of a crowd assembling at the Greek's door. Voices clamored for admittance.

"And he jumped two loaded camels! What a jump! Mashallah, what a jump!" said the girl. She seemed to prefer to speak Arabic. "Arabs' horses aren't taught to jump. They never do it—never. They gallop around things."

"Tell me," Roddy asked her. "Did you, or did Kamarajes think of it? I was taking that horse to India to try to make some money by winning races. Now I'm broke to the wide world. Which of you did me the dirt?"

She answered again in Arabic: "I understand. If Paulos did it, you would kill him? But—Allaho-Aalam*, it was not Paulos. I thought of it I. Will you kill me?"

* God knows.

"You deserve it," said Roddy. "Will you come with me now to the Sultan and ex-plain there has been a mistake?"

She chuckled. "There has been no mistake. Ayyub loves a horse-race more than song and women—more than prayer—more than all else. He will put his trainers to work to get that horse in condition. Then he will challenge Abdul Harrash, of the Beni Harrash Bedawi, to whom he has lost so many races that he bites his nails. He has lost money and camels and slaves and pearls to Abdul Harrash. He will bet me, this time."

"Oh—you wish to go to Abdul Harrash?"

"BETTER to him than to the fat fool in Mecca. But if I craved an Arab, could I not have made my own choice long ago? I need only to say that I wish to belong to a man, and there is not a shaikh in all this country who would fear to come and rape me away from Ayyub."

"She has pull," said Kamarajes. He went to the door and opened it a trifle, making signs to the crowd to be quiet. He re-bolted the door. "She has political pull I tell you."

She had "pull" of a much less contemptible sort than that. Roddy was becoming thoroughly aware she had it. Without a gesture, without a suggestive word or glance, she was conveying what millions of women fail to, for all their striving. She was an original, owing nothing to convention; and either because of training or intuition hers was the priceless strategy of telling much less than she knew, in order to accomplish what she only guessed at, and wanted. She was not beautiful enough to rely entirely on beauty; she had to use brains. She was not civilized enough to be afraid to choose between good and evil, as she judged them. Deep in her eyes that saw through surfaces lay scorn of past experience, contempt for the present—and something else limitless, it might be patience, or it might be passion, or perhaps both. She stirred Roddy strangely.

Perhaps she guessed that it was easier to stir him than to turn him from a taken course. Roddy was a neck-risker, reckless of no other neck than his own. The next jump always was his goal; his frequent successes had come of making each next post a winning-post. When he lost, no matter how he felt, he looked indifferent; it was the mask from behind which he judged wild chances. As he stared at the girl he wondered why her eyes were so full of—was it laughter? Excitement? Damned if he knew. He had learned what little he knew about women by being ignored or half-affectionately patronized by most of them. Only the rare ones liked him. His irregular, gray-eyed, humorously rugged face had been browned by the weather and scarred by accidents. He was no Adonis. Not a she-moth's hero. But he could make this girl's eyes glow, and she could make him tremble.

"Your friend who owns the yacht," said Kamarajes, "is a horse's rump. He is a—"

Roddy silenced him with a scowl; the more he let Kamarajes talk, the less he was likely to learn from the girl. The Greek slid him a drink along the table; he accepted it and looked straight at her.

"If Ayyub betted you on a horse-race, and lost, would you go to the winner?"

She answered again in Arabic: "Why not? I am weary of Ayyub. I would claim the protection of Abdul Harrash. AH his women of course would try to seduce me for him; but in Arabia a man would rather die ten deaths than take a woman by force; and if he did, he could never lift his head again among equals. I am my own, until I give up."

"Then why not leave Zakkum? You said you hate it."

"I am not free. I told you. I may not leave. They watch me." She glanced at the window, where the eunuch stood as patient as a stalled ox.

"Have you no money?"

"No. If anyone should give me money, they would confiscate all that he has. Should I ruin a friend by accepting alms? I may have all I need, but no money. And if Paulos should help me to go away, where should I go? They would beat Paulos; they would draw him between camels and then tie him to the hell-tree. Paulos is my good uncle and the preserver of my life when I was little."

RODDY found he had to govern impulse with an iron will. There was less iron in the will than he felt he needed. He had to remind himself that he wasn't a plumed knight in shining armor rescuing damsels from durance vile; the age of chivalry is over. Neither was he Don Juan; he had to remind himself also of that. "Let's talk horse," he suggested. She nodded.

"Do you think you can get my horse away from Ayyub?"

She nodded again.

"Go to it. Get him."

"Then?"

"I will do whatever I can for you and Kamarajes." It was weak, but Roddy didn't know anything else he could have said.

"Don't mind me," Kamarajes interrupted. "I'm a man without a country. I'll stay in Zakkum. I'm all right here, as long as I don't break the wrong rules. There's no such thing as circumstantial evidence in Arabia. If I'm not seen or heard, or don't confess I helped her to escape, no need to worry about me."

"Would they beat you to get your confession?1' Roddy asked him.

"On the feet, you mean? Not if I weren't suspected. Never mind me. Talk horse to her."

"How do you propose to get my horse?" asked Roddy.

"By a horse-race. How else? Winner-take-all is the rule in Arabia. The winner takes the loser's horse, and his bet too."

"You'll be the bet?"

She nodded.

"Don't you want her?" asked Kamarajes. That was a hell of a question to ask a man who was racking his brain for courteous evasions. But the girl came to Roddy's rescue:

"No," she said, "he doesn't want me. Can't you sec it?" But she showed no disappointment. Roddy knew that he ought to be glad she didn't.

"Is Ayyub mad?" he asked her. "If he knows the first thing about horses, he must know that mine can't be fit for racing for six weeks, not with the best trainer on earth. D'you mean he'll race him and bet on him?"

"Leave it to me."

"That's right," said Kamarajes. "Leave it to her."

"Damned if I get the hang of it at all," said Roddy. "Where do you live?"