RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

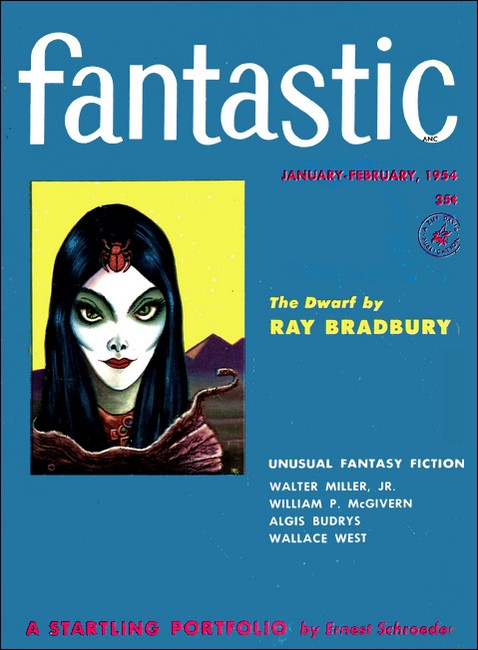

Fantastic, Jan-Feb 1954, with "The Odyssey of Henry Thistle"

If you've been poking around Larceny Lew's used car lot in hopes of picking up a bargain, we urge you to read this story before making the down payment. It wont tell you what to look for under the hood, but it'll explain why the mark of goat hoofs on the upholstery means satisfaction guaranteed.

WHEN the moon is new and rain clouds appear, they say in Arcadia there is sometimes to be seen, shimmering in the mist, flying low over the hills, an old model T Ford, with half a dozen (the number varies) sheep and goats standing on the seats.

This does not seem reasonable, and Dr. Drimmler, the local historian, has plainly said, "The point is, it was not a Ford at all." Truer words were never spoken, but in the interest of clear thinking everywhere, it may be useful to append further information.

It was Saturday noon in Arcadia, and scarcely a day for supernatural manifestations in the suburbs. The sun was hot, the summer air hung heavy with peace and pollen. From the courthouse tower the chimes were striking, faithfully, melodiously. They were a source of community pride; not a screen door slammed when the chimes played; not a lawn-mower mowed; cats yawned with care.

Henry Thistle could not have chosen a worse time to come rolling through the town square in his remarkable taxicab, accompanied by sounds that made one think of medieval warfare. Henry was very late, even for him, or decency would have brought him to a stop. As it was, seeing that traffic paused, he opened the throttle. This did not noticeably increase the speed, but it added a modern note—high C on a steam calliope—to the effect that was good for Henry's morale. Moreover, his passenger, Dr. Drimmler, bouncing in the rear, shouted encouragement for reasons of his own.

It was a mistake, not the worst Henry was to make that strange day, but a mistake. All one had to know was that His Honor, Mayor P.J. ("Carnivorous") Groatsby, who customarily enjoyed a midday snooze in his office, had come to a window and followed Henry's progress across the square with a small telescope.

Minutes later, the cab stopped on a shaded residential street. Henry jumped out and ran toward a large, ivy-covered frame house. An expert kick of his long legs got him over the hedge and into the flower bed.

"Is that you in the phlox, Henry?" Mrs. Beebe called from the porch.

Henry ran up, tracking fertilizer, in a panic. "Where is she? Don't tell me she didn't wait?"

"She said to meet her at the cake booth, unless she's rowing."

"Rowing? But I'm supposed to take her rowing! Am I responsible if Dr. Drimmler's car conks out and he hires me to take him around? Doesn't she appreciate the fact that I've been out all morning on errands of mercy, practically?"

"All Arcadia has heard of it," sighed Mrs. Beebe. "Henry, dear, with you so busy helping Mr. Drimmler, she had no idea when you'd—"

"But she knows the Doctor is due at the Fair and I'm taking him too! How late could I be?"

"I know, dear. I only meant to say that when the Bullwinkle boy offered her a lift, she accepted."

There was a horrible pause. "Bullwinkle?" croaked Henry.

"Would you like a glass of water, Henry?"

"Water?" It was amazing how much emotion he got into the word. "No, I'm fine," he said, and groaned resoundingly. "Just a little out of my skull with misery, that's all. Goodbye, Mrs. Beebe, and thanks... thanks..."

"Look out for the phlox, dear!" Mrs. Beebe called, too late.

"So?" said Dr. Drimmler philosophically when Henry told him. But he stopped there, and they rode on with neither talking, though they now shared the front seat, and with a minimum of noise from the taxi itself, which issued only a dispirited rattle. But presently there was a concerted honking of horns from behind, and a group of girls on bicycles passed. "Faster, Henry," suggested Dr. Drimmler.

"I'm trying, sir," said Henry, deep in gloom.

It was true, as the Doctor saw. The gas pedal was down to the floorboard, a recurrent condition which Henry usually explained as, "She's clogged, but she'll blow through." It was uncanny how this singular vehicle seemed to reflect Henry's mood. Not ten minutes earlier it had been positively frisky. Now, like Henry, it had lost its drive...

"Henry, if I'm going to judge the baby-diapering contest, we'd better get there before they run out of diapers."

There was improvement, but not much.

"Henry, you're too depressed. You must take hold. Life has its vicissitudes. This defeat may be temporary, a skirmish of no strategic value. On the other hand, in life, Henry, the girl does not always choose the nice young man who is working his way through college driving a hack all summer. Sometimes she chooses a nice young heir whose father owns the Bullwinkle Lumber Works. This is a test not only for you, but for Phoebe. You have a lot to offer. You have a strong character and a beautiful soul."

"Bullwinkle has a new car," said Henry.

"So? And that's enough to influence her?"

"A custom-made English racer, painted bright red, called a Crimson Siren, and cruises at a hundred."

"Hmmmm," said the Doctor, clearing his throat, and added, "Surely you couldn't be serious about a girl who decided her future on such a basis?"

"I could if the girl was Phoebe," said Henry.

"Did you say bright red?" asked the Doctor.

"Yes, why?"

"Is that it, on the other side of the traffic circle?"

"Right!"

The taxi suddenly shot forward, hit the curb, righted itself, and started rounding the curve with gathering speed. Fighting the wheel and the brake, Henry barely caught control as he exited from the circle, and managed a shuddering stop.

"Must've blown through!" cried Henry to Dr. Drimmler, who was almost beyond caring. Behind them the lights had changed, and the bright red car—with Bullwinkle and Phoebe in it—was approaching.

"Hi, Henry! Hi, Dr. Drimmler!"

Henry turned at her voice. The red car was alongside; it was the perfect shade for Phoebe's ash blonde hair; he was stabbed to see how at home she was.

"Hi, Doc," said George Bullwinkle genially. "Say, Henry, I hear you got the goat smell out of your cab. Congratulations."

Henry said, "Bullwinkle, I'm ignoring you for your own safety," and fixed his wounded gaze on Phoebe. "Your mother said you couldn't wait for me. I assumed it was because you were in a hurry to get to the Fair."

"Henry, honestly."

"We're both in a hurry," Bullwinkle broke in. With that there was a muffled explosion and a diminishing roar, and the English racer had reached a bend in the highway and vanished before Henry could readjust his expression. But readjust he did, and to the situation as well. Undaunted, he set out in pursuit.

The Doctor held on, the taxicab lurched and swayed. It was doing marvelously, making almost thirty miles an hour when it swept around the bend. There Constable Crouch came out on a motorcycle from behind a signboard and promptly flagged it down.

"What's wrong?" demanded Henry. It was the wrong tone to use on the Constable, but Henry's blood was hot with the chase.

"That's enough outen you," said Constable Crouch, writing away.

"What's this?" said Henry, stupefied by what he read. "Me speeding?"

"Yup."

"But I can't speed!"

"This here ticket says different," the Constable pointed out, refuting him. "You argue it out with Mayor Groatsby in court Monday." He grinned. "Wouldn't s'prise me if you're expected."

"Look here, Constable," said Dr. Drimmler, "there's no truth to this charge, and I'll testify to it."

"Why, sure, Doc! See you in court."

"Wait!" cried Henry. "If I was speeding, what about the car ahead of me? Why didn't you get him?"

"Well, now," said the Constable, "to tell the truth, I didn't b'lieve I could've caughten him." Henry stared, so did the Doctor, but Mr. Crouch was poker-faced; when no further questions were forthcoming, he got on his motorcycle, putt-putt, and went to find another signboard.

After a bit, the Doctor said, "Henry, we can't just sit here."

"No, sir," said Henry dully. He touched the starter. "This could mean a twenty-five buck fine."

The motor wasn't catching. "If there was a reason, some kind of reason." The starter seemed very weak. He checked the ignition and tried again. Nothing happened. The distributor—the gasoline gauge.

Henry turned slowly to Dr. Drimmler, but the understanding Doctor was looking toward the horizon he seemed unlikely to attain; better than most men he knew there are times when human agency is powerless, and only faith abides.

"I'll look inside," said Henry. "What's it sound like to you, Dr. Drimmler?"

"Kidneys," said Dr. Drimmler thoughtfully.

Henry dragged himself from the cab and opened the hood. After that, save for a tinkle of metal now and then, the serenity of the countryside remained undisturbed. The Doctor's eyelids flickered and he dozed...

This was the peaceful scene when Bullwinkle's car eased noiselessly to a stop abreast of the taxi. "C'mon, Doc!" he shouted. "We came back for you!"

The Doctor leaped up, startled, half out of the cab and half out of his skin. Henry clanged his head on the hood, then emerged and hung on dizzily to a fender.

"Henry," said Phoebe gently, "the committee asked George to help out. We told them you were coming, but when—"

"I know," said Henry, very quietly. "It's darned nice of old Bullwinkle... isn't it, Doctor?"

"Yes," said Dr. Drimmler.

He took his bag and changed cars. Phoebe had to press close to Bullwinkle to make room.

In a moment they had turned around and were gone.

HENRY was alone. The day had begun full of promise; suddenly

it was over. His girl was lost, his client was forfeit, a summons

for an impossible offence reposed in his barren wallet, and his

taxicab had ceased to function...

For all he knew, it had not only ceased, but deceased. He let his eyes wander over it with a feeling of love and pain, remembering all his hopes for it. "Son," the man who owned the junkyard had told him, "I don't even guarantee it's an automobile. It must've been something before its accident, but whether that was a gondola or a droshki I cannot say. It has an engine, which is a clue, but no engine would be better. And it has a mighty peculiar odor, as I see you've already noticed."

But Henry had not been dissuaded. He had scoured half the state to find something he could afford; a little more scouring, a paint job, an overhaul, some welding, some wiring, a part or two, and the Thistle Taxicab Company would be a reality. He had labored profoundly and given it his heart. Whatever ailed it, he oiled it...

It had repaid his devotion capriciously. A tear sped down his nose; it confused him; he was not used to self-pity, but there were few times in his life when he had been so low.

But now he perceived that the motor was running, making not a sound.

Yes, it was. The hood was open and he could see the motor, and the fan. Furthermore, Henry was by now in the correct frame of mind to comprehend that everything can happen. Now that he observed it, the cab was not only bouncing a little, but rocking, as though having turned itself on, it was preparing to undertake movement. Henry reached out to close the hood. The metal was vibrating at a prodigious rate, like a live, shivering thing.

He got into the cab and was not surprised to note that the dashboard instruments were not registering. Gingerly, he tried the gas pedal. The motor remained inaudible, but the whole frame seemed to flutter, gathering itself, eager. He put his hands on the wheel and all his fears fell away. Something wonderful, incalculably wonderful, was about to happen. He knew it.

Then he released the clutch and let her go...

THE Arcadia General Hospital was suffering a disturbance when

Henry regained consciousness. There had been a loud crash in the

adjoining room, followed by screams and shouts; they had brought

Henry to, but now it was quiet again. He stared at the white

ceiling and Dr. Drimmler's face hove into view, directly

overhead.

"...How do you feel, Henry?"

"All right."

"Do you remember what happened?"

"Speed," said Henry softly. "It was incredible... like flying." He closed his eyes. "Was the cab wrecked?"

"No," said the Doctor. "Tell me more about the speed."

"...I don't know." He frowned, until furrows seemed to force his eyes open again, but they were slits. "The motor started, all by itself," he said slowly.

"So? By itself? And then?"

"I wish I knew. Either I can't remember, or there isn't much to remember... just getting in, starting, and the terrific speed... like flying ..." He turned to look at the Doctor. "I'm not hurt, am I? I feel all right."

There was a shattering of glass in the room next door, after which a door slammed violently and a quivering silence was restored.

"I must see about getting your room changed," said the Doctor.

"What for? Where are my clothes?"

Dr. Drimmler gently pushed Henry's head back to the pillow. "Now, listen to me, Henry. An hour ago you were flat on your back, under a tree, and your taxi-cab was hanging from the branches by a rear wheel. Apparently you lost the curve at Tucker's Ridge and went over the cliff. You've had a miraculous escape, but the shock is far from haying worn off, and you need rest."

"...Tucker's Ridge," said Henry. "But the Ridge is maybe four miles from where I started—where Crouch stopped us—and the whole ride was over in a few seconds. How is that possible?"

"Just relax, rest."

"Where is my cab now?"

The Doctor sighed. "Forget the cab, Henry. You've had your last ride in it. The Constable was here. He told me Mayor Groatsby plans to condemn it Monday as a safety hazard." He rose from his chair. "Frankly, it may be just as well. I hardly feel you're emotionally equipped to handle that vehicle."

"Thanks," said Henry dully. "Just tell me where my cab is."

"Swanson's garage said they'd get it home for you."

"Home," Henry groaned, sick with guilt. It was the first time he had thought of home, and of his Aunt Lucy, with whom he lived; she had gone to Grahamsville for a weekend visit, but if the news reached her... "Does Aunt Lucy know about this?" he asked.

"No, I delayed calling her. Tomorrow, if all goes well, you can leave here and be home before she's back." The Doctor fumbled in his coat pocket and held out something to Henry. "Here," he smiled, "I'm told you were found with this lying on your chest."

Henry looked at the object without touching it, suspiciously. It was a crude set of reed pipes, bound with viny tendrils. "Not on my chest," said Henry. "No, sir."

"So?" Dr. Drimmler considered the disclaimer; reflectively he raised the pipes for a trial blow. The sound was ghastly, and he tossed the reeds to Henry in dismay and went to the door. There he paused, beaming. "I saved the best news for last. Get ready for a lovely visitor."

The Doctor had not been gone a moment when the door opened and a striking brunette came in. She had a magnificent figure; her clothes seemed to lag behind her as she approached Henry's bed.

"Dear boy," she said breathlessly, "so you have the syrinx?"

"What?" said Henry. "You must be mistaken. I don't have anything, I'm here because of an accident. If you—"

She wrapped her arms around him and planted a lingering kiss on his lips. "You'll tell me, won't you?" she murmured, and let him have another treatment.

This, thought Henry, was what it must be like to drown. It was wonderful. Gasping, he opened his eyes and looked deep into hers, as into pits where cold green fire blazed. An unmeasurable interval passed, then she sat up, and in the space that formed between them, Henry's somewhat blurred vision encountered Phoebe Bee be, standing in the open doorway.

"Monster!" said Phoebe. "Bluebeard!"

She whirled and the door slammed shut.

"Wait!" cried Henry, but it was useless; the dark girl had enveloped him again, and she was stronger than he. When she let go, he was numb. A roaring in his ears made it impossible to understand what she was saying; a word that sounded like siren kept recurring in her questioning, which meant nothing unless it meant Bullwinkle's red racer, and fear seized him as he realized she was getting set to kiss him again.

In desperation he blurted, "Bullwinkle has it!"

"Ahhh. But who is Bullwinkle?"

"George Bullwinkle... Sterling Drive..."

"Thank you," said the girl, getting up at once. "You see how unnecessary that embarrassing scene was?"

"Please go," Henry moaned.

She went, without a backward glance.

PRESENTLY, mustering strength, Henry climbed out of his bed;

his one thought was to get away, clothes or no clothes. He made

it to a window, opened the screen, and looked down with

disappointment to the hospital yard, five flights below; he was

thus engaged when Dr. Drimmler, a second doctor, and a male

nurse, dashed into the room, shouting entreaties not to jump,

until they grabbed him and carried him to the bed. His protests

were smothered, and he gave up resistance.

"It's only lipstick!" said the male nurse. "I thought he'd cut his throat."

Dr. Drimmler and his colleague regarded the exhausted youth with melancholy. "Just in time, Dr. Drimmler. He's obviously in a worse state than you suspected. Heaven knows what transpired here to have made Miss Beebe run by us in such tears, poor girl."

"He's talking, Doctor. What did you say, Henry?"

"...I said it was another girl."

The second Doctor bent over, alert. "Who was another girl?"

There was no answer. Henry looked confounded.

"Do you mean Phoebe?" asked Dr. Drimmler, gently.

"No, the one you sent here. She wanted Bullwinkle."

"I see. They all want Bullwinkle, is that it?"

"No, just this one. She kept asking about his car."

The two doctors exchanged glances. "Yes," said Dr. Drimmler, sadly, "they all want Bullwinkle, because of his car ..."

And a few minutes later, Henry's blanket was exchanged for a restraining sheet.

IT was dusk when Henry woke. The room was dark and still. He

turned his head to the right, to the left; no further movement

was possible. He lay there, thinking, listening to a distant dull

rumble of thunder.

A voice called; a man's: "You in there, can't you hear me?"

"Who's that? Who are you?"

"Never mind who I am, it's where I am. I'm outside your window. Will you open the screen, please?"

"I can't move."

"Too bad."

There was a scratching on the sill, then the sound of a screen being punched through, and footsteps bounded lightly into the room.

An indistinct form stood close to the bed. A match flared. In the small yellow light, Henry and his visitor looked at one another. Henry saw a diminutive man, with dark, creased, generous features. He wore a derby hat and a wing-collar and tie; a pair of patent-leather shoes hung around his neck, tied by their laces; a glimpse of a frock coat and a pale vest completed the vignette.

"You'll burn your fingers," said Henry, somewhat tardily, for the room smelled sharply of singed hair and barbecue.

The match went out. "Tied you down too, have they? What a miserable hospital; I was hours working myself free. I'm from next door. Are you the fellow I heard playing pipes this afternoon?"

"No, that was my doctor. Dr. Drimmler."

"Oh... Then he has them?"

"No, they're here—unless the wastebasket was emptied."

An oath, in a foreign tongue, but unmistakable, erupted in the darkness, after which Henry heard the wastebasket being emptied.

"I have them! What a relief!"

"I'm glad. Are they yours?"

"Yes, indeed." He had returned to the bedside. "I never thought I'd see this syrinx again. I'm deeply obliged. Is there anything I can do for you?"

Henry thought. "No," he said, and then, "You call those pipes a syrinx?"

"Not I, especially; the word syrinx means pipes. Why?"

"I didn't know. There was a girl in here asking about them."

"Was there! I knew it! A dark, ravishing beauty?"

"Yes, ravishing."

"I knew it!... You sent her to the Doctor, I suppose?"

"No, to George Bullwinkle."

"Who is he? Did the Doctor get the pipes from him?"

"No, it was all a mistake."

"Splendid!... But where did the Doctor get them?"

"He says they were found on me after I had an accident in my car. That's why I'm here."

"Because they were found on you?"

"No, because of the accident."

"I'm sorry. Nothing serious, I hope?"

"I'm not sure. They think I'm suffering from shock."

"Do they really? You sound clear as a bell. I'd stake my reputation on it."

"Even if I told you I think my car was flying?"

There was a pause. "...You're joking."

"No. That's the trouble."

Again a pause. "...I can't believe it."

"No one can."

"I didn't mean it that way. Oh, I believe you, believe me! I must have a look at that car! Where is it?"

"It's home by now. We have a sign out front: Lucy Thistle— Antiques."

"I'll never find it. I always lose my way; I start out to go somewhere and end up deep in the woods. Will you come with me?"

"How?"

"Forgive me." The little man began to attack the restraining sheet with great energy. Just as he completed his task, there was a sound of a key in the door. "Quiet," whispered Henry's benefactor, and tip-toed swiftly across the room.

The door opened. A shaft of light fell into the room, and so did a male nurse as the little man bashed his head with a shoe. The door closed. The little man returned to find Henry standing. He took his hand and guided him.

"But the door's that way," said Henry.

"The window, I think, is safer."

"We're five stories up."

"You needn't worry, I'll carry you on my back. I'm very sure- footed, and strong for my size. Here, get on. Bend your knees a bit more, please." Quickly, he mounted the sill and thrust a leg out the window. "Close your eyes."

Henry had already done so...

He felt a fresh wind against his cheeks. There were voices and motors to be heard below, and from far off, reverberating thunder. The descent was steady, astonishingly swift. When Henry's dangling feet touched ground, he sank to his knees and breathed again.

They were in the hospital yard, in a landscaped border close to the building wall, hidden by firs and shrubs. The little man sat beside him, putting on his shoes.

"Let's borrow a car," he whispered. "Pick out a good one."

TEN minutes later Henry drove an ambulance into the Thistle

driveway; his friend and he had rushed it, unaware, and their

unhappy discovery had come too late to turn back. Fortunately,

the neighboring houses were blacked out for television, their

occupants in a trance. The Thistle back yard stood deep in

shadow, surrounded by sycamores.

The garage was unlocked (it had no lock), and the taxicab was inside, right side up.

"Can you turn on the lights for a moment?"

"I have a flashlight," said Henry. He found it in a tool chest. "You take it. My hands are trembling."

Henry's friend played the beam of light over the cab. Everything was in order, even the tires; save for a dented fender and some pussy-willow in the radiator, it had come through unscathed. The condition of the motor was a question, perhaps, but the motor was not new and neither was the question.

"You've made changes," said the little man. "Some good ones."

"Then you knew this car before I bought it?"

"Long before. It's quite old. That's why I believed you... I know what this car can do..."

"We'd better not have any more light showing here."

"In a moment."

The little man climbed into the cab and continued his inspection. Henry came closer to watch. The night was growing damp; he was anxious to get into the house for some clothes, but the little man was now rummaging under the rear seats.

"Are you looking for something? Can I help you?"

"I doubt it." He moved a door handle, then reached down and slid open a door compartment previously unknown to Henry. "I'm trying to find out why she's so intent on locating this car."

"Who?"

"Diana," said the little man. He tried the other door. "You know— the girl who asked about the syrinx." He opened a second mysterious recess and let out a cry.

"Letters!" Out came a dusty packet of envelopes, tied with faded red ribbon. "Here, hold the light for me, please!"

Henry obeyed. His friend opened a letter, scanned it with exclamations of joy, then opened a second, a third, and laughed triumphantly. "They're love letters! Can you imagine what her love letters are like? No wonder she's so hot for this chariot! Love letters!"

Henry switched off the flashlight. "I don't understand."

"Very simple. Your taxi used to belong to Diana's brother; he and I don't hit it off, so I borrowed the car without his permission. There was a wreck. Naturally, I had to abandon it. Then I realized I'd left my syrinx in it, and I couldn't find the car again—I never seem to pay attention to where I am—and soon the news leaked out. Diana's been hounding me to locate the wreck ever since. I suppose you heard her smashing up my room in the hospital? Hardly gracious behavior, after she'd put me there. But this makes everything worth—"

Henry broke in. "Listen!... Sirens!"

"Yes. They're coming this way."

"It's the police. We're caught."

"Not a bit. Get in, I'll drive. Not the ambulance—here!"

"But it may not go!"

"Hold fast."

"The garage doors!"

"Too bad."

They came out of the driveway and turned into the street on two wheels; the rear ones; a police car, screaming down at them, swinging a fearful red spotlight, never even saw them pass.

Henry's taxicab was flying again.

They were not very high up, a few hundred feet perhaps. After a while, Henry was used to it. Overhead, the moon was a mere sliver, but brilliant stars filled the sky, the hills sparkled with light, streams and valleys shone. The countryside lay nightbound, silent. A nocturnal bird winged by.

"Your teeth are chattering. Do you want my coat?"

"No, thank you. I don't mind. I feel... I feel..."

"I know."

They flew on. Presently, the little man took out his syrinx and began to play. Henry listened enchanted. The music rose and fell, gay and pensive by turn, melody such as he had never heard. When it ended, Henry felt uplifted.

"Did you notice?" asked his friend. "Driving no hands?"

"Yes."

"...Shall I take her down?"

"Yes, I suppose so. I've been thinking."

"So have I... What are your plans?"

"Confused. It won't be easy, clearing myself. Which reminds me—about the letters ..."

"You want copies? I'll see to it."

"But there's a rule. Articles found in taxicabs must be turned over to the police. I'm willing to stretch a point with your syrinx; I didn't find it, for one; and after hearing you play, I can't imagine it belonging to anyone else..."

"You're very kind."

"...But I'm in enough trouble as it is."

"I understand. It desolates me. Still, I do have my pipes back, and I'm grateful. Here are the letters."

The little man got out, and Henry saw that they had landed in a meadow. "Do you think you can handle her yourself now?"

"I'm sure of it," said Henry. "Can't I take you somewhere?"

"But we are somewhere. This is fine."

Henry watched his friend walk off across the dewy field. The last he saw of him, he was throwing away his shoes...

THERE were lights in several rooms of the Beebe house. It made

Henry's task more difficult. He hovered some feet above the

weather-vane, suspended in doubt. Calling in hospital pajamas was

bad enough; it would not help matters to land on the roof. With a

sigh of regret, he eased his taxi down into the flower bed.

It was but a step from the radiator to the porch. He rang the bell, hid behind a rattan chair, and waited for the door to open.

"George?" The porch lit up and Phoebe came out, a vision in white. "George, behave yourself. Where are you?"

"Turn off the lights. This is Henry."

She started, then retreated, a step at a time; then leaned weakly against the door and reached in for the light switch.

Henry emerged. "Phoebe, I got away from the hospital."

"Yes, I—I heard..."

"I want to explain everything."

"You must go back... Will you go back?"

"Phoebe?" her mother's voice called from within. "I'm bringing in the punch-bowl. Is that George with you?"

"No, mother," and after a slight hesitation: "It's Henry."

"Well, isn't he going to come in?"

"Mother, do you hear me? It's Henry... Henry."

There was a watery crash, then silence.

"Why doesn't your mother say something?"

"...W-what would you like her to s-say?"

"I hope you're not thinking of calling anyone—"

"Henry, you mustn't feel persecuted. We're your friends."

"Because they can't catch me. If they get close, I'll fly off."

"Of course. What else?"

"I don't like this. You're so agreeable. Aren't you still angry about that girl in the hospital? I'll tell you something: she's with Bullwinkle right now. I saw them on my way here, so there's no use waiting for him... Why are you backing away?"

"Henry, I don't doubt—Henry, if you dare—Put me down!"

But Henry was running across the porch, with Phoebe slung over a shoulder, kicking and screaming. He climbed the rail, leaped nimbly, and landed sprawling in the phlox. A moment later, with Phoebe on the seat beside him, Henry's taxi burst through the hedge and went wheeling down the road.

He was not sorry, Henry told himself. His resolve had not faltered; it was time he had done something constructive. And Phoebe would concur heartily, he knew, as soon as she got over her hysterics.

"...Phoebe, it's a beautiful night ..."

There was no comforting her. Even promises not to fly, unless it became absolutely necessary, had been useless (though it seriously hampered his search for Bullwinkle), and explanations were proving more intricate than he had been able to foresee.

"Phoebe, that girl wanted pipes that belong to a friend of her brother's. He owned this car, but the friend wrecked it and left his pipes. The girl wanted to find my car because she had some love letters in it. That's clear, isn't it? So I said Bullwinkle had the pipes, because I thought she meant his car, and now they're out driving and she'll vouch for everything when we find them. All right?"

She only sobbed again. But presently, as he drove on at reduced speed, and the cab's swaying diminished, she stirred and sat up a bit. Her tear-stained face looked up at him, tender, compassionate. "Henry, I want to help you... Does it help if I say I believe you?"

"Do you really?"

"Yes."

"And you're not afraid anymore?"

"...No."

"Good. Because you know what?—I'm sure I hear the Constable behind us on his motorcycle, and now I'll let him catch up."

"Dear, sweet Henry, you're doing this for me?"

"For you, Phoebe. Watch me run him right off the road."

It was heart-warming to feel her slide closer, her head nestled against his shoulder (he had no idea she had fainted). His attention was divided between the dark, unwinding road and the motorcycle. It was running without lights, approaching in tentative spurts, disarmingly. When it drew even with the cab, there was Mr. Crouch, with a remarkably fiendish grin.

"H'lo, young feller, feelin' better?"

Henry nodded modestly and went faster.

"Never mine that. Pull over!"

Henry shook his head and kept accelerating.

"'Course, I could plug you," said the Constable, staying alongside, "if I was sure that there girl is dead. Strangled 'er, maybe?"

Henry smiled mysteriously. The wind rose to a furious whistle.

"I'm warnin' you! I'll plug them tires!"

They were doing seventy. When Henry let the car out again, they passed eighty, and the Constable stopped trying to get at his gun. Once more the motorcycle crept up. Henry leaned over the cab door, chin on his clasped hands, waiting for the Constable to see him. When it happened, the look on Mr. Crouch's face was rewarding. Henry laughed so hard he kicked the gas pedal. The taxi rocketed up a hill, reached the summit and kept going—and there it was, flying again.

"Phoebe, look! This is just how it happened the first time!"

She flopped over, alarmingly limp. He propped her up on the seat. Apparently (he decided) the excitement of being airborne had overcome her. But the worst was over; the abundant fresh air was sure to revive her soon, after which, seeing that they were safely aloft, she would relax...

But shortly afterward, Henry spied Bullwinkle's racer. The powerful headlights were unmistakable. It was proceeding at a fast clip along an old country highway, a serpentine asphalt strip in large disuse except among motorized lovers and the hot rod set. In a way it was disappointing to have come upon him so quickly; Phoebe had been stirring again, and Henry was anxious for her conversion. But there was business to settle, and if Diana was still with Bullwinkle, delay seemed foolhardy. The weather was changing fast; scarcely a star was to be seen, and the updrafts were increasingly turbulent.

The cab descended by degrees until Henry saw a promising stretch, then it touched and rolled.

"Hey, Bullwinkle, stop!"

Diana was there. Neither she nor Bullwinkle reacted to Henry's materialization with visible joy; Bullwinkle, in fact, with horror. Instead of stopping, he pulled away sharply—but only for a moment before he was overtaken—and his continuing acceleration was matched with ease. The taxi was incontestably faster. As this became evident, Bullwinkle's consternation mounted, and so did his speed, each compounding the other, and by the time the two cars passed the new Freeport cutoff, still abreast, they were traveling at something over a hundred miles an hour.

THERE the race ended. Helplessly, Henry watched another hill

roar down on them. With a sinking feeling he realized he was

flying...

Anxiously, Henry hovered a mile or so farther along the road, but Bullwinkle did not come. Henry had lost sight of him and sailed over the valley to wait. A strange sound came. He froze attentively. Presently, with some disgust, he identified the distant striking of Arcadia's relentless courthouse chimes. Bullwinkle had either turned back or cut off his lights and gone into hiding.

He began to circle back, getting enough altitude for a panorama, and rose over the hill that had launched him. He saw a beam of light slanting up into the murky sky. It rose like a beacon from a cornfield bordered by the road, and Henry knew it was one of Bullwinkle's headlights.

At that instant, the heavens opened. A bolt of lightning covered the horizon, a tremendous white band, its core a bright copper, its edges lined with violet. There was a great, hissing sound, and then a mighty clap of thunder that shook the earth and the air, and said to sinner and saint alike: "Look out, brother!" The rain came down like a waterfall.

Down plummeted the taxi in a maneuver that jarred Phoebe back to consciousness, then slammed her against the windshield and knocked her out again.

Henry landed close to Bullwinkle's overturned car. It lay among mangled cornstalks; a torn and twisted crop, now hammered by the rain, traced its career from where it had left the road. Bullwinkle had been thrown some feet away. He scarcely seemed to be breathing. There was no sign of Diana, no clue to her fate, and no time to be lost. Bullwinkle was badly hurt, and Henry's duty was appallingly clear.

"WELL, sir!" said Constable Crouch, thus eloquently conveying

his pleasure as still another newspaper photographer took his

picture. The Arcadia General Hospital ordinarily took a dim view

of flash-bulbs on its premises, but turmoil had relaxed the

rules. Refugees from the cloudburst crowded the waiting rooms and

corridors, their interest less in the great storm outside, now

abating, than in the storm within. In the lobby, a morbid swarm

hung on the Constable's evaluation of each new rumor that buzzed

down from Surgery Five. Between pronouncements, he posed for

shots to be captioned "VIGILANT HERO" and furnished reporters

with the harrowing details of "HIS ENCOUNTER WITH A MADMAN;

'SUPER-STRENGTH' NO MYTH, HE AVERS."

They scribbled away, sick with wondering whether the disrupted telephone service, now accepting only emergency calls, would be restored in time to get the whole magnificent mess into the Sunday crime supplements.

"Let's check, Constable, we newspapermen have to be right. The two boys had a feud over a girl. Thistle lost out, tried to kill himself. Instead he had an accident that apparently deranged him. He conked an attendant, bust out of the hospital, stole an ambulance, got to his taxi, kidnapped the girl, and tried to kill everybody by crashing Bullwinkle's car. Okay? Okay. Now, what made him come back to the hospital with Bullwinkle and the girl?"

"Just didn't know what he was doin'."

"And how did you happen to be here at the hospital?"

"Had 'im figgered. Just say that. You got the part where he jumped me with the fire axe?"

UPSTAIRS, Henry listened to experts and said nothing. He sat

quietly in a chair, arms folded across his chest stoically,

albeit wearing a strait jacket. It was not needed. Henry's only

demonstration of super-strength had been his staggering entrance

to the hospital, utterly soaked, streaked with gore, carrying

Bullwinkle. With his burden transferred, he had allowed himself

to be led away, silent and shivering, and put under guard.

(Constable Crouch's role had been less glorious than his account

of it, consisting of an arrival ten minutes later, a brief

audience with the prisoner, and the announcement that he was

under arrest.) Henry wondered what would be done with him, but

his speculations were contradictory, like his interrogators.

They were debating Henry's refusal to answer the last question; what caused it; how this differed from his refusal to answer any of their previous questions; whether this called for a new approach; and whose; and the dangers of each other's diagnosis. They included a dietician, an anesthetist, two opposed physiotherapists (like, book-ends), a glandular theorist, a nature faker, and a dental mechanic. The healing arts had not suffered such a setback in Arcadia since an epidemic of athlete's foot some years before.

Mercifully, the gentle pitter of the rain and the patter of the experts lulled Henry to sleep. When both ceased, he came to slowly, and found himself alone with Dr. Drimmler.

"...Henry, will you talk to me?"

"Yes, Doctor."

"Thank you, Henry... I'm here to help you, Henry."

"Yes, Doctor."

"You understand everything, don't you, Henry?"

"Yes, Doctor."

"Henry, if we play our cards right, we can have you held for observation and work our way out of this later on. It may take a few weeks, but they have movies every Wednesday and the billiard table is a beauty. Do you understand, Henry?"

"Yes, Doctor."

"Otherwise, it will go hard with you. The charges against you include theft of an ambulance, endangering public safety, speeding, reckless, driving, resisting arrest, kidnapping, attempted vehicular homicide, and in the case of the male nurse, assault with a deadly weapon."

"I disagree, Doctor."

"In what way?"

"He was hit with a shoe, and a shoe is not a deadly weapon."

"But you had no shoes."

"The man who had the room next door had the shoes. He wore them around his neck. Later he threw them away."

"I see. How did you get out of the hospital?"

"He carried me down the side of the building into the street."

Dr. Drimmler sat and thought for a few moments. At length he nodded and remarked reassuringly to Henry, "The billiard table is a real beauty." He took out some paper and a pen. "Tell me the whole story in your own way. It may have some weight as evidence."

"Yes, Doctor," said Henry, in a whisper. For some minutes then he spoke, his voice at a dead level, his eyes unnaturally bright. He said what he had to say plainly, but toward the end he was growing angry, as if his recital had finally convinced him that it was hopeless.

"...I can't prove most of this. Phoebe was in a faint. This other girl, Diana, who was with Bullwinkle, and disappeared... If she could be found, she'd testify I had nothing to do with Bullwinkle's accident. I must've been a couple of miles away when it happened."

"Because your taxicab was flying," the Doctor nodded.

"Yes," said Henry wearily, "I remember I lost him at the Freeport cut-off ... I was waiting for him..." His voice died and suddenly he looked up sharply and asked, "Dr. Drimmler, what time did the storm begin?"

"Why do you ask, Henry?"

"Because I remember hearing the courthouse chimes. I couldn't count them, so I don't know what hour they struck, but the storm began about two or three minutes later."

"It was shortly after nine o'clock."

"All right, Doctor! Bullwinkle's car crashed near the cut-off. It's still there, almost fifteen miles away. Now check up on the time the hospital entered Bullwinkle. It couldn't have been more than ten minutes past nine—so how do you explain my getting Bullwinkle here, from fifteen miles away, in six or seven minutes?" He sat triumphantly, staring at the Doctor.

"But you see, Henry," said Dr. Drimmler gently, "this depends on your claim that you were fifteen miles away when you heard the hour being struck... Never mind, we'll claim it; it can't hurt."

"One thing more," said Henry. "I still have those love letters."

"Those love letters, so? Where do you have them?"

"In my pajamas pocket, under this strait jacket."

"And you want me to unfasten the strait jacket?" The Doctor let a sigh go and shook his head. "Henry, I'm sorry," he began, but there was a knock on the door and he went to open it.

It was the glandular man and the dietician. "We heard talking."

"Yes," said Dr. Drimmler. "Is there any word from Surgery?"

"Only that the boy requires further transfusions. They can't understand how he didn't bleed to death from his wounds. Apparently he was fortunate the accident didn't happen too far from the hospital."

"...Yes," said Dr. Drimmler slowly. "Thank you, gentlemen."

He closed the door and turned around and looked at Henry for a long, long, intolerable minute. Then he went out.

When Dr. Drimmler returned, his face was ashen. Without a word he went to Henry and began unfastening the strait jacket. As Henry's arms came loose, a packet of letters fell out from his pajama coat. The Doctor picked them up. They were a sodden, inky, pulpy mass, but the Doctor was not disappointed. He put them into a small bag and began to massage Henry's arms.

"Listen carefully," he said in a hushed voice. "We have only a minute before they post armed guards here. George Bullwinkle is sinking fast. The hospital is almost out of his blood type. The nearest available supply is at Glen Falls. That's thirty-five miles from here, and the roads and most of the bridges on the way are washed out. Can you fly your taxicab there and back?"

"I don't know."

"Will you try?"

"Of course I'll try. Where is my cab now?"

"Come with me. It's still out in the yard where you left it."

"But how—"

"Shut up!" said Dr. Drimmler impatiently. "Do you expect me to climb down the wall with you? You act as if you'd never heard of a laundry chute."

HERE, as it happens, our story ends.

"One can ruminate' endlessly about such matters," is what Dr. Drimmler says, "but those who are interested will find everything set down in the history I am writing. The known facts, certainly, are very intriguing.

"Let us take, for example, the identity of Henry Thistle's next door hospital neighbor. We know he was registered as Mr. Safunu—a strange name, which someone has pointed out, is an anagram of the word Faunus. We know also that he wore his shoes all the time he was in bed, refusing to let either doctors or nurses to look at his feet. We know also that he was admitted to the hospital as the result of being wounded—is this not strange?—by an arrow.

"We know also that the name Diana has certain mythological references to a goddess who hunted with bow and arrow. In mythology, the brother of Diana is Apollo, and Apollo was the owner of chariots that outraced the sun. Interesting, is it not?

"And for those who care to pursue these researches, it should be pointed out that the god Pan, also called Faunus, was happiest of all in an ancient haunt of his called Arcadia. A nice coincidence.

"Yet all this means nothing, unless it is remembered that Henry Thistle did get to Glen Falls and back in half an hour, which undoubtedly saved George Bullwinkle's life. To support this we have signed affidavits from various hospital officials, from the Mayor, from ex-Constable Crouch, and of course, from me.

"Other testimony is available also from Mrs. Phoebe Thistle.

"Still more testimony, of another sort, may be had from the great philatelic houses that have since bought several of Henry Thistle's extremely rare and valuable stamps—stamps which I can identify as having been on the letters, the love letters, that figure in the story. These ancient stamps, some of them two hundred years old, are worth looking at, and lend great dignity to Miss Lucy Thistle's Antique Shop.

"It is unfortunate, perhaps, that the taxicab itself disappeared during the following night, and has never been seen—except, of course, by those who claim they have glimpsed it when the moon is new and there are rain clouds. The sheep and goats on the seats... well, who can say?...

"But an old model T Ford? Nonsense. It was not a Ford at all."