RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's

death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

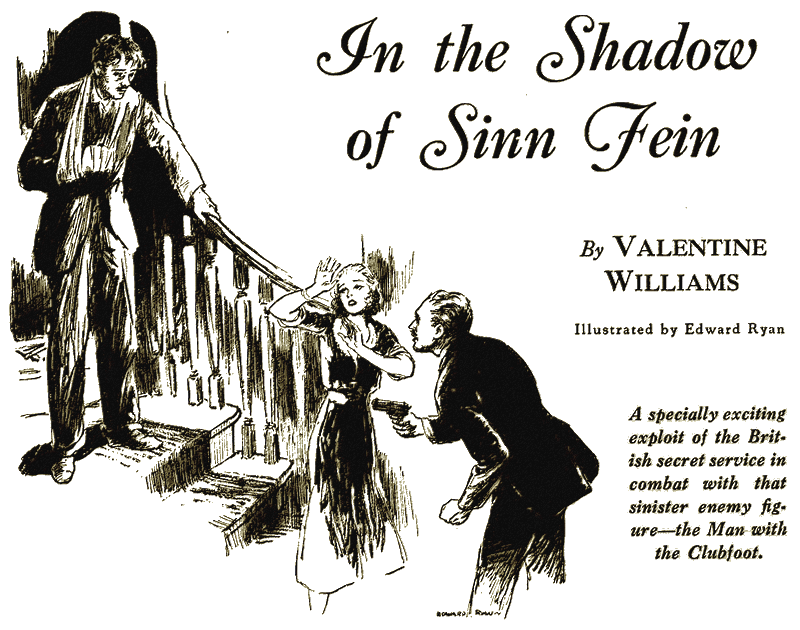

Blue Book, March 1932, with "In the Shadow of Sinn Fein

At the head of the stair stood a young man,

wan and unshaven.

"I'm Regan," said he. "You can l'ave her out of it."

A specially exciting exploit of the British

secret service in com-

bat with that sinister enemy figure-the Man with the

Clubfoot.

I HAD not been in the room a minute, I suppose, when the disaster happened. One of the windows was open at the bottom and the breeze must have slammed the door. The clatter of some metal object bouncing on the floor followed the bang. The door-handle, decayed with age like everything else in that gloomy house, had come apart. One knob lay on the carpet within the room; the other, together with the lever controlling the bolt, had dropped out on the other side.

I was locked in.

Frantically I pawed the flat surface of the door. In vain, with fingers thrust into the hole where the handle had been, I tugged. The lock held fast. The door, like the doors in most of these old Dublin mansions which have not been raided by the antique dealers, was of solid mahogany and opened inward-no chance, therefore, of breaking it down.

I turned to the window. But I had reached the second floor in my stealthy reconnaissance of the premises, and the bedroom in which I found myself-the girl's bedroom, obviously, by its furnishings-faced the Square. Even had I been willing to risk escape by the window in full view of the street, there was no rain-pipe or other convenient foothold to facilitate my descent. I was in a nice fix. The fact that, so far as I had been able to ascertain, the house was empty simply postponed the moment of release-and of exposure. What explanation was I going to give of my presence there? Unpleasantly mindful of the area window gaping below, I cursed the insensate vanity which always prompted me to play a lone hand. Of course, I should have reported to Intelligence Headquarters at the Castle on my arrival in Dublin an hour before and begged the loan of a brace of plainclothes-men to accompany me. Here I was, trapped in the heart of the Dublin slums, where I could have my throat cut and no one a ha'porth the wiser-a British Secret Service man, I realized, would get little mercy from the summary justice of Sinn Fein.

The hum of the city mounted to me out of the warm September evening as I sat on the bed and cast my mind back over the circumstances of my mission. Out of the blare of bands, the shouting of crowds, the turmoil of the recruiting-stations, that marked the early days of the war, a whisper,-a sheerly incredible whisper,-had drifted into a certain carefully segregated Whitehall office.

To you who read these random recollections of mine, the Man with the Clubfoot is today no more than a name. He is but another phantom-a symbol, if you will-of that dead and vanished Europe that plunged the world into war. To us of the British Secret Service, however, the shadowy, elusive figure of the German master spy was a real and constant menace. Dragging that misshapen foot of his after him, Dr. Adolf Grundt, to give him his real name, hobbled from capital to capital at will, his appearance almost invariably presaging dark and inscrutable happenings.

"Clubfoot is in Ireland"-the rumor found its way like a

chill breath into the little room where, behind blinds drawn

against the September sunshine, the Chief, stolid and

impenetrable, pored over his files. At that time only three of

us had ever met Grundt face to face; of these, Francis Okewood

was somewhere in Germany, swallowed up in the fog of war, and

the other, Philip Brewster, was away in invaded Belgium.

I was the third. To me, accordingly, the Chief showed the report from Intelligence, Ireland. It was vague enough-merely three links in an intriguing and disconnected chain. Voices speaking in German after dark on a Kerry beach and the sinister silhouette of a submarine off the shore-link the first; as the second, the appearance in Dublin of a burly, lame individual of foreign stamp in company of well-known "strong arm" Sinn Feiners; and, link the third, a passing glimpse caught by a British informer in Dublin on a rainy night of one Larry Forde, a notorious gunman, the same limping stranger at his side, standing irresolute on the front steps of the self-same house in which I now found myself.

We were fighting the Germans, not the Irish, I reflected; but from my recollections of my soldiering days in Ireland I was not sure that the Castle would take that point of view. Clubfoot was my quarry; Intelligence, Ireland, could look after their Larry Fordes. In giving me carte blanche to handle the investigation, the Chief had stressed the danger of scaring Grundt away before we ascertained his business in Ireland. Rather than trust my old antagonist to the official net, I resolved to start in on my own from the only point of departure we possessed, the house in Mountjoy Square, once the aristocratic quarter of Dublin, but now given over to tenements. Against the tenant-a certain Mrs. Meehan, the aged widow of a Dublin solicitor, who occupied the house with her granddaughter-nothing apparently was known.

A light step on the landing brought me instantly to my feet. I heard a muttered exclamation, then the sound of the broken lever being refitted in the door. I glanced wildly round for a hiding-place, saw only the bed and, as an alternative, some garments hung on hooks against the wall. But I was too late. Before I could move the door had swung back and a girl stepped quickly into the room.

Ireland is full of lovely girls, whose natural charm is enhanced by the spontaneity and modesty of their air. The girl who confronted me had the beauty and freshness of a rain-washed flower, with eyes so blue and deeply fringed as to make a man's heart miss a beat, the complexion of a rose-leaf, and a milky white skin that set off the raven sheen of her hair. She was neatly dressed, though the serge frock she wore was neither fashionable nor new. But she carried herself with a proud little air that made you forget her clothes.

She was not frightened-many of the Irish have no sense of fear-though her face wore an anxious look as she said quickly, with an Irish lilt to her voice: "And what may you be doing there?"

She was of the better class of Irish and in those days the bulk of enlightened opinion in Ireland was still with us in the war. I made up my mind to take this girl into my confidence.

"I'm an Intelligence officer from London," I told her, "and I'm looking for a man who, the night before last, was seen ringing the doorbell of this house."

Her eyes were suddenly apprehensive. "But how did you get in?"

"I must apologize for the intrusion," I said. "But I couldn't get an answer to my ring. So, as the kitchen window was open-" Then, as she flushed with anger, I added: "This man's a dangerous German spy."

"There's none of his sort in this house," she cried. "I live here alone with my grandmother. What would Gran and I be wanting with German spies? You'd best be taking yourself off!"

"Do you know anyone called Larry Forde?" I questioned.

"And what if I do?"

"It was he who brought this man to your house two nights ago."

At that she blenched. "Two nights ago I wasn't here," she faltered. "Who is this man?"

"His name is Grundt-he has a clubfoot."

Now fear, naked and unashamed, overcame her. She was white to the lips. "You know him?" I persisted.

She laughed uneasily. "Faith, and how would I be knowing him at all? On Wednesday night, you say it was?" She shook her head firmly. "On Wednesday night the house was shut up."

"And your grandmother?"

"Gran's in the hospital-" She broke off abruptly. Her "Listen!" was a staccato whisper. A man's voice, calling, floated up the stairs. "Sheila, are you up there?"

She flashed me a rapid glance, then, quick as the thought itself, lifted one of the garments that hung on the wall. "Behind here," she bade me. "And for your life don't stir!"

A hurried footstep rang hollow on the stairs as I flattened myself in the alcove, spreading out a wrapper suspended on its hook to cover me. A man's voice cried with a rich brogue: "Sheila, where the blazes have you been hidin' yourself?" The speaker was in the room now, his voice lowered. "Did you see Tirence yet?" The question was barely audible.

"Terence?" she repeated in the same tone. "Yes, he's back," was the excited rejoinder. "D'you mane you didn't hear?" And then my ear caught a ponderous, halting step mounting the stairs.

In a raucous, hurried whisper the brogue rustled on: "There's one lookin' for the boy. They came over t'gither but got separated in the dark. I made sure Tirence would be here. The other I put away under cover, the way he'd be safe till we could meet up with you-twice we've been to see you, but we couldn't make any one hear. If the kitchen window hadn't been open just now-"

"Gut efening!" a guttural voice cut across the hurried undertone.

I heard the tap of a stick, the clump of a dragging foot, and realized that Grundt-Grundt-was there in the room, within but a yard of my hiding-place. "Well," he snarled, "where is he?" A pause. "You told me we should find him with the young lady."

"He's not here," said the girl.

"Gott im Himmel-I risk capture, death, even, to bring him to Ireland, and no sooner do we land than he deserts! Is this your Irish good faith?"

Pressed back against the wall, with the wrapper clutched tight about me, I had been drinking in every word of this conversation. Unconsciously I must have pulled too hard upon the flimsy fabric of the kimono: at any rate, at that moment, with a loud rending noise, the wrapper split on its hook and fell in a bundle about my arms so that I stood disclosed. "Herr Gott!" cried Clubfoot. I had a pistol, but his automatic already had me covered.

The wrapper split, and I stood disclosed.

"Herr Gott!"

cried Clubfoot... His automatic already had me covered.

His companion had swung about. "Who the devil's this?" he demanded, with a waspish look at the girl.

Her eyes, blue as the Kerry hills, implored me. "Troth, and you may well ask that, Larry," she declared. "I never clapped eyes on him before."

But now Clubfoot chipped in. "You'd trap me, would you, you Irish scum?" he roared. "Turn about and face the wall, the lot of you, and put your hands above your heads!"

"I declare to God, Docthor-" Larry began. Then he rounded on me. "Who are you?" he snapped.

"His name's Clavering, an old acquaintance of mine," the cripple said. And with sudden ferocity he added, "A British secret agent."

"A British-" The youth came at me. "A trap, is it?" he vociferated. "I'll let the daylight into that one if it's the last thing I do-"

At that instant a thunderous knocking resounded from the hall below. "Secret Service men," Clubfoot whispered hoarsely. "I might have known!"

Larry's pistol was pressed against my chest. "You can say your prayers, me bucko!" he muttered.

But Sheila pulled his arm away. "Is it crazy ye are?" she cried. "Can't you hear them? They're in the house!"

Feet were tramping on the lower floors. "Lord save us, I forgot that open window!" Larry exclaimed.

"Out through the back-you know the way!" the girl urged him. "And take him with you!" With that she fairly bundled them out of the room and, withdrawing the broken door-handle behind her, imprisoned me again.

A MINUTE or two later two plainclothes-men, gun in hand,

released me. The girl, Grundt and Larry had disappeared. To a

dapper individual in mufti who was on the landing, I showed my

credentials. He was one of the Dublin Intelligence staff and

told me he was looking for a certain Terence Regan, believed to

have been landed a few nights before by a German submarine.

"To blazes with Regan," I cried. "The man who brought him from Germany-the head of the Kaiser's secret police-left this house by the rear not three minutes ago. He can't be far away. Come on!"

My colleague told off two of his men to remain behind and search the house; then, in a pack, we streamed out, five of us, through a neglected yard and over a wall into a labyrinth of mean streets and courts and alleys.

The party spread in all directions and presently I found myself alone. It occurred to me that my friend Larry, no doubt knowing the neighborhood like his pocket, had secured all the start he required. I made my way back to the house.

One of the detectives who had been left behind greeted me at the yard entrance. "There's ne'er a living sowl in the place, sorr," he told me. "The other chap, he's guardin' the front an' I'm waitin' here for the Major..."

I had left my hat in the bedroom, and went upstairs for it. Unconsciously, I suppose, I trod softly and in the silence, as I gained the upper landing, I heard a door creak. I drew back behind the balustrade and waited.

It was Sheila. I stepped out and confronted her. Her dismay was pathetic. But she faced the situation bravely. "Listen," she said, "back there, but for me Larry would have had your life. Show your gratitude now by going away and forgetting that you've ever seen me."

"And Regan?" I questioned. "He's in hiding here, isn't he?"

"No, no!" She wrung her hands.

"I'm sorry," I said; "but I'm going to see for myself."

I made as if to pass her, but she sprang back and barred the way.

I shrugged my shoulders. "The police are still downstairs," I warned her.

Then a husky voice called "Stop!" A pitiful object stood at the head of the attic stair, a young man in mud-stained clothes, wan and unshaven, one arm in a sling.

"Oh, Terry, Terry," the girl wailed. "Why did you do it?"

"I'm Regan," said the young man. "You can l'ave her out of this-d'you hear?"

"He meant no harm," the girl broke in. "He only wanted to come home to be with me!"

"I was in Berlin on an engineerin' job," Regan explained. "When the war came, the Germans interned me. Then they asked round the camps for an Irishman to go to Ireland on a special mission and I sent up my name. God knows, I want Ireland to be free, like anny other dacent man does, but sure a blind man could see the Germans care divil a bit about the Irish. If I volunteered to go, 'twas only I couldn't bear the thought of bein' separated for months, for years, maybe, from Sheila here-"

"And why wouldn't you be telling him the truth, Terry?" the girl struck in. "Isn't it my husband he is?" she said to me, coloring hotly. "And soon there'll be a baby. We were married secretly on his last leave, because Gran wouldn't hear of my marriage, she being old and afraid of being left. Oh, for the love of God, won't you believe it's the truth I'm after telling you?"

"How did you get here?" I demanded of Regan.

"I fell over a rock in the dark and broke my arm," he answered. "A farmer took me in and sent word to Sheila, and she came up with a car and fetched me down to Dublin. What are you going to do?"

"That depends on you," I said. "Grundt's the man I'm after. Tell me where I can lay hands on him and I think I can promise that nothing will happen to you."

"And what kind of a dirty tike do you take me for?" the young man cried. "I mayn't have much use for the Germans, but if you think I'd turn informer-"

I was about to speak when I became aware that the girl was making secret signs to me. So I told the fugitive I must think the matter over, and bade him return to his hiding-place under the rafters. I went into the bedroom. Here, presently, Sheila joined me. "What will they do to him if you hand him over?" she questioned tensely.

"Hang him, or shoot him, without a doubt."

"To hell with you and your wars!" she burst out passionately. "He's my man, and I'm going to save him. But you must promise he'll never know."

"I think I can promise that," I said.

"And you'll give me your solemn word that no harm shall come to my Terry?"

"Yes. On the Bible, if you like."

"Then listen!" Her voice sank to a whisper...

BUT Clubfoot was one too many for us. Let Mr. Packy Myers, the

Herculean ex-pugilist who kept a newspaper shop behind the North

Wall, tell the tale of our discomfiture. His story was that, a

few days previously, a stranger-whose description tallied with

Larry Forde's-had called at the shop and, displaying a

fifty-pound note, had explained to the astonished Mr. Myers that

the same would be his in return for a trifling service. All that

was required of him was to lodge for a few days in a house in

Rathmines, a suburb of Dublin, and run errands for a gentleman

staying there. The shopkeeper promptly accepted the offer and in

the upshot found himself at the beck and call of an eccentric,

clubfooted foreigner, running errands and answering the front

door.

Part of the terms of his agreement was that he should not show himself in public save with his hat pulled down over his eyes and the lower part of his face muffled in a scarf, even when opening to visitors-with the result that, at about nine o'clock on the evening of my adventure, on opening the street door in answer to a ring, he was pounced upon by three stalwart individuals and, his cries stifled by a hand pressed to his mouth, he was dragged to a car and driven swiftly and silently to the Castle. There the discovery of the trick that had been played upon us sent us racing back to Rathmines. But, needless to say, the man we were in search of was gone.

The girl, whom my Intelligence colleague and I took along as hostage to the rendezvous, was as bewildered as we. But she had fulfilled her part of the bargain and her Terry was duly left unmolested in her waiting arms. For Clubfoot had actually been in the house when we reached it the first time. Always an excellent psychologist, however, he knew the value of the idée fixe in planting an identity, and had laid his plans accordingly.

The point was that Tacky Myers, in consequence of an injury sustained in the ring, was compelled to wear a heavy surgical boot.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's

death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.