RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Blue Book Magazine, November 1931 with "Miss Parritt Disappears"

WHILE convalescing from shell-shock suffered during the First World War, the English journalist George Valentine Williams, who served as a captain in the Irish Guards, took up writing "shockers" on the advice of the prominent genre writer John Buchan.

With The Man with the Clubfoot (1918), Williams introduced Dr. Adolph Grundt (or "Clubfoot"), who became one of the great "master criminal" villains of thriller fiction of the 1920s and 1930s and launched Williams on a lucrative career as a crime writer.

Between 1918 and 1946 Williams published twenty-five crime genre novels and two short story collections.

Many of these works are master criminal thrillers in the Edgar Wallace/E. Phillips Oppenheim mode (some with Clubfoot, some not), but some are detective novels (or at least "mystery" yarns) as well.

MANY people are under the impression that the alluring vamp of spy fiction is a recognized figure of secret- service work. I hate to disillusion you, but such is really not the case. Women have their uses in espionage, but the general experience has been that their tendency to survey a situation through the glasses of their emotions rather than their reason, and their fatal predisposition to dramatize their relations with the opposite sex make their value as regular agents questionable. I have had dealings in my day with more than one of these hush- hush sisters; and those who were not out-and-out adventuresses, and therefore untrustworthy, usually fiddled around with a little espionage as a sideline.

All of which should go to prove that Frances Parritt was the exception that proves the rule. I have had to give her a fictitious name for reasons that will appear. If you are looking for a rapturously lovely and wonderfully gowned adventuress of the Olga-from-the-Volga order, however, I am compelled to disappoint you. The Parritt, as we called her behind her back, was irredeemably plain—much given, also, to the wearing of tweeds and low-heeled shoes. To state, however, that at a time when the British Secret Service ranked second to none (in the years immediately preceding the war) she was classed with the star turns, is only to do justice to her extreme efficiency, unfailing resourcefulness and rocklike determination.

On her frequent missions abroad, where all the counter- espionage services of the Continent would be keeping their eyes peeled for fellows like Francis Okewood, Philip Brewster or your humble servant, nobody paid any attention to the insignificant little Englishwoman, who, I should explain, concealed behind the placid self-assurance of a deaconess the memory of a Datas and a brilliant fluency in foreign languages. Her reports on the Frisian coast defenses, I recollect, were remarkable; the only really adequate survey of the Heligoland works which the Admiralty had in its files up to the outbreak of the war came in large part from her; and it was she who, on a sketching trip to the Danube in the summer of 1912, gave the first reliable warning of the storm gathering in the Balkans.

For all that we treated her like one of ourselves, she was in no sense a masculine woman. I cannot remember ever to have seen her except in traveling clothes; but that she took a certain feminine care of her looks was evident from the whiteness of her hands and the fine luster of her abundant brown hair. Yet there was no feminine fluffiness about the Parritt. She would breeze into the office from Agram, or Abo, or Swinemünde, or wherever it might be, make her report and clear out. And she never loafed on the job.

Picture, then, the alarm and despondency at Headquarters when one day the Parritt incontinently vanished off the map. It was, if I remember rightly, during the summer of 1913, and the month was June. At that time, for our knowledge of the doings of the German Fleet we chiefly relied upon one Andresen at Kiel, a naturalized German of Danish birth. Andresen's work had been falling off. His reports had grown scanty and were none too trustworthy. So the Chief, always on the alert for signs of double-crossing, packed the Parritt off to Kiel to investigate.

She notified us of her arrival in the ordinary way. Then silence. It was the Parritt's pride that she always contrived to keep in touch with the office: yet more than a week went by without further word from her. And almost simultaneously with her arrival Andresen dried up for good.

I was the most fluent German scholar available in London at

the time. "This is a straight job, Clavering," the Chief told me

as he gave me my orders. "As you re not known at Kiel, you can

safely appear as an ordinary summer tourist. To call upon Miss

Parritt at her boarding-house as a friend from London will

involve you in no risk. You and I know our Parritt. Her cover is

sound—she's supposed to be inquiring about post-graduate

courses at the University—and in no conceivable

circumstances will she ever give the game away. If she really has

disappeared, you'd best go boldly to the police, in which case

you'll not want to be messing round with disguises or faked

identity business."

Andresen kept a beer-garden at the water's edge on the outskirts of Kiel. I had located Miss Parritt's pension—she always stayed at pensions in preference to hotels—on the map, but before looking her up, I decided to run out and give Andresen's place the once-over.

I left my bag at the station and boarded a tram which dropped me at the terminus. It was late on a golden June afternoon. Five minutes' tramp along the dusty coast road brought me in sight of a rustic signboard, and beyond it, of a ramshackle kind of pavilion with a dozen or so roughly carpentered tables set out in a clearing among some pines. A deep silence reigned and between the trees there were glimpses of white sails upon gleaming blue waters. The place seemed deserted, but that did not surprise me. Andresen's was clearly one of those establishments to be met with in the environs of so many German cities where on Sundays workmen bring their families, to drink a glass of beer and play skittles under the trees.

As I entered the garden, a woman appeared from the house. My heart sank when she was near enough for me to distinguish her face. It was ghastly, and her eyes were red and swollen. I asked myself what tragedy could have befallen. When she returned with my Pilsener I sought to draw her into talk, but she answered only in monosyllables, her face obstinately turned toward the house as though she were anxious to be gone. As a last resource, pointing to the decrepit skittle alley which skirted one side of the garden, I ventured: "If your husband's about, perhaps he'd give me a game?"

On that she grew sullen. "My man isn't here," she proffered.

"Maybe he'll be back later?" I hazarded.

She shook her head.

"He's away just now."

"For how long?" I persisted.

"What's it to you?" she demanded roughly, rounding on me; then to my dismay she fell into a fit of weeping.

"Um Gottes Willen," I entreated her, "I hope I've said nothing indiscreet! I only asked after Herr Andresen,"—I made a deliberate pause,—"because I've heard my friend Miss Parritt speak of him."

Thereupon the woman lifted her streaming face to mine.

"So? The gentleman is a friend of the English miss? The Herr is English too, perhaps?"

"Certainly," I told her, and made up my mind to give her a lead. "Won't you tell me what's happened to Andresen?"

The look she bestowed upon me was charged with doubt and suspicion. But I had to discover whether she was in her husband's confidence, so I drew a bow at a venture. "Number 131," I added softly, giving Andresen the designation he bore on our books.

With a panic-stricken air she stared at me, pressing her thin hands to her face. Then glancing over her shoulder she said under her breath: "Did the Herr notice a man as he came in the gate?"

"No," I answered.

She plucked my sleeve and pointed. Through the trees I saw a thick-set figure in black, its back to the garden, standing under the signboard.

"Come quickly," the woman whispered. And picking up my glass, she led the way into the house.

After I had followed her in, she closed the door and stood before it.

"Six days ago some men came and took my husband away," she said. "They were secret police. Since then one has stayed on guard outside day and night. You were lucky he didn't see you come in."

She bent her head listening. But all was quiet outside.

"And my friend Miss Parritt? Did she come here to see your husband?"

"Three days in succession. On the fourth day they took him. As they led him away he whispered to me to tell her to leave Kiel instantly. But she didn't come back, and I didn't know her address."

Well, it was clear that there was nothing further to be done

at Andresen's. Frau Andresen let me out by the back door and

showed me a path through the woods which, she said, would bring

me out on the tram-line a kilometer away, out of sight of the

watcher on the road. Without incident I picked up a tram and,

returning to the city, went straight to Miss Parritt's

pension, which was in the center of the town.

At the pension I affected to be looking for accommodation and made the landlady show me several rooms before I casually inquired whether she had any other English guests. There had been one, she said—eine sehr nette Dame, a Miss Parritt. But she had left some days before, to stay with friends. Three minutes later I was back in the street with the Parritt's address in my notebook. She was stopping with Herr and Frau Helmstedter at the Villa Waldesruhe, which lay in the woods a mile or so on the land-side of Kiel.

The Parritt, as I have already observed, was never one to loaf on the job. If she had gone off to these Helmstedters, it was undoubtedly because they were, in some way or other, involved in her investigation. In the taxi which drove me out to Laubheim, the nearest village to the villa, I cudgeled my brains in vain for an explanation of the mystery of her disappearance.

With Andresen already behind the bars, I knew it behooved me to be cautious. It was no use my walking blindly into a hornet's nest. Accordingly, having noticed in the village a garage with cars for hire, I paid off my taxi and dined at my leisure at the inn. It was nearly eight o'clock by the time I reached Laubheim, and I intended to wait until darkness fell—at that season and in that latitude not until around ten o'clock, as I knew—before reconnoitering. The landlord told me how to reach the villa—it was five minutes' walk through the woods which came down to the edge of the village; but he knew nothing of the Helmstedters. They were probably summer visitors—the Villa Waldesruhe was always rented for the season.

Well, it was not the first time I had played the burglar. The villa, hedged about with trees, with merely an oak paling separating it from the forest, was wrapped in darkness and silence. It was only on going round to the rear that I caught a glimmer of light in a window of the upper of its two floors. I resolved to investigate that light.

A slight manipulation of a kitchen window, and I was inside. Profound silence, save for the thumping of my heart in my ears as, pistol in hand, I crept stealthily up the stairs. On the uncarpeted landing I paused, confronted by four closed doors. Enough daylight yet fell through the window on the landing to enable me to see my way; but I could distinguish no trace of the light I had perceived from outside.

Grabbing the handle of the door in front of me, I turned it swiftly and silently, thrusting the door wide. On the instant I recoiled and my hand, grasping my automatic, jerked instinctively upward.

An enormous man, clad in a dressing-gown over vest and trousers, stood silhouetted in the light of a table-lamp.

One glance at him and a thrill went tingling down my spine. Those ferocious eyes, peering out from under jutting, shaggy brows, that savage mouth, baring the teeth in a snarl as malignant as a tiger's, those long and powerful arms—no need to look downward for the monstrous boot protruding from under the folds of the ample robe. To cast eyes but once upon the Man with the Clubfoot was to forget him never. And the Parritt, poor little Parritt, was in his power—prisoner, as now I made no doubt, of this ruthless cripple whose name was a byword in the Secret Service of every European Power.

The realization of my hapless comrade's plight came to me in a flash. My voice was husky as I cried, "Put your hands up, Grundt!" At the sound of his name, the expression of the apelike face seemed to change. He had been glowering at me in stupefied ire. But now the anger melted from his regard and his fleshy lips were twisted up in an impudent, cynical grin. Nevertheless he did my bidding, albeit reluctantly.

"So, so?" he muttered as he raised his great arms. "My young English friend, as I live! You've come for Miss Parritt, I'll wager?"

"She's here, then?" I cried eagerly.

"Certainly." He wagged his big head toward the left. "That's her room—the third door along. But she's out just now."

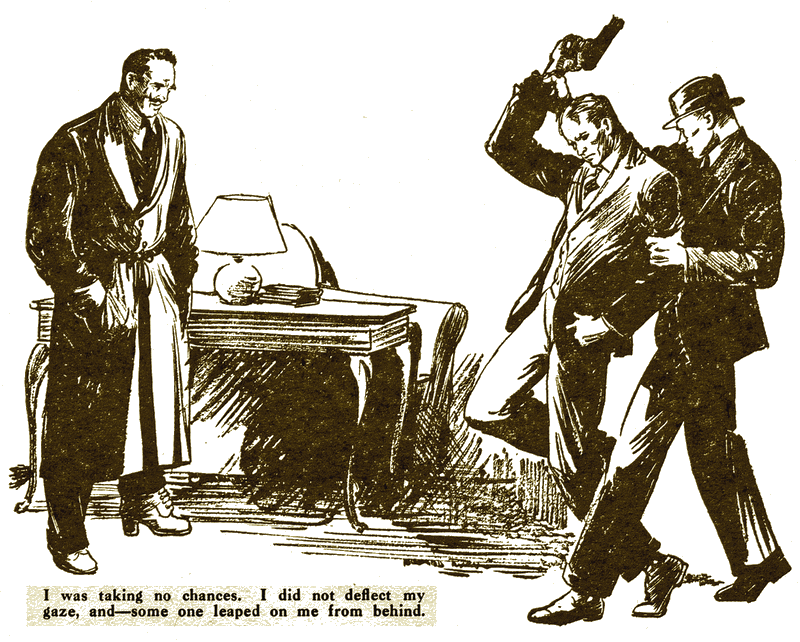

I was taking no chances with him. I did not deflect my gaze even when I heard a light footstep behind my back. Making sure that he had lied and that it was the Parritt running to meet me, I called sharply across my shoulder, "Stay where you are!" At the same instant some one leaped on me from behind, pinioning my arms in a grip so savage that I thought my elbows would crack. The pistol was plucked from my grasp and I was violently tossed against the wall. "You'll do there," spoke a voice. "And we'll have the hands up, if you please!"

Automatically I obeyed. A muscular youth at the head of the stairs was covering me with a revolver. Grundt had stooped to retrieve my pistol which had fallen to the floor. As he drew himself erect, I saw that he was shaking with laughter.

"Put your gun away, lieber Helmstedter," he chortled in his resonant bass. "You make me ashamed of our good German hospitality. Is this a way to welcome our English visitor? For he is welcome, nicht wahr?"

And he broke, trumpeting, into a veritable tempest of stentorian, ogrelike guffaws.

Now his companion, a regular young Hercules in build, lowering his weapon, seemed to catch the infection and began to laugh in his turn. I stood there like a fool, staring bemused at the spectacle of those two lunatics doubled up with laughter, clapping one another on the back in the ecstasy of their mirth.

At last Clubfoot turned to me. "Hochverehrter Herr," he gasped, the tears running down his face. "You've come to rescue Miss Parritt, nicht wahr? You're welcome to her—if you can persuade her to go!"

"I don't know what the devil the joke is," I retorted crossly. "If Miss Parritt is detained here against her will, she'll want no persuading, believe me!" This remark set them off again in a regular tornado of merriment.

"You just try her, that's all," Helmstedter cackled.

Then big Grundt heaved himself forward and laid an immense paw on my shoulder.

"I see I must explain," he said, wiping his eyes. "I don't know whether you're aware of it, but your engaging colleague is somewhat injudicious in her choice of acquaintances."

"Meaning Andresen?"

The great mouth shut like a trap.

"Andresen, exactly. Of course, you would know about him. He was stubborn at first—oh, he's made a clean breast of everything now!—and it became urgent to find somebody who could throw some light on the gentleman's activities. My Master was keenly interested and you know that patience is not one of his virtues. At this moment the fact of Miss Parritt's 'visits to the beer-garden was reported ' to me. I immediately conjectured a connection between your revered Chief and her. Helmstedter here, one of the most promising of my lieutenants, had this villa for the summer. I instructed him, with the aid of his charming wife, to scrape acquaintance with your colleague and invite her to stay with them. The lady having accepted, nothing was simpler than for me to present myself later, in the guise of an old friend of this delightful couple."

I laughed. "Surely you don't kid yourself that Miss Parritt has never heard of you, Grundt?"

His eyes narrowed. "If she has, she concealed it. In any case, I didn't figure under my own name but as Professor Hans Traugott. I did everything in my power to make myself agreeable to her, to win her confidence—"

"Without the slightest result, I'll venture to say!"

Clubfoot grunted. "She was as tight as an oyster about Andresen, if that's what you mean. But for the rest, I succeeded only too well. Verdammt, man," he exploded, "the woman's in love with me now! She refuses to leave me!"

I gazed at him thoughtfully. This, of course, was one of the Parritt's tricks; but just what was her game? With an earnest mien Grundt possessed himself of my two hands.

"You've got to take her home, man! Do you understand me?" he cried irascibly. "She writes me verses: she tries to mother me. It's ridiculous at my age—and hers! I won't have it! Besides, she scares me—I've never met such determination in my life. You've got to rid me of this woman. You'll do this much for a colleague, lieber Herr?"

The sound of women's voices in the hall abruptly ended this sheerly preposterous interview. With a hollow cry of, "There she is now!" the redoubtable Man with the Clubfoot retired swiftly into his bedroom, slamming the door and locking it. Already Helmstedter was halfway down the stairs. I saw him grab one of the women who were there and whisk her off through a door. A figure, whose angular silhouette was all too familiar to me, remained behind.

Directly I set my eyes on her I knew that Grundt had spoken the truth, incredible though it was. She was transfigured: she was almost good-looking. She did not give me the chance to speak.

"I know what you've come for, Clavering," she said. "But it's useless. You can tell the Chief I've kept faith with him. But I'm through. I've met the only man who has ever taken the trouble to understand me, and with him I intend to stay." She pressed her lips together firmly.

I goggled at her.

"Have you taken leave of your senses?" I stormed. "You come here on a job, and the first thing you do is to get tied up with an enemy agent like Helmstedter. And not content with that, you proceed to fall in love with the head of the Kaiser's secret police. Or perhaps you'll tell me you've never heard of the Man with the Clubfoot?"

She sighed seraphically. "He didn't deceive me, though I let him think he did. I never suspected the Helmstedters, I admit: I thought they'd be a good cover. But my secret-service days are over, Clavering. A woman has the right to work out her salvation in her own way." Her face glowed. "And I've found mine. A wonderful man. I can bring a new happiness into his lonely life—"

"Like hell you can!" I told her. But there, what's the use? When I thought of the risk I had taken in breaking into that blinking villa to rescue her, I just saw red. I did not spare her—I gave her the brutal truth straight from the shoulder. Even so I had to argue with her for the best part of an hour before she would consent to accompany me back to England. And she sulked the whole way home.

The day after her arrival she sent in her resignation. The

Chief did not know whether to laugh or cry. I never came across

her again, but I heard she did useful work for the British

Mission in the United States during the war.