RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

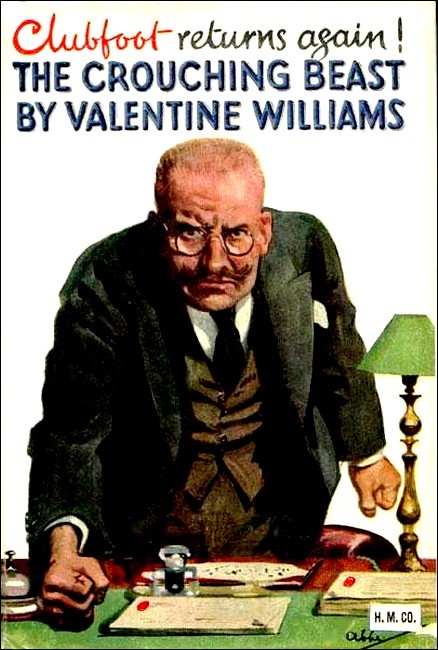

"The Crouching Beast," Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1928

Mr. Dooley remarks in the course of one of his conversations with his friend Hinnissy that news is sin and sin news and that you can write all the news in a convent on the back of a postage stamp. The sage was merely expressing in his own way the discouraging but inescapable truth that evil makes livelier reading than good for the simple reason that the blameless life is static while ill-doing implies action. If as the Good Book tells us, the way of the transgressor is hard, for the purposes of fiction especially sensational fiction, it is incomparably better value than the way of the just. The descent to Avernus, from the reader's point of view, is considerably easier going than the primrose path.

Where authors congregate in the Elysian Fields it is no doubt a source of gratification to the late Dean Farrar to know that generations of schoolboys continue to devour Eric or Little by Little. I am afraid however, that the continued popularity of the good Dean's masterpiece reposes more upon the tribulations of the well-intentioned but unfortunate hero, and in particular, the fiendish machinations of Barker the bully, than the elevating sentiments of worthy Mr. Rose. The fact is that in fiction stained-glass heroes have a habit of staying put in their windows: it is the bad boys, the men of flesh and blood, that come to life—d'Artagnan and Tom Jones, Gil Blas, Figaro and Hajji Baba.

Particularly the villains—those, at least, of the more plausible variety—linger in the memory. We may not recall the intricate plot of The Woman in White but who can forget Count Fosco, with his light tenor voice and his canaries? Still the mere names of Fagin, Long John Silver, Dr. Nikola and Count Dracula send long shivers chasing down our spines, however the exploits in which they figure be blurred in the mind.

I wrote a book about a villain once—his name was The Man with the Clubfoot—and it changed my whole career. I think it was fated. Desperate characters were ever my meat. At a tender age, my mother used to tell me, she discovered her sweet little boy directing his sisters in a childish game of his imagining representing the police (with handkerchiefs realistically tied over their noses) exhuming the surplus wives whom the bigamous Mr. Deeming had interred under the kitchen floor.

When my father took me as a schoolboy to the Adelphi melodramas my delight was not the breezy and super-heroic Mr. Terriss but the villainous Mr. Abingdon, with his black moustache, nonchalant air and "faultless" evening dress. I remember thinking, when we studied "Hamlet" at school, that Shakespeare would have heightened the dramatic effect of the play by giving us more of the King, so gorgeously profligate, so resourcefully murder-minded. I always felt that Conan Doyle's Moriarty is no more than a rat in the arras—Sherlock Holmes could only have gained in stature had the author bestowed on the shadowy figure of the impresario of crime some of the tender care he lavished upon the delineation of the harmless but necessary Watson.

When, in the midst of the World War, the spirit moved me to try my hand at writing a "thriller," one of the first conclusions I arrived at was that the surest and subtlest way to build up the hero's character was by creating a reasonably plausible villain. My hero was to be a quiet Englishman of the regular officer type—it seemed obvious to me that, the more ruthless his opponent could be made to appear, the more effective the hero's nonchalance and resolute abstention from heroics. The merit of the secret service setting with the Great War as a background was that in this field, as I knew from a fairly intimate acquaintance with the subject, there was absolutely no limit to the perilous situations to be contrived. Unconsciously, perhaps, The Man With the Clubfoot expressed the sense of bewilderment with which we all discovered that in war anything can happen—and frequently does.

A novel resembles a dream in being a thing of shreds and patches, a welter of impressions consciously or subconsciously absorbed. Actually my tale became for me an outlet of escape from the pent-up emotions of the battlefield, for I wrote it when convalescing from wounds received on the Somme. One might say that the shell which blew me sky-high and temporarily put an end to my military activities blew me into fiction, for, before joining up with the Irish Guards, I had spent all my working life in Fleet Street. I was propelled aloft, that sunny September afternoon, an experienced newspaper man and came down a budding novelist.

The Man With the Clubfoot embodies, as I discern in retrospect, some of the "battle dreams," that familiar symptom of shell concussion, which haunted my convalescence. The Somme was probably the greatest battle the world has ever seen: the carnage had no parallel in the annals of war: we ate and slept and fought among piles of corpses. The Guards Division attacked twice in ten days and I took part in both attacks. In the first I was knocked flat three times by shell-bursts but escaped injury: I had one orderly wounded and another killed at my side: I received a bullet through the heel of my boot and a second through the strap of my field glasses, but emerged unscathed as one of the two or three surviving officers of my battalion, to go over the top again in ten days' time.

Battle dreams are horrible. I had visions of Hindenburg, as gigantic as his wooden image reared in Berlin for patriots to knock nails into on behalf of war charities, striding at me over mountains of dead: I would fancy myself alone in a trench with walls a hundred feet high and raked with monster shells. But my most frequent nightmare, continually recurring, was to find myself in war-time Germany without papers of any kind and the whole of the secret police on my track.

When the time came for me to leave hospital and undergo three months' convalescence, I faced the world in a miserable and terrified frame of mind. It was then that a gracious Royal lady came to my aid. Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, who was a patroness of the Empire Hospital, Vincent Square, where I was a patient, offered me the use of Rhu Lodge, on her Rosneath estate in Dumbartonshire. In this charming retreat, lapped by the waters of the Gare Loch, I found peace. Violent exercise or any form of excitement was forbidden me. But after a crowded life as newspaper man and war correspondent I could not remain inactive. So, to occupy my mind, I resolved to write a "thriller."

Before the war I spent five years in Berlin as a newspaper correspondent. They were years when Anglo-German rivalry reached its most acute phase and a certain type of German was at little pains to conceal his true sentiments for Britain and the British. Once, in the press canteen of the Reichstag, an obscure German journalist, representative of a pan-German and, consequently, violently anti-British newspaper, tried to pick a quarrel with me. The incident was without importance, but I never forgot the berserk rage into which this cantankerous fellow worked himself. His blazing eyes, his screaming voice, his large paunch shaking with ire, came back to me when the character of Grundt, the master spy, was taking shape in my mind.

The clubfoot was an added touch. It seemed to me sound psychology to ally physical deformity with a warped mind, as Hugo did with Quasimodo and Dickens with Quilp: moreover, ever since I can remember, the particular form of disability associated with a monstrous boot has instinctively repelled me. For the rest, Dr. Grundt's personality is drawn from no one person but is an amalgam of the many different types of Prussian functionary with which I came in contact during my years in Germany under the Empire.

Although the reader may not appreciate it, actually a good deal of first-hand observation of German Court life has gone into the delineation of Dr. Adolf Grundt. That rather pathetic figure, William II, was absolute monarch and Supreme War Lord but largely for window-dressing purposes—in fact he was the tool of the Camarilla, the inner circle at Court. Wherever you have an autocracy, you find irresponsible advisers who, by a judicious admixture of flattery and wire-pulling, exert even greater influence over the march of events than the despot. At the height of the ex-Kaiser's reign, for instance, the most influential personage of the State, more powerful, even, than the Imperial Chancellor, was the head of the Emperor's Civil Cabinet, because he had the immediate ear of the sovereign. If William II did not have a personal secret service apart from the political police, he might well have had one. As things were in the entourage of the monarch, if Grundt did not exist, he should have been invented, as Voltaire said of God.

For myself, I set out to create a villain but must admit to having acquired a sneaking regard for the Herr Doktor in the process. He is ruthless, but he has plenty of courage: he can be diplomatic on occasion, but is full of character; and he has (or I like to consider that he has) a sense of humour. I am glad to know that many of my readers do not consider him a hundred per cent. rascal, but speak of him indulgently, nay, even affectionately, as "old Clubfoot."

Let me hope that, renewing acquaintance with him in this Omnibus Edition, they will find that their feelings for him have stood the test of time.

Valentine Williams, Estoril, Portugal, March, 1936.

Peace at last....

I can scarcely believe we have beaten them. Yet to-night bonfires were flaming the wonderful news across the Downs and Bill Bradley says London has gone wild.

Dear Bill! He knew I would be sorrowing while all England rejoiced, and he turned his back on the junketings in town to motor down to Sussex and comfort me. He has been so patient, so understanding, through all these agonising months of uncertainty that to-night, before he left, I promised to give him his answer at Christmas, if by then there is still no news.

How should there be any news? The British mission which has gone into Germany has been ordered to make the closest inquiries; but what more can they do than the Red Cross, the Crown Princess of Sweden (bless her golden English heart!), the King of Spain, the Vatican, all the high neutral sources which have already tried and failed?

It is so bitter hard to abandon hope. And yet I haven't much faith left. It is eight months since I last heard: and they are quite definite when I see them in Whitehall. Well may they call it the Secret Service! Shall I ever forget the furtive little office, high above the stir of the Embankment, the tidy desk, with just a telephone and some letter trays, and behind it my Nigel's Chief, that frightening old man, whose eyes were yet so gentle as he told me I must make up my mind for the worst?

To ease my mind of its grief, to clear it for this decision I feel I owe to poor Bill, I have resolved to write my story. Perhaps I shall find solace in the very anguish of living in memory once more through the phases of that extraordinary adventure which Nigel Druce and I confronted together.

The last bonfire has flickered out. Not a dog barks: the countryside is deathly still, blanketed in the November sea-mist that clings pearling to the diamond panes of my cottage window. But shadowy figures come thronging about my lamp: dear Lucy Varley, my little Major, the Pellegrini with her flaming hair, Rudi von Linz, dapper and debonair, Pater Vedastus, as I first saw him, leaning on his spade in the garden of the Capuchins, and that man of terror they called The Crouching Beast, Clubfoot, the grim and sinister cripple who stood in the forefront of those who brought down untold misery upon the world and on me.

And my Nigel. God help me! Of him it will be hardest to write....

Olivia Dunbar.

11th November, 1918.

Was the hush that rested over the garden of the old Kommandanten-Haus, that breathless July evening of 1914 which launched me on my strange adventure, symbolical of the lull before the storm which was about to break over Europe? Now that I look back upon that summer I spent at Schlatz I think it was. Personally, I was far too busy absorbing first impressions of life in a pleasant German garrison town to have ears to hear the ominous beat of the war drums, faint at first but growing steadily louder, like the tomtoms of "Emperor Jones." But later, when I was a V.A.D. at Dover and at night the wind from the Channel would awaken us with the throbbing of the guns in France, thinking of those glorious summer days, I would picture myself sleeping peacefully, like almost everybody else, through the growling thunder of the approaching catastrophe.

On this evening, as I remember, dusk had fallen early. The sun had died in a riot of wrathful colour, and beyond the end of the garden the lemon-tinted sky set off in sharp silhouette the high wall of Schlatz Castle and the square tower, still higher, that rose to heaven above it like a stern prayer in stone.

Not a leaf stirred in the rambling and neglected garden which, between two blank grey walls, spread its train of green right up to the piled-up mass of the Castle. The air was warm, and through the open French windows of Dr. von Hentsch's study the heavy fragrance of the roses mounted to me as I sat at the typewriter. I had the feeling that the garden was holding its breath, waiting, as it were, for something to happen, while the darkness slowly deepened and high up in the air yellow lights began to glimmer in the Castle windows.

I had just switched on the reading-lamp when I heard the postman coming up the gravel path at the side of the house. Nothing much ever happened at Schlatz; and we had so few visitors that it was not hard to identify our different callers by their step. Particularly Franz, our postman. Though Lucy von Hentsch and her husband were kindness itself, I was at times homesick for England. Letters made a great difference to me at Schlatz, even poor Bill's, and I used to catch myself listening for Franz's stolid, military tramp.

At his sonorous sing-song greeting, "Schon'gut'n Abend, Fräulein!" I looked up from Lucy's manuscript to see him standing in the open window, his loose blue uniform all flecked with the July dust.

"There was nobody at the front, Fräulein," he said, "so I thought I'd look round at the back, on the chance."

"I didn't hear the bell," I explained. "The Herr Landgerichtsrat and Frau von Hentsch are dining out and the maids have gone to the Fair."

"And the Miss"—"die Miss" was the way I was often addressed—"remains like that all alone in the house?" Franz was sorting through his bag.

I laughed. "The Miss has plenty to occupy her, Franz," I told him, and pointed to the pile of manuscript beside my machine.

He wagged his head doubtfully.

"The newspapers are full of nothing but robberies and murders," he observed with an air of gloom. "The Kommandanten-Haus is lonely, perched up here on the hill above the town. Frau von Speicher, the late Kommandant's lady, she would never stay in the house by herself—nee, nee! The Fräulein should, at least, keep the windows closed."

"Nothing's going to happen to me right under the noses of the Castle guards," I answered, and took the letters he handed over—there was one for me, I saw with delight, from my married sister, Dulcie. "You must remember that English girls are used to taking care of themselves, Franz...."

"Na und ob!" the postman put in, as who should say, "Now you're talking!" "It's the men in England who need protecting, Fräulein, if the newspapers tell the truth about the goings-on of your friends, die Suffragetten...."

We both laughed. This was a stock joke between Franz and me. Like all Germans I met, he displayed a sort of incredulous interest in the fight for female suffrage in England which loomed so large in the newspapers that summer.

"Anyway, the Miss has nothing to fear from the prisoners," the postman resumed, moving his head in the direction of the glowing windows of the Castle. "The Herren Offiziere amuse themselves far too well under arrest to think of escaping...."

I smiled my assent, for the same thought was in my mind. I should explain that Schlatz Castle, once the seat of the Dukedom of Schlatz—Herzog von Schlatz is one of the titles of the Kings of Prussia—was used to lodge officers sentenced to fortress imprisonment for offences against the military code such as duelling, gambling and the like. These officers were frequently let out on parole, to get their hair cut and so forth, and I used to see them about the town in undress uniform without their swords. As far as I could gather, their punishment consisted solely in the loss of promotion and the temporary deprivation of their personal liberty. Even Dr. von Hentsch used to say that the drinking and gambling up at the Schloss were a disgrace.

The garden of the Kommandanten-Haus ran right up to the Castle wall, and sometimes in the evening sounds of revelry would be wafted down to us from the detention quarters. Our house, as its name indicated, was really the official residence of the Castle Commandant. But when Major von Ungemach, who was a bachelor, was given the post, he preferred to occupy a suite in the Schloss and let the picturesque 18th-century house to Dr. von Hentsch, who was transferred about the same time to Schlatz as judge at the local courts.

"The Herren Offiziere won't trouble the gracious Fräulein," Franz added. "I meant tramps and such rabble. With the harvest a lot of bad characters drift into the town." He wagged his head. "One can't blame them. Hunger makes men desperate. As long as you have wage-slaves, you'll have crime, Fräulein. Even in old England, which isn't a police State like this...."

I stared at him in amazement. "Why, Franz," I exclaimed, "you're talking like a Socialist. You'd better not let the Herr Landgerichtsrat hear you...!"

His sun-browned face, bony and, in repose, rather severe, broke into a slow smile at the horror in my voice. I really was taken aback. Socialists at home I knew of mainly as shabby men in cloth caps who walked in procession to the Park on Sundays under huge banners. But in Dr. von Hentsch's well-ordered household, where only thoroughly constitutional newspapers like the Kreuz-Zeitung were read, Socialists, or Social Democrats, as he called them, were mentioned only to be denounced as incendiary scoundrels dangerously favoured by parliamentary institutions. It sounded to me odd to hear this civil-spoken, rather staid Prussian postman in his trim uniform voicing Socialist doctrines.

"One can say things to an English Miss one wouldn't say to a Prussian official," he observed drily.

I hastened to change the subject, which I felt to be dangerous.

"I'm sure you'd like a glass of beer after your walk," I put in.

"Since the Fräulein is so kind. It's sultry out. I think there's a storm coming up...."

As I ran through the adjoining dining-room, hung with Dr. von Hentsch's collection of antlers, to fetch a bottle of beer from the cooler in the pantry, I heard a tremor of distant thunder go rolling across the garden. With a muttered "Pros't, Fräulein!" Franz drained the glass at a draught. As he set it down and wiped his moustache, the lamp on the desk blinked.

"Oh, dear," I exclaimed, "I do hope the light's not going to fail again to-night. I want to finish all this typing before I go to bed....!"

"The power station's overloaded," remarked the postman, adjusting the sling of his bag over his shoulder. "After the entertainment of His Majesty when he visited Schlatz last winter there were no funds available for carrying out the necessary improvements. The town will have to wait for a decent electric light supply until a few more Social Democrats are elected to the council. That time isn't far off now, Fräulein. The struggle is coming to a head...."

"I'm afraid I don't know very much about your German politics, Franz," I interposed evasively.

"This is something bigger than mere politics, Fräulein," he answered in his earnest way. "The struggle is not simply a clash between parties. It's a fight between the army and the people. It can end in only one way. There'll be either a revolution or a war."

Once more the thunder growled in the darkness without.

At that I laughed outright. "Revolution? War? Now you're talking nonsense, Franz. If you said there was going to be a revolution in England, you'd still be wrong; but you'd be less far from the truth. Of course, if civil war does break out in Ulster, there's no knowing what might happen. But in Germany! People who say things like that don't know when they're well off. You've got a Kaiser to be proud of, a prosperous country, good wages, beautiful cities with splendid theatres and music and open-air beer gardens where you can take your wife and children, all kinds of inexpensive pleasures that working-men in England don't enjoy, I can tell you. As for war, you mustn't believe all this scare rubbish you read in the newspapers. In spite of the Daily Mail relations between Germany and England were never better than they are to-day."

With a brooding air the postman settled his red-striped cap on his head and hitched up his bag.

"All that may be true," he said. "But if the military want a war, it won't be hard to find a pretext. For the rest, you Engländer have a parliament that is a parliament, that can make and unmake Ministries; not a wretched talking-shop with no real power like our German Reichstag. This is a military State, Fräulein. The civilian doesn't count. He's only fit to be sabred, like the cobbler of Zabern, to teach him his place. There is no liberty for the individual in Prussia. If you were to report to the Post-Direktor what I have said to you this evening I should be flung into the street, into gaol, maybe, my pension would be taken away and my wife and children would starve. But the masses are getting restless under the rule of the sabre. As soon as the military believe that the people are getting out of hand, they'll start a war. And that may be sooner than you think...."

I laughed incredulously. "A war? A war with whom?"

For a moment Franz was silent, and in the pause I heard a sudden wind brush shudderingly through the trees outside the window. Behind the jetty mass of the Castle the lightning flickered white across the sky; and louder now, but still reluctant and stertorous, the thunder muttered again.

Then the postman, having glanced cautiously over his shoulder, drew nearer and, dropping his voice, said:

"Strange things are happening up at the barracks. At the mobilisation store they are working day and night. There is talk of a new uniform to be handed out, a grey uniform which has never been seen before. Do you know what that means, Fräulein?"

His serious brown eyes, intelligent and trusting as any dog's, were fixed on my face. His manner was so portentous that I fell back a step. He did not wait for my answer.

"This new uniform is clearly for service in the field," he declared. "In other words, the German Army is preparing to mobilise. And that means..."—he paused, to wrench his mouth into a wry and bitter grimace, then added with measured deliberation—"... that means war!"

I was not greatly impressed. Why, only that afternoon I had been to a Kaffee-Klatsch at Frau Oberleutnant Meyer's! All the young officers of the infantry battalion stationed at Schlatz had been there, including Rudi von Linz, a charming lieutenant who was a particular friend of mine, and we had danced until seven o'clock. And had not Major von Ungemach, the Castle Commandant, telephoned that very evening to ask whether he might call upon me? I had no intention of being alone in the house with the somewhat ardent Major and I had told him I was busy and couldn't see him.

But when an army mobilises surely the officers haven't time to go dancing or calling on their women friends? So I said, rather sarcastically, to Franz: "With whom, pray?"

He shook his head sagely. "That remains to be seen, Fräulein. I'm no politician. Perhaps over this trouble in the Balkans. The newspapers say that the Austrians intend to demand satisfaction from Servia for the murder of the Archduke...!"

"And quite right, too!" I cried. "Dr. von Hentsch says the whole thing was planned by the Servian Government. To think of that poor man, and his wife too, being shot down like that in cold blood!"

"Na," said the postman, heaving up his satchel, "what will be, will be! I wish you good-night, Fräulein!" He glanced into the garden stretched out black and listless in the close air. "I must hurry if I'm to finish my round before the storm breaks."

"Gute Nacht, Franz," I replied, and turned back to the desk to read my letter.

At the window he hesitated. "The Fräulein will have the goodness not to repeat what I said to-night? It would get me into serious trouble if it were known...."

"Schwamm darüber!" I told him, or "Wash it out!" as you might say. "I've already forgotten it. And I advise you to do the same."

He smiled whimsically and wagged his head in a gesture expressive of doubt. Then, "Gute Nacht, Miss," he said. "Angenehme Rune!"

"Ebenfalls!" I answered, giving him back the stock reply to his wish that I might sleep well—German, like Chinese, bristles with ceremonial greetings and no less formal rejoinders—his feet rasped on the path and he was gone. A vivid lightning flash revealed to me a momentary glimpse of the garden with every leaf, as it seemed to me, hanging motionless in the sultry atmosphere. As I picked up Dulcie's letter, once more the thunder rumbled sullenly out of the night....

The postman's gloomy forebodings had left me vaguely restless. Not his talk of war. The activity at the barracks I set down to preparation for manoeuvres or the like; for, from the way the young officers grumbled, to me, at any rate, the battalion at Schlatz appeared to be constantly making ready for something, whether it were inspection by an incredibly terrifying military personage, a field day, or night operations. I was thinking of what Franz had said about tramps. The Kommandanten-Haus was certainly isolated from the town, and I had read in the German newspapers of ghastly crimes committed in lonely mansions.

But the night was airless, and with the windows closed I felt I should stifle in the stuffy study with its thick red curtains, heavy mahogany furniture, and great green-tiled stove gleaming dully in the corner. I contented myself, therefore, with opening the drawer of the desk in the centre of the room on which my typewriter stood and assuring myself that the big revolver which Dr. von Hentsch kept there was in its accustomed place. Leaving the drawer half open, I settled down in my chair beside the lamp to read my sister's letter.

I came across that letter the other day, poor bit of flotsam to survive the deluge which was to sweep so much away. It is mostly about a plan we had made, Dulcie, Jim her husband, and I, to pass the summer holidays together in the Black Forest. I had been invited to spend the last week of July with some American friends in Berlin where Dulcie and Jim, her husband, were to meet me on the 1st of August. As the von Hentsches were leaving for their summer holiday at Karlsbad on 24th July, the arrangement just suited.

August, 1914!

As I re-read my sister's letter the other day, I felt glad that fate had mercifully veiled the future from our eyes. Neither she who dashed off that cheery scrawl on the pretty, azure-tinted note-paper, nor I who read it in the quiet of Dr. von Hentsch's study on that thundery July evening, with the summer lightning streaking the sky behind Castle Schlatz, could know that almost every date she mentioned was inscrutably marked down to be a milestone of history.

This 31st of July, for instance, when she and Jim, who now sleeps under Kemmel Hill, were to start off from London, was to see a brief cipher flash like a train of fire across two vast Empires and call millions of men to arms: this 1st of August, appointed date for our happy reunion in Berlin, was destined to live through the ages as the day on which, by mobilising against Russia, Germany took the irrevocable step: this 2nd of August, when we were to leave Berlin, was doomed to witness the first blood spilled on French soil by the invader. "Jim has booked our rooms in the Forester's house at Kalkstein for the 4th," Dulcie wrote: the fateful 4th of August, which was to bring the British Empire to its feet to face the challenge....

Dulcie wrote to me every week, adorable letters, a bit of herself. I have always been pals with Dulcie, for we had no brothers and Mother died when we were kids. And during the greater part of our childhood, Daddy was soldiering in India while we were being brought up at home.

Dulcie is domesticated, not, like me, "an adventurous romantic," as Daddy used to call me. Before I went to Schlatz I lived with her and Jim at Purley. When Marie von Hentsch, who was at school with me—by the time I got to Schlatz she was married and living in America—proposed me to her mother as private secretary—perhaps I ought to explain that Frau von Hentsch was Lucy Varley, the popular American novelist—I was vegetating in a highly respectable, and abominably dreary, typing job in the city. Dulcie was all against my going out to Germany. But then she was all against my doing anything except marry Bill Bradley. She wanted me to marry Bill and "settle down."

That is precisely what marriage with a thoroughly good-hearted, dull, dear fellow like Bill would have done for me. I should have "settled down" like porridge in a plate. But at twenty-two I didn't want to settle down. On the contrary, I was mad to be up and doing. I wanted to see more of life and the world than I could observe from the windows of the 9.12 from Purley to London Bridge or from my desk in St. Mary Axe. So, having refused poor Bill for the umpteenth time, I went to Schlatz.

Darling old Dulcie! She always wrote reams, everything, just as it drifted into her pen, about Jim and her babies, and the new car ... and Bill. Her letter carried me right out of the tranquil old house with its faint, clean odour of much scouring blended with the summer scents of the garden. As I read on, sheet after sheet in her big, sprawling hand, I forgot all about Franz and his dark forebodings and the lightning flaming behind the Castle and the thunder growling ever louder overhead.

"Bill came in on Sunday after golf," Dulcie wrote. "His first question is always: 'How's Olivia?' You really ought to write to the poor fellow. He looked perfectly miserable although he's won the monthly medal with a round of 78. He says you never answer his letters. He's convinced you've fallen in love with some incredibly dashing Prussian officer. Have you? Jim says if you marry a German he'll call him out and shoot him. Tell me about your conquests when you write. Don't the German men rave about your blue eyes and black hair? They must be sick of blondes. I saw Mabel Fordwych at Murray's the other night. She's got a studio in Chelsea and has cut her hair short. She looked MOST eccentric and mannish. Everybody was staring at her. Great excitement here about the suffragettes. Did you see they tried to blow up the Abbey? Jim took me up to town for our wedding anniversary on Thursday. We dined at the Troc. and went on afterwards to see the new play at the Criterion. At least, it's not a new play but an old one revived. Do you know it? It's called 'A Scrap of Paper.' Stupid title but quite a thrilling story. Some of the crinolines were rather sweet. I suppose you can't get any decent frocks out there. They say we're all going to show our ankles next winter. The creature next door won't like that, will she? You and I will be all right, anyway...."

The sudden loud swish of water plucked me away from Dulcie's gossip. Outside the rain was coming down in a solid sheet. The garden rang with plashings and gurglings, and the clean savour of wet leaves and damp earth was wafted into the room.

Frau von Hentsch had lived long enough in Germany to be as fussy as any German Hausfrau about her belongings. I sprang to the window to close it; for the rain was spurting on the carpet. As I rose from the desk my eye fell on the clock. The hands marked a quarter to ten.

As I reached the window I thought I heard a soft footfall scrape the gravel outside. It was too early for the Hentsches or the maids to be back; and anyway the former would come in by the front door where the car put them down, while the servants would use the kitchen entrance.

Rather startled, I paused and called out: "Wer ist's?" But the footsteps had abruptly ceased and only the hissing crash of the downpour answered me. The garden was inky black and I could see nothing beyond the silvery shafts of the rain, a couple of yards from the window, where the light from the room shone out into the night.

Suddenly the lightning flamed in a flash so broad and dazzling as to light up and hold, for the fraction of a second, in brilliant illumination the whole scene before me, from the little bushes, writhing and bending under the lashing rain outside the window, to the gilded fane on the summit of the Castle tower. On the edge of the turf, not a dozen yards from the window, I saw a man cowering in the shelter of a bush.

I was terribly frightened but I did not lose my presence of mind. As all went black once more, I seized the two doors of the window to shut them. But at that moment came a clap of thunder, so unheralded, so ear-splitting, that I staggered back into the room.

And then, without warning, the lamp at the desk went out and the study was plunged in darkness. Once more I heard that stealthy footfall on the path. There was a hollow sound as the wings of the window fell back again. Against the patch of semi-obscurity they framed, I saw a dark form slip into the room.

Before I could move or cry out, a quiet voice spoke in English out of the blackness:

"It's all right," it said. "Don't be scared!"

It was a man's voice, well-bred, a little breathless and, as it seemed to me, a trifle high-pitched from excitement. Still, it was an English voice—and I had not heard an English voice in the six months I had been at Schlatz. Somehow, the familiar timbre seemed to steady my nerves. Still rather tremulous, I answered: "Who are you? What do you want?"

I had stepped back and my hands were on the edge of the writing-table. That blessed light again! The switch of the reading-lamp turned ineffectually at my touch. Now my fingers groped in vain for the box of matches I had left beside the typewriter with my packet of cigarettes. I knew that a candle used for sealing stood on the desk.

A low laugh sounded out of the obscurity.

"It's devilish awkward introducing oneself in the dark," was the reply. "Don't you think we could have some light? It is Miss Dunbar, isn't it? Miss Olivia Dunbar?"

The utter conventionality of his remark went far to allay my fears. The humour of the situation struck me and I, in my turn, laughed.

"Yes," I said, "I'm Olivia Dunbar. But the electric light has failed. Who are you? And what on earth do you mean by frightening me like that?"

"I say, I'm most frightfully sorry, really," the voice broke in contritely. "I had no intention of scaring you. Of course, I thought you'd understand...."

The fright I had received had frayed my nerves. I felt distinctly irritable. This invisible visitor's bland assumption that it was an intelligible proceeding for a complete stranger to burst into a private house at night at the height of a thunderstorm nettled me.

"I don't know what you mean," I retorted hotly. "How am I to know you aren't a burglar, creeping in like that?"

I heard a sharp sigh.

"My gracious goodness, I can't explain things like this in the dark. Can't you light a candle or something? It's simply preposterous, the two of us gassing away here like a couple of blind men. Hang it, I want to see you!"

His outburst had an almost pathetic ring which tickled my sense of humour.

"Not half so much as I want to see you," I gave him back. "Am I supposed to know you?"

"Yes ... and no," was his extraordinary answer.

"Well, give me a match!" I said.

He groaned audibly. "I haven't got one. Have you?"

"There's a box somewhere," I replied, "but I can't lay my hands on it in the dark...."

"Look here, if there's a box about, the two of us should be able to find it..."

My eyes, growing used to the obscurity, could now discern a form vaguely silhouetted against the dim window. There was a brusque movement towards me.

"Stop where you are!" I ordered sharply. "Wait till I find the matches! Do you think I'm going to have you groping about after me in the dark?"

I heard a suppressed chuckle and the movement stopped dead. Then the lightning gleamed and revealed a youngish figure of a man standing bare-headed just within the room. The sight of him, brief as it was, linking up the vague, immaterial voice with a definite individual, steadied me.

"Can't you borrow a light from somewhere?" came out of the dark. "I..."

A long, loud thunder peal drowned the rest of the words.

The sudden noise jarred me horribly.

"No, I can't," I answered crossly. "Everybody's out, and I don't know where there are any more matches."

Scarcely were the words out of my mouth than I knew I had said a foolish thing. Until I had ascertained what this man wanted, I should never have let him know that I was alone in the house. I realised my mistake when I heard a sort of gasp come out of the obscurity and the voice remark:

"There's nobody at home but you, then?"

I made no answer. I was round at the front of the writing-table now, hunting feverishly for those infernal matches. My hand touched the half-open drawer and I drew out the revolver and laid it on the desk beneath a sheaf of typing paper. Then to my intense relief I trod on the box of matches which had fallen on the carpet.

I struck a match and lit the candle in its silver holder. The wick, smeared with the wax of ancient sealings, burned low at first, spluttering, and by its feeble radiance I examined the stranger. I am bound to say that my apprehensions diminished with my first look at him. He was a little, gingery man, rather below medium height, whose outward appearance certainly confirmed the impression I had derived from his voice, namely, that he was a gentleman.

His grey tweed suit, though worn and rather crumpled, suggested a West End cut; and as, the candle burning brighter, the detail of his features became apparent, I saw that he was well-groomed, with thinnish, sandy hair brushed neatly back off his forehead and a small, carefully trimmed moustache. He seemed to be very wet and had his jacket collar turned up against the rain. When I first saw him in the light he was wiping the moisture from his face with what I remember struck me as being an exceedingly unclean pocket-handkerchief.

If I scrutinised the stranger, he appeared to study me with no less interest. As we stared at one another in silence, it struck me that he had an oddly watchful air, like a rabbit at the mouth of its warren. I noticed, too, that his eyes kept travelling from me to the half-open door of the dining-room and thence over his shoulder to the window and the garden, all rustling under the downpour, beyond. They were curious eyes, reddish in hue and set rather close together, with a reckless, almost an unbalanced expression in their depths.

He was the first to break the silence between us.

"You were not expecting me, then?"

Greatly mystified, I shook my head. "If you would tell me your name..." I ventured. But he ignored my lead.

"This is Sunday, isn't it?" he demanded suddenly, very earnestly.

"Certainly," I replied. I was beginning to feel uneasy again. He appeared to be perfectly sober; but didn't those shifting, tawny eyes of his look a little mad?

"Sunday, the 19th of July, eh?" he persisted.

"Yes.

On that he fell into a brooding silence, puckering up his forehead and casting sidelong glances at me from under his reddish lashes.

"You don't happen to know a party whose initials are N.D., I suppose?" he said at last.

"N.D.?" I repeated. "No, I don't think so. Who is he?"

Again he evaded my question.

"And an Englishman hasn't called to see you here during the past few days? Or written?"

"No," I told him. "You're the first Englishman I've seen for six months. You are English, aren't you?"

"Me?" he said absently. "Oh, rather!" Then, harking back to his theme, he demanded again: "And you don't happen to have seen this fellow about the town, I suppose?"

"I don't know what he looks like," I replied.

"No," he rejoined absently, "of course, you wouldn't. Party about thirty, very fit-looking, sort of quiet, with dark hair and very bright blue eyes...."

He rattled this off quickly, then paused, his furtive eyes eagerly fixed on mine.

"No," I said, "I've seen nobody like that about the town. As a matter of fact, I believe I'm the only English person in Schlatz. And now," I went on, rather impatiently, for his extraordinary air of mystery was getting on my nerves, "perhaps you would tell me what I can do for you. In the first place, how do you come to know my name?"

At that, on a sudden, he seemed to slough off his vague and despondent air.

"To tell you the truth," he remarked brightly, "I was asked to look you up...."

"Oh," I said, "by whom?"

"By your people in town...."

I looked at him sharply. Daddy's only brother has a fruit farm in California, and Aunt Sybil, Mother's sister, our only other near relative, is an invalid who lives at Bath. And Purley cannot be claimed as "town" by even the most optimistic of suburbanites.

"You've met my people then?" I replied. "Who was it told you to call?"

He paused for a second, and then answered rather hastily: "Why, your father! You're Colonel Dunbar's daughter, aren't you?"

At that I stiffened. But, noticing how sharply, how eagerly almost, the stranger was eyeing me, I rejoined as nonchalantly as I could:

"Fancy your knowing Daddy! When did you see him last?"

"Oh, just the other day, in London...."

"Where did you meet him?"

"Someone introduced us at a club. The Senior, I think it was. Or was it the Rag? When he heard that I was going to Germany he said to me: 'If you're in the neighbourhood of Schlatz, mind you look up my daughter, Olivia. She's secretary to Frau von Hentsch—Lucy Varley, the novelist, you know—at the Kommandanten-Haus!' A splendid fellow your father, Miss Dunbar!"

"Yes, isn't he a darling?" I replied. My heart was beating rather fast, and I was straining my ears for any sound within the house that should tell me of the von Hentsches' return. But the clock warned me that it was not yet ten; and I could not hope that either they or the maids would be back before eleven. "You ... you haven't told me your name," I continued, as he did not speak and I felt I must say something.

He laughed rather nervously.

"Why, no more I have! It's Abbott, Major Abbott. And now that I've introduced myself, Miss Dunbar," he went on rapidly, "you must let me apologise once again for the way I frightened you. But I was sheltering from the storm under a tree out there, and when that terrific flash of lightning came I suddenly thought of the danger of trees in a thunderstorm, and ... and all that, don't you know, and seeing you at the window I knew at once that you were English, so I just dashed in out of the rain, meaning to explain. And then the light went out. I expect you're wondering what I was doing in the garden. Perhaps I ought to tell you that I wanted to see you on private and very urgent business. Before I rang the front door bell I thought I'd try and find out if you were anywhere about...."

He dashed off this fantastic explanation with the utmost glibness and paused, as though waiting to see what I should reply.

The house was very still. The rain was lessening now, and the thunder had ceased. The storm seemed to have passed over, but there was still some lightning about—I could see the flashes glint from time to time on the gleaming leaves outside the window.

"Well, now that you are here," I said, and tried to banish the nervousness from my voice, "won't you tell me what it is I can do for you?"

He laughed easily. "I'm in the most absurd predicament, really. It's this way. I was going to meet this pal of mine here at Schlatz and travel with him to London. He was due here yesterday; but he doesn't seem to have turned up. As you were the only person I knew here I gave him your name so that he could call—as I'd promised your father to look you up—in my place, in case I didn't have time between trains. That was why I thought you might be expecting me. Do you see?"

"I see," I answered without enthusiasm.

"Coming here in the train this evening," he resumed, quite unabashed, "I was robbed. I fell asleep and when I woke up I found I'd lost my pocket-book with all my money, my bag, my overcoat, my hat, even. If my friend were here I'd be all right, see? And if I could stop over till the morning, I could wire Cox's for funds, of course. But I must get on by the last train to-night. And so I'm in the embarrassing position of having to ask you, as the only person I know at Schlatz, for a loan, a hundred marks or so would do, just enough to buy my ticket. And perhaps if you could borrow a hat for me..."

All this time we had been standing up, he furtive and so very glib, between me and the window, I behind the desk with my hand clutching the revolver under the sheets of paper that covered it.

"Is that all?" I said when he had finished.

At my tone the easy smile fled from his face.

"I ... I think so" he rejoined. "You ... you believe my story, don't you, Miss Dunbar?"

"Not a word of it," I answered firmly.

"But why?" he broke in.

"Because," I told him "my father died three months before I came to Schlatz!"

He was not in the least disconcerted. He ran a wiry freckled hand over his sandy hair.

"My God," he ejaculated, "that's torn it!"

"And now," I said, "perhaps you'll leave this room by the way you entered it?" And with my free hand I pointed at the window behind him.

He stood there, gazing at me forlornly, his pointed features twisted into an utterly woebegone expression, his forehead a mass of furrows.

"But I can't do that," he protested with a sort of desperate air. "Not without some money, and a hat, at any rate!"

"You'll get no money from me, Major Abbott," I retorted very scathingly. "And I strongly advise you to take my offer and disappear before Dr. von Hentsch comes back. He's a German judge and you won't find him as lenient as I am!"

"You don't understand," he exclaimed gloomily. "I can't go. Look here, Miss Dunbar"—his voice grew warm—"be a sport! Think what you like of me; but lend me a hundred marks. You'll get it back and you'll render me a tremendous service...."

"I shall do nothing of the kind," I replied. "You're nothing but a common cheat. Why should I give you money?"

"Because I must have it, I tell you!"

"I'm sorry," I gave him back coldly, "but I can't regard that as a sufficient reason."

He shot a slow glance over his shoulder and remained like that for a moment, as though listening for any sound from the garden. The gesture frightened me, I don't know why, and I disengaged the revolver, but held it down on the desk so that my typewriter hid it from his view. When he turned back to face me, his face was dark with determination.

"You make things very difficult," he said. "But I've got to have that money." And he stepped resolutely forward.

On that I raised the revolver and covered him.

"It's loaded," I warned him in a trembling voice. "If you come any nearer, I'll shoot!"

He halted abruptly and held up his hands in front of him as though to ward me off. It irritated me to find that he was indignant rather than impressed.

"Haven't you been taught never to point a loaded gun?" he cried sharply. "Put that damned pistol down!"

I stamped my foot angrily for, like a fool, I felt I might begin to cry. "Then go away!" I cried. "I tell you again you'll get nothing here!"

But he did not budge. He stood there, facing the revolver which I could not keep from shaking in my grasp, his tawny eyes warm and friendly, a smile playing at his lips.

"By George," he exclaimed, as though to himself, "I like your spirit. I wonder if I dare...!"

At that instant, with a roar that crashed and reverberated through the dripping night, the Castle gun was fired.

Everybody at Schlatz knew the noonday gun.

It was a pudgy, little brass affair, mounted on a squat wooden carriage, its bright muzzle peering down from the age-mottled Schloss wall upon the red roofs of the town. Each day, a few minutes before noon, old Heinrich, the gunner who had left a leg at St. Privat might be descried stumping along the battlements to take up his position beside the cannon, lanyard in hand, eye on the Castle clock, whose dials were set in the four faces of the tower.

As the first stroke of high noon clanged out above his head, the loud bang of the gun would cut across the confused chiming of the mid-day bells down in the town. The other clocks did not always wait for the gun; for the Castle clock was not particularly accurate. It was a stock joke of Dr. von Hentsch's that old Heinrich took his time from the Schloss clock and that the Schloss time was regulated by the noon gun. In all the months I had been at Schlatz, I had never known the cannon fired except at mid-day.

Even as the gun spoke now and the Kommandanten-Haus, according to its wont, jarred and shook to the concussion, I saw my visitor spring back from the window. At the same time, from sheer surprise, I forgot all about the revolver and, still clutching it, my hand sank down upon the desk.

"The Castle gun!" I whispered blankly. "Why are they firing it at this time of night?"

Without replying, the little man sprang to the window, closed it and drew the heavy curtains across. Even as he did so, within the lofty enclosures of the Schloss a wild hubbub broke loose. There came a sudden burst of shouting, a whistle shrilled thrice, a drum rolled. Then the cannon roared again, over-toning the din, and, as the noise of the explosion rolled away, an electric gong, brazen-throated, nerve-racking, like a fire-alarm, began to stutter its harsh summons through the night.

As I stood there, one hand pressed to my heart, and listened to that awesome racket, too insistent for either closed window or drawn curtain to drown, all the dank and clinging darkness outside seemed to be vibrant with dynamic energy. I had the feeling that, at the foot of the hill, the sleeping town was stirring into life, with voices upraised in affright and footsteps that raced madly through its narrow streets.

For the third time the gun boomed forth above the swelling tumult and the windows of the old house started and sang.

"Oh, what has happened?" I asked in a panic. "What does it all mean?"

My companion was cool and brisk.

"It means," said he, and held me with his bright, bird-like eye, "it means that a prisoner has escaped from the Schloss."

"A prisoner?" I repeated incredulously. And then the truth dawned upon me. "You mean...?"

He nodded cheerfully.

"But you're English...?" I faltered.

"I'm English all right," he retorted. "Nevertheless, I've been stuffed away in that damned stone jug up there for thirteen days without a trial...."

People at Schlatz were always talking about the imprisoned officers; but I had never heard of an Englishman being of their number. Many of the prisoners were known to me by name, too; for some of them were quite lionised in conversation, such as the young Hussar lieutenant who, to avenge his wife's honour, had killed in a duel a brother officer, his senior in rank: the offences of others were passed over in silence, like that of Rittmeister von Krachwitz, a horrible, drink-sodden creature—I had seen him about the town—who had "accidentally" slain his soldier servant.

Yet this time it did not occur to me to doubt the statement of my odd visitor. For once his uncanny composure had forsaken him and his words, spoken heatedly, savagely almost, rang true.

Suddenly a lump came into my throat and I felt myself soften to this quiet, tawny little man. I had been many times to the Castle and knew its grim, high walls, its solid, frowning gates, iron-studded, guarding its cloistered intricacy of keep and covered way and courtyard, its ringed system of solemn, pacing sentinels.

My thoughts flashed back to that moment when, the candle flaring up, I had had my first clear glimpse of my mysterious visitant, a little breathless, wiping the rain out of his eyes with his grubby handkerchief, but no more flustered than one who has run for shelter from a sudden shower, he who, with what infinite resource, cool judgment and reckless daring, had but lately burst his way to freedom through massive doors, over lofty escarpments, past lines of guards!

I thought of him, with his gloomy prison at his back and the minutes of the precious start he had gained slipping, one by one, away, almost jauntily spinning to me the foolish yarn, by means of which, without disclosing the truth, he had hoped to enlist my aid. His motive for concealment was not hard to understand. With a rush I realised that this must be an almost incredibly cool and fearless man.

But now, in his clipped and jerky way, he was speaking to me.

"I'm a British officer on duty," he exclaimed. "I can't say more. That should be enough for you, a soldier's daughter, to know. And I've got to get clear away. Never mind about those lies I told you: the service don't encourage confidences. They smuggled a letter in to me up there "—he jerked his head backwards—"giving me your name and saying that Nigel Druce—you don't know him, apparently, but he's another one of us—would warn you to expect me. You've seen nothing of him, you say?"

"No," I answered wonderingly.

"Then he's dead," snapped back my little man, very decisively. "Nigel never missed a date in his life. Listen, you'll help me?"

"Yes," I said.

"How much money have you got?"

I had already picked up my bag from where it lay beside the typewriter and was counting through my notes.

"A little over 300 marks."

This, in those days, was fifteen pounds odd, a lot of money to me.

"Can you spare all of this?"

"Of course," I lied.

He took the notes I gave him and stuffed them in his pocket.

"You'll get it back," he remarked. "Either from me or from my people. If you don't, write in for it. Just drop a line to M.I. 5, War Office, and explain the circumstances. They'll pay you."

With a bland air he rubbed his hands together. "I must have a hat," he announced. "And some sort of overcoat would be useful, too!"

"Dr. von Hentsch's son, who's studying law in Bonn, is away," I replied. "There's an old hat and, I think, a raincoat of his, in the hall. They're not likely to be missed until he returns for the vacation. You could have those. I'll fetch them...."

"Wait!" he bade me. He was looking at the clock. "Half-past ten now: at what time do you expect your people home?"

"Not before eleven at the earliest. The servants are supposed to be in by eleven. But they've gone down to the Kermesse and they're sure to be late. And the von Hentsches are out playing bridge. They mayn't be back until half-past eleven or a quarter to twelve. I don't want to hurry you," I added hesitatingly, "but don't you think you ought to be getting on?"

"There's no great urgency now that they know I've legged it," he answered nonchalantly. "It's always a sound plan to let the first heat of the chase spend itself before one takes to the road. I've got half an hour, anyway...."

"Not if they search the garden," I suggested. "They're bound to think of that, aren't they?"

He wagged his head knowingly.

"Perhaps. Not at once, though. Our German pals haven't got much imagination. I purposely laid a good strong scent on the ramparts on the other side from this, where that market garden comes up to the Schloss wall on the slope nearest the town. I'm trusting that they'll start by following up that clue...."

"Then you escaped on this side?" I broke in eagerly. "Do tell me how! Not by our garden?"

His amused smile seemed to me to confirm my idea.

"But," I exclaimed aghast, "the wall between this and the Castle is frightfully high and all studded with spikes and broken glass. And the door's locked...!"

The door I spoke of was at the end of the garden, a little postern gate set deep in the immensely thick and lofty outer wall of the Schloss, and giving direct access to the courtyard. It enabled the Commandant of Schlatz to enter the Castle from his house without going round by the main gate. When Dr. von Hentsch went into residence at the Kommandanten-Haus, the door, being no longer in use, was locked and the key deposited in the Castle orderly-room.

"Locks can be picked," bluntly retorted my little man. "But," he went on, looking at me with a friendly air, "I'm not going to tell you anything. Bear this in mind, my dear: the less you know about me, the better for you. You've got to forget that you've ever seen me. You're green to this game; but I want you to understand that there's the worst kind of trouble in store for any one suspected of aiding me to escape...."

"Bah," said I, little knowing how bitterly I was to think back upon the foolish boast, "they daren't do anything to me. I'm English. I'm not afraid of them."

The tawny eyes were, of a sudden, thoughtful.

"Don't be too sure. 'Der Stelze' don't stop at anything."

"'Der Stelze'?" I repeated. "That means 'the lame one,' doesn't it? Who is 'der Stelze'?"

I was watching my companion and at my question I saw a curious change come over his face. The features seemed to grow rigid and, for an instant, an odd light, like a tongue of fire, flamed up in his wary eyes.

"God forbid that you should ever run foul of him, my dear," he said, so earnest of a sudden, by contrast with his former easy, almost bantering, manner, that I stared. "But, remember what I say to you now, especially after what has happened to-night! If a lame German, a whopping great fellow with a clubfoot, comes inquiring after me, be on your guard! Don't let him suspect you or ... beware!"

A little silence fell between us. All was still outside now. The tumult up at the Castle seemed to have died away. With a brisk gesture the little man buttoned up his jacket.

"And now," he said smartly, "action front! By reason of what I've just told you, you mustn't get mixed up in this. We're going to put out the candle, you'll fetch me that hat and coat and show me where the front door is. Then you'll cut upstairs to your room as fast as your legs can carry you, nip into bed and stay there until morning...."

"And you?"

He shrugged his shoulders. "Oh, I'm going to finish my job." He extended his hand. "Good-bye, my dear, thank you a thousand times. I wish to Heaven I'd trusted you from the start. But a woman let me down once, and since then I'm being extra cautious."

His lean hand clasped mine. My hands were cold as ice; but his grasp was warm and firm.

"Good luck," I said. "I'm sorry I was so ... so unsympathetic at first, but I didn't understand. Before you go I want to tell you this: I think you're the bravest man I've ever met."

He shook his head and laughed.

"Not brave. Only reckless. As a gambler's brave who's down to his last penny. I left my honour behind when they nabbed me and clapped me in gaol up there. But now, by God"—he pursed his lips into a grim line—"I'm going to fetch it back!"

"Your honour?" I echoed. I wondered what he meant. But his unflinching pluck touched me, and I said: "Listen, Major Abbott, I've done so little for you. Can't I help in any other way?"

He shook his head. "You've been a perfect brick. But there's nothing more you can do ... here."

"Where are you making for?" I asked.

He hesitated and looked at me steadily.

"Berlin..." he said at last.

"Berlin?" I repeated. "Why, I'm going there myself next week...."

He paused, and his eyes narrowed. "The devil you are!" he muttered softly. Then he laughed. "No. You keep out of this. It's no work for a charming girl like you...."

"I'm not such a helpless female as that sounds," I told him. "I'm used to taking care of myself. And I really do know German well. If there was anything..."

He checked me with his hand. "I know. But I've got to plough a lonely furrow." He turned to the desk. "Ready? I'm going to blow out the light...."

At that very moment an electric bell resounded through the house.

The little man was stooping to the candle on the desk. Now he straightened up and looked at me inquiringly. And for the first time his face was really anxious.

"There's someone at the front door," I explained in a rapid undertone.

"Who is it, do you know?" he whispered.

Mystified, I shook my head. "The von Hentsches wouldn't ring. They have their key. And so have the servants."

"Bad!" he commented briefly. "It must be the window for me, then. That path I saw outside the house, does it lead to the road?"

"Yes," I said.

"Good. Shut the window after me, then bolt upstairs and get into a wrapper. Come down, then, and see who's at the front door. I'll watch my opportunity and nip out on to the road...." The bell trilled again. "You can let 'em ring for a bit. They'll think you're asleep."

He tiptoed to the window. "Ready?" he said softly. Then I saw his body stiffen. He held up a warning hand. I listened; and out of the stillness I heard the gentle rustle of feet in the garden.

Quick as thought, my companion bent to the candle and the study sank into darkness. At the same instant another patient, enigmatic ring whirred through the silence. There were vague, muffled sounds in the garden; but not very close to the house, as it seemed to me.

A hot, staccato whisper rasped on my ear.

"You're going to Berlin for sure?"

"Yes, on Friday. Why?"

"If anything should happen to me, can I rely on you to redeem a ghastly folly of mine?

"I'll help you in any way I can."

Our hands met in the dark.

"Listen, then! In the drawing-room of a woman called Floria von Pellegrini, an opera singer, who has an apartment at 305 Hohenzollern-Allee, a sealed envelope is hidden in the gramophone cabinet. It is in the lower part, thrust away behind a lot of old gramophone records, a blue envelope, you can't mistake it. Do you think you could retrieve that envelope without this woman or any one else knowing, and take it to an address I'll give you?"

Feeling rather scared, I answered as bravely as I could:

"I'll do my best. But how can you be sure it's still there?"

"Because the gramophone is never used. Floria hates gramophones..."

His use of the woman's Christian name was to recur to me later.

"If the envelope has gone," he went on, "you'll know that I've been there before you. She gets up late. If you call early, it oughtn't to be difficult. Pretend you've got something to sell, frocks or furs, and the maid—her name is Hedwig—will show you into the salon to wait."

Again that awful bell, patient but persistent.

"And what am I to do with this envelope?" I asked.

"Take it to one Joseph Bale. He's got a theatrical agency in the Tauben-Strasse, one of the turnings off the Friedrich-Strasse, at No. 97. Give him the envelope, in person, only in person, remember. He'll know what to do with it. He's an elusive beggar, but if you say you're a friend of mine, he'll see you at once."

"You can count on me," I said.

He squeezed my hand. "I know you won't fail me. If you only understood what this means to me! I let my people down. And I have to make good. Sure you've got those two addresses?"

I repeated them as he had given them to me.

"Good. The name's Bale, remember. 'A friend of Major Abbott,' you'll say. Got that?"

"Yes," I said.

"Then stand by to shut the window after me!"

I caught his hand as he turned away. "You're never going out there?"

Two long and steady peals in succession resounded from the front hall.

"It's my only chance. There's no knowing what they wouldn't do to you if they caught me here. Besides, for the present it seems all quiet again. Hush, now!"

His hand was on the window-latch. Noiselessly the window swung back. The smell of damp leaves was in my nostrils. And then the little man was gone. The night, moonless, starless, and black under a pall of low-hanging clouds, seemed to swallow him up. Only then did I remember that he had left without the coat and hat I had promised him.

I closed the window as gently as I could, groped my way to the door, and darted up to my bedroom. By candlelight I whipped the pins out of my hair, tore off my blouse and skirt, and dragged on my kimono. Candle in hand, I hastened downstairs again to the front door.

"What is it? Who's there?" I asked, my hand on the latch.

A thick voice answered in guttural English:

"Is that you, gnädiges Fräulein? Please to open quickly. It is I, Major von Ungemach...."

His voice, usually a sort of jolly, jovial bellow, was husky and apprehensive. I scarcely recognised it.

"But what do you want?" I persisted. "I'm not dressed. I was in bed and asleep...."

His heavy hand beat impatiently upon the glass panel of the door.

"Open only! I must see you at once. It is most urgent!"

I swung back the door. Von Ungemach stepped swiftly into the hall. His puffy face was deeply troubled and his pale eyes smouldered angrily. His grey military overcoat was cast about his shoulders, and he carried an electric torch in his hand.

The change in his appearance gave me a sudden feeling of fear. I had never seen the Herr Kommandant like this before. I knew him only as a plump, self-indulgent, amusing creature, prodigiously vain, an indefatigable talker, and untiringly assiduous in his attentions to me. I found it hard to identify him with this grey-faced man, haggard-eyed and curt of speech.

He turned from me to rap out an order to someone invisible in the gloom.

"Stay there with your men at the garden gate," he barked. "You'll let nobody pass, verstanden?"

"Zu Befehl, Herr Major," a gruff voice spoke back out of the night. Von Ungemach took the door from me and closed it. I was tortured with anxiety for my poor little man. Penned in, as he was, in the garden, with its high, unscalable walls, and the gate on the road guarded, what chance did he have?

"One of our people has escaped," said the Major bluntly: he spoke in German; usually he aired his English on me. "It is thought he may have come by way of your garden. You say you were in bed. Did you hear any suspicious sound downstairs?"

"Only the gun," I replied, and wondered whether I looked as terrified as I felt, "and the excitement afterwards."

The beam of his torch swept the bare hall. It fell upon the electric switch beside the door. His hand turned the button; but the hall remained dark.

"Verdammt," he rasped, "the light to fail on this of all nights!" He swung round to me. "You said the Herr Landgerichtsrat was out when I telephoned. Has he come back yet?"

"No," I replied.

"Then, with the gracious Fräulein's permission, I will take a look round. We'll start with the study, as that gives on the garden...."

Familiar as he was with the house, he led the way without hesitation along the passage and through the dining-room, his lamp flinging a shaft of white light before him as he went. I followed, my mind a medley of conjectures and fears. Had my visitor left any trace behind? And what story was I going to tell if the Major took it into his head to cross-examine me as to my movements during the evening?

We had reached the study threshold when a single shot rang out from the garden. With a muttered exclamation von Ungemach dashed into the room and plucked open the window. There fell another deafening explosion without; guttural voices shouted incoherently, heavy footfalls grated on the gravel.

The Major darted out, taking his torch with him, and I was left alone in the dark.

Sick with fear, I leaned back against the door-post, afraid to ask myself what those shots portended....

Doubtless you who have lived through the amazing Iliad of the Great War will count it as nothing that a rifle should crack out across the peace of a German garden, and a man disappear thereafter as completely as though he had never existed. But at the time of which I write the world at large still knew not what manner of thing was this Prussian military system which the spirit that sets liberty before death was to undertake to smash....

I least of all. I was of that generation of the English to the bulk of whom a European war, as a reality of everyday life, appeared a catastrophe as fantastically remote as a volcanic eruption in our Surrey hills. Before that thundery July evening and the events it brought in its train, it never occurred to me that the military atmosphere I found so entertaining at Schlatz—the elegant officers, the bright uniforms, the many parades, with hundreds of stiff legs moving as one in the goose step, and the bands crashing out through the red dust,

"Ich bin ein Preusse,

Kennt Ihr meine Farben?..."

—I never discerned, I say, that all this brave show was merely the fair cover of a ruthless and deadly machine which, while peace endured, crushed those who opposed it at home as mercilessly as later it was to seek to overthrow the world that sprang to arms to destroy it....

Two shots and then silence, but for the growing hubbub of voices under the trees. And I, standing there by the open window in the dark, as Major von Ungemach had left me, trying in vain to read the riddle, wondering apprehensively what I should do next....

The muffled throbbing of a car, the sound of an angry altercation in the hall, and the violent slamming of the front door, decided the question for me. A light glimmered in the passage, and Dr. von Hentsch, in a high state of nervous indignation, burst into the study. He was engaged in a furious argument with his wife, who followed after. He carried the paraffin lamp from the lobby in his hand.

"Shots in my own garden, Donnerwetter," he exclaimed shrilly, "and I'm not to be told what it means? I'll let von Ungemach know exactly what I think of him, keeping me out of my own grounds with his damned sheepsheads of guards!" He set the lamp down on the desk and caught sight of me. "Ach, Olifia," he cried, "what's happening here? Have they all gone mad up at the Schloss?"

"A prisoner 's escaped," I replied rather weakly, for I was feeling terribly upset. "Major von Ungemach came round about it. He's out there in the garden now...."

"Quatsch! Blödsinn! Ridiculous rubbish!" squeaked my host. "A nice state of things, I must say, if they're going to open fire from the Schloss and picket my garden every time one of these good-for-nothing gentlemen chooses to stay out all night with his mistress...."

"Once and for all, Fritz," his wife intervened, but not severely—I don't think Frau von Hentsch could have been really severe with any one—"once and for all, I won't have you say such things in front of Olivia...!"

"Olifia's not a child," the Doctor snapped back. "Like everybody else at Schlatz, I presume she knows that all these fellows in fortress arrest keep women down in the town. But, zum Teufel," he went on in an access of exasperation, "if von Ungemach thinks I'm going to put up with his tomfool melodramatic nonsense, he's very much mistaken. Es ist unerhört! I shall certainly complain to the General."

With a furious gesture he dashed his hands together, and his tubby form vanished through the open window into the garden.

Frau von Hentsch shook her head compassionately, an indulgent smile on her plain but rather charming face. She came across and put her large arm about me.

"Poor Fritz is very cross," she explained. "A soldier tried to prod him in the stomach with his bayonet. Such a stupid man not to know him! One of these Polish recruits, I expect: some of them scarcely seem to understand German. Dear child," she added, looking at me anxiously, "I'm afraid you must have been dreadfully alarmed?"

"I was rather scared," I admitted, very ill at ease.

"Tell me what happened!" she urged....

Dear Frau von Hentsch! How I hated to lie to her! Here was one of the sweetest, most unselfish natures I have ever known. I always thought that the popularity of the Lucy Varley books, those simple tales of American farm life that everybody has read, was largely due to the fact that they were infused with something of my dear friend's Christian kindliness.

Somehow she had contrived to impart this radiant spirit of hers to her German husband. With a wife of his own race I suspect that Dr. von Hentsch, caste-bound, dogmatic, fussy, as he was, would have developed into a bully like so many of his fellow-countrymen. But Lucy von Hentsch, without hectoring or fault-finding, but solely, as I read it, by virtue of her great affection for her husband, appeared to have brought out the best in him. Through all the bitterness of the war years I held fast to my memory of Fritz von Hentsch as an upright and honourable man.

Poor Frau von Hentsch! The war killed her as surely as it killed Kurt von Hentsch, their only son. When Kurt fell on the Somme, Lucy Varley laid aside her pen and wrote no more. But America's declaration of war was the coup de grâce for her who, during more than thirty years of exile, had always remained the staunchest of Americans. Fended by the conflict between her love of country and her affection for her husband, that loyal heart broke, and she died.

I can see her now as I saw her that evening in the study, the last night I was to spend at Schlatz, with her beautiful white hair and her ample, motherly figure moulded in a black velvet gown, exquisitely draped (Frau von Hentsch always bought her frocks in Paris, despite sundry pan-German jeremiads of the Doctor's)—that plump body of hers that used to give her so much anxious thought. ("Child, I know I'm getting to look like a regular, stout old German Frau. It's because I'm just greedy, I guess. But my! their cooking is so delicious!")...

I set my teeth and fibbed. What else could I do? The secret I held was not mine to share with another living soul. So I explained that, growing sleepy over my typing, I had gone off to bed, to be awakened out of my first sleep by the firing of the Castle gun. Lest von Ungemach should mention the fact that he had been kept waiting at the front door, I was careful to add that, when he first rang, I had put my head under the bedclothes, too frightened to go downstairs and see who sought admittance.

As I warmed to my tale, my fears began to leave me. My story was quite plausible, I felt, and, glancing unobtrusively about the study, I could not discover that my visitor had left behind any trace of his presence. But I wished I knew what had become of him! I should have no peace of mind, I felt, until I found out. The echo of those two shots seemed to go reverberating down my memory....

"Well, I declare," exclaimed Frau von Hentsch, when I had done, "I'm not surprised at Fritz getting mad! If I know anything of these Deutschers, there's going to be one most almighty row over this! That von Ungemach must be plumb crazy! I could understand one of those dumb Poles losing his head if he were alone in charge and a prisoner broke loose. But the Major was here himself, you say, when those shots were fired in the garden?"

"Yes," I replied. "He was talking to me here in the study...."

Frau von Hentsch went over to the window and peered into the night. A lantern shone among the trees, and there were voices at the gate.

"I wonder what Fritz is doing," she said. "I hope this man wasn't hit. Did the Major tell you who it was?"

"No...."

"If it were that von Krachwitz creature I shouldn't worry," was her caustic rejoinder. "But I expect the Commandant's doing some thinking. If anything's happened to this man, Major von Ungemach can go out and buy himself a suit of plain clothes, I'll say! He won't want his uniform any more. My goodness, I hope his successor isn't married! I'd just hate to leave this dear old house...."

"But why should Major von Ungemach get into trouble?" I asked. "If a prisoner escapes he has to try and catch him again, hasn't he?

"You've got to remember that all these prisoners are German officers," said Frau von Hentsch, gazing out into the darkness. "And an officer in this country is a little tin god on wheels, even if he is in fortress arrest. This is a military State, my dear...."

Her words touched a responsive chord in my memory. Where had I heard that phrase before that night? Suddenly I remembered my talk with Franz, the postman. What had he said, again? "This is a military State, Fräulein..."—Frau von Hentsch's identical words—"...the civilian doesn't count...." Then in a flash, the rest of our conversation came back to me: Franz's forebodings, his tale of preparations for war; and I thought of my little man and his mission. For the first time I began to speculate about the contents of this envelope, the recovery of which had seemed to be of such vital importance to my odd visitor.

Frau von Hentsch had taken a cigarette from her bag. She stooped and lit it at the lamp.