RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

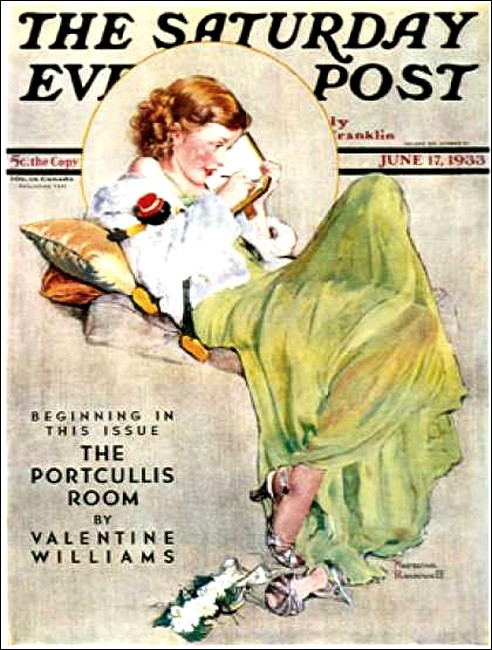

The Saturday Evening Post, 17 June, 1933, with first part of "The Portcullis Room"

"The Portcullis Room," Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1934

"The Portcullis Room," Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1934

AS they cleared the harbor mouth of Port Phadric on the mainland, Hans, chef of the S.Y. Ariel, was putting on the fresh herrings to grill for breakfast. Now the sun of a wan September day was high in the heavens and the smoky blue cloud on the horizon for which the Ariel's bowsprit was pointed had sharpened to the gray hogback of Toray rising stark and steep out of the sea.

For more than four hours Shamus the pilot had shared the bridge with Captain McKenzie in a stony silence. Philip Verity, Stephen Garrison's European manager, to whom Garrison had entrusted all arrangements for the cruise to Toray, was responsible for Shamus. He had picked him up on the quays at Port Phadric and, on discovering that his home was at Toray, had engaged him on the spot to take the yacht across to the island. An undersized, Gaelic-speaking fisherman, monosyllabic and shy, "the English," as he called it, was evidently a foreign tongue to Shamus. His guttural, singsong utterance, his awkward way of framing his sentences, had rung strangely in the ears of the party of New-Yorkers when Verity brought him to the saloon to present him to Garrison. They found his English not even as intelligible as the cook's Hoboken variety, and much less fluent.

Middle-aged and modern-minded and, through long expatriation, probably more sophisticated than the bulk of his fellow Americans, Philip Verity was not in the least inclined to the metaphysical. But in the deep-set, ultramarine eyes of this secretive stranger he seemed to discern an inner light that spoke of second sight and a belief in pookas, pixies, banshees, and other manifestations of the supernatural with which Gaelic folklore is filled. From the first Verity had set his face against this harebrain adventure of Garrison's, urging the extreme danger of navigation along those perilous shores at the season of the equinoctial gales. Although it was he who had brought Shamus on board, he found something vaguely ill-omened in the appearance on the Ariel of this eldritch creature. Shamus was their first contact with the mystic islands for which they were headed and which, strung out along the West Coast of the Scottish Highlands, seem, behind their perpetual curtain of mist, still to dwell in the Celtic twilight. In Verity's uneasy mind the pilot's arrival on board seemed to stress the fact that they were turning their backs on the trolley-cars, telephones, and automobiles of the mainland for the primitive isolation of the outer isles.

In and out of the swiftly moving cloud-wrack a sun of pale primrose slanted down upon the Ariel laboring in the choppy seas of Toray Minch. Since the white cabins and brown nets of the little fishing port had dropped in their wake, Shamus had opened his lips only to give a curt direction to the helmsman at his elbow or to squirt a stream of tobacco juice over the rail. But Captain McKenzie, the sturdy Nova-Scotian who skippered the Ariel for Stephen Garrison, was in nowise disconcerted. Highland himself by origin and habituated to the ways of mariners by a life spent at sea, he appeared to find nothing extraordinary in the spectacle of a man remaining silent who had nothing to say. And so, eyes fixed on the yacht's bows as she shipped it green in the foaming tide race, captain and pilot, two identical silhouettes in sou'westers and oilskins, stood side by side in silent harmony.

Installed in wicker chairs under a shelter abaft the bridge, Garrison and Verity smoked their pipes in the thin sunshine and watched the rugged outline of Toray slowly harden through the haze. For the hundredth time since his employer had first broached to him his crazy idea of leasing or even buying Toray Castle, Verity, listening to the melancholy whistling of the wind in the stays, wondered for how long Steve would put up with the utter remoteness of the fastness they were approaching, one of a chain of similarly savage islets scattered among the boiling Atlantic combers. To a fellow with an income of five thousand dollars a day, of course, all caprices were permitted; but, "if I had a tenth of Steve's money," Verity, with a shake of his grizzled head, reflected, "Newport and Miami would be good enough for me!"

The voices of sea birds crying shrilly in their wake seemed to enhance the brooding silence of the coastline they were nearing. The sun went in and a brisk mizzle of rain enveloped them. Islands, such as these, Verity remembered, were the Ultima Thule of the ancients. It was not hard to imagine, he mused as he gazed at the cloud of spray marking the shore and at the beetling mountain looming above, that the world ended on the far side of that desolate rock. The air was full of noise—the boom of the breakers, the screaming of the birds. With nature so harshly vocal, it was not surprising that man was given to moody silence. Instinctively his eye shifted to the bridge.

Noting the direction of his companion's glance, Garrison laughed. By contrast with Verity's brand-new yachting cap, immaculate blue serge and brown-strapped deck shoes, his attire was lamentably disreputable. An old reefer jacket gaped open upon a grubby white sweater and, as he sprawled in his chair, the peak of his battered cap was tilted forward on the bridge of his nose. As though reading the other's thoughts, "I don't believe your friend Shamus has addressed a solitary word to the skipper since we pulled out of Port Phadric!" he said.

Verity shrugged. "Mac won't notice the difference. Come to think of it, he's not such a chatterbox himself!"

Garrison yawned vastly. "They might do worse than recruit barbers from the Hebrides," he observed flippantly. "Why don't you do something about it, Phil? Come back with us to New York and open the Hebridean Tonsorial Parlor—Silence Guaranteed. I'll stake you."

The other smiled indulgently. Steve could rag like a college boy—it wasn't always easy to remember that he was thirty-two. "I'd rather have Shamus pilot me than shave me. If you think I'd trust a wild man with a razor, even a safety!"

With a grunt his companion shifted his position. "There's something in it, all the same! I've a good mind to fire Dwight and take your Gaelic pal home in his place. Dwight talks too much, anyway. He started telling me all about King Haco and the Vikings when he was shaving me this morning—mugged it up out of one of Mrs. Dean's guidebooks, I guess!" He yawned again, stretched and sat up. "I wonder where Phyllis and her mother are!"

Verity laughed. "I fancy Toray Minch was too much for Mrs. Dean—at least I saw Marie bringing away her breakfast tray untouched. I haven't seen Phyllis yet this morning."

"Then find her for me like a good chap, will you, Phil?" said Garrison with a smile as he stood up. "I'm going on the bridge. We ought to be in pretty soon. Gosh, will you look at those birds!"

The mouth of the loch was opening up between lofty dark brown crags. The rocks were alive with sea birds. At the yacht's approach they swooped aloft in dense white clouds, shrieking wildly, their wings glinting coral-pink against the light. Verity staidly descended the companion to fulfill his errand while Garrison mounted to the bridge.

THE bridge of the Ariel was essentially Captain McKenzie's domain. In acknowledgment of this disposition of values the owner's crisp "Good-morning, McKenzie!" was shaded with a certain deference. Stephen Garrison would not have admitted it, but he never trod the bridge when the yacht was at sea without an uncomfortable feeling that, in this dour Nova-Scotian's eyes, he was merely a passenger, so strong was the atmosphere of discipline the man's personality radiated. To Wilson the mate and the rest of the Ariel's company Garrison was, to the exclusion of all else, the owner, and a millionaire owner at that. But Captain McKenzie was a tougher proposition.

To tell the truth, Stephen, like everybody else on board, stood somewhat in awe of the captain. McKenzie's natural dourness of mien was enhanced by the effects of a war injury, sustained in a 'dog fight' with an enemy submarine in the North Sea, which had wrecked one side of his face, leaving it puckered and partly paralyzed—Phyllis Dean, who cordially disliked him, told her mother's maid that he looked like a totem pole. He had none of the social graces and, from the moment he joined the Ariel at Newport, had shown no disposition to curry favour with the owner's guests. He left them severely alone unless they chanced to wander uninvited on the bridge, when he would speak his mind, politely but plainly.

As to Phyllis Dean, for instance. She had flown with her complaint to her host. But Stephen had merely laughed in that provoking way of his and said the captain was quite right—the bridge was no place for cocktail parties. Phyllis confided to Verity her indignant opinion that the captain was too big for his boots and that it was high time Steve asserted his authority. The incident had occurred five weeks before, a day or two out from New York, but Miss Dean was still extremely distant toward McKenzie.

Her host did nothing about it. Stephen did not consider that his authority was in jeopardy. Of course, no fellow would ever get to know McKenzie well, he was not that kind of man; but he felt that he and the skipper understood each other perfectly. Apart from his appreciation of McKenzie's fine seamanship, he admired him as an individual and was proud to think that, in the short time they had been sailing together, his liking was reciprocated. He paid the captain a good wage, but he was well aware that the latter would unhesitatingly throw up his job sooner than surrender a single one of his principles. Brought up, as he had been, to believe that every desirable object has its price, this point of view intrigued Stephen. It flattered him, too, to find someone whose esteem for him went, not to the millionaire and employer, but to the man.

At Stephen's greeting the captain turned his crabbed, purplish face in his direction and punctiliously touched the brim of his sou'wester, as did the pilot. The shores of a little bay were unfolding before them in the drenching rain. Through the flying spume of the breakers thundering upon the rockbound coast they had glimpses of a dazzling white beach with huge boulders of dark red sandstone piled up behind. The loch, narrowing as it went, wound out of sight, driving deep into the heart of the island. It was ringed round with heathery slopes canting upwards from the edge of frowning, savage cliffs and dominated by the stupendous mass of the mountain, on whose shoulders swollen rain clouds pressed down upon the very crests of the tall, dark firs.

"They should have sighted us by this," Stephen remarked, reaching for his binoculars which hung from a hook. "I daresay they'll be sending a launch or something to show us our anchorage. Of course, they expected us yesterday." He raised the glasses to his eyes.

Captain McKenzie brushed the moisture from his shaggy moustache with his hand and shook his head dubiously. "Too bad about that bearing seizing up, Mr. Garrison." His definitely Canadian way of speaking retained a marked inflection that betrayed his ancestry. "We'd have done better to have crossed yesterday, I'm thinking. It's beating up for dirty weather, sir. It'll be blowing great guns before twenty-four hours are up, I shouldn't wonder, and, with the wind in the quarter it is, the Lord knows, should you be wishful to return tomorrow..."

Stephen laughed. "Don't worry, McKenzie! We shan't be coming back as quick as all that. We may stay a week, or even a month it all depends on what we find at Toray!" The captain said no more, but gazed straight in front of him as though to make it clear that the responsibility was not his.

In his elfin, lilting voice the pilot suddenly broke his long silence. "Wull ye pit her tae half speed, Cap'n?" he requested mildly.

As the telegraph clanged, Stephen took down his glasses. "It's odd," he said. "There's no sign of any boat. They should have had our telegram; Verity wired last night."

"There's nae tallygraft tae Toray, whateffer!" the pilot announced with owlish solemnity.

Stephen rounded on him. "No telegraph? But the post-office at Port Phadric accepted the message!"

Shamus was unperturbed. "The tallygraft, see you, mister? she's tae Ansay, an' they'll aye be deliverin' tallygrams an' such across th' Flow tae Toray. Mussus Campbell's Jamie awa' tae Ansay wull aye hae' to be waitin' on low watter wi' tallygrams for th' castle, see you?"

Stephen turned a bewildered face to McKenzie. "Can you make out what he's saying?" he asked fretfully. "What's a flow, anyway?"

The ghost of a smile played about the captain's hard mouth. "Toray Flow, he means. Ansay, where the telegraph station is, is the next island and Toray Flow's the arm of the sea separating it from Toray. Many of these flows, as they call them, are fordable at low water—they cross them in high-wheeled carts. What he's trying to tell us is that the messenger with your wire had just to be waiting for low water before delivering it!"

The owner chuckled and picked up his glasses again. "It's a grand spot for a rest cure, it seems to me!" he remarked cheerfully, as he adjusted the sights.

McKenzie was speaking to the pilot. "We tie up at the castle moorings, I suppose?" he queried.

Shamus shook his head and, pursing up his lips, ejected a dark stream over the side. "There's nae ower much watter forninst th' castle for what a muckle beg shep like this'll be afther dhrawin'!" he chanted. "Ye'll dae better lyin' up in th' bay, the way her'll be safe when she wull be comin' on tae blaw!"

With the wind and tide behind them they were entering the bay. Patches of bright green grass glinted on the top of the basalt cliffs but soon gave way to the misty purple of heather and, yet higher, to the somber verdure of fir. Under the persistent drizzle the island wore a forlorn and abandoned air, the naked gray mass of the mountain, girt with vapory clouds, hanging like a constant menace above it. Sea birds were everywhere, gulls and guillemots that hung poised above the yacht under the lowering sky or bobbed serenely in the dark green swell, flocks of little puffins skimming the water and here and there, on post or rock, a solitary cormorant with ruffled plumage misanthropically humped. The soft air was continually astir with the flutter of birds' wings and against their strange cries and whoops the silence seemed to come off the land in long, undulating waves. A faint odour of burning peat was mingled with the strong tang of the drifting tangles of seaweed.

As the Ariel, long and white and graceful, majestically steamed into the loch, a tower, dark red like the crags that sentineled it, began to lift above a bluff round which the loch wound itself out of sight. With the yacht's advance, crenellated battlements, and chimney-pots, and lines of windows began to appear, a crazy huddle of buildings clinging about the squat central tower, until the whole mass of Toray Castle stood disclosed. Stern and rugged as the rocks from which its stones were hewn, its somber silhouette gave the crowning touch to the spectacle of desolate majesty which the glassy, dark loch, ringed with its solemn hills, presented.

A splash of vivid blue was visible below on the deck. Phyllis Dean in a bright pyjama suit with a striped vest and a French matelot cap with a scarlet pompon atop appeared, accompanied by Verity. With a glance to secure the captain's permission Stephen hailed the girl.

"Hey, Phyllis," he called, "come up and see the castle!"

The girl's arresting loveliness seemed to lighten the strictly utilitarian setting of the bridge—here was the sort of blond beauty that glows with the vividness of bougainvillea in flower. Stephen slipped his arm into hers. "There it is!" he proclaimed with finger pointing. "Isn't it a marvelous old place? And did you ever see such a gorgeous setting?"

"Quaint old dump!" said the girl. "Do you suppose they have a bathroom?"

Stephen laughed quietly. "I should think it very probable. The laird is quite civilized, you know. He used to be an officer in one of the Highland regiments!"

Phyllis shivered. "Any four walls and a roof that don't keep pitching about are good enough for me. That goes for Mother, too. She's been frightfully ill; I thought she'd pass out on me." Her tone was fretful. "Does it ever stop raining here?"

"Sure," Stephen cried gaily. "We've just hit a wet spell, that's all. The climate in these islands is the mildest in Britain, the guide-book says!"

"That's the hell of a recommendation," the girl remarked disgustedly. "I think you're simply goofy to want to come to a gruesome spot like this, Steve, when we could have gone to Gleneagles and had a simply swell time playing golf and dancing. That reminds me—that wretched Marie left my face cream behind in the inn at Port Phadric. Could you have Dwight telephone back and ask them to send it on?"

"I don't believe they've got the telephone on the islands..." His glance consulted the pilot. "Have they, Shamus?"

"There's nae tallyphone tae Toray, whateffer!" was the phlegmatic rejoinder.

Phyllis pouted disgustedly. "What a place! Then Dwight'll have to wire. Will you tell him, please, Steve? It's urgent. Every scrap of cream I brought with me from New York is in that case of mine!"

Her host looked embarrassed. "The only thing is, honey, that the telegraph doesn't seem to be working!"

"Not working?" she exclaimed sharply. "Then how am I going to get my cream?"

"It doesn't make a scrap of difference whether the telegraph is working or not, Miss Dean," the captain now struck in. "The boat from the mainland calls with the mails at Toray only twice a week—Tuesdays and Thursdays—and the post office at Port Phadric is likely to be closed before the inn people would have time to act on your wire and catch the Tuesday boat tomorrow and they'll dispatch your cream by Thursday's boat."

"And what am I to do in the meantime?" the girl demanded indignantly. "Madame Jeannette makes up this cream especially for me and I can't use any other; my skin won't stand it. Steve, you've got to do something about it!"

Stephen patted her shoulder. "That'll be all right, honey. They'll fix you up at the castle for a day or two or tell us where we can get you some cream at one of the shops." At this the captain turned his head and looked sharply at the speaker. But he said nothing and Stephen went on, "You cut along now, sweetheart, and get dressed. Phil and I are going ashore to investigate!"

"I suppose I'll have to use that foul cream of Mother's," Phyllis ejaculated crossly. With an expression of unconcealed dismay upon her smooth young face she let her glance travel round the mournful panorama of sky and mountain and water. But no one was paying any attention to her. The engine-room telegraph had clanged, the yacht was slowing down. The captain and Shamus were in conference; Stephen was giving Verity instructions. With a woebegone air the girl left the bridge.

STEPHEN GARRISON was a restless soul. He hated to be kept waiting, when he wanted anything, it had to be done instantly, as Dwight, his long-suffering manservant, knew full well. Verity would have liked to go ashore comfortably in the very elegant power boat which the Ariel carried slung on her after-deck, with the pilot to show them the channel. But this did not suit the owner's impatient nature at all. They had reached their destination: he must go ashore. He would not wait for the power boat to be launched, he would not wait for the pilot, still occupied with the task of bringing the yacht to her anchorage. Nothing would suit him but that he and Verity should put off in the dinghy without an instant's delay; they could come to no great harm in the little dinghy, he told Verity, whose mind was filled with visions of shoals and currents and whirlpools. So the dinghy was lowered and towed round to the accommodation ladder and they set off, Stephen, as excited as any schoolboy, at the oars.

Beyond the bluff the loch opened up again and they came in view of the castle mirrored at full length in the darkling, unruffled water. It stood right on the edge of the loch, rising from a rocky platform washed by the high tide and protected from the fury of storms by a lofty rampart. The rampart was pierced by a low arch with a flight of worn steps leading down to the water.

Between the channel they were threading and the castle, a battered wooden jetty was thrust out from the shore. Here three or four tiny whitewashed houses with thatched roofs were huddled above the beach with sign-boards above their narrow entrances, from his seat in the stern of the dinghy, Verity read Post Office and Donald McDonald, Grocer, thought of Phyllis and her face cream, and smiled. Some ragged children lined the quay, staring at the intruders in a frightened silence. The four or five hundred yards separating the jetty from the projecting rock on which the castle was built was spanned by a rough track where a few miserable cabins, each with its brown peat stack and line of nets hung under the eaves, were strung out. The two Americans were conscious of faces peering at them out of the dimness of low doorways, as the boat, with rowlocks, softly thudding, glided by.

In the comparative shelter of the landlocked sea, the thunder of the waves upon the rocks in the outer bay was now no more than a deep murmur in their ears. Little sounds were wafted to them from the misty shore—the barking dog, the bleating of sheep high up among the heather, the distant clatter of a cart.

The dark mass of the castle, however, remained inhospitably silent. No smoke arose from its innumerable chimneys; the flagstaff that crowned the top of the central tower was bare; and most of the windows visible appeared to be shuttered.

Such details Verity made out as, to Stephen's vigorous pulling, they neared the steps. Contemplating the rugged pile the man in the stern marveled to perceive how cunningly it was disposed to withstand surprise attack by foes. In front was the loch, behind the soaring sugar-loaf of Ben Dhu, rearing its grizzled head so steeply that it seemed a man from its summit could look straight down the laird's chimneys. Tall firs, with gaunt white herons perched on the topmost branches, screened the house from winds blowing up and down the loch and from the mountain. From the slopes behind, the thin blue smoke of heather fires, where the land was being cleared, strayed under the low ceiling of mist, the only sign of human presence. The silence was so profound that Verity could hear the plovers shrieking on the mountain-side and the hollow sound of the row-locks, and the quiet drip of the water, as Stephen dipped his sculls. In the deathlike hush of the place he found himself once more invaded by the unaccountable misgivings which had beset him ever since their departure from Port Phadric.

It was high water and the lower part of the steps was awash. They fastened the painter to a huge rusty ring riveted in the rock and mounted the stairs, scooped out with the feet of the centuries and slippery with kelp and barnacles. From a landing under the archway a short flight, which showed signs of repair with concrete, led up to an immensely solid, iron-studded door. A bell-handle, eaten with rust like all the ironwork they saw, hung down beside it. Stephen tugged it vigorously. A chain squeaked and a bell, as solemn as a convent's, clanged twice.

There was no response and, after an interval, Stephen rang again. Once more the bell tolled through echoing emptiness. Still no one came. Verity doffed his smart new yachting cap and tugged at his ear. "Well, there you are!" he said. "There's nobody home. We'd have done better to have sent Shamus ashore with a note in the launch and lunched comfortably on the yacht, as I suggested."

"Damn it, there must be servants about!" cried his companion and plied the bell-handle again.

"You're a real American, Steve," Verity remarked complacently. "Always in such a hurry to go places!" And, surveying him scathingly, he added, "And a nice sight you look, I must say, to go calling on a Scottish chieftain! That jacket of yours is a disgrace and your sweater's filthy! Of course, you couldn't even spare the time to change! I made Dwight buy you a new yachting cap at Southampton—he promised me to throw that old one away. Why on earth couldn't you wear it?"

Stephen laughed good-humoredly and ran his eye over his costume. "I suppose I do look a bit of a bum!" he agreed with equanimity. "But I do love old clothes. Never mind, Phil, I'll tip the laird a dime and he'll think I'm John D. Rockefeller!" He broke off. "Say, are they all dead in this blooming castle or what?"

He had just laid hold of the bell-handle again when a hollow voice resounded close at hand. "What wad ye be wantin'?" it boomed. The visitors then perceived that a grille had opened in the door and a pale, bearded face was looking out.

It was Verity, who was wont to call himself, jestingly, Stephen's "contact man," who responded. "This is Mr. Garrison, Mr. Stephen Garrison," he announced importantly. "He'd like to see Mr. McReay!"

The door remained immutably closed. The face at the trap—it was the face of an old man with an immense spread of gray beard—replied sternly, "The McReay's fra' hame!"

He was about to close the trap, but Verity stopped him. "But Mr. Garrison wired Mr.—er—the McReay, from Port Phadric yesterday that he was arriving today. Didn't you receive his telegram?"

"I dinna ken annything aboot it," was the uncompromising reply. "The laird is nae here!"

"Then where can we find him?" Stephen now struck in—perceiving that the old man was about to shut the grille, he had thrust his fingers between the bars.

"Ye micht be askin' after him at the factor-r's?"

"The factor's?" Stephen repeated, puzzled.

"He means the bailiff—Mr. Jamieson." Verity explained in an undertone. "McTaggart, McReay's lawyer in London, mentioned his name." He turned to the trap again. "And where do we find the factor?" he demanded.

"'Tis the big stane hoose ahune th' vullage!" was the curt answer. With that the trap was closed so swiftly that Stephen had a narrow shave of having his fingers pinched.

"Well, that's that!" Stephen observed with his imperturbable grin. "We'd better go and hunt up this factor guy." He broke off. "Hullo, what was that?"

The sharp crack of a shot had come rolling down the mountain, followed, almost immediately, by a second report. "I bet the old boy's up there, taking a pot at the grouse," Stephen declared positively. "I'm going to find him. The sooner he knows we're here, the better I shall be pleased. The old beaver behind the bars doesn't seem to know it, but McTaggart told us the laird would be glad to put us up and I've no intention of letting Mrs. Dean and Phyllis spend the night on the yacht if, as McKenzie says, it's coming on the blow."

"Aw, pshaw, Steve, you're crazy," Verity replied. "How do you know it's McReay shooting up there? We'll only get lost in the mist!"

"Don't worry," his companion told him placidly. "You're going to dig out the factor. Whichever of us first comes across the laird, brings him here. There's a patch of beach beyond these steps where you can land me. Come on, boy, let's step on it!"

With Verity still protesting that Stephen had much better accompany him to the factor's, they descended the stairs to the dinghy.

To reach the grassy slopes above the beach Stephen had some rough scrambling to do among the boulders of the foreshore. A sheep track upon which he blundered, after he had made various ineffectual attempts to burst a way through the heather, eventually brought him out upon a path which, above him, coiled itself about the flanks of the mountain and, below, disappeared in the belt of trees screening the rear of the castle.

With scratched hands and sopping shoes, bathed in perspiration and panting for breath, he paused to rest. He always prided himself on being fit, but, as he felt his heart thumping against his ribs, he realized that shipboard life had made him soft—for five weeks he had not thrown his leg across a saddle or touched a squash racket. He sat down on a rock and, surveying the view, discovered that the rain had ceased and that, under a warm sun and a blue sky, the waters of the loch had turned from a blackish green to a deep azure. The birds were singing, there were butterflies among the heather and bees made drowsy noises in the air. He was suddenly conscious of a great joy at being alive, at having come to Toray. He was glad that the weather had cleared up on Phyllis' account; he wanted her to have a good time. A sweet kid! He wagged his head approvingly and groped in his pocket for a cigarette.

The sound of whistling coming from behind, as he sat with his face to the loch and his back to the mountain, reminded him that he had heard no more shots. He looked round, then stood up. A boy in plus fours, whistling rather discordantly, came swinging down the track.

It was a mere lad, who carried a double-barreled gun on his shoulder and a stained canvas haversack slung at his side. He wore a disreputable old tweed hat with salmon flies stuck in the band and a shabby shooting coat of brown Harris check several sizes too large for him. His thin legs were encased in tartan stockings which ended in a pair of well-worn and well-greased brogues. A red setter rambled at his heels.

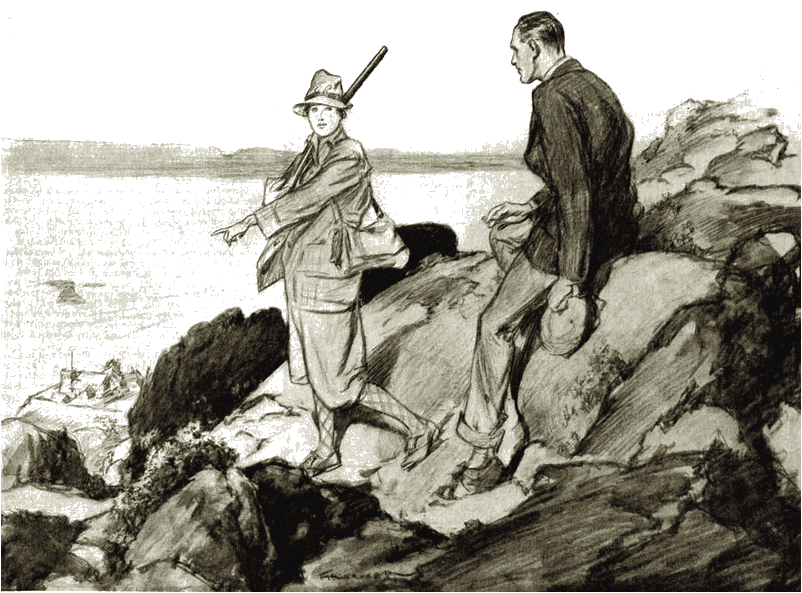

His eyes cast down as he picked his way along the broken path, the youth did not see Stephen until the latter hailed him. "Excuse me," the American said, "is Mr. McReay up there?"

The lad had abruptly stopped his whistling and was considering the stranger with every evidence of extreme suspicion. Stephen told himself he had never seen a pair of eyes so brightly blue—with their long, closely set black lashes and slight, delicately penciled brows they gave the smooth, young face quite a girlish expression. Then, as the newcomer spoke, he had a sudden shock of surprise—the timbre of the voice made it apparent that the speaker was a girl.

"Then you got my telegram?" he replied eagerly.

She shifted her gun to the other shoulder prior to resuming her descent. "It's no use your trying to see the McReay," she answered coldly, "because he won't see you!" And with a wriggle of the shoulder to readjust the position of her haversack—the speckled plumage of a grouse was visible under the canvas flap—she stepped past him.

"But wait a minute, can't you?" Stephen protested. "The laird's expecting me!"

"I know all about that," she retorted with the same air of unyielding hostility. "But you'll no see him. And the sooner you and your friends take yourselves back to the mainland the better!"

The American laughed. "Correct me if I'm wrong," he said pleasantly, "but I get the impression that we're not welcome at Toray!"

As he spoke he let his quizzing glance rest on the blue, angry eyes. She was quite young, he judged, not a day over eighteen, and slim and straight as any of the young birches that grew about them. Her voice was low and warm and plaited with the faintest Scottish inflection that he found infinitely pleasing. She was obviously gently bred, too, for all her funny clothes—the small brown hand that clasped the gun butt was well-kept and finely made.

Her face whipped into color by the morning's rain, was evenly browned, but the glimpse of arm he had under the sleeve of her shooting coat was milky white. A wisp of hair that straggled from under the brim of her woeful hat was raven-black and lustrous—blue eyes, black hair, this was the true Highland type. He wondered who she might be. McReay had had a son, now dead; but there had been no talk of a girl—perhaps she was the factor's daughter. Whoever she was, he was prepared to like her—there was a little haughty expression stamped upon her small grave features which stirred some far-off, untouched hunter instinct in his blood.

With a scathing air she looked him up and down. "Will you please understand," she said—try as she might, her voice was not very firm—"that there's nothing left here for you and your sort to plunder. Good morning to you, Mr. Berg or whatever your name is!"

"There's nothing left here for you and your sort to plunder."

So saying she clutched her bag of grouse to steady it and started running down the steep path. "Come back!" he shouted. "My name's Garrison!" As she paid no heed, but went on scrambling down in and out of the boulders, he set off in pursuit. She had him soon outdistanced—on the stony, broken track she was as nimble-footed as any chamois.

He was standing there, looking after her, when he heard his name called. Turning about he perceived Verity up to his middle in the heather on the high ground above him, with scarlet, irascible face, waving frantically to him.

"My goodness, Steve," Verity observed fractiously, when the other had joined him, "what a dance you've led me! I've been almost to the top of that damned mountain looking for you! Listen, the laird's away on the other side of the island until this afternoon. But I've seen Jamieson and it's all right; they're expecting us up at the castle. We're to go ashore for tea; Jamieson's coming on board to fetch us at four o'clock. He'll have a cart at the jetty for the baggage. Is that okah with you?"

But his friend disregarded the question. "Phil," he said suddenly, "do you know whether McReay has a daughter?"

"I don't believe he has any children. His only son's dead."

"I know that. Has Jamieson, or whatever his name is, a daughter?"

"Yes."

"Rather tall and slim, with——"

Verity laughed. "I can't tell you how tall she is. She was in her perambulator when he introduced us. Are you aware that it's half past two and that we haven't had lunch yet? Don't you think we might go back to the yacht and Hans to fix us a snack? Or do you propose to spend the afternoon here and lunch off heather like the sheep?"

The other sighed. Oh, all right. Lead on! The trouble about you, Phil, is that you have no soul. Just another Babbitt! The sordid commercial existence you lead has crushed all the romance out of you."

His companion chuckled tranquilly. "Oh yeah? Well, if it wasn't for my sordid commercial activities and the sordid activities of a couple of other Babbitts like me in New York and Chicago, you'd be selling apples, Steve, my boy!"

And a darned good job of it I'd make!" Stephen declared.

Verity laugher uproariously. "You! Why, you couldn't land a first payment on a fire extinguisher in one of those villages on Vesuvius!"

Thus amiably sparring, as was their invariable wont, they descended to the beach.

FOR their meeting with the laird Mrs. Dean had put on the new and very smart check tailor-made she had bought in Edinburgh on their way through and her two strings of pearls. "You can't go far wrong with tweeds in Scotland, I always say," she told her daughter, as she stood before the mirror in the cabin they shared, and tried the effect of the natty little scarf that went with the suit, "although, I suppose, being in a castle, we'll have to put on all our fal-lals in the evening. I wonder if he'll wear a kilt. I looked up the McReay tartan in that book they gave us at the tweed shop and it's most becoming. And that reminds me, darling," she went on, surveying her firm, pleasant face in the glass, "I do hope you are going to try and be a little more enthusiastic about the Highlands while we're at the castle. Really, ever since we left Edinburgh, you've done nothing but grumble. I'm afraid Stephen will begin to notice it."

"You weren't so madly enthusiastic about the Highlands yourself during the crossing this morning, as far as I remember, Mother," Phyllis retorted, scanning her nails, manicure pad in hand.

"When you get to my age, darling," Mrs. Dean replied placidly, "you'll realize that nothing worth while in life is achieved without sacrifice. I loathe the sea and even the sight of a ferry makes me feel queer; but do you suppose I think of that when my daughter's happiness is at stake? In my young days, of course, girls were better disciplined. Why, when I was your age, if an attractive bachelor with all Stephen Garrison's money had invited Mamma and me to go on a cruise with him, do you imagine for a minute, however bored I might sometimes be feeling, that I'd have ever shown it!"

Phyllis sighed heavily. "Are we going to have all that over again?"

"No, but, honey, I must just say a word to you—I've been meaning to for several days. For the moment Stephen's got this fool idea in his head that he would like to have a Highland castle. Men get these crazy notions—I remember that at one time your poor father was always talking about going out to the South Seas and settling down—and they have to be indulged. I wish you'd remember that men hate to be snubbed."

The girl put her manicure pad in her bag and snapped the lid briskly. "You don't have to worry about Steve, Mother. I can handle him all right."

Mrs. Dean's eyes narrowed anxiously as they sought her daughter's face in the mirror. "He hasn't asked you to marry him yet, has he, Phyllis?"

A spot of color crept into the lovely face. "I do think this matchmaking business is abominably vulgar. There are other men in the world besides Steve Garrison, aren't there?"

"Of course, darling. But you do like Steve, don't you, honey? And he's simply crazy about you—I've noticed the way he watches you. And I do hope"—her tone was suddenly apprehensive—"that there's not going to be ant hitch. I mean, after all, I gave up the most attractive invitation to the Wakefields' camp at Lake Placid to chaperon you on this trip, so I think I'm entitled to just a little consideration."

"We'd better go," Phyllis broke in. "They sent down to say the launch was waiting ages ago!"

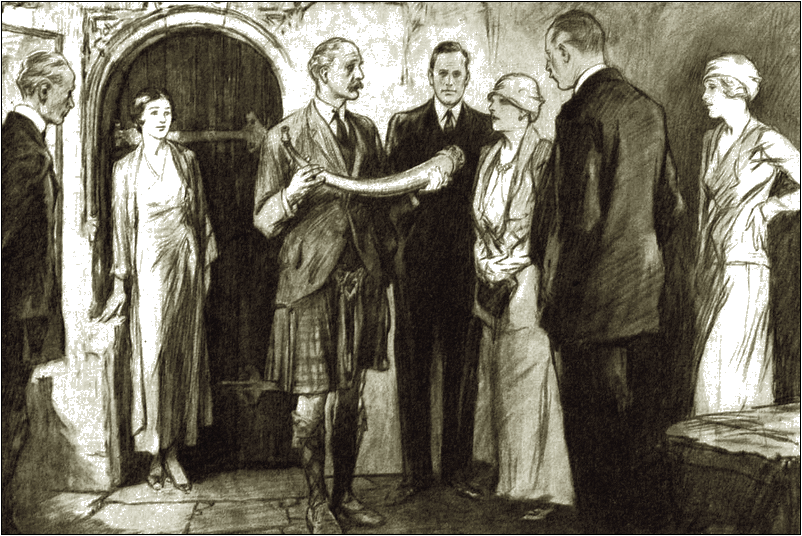

The Ariel's luxurious motor-boat halted at the little jetty to deposit Dwight and Marie, Mrs. Dean's French maid—both somewhat disapproving—with the visitors' luggage. As the tide was only an hour or so past full, landing the luggage at the sea gate, as he called the entrance to the castle from the loch, might prove awkward, the factor said, with a glance at the array of suitcases. Mr. Jamieson was full of apologies for the unfriendly reception accorded to the two Americans that morning. The usual approach to the castle, he explained, from the land side, in the rear; the sea gate was little used. Old Duncan, the laird's major-domo, was a privileged servitor, a "verra independent" man, who waged a relentless warfare against the trippers who sometimes visited the island in the summer; Mr. Jamieson hoped that Mr. Garrison would realize that no discourtesy was intended. The islanders were "verra peculiar" people, it was not the "fairst" time he had had occasion to complain of old Duncan's crotchety ways.

A friendly, albeit desperately serious, little man, Jamieson, who, as a Lowlander—he was "fra' Peebles," he explained—and appeared to regard all Highlanders with cold reserve; indeed, he wore the rather aloof air of one whose life is cast in heathen places, but who is resolved to make the best of it. They would land at the sea gate, he said, because he was anxious that the party should receive its first impression of Toray Castle from its most ancient part, the thirteenth-century keep, which he pointed out to them as the launch nosed its way down the loch, as the massive pile that arose foursquare behind the protecting sea rampart.

This time the great iron-studded door stood wide, Stephen observed as he turned from helping Phyllis and her mother from the boat. A gaunt old man clad in rough brown tweeds stood in the entrance. He had a great spade-like gray beard and to protect his bald pate against the damp air of the passage where he waited wore a battered Glengarry cocked on one side of his hoary head. As the women came up the steps, he doffed his bonnet, flattening himself against the wall with features impassive and eyes coldly vigilant.

Spry as a sparrow, little Jamieson led the way under the hoary arch. The passage beyond was dank and forbidding, the rock from which it was hollowed streaming with moisture. He pointed out the timber hatch masking the mouth of the well which at one time supplied the garrison of the castle with water and showed them, beneath the vaulted doorway at the end of the passage, the wall deeply grooved on either hand for the portcullis. A door now replaced the portcullis, opening upon a square stone lobby dimly lit by arrow slits and decorated with trophies of arms and sundry cases of stuffed birds. Here the major-domo, with grave dignity, relieved them of their outdoor things, on which the factor, with a hasty glance round to make sure that the party was complete, opened a door in the wall and motioned to Mrs. Dean to precede him.

A long chamber, so high that its rafters and the dusty banners they displayed were almost lost in gloom, unfolded itself before them. To a height of about twelve feet it was paneled in oak blackened with age, the smooth stone walls that rose above the wainscot hung with panoplies of targets and claymores. Down the right-hand side of the room a series of windows, hollowed out of the enormous thickness of the walls, commanded views of the loch. In the opposite wall other casements framed glimpses of a neglected garden whose weed-choked flower-beds swayed sadly in the eternal sea-breeze.

This was the great hall of Castle Toray. Here, in days of yore, the chieftain had feasted his followers by the light of pine torches, whose sconces of rudely beaten iron, as Jamieson pointed out, still remained round the hoary stone walls. It was a somber, darkling place even in the afternoon light with its massive oak furniture, as black as the wainscot, and its vast stone fireplace, carved with the McReay arms and colored, like a meerschaum pipe, a rich creamy yellow by the smoke of centuries. Everything spoke of the unarrested process of decay—the worm-eaten oak, the curtains of faded red rep that trembled to the wind plucking at the casements, the threadbare rugs strewn at intervals upon the immense flags, polished with age and darkly shining, of the floor. That it was still the chief living-room of the castle was shown by the flowers and books that were ranged about, by the refectory table set for tea and by the gramophone cabinet—almost the only modern note—between two windows. Despite an enormous peat fire leaping on the hearth in a great iron, basket, the atmosphere was chill and acrid scent of the burning turf could not banish a faint odor of mustiness.

A couple of red setters that had been snoozing before the fire sprang up as the party entered, rending the air with their furious barking. At the far end of the hall was a gallery from which a stone staircase with an elaborate, carved balustrade descended. A sharply commanding voice now rang out, "Down, Laddie! Down, Rover!" as a figure was seen coming down the stairs.

It was a slightly built man in a kilt, whose face was of an ivory pallor, with light lashes and sparse reddish hair turning white. The features, especially the long, dipping nose, were lean and aristocratic and he wore the Highland dress with splendid dignity, a jacket of light tweed and kilt of the McReay tartan, in which dark green predominated crossed with lines of red and yellow.

With quite a regal air he waited while Jamieson, a little flustered, presented the visitors. "I owe you an apology, Mr. Garrison," said the laird, giving Stephen a limp hand, "for being from home when you and your friend called this morning. But telegraph facilities on the islands are restricted and I've only just received your telegram. There's quite a sea running in the Minch today, they tell me, and in the circumstances I believed you'd repented of your intention to come to Toray. Now that you are here, however, will you let me bid you welcome and say how much I hope that you and your friends will enjoy such meager hospitality as the castle is able to offer you for as long as you see fit?"

He made his little speech in a formal, precise English, with a faint Scottish burr, at the same time caressing the head of one of the setters which nuzzled at the hem of his kilt. "I don't know," he went on with a smile, "whether tea is in your American habits, but it's quite a rite with us. I thought we might take a cup together and then I'll show you your rooms!"

Mrs. Dean laughed. "We don't have to be converted to Scottish teas," she said. "We all think those scones and bannocks and things you serve are simply divine. I don't know about Phyllis, but I've put on at least ten pounds since I arrived in Scotland and Mr. Verity there is just as bad." She paused. "But before I sit down I must ask you a question how does one address a Scottish chief?"

The laird smiled. "That's simple. In the Highlands we derive our title from our landed possessions. I am the McReay of Toray, and so I'm usually addressed simply as 'Toray.'"

Mrs. Dean simpered. "It sounds very familiar!"

The laird shrugged. "Nevertheless, it's the custom!" He broke off. "But here's my daughter!"

A young girl with rather a heightened color emerged hastily from under the gallery. Her lustrous black hair was gathered in a small knot on the back of her white neck and she was wearing a little blue frock. "You've taken us all unawares," the laird explained to Mrs. Dean. "You must forgive Flora for being late, but she was out on the mountain walking up the grouse."

Stephen, who was scrutinizing one of the panoplies of arms, was oblivious of the new arrival until Jamieson plucked his arm and he found himself staring into a pair of very blue, rather puzzled eyes. He heard Toray's smooth, rather precise voice introducing him and took the small, brown hand the girl offered in silence. He could not resist the temptation, however, to give her a humorous glance. Seeing which, she coldly withdrew her hand and went to the table where the major-domo and an elderly maid in cap and apron were setting forth the tea.

IT WAS evident that the factor had made the history of Toray Castle his especial subject. Seated at the long table where they were gathered about an imposing spread of hot scones, and oat-cake, and shortbread, and bannocks, between Mrs. Dean and Stephen, he held forth in his dry, rather grating voice. Romantic names rolled sonorously from his tongue—Ranald Dhu or Dark Ronald, the doughty warrior who had built the keep, the original castle, even the very hall in which they sat; Red Calum, who had added the tower; and that later Calum, head of the clan McReay, massacred at Culloden with the greater part of the hundred followers he had put into the field in support of the ill-fated Charles Stuart.

The little man had the air of licking his lips over the record of rapine and bloodshed of which the family history seemed to be largely made up. Verity, listening quietly from his place at the end of the table beside Flora McReay, who presided at the silver tea-service, was diverted to hear him dramatically proclaim, "And the laird pit tae the sworrd every one of the McNeils, man, wumman, and child!" or introduce some fresh episode in the annals of Toray with the words, "One of the bluckest deeds in the whole annals of the Hielands."

He would have preferred to hear the laird on the family history, the American told himself. A slightly cynical bachelor of fifty-five, Philip Verity liked to study types. He found himself keenly interested in the personality of their host. Covertly he observed Toray as Jamieson droned on, noting the evidence of ancient lineage and centuries of inbreeding in the long, pointed features, the curiously elongated chin, the flossy, silken texture of the hair.

As he scrutinized the laird, he was gradually aware that Toray was laboring under some extreme nervous strain. Verity knew from McTaggart, the McReay representative in London, that Toray was seriously embarrassed for money and that only his extreme financial straits had induced him to consider leasing or selling the castle. As his eye rested speculatively upon the pallid, harassed countenance across the table, the American asked himself whether money difficulties alone would account for the desperately anxious look that, from time to time, flitted like a shadow athwart the reddish-brown eyes. Toray was not merely content to let his bailiff monopolize the conversation, Verity perceived; his mind was miles away. He fussed with his teacup without drinking; he crumbled a piece of shortbread in his saucer without eating; he took a cigarette from Stephen's case and let the factor light it for him, only to lay it down at once: and when Stephen put some question to him about the castle dungeon upon which Jamieson was dilating, started violently before replying.

Practical man of business that he was, the American might have been willing to disregard his first impressions of the host, had they not been in a measure corroborated by the deportment of the daughter. The girl scarcely opened her lips as she manipulated the old silver teapot. In face of Jamieson's determined volubility, there was little opportunity for general conversation. But Verity, who was her neighbor, tried to draw her out with a remark about the shooting, without, however, any very promising result. She replied in monosyllables in a low tone. Noticing that her voice was unsteady, he glanced at her more closely and saw that she, too, was highly strung—indeed, he thought he could discern about her eyes signs that she had been weeping. In the circumstances he forebore to thrust his conversation upon her further and she remained in a forlorn silence behind the tea things, eating and drinking nothing, apparently content to observe Phyllis Dean, from whom she seemed scarcely able to take her eyes. In a chic little Paris-tailored suit of pale gray Shetland with the nattiest white hat, Phyllis was, indeed, at her loveliest, even Verity, who was not particularly friendly to her, had to admit. Her flowerlike beauty was like a shaft of sunlight in that somber place.

An angry sky was reddening the windows overlooking the loch. The wind went whistling round the castle. Within the great, dim chamber the dusk was beginning to fall and presently old Duncan, the major-domo, stalked in with a taper to light the candles in the massive silver candelabra which stood on the table. Letting his glance shift from one to another of these two, father and daughter, only survivors, as he knew, of an ancient and illustrious line, Verity found himself wondering what secret drama was being enacted in that ancient house, far removed from the hurrying life of the modern world. Was it, he pondered, the aftermath of the tragedy of young McReay, whose premature death had extinguished the laird's last hope of succession?

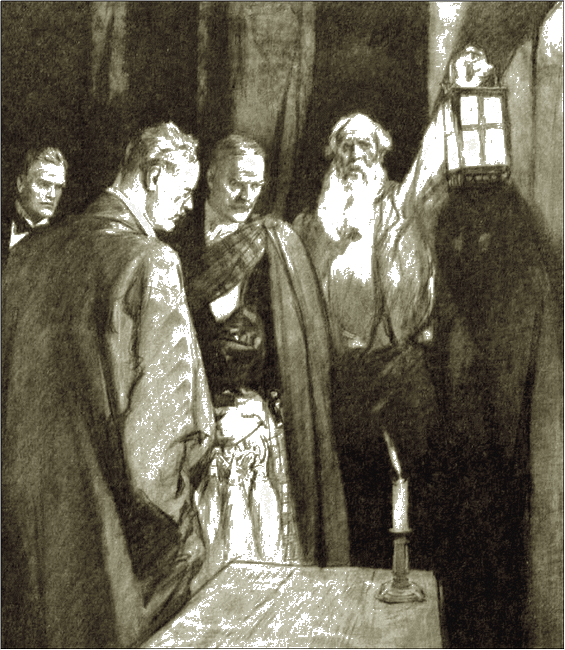

Jamieson's interminable lecture was at length interrupted by Duncan who informed the factor in a hoarse whisper that someone called "auld Jamie" was asking for him. On this the little bailiff bustled away and the laird, recollecting himself as though with an effort, suggested that his guests would like to see the castle before being shown to their rooms. With that he picked up one of the silver candlesticks and led the way out of the door through which they had entered.

In a pitch-black windowless chamber off the lobby he showed them the heavy flagstone, set with a great iron ring, that sealed the mouth of the oubliette or dungeon where the lairds of other days were wont to imprison their private foes. It was a well-like hole in the ground, he explained, sixteen feet deep and excavated out of the solid rock upon which the castle was built.

"But how did the jailers get down to them?" Phyllis demanded.

The laird shook his head. "They didn't!" he said.

"Then how did the prisoners get their food?" the girl asked again.

Toray smiled. "I'm afraid we must infer that any food flung down was merely intended to prolong the prisoner's sufferings. I doubt if any captive of the McReay ever saw the light of day again, once he had disappeared down this hole. For a century or more the place was lost sight of. It was discovered again in my grandfather's time and my grandfather had himself lowered by a rope. It's said that three skeletons were found at the bottom of the pit!"

Mrs. Dean shuddered. "How perfectly ghastly!"

Toray was impassive. "The McReays were always good haters," he remarked in his gentle way.

Returning to the hall, they crossed it and, passing under the gallery, followed a stone passage which brought them to what Toray said was the east wing, added in the eighteenth century. Here in succession they looked in upon a tomblike library, smelling of moldering calf, with tall bookshelves ornamented with busts and a vast and frigid drawing-room, with its statuary and gilt furniture and ottomans a strange jumble of Louis Quinze and Victorian frippery. Beyond the drawing-room a series of closed doors gave on rooms which, the laird said, had been dismantled. But there was little indication, it appeared to Verity, that any part of the wing was in daily use—the corridor struck bitterly cold and the whole place reeked of dry rot. He looked about him for Flora to sound her on the subject, but discovered that she had not accompanied the party.

She was waiting for them, however, in her simple blue frock with her oddly sorrowing eyes, as they emerged from the end of the corridor into a small inner courtyard open to the air. Across the court the lofty mass of the central tower mounted to the lurid evening sky—"Red Calum's Tower," Toray called it, erected as it had been in the sixteenth century by that "bonny fechter," as the laird described his ancestor, renowned harrier of the McNeils, hereditary foes of the McReays, whose ancient Gaelic patronymic of Calum or Malcolm, had descended through a long line of chiefs to the present head of the clan. Verity could not help stealing a glance at their host's tawny coloring—the ruling McReay, it was evident, was another Red Calum.

Flora had slipped off to fetch the key of the tower, a fantastically large key jingling with others on a rusty iron ring. Toray entered first, his candlestick held aloft to light the party up the dark and winding stair. They came to a landing and a door which he unlocked with another key on the same bunch.

Loopholes enlarged to windows, diamond-paned, shed the light of evening upon a bare chamber with a groined roof and oaken chests ranged round the walls. The chests, the laird said, contained the castle archives. He opened one at random and encouraged a somewhat reluctant Phyllis to pick out one of the rolls of sheepskin piled there under a layer of dust and cobwebs. A marriage contract of 1578, between Ian McReay and Margaret Ogilvy, of the house of Airlie, he pronounced, after a glance at the ancient scroll with its great dangling seal and ornate, pointed handwriting.

The tower, he told them, when the parchment had been put back, was no longer used for residence. The chieftain's apartments, he said in answer to a question of Stephen's, were in the keep: the Portcullis Room, which they would see, must be one of the oldest bedrooms in Scotland: generations of chieftains had slept there.

"And do you sleep there yourself, Toray?" Mrs. Dean asked.

The laird shook his head. "No one has slept in the Portcullis Room for many years," he replied. "But, come," he went on briskly, "let me show you the family heirlooms!"

So saying, he led them across to where, on the far side of the room, a glass case stood against the wall. Here they saw hanging upon faded red baize a great, battered cow-horn, set with elaborately embossed silver; a rusty claymore; and, upon a shelf below, various objects such as a large silver bowl, a gold brooch, a pair of old paste shoe-buckles and a knot of black velvet ribbon.

Toray unlocked the case and took down the horn. It was very ancient, he said, while it passed from one hand to the other—the silver was probably old Irish. The legend was that it had been given to Ranald Dhu by an old woman who had appeared to him in a dream, and it was reputed to have rendered the chieftain invulnerable to danger in battle and at the chase.

The legend was that it had been given to Ranald Dhu

by an old woman who had appeared to him in a dream.

The horn restored to its place, the laird showed them the rusty claymore, its blade notched and encrusted with darkly purple stains and told them it had been taken from the cold hand of the chief on the fatal field of Culloden. The silver bowl—a punchbowl—had been given to Ronald McReay, the dead chief's heir, by Charles Edward, by reason of the love he had borne his father; the brooch, the buckles and the hair knot had been worn by Ronald McReay who had lived and died in exile at Saint-Germain.

In a glass-fronted cupboard that flanked the case of heirlooms there were war medals and sundry weapons—the Waterloo medal and sword of Hector McReay, who had been with Pack's Highland Brigade at Waterloo; the sword and medals of the present laird's father who had fought as an ensign of Highlanders at the Alma; Toray's own leather-covered infantry sword and South African war medals from the Boer War—he had been shot through the lungs at Magersfontein with his father's old regiment when Wauchope's Highlanders had been cut up, he explained rather apologetically.

Among the other trophies the cupboard displayed were a khaki infantry cap decorated with a grenade and a very long, old-fashioned bayonet.

Stephen was staring at the cap. "That's a French képi, surely?" he said indicating it with his finger.

Verity, who was glancing idly round the group, found his eyes suddenly arrested by the expression on Flora McReay's face. The blue eyes were bright with a sort of tremulous expectancy—she was staring fixedly at her father.

It was as though a cloud had passed across the laird's thin features. "Yes," he replied impassively. "It was my son's!"

"I didn't realize that your son had served with the French in the war?" Stephen said.

"It was not in the war—for that he wasn't old enough. It was after. Ronald was in the Foreign Legion—he was killed last year in a brush with the tribesmen near Taroudant, in Morocco!"

Stephen had colored up. "I'm terribly sorry, sir. I'm afraid I've stirred up sad memories. I do beg of you to forgive me!"

The laird was unmoved. "There's nothing to forgive, Mr. Garrison. Death in battle is, as it were, a tradition of our family. And the boy died bravely. They found him in a circle of six dead tribesmen, his officer wrote me!" He paused. "But now I must show you to your rooms!" He turned to his daughter. "Will you lock up, Flora?"

He picked up his candlestick where the candles guttered in the draught from the stairs. Kilt swinging and very erect, he led the way from the room.

THE girl, busied with the locking of the cases, did not notice that Stephen had remained behind until she turned and saw him loitering there. At the sight of him, she fell back a pace, her eyes hostile.

"I do hope you'll forgive me, too," he said contritely. "I knew that your brother was dead, of course, but I'd no idea that he was killed with the Foreign Legion képi!"

"Please don't say anything more about it," she told him coldly and moved towards the entrance.

But he barred the way, propping himself against the door and regarding her in the gathering dusk. "I've been thinking over our meeting this afternoon," he said. "What gave you the idea that my name was Berg?"

Her brown cheeks colored. "It was just a mistake," she proffered lamely.

"But you said you'd had a telegram. And my telegram arrived late. Who's this fellow Berg and what did you mean by saying that there's nothing left to plunder here?"

"I prefer not to talk about it!" Her manner was icy.

"It's not mere curiosity on my part. You look perfectly miserable. I was wondering whether there was anything I could do about it!"

Her eyes flashed. "You can take yourself and your friends away from here, Mr. Garrison!"

His eyebrows lifted. "I can hardly do that. Your father has asked us to stay for as long as we like!"

"Is it your intention to buy the castle?" The question was abrupt.

He moved his shoulders. "If I like it, yes. At present, I'm liking it enormously. I think it's the most picturesque old place I ever saw!"

"It's hateful," she broke out suddenly, "you Americans and your money! You think you can buy up everything, don't you?" Her tone was scathing.

He gave her a whimsical glance and, with a vaguely deprecatory gesture, ran his hand over his crisp, dark hair. "Not with the same conviction as formerly," he remarked drily. "You've heard of a thing called the depression, perhaps?"

But she disregarded this mild sarcasm: "Of what good is a place like this to you, falling to pieces and miles from anywhere? Your dollars can give you possession of this tumbledown ruin and a few hundred acres of rock and moor. But they can't buy the spirit of the place. What's Toray without the McReays? You're an intruder—you'll always be an intruder!"

His face was blank as he stood away from the door. "I'm sorry," he said, regarding her intently. "I'd no idea of this!"

"My father kept it from me," she responded in a tone of bitter anger. "He was ashamed to tell me, and no wonder. It was only this afternoon, when he heard you'd arrived, that he confessed the truth. It isn't his idea, I know that; it's that wretched McTaggart in London who forced it on him. If I'd heard about it sooner, you'd have had no invitation to Toray, Mr. Garrison! And I give you fair warning, if I can prevent this sale from going through, I mean to do so!"

But he only smiled imperturbably and said: 'Okay. It makes the position clear, at least. But seeing that, inevitably, I have to spend at least one night under your roof, don't you think we might suspend hostilities in the meantime and meet as friends?"

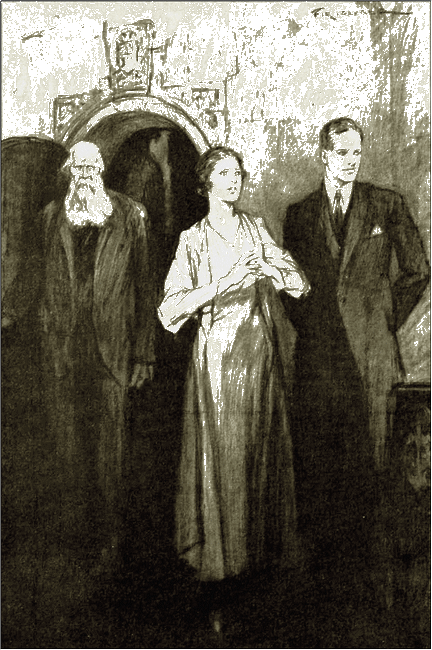

On the sudden she was conscience-stricken. "I was very rude," she avowed in a husky little voice. "I said more than I meant to; I'm sorry. I was forgetting that you're our guest. Please excuse me!" She stepped to the door and Stephen opened it for her.

"Touching this chap Berg," he questioned casually, "does he want to buy the castle, too, or what?"

She stopped abruptly on the threshold, turned. At the look on her face he shed his flippant mood. "I don't know what he wants," she answered in a whisper made tense by fear. "The trouble is that my father seems determined to see him!"

"It's no affair of mine, of course," he broke in. "But if it's a business matter and I or Verity can do anything—Verity's a first-class business man."

Sadly she shook her head. "There's no need to inflict our private troubles upon you," she answered, not without a certain wistfulness. She had raised her face to the light and, as the glory of the sunset bathed the proudly sensitive features, he saw how forlorn, how desperately perplexed, she looked.

"I hate to see people unhappy," he said rather self-consciously. "And you are unhappy, aren't you?" She made no answer. But her lip trembled and a dry sob seemed to shake her. "About this man Berg——" he resumed.

She did not let him finish. "Why should you interfere?" she cried, rounding on him passionately. "What are we to you? Can't you leave us go to ruin in our own way?"

'What are we to you? Can't you leave us to go to ruin in our own way?'

A solemn voice that spoke unexpectedly behind them made them jump. "The laird is asking for you, Miss Flora!"

They whipped around like a pair of conspirators. The major-domo's gaunt frame seemed to fill the doorway. Wrinkled and yellow with age above the patriarchal beard, his countenance was gloomy and charged with suspicion as his glance swung slowly from the girl to her companion. "He's in the Long Gallery!" he told her.

The darkness of the stair engulfed him.

They came to the Long Gallery by way of the grand staircase that mounted to it from the hall. The gallery ran its length above the hall, a ghostly place with its low roof and solemn family portraits and tapers in sconces dimly gleaming on black wainscot. Sundry gaps in the line of ancestors brought to Stephen's mind a chance remark of McTaggart's that the laird had been obliged to part with the best of the Toray pictures.

A door stood ajar and, hearing footsteps, Dwight, Stephen's man, looked out.

"Where's everybody?" Stephen demanded.

"The gentleman took the ladies and Mr. Verity to show them their rooms," the man replied.

With a muttered ejaculation the girl went flying down the stairs again.

"You're in here, Mr. Garrison," Dwight said, "alongside his nibs!"

From the doorway Stephen surveyed the large bedroom, furnished in rather heavy Victorian style, with two spacious windows giving on the loch. "I doubt if your peculiar sense of humor will go over very big up here, Dwight," he remarked crisply. "So have the goodness to refer to our host as "the laird," will you?"

"Very good, Mr. Garrison!" was the imperturbable answer. Dwight was unpacking Stephen's suitcase. "Nice room, sir," he observed, "though I don't know as how I would class the haspect as very cheerful. But there, I was never one for the water meself. You'll wear a black tie tonight, I suppose, sir?"

"I guess so," said Stephen. "What in God's name is that thing behind the screen?"

The servant sighed. He was a tall man, lantern-jawed, with heavily marked, black eyebrows reminiscent of a vaudeville comedian and a shining bald pate. "You may well harsk, sir. I ain't seen one of them since I was first in service. That's an 'ip-bath, that is. I hadn't hardly set foot in the castle afore I passed the remark to Marie, "Marie," I sez, "if there's a bathroom in the place," I sez, "then I'm Robert the Bruce and you're Mary Queen of Scots!"

A voice from the doorway interrupted further sprightly reflections. "I hope you've got everything you want, Mr. Garrison!"

The laird was there with Verity, who looked slightly fussed. "I'm afraid the accommodation's rather primitive," said their host, "but we don't keep up the state we used to at Toray. In fact, with so many of the bedrooms dismantled, we're somewhat cramped for space, particularly as I have other guests arriving tomorrow."

"Other guests?" Stephen echoed in surprise.

The laird veiled his eyes. "Friends of my son." He paused. "Mr. Verity," he went on, "would have liked to be nearer to you—he says you have a lot of work to get through together. He's in the east wing with the Deans—rather a long way off, I'm afraid, but it couldn't be helped! This room and mine are the only bedrooms in this part of the castle!"

Verity had grown rather red. "I only thought, if I had a room somewhere handy, I could pop in at odd times," he explained, "after the others have gone to bed or before you get up in the morning, and have a go at those accounts. You've sidestepped all work on the trip so far and the Manchester office is howling for them!"

Stephen gave him a withering glance. "Obviously, the best room for you is the dungeon with the flagstone rammed down tight! And to think I took you along as an agreeable holiday companion!"

The laird, who had been glancing round the room now approached. "I was going to show you the Portcullis Room, wasn't I?" he said. "And then it will be time to dress. Here are the ladies now! I wanted them to see it!"

Mrs. Dean with Phyllis and Flora appearing at this moment from the staircase, the whole party followed the laird, who bore a lighted candle, to the end of the gallery where a shallow flight descended to a paneled door. "It's called the Portcullis Room," he explained as they went down the stairs, "because it's immediately over the seagate where the portcullis used to be!"

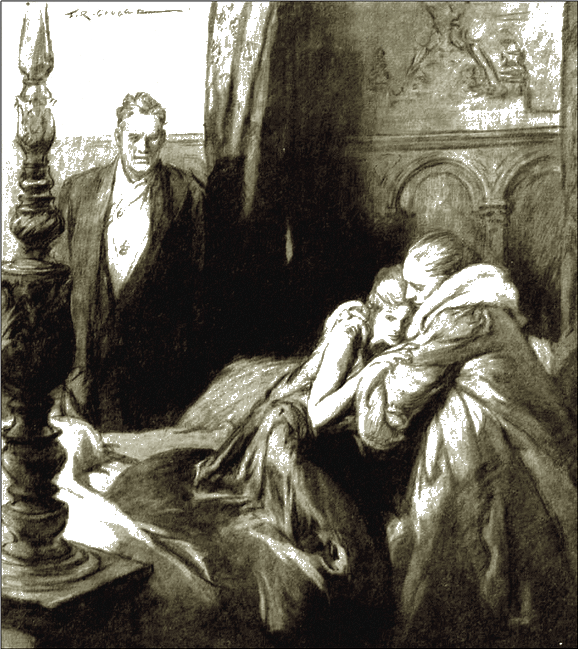

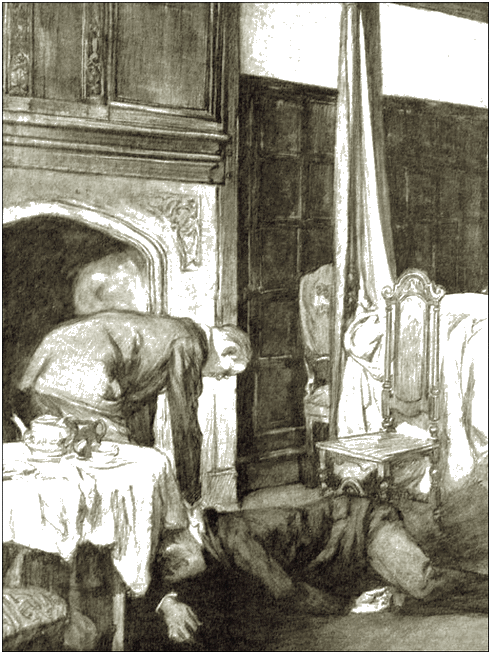

A key was in the door. He turned it, and the door opening, revealed a couple of steps leading down. The boom of the sea and the howling of the wind drifted across the threshold as they descended. Toray's candles flung a sickly light upon the great state bed which, high and pompous as a catafalque, reared its four posts and canopy from a platform set against the wall with steps leading up.

A single window, sunk in the enormously thick masonry and heavily barred with iron, commanded the dark prospect of the loch. The ceiling was low and in the yellow candlelight the figures of the party sent huge shadows dancing athwart a variety of grotesques molded, in the Tudor manner, in the plaster—grimacing heads, weird birds and beasts. Faded blue tapestry hangings, matching the looped-up curtains of the bed, clothed the walls, disclosing through sundry rents paneling as glossy black as the rough-hewn beams of the floor. Such furniture as there was was on the grandiose scale an enormous oak press; a Florentine chest; some pompous Spanish chairs in tooled leather—and before the empty stone fireplace a very decrepit-looking leather armchair and a worm-eaten oak table.

Upon this table the laird set down his candlestick, then faced his guests. "On the feast of Michaelmas in the year 1739," said he, "this room was the scene of one of the blackest deeds in the history of my family. On that day Hugh McNeil, from one of the adjacent islands, was wrecked in a great storm on the coast of Toray and sought refuge at the castle. According to the best traditions of Highland hospitality, notwithstanding the fact that for centuries a deadly feud had existed between our family and the McNeils, the laird gave him his own room, this very room in which you find yourselves. When day came, however, the guest was discovered lying dead there"—he turned and pointed to the floor in front of the fireplace—"with his own dirk driven into his back!"

Stephen pursed up his lips in a silent whistle.

"You were certainly right when you said that the McReays were good haters, Toray!"

"On the discovery of the body," Toray replied gravely, "the laird of those days, my ancestor, Ian McReay, drowned himself in the loch. The assumption is that, in the face of such treachery, he felt he could no longer hold up his head among his fellow clansmen!"

"Then who was the murderer?" Mrs. Dean demanded.

Toray shrugged his shoulders. "His identity was never established—the islanders believe it was some retainer of the McReay whom Hugh McNeil had wronged."

Now Verity intervened. "Mr. McTaggart spoke of some family secret in connection with one of the rooms in the castle—a secret that's handed down from father to son. Is this the room, by any chance?"

The laird nodded composedly. "It is. . ." Then, as though to change the subject, he turned to Mrs. Dean and said, "If you look at the floor before the fireplace you will see a dark stain there—it's said to be the mark of Hugh McNeil's blood!"

They crowded round the fireplace and scrutinized the shadowy patch that seemed to darken the glossy surface of the planking. No one spoke and in the impressive rush they could hear the wind shrieking in the chimney and, like a bass accompaniment, the deep bourdon of the waves. Phyllis Dean was the first to draw away.

"This house scares me," she said in an undertone to Stephen. "You should see our room, like a vault, in a long corridor of empty rooms. I shall never dare to go up there by myself after dark, I know I shan't. And there's no bath, and the old woman who waits on us can scarcely speak English and—— Oh, Steve, don't let's stay long! Let's beat it at once—tomorrow!"

He had taken her dainty hand in his and was fondling it, gazing down at the blood-red nails. "Why, honey," he said caressingly, "you ain't seen nothin' yet! Wait until tomorrow morning when the sun shines and we can get out on the moors and you'll realize what a glorious old place it is!"

"'Old' is the word!" she retorted crisply. "And I guess that goes for the plumbing, too. This house'd give Ed Wynn the willies. You can have Toray, Steve! The way I'm feeling right now, I don't care if I never see the damned place again! I may be unromantic, but there it is!"

Glancing up, Stephen found Flora McReay's grave eyes upon them. Rather sheepishly, he relinquished Phyllis's hand. "Oh, come, sweetheart," he encouraged her, "it's not so bad as that, surely. You're cold and tired and it's all a bit strange at first. But wait until you've had a cocktail and a good dinner and you'll feel like a million dollars!" He gave her his cheerful smile.

"Only a dose of poison would make me feel right in this old barn," she rejoined disconsolately. But she returned his smile and, tucking her arm in his, he led her out in the wake of the others.

DINNER that night was a gloomy affair—until Rory's appearance, that is. There were no cocktails, only sherry served on a table before the fire in the great hall where they dined, and the fare was indifferent—a thin barley broth, some boiled fish and a leg of stringy mountain mutton. The factor and his wife, a thin woman overcome with shyness, were invited and little Jamieson tried valiantly to keep the conversation going.

He did not receive much help from the laird and Flora. In honor of his guests Toray had donned Highland full dress and a magnificent figure he presented in the short Highland jacket of black velvet with jabot and ruffles of old lace and a kilt which, mainly scarlet and white, was much more showy than the kilt he had worn that afternoon—it was the McReay dress-tartan, he explained to Mrs. Dean. He had a grand sporran—white goat's hair and stockings lozenged in red leather bound in silver—and white, with the jeweled head of a dagger flashing in the right leg, and buckle shoes. As he sat behind the candelabra at the head of the long table he looked like some ancestor descended from one of the portraits in the Long Gallery.

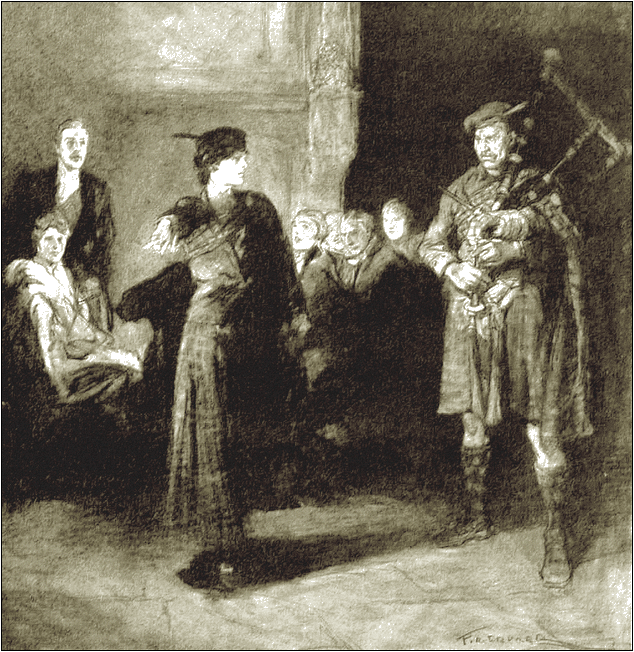

Toward the end of dinner they heard the skirl of pipes outside and from under the gallery a rosy-checked old man, in bonnet, plaid, and kilt, appeared, blowing lustily upon his bagpipes. Three times, in a solemn silence, with kilt tossing, the piper marched round the room while the rafters echoed to the stirring music, then he disappeared under the gallery and the strains abruptly ceased.

"It's just a custom in the Highlands," Toray said with his apologetic air to Mrs. Dean who was on his right. "You may have heard of it?"

"Indeed I have!" Mrs. Dean cried enthusiastically. "But this is the first time I've seen it. Does the piper play for you every night?"

"Oh, yes. Old Rory's the house piper. He and his forbears have been hereditary pipers of the McReays for more than a hundred years. Old Rory's quite a figure in the pipe world. He was taught to play by his father who was a pupil of the celebrated Donald Ruadh McCrimmon, the last of the hereditary pipers of the McLeods, who have Castle Dunvegan in Skye. You've heard of the famous piping school of the McCrimmons at Borreraig, of course?"

"I—I believe so," Mrs. Dean said vaguely.

"Ah," the laird remarked, "they took their piping seriously in those days. The course lasted seven years." And he began to discourse learnedly of the so-called "ceol mhor" or "big music," with its "laments" and "salutes" and "war songs," much superior, he added with a sigh, to the present decadent era of piping which knew little else save marches and strathspeys and reels—"tinker's music," as old Rory called it. Verity, who was listening from the other side of the table, was interested to note that once again it was the past that came to the laird's aid to rouse him from his morose and brooding taciturnity. He could play the pipes a bit himself, he told Mrs. Dean, but only as an amateur, a dilettante, and so could Flora. But Flora's forte was dancing—maybe Mrs. Dean could persuade her after dinner to show them a fling or two. He was still talking eagerly when old Duncan gravely plodded up to the table, bearing in his hand a salver on which stood a decanter of whisky and a small tumbler.

He spoke a phrase in Gaelic to Toray, who bowed ceremoniously, upon which the piper was again introduced. He in turn marched up to the table and waited, his hale and ruddy cheeks glistening in the candlelight, while Toray filled the tumbler to the brim with whisky and handed it to the piper. The old man seized the glass and, with head erect and eyes to his front, cried a toast in Gaelic, drained the glass at a gulp, set it down, and, laying his hand to his bonnet, marched out again.

Dinner over, they moved across to the big fireplace and had their port and coffee in a circle about the blazing peat fire. The talk turned to piping again and the laird suggested that they might be interested to hear different examples of pipe music. "And I think, Flora, my dear," he said to his daughter, "that our friends here would like to see a real Highland dance!"

"Would you mind frightfully?" Mrs. Dean cried rhapsodically to Flora. "We'd simply love to see you dance!" The others echoed her with enthusiasm.

The girl smiled in her grave way. "I haven't danced for a long time, I'm afraid," she said, "but I'll do what I can. I'll need to change my dress, though!"

"Do that," her father bade her. "And tell Duncan to send Rory in with his pipes!"