RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Illustrated London News, Xmas 1923, with "Circumstantial Evidence"

Mystery and Detection, September 1935, with "Circumstantial Evidence"

The Knife Behind the Curtain,

Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston & New York, 1930

R. ALBERT EDWARD BIRKINSHAW, a rather prim figure in his alpaca coat, black tie, and well-worn dark-grey trousers, handed the card back to the office-boy.

"Mr. Salsbrigg is engaged," he said. "Anyway, he doesn't see people except by appointment; you know that as well as I do, Percy. Tell him to write in."

"'Sjes' wot I told 'im, Mr. Birkinshaw, but 'e sez: 'You tell the boss it's Mr. Claud Merritone,' 'e sez, 'an' 'e'll see me quick enough,' 'e sez."

"I can't help what he says, Percy," rejoined Mr. Birkinshaw, in the mild tone that was familiar to him. "A rule is a rule. He'll have to write for an appointment!"

"Guv'nor busy?" said a voice.

Mr. Birkinshaw looked up from the high desk which, during the working days of sixteen years, he had occupied in the clerks' office at Mr. Salsbrigg's. Mr. Salsbrigg liked to call it the clerks' office, though, in reality, it was the principal of the three rooms which Mr. Salsbrigg rented in Casino House, E.C.2, for his many enterprises.

A tall man, wearing a waisted overcoat, white doeskin gloves, and a top-hat that shone with some extraneous lubricant rather than its own innate effulgence, stood in the doorway. He had a sallow face, a small black moustache, and a pair of dark and restless eyes.

"Mr. Salsbrigg is engaged," said the clerk severely.

"Mr. Salsbrigg is engaged," said the clerk severely.

"Righto!" remarked the stranger easily, "I'll wait!"

And he dropped into the chair at the typewriter which Miss Ruby Pattinson, the typist—"my secretary," Mr. Salsbrigg was fond of calling her—had vacated for the purpose of clearing away the office tea.

"It's no good waiting," said Mr. Birkinshaw, peering at the stranger over his pince-nez. "Mr. Salsbrigg won't see you without you have an appointment. That's an inflexible rule, and..."

But voices resounded from the other side of the door in the glass partition separating the clerks' room from Mr. Salsbrigg's sanctum.

"I'll let you out by my private door into the corridor, Mr. Goldstein!"

"That's all right. I put me 'at down in the outer office, thank yer."

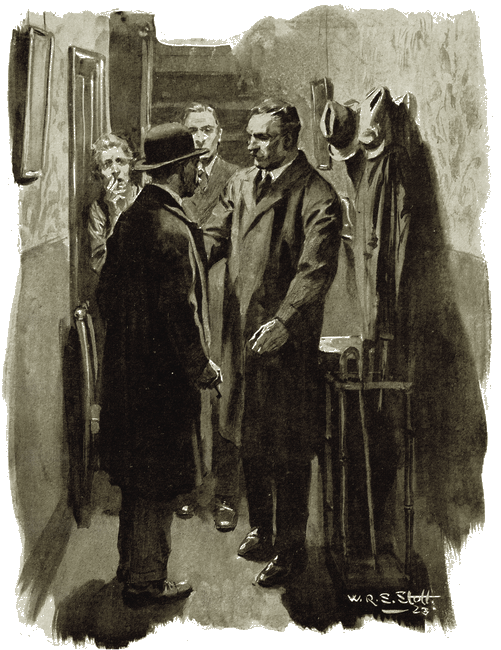

Mr. Goldstein appeared at the door, as black and sleek and squat as the other, who was ushering him out, was rubicund and fat and burly.

"Good-day to you," said Salsbrigg, in velvety, throaty tones, "and glad I am that everything is satisfactorily settled. It has been a pleasure to do business with you, Mr. Goldstein."

"Good-day to you... It has been a pleasure to do business with you, Mr. Goldstein."

The Jew wagged his head humorously as he buttoned up his overcoat.

"A terrible hard man, you are," he sighed. "We're all mugs when we're up against a tough proposition like you, Salsbrigg!"

Mr. Salsbrigg's florid face was wreathed in a gratified smile that sent the wrinkles sagging across the features from the narrow blue eyes down to the receding chin that sloped into the folds of the pink throat.

"Very good, ha-ha! Oh, very good!" he exclaimed, rubbing his hands. "You're a deep one, Goldstein. I'd have to get up very early in the morning to make money out of a hot case like you. Good-evening, friend Goldstein, good-evening! Going to be wet again, I fear! Percy, Mr. Goldstein's hat!"

All smiles, he waved a fat hand as the Jew stumped his way across the office. But when the plump bowed back had disappeared, the friendliness fled from the pink face.

"Mr. Birkinshaw, I want you," Mr. Salsbrigg snapped, and went back into his room. As the clerk, blinking mildly, followed him across the threshold, the tornado struck him full.

"Are you mad, Mr. Birkinshaw?" shouted the throaty voice, now grown fiercely irate. "Have you taken to drink? Miss Pattinson says you're the dam' fool that gave Goldstein an appointment after banking hours. You know he's the crookedest little reptile in the trade: you know that I take nothing but hard cash from the likes of him; and yet, just because I'm up in Manchester, you let him come here and saddle me with a matter of eighteen hundred pound and the bank shut. Don't you answer me back, Mr. Birkinshaw! I've only got to go out on Finsbury Pavement and whistle on my fingers, and I can get twenty, two hundred clerks as good as you. As good? By God, a dam' sight better! Here I sit sweating my guts out day after day, trying to make both ends meet, with trade as flat as flat, and the City that rotten you couldn't float a cork, and there's not a man in the office I can depend on! Has it occurred to you, may I know, that there will be a matter of eighteen hundred pound in that safe from now until to-morrow morning?

"I'm shore I'm very sorry, Mr. Salsbrigg," faltered the clerk, "but I didn't realise that Mr. Goldstein would settle in cash..."

"Didn't realise? My God!" A fist crashed heavily down on the desk, "you're no more use than a sick headache!

"What a noise you're making, Alfred!"

The pale face of the stranger suddenly appeared round the glass door. As abruptly as it had broken out, the tornado ceased to rage. A rather stiff smile brightened Mr. Salsbrigg's red face.

"Come in, Claud," he said feebly, and, addressing the clerk, he added: "You want to smarten yourself up, Mr. Birkinshaw; dull, that's what you are—and half asleep!"

The door shut with a bang, and Mr. Birkinshaw returned to his desk, his head in a whirl. Inwardly he reproached himself bitterly. Why did he a always let old Salsbrigg take him unawares? Why did those calm, unanswerable retorts to his employer's insulting gibes only occur to him after the storm was past and Salsbrigg, having vented his ill-humour on his three-pound-ten a week employee, had returned to his wonted air of Olympic condescension in his treatment of him?

"Old man got his rag out again?" said Cradock, the other clerk, who was brushing his long fair hair before the office glass.

"Yes," said Birkinshaw. "It's more than flesh and blood will stand, Crad, as some day he'll find out, the—the devil!"

"My word, Mr. Birkinshaw," said Miss Pattinson, a chemical blonde with bobbed hair and skirt, "what lengwidge!"

"Humph!" grunted the clerk. "How'd you like to be talked to the way he talks to me? Swearing—and that. But I'll get even with the old beast. You see if I don't!"

"Good gracious!" exclaimed Miss Pattinson. "How fierce you are! I declare you quayte fraighten me, Mr. Birkinshaw!"

"Keep your hair on, Birkie," said Cradock. "Percy, you young devil, what have you done with my soap? Birkie..."

"What is it?" said the clerk, busy with his papers once more.

"I've got a couple of seats for the Coliseum. I was going to take Cissie—you know, the girl I told you about—but the dirty dog 'phoned me up just now to say she can't come. You care to come along?"

"Sorry, old man," mumbled Birkinshaw, his head in his desk, "'fraid it's quite impossible!"

"Working late here again, are you?"

There was a slight pause. Cradock repeated his question. "You staying on, old man?"

"Ye-es. There are those papers for the Patent Office to finish. I—I believe I'll stick on a bit and polish 'em off."

"But you can do 'em to-morrow night just as well. And there's a ripping good bill at the Coliseum."

"Thanks awfully, old man, but I don't think I'll go with you this evening. There's the half-yearly statement coming on, y'know, and I want to get clear for it in good time."

He paused and fell to wiping his glasses. Then shyly:

"It's—it's dam' kind of you to ask me, Crad."

"That's all ri', Birkie. Only it's a pity to waste the other ticket. I'll have to try some of the people at my boarding-house, though they're a dull lot, the Lord knows!"

The door in the glass partition opened again, and Mr. Merritone reappeared. The door closed rather forcibly behind him.

"Whatever have you bin an' done to our Alfred?" remarked the stranger affably to Mr. Birkinshaw. "He is in a sweet temper this evening, I don't think!"

Mr. Birkinshaw glared indignantly at the intruder, who, quite unperturbed, kissed a white-gloved hand gracefully to Miss Pattinson and vanished into the outer office where Percy was stamping the letters for the post.

The intruder kissed a white-gloved hand gracefully to Miss Pattinson

"He's got a nerve!" said Miss Pattinson, voicing so effectually the general feeling of the clerks' room that neither Birkinshaw nor Cradock felt impelled to add their own comments. The light in Mr. Salsbrigg's office went out abruptly, and a door slammed.

Mr. Cradock, who, in his grass-green overcoat, was practising golf-shots with his walking-stick, looked up.

"Old man's leaving early," he observed. He glanced out of the window. "Hell! It's going to rain. You'll want the Dreadnought going home to-night, old man!"

He jerked his head in the direction of the hat-stand, where Birkinshaw's umbrella, inexhaustible fount of office witticism, stood in its appointed place. It derived its nickname from its crutch handle of solid ash, a regular club of a handle, as thick as two fingers round. Birkinshaw, who had all the Englishman's love of solid belongings, had bought it at a sale. Three days a week, on the average, it accompanied him to the office.

"Nothing like a good umbrella in this filthy climate!" he remarked stolidly, an observation, like the jest, of the sealed pattern variety.

"Umbrella? I should call it a niblick or a baffy myself!" rejoined Cradock, who contrived to play golf on his infinitesimal income. "Well, I must be toddling. Good ni', old man!"

"Good ni', Crad."

Miss Pattinson had already sailed Tubewards on a cloud of patchouli, and after Cradock, presently Percy, three instalments of "Deadwood Dick," buttoned up beneath his shabby jacket, clattered noisily off to the lift, making the welkin ring with the syncopated protest of the New York fruit-seller. And Birkinshaw was left alone in the office, the green-shaded lamp pulled down low over his desk the only light in the big room.

He sighed and ran his fingers over his thinning sandy hair. It was close on six o'clock, and the voice of the City droned on a deeper note as thousands of tired workers flocked towards their homes in the suburbs. The clerk got out his papers and settled himself down to work. He liked the quiet of the office after the others had gone home. He could concentrate better without Salsbrigg's strident nagging and Cradock's robust breeziness, and Miss Pattinson's indefatigable parade of her feminine arts. In the reposeful, spacious room, with London's lurid night-sky framed in the uncurtained window, he could indulge in those dreams that come even to a city clerk at three-pound-ten a week, more freely than in his cheerless bed-sitting-room in the Fulham Road.

And he could smoke, content in the knowledge that Mr. Salsbrigg's ban against smoking in office hours expired with the termination of the working day at half-past five. From a battered leather cigarette-case he drew one of his famous Bolivian cigarettes, another office joke—unappetising-looking smokes of coarse black tobacco, with frayed ends protruding from the thin-grained paper stamped with an eagle in blue. Eager for experiment as he always was, he had picked out a packet in a vague tobacconist's near the office, allured by its proud boast: "Pure as the Pampas Air; Grateful to the Palate; Caressing to the Throat." Though secretly he preferred Gold Flake, he had gallantly stuck to his Bolivians. "An acquired taste, old man," he used to tell Cradock; "a bit pungent at first, but pure; at any rate, a fellow knows what he's smoking!"

As he slipped his cigarette-case back into his pocket, his fingers touched something, and he withdrew a letter sealed and stamped ready for the post. He laid down his cigarette unlit upon the desk and smote his brow. Then, with a hasty glance at the clock, he paused for an instant irresolute, gazing at the papers spread out before him, and presently, with a sudden gesture, began to shovel them together.

Outside in the street the shrill note of a fire-gong rang out suddenly above the dull diapason of the traffic, a fierce, noisy clanging accompanied by the thunder of wheels. Again and again the engines swept by with furious gonging and a headlong rush that made the building tremble. Birkinshaw acted very swiftly. He swept all his papers back into his desk, locked it, changed his office-coat for the jacket of his well-worn suit, grabbed his hat and overcoat, and darted for the door of the outer office, that clicked behind him with a spring-lock. He did not wait for the lift, but descended by the staircase to the ground-floor lobby with its huge shields of the tenants' names. As he reached the swing-doors another fire-engine flashed past. The night porter's box was empty. The sight of passers-by hurrying along the street in the direction taken by the engines told him where the porter had gone.

But Birkinshaw did not bend his steps in the direction of the fire. He hastened to the bloated scarlet pillar-box at the opposite corner of Finsbury Pavement. There he consulted the plate on the front setting out the times of collection, and finally, without posting his letter, turned away and boarded a 'bus going west. He travelled as far as the General Post Office, where he consigned his envelope to one of the huge maws under the pillared portico, and then, after a moment's hesitation, went out into Newgate Street and smartly hopped on a westward-bound bus.

He took a ticket to Piccadilly, and, alighting at the foot of Bond Street, strolled along towards the Park, a look of happy contentment on his face, gazing at the brightly illuminated shop-fronts or, as they halted in the press of traffic, peering in at the windows of the glittering limousines bearing elegant, well-fed folk to the restaurants.

At the corner of Dover Street an idea seemed to strike him. He stopped and looked about him, then addressed a passing District Messenger boy.

"Where's the nearest telegraph-office, sonny?"

"Up Dover Street 'ere on the left," piped the urchin. "But you'll want to be nippy, mate. They closes at seven!"

By the clock above Hatchett's it was five minutes to seven. Birkinshaw hurried up Dover Street and reached the office in time to scribble a telegram under the severe and disapproving gaze of the damsel behind the wire screen, who, dressed for the street, was watching the clock with ill-concealed impatience. As he emerged from the post-office a few drops of rain pattered briskly on his face. He stopped and smote the palm of his hand with his fist. "Well, I'm jiggered!" he said, addressing the night. Then he shrugged his shoulders, and set off slowly towards Piccadilly again.

When, at a quarter of an hour before midnight, he opened with his latch-key the front door of the house where he lodged in the Fulham Road, two dim figures rose up from chairs in the hall to greet him. In the background bobbed the pale and anxious face of his landlady.

Two dim figures rose up from chairs in the hall to greet him.

In the background bobbed the pale and anxious face of his

landlady.

"Are you Albert Edward Birkinshaw?" asked one of the two strangers. On the clerk's affirmative reply, the man informed him that he would be arrested for the murder of Alfred Salsbrigg.

WITHOUT leaving the box the Coroner's jury returned a verdict of wilful murder against Albert Edward Birkinshaw. The prisoner reserved his defence, but the statement which he made voluntarily to the police, read out in court, did little or nothing to rebut the overwhelming volume of evidence against him.

Detective-Inspector Coleburn of the City Police, who had arrested the prisoner, gave the substance of the case against him. Shortly after seven o'clock on the evening of the murder, Bertram Batts, night porter at Casino House, when engaged in his duties on the third floor of the building, heard the telephone ringing in Mr. Salsbrigg's office. There was a light visible through the glass door, but as no one answered the telephone, thinking that Mr. Salsbrigg had gone away and forgotten to turn off the light, Batts opened the door of Mr. Salsbrigg's room with his pass-key and found Mr. Salsbrigg dead in his chair.

The officer submitted a plan of the office—a long narrow room, showing that Mr. Salsbrigg's seat at the desk was placed so that it faced the window and had its back to the door. Mr. Salsbrigg lay prone across the desk with arms hanging down, the top of his head practically smashed in by two, or possibly three, blows from some blunt instrument which the medical evidence would show beyond doubt was the crutch-handled umbrella found lying on the floor beside the desk. This umbrella the prisoner admitted to be his.

A murmur ran round the court as the Inspector held up the Dreadnought. The ribs had torn jagged holes in the cover, for the solid ash stick that ran through it from the handle had snapped with the force of those terrible blows, and the whole frame had collapsed. The handle itself was thickly encrusted with matted blood and hair.

"Robbery was evidently the motive of the crime," the Inspector went on, "robbery, and perhaps revenge as well. The pockets of the deceased had been ransacked for his bunch of keys, which was found hanging in the lock of the safe in the wall beside the dead body. In that safe the sum of eighteen hundred pounds in Bank of England notes was deposited on the afternoon of the crime. When the body was found the safe stood open and the money had disappeared.

"I shall call evidence to show that the prisoner was aware that this money was in the safe, that ill-will existed between him and his employer, and that, only a few hours before the murder, he had uttered threats against the deceased. Witnesses will depose that the accused man was alone in the office, all the other employees having gone home, when, about an hour before the crime, Mr. Salsbrigg returned. Finally, still smouldering in the ash-tray on the desk of the deceased, was found one of the prisoner's cigarettes, a brand of Bolivian cigarettes peculiar to him, which, taken with the circumstances that the body was yet quite warm, shows that the crime was committed—and this is supported by the medical evidence—not more than ten minutes before the discovery of the body."

The first witness was Bertram Batts, night porter at Casino House. On the evening of the murder he came on duty at 6 p.m. By that hour most of the offices would be closed. About five minutes past six, Mr. Salsbrigg came in, and Batts took him up in the lift, as the lift-man went off duty at six. He confirmed in more detail the Inspector's account of the finding of the body. In reply to a question by the Coroner he said he heard no sounds of any struggle, as he must have been on the second floor, the floor below, when the crime was actually committed, collecting the rubbish. From the second floor he mounted by the stairs to the third and, hearing the telephone ringing repeatedly in Mr. Salsbrigg's office, went straight there.

"Did you answer the telephone?" asked the Coroner.

"Yes, Sir. It was Mr. Cradock, one of the clurks, asking for Mr. Birkinshaw."

Cross-examined by Mr. Harley Brewster, representing the accused, the witness gave the hour of his finding the body as ten minutes past seven. He had remembered that this might be an important detail, and had looked at the clock in Mr. Salsbrigg's room as he rang up the police. In reply to a further question he stated that after he had taken Mr. Salsbrigg up in the lift, he returned to his box and remained there till 7 p.m., when, as usual, he went to the upper storeys to clear away the litter.

"Then you were not absent from your post for a second after you returned from the lift?"

"No, sir!"

"Then if Birkinshaw left the building between the hours of six and seven you must have seen him?" "Yes, sir."

"Then we may take it that no one entered or left the building between Mr. Salsbrigg's arrival and seven o'clock?"

"Yes "—defiantly.

"You are prepared to swear to that; you're on your oath, remember!"

The man hesitated, and eventually mumbled something about he "might have popped out to get a mouthful of fresh air."

"You didn't go and see the fire in London Wall by any chance, did you?"

The question took the porter off his guard. Rather abashed he admitted that he did "pop round the corner for a minute or two." With a significant look at the Coroner, Harley Brewster left it at that and sat down.

Followed the medical evidence, very gruesome, with much pawing of the blood-soaked umbrella, and holding up of ghastly exhibits in jars. Then Cradock, pale and reluctant, told how at five minutes past seven he had telephoned the office to try and persuade Birkinshaw to change his mind and accompany him to the theatre; and how, after a long interval, the night-porter had answered the telephone. Under severe questioning by the Coroner he had to admit that Birkinshaw knew that the money was to be locked in the safe for the night, and that the accused had appeared to resent greatly the "ticking-off" he had received from Mr. Salsbrigg.

"Did the prisoner in your hearing threaten the deceased?" the Coroner asked.

"Not exactly threaten. He said he was fed-up, or words to that effect."

"Nothing more than that?"

Cradock flicked a quick, despairing glance at the table where his friend, blinking, bewildered, insignificant, sat between two uniformed constables.

"He said it was more than he could stand, as Salsbrigg would find out."

"What do you suppose he meant by that?" asked Harley Brewster, rising to cross-examine.

"No, no, Mr. Brewster," the Coroner expostulated; and Miss Ruby Pattinson was called. A less unwilling witness was the typist, in deep and fashionable mourning; "a pretty, girlish figure" one of the newspapers called her, with (inset) "Ruby Pattinson Leaving the Court."

She was not hostile to the accused, but she was more concerned with the impression she was producing upon the crowded court than with the exact effect of her deposition. When, after stating that she could not "quayte" recall the exact words used by the prisoner, but he had said he would "do the old devil in," or something like that, for which she had felt impelled to reprove him, she stood down, it was apparent that her evidence had considerably strengthened the case against the prisoner.

"Call Mr. Claud Merritone," ordered the Coroner, and Salsbrigg's affable caller was sworn. His manner was an admirable blend of deference for the court, sorrow for his dead friend, and sympathy with the accused. Mr. Salsbrigg, he was bound to admit, had spoken harshly to the prisoner. He had gone so far as to describe him to the witness as a something fool—he would leave the adjective to the imagination of the court (laughter). He had known Alf Salsbrigg for the matter of a dozen years; he was one of the very best; a thorough good fellow, without an enemy in the world. He had left him about half-past five busy at his desk, and Salsbrigg had said nothing to him then about leaving or returning later to the office. Yes, he had been a witness of the scene between the deceased and the prisoner, and thought, if he might say so with all respect for the dead, that Salsbrigg's tone had been very provoking. Mr. Brewster had no questions to ask, and Mr. Merritone, nursing his oleaginous topper in his white-gloved hands, stood down.

Detective-Inspector Coleburn was recalled by the Coroner to speak as to the cigarette. The Inspector's theory was that the deceased, and not the murderer, had been smoking it, for he had detected particles of the coarse black tobacco of which the cigarette was made upon the dead man's lower lip. A leather case filled with these same cigarettes was found in the possession of the accused, and figured with the other exhibits.

The Coroner then read the prisoner's statement voluntarily made at Cloak Lane Police Station, after he had received the customary warning. According to this he had left the office shortly after six and passed unnoticed out of the building, the night-porter being absent from his box. He had taken a bus to Piccadilly, alighted at the foot of Bond Street, and thereafter walked about the West End. Being a vegetarian, he had dined off some apples and bananas, which he had bought at a stall in the street market off Shaftesbury Avenue. Mr Salsbrigg had not returned to the office when he left it. He had intended, as he told Cradock, to stay on late and work; but he found he was unsettled and so had changed his plans and gone for a walk up West instead. About ten minutes past eleven he took the Hammersmith Tube from Piccadilly to Baron's Court, and reached his rooms in the Fulham Road shortly before midnight, when he was arrested. He protested he knew nothing whatsoever of the murder.

When the reading of the statement was finished, the prisoner asked if he might be allowed to speak. The Coroner told him he would be better advised to reserve his defence.

"I only wanted to say this," said Mr Birkinshaw, "and that is I forgot my umbrella when I left the office that evening. As for the cigarette, I remember leaving one out on my desk. I took it from my case intending to light it, and forgot it. I can only suppose that Mr. Salsbrigg found it when he came back and smoked it."

"Is that all?" asked the Coroner bluntly. "Very good." He turned to the jury, "Now, gentlemen...."

"Well," said young Cradock to Harley Brewster as they left the court together. "What do you think?"

"Think?" replied the solicitor disgustedly. "I think that in the whole of my professional career I never saw a man more completely enmeshed in the toils of circumstantial evidence than your pal Birkinshaw. He don't want a lawyer to save his neck; he needs a wonder-worker, by Gad!"

ON a soft December morning, with a smooth sea gently lapping the shore below and the bells of St. Peter's calling to church from the cliffs above, Harley Brewster and young Cradock sat on the jetty at Broadstairs and discussed the case.

"Nothing but a good strong alibi will save him," the lawyer announced. "One creditable witness who will depose that at the hour of seven p.m. on that evening your little pal was anywhere but at Casino House will do the trick. But Birkinshaw can produce nothing. He's scarcely able to remember where he wandered during all those hours on the night of the murder. He says nothing but 'It's hopeless! I'm trapped!' Even that fruit he got don't give us an alibi, for, on his own showing, he didn't buy it till nine o'clock or thereabouts, two hours or so after the murder."

"I believe you think he's guilty," said Cradock bitterly.

Brewster shrugged his shoulders.

"I'm sure he's keeping something back. And, as between solicitor and client, that don't go, young man!"

"Look here," said Cradock, "just suppose we're outsiders and know nothing about him. How do the facts strike us? Here's old Birkie, according to the police account, determined to kill Salsbrigg and get away with the boodle. In the first place, we must wash out premeditation, for not only did he kill him with his umbrella, which all of us know, but he goes and leaves it on the scene of the crime. We'll call it a sudden impulse, then. Right! Well, having brained old S., Birkie thinks he'll grab the oof. Now listen to me! Every one of us in the office knows that old Salsbrigg kept his bunch of keys on a steel chain running from the back of his braces to his left-hand trousers pocket. Whoever killed old S. didn't know that, for his pockets were ransacked. The two lower pockets of his waistcoat were turned inside out, and his watch was dangling down from its chain when they found him."

"By George!" commented Brewster, taking his pipe out of his mouth and sitting up. "Go on, young fellow! You're beginning to interest me."

"Another point. Birkie and I both know the key of the safe. Salsbrigg has given it to us scores of times when he's been away. Do you realise that the man who killed Salsbrigg didn't know which was the key of the safe?"

"On what did you base that?" said Brewster sternly.

"The paint, man, the paint! The green paint round the lock shows one scratch, and on the bronze of the lock itself there are other little scratches showing where he must have tried key after key before he hit on the right one."

"Are you sure of this?"

"I spent half an hour last night on the lock with a reading- glass."

"Go on!" said Brewster grimly.

"You've seen the mess that old Birkie's gamp is in. Isn't it rather strange that there was no blood on Birkie's clothes? I don't know anything about these things, but I've always heard that blood is rather hard to wash off. And where can a man, wandering about London at night, wash his clothes clean?"

"He might have gone to a friend's house," the lawyer put in.

"I'll grant you that, though I don't believe Birkie has a single friend in London apart from me. But there's this further point. You made that lying porter admit that he did not see Birkie go out, didn't you?"

"By implication, yes."

"Then,"—triumphantly—"if he didn't see Birkie go out, why shouldn't the murderer have come in and out again unobserved? How about that, old man—how about that?"

"I had some idea of this in my mind when I cross-examined Batts at the inquest. But now, my young Sherlock Holmes, we come to the question—if your little friend didn't kill Salsbrigg, who did?"

"I'll tell you. Someone who knew that old S. was staying late at the office, someone who knew that eighteen hundred pounds was in the safe! We all knew the money was there, but none of us had any idea that the old man was coming back after hours. It very seldom happens."

"That's all very well. But who did know, then, that Salsbrigg had come back and that this money was in the safe?"

Cradock looked the other in the eyes.

"Merritone," he said.

"Merritone? The chap that gave evidence at the inquest?"

"That's him. Now, listen! Old Salsbrigg was a pretty warm proposition; he had some dam' funny friends calling round to see him at the office. That is why he was so particular about never seeing people except by appointment. On the afternoon of the murder this fellow rolls up. Well, you've seen him: you know what he looks like. He butted in without an appointment and was in the clerks' room when the old man was telling off Birkie for giving Goldstein, the man that brought the eighteen hundred pounds, an appointment after banking hours. As soon as Salsbrigg was finished with Birkie, this Merritone chap, cool as a cucumber, walks into the old man's private office, and Salsbrigg, who had a pretty rough tongue when he liked, never said a word. They weren't long together, and the door slammed pretty fiercely when Merritone came out. Do you know what I think? I believe Merritone had some sort of a hold over the old man, and had come round to raise the wind. Salsbrigg looked at him pretty old-fashioned when Merritone first came into the office."

Brewster puffed meditatively at his pipe.

"Blackmail, eh?"

"Something like that."

"But what do you know to prove that Merritone knew that Salsbrigg was coming back?"

"Nothing positive. But as Merritone was leaving the office, the light in the old man's room went out, and we heard his private door leading into the corridor slam. That means they must have quitted the building practically at the same time. I can guess where the old man went—to the Bodega. He generally went out and had a couple if anything upset him. Merritone might have shadowed him. If he had only meant to rob the safe, he would have wanted to see old Salsbrigg out of the way first."

Brewster nodded grimly. Then he stood up and tapped the ashes out of his pipe.

"If you will apply your gifts of deduction for the next ten minutes to divining what the wild waves are saying," he remarked, "I will step up to the telegraph-office and send a wire. We will then go up to the North Foreland and see if the air on the links will blow some of the cobwebs out of our minds."

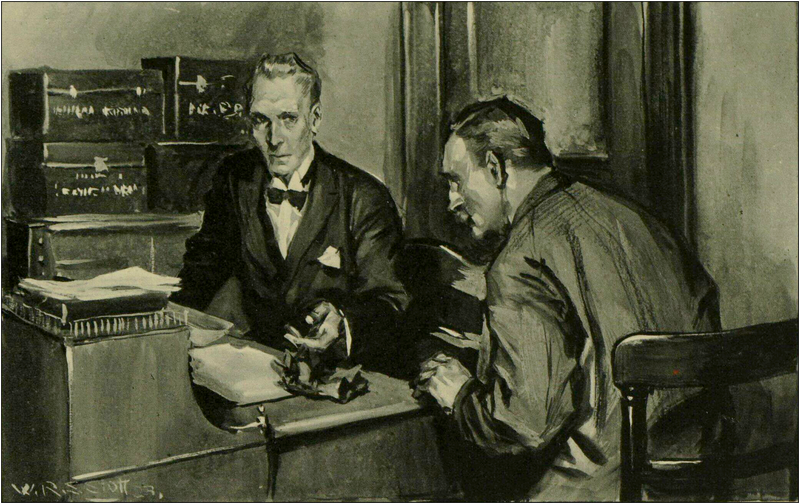

THREE days later, Detective-Inspector Coleburn sat opposite Mr. Harley Brewster in the latter's office in Southampton Street.

"I hold no brief for Merritone, Mr. Brewster," the detective was saying; "but because a man's a crook, it doesn't follow he's a murderer. And to be perfectly frank with you, it'll take a great deal more than Merritone's record—he's done an aggregate of fifteen years' penal servitude and shorter sentences, they tell me at the Yard—to shake the evidence against Birkinshaw. I grant you Merritone probably came to squeeze Salsbrigg for a bit; they were old friends, you know—in fact, Merritone was jugged for the first time over one of Salsbrigg's swindles; but, dearie me, there's not a particle of evidence to connect him with the murder."

"Not yet," said Brewster bluntly, "but I believe there will be, Inspector, if we get word quickly of any of the notes being cashed. As you got the numbers from Goldstein we should hear at once. We know that Merritone is broke to the wide, that he skipped from his boarding-house in Kilburn without paying the bill. I do sincerely hope that you're hot after him."

"As hot as we should be after any other old lag who falls back upon his old tricks, Mr. Brewster. But I fear very much you're drawing a red herring across the trail, sir."

"Then," said the solicitor, opening a drawer in the desk, "take a look at this!"

"Then," said the solicitor, opening a drawer in the desk, "take a look at this!"

And he flung on the blotter a stained and crumpled doeskin glove. Once it had been white, but now it was grimy and sodden as though it had been left out in the rain for days. Palm and fingers were tinged a dull terracotta.

"Blood," said Brewster, and pointed at the stain. "They brought me that this morning, Inspector. It was picked up in the air shaft between Casino House and the building backing on to it, overlooked by the window on the landing outside Salsbrigg's office. Perhaps you remarked the gloves that Mr. Claud Merritone was wearing at the inquest. A gentleman of settled habits, it would seem."

"I'll take charge of this," said the Inspector hoarsely.

"By all means," Brewster acquiesced smilingly. "That's why I asked you to call upon me this morning. Come in!"

His clerk entered with a card, which he laid silently before the lawyer. Brewster's hand went up and eased his collar. He turned and exchanged a silent glance with his clerk.

"I'll leave you, Mr. Brewster," said the detective, rising and buttoning up his overcoat. "Good-day to you, sir."

The moment he had gone the solicitor turned to his clerk.

"Show the lady in, Simmons," he said.

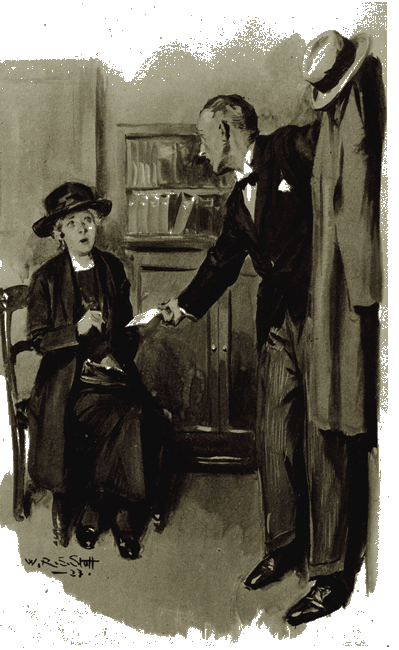

It was a woman very simply dressed in black, pale of face, and prematurely grey.

"Mrs. Salsbrigg?" said Brewster, looking at the card. "Won't you sit down? You wished to speak to me about my client, Mr. Birkinshaw?"

His voice was rather stern. She noticed it, for she said hastily:

"To help him, Mr. Brewster. He will need money for his defence. I was in Sicily, at Palermo, when I heard the news. My husband and I have lived apart for many years, and I don't see the English newspapers regularly. It was only four days ago that I heard of the terrible disaster that has overtaken my old friend. I was at my wits' end to know what to do, for I had no address to which to write, so I came myself to say that any money that is required for his defence is at your disposal."

"That question has no urgency," said the solicitor rather severely.

"That was not the sole object of my visit," the woman rejoined. "Before you hear my story, Mr. Brewster, let me say that, in spite of all appearances, I am convinced that Mr. Birkinshaw is incapable of this terrible crime. Five years ago I had to leave my husband. I invested my savings in a small hat-shop in Manchester. It did not prosper; I borrowed money; my forewoman robbed me; and finally I was left absolutely penniless with two children to support. To avoid my creditors I fled in a moment of panic to France. Thence I wrote to Albert Birkinshaw, whom I had known in happier days, for I would not appeal to my husband, God rest his soul!

"Albert Birkinshaw was a true friend. Not only did he send me money to tide over the crisis, but he undertook the whole settlement of my affairs and began himself to pay off the money due under the arrangement he had made. Only this year, since the boarding-house I started at Palermo began to do well, has he consented to let me start repayment of the three hundred pounds or more I owe him. The tragedy of it is that he paid the last instalment of the debt on the very day of the murder through which I inherit the money due to me under my marriage settlement."

Brewster looked up quickly.

"You say that Mr. Birkinshaw made this last payment on the day of the murder?" he said. "You realise, I suppose, that this makes things look blacker than ever for him. You see, a sum of eighteen hundred pounds is missing. It will be said that part of this sum went to make this payment."

She nodded with tense face.

"That is not all," she said, and lowered her voice. "May I speak freely, Mr. Brewster?"

"Nothing you say will pass these four walls, Mrs. Salsbrigg, without your consent," he assured her.

She opened her bag and drew out a folded paper.

"Have they found out about this telegram that Mr. Birkinshaw sent me on the evening of the murder?" she asked.

Brewster's eyebrows went up. "May I see it?" he asked, trying to appear calm.

She hesitated. "We must keep it from the police at all costs," she faltered. "It would be fatal if it came out."

Brewster unfolded the telegram and read—

FINAL PAYMENT MADE TO-NIGHT. YOU ARE FREE.—BIRKINSHAW.

The solicitor whistled and cast his eyes up. Then, with a harassed air, he clawed the back of his head.

"This is the de-vil!" he remarked. "Sent off on the evening of the murder, you said? Let's see now—' de Londres 8 '—that's the date, Dec. 8—' 18.58.S.'—that's the time. Eighteen hours by Continental reckoning is 6 p.m.—that's 6.58 p.m...."

He broke off, with eyes goggling.

"Simmons!" he shouted. "Simmons!"

The amazed clerk appeared.

"A taxi quick! I'm going to Brixton Prison!"

The clerk vanished.

"But what does it all mean?" cried Mrs. Salsbrigg.

"Mean?" roared Brewster, grabbing his hat. "Good God, Madam, don't you understand? Look at the time of despatch on this telegram—6.58! Your husband was murdered at seven o'clock, or perhaps a few-minutes sooner or later. If Birkinshaw can prove that he handed this message in personally at any telegraph-office that is more than, say, five minutes' distance from Casino House, he has established an unshakable alibi. Why the devil they don't put the office of despatch on foreign telegrams beats me!"

"Mean?" roared Brewster, grabbing his hat...

"Look at the time of despatch on this telegram."

"Taxi, Sir!" panted Simmons at the door.

BY three o'clock that afternoon the good creditable witness for which Mr. Harley Brewster's soul had hungered had been found. On Birkinshaw's indications, the solicitor tracked down the damsel whose severe regard had so flustered the clerk as he had scribbled out his telegram within two minutes of the closing hour of the Dover Street post-office. To Brewster's enraptured gaze she appeared like a being from another sphere as, when the original yellow form was laid before her, with becoming hauteur she immediately described the "little fellow with pince-nez and a sandy moustache" who had handed it in. And so, on the very day on which Detective-Inspector Coleburn left for Ostend to take charge of a smartly dressed Englishman, tall and dark and sallow, detained by the Belgian police for attempting to change one of the hundred-pound notes stolen from Salsbrigg's safe, Albert Birkinshaw found himself a free man.

Harley Brewster entertained his client, Mrs. Salsbrigg, and Cradock at lunch to celebrate the occasion.

"What beats me, Birkinshaw," the solicitor remarked, "is why you should have withheld from your solicitor the one vital piece of information that would have secured your immediate release."

"Eh, what?" said the little man, who had been gazing intently at the lady. Brewster repeated his question. Birkinshaw coloured up.

"I was afraid they'd bring Em'ly—I mean, Mrs. Salsbrigg—into it," he replied dreamily. "The wording of that wire was a bit compromising, y'know. They'd have said Em'ly—Mrs. Salsbrigg—and I had arranged to get rid of Mr. Salsbrigg."

"But, dash it all, the time, man—the time! It was a perfect alibi!"

One of Mr. Birkinshaw's hands disappeared beneath the table-cloth. An expression of seraphic contentment dawned on his face.

"I'm afraid I never thought of that."

"A bit dull, your friend," whispered Brewster behind the menu to Cradock. "Half-asleep he seems to me sometimes." Cradock grinned.

"That's what old Salsbrigg told him," he rejoined. "But we mustn't say things like that about him now. He's to be the new boss, y'know, old man!"

He nodded significantly and drew Mr. Brewster's attention to his two guests facing him across the table. They were holding hands beneath the cloth.

They were holding hands beneath the cloth.

"Em'ly!" sighed Mr. Birkinshaw.

"Dear Albert!" crooned Mrs. Salsbrigg.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.