RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

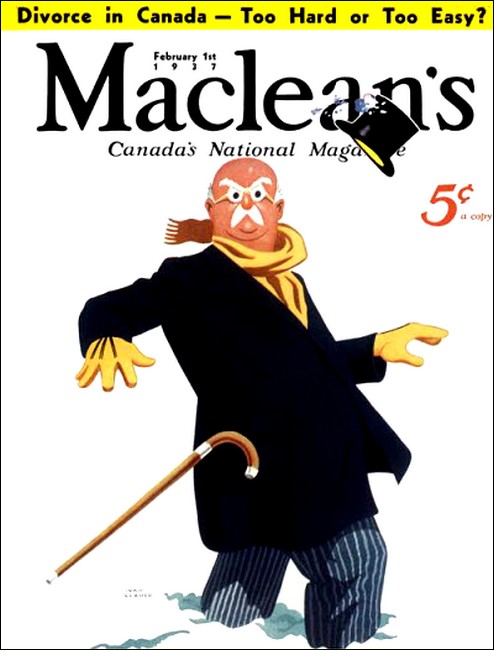

Maclean's, 1 February 1937, with "The Dot-and-Carry Case"

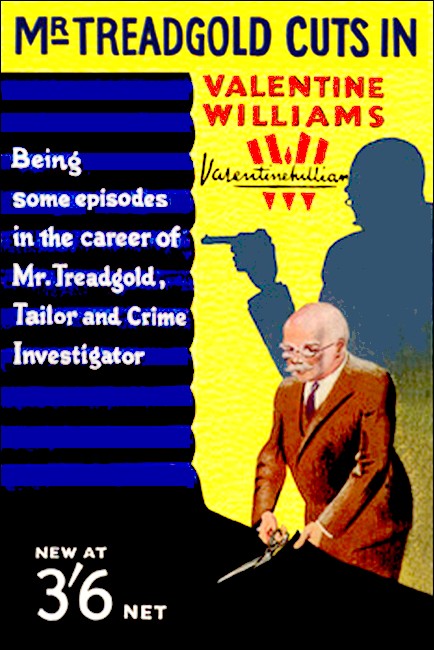

"Mr. Treadgold Cuts In," Hodder &

Stoughton, London, 1937, with "The Dot-and-Carry Case"

Horace Treadgold, tailor detective, untangles a scandal to unravel a murder.

IT was obvious that Chief Inspector Manderton had come

straight from the inquest to Mr. Treadgold's to discuss the

Frohawk case. The evening newspapers were scattered about the

sitting room when I reached Bury Street; I could see their

flaming headlines: "Wealthy Stockbroker's Double Life," and "Rich

Man Jekyll and Hyde;" while in the Stop Press was recorded the

verdict of the coroner's jury—in the case of Frohawk,

wilful murder against Leila Trent, and in the case of the girl,

felo de se.

I should not have said that the Dot-and-Carry case, as the newspapers called it, had any appeal for Mr. Treadgold. Away from the prosperous tailoring business he conducts in Savile Row, stamp collecting and crime investigation are his hobbies; his interest in crime is directed toward the mysterious, the bizarre and the unusual. The circumstances of the suicide pact between Dudley Frohawk, the middle-aged London stockbroker, and the little dancing girl, were tragic but not uncommon. As Manderton remarked, Frohawk was not the first married man to have an affair with a chorus lady behind his wife's back. They found them dead together in Frohawk's car outside the Dot-and-Carry, a raffish sort of roadhouse on the Great North Road—the man with a bullet through his heart as he sat at the wheel, the girl's body slumped across him. She had shot herself through the temple—the gun was still in her hand. She was not known to have possessed a pistol and actually the ownership had not been traced, but, as Manderton said, that proved nothing—the only fingerprints on the gun were hers.

It was not until morning that the elegant car was noticed standing abandoned at the parking place. The medical evidence showed that the couple had been dead for about six hours, which would put the hour of death back to around midnight. This accorded with the other facts. No one saw Frohawk arrive; but the girl, who was appearing with a troupe of dancers in the cabaret, vanished from the dressing room soon after the first show finished at 11.15 o'clock and did not turn up for the second performance starting at 12.30. It was thought she had gone gallivanting off in a car with some man from the audience—the Dot-and-Carry was that sort of establishment. She was still wearing her stage costume under a coat when she was found.

That no one heard the shots was not surprising. The parking place had no attendant and was a good 100 yards from the roadhouse; and the dance band, a very noisy one, was going full blast all night, added to which there was the continual flow of nightly heavy traffic along the Great North Road.

LEILA TRENT occupied a tiny flat in Soho. The house had no

porter, but other tenants—they were all women—spoke

of various "gentlemen friends" who came calling on her. The

police apparently had failed to identify Dudley Frohawk as one of

these, although it was known to members of the dancing troupe at

the Dot-and-Carry that Leila had a rich admirer whom she

called Dudley. Actually, the only communication the police had

been able to trace between the dead couple was a telephone call

which Frohawk had received at his office late in the afternoon on

the day before the tragedy was discovered. A woman, who refused

to give her name, had called up and spoken to him. Frohawk then

told his secretary to telephone his house that he would be dining

at his club as he had to go down to the country to see a client

after dinner, and also to instruct the garage to deliver his car

at his club at nine o'clock. He dined at the club and left in his

car, driving himself, at about 9.30—he was never seen alive

again.

Frohawk's background was typical of an average well-to-do Londoner—Winchester; New College, Oxford; four years of the war and a D.S.O.; prosperous business of his own; house in Kensington, devoted wife, boy at Oxford, girl "finishing" in Paris. It was not easy to see what the attraction for him was in a little guttersnipe like Leila Trent, picking a precarious livelihood between her "gentlemen friends" and the lower class of Soho night clubs, varied by an occasional cabaret engagement abroad. Yet the evidence was irrefutable. At the adjourned inquest Manderton put in her diary, showing that she had met Frohawk in the previous August—the tragedy occurred on November 21—at Juan-les-Pins, where she was filling an engagement at a night club. There were entries recording trips to Monte Carlo, Nice and Cannes. The police also produced various articles of Frohawk's found at the girl's apartment—some shirts and handkerchiefs and a suit of pyjamas, marked with his initials, a gold pencil-case, a diamond fox pin.

The widow identified the property, especially the gold pencil and the diamond pin, which she had given to her husband—he told her he had lost them—and confirmed the fact that in the summer Frohawk had spent a fortnight's holiday alone at Juan- les-Pins with friends; she had wished to stay in London as the house was being redecorated. To the coroner she declared that she had been happily married for twenty-four years, and had never had to complain of her husband's unfaithfulness. The coroner, expressing sympathy for the family, delivered himself of some unctuous remarks about "the hidden side of men's lives" and the jury returned its verdict as stated.

MANDERTON, who is a large, hectoring person, was in a somewhat

irascible frame of mind. "When you've been at this game as long

as I have, friend H.B.," he told Mr. Treadgold in a loud voice,

"you'll realize that Solomon knew what he was talking about when

he said that one of the things that passeth understanding is the

way of a man with a maid. Especially when it's a fellow in middle

life."

"I wouldn't contradict you," H.B. replied urbanely. He had elected to spend an evening at home with his stamp collection, and sat at the desk, poring over the volumes spread out upon it.

"And yet the verdict of the coroner's jury isn't good enough for you?" the inspector challenged.

Mr. Treadgold smiled and delicately lifted a stamp on its hinge. "Did I say so?"

"Isn't it a fact that you've an appointment with Mrs. Frohawk this evening?"

H.B. chuckled. "So that's why you dropped in!"

"I'm not going along, the lord forbid! But I don't want you to fill the poor lady's head with a lot of your Sherlock Holmes nonsense."

Mr. Treadgold laid his eye to his lens. "'Tristram Shandy,' a work from which you've sometimes heard me quote," he remarked, "has some highly pertinent observations on the importance of allowing people to ride their hobbyhorses. You, my dear Manderton, are a detective and breed whippets in your spare time; I'm a tailor, and when I'm not measuring my fellow man for suits, calculating his capacity for crime is one of my diversions. If people want to consult me..."

Manderton, who hated to be opposed, ground his teeth. "Lord, you've had your successes, I'm not denying it. But the Frohawk case is closed. If you go poking into it, you'll only stir up a lot of mud."

Mr. Treadgold looked up. "Now you're making me curious. As George Duckett here will tell you"—he winked at me—"my main interest in crime springs from my incurable inquisitiveness. You didn't tell the coroner why she shot him, did you?"

"I didn't tell the coroner a lot of things. Listen, H.B., this is a beastly business. The girl was no good. She was running round with Malay Joe, Long Grady, the dope-peddling crowd. I've a hunch she was selling the stuff for them round places like this Dot-and-Carry dump."

"Was Frohawk a drug-taker?"

The inspector shook his head. "Not on your life. That's what makes it even worse. The girl wasn't either. She was in the game for the commission she made out of it; and here's Frohawk, a man of education, taking up with a nasty bit of work like that. There was evidently a rotten streak in him somewhere, but that's neither here nor there, now that he's dead. I let the baggage down easy in my evidence, on account of the family, see, so why should you come in and dig up a lot of dirt?"

Tranquilly Mr. Treadgold applied his gauge to a perforation. "Have you the girl's diary with you?"

THE small, leather-bound volume which Manderton produced was

not kept, properly speaking, as a diary. It was rather a series

of notes—of engagements, of telephone numbers and

addresses, of sums paid to hairdressers and the like. It was

characteristic of Mr. Treadgold that out of this jumble of

jottings, set down in an illiterate hand, his observant eye

should have seized and his retentive memory stored up the one

essential date upon which his masterly elucidation of the Dot-

and-Carry case was to turn. For me I saw only a mass of

haphazard entries, starting with the month of August at which the

inspector opened the book:

"Leave for J.-les-Pins 11 a.m.;"

"Henna Rinse 150 francs;"

"Edna owes 100 francs."

Manderton drew our attention to the entry under date August 15.

"Manicure 25 francs," we read. "Meet Dudley Frohawk (sic) Potinière after show."

A day or two later it was,

"To Nice with D.F. Lunched Negresco."

Presently the "D.F." became "Dudley."

"To Cannes with Dudley. Danced Palm Beach Casino;"

"Monte with Dudley. Won 450 francs."

The diary showed that she returned to London in the last week of August, "Dudley" seeing her off by the Blue Train. At the end of September, when she was back in London, "Dudley" reappeared. They dined together on the 30th and again on the 15th of October. He took her dancing on the 20th—"my birthday," the girl noted—and again on the 1st of November. The last entry was November 9:

"Cochran's revue and supper with Dudley."

There was no further mention of him after that—the tragedy occurred on November 21.

"May I borrow this for a day or two?" Mr. Treadgold asked the inspector, holding up the diary.

"Help yourself," said the inspector, rising from his chair and taking his hat. "But I'm telling you now, you'd best let sleeping dogs lie!"

He went away then, and ten minutes later we drove out to Kensington. Mrs. Frohawk was a dark-haired woman with a firm chin and considerable dignity.

"I don't fear the truth," she told Mr. Treadgold. "I trusted my husband—I still trust him—and I know that the more light you can shed on this horrible affair, the better he'll come out of it." Rather wistfully, she added: "I realize I'm probably the only person who still believes in him. Even the children—they're very sweet to me but, the way young people are nowadays, I can see that, without blaming him particularly, they're prepared to believe that their father was carrying on an intrigue with this girl. I'm not so conceited as to think I was necessarily the only woman in Dudley's life. But he was a refined man, Mr. Treadgold, and it's unthinkable to me, even in face of the evidence, that he should have compromised himself with a woman of this type."

Mr. Treadgold, portly, paternal, rubbed his nose reflectively.

"A crime, Mrs. Frohawk," he observed blandly, "is rather like a painting. That's to say, it must conform to certain rules of construction. The figures depicted must stand in a proper relation to the background. The reason I asked that we might meet at your home rather than at my place was because I wanted to see for myself your husband's environment—the clothes he wore, the books he read, the things he liked—in order to judge just how he fitted into the setting of Leila Trent and her world."

It was rather thrilling to observe how adroitly H.B., with Mrs. Frohawk's assistance, contrived to reconstruct the atmosphere surrounding the dead man. Mr. Treadgold had to see Frohawk's study, his dressing room even; and he actually persuaded Mrs. Frohawk to show him some of her husband's letters to her. Little by little the various photographs of the dead man which, at Mr. Treadgold's request, the widow laid before us, seemed to come to life. An attractive personality emerged, tender yet masterful, intensely virile, an open-air man, fond of tennis and golf, a pipe-smoker, who dressed in tweeds and soft collars by preference, a collector of books on bird life, a Conservative and a citizen who took his duties seriously. Among other things, he was past master of one of the great City Livery companies and, as Mrs. Frohawk informed us, contemplated standing for sheriff in the following year.

Mr. Treadgold asked a lot of questions regarding Frohawk's evening engagements during the time since his return from Juan- les-Pins, but here Mrs. Frohawk was unable to help him much. She kept no diary; she was vague about dates. It was no uncommon thing for her husband to dine in town; he often called on customers after dinner. With regard to the diamond fox pin which was found in the girl's apartment, she noticed that he had no longer worn it and questioned him about it—it might have been a fortnight or so after his return from France. He told her then he thought it must have been stolen from him when he was abroad.

"He wasn't staying at a hotel, was he?" Mr. Treadgold remarked. "I thought he was stopping with friends."

That was right, Mrs. Frohawk agreed; he was the guest of Frank and Myra Donaldson. But they only had a hired villa; the servants were engaged locally.

"I wanted Dudley to write and ask them if his pin had been found," she told us, "but he said something about not wishing to cast any reflection upon the servants—at any rate, he didn't write. About the gold pencil, I didn't know that he'd lost it."

"I suppose you wouldn't have missed those shirts and handkerchiefs of his?" H.B. suggested.

She shook her head. "Dudley had dozens of shirts and things, as you may have noticed in his dressing room," she replied. "I knew really very little about his wardrobe."

Mr. Treadgold made her give him the Donaldsons' address—they lived in Chelsea—and we took our leave.

"Tomorrow," H.B. promised me as we walked away from the house, "we'll have a look at Leila Trent's background."

I FETCHED him at Savile Row at the closing hour next day and

we took a taxi to Stonefield Street, off Shaftesbury Avenue,

where the dead girl's flat was situated. It was a ramshackle

Georgian mansion, with four floors of apartments on a black

staircase smelling of cheese above a delicatessen shop. Leila

Trent lived at the top of the house, and when we banged on the

door—there was no bell—a blond young woman opened it.

"Was it for the gas account?" she asked rather nervously.

Mr. Treadgold gave her his blandest smile. "Nothing so unpleasant," he rejoined. "Are you a friend of Leila Trent's?"

She nodded. "You're reporters, likely?" She spoke with a flat provincial burr. "There were a lot of them round here last week. Do you want to interview me? I'm Edna Masters; I worked with Leila in the troupe at the Dot-and-Carry. You can come in if you don't mind the room being in a state—the hire purchase have took most of the furniture away and I'm just packing her things to send to her sister."

The tiny sitting room with its colored photographs of undraped females and cheap German knickknacks on the mantelpiece had a vulgar air. The Masters girl was a plump peroxide blonde. She succumbed with alacrity to Mr. Treadgold's most deferential manner, answering his questions with an ultra-genteel air. Leila Trent was a wild one, she confided. There were any number of very steady gentlemen as would have liked to take care of her, but there! she was never a one for sitting home with a book or the wireless, but must always be gadding about, round the night clubs and such places.

Did Miss Masters ever meet Leila's friend, Dudley Frohawk? H.B. interposed casually.

The girl gave him a knowing look. Catch Leila ever introducing her fellers to any other girl! But Leila had often spoken of Dudley—a perfect gentleman; she was crazy about him. Always as smart as smart and free with his money—he'd never take her out without first sending her a spray, carnations or lilies- of-the-valley. And a marvellous dancer. Once, when they were at the Palais de Danse at Hammersmith or one of those places, Leila had told her, the orchestra leader had wanted them to do an exhibition turn.

"Did Dudley Frohawk ever come to the Dot-and-Carry?" Mr. Treadgold next enquired.

Edna Masters veiled her eyes. "Not on your life."

"Why?"

"There was someone there she didn't want him to meet."

"Another gentleman friend?"

"Maybe."

"Leila Trent used to run round with Malay Joe's crowd, didn't she?" said Mr. Treadgold innocently.

The girl nodded. "She and Long Brady, one of that push, were as close as twenty minutes to eight before she met Dudley." She lowered her voice. "If you ask me, it was Brady telling her she'd have to give up Dudley drove her to it."

"You mean, he was blackmailing her—because she used to peddle the stuff for them?"

Edna Masters sprang to her feet in a panic. "I don't know nothing about that and I don't want to hear nothing about it." She looked at her watch. "I can't stay here gossiping all day. I've got to get out to the Dot-and-Carry for the first show." She practically pushed us out of the door.

HALF AN HOUR later I sat with Mr. Treadgold before the fire in

his chambers. "The picture," said H.B., breaking a silence that

had lasted all the way from Soho, "is all awry."

I shrugged my shoulders. "There's no accounting for tastes, especially where men's relations to women are concerned. I don't see why Frohawk shouldn't have fallen for this little drab and she for him—such things have happened before. The Masters girl gave us a perfectly rational explanation of the tragedy. Leila was in this fellow Brady's power; it was a choice between giving up Frohawk or going to jail, because, of course, Brady could have denounced her to the police. She decided she couldn't give up Frohawk."

Mr. Treadgold drove his fist into the palm of his hand. "Frohawk doesn't fit into the picture, I don't care what you say," he declared violently. "Yet there he is in the picture—at least, in the picture that unfolded itself when the door of his motor car was opened that morning. What's the inevitable deduction?"

"I've told you."

H.B. snorted. "'There's a worth in thy honest ignorance, brother Toby,'" he quoted, "''twere almost a pity to exchange it for knowledge!'" And then he barked at me: "What type of man do you suppose chorus ladies of the stamp of Edna Masters and Leila Trent regard as a perfect gentleman?"

Mr. Treadgold's habit of slugging me, in moments of emotional stress, with quotations from his beloved "Tristram Shandy" gets on my nerves at times and I made no reply. H.B. answered his own question.

"Something slick and slimy," he declaimed, "with a flower in his buttonhole and a diamond ring on his little finger and, oh, spats, and a fob and a gold-headed cane! What do you make of this Dudley fellow Edna Masters told us about, who sends his girl cheap sprays from the comer florist, who dances like a professional, who takes the lady to popular dance halls? It doesn't fit, George. This is an aspect of the life of gallantry a man of Frohawk's background knows nothing about, I swear. If he sends flowers, I bet it's orchids; if he takes a girl dancing, it's to one of the big hotels. And if any professional could describe a big upstanding he-man like Dudley Frohawk as a marvellous dancer, by Gad, I'll eat my bowler!"

"As for that," I told him crossly, "I know nothing, but I'll remind you that nowadays lots of men have taken up dancing as good exercise. For the rest, let me remark that it was probably Leila Trent and not Dudley who decided where they should go, and that a popular dance hall was more likely her choice than his. If you remember, on the Riviera he took her to all the right places—the Negresco at Nice, the Palm Beach Casino at Cannes."

H.B. nodded gravely. "A point well made, George," he observed. Then he drew Leila Trent's diary from his pocket and fell to studying it. Presently he looked up. "But supposing I'm right," he said, "supposing Frohawk doesn't fit in the picture?"

"But he's in the picture, H.B.!"

"He's in and he's not in." His voice was oddly tense. "Doesn't the thought convey anything to you?"

"Merely that you're talking nonsense!" He glanced down at the diary again. "Then will you tell me what the date of November 9 suggests to you?"

"The Lord Mayor's Show!" I answered ribaldly.

Mr. Treadgold took my reply in excellent part. "Nothing else?" he questioned good humoredly.

"Not a thing."

"And yet," he said, "I've a notion that the entry under this date"—he held up the little book—"may put us on the right track at last!" He drew the telephone toward him. "Go and get your dinner, George, I'm going to be busy."

I TOLD him I'd wait and give him a chop at my club, but he

said he had no time. I telephoned him after dinner, but he had

gone out and all next day he was away from Savile Row. I went

round there shortly before closing time and found he had just

come in. He was signing his letters.

His air was curiously elated. "As soon as I've polished off these I'm going down to Scotland Yard," he told me.

"Dug up some dirt for Manderton, have you?"

He grinned. "I've some soil for him to sift, anyway."

"You've been busy, haven't you?"

He nodded, signing away. "I've been chasing the Donaldsons, Frohawk's hosts at Juan-les-Pins—they were out of town. Then I had to go to the City, and afterward Edna Masters came to tea with me. Perhaps you didn't know she was out at Juan with Leila Trent? Yet it's in the diary: 'Edna owes 100 francs,' do you remember? Never mind, I missed it myself the first time. Come on, Manderton's expecting us."

It seemed to me that the inspector received us, in his poky little office, with a slightly supercilious air.

"What do you know of a fellow called Paul Morosini?" H.B. demanded.

Manderton frowned. "So you've been talking to Malay Joe and the boys, have you?" he rasped.

Mr. Treadgold's blue eyes lit up. "Is he in that outfit?"

The other gave his harsh laugh. "Not on your sweet life. He's here for a Belgian syndicate that's trying to muscle in on their organization. The boys are breathing blue murder, and this Morosini guy's for the high jump if they ever get their hands on him. They laid a trap for him the other night at a hang-out of his in Soho—I heard about it when I was tracing the movements of Long Brady and the others on the evening of the Frohawk shooting. None of them was at the Dot-and-Carry that night; they were over in Soho, waiting to give Morosini the works. But he was too smart for them."

"He's in London, then?"

"He's been here for months, but the gang has only just twigged what he was up to."

"Where does he hang out?"

"All over the shop. I only picked up his trail over the Dot-and-Carry affair. We're hot on his heels, though. At any minute I expect to hear we've run him to earth. Not that it matters what the boys do to him, but we don't let the gangs take the law into their own hands in this country."

"Is he in the Rogues' Gallery?"

"You bet. I've got his file here." He tossed a photograph across the desk. "That's a French police picture. He's done various stretches in France for selling dope."

Mr. Treadgold gurgled happily. "The perfect gentleman, eh, George?" he said to me and winked. It was a vulgar face that confronted us in three positions, with dark hair slicked down, impudent black eyes, a natty mustache. "Born Malta, 1899," Mr. Treadgold read out. "Expert jewel thief, white-slave trafficker, narcotic smuggler. Speaks fluently English, French, Italian. Originally hotel valet. Good appearance, plausible manner."

The desk telephone interrupted him. Manderton answered it. "There's a lady asking for you," he informed Mr. Treadgold.

"Would you mind if she came up?"

IT was Edna Masters. Mr. Treadgold handed her the photograph.

"Ever seen this gentleman before, my dear?"

She scrutinized the face, then nodded. "He was with Leila one day at Nice—at the Negresco. We had drinks at the bar."

"Is it the man she called Dudley?"

I saw the inspector stiffen. The girl shook her head. "I didn't get the name. But there, she had so many gentlemen friends. I only saw this chap the once."

"What's the layout, H.B.?" Manderton demanded.

"Impersonation," said Mr. Treadgold. "Dr. Hans Gross, with whose 'Handbook for Examining Magistrates' you're certainly familiar, says that the most important thing in any criminal investigation is to determine the right moment at which to form a fixed opinion about the case. My fixed opinion was that Frohawk never fitted into the picture. I came to the conclusion, therefore, that someone had been impersonating him. Those shirts and handkerchiefs of his found at the girl's fiat suggested a dishonest servant—as you know, it's the commonest thing to find valets rigging themselves up in their masters' clothes and impersonating them. My mind went back to that diary"—he produced the little book. "What does the date November 9 suggest to you?"

Manderton replied as I had done: "The Lord Mayor's Show."

"The Lord Mayor's banquet," Mr. Treadgold corrected him. "Frohawk was high up in the livery of one of the great City companies, a potential sheriff—I made sure he would have been present at the Guildhall banquet on the night of November 9. Well, I checked up and he was. Yet Leila Trent records that on that evening he took her to the theatre and to supper." He laid the diary, open at the date in question, on the desk.

"I have seen the Donaldsons, Frohawk's hosts at Juan-les- Pins," Mr. Treadgold went on. "They had a butler named Simmons whom they picked up locally but had to get rid of owing to the way he ran up their bills. I've spoken to the Commissaire de Police at Juan-les-Pins on the telephone, and he tells me that Simmons is thought to be identical with this man, Paul Morosini—it's believed he took the job with the Donaldsons as a cover for his activities in peddling drugs to the summer visitors. I've no doubt that, in order to cut a dash with Leila Trent, he gave himself out to be Dudley Frohawk, the wealthy stockbroker from London, and presented her with Frohawk's diamond pin and gold pencil, which he had pilfered. You've told us that he came to London in order to barge into this other dope ring, and I imagine he lost no time in getting in touch with his old flame, Leila, again."

Manderton grunted. "Can you explain why she should have rung up the real Frohawk and why he should have gone to meet her?"

"I think so. You say yourself that Morosini had been in hiding. Probably Leila discovered that the gang was laying for him. I can well believe that Morosini forbade her ever to ring him up at his office—Frohawk's office, that is—but she had to find him quickly to warn him about this raid the gang was planning on his hang-out in Soho. Frohawk went to the Dot- and-Carry to meet her because he was naturally curious to know who was impersonating him."

"Then it was Morosini who killed them? Why?"

"You say the gang nearly caught him at this place in Soho. He knew that Long Brady and his crowd frequented the Dot-and- Carry; he must have jumped to the conclusion that only Leila could have given him away. It's my guess that he went straight out to the Dot-and-Carry and probably arrived just as the girl emerged to meet Frohawk at his car. He recognized Frohawk as the Donaldsons' guest at Juan-les-Pins and was confirmed in his belief that the girl was double-crossing him. He was probably full of hop—the French police describe him as a chronic morphinomane—and in that condition he shot the girl and, to cover up his traces, Frohawk as well. I believe you'll find that that pistol was his."

The inspector frowned and tugged at his heavy mustache. "We have to find him first," he remarked bleakly, but added more cheerfully: "We've narrowed the search down to the Tottenham Court Road area—we ought to pull him in tonight."

THEY found Paul Morosini next day, but not in the salubrious

environment of the Tottenham Court Road. He lay face downward in

a ditch near St. Albans, his smart clothes smeared with mud and

blood, his hands tied behind him, three bullets in his head. In

the pocket of his overcoat was a message, laboriously printed in

block capitals on a dirty half-sheet of note paper. It was

addressed, "To the Police," and unsigned. It read:

###LETTER

"Look at the trouble we save you guys. You didn't know, did you, that it was this rat as killed Leila Trent and her toff? He thought she had squealed on him, which is the bunk because he had it coming to him. This is on the level—he told us he done it before we gave him the works."

Manderton brought us the message the same evening at Bury Street, where he looked in on his way back from St. Albans and a long day's investigation with the Flying Squad. Mr. Treadgold smiled delightedly as he read it.

"At last," he sighed, "the pieces fit!" With evident satisfaction he rubbed his hands together.

The inspector grinned indulgently. "Pretty cockahoop, aren't you?"

"I hope," said Mr. Treadgold rather stiffly, "I may indulge in a justifiable feeling of pride at finding the process of logical reasoning leading to a logical conclusion. But, as a matter of fact, I was thinking of Mrs. Frohawk. Trust such as hers merits its reward. The quality of faith is so rare in a material world today, inspector, that when it's justified, one may fancy that the angels rejoice."

And, as though to illustrate his trope, his kindly features, broad and pinkly glowing with health, were wreathed in a seraphic smile.

"The Curiosity of Mr. Treadgold," Houghton

Mifflin Co., Boston, 1937, with "The Blue Ushabti"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.