RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

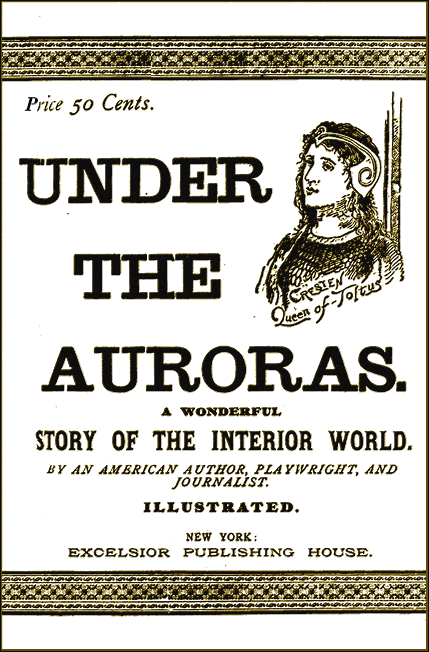

"Under the Auroras," first edition, 1888

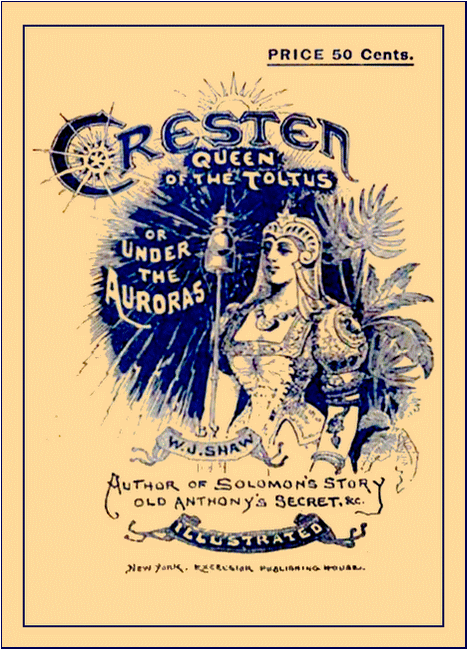

"Cresten, Queen of the Toltus," reprint with new title, 1892

"Under the Auroras," title page of first edition, 1888

Introduction of the narrator, the man in the hair-cloth suit.

THE whole responsibility for this story is thrown upon the shoulders of the narrator, who hath departed this life, and is, therefore, out of harm's way. It appears from his narrative that if the unfortunate Arctic explorer, Captain Hall, had been enabled to advance even 100 miles beyond where he could see with his glass, that the land had put off its mantle of snow, he would have been rounding the earth's verge, and have fairly entered upon a land of eternal day, peopled by peculiar and hitherto unheard-of races. He locates the kingdom of that most remarkable woman, Cresten, Queen of the Toltus, on the interior of the globe, upon the Asiatic side and north of the 55th parallel. As the mere amanuensis, I have followed the history of this Queen, and been deeply interested in her wars, her adventures, and her nobility and amiability of character, and I have reason to be grateful to her for the wonderful information which she has imparted by the way. I have not the shadow of a doubt that, had this narration not been made to me, I should have gone to my grave without having learned how man and all other animals originated; where the white races came from; when the Deluge occurred, and what caused it; why men lived to count their years by hundreds anterior to the Deluge; when and why the ice-belt was once farther south on the exterior globe; when and how mountain ranges were uplifted; together with the causes of geysers, volcanoes, and earthquakes; what forces operate and how to turn the earth on its axis; how meteors are formed, and where they come from; and how many other phenomena, including the Auroras—Borealis and Australis—which have always troubled me to account for, are produced. I say: I simply desire to record my gratitude.

THE MAN IN THE HAIR-CLOTH SUIT—THE AIR- SHIP—OFF ON A POLAR CURRENT—BEYOND THE MAGNETIC POLE—BENEATH THE AURORA BOREALIS.

I COULD very satisfactorily account for my own presence

at Port St. Julian, in barren Patagonia, the guest, pro

tem., of a resident priest, Father Pietri; but that is

unnecessary, since I tell another man's story. I was engaged in

reading a history of Arctic explorations, and I remember very

distinctly just where I left off, on being interrupted by the

entrance of the priest, for it afterward seemed to be one of

those strange coincidences which occasionally cause us to wonder

if much that we do is not at the suggestion of occult influence

which we cannot distinguish from the operation of our own free

will. I was reading the last despatch written by Captain Hall,

from the highest latitude ever trod by the foot of a white man,

being 82° 29′, from which he beheld land stretching to the

northward as far as 83° 5′. I had just read the following

paragraphs:

"We find this a much warmer country than we expected. From Cape Alexander, the mountains on either side of the Kennedy Channel and Robeson Strait we found entirely bare of snow and ice, with the exception of a glacier that we saw covering about latitude 80° 30′ east side the strait and extending in an east-northeast direction, as far as can be seen from the mountains, by Polaris Bay.

"We have found that the country abounds with life and seals, game, geese, ducks, musk-cattle, rabbits, wolves, foxes, bears, partridges, lemmings, etc."

The priest entered with a significant smile on his face, and covertly touched his forehead with the forefinger of his right hand. He intended to inform me that the creature who followed him in was crazy. Possibly, any one with Father Pietri's imperfect knowledge of English might have reached the same conclusion. The priest's judgment, however, had been based on the man's strange costume—grizzled, unkempt hair and beard, and emaciated body. To me his manner and speech both proclaimed the knowledgeable gentleman. Upon being introduced, he remarked:

"Unfortunately, sir, I can speak only English, Norwegian and one or two other languages which no one save myself, on this exterior globe, understands. I am glad to find some one who can speak English."

"English is my native tongue, sir," I replied. "Please have a seat."

I noticed that his costume was peculiar. It was woven apparently out of a very fine and glossy brown hair, and consisted, beginning at his feet, of sandals, very heavily plaited hose attached to trunks below the knees, a sack with holes for head and arms, gathered at the waist and falling in folds to the knees, and over this a loose sack-coat, with sleeves gathered at the wrists. Beneath this hair-cloth covering was underclothing somewhat resembling linen. He held in his hand, with a certain indefinable grace that was noticeable, a tasseled cap, woven or plaited like the hose. It was encircled by a brass, as I supposed, but in fact light gold band, with the figure of a coiled serpent embossed upon it. He took the proffered seat, and perceiving that his clothes engaged my attention, remarked:

"My clothing is not familiar to you. My story, sir, will account for my appearance. To the southward I've met with the native Patagonians only, and on the whaling vessel which landed me upon this continent, the one man who spoke English at once reached the conclusion that I was a lunatic, when I attempted to tell my story."

"I certainly am not of the opinion that you are now insane," replied.

"Yet you may reach the same conclusion when I have told it," he said. "And if you care to hear it, I wish to exact a promise from you, as a gentleman, that you will give it publicity."

"Permit me to ask the reason for your request."

"Certainly, sir, because I think it is something the world should know, and because I am in the final stages of that disease, against which all skill is useless. Only my desire to communicate what I have discovered has sustained me, otherwise I would have avoided the suffering I have endured in attempting to reach this port, and quietly have resigned myself to my fate in some Patagonian's hovel."

At first he had stood in the shadow, and I had not noticed what the fuller light revealed, that he was indeed a very sick man. I gave him my promise at once, for which he was so profuse in thanks as to confirm his statement, that the publication of his story was the sole purpose of his now short life. But first I explained to Father Pietri his condition, and the worthy priest insisted that he should be made comfortable before he began his narration. He was so eager to begin that he reluctantly yielded to our persuasion to refresh himself for his task. It was toward the evening of the same day, when, lying upon a couch in my room, he began the following strange story. It was not continuous, since it was frequently interrupted by violent fits of coughing, which threatened to cut it short in the middle.

"All my life long," he said, "I have been an investigator of natural phenomena, not in that systematic way which characterizes the true scientist, but with equal diligence and persistency. My name is Amos Jackson, and twenty-five years ago I resided in the city of Chicago. There were two of us, bachelors, who occupied the same room and were inclined to the same pursuits and studies. My companion's name was John Harding. One subject of special inquiry was air currents and another magnetic currents. I must give you some idea of our theories, in order that you may understand our reasons for entering upon so hazardous an undertaking as that which, if you will believe me, we accomplished. Permit me to ask if you have ever witnessed a cyclone?"

"Yes, sir; on one occasion only," I replied.

"Well, probably you know that the forward motion of some is quite deliberate and of others more rapid, but that their destructive velocity is around their own centres. Have you any doubt that the force which gives them that circular velocity is electricity?"

"I can imagine no other force that could operate to produce it," I replied.

"True, sir; no other force in nature could. It organizes, shapes, and controls them. They are circular, hollow, have positive and negative poles, a terribly destructive, attractive force at each vortex, and have often been seen crowned with electric light as they moved."

"I suppose that is all true, sir."

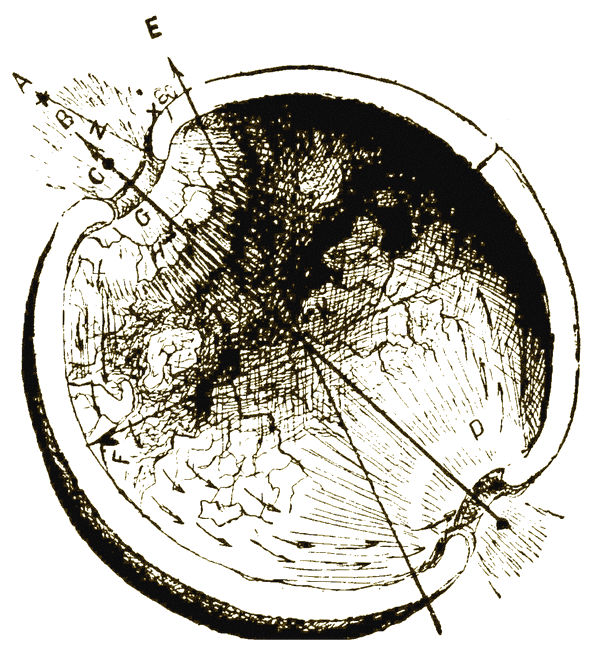

"Very well; imagine one of these, composed for the most part of solid matter, with an atmosphere about it, and you have an approximate idea of our conception of this earth and of the force that controls it. I will not waste my strength now in attempting to explain what we conceived to be the operation of the electric currents in producing the earth's forward and circular motions, since they were but crude conceptions, as a higher intelligence revealed to us later. Suffice it to say we were of the opinion that the earth is a great helix, a hollow globe, but a few hundred miles in thickness. We assumed there must be some way of reaching its interior, and arrived at the conclusion that the way was clearly determined by the earth's air currents and isothermal lines. We believed that the polar air currents were quite as constant between the equator and the poles as are the trade winds, tending east and west, and more so. It seemed to us to be only a question of maintaining the proper elevations, either to go or come upon the upper or lower polar currents. We were of the opinion, also, that the isothermal lines increased in curvature toward the poles, in such a ratio that somewhere east of northern Greenland might be found a tract, within the boundaries of which the temperature would be endurable over the frozen region at any time. You are doubtless aware that the isothermal line which passes through New York touches London eleven degrees farther north, and that which passes through central Labrador touches northern Europe twenty-one degrees farther north. Our calculations were based on established ratios and other considerations not necessary to mention. You will infer, that in our opinion, should it ever be reached by man, this region about the true pole would disappoint the common opinion regarding it, that it is a field of ice. Thus far permit me to inquire, do you discover any evidence that I am insane?"

"Your theories seem reasonable to one who has given such matters no more thought than myself," I replied.

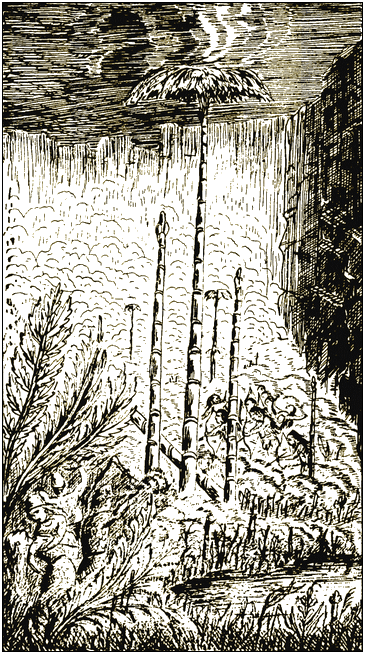

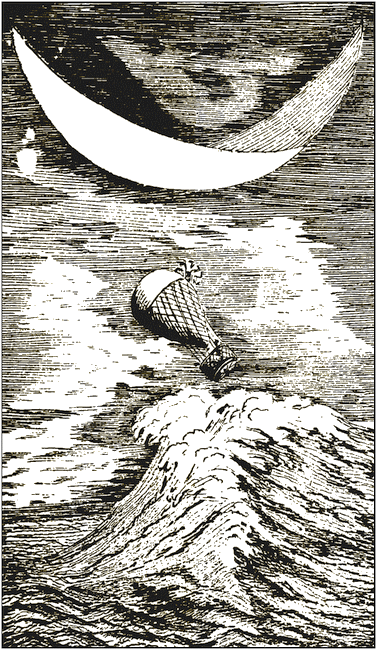

"Thank you! Then I may avoid establishing in your mind a conviction that I am a lunatic. I may mention that my companion and I were both disappointed lovers. The love passion, you are aware, absorbs some natures far more completely than it does others. We were both so imaginative as to fancy that life had in it thereafter, little worth living for, and we were consequently in a mood to devote ourselves to something which we deemed a high purpose. Therefore it was that we mutually agreed to give our lives and small fortunes to the demonstration of our theories. We compiled all the statistics of balloon ascensions on this continent, chiefly to determine the exact bearing of the polar air currents toward the northeast, that we might select the proper starting-point from which we would most likely be carried over the central portion of the Arctic Ocean where it joins the Atlantic. We were both sensitive, on the score of being called monomaniacs, and consequently selected a point in the wild portion of Franklin County, New York, about twenty miles north of the fortieth parallel, where we could make our preparations unobserved. There we made many experiments during the year 1860. I remember there was talk of war at the time. Much thought was bestowed upon the construction of our balloon, with a view to insuring lightness and durability. To that end we selected tempered steel wire, and constructed the framework throughout, on the mechanical principles applied in the building of trestle bridges; so that when completed the basket and entire framework of a balloon, forty feet in diameter, could be easily lifted by one of us. It was at the same time exceedingly strong and elastic. For a dome we decided upon thin, soft sheet brass, for the reason that it was at the same time lighter and more durable than any fabric, and in case of necessity would answer the purpose of a parachute. Our commodious basket was lined with the same material, and provided with an adjustable roof, against the possibility that the temperature or storms might require inclosure and a resort to the generation of artificial heat, for which we made preparation. From the central hoop downward the gas-bag was made of closely woven silk saturated with india- rubber. To raise and depress our air-ship was a most important consideration, since upon our ability to do that at will depended largely our hopes of success. Accordingly, out of the steel wire, with infinite pains and considerable ingenuity, we constructed a large wheel, immediately under the bottom of the basket. It was provided with fans set at an angle of forty-five degrees, which we were able, by an attached man-power, to turn in either direction with great velocity. Its lifting and depressing power gave us full command of our ship in that particular. The dome and gas-bag were covered with silk netting saturated also with india- rubber; and you will be astonished to learn that its weight was but a little over three hundred pounds, with a lifting power, when inflated, of over a ton. We stored our car with condensed food sufficient to last us for months if we were sparing, with alcohol, water and fur clothing, nautical instruments and a considerable quantity of zinc and sulphuric acid, in the event it might become necessary to add to our supply of gas. We took repeating rifles and a supply of ammunition—in fact stocked ourselves to the limit of the full carrying power of our balloon. It was on the eighteenth of June, when the sun, as you know, is near its extreme northern declension, and it is summer at the North Pole, that we found ourselves ready to start. Casting off the guy-ropes of our ship, we sat for some time in the car, which we had fastened to the earth by four ropes running through iron rings in the ground, and returning to our hands. At that moment only did a doubt of the correctness of our theories ever force itself upon my mind. My companion afterward acknowledged to the same feeling. Neither spoke a word, but we looked about us upon the little patch within our view of mother earth in the glory of summer clothing, as something we might never behold again. The balloon swayed back and forth and tugged at the basket, restless and eager to mount into the air and be free. We had the satisfaction of seeing that not a line or wire of our elastic contrivance threatened to give way, and it was with renewed courage that I gave the word to let go. We shot instantly into the air, moved toward the southwest for a few moments, and then, at an elevation of 15,000 feet, suddenly turned to the northeast in the upper current on which we had counted. The probable rate at which we were going we estimated at somewhat more than fifty miles an hour. We reckoned that, having started at seven o'clock, we would be by seven at night over southern Labrador or northern Newfoundland, where the days would be about sixteen hours long, which would give us over four hours more light, and that the space gained would reduce the night before us to about five hours. After that we would enter the continuous day of the Arctic regions. I remember that, while I experienced no dread of tumbling from our lofty height, the silence was terribly oppressive; yet neither of us for some time could command our tongues to break it. It was the longest day that either of us had ever spent, and at nine o'clock we had passed over what we assured ourselves was the southern coast of Greenland. Then the sun suddenly dropped out of sight, and we were over a vast expanse of water, in darkness. Our eyes were instantly fixed upon that phenomenon of the northern sky, for which our scientists have been unable to account further than to declare it to be an effect of electricity—the Aurora Borealis. I had never before looked upon an effect of light so beautiful. It spanned the firmament over the Northern Pole in a perfect arc, from which shot upward sheets of variegated light. So soft was the light and so delicate its tints, we seemed to know that the electric element was not exerting any destructive energy. It filled us with no dread, in view of the fact that we were hastening at the rate of fifty-six miles an hour towards it. Our theories and experiments had led us to the conclusion that its influence would not prove hurtful, but that, on the contrary, it was a harmless source of both heat and light. We reckoned our latitude and longitude every hour, and discovered that we were gradually veering to a more northerly course. We never thought of sleep during the short night of about five hours, but eagerly watched for the morning, that we might be able to see what was beneath us. When the sun arose, never to set again for us during our journey, we had passed the fifty-sixth parallel and were skirting what we judged to be the eastern coast of Iceland, where the denizens were enjoying their short summer. A few hours later we had crossed the Arctic circle. Thirty-six hours thereafter we had passed the frozen limit, and also the northern shore of the Arctic Ocean, when it seemed as if some omnipotent magician had struck the earth with his wand and suddenly transformed it before our eyes. We had counted on no such abrupt transition into what was evidently a climate of well-nigh tropical warmth. Arctic explorers had killed fowls flying southward with grain in their crops: we were over their feeding-grounds. Our free needle had for hours stood at continually changing angles, and the other twirled and vibrated, indicating no direction. Contending forces were shifting it first west then east of our course, which we supposed was north. From this on, sir, I must relate a tale of wonders that may strain any faith you may have in my honesty, assuming that I am sane.

"I have no knowledge," I said, "on which I could base a refutal of your story thus far."

"Our needle continued its uncertain motions for about two hours more of our journey. We passed over stretches of dense forests, of whose character we could not judge at our distance, and over plains, lakes, and streams. One thing astonished us. The forests and hills, if there were hills, cast no shadows. We had been so engaged with the earth beneath that we had failed to notice the sky above us. When I did so, it was with an exclamation of wonder and admiration. We were in an atmosphere so luminous that the whole firmament was the color of pale gold. I will not theorize on the phenomenon, but simply refer you to the flame that you have seen arched over the vortex of a cyclone. Here it was, not condensed into destructive force, but grand in its proportions, mild and beneficent, as the sun's rays, a source of light and heat. The circle of its influence marked the limit of the Arctic region, and we judged that it spanned a diameter of about seven hundred miles. In this strange atmosphere we were highly electrified, and filled with a lightness of spirit and increased energy of both mind and body, such as we had never experienced in our lives before. This luminous atmosphere took the form of an arc as we advanced, and our needle said it was to the eastward of us, a fact that completely confused our ideas of direction. We judged, from the action of our needle, that we had long passed the boundary of terrestrial latitude on the exterior; and that since, for a long time, its uncertain motions had ceased and its poles become steady, that we were far within the interior of the earth. We were antipodes, we believed, to what we had been twelve hours before, and resolved to descend. For twelve hours the sun had not been visible; yet every object revealed itself in a strong, mellow light. We began to work our fan vigorously, and slowly pull ourselves to the earth. Not knowing what we might find on the surface, or how soon it might be necessary to rise again, we resolved not to waste our gas, if we could land without doing so. We managed, by laborious effort, to get near enough the ground for our grappling-hooks to drag, one of which fortunately caught firmly in a small cluster of bushes, that here and there dotted the plain we had selected for our landing-place. The air being still, the balloon soon came to an equipoise after its sudden check; and when we were certain that the hook had firmly caught, Harding, who had often astonished me with his gymnastic feats, descended the line hand over hand, and was the first to set foot on the new world. He made fast the hook that dangled from the other side, and by means of a windlass, to which the ropes were attached, I easily brought our air-ship to anchor. It was the work of a few moments to fasten our guy-ropes and run up a light tent-cloth about our basket, when we felt that we were domiciled, and with leisure to look about us."

WITHIN A NEW WORLD—OUR FIRST ACQUAINTANCE—A LAND WITHOUT A HORIZON, AND WHERE LIGHT CAST NO SHADOWS—A NEW RACE—EXPECT TO ASTONISH THE NATIVES—THEY ASTONISH US.

I TOOK out my watch, to note the time, and found it dead.

Every detached piece of steel in it had become a magnet. Harding

was the first to comprehend what was the matter with it, and was

light enough of heart to laugh at what I considered a calamity.

He had taken the precaution to have one made entirely of nickel,

and I had laughed at his precaution. His watch showed that three

days and ten hours had elapsed since we had let go our moorings

in New York State. Certainly no journey of, as we reckoned it,

4,800 miles had ever been made in this world before, with like

ease, safety, and rapidity.

"Now, what think you," asked Harding; "are we in an uninhabited wilderness?"

"It is by no means likely," I replied, "with such conditions as seem to prevail here for sustaining life." I was sweeping the landscape with my glass when I spoke. Before I removed it from my eye I had occasion to say: "It decidedly is inhabited. Look off yonder, near the verge of this plain, and say what you think that is."

We looked long and anxiously at what, we made no question, was a long procession of human beings, some of whom at the front of the line were mounted upon large, heavy animals. I had seen, before we descended, what I fancied were droves of elephants, but could not assure myself of their real character. Now I had no doubt of it; but the humans, if such they were, who rode the animals and followed on foot, filled us with wonder. Whether it was an effect of the light or not we could not tell; but they all had a golden sheen, and all appeared exactly alike, except three or four near the head of the procession, who were mounted. These, we could see, were clothed in flowing drapery that shone with metallic lustre, dazzling the sight; while the others reflected, as I said, a soft golden sheen.

"They are human, or they wouldn't be riding elephants," said Harding.

It was useless for us to speculate upon the object of the procession, save to ascertain if it were of a warlike character. We were glad to be able to assure ourselves that they carried no warlike weapons, and were probably of a peaceable race.

"It is not likely that our balloon, even at this distance, will escape the attention of all that crowd. We may as well make up our minds that we are discovered, and take our measures accordingly," said Harding.

"As we know nothing about these people, if they are people, I have no idea of what measures ought to be taken," I replied.

"It is always best to be prepared for war. Let us look to our guns and stay by our balloon. If they should want to sacrifice or eat us, it is our only salvation."

Since sooner or later we must make an acquaintance with the natives, if we would learn anything of the country, we concluded to prepare, as best we could, for any warlike measures that might be taken against us, and while awaiting events, to eat and sleep in turn.

"I say," said Harding, when our meal had been prepared, "is this breakfast or supper? It is now eight o'clock."

It required a calculation to determine that it was supper. The most unaccountable thing to us was our buoyancy of spirits, that disposed us to continually regard our wonderful situation in a humorous light. Nothing seemed too grave to be made the subject of a joke.

"I wonder if it is everlasting day here, and if it is, how we will ever get used to it?" said Harding as he stretched himself out on the floor of the basket, preparatory to taking his turn at sleeping.

"I make no doubt that this is a land of everlasting day, and we may prepare ourselves to observe some strange results of continued light," I answered, as rifle in hand I took a position as sentinel, from which I could command the entire plain with my glass. It was covered by a dense verdure of tall, broad-bladed grass, intermingled with a great variety of flowering plants, in whose blossoms yellow and white colors predominated. Although both grasses and flowers bore a general resemblance to those of our temperate regions, yet with the exact forms of none of them was I familiar. The green tint, too, of the landscape was less deep in color, and all vegetation had a changed aspect. I plucked the leaves of several varieties of shrubs and vines about me, and observed that the upper and under sides differed little in appearance, and that all were tender, giving the impression of rapid growth and decay. Without disturbing Harding, who had sunk into profound slumber, I obtained our microscope and was enabled to discern, on both sides of the leaves, the minute pores, through which they continually, as I did not doubt, exhaled oxygen. I concluded that the vegetation, unlike ours, took no rest. I was thus enabled to account for my exhilaration. The air was highly charged with oxygen near the surface of the earth. I turned my field-glass toward the nearest forest at the southwest, if our needle told the truth, and saw among the other growth here and there a mammoth trunk, which from its general form immediately reminded me of those relics of a former period found in California. A close examination later convinced me—so far as I could judge of the California product, which I had never seen—that they were the same. As I swept with my glass the further verge of the plain to the north, I saw for the first time a roadway, along which the strange procession had moved. So intent was I upon examining the immediate locality that I had not lifted my glass to the horizon. "Great Jupiter!" I exclaimed when I had done so. Above the nearest forest the earth rose higher and higher toward the firmament. It seemed to be a vast, stupendous mountain, whose summit could not be reached by human vision, aided by the glass. I turned on my heel, and all about me it was the same. There was no horizon! The mounting earth, growing more golden in the distance, mixed with the firmament. I thought of ourselves as two insects in the bottom of a huge golden-bowl. A moment's reflection, however, explained the phenomenon, and I wanted no further evidence that we were on the inside of the earth. Through a vista in the timber I could see a large body of water to the south; but before the limit of vision was reached, its colors blended with those of the sky so that I could not distinguish between them. The water seemed, like ourselves, to sleep in a great hollow. Looking farther to the eastward the effect was different. It was wonderful! My admiration found expression in involuntary utterance. "Grand! Beautiful! I saw the earth beyond the water; it was in the sky, a mountainside of green and gold! A fairy landscape, floating upon air or water, which I could not tell! In comparison with that without, this world within," I said, "is paradise!" I felt at that moment quite content to spend my life in it, and fell into a pleasant reverie, from which I was startled by a noise in the tall grass some fifty yards away. It was an elephant, which had advanced beyond the bushes by which it had been entirely concealed from view. You may be sure I beheld the huge beast with more alarm than wonder; yet I did not fail to note the fact that it was covered with hair, and to associate it with those remains which the Siberian snows have preserved for uncounted ages. The first object to attract its attention was the balloon, and the immediate elevation of its trunk, tail, and ears proclaimed the wonder which that unfamiliar object, with its brazen dome, inspired. I called out to Harding in alarm, lest the brute should make an attack upon our air-ship, tear it from its moorings, and settle at once the question whether we would ever return to the exterior of the planet. He jumped from the tent instantly, rifle in hand, and would at once have begun to pour bullets into the as yet unoffending animal, had I not interposed an objection.

"Wait, Harding," I said; "it hasn't made up its mind to attack us; wait!"

We appeared to be a new subject of wonder to it, and it regarded us intently for some time, apparently without alarm. Having seen an enraged elephant on one occasion, I was somewhat conversant with elephantine expression, sufficiently so at least to know that the one before us was not disposed to warlike operations. I certainly expected, however, that he would either fight or run away. He did neither. The longer he looked at us and heard us talk, the less wonder he manifested, and at length alarmed us by approaching us with quiet deliberation, plucking grass and eating it as he advanced.

"Confound it!" said Harding, "it's coming. We had better fire before it gets too close."

"No, no," I replied; "that elephant has seen animals like us before and takes us for friends, as sure as you live."

"Well, but I don't want to make his acquaintance."

"Hold on! Don't fire," I said. "I'll go out and meet him and see if his intentions are peaceable first."

Accordingly, in the grass, up to my waist, I went toward him. He seemed to take my approach as a matter of course. I had already concluded, from what I had observed in the strange procession, that the elephant was domesticated, and recognized in us some resemblance to his master or to some creature from whom he had received favors. Of this I became assured, when, on attaining a nearer proximity to each other, he paused and regarded me with apparent distrust, as though he had discovered a difference. There was no sign of ferocity about the creature's movements, and I became anxious to learn all I could, even from an elephant, of the new world. I remembered that they were fond of sugar on the outside of the globe, and that I had, but a short time before at supper, dropped a few pieces into my pocket. I spoke to the animal, calling him by the name "Sampson," which I had heard one in a menagerie called by, and at the same time holding out a piece of sugar. I was astonished beyond expression when he came forward in seeming response to my call, and held out his trunk to take the proffered sugar. I gave it to him and he ate it with an evident relish. It was a happy introduction.

"Harding," I said, "this elephant is as gentle as an old cow. Bring me some more sugar; he likes it."

"Ask him where he came from and who owns him," jocosely replied Harding as he entered the tent to get the sugar.

To a domesticated animal one is disposed to talk, and I said:

"Sampson, you hear him. Can't you answer the gentleman?"

I stepped to his side with confidence and patted his shoulder at some distance above my head. Now, sir, I wish to say that in the atmosphere which I now breathe with so much difficulty, I could not then have raised my courage to the point of placing myself within the power of the most woe-begone elephant that I ever saw in a travelling circus; but both myself and companion felt quite as reckless of consequences as men who are what is called "half-seas over." We were drunk in the—or, rather, on the new atmosphere. The brute was covered with an inch-long coat of mouse-colored hair, and was certainly a decided improvement in appearance upon his kind on the exterior of the globe. As I stood thus upon his left side, I saw tied to his fore leg and dragging behind a thick rope of twisted fibre much resembling hemp. I saw, too, that his long tusks were rendered harmless by wooden caps on each point, and a thick netting woven from one to the other for nearly their whole length. On this was placed securely a soft cushion covered with a fabric woven of fine, yellowish hair. I ventured to place my hand upon it, and found it to be glossy as silk, but with a hard, durable surface.

I informed Harding when he had reached me with the sugar that the old fellow carried a cushioned seat with him.

"Perhaps he's a native porter looking for a job," he suggested.

"We might learn how to manage him," I said. "You win his favor, too, with some sugar, while I get one of our iron stakes and tether him. He responds to the name Sampson, but how he happens to recognize that name is a mystery to me."

The delicious morsels of sugar made the monster in love with Harding also before I returned, and, while he engaged the animal's attention, having forgotten to fetch a hammer, I looked about for a stone with which to drive in the stake. I found several scattered about among the grass, and selected one that I considered about the right size, but in attempting to lift it, found it by far too heavy for my purpose. It was well-nigh pure iron. I found a smaller one, and, holding it above the stake slightly inserted in the soil, the latter jumped upward to my improvised hammer and stuck fast. I had selected a loadstone that possessed the attractive power of a large magnet. I was forced to lay down the hammer and slide the stake off. The negative end of the stone served me better. After I had, as I supposed, secured the elephant, I examined other stones and found them all of the same character.

"Beyond question," said Harding, "this is the head-centre for the manufacture of loadstones."

Long afterward I listened to a legendary story regarding these stones that I will not waste time upon now.

We tethered Sampson about thirty yards from our air-ship, and, taking our camp-stools, sat down in front of it on the trampled grass and discussed the situation. We were thus engaged when we were startled by a peculiar voice, pitched upon a high key, calling "Te, kai! San-son!" It was the voice of one as yet hidden from us by the clump of bushes, and from whom both we and the balloon had thus far, as we supposed, been concealed. By a common impulse we slid from our stools, and crouched to get a view unseen of this first denizen of the new world, on whom, near enough to be clearly seen, our eyes had been destined to fall. "Te-kai! Heh, heh, heh!" laughed the voice. It was clear and bell-like. It seemed to utter its peculiar call, "Te-kai! San- son," very near to us, and to follow it with a joyous burst of laughter, "Heh, heh, heh!" Yet, when we first heard the voice, the creature must have been not less than a quarter of a mile away, since we lay fully ten minutes in hiding while it approached. It struck me for the first time that in that dense atmosphere sound must travel a long way, and possibly have characteristics to which our ears had not been accustomed. I remembered that Harding's voice, when he had called out to me at a distance, seemed to have changed its quality. We were peeping over the top of the grass, when the owner of the voice at length came into view, and saw at once that it was one of those creatures with a golden sheen we had observed in the distant procession. Its attention was wholly absorbed at first by the elephant, whose name it now appeared I had so fortuitously approximated, and I had time to examine our visitor through the glass. I saw a face whose complexion, by contrast, would render the fairest American girl I ever saw quite unattractive in that regard. It was a face of such wonderful transparency and freshness, as surpassed all my former conceptions; and it was one that, to use a trite comparison, might have answered the purpose of a classic model. I perceived that it was the face of a man, from the long, glossy beard that hung from his chin. Both it and the long, curled hair on his head were of a golden brown in color and reflected the light as he moved. So much as I could see of his form indicated that he had been perfectly turned out of some one of our varied human moulds, and that, if his hair had been confined to his head, he certainly would have passed with me for some superior human. But his body was covered thick with the same lustrous hair, not less, I should judge, than an inch in length generally, and much longer upon his breast. His hands, however, like his face, were free from this hirsute covering. I caught glimpses through the grass of some white, textile fabric about his loins, by which alone he had seemingly supplemented Nature's provision. Sampson, or San-son, as it seemed the animal's name was, knew our visitor, and, pricking up his ears at the very first call, elevated his head and uttered his peculiar roar of recognition. Our visitor looked about him and saw our air-ship, some fifty feet in height, towering at least thirty feet above the bushes. My glass was on his face when it first caught his eye, and I expected to witness an exhibition of terror, but I was disappointed. It was one only of wonder and astonishment, so that it was my turn to wonder. Instead of running away, after regarding it in silence for a few moments, he burst out into his peculiar laugh, "Heh, heh, heh," and approached it with the light, springing movement of an expert ballet-dancer, bounding so high, that I could see his feet were protected by a pair of sandals, at the material and construction of which I could only guess. He was within but a few yards of us, when we arose like two apparitions before him from our concealment. He stopped suddenly with an exclamation, but, to our astonishment again, not of fear but wonder. He looked at our faces, and his eyes, wandering over our persons, came back to our faces again. I had time to note that his eyes were violet in color. The expression on his face was so odd, that I could not help answering his look with a smile. It seemed to be what he was waiting for, as he instantly began to laugh heartily, and, spreading his hands over his face, bent forward until he nearly touched the earth with his long hair.

"Great Scott, it's funny!" exclaimed Harding, bursting out into an uproarious fit of laughter, in which the new visitor and myself joined most heartily. Perhaps Harding did, but I am sure neither the native nor I knew just what we were laughing at. It was certainly our best policy to make all the friends we could in our new world, and I stepped forward to make advances. The amiable creature bent to the earth, and remained in that posture until I touched him on the shoulder. Then he arose, and I held out to him the same peace-offering I had found most effective with the elephant, a piece of sugar. He took it, and looked me steadily in the eye. He was evidently at a loss to know what to do with it. The elephant had taken it with no uncertainty as to its use. I called attention to a similar piece, which I put in my own mouth. He comprehended instantly, and popping it into his mouth, began laughing again.

"Harding," I said, "I never saw before such an exhibition of fearless confidence on the part of any human."

"That is assuming a point," he replied. "Is it human?"

"There can be no doubt about that," I answered, "a human who does not seem to know what fear is."

"Then do you suppose he regards us as superior or inferior beings?"

"I am sure I don't know whether his prostration was intended for adoration or for a mere customary greeting."

"Well, we ought to find out whether we are expected to play the roles of deities or commonplace visitors," he rejoined.

"It will be best to preserve a grave dignity at any rate, and try and impress him," I said.

"Yes, but it's too deuced funny," answered Harding.

"True, but as a mere pretence, it will be a sort of comedy," I argued. The fact is, we realized that gravity of deportment was well-nigh impossible in that climate. It was a strange feeling. Waiting respectfully until we had finished our colloquy, our visitor began to pantomime his wonder at our air-ship. There was certainly nothing better to overawe him with, and we accordingly removed our tent-cloth from about the basket, untied the guy- ropes, lengthened the anchor-ropes, and with the windlass, which you remember was attached to the grappling lines, allowed it to ascend about forty feet, with Harding in it. Wrapped in speechless wonder, the hairy native looked, while we explained by pantomime, that we had come through the clouds from the far east, our needle told us now. If he had a natural religion, I felt sure that the home of his gods must be in the direction of the great centre of their light, that electric dome that crowned the mouth of the great helix, 700 miles, as we reckoned, in diameter. The native fell prostrate before this wonder, and there was no doubt that we were regarded by him as superior beings.

"Harding," I said, "with the balloon we must impress the natives generally. Suppose we place the elephant under the basket and fasten the balloon to him with the anchor lines, and prospect the country in that way?"

The suggestion accorded with his opinion, and I explained to the native what we wanted to use San-son for by a tedious process of depicting the whole procedure. He seemed at first to get the idea that we wanted to take San-son away with us in the clouds. But he was quick to understand my intention when I desired to know where he lived and explained that he was to lead the elephant. San-son obeyed the native like a dog, and stood under the basket with perfect indifference until I had wrapped the anchor lines about him and padded them with blankets, so that they would not render him uncomfortable. Then I loosened the grappling lines, and by aid of one of them clambered into the basket with Harding. Where the native supposed we wished to go we did not know, and therefore we had no idea, of course, of where he would take us. We were in that frame of mind, as I have intimated, that we didn't care. San-son was somewhat puzzled by the huge bulk above him, which, instead of pressing down upon him, helped to carry his weighty body and render, him light of foot. But he raised no objection to the arrangement, and we started toward the southwest. We had not proceeded far, however, before we realized that if we expected to travel in that manner with any comfort, it would be necessary to stay the balloon against the resistance of the air, since it careened backwards at such an angle as threatened to toss us, and all its contents, out of the basket. We were forced to stop midway of the plain and consider ways and means. Fortunately, we had taken the precaution to bring with us some narrow wire trestles, one and one-half inches wide, which we had stowed by bending them like hoops around the inside of the basket. They were about fourteen feet in length, and when released sprang into their normal straight condition. With fine, soft wire we bound one of these at right angles to the other in the centre, and thus made a long, light, rigid pole. Having thus constructed two, we bound one on each side firmly to San-son's rope girths, so that they projected beyond his head some eight feet. To their ends the guy ropes were fastened, and such a purchase obtained on the balloon as kept it comparatively steady. A balloon forty feet in diameter, towering sixty feet above the back of an elephant, would have produced a sensation anywhere, and we did not doubt that these hairy natives would be impressed into reverential awe of us. Tet-tse, the name of our first acquaintance, as it was afterward pronounced for me, doubtless felt that he was in charge of superior beings, and watched our every movement with great concern, lest he should do anything wrong. Before we had reached the vicinity of the forest, some two miles as I judged from our starting-point, we had become quite proficient in sign language, and I had discovered Tet-tse to be a very intelligent animal, who at least understood us quite as well as we did him. I had noticed as we proceeded that flocks of water fowl, flying between their feeding grounds and the large body of water I had seen, would almost always veer from their course and come fearlessly near us to see the moving wonder, and I said to Harding that nothing we had thus far seen, with life, appeared to have any sense of physical fear.

"Now, how do you account for that, Harding?" I inquired.

"Don't be putting conundrums that you know I can't answer," he replied. "We haven't discharged a gun since we started. Suppose we try the effect of some shots, directly on the fowl and indirectly on Tet-tse?"

"No," I said, after some reflection. "We should be merely wantonly killing some fowl, while the more serious result might follow, of turning his confidence in us to distrust."

"I reckon you are right," was his answer. "Our guns had better be reserved in case we need a new wonder to serve us."

It was long afterward that the occasion came for discharging our weapons, and then their deadly missiles made a holocaust of human beings. That Tet-tse was leading us toward some centre of population seemed probable, from the fact that a short distance from the timber we struck a travelled thoroughfare, which shortly led us to where five roads, branching from a common avenue that ended at the forest edge, took their several courses through the large plain on which we had hitherto been.

"It is very evident," I said to Harding, "that these strange people use no wheeled vehicles, and that elephants are their beasts of burden."

"And the tamed elephants as well as the roads proclaim that they are not savages," was his supplementary conclusion.

From what was evidently an elephant pasturage, the land, from the forest line, gradually ascended to a higher level, and the rock formation of that portion of the interior earth began to reveal itself. From occasional glimpses of ledges, obtained through the glass as we moved, I could perceive that it was principally granite formation and quartz. The avenue was nearly 100 feet wide, and the grandest we had ever beheld. It was not paved, but ran over the native soil, which had been made smooth and freed from all obstructions. Even the ordinary growth, which, though not the same, yet resembled somewhat our beeches, maples, oaks, and elms, were not less than 150 feet in height as an average, while the mightier forest monarchs rose far above them, to the clouds it seemed, as we beheld their huge arms interlaced above us 250 feet in the air. The variety of growth astonished us. There seemed to be no life-and-death struggle between the different species, in order to reach their element of life, the sun. There was no sun, and the light which enabled them to manufacture nourishment continuously came from everywhere. There were no shadows, so perfectly was light reflected in that luminous atmosphere, unless the light was shut out from all sides save one. Since we saw several kinds hanging from the limbs of the smaller trees, it was evident that the fruits ripened as perfectly in the forest as on the plain.

"As we don't know how far we will go to-day," said Harding, taking out his watch, "I suppose there is no use consulting my timepiece. But it is past midnight and late bedtime. There isn't much satisfaction in carrying a watch in this country, is there?" he concluded as he returned it to his pocket.

"I am curious to know how these people measure time," I rejoined. "I have observed nothing yet that would enable them to form a basis for its divisions."

"I wish this creature could talk English, so that I could find out if he knows how old he is. That would settle the question."

"It seems to me that time is hardly worth measuring in this country," I said reflectively. "Nature appears to provide for every demand of animal life. Except these avenues and roads that were probably made ages ago, I see neither any evidence of labor nor demand for it."

Just then, whether time was of any value or not, we had none left to bestow upon that line of thought. We had advanced along the avenue about 200 yards, when suddenly the forest on both sides of us swarmed with natives. Their appearance, so abruptly, was magical. They sprang, apparently, out of the ground. We had expected to surprise the natives; they had surprised us. They were all hairy creatures, like Tet-tse, and of both sexes. Certainly the ancients of Europe did not get their conception of satyrs from such as these. These people were perfect in form and beautiful. Even at that moment of surprise I conceived of one of the females dressed in the manner of a European, and I knew she would outrival in beauty of face and movement the most beautiful of our women. As they appeared here, there, and everywhere, they severally almost touched the earth with their foreheads, as though each were a trained athlete, gazed for a moment—whether in wonder or admiration, we could not tell—and immediately advanced toward the avenue. Each carried a garland of flowers and leaves, and from the lips of each came the most musical greeting to which I had ever listened. It sounded like "Tat-o-lin-kee," and the peculiar quality suggested the notes of the bobolink. These calls were mingled with continuous laughter. Such a potent exhibition of joyous emotion I never witnessed, and doubtless never will again, unless it may be somewhere within the great unknown.

"Harding!" I exclaimed in amazement, "can you account for this? Here is concert of action that shows we have been expected for some time."

My companion could not resist the inclination to treat everything lightly, and replied:

"Oh, it didn't take them long to make their toilets. But they have been looking for us, and that's a puzzle."

Ahead of us, in the avenue, assembled a company of fifty, distinguished from the rest by metallic zones about their waists, short skirts of some glossy fabric, and metallic bracelets on their wrists and arms. They arranged themselves five abreast, and each of the ten lines was provided with a different musical instrument from the others. I could not see the forms of all, but noticed that the last line carried cymbals. Others had string instruments, constructed on the same principle as those in use by us; while there was a variety of wind instruments, some of metal, but chiefly constructed of reeds. They were the cymbals, bracelets, and zones that fixed my attention; since through the glass I made them out to be gold. This company of musicians, all females, marched, or rather executed a continuous dance before us, as we moved, assuming the most graceful attitudes, and timing the music with their motions. The rest, waiting until we had passed, fell into procession behind us. Our march extended along this that appeared to be a main avenue, from which others branched off here and there, about four miles; and I could see that we neared the borders of the body of water, of which I have spoken. Back of us, so far as we could see, the procession followed, and we estimated that there were not less than 5,000 natives in line. Yet still, to the right and left of us, in the forest, they appeared, ready to increase its length. Harding and I had ceased to speculate in regard to what it all meant. The demonstration appeared to be in our honor, and yet the disagreeable thought would intrude itself, that perhaps we were intended for sacrifice. The fear was not moderated by the reflection that, if our balloon were cut loose, it could not rise through the tree tops. On the other hand, it was assuring to note that among the large concourse of natives we had not noticed one warlike implement. I had observed, as we proceeded, that large sections of the forest, in the distance, were covered with a growth somewhat resembling corn. This was, as I afterward learned, a cereal altogether different from any that the outer world produces. It has a stalk somewhat resembling our corn, but the grain is about eight times as large as a kernel of wheat, and grows like corn on a globular cob. I correctly concluded, at the time, from the regularity of its growth, that it was cultivated. I noticed also that the fruit-bearing trees and vines with which the forest abounded were cultivated, notwithstanding none of the territory was inclosed.

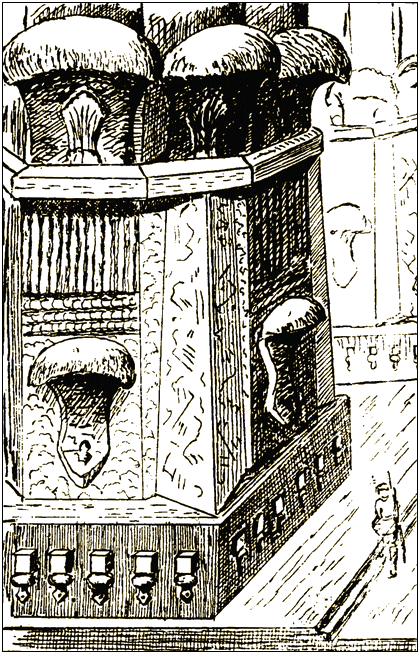

I reached the conclusion that notwithstanding nature's liberality these hairy people did considerable for themselves. On the surface of the ground there was no sign of a habitation, and we wondered from whence they had all appeared so suddenly. The avenue we travelled abruptly turned to the right, followed the line of the lake shore for about 100 yards, and made directly for the face of a cliff.

DO WE DREAM?—KAYETE-UT-SE-ZANE, QUEEN OF THE LIGHT—SOVEREIGN OF THE TOLTUS—HER WONDERFUL PALACE—ART AND SCIENCE SURROUND US WITH MYSTERIES—IN LOVE.

I HAD but barely time to note that the cliff was for the

most part an exposed surface of glittering quartz, shaped either

by nature or art into a castellated form, with many indentures on

its surface resembling windows and doors, when its whole front

became instantly transformed. There stepped from a hundred

openings and niches on its face as many exquisite forms of female

loveliness. They stood like statues, clothed in richly-colored

fabrics aglow with burnished gold and diamonds. We would have

been more than human if, under any circumstances of time or

place, we could refrain from giving expression to our admiration

of such an entrancing picture. Involuntarily following our own

customs we removed our hats and bent low before the central

figure, in whose face was combined sovereign dignity and

saintlike gentleness. She seemed to be one from some ethereal

sphere who had stopped for a moment to rest and must shortly fly

away. On her person was lavished incalculable wealth. I venture

to say that a single article of her apparel that flowed about her

like a Greek himation, in New York City would have purchased all

the property real and personal of that entire State. It was

covered with disks of gold, alternating with diamonds, not one of

which was less than two-thirds of an inch in diameter, and worth

in the markets of this outer world from half a million upward.

Beneath this outer robe, whose color was deep crimson, was a

plain skirt of golden tissue. On her feet were gemmed sandals,

and on her head a golden circlet in the form of a serpent,

evidently her special insignia of authority. There were

suggestions of both Europe and the East, and especially of

antiquity, that flashing through my mind on the instant excited

my curiosity as well as wonder. She regarded us for a moment

intently, when San-son had brought us within a few yards of her

and come to a halt, and then her features relaxed into an

assuring smile. I am sure there was an expression of worship on

my face when my eyes met hers. Certainly she was worshipped by

all the hairy race; for every one of the vast multitude was

bending in reverential awe. Had I at all been inclined to be

superstitious, I might have been disposed to regard her as a

sorceress, who had bewitched our senses with an unreal vision

that was too beautiful to last. I say she smiled upon us, and

immediately, in a voice of exquisite sweetness, that was peculiar

to the race, addressed us in what I at first supposed to be a

tongue entirely unknown to me. She uttered but a couple of

sentences when I thought I recognized one or two words. For some

years my father had employed a Norwegian on the farm, and from

him I had acquired a fair knowledge of that language. They were

words in that tongue that I thought I recognized, and I

accordingly addressed her in return, very slowly. Immediately she

clapped her hands in almost childlike delight, and repeated after

me a few words, pointing the while to the objects they signified,

to which I bowed, by way of affirming her understanding of them.

The language in which she addressed me may have been spoken in

Norway 1,000 or 2,000 years ago,—I do not know, for

certainly some of the words were the same; while, if it were so,

it had undergone such changes as made them, I thought, well-nigh

distinct tongues. She seemed delighted, however, and made a sign

to the hairy people, at which the vast crowd broke forth into a

joyous shout, followed by a chant, in which the thousands of

voices kept perfect time. It was taken up by others far down the

avenue, and when it ceased near us, it continued to float back to

us from a mile away. Those who appeared about her, on the face of

the cliff, were doubtless her attendants; insomuch as they came

and went at her bidding, and began executing a multitude of

orders, as it seemed, altogether. What they were became apparent

the next moment, when there moved out from the face of the wall

beneath her feet a series of polished steps. Instantly the

beautiful human statues disappeared from their several niches,

and the majestic mistress stood alone. But only for a moment,

when the cliff immediately behind her opened. A thin quartz wall

slid back from right and left, revealing a portal, grand in its

dimensions and magnificent beyond description. It was not less

than fifty feet in width and sixty feet in height, and resembled

no form of architecture of which I had any knowledge. It was not

constructed on geometrical lines at all. For pillars, arches,

capitals, and bases were substituted forms of animal life. On

either side, as main supports, if such were needed in a portal

cut out of the solid cliff, stood an elephant artistically carved

and polished, staring at us out of large garnet eyes. Around them

coiled monster reptiles whose bodies, in successive rings, rose

to the arch, where they were locked in a deadly embrace. Their

bodies were covered with alternate scales of gold and crystal,

their gemmed eyes darted light and their garnet tongues, in the

shifting light, seemed to move. The elephants were adorned with

golden collars and girths, and on their backs were golden apes,

as I supposed, standing on their feet and grinning at the

contending reptiles. This was the first picture in an irregular

setting of dazzling brilliancy, a vast mass of polished crystals,

which threw back the light almost as effectively as so many

diamonds mingled with burnished nuggets of gold. Beyond this, in

the interior, I had time to note where two animals resembling

camelopards in their general contour, presented a side view.

Between their arched necks and forelegs formed one passage-way,

and between their fore and hind legs, on either side, two others.

By a succession of such designs the way appeared to lead into the

interior of the rock. An instant after the revelation of the

portal, a number of those whom we had seen in the niches appeared

about their mistress, and completed a picture such as could only

find appropriate setting in some fairy story. I certainly had

never expected to look upon such a reality. The Queen, for such

we knew she must be, spoke in her strange tongue to Tet-tse, who

in turn addressed San-son, and the animal immediately got upon

his knees. An attendant placed at his side some lightly-

constructed steps on which we understood, of course, that we were

expected to descend. With a smile of ineffable sweetness, the

Queen herself stepped forward and extended a hand to each as we

alighted. Harding, a most courteous fellow always, bent low

before her and received a kiss upon his forehead. His polite

manner had evidently met the requirements of a custom. She bent

the fairest head we had ever seen, and he returned the greeting.

In turn I received the same welcome, and we ascended the steps on

either side of her majesty. Standing between us she harangued for

a few moments the crowd of natives, who responded in shouts of

joy. Then she waved her hand, and they instantly began to

disperse. She motioned toward San-son, who had risen to his feet,

and began talking in that tongue, some words of which I had

recognized. What with her intelligent pantomime and a word or two

that conveyed a meaning, I understood that she was somewhat at a

loss what to do with our air-ship. Harding also understood and

remarked:

"I suppose we had better let out the gas and make up our minds to stay awhile, if you are sure we are not bewitched, and that this is real."

"Bewitched or not, it is very pleasant, and I feel like enjoying it as long as it lasts," I replied.

Meanwhile she had been talking to Tet-tse, who had, as I supposed from his gestures, informed her of the upward tendencies of our ship, and I jumped at the conclusion, when she addressed me again, that she desired to see it rise. Accordingly, with many bows and smiles, I pantomimed our desire to gratify her, and proceeded to release San-son, and repeat the ascension to the length of our anchor-lines that Tet-tse had witnessed. She expressed no astonishment whatever, although her attendants bowed in adoration. This completed our introduction to Kayete-ut-se- Zane, which interpreted means "the Queen of the Light."

WE unloaded our basket, and gave its contents into the hands of attendants, to be bestowed as her Majesty should direct. Realizing that we had been made her Majesty's guests in a most mysterious manner, we felt that it might prove a wise discretion not to place ourselves in the power of even so beautiful and apparently amiable a woman, without some means of defense. Our rifles were out of the question, and we allowed them to disappear along with our other traps, but a brace of Colt's revolvers and several packages of cartridges we each had already conveniently secreted on our persons. Discharging the gas from the balloon, we put it in shape for convenient storage, and, borne by a number of natives, saw it disappear in an opening in the cliff. A moment after it closed again, so that from where we stood we could not point certainly to the spot. Then her Majesty marshalled us in, and the rock closed upon us in a like manner.

"It's the hair under the diamonds that I don't like," said Harding, as he adjusted the revolver on his left side.

Before we saw the outer world again, we had beheld some strange sights, been made familiar with a new system of civilization, and become actors in a tragic drama that began some six centuries before.

Many strange problems crowded upon my mind, asking for solution, when the machinery of this palace closed us in; so many, that I failed at first to note and wonder at the fact that we were inclosed in rock, with no apparent openings, and yet there was no diminution of the light. Every object within was as perfectly revealed as if it were in the broad glare of open day. I say, I did not notice, I was so oppressed with mysteries already. We had been three hours on a lonesome plain, where, indeed, our balloon may have been observed and wondered at by some native, but how did this strange woman learn of it and us; and how had at least five thousand natives, spread over ten square miles of territory, as I judged, been summoned to do us honor? Why were we received by them like a pair of princes, whose coming had been expected? Where were their habitations? Why was this Queen's palace quarried out of the quartz rock, instead of being built on the surface? Who cut and polished those diamonds, burnished the gold, and carved the numerous animals whose forms were composed into such a wonderful portal as we had entered, and along which we continued to pass for some distance? It was positively painful not to be able to converse with our fair conductress, and have the mysteries cleared away. We passed beneath a series of these fantastically-carved arches, between each of which we could see passages on both sides, leading to departments of the castle, and at length entered a large apartment, brilliantly lighted. Yet it was mild light, against which the optic nerve made no protest. From the dead white of the walls, seamed with gold, which accounted for the profusion of that metal, stood forth numerous fanciful forms, that glowed and sparkled with ever-shifting light as we moved. They were made of quartz crystals, cut and polished, and massed into shapes of birds, beasts, and reptiles. Then, for the first time, the wonder possessed me of whence came the light. Casting my eyes to the ceiling, I discerned here and there among the tracery of crystals, small disks that glowed like so many miniature suns, only the light was white. This was evidently a dining-hall, and one that had been furnished with no view to change of style. A long table, of antique pattern, that suggested Europe in the simple fact that it was a table, and occupied the centre of the room, was surrounded by seats at regular intervals, all of the same form, save one at the head of the table. This seat was larger than the others, more elaborate in design and carving, and gorgeously ornamented with such gems as made the Queen beside us a figure of moving light. Table and chairs had all stood there, literally, since the foundations of the earth; for they were severally carved where they stood out of quartz. The same was true of divers seats and tables of smaller dimensions stationed about the room. The seats were all softly cushioned with pillows, covered with the same fabric, woven of hair, that I had first seen upon the tusks of San-son. It was a fabric of wonderful beauty, and if, as I judged, it was not in use among her subjects generally, then the elephant on which we rode was hers. She approached the head of the table, and with a grace that combined the elastic movement of a savage with the cultured ease of refinement, motioned us to seats on either side, laughingly speaking to us in her unknown tongue. I heard no order, saw no sign, yet there tripped into the room three of the sweet-faced hairy attendants, in short skirts and sandals, one of whom divested the Queen of her gemmed himation, while the other two stood at our sides, subject to our commands. There was nothing else for us to do but follow our own customs, and give them our hats. It was but a moment,—they moved so quickly, these hairy creatures,—when they had made their low obeisance and disappeared, and the Queen stood before us in her simple chiton of gold cloth. For the first time had her arms and neck been exposed to our view.

"After all," said Harding, as he took his seat, "there isn't hair enough to hurt."

On her throat and neck was no hair at all, and that on her arms was like a thin covering of silken floss, through which her transparent skin shone like alabaster endowed with life. They were perfectly moulded, and seemed the more beautiful for their half-concealment. She took her place at the head of the table, and instantly came trooping in, as noiselessly as phantoms, a company of attendants, each bearing some article of food. We were becoming accustomed to the situation, and Harding grew humorous again.

"Good!" he said; "I haven't been quite sure whether these people lived on food or whether I have not been dreaming. It's just four o'clock," he continued, taking out his watch; "don't you consider this an early breakfast?"

I could not resist laughing, while the Queen looked on with an inquiring smile; and Harding, who had suddenly remembered that if his watch should run down he would lose all notion of time, began to wind it up.

"Why, it ticks as loud as a clock," he said.

I took out my own, now useless timepiece, and showing it to her, endeavored to explain how the hands went round upon the dial, telling us when to eat and when to sleep. She understood my signs, and the idea that we required anything to tell us when to eat and sleep was infinitely amusing to her. That musical laugh of hers rang through the hall, while she pantomimed that she ate when she was hungry and slept when she was sleepy. I tried to express some idea of time by signs, but Harding interrupted the unsuccessful effort with the remark that I was wasting my time, as they had neither day nor night, nor sun, moon, or stars, and possibly no seasons.

"But they grow old and die, and I assume they are born," I replied. "I can't conceive of people having no idea of time."

The Queen laughingly pointed to the watch, and indicated that it was telling us to eat, at which we all laughed heartily and began to partake of the first food-products of the new world that we had tasted. They consisted of a coarse, sweet bread, that I thought had the flavor of oatmeal; a species of grape, large and luscious; and a fruit much of the flavor of bananas, though of a different shape. Before each of us were goblets of wine and milk and a huge egg, from which the apex had been removed, and the contents prepared with salt and spices that made it delicious. There was also a shell-fish, which I supposed to be a monster oyster, that had been stuffed with sundry spiced condiments and baked. The meal, which was simple enough, was served upon gold dishes, varied in form according to their uses. I examined them closely, and concluded that beyond a doubt they had been beaten out of solid ore and shaped upon carved blocks with ornamental designs in relief upon them. Our meal ended, the Queen arose; the attendants appeared, and stood with bowed heads while she lifted her hands and gracefully described an arc of a circle that included us within its circumference. The attendants chanted some words in unison, and, bending low before us, again disappeared. It was evidently some ceremonial, by which they became devoted to our service. She motioned us to follow, and we passed into another and larger apartment. I had thought that there could be nothing more beautiful than the hall we had left, but I was mistaken. This I saw at a glance was the great reception-hall of the castle. The raised dais at one end determined its character. I was struck dumb with amazement when we entered, oppressed with a sense of its vastness and grandeur. Hitherto the light had been reflected from white surfaces, but here the air was flooded with the rich, red light given out by literally myriads of garnets, of which the designs and traceries on the walls were formed. I supposed at first that it was a mosaic work of colored crystals, but a near examination afterward made convinced me they were gems, each one of which with us would be a fortune. Against the white background flaming serpents seemed to writhe and twist with every step we made, and, as if they had been formed of livid flesh, the muscles of ferocious beasts seemed to work as if they made ready to spring upon their prey. In the centre the waters of a fountain arose nearly to the roof, throwing back in many shades of red the garnet-colored light. The throne was ascended by a short flight of circular steps overlaid with gold. Upon it stood, fixtures like all the rest of the furniture, three chairs of state—not on legs, but pedestals—on a line with the curved front of the dais, which brought the central and most elaborately designed one slightly in advance of the others. It towered not less than ten feet above the head of the occupant, and, as well as those beside it, was upholstered with the hairy fabric I have described. Its distinctive feature was the jewelled arc above it, from which rays converged to a common centre. This did not glow with reflected light alone. It had living light within it and shone like a veritable sun. I saw, however, that it was not an emblem of that luminary, but of the canopy of light over the North Pole, which gave the interior world its endless day. Back of it was an alcove of dead white, which gave it relief. Above it was a carved canopy supported by animal forms, among which I noticed that the serpent was conspicuous. The Queen ascended the throne, motioning for us to follow, assumed the place of state, and waved us into the seats on either side. Then, from opposite doorways at the further end, glided in a company of dancers clothed in chitons of metallic cloth that reached from neck to knee. They had cymbals and other musical instruments such as I had observed in the procession, with which they kept time, in a strange, melodious harmony, to the movements of an intricate dance. Their glittering forms moving in the colored light were like some vision that seemed only possible to an unrestrained fancy,—something that could not be realized. The dance ended, we descended from the throne, and, leaving the audience- chamber, entered a long passage. Stopping before a slight indenture in the wall, a solid rock door slid back, and revealed a gorgeous sleeping apartment. The Queen, once more pointing to the watch in my pocket, laughingly laid her head against her hand and closed her eyes. This invitation to sleep was gratefully accepted, but I wondered how she happened to know that we were sleepy. I had not slept for about twenty hours, and, besides, I wanted time to collect my confused senses. Harding and I were not destined to occupy the same apartment. We were ushered into adjoining rooms, which we found oddly furnished, yet provided with everything our needs demanded. Our strange hostess before leaving managed to inform us that by uttering the word "Tet-tse" an attendant would appear. Tet-tse, therefore, I concluded, was a word that probably signified servant, and that our Tet-tse belonged to the Queen's establishment in that capacity. Of course, this added one more to the mysteries that were as yet unsolved. I entered my room fearlessly, though aware that we were effectually imprisoned, and, divesting myself of my outer clothing, threw myself upon the softly-cushioned couch that invited me to repose. My head had not touched the pillow when utter darkness supplanted the light. I acknowledge to being so terrified that I leapt to my feet again. Instantly the room was once more flooded with light. I looked about me, but could imagine neither how the light was introduced nor whence it came. After all, it added but one to the wonders awaiting explanation, and, lying down upon the couch in the midst of darkness, I eventually fell into a slumber that, you may be sure, was filled with some of the most fantastic forms that ever peopled dreamland. Among the nymphs, satyrs, and fearful monsters which thronged through the vacant chambers of my brain that night, there came one in human form who put them all to flight and chased away sleep at the same moment. If this form had vanished with the others when my eyes opened, it would have neither given me cause for special wonder nor disturbed my waking thoughts, but the form refused to thus vanish with the others. I was unable to bar it within the limits of dreamland. I rubbed my eyes in the darkness to make sure that I was awake, and it invariably remained palpable to sight for a few moments. You will have concluded that this persistent phantom took the form of the mysterious and beautiful Queen. Not so: it was a very lifelike image of a young man, little if any older than the Queen. He had long, glossy, golden hair, like that of the Queen, only a shade or two darker. He had the same fair, transparent skin and regularity of features, but they were wanting in all those lines of expression which rendered the face of the Queen so spirituel and attractive. The form was clothed in tunic, trunks, and hose, with a loose coat over the tunic. The breast of the latter was richly ornamented with jewels, and all the clothing was made out of a fine quality of that same hair-cloth with which the palace was upholstered. If this phantom—which I tried to persuade myself was a mere waking phantasm due to nervous excitement—had taken the form of the Queen, or had not returned to disturb me at intervals, I should have thought nothing of it; but often it was the first object on which my eyes fell immediately on awaking from sleep. I spoke of it to Harding, who, of course, pronounced it a mere nervous fancy and laughed at me. I therefore kept my own counsel thereafter, and tried the best I knew how to account for the mental phenomenon.

You will perceive, sir, that thus far I have given you an imperfect history of our first day, you may say, in the new world. This was followed by many days, during which we were treated with the most careful consideration and had all our desires anticipated. How the Queen was thus enabled to respond to our unspoken wishes we could not understand. She spent much of her time with us, and her blue eyes followed us continually. They haunted us. Had their expression not been as mild as those of a fawn, I should have felt very uncomfortable. But a few days had passed when it became apparent that she was acquiring English far more rapidly than we were Toltu; in fact, forty-eight hours after we had become domiciled in the palace, she found little difficulty in communicating whatever she desired. She was not disposed, however, to declare her intentions in regard to us, but left us on the ragged edge of uncertainty. Nevertheless, her reserve aroused no suspicion that her ultimate object was evil; her benignant face bore no trace of cunning.

"Amos, old fellow," said Harding, when we were left alone after a long conference, "she's a witch. There's no doubt about that. I can't explain just how I happen to know she's a witch, but I'm expecting her to change into the form of an ancient crone. See if she don't before she's done with us."

"I never saw a witch," I replied, "but if the most beautiful face I ever saw; the most sympathetic and silver-toned voice I ever heard; the most dignified, yet gentlest expression I ever beheld on a human face; and, if the blending of the discretion of a sage with the joyous spirit of a child, are characteristics of a witch, then, my dear boy, this Queen of the Toltus is beyond all question a witch."

With mock gravity Harding shook my hand vigorously, exclaiming: