RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

I WAS spending the Ottobrata of 1896 alone at the Monastery of Monte Cassino, not far from Naples. The festa dell' Ottobrata is the last Sunday of October, when in Italy, amid the witchery of autumnal pathos, people go forth into the country to take leave of the dying summer. It is a pagan day, kept pagan through all the monkish centuries, and whoever has witnessed it must have realised how deep a pagan significance underlies the festivals of Italy. There is often some faint survival of the measured classic dance, an instinctive libation poured to Bacchus, and a rural promenade—last relic of Eleusinian processions—to the groves Diana loved. The Ottobrata has come to be a day of forest meditation, spent amid the redwood's beautiful decay. Its charm is incensed with the fine odour of fallen leaves, and to the humblest imagination the flaming sunset rekindles for an instant a semblance of the transfigured Past. The close of such a day is the turning of an illuminated page.

During the preceding weeks I had been with Professor Vaini at his Villa Sirena, assisting in the completion of a mechanism he called our Penumbra, thereby associating it with that occult shade which lies beyond the things of earth. That shade, he knew, could be penetrated provided within the intellectual workshop some artifice could be contrived so keen as to become susceptible of telepathic photography. This perfected mesmerism demanded the invention of a reflector of such psychical delicacy as to reveal and record the consciousness of another mind, whether near or remote. It was to flood unknown darks with a gleam as far beyond our ordinary ken as in microscopic studies ultra violet surpasses visible light, and upon the reflector of this clarified vision to project telepathic negatives. Brain evolution was to reveal itself like the mutation of a kaleidoscope, and the mental spectrum was to show the irised rings of thought, as the solar spectrum defines those of colour. Scientifically speaking, he called it a compound telautoscope. Its exquisite surface had been so refined that it faintly recorded the distant voices that are for ever whispering, and which our physical sense is not attuned to hear. It was indeed a masterful conception to control those frail bonds that join life with life and Past with Present. Now all was ready; the reflector shone like a soap-bubble, its antennae were charged with nerve-fluid, its centre of electric gravity was determined. What type of experimental subject, I wondered, would Vaini select?

On that Sunday morning, October 25th, 1896, the Neapolitan police awoke to discover that a murder of unusual atrocity had been committed the previous evening at 31, Via Amadeo. During the afternoon popular interest, which in a city steeped in vice takes small heed of homicide, became excited over the details of the crime which had ended Saverio Cinquedea's life. There were dramatic and conflicting circumstances which so effectually ha filed the chattering authorities that on the following day several newspapers gravely suggested that Camorra alone could adequately strengthen the arm of Justice. The victim was a dealer in antiques and Renaissance objects, aged 39, of good means, the lower part of his house being his curiosity shop. The entresol was occupied by him alone—bedroom in front, office at the rear. It was in this office that the crime had been committed. On the upper floor lived his wife with their boy Beato, aged eight, and the child's nurse. Above lodged two women servants. Two salesmen, a bookkeeper, and an office-boy came every work-day at eight in the morning to open the shop, and it was in attempting to rouse his padrone that the lad stumbled over his dead body.

An office-boy came every work-day at eight in the

morning to open the shop, and it was in attempting to

rouse his padrone that the lad stumbled over his dead body.

The antiquary was lying on his back, dressed in his familiar suit of broadcloth, and the autopsy showed thirteen stabs in the body and five on the left forearm. His protruding tongue indicated that he had been so tightly gripped by the collar from behind that strangulation would have prevented any outcry. His watch was in his fob-pocket, the gold links in his cuffs, and one hundred lire in his purse. Robbery was not therefore the motive, and in his breast-pocket was a note-book containing papers of no special importance which had not been disturbed. The body was bathed in blood, which had splashed high upon the wall. On the inner side of the office door a bloody hand had rested, smearing the white paint with finger-prints. It seemed probable that upon his return home at about half-past ten, to which the porter of the Hotel Paradiso testified, he had let himself in by a latch-key, extinguished a lamp, and entered his entresol office leaving the hall in darkness. He had lighted a candle in his room, exchanged his shoes for a pair of slippers, and opened a newspaper. At that moment he was set upon by some one of powerful physique, who, clutching him from behind by the coat-collar, inflicted the first two or three wounds on the right side of the neck, severing an artery. The unfortunate man had apparently wrenched himself partly free, and, with outstretched hands, had sought to clutch his assailant's blade. Curiously, his left arm alone had been lacerated. The wounds on his body would have killed three men, and the surgical experts declared that the attack had been made with such rapidity and skill that not more than two minutes had elapsed between the first blow and the collapse. The assailant must have been sprinkled with the blood that leaped from so many wounds, and on the stairs were footprints and fingermarks of one feeling his way down in the dark.

Public suspicion had quickly fastened upon the dead man's widow, Delilah Cinquedea. It was notorious that, though domiciled under the same roof, they lived apart on bad terms. A month before the murder ten thousand francs had been stolen from the antiquary's writing-table, and he had violently accused her of the theft. The wife had been heard to answer, with a scream of fury, that she wished her husband dead. She was handsome, reputed a woman with a past, and it was surmised that Saverio's declared resolve to turn her and their child from his door had to do with her adventures.

Some such brief notice I had read in the Messagero when, four days after, came a letter from Professor Vaini informing me that the Judge of first investigation, having the powers of an English Coroner, had authorised the scientific analysis he wished to make conjointly with the inquest. "Carissimo," wrote Vaini, "you have been applying yourself too much to shadowy thoughts. Give yourself a fortnight's relaxation. Join me (to-morrow if possible) at the Grand Hotel, and we will uncover the intrinsic secret of life." It would have been ungracious, not to say ungrateful, to refuse, and the next afternoon found me with my former tutor.

The Professor had made an end of his vegetarian luncheon, and, erect and agile, despite the burden of seventy years, was pacing up and down his sitting-room as I entered. His first word took me aback.

"Carissimo," he began, seizing my hand and looking in my face with a mischievous smile, "you have never had a love-affair —and that is wrong, because every man should taste once of that elixir. It keeps the heart a-bloom. It is not too late, and I have summoned you to an opportunity that is unique. The case against Delilah Cinquedea is overwhelming—motive, opportunity, means, all are present. She is clever, fine-looking, well mannered, and fascinating. Of course she is in prison, the enormous bail of fifty thousand francs not being forthcoming. It is upon her that I wish to test the Penumbra, which should read her mind like an open book. But first a little suavity is necessary to bring her out of the distress and exhaustion wherein she has circled these last days. I am myself too agitated for this, therefore I wish you to go as a good Samaritan, with wine and roses and the oil of gentle words, to bind up her wounds. Tranquillise for me this frightened woman, and when her mind is calm and responsive, we will make the experiment of the age. Present yourself in the skin of a sympathetic admirer. Make yourself agreeable—Malandrino amabile!—and you will be asked to warm both hands at the fire."

The Professor talked on, painting as usual with a broad brush and adding fine lights with a diamond. "In spite of our ephemeral contact with modern ideas," he added, "Naples remains the centre of classic and mediaeval crime. It still has its Eleusinian Mysteries, and these are often a prelude to the knife. You must be careful to avoid what has happened to me—or worse."

"What has happened to you?" I exclaimed.

"On leaving the Police Office yesterday, its chief threw his arms about me, and invoked a blessing. Half-way here I missed the gold chronometer you gave me—the watch-chain was cut. It is not so bad as leaving a Cardinal's presence in the old days, and being done to death on the stairs. 'Friend of my soul,' he murmured, 'I shall never forgive you if you allow yourself to receive a coltellata in the ribs.'"

Persuaded that the sealed gates were about to unfold and disclose the hidden, hoary secret, and believing the Professor's latest mechanism to be the crowning miracle of the century, I waited only to obtain a Police authorisation to enter the Cinquedea house, whither I immediately directed my steps.

The Galleria Cinquedea, as its owner styled his shop, was familiar to me. I had often made purchases there, and several times, happening to visit it in Saverio's absence, had been received by his wife. Upon presentation of Vaini's order I was at once admitted, and allowed to pass from room to room, where every object was in situ. The house had suddenly become a place of sinister stillness. I first examined the hall, where stood a Roman statue of Apollo holding a lyre. On the leg was a russet stain where the departing assassin had laid his bloody fingers. On the hall door and beside the staircase were other such marks, and the knob of the office door was a dull red, where a blood-wet hand had closed it. I went to the chamber in which the crime had been committed, and saw the dead man's shoes kicked aside by those trampling feet, a chair overthrown in that furious scuffle, the wall spotted as high as my hand could reach. Here was the writing-table from which, a month earlier, ten thousand francs had disappeared. It was noteworthy that for a year past Saverio had taken his meals at a restaurant, avowing a wholesome fear of his household medicine-chest.

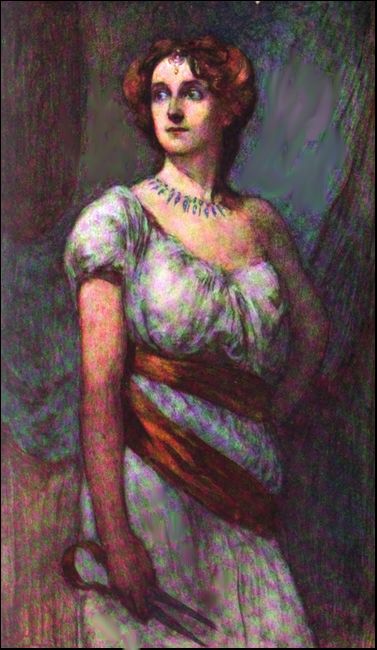

Above were Signora Cinquedea's deserted bedroom, sitting-room, small dining-room and, overlooking the garden, a chamber occupied by her boy and his nurse. In the Signora's apartments were a Venetian mirror, a painting of herself in fancy dress as the Biblical Delilah, an imitation Louis XVI. bed, an ivory archlute of extraordinary beauty, a dressing-table with the usual paraphernalia of flacons, brushes, and étuis, and over all the florid Italian colour and decoration.

In the Signora's apartments was a painting of

herself in fancy dress as the Biblical Delilah

The theory of the prosecution, as set forth in a preliminary procès verbal Vaini had put in my hands, was that Delilah Cinquedea had secreted herself in her husband's entresol in anticipation of his return. That, armed with a stiletto the slender blade of which inflicted wounds four inches deep, she had attacked him with a swordswoman's skill and with a physical power equal to that of a strong man. That, the attack ended, she had gone downstairs to the basement kitchen, that there she had cleansed herself, burnt her bloodstained clothing, and made away with the stiletto. That she had then returned to her room, and retired to bed, and had risen the next morning as usual, taken coffee, and talked with her child. That, upon the announcement of Saverio's death, she had burst into a flood of hysterical sobbing which the police downstairs heard and mistook for loud laughter.

I have mentioned having occasionally spoken with Signora Cinquedea at her husband's gallery. I was now so persuaded of her physical inability to commit the crime that I resolved to visit her in gaol and inform her that I would go bail for her, and that she should be free that evening. My solicitor received a cheque for fifty thousand francs and promised to meet me at the prison in an hour with the official release.

I was shown into a room at the place of detention, where the accused was seated at a table on which lay books and a work-basket. Before her stood the nurse Agnese, to whom she was giving orders for the care of her boy. Both turned as I was shown in, and I noticed in the maid's face the cunning slave-look of the Italian domestic. She evidently knew me, and showed her prominent teeth in a stealthy smile.

The Signora Cinquedea rose at sight of me, and, dismissing the maid, advanced with outstretched hands. In her fine brown eyes lurked the immemorial look of the hunted, as she fixed her gaze upon me with eager surprise. "You are sorry for me!" she exclaimed, "are you not? and let me swear to you at once that, through all this horror, I have a pure desire for the truth."

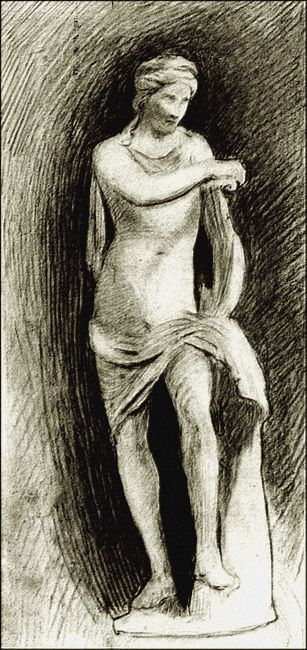

Her profile had the classic grace of a Greek coin, and athwart the October twilight her Venetian hair caught a reflected glow from the crimson heart of the wood fire. She might have been Artemis, the huntress, standing in statuesque poise, self-possessed and self-sufficient, uplifted above the wicked and ignoble things of earth.

"You have not forgotten me," I answered, placing in her hands a posy of the roses that grew at the Villa Sirena, and which in these later years I have named Toujours ou Jamais.

"I heard what has happened from Professor Vaini, whose gifts will all be required to unravel this tangled web. I am convinced of your innocence—for you cannot be guilty. Ere the coming month is past, I shall have cleared you before the world."

At the words new hope and life and colour came into Delilah's face, and she lifted her radiant wet eyes to mine. "I am not afraid," she whispered; "I can think like a man. I swear to you by the bread and the wine, by my belief in salvation, by my hope that my child may live—that I am innocent."

In after days I often recalled Saverio's widow as I then beheld her, with the tears glistening in her eyes. She was neat-handed and fine-faced, and her figure bore the voluptuous classical contour. Perhaps a drop of untamed faun's blood leaped in her veins. It was one of my fancies, observing the faint flush beneath the sunburn, that she kissed a pink rose every morning. In her ears were heavy gold rings encircling a tiny coral twist that averts the evil eye. The year before she had told me of her joy in the al fresco life, delighting in her half-tropical roof-garden that overlooked Virgil's tomb, and the plain where stands Pompeii and the Roman Surrentum across the bay; for in Italy, she aptly said, the past never fades wholly from view.

THE next day passed in further investigation and in reading police reports, and I did not see Vaini until we sat down that evening to an over-late supper. He presently remarked that already the Neapolitan Camorra was obstructing the inquest and preparing to block the trial. Then, with a quiet smile, he added: "I have just learned, through a private inquiry office, that after the disappearance of the ten thousand francs from Cinquedea's desk, his wife paid off several pressing debts. I suppose," he added, "that you have seen her to-day."

"I saw her late yesterday," I answered, "and she wrote this morning, asking me to lunch to-morrow."

"To lunch!" echoed the Professor, greatly astonished.

"Yes," I replied, enjoying his surprise; "you bade me act the good Samaritan, so I have gone bail for her, and she is temporarily lodged al the Hotel Paradiso round the corner."

When Vaini swore it was a good mouth-filling oath that rang and rattled ere it died. Perhaps it was well for the harmonies between us that I was able to divert him with an item of interest.

The antiquary's whereabouts during the last afternoon and evening of his life was a circumstance of obvious importance, and at the end of a week was still unknown. Where had he dined? In whose company had he spent those last hours? Whence had he come at ten o'clock that evening to let himself into the deadly ambush where a figure crouched upstairs in the darkness?

The police had shown me Saverio's pocket-book, among its contents being a fresh newspaper cutting on which were three tiny red-ink marks, and the thought flashed upon me that herein lay the fixing of an appointment.

Count the letters of the first line = 6.

Count down to the 7th line (7th day of the week) = Saturday.

Count down to the 24th line (or day of the month) = 24th.

"At six o'clock, Saturday, 24th."

Were this a trustworthy conjecture, it would show that, shortly before the crime, Saverio received this summons in a form that, if intercepted, would convey no meaning to his wife.

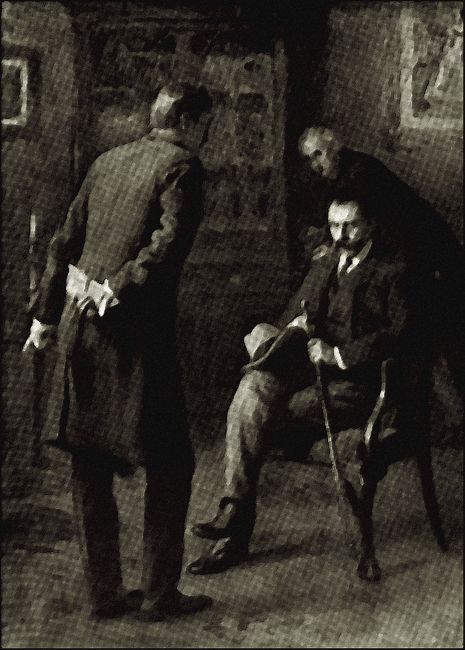

"It sounds ingenious," growled my former tutor, not quite recovered from the shock of my interpretation of the good Samaritan. "But it is beside the mark, and to-morrow morning we will take better aim. The Penumbra has been made ready in the room where the crime was committed, and there we will test it upon Gennaro Riva, a retired Captain of the Italian Army, whom the police hold as accessory. You will question him, whilst I, moving about the room, will direct our instrument. It matters little what line your inquiry takes, since what I seek is the thought at the back of his head."

THE next morning the Professor and I were in Cinquedea's

office with the apparatus in readiness, when a police official

announced "Il Capitano Riva." A man of forty, slightly under six

feet, of olive complexion, and thick short moustache, entered,

walking smartly and holding himself well. He was good-featured

—the style of head barbers place in their shop windows. As

he seated himself I became conscious of a faint aromatic odour of

musk. Vaini stepped aside and looked out upon the garden, while I

plied the Captain with questions. Presently the Professor moved

to a bookcase behind the accused, and directed the sensitive

retort towards him.

The Captain was manifestly ill at ease, and looked nervously about as I indicated the fresh stains on the wall, and the spot where the dead body lay.

The Captain was manifestly ill at ease, and looked

nervously about as I indicated the fresh stains on

the wall, and the spot where the dead body lay.

"And the Signora Cinquedea," I inquired, shifting the line of attack, "how many years have you known her?"

"A speaking acquaintance for ten years or less."

"Is it true that several years ago her husband forbade you his house?"

"It is not true."

"Two nights ago," I said, fixing him with a straight-flung Italian gesture, "the Signora's private box in her bedroom was broken open, and a receipt found for something deposited in the bank. Yesterday that receipt was presented by a police official, and a pacquet of letters surrendered in exchange."

The Neapolitan's impassive face flushed as though I had struck him. "Those letters are mine," he answered, his eyes dilating with excitement; "they can only have been obtained through fraud."

"Compromising letters from you, for which Signora Cinquedea holds the receipt!" I retorted, laughing at our enemy. "This implies an intimacy which, in view of the murder of her husband, will have great interest for the jury."

Captain Riva listened in ominous silence, and his handsome face darkened. Had we been alone, I believe he would have leaped upon me.

"These letters," I continued, showing him the pacquet, with its broken seals, "were placed in my hands last evening, and have been read. There are allusions to a duel fought by you nine years ago, on behalf of Cinquedea's wife. Tell me the motive of that duel."

"The quarrel was over a card-table, and nowise concerned the Signora, though she felt a deep interest in it, because she knew both combatants."

"Your opponent," I continued, "was Count Scarafaggio, a professional card-sharper. Was he also 'a speaking acquaintance' of Cinquedea's wife?"

A faint smile moved the lips under that dark moustache, as Riva answered: "Count Scarafaggio is Signora Cinquedea's brother."

"From the allusions in your letters," I observed, "I inferred him to be her lover. There is no mention in them of a card-table dispute, but of something more emotional."

"It is true that there was something behind the altercation over cards. The Signora had become very angry with Count Scarafaggio, having detected him in a dalliance with one of her maids."

"So angry," I added, "that she insisted upon your fighting him, and resorted to the old trick of a game of cards, behind which there is always a woman. She was so furious with Scarafaggio—her brother, you ask me to believe—that she wished him dead. Was there not beneath all this a ferocious jealousy of her own?"

The Italian made a miniature passato with his walking-stick at a heart-shaped flower in the carpet pattern, but answered nothing.

"You took Delilah from him, or he took her from you—which was it?"

I asked, hazarding a flight of fancy.

At this climax, much to my annoyance, Vaini interrupted our dialogue by that expressive Italian movement which signifies Basta, enough.

The Captain gone, I threw wide a window to clear the room of the musk odour with which he scented himself, and, before casting my eyes upon the sensitive plate Vaini held out to me, I exclaimed, "Whatever the Penumbra may say, that is the man who killed Saverio!" Then, glancing down, I deciphered, amid a spider's web of phrases, these gleaming brain-words:

".... trap to bring me to this room... brave front... what are they but a pair of charlatans?... how does he know that?... if only a few of our galantuomini were here!... not another so soon... lover, brother... brother, lover....

"You bedevilled him with so many lines of attack," grumbled the Professor, "hence this confusion. Your luncheon hour approaches, and I wish you to arrange that the Signora comes here to-morrow, upon whatever errand you please. Next time you shall direct the tablet, and I the inquiry. I quite share your opinion that Scarafaggio is a lover in the travesty of a relative."

As he finished speaking I glanced again upon the Penumbra, and beheld that it was flashing like a kaleidoscope in a fit. Could it be that we had passed unbidden beyond the borderland of human things and were arousing unknown and dangerous forces?

SIGNORA CINQUEDEA breakfasted—or, more properly

speaking, dined—at noon, and twelve o'clock struck as I was

shown into the dining-room of her apartment at the Hotel

Paradiso, where a table laid for two was spread with the Italian

antepasto A bottle of golden Episcopio and one of ruby

Chambertin stood sentry between the olives and sardines, and my

posy of Toujours ou Jamais roses, the only flowers in the

room, was beside them.

My beautiful hostess entered smiling with serene amiability, unperturbed by her tragic situation, yet with a subdued and saddened look—a shadow on the brow of Athena. She was dressed in pale fragrant drapery, and was no longer yesterday's type of a woman waiting upon the accidents of fate. She thanked me again in a fluent phrase for her temporary freedom, and there was in her utterance a subtle intonation and cadence that seemed the gamut of a sweet, deep nature.

"And now," she continued, "come to table. The fritata is served; let us drink the wine of friendship. Be mine a world of peace and humble plenty—of music and your roses. Above all, no love. What is the love you men are for ever vaunting but a base passion, selfishness, and a jealous vanity that turns sour at every change in the wind? I suppose," she added, looking up with a wicked smile, "you talk your light-hour love to all the loveless girls that listen. Detto, fatto! no sooner said than done."

"On the contrary," I replied, piqued at this persiflage, "I belong to a Thinkers' Club, the 'Chosen Few' whose business it is to realise ideals. My holidays are devoted to the study of sidelights upon curious things, and I am as shy of love-making as Joseph."

"How many belong to your Club?" asked Delilah.

"The Chosen Few are Professor Vaini and I."

"I know Vaini," observed the lady, as a rizotto was placed before us. "He is what the French call une boîte à surprises. Be not vexed, at my imperfect appreciation of him and his sidelights. To be so wise you must read much. I do not care for books; so many of them are what Englishwomen call rot!"

"You are so far right," I answered, "that a library does not hold more truth than a wild forest: I have never known my own mind so well as at twenty, when I lived one summer in the woods and caught my trout in mountain streams and baked my potatoes in the ashes."

"And now," she interrupted, pouring me out a cup of black coffee, "you cling to those tags and labels the world ties to our skirts. To think that I should be sitting alone with such a rake-hell!" Then suddenly her banter ceased, and with great earnestness, her dark eyes half a-dream, she murmured, "It is because I feel safe with you, I who am a prisoner in the enemy's camp; who, in the midst of this misery, can say with St. Paul, I die daily."

"The good book says, Peace be to thee, fear not, thou shall not die."

"May your words be prophetic!" she exclaimed; "if I do not weep, it is because such words ring in my soul."

"It should still further encourage you," I said in confidential sotto voce, "that I have formed my own theory as to the crime. I return presently to your house for its verification. If I am right in believing that Saverio was killed by two assailants, both of whom left the house immediately after its commission...."

The Signora listened with so sudden a change of expression that the next words faltered unspoken. Her lips hardened and her eyes glowed with tragic consciousness. She rose abruptly, and, walking to the mantelpiece, lighted a cigarette. Turning, she faced me with her accustomed calm, and said in a quick low voice, "I have heard many theories, and some," she added with an ironical laugh that rang with bitterness, "are much more silly than others."

Then suddenly, casting aside her cigarette and her defiance, she said: "A month hence, when this horror has ended, you will think more gently of me. When life draws to a close and twilight falls upon our little labour—we remember its morning. It is so with our attachments—when the storm is past, Time, the consummate artist, refines and endears our humblest memories."

My thought took wing at the light in her face—the light of the Italian afternoon that touched her with its benediction. And behind the eyes that looked so deeply into mine—behind the words a-quiver on her lips—I divined a subtle secret silence like a bird's heart beneath the folded wings.

On leaving the hotel I returned to the Galleria to resume the task of piecing together circumstantial evidence. Assuming that Vaini's apparatus gave its testimony in favour of the accused, her defence would be vastly strengthened by a background of fact. The bloodstains led from Saverio's room to the foot of the stairs, where they parted, one line continuing to the kitchen, the other leading to the front door. The impression grew upon me that the injuries to the body, strangulation from behind and stabs in front, showed a double attack. The antiquary had been seized by the back of the collar, the same assailant holding his right hand, Cinquedea's left arm only having been lacerated. The second assailant, who confronted him, had delivered a succession of stabs in the region of the heart, and the swift attack had been executed with the violence of tremendous passion. If I were right in suspecting Captain Riva, who was the other assassin?

At this half-spoken ejaculation, I became conscious of a cat-foot presence behind me, and turning, beheld what John Bunyan terms "an ill-favoured one" watching my movements. The newcomer was a man of forty, well dressed, and with as hang-dog an expression as I have ever seen. His furtive scrutiny changed to a fawning smile as he introduced himself with Neapolitan volubility as the Signora Cinquedea's brother, Count Scarafaggio. He added with unctuous suavity that, being aware of the service I had rendered his sister, he was impatient to present his thanks.

There was a faint white scar on his cheek such as the cut of a whip might leave, and the thought came to me that, in the death struggle, Saverio had struck him with the rattan walking-stick found on the office floor.

"I am persuaded of the lady's innocence," I answered, "for the proof is clear that the crime was committed by two persons, both strong men like yourself, who, their work done, left the house by different exits. The woman, had she made the attack, would have returned whence she came. Why should she wish to go out into the street? But no stains lead upstairs from the antiquary's room. The two men come down feeling their way in the dark. One touches the statue, and, thus learning his own position, makes for the door. The other takes the direction you are looking, to the service stair, washes himself in the kitchen, and lets himself out by the servants' gate.... What is the matter? You seem troubled... you are pallid as this marble."

Count Scarafaggio's white, frightened face was telling the truth. "Povero Saverio," he stammered, "you bring that horrible scene so vividly before me. But now, I go. I have interrupted you too long."

DELILAH had mentioned at my leave-taking that she purposed returning that afternoon to her own residence, from which the police were withdrawn. I told her of Vaini's wish to perfect our line of defence by asking some questions, to which she reluctantly consented.

"Vaini is a puffed-out fraud," she muttered, and spat venomously upon the ground.

The maid Agnese was in the closed curiosity shop when I arrived next day, and with her the boy, Beato, playing hide-and-seek about the statue that still bore the imprint of Saverio's blood. Of this child his mother was wont to say, "I love him so dearly, that in some other life, ages ago, surely he was my lover!" With humorous malice I advanced to Agnese, and, shaking her warmly by the hand, gave her the secret Mano Nera grip of the Neapolitan Camoristi. She started at the touch, and at the same instant I perceived about the child Beato the musk odour which Capitano Riva carried as a fox bears his scent.

"Why is it," I queried with a kindly smile, "that whereas all Christians uncover in presence of the dead, Justice puts on a black cap before those sentenced to die?"

"Before our blessed Virgin," stammered the maid with trembling lips, "I am innocent. Can you slay me, yet save your own soul alive?"

Amused at the effect of my Camorra hand-grip, I asked abruptly, "Tell me something of Count Scarafaggio. Are he and your lady related?"

"Signore," replied Agnese with affected candour, "I have never told a lie. If I am to be killed, let me die in the open. I will avow to you there is a simpatia between them."

"You mean they are lovers?"

"Blessed Maddalena! does not every woman wish to burn her fingers at the flame?"

"Yet the Count told me they are half brother and sister."

"Quel brutto scalzacane—that ugly, barefoot dog that only gave me five francs last Christmas!"

"No matter. But what makes this child smell so of musk?"

"What would you? is it not his nature?"

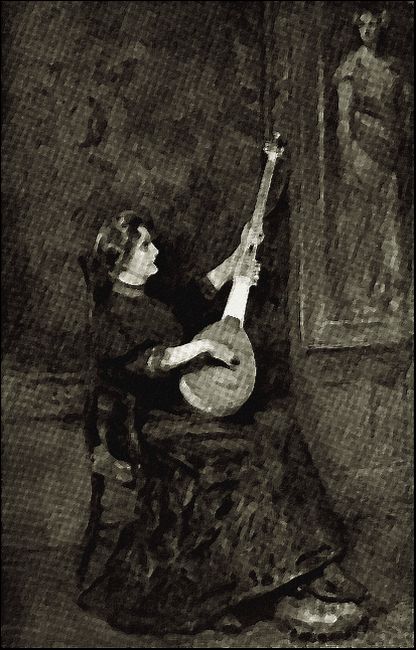

"Why should it be his nature to smell like Capitano Riva?"

As I spoke, a sound of music rang through the smitten house—Delilah was touching the archlute I had noticed in her parlour. The piece she played was Adelaide, delightfully familiar, and never have I heard it thrilled with a touch more silver-tongued. The chords seemed richer and more responsive than ever before, and on that autumnal afternoon the refrain seemed a reverberance of spiritual things. It is a melody of appealing significance and clustering embroidery, now rendered with a poetic appreciation that gave it a sense wholly new. I realised, as never before, the possibility of thinking and speaking in music.

I was riveted by the charm of her expression. The true virtuoso wakes unimagined significance in old masterpieces, and I listened with delight to a technique that heightened the intimate light and shade. In that instant's rapture I forgot the inharmonies of the hour, and knew that memories long dreaming had awakened.

Suddenly I realised that she was revealing qualities within herself. The well-known romance assumed a startling import, and became Delilah's self-interpretation. Never before have I caught so distinctly the phantom chord that whispers from the soul of music. I felt that she was pleading, entreating with the voice of Adelaide, and that within its cantilena her heart was speaking. For the first time I learned what is meant by the Call of the Song, and asked myself if our fateful experiment might not be bearing me beyond the limitation of accustomed things. It was a mystical summons as distinct as any Vaini's mechanisms had ever produced, and I straightway went upstairs to the music-room.

I halted at sight of the minstrel seated against the tapestried wall, turned a little from me with the great lute ringing beneath her touch.

I halted at sight of the minstrel seated against

the tapestried wall, turned a little from me

with the great lute ringing beneath her touch.

In that instant's pause my eyes rested upon a large portrait of the Signora Cinquedea fancifully habited as the Biblical Delilah, in floating draperies, with bared throat, the woman of the Valley of Sorek whom Samson loved. And my fancy flew to those days when Baal-zebub, yet unconquered, descended to earth and walked in the Syrian moonlight with the beautiful daughters of men. The Testament dwells with recurrent emphasis upon those groves, beloved of Moloch, wherein danced the tawny girls and the darker Bedawi, the Philistines and Amalekites and bronzed women of the land of Cush. Whoever reads those brief paragraphs catches between the lines the flash of necklaces and tinkle of bangles and the rhythm of mountain-songs. They were playmates of demigods, those women with lithe arms and half-bared limbs, not kneeling, but erect, heedless of perturbations about death and heaven, content to take life as a fine coin stamped with a die we cannot change. The beat of harp-strings and whisper of flutes and pulse of timbrels thrills in our hearing. "Let us eat, drink, and love, for to-morrow we die," is the song of those women. And among them is Delilah, and at sight of the strong man, the smiter and slayer, she cries, "Surely thou art a son of Dagon, our God before whom we dance!" Whereat the strong man laughed and drew her to him, unresisting. My vision of the sun-land lasted but an instant—then the human Delilah stood before me with eyes intently fixed upon mine.

"Did he love you?" I asked, still half a-dream.

"No," answered the Signora Cinquedea, speaking I know not of whom; "he cared for none but himself."

This unexpected answer recalled me from Biblical ages. "How strange," she added, "that through my playing I heard your voice calling, 'Let us eat, drink, and love, for to-morrow we die!' But of whom did you speak when you asked, 'Did he love you?'

"Of your dead husband," I answered, embarrassed at the recollection of my fervent imaginings. "And as to whom were you answering?"

"Of Saverio, of course," she replied with flushed cheeks and very bright eyes. "Now I must go; Vaini awaits me, and I must tread my winepress alone. He seeks to thrust himself between me and you; but the time is coming when we shall remember his malice as a mere footnote to this tragedy. In pledge whereof take from me this little silver cup—less the cup than its engraved words, Amicizia i Fidelità." Then, swiftly placing her hands on my shoulders and raising herself, she whispered: "If the worst befall ... if in life a day comes when the threads now woven together are severed... call me, however softly, in your hour of need... and, living or dead, I will come. Addio; join me in the garden in an hour."

I stationed myself unnoticed at a rustic table in the Cinquedea garden, where the Penumbra had been placed behind a spreading myrtle and out of sight of the Professor. I listened unseen to Signora Cinquedea's frosty greeting of her visitor, and, in considering how fine an intellectual duel this salutation prefaced, remembered Orion Marblehead's familiar dictum wherein he summed up an observation upon the gentle sex: "A woman is bound to squeal if you bite hard enough." I knew that my former tutor could be depended on to bite to the bone.

The lady spoke first, in a voice that trembled. "Am I a dog," she exclaimed, "that I must come to your whistle?"

"I am told," replied Vaini with unruffled amiability, "that hell is poorly lighted. So too is the story of Saverio's murder; but I am about to turn on a flashlight before which all but the logic of facts will disappear."

Having assured myself that the Penumbra revolved accurately upon its centre of gravity, I noiselessly extended its antenna towards Delilah. I remember casting an admiring glance at our beautiful mechanism, whose spheres and ellipses were an illustration of Vaini's well-worn proposition that the realm of an idea may usually be defined by a geometric figure.

"To begin with," observed the Professor, rubbing his hands with bonhomie, "it has been shown that on the night of the crime you were impatient to get the maids upstairs to their attic. You told the cook and housemaid their noise in the kitchen disturbed you. Although the hour was not yet ten they withdrew, leaving you alone on the ground-floor. Was it your object to be able to admit your husband's assassin and guide him to his ambush?"

"All the world knows," answered the accused in a low furious voice, "that the assassin must have been hidden in the shop, and that his motive was a private vendetta. I never doubted he was brother to some girl Saverio had trifled with."

"Do you know the murderer's name?"

"As well ask me where the tides go, or what becomes of the stars at dawn."

"Suppose I call him Gennaro Riva?"

"You may suppose whatever foolishness you will."

"There are three death-shadows on the office wall. Shall we say that Scarafaggio was with him?"

"What has Count Scarafaggio to do with it?" cried the lady. "That is what you are here to explain. Is he your brother?"

"My foster-brother," she corrected hastily.

"Not your lover... as well?"

Delilah sprang to her feet and began pacing up and down with the elastic smoothness of a feline. Through the screen of myrtle branches I could see her face of pale sinister calm like the set features of sculpture. I, too, felt a rising anger at the cruel rudeness of this interrogatory.

"My instinct was right," pursued Vaini in a jeering banter, while the Penumbra suddenly began reflecting with feverish haste.

Has the fool blabbed again? I read at the end of a sentence.

"Your words are insulting," answered the Signora, resuming her seat. "I shall not discuss such things with you."

"Wild animals," pursued the Professor philosophically, "distinguish their own kind one from another at a distance by the scent. A house-dog knows the scent of his master and of his master's children. To the keen animal sense the kindred-blood is always the same. Now, will you discuss why Capitano Riva moves in a musk odour of his own, and whether it is due to heredity that your child has the same peculiarity?"

Delilah sat silent, and the Penumbra flashed the words: That musk-rat smell will ruin everything.

"Ten years ago," resumed Vaini, speaking with a spice of bravura, "you obliged Capitano Riva to fight a duel with your foster-brother. You made choice of the Captain because he is a formidable swordsman, which the Count is not. In a stormy interview you enjoined upon Riva to kill Scarafaggio, and that he did his best to merit the favours he subsequently received from you is proved by the dangerous sword-thrust he inflicted."

"Count Scarafaggio," interposed the lady, "had compromised my maid Agnese, who was young and pretty then."

"That is to say," remarked the Maestro, "you had surprised Scarafaggio and your maid in a compromising situation, which roused in you a jealousy that only blood could appease. Why did you not discharge Agnese?"

"That would have been giving her to Count Scarafaggio out of hand," replied the Signora coldly.

"You preferred to keep her by you, almost in durance, a mark for those poisoned arrows one woman knows how to make ready for another. Since the duel, you have incited four attempts upon Scarafaggio's life. That the Count still lives is due to the Camorra which he has paid to protect him."

"Has this anything to do with the murder?" asked Delilah scornfully.

"You promised Scarafaggio forgiveness," replied Vaini, "upon his aiding Riva in the attack on your husband. When that attack began, you opened the door and stood looking on till it was finished. And now," he added, lifting both arms in a frenzied gesture, "if the soul of the murdered man, from remote Infinity, can hear the summons of an earthly voice, I adjure him to give some token of the truth!"

I have now to record the most extraordinary phenomenon of all my tutor's experiments. The air suddenly tingled with electricity, and the reflector of the Penumbra, after flashing a brief sentence, was shattered like a mirror struck by a bullet. I saw the child Beato come running towards his mother, who rose with the cry of one in a spasm of pain, and at the same instant Beato fell headlong. The objects about me seemed reeling. Vaini stood gasping as though asphyxiated, the maid Agnese staggered and fled. Looking upon our marvellous apparatus, I saw that it was split, bent, and shivered out of all shape. What supernatural force, I wondered, had thus smitten it to atoms? The effect upon us who stood near resembled that of a moderate submarine explosion upon fish. Delilah lifted her boy to his feet, and Vaini came to me, his face grey with excitement.

"Are you hurt, Maestro?" I asked, as he cautiously raised the fragments of his invention.

"Hush!" he whispered, aghast at his own achievement.... "It was another voice... it was the murdered man speaking!"

We stood silent, spell-bound, gazing upon the debris of our failure. Then he gathered the riven and twisted parts and tossed them into a clump of oleander. Drawing me aside he said: "One word before I go. At the mandate of the Camorra, an order has been issued by the Court forbidding me to continue this investigation. That order will be served upon me this afternoon, probably accompanied by a police notice to leave Naples. But neither order touches you, and I think you can remain without much risk. Only be very careful that no one gets at you with a stiletto. I ask yea to stay because my heart is set upon solving the Cinquedea crime. There is now but one way to success—you must spend a few months in Naples and marry Saverio's widow."

"Vaini," I interrupted angrily, "I have stood a great deal of nonsense, but this—"

"Have you no pride in your work?" retorted the Professor, taking my hand in his and regarding me with a smile of intelligent persuasion. "Is yours the shallow nature that recoils before a pebble in the way? Would you stoop to folly at the instant of success? No, I have a presentiment that next month you will rejoin me at the Villa, bringing tidings of great joy."

I had been far from pleased with my tutor's interrogatory, which was brutal in method and unfair in its stratagems. I felt sincerely sorry for the accused woman, and more than ever doubted her guilt. Having lingered a moment to regain my composure, I presently perceived that Vaini had gone, Beato been comforted and dismissed, and Delilah...

Before me, at a little distance, amid the ground flame of jasmines and virgin lilies, was Delilah, kneeling upon a garden bench, her hands lightly clasped, her auburn hair turned golden in that dazzling sunlight. She was clad in a sang-dieu crimson gown, against which her half-bared arms gleamed like silver, and I divined what fires ran in the veins of that splendid body. The Italian sunshine, like a shaft from the sun-god's quiver, laid its radiance on her face, and her look of silent adoration might have seemed an unconscious recurrence to the pagan worship of the sun. Once she threw her white arms out in passionate entreaty towards the freedom yonder, and tears glistened in her eyes. High upon the wall a thread of water issued from a marble lion's mouth, falling into a basin with the music of fairy bells. My throat was suddenly dry, my eyes curiously moist, and a swift impulse drew me towards this woman who stood alone, with all the world against her. In what field, I wondered, were her thoughts; and a voice within me answered, "It is November, winter draws on, the birds are still, the roses dead. What if a winter rose should bloom, and some stray love-bird sing in December!"

Once she threw her white arms out in passionate entreaty

towards the freedom yonder, and tears glistened in her eyes.

I stood thus gazing, as lost perhaps in my musings as she in hers. The lurid tragedy wherein she moved, however guiltless, was outlined before me. Was it for nothing that we had been thus suddenly and strangely drawn together, or could we awake and keep the crystal of our dream unshattered? Was I stretching forth eager hands only to clutch a shadow—only to remember the magnetic summons of her music with the vague regret of a kiss that ended in a tear?

Suddenly she beheld me, and rising, stood against the jade background of a cluster of laurel—a Daphne recalled from the laurel into life. The garden wall behind her was festooned with Spanish moss and columbine, and there were wild flower stains of amethyst on the greensward. The breath of June was on the lips of November, and I knew that it was the dreaming time of day. With a delicious air of ease and security, she beckoned me, and in suave Italian fashion said, "I always think of you as you came to me in my distress with hands overflowing with roses. You called them Toujours ou Jamais. A moment ago I was alone with my day-dream—that with to-morrow's sunset you and I might go—pour toujours over the rim of the world."

"Are day-dreams wiser," I asked, "than their kindred of the night?"

Lightly, without answering, Delilah slipped her arm through mine, and I looked into the amber sunlight of her eyes as we strayed down the long garden walk together.

THE following day I found on my breakfast-table a note from Delilah asking me to call that afternoon at three. I knew she would receive me upstairs in the music-room, and, having several unfinished observations to complete in the curiosity shop, I timed my arrival for two o'clock. Agnese admitted me, and, having done so, stepped out upon the portico and glanced up and down the quiet street. It flashed upon me that my unexpected arrival disconcerted some arrangement—that some one was expected in anticipation of my visit whose purpose might not be to my advantage. I shuddered to remember what had awaited Cinquedea beneath that roof three weeks before.

I had been but a moment alone, when a well-dressed and distinguished-looking stranger entered and closed the shop-door behind him. He bowed with courtly grace, and asked the favour of a moment's conversation. "Perhaps you do not know me," he began, with frank good nature.

"On the contrary. If I am not mistaken, I saw you here a week ago: you are Chief of the Neapolitan Police."

"We look alike," he answered, with a deprecating wave of the hand. "The fact is, I am Chief of the Neapolitan Camorra. Not that I would do you mischief—quite the reverse," he added reassuringly; "in token whereof behold this watch:" and he displayed Vaini's stolen chronometer.

"That watch," I said, "belongs to Professor Vaini. He told me it had been... lost, in the office of the Chief of Police."

"The Chief of Police," echoed my visitor with disgust, "is a man without a soul. He richly deserves to lose this, and I have brought it to be returned to its owner. I am sure you will not forget my honorarium?"

"Certainly not," I assented; "tell me how much it is to be."

"I am about to do you a far greater service," he continued, taking a pinch of snuff, "than the return of this watch. If you linger in this house, or in Naples, and continue in this miserable murder coil, something disagreeable will befall. Your life is secure, but you might suddenly be transported to a remote fastness in the Apennines, where you would remain—the blessed saints alone can say how long—till interest in the Cinquedea crime had ended. Two personages whom you have bitterly angered, Riva and Scarafaggio, are not far hence with a couple of bravos. Without me," he added, flecking a grain of snuff from his waistcoat, "you would not leave this house alive to-day, though you might leave it manacled to-night for some unknown destination."

"But I am working with the authority and protection of the police," I ejaculated in astonishment.

"Signore," replied the Italian, lifting his hand as one who takes an oath, "it is but yesterday the Chief of Police exclaimed in my hearing of you and Vaini that he would no longer risk his immortal soul in the service of men who talk with Satan."

"I have no money about me," I said, remembering the meagre few hundred francs in my purse. "But give me the watch and tell me the amount of your fee, and you shall have my cheque before night."

"I never doubted," said my visitor with whole-hearted graciousness, "that your promise is as good as that of the Camorra. You will send me ten thousand francs, and you shall not be disturbed to-day by those who seek to do you mischief. But by to-morrow noon you must have left Naples."

"I am here," I observed coolly, "as the adviser of Signora Cinquedea, and shall remain—unless she bids me go."

The Chief of the Camorra returned his snuff-box to a side-pocket and eyed me with swift comprehension. "Or unless she goes with you," he murmured with an insinuating smile. Then rising, he made me a bow and departed.

TO be again in Delilah's presence gave me a curious thrill. On

the floor sat Beato, and before him a basket of

fruit—bunches of grapes, dusk-red apples, and great yellow

pears. He was a handsome boy, wild-faced as his mother, but

darker—almost as dark as Capitano Riva. Mirthful, yet

wistful-eyed as a little faun, he needed only the panther skin

and tipped ears to seem a boy-faun revelling amid the votive

fruit of classic altars.

"I am glad you have come," said the faun's mother, motioning to a scat beside her. "We will smoke a little, and talk of pleasant things. For a day or two you have looked weary. Your studies with Vaini will age you before your time."

"Our studies," I replied, "are a realm I fain would never leave—a realm of shaded calm, of spirit calling to spirit across the twilight of centuries, of altitudes yet unmeasured."

"One might think you were talking of Rosamond's bower," interrupted the lady, with malicious mirth. "But I remember that would be no more to you than the murmur of a sea we have read of but never sailed. Tell me frankly, when this foul storm is past, what shall you do, or whither go?"

"You will need repose when that day comes," I answered; "and I am as heartily weary as you can be of everything here. Suppose we spend a couple of months on the upper Nile, amid the silence of the Pharaohs. We should possess the gift that kings know not—a life wholly our own."

Delilah looked at me in a way that said things.

"Take heed," she exclaimed, with a rippling laugh. "Love, left uncared for, takes the first comer by the hand. What if in this forsaken place that fate were yours!"

"I should lead him," I replied, "to your roof-garden, and pluck for him the last amorous roses of summer."

"Saying silly things blisters the tongue," retorted the lady. "And yet," she added, stretching her arms as if to embrace the universe, "to think of gathering that rare bouquet ... to look beyond the palm-trees and the centuries upon the altar of Osiris... to learn more of life than the taste of its shining dust... to gather something better than driftwood... to dig the burnt gold of poppies that bloomed in Cleopatra's garden... to watch the stars through fragrant, palpitating nights... the heart almost ceases beating for rapture. Would it not seem," she whispered, laying a magnetic hand on mine, "like a kiss of the gods?"

"It would be a kiss of Delilah," I gravely assented.

At that instant Agnese entered and handed her mistress a telegram, and placed what was left of our Penumbra on the table. I moved discreetly away to gaze on the long breakers rolling upon the silver beach, in silver silence. Overhead, athwart the ceiling, a wavering line of light flickered its reflection of the sunshine in the garden tank below, And I remembered the fiery writing on the wall, and wondered if some fresh tragedy were imminent.

When I again turned Agnese had gone, and Delilah's eyes had narrowed to a look of feline cunning. I was conscious that the passing instants were swift and sinister. I could 'read, without the Penumbra, that in the back of her brain lay a resolve like a coiled serpent about to strike. I divined the substance of her telegram as though its brief phrase had been before me. Obviously it was a caution from Riva and Scarafaggio that I had taken such measures as precluded their attack. They naturally attributed to me the Camorra's order to halt. Moreover, they returned the shapeless fabric of our Penumbra, whose wreck had doubtless been found by the gardener near the place where I had been seen standing, and which had been given them for examination. They had naturally stamped it with the character of an infernal machine such as intimates of Satan would employ.

The colour had faded from her sun-browned face, and in a voice of deadly quietness she said, "I, who am alone in a world of wrongdoers, wish to question you as to the experiment you and Vaini have applied to the murder of my husband, and of which I was the object yesterday."

"It holds a splendid secret," I observed with genial good-humour; "the Professor calls it the Terror of the Unknown."

"It becomes you to talk of secrets," she cried, choking with anger, "you who have sought to pry into a secret that involved fame and reputation. Men have been stabbed to death for less."

"You speak now of your dead husband," I interrupted, catching her malice. "I speak less of him than of your friend Vaini, whom I have ordered out of Naples."

I watched her with rising admiration. With her classic face and athletic poise and gladiator's courage, she seemed in her danger one of those about to die, who to this day salute Caesar in the arena of life.

"Every hour for a fortnight past," she continued, "as I tasted the dregs of a misery men drink from and go mad, I have asked myself-are you for or against me? You who came as a friend," she cried, smiting the shattered Penumbra, "brought this that was to deliver me into the snare of the fowler. Every time that I move to save myself an outstretched hand that is yours motions me back. It was this devilish thing that, as Vaini plied me with wicked questions, took my vitality and numbed my thoughts— this that bewitched Agnese and flung Beato to the ground."

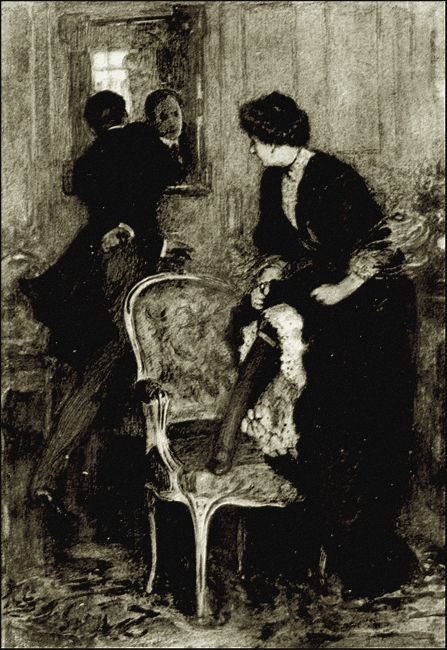

There was a faint sound at the closed door behind me, and, knowing Italian ways, I instinctively wheeled, half-drawing a revolver. Was it merely Agnese eavesdropping, or had Riva and Scarafaggio stolen a march upon the Camorra?

In a Venetian mirror I beheld the reflection of Saverio's wife, and saw her rest a foot upon a chair, lift the black skirt, and take something from her gaiter. Then, with right hand uplifted, she sprang noiselessly upon me, and, turning, I caught her wrist and bent it so violently kick that the fingers relaxed and a shining blade fell to the floor.

In a Venetian mirror I beheld the reflection of Saverio's

wife, and saw her rest a foot upon a chair, lift the black

skirt, and take something from her gaiter.

In that instant I awoke from my hallucination, stabbed to the heart by the stiletto which had not touched me.

A silence followed wherein many things crumbled away. A yellow light shone in Delilah's lynx eyes, her lips quivering as though she breathed a curse. And the odd fancy came lo me that if indeed the souls of those who have deeply loved or passionately hated seek one another at the last, her spirit would strive, as the final act of Earth, to lay a malediction upon mine.

VAINI'S cloister garden grows more poetically beautiful each year. Its Toujours ou Jamais roses, flowering in December, have covered its walls with riotous bloom. The antique marbles wherewith the master adorned its inglenooks have Income garlanded with violets.

Across the translucence of Italian atmosphere, a ruby amber veil is laid at every Ottobrata upon the hill-sides, tingeing them with the red gold of Imperial Rome that fades, as shadows lengthen, to the mediaeval calm of silver twilight. And beyond the sky-swung tracery of olive branches, beyond the sunset's face of flame, beyond last year's bird-call, I remember the sinister task Vaini set me, and listen to its whisper of subtle and significant things.

The Cloister Garden

TO this day it is not officially known who killed Saverio, the

trial having been abandoned "for want of evidence."

Doubtless the truth was traced upon the Penumbra at the moment when its mechanism—strained beyond inherent limitations and smitten by some force of Nature which resents the puny investigation of man—flew into atoms. The Professor occasionally alluded to this failure as the supreme disappointment of his life, and solemnly declared that, in hands less maladroit than mine, the possible would have been overstepped.

Here, in this Villa Sirena, which in life was his delight, are preserved those contrivances and time-stained volumes of curious lore which were his implements—symbols of life's untiring and fruitless quest for light and happiness and peace.

In Vaini's orange-grove, at the head of a long straight walk, stands the marble statue of Apollo which I bought at the sate of Cinquedea's collection and gave the Professor in memento of our experiment. Ages have mellowed it to a rich old ivory.

In Vaini's orange-grove, at the head of a long

straight walk, stands the marble statue of Apollo

which I bought at the sate of Cinquedea's collection.

The sun-god stands lightly poised, nude, an athlete fresh from the bath, statuesquely meditative, keeping the secret of the Cinquedea crime, and still bearing at the knee a faint dark stain where one who came red-handed from the murder groped softly by in the dark. The figure holds a seven-stringed lyre, touching a string in symphony with each elegiac phrase. For the sun-god is speaking with the thrilling cadence of the Spartan flutes as one that delivers some heroic utterance, intent, self-centred, masterful, not distraught with a thousand things. It is less the figure of a god than a type of the antique mind. It possesses the gift of divine youth, and is telling of the singers of songs that still live, of the makers of things that endure—deathless and superb—to this day. Behind the eloquent silence of his phrase ring the notes the Greeks employed to accent the spoken word—from the high contralto of transcendent joy and triumph to the deeps of suffering and death. Whoever listens, hears an accent of that intense concentration which throughout the classic life reflected itself in every achievement, making the examples bequeathed to us immortal. About this image still gleams the light that shone upon the spears of Marathon. Is it too much to say that the human heart of all ages is the lyre whose strings the sun-god thrills? And standing thus in the sunshine, in the delight of the sapphire blue, in the midst of the laurel he loved, and filling the air with his song-craft, that figure reminds me how widespread and lasting has been the worship of the sun, call we the sun-god Zeus, or Baal, or Moloch, or Apollo, or Amon-Ra, from Cleopatra presenting the new-born Cesarion to Osiris, to the Blackfoot squaw that lifts her infant to the benediction of the rising sun.

When, in this land of summer, the summer dies, I walk in Vaini's garden and pause to look upon that silent yet eloquent statue—and to remember Delilah.

I think of her as she appeared that sunny afternoon in her garden, kneeling with beautiful face uplifted and transfigured. And before me, as I write, is the little silver goblet she gave me that day, bearing its fateful sarcasm, Amicizia è Fedelità.

One evening, five years after the Cinquedea crime, walking thus amid the orange-trees, I became suddenly conscious of a haunting, fleeting, twilight presence, and, turning to one beside me, cried, "Delilah is dead!"

A week later I went to Naples, and called upon the curato who had spiritually attended her at the last.

It is a Neapolitan superstition that dying people see things. Even the elect are not wholly alone, and many a saint has beheld Satan peeping at the window. "In the sunshine there lurks a shadow—athwart the shuttered casement there steals a gleam of light. It is thus, Signore," murmured the little old priest, "we know that something waits and beckons."

"Was Scarafaggio brother, foster-brother, or lover?" I asked.

"Cosa vuole, what would you? Upon the Sacrosanto I know not—nor yet the manner of Saverio's death."

"Its manner," I said, "was plain as the crust in your soup. Delilah incited Riva and Scarafaggio, stationed them in the room, and when the attack commenced, crept back and looked on. And to think that between those two men there was such jealous hate that each would rather have spared Saverio and stabbed the other!"

"You seem to have known them well," observed the little Padre, lifting his faded eyes to mine with a smile. "Perhaps you knew Delilah very well also?"

"She cut the acquaintance short," I answered drily—"as women sometimes do."

"Prom me she would hear nothing," observed the gentle curato after a pause—"nothing—being half a pagan; yet, when the burden of earth fell away... perhaps her soul flew fair!"

— William Waldorf Astor.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.