RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

DURING the past few years I have been several times questioned as to the circumstances of my acquaintance with Professor Vaini, whose tragic end was described in a previous number of this Magazine. Till now I have hesitated to speak of events with which I was associated, through regard for the susceptibility of those whom they chiefly concerned. But now that all save I have passed away, there seems no indiscretion in making known Vaini's remarkable discovery, whereof he was won't to say that it had once been given him to tread very near the footsteps of the gods.

In venturing back into the sunshine of my youthful days, let me begin by saying that a search for the keys which unlock doors in antiquity has been, through many years, the fascinating occupation of my leisure hours. Had I the art to weave a love story, the slender outline of this narrative might be graced and enlivened. But with a view to reach the most accurate record of things which happened thirty five years ago, I am about to dictate my recollection of them to a typewriter, without pause or interruption.

AT Rome, in the month of November 1869, I was received as a

student by Professor Vaini, and spent a couple of hours daily

with him in his rooms at the Trinità dei Monti. When I first knew

him, Vaini was forty-five years old—a handsome man, of

graceful manner, which rarely passed beyond a formal courtesy. He

possessed wide literary knowledge, and had devoted a dozen years

to the study of scientific subjects in their occult bearing upon

modern humanity. In those days whoever entered the Papal dominion

passed within the repose and remoteness of a bygone century. Prom

out its monk's hood the mediaeval face of Popish Rome looked

forth grey and indomitable. In intellectual bias my instructor

was nowise at variance with the pagan shadowland of his

surroundings. He had an unexpressed, albeit conscious, disdain

for modern ways, though I came to know him as one who sought the

latest discovered altitudes of critical research. He wrote and

spoke French, German, and Spanish, and had translated the Arabic

writings upon transmigration of Ormès and Almodoro. As an

experimental chemist he discovered the composition of the

inimitable poison of the Borgias. However softly he spoke, he

underlined his thought, ami I have never known a man who so

intuitively divined a mystical significance. His talk was subtle

and illuminative, and the range and variety of his reading gave

his mind a brilliant insight. He seemed continually conscious of

that elusive world which is beyond our commonplace futility.

I was first attracted to Professor Vaini by reading of his experiments in suspended animation, wherein, having buried a man alive in the crypt of Santa Bibiena, he brought him forth after ten days, like Lazarus—a demonstration of fisting which in later years has frequently been surpassed. He was deeply read in the language and lore of the Greeks and Romans, and I soon perceived that the Olympians were more to him than abstract impersonations. He affirmed that the principle of divine life entering into a human body exists in the tradition of all ages, and that there is nothing more incredible in the Labours of Hercules than in the Plagues of Egypt; that the stories of the Ark and of the Argonauts are equally true, and that Aphrodite risen from foam is not more improbable than Lot's wife turned to salt.

It is an obvious fact that the results derived from our study in the equations of life are dependent upon the mood in which that study has been approached. With me the mood was one of rare delight in progressive analyses, and my eagerness unluckily aroused the Professor's displeasure. I mentioned one morning an observation made by me at Pompeii and confirmed at the Museum of Ghizeh, which, as the reader will see later on, was connected with a discovery upon which Vaini prided himself, and which to this day is known to few. It was largely for the purpose of obtaining his estimate of the occult arts that I had become his pupil. The circumstance which a year before had attracted my attention was that upon many mummy-cases, as well as within a few Greek painted tombs and on several Pompeian walls, there exist eccentric combinations and repetitions of colour, which, however seemingly careless, are seen upon closer scrutiny to have been deliberately designed. The famous pediment at the Temple of Isis was thus curiously bordered, and the same suggestion is apparent in the colouring of early Greek pottery. My observation had resolved itself into the theory that to the classic mind the harmonies of colour held no less significant inspiration than the accords of music.

One morning when we were seated in the Professor's study, he as usual at his big table strewn with a literary medley, an explanation of the method whereby we trace conceptions to and fro across the intellectual horizon presented the awaited opportunity.

"I am convinced," I said, following his thought, "that the drapery of at least four Pompeian figures tells a story that is but half hidden on the line of our horizon."

The Professor leaned back in his cane chair, and fixing his eyes upon the cabinet of minerals opposite, murmured in a subdued and altered voice, "What an odd idea!"

"It is not idle fancy," I replied. "You cannot have failed to observe in the decorations of Pompeii half-concealed fragments which are without relation to the more brilliant hues. If you have examined the so-called tomb of the garlands, at the Herculanean gate, you will have been struck by the unnatural colouring of the flowers."

"Chemical change of centuries," muttered the Professor.

"Moreover," added I, piqued at his indifference, "there is near the gate of Nola a vividly painted tablet with the inscription 'CESSIT COMMUNI PROPRIUM,' at a place where the public right ceased. Now, within the Nolan gate, at a closed street, is the same tablet, with identical colouring, but without the words. Herein, then, is revealed that to the classic mind a connection existed between thought and colour. That an idea may be figured in colour is not new, for it is as natural and obvious as that certain mental conditions are expressed by sound. As Sappho asks, 'What better than a birdsong tells the meaning of sunrise?' Or what Greek, looking upon the sea and watching its purple brighten to emerald in the shallows, could fail to divine its meaning?"

"And that meaning was?" ejaculated the Professor.

"That life, as well as Nature, has its harmonies."

To my astonishment, Vaini rose with angry irritation, and I have often wondered what was to follow. Before he could utter a word the door opened, and Facino, his boy-of-all-work, hastily entered, with a visitor's card pencil-marked Urgentissimo. My instructor abruptly withdrew to an adjoining room, where he remained such a long half-hour that I took my departure,—and felt profoundly relieved the following day when, on resuming our studies, no reference was made to my indiscretion.

A FORTNIGHT later, remaining one rainy day to lunch, I met ray

associate pupil, Orion Marblehead, of Massachusetts, a young man

three years older than myself, He had spent several winters in

Rome, and larded his observations upon the Eternal City with

expressive Americanisms. He was given to theorising upon things

ancient and modern, had much natural curiosity, and worshipped

success. He had a strong, clear-cut face, was a superior

chess-player, and possessed boundless self-confidence, which he

manifested in the frequent exclamation, "Hell couldn't catch me

if I had an hour's start." We had made an end of the exquisitely

dressed lobster salad, which, with biscuits and cheese, was the

sole refection our vegetarian tutor placed upon the table, and

were sipping black coffee served by Bonifacino, or "Facino," when

the Professor was again summoned by Monsignor Bella's coadjutor

to call upon him at his office. Mr. Marblehead and I lingered,

and he told me of our instructor's villa overlooking the Lake of

Nemi, where Madonna Cesarano—an old bourgeoise, widow of a

brigand of blessed memory and mother of Facino and of a daughter

named Hebe—kept house. This rural habitation, which was

Vaini's refuge in summer, was referred to as Villa Cesarano, or

by its more poetic appellation, Rocca di Falco.

"When I first went on a visit to Rocca," said Mr. Marblehead, hilariously terminating his description of the Cesarano family, "I made the widow a present of a flagon of Demerara rum, at which her face flushed with pleasure till I mistook it for sunset. She replenishes that flask with a half-and-half mixture of Vermouth and Cognac; and you can tell when the bottle is getting empty, because the old lady's snap oozes away in proportion. She will tell you about papa Cesarano, who used to clean the knives on her—as often as he was out of gaol."

My companion's frankness and piquant conversation moved me to hazard a question relative to the studies he was pursuing.

"On my twentieth birthday," he answered, lighting a cigaro shelto, "I resolved to taste neither meat nor drink till I had solved the central problem. I had previously constructed a method of traversing the whole sphere of human thought and examining its crannies and recesses. I had a craving for severe and simple principles, and having pledged myself to touch the highest point, my first resolve was to throw overboard all save knowledge undefiled. I had read Vaini's essay on the New Renaissance, and entered with enthusiasm upon his experiment of a substitution of classic for modern ideals. I said to him, 'I am all for the new, but a new which begins by returning to the old.' Before you have travelled far with the Professor you will find that he has an astounding disregard of probabilities.

"When I first listened to him I wondered that a man of such keen intellect should deliberately choose to spend his life in a labyrinth. But I soon learned that he has a pill for every earthquake, and is no more wide of the mark than a gilt-edged prophet is likely to be."

"Who is Monsignor Beltà?"

"That is one of our mysteries, one that Vaini never speaks of and that I know-little about. Our studies are not orthodox, and a hundred years ago the Holy Inquisition would have lodged us in St. Angelo. Now, hesitating to run us in, it has half a mind to run us out of the country. Then there are queer stories about Madonna Cesarano's daughter, Hebe, and her young man the Dogger. I suppose they include me, but bless you! give me an hour's start and Hell won't catch me!"'

Orion was seated with his back to the door, and while he spoke that door opened softly, and a young girl looked composedly in upon us, fixing the wistful splendour of her eyes upon me the stranger. Her face was of the classic type met with among Roman women; and so noiseless had been her approach, so velvet-shod her foot, that the instant's presentment of her tranquil beauty might have seemed less an actual presence than some fleeting ideal of one whom the Immortals loved. Then she drew back and the door closed. Mr. Marblehead noticed my momentary abstraction and glanced sharply back.

"A statuesque girl," I explained, "or rather that sense of romantic divination which haunts all Rome."

"A girl!" he ejaculated; then with an air of indifference added, "That's Hebe."

HALF an hour passed; Orion went his way, and the Professor did

not return. I stepped forth upon the terrace, where oleanders

grew, and whence one looked across a multitude of domes and

facades and pinnacles—a patchwork of roofs and balconies,

of chimneys and cupolas and belfries; of mighty ruined

fragments—over all which the Roman sunshine spread its

blazing splendour. But at that moment I gave small heed to

ancient Rome, for there before me, a watering-can in her hand,

was the girl who had gazed upon me through the half-open

door.

As she looked towards me now with hand-shadowed eyes, the divine delight in life leaped in her face—the same spontaneous gladness that sets the birds singing in springtime... at the season of blossoms and love.

As she looked towards me now with hand-shadowed eyes.

"Good morning," I said. "You are the Professor's Castellana, and I am his new pupil."

For an Italian girl her voice was singularly musical, and in that first brief meeting I was conscious that something in her nature, some subtle and mystical charm, made her separate and apart. Beneath that youthful calm what chords might vibrate, as yet but half attuned?

"You come each day," I said at parting, "to sprinkle the oleanders. Some morning I will pass again, to lean at ease and mark where poplars cast their slender lengthening shadow and listen with you to faint echoes of bygone days."

Her dark eyes looked golden in the noonday, like yellow catseyes, and as she smiled her teeth showed white as fresh-cut ivory. Yet across her face floated a swift tinge of tragic passion—as unfathomable as the depth that lurks between the rose leaves. "Signorino, come when you please," she answered simply: "I know you already... the Professor has told me of you. We shall not be too busy to listen, nor too dull to hear."

WEEK after week, through the silent December, my studies pursued their fascinating course. To fit my sightless eyes to the focus and perspective of those ancient times I was eager to explore, we entered upon an examination of that classic literature which is woven through Italian history. Vaini instructed me minutely in the mystical life of renowned men and women, teaching me to express concisely the outline of heroic careers, in the delineation of which, according to geometric rule, I became an adept. It grew clear to me that every situation in life may be depicted in a mathematical form, and that the development of this principle might be made to give the perfect semblance of individual character. Herein the Professor's faultless touch could indicate that unknown quantity which in every problem turns upon pure accident—a quantity Fate's caprice often delivers against us with tremendous effect, or rarely—when all other hope has failed—turns with forceful sarcasm in our favour. Leaving our demonstration of heroic ideals, I passed to the study of the Professor's method as applied to Natural phenomena.

One morning on arriving at Vaini's lodging I found in his study the girl Hebe Cesarano, dusting books and tidying the writing-table. I had twice spoken with her since our first meeting; and now—pausing in her occupation, and standing, against the background of veiled shadows—she began by informing me that my instructor was absent for the day.

"Gone to Rocca di Falco?" I queried. "He must need relaxation from his lurid chaos of thought. Even I begin to long for a glimpse of cornfields and the river, the smell of wild hyacinths, and a tint of reddening boughs."

"He is not there to-day," she answered; then, talking with suave Italian light and shade, she vaguely mentioned an importunate visitor.

I crossed the room, and looking in her face was startled at its pallor. "Who is this visitor?" I asked.

"Signorino, the name of Monsignor Beltà is unfamiliar to you; but it is as well known to Romans as the Holy Office itself. The ideal which the Church does not like is a crime. Whether the Monsignore aims at the Professor, or at Signor Orion, or at you or me, or at all,—who can say?"

"But what has the Holy Office to do with any of us?"

"You may well ask. It is like wondering what things exist beyond the horizon. In ancient days all roads led to Rome; in mediaeval centuries, between cursings and indulgences, they led to Paradise. Who dare say whither they lead now, if not to a convent for women and the Inquisition for men!"

I listened to her words with curious interest, puzzled to think what secret lurked within the span of this young life—a secret not so unfathomable but that Vaini had taken its depth.

My hesitation provoked her to speak the warning whose suggestion I had passed by.

"If you will accept advice," she ejaculated, "leave these musty riddles that are beyond the guessing of a youth, and go. Leave Rome. Craving after vast things makes people small; the Immortals were content to seem no more and no less than themselves."

In those dangerous days I was twenty-two, and no wiser than my age Hebe was eighteen, and it stung me to be lectured as a boy.

"Speaking of leaving," I ungraciously interrupted, "Signor Orion tells me you abruptly left the convent where you had been placed."

"Dio di mi Alma!" she exclaimed, with a careless laugh, "it was because one morning I wrote SACRAE DIANAE under a saintly image. Those words ring in my ears—like birds that sing although the day is dead."

"What can those words be to you?"

"The illustrissimo Professor tried to make me remember—an experiment that lasted months."

"What were you to remember?"

"Sacrae Dianae, of course, and her temple that used to be in the gardens at the foot of modern Nemi. He will show you its foundations, but I recall its marble colonnade, its statues and altars, even its processions—though, alas, the strings we touched are silent now."

"Hebe," I cried, "this splitting of ancient straws in our human tragedy has made you mad. What can you mean? What was Vaini's experiment?"

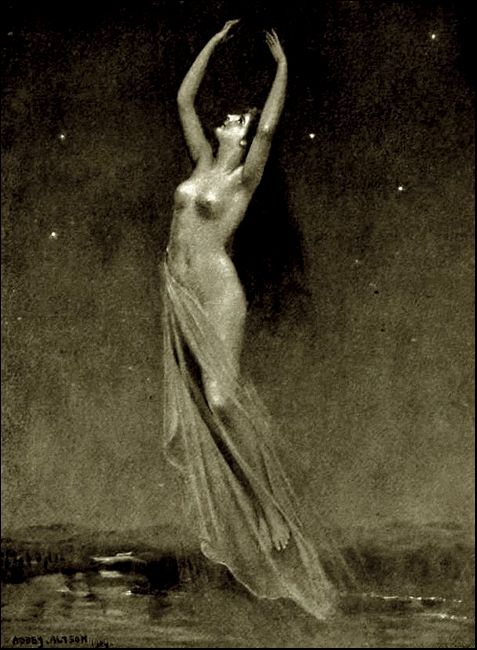

"He bade me fix my eyes upon yonder picture of the Grecian Hebe soaring towards Olympus, and alter long waiting questioned me, as though to measure life's come and go across the light and shade of places known in happier days."

"In happier days!"

"Yes: days when men and women lived near to the Immortals, who anointed them with genius and loved them as equals. When endowments made for eternity were not short-lived; when children were not born with the instinct consciousness that life must die; when the brilliants had not yet turned to glass."

Her eyes moistened as she spoke; and in asking myself what could be the life of one so singularly gifted and so strangely ill-starred, I became absorbed in my musing, till, presently turning to question further about the colonnades and altars and silent strings, I discovered that she had left the room unnoticed.

AT Christmas Professor Vaini invited his two pupils to spend a

day at Rocca di Falco. Orion Marblehead proposed that I should

lunch at his lodgings and thence drive with him to the villa. Our

luncheon was a substantial dinner of beef, montepulciano and

macaroni, for our instructor had not converted either of us to a

vegetarian diet.

"If you wish deeply crusted ideas," Mr. Marblehead remarked as we seated ourselves, "you should dine well and drink good wine."

I asked my companion if amid the originality of our studies he ever regretted what had been left behind.

"What did I leave?" he ejaculated: "modern academic shows, a sick self-consciousness of nerves, and a high-pressure race for wealth."

I turned our conversation to the girl, Hebe Cesarano, and it was with surprise and displeasure that I listened to his careless declaration of a purpose to take her from Rome in July upon the completion of his studies.

"No carrying on the war without animals of that description," he explained; "and I consider Hebe a very produceable young woman,—she has a forearm of remarkable heft, and I once saw her run up Monte Cavo without turning a hair. She has been living rather on the loose, and somewhere in the background there is a man she is pledged to marry. His name is Gardullo Mangicane, and he is a Dogger. I intend to take her away, because she is lost in her present surroundings—not to mention that the Inquisition puts women into convents for less cause than she has given. Marry her? Oh yes, with mutual option of separation, of course. The fact is, a wife is awkward: she dives under when wanted, and comes to the surface when you wish her away. Marriage is no longer up to date; however, I have my points from start to finish, and when I want a thing I get there."

Half an hour later we were seated in an old-fashioned vettura, he smoking his favourite cigaro shelto, and I thinking of Hebe and of the things the future was ripening. The Campagna lay in the drowse of a mid-winter afternoon, that seemed the long-drawn calm of centuries. Upon the horizon was the lustrous line of the sea. At that hour, when shadows are longest, the sunset laid a coralline flush upon the Apennines, that faded to pale violet-blue. Till suddenly the twilight gathered, and behind us through the darkness gleamed the lights of Rome.

At the other side of Genzano we drew up near a house where Vaini welcomed us, and where presently Madonna Cesarano spread a supper of trout and eggs. And Hebe was there, and her fifteen-year-old brother Facino, who, with a maid-of-all-work, Madonna designated la famiglia.

I was down betimes next morning, summoned by Facino to coffee and rolls. Madonna had long been astir, and greeted me with a smile. She was glad I had slept well; she herself had slept badly—something was on her mind: she had no patience with people who did not pay their debts, and she owed a scudo for refilling the flask Signor Orion had given her—I probably had not a scudo to spare—oh, mille grazie! Thus for the first time I saw Madonna's favourite play-throwing flowers to herself, as the Italians call it—the frequent compliment, the occasional scudo.

Here in summer Vaini lived, in scholarly retirement, embroidering upon old models. It was a quaint house, its pavement smoothed by tread of long-departed feet. A dining-room, ante-camera and the Professor's study occupied the ground floor, and half a dozen bedrooms were above. Its materials bore token of having been previously adapted to some other building, carved marble fragments being mortared in with untrimmed blocks. It had pillars that wore a monastic appearance, as of some cloister vineyard, and a battered sarcophagus received the water of a tiny stream that overflowed with ceaseless trickling splash. From tiled roof to garden gate, Time had stained and mellowed its walls to rusty orange-red, giving it thus the benediction of that graceful age which marks Italian houses.

Coffee disposed of, the Professor and Orion went botanising on Monte Cavo, whilst I remained to study botany with Hebe in her wild-rose garden. As we strolled forth down the hillside, I beheld for the first time the Lake of Nemi, the Speculem Dianae, on whose placid surface, as the morning wore on, the silvery aquamarine deepened to amethyst. About it hung a melancholy charm, a sense of mystery and isolation, which not even the brilliant sunshine could dispel. Opposite rose the battlemented village of Nemi, as rugged as the rock-piled monasteries and towered castles of the Abruzzi. Behind were cliffs now faintly purpling with profusion of wild anemones, on whose scarred face one reads the silent yet eloquent story of heroic idylls,—archaic sunrise, Roman day, and mediaeval twilight.

The Lake of Nemi.

This to the artist of life, the singer, the sweet musician—

She whose voice is musical as the beat of receding oars.

She whispers, "Here is my mirror, my painted veil;

From its deep, O Lover, watching the sun-kissed ripple.

May rise the remembered image you seek."

The scar-faced crag is young in the light of morning.

Beneath it the lakeside thrills with melody;

The gods listen to rustic pipe and lute-string,

Laughing, as nearer the shepherdess ventures,—

Till the arms of the amorous faun are about her!

What is life, if when we are young we love not?

Or what burden is heavier than a heart grown cold?

The fugitive days come and go while we linger—

Beloved, take the most flowery way to thy fate,

Ere the God-bestowed gift of dreamless sleep be thine.

—Translation into English of Hebe Cesarano's rendering in

Italian of the colour-language expressed on the painted Roman

tile.

"In such a scene," I cried, turning to Hebe, "who does not

envy the antique life spent wholly out of doors?"

Beside us, as we strayed, the russet lichen shone fine as velvet, and I took Hebe's hand in mine and made her feel its softness. How beautifully she held herself, and with what charming grace she listened, and how exquisite the Roman sounded when she spoke! Her words expressed an infinite longing for the Spring—for its daffodils and amaranths, for the lustre of its sunshine and the love-philter of its fragrant shade. Here was her wild-rose garden, and in that enchanting stillness we walked an hour up and down the little pergola heaped with wistaria vines that laid fantastic flickering shadows at our feet.

"Is it true, Hebe," I asked, "that you are descended from a Roman girl whom in early Christian centuries Romulus Augustulus loved, and whose cupbearer she was?"

"My father said so, Signorino, and so his father said,—it is a story thus handed down for fifteen hundred years."

"Mr. Marblehead tells me you will leave Rome with him next summer—as his cupbearer."

"For shame, Signorino!"

"But he adds that you are pledged to marry another."

"Possibly, Signorino."

"You have confided to me that the Holy Office has a watch upon you."

"Alas, Signorino!"

"And that some mysterious and perhaps tragic tie unites your imagination with a vanished age."

"Which you do not believe, Signorino."

"Povera ragazza, you are abundantly provided with sources of unhappiness."

"Signorino, will you show me a way out of them?"

"Tell me first how you found a way in."

Instead of answering, the girl fixed her eyes with abhorrence upon a young man wearing a chasseur costume who stood at the end of the path. Turning without a word, she left me and walked back the way we had come. I instinctively knew the stranger, in his Papalino brigand uniform, to be Hebe's betrothed, Gardullo Mangicane. He was a perfect Apollo—in pigskin—having the mark of the beast in his sombre-eyed, weather-beaten face. His glance followed Hebe's retreating figure; then, looking at me with the furtive scrutiny of a cunning animal, he lifted his hand in grave salutation and sauntered carelessly away.

As midday drew near, I returned to the Villa, and coming into its darkened vestibule beheld Hebe before a table filling a porcelain vase with roses and fine leaves; and standing thus amid crimson flowers that seemed the setting of her golden age, she looked so magically beautiful that in the witchery of that shaded moment the world might have taken her for a poet's creation, as elusive, yet as enchanting, as the strange memories she loved. Years after, I begged that trifling vase of Vaini; and now each Maytime, when the perfume of Italy touches the air, I fill it with great roses and fine leaves and place it far from the sunshine, where in an hour's retrospect I breathe anew the scent of Hebe's garden, and hand in hand walk once again with haunting memories.

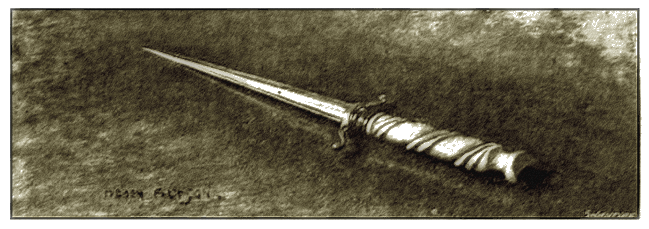

ONE Sunday morning, some weeks later, when the suave days of April tempted me to hours of exercise or idleness on the Campagna, I was sketching at Castel dei Pazzi, five miles from Rome. Vaini had cautioned me to take a revolver on my rambles, as the sheepdogs are fierce and many; but neither he nor I nor Orion possessed such a weapon, and in Papal days the purchase of firearms was discouraged. But in the Professor's table drawer lay an ivory-handled stiletto with a slender shining blade, and this he bade me take on my excursions.

"Better than nothing," he said, with a laugh,—"whether against mongrels with two legs or four."

Whilst putting the finishing touches to my sketch, I became instinctively conscious of an unseen presence. Turning abruptly, I beheld Gardullo Mangicane standing a few paces behind, and my surprise at this stealthy approach was such that my hand dropped to the slender-bladed stiletto. He perceived the movement, smiled, and carelessly wished me good-morning.

"This is an intrusion," he murmured; "yet it is but for a moment, and you will not refuse a word of advice. I wish," he added with malicious intention, "to ask your opinion of the girl I am to marry—la bella Cesarano."

"What should I have to say about her?" I exclaimed.

"Much," he answered, with a show of snarling temper,—"you that know her so well. I begin to suspect she loves elsewhere. Other men, look you, whistle and their girl comes: at sight of me at Nemi she started, and left not only me—but you."

"Why, then, do you wed her?"

"Because I gave my promise to her dying father of blessed memory,—alas, dear man, he died as poor as a Spaniard. What of that against my pledged word? Let it pass too that I should be justified in objecting to the influence and example of the illustrissimo Professor, who spends his time (and hers) in studies all sensible men condemn, or of your dissolute companion, who avows his purpose to corrupt her. But who shall say she is not more imminently menaced from another quarter?"

"That other quarter," I assented, replacing my colours and brushes, "being, of course, a return to the convent. So you are in no haste to set the wedding-bells ringing!"

An Italian's face darkens curiously in moments of anger, and a sinister shadow gathered now upon the Cacciatore's visage. "Do you think," he cried, "that I will see the girl taken from me? My redress is swift and easy. You presume to taunt,—and a voice to which you shall be made to listen will answer."

I rose and looked him steadfastly in the eyes. "La bella Cesarano, as you call her," I said, dwelling upon the name, "has already spoken, and what she said pleases me. I have heard enough from you,—may I soon hear the voice to which I shall be made to listen?" And, waving a careless defiance, I walked away.

It was my intention, on going to Vaini's the following day, to tell him of my meeting with Gardullo. But I perceived an unusual preoccupation in his curt buongiorno, and knew something impended. Before him lay a Roman tile, and pointing to it: "Let me begin," he said, as I seated myself, "by congratulating you upon having detected the principle of ancient colour-language, of which, to my amazement, you spoke some months ago. I believe its knowledge to be limited to half a dozen men. At that moment I was not disposed to discuss so technical a subject with an amateur, but now, circumstances connected with it and involving us all, oblige me to put you on your guard. The Papal Government does not share our passion for the occult, and my experiments have incurred displeasure. I may be summoned before the Holy Office and ordered to leave Rome, in which event my papers will perhaps be destroyed. With them might perish this painted tile, which is the material demonstration of the only Secret of Olympus man's ingenuity has surprised. You cannot be seriously involved, therefore I wish to entrust it to your keeping, together with my elucidation of its meaning."

"But, Maestro," I interrupted, startled at his words, "make your escape while you may, and leave the rest with me."

"Suspected, watched, and without a passport, I should not go far," observed Vaini; "moreover the attempt would be an avowal of wrong. To ignorant eyes this object conveys nothing. In your portfolio its translation would pass unnoticed. I commend them both to your greatest care."

So saying, the Professor placed in my hands a slightly broken Roman tile and a sheet of paper covered with his minute handwriting. The tile is of terra cotta, ten inches by six, and half an inch thick. At that moment I bestowed upon it only a hasty inspection, but subsequently it was often examined by me during Professor Vaini's lifetime, and now, after thirty-four years, acting as his literary executor, I give to the world its facsimile [see frontispiece] and his exposition of its conjectured meaning translated by me from Italian into English.

"I found this tile," he said, "ten years ago in a trench I was authorised to sink across the site of the Temple of Diana in the so-called gardens beside the Lake of Nemi. Its design represents, as you see, a golden vessel filled with flowers, suspended against an intricate background. At that time I had progressed little farther in colour-language than you have done, but recognised in this a marvellous specimen. A consultation with three of my confrères in Berlin achieved no more than to satisfy us all that it is a poem relating to the Lake of Nemi, which, as every one knows, was sacred to Diana. Here and there a word could be conjectured, through comparison with the half-dozen clue fragments which are all that have been deciphered since the discovery was first made in the time of Cosimo dei Medici.

"Its meaning might have remained unknown had it not been revealed to me under extraordinary circumstances. You may be aware that two years ago, having detected in the girl Hebe Cesarano a mind marvellously receptive of occult phenomena, and a familiar knowledge of ancient times which, however elusive, is always original and accurate, I commenced with her a series of mesmeric exercises intended to recover this shadowy association. The result alternated between much failure and an occasional luminous remembrance. I was about to abandon the experiment, when it occurred to me to direct her mesmerised intelligence upon this tile. To my wonder she read it at sight and evidently from memory. Neither I nor any one can explain this, nor can she—when not in a mesmeric condition—discern any meaning in its design. Through various tests the fact remains that, when her faculties are specially roused and applied, she possesses a curious power of recalling incidents that happened many centuries ago. So much for Hebe Cesarano.

"Now, no man will doubt that certain colours produce special and invariable impressions upon the mind. From this simple perception the ancients elaborated the significance of particular blendings and juxtapositions. A remote antiquity recognised that human emotion is reflected and expressed in the aspect of natural things. The changing face of clouds—the crystalline line of the horizon—the flush of dawn—the sapphire of the sea—opalescent tints upon the mountain—the statuesqueness of a splendid tree—an emerald meadow, asphodel strewn—a wave leaping in the sunshine—these and many like were the stigmata, the brandmarks upon which they fixed a distinct and universal meaning. To the Greeks, colour interpreted the profoundest human emotion. The beauty of the scenes they loved inspired them with a lyric note, and herein they perceived a motive as tender and intense as human voice. They believed that far in advance of them the Immortals, when they walked upon earth, understood that in form and colour lies a mystical expression of the heart of things. What wonder that upon a foundation thus gifted and inspired—seeing intuitively that everything gracious and refined has its perspective—the priests and poets and musicians developed and perfected a colour-language in whose subtle diction they wove a gamut of limitless expression! So enduring was their work that across the wreck of the ancient world it survived through the ages of crusading chivalry in heraldic blazonments and bannerets and distinctive costume."

I lost not a moment in transferring the tile to my apartment, where, pushing aside a wardrobe in my bedroom and raising the carpet, I removed two tiles from the floor, leaving a space into which I laid my charge. The midday gun at St. Angelo marked the hour as I finished, and with its sound came a tap at my sitting-room door.

Without waiting an answer, two men crossed its threshold— one a cleric, with the suave and unctuous manner inseparable from the Roman priest, the other a police official in civilian dress. A rough-looking fellow stood in the hall in reserve, had I proved troublesome; but this I was far from doing. Personally I had nothing more serious to anticipate than an order to leave Rome. I was obviously to be interrogated with a view to coaxing or coercing from me some damaging admissions about Vaini and the others. A hundred and fifty years earlier the recipient of a summons from the Holy Office would not have listened to it with composure. As recently as the middle eighteenth century there were forcible methods of persuasion. But in the reign of Pius IX. the faggots were cold, the thumbscrews rusted, the scabbard empty.

A few words explained that the Holy Office wished information which I could give; and upon my assurance that everything I knew was at its disposal, we descended to a closed carriage. As we drove away I noticed a man loitering on the opposite side of the piazza with a cloak drawn round him, and under the shadow of his soft broad hat I recognised Gardullo Mangicane. We drove in silence to the Via St. Ufizio, where, shown into the room of a subordinate secretary, I was invited to give my name and age, and to state whether I had any pecuniary means of support. I answered I had none. I was further required to exhibit such articles as were in my pockets, to show that I carried no weapon. Luckily Vaini's stiletto was in my table drawer with the sketching materials. These brief formalities disposed of, I was led up a circular flight of stone stairs to a door where an official waited, by whom I was conducted into the presence of a small man, who, having risen from his writing-table, was walking leisurely to and fro with his hands behind him. This was Monsignor Beltà. He turned as I entered, and eyed me with keen steel-grey eyes, whilst taking a pinch of snuff. I noticed a small-pox mark over his right brow, and observed his habit of fingering the border of his soutane with thumb and forefinger.

He motioned me to a chair, seated himself, and for ten minutes plied me with rapid questions. Then he paused, took another pinch of snuff, and reflectively rubbed his soutane as though verifying its texture.

"This Professor Vaini," he continued, "with whom you say you study literature, is a man of sinister fame. How came you to hear his name?—who sent you to him?"

"My confirmation teacher in New York was by birth an Italian—a schoolmate and friend of Vaini."

"Tell me exactly the nature of your studies."

"I seek the truth. I wish to know great lives. I pursue Nature, because it is purer than man and more beautiful than woman."

"You have a fellow-student, of whose morals I receive bad reports. He openly avows the intention to abduct a Roman girl —Hebe Cesarano."

"Monsignore, my own morals are above suspicion, but I dare not vouch for those of my friends."

"Young man!" he exclaimed angrily, "take heed to your answers: there is a persiflage about them must instantly lie corrected—by yourself or by me. As to the girl, she is compromised in reputation with your fellow-student; she is an adept or disciple of Vaini's necromantic hallucinations; she is also betrothed to an excellent man, an officer in the Cacciatori. Now, what is she to you?"

"Monsignore, she has promised to be a sister to me."

"I have a great mind to give you and your sister thirty days al segreto."

"Monsignore! All that lightning to kill a mosquito!"

"Here's a last chance to save yourself. Conjurers, wizards, and such folk are not taken seriously in our time. But there are political jugglers who unsettle the mind and the faith. As you hope for Paradise, have you ever seen among Vaini's private books anything of a revolutionary character?'

"Monsignore, he possesses a volume entitled Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies."

"Young man, you are an impudent fool. Had you been wise, you would have known that to be friends with me is more profitable than to be the dupe of a charlatan and the lover of a half-crazed girl. Begone—and sin no more. I shall keep an eye upon you, and at the slightest indiscretion...."

IT was two o'clock when I stood again in the Via St. Ufizio,

free—and wiping from my brow the moisture of that anxious

half-hour. To ascertain if I were followed, I walked to an

unfrequented street near by, hastened down it, then faced about.

Had the Dogger skulked at my heels, I should in that moment's

excitement have been capable of doing him a mischief; but there

was no one in sight. Vaini's lodging was doubtless under

surveillance, but the greater his danger the more urgent that he

be warned. I sprang into a passing fiacre and drove to Trinità

dei Monti. The Professor's study was empty, and so, after

knocking, I found his bedroom. I inferred that he had been

summoned at the same time as myself, and was doubtless at that

moment in the presence of Monsignor Bella. And Hebe,—the

hall door opened, and in came Hebe, having heard my step from

her own room. I felt aggravated at the unconcern with which

she listened to my breathless recital, till abruptly I spoke

of what I conceived to be her own danger.

With gentle sadness she answered: "My only danger from the Holy Office is that which has befallen many women—to be taken to a convent and there remain. You may trust Gardullo to see to it that I am not thus removed from his reach."

Then, shaken by a sudden gust of passion, she exclaimed, with face in a crimson blaze: "Do you know why Gardullo wishes to marry me?—I am to be sold to his patron, the Prince of Messina. They have both dared tell me so, and offer me a palace."

How those great deep tragic eyes flashed as she added: "They are loathsome to me, one as the other. I am afraid of the illustrissimo Professor, and as for Signor Orion—he is too wise. You alone, Signorino, have been good. You care for me a little, though you have not said so. Hush! do not speak. I know what you would say. Is not silence the language of Divino Amore?"

I was startled and confused at the utterance of an emotion I had not suspected. Then the intense look faded and her eyes filled with tears.

"Oh," she sobbed, "I am so unhappy!" and at the words, heedlessly, our hands met. "What is the day worth if we always labour? Let us give our life to calm. Let us go away together," she whispered, in a voice like cadenced music. "Come, no matter whither, so it be where none can find us; come, ere youth be spent and our hearts grown heavy, and I will love you with the pagan love—for love's own sake."

Our hands had met; and how often in after years, walking through beautiful solitudes and amid the scent of flowers and the song of birds remembering Hebe—how often have I asked myself, would it have been well for us if that handclasp had been for life?

I read the proud courage in her face, and found in myself heroic self-restraint to answer, "It would be foolhardy in you, Hebe, and wrong in me."

"Will you leave me to Gardullo?" she cried, seeing I dared not look my temptress in the eyes, her face so close to mine that as she spoke the soft black hair brushed against me.

The word stung me to fury. I had about me a dozen louis d'or and a French bank-note for a thousand francs, which I pressed into her hand. I dared not trust myself to linger. I was twenty-two, and before me stood a splendid being of life and love.

"Escape," I ejaculated, "at your own time and in your own way."

Then, turning my face from that delirious temptation, I rushed from the room. Never before had I realised what magnanimous courage it may require to run away.

DURING the week which ensued we were left unmolested. We had all, however, become so nervous and unsettled that study was discontinued, and Mr. Marblehead agreed with me that it would be to our tutor's peace of mind if we both left Rome. The ill-will of the authorities might relax towards the Professor if his pupils withdrew from the Papal dominion. I therefore obtained the official visa to my passport, and called for a few thousand francs at my bankers' preparatory to a summer in the Alps. Vaini had already betaken himself to his rural retirement, and thither Orion and I went for a day to take leave of him—and of Hebe.

We alighted at Rocca di Falco at the Ave Maria. Supper was immediately served, and we spent an hour in desultory conversation upon the existing political situation of Italy—little thinking that at that moment (May 1870) the Papal Government had but four months to live.

The Professor retired early, and Mr. Marblehead and I went out for a few minutes' contemplation of the stars and the sombre outline of the hills. I remember that the night was one of great darkness, to which, coming from the light of the dining-room, it was some moments before our eyes became accustomed. The new moon, Diana's slender crescent, was rising, and cast a faint shimmer upon Nemi. We walked in silence a few moments through the grove, when suddenly Orion, laying his hand lightly about my shoulder, said, "You and I have been good friends, and now we are about to part, perhaps never to meet again. In bidding you goodbye I wish to take you into my confidence—for to-morrow evening, by this time, I shall have disappeared."

"You will have disappeared?" I repeated in surprise.

"Yes, but not alone. Hebe Cesarano is coming with me."

The sting which those words inflicted is fresh and keen in my remembrance to this day. Rarely has a spoken word dealt me such pain. Had Hebe's declaration to me been mere deception? or, failing other means of escape from her betrothed and his patron, had she yielded at last to my companion's persuasion? I listened in a dull and angry stupor while he talked on.

"Yessir, I have never failed,—failure is against Nature, for Nature does not fail. Man fails only when he has not mastered the ways of Nature, or when he does not know how to handle his tools. I have had enough of Vaini and the psycho-psychical. Hebe has agreed to let down the gang-plank and ferry me to Elysium. I tell you she is a white alley, and I intend to make her live up to her label. After the honeymoon I shall put her on the stage, and the Dogger shall lurk around as the heavy villain. If he misbehaves I will knock him bald-headed. I shall make them both play up. I wanted to say all this right now, because by this time to-morrow—Well, give me an hour's start, and—"

I did not hear the completion of the familiar phrase. While Orion spoke I became conscious, for all the blackness of the night, of a figure stealthily following from tree to tree. Suddenly I turned from my companion and rushed upon the intruder. But, at my first movement, whoever it was bounded away out of sight.

"What did you see?" inquired Mr. Marblehead.

"I saw Gardullo Mangicane," I answered; and bidding him good-night, sought the long wakeful hours I knew awaited me.

I was out next morning at an early hour, seeking in the refreshment of sunrise shadows and sunrise silence to efface something of the bitterness of the fevered night. It was a day of untroubled calm, and looking across the lake to the lilac-woven drapery covering the hillside, the eye roved over vistas of transcendent loveliness. A voluptuous breath of spring was in the air, for we were touching the heart of Maytime. The broadening day mellowed the silhouette of Monte Cavo, and where sunshine fell on lichen-stained wall and crumbling terrace the moss became luminous as gold in ancient tapestry. A filmy wood-smoke rose above Nemi, the humming-bees were tuning in the orchard, and I remember the air was sweet with odour of wild strawberries. Before me lay Diana's mirror, motionless and blue-green as shot silk, typical to my fancy of those springs and fountains of antiquity into which I had been dipping. Diana's silver mirror!... that may have reflected the goddess standing knee-deep in its shallows—that men declare keeps her reflected image to this day. For the Immortals were always in their best attire, even when ungirdled for the bath, and their statuesque nudity is never immodest nor their raiment insufficient, though it be but a leafing vine.

Before me, at the water's edge, grew a willow of such brilliant green that it seemed almost yellow—the golden yellow of a flask of Episcopio. Beside it rose a great rock, and I halted in amaze at sight of the figure which stood beyond it, knee-deep, with uplifted arms as though to salute the sunrising. It was Diana in the living form of Hebe Cesarano, her beautiful white body looking like ivory—yet less a living woman than a charmed semblance. She did not see me hidden behind the rock in the shelter of which she had approached the water and beside which her clothing lay. Beneath the lustre of the bending willow she seemed a caryatide—a masterpiece of Grecian curves—a morsel for the gods. I lingered a breathless moment, and whit man with love of woman in his blood will blame me! Here was the habit of the nude of ancient times that rose unabashed from the sea—that now bending launched like an out-bound prow and swam away into deep water—and with it departed the magic of a beauty which ever since, it seems to me, the living world has lost.

Thus was it once given me to behold a poet's dream, and that fugitive vision has remained with me through life. I have often revisited Nemi, and lingered in the wild-rose garden, and walked by the lake shore at the place where, on that morning, Hebe stood. The daffodils still scatter the hillside with their shower of gold. Against the rocks are the same trailing tapestries of moss, each at sunrise tipped with glistening dew. I walk through scenes delightfully familiar—yet removed from me by an immeasurable distance. A pulse of sadness floats across their tender beauty, when I remember the presence that once was their poetic charm. I shall never again behold her; but now Time, with a thrill akin to rich accords of music, weaves for me an exquisite witchery about those happy days.

I HAD promised to remain with Vaini until the following

morning, and we spent several hours together in his study taking

a retrospective survey of many philosophical subjects. He showed

me his portfolio filled with original gleanings and scientific

queries and curious problems in those fascinating realms of

speculation wherein he was a master. Since his death that

portfolio is in my possession, and on many a quiet afternoon I

turn over its neat manuscript pacquets, which, in their variety

and brilliancy, bear token to the range and activity of their

author's mind.

After our midday repast of bean soup and fried sardines I went to reconnoitre the grove where, on the previous evening, I had missed tapping Gardullo's head with my stick. "He will skulk among these trees again to-night," I thought, examining the ground and its approaches. Then I remembered—"what matter if he come?—it can only be in quest of Hebe, and this evening she and Orion will be posting northward miles away."

I had no heart to talk with Hebe, nor had I aught further to say to Mr. Marblehead. I thought to leave them to their own contrivings, and so strolled to a little trellised arbour wreathed with wild grape-vines. The thought of Gardullo's spying presence led me to meditate upon the shapes and phantoms and fleeting spectres with which the ancients peopled their world. The Greeks and Romans can rarely have felt themselves wholly alone, for though they heard not the footfall....

Footfall! Yes, it was beside me, and there stood Hebe Cesarano, fixing me with great questioning eyes.

I motioned her to a seat. For nearly an hour we talked, and often I seek to remember the unselfish and endearing things then said. It was a last long rapturous leave-taking—for ever. Such farewells are rarely quite dry-eyed; but in those early days I knew nothing of such matters, and it was with astonishment I beheld Hebe's eyes dimmed with tears. I drew her close—to see; and perhaps hereafter the impulse of that wayward instant will be forgiven, since for both it was a kiss that meant good-bye. "Hebe," I asked, "shall we ever lose our way in Paradise, or will the path always be clear, think you, that leads to those we love?"

She pointed to the sky overhead, where some brilliant birds were winging their swift undeviating course. "The birds will lead us to one another," she answered, "for we know that love follows their flight."

And with the word she sprang into the sunshine—the suave sunshine that softens so many griefs—and was gone.

ALL that afternoon I was oppressed with consciousness of

impending danger. When supper-time came, Vaini and Madonna

Cesarano were puzzled at the simultaneous disappearance of Orion

Marblehead, Hebe and Facino. I was not so much surprised, and

held my peace. The Professor and I sat down to his favourite

risotto, followed by a fritata; and as the evening

was chilly I persuaded him to drink a measure of Albano. He had

devoted the afternoon to compiling the description of an

excavation made in April under the cellar of a house on the Via

Goito, where he penetrated into the crypt within which in Roman

days were entombed alive the Vestals who had sinned. It is

written with his forceful brevity, and I never pass the Ministero

delle Finanze, built some years later on that locality, without

thinking of the gruesome substructure it covers. The crypt was

intact, and has never since been visited; and Vaini dwells upon

the ghastly horror which came over him as he descended the flight

of stone steps down which those unhappy women went to their

living tomb.

Presently we heard some one at the outer door. "It must be Orion or Hebe," exclaimed Vaini and Madonna Cesarano, and I followed them to see. The night was inky black. In the courtyard stood Facino, with a woman's dress and bonnet over his arm. He had been persuaded by his sister, so he said, to clothe himself at dark in one of her gowns, tie her bonnet and veil about his head, and seat himself beside Orion in the travelling carriage which waited near Genzano. They had not driven a mile when his identity was discovered; and then—

"And then?" we asked.

Then the Signore had caught him by the throat, dragged him out of the carriage, and kicked him across the road. "Beata Vergine! how the Americano swore!"

"But why were you in the carriage? and where is Hebe?" screamed his mother, shaking him furiously.

It was a family dispute, and discretion prompted me to stroll through the grove.

What happened immediately thereafter? There was a man's sudden outcry. Vaini, Madonna, and Facino came running to me, and together we cautiously made our way to where—flat on his back, with outstretched arms—lay Gardullo Mangicane, speechless, fast losing consciousness, his chasseur jacket open and the blood oozing from a stab in his throat. He had been violently stilettoed, and whoever dealt the blow had vanished as by enchantment.

Who but Hebe could have wounded him?—in self defence, of course.

Lanterns were brought and the leisurely police came from Genzano. There was much talking and many futile questions were asked and repeated.

"But what," still cried Madonna Cesarano, "has become of Hebe?"

"Whom the gods love die hard," whispered the Professor. "Hebe has stabbed him and thrown herself into the lake."

Madonna heard, and filled the air with lamentation.

"Hebe dead? Gone!—no further than from dawn to sunrise, but for ever. Dead! Aye, passed through the gate that never closes, and climbed the blossomed steps."

Passed through the gate that never closes.

EARLY next morning we learned that Gardullo was not

dangerously hurt. He had soon recovered consciousness, his throat

had been dressed in a day or two he might be able to speak, and

then the truth would be known.

An hour later I bade Professor Vaini a grateful and affectionate farewell, drove to Rome for my luggage, and crossed the frontier of the Papal dominion that evening. A dozen years elapsed before I again beheld Italy.

MADONNA CESARANO sleeps in the graveyard of Ariccia. I saw her

once again, in 1883, the time-worn hands still busy, her hair

turned white as the wool she was spinning. Facino, grown

prodigiously fat, converted Rocca di Falco into an inn where,

keeping up the brigand traditions of the family, he fleeces the

sojourner.

More than once, in subsequent years, I spoke with Vaini about the events of that tragic evening. At first he declared Hebe's disappearance to be a case of suicide, affirming that her bones moulder in the depths of the lake. But on the last occasion I reverted to the subject he merely smiled and gazed out of the window with an amused expression.

IN the winter of 1895 I drove from Rome to Isola Farnese,

where an Etruscan tomb was to be opened. After its inspection I

lingered to look at the church. A little old padre in rusty gown

and berretta came out to salute me, in whose face was something

familiar. Where had I seen those faded steel-grey eyes, those

fine lips, and the small-pox mark on the right brow? It was

Monsignor Beltà, voluble and unctuous, and still fingering his

soutane. He was less favoured now with the gifts of Mammon, and

seemed pleased when I invited him to sit in my carriage while the

horses were harnessed, and share my luncheon of galantine and

Irroy brut.

Suddenly addressing him by name, I said, "Monsignor Beltà, you and I have met before."

He looked at me intently, without recognition.

"May 1870—Professor Vaini—Hebe Cesarano," I murmured, watching him with malicious pleasure.

The glass fell from his hand.

"I will be more merciful than you were with me," I added, "and ask only one question. What became of Hebe?"

"Signore, she was but a girl—not twenty; and you, a friend of the wizard, know that the Olympians were all in their prime when they vanished—not one grown old or deaf or blear-eyed or imbecile. This was because they had a finer instinct than we to discern the poetry in life's ending."

"But what has this to do with Hebe?"

There was a twinkle of amusement in the steel-grey eyes as he answered, "Since you wish me to speak seriously, was she not one of them, and could she do less than they?"

This persiflage was so little convincing, that when a year later accident guided me to the whereabouts of my former fellow-student, I wrote, presuming so far upon our acquaintance as to ask him the same question—what became of Hebe Cesarano? A week later I received the following extraordinary reply:—

Salem, Massachusetts,

April 13, 1896.

Dear Sir,—

Your letter reminds me that twenty-six years ago you were as tender as I on that beautiful psychological problem. I never doubted it was your kind thought placed her brother in my carriage. And at this time of day it seems rather cool to ask what became of Hebe, when no one can answer that question so well as yourself.

Yours very truly,

Orion Marblehead.

P.S.—How is your friend the Dogger?

IN the autumn of 1890, whilst traversing Eighth Avenue, in New

York, I observed a man beating his dog. As the animal ran away,

the man raised himself, and I recognised Gardullo Mangicane.

Beside his shop-door was the familiar red-and-white striped pole,

and the sign: "George Magician. Tonsorial Artist."

Thus was an Italian name Americanised, and thus had Hebe's fiancé become a thriving barber.

I paused before him, and said in Italian: "Judas, is that you?"

He glanced up with the old sinister look, recognised me, and rubbed his hands with fawning salutation.

"After twenty years," I said, "I am still in doubt as to the events of that evening. Have you ever discovered who attacked you?"

"Signorino," he answered, "if Paradise were opening before me and this were my last word upon earth, I would swear it was you struck me with a slender shining blade."

I turned on my heel, wondering what he and Mr. Marblehead could be thinking about. Not many days later I read this notice in the Express:—

"An Italian barber, named George Magician, living at 1754 Eighth Avenue, where he was much respected, lost his life yesterday while attempting to drown his dog in the Hudson River. Tying a cord round the animal's neck, and weighting it, Mr. Magician threw the dog from a boat, but in endeavouring to keep it under with a pole, overbalanced himself, fell overboard and was drowned. The dog escaped."

So perished the Dogger.

— William Waldorf Astor.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.