RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A YEAR ago, in Paris, my attention was called to the irregular cutting of the ruby I wear as a ring. The setting had become loose, and the stone being shown to the manager of the Maison Roque, he examined it with a minuteness that aroused my curiosity. In answer to a question he indicated certain characteristics in the shaping and disposition of its facets which might have escaped any but the expert eye, and spoke of what he declared to be well known among master diamond-cutters—that many antique gems bear mathematically expressed in the angle and proportion and conjunction of the figures which compose their surface, a date, a name, occasionally a word of philosophical import, which, if deciphered, proves the key to some weird enigma.

"Is it possible that some such phrase exists upon the face of my ruby?" I asked incredulously.

"There are a few Asiatics," was the answer, "who to this day practise a method of writing upon jade, lapis lazuli and cornelian, whereof the outlines shaped upon this ruby seem an exceptional specimen. The fact that such geometric symbols are rarely in modern use, is no proof that they have not existed for thousands of years." Then, as though piqued by a scepticism which may have accented my query, or perhaps restrained by professional discretion, the representative of the Maison Roque abruptly disclaimed more than the vaguest knowledge, and busied himself with my order.

There this odd matter might have rested, had it not been that last winter at Cairo, Monsieur Mégarde, the Curator of the Ghizeh Museum, evinced so extraordinary an interest in the aspect of my ruby that, placing the ring in his hand, I remarked, "It has been thought one of the message gems that have reached us from remote ages."

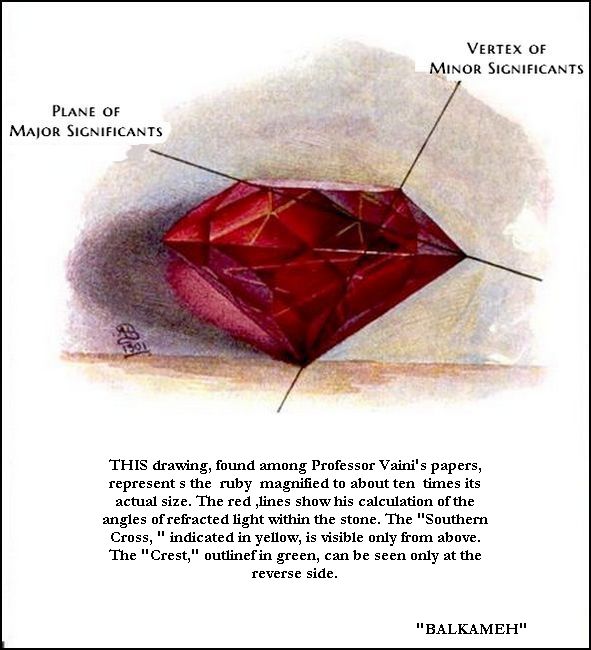

He scrutinised the stone intently, and asked that it might be left for comparison with the wax impressions of all the known message gems, of which the Museum possesses a collection. He returned it the following afternoon with the announcement that a careful examination enabled him to recognise the cutting as of Phoenician workmanship. "It bears," he said, "the mystical number of seven significants. Of these, five are said to be significants in sequence, but I can only conjecture the meaning of three."

———of Wisdom, to———

"The first," he added, "might be King, or Chief, or Prince."

"Prince of Wisdom," I ejaculated, "is suggestive of Solomon."

Monsieur Mégarde smiled at my haste as he replied, "There are two independent emblems, the upper of which, called the crest, is clearly the equivalent of Baal, and bears a resemblance to the fifth significant, which probably is some unfamiliar name beginning or ending with the Phoenician 'bal.'"

"And what," I inquired, "is the seventh?"

"The seventh," he answered, "is that conjunction of facets, emblematic of the astronomical group we call the Southern Cross, which is considered by the half-dozen Europeans who understand the meaning of significants to be the essential characteristic of the dream-stones of antiquity."

"And what may dream-stones be?"

"Every one knows," answered the curator, "that gems exert upon certain persons an almost supernatural influence. Individuals of exceptional sensibility—poets, musicians, students of occult science, often women of imaginative faculty—are intensely moved and even inspired by holding a great jewel for an hour in the hand. A 'dream-stone' does far more than kindle such emotions. It directs the thoughts of whoever has the receptive capacity along given lines, presenting a train of facts or ideas and transmitting thus through the ages, from mind to mind, a recital which is always the same, varying only as a piece of music may vary in the execution according to the skill or expression of different performers."

My interest was now as thoroughly aroused as it could be in a subject which seemed little less than absurd. I resolved, upon leaving Egypt, to visit Rome and place the ring in the hands of a lifelong friend, Professor Vaini, whose attainments as a master of occult science are universally known. He received me with the grave kindliness of old, insisted upon my sharing his vegetarian breakfast, and scrutinised my ring in silence. It seemed superfluous to make any explanation of its supposed character, so I limited my statement to the peculiarities in its cutting, upon which I begged his opinion, and, leaving the ring, returned to my hotel.

Three days later, a note from the Professor summoned me. I was startled at the change the interval had wrought in his appearance. He looked like one who has passed through a severe illness, and suddenly aged half a dozen years.

"I have done with your ring," he began abruptly. "It had been so many centuries unused as a medium of communication that its accumulated power is almost killing. The peculiarities to which you refer are significant angles, the most accurate form of inscription known to man, in the present case easily read and to be freely rendered as follows:

"THIS DREAM-STONE OF LOVE

THE PRINCE OF WISDOM TO BALKAMEH,

THE BEAUTIFUL, THE GLAD TIDINGS OF BAAL."

The Professor laid his hand thoughtfully upon a roll of manuscript. "While engaged in deciphering those significants," he said, "I took the ring to the window to calculate the angle at which the light is reflected through the stone from what are called its superior facets. Its contact exercised upon me an overmastering and not altogether agreeable effect. I feel so nervous and exhausted after the experience, that I am about to leave for Subiaco for a week's repose. I believe the ruby gave me its 'glad tidings' very fully, and I have spent an entire day in writing out the impression or series of pictures which flashed through my mind. I know not if I were asleep or awake during the hour the reverie lasted."

I thanked the Professor, took leave of him and on reaching my apartment read his manuscript twice with breathless interest. I publish it now, literally translated from his Italian, for the information of those few who know and love the curious arts. Having occupied two days of Professor Vaini's time, and obliged him to make a journey, I wrote him a day or two later in acknowledgment of his kindness, enclosing a cheque for ten thousand francs. I was inexpressibly shocked at receiving a reply from his secretary announcing the savant's death at Subiaco soon after his arrival. It was a case of collapse following upon interruption of the vital functions, as though, to use his words, "the brain had been struck by lightning."

IN the hundredth year of the Lion in Heaven, the bird Splendour of the Morning spread his wings, and mounted with tireless flight, saying to the Magicians in the realm of Sheba, "Declare ye unto the Queen that I salute her with the words, 'O Balkameh, thou art of perfect beauty.' Moreover, ye who understand the science of the seventh power, shall bid her know that the King whom soothsayers call Prince of Wisdom, and who is a refuge alike from storm and heat, awaits her." So at the voice of the bird the magicians rose to uncover their feet, and the daughters of music were silent.

At these words the Queen rejoiced, saying, "This is the messenger I have foreseen, who hath appeared in visions, who comprehends the meaning of the mystic number, who may not be caught with a net, neither fears the snare of the fowler." Wherefore she commanded that for the space of a year, through the coasts of Mariaba, provision of horses and camels be made, and gifts collected with guards and interpreters. Whereat the land of Sheba was glad, and the dreamer weaving a garland of dreams awoke, and far away a song was heard in the night, as of them going with pipes and filled with joy.

When the caravan assembled in number as the friends of one giving gifts, she whose name is Glad Tidings of Baal, who in Ethiopia is the King's daughter of the South, the glorious land, made sacrifice, having in her hand the sceptre of the powerful one, and on her finger the signet of authority, and before her the cedar-boughs which Baalim loves.

From Hebron Balkameh beheld Jerusalem, as she had wished to see it from the south, even from the direction of the land of Sheba, its yellow rock walls rising athwart the palms. Her company likewise remembered no more the burden of their journey; and at the morning light they looked across poppy-strewn wheat-fields, which make the young men cheerful, and vines that give new wine for the maids. Before them stood Zion, its crest touched as a burnished and glistening diadem, while poised upon outspread wings floated Splendour of the Morning, musing upon the secret of the presence and the dominion of the hills of dream.

Before the gate stood the King's bodyguard of six hundred lusty young men, whose delight is in arms. Whoso looks upon them—the imperturbable—silent and motionless, with short, glistening spears, thinks with compassion of such as shall come forth against them. Wherefore Balkameh smiled, saying, "I shall remember you as the radiantly calm." But when she asked that their chief officer might speak with her, their faces were troubled; nevertheless came Ahishar the singer, who being set over the household, held in his hand the backbone of a giant. When the Queen asked, "Art thou captain over these fearless ones?" he answered, "Their captain is Methusael, who is under the King's displeasure."

Then Balkameh besought that the young men might that day be feasted from her stores, to every one a loaf of bread, a piece of flesh, even the meat of fatlings with choice bones, and a flagon of wine, and baskets of first-ripe fruits.

All Jerusalem, even to the sons of the sorcerers, came forth, and the Queen cast silverlings by the way. First came the chief musician, and a great company making melody with mirth of tabrets, after whom followed maidens, dancing with tinkling feet. Last of all in his chariot appeared Solomon, followed by the elders, the scribes, and the prophets. He was of sunburnt complexion, with full flowing brown hair and beard, touched with a golden glow, and in his vigorous stature and strong hands and ruddy face one perceived the athlete and hunter. Yet more, as whoever considers a vineyard discerns the rich bunches of grapes, so in his meditative eye one reads the poet and lover of sun-flecked woods. He leaped to earth, coming to greet Balkameh with gracious words, for his words are full of marrow, and his sayings like wine well refined. Then, raising her dark hand to his brow, he fixed his gaze upon her, murmuring, "How sweet is the hand-touch of a beautiful stranger!"

Coming to greet Balkameh with gracious words.

Then she answered, "O topmost branch of the tree, may my everlasting home be near thine amid the stars." And speaking with kindling eyes and brilliant face aglow she was, as Baalim is my judge, as splendid as one of the shining ships of Tarshish. Then they stood together in the chariot and drove by the brook of the willows amid the throng of people, and were saluted by the kings of the shore and the kings of the mingled nations that dwell in the desert, till skirting the city they came to the House of Ivory in the midst of the garden, called of Eden, where formerly dwelt Pharaoh's daughter, one of the King's first wives.

Here Bathsheba advanced to receive her son's visitor. Behind her followed three men, sons of Rehob, King of Zobah, whom David took and whom he made attendants upon the women, wherefore, even now in their old age, the slaves of the palace laugh them to scorn. So when Solomon had touched Balkameh's head with the ointment of joy he withdrew, and Bathsheba conducted her through a vestibule, where against the wall was fixed the yellowing skeleton of Goliah with outstretched hands, each bent for a torch; thence entering the Queen's bedroom, they seated themselves upon the cushion-strewn floor. Between the windows, near an ivory bed, stood a table of mother of pearl with water jars and flagons, and in the midst of the room a brazier, over which, on winter evenings, Pharaoh's daughter had been wont to bend her dusky body. The ceiling whereof is inlaid with the words:

"The sword for men, the lute for women, the pen for slaves."

Bathsheba's glory hath faded since David beheld her upon Uriah's roof. Fat from gross eating, wrinkled for want of love, reduced by sloth to the care of parrots—for her the rainbow lieth in the retrospect. In her age she hath returned to the gods of her youth, Berith, whose temple is at Shechem, Chemosh, and the gods of Hamath, Arphad, and Sepharvaim, and she paints her body with gaudy stripes as often as she dances before their altars in the groves.

Through an aroma of burning spice Balkameh asked, "Tell me, composer of songs, who was the man led in chains by the gate?" Whereat Bathsheba replied, "Sister, that is Methusael, captain of the body-guard, sentenced to be sawn asunder, and led thus collar-bound before his fellows that he may taste his fate to the bone."

From room to room they walked, beholding the gifts of Pharaoh, of Hiram King of Tyre, and of the lords of Cyprus, till from the roof they gazed upon pastures with bubbling springs as pure as the wells of Salvation, and marked the sunshine where the humming-birds flit, and the shade where the woodpecker taps on the tree.

THE following morning came Abishag, the Ring's favourite wife,

whom Solomon loveth as the signet upon his hand, resting not in

his love but making great joy over her with voluptuous songs. Who

having been brought when a girl to David's death-bed, remained in

the palace when David was no more. In which days, when Solomon

was ever inditing, she came to his closet, and casting aside her

vestment, crept stealthily upon him, and laying a hand upon the

scroll looked laughing in his eyes, whispering, "The knowledge of

a woman, O Son of the Sun, is better than the wisdom of a man or

than the promises of prophets." Wherefore because she was

clean-limbed and magnificently poised, gave he her fair raiment

with jewels of price and dream gowns curiously woven to wear at

night, and dyed attire and badger-skin shoes to wear by day. She

also was a lover of groves, sacrificing in gardens and burning

incense upon altars, so that in high places the name of Baalim

was upon her lips.

Then spake the Queen. "Tell me, Lily of speech, why heard I through the night, and in the morning when the watchmen sang at sight of the break of day, the sobbing of one that has drunk of the cup of trembling?"

Whereto Abishag answered, "Bride whom the Gods desire, it is Adalia, a Bactrian, whom the King hath set here as a nail in a sure place." And with swift gesture she added, "I will strip her out of her clothes, and after her cheek-teeth are drawn, she shall be bound to a chariot-wheel with her feet in the ground, the wheel whereof shall be turned, and her body wrenched askew."

"Why is she set as a nail in a sure place?" murmured Balkameh.

While they were served with salted locusts and stuffed fish, Abishag wiped her lips, answering, "O subtle charmer of men, be it likewise given thee to snare the dragon and the unicorn. Know that this Bactrian was to wed Methusael, the captain of the guard, who lies in a dungeon where his skin cleaveth to the bone for scorpions. And because Adalia is stiff-necked and would not bow before the wishes of the King, neither listen to the voice of the interpreter, she hath been made like a young tree in the drought."

That day, when they came into the city of David, the King met them before the Temple. Beside him was Pharaoh's daughter, of lean, implacable face, her shaven head being covered with a wig. Whose voice is cold as the splash of a bucket when it falls in the well, neither takes she heed of aught save at a prospect of war, the thought whereof rejoices her. Near by stood also Guni, the Ethiopian, who draws the bow like a man and bestrides a horse like an Arab. Her delight is to paint her body ring-streaked, and to sit watching in the fire the shapes that come and go. Likewise, she observeth times and useth enchantments, knowing both male and female night monsters. Whose gods are Misroch, god of the Assyrians, Dagon the fish god, and Milcom whom the Hebrews call the abomination of Moab; but the greatest of all she declares to be Moloch. So the virgins that came with Pharaoh's daughter snuffed at Guni because her hair curls crisp, and Bathsheba sprinkled her, whereat Guni was wroth and hissed.

Balkameh beheld Millo, the house called the forest of Lebanon, the holy house and the sanctuary of strength, over which silver lay like dust. She saw also Solomon's wives, of whom not one hath her deep-set eyes and clear-cut face, and her bosom veiled with a veil. They passed before the molten sea and the flowers of lilies, till, beholding the burnt-offerings, the Queen gave to the priests a silver spit whereon to roast an ox. Likewise cast she into the chest wherein are cast the trespass money and the sin money which are the priests'.

And seeing the throng of prophets watching the great pot filled with seethe-pottage, she scattered drops of ointment upon the throne, breathing in silence a prayer to Baal, that her heart's desire be granted. Where also in the place of presentation of gifts she offered to Solomon gifts of Ophir gold, and they passed together into the inner court where is no noise, nor strident word, nor lamentation, but only a twittering of birds, like a voice of mirthful gladness, as it were the voice of the bridegroom and the bride.

But one of the prophets that watched the heaping-up of treasure, lifted his hands, saying: "The house that ye fill shall become an habitation of beasts, and the kings of Judaea shall be as wandering birds cast out of the nest. Verily Millo shall be full of doleful creatures, and in the Gate Beautiful shall satyrs dance. And as for the queens of the ends of the earth, that pray to winged spirits that their hearts' desire be granted, they shall be drunk with the sweet wine and strange water forbidden to prophets."

Then answered Solomon, his face red with wrath, "Shall a Prophet live for ever, and doth not Scripture declare that a presumptuous Prophet shall die? Thou art no better than one that would plunder the tomb of a king. Of a truth I will roll thee in the dust, making thee a gazing-stock, and a hook shall be put in thy nose and thou shalt be wiped as a serving-man wipeth a dish, turning it upside down."

Now this Prophet is the brother of Methusael.

So Balkameh returned to the House of Ivory to bathe in a cool tank in the midst of the garden of Eden. Here, in bygone days, in the midst of the seclusion she loved, came Pharaoh's daughter to listen to the musical inspiration of fountains by day, and read the message of the stars at night. Amid orange blossoms and wine-red oleanders, the trickling water touches the air with its whisper. Beneath clustering cypresses is a rock, where at noontide the sunshine spreads the moss with brilliance. A trellised way, heaped with roses, leads to the summer-house within whose roof is painted the Zodiac. Near by, for a jest, Pharaoh's daughter caused to be graven by her Egyptian graver on a fragment of wall little seen, the figure of Rameses holding the Hebrews in bondage by the hair of their head. Before whom also she set an image of Hathor, the giver of joy, with hands overflowing with amaranths, that when goddesses and kings' daughters meet, her hands may still be filled with the bloom of immortal days.

When Sheba went to salute the Prince of Wisdom in his house, they left the multitude in the court and ascended to the roof, whence the eye ranges to the almond grove by the pool of Siloam, where the daughters of pleasure dance. And Solomon laughed, saying: "Are not the side-lights often the happiest views?—from here David beheld Bathsheba!"

But she murmured, "Who can guess how far my fancy may stray, though I but walk to the nearest village? And because Baal hath granted me a corner-stone of knowledge have I learned to keep close to the simple things of life, lie they no profounder than the reflection of a star."

As she spoke, she started away from the wall, stumbling over a basket of scrolls which was the King's business for the day; for fluttering before her in the breeze hung the skin of a man of stature, slain by David's son Jonathan, who in life had on each hand six fingers and on each foot six toes. Nevertheless die-King bade her be seated, saying: "Let us dedicate an hour to calm," pointing as he spoke to the sky where, weaving its circling flight, floated the Hoopoo of the crimson wings, which dwells at the foot of the rainbow.

Then Balkameh blushed, for she is one to whom Splendour of the Morning hath spoken, saying: "For thee an adorable lover lingers in the darkness, in the depth of the garden, standing motionless and expectant as a phantom of the night!"

Her gaze rested upon a sundial, a figure of bronze with uplifted hands, the hand of Time and the hand of Destiny, the shadows whereof mark the lapse of day. Which was made by a Phoenician in the youthful semblance of Abishag when she cast aside her vestment to stand before the King. But Balkameh was jealous, because Abishag is beautiful, wherefore as Solomon turned aside she spat in the figure's face.

Then the King, seating himself near her, said: "I too love simple facts, nor am I content till I have tried to sound them as it were with line and plummet, even were they unfathomable as a ripple of the sea."

To which the Queen answered, "How shall we fare with our handcuffed hands and blinded eyes, if the wine of life become mixed with bitter water? Is anything really old, or wholly new?"

Whereat Solomon laughed, saying, "There are things which be old, yet always new—the lore of Egypt, which takes note of the flight of a bird; or where the river is deep knows what lies beneath the wave; or that enchanted circle, older than the Pyramids, at which wizards peep and mutter, wherein the earliest Pharaohs read the wisdom of superb repose."

After they had discoursed of many things, Balkameh asked, "Is a king a breeder of nettles in the way of a friend that seeketh a gift, or shall the door of hope be closed upon one whose heart is breaking?"

Then Solomon replied: "In every palace there be thieves waiting to penetrate the gold-worker's chamber. Nevertheless, say on."

The Queen continued: "There is a damsel called Adalia, to whom, if leave be granted, I will speak a word in season, bidding her hearken with her ears, that she may live and not die; and to me, if to none other, will she hearken, for her god is Baal-zebab. But first she and Methusael shall be set free to dwell at the House of Ivory, subject to my command."

Whereto the King answered: "O voice persuasive as the murmuring deep, be it done according to thy desire."

ON the following day when they sat at meat, loaves and

cracknels were set before them, and antelope collops roasted upon

coals, with quails, partridges, and fowls of the air. Likewise,

to each table an osier basket heaped with grapes and lumps of

figs and strings of pomegranates, and a cruse of honey fresh from

the comb. Then Solomon said: "Shall not the house give gifts to

its lord? Call therefore the chief musician, that we may drink

wine with a song."

So it was a day of feasting with laughter and clapping of hands. When the cupbearer had tasted, they drank to the lees, and no man's cup was empty, neither were the wine-cups suffered to stand full. The chief musician also drew from his dulcimer a haunting melody so deftly touched that each reverberant string gave back the meaning of his spoken word as he told of the enchanted groves where the singing of unseen damsels is heard, even of them that sing for joy of heart when kings come to glory in the sun's rising. Whereat Balkameh looked towards the King with a yellow light kindling her black eyes; but Bathsheba sat cold and silent, raking over the ashes of her youth.

Of a sudden the King cried, "Bring hither Adalia." Then, when she was set in their midst, he said: "Is not new wine found in the clustre, and shall she not dance?"

But Adalia answered, "Great King, they that descend into the pit cannot hope for truth; must I therefore go all my years in the bitterness of my soul?"

Yet, though her words were soft, one could read in her blanched face that her heart was as adamant. Nevertheless, her head was faint, and her eyes overflowing with anguish. Then, forasmuch as she would not dance, the young men took her away, mocking, to thrust her head downward in a wine-butt.

The young men took her away, mocking, to

thrust her head downward in a wine-butt.

Now Sheba whispered to the King: "Are lilies gathered with a scythe, or do men make love with an axe? Surely a maiden will not confess before this throng, but to me hath she hearkened with her ears. By Lucifer, she is more pleasant than a garden of cucumbers. She but feared a king's love might pass as the early dew. This night, in the Garden of Eden, when stars climb in the sky, she shall wait in the dark, in the midst of the clustre of palms, and by her tinkling silver bells and the balsam with which she anoints herself shall she be known."

The King drank till he beheld the hollow of his golden cup ere, smiling, he said: "Who wants a grander tent than the dome of the starlit sky?" And after a thoughtful pause he added, "Hath not the Hoopoo said, The wise man findeth his love in the dark?" Moreover, of his choicest treasure, even of the uncut gems that he wore, gave he Balkameh a ruby which had never been graved by the graver's tool, saying—as a demon laughed and murmured in his ear—"Take this red drop of my blood for a token that thou shall have thy heart's desire."

Then Sheba rose, and having cast aside her dream-gown of embroidered linen, stood before him, glistening in the torchlight, as one about to dance before the altar. And her waving hands and quivering finger-tips were like hovering butterflies. So as she danced barefoot up and down the alabaster pavement, her splendid body fine as the dash of spray that leaps where the salt wave strikes, they that looked were hushed, save for the sackbuts that filled the air with piping like the thrill of nightingales at night, till the soul of the listener whispered within him. And the Queen was as a proud standard-bearer that fainteth not, neither is trodden down. She seemed also an incarnation of the voluptuous South—a sinuous, pearl-girdled semblance of its suave and stalely palms—a vision of tropic birds and fleet-winged sails touched by an after-sunset glow. More than all, she was the type of that race of dancers and musicians for whom the stars delight to shine. Whoso beheld her knew that this is the breeze-blown dance wherein the maidens of Babylon exult in the groves of betrothal, as the dance of them that prepare for the nuptials they desire. Wherefore in her swaying Balkameh interpreted the mystical meaning of the amorous shafts with which at his rising and setting the Sun-god pierces the depth of his groves; or the reflection, as of gems bestowed by a lover, which at Tyre he lifts from the sea upon the sun-browned wall of his house.

She was the type of that race of dancers and

musicians for whom the stars delight to shine.

When the Queen, having made an end, put on again her dream-gown, a silence fell, like the hush that follows when the rhythm and emotion of prayer moisten the eyes. Till, as though touched by the hand of a listening god, a harpstring broke, whereby as she took her leave arid the air resounded with the acclaim of many voices, we knew that a fateful instant had passed. So Sheba returned to the Ivory House, in whose garden the King that night waited and watched, silent as break of day, while stars climbed in the sky, till in the midst of the clustre of palms he became aware that a woman stood in the darkness, and by the tinkling silver bells and the fragrance of oleander balsam he knew that it was Adalia.

When the days of the Queen's sojourn were fulfilled, she stood with her company before the King at the oak of weeping. And she interrupted the long salutation of the prophets, and, turning to the Pearl of Wisdom, said, "Let our farewell he brief. When lengthening shadows slant through the Garden of Eden— forget not Adalia. In the deepest copse of Mariaba, in the midst of overleaning palms, will I build a Bower of Remembrance, where on starlit evenings, after good-night or at break of day, before the bidding of good-morning the footsteps of thrilling memories shall rustle the leaves. Are there not things best understood in the darkness, and hath not the Hoopoo declared, A woman shall compass a man. Verily a woman's wit is no ill match for Solomon's wisdom. There be three wonderful riddles: the flight of a bird in the air, the course of a ship in the sea, and the way of a man with a maid. Now this was the way of a queen with a king—and this also, my adorable lover, thou comprehendest not. Farewell."

But to me, all the days of my life, whatever I see that is beautiful shall speak to me with thy voice. Yea, hereafter shall I care little for the blended meaning of the stars, if but a single point of radiance beckons me to thee.

Farewell! But to me, all the days of my life, whatever I

see that is beautiful shall speak to me with thy voice.

The long caravan wound down the hills, till looking back, Balkameh beheld the Temple sparkling in the sunset as a flame of triumph.

Then went the King into an high place, and with him were Jehosaphat, the recorder, and Benaiah, chief of the host. Thence his eyes followed the caravan till through the pink haze it faded and was lost in violet darks. But they that were near understood not why he laughed, murmuring: "to think I knew not! As though one could take from a woman her heart's delight, mocking her borrowed balsam and her ankles bound with another's silver bells! Is not a tiger-lily more splendid than an amaranth—albeit both be fair? The wise man is he who knows enough not to know too much, and this, subtle maker of riddles, is the way of a King with a Queen."

It was an afternoon when mere consciousness of life brought perfect peace. Time's tender touch mellowed the battlements with russet that flushed or darkened between sunshine and shade. Sweet scent of perfumed gardens bore pulses that thrilled like a thought of fair women. The mountains veiled with opalescent hues the secret of their solitude sublime. Beyond them a cloud caught the fugitive sparkle of day, seeming a last fading glimpse of the bird that for ever had flown—the splendour and joy of the morning. But to this hour no man can tell aught of Methusael or Adalia, nor into what land they went when they fled from the House of Ivory.

THIS singular narrative speaks with a precision in marked contrast to the looseness and verbiage of Oriental recitals, whether ancient or modern. Its statements are not at variance with historical fact, so far as known. Had it been deciphered from a papyrus, its intimate details would suggest that it might have been written by one in attendance upon the Queen. It alludes to Balkameh as still living, and to the events it records as having recently transpired. It is noticeable that at that remote period the things of Egypt were a measure of antiquity. The reference to the Temple as an edifice just completed points approximately to the year 985 b.c. Curious to remark, there are in it several slight inaccuracies such as a transient visitor, unfamiliar with the country, might make. Far more startling is the extraordinary intimation that Abishag was Solomon's first and favourite wife, and that the amorous phrases of his Song are an impassioned memorial of their love.

Professor Vaini's manuscript led me to the study of Phoenician civilisation and enterprise. In Solomon's time the South Arabian kingdom of Saba or Sabaea, or Sheba, now known as Arabia Felix, controlled the East African coast, and its colonists had not only occupied Abyssinia, but had penetrated as far as the gold mines of Mashona. The Somali district was known to ancient Egypt as the Land of Punt. Portuguese explorers of the Massapa mines note the resemblance between the native name "Afur" and the Biblical "Ophir." It was from here that Balkameh obtained her gold, of which, if the Jewish gold talent is rightly calculated at £5,475 her gift to Solomon must have amounted to over £600,000, The language and writing of Abyssinia indicate that it was peopled from South Arabia at a period of remote antiquity. Following upon this trace, the French explorer Arnaud discovered towards the middle of the nineteenth century the ruined walls and Temple of Mariaba, the royal city of Sheba, and obtained inscriptions of Phoenician derivation.

An element of uncertainty will always attach to the Abyssinian tradition that the Royal family of that kingdom, whereof Menelik is the present representative, descends from a son of the Queen of Sheba I have asked the opinion of Egyptologists, of Oriental scholars, and of eminent churchmen as to the existence of this child, and while the consensus of opinion rests upon inferential conclusions, there is in the surmise which attributes its paternity to Solomon nothing conflicting with our knowledge of the Prince of Wisdom.

I have frequently sought the confidence of the dream-stone by holding it for hours in meditative silence, but necessarily in vain. It is obviously unlikely that an unimaginative man of affairs could attune himself to mysteries so subtle and elusive. More than once I have invited a repetition of Professor Vaini's observations by offering to submit my ruby to the experiments of acquaintances whose sensitive mood might render them receptive subjects. On such occasions it has seemed an evident duty to mention the tragic fate of my Italian friend, to whom the "glad tidings of Baal" were as lightning. Then, to my chagrin, the listener's flashing interest invariably fades, and the dream-stone of Balkameh's love, which her lips may have touched and inspired—remains silent.

— William Waldorf Astor.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.