RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

IN the brief revival of classical archaeology at Naples which marked the reign of Murat it did not escape those who busied themselves with Pompeii and Herculaneum that many points of the bay, such as Bagnoli, Stabiae and Vico, gave indication of buried Roman houses. At Sorrento in 1830, while laying the foundations of a hotel, part of a villa was laid bare and wholly destroyed, its more important portion being under an adjacent monastery.

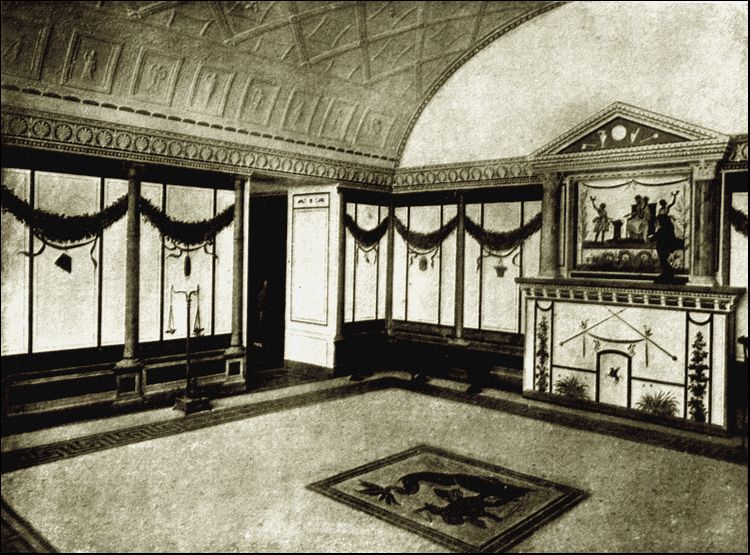

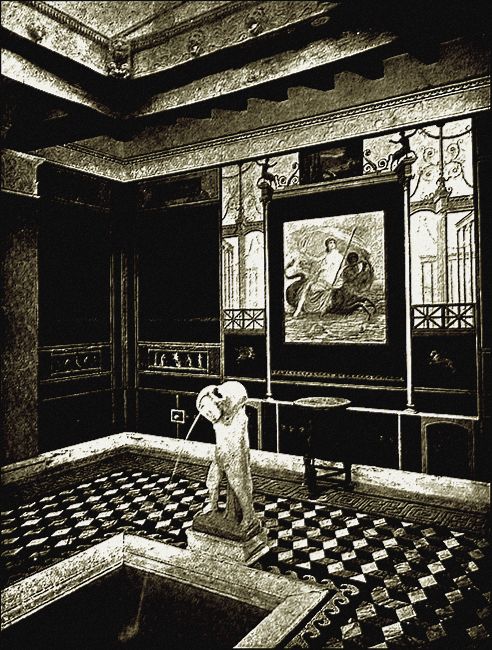

A few years ago, when Professor Vaini's villa passed to me, I removed that disused monastery and came upon an ancient construction. It was easy to trace the familiar outline—peristyle, atrium, tablinium or parlour, a cubiculum which had been the porter's lodge, and a flight of stone steps leading down to the dining-room, kitchen and wine cellar. The rear part, which must have included the bedrooms, had been obliterated in building the hotel. The house thus exposed had once been a large and luxurious residence that, left to a state of abandonment, had become filled with its own debris. There were indications of an upper wooden story which had perished by fire, and its destruction was perhaps at the close of the first century of our era. Its excavation, which covered twenty-one months, was confided to an expert, and conducted under my own supervision.

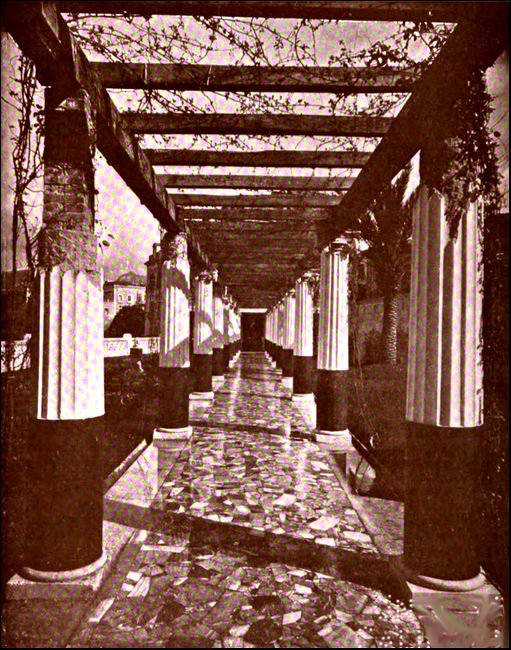

The marble pavement was nearly intact, and the walls were so well preserved in soft earth that in places the original colour and decoration remained. The colonnade was almost complete, only a few pillars having split and disintegrated, and half a dozen capitals fallen. Roofs, rafters and ceilings had totally perished. At the entrance, in black and white mosaic, is the inscription:

HOSPES PULSANTI TIBI

SE MEA JANUA PANDET

"Stranger, if you knock, my door will be opened to you "—a more genial salutation than the well-known Cave Canem of Pompeii. In two places on the walls are graffiti painted on the stucco, perhaps by the owner's hand; one being verses of the Ode addressed by Horace to Dellius, and the other an apparently original composition of poetical character. In the wine cellar is a verse scratched in faulty Latin, the jest of a slave, the sense of which is as follows:

Two white, startled nymphs dashed away to the river.

Mid shouts of a satyr borne o'er the whispering vine.

Down the hillside they fled, leaving their laughter,

Nearer leaped the satyr, cajoling, beseeching, commanding,

A splash—they are gone. Lost in the deeps of the

river.

"A plague on all water fowl!" muttered the satyr.

On the atrium floor lay a statue of the boy Bacchus which had

stood as a fountain at the side of the impluvium, and scattered

about were fragments of bronze tables and chairs. It made one's

heart leap to watch the excavation, to see ancient objects

brought to light, and to be the first to tread again that classic

pavement.

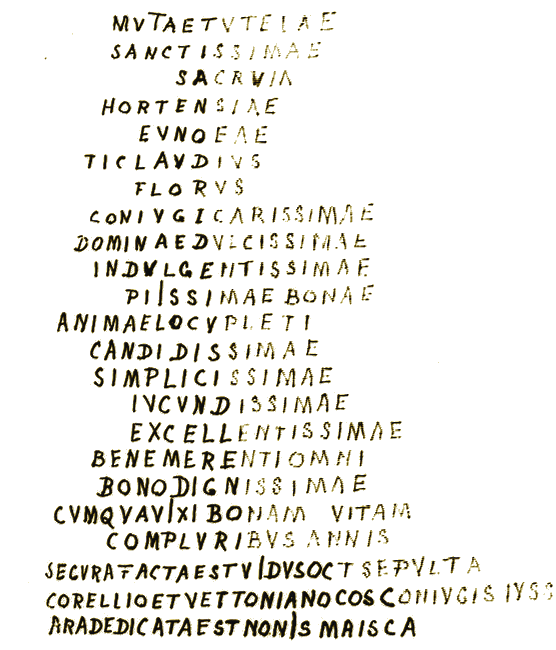

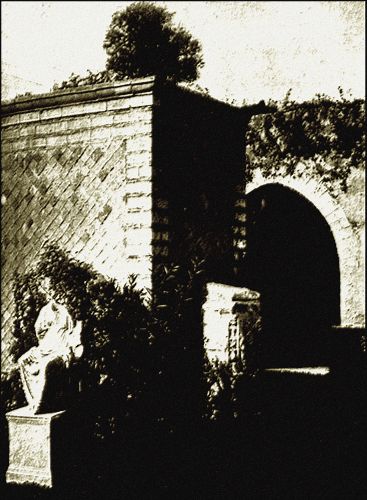

Amid several marble ornaments in the uncovered garden, and close to the monastery wall, was half a memorial stone six feet high. In some bygone age it had been sawn vertically down the middle, the missing half having doubtless served as building material.

Amid several marble ornaments in the uncovered

garden was half a memorial stone six feet high.

When the fragment that remained had been placed upright, half an inscription was deciphered, to which I devoted some studious hours. It became evident that herein lay a clue to the story of the house, and my labour was rewarded as tentatively, phrase by phrase, the inscription was reconstructed in its entirety, the conjectural restoration being shown in lighter letters.

[The inscription was reconstructed in its entirety, the conjectural restoration being shown in lighter letters].

A place consecrated to the sainted Hortensia Eunoea; a dear spouse, charming kind and devout, generously furnished with an excellent mind, courteous, sincere, genial and distinguished, well deserving of every good; a worthy lady with whom I, Titus Claudius Florus, have lived a good life for many years. She was rendered free from care on the 11th of October, and was buried during the Consulate of Corellius Vettonianus. By command of her husband this altar was dedicated on the 7th of May.

In Hortensia's Garden

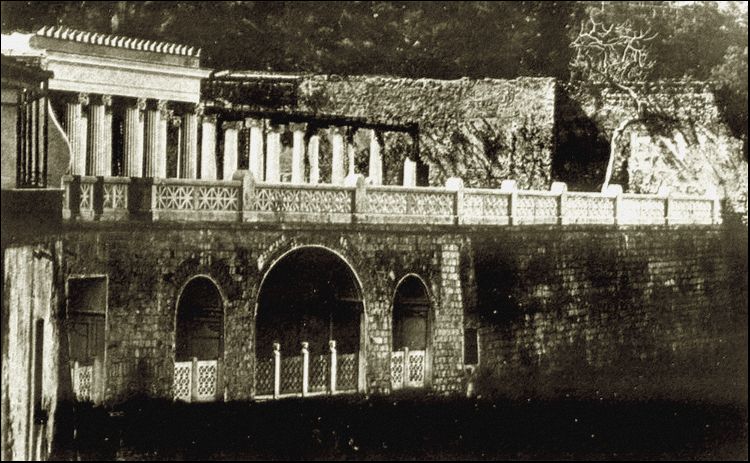

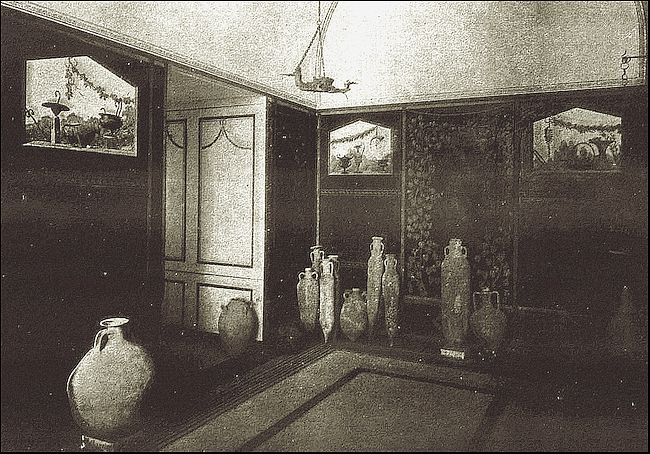

The lower floor of the villa, which had been hewn in rock, and is on one side open to the sea, was easily cleared. When the rubbish which choked its flight of steps had been removed, I entered an ante-chamber and crossed the wine cellar wherein leaned a score of terra cotta wine jars. Beyond was a large dining-room, with arched ceiling and an open balustrade overlooking the Bay of Naples, Beside this triclinium is the kitchen, with ruined stone oven, granite pestle and mortar, and fragments of bronze cooking utensils. I realised that an important discovery had been made, and delighted myself in visiting those silent walls, now reopened to the sky. How wonderful a transition it was to pass at a step from the trim paths of my cloister garden—from the green and silver of its olives, with their calm ascetic shade, and the dismal Christian emblems the monks left there—to a fragment of the golden Surrentum of classic days as fresh in its reappearance as the pressed leaf which after half a century retains something of its pristine brilliance. Even the sunshine seemed to me transfigured to an unusual splendour, remembering how passionately the ancients were heliophile in their love of the sun.

Several times during my researches I heard the voice of a crying child, faint and remote, yet apparently within the excavation. It was a sound of intense anguish, beyond ordinary pain—a wailing of weird significance. I called the nearest workman, and asked who had brought a crying child. After a moment's listening, while the sound died tremulously away, he gave me the conventional reply, chi lo sŕ? The men working above had heard it, and to them it seemed to come from below. There was no child to be found, and the sound ceased for that day. Chancing to meet the porter of the adjoining hotel, I asked if any of the employees had heard this noise, and he seemed amused as he answered with twinkling eyes of Italian humour: "Surely, Signore, in a rabbit warren, tana di conigli, such as Sorrento there are swarms of children, and who gives heed if one should cry!"

In resuming my examination of the triclinium I raised an amphora or wine vessel that had fallen with its nozzle buried in sand. Like the others, it had originally been sealed with wax, the usual method of preserving wine. I was surprised to find slightly protruding from it a yellow-stained papyrus that, owing to the waterproof character of its receptacle, had escaped destruction. I returned to the Villa Sirena, and, having moistened the paper with a wash of vaseline, flattened it on my work-table and found that it comprised three separate scrolls, one within the other, each covered with tolerably legible writing. I washed these scrolls with a camel's hair brush dipped in hypo-sulphuret of ammonia, and dried each quickly with fresh blotting paper. By this process the faded words were rendered decipherable, and my assistant copied out the writing before the brown ink perished from exposure.

Beyond a large triclinium or dining-room with arched ceiling.

On the sacrificial altar is a figure of a youthful Bacchus.

It was the work of weeks to make a free translation of the first-century Latin into English. The outer scroll was the writing of Dexter Quintilian, an aedile (magistrate) residing at Vicus, the neighbouring modern Vico Equense; the next was the work of Hortensia Eunoea, owner of the villa; the last having been written by Titus Claudius Florus, her widower. They differ in size, quality of paper, handwriting and colour of ink, and form the points of view of three persons as to a homicide of which Florus was suspected. They might be likened to a modern solicitor's packet of documents. Their united version is a plea of "not proven." Their narratives are more a review of the events of several years than a defence against the charge of assassination. Half a dozen years had elapsed when Florus wrote, and if guilty he must have felt the security that lapse of time brings. Dexter Quintilian arrays the facts and evolves from them his friend's justification. The crime is mentioned as having been committed the year after the destruction of Pompeii, which happened A.D. 79, but it is not until two years later that the suspicion against Florus becomes so acute as to place him in danger of a prosecution, from which he was saved by the favourable report of his friend the aedile who had been sent to investigate. The three letters collectively present a dramatic picture, and the recitals are illumined by curious allusions. Hortensia's description of her infant's death has the sinister accent of biblical tragedy. The killing of her first husband having occurred a.d. 80, her marriage to Florus took place in 81, and if the consulate of Corellius Vettonianus was in 87 (reign of Domitian) Hortensia was aged about forty-five at the time of her death.

In the intensity of their narrative we meet these people living and not dead, and know them intimately for an hour. Their manuscripts may have been secreted in an empty wine jar in the haste of some sudden alarm. It does not appear how the roll came to be in the possession of Florus at his wife's villa, where we find him residing after her death, but if he were still apprehensive, he would naturally preserve at hand this testimony to his innocence. The picture flashed from these scrolls presents the murdered husband Eutychianus, a Greek, surnamed Comazon; Florus, who writes with something like poetic fervour; Hortensia standing wistfully still amid ill-fated days; and their friend, Dexter Quintilian, beneath whose phrase one cannot but perceive that he, too, loved Hortensia.

Quintilian and Florus were tribunes in Judaea, probably serving with the XII. Legion about A.D. 68-69. The years of siege and sack and slaughter that preceded the taking of Jerusalem they must have witnessed fearful atrocities. In half a dozen years over one million Hebrews perished, many of them prisoners sacrificed to Jupiter and Mars according to custom before the Roman eagles. What wonder if through the centuries those emblems came to be known to the conquered of all nations by some such name of horror as the Master used when speaking of them to his disciples: "The abomination of desolation standing where it ought not."

After reading Hortensia's story I understood the mystery of the child-voice lamentation. It is occasionally heard, always within the ruined walls, yet infinitely remote, always perfectly human albeit thrilling with preternatural distress. But now, since it appears that the wailing of the boy Laetus is as much a part of my excavation as the ocean murmur is inherent to the dead sea-shell, I no longer heed this voice from the silent river.

Looking from the Cloister Garden into the Villa Florus.

The portraits on the sarcophagus are supposed to be those

of Florus and Hortensia.

Dexter Quintilian to Hortensia.

Hortensia,—I dip my reed in the brown since you so bid me, knowing it is right you should possess my judgment as magistrate, as well as friend, upon the accusation brought against your husband in this jarring scheme we call life.

The facts present a grave contradiction demanding of a judge that refined intellectual perspective he must borrow for the occasion of the nearest philosopher. There is a probability that at the moment of the crime Florus was miles away; but against it stands his curious aberration which almost assumes the character of self-accusation. No one saw the assassin, and the only motive for the crime that has ever been suggested is offered by the accused's marriage to you less than eight months after your first husband was slain. That a man of Florus' public standing should have placed himself in the power of men hired to commit a crime is unlikely.

In the study of homicide, we begin by reconstructing the tragedy with its dramatis personae applying our gaze where there is nothing now, only the conjectural something that was. This is the first step toward approaching the heart of the motive that swayed the criminal. We place in symmetrical line the circumstances so far as established, and this we call evidence. Only, as all the world knows, evidence sometimes plays the game with loaded dice.

It was in Judaea, campaigning against the Hebrews, that I first met Florus, both of us being tribunes in the same Legion. Two years were spent marching, killing, besieging, and burning. One day at the storming of a gate at Zebulon, as we stood looking on together, we saw a band of Hebrew girls, armed and habited like archers, appear above the rampart. They bent their bows with great harp strings, and one flung a hammer which struck me in the face, leaving its indelible print on my lip. "I have spoiled thy mouth for kissing!" she screamed, lifting her arms with a shrill laugh of triumph. Quick as thought Florus raised the Parthian bow he held and sent an iron bolt deep into her body. When I heard the charge that was brought against Florus and the manner of Comazon's death, I wondered if the assassin, whosoever he might be, had also a Parthian bow.

I wonder if you remember my wife Pantheia? In moments of anger she was wont to look at the scar and whisper with her slow diabolical smile, "the Hebrew girl said right—spoiled for kissing!" We were living in Pompeii two years before it perished, and she made of my house a resort of those who at night practise rites of Isis, bringing there the priests of the moon goddess to sacrifice with mischievous dances and the flutes that breathe such deadly poison. Wherefore coming one evening into their midst, I chased the Egyptians back to their temple, and taking from Pantheia the house keys, turned her out of my door.

I often meditate upon those earlier days, when Florus and I were together, and he may sometimes have talked to you of our adventures in the midst of the hate of that Hebrew people, which despite their ruin is not yet subjugated. It was a joy to be a soldier, for the Legion was supreme. It was the school that formed men who brought to the task of conquest a capacity that touched them with the ideals of those who led. Hard and scarred, a Legion was no bad type of concentrated force. What wonder if the sight of its spears lifted the mind—if the blare of its bugles thrilled the heart!

Now we have fallen upon evil times, and musing upon the havoc of Pompeii, I ask myself if that awful scene foreshadowed a wider devastation. Ruined and dead. Can that become the fate of Rome? Yet ever, listening to the music of a marching column, filling the sky with its challenge, I believe that ages hence, when Rome has ceased to be, that sound shall still ring down the centuries, while a remembering world may whisper—so sang the unconquered!

You ask me to review the facts upon which my report to the Governor rested. Florus declares that on the afternoon of the crime he was at Vicus, which a runner might reach in an hour from Surrentum. After the lapse of a year, time of day cannot be determined. Often the best memories are not sure of a day, nor whether it was the Nones or the Ides when something happened. Domitia Lepida is able to declare that Florus was speaking with her at the door of her shop when the earliest word of the crime reached Vicus. Some hours sooner, your first husband Eutychianus, better known by the nickname of Comazon, embarked at Vicus with the boatman Sisibius, son of Gela, the blind one. He wished to sail to Surrentum, and so ordered his departure as to arrive there before sunset. He is not known to have had an enemy, nor to have been recently involved in a quarrel. Men remember little of him beyond his old-fashioned Arcadian frugality, and that when he pleased he could give his words a whiplash sting. Surrentum laughed at his priding himself on being descended from that primitive Greek race whose women, when every male had been slain by the invader, stabbed their conquerors in their sleep, dishonour being thus changed to glory.

When within half a mile of the landing beach Comazon asked to be put ashore at the point of rocks where a footpath ascends, and the statement of Sisibius is our guide as to what followed. Immediately upon stepping ashore, and while preparing to climb to his villa, Comazon was struck in the middle ribs by an iron shaft fixed in a hard band of cloth which caused almost instant death. Whoever discharged that bolt held a weapon of extraordinary power in whose use he was an adept. Sisibius, greatly terrified, leaped back into his boat and made for the landing-place, where he told what had happened. The town watch, followed by some idlers, hastened to where Comazon lay dead. Bending over the body leaned Passienus the dancer and Beryllus the barber. They declared that descending the cliff to bathe they heard Comazon's death-cry. They averred that the shaft could only have been discharged by one hidden in the bunch of trees near by called rustling pines. Comazon spoke but once, with ferocity. "The boatman led me into his trap." The hiding-place was searched, but the assassin would have had more than time to escape. As to his ejaculation, did Comazon see and recognise the assailant? Into whose trap had Sisibius led him? The barber told me a straightforward story. Beryllus is a tipsy clown, but no suspicion attaches either to him or his companion.

What weapon was used to send that heavy missile flying? May it have been one of those hand catapults with whose mechanism Archimedes beguiled his leisure three centuries ago? It is an odd coincidence that the boatman went raving mad before the month ended.

I examined the fatal bolt and visited the scene of Comazon's death, the grove of rustling pines. It is forty paces from the landing beach. On the day I was there some fishermen were gathered about a kettle singing a familiar chant which Beryllus, who had come with me, said was being sung out on the bay by these same men at the moment of Comazon's death. By Mercury, the vigilant, how-many were looking on, yet saw nothing! Their silly song caught my ear, though it was but the refrain of "Sea-sand turned to gold."

From the silent dark of his grove,

From the sunset heart of the day,

The sun-god beckons smiling.

His lips are forever tuned with song,

"Oh give to me," he cries, "this hour,

Are we not sprung from an equal dust divine!"

I smiled at the thought of what our grandsires—most of

whom still clung to the Immortals—would have done to a

parcel of fishermen whose audacity imagined them "sprung from

dust divine." I sent Beryllus to bid them come, which they did

abjectly enough, and spoke up forthwith when I told them my

business. They contradicted the testimony of Sisibius in a

notable particular, saying that passing quite close they

overheard Sisibius beg Comazon to land at the point, as he dared

not venture to the beach, being under sentence of a whipping if

found at Surrentum. Admitting this to be true, then so far from

Comazon asking to land, it looks as if the boatman had knowingly

put him ashore to meet his danger. The fishermen added that they

gave small heed to what was said and had passed on out of

view.

Now comes the suspicion that first attached to Florus, when after only eight months you married him suddenly in the presence of a few intimates—you, the rich and childless widow of a man you had both detested. That you had been the love of his youth was no secret. Is it strange that people asked if his hand had bent the fatal bow? When questioned in my presence—a painful ordeal for us both—it is not unnatural that after the lapse of so long an interval he could give no account of his whereabouts other than that on hearing of the homicide he had hastened to you.

My judicial inquiry was made two months after your wedding day—that day of inauspicious incidents when it seemed some malevolent spirit cast ill omens in our teeth, from the illness of the priest to the theft of the wedding cake and the breaking of the chalice that fell. And yet I remember that day as one remembers the sunshine of some childhood we have lost. It brought back the promise of my own marriage, and I delighted in the joy of my friend. Your garden spoke with the liquid voice of a nymph. From its walls fell rose garlands in cascades, and your Babylonian hangings seemed like summer's tapestry. I felt that for once it had been given me to behold the rapture a day may bear in its heart.

And you, I shall never forget. To this day I think of you with hushed pleasure, as we think of last May's roses. You stood welcoming your guests, charming, delicate, and rhythmical, unperturbed even when your freedman Gehasi handed you dried, dead fruits, and silence followed. I divined that you are a poetess in your dainty, fugitive way, and the sight of you brought a sense of fine reeds bending by the river, of something brilliantly touched with romance, of the verse of a carefree song. Over a long tunic of linen your mantle was thrown back from the statuesque contours. And when taking your hand I murmured my salutation, your face flushed like the pink of dawn, wherefore remembering likewise the sinister omens of that hour, I urge you, if only for the sake of your newborn baby boy, to pour abundant libations to Hermes the interceder and to sacrifice to all the....

(Last lines discoloured and illegible.)

The colonnade leading to the house of Florus.

THUS far had I deciphered, doing my work in the sunshine of Hortensia's garden, aiming to seize the spirit of each writer's words and often reproducing them in modern form, when on reaching the end of Ouintilian's writing its reference to Hortensia's "new-born baby boy" impressed itself upon me, and I wondered if behind it lay that voice of a crying child.

Each morning my work-table—covered with writing paper, the manuscripts, a Latin dictionary and grammar and some books of classical reference—was brought from its shelter in the atrium to a shaded angle in the peristyle, whence I looked across the Bay of Naples to Vesuvius and Parthenope. About me grew a profusion of hyacinths, and some golden-dusted mullein stalks were climbing the broken wall. The ruins of Hortensia's habitation, with their warm whiteness, seemed a daintily-carved ivory toy placed on a table of grass-green jade. It was in April, when the Italian springtime draws near on tiptoe. Beyond the cloister wall a couple of olive trees the friars had planted rose gnarled and grey, their silver branches flickering. I watched the sunshine piercing the leaves, and listened to the undersong of the sea. Beyond Misenum the saffron distance was tremulous with light of pearls. In those perfumed hours that garden's subtle dark spoke with an accent of intense significance. My thoughts were with those bygone days that must have been as beautiful as these. On the air was a murmur of things lovely and unknown, like the magic of unfolding colour, and the living glory of the air made me quick to understand that my task held a mystical revelation where immortal chariot wheels had left their trace.

HOW shall I thank you, wise and gentle friend, for the good letter I have carefully preserved, yet left unanswered all these months?

I must begin by telling you the saddest word I have ever written, and writing I wonder if indeed the secret of life's futility lurks on the cynical lips of the gods. Laetus, my baby boy and the child of Florus, is dead, and every day now I hear death walking in the garden. It was two months ago, in the dawn of a winter's morning, and you who know the operation of extraordinary forces, shall tell me if from beyond our earthly ken a hand was outstretched.

When Comazon married me and took the roses out of my youth I resolved to retain the mastery over myself and lead my own life. He was old, a pale, white rustic of a man, full of Greek cunning. My guardian, who made the marriage, called him "Rabbit-ears," since in excitement those appendages of his quivered and shifted. He had a clown's fury behind a cringing smile. His appearance reminded me of an amphora that is brought crusted and stained from the cellar. What he called love was a cupid painted on the wall. Now that his spirit has passed, I entreat you to tell me if it can have power to return from the Stygian pines?

The entrance connecting Villa Florus with the Cloister

Garden. Ante-Room, Wine Cellar. Triclinium. Kitchen.

His death came in the midst of my soul's starvation—and after came Florus. When we were young—lad and girl together—we used to look in one another's eyes. I think of myself with infinite compassion in those girlish days. Once he kissed me, and that kiss burned into my life and made it his. Now, after five years' misery, he found me in the enchantment of my garden. Having never lost the sensitive instinct of youth, I have preserved a full-blooded love of wild things, and am never so deeply thrilled as when the voice of the forest speaks its everlasting truths. I was living alone in this home—which you once called a cup of opalescent crystal—alone, with Florus to come and see me every day. Can one handle fire thus, hour by hour, with never a scorch? Yet how could I resist the alluring love of my life!

Yes, Florus came, light of foot and masterful, with persuasive lips and the grace of sweet thoughts. One blue summer's evening he repeated to me the mosaic of Calvia's song, how the sun-god and Ariadne kissed, "only to kiss the air," repeated the refrain, "the air that kissed her." And my laughter ended in a sob. I was so happy that the tears rose to my eyes—I who have often said we women get from our men something of that flinty fibre which is the heart of Rome. All through those days, in the delight of the eager sunshine he had brought, the twilight of empty brooding ended. Each morning took on its own poetic lustre, and I lived anew in the traditions of these shores and headlands. I laughed to remember that satyrs with passionate eyes were said to lurk in the Pompeian byways. Often we sat together among the trees that go down-crowding to the water's edge. The jewelled bands of light and colour that came and went against Vesuvius seemed a type of antique splendour as though a transfigured vision of Troy and Carthage flitted by.

It appears that you, too, Dexter Quintilian, remember the wedding day—the milky lace of breaking waves, the scent of sacrificial fire, the thousand tiny things in Nature that fain would lift their little voice. I remember how with a snatch of song was loosed for you the sixteen-year-old wax of my choicest amphora. And drinking that purple Setian you arose and, as the Athenian flute players rippled to silence, you declared amid the clapping of hands that ages hence strange races coming after us shall taste the splendour of our Roman life as it were old wine!

We had not long been married when a murmur of public suspicion reached Florus, and over his face came a subdued look as across the sea steals the gathering dusk. I listened awestruck when he told me that returning in the brooding twilight the spirit of Comazon stood at the door and waved him back. That this had been several times repeated, that he had rushed upon the phantom, which vanished at his touch. That the spectre called him by name, its voice being elusive and mocking as a woodpecker's far-away tap. All the evening we sat silent together watching the star-clusters shaping fantastic hieroglyphs for men to read. Beside my garden's fragrant breast I listened to the sea whispering its foreboding of the ruthless to-morrow.

Next morning came to us Gehasi, the Hebrew, become a Christian, whom Florus brought from Zebulon and hath freed. The same, for all his broad black brows, is grown soft with butler's service, and offered to accuse himself of the murder of Comazon, and confess to it if by so doing he could save his master. He spoke as hushed as a breath of air. By Hercules, the traveller, he Cometh from a strange land, and bringeth far-fetched imaginings—one whereof he hath scratched on the plaster wall of his lodge:

THY SINS, WHICH WERE MANY, ARE FORGIVEN.

When I questioned him about that graffito, he said that fifty years ago they had been spoken to his mother, whom he remembered as a pale, grey-haired woman. She had once been beautiful, and in its red splendour the long hair had been her wicked pride. Till, having become bitten by the acids of wayward lovings, she had anointed with passionate tears the feet of one that was crucified, and wiped them with the gold of her head.

Before the day was spent that terrible suspicion was in every mind. It was in the eyes of Demetrius, the eunuch, tidying my toilet table; it was in the atrium's pensive splash of falling water; I heard it in the crooning of the slave girls over their kitchen kettles, I felt it was written upon Nature's outdoor scroll, I caught it in the repetition of a knife-grinder's sing-song; and Florus, listening, glanced furtively over his shoulder.... Yet behind the anguish of that look I perceived that he saw nothing, that his mind was far away.

Soon after, you came—our mists vanished, and I listened in silent joy. Your words that showed my Florus guiltless were sweet as the tuning of lutes. In an hour the discords of life fell away. It was as though you had restored the key of some remembered garden. The smiling side of life rekindled as it does in the hearts of mariners sailing by night over unknown seas when a breath of scented grasses whispers the land is near.

I have told you that two months ago our child, Laetus, died That day my youth passed from me. A foreboding had crossed my sleep as though shapes made and unmade themselves. You will say they were but waves of the night, or the wind singing of the sea. I awoke, and, looking forth, beheld the pink of early dawn, and heard the patter of phantom feet. In the next room, the door between being open, lay Helvia asleep, and beside her the boy. Near the pillow-was the child's nursing bottle, and all this I saw by the spark of a dying night-wick.

All was still, yet from the heart of that silence rose a strange vibration. That dying spark was the red omen of an advancing shape which was Comazon. It noticed me not, but taking the child's bottle poured therein something that went gurgling down upon the milk. At the instant the child stirred, and Helvia sat up and gave Laetus his bottle. Then, as the spectre vanished, the child drank, whilst I stood riveted. A cry rent the night—as keen as the child-like scream of a wounded hare. At which the blood rushed to my heart, and I lighted a taper and summoned Florus and aroused the slaves. Three hours after that tiny soul had sped to the solution of its own mystery. Now with that outcry still ringing in my ears, I ask myself how the stars can shine so brightly upon an anguished world.

More than this, I know that I, too, bear upon me the marble signature of death. It was Comazon that killed my child—that will kill me, for out of the half-light his hand beckons, and his lips move in a summons only I can hear.

Farewell. The circle of my life is rounded, and that grey presence bids me go. Presently over these walls the unremembering years shall close, though it seems to me that beneath their ripple must ever linger a stain of these things. — Hortensia.

I BEGAN deciphering the manuscript written by Florus with an interest greatly heightened by my study of the foregoing narratives. It will be observed that he makes no circumlocution, but utters forthwith the emphatic denial of one who considers himself manifestly innocent. In important particulars his statement varies from the facts accepted by Dexter and Hortensia. He has his own theory as to the part taken in the crime by the fishermen, and his wife's terrors, which weigh against him, are dismissed as hallucinations. In his opinion the shock resulting to her from a public suspicion produced mental aberrations, which became so intense as to create an illusion regarding Laetus, and ultimately to become the cause of her own death.

The wine cellar wherein leaned a score of terracotta wine jars.

The character of Florus, scantily revealed, receives a curious sidelight from the subtleties of his self-justification. Was he misjudged by that blundering sot, vox populi? He tasted bitter hours, and presents that spectacle the ancients loved, a strong man battling against great forces. I cannot doubt that the graffito on the atrium wall was traced by his hand—that in dwelling upon his favourite lines to Dellius, the sense of which I have rendered very freely, he was thinking less of the beauties of Horace than of his own sad heart:

Cherish, O Dellius, a tranquil mind,

Whether amid the good or evil things of life

Not uplifted by the pride of thy success,

Remembering that thou too must die.

Let thy joy be in Nature's sweet repose,

Amid the shade of interlacing boughs,

In some fine seclusion where the streamlet

Goes musically rippling far and far away.

Quintilian,—I have lived my life, and am ready to meet that decisive experience that awaits us all—whether beyond that dim portal our eyes shall be opened, or are to remain forever closed. But first to you, my life-long friend, I have somewhat to say, knowing that the truth will not tear in your hands.

I have never wearied myself with vain and fugitive trifles. My passion has been the study by analysis and comparison of such grains of absolute truth as Plato and Socrates gleaned. Have we advanced a hand's-breadth, think you, since their day? From that study alone may we derive those elements of intellectual force which sustains us in this flame-lit world. So now speaking with Hortensia's name upon my lips, and in tranquil anticipation of the supreme shadow, I doubt not you will believe my words.

Two months ago I sent you my despairing announcement of Hortensia's death. She had so tortured herself between apprehension of what might befall, and distress at what had happened, that her mind became a web of fevered anxiety from the midst whereof she murmured me again and again—I pray that I may die... that I may die.

As to her fears, how often had I put for her the facts in measured line. You and I know that Comazon was murdered by the fishermen. As to me, Gehasi will tell you I divided that afternoon between eating a roasted kid, and playing by myself a racing game with the two little ivory chariots I bought in Rome. Now on the day preceding, it was told the fishermen that the money-lender had been repaid two small loans and a morsel of back rent upon his Panormos estate. Gehasi is ready to swear that the day before his death it was town talk at Vicus that Comazon received fifty pieces of gold. But death wipes a clean slate, and his money gettings vanished, as the four fishermen know. When Sisibius landed him at the point, he deliberately sent him to his death, and with the commission of the crime Comazon's purse of gold disappeared. The fishermen's hymn to Apollo was a blasphemous jest—they meant that from such golden dust as those shining pieces were the Immortals made and nourished. Beneath such songs is often an equivocal undertone, as it were to the physical ear a subdued sound of the distant clashing of shields. It was some such undertone—some demoniac song within the song—that Sisibius heard day and night in frantic repetition, till he went gibbering mad and died.

Now, as to the mystery of Hortensia's ending, with whom was she in spiritual converse throughout those visions that plagued her last years, till, from one hallucination to another, the ghastly phantoms she created rose and smote her, as Gehasi saith, to the heart?

It is he who of these things tells me somewhat beyond my own knowledge. Several mornings she paused to talk with him in the garden, questioning upon his boyhood, in that distant Hebrew land of fire, upon his fighting days when I dragged him from a burning house at Zebulon, mistaking him for my Roman servant who lay dead in its ruins, asking of his mother, the woman with long white hair, and ever returning to the meaning and power and association of the words he had graven above his pallet bed:

THY SINS, WHICH WERE MANY, ARE FORGIVEN.

Can I doubt that something secret, of vast and profound import, had revealed itself to her? Looking into the grey eyes I loved, I beheld in those days that they were dim—as though they had seen their dearest illusion fade and some terrible reality awake. Walking with me one day, tremulously smiling, yet with an air withdrawn as one who meditates upon predestined things, she said: "When springtime comes I shall be strong and glad," but before spring drew near came that death for which she prayed. Gazing in her delirium across the soft density of distance into some rare and odorous space whereof she murmured, she beheld Laetus, and imagined she was being allured by the enticement of our child. From before her faded away all earthly things, and in their place opened a transfigured enchantment with the darling face in the midst. My heart stands still when I think upon that miracle of love. What wonder if before that presence she whispered me over and over—I pray that I may die!

It was Gehasi that, with white quivering face askew, called me from my sleep. "Come quickly, master," he cried, "if, talitha cumi!, it still be time. For an hour hath she sat in the garden, as it were her own statue watching the dawn-lit sky, till of a sudden I perceived that her face drooped, and that she moved no more."

I came at a stride, and found her sitting, as Gehasi said, amid the laurel and acanthus, as it were her own statue, listening to a dear voice that calls—a voice inaudible to others. What was it she beheld or heard in that last hour of earth on the skyline beyond the makers of rainbow and mist? Behind the ripple of the waves was a faint vibrating sound like the throb that lingers when a harp-string breaks. "Can you doubt, dear master," exclaimed Gehasi, seizing my hand, "that she beheld again her dead child, and that her heart, like the bush before the prophet, leaped into flame?" He was right. She had listened to the summons of that irresistible persuasion, which those familiar with curious arts tell us links the living with the dead. If this were suicide, and if suicide be sin, may we not believe that the gods, who have themselves known and weighed human attachments, will judge very mercifully a mother who thus loosens her hold upon earthly things? Hath she gone to a sleep from which no cock crow-awakens, or hereafter shall I find her again?

Then the women came, and amid many voices a coverlet was brought, and upon it I laid her. And it was the sunrise of a beautiful day, and I knew that she had passed into the light.

Wherefore now, although she rests far from here in the shade, it gladdens me that the light which was in her beautiful eyes is still for me the light of radiant mornings in her garden. Haveto.

INANIMATE objects acquire interest according as they are associated with human emotion. Some memory of heroism or love, the idyllic presence of a passionate romance, the wraith of infinite unhappiness—these lend to the things of earth a divine significance. What were the mound of Troy without its Iliad, or Olympus bereft of the footprints of the Immortals? And whoever visits that renowned Temple of Isis at Pompeii, of whose rites Dexter Quintilian disapproved, will wonder what may have been those mysteries which have made it famous?

Upon the painted walls that knew Florus and Hortensia still float Poseidon and Lyra and Antiope. The very stones seem imprint with the tragical intensity of the story they have told. Their writing has veiled them in the imperishable bloom of that Roman day. From the Silent River they speak to us of the things which were their life. Almost we feel again those vanished emotions, and where they walked remains the footprint of a brooding presence.

In Hortensia's garden linger many day-dreams of that forceful age. Its tiny span thrills with imperishable memories. To its peristyle has been restored the glory of those cascades of roses whereof Dexter Quintilian speaks. Its parterre is bright with the heliotrope and iris and anemone the ancients knew. Violets and verbena and honeysuckle and sunflowers are in profusion, so that the air is fragrant with the odours of that century. Sometimes sitting in the atrium, turning, in the purple-dusted twilight, some classic page, I remember Quintilian's boast that while the world lasts the voice of Rome shall still ring down the generations... and how dull must be the ear that never listens to its call!

Sometimes sitting in the atrium, turning, in the purple-dusted

twilight, some classic page, I remember Quintilian's boast that while

the world lasts the voice of Rome shall still ring down the generations.

Beneath some fallen débris lay a headless and handless female statue. Despite all mutilation, it preserves the shapely symmetry of its pagan day. It is a seated figure, wrought in fine marble, and has the appearance of first century work. The injuries were probably inflicted by early Christians, who in their iconoclastic zeal broke everything suspected of resembling gods and goddesses, and who, perhaps, set fire to the villa. Shattered though it be, the fragment possesses an exquisite repose, and the same serene beauty that delights us in the seated figure of Agrippina.

Despite all mutilation, the headless and handless

statue preserves the shapely symmetry of its pagan day.

The thought suggests itself that Florus, spending here the final span of life, may have had this sculptured portrait of Hortensia placed in her garden in that attitude he describes, when against "the dawn-lit sky" she looked her last on earth.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.