RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

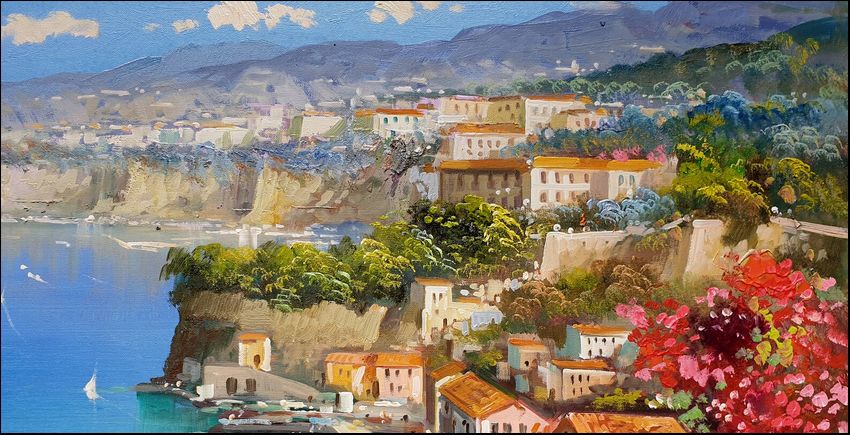

IT was to his Villa Sirena, at Sorrento, amid its interbraiding shine and dark, that Vaini summoned me, in May 1895, for a psychical experiment as to which he wrote, "The door of classic life will be wide open before us." I had spent a few weeks in Naples aiding him in unrolling a dozen Herculanean manuscripts, and was thus within easy reach. Our correspondence during the preceding twelve months had enabled me to follow those tendencies which continually drew him to realms of speculative thought. I knew with what delight he mused upon the imagery of bygone times, and perceived that within his mind had kindled an ambition to discover the mystical links and mainsprings between modern and ancient days. During the earlier years he had caught some of the finer phantasies and made them real, and he was now ardent to stand within some reanimated precinct of the antique world. He seemed drawn to what proved the most living of all our experiments by a force akin to the magnetic attraction of great gems: and now, in tracing this summary of an afternoon spent beyond that "wide-open door," I realise afresh that there are experiences which give meaning to all the rest of life, and in reviewing this fugitive recital I note with satisfaction that it bears the impress of Truth,—that everlasting hall-mark which is not to be effaced.

I found the Professor in his orange-grove pruning and watering his favourite trees. His brown eyes were soft with dreaming, and, as though putting the last accent to some train of far-borne meditation, he greeted me with the words, "The result rests on the knees of the gods." I took in the familiar scene at a glance—the Villa overhanging the sapphire sea, the Monastery green-curtained amid its myrtles, Vesuvius ten miles distant across the sparkling brilliance of the Bay of Naples. About us spread a delightful privacy of shade that lured the fancy, and over all rested that peace of Nature which is as divine as the wise silence of Olympus. I delighted in its over-wood of orange boughs, its undergrowth of jasmine and oleander, and beneath these a fine texture of mosses and wild strawberry leaves and violets. Chiefly my gaze rested upon a tall lady lilac bush, a luminous pink shrub, whereon the Italian sunshine streamed its witchery of opalescent hues. I doubt not the juices of that tree are the love-blood whereof poets write. In the warm stillness its branches bent in the light breeze and thrilled the air with meaning. I thought it splendid as a beautiful woman, and was absorbed in the jewelled spray of fancies it suggested when Vaini cut short my reverie.

"Here," said he, laying his hand upon my shoulder, and pointing to the lustrous foliage, "here is the place of my soul."

Our vegetarian luncheon finished, he explained the fine-spun theory round which his studies hovered. In removing a foundation wall of Roman origin, his workmen had brought to light a thin section of crimson onyx, richly veined, which he had recognised to be a Golden Mist Stone. On each side was drawn an ellipse, about which were grouped signs of the Zodiac and points that evidently marked the position of astronomical bodies.

The Golden Mist-Stone.

"Dear Master," I interrupted, after a summary inspection of this object, "what is a Golden Mist Stone?"

"I am vexed," he answered, with pained surprise, "to hear you ask elementary questions, after all the years I have led you through hidden ways towards the unfamiliar side of things. We have to do with the electric force of that Golden Mist commonly called the Nebular hypothesis, and this stone is a tangible expression of that crown of roseate light we see forming and fading. Upon it has been traced a planetary conjunction which is its key through ages back and centuries to come. For several months I have been absorbed in the astounding properties of this fragment. I will not pause to explain their application at this moment, since their trial must be made to-morrow. My colleague in Berlin fixes the original date as A.D. 294, which was in the reign of Diocletian. This identical conjunction is present now for the first time since August 1793, and will not occur again for a hundred and twenty-eight years. I have made the necessary preparation, and after its black crystal bath the stone is to be held in the light to-morrow precisely at noon."

"I divine your thought," I observed: "that herein exists some soul-wrought chain between ourselves and remote periods."

"You have read rightly," answered Vaini, with a kindling glance. "In this petrifaction I detect truths startling in their novelty and power, yet definite and certain as that beneath the chill of frozen winter hide the promise and buds of spring. I have often shown you that intellectual landmarks are sometimes most useful when they point to disillusions: now, at last, in the evening of my days, it is mine to fix the theory of mystical perspective."

"You really believe that under these conditions it will be possible to behold..."

"Nay, I have already beheld that which made me catch my breath. The bones of the old world sometimes lie very near the surface. It was three days ago, a trifle too soon astronomically, and I had not properly charged the black crystal bath. Nevertheless I touched the fringe of that we are in search of. To my joy, the outline of this villa faded, and in its place appeared a semblance of some wholly different building. I even saw a falcon-faced fellow, who gazed at me with affright."

"Was he a Roman?" I interrupted.

"Here is a trace of him," the Maestro answered. "A dust portrait, fixed upon the Mist Stone itself by the method you and I have practised together."

Taking the onyx from my tutor's hand, I peered intently into its depth, till a figure emerged from a blurred background. It was an undersized, swarthy old man, habited in short-sleeved tunic, standing with a hand upon either hip and laughing noiselessly to himself. I could see his aged and minutely wrinkled face and the yellow gleam in his hard black eyes. At a glance I knew that rock-hewn facial type to lie Roman. His left shoulder was slightly depressed, as though by a lifelong burden. Suddenly he discovered me, and in terror his jaws began working silently with feverish haste. I remember thinking that he had thus become a doleful caricature of all humanity's sorrow. Then, swiftly and unaccountably as the image had come, it vanished.

"Place yourself twenty years back," Vaini exclaimed, with the masterful emphasis I knew so well, "in any dramatic scene whereof you retain a clear impression. Close your eyes and picture intently what happened: the semblance of that day will still be vivid—you will behold its imagery and incidents, and the people who came and went will appear as real as you and I are now. So will it be if this talisman disclose its secret. I will not waste time reminding you of the reality of the unseen, for it is as evident as is the evanescence of all reality. It is beyond me to anticipate the precise forces which may rest within this fragment, but we are likely to find them as living as the volition which turns a climbing vine aside from the smooth wall to the nails whereon it fastens its tendrils. We should behold the panorama it bears and listen to words spoken centuries ago. We may learn how it was first charged with supernatural force, for its use is as ancient as the magic ivories."

My acquaintance with Vaini, whom I remember, now that he is no more, as the most fascinating and baffling of men, had familiarised me with that tonic of emotion, which he justly declared to be an incomparable stimulant. His projects were never wanting in proportion and continuity. One of his most admirable demonstrations had been made that winter, wherein, roving at random through the animal world, he established by inference from actual experiment that animals astray upon their humble path of life consult instinctively with one another and receive a friend's advice. In the essay to which he had summoned me, he probably felt too sure of himself to doubt his pupil. But it was in the full consciousness of my own imperfect capacity to supplement his pursuit of intellectual wild flowers that I answered, "Professor, will you tell me exactly my share in this adventure?"

Vaini's manner always took on a heightened charm in presence of danger. An artist at close quarters with a technical and critical problem is intensely human. His voice now sank to that confidential whisper Italians cherish, as he glanced about to assure himself no eavesdroppers lurked. "Carissimo," he answered, "you will keep your hand not on the pulse but on the heart. We may find ourselves confronted by a peril so extraordinary that it will be unique in the history of mankind. We are about to tread the dust of Roman days. What shall we find there, if not men and women as living as ourselves? Who can say that to them it may not be we that shall seem visionary—that to us they may not prove a fateful reality!"

"How," I asked, "when we have entered upon that bygone age, are we to return to the Nineteenth Century?"

"If dipped in fresh water," replied Vaini, "the negative effect of the stone should come into being. The world of Diocletian will fade, and we shall again be standing in this garden. But, mark you, there is a dreadful possibility."

"Which is," I murmured as my companion paused, watching me intently, "that the Mist Stone may be taken from us."

"Precisely. If the worst happens, and we are imperilled, we must instantly join hands, and I will cast the talisman into the nearest water."

ON the following day the clock marked twelve as, after a

morning spent in preparation, we began our experiment. For the

first time in my lifelong acquaintance with Vaini he betrayed

great nervous excitement, and the hand that held the uplifted

onyx trembled in the sunlight. Before us the Bay of Naples seemed

a pavement of lazuli flecked with whitecaps and seamed with

glistening aquamarine. I gazed an instant upon that

shadow-haunted floor, whereon the sunshine and the breeze traced

a silhouette that looked like Love's bent bow. I beheld the foam

of waves breaking into lace along the shore. Beneath us, where

the sapphire paled to emerald, an Italian felucca lay anchored.

Suddenly I observed that its half-furled sails were changing to

garnet red, and at the same instant I felt a phosphorescent glow

rising about me, and perceived a smell like burning sandalwood.

The faintness of an overpowering emotion obscured my senses, and

I heard no more the whisper of the sea. Before me appeared a

Pompeian portico, pearl-white and crimson like a seashell's

lining. Vaini's orange grove melted into tamarind and oleander.

Amid the trees stood two marble statues, slightly tinted—

Aphrodite, singer of songs, and Pallas the torch-hearer. It was

no more the half-light of illusion.... Vaini and I had crossed

the impalpable dividing line, and moved backward seventeen

centuries.

I was looking at a vixen chained to a column, with a litter of cubs running loose about her, all of them making efforts to reach a scarlet-headed, green-backed woodpecker that hung in a cage, when my attention was diverted to the little old man whose dust portrait my tutor had taken. He wore the same short tunic, about his neck was a metal collar, and I noticed that his right ear had been bitten away. He did not at first perceive us, and fancying himself alone with a great hound that stood gazing good-naturedly at the young foxes, raised a wineskin, and refreshed himself with a gurgling draught. Suddenly he beheld us, and tying the neck of his pigskin bottle, stared at Vaini with frightened eyes, and said in Latin, "Good luck to you. Salutem! May you sneeze pleasantly!"

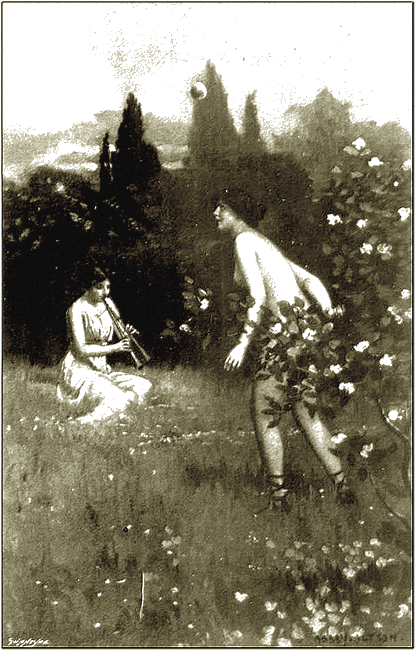

I have spoken of the lady lilac bush which to this day stands at the angle of the Villa, and whose pink foliage was now the last to fade. Its flesh tint, suddenly catching a richer colour, melted into the figure of a young woman, as though the tree were transforming itself to human form. Her fare was fine and resolute, and at the instant not quite revealed, nor yet all hidden—she seemed the poem one never forgets.

She was clad in a seamless pink tunic that fell to the knees, draping the figure it revealed—a figure beautiful as that of Diana whom the Ephesians loved.

She was clad in a seamless pink tunic that fell

to the knees, draping the figure it revealed—a figure

beautiful as that of Diana whom the Ephesians loved.

Her hair was fastened at the back with a tiny arrow, and I remember smiling at my thought that its rose-flushed golden splendour is called in France soleil couchant. From within the building came the sound of a double-octaved harp, such as the Egyptians knew, played very slowly; and as she listened to its vibrant notes, her statuesque arms were carelessly touching the soundless strings of an imaginary instrument. The music was a lyric of dreams,—of the mating of those phantom shapes wherewith the ancients peopled their world; of flowers, and the secret of dawn, and the murmur of awakening woods.

Then with a cry of surprise she beheld us, and ejaculating words I distinguished imperfectly, came forward with eyes fixed upon the onyx Vaini held.

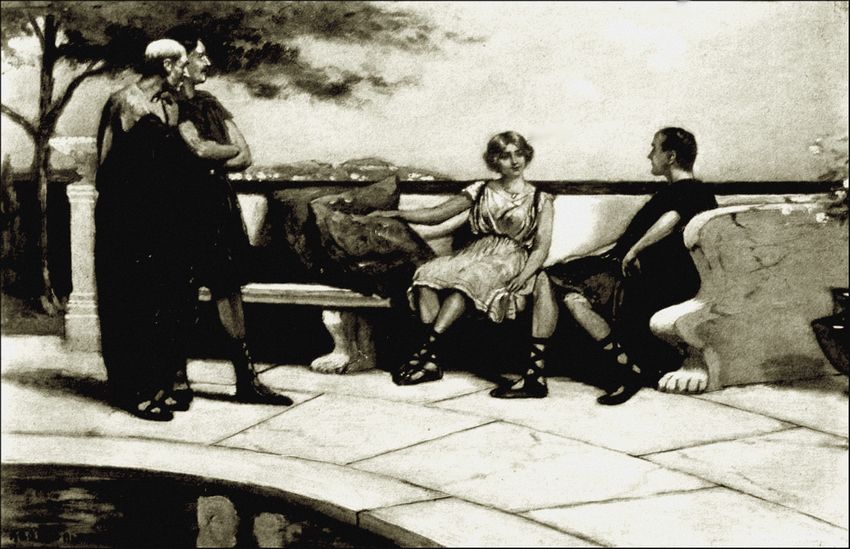

HER voice brought two men from the interior of the building, who halted at sight of us. One was a lean, elderly individual, pausing with grey head tilted eagerly forward. His mouth was bent awry and twitching, revealing three or four broad yellow front teeth; and as he stood moistening his lips, it was easy to see that in his bewilderment he knew not to which of the gods to offer himself. The other was a young man of effeminate appearance. His handsome face was insignificant, clean shaven but for a small moustache, and his cheeks were slightly rouged. It was a face which, although immature, was grooved with lines that told of furious living. About him hovered a fragrance of cosmetics and spiced wine.

The girl turned towards us with a smothered titter, crying in Latin, "Come, father, look upon them; there is no danger. Decius, come. I wonder what language they speak—what nation wears such ugly garments! Januarius, do not stand gaping, but bring a skin of wine; the younger barbarian looks pale: sec, father, it is our Mist Stone they have found and brought back."

I observed the girl attentively, and listened to the name Puteolana, by which the men addressed her, and which could have reference only to her birthplace, Puteoli. She moved with athletic grace, as unembarrassed in her light attire as a faun would have been in his. I gazed upon the shell-heart pink of her skin, the straight eyebrows almost meeting, the rose-leaf lips curving in laughter, and read in her face the languorous poetry of an indolent life. At her summons her companions advanced, and the elder, speaking with droll earnestness, said to us:

"My name is Appian; this is my daughter Cythera; my vocation is to cast a thread from the familiar to the unknown. Am I not an Augur? Salve! I wish you joy. To speak with a welcome guest is better than broaching a wine-cask. It is distinctly before me that something is about to happen—that it is brought about by our recovered talisman—that to us, as to you, this day will almost seem real."

I listened to these phrases, spoken in the purest Latin, with a consciousness that by the strangest crook of my tutor's craft he and I had been translated to that visionary land of fine light and subtle dusk we call classical. I caught the meaning of what was said with tolerable readiness, albeit my verbs had grown rusty since the gerund-grinding days of thirty years before. In the conversation that followed I was occasionally forced to use Italian, now and then a phrase of Greek; more than once I was wholly at a loss.

He who announced himself an Augur, lifting his eyes in a careless sweep of the heavens, now clapped his hands for dinner, as was doubtless his noonday habit. The hunchback Januarius, who had been standing watchful and doglike in the shadow—a shadow that seemed to me the gathered dark of ages—adjusted a curtain drawn half way down the atrium as we entered. At that moment Vaini thoughtlessly produced a silk pocket-handkerchief and blew his nose, an action that excited the wonder and amusement of the Romans, as did the novelty of our pockets. While his hands were occupied I seized the opportunity to relieve him of the magical onyx, thinking I might presently have grievous need of it.

Before us was an encrusted table spread with a silver service. Near it were sculptured lounges heaped with cushions. I noticed the goldfish in the impluvium, the hanging fourfold candelabra, the crystal flagons and glazed amphorae. Against the wall stood a diminutive altar whereon reddened a flame of burning apple-wood. The master of the house sprinkled it with wine, the Roman world even in its decadence preserving the ancient veneration of its ancestors.

"You might think those kindling twigs," murmured Decius, carelessly cracking a nut, "yet, if you look closer, they are only uncertain certainties, grown quite brittle now, and half a dozen promises that failed,—look with what iridescent blues and greens they burn!"

Two girls, waiting to serve us, stood motionless against the triclinium wall. At the sight I realised, as never before, that life, however filled with the glory of nature, seeks its finest inspiration in the form of woman. Near by was the Egyptian harp which one of them was touching as the lilac tree faded. Decius seated himself, and in reply to my inquiry informed me that what I had heard was a hymn to Dionysos, adding, with an irreverent laugh, that within it was hidden some such phrase as the Immortals wove treading the winepress.

"They are Spartan slaves," he added, with a scrutinising glance at the maidens: "full-blooded animals of many moods, fervent and flushed after their meat soup—looking their best when reposing on the grass, a drowsy heap of muscular pink flesh." These words reached the ears of one of them, for she turned aside with tremulous lips. At this token of weakness Decius laughed aloud. "A beautiful woman's anguish is a morsel for the gods," he whispered, dipping his finger-tips in a bowl half-filled with some spiced liquid set apart for his own use. The rest of us moistened our hands in beryl water while the wine was poured. No two cups were alike, Vaini's being a silver goblet, Cythera's a crystal chalice, and mine a deep saucer of mother-of-pearl. Excitement had made me so thirsty that I emptied it at a draught.

After boiled eggs and the roe of a lamprey, a rams-head pasty was set before us, which Decius, with a sarcastic nod towards our host, called Shepherd's pie. This name in connection with Appian afforded him much amusement, and seeing me puzzled, he added, "If we told one another the truth, who would not wish to die!"

"My cook is Sicilian," remarked Appian, splitting an egg. "Let me recommend that chicken—it is tender as a lover's glance. If," said he, turning to Vaini, "you wish to buy a villa, I will sell you this for a paltry four hundred thousand sesterces, and you may take the Spartan girls and my cook at cost. You could find no better point from which to observe the fire-shot line of yonder smoky mountain. And yet," he added, with a twinkle of the eye, "I cannot rid myself of the thought that all we now behold is a mutual hallucination. Am not I a reader of dreams?"

The repast ended with a dish of truffles stewed in cider, followed by cheesecakes and African honey. With muttered ejaculations to the gods, Appian laid a rose upon the altar, saying, "Now that I am old, what is left me save the wild rose of my youth? Ahime! how quick doth the cut laurel fade!"

Deems watched him with a contemptuous smile, and turning to me murmured, "How must Cupid laugh as he wings his arrows, till like Appian he groans to find them broken!"

"Or rather," retorted Appian, turning angrily upon him, "how often Cupid never wakes till Psyche kisses him good-bye! Young lovers, now-a-days, are not what they were."

We returned to the atrium, whence beyond the lustre of the pines I gazed seaward, and beheld with emotion the surf and sunshine of a bygone age. It was more wonderful to look upon than a newly discovered star. I ventured to ask Puteolana if I might see the peristyle I doubted not extended beyond the triclinium; and when we reached its portal I halted, arrested by the most marvellous sight it has ever been my fortune to behold. Before me opened an enclosure filled with flaming red and yellow poppies. Beneath the tasselled knitting of vines were frescoes rich as the colour of words. On a border of turf sat one of the Spartan girls, breathing into a flute such piping as the vesper sparrow's song—a broken note of things once beautiful. She seemed the heart of Greece brooding remembered melody. The other paced to and fro lightfoot as the nymph that vanished before her pursuer. She was playing ball, tossing it over her shoulder, and in the runs and turns of that leisurely movement kept time with the music, dancing a measure that might have been spun in the wildwood. Beside her on the greensward glided her shadow—and to this day I hear the faint reverberance of their sandalled feet. Suddenly she paused at a fountain wherein the water trickled, and drank from her curving hands.

She was playing ball, tossing it over her shoulder, and in the runs

and turns of that leisurely movement kept time with the music,

dancing a measure that might have been spun in the wildwood.

Cythera grew impatient at my delay before what to her was commonplace. Her attitude was that of one who waits a signal, and it flashed upon me that she had waited thus for ages.

"You have come at last," she ejaculated, "after keeping me watching... how long! knowing all the while that some day some one would find our Mist Stone, and that Mercury would whisper in his ear. You might have guessed, even though you could not count the years."

"How was it lost?" I asked.

"A year ago I was betrothed to Enceladus—you have heard the name of the Centurion who slew the Imperator Carus. Last summer he went with the Tenth Legion into a distant land. It was my father's wish that I should marry him, and I could only obtain that an oracle should speak."

The Greek girls were standing near, listening so intently that the animal nature which looked from their statuesque faces was quelled. Cythera motioned me to the end of the garden, and added, with a laugh at which the crimson woodpecker lifted its wings and turned its head askance, "Our answer, written in characters you might have mistaken for mine, declared I should be his who came with the Mist Stone in his hand. Appian was so angered that he flung it into yonder well."

"And Enceladus?"

"The Tenth Legion has been overwhelmed and destroyed. Enceladus was a brave man; many months' silence followed; no doubt he perished. I shall never again hear that funeral march he loved. But we waste words. Such an opportunity comes not twice,—let us away!"

"It seems," I answered, scarce able to repress a smile at my predicament, "that it is I who have fulfilled the oracle. And now—away whither?"

"Whither you will, so it be far from Decius."

"What then to you," I ventured to ask, "is Decius."

"Alas! I am to marry him. Oh, you who have the talisman, the latchkey to every soul, show me a way of escape."

"Twice betrothed," I exclaimed, "and both times unwillingly!'

"It was but natural," replied the girl, "that Decius should take the place of Enceladus,—is he not his son? Yet rotten grain makes poor bread. As for the other, who cares now the manner of man he was! I shall never again come, tame to his whistle. I hate soldiers and fighting men and their heavy-handed ways."

I stood before Cythera, listening to the crickets trilling in the grass. I divined in her the Roman nature, tender, passionate and sensuous. Her hand was upon mine, and a beautiful woman's touch is always a caress. Some such careless pressure often draws a man and woman instinctively to one another; and conscious at that moment of the link of a masterful attraction, I remembered the "curious knot" which Circe taught Odysseus. It was a hand firm and strong to send the discus whirling. I looked upon her hair, turned ruddy in the sun-blaze, and beneath that sleeveless tunic divined the contour of a splendid body. I gazed into the flame of those intense eyes—and that instant's swift remembrance of my duty to Vaini remains to this day the splinter of an arrow in my heart.

We were standing at the cliff-side; and pointing to the Italian felucca, which in keeping with the rest had changed to a Roman galley, she added: "Yonder is the ship we call To-Day. It must presently pass the horizon and be in sight of coasts beyond the Herculanean pillars. Let us hasten to those dream-fields beyond the sunburnt West and be happy. We will turn upon Fate as Diana turned upon Actaeon. He not ungrateful. Is it so stern a lot for a stranger, lost in the unknown, to find one like me awaiting? Come, I will give you a fine white tunic, one of my own, and we will cast these hideous garments into the sea."

She paused, and the deep-spoken word, the immortal word, trembled in the silence—a silence as hushed as the breathless instant that falls between prayers. With an effort I controlled my emotion, and answered, "The onyx is not mine, but another's, and how can I betray his trust!"

She moved away at this ungracious reply, and pointing to the cloud-shadows flitting over the sea, "The things we wish, yet do not wholly understand," she exclaimed, "are there written, fine as the Sibylline meaning of October leaves. Who does not divine behind them the phantoms that gaze on us and beckon ere they fly? At this moment all the birds in the world are singing, yet something whispers me that this meeting is only for an hour—that I no longer belong here... that I must go."

At the word Appian, followed by his slave Januarius, hurried into the peristyle. Their faces had blanched, and they were talking excitedly, the dwarf crying:

"I warned you, Master, it is a grievous sign when the flame grows cold."

"It was but yesterday," moaned the Augur, "I touched an egg in the nest of a brooding bird, and now,—what a fistful!"

Cythera needed not to be told what had happened. "It is Enceladus—the dead come back!"—she exclaimed with fine intuition, and in her quickened breath was the fever of hate. Pushing me into a cubiculum, she murmured cheerfully, "Be perfectly quiet,—no man need die before his time."

It was a tiny chamber, lighted by two panes of glass and half filled by a gilded bedstead. I seated myself near a dressing-table, whereon were spread a mirror of dark purple glass, some ointment pots, a dice bos, and a wax tablet and stylus.

For some moments I had missed Vaini, and now, as the new-comer strode in and tossed his cloth hat upon a table, I was stupefied to behold in him my tutor transfigured to the semblance of a Roman. And yet it was not my Nineteenth-Century companion, but his prototype, the philosopher changed to an impressive embodiment of physical power, ruthless as a scythe.

He wore a corselet of embroidered silk over a tunic decorated with richly ornamented bands which reached to his knees. From his shoulders fell a mantle of gossamer texture, and his feet were shod with leather buskins whose soft lining served in lieu of socks. By a strap over his shoulder hung a short heavy sword like a hunter's blade, on whose hilt was modelled a tiny boar, the emblem of the Tenth Legion. His hair had become close cropped, his face suddenly bronzed, the mouth larger and thinner-lipped than Vaini's. Only the same soul of swiftness looked from those far-seeing eyes, and in them I read the indomitable will that through immortal centuries had chased many a golden-dusted King.

Caesar's narrative of his conquest of Gaul is the finest exponent of force ever put upon paper. Between the lines of that recital of heroic science we perceive that when the tragic side was weighed the rest counted for nothing. What cared the Tenth Legion, wiping its crimsoned sword, for aught beyond its sanguinary autograph! The face of Enceladus said, as distinctly as a page of the Commentaries, that the more clean strokes are given the fewer will be received. Vaini a Centurion of the thunder-throated! Only to look upon him one knew that to yield to less than Fate was not in that forthright soul. It was indeed Vaini, but cast in an antique mould, with a new look of self-centred stoicism, for he had suddenly become a soldier, and a soldier lives near to the heart of great things.

I glanced between the curtains, and saw him speaking to Decius, his son, who drew back before him.

"Grown hair on thy lip," he sneered. "By Cerberus, thou shalt grow a tail as well. Thou art dumb as the desert. Augur," he cried, turning to Appian: "bid your cook serve me a slice of bacon in a mess of stale peas—I have come far and am hungry." Then, throwing himself on a cane lounge, he added: "Tell Cythera to come hither and sit by my side."

THE master of the house curtly dismissed Januarius to the kitchen. Bacon and stale peas were easily provided, but I smiled at the evasion which followed the summons of Cythera.

"Enceladus," cried the Augur, with demonstrative gladness, "you are thrice welcome. We have heard gruesome things... of the Legion surprised in the Pannonian forest, of a fighting line formed amid quicksands, of the encircling enemy. Months went by, we feared the worst, and in thinking of you my life's colour faded to ashen grey. How well I remember our last talk in this garden! I told you Puteolana was loath to leave her childhood's home, and offered to sell it you for five hundred thousand sesterces. Now, ere she comes, let us strike hands upon the bargain, and it shall be yours to greet your affianced with the word that yonder sea of sunshine, these sweet paths, this wistful green, remain hers."

The soldier listened with disdain. "You have an upreaching mind," he sardonically answered, "and so have I. The girl shall not come empty-handed; the Villa shall indeed be hers, as your gift, together with five hundred thousand sesterces. I should not have asked so rich a dower for her, but be that as you will. Thus much being agreed, give me truce to ambiguous grumblings, and tell me why it is I still await Cythera."

"She comes, Centurion; she but adorns herself; girls that go to meet the lover of their choice must needs paint the rose."

How keenly at that critical moment I remembered Vaini's anticipation, that albeit the incidents of our adventure might appear as mere remembered happenings, yet the shapes to be encountered were capable of proving dangerous in the extreme! I dared not look through the curtains of the cubiculum, but heard Cythera's sandalled feet, and divined the embarrassment of her meeting with Enceladus in the presence of his son. This was not lost upon her first betrothed, and he came to the point with characteristic directness.

"Girl!" he exclaimed, "you will end by making me believe that ambition is the only aim. Through a dozen misadventures mine has been the patience which has known how to wait. While I have made my slow-trod way hither something overhead beckoned on. Through the long retreat I mused upon love's unfoldings. In the most desperate hour I cherished the thought of you—till now the sight of you chills me."

"Girl!" he exclaimed, "you will end by making me believe that

ambition is the only aim.... In the most desperate hour I che-

rished the thought of you—till now the sight of you chills me."

An instant's silence followed, then the Centurion's chair was overturned and the pavement rang with his step.

I have mentioned that in my first sight of Appian's Villa a hound stood watching the gambols of some foxes. It now advanced to the door of the cubiculum and looked in at me through the half-drawn curtain. At this indication Enceladus sprang to his feet, crying: "To how many things dogs listen that are beyond reach of human ear!" Then the drapery was flung aside, and the Centurion of the Tenth stood regarding me with no friendly eye.

His likeness to Vaini was so absurd that I might have taken the figure for a martial transformation. Even the manner and gestures were so strikingly familiar, however seemingly grotesque, that I bit my lip to hide a smile.

"You laugh!" he ejaculated angrily. "You dare to laugh!"

His menace and the rhythm of those sonorous vowels clutched my heart. Here was Vaini about to strike with the very fate whereof he had warned me. With this astounding metamorphosis before me, it was useless to seek to make myself known, and I shuddered to think of the consequence of an incautious word. For a moment we stood observing one another, while the afternoon's lengthening shadow crept towards me with death lurking behind. It occurred to me with gruesome distinctness that had I wished to commit suicide I could not have advanced more accurately to my destruction.

"I find you alone," he exclaimed; "yet Appian says there is one with you. Where is that other?"

I longed to blurt the truth: "It's you, now so strangely travestied, I came with," but stifled the words and answered, "I fervently wish he stood in my place."

"Who is he?" asked the Roman, with Vaini's habit of clasping and unclasping his interlacing fingers, "and why wish him in your place? Speak up, man: your discourse lacks wings!"

"Because his is a spirit kindred with your own. His life has been spent unravelling tangled skeins, and like you he has dealt with forces and conquered them. He insists that the only thing worth living for is bringing the impossible to pass. He has high courage and a neck unbowed, for one who has spent a lifetime among the Immortals fears no man."

The threat faded from the face that was so startling, yet so familiar. "Faltering feet sometimes reach their goal," he answered, "and yours may not be far astray. Walk with me to the end of the garden, and tell me who and what you are."

"I am born of the school of Epicurus," I replied, "and with Horace I take my portion from the marrow of the day."

"What is your name?"

"As a boy they called me William the Silent."

"You have been brought from some remote country and evidently from another age. Who can say what drift floats from one sphere to another! Does Rome still rule?"

"The things that made Rome great are still supreme."

"Yet I warrant it is still the same old empty-barrel world the Caesars found it?"

"The stars continue to repeat their crystal prophecy; we still gather wild grapes in our neighbours' vineyard; the wood-nymphs beckon and the wines still run. There is no change save a frothing buzz and clank of wheels."

He stood listening attentively, plucking a flower asunder whilst gazing towards the diamond-dust sunshine across the Bay, and smiling as from Surrentum's rocky bosom the bugle-call of a marching cohort smote the air with triumph. Perhaps that sweet exultant summons seemed to him an omen of good. Superstitious as were all great men of antiquity, and knowing their religion to be fairy lore, they believed in and dreaded fate.

"You talk like an artist," he said, as with a sudden inspiration, "and the gods have sent you here to do me a rare service. Can you be depended on?" he asked, tapping me friendliwise on the shoulder.

"I am no less trustworthy," I answered with decision, "than the Italian Government itself."

"I have had enough," he began, turning full upon me, "of the attack and defence which make up a soldier's life. I hate the city, with its weary, envious, disappointed swarm. I have had overmuch of things that come and go like gilded galleys. I wish to fill a beaker with the richness of solitude with Cythera and drain it to the lees. For the great world, it will content me to be an onlooker—a panther crouched on the bough. Age has its October sunshine, when I can sit at home with Homer, counting the gold of what is past and laughing at the insolence of the Forum. But there is a fly in my wine which you alone can remove. I am plagued by an undefined misgiving that Decius—my own son, mind you—looks amorously upon the girl to whom I am betrothed. Wherefore I wish you to exercise immediately this art you understand so well, and transport him with yourself to the far land whence you came."

"What am I to do there with Decius?" I ejaculated, aghast at the demand.

The Centurion, still clasping and unclasping his hands, eyed me with amusement. "You will be great," he said, "even in small things. Take him to your sanctuary and be to him as a younger brother. Yield to him in all things, for, like me, he is wont to rule. If thwarted he will surely kill you—not that one of your courage shuns death, for it is a man's life, not his ending, that matters. I do not wish to harm Decius—is he not my son? But he is horribly in my way—wherefore in Jove's name take him and go."

"Vaini!" I interrupted furiously, "much as I love you, this is beyond a jest."

The Roman heeded not, adding, with my tutor's Dantesque twist of the lips in his smile: "Things are sometimes adamant, but men and women can be bent or broken. I will bring Decius, and you shall take him by the hand. You understand the use of the talisman, which consists in fixing the thought upon a star called the Weaving Maiden, which possesses the Secret of the Seven South Streams. Cast the stone into fresh water—not salt—and together you will vanish." So saying Vaini turned with a careless nod, and a departing nightmare leaves no profounder relief than I felt at seeing my Centurion-tutor stride lightly away.

At the sound of a softer footfall on the grass, I glanced behind me and beheld Puteolana. Something drew me irresistibly near, with an impulse grown suddenly tender. Upon her face was the radiant pagan delight in the health and beauty of the physical body. In that enchanted hour she seemed the incarnate youth of all antiquity—an embodiment of ancient graceful things that I had mused upon and learned to love, and that I now found bright-eyed and golden-haired and beautiful beyond the poetry of thought.

"My father seeks you," she said, with a ripple of mirth. "You are to buy this villa, after which you can bid both Enceladus and Decius begone." Then with a merry laugh she added, "It is to be yours for only six hundred thousand sesterces,—he swears, by Hercules, it is given away."

It flashed upon me that such a possession was indeed the glistening jewel I had sought through half a lifetime. With unaccustomed audacity I caught Cythera's hand, and, surprised at my boldness, murmured,—"Flowers, music, wine... this splendid sunshine... and you!"

"My father's counsel," she interrupted, a sudden passion thrilling the undertone of her voice, "is not mine. You have come from some rare domain, beyond the edge of things we know. You are here in imminent danger between two violent men. There came with you a sinister-visaged scholar, a half-fed, mournful shade. He has vanished, and what has befallen him? Are not you in like jeopardy? Wherefore, for your own sake, escape while you may, and thank whatever gods there be."

"Can I forget," I answered, "that your peril is greater than mine, or could I leave you to face it alone! To what extremity may not Enceladus go when he learns that you—his affianced when he went hence—are now, on his return, betrothed to Decius?"

The girl stood silent, her face darkening a little at my words: perhaps this was but one of the subtle veils the afternoon was leaving. At that tranquil moment I divined the salutation the passing day receives at sunset from the setting sun.

"It seems a kiss," I whispered, "when twilight touches the dark—a kiss thrilling with thought of happy things past or to come. For whom the omen, if not for you and me?"

As I spoke the woodpecker in the atrium tapped on his perch—a solemn sound, as though some guardian of the bourne wherein I was trespassing had warned back an intruder.

Instinctively we glanced through the half-drawn curtains, and beheld Decius approaching, doubtless seeking to elude his father. At sight of me his sullen face lightened, and he addressed me with words of intense emotion. As he spoke, Cythera moved to the Egyptian harp and ran her fingers over its strings, the fine accords seeming a setting to his words. Once, years before, I had heard a song within a song, wherein the double harmony rang true, and the meaning of the one gave profounder significance to the other. Each was distinct in melody—each beautiful as a shower of falling stars. Now, though the words and music were interwoven, I read in Cythera's eyes the veiled import of that heart-beat cadence, and understood that she too was speaking with wistful entreaty—faint as the whisper of falling leaves.

The persuasive phrases of Decius disconcerted me. I should not have looked for such warmth from one whose shallow selfish nature stood self-revealed. Yet I have rarely listened to a more earnest appeal, a trifle theatrical in its declamation, but urged with force and with a grace of rendering to which none could have listened unmoved.

"Let us consider," I said, "precisely what it is you wish me to do." At this he clasped me in his arms—and as he did so, Cythera walked away.

"I alone," he ejaculated, "believe you human and not the phantom Appian says. The art which brought you here can transport you back whence you came, and whoever touches you at that instant will likewise vanish away. What I ask is this. Take my father presently by the hand and will him with yourself to Ultima Thule. My father is not too old to be useful; there are years of labour in that iron frame. Remember it is you that have brought upon us his calamitous presence."

The truth forced itself upon me with startling distinctness that I was but an unbidden stranger among these people, an unwelcome visitor at that. Their hates and loves were not for me to meddle with—any heedless trifling might be the means of irreparable wrong. My eyes rested on the wall opposite, where, painted with marvellous foreshortening, the Laocoon struggled with his serpents and turned upon me an anguished face. I glanced back at Decius, and beheld the same tormented spirit.

"If," I said, quite vanquished, "you bring the Centurion to me and place his hand in mine...."

Then, as Decius nodded, I remembered Cythera's harp-song, and my voice fell.

THE day had lapsed to calm, the grape leaves mellowing on the sun-browned wall, the sea reflecting a cobalt blue. Beneath the cliff were foamy shallows grown almost still, and across the Bay Vesuvius was faintly stained with sunset shafts, that changed its white wreath to a rust-red smoke. Behind me stretched the upland woods, where to this day dwell the cool winds and the silent shadows. In the repose of such a scene, may not we deem that something of the inspiration overhead—the flash of ascending wings and amorous whisper of leaves—passes, half felt, into the life beneath!

"Yes," murmured Cythera's voice, "though faint as a breath-stain on a mirror, they shall outlast the things we shape and fashion for eternity."

To my wonder the tears were starting from her eyes. At that instant I heard the chimes of dear old Nineteenth-Century San Vincenzo, followed by the droning of a priest before the altar where floats a glorified Madonna. And to this day, when church bells chime and anthems swell, I see Cythera's face transfigured beyond the tears of earth!

These familiar sounds of modern Sorrento startled me with their evidence that the figure before me, and the Roman villa and the metempsychosis of Vaini were hallucinations frail as those marvels of alchemy a word sufficed to shatter. Yet how vivid the illusion! How present in Cythera was the imaginative realism of the antique mind, how natural seemed her physical being, even to the white scar on her arm where in childhood the flesh had been lacerated by some animal's teeth! We stood thus, looking into one another's eyes, while the brief moments flew all too quickly. At her neck hung an amulet bearing the Greek word Ευχυχα, Be of good courage, and this I raised to decipher in the sunshine. As the hours passed it seemed to me we came to speak a language familiar to us both. How often have I sought to recall its fluent phrases, wherein the meaning leaped almost before the spoken word! And standing thus beside this unhappy girl, the thought flashed in my mind, After the expectancy of years, must her waiting be all for nought? The onyx was in my hand, and its use had been explained. Now that Vaini had taken on a new and fearful nature, I had no stronger wish than to escape him. Suppose that, instead of awaiting his return with Decius, I took Cythera's hand and willed us both away! Could I but breathe into her being the soul of an intense desire, might not I draw her from one world to another—even into the refuge of my own life?

The sun was sinking in the emerald sea and sparkling in Cythera's hair. About us was that twitter wherein mating birds exchange their gentle promises,—not as feigning poets that sing for others, but in a passion all their own. Beside me was the splash of water falling from the fountain's marble edge, and bearing to my fancy a meaning of musical enchantment.

"Puteolana," I murmured, "you say that you have waited many lifetimes,—who can affirm that I have not likewise been awaiting you, unconsciously, as darkness waits the dawn? Are not the paths of the Immortals at the edge of the clouds? Wherefore let us master Fate and gain our own. Link your destiny with mine, and far hence together we will watch the twilight weave, and whisper to each other the words that none but lovers speak. By Hera, to whom do we belong if not to those we love?"

"It is so strangely sudden," cried the girl, drawing back, her face filled with the softness of Italian summer.

"The best things in life," I answered, "come swiftly and unaware."

"Dare I trust myself with a new-found friend without so much as waiting for a father's benediction?"

"If you delay," I replied, "your father will give you with his benediction to Enceladus."

Her hand was in mine, and I had raised the magic stone, and was about to plunge it in the impluvium, when a violent crash of something overturned resounded.

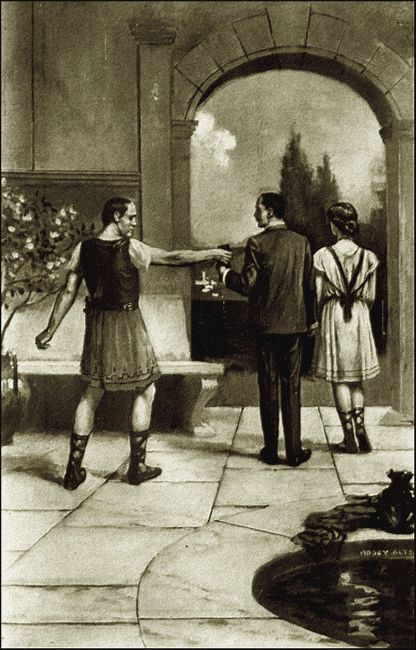

At the end of the peristyle a blue bowl of roses had been thrown from its pedestal, and on the ground beside its fragments lay Decius. Before him stood Vaini, his face ablaze. It was easy to guess that Decius had revealed his own betrothal to Cythera, that the Centurion had struck his son violently to earth; and now Decius arose and paused menacing, vindictive, evil-eyed.

Was I about to behold a tragedy of Roman days!

An angry flush suffused the young man's countenance, and there were flecks of bloody froth upon his tunic. Appian, with white frightened face, had tried to separate the struggling men, and now, seemingly beside himself, was spinning round like a mad dog. Near by stood the hunchback, convulsed with fiendish glee.

Then with deadly swiftness Decius fled away, reappearing at an upper window with a Numidian bow and arrows. One of these he fitted with deliberation to the string, and discharged it as Vaini turned, the shaft striking edgewise and sinking through the face. A second pierced the shoulder as the Centurion sprang towards the stair and drew his sword. The sound of a scuffle followed, then Decius was flung headlong from the window, and lay where he fell.

"Habet!" cried Vaini, calmly wiping his sword. "Habet!" he repeated, with exultant pleasure, as though the word rang with joy. Then he descended to the fountain, and carefully bathed his wounds. Suddenly he straightened with a slight convulsion... the Numidian arrows were poisoned.

My eyes were riveted upon the pallor of his face and on his quivering lips. I was about to witness how the last of the Tenth Legion could die without fear, repentance, or benedicite.

As though wondering at my presence his lurid gaze fastened upon me standing with Cythera's hand in mine, and the talisman in my grasp. Then... he understood, and with a final effort came towards us, tore the onyx from me and sent it whirling far into the sea. I heard a deep sob wrenched from his fainting heart, then his hands clutched at the overleaning myrtle, and sinking to earth he covered his face. What triumph must have filled that last conscious instant, for though Puteolana was lost to him, she was equally beyond the reach of Decius or of me!

Then... he understood, and with a final effort came towards

us, tore the onyx from me and sent it whirling far into the sea.

Where the stone fell among the ripples I seemed to see a flash of fire. At its contact with salt water the Pompeian atrium shrivelled with a fluttering roll. The ground lurched like the deck of a sinking ship, and I staggered as though struck by a wave. I was conscious of having touched the revelation that centuries have groped for—yet fallen one step short of the goal. Instinctively I turned towards Cythera, and for a bewildered instant—the space of one long heart-beat— gazed fixedly upon her. I knew it was my last look upon the face I should remember and dream of, but never again behold. It was the moment's pause between sound and silence as I listened to her murmur-voiced adieu.

"You will come back for me some day," she whispered. "I shall be near—no further than the vanished morning from afternoon. In some life, somewhere, you shall find me again."

The words died, and her last movement was an outstretched hand,—then the brilliant figure faded, and in its place the lilac bush of Vaini's garden appeared, its sun-shot branches suddenly radiant with extraordinary splendour.

I WAS lying on the ground, and beside me sat Vaini staring vacantly at the sea where a moment before he had cast the Mist Stone. The resemblance remained so strong that for an instant I thought it was Enceladus. But the Roman Villa had left no trace, and in its stead rose the modern house and orange grove. Near by waited Pasquale, holding a watering-can, which he must have emptied over me, for I was half drenched.

"Thank God, dear Master," I exclaimed, "you are still alive! Oblige me by looking behind the lilac bush—Puteolana may still be there. And yet I fear the sunset..."

"Sunset!" impatiently echoed Vaini,—"it is high noon: the clock marks a quarter-past twelve."

"Cythera will vanish while we talk."

"Puteolana... Cythera... two young women! Companion of my studies, how often have I warned you against this taste for doubtful adventure?"

"There was but one—you took her from me an instant ago. And how can you say it is high noon, when a moment since the sun was sinking behind Ischia! Oh, Vaini, such an hour as I have spent would redeem the commonplace of a lifetime."

"The sun is indeed warm to-day," assented my tutor, with a soft whistle; "and by St. Peter it is a dizzy world. Friend of my soul, you should not take two cups of coffee at breakfast."

"An occult force," I interrupted, "lingering pent up through the ages, has been brought to life. It is the long arm of coincidence."

"Carissimo, it is the long bow of coincidence, but the bow if bent too far will break. Pasquale, throw more water over his head."

"It was not a long bow that Decius bent, but a short one, and the arrows were poisoned. One struck you in the face... strange it has left no wound. How many hours did the experiment last?"

"Hours!" murmured the wise man, laying his hand upon my pulse—"it is but fifteen minutes since it commenced, and five since your folly ended it. We had just brought the Roman Villa into view when you snatched the onyx from me. Then you rushed about, talking and gesticulating wildly. Pasquale and I were struggling with you till you flung it over the cliff and reeled to the ground."

"But you," I retorted, "were there with me, disguised as Enceladus. At one moment I feared you would draw that short sword and do me a mischief."

"I almost wish I had," replied my tutor, "before you cast my treasure into the sea. There are many border-lands, and you may have slipped across one of them for ten minutes. If indeed you penetrated the atrium of the ancient world, it is but too evident that you have destroyed its signboard. Wherefore not another word, or you will rouse Homeric laughter."

IT is eleven years since these things happened, and now that Vaini is no more, and the sun-resplendent villa that he loved is mine, I walk with him in memory amid the half-light of its orange grove, and trace again those darkling ways through which he sent me an unmeasured distance.

I study the wall-bound winding lanes of my garden in the aspect of all hours and seasons. I sit beneath the myrtles, where the cloister dips, and watch the sparkle upon the under-water blue. The sunshine paints its arabesques upon Vesuvius. Above the Monastery buttress hang sprays of silver shaft and farewell summer, weaving their tendrils in tapestry. Here for a thousand years olive after olive has grown, each in turn uplifting its boughs of velvet-grey. From a distance comes the vibrant piping of a hermit thrush, and I remember the thrill of the Spartan flute and the broken heart of its music. Day mellows, and flushes Posilipo and Nisida and all these opalescent shores Poseidon loved. There is in the air a sense of faint, far voices. Overhead, at night, the great star garden kindles with a meaning the ancients thought to read. Yonder, amid the windrift of last summer's leaves, is the fountain, unearthed when the Caserna del Gesł was building, four hundred years ago, wherein I saw the Greek girl dip her hands and drink. In the twilight of early morning those Spartan maidens still scatter my borders with wild violets; each May-time the poppies I remember touch its greensward with their Roman gold.

Idling amid the orange trees and ilexes, I am conscious that I stand amid the Poets. Through many a long mid-afternoon the sea beckons with white hands and I mark the flush fade upon the enclasping hills. A voice speaks; for who, appealing to Nature, goes wholly without response? Yes, a voice speaks, for the coralline lilac bush remains the living inspiration of my garden. Through the drapery of its pink flakes I first beheld Puteolana, and to this day I instinctively glance behind its crimsoning spray with a thought ever sweet and wild. The branch her eyes beheld in bloom is blooming now. The breeze blows a flavour of romance through those fine blossoms, as though they were the living foliage of many faded summers. I cannot hear Cythera speak—her voice sinks across the centuries, ... yet when the song-bird calls—pleading, passionate, irresistible—I turn with sudden emotion. Its leaves renew the touch of flower-soft fingers. And I ask myself if a tree so beautiful, so mindful of the seasons, so responsive to sunshine and to shade, has not some living consciousness—some subtle sense of dreams!

Painting of Sorrento by Consalvo Carelli (1818-1900).

The original Pall Mall version is illustrated with a grainy photograph. —R.G.

Through many a long mid-afternoon the sea beckons with white

hands and I mark the flush fade upon the enclasping hills.

Thus musing, my thoughts fly ever to the bourne wherein I trace that transfigured hour I lived in the ancient world. Half my life has been illumined by the afterglow a day. I fancy Cythera standing where I beheld her as the centuries surged between us. I meditate upon the link which for a moment brought our lives in contact, and delight myself with the belief that, however frail, it is imperishable. Does she too walk these quiet paths at evenfall, and is the Villa as present to her as to me? Or is hers the living reality, and am I but the phantom of a day? A leaf from the tree-top flutters and falls to the ground and I know that when I am dead I shall remember Cythera and the touch of her velvet lips.

— William Waldorf Astor.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.