RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

ON the morning of February 21, 1900, sitting at Professor Vaini's laboratory table at the Villa Sirena, I pushed from me, with a movement of despair, his famous Casquet of Essentials, whose contents I had been studying. That casquet—the master's tool-chest—is in my possession since my tutor's tragic death, and, re-examining its vials for the hundredth time, I am moved to write the story of an experience when, in a heedless hour, I ventured without his knowledge to apply one of its essences to a problem upon which we were engaged. Before me are its tiny flacons, filled by him with curious poisons, that in his marvellous adaptation held, not death, but life and benediction. Fastened in its lid are the compasses and rule and weights wherewith he estimated unknown quantities, and an ivory chart, on whose fine surface he traced that perspective wherein the fateful things of life begin and end.

When at Christmas he invited me to Sorrento, he met me with an exultant exclamation: "I have discovered the theory of a cleaving impetus as powerful as the finest flight of the master-mind." For some weeks thereafter we had been employed upon one of those enigmas of psychical research which seem like some sand-worm shape washed up from the deep of sunken things. A month later he had been suddenly summoned to Naples, I knew not upon what haunted errand, leaving me alone, in possession of his laboratory, where I had spent a week in fascinating study. Each afternoon I travelled farther from the evanescent things of to-day toward undiscovered outposts, and at evening, before the blazing logs, pursued those gleams that from remote ages have illuminated and perplexed the mind.

"Is it possible," I asked myself that morning, "that an amorous passion may continue between the living and the dead?"

As in that instant's discouragement I brushed aside the casquet's phantom world, the door opened, and Pasquale, our custode at the Villa Sirena, handed me a telegram from Vaini, asking me to join him immediately in Naples. It was yet early, and as my carriage sped out of Sorrento, the burnished slopes of Vesuvius were flushed as pearls that glisten in the sun. Above the mountain floated a pink film like a poised almond-flower. I remember how, looking earlier from my window, I had watched the shadows fade as the primrose tints of sunrise kindled, and had listened to the richness and variety of the music of the sea. It was a day so transcendent that its breath trembled with the fragrance of bygone yet immortal roses, and, looking beyond the luminous green, one might have deemed Vaini's alchemic art had transfigured the far horizon to a land of gold.

I found my former tutor at the house of a friend, his features reflecting from the facets of his mind that significance of a being intent upon the goal. "A fighter," Vaini was wont to say, "must possess the fighting edge," and this, through years of toil and triumph, had become traced upon his countenance. I knew at a glance that he was busy upon one of those strange problems whereof he had solved so many—that, as so often before, he had matched himself single-minded against forces vast, uncomprehended, sinister, perhaps death-dealing to an intruder.

"I have sent for you," he began, "because an affair which at first seemed the application of mere ingenuity to the recovery of a stolen object has suddenly become complicated. I wish you to unravel its minor threads, leaving me to concentrate upon the others. Can I depend upon your bringing an unflagging good-will?"

"Dear master," I exclaimed, "my happiest hours have been those spent in the splendid freedom of your service."

"An object," he thoughtfully observed, "renowned through Christendom, and secure of immortality hereafter, after being lost and found centuries ago, has now been lost again. You do not need to be told that I refer to the Holy Grail."

"But the Holy Grail," I interrupted, "or the emerald chalice to which that name is given, has reposed in this city since the sixteenth century, in the possession of the Cathedral of San Gennaro. It is impossible that it can have been stolen or lost."

"Impossible!" echoed the wise man. "Only to think that at intervals for thirty years you have had my instruction and advice, and that after profuse and varied study and experiment you have not yet learned that in this bizarro world things deemed impossible are continually happening. Are you better than an amateur?"

"At least, Professor," I answered, piqued by this rebuke, "my surprise is natural. I have often looked at the Holy Grail, locked in its bronze-bound crystal case, watched night and day by Ursuline nuns. Jealous eyes observed it incessantly, no one was suffered to approach within the rail, and for two hundred years none less than cardinal or king has touched it."

"Of course there was complicity among the nuns," assented Vaini, twirling the big green pencil wherewith in hours of abstraction he drew geometric tangents and ellipses which conveyed a mathematical expression of the subject before us in a language I had grown to understand.

"What interest have we," I inquired, "in the loss or recovery of that curious tazza?"

"The scientific world," he answered, speaking with Italian smoothness, "has doubted the value—even the existence—of my loftiest discoveries. So true is it that Truth is slow in coming to the front. That man may acquire new powers by the resuscitation within him of animal instinct, that the wild creature's method of returning to remote localities may be used in mental processes, that the unconscious operation whereby the brain grasps an elusive solution may be raised to a certainty, are things a decadent age calls visionary. But imagine the effect were they successfully directed to some matter-of-fact business on which public attention happened to be fastened!"

"Professor," I inquired, "what is to be my share in the work? Make it an easy task; I know so little of the technique of these things."

"Carissimo," replied the wise man, "I only ask you to apply what I have taught you of the prime movers to our occult periphery. Already I am on the trace of the guilty, a foreigner aged about fifty-five, quite bald, and, from the movement of his lips, talking very fast."

"You have seen him?" I exclaimed.

"Only in the darkness of the dust film we have used together. He is in hiding not far away, and we shall find him when my indications are perfected. To-day you will oblige me by giving your attention to a shrivelled old woman, an Ursuline nun, who was on watch the night the sacrosanto was stolen, and who knows the thief."

"How can you tell that she knows the thief?"

"Because a minute interrogatory has established the fact," rejoined the Professor, with an amused smile. "She admits having been so overcome at recognising his identity, while the theft was being committed, as to have lost all presence of mind."

"Then why not make her tell his name?"

"Companion of my studies, that is for you to do," retorted my master, the smile broadening to a good-natured little laugh. "She is Sister Eunice, of the Convent of Divine Repose, perhaps once pleasing and attractive, now old, infirm, and frightened. She is English, and you will speak her own language, which I am unable to do. While you can force nothing further from her than moaning repetitions, I doubt not that, if you take her to my Villa Sirena and give peace of mind and good cheer, you may draw forth important clues. Your afternoon is filled with ungarnered harvest. A motive must be supplied, and, as you know, the strongest motive in the human heart, and one that usually loosens the tongue, is a lust for revenge. How that motive is to be used remains for you to discover. Come with me; she is in the next room, ready to go."

"Remove a nun, however old, from the control of her superiors!"

"We have both civil and ecclesiastical authority. All Naples is longing and expectant, and has called upon me to recover its Holy Grail. Take your steps with inspiration, remembering that a woman's nature is really deep where it appears shallow. I shall expect you back in a day or two."

So saying, Vaini opened a door and motioned me into an adjoining room, where, on a reclining chair, rested an elderly woman, whose frail form was robed in the vestments of St. Ursula. She shrank before my tutor's approach, and turned upon me a countenance whereon was fixed a silent acquiescence in fate. It was the weary face of one who has suffered, and as I looked into those dark eyes I was smitten with the consciousness of an intrusion.

She answered my first words in the restrained English of the formal 'seventies, pure of the careless diction of fin-de-siècle days. I noticed that her fingers were carelessly, and perhaps unconsciously, busy with the beads of a blackthorn rosary. During our journey I inquired of her the history of the Holy Grail, whereof I knew little. Was it of miraculous origin, or had antiquity cast about it fables of its own? Had she been privileged to hold it in her hands, and was it in very deed carved from a single emerald?

Sister Eunice answered that she had more than once washed it with perfumed water, though she had never seen it in the full light of day. It was kept in a crystal case before the altar, where the light was chiefly of consecrated tapers. It was supposed to be of Babylonian cutting—a chalice sacred to Baal—and had been assigned to Pausanias as his share of the Persian plunder after Plataia. We are told that he presented it to the Delphic Temple of Apollo. Mark Antony gave it to Herod the Great, who bestowed it as a wedding gift upon the beautiful and ill-fated Mariamne.

This story was interrupted by a rasping little cough. My companion's taciturnity had yielded to the interest of our discussion, and perhaps to the pleasure of escaping from Vaini's interrogatory.

"And after that, my sister, what befell?"

"When Mariamne was put to death it was stolen by a servant, who sold it to Joseph of Arimathea. I need not remind you of its disappearance."

"No," I assented, "nor of the search for it by pilgrims and crusaders. All the world knows that it was found at Lepanto on the Turkish admiral's ship, and that Don John of Austria placed it in the Cathedral of Naples. Professor Vaini told me," I added very gently, "that you know nothing of its theft."

At these words the Ursuline nun averted her face, and gazed out upon the breadth and splendour of the scene before us.

"You are looking," I said, "towards the Roman Stabiae, where years ago I beheld the skeleton of an ancient galley recovered from the deep and brought in to our sunshine, with its shells and tangle dripping, like the secret of a lifetime suddenly revealed!"

Sister Eunice turned and gazed at me fixedly.

"But now," I added carelessly, "we have only agreeable things to think of. We are nearly at our destination, where we shall find a garden spangled with December roses, and that peace without which kings are but slaves."

Half an hour later we were sitting in Vaini's library at the Villa Sirena, the tea-things spread upon his work-table. In my ears rang his words that Sister Eunice was to be refreshed and comforted, and her secret drawn from her unawares. My eyes passed from the shrivelled figure before me—from the face that through half a lifetime had not brightened in the light of home, the hands blanched in the service of others, the lips that had tasted bitter lees. The small ivory box in its accustomed niche riveted my thoughts. It was the Casquet of Essentials whose contents were familiar, though neither Vaini nor I had yet dared use the poisons those tiny vials contained.

An overwhelming temptation presented itself, for success meant a realisation of the ideal of science and imagination. I hesitated before a responsibility wherein a maladroitness might be followed by this woman's death. I was vividly conscious of having reached one of those fateful instants when a resolve which makes for the success or failure of a lifetime must be shrunk from or accepted.

A startling surprise interrupted my musing. On the wall hung an ivory lute of rare beauty, once in long-gone days familiar to Vaini's touch. Sister Eunice rose with emotion, caressing the instrument with loving fingers, and murmuring in a trembling voice—"My lute!"

It flashed across my thoughts that in sending me upon this visionary quest, the Professor had been disingenuous in concealing from me some acquaintance between himself and the Ursuline nun in days when he was not an arch-master of curious arts, nor she a recluse from the world. In the instant's irritation that followed I resolved at any hazard to fathom the half-revealed secret that had thrust itself upon me.

Sister Eunice was so intent upon the ivory lute that she did not see me empty the vial labelled "Urohaematoporphyria Cytherae" into her teacup. The instantaneous effect of the faint aroma reduced me to a drowsy perception that I had been thrown thirty years backward. I must have lost consciousness, for when my eyes reopened the nun's teacup was empty, and the lute-strings were trembling beneath her touch. I tried to speak, but my voice sounded strange and unnatural. She was still standing before me, but the sea air had crimsoned her wrinkled cheeks and brightened her brown eyes. The pallid face had suddenly flushed with exultant youth, and she regarded me with a girl's laugh, young and deliciously spontaneous, rippling from the immortal heart of joy.

I must have lost consciousness, for when my eyes reopened the nun's teacup

was empty, and the lute-strings were trembling beneath her touch.

Then, athwart the twinkling lute-strings, and from the distance of years, I heard the refrain:

Drink to me only with thine eyes,

And I will pledge with mine.

I WAS awakened next morning by a faint odour of hyacinths stealing through my open window—seeming the rich and lingering perfume of dreams.

Yes, dreams of that astounding transformation—of the awakened look of those intent brown eyes—eyes of pride and laughter, and wistful things unspoken and suddenly grown young. She was auburn-haired now, as though returning youth had crowned her with its transcendent halo. The nun's habit had faded in the pink folds of a gown, and an extraordinary warmth and richness and brilliancy had replaced the grey human shadow.

In that early reverie I listened to the undulating murmur of soft sounds without—the rhythm of wings and awakenings. What an awakening had been hers, as Vaini's poison fired her veins, and how with a woman's luminous flash of comprehension she had instantly accepted it, as though the flame of youth could never be wholly dead in a vestal bosom.

We had spent the evening in Vaini's library, and I remembered her shapely sentences sounding across my stupor at what I had done. At ten o'clock one of the Italian maids had shown her upstairs to a guest's chamber, whither her nun's portmanteau had been taken. She had told me her name, Guinevere Godfree, the name of her English girlhood, Eunice being that assumed in her novitiate. Her youth had been unhappy, she added, and our talk covered an interplay of profound emotion. I was conscious as we spoke of things that burned to be said, yet remained unspoken. And now the day stood waiting poised in breathless silence, like Horus the immortal holding his secret with finger on his lips.

It was in Vaini's cloister garden that I found her, walking amid its triangles of lawn, its sky-swung clusters of oranges, its trickling splash of water amid monastic statues and the walls and arches about which age has cast its silver-grey.

It was in Vaini's cloister garden that I found her,

walking amid its triangles of lawn, its sky-swung

clusters of oranges, its trickling splash of water

amid monastic statues and the walls and arches

about which age has cast its silver-grey.

Advancing to me with a careless gesture towards the sun-dappled walls, the climbing sweet-bays and the dilapidated steps, over which a lizard darted, she exclaimed, "It has the sense of having been lovely and beloved for centuries."

"To me," I answered, "it seems younger and more exquisite than ever before."

"The night has gone," she exclaimed with emotion, "the convent night..."

"And the day has come. That is why everything looks suddenly beautiful to us both."

"You have saved me from the shadow and the dust," she cried, "you have given me uplifting happiness, and I have been waiting here to ask you what has happened, whether it is real."

"Last evening," I replied, "we climbed together from darkness into light. Does not the good Book say, 'Come, let us walk in the light'?"

"Light and gladness," she murmured, "how musically the words ring together!"

"It is in the light," I answered, gazing into her liquid eyes, "that flowers bloom!"

My words were cut short by the appearance of Pasquale, followed by a sinister-visaged man, dressed in official frock-coat, who Pasquale whispered was the Provincial Chief of Police.

Guinevere and I divined the purpose of this visit, and, drawn by a common danger, turned with composure towards the enemy.

"I had not expected to find so young a lady," observed the commissary, fixing his astonished eyes upon Miss Godfree.

"I had not expected the pleasure of this visit," I replied. "Will you tell me its object?"

"A sensational robbery has been committed at San Gennaro," explained the official, seating himself in the rustic chair to which I motioned. "The Holy Grail has disappeared under circumstances which point to its acquisition by some millionaire crank. The nuns are suspected of connivance, and one of them, Sister Eunice, was in your company yesterday. You were traced together to this house which I am about to search."

"Search and be... blessed," I answered, "but first show me your warrant."

The document, duly signed and sealed, was produced, and his men to the number of a dozen approached the house. Two remained at the gate, two kept us under observation, two mounted guard over the servants assembled in the kitchen, while the remainder with the commissary made a domiciliary visit through the now empty house. At the end of an hour they had ransacked every room needless to say, without finding either the Holy Grail or the nun Eunice.

They had only been gone ten minutes, when a telegram arrived from Vaini requesting me to join him in Naples with all haste.

My former tutor received me with incisive questions. I dared not tell him of the transformation his elixir had wrought in the aged female commended to my charge, observing merely that she had benefited by a charge of air, and hastening to describe the police official's visit.

The Professor's fine lips twisted in a compassionate smile. "It was not a police official," he murmured, "but the head of the Neapolitan Camorra. An expert might fail to tell them apart."

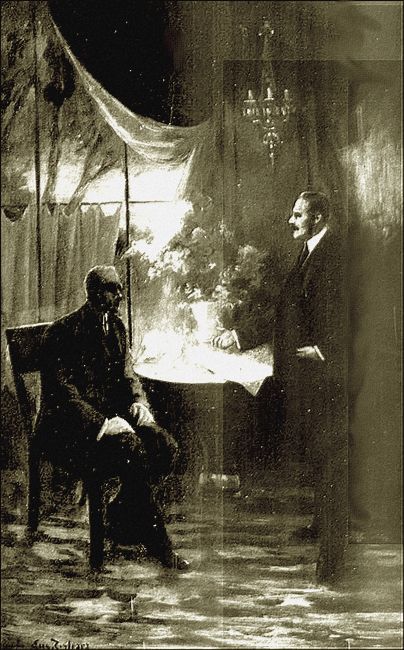

The Professor's fine lips twisted in a compassionate smile.

"It was not a police official," he murmured, "but the head of

the Neapolitan Camorra. An expert might fail to tell them apart."

The Camorra, as every one knows, is a secret association of criminals of all classes, distributed throughout Southern Italy—a government within the Government—wielding political power, arresting justice, extorting blackmail, and enforcing its mandates in the fine and subtle manner of the quattro cento.

Vaini, watching me attentively as he balanced the big pencil on his forefinger, read my thoughts and softly added, "It is a Tammany Tiger, gone slightly mad, and armed with an Italian stiletto."

"What," I asked, "has the Camorra to do with the recovery of the Holy Grail?"

"The Camorra suspects the police of having stolen it, and of trying to cheat the Camorra out of its share."

"You told me the other day you conjectured the whereabouts of the chalice. Have you found it?"

"Unfortunately the police are also on its track. The man who stole it—merely for the kudos of the thing—was nearly stabbed last night, and is in extreme peril this morning. You cannot expect the police to stand by and see themselves defrauded."

"Perhaps," I said, "you know who has committed this theft?"

"Oddly enough," replied Vaini, "it is your fellow-student of thirty years ago—Orion Marblehead. Which may somewhat explain why, as my time to-day is engrossed in playing police against Camorra, I ask you to go immediately to his relief, and aid his escape from Naples."

"At the risk of my life!" I impatiently ejaculated. "Mr. Marblehead should know enough to cast a sop to Cerberus."

"That," gravely replied the Professor, "might be compounding a felony, a thing neither Camorra nor police would condescend to. Friend of my soul!" he added in caressing Italian, laying his hand upon mine, "your hesitation mortifies me. Through all these years have I been mistaken in my favourite pupil?"

I yielded weakly to this appeal, and received instructions as to the precise locality where Mr. Marblehead would show himself, at the corner of an alley called Guantai Nuovi, facing the Church of San Giacomo. I imposed a single condition. "Vaini," I said, "I, as well as the Camorra, have a conscience, and not for an instant will I be custodian of stolen property."

On reaching the Piazza del Municipio, and pausing at the squalid street indicated, I observed that a funeral Mass had just been celebrated in the church before me, and that the cortege, a few bystanders, and the Frati della Misericordia, clad in the long gowns of their order, were dispersing. One of the latter, his head covered by the usual black hood which concealed all but the eyes, brushed past me, and as he did so, I was stupefied to hear him softly whistling an American melody, "Let us drink to the girls that are waiting." I gazed after him in amazement, then, in response to a slight salutation of his hand, followed into the deserted byway. He turned as soon as we were alone, and with the familiar nasal accent of New England exclaimed: "Say, did you ever smell such a rotten peach as Naples?"

Then with great dexterity he drew off his sombre habiliment, casting it with a muttered imprecation into an open doorway, and revealing as he did so the features of my fellow-student of thirty-five years before. His face had become seamed with fine lines of Hustlerium tremens Americanus since we parted in the spring of 1870, but it was the same alert countenance of clear-cut resolve, and his crisp, incisive vernacular was still the vibrant voice of Massachusetts. As he uncovered his head, I noticed that he had become completely bald.

"I saw you come sauntering along," he said, shaking me warmly by the hand, "and knew you right away. Says I, 'That's dear old tenderfoot, and ain't he dressed nice, browned up some, too!' Let's go to a hash-house and snatch a lunch," he added, drawing on a cap. "I am most starved, and want a square lay-out. The drinks are on you," he added with a smile and a wink—"I'm a stranger."

I led the way to Pilsener's Restaurant round the corner, and learning that a turkey was being roasted in the kitchen, ordered it taken upstairs to a private room, together with the obbligato accompaniment of chippolata sausage, giblet sauce, stewed celery, and purée de pommes.

Mr. Marblehead observed these preliminaries with satisfaction, wiping two or three shining beads from his bald pate, and pouring forth his phrases with packed richness of expression. "Let me readjust the focus of events," he began; "this waiter has no more sense than a coroner's jury. I had a small shoat for Christmas dinner, and it seems like I've not had a bust-out since then. Why not? Because I had a brace on such a job as doesn't come once in a century. Say, these Neapolitans have no more shame than a backyard cat. Yes, sir, it is a big job, and I want you to help me right now. I want you to get on to it P.D.Q—pretty... damn... quick."

"Mr. Marblehead," I said as the turkey was placed before us, "I hope that you have found happiness in all these years since we were students together."

"Happiness!" he echoed, helping himself abundantly; "some men would say a cool drink, a thirty-cent Partaga, and the American Sunday papers. I had all that, and it was not enough."

"Not enough!" I ejaculated.

"It's thirty-two years," pursued my companion reflectively, "since I met with an accident. I got engaged to be married. She was an elegant lady, clean as a hound's teeth, and not a fly on her. She had all the hall-marks of youth and beauty, right down to the ground. Her poppa was in the book trade in Amen Corner, and I met them crossing from Liverpool to New York, where the old man had business. She had a small dog, the peskiest-tempered animal you ever saw—I called him Bitters because he had so much bark and whine. Now I generally hit a winning stride, but love-making has never been my strongest hold. I looked over all four sides of her, and brought my proposal down to business. 'Will you have me?' I said—'satisfaction guaranteed, or the money returned.' When I told her poppa I was willing to take his daughter off his hands, he just looked me over in that dignified English way, enough to freeze the stuffing in a lightning rod. He was the sort of man that makes a point of solid silver handles to his coffin. I was worth half a million dollars in those days, and her poppa and I jollied her into saying yes. It jarred me some when she broke the engagement, telling me something I savvied down to mean I was not the only pebble on the beach. I reckon I saw red just then!" And remembering his wrongs Mr. Marblehead lapsed into profanity, wherein he breathed a defiance as sweeping as that which rings through the Athanasian Creed.

"I am sorry to hear you had so serious a misadventure," I answered sympathetically; "but you are not one to remain long discouraged. You soon turned to other and larger fields of action."

"Action!" he repeated angrily. "Yes, and a criminal action at that. I am in for the fight of my life, and I always fight to a finish. Say, if you value nerve thrills, spend to-night dodging about with me; you really can't afford to be out of it, and, say, bring a five-shooter with you: the way to parry is to fire first." With which words he produced a small package, and removing a strip of chamois skin revealed a green chalice, apparently cut from a monster emerald, three inches in height and the same in diameter.

"Look at her," he exclaimed, exultingly smiting the table; "she's worth a king's ransom, even when kings were rated high. With the money Bond Street would give for that, I could settle in England, buy out some belted and busted earl, and look up my fiancee of years ago. It's the weakness of my character that I still care for the woman—the fact is, sir, she's fifty per cent, grit and the rest pure gold."

"This is the Holy Grail," I ejaculated, "stolen some days ago from the Cathedral. Mr. Marblehead, I am shocked to find it in your possession."

"Do you think," he answered with a chuckle, "that a man has no ambition! Years ago I had enough of sending shuttles back and forth and calling it strenuous life. I resolved to do something great. A voice whispered, 'The man that gets away with the Holy Grail is decorated. All the world from Launcelot and Guinevere to our own day will pay to hear him lecture how he lifted it.'" So saying, Mr. Marblehead bit off a piece of plug tobacco, and spat with faultless accuracy into the eyes of a cat that stood sniffing like Lazarus at the gate.

"Guinevere!" I murmured thoughtfully, taking the emerald in my hand.

"Yessir," continued my companion reflectively, "from Joseph with his corner in wheat when Egypt was starving, right down to modern times, we all want to be something more than a fumble-bug. The police were on my trail yesterday, the Camorra tried to stiletto me last night. I put on that fire-escape suit and kept just about five laps ahead—now you have got to get me out of Naples, for there is big money in this."

So impressed was I with our mutual insecurity, that without waiting to conduct Mr. Marblehead to Vaini, I hurried him to Sorrento, and lodged him at the hotel adjoining our villa. I made no further allusion to Miss Godfree than to say that our former tutor had entrusted an elderly nun to my care, whose health required solitude.

IT was evening when I reached the villa and learned that Miss Godfree had retired to her room. The next day she came downstairs to luncheon daintily dressed in China-blue bodice and skirt, with peach-blow undersleeves. Her feather-soft hand rested in mine as she overwhelmed me with extravagant thanks for something she vaguely referred to as "a palsied heart awakened."

I am always embarrassed by thanks, so I hastily led her to Vaini's library, where a frugal refreshment was served—fried haddock with cucumber salad, quails in a bed of pommes pailles, truffles en serviette and a pineapple cheese following in quick succession. I gave her the philosopher's Bohemian wine-glass filled with '48 Amaranth Madeira, a dozen of which rested in his cellar. The room, quite unchanged to this day, is a type of refined comfort. It has book-cases, deep easy-chairs, and writing-tables, and rare and beautiful objects of Vaini's collecting; for though a man of limited means, he possessed exquisite taste for the embellishments of life. He laughingly avowed his hatred for the squalid aspects of the world. About us were rich embroideries, Toledo blades, pictures suggesting the perfection of feminine contours, Venetian mirrors, illuminated missals, Delft porcelains, crystals, and ivory Madonnas. The February sun, with fervent imagination, kindled crimson arabesques upon the damask hangings, and looking from the windows the trees in their tremulous winter foliage seemed lightly clad as nymphs whose limbs thrill with the fever of approaching spring. I thought Miss Godfree graceful as hyacinths in the wind, changing and wilful—beautiful as a summer sky. She had a flattering way of cleverly amplifying what I said, tossing my homespun thought back in embroidered silk. Her face had a delightful air of meditative self-reliance through which gleamed an aerial joy in her recovered youth.

She took my note-book from the library table, and opening it at random, read aloud the silly, scribbled words—

"Un baiser c'est peu de chose,

Pas plus que feuille de rose,

Ou qu'une feuille de laurier."

Then turning upon me those laughing brown eyes, she abruptly closed the volume, and I felt as foolish as the proverbial boy at a girls' party.

"Come with me to the garden," she presently exclaimed, as cigarettes were placed before us, "and we will gather a posy of violets." So saying, she left me in search of a hat and jacket, while I waited in the hall, where on the table lay this characteristic letter from Orion:

Dear Sir,

It is always pleasant to renew an early friendship, and you acted white yesterday. I should like to return the compliment by cordially inviting you to join the Suicide Club of which I am President. Headquarters, Chicago; business hours 10 to 4. Over six hundred members scattered throughout U.S.A., including many rising men and women of America. He who conquers fear of death, conquers by the same magnificent stroke all the fears of life. A time will come when you will have had enough—perhaps too much—of this dear old lark-singing earth. I would like to have you join right now.

Yours truly,

Orion Marblehead.

I was too familiar with my former colleague's originality to

be surprised at this odd missive. Of the Suicide Club I knew that

it had been founded during the feverish years that followed the

American Civil War, that it includes a scattering of army men, a

heavy percentage of doctors, a number of penniless artists, a

large contingent of castaway lovers, a modicum of erratic

parsons. One-fifth are women, and usually all who join have some

profound disgust of life, whose poor game has ceased to be worth

the candle.

In the enchantment of Miss Godfree's presence, the narrow cloister walks expanded to vistas of translucent beauty. The daylight mellowed through that suave afternoon, lighting afresh the purple and yellow bloom of the long-gone summer. The palm-trees lifted their feathery tops, motionless and breathless as ships becalmed. A fragrance of mignonette touched the air, and from the brooding lustre of the myrtles came a rich piping of the blackbird. At such a moment, who would not understand the significance which lovers feel in presence of the mating song of birds.

I have often sought to recall the wonderful things we talked of, whose half-remembered meaning haunts that hour—as roses pressed in some choice volume keep something of the colour and perfume of their day. I was conscious that from the emerald sward at our feet, embroidered with flickering sunshine, many things long dormant suddenly awoke.

"How strangely these few hours have drawn us together!" I exclaimed, hesitating before the face lifted to mine. "It seems as if for both life might be begun anew, far from the things that we have suffered from and hated."

We seated ourselves at the broad old marble table at which, a century ago, the monks gathered and chatted over their coffee. "Only to think," said Miss Godfree, reading my thought, "that in their godless youth they must have revelled in the amorous fiction of Italian story-tellers, and in their winter-bitten age have recalled the pulse and passion of Italian songs they were to hear no more." And the blackbird twittering in the tree-tops sweetened his song to rapture as she spoke.

But the subject uppermost in my thoughts was my companion's life, and I begged her to tell me something of its story.

She turned wistfully a hesitating instant toward the wild-grape fragrance of the vines about us. "You wish me," she began, "to lead you from this cloister back to the garden of my English home. I had a happy girlhood, and to my father I owe a superior feminine education, as we understand such things in England. It was intended to fit me for the 'Smart Set,' if I married well and made my way. He required me to read understanding a leader in the Times each morning. I knew the last dozen Derby and Goodwood winners. I was taught a smattering of French, and made to cultivate a taste in flowers, music, and cuisine, though I cared little for either. I had a Cowes Week during each of my three seasons. I rode straight to hounds, could volley a tennis-ball, and find a train in Bradshaw."

The brown eyes, that in the sunshine had a flash of golden nuggets, sought mine with kindling interest.

"After so comprehensive and practical a training," I observed sympathetically, "I am not surprised to find you in the Church of Rome. It is the only Church Militant remaining, and though myself a heretic, I doubt not that the removal of the Vatican would mean the collapse of Christianity."

"You call yourself a heretic!" observed Miss Godfree with a shocked expression.

"A disciple of Epicurus," I explained, "loving all that is beautiful in life. I have known Christians who scarcely came up to that moderate standard. But we are straying into theology. Forgive me for leading you back to yourself."

"Fate willed it," she resumed, "that in Rome in 1865, when I was a girl of eighteen, I should meet Professor Vaini, who must then have been twice my age. In the library we have just left is the lute he gave me. Can you fancy him singing love-songs, reciting Leopardi's Gonsalvo and teaching me the poetry of gardens?

"From the first I was afraid of him—he was such a strange and secret man, and always in our studies I was conscious that beyond my horizon he beheld unaccountable things. My refusal brought him the morbid bitterness of wounded pride. From love he passed to cold, vindictive anger, and though thirty-five years have passed, he would willingly do me a mischief to-day.

"It was half a dozen years later that I met a man much younger than Vaini, who by an odd coincidence had also been his pupil. We crossed the Atlantic together, and met again in New York. He was a rich American; my father urged me to accept him, and we became engaged. His was a curious nature, the very reverse of Vaini's, and so dominated by material egotism as to strip all life of its amenities and make of it a soulless hulk. He said we should live in New York, and to this day, remembering the words, I behold again the hideous background of Fifth Avenue."

"Would it be indiscreet," I asked, "to hazard a guess at your suitor's name?"

"His name," answered Guinevere carelessly, "is Orion Marblehead."

She sat silent now, tracing a pattern on the brown-needled turf beneath Vaini's pines. Far down the pergola, a sheen of dancing sunlight beckoned me on.

"Will you think me rude," I whispered, audaciously taking her hand, "if I say I dreamt of you last night? It was a splendid dream—a mirage wherein we walked together in this small garden, suddenly transfigured. And as now I took your hand and cried aloud..."

"You said," interrupted Guinevere, "'Let us conquer fate and be happy!' I shared that wild dream with you and felt your touch, and at the sound of your voice I awoke."

"And now," I exclaimed, drawing her to me...

At this critical instant I was disagreeably surprised to hear a drawling nasal voice which came from the top of the cloister wall above us utter the startling phrase:

"I have got him sewed up, you bet."

It was Mr. Marblehead, who, having climbed one of the ladders used in Sorrento gardens to trim the vines, was contemplating me, his face wreathed in smiles.

Miss Godfree sprang to her feet at the words and fled away down the path.

"Say," continued Orion confidentially, drawing a handful of peanuts from his pocket, "don't you ever trust a man with hog teeth. It's your friend the Camorra man, and I beat him hands down. It was an even dollar which jumped first. He blazed up like a bonfire when I catched him—there's no water in the well, only a mud bottom, so he fell soft. He's just about tuned to concert pitch! Listen! sounds like he was twisting knots in the devil's tail."

I remembered in the adjoining garden a disused well, a dozen feet deep, into which Orion had evidently cast his pursuer. And issuing from the earth, I faintly heard the rich and fervent fluency of Italian malediction. The unlucky Neapolitan seemed to be swearing a dozen oaths at once, reminding me of an instrument whose keys are smitten all together.

"Mr. Marblehead!" I cried excitedly, "you are placing yourself dangerously within the law. You have committed a monstrous theft, angered the entire ecclesiastical world, and assaulted an important official."

"I see you have a lady friend," observed my former fellow-pupil, coolly disregarding my words, and fastening his gaze upon the disappearing form of Miss Godfree. "I overheard you love-making just now, and—say—your love-making is loose in the handle. I dare say you think that as a velvet-edged spell-binder you hold the world's long-distance record. I allow you know how to prospect a likely spot, and if this is your own ranche, you are nicely fixed. But when you are trying to come it over a woman, you have got to talk your durndest. You want to put some ginger into it and buck up at both ends. Why don't you be a husky-tough like me and have some style? A woman likes a man that can do a quick turn. I tell you, sir," he added in a modest undertone, "when I make love, I generally lay out to beat the band. I let her have it first in the face." Then suddenly changing to another thought, he continued: "Those low-down Italians have swindled me... the Holy Grail is only bottle-glass. I am going to Naples to-morrow, and if the Law Courts give me a right enough charge I'll bust their Camorra out by the roots. Before I go, take a word of advice. Your occult philosophy no longer runs smooth on all fours. I think it needs a shave. You have held its nose on the grindstone a wee mite too long. There is a dark beyond through which Vaini's two-for-a-dollar search-lights won't carry. I've entered you for the Suicide Club—it's the chance of your life. It's handier, because you hustle right away from the old man with a scythe, and he don't even have time to look for a strawberry mark on your ear. The world won't be in darkness, even though you blow out your little candle. So long."

THAT evening, as the clock struck eight, Guinevere came down

to dinner, rose-white and smiling. Mr. Marblehead's interruption

had passed unheeded. "Come," I said, leading her to table, "let

us have a well-wined dinner, Irroy brut with the croquettes,

Rudesheimer with the foie gras, and after salt codfish on

toast we will drink scalding hot coffee in Vaini's Crown Derby

cups, with a sip of 1801 Soleil Couchant Cognac for the

finish."

The good cheer warmed our spirits and we talked of many things—less of the past, which we had done with, than of the future, which instinctively we realised to be ours. Before dinner I had freshly tuned the ivory lute Vaini had given her in the days of his ill-starred courtship, and when we returned to the library I placed it in her hands.

She ran her fingers deftly over its strings in fluent allegretto, and at the touch a splendid ecstasy filled the air. Before her on the table a great bunch of violets whispered their fragrant secret.

Something called me—souvenirs, regrets—or was it the unknown that is always to come? To this day I still can hear those fine accords, whose heartbreak wove the violets before her into music. Standing thus, she was superb, her fine head poised upon the figure of a caryatide. She seemed the tinted-winged image of girlhood, with its visions and romance. I remember thinking that her face was like a flower-garden, and that when she smiled the breeze was blowing over the flowers. I watched the crimson kindle on her cheek, in mute token of a heart on fire. Her thoughts seemed far away, and for an instant her eyes glistened. I was troubled at this, because the sight of tears in a handsome woman's eyes is apt to make a man do foolish things. Upon what happy wings those memorable moments flew, as in her glance I read the fascinating mystery of a promise.

Softly she sang. It was a song that flushed me with guilty joy, for I divined that a new world lay waiting where her voice summoned. It was a song to set the wild-flowers dancing, yet beneath its forest murmur I listened to a weird accent of enchantment and despair. The blackbirds that through the twilight had filled the garden with their song were silent now. I wondered if they, too, were listening.

It was a well-known German air, "Die letzte Melodie." When the songs shall all be sung and the birds shall all be dead! As she sang, the sea was murmuring a music of its own, thus seeming to make her the embodiment of minstrelsy. Her voice thrilled with the pleading of violin notes, touched with a vague, voluptuous regret.

Yes, I listened with guilty joy, for across those rich accords I beheld a vision brilliant as the Arabian Nights. I had done wrong in applying Vaini's weapons to my own ends, but wrong-doing is sometimes very sweet. When the song ceased in a lingering sense of tears, I knew that the time had come to speak. "I have been looking into the heart of things," I exclaimed, rising—"looking through the prism of that song. I perceive that you have waited years for me, that I have been slow in coming, but at last I am here."

"And now that you have come," answered the strange girl, looking down at her lute-strings, "what are you going to do?"

"You and I have done with society-made values," I answered; "we will leave Sorrento to-morrow morning."

"What will Vaini say...?"

"After what has happened I dare not wait to know."

"And Mr. Marblehead...?"

"For once in his life, Mr. Marblehead will be left."

"It all seems like the dream we dreamt together," murmured Guinevere, lifting her eyes to mine.

My hands were on her shoulders, and we were standing face to face. "It does," I answered quickly, "and when a dream comes true it is because the gods have spoken. The immortals kindling the sunrise cast no shadow."

FOR me the night that followed was one of wakeful hours and fitful sleep. Again and again I started from sinister presentiments. The chief of Neapolitan police and the genius of the vengeful Camorra lurked in awesome shadows, watching my approach, and shifting their stilettos to a firmer grasp. Vaini pursued me with shrill reproaches, and Mr. Marblehead's satanic cunning baffled my escape.

At last daylight came—the grey daylight of a cold rainy midwinter morning. I rang for coffee, my portmanteau was closed, the carriage was coming. It was my intention to drive with Miss Godfree along the Castellammare Road, ostensibly with that town as our destination, then turning to the right at St. Agnello, reach Amalfi, and thence the railway at La Cava. I doubted not that this elliptical flight would disconcert pursuit until we were beyond the Alps.

At the appointed hour of nine, Guinevere was ready, and we waited a feverish instant in the library. The sound of heavy carriage wheels on the gravel followed, and to my stupor an old-fashioned travelling vettura halted at the door, and a figure wrapped in voluminous overcoat and muffler alighted.

The front door was opened, and at the sound of Vaini's voice, bidding Pasquale let me know of his arrival, Guinevere and I were as revellers whose laughter dies at the cock-crow. Nothing save heroic measures could now avail, and motioning her to remain out of view, I went to meet Vaini. "Professor," I said, detaining him in the hall, "a deplorable accident has happened. A careless hand (ask me not whose) has given the nun some drops from one of the casquet vials."

"And she is dead!" ejaculated my tutor in a quivering voice, turning upon me a face of frightened horror.

"On the contrary, the Urohaematoporphyria Cytherae has restored her youth. She is a beautiful girl of twenty—shy as girls will be, and morbidly reluctant to be seen."

"Per le trippe del diavolo," he cried furiously, "by the devil's intestines, who has done this?"

"Vaini," I answered, laying my hand soothingly upon his arm, "I cannot tell a lie ... it was Orion Marblehead. More than this, he has planned to elope with her. I gather that in bygone years there was some tenderness between them."

"Friend of my soul," ejaculated the master, listening with a menacing pucker of the eyebrows, "you stab me to the heart."

"I have already provided for the confusion of their project," I added with determination. "Leave all to me. You will remain here and give Orion the dressing-down he deserves, while I take the girl hence, and place her beyond his reach."

The Professor's lips twitched with jealous rage, and there was in his voice a vitriolic note. His keen face, cruel with disappointed love, seemed imprint with the antique Roman type and fired with its elements of intellect, refinement, and savagery.

"Cattivo Pazzo!" he muttered under his breath. "Orion shall dance with the devil in hell."

At the words the front door was again opened by Pasquale, and Mr. Marble-head appeared, smiling unperturbed.

"You want to size things up and start in on a new deal," he said to Vaini. "The Holy Grail is yours—here it is, bottle-glass, and worth ten francs. But the lady is mine, and I have come for the goods."

The Professor had caught a glimpse of Miss Godfree and waited to hear no more. Springing past me with swift venom, he entered the library, and carefully selecting a vial from the casquet, emptied its contents into his hand and dashed them in a sparkling spray over Guinevere. Above his strident voice rang the sound of her mortal outcry. Her anguished eyes met mine, and there was a pathetic motion of her hands towards me as she shuddered and paled. In an instant her bright face changed to transparent whiteness—the face of a fairy grown suddenly old. The red-gold in her veins faded to silver, and clad in the dusky habiliments of St Ursula, she stood before us, blighted and silent—an aged woman. It was so horrible a thing, that the room swam before me. In their glance of mutual aversion I read the sequel of Vaini's ill-fated courtship, and realised, as never before, that there is no force so vindictive as disappointed love. Vaini had smitten her as with lightning, inflicting a mischief greater than death.

The red-gold in her veins faded to silver, and clad in the

dusky

habiliments of St Ursula, she stood before us, blighted and silent—an

aged woman. It was so horrible a thing, that the room swam before me.

Mr. Marblehead alone remained unmoved, looking on with the intent silence of the busy mind. His plain face grew radiant as though beyond the pitiful understanding of life he had discerned something sublime. "There must be a fibre of the Massachusetts forest in my backbone," he remarked with a hard lip, "or I could not have seen this and live. Professor, you have made her look like a five-year-old picture-hat, and now she will come with me, where she belongs. I guess we may all drop a trap-door on our emotions. Guinevere," he said, turning gravely to the nun, "this is a straight call, and you know I will always treat you white. To-morrow, thirty-four years ago, was to have been our wedding-day. Come with me. We are ready to start right now. Your portmanteau is here, and my only baggage is a snack-basket and a campstool."

Miss Godfree, once more become Sister Eunice, followed her faithful suitor without a word, and together they entered the professor's hired vettura and drove away, I knew not whither. Their departure brought a manifest relief to Vaini, who stood watching their going, with the Holy Grail in his hands. This object he lost no time in restoring to the ecclesiastical authorities, and received fulsome encomiums in the Italian press for its clever recovery.

At my urgent solicitation he removed the Casquet of Essentials from the library table. I represented to him the grievous consequences that might follow its use by a second careless hand if left thus within reach. I was too modest to mention my share in Miss Godfree's adventure, and I doubt not he died in the belief that it had been due to Orion's dangerous meddling. There are occasions when it is wise to hide one's light under a bushel. Months after the Professor's death, I found the casquet in the hiding-place where he had locked it away—the two vials he and I had employed for Miss Godfree still empty.

That evening my former tutor discoursed very earnestly upon what he termed the nun's "semblance" of rejuvenation. He pronounced it a curious hallucination and likened it to a rainbow floating over a cascade, the water alone being real and unchanged, however coloured with evanescent tints.

Mr. Marblehead's clumsy trifling had, he declared, merely rekindled that ephemeral spark of youth which sometimes lingers in the aged, but the figure before us was Eunice, not Guinevere, despite a transitory disguise. His comments upon my credulity in supposing it to have been otherwise were unusually caustic.

Vaini and I had been left alone but a few days, when the following notice appeared in a Neapolitan paper:

FOUND DROWNED AT CAPRI

The bodies of a man and woman that were washed ashore on the landing beach last Thursday have been identified as those of Signor Marblehead Orion, an American millionaire, and of the English Signorina Godam Free. It is supposed that they threw themselves from the steamer Faustine while at anchor during the preceding night. The woman, who, strange to say, was an elderly person disguised in the garb of an Ursuline nun, was clasped in the man's embrace, the singular pair having perhaps eloped together.

SO passed away my fellow-student, for whose scheme of life

Vaini's intangible philosophy had proved an inadequate

foundation.

His mind had aspired to the quest of a superlative treasure such as, in one semblance or another, is the aim of many. He had possessed it for a day, only to realise that the rarest ideals become commonplace at our earthly touch.

In his maturity he had known the unique experience of beholding again, still in the freshness of girlhood, the woman he had wooed in youth—to see her snatched in an instant to an infirm and graceless age.

What wonder if, in the grief of two such disillusions, a disciple of the Suicide Club turned to the tranquil and undying sea!

I AM sometimes asked, now that Vaini is no more and his fame is climbing, what manner of man he was, and what were the methods that led to such supernatural craft. It is in answer to these queries that I have written this and previous narratives, showing, as far as the pupil may illustrate the master's complex mind, those principles of occult force which he found within the grasp of modern science. By thinkers of his own calibre Vaini is considered to have led the way in the unravelling of threads which, after ages of baffled study, are now perceived to connect us with the Unseen World.

I often meditate upon those hours wherein the master taught me to weigh the unreality of things. Sitting in his study this Christmas, with the objects that he loved about me, I seem to see beyond my blazing fire the sunbeams of those meteoric days. Beside me on his table is the Casquet of Essentials, with whose contents I have never again ventured to experiment. Yonder is his set of amber chessmen, marked with the arms of le Grand Monarque, and on the wall hangs Guinevere's ivory lute.

Here, in Vaini's garden, the roses the Jesuits planted half a century ago still lift themselves upon the cloister buttress with a shy caress. They are of a stock of extraordinary antiquity, popularly descended from roses that flourished at Capri and Ischia before Parthenope and Paestum were known—in days when Poseidon was young and made love to the beautiful daughters of men. Years ago, at first sight of them I bethought me that in ploughing old fields we may turn up the seeds of celestial flowers. Nameless, I have named these roses Toujours ou Jamais in remembrance of that which Guinevere and I agreed should be Forever—and which scarce outlived the brilliance of a day. Above the monks' pergola a yellow trumpet creeper waves its flaming tendrils in profane exuberance, as though after mediaeval centuries this tiny span of earth has not yet lost the glamour of its Golden Age. Bend as they may, its paths all lead to aspects of living beauty, and however short, they are more suggestive than many a lifetime. Their witchery holds a meaning beyond the significance of the actual world. The tranquillity and vividness of monastic association linger about these walls as a ghost story clings to a haunted house. In this Villa Sirena, whose very name is music, I seem to hear again that sweet-sung cantilena—as it were a fugitive chord, linking some rapturous memory with the poesy of nature. Deep in the night's heart phantom footsteps come and go.

The tranquillity and vividness of monastic association linger

about these walls as a ghost story clings to a haunted house.

On pleasant spring mornings I seek my garden at dawn—at the hour of perfumed darkness when in ancient days the nymphs awakened. The early sunshine, climbing these mountain sides with golden shoon, unfolds its opalescent mirror. An instant follows, splendid with awakening life, and brief as the echo of footsteps down the Eternal Silence. And often, thinking of the feet whose tread has smoothed these cloister walks, I remember the wan, grey figure of Eunice, telling her beads, and fancy behind her, leaning at the monastery well, a radiant and imperishable vision of Guinevere.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.