RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

TO read a page in a man's love-making is to look into his heart. It is a glimpse we rarely possess, yet through it, alone, can we measure the perspective of his life. In default of those amenities of fancy and colour and music which one who records a love story should possess, I bring to this narrative an intimate remembrance of those who chiefly moved in it, and who have all passed away.

I arrived in Rome shortly before Christmas, 1882. Seven years had elapsed since my last meeting with Professor Vaini, during which interval we had corresponded regularly, and I had often looked forward to a renewal of our experiments in a domain beyond human knowledge.

I had long listened enviously to the gentle call of Italy. The Rome I was to see was greatly changed from the days of my studies a dozen years previously. There were still chimes and ringings and processions, and on the air a muttering of mass. In places its streets were modernised, but the Madonna and seraphs and allegories of love and damnation remained. To whoever cherishes the intellectual pictures of antiquity, the heart of Roma Amor opened its secrets of imperishable fascination. But the argonautic note of investigation had its reverberation even here. There was a lurking flavour of democracy that sacred incense could not extinguish, and I remember thinking that only the gleam of immemorial sunsets remained wholly the same.

The gentle call of Italy

In his latest dispatches my former tutor had vaguely alluded to a discovery of exceptional interest, to which he had applied his wide knowledge of the forces of life. He said he should require one of the "Chosen Few" to collaborate in the technique of his research, and inviting me to this service, wrote:

In great problems I have taught you to be simple and direct. Therein lie the elements of pure force, and there, alone, can we find that concentration which is the essence of success. To me, existence is a thread lit and unlit by the sun. For once, good fortune has met me half-way. The time is ripe, come quickly, and we will beat the gods at their own game.

THE Professor was lodged on a slope of the Aventine in a

humble building at the side of the Church of Santa Prisca. It was

designated "the gardener's house," and its front presented a

dingy entrance and some heavily barred casements. Once within,

there were two excellent suites, one on the ground floor occupied

by Vaini, and in that above, amid such comfort as rarely falls to

a gardener, lived the curator of the church, his wife, their

child, and two maids.

The Maestro's room was a cube of brightness in that solemn house. His windows overlooked a garden of stone paths, with odorous box-edging and myrtle and willows, and buttresses draped with flowering vines. It looked formal as that severe garden of the Escorial wherein Spanish kings and queens pursued their tortuous and sinister thought-drift.

On the morning of my first visit to this habitation I addressed a word of inquiry to a little girl who stood in the alley watching me with bright brown eyes. At Vaini's name she smiled and offered to lead me to the door. Could I have divined what curious shapes were to gather about that child, I should have observed her with more attention. As we walked I asked: "E tu chi sei—figlia del padrone?" A child so carelessly dressed could scarce have been the daughter of any padrone, and she laughed at the question.

"Figlia del giardiniere," she answered, continuing her plucking to pieces of a flower in the feminine pastime, "He loves me he loves me not". Her answer was to come back to me later with significance.

At the door of the house toward which she led, a handsome woman leaned, carelessly interested in my approach. There was a look of calm watchfulness in her deep-down hazel eyes which, as the days passed, I perceived they rarely lost. She wore a little golden comb, and in her attire was that mixture of colours wherein Italians delight. Her waving hair lay low on a broad forehead. She was still in the prime of womanhood, aged perhaps thirty, with the familiar Roman features of slumbering ardour. A tame tigress, I thought, glancing at the sinuous figure and the handsome, masterful face—a face that suggested some faint, far, meditative vision of "Arabian Nights." On hearing the Professor's name, her unconcerned look changed to one of pantherine grace as with caressing voice she invited me to the garden.

On my way to the loggia, where Vaini sat near a spread luncheon table, we passed the child's father, the curator-gardener, by name, Francesco Ottomana, on whom, by reason of a physical characteristic, my former tutor had bestowed the appellation Bocca di Porco (pig's snout). He looked twenty-five years older than his wife, and his appearance, as he leaned on a rake, eyeing me with a puzzled-monkey air, and wearing a round, yellow sun-bonnet, adorned with feathers, doubtless one of Madame Ottomana's discarded furbelows, was extremely comical.

The Professor rose from his amber chessmen to meet me. "It is the knight's move," he exclaimed with a kindling smile, "that resembles the irony of Fate. It is subtle as the elusive fourth dimension in mathematics. Nothing can interpose, and its stiletto stab passes our guard with the stroke of King Arthur's supernatural blade."

From our cheery greetings I glanced about at clipped cypress walks, the crumbling walls and arches of the Palatine abode of the Caesars, tinted in the thin, pensive December sunshine with imperishable bloom, to the roof of Ottomana's house, where, amid a fringe of teazel bristles, a single gargoyle looked down with stony leer. There was a soft susurra overhead of silver olives, and something in the air thrilled with the faint heart-beat of the dying year.

"Maestro," I said, "if I am here in response to your gracious summons, it is because I know that your measure of success is drawn at the border line of things impossible. What marvel of ancient days is to be recovered is the theme of my incessant musing. After our tragical misadventure at Bath, seven years ago, with your Celestial Virgin, I fervently trust our business involves for me no more make-believe love-making."

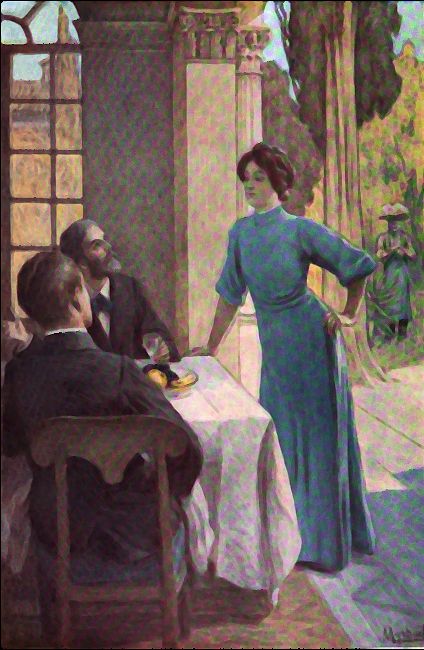

"Carissimo," answered the philosopher, pausing to observe the flattened curve of a swallow's flight, "the sea buries the miracle of its shells in unknown sands. But here comes the rizotto. 'Let us fall to,' as Isaac Walton says," he added, helping me to a goblet of Montepulciano. Our frugal lunch was served in the loggia, which answered the double purpose of study and dining room. A maid brought the plates and dishes, and the gardener's wife came to assure herself that all was to our liking.

Our frugal lunch was served in the loggia, which answered the double

purpose of study and dining room. A maid brought the plates and dishes,

and the gardener's wife came to assure herself that all was to our liking.

I became not a little interested in that gardener's wife, whom, as the days passed, Vaini sometimes addressed as Signora Ottomana, occasionally as Eufrasia, and, in rare moments, by the caressing name of Fior di persico (Peach blossom). I admired the musical contralto of her voice, the lithe poise of her body, the satin-smooth coils of her hair, and her white, muscular hands as she drew off her gardening gloves. Her outline showed beneath the blue gown, and I remembered the swelling contours of Aphrodite of Melos. Something about the signora suggested that hidden "glory" which St. Paul has omitted.

"Is she not a beauty?" whispered the Maestro... bellissima... volupta!

"She looks," I assented as she came and went, "like some sandalled muse grown modern. I envy the gardener," I added, whereat she regarded me with a sidewise, flashing glance.

"I have come," I said, addressing her with gentle ceremony, "to taste the Roman gnochi my host praises when your hand prepares them." Her face flushed a little, and turning to me, she smiled a radiant answer.

"They shall not keep you waiting," she replied, as a maid came bearing the Professor's chafing dish.

"This seems a hushed and listening spot," I said, glancing across the garden. "I feel disposed to come here and share the Professor's studies!"

"My husband shall show you what our poet calls the secret flowers," she answered.

"I would rather see them with you," I ventured.

There sometimes comes in life a day which, ere it lapses, leaves an indelible mark. In observing the master's volupta fior di persico I knew that some such day had come to me.

When we were alone, Vaini explained the scope of our research. "You remember," he began, "that when in the reign of Theodosius, pagan temples were closed in Rome and their marble divinities concealed, the Christians made great search for that Diana whose greatness the Ephesians had shouted to St. Paul. When her renowned temple was pillaged and burnt, its sanctuary was empty. Whatever the object was that typified her spiritual being, the Christians attached extraordinary importance to its destruction, and I doubt not that to escape them it had been removed to Rome as the only refuge.

"It is obvious that this fetish was more than an idol. The Greek mind in Paul's time had ceased to care for images, but here were supernatural attributes still exciting veneration. You, my favourite pupil in mystical craft, will readily guess what this object was?"

"Indeed, Professor," I replied, slightly disconcerted, "my mind is a blank on the subject."

"Must I recall to you the Black Stone of Mecca, a meteorite, and of its veneration for a thousand years by the Mahommedan world?"

"Do you mean," I exclaimed, greatly astonished, "that Diana of the Ephesians was a meteoric stone?

"In outward form, yes," replied Vaini, amused at my surprise, "and brought, as I believe, to Rome and placed in the Sanctuary of Diana Aventina. Now the reason I am lodged where you find me is that the Church of Santa Prisca is built above that sanctuary, amid whose buried ruins I have been digging an hour or two daily these past live years.

"Let me add that I have often seen this meteorite, which is four inches long by two in width, largely composed of iron and covered with a shiny crust. Upon its surface are streaks showing the flow of its parts when plastic. When my hammer sounded on a hollow chamber I knew the long-lost Diana was found. On entering that crypt I saw, by the light of my lamp, a mutilated female statue. Originally half-nude, it had been covered with heavy terracotta drapery. In its outstretched arms had been placed a clay image of an infant, thus converting the pagan huntress to the Christian Mother and child. On finding that the image is composed of marble dust stucco I doubted not the meteorite had been buried in its bosom. As iconoclastic danger increased the change of subject was hastily attempted, and, finally, the figure was torn, in some hour of desperation, from its position, cast into an underground recess and walled up.

"So now," concluded the Master drawing a long breath, "let us light a pair of lamps and descend to the crypt." He stepped to a work-table, on the grass, where stood several lamps and candles. In following him I struck my foot against a fragment of broken tile, beneath which lay a scrap of paper, whereon in a feminine hand, were the words in Italian, "This evening at nine," obviously the orthodox Roman method of assignation—from whom to whom?

My former tutor led the way without observing my discovery and, having placed a brilliant light in my hands, commenced the descent of a ladder where we closed and bolted the trap door in the floor of the loggia. Counting my steps I calculated our depth, at the foot of the ladder, to be a dozen yards below the streets of modern Rome.

"We stand upon the virgin soil," observed Vaini, as we followed a passage, the shaping of which had been his labour. Marble fragments, all greatly injured by fire, lay at our feet. We emerged upon a square chamber whose vaulted arch remained intact, and passed through the opening the Professor had made into the holy of holies. In the midst of bits of agate and cornelian pavement lay the life-sized female statue the Maestro had described, a pagan Diana holding in her outstretched arms the stucco fragments of the Virgin's child.

Snatching a ten-pound sledge hammer I dealt the figure half a dozen resounding blows that sent it flying in pieces.

A rapturous instant followed—one of those moments that Fate touches with a diamond—for there, embedded in Diana's bosom, was the meteorite the classic heart of Greece adored.

"Diana of the Ephesians."

It was easily extracted, and breathless with emotion, we returned with it to the world of daylight. As we emerged from the trap-door into the loggia I saw a stranger watching us from a clump of cypress at the end of the garden.

"Who," I whispered, "is that hang-dog that comes to pry upon our doings?"

An expression of unwonted hate flitted across Vaini's face as he muttered the name—"Atteone."

I LEFT my tutor alone with his flinty Diana, and wondered at the coincidence of his having so accurately anticipated its hiding place and predicted its appearance. The next day being Christmas Eve he was to dine with me, and I had promised to call for him in the afternoon.

On nearing Santa Prisca I saw, as on the previous morning, the child, figlia del giardiniere, awaiting me. She held a handkerchief to her face, her blithesome look quite gone, and with eyes fixed upon me made that deft sidewise movement of the body that in the code of Italian gesture-signals means DANGER. Instantly on the alert, I paused and asked: "What is your name, sweetheart?"

"Alcione," she replied, slightly repeating the same ominous movement.

Seeing that her nose was bleeding, I murmured: "You have been hurt; what has happened?"

Her eyes glistened, and I followed with attention the words of this little being who spoke with the decision of maturity. Twisting and untwisting her small handkerchief, and seating herself upon a block of masonry, she swung her slender limbs while whispering in a disconnected phrase: "Beware Atteone, he has struck me with his hand, he will strike you with a knife. Tell the gentle Professor that Atteone hates him."

"And why so much hatred?"

The smile crept back to her eyes. "My mother is yet young," she said with a furtive backward glance, "and so is Atteone. The Professor is not too old to love. He is often alone with my mother, and Atteone thinks that rose upon rock rooteth ill. Go, signor, wait no longer, we must not be seen thus."

Our colloquy had lasted but a minute, and knowing Italian ways, I turned and walked to the Ottomanagate, where a maid admitted me, pointing to the gardener who stood beside the well-head.

"I find you by the well," I said, "a happy omen for me, who at this moment am in quest of the truth which is sometimes at its depth."

"A well," answered Ottomana in a bantering tone, "is the haunt of Love. Beside a well Isaac's messenger met Rebecca. At the Midianite Well Moses found Zipporah. By the well of Haran Jacob beheld Rachel. It is a token of love and perfect knowledge that by a well the Master taught the woman of Samaria. Moreover," he added with a chuckle, "is not an old man's love a bucket in an empty well?"

"You are versed in Scripture," I answered; "but age is not always so cold as your proverb supposes. Was it a trace of your doings I found yonder yesterday beneath a fragment of tile—a scrap of paper bearing the words, 'This evening at nine.' Oh, lover of wells and gardens, what meaning was there?" And at this question Ottomana's lips hardened in a grim smile.

"Tell me," I added quickly, "who is the man Atteone I saw peeping and watching yesterday?"

The smile changed to a snarl as the gardener wove a complicated curse about the name.

"Who and what is he?" I asked.

"Cardinal Blackadder's secretary he was, and he has the heart of a cruel Puncinello!"

"I have reason to think he is here now. Has his presence to do with your wife or with Professor Vaini?"

Before the man could answer, his wife stood noiselessly beside us with heightened colour and quickened breath. How subtly beautiful she looked, and what wonder if the Maestro beheld in her the blossoms of his youth. We stood silent a moment with no sound about us but a twittering flash of swallows overhead. It seemed as though beyond the veiled dusk of that hour, beyond the crimson sunset's trailing plumes, beyond the pathos of autumn with its leaf-blown wake she had come from the heart of vanished things.

"The Professor will not keep you waiting," she said, carelessly rolling a cigarette; "he is talking business, let us rest a moment in the loggia."

We walked away. More and more impressed by the attractiveness of the old gardener's young wife, and greatly mystified by the warning of her little girl, I resolved upon an audacious venture. Remembering my tutor's piquant exposition of the knight's powerful move, it occurred to me to seek some such decisive action on the board where curious forces were gathering.

"Fior di persico," I began, taking her fine hand, "since those who love you know you by that name, in the country where I live there is a peach called golden heart. In poetic fancy, it is a type of things sincere. I ask you to be likewise golden hearted, and tell me why Atteone comes here with sinister motives?"

She drew a step away, then her defiance died unspoken. "Are you not taking advantage," she asked, "of the intimacy in which your friend lives here?"

"I suspect Atteone of some spiteful grudge," I replied. "It is his trespass that is to be explained... must I go to the Prefect of Police?"

She put out her hands in swift, appealing gesture, while I stood watching her bosom rise and fall. "Could I tell you," she ejaculated, "what you ask, without leading you to question me ever further, till from Atteone we came to—"

"To Vaini?" I queried as she hesitated, "and thence to yourself. From allusions in his letters, I know that to you he has revealed that inner self which a man discloses only to the woman he loves."

"You see!" she interrupted, "it is the golden shuttle of your friend's romance you seek."

"I doubt not it is worth seeking," I answered, "and fine as the pastimes of Olympus. I shall ask Vaini."

The master's voice rang across the garden, and it did not surprise me to see Atteone issue forth and walk away, while the Professor shook his fist after him from an open window.

As he and I left Santa Prisca together, I could see that for all his self-restraint he was deeply angered. I guessed the nature of his quarrel, and expressed it in the word Ricatto (blackmail). The Professor nodded in silence. That morning I had felt so concerned at his insecurity that I had visited the chief of Secret Police, and upon payment of a liberal bonus had arranged for his protection.

I had ordered our Christmas dinner with the malicious intention of tempting the Professor from his habitual abstemiousness, and warming him to concert pitch of confidences. A comforting cream soup, a baked spinola, a dish of strangola prete, and, lastly, his favourite mushrooms sauté. Short as a good dinner should be, and moistened with a bottle of my Rainwater Madeira, followed by Lafite of '68 and Veuve Clicquot brut with the dessert.

As we finished, fresh logs were heaped on the fire and scalding hot coffee being served, I offered Vaini my flask of 1801 Cognac, observing in Bismarck's words, "Those who conquer the world drink brandy!"

"So to-day," he said, helping himself to a thimbleful, "you walked to the Gianicolo, and you have stood in the Church of Maria sopra Minerva, the Christian altar raised above the foundations of Pallas Athenae. Eighteen centuries ago, both that and Diana Aventina were banks where plutocrats deposited their treasure beneath the wings of a virgin goddess. How often, gazing upon the remnants of those days, do I listen for the rhythm of ancient Rome, the flutter of its mighty soul!"

"You have often traced for me," I assented, "how one faith springs from the other."

"And with no less confusion now," he added, "than when Constantine's effigies gave him the proud attributes of the sun-god, of Christ, and of Caesar Imperator."

"Do you," I asked, ready to humour my friend in his hallucination, "still exercise that second sight I knew in you years ago?"

"Per bacchissimo!" cried the philosopher testily, "it is sub-conscious, and does not need to be exercised. The glory that once was Rome—what is it but Time's picture, and its dome is horizon wide."

"Nevertheless," I observed, lighting a cigar, "it was all a lurid pandemonium!"

"Yes," agreed Vaini, his eyes fixed as though riveted upon the scene he described, "distraught between hates and pleasures, its body politic consumed, the nights ringing with violence, crazed in a delirium of myths and fables, smiting alike the Christian and the Jew, cruel, debauched, despairing—such was Rome when it read its doom in the spears of the Goths."

"Were the ancients really more wicked than we?"

"Chi sŕ! Paganism revolted at the austerity of Christian marriage. Chastity and asceticism! Oh, master of the clarion and the lute, what were these to men who lived for lust? A woman had her child by the man she loved. Filled as we were with the worship of the body, what had we to say to a gospel that proclaimed, 'There be Eunuchs that have made themselves Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven's sake.'"

"Professor," I observed, "whenever in our studies you have revealed some such sudden shifting of the scene, a suspicion follows that in those heroic days you loved and were happy."

A stray shot occasionally flattens in the centre of the bull's-eye. The quick flow of words ceased, and it was with averted face that he murmured: "It was a god's life, free and lawless!"

I pressed my advantage and asked reproachfully: "Vaini, are you hiding from me that your romance is interwoven with our meteoric stone?"

"You ask me," resumed my former tutor, turning to me with his usual calm, "to lead you among the mystic groves with the most beautiful woman that ever lived beckoning us on. Listen.

"One night before the Temple of Diana Aventina, seventeen centuries ago, swelled songs and the melody of flutes. Whoever listened doubted not that the goddess was shaping the souls of men. The priests chanted that the stone changed to flesh, or, being flesh, returned to stone. A flamen led me aside saying the goddess wished to give a command. We know that the Immortals talked with men and women, yet at that instant I felt face to face with elemental mystery. I was left alone in the half-light of a peristyle, whither a figure advanced with the steps of a splendid untamed animal. In its face were leadership and imperishable youth. Swift-footed, volupta, moving like a breath. From her shoulders hung a drapery now clinging to her hips and bosom, now fluttering loose. Whence came she if not from making the almond trees bloom at her touch?"

A figure advanced with the steps of a splendid untamed animal.

In its face were leadership and imperishable youth. From her shoulders

hung a drapery now clinging to her hips and bosom, now fluttering loose.

"'Come,' she said, 'let us drink the wine of Olympus, which is love:' and she filled a cup. We stood alone, and her cool, soft lips were on mine. She laughed, saying: 'Let us be happy, for who knows if the gods prolong to-morrow their gift of to-day.' Oh, Belamore! Was it a summer's night's illusion or the passion of a lifetime? All smiling, she plucked a rose and gave it me. and we drew together as flame to flame, and she bade me remember that night and the savour of the rose." And Vaini paused, shading his eyes, as though from some blinding memory.

"Carissimo," he added, "do you know what is meant by the skyward flight of bees? There is one queen bee and in the hive a hundred that fain would love her. At the lovetime of the year the queen soars upward, the male bees following, the weaker or less ardent dropping back to earth. Still upward she rises, followed now by only a few. Presently one bee, the strongest, most passionate of all, is close. The rest have fallen away out of sight. The lover is alone with his bride, and there, far from all dross of the material world, he takes his pleasure of her.

"Such," whispered the Professor, "was my love of the Ephesian Diana. It was for ever; for who that has risen to the lips of a goddess would bend to a woman's caress?"

"It looks to me," I replied severely, "as though you have been tampering with a Vestal."

"Let me finish," said the Maestro, with a deprecating gesture. "She sent me to live in a forester's cottage amid the Nemi woods. I never knew in advance of her coming, which was always at the edge of morning between the dark and the dawn. Sometimes she remained but a moment, sometimes she lingered out the day. It was the season when blossoms whiten and birds sing and fountains murmur—when laurel and zephyr, the typical maid and her lover, meet. There would be a call or a whistle, and from under the trees she would come, fawn-like, morning-eyed, the peach blossom on her face. She knew bird-talk, and loved the life of all wild things. She could read the meaning of a falcon's flight and interpret secrets on the face of the rocks. On one such morning she whispered in a thrilling caress: 'Think of the men who have loved me, pursued me, died for me, and—' as she spoke we heard the distant ululation of a wolf. Ere the sound ceased she called her brindle-black hounds and dashed away, and presently I caught a faint triumphant echo of her voice. Another day, in sport, she bade me cast wild apples to the tree-tops, and with her arrows split them as they fell.

"The shadows sleep beneath the vine she loved, and for me, when my eyes grow dim to the sights of earth, I shall still meet Diana and walk with her in the cool of the day." And as he finished a great log crackling in our fire glowed with iridescent tints of green and ruby as though the wild story had touched it with fantastic light.

"Of all your narratives," I interrupted, "this is the first that disappoints me. I hoped you would shiver the hour into sparkling atoms about Eufrasia."

"Cannot you see," retorted the Professor, "that all I have said leads to her?

"At first sight," he resumed, "I could not fail to be struck with Eufrasia's appearance. She walks with the swift, firm step, I remember. She is calm, alert, observant as the other. She has the same Narcissus lips, the same light-hearted laugh. Like Diana, she is wood-wise, and often watches the night into dawn. There were things I half-remembered and she half-forgot. At first she looked at me with wonder, yet I could see some recognition whispered. A woman retains consciousness of a former existence so much more distinctly than a man. Had a golden-footed coincidence led me back to my fior di persico?

"Yes, the old passion leaped into new being. Needless to remind you, I care nothing for women, and in this life never loved before or since. In her garden we walked one evening, while the past beckoned and spoke its ecstasy. The trees Diana loved stood motionless before Eufrasia. She plucked a rose and gave it me with smiling intention, praising its old-world savour. With what emotion I beheld that repetition—the same woman who centuries gone on that same Aventine had given me a rose!"

THE night being fine, Vaini and I walked back to Santa Prisca together. Between Atteone and that dangerous Circe, and her brutish husband and their various vendettas, I felt concerned for his safety. When, as we neared our destination, the air rang with a man's shrieks for help—"Aiuto! aiuto!"—I understood how imminent had been the Professor's danger.

"It's nothing very alarming," I said to my startled companion, as I drew a five-chambered Colt, a weapon which the poniard-armed Italian of those days held in aversion. "Atteone, spying your return, has been surprised and stilettoed by a police official I placed here."

My surmise was correct. The guard, with knife still in hand, met us, and reported that, having observed a man—perhaps Atteone—skulking near Ottomana's door, he had arrested him. A scuffle ensued, when in self-defence he stabbed his prisoner, who, wrenching himself clear, had run off.

"Then he is not seriously wounded," I observed.

"Signor, it was in the left ribs I struck him, in the region of the heart. By the grace of God he will bleed to death in the night."

I dismissed the man, and wished my former tutor felicissima notte. But I did not immediately withdraw, for my eyes were fascinated by the face of the child Alcione peeping from a small window on the ground floor. When we were alone she beckoned me near.

"Did you see what happened?" I whispered.

"Yes, both saw and heard."

"What did you hear?"

"Half an hour ago Signor Atteone was talking with that watchman where you now stand. The watchman, who seems to know you, came suddenly upon him and threatened arrest.

"'How much are you getting for this?' asked the cappellano.

"'One hundred francs if I catch you, two hundred if I give you a coltellata in the ribs.'

"'Excellent!' exclaimed Atteone. 'Here are twenty more. When the Professor approaches you will feign your coltellata. I shall scream... and run. It will not be your fault if I escape.'

"Che commedia!" the child murmured, with a soft laugh.

"One word before I go," I answered in the same low voice. "This former chaplain of Cardinal Blackadder seems very intimate and familiar with your mother. What is he to her?"

"My mother once said she thought Signor Atteone is my father."

"Does he say so, too?"

"He says I am figlia del giardiniere."

"And what says Papa Ottomana?"

"He says I am figlia del Padrone."

"But which Padrone?"

The child drew back with a subdued ripple of mirth and closed the window.

ON returning to my hotel at midnight I dispatched two telegrams, one to the Chief of Secret Police, with whom I was acquainted, and one to Atteone. The following morning the clock was striking ten as a visitor was announced. The ex-chaplain was too shrewd to take the consequences of disregarding my summons, and presented himself with the punctuality of a man of the world. He was a small, red-bearded personage, aged about thirty-five, holding in his sinewy fingers a gilt-bound snuff-box that bore the Blackadder ecclesiastical crest. I perceived no sign of a wound, and he saluted me with that unctuous suavity which to the ecclesiastical cloth corresponds with the bedside manner of a fashionable physician. Once acquired, that oily presence is never lost, and as he moved, unfrocked, one could fancy the rustling of a vanished soutane.

"Signor Atteone," I began, as he seated himself on the edge of a chair and watched me furtively, "you have been menacing the peace of Professor Vaini, and last night were nearly caught in your own snare. I am giving you a brief opportunity to explain, unless you prefer to discuss matters before a magistrate."

"You are enough to make the very stones weep," he ejaculated, with a lift of the brows. "You imagine you have trapped the wolf; it is a lamb you have by the throat."

"Wolf in the fleece of a lamb, or lamb with the fangs of a wolf, as you please. Suppose you begin by telling me the nature of your grudge against my friend."

"I have never harmed a hair of his head, though it would be but truth were I to say that he is possessed by a devil, an intelligent devil, like the wise serpent that in Eden pointed the way to the tree of Knowledge. He hath a collection of odd fancies, like the uncouth idols brought from far lands. This time Satan points him to a hole in the ground where he has spent years a-digging. Is it forbidden me to wonder why?"

"You remind me," I said, "that a week ago, carelessly overturning a stone in the Ottomana garden, I came upon a suspicious scrap of paper covered with Eufrasia's writing. Can it be that you and Professor Vaini were once rival suitors?"

"Why," he asked, feigning a startled reluctance, "reopen a long-closed book? Forgive me," he added, "if I take snuff; it is, in truth, a habit savouring of the lesser sins."

"Reopening your book," I observed, "shows me Cardinal Blackadder's name upon its shining page. Was he the father of Eufrasia's child?"

"Father of that imp that is old in wickedness! But, seriously, I see that you imply that when his Eminence had saved her life she bestowed upon him the return a handsome and grateful woman can make. In all honour, I do not think so. The Cardinal spoke of her as Figlioccia, god-daughter, which he would not have done had the relationship been profane."

"Who, then," I cried impatiently, "is the father of that fatherless child?"

"Who should be its father if not Eufrasia's husband? Sometimes," he added, chuckling, "the truth is like a flea—when you think to hold it the secret jumps."

"It is whispered that you are Eufrasia's lover."

"Signor, in this queer world we do what we can. When I was the Cardinal's secretary he often sent me to her with messages, or cakes, or wine. Those happy days were a gem that has found its perfect setting. Her life had been sad, its spring had been cold as mid-winter, yet all the world knows that it is in the glow of a mid-winter sunset that the hope and music of spring are kindled. Her voice was as fine as the drift-song of rivers. But, knowing I had awakened the dislike of both Ottomana and the Professor, I was on my guard. Moreover, I could not look upon her calm, imperious beauty and watch the allurement of that sweet, provoking smile without thinking of forbidden fruit. You see it was the very essence of that curious honey and gall we call life. And what is life worth if we get nothing from it?"

"I certainly have got very little from you, Signor Cappellano," I remarked, smiling at these last evasions.

"How could you expect much, or anything," he retorted, with comical misapprehension, "my stipend being so small. Rather might one have looked to find it the other way. How graceful would be a benefaction from you to me, and how gratefully received! God loves a liberal as well as cheerful giver."

"And blackmail and stilettos, too, no doubt," I added, amused at the change imparted to our conversation. "One word in earnest to finish with. Suppose you leave Rome."

"Signor," objected my visitor, with an assumption of horror, "this is a cruel menace."

"There is a criminal court five minutes from here, and at Civitŕ Vecchia is a convict prison. Between now and to-morrow noon your patron saint has time to lead you far from both. Farewell."

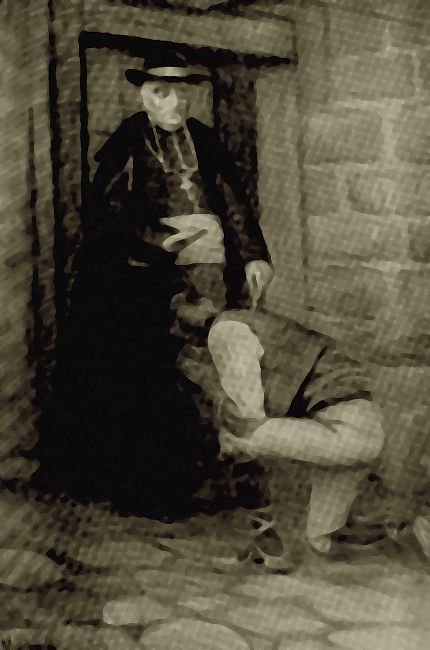

EARLY that morning I had sent a message to my tutor's gardener bidding him come to me at once upon a serious matter. Atteone had been gone a few hours when Bocca di Porco made his appearance.

Bidding him be seated, I offered him a cigar. "Accept something better than those you commonly smoke," I said, "and answer a few questions. Tomorrow Atteone may face a charge of felony, and unless your explanation is to my mind you shall also spend a few nights in the lock-up. Therefore, without further compliments, as the Romans say, what was the motive of the Cappellano's attack last night?"

Ottomana listened with fixed attention, and with the untroubled calm of one habituated to great and sudden danger. "I am bone dry," he began, lighting his cigar, "and with your leave will drink from yonder fiasco. Then I will begin at the beginning, and you shall observe how the truth peeps over the shoulder of a lie. Take my word for it," he added, with a genial smile, "most secret plans have a hole in them." He drained a goblet, and settling himself in an armchair, said:

"Signor, to return to the happy days of my youth, my home was at Olevano, the little town that artists delight to paint, and by trade I was a fortune-hunter. In the late 'fifties ransoms were large when we had the luck to catch a banker, or an eccellenza, or an English milor. But, short of being Columbus, one cannot always make an egg stand on its point, and my fate came in the shape of a grey donkey. On its back rode a woman disguised as a boy, who emptied a blunderbuss among us, killing two of my men, and grazing my neck with a nail. It was a silly vendetta; she had been supplying us with cheese and farina and brandy, and sometimes remained the night in camp. Our quarrel roused the good-natured police." And, with voice lowered to the growl of a wrathful animal, he added: "I was taken to the Castle of St. Angelo.

"Two days later I was startled with the announcement of a visitor, and made to wash myself. You could never guess who came—a cardinal! And I will refer to him by the endearing name his household bestowed—l'aspe nero, the Blackadder. He had beautiful manners, and as he entered I knelt before the benediction of his hand."

He had beautiful manners, and as he entered

I knelt before the benediction of his hand.

"'My son,' he said, observing me curiously, 'would you prefer freedom to these bars? Next Sunday, if you like, you shall be back in Olevano eating umido manzo.'

"'My release is certain,' I answered; 'the carabinieri have been over-bold to meddle with me.'

"'Have a care,' interrupted his Eminence with a warning gesture, 'reading the future savours of heresy, and the reward of a prophet hath often been stripes. Who dare affirm,' he asked with meditative reflection, 'that you may not live only just so long as it takes to dig your grave?'

"'Emminenza!'I stammered, crossing myself.

"'On the other hand,' he pursued, drawing forward a velvet stool an attendant had placed, 'there might be a comfortable home in this city with good wages and no more questions asked.'

"Not understanding, I suppose I must have looked pretty foolish.

"'There would be a wife also,' he added pleasantly, lifting his lusty face and glancing about to see that we were alone. 'She is handsome, buxom—volupta—aged nineteen, and such fine white, even teeth! She will have a velvet marriage gown, two hundred silver scudi for house furnishing, and twenty for a wedding breakfast. Wine in bottles that day, mind you, no common fiaschi.'

"Signor," observed the gardener, interrupting himself, "you should some day ask Eufrasia to tell you her point of view of this story. To listen is better than drinking a cup of chocolate. In some bygone century, when Italians loved to gather under the arcades on rainy evenings and listen to the professional story-teller, some ancestor of hers held his dozens rapt and breathless, watching Bianca Capello's lover stabbed to death in the alley, or tracing the adventures of many a Desdemona."

"To resume, then, you remember the affair of Mentana, how in October, 1867, Garibaldi gathered a few thousand ragazzi at Monte Rotondo, and but for the intervention of French troops, armed with their new chassepots, might have made an end of the remaining fragments of the States of the Church.

"Eufrasia was then a girl of eighteen, living with her mother, and earning her living as a telegraph operator. The Papal Zouaves cut the wires for miles, all but one they severed imperfectly. In her young days my wife talked Republicanism, sang the red-shirt song, and dreamt of a young Garibaldino who was shot through the head at Mentana. She contrived to attach an apparatus to the severed wire of her telegraphic station, with which she tapped the Papal military bureau, read the head-quarters' orders, and during eight feverish days telegraphed Menotti Garibaldi the march of the Zouaves, the approach of de Failly, the confusion and tremors of the Vatican.

"When suddenly her messages ceased, the Garibaldini knew she had been discovered, but they could not know that she had been sentenced to be shot.

"It is here that the Blackadder shows himself. Eufrasia married me with a sob beneath her laughter as is often the way with brides. She was fertile in exasperating tricks, a pink and white devil, fior di persico the illustrious Professor named her. It was commonly reported the Cardinal had saved her life, and that she—well, who is so bold as to say a pearl may not have some hidden flaw! He was an old man, but his nephew Atteone was young. Did I know Atteone? His grandfather stole fowls in the night, and his soul is red as hell. He was forever running errands between Eufrasia and the Cardinal. The sight of him sours the wine in my stomach. You do not think Alcione resembles him?" And the ex-brigand spat furiously on the ground.

"We were no sooner settled," he continued, relighting his cigar, "than the illustrious Professor came as a lodger, and within a month our porcelain tureen was broken, the cat died, and I cut my finger to the bone. He confessed to Eufrasia that the devil whispers him in his sleep. He is forever digging in the bowels of the earth, and when not thus employed betrays an odd inquisitiveness about unknowable things. It is impossible to reason with him—you might as well argue with the police. And yet with all his curious learning he cares not a baiocco what he eats, and could not tell a cutlet from cats' meat."

"So now, signorino, having made a clean breast and spoken as I do not talk to my confessor, you will give me leave to go my way."

THE gardener's narrative faded away into the amber sunset's harmony. One goblet more of gallant wine, and in silence he bowed and departed. A phrase lingered in my thoughts. It was his suggestion that I should hear his wife's version of the events he had described. I therefore wrote the Signora Ottomana with suave Italian circumlocution, begging an interview, and upon her arrival at my hotel the following afternoon, I was amused at her odd misconception of my note. As our hands touched her eyes met mine with virgin coyness of surrender. I motioned her to be seated, and briefly alluding to my conversation with her husband, remarked that many of the lesser tribulations of life could be removed by a little frankness.

Her face glowed with pleasure, and she scarcely waited for the end of my sentence. I remembered the Cardinal, the Blackadder of her youth, and wondered if he, too, had thought that to look upon her was like the grace of a summer morning. Had their meeting been to him a fateful instant subtle as that insidious knight's move the Maestro found significant of destiny?

"Tribulations," she repeated, brushing away a tiny diamond tear,"—of course you allude to my debts. Una miseria! How generous of you, they are trifling; by the sacro santo, a mere bagatelle."

"You mistake me," I interrupted. "The shadow of Atteone's plottings rested on your husband, and he has cleared himself without reserve, however clumsily. He said that could you be persuaded to speak to me as friend to friend the story of your life would be as the fluttering wings of dawn."

"I came to you," Eufrasia exclaimed, "with trepidation and a little hope." Then with a semblance of languor she added: "You who are a taciturn man know that deep emotion is silent." And she sat, without speaking a moment, watching me with feline intentness.

"I take you at your word," I answered; "let us adhere to the things we know. Vaini opened a volume whose pages seemed the heart of mystery. But what I beheld was indistinct, as something seen across a grape-bloom mist. Suppose you turn for me a few more of those brilliant pages."

"Magari!" cried my visitor, lifting her hand in a little wave of despair, "storytelling is as much a lost art as love-making. People, nowadays, have not time for either. I will say little.

"Let me begin by telling you that a dozen years ago, when very young, living in the agitations of a revolutionary time, I was sentenced to death. Perhaps nothing so awakens a girl's nature as the knowledge that she is about to die. Remember Jephthah's daughter, that was to be her father's burnt offering, bewailing her virginity in the mountains. The shapes I had feared as a child came forth again transformed from dwarfs to giants. Yet I no more feared than the nightingale fears the dark. Two days and nights I drifted among my girlhood's memories. Then suddenly the tragedy changed to a farce. My mother threw herself at the feet of a cardinal, and after our Garibaldini had been scattered, none cared what I had done, and his Eminence took me under the mantle of a fatherly protection.

"Signor," she exclaimed, suddenly lifting her eyes, "have you never felt an emotion, never longed that love might fold you into the bosom of the immortal hills? No, your northern blood is cold, nothing I can say moves you—not though I entreated you to become a father to my child!"

"We wander from the Cardinal," I interposed.

"In the end he made me marry a brigand and gave me the house where we live. Then of a sudden he died. We were moving to Santa Prisca when the illustrious Professor appeared. He wished that same property, wished it hungrily, and matters were adjusted by his becoming our lodger. How many weeks and months has he spent delving in the earth?

"For what was he digging?" I carelessly asked.

"For what, indeed?" she echoed, "or what had I to do with Diana? In his exaltation did he take me for a goddess?

"He had been there a month when it happened. He had such endearing masterful ways, and when he spoke, something within me thrilled. It made me laugh when he declared he had loved me I know not how many centuries. At forty-five he was still handsome, and it was such a beautiful night, and my husband asleep. It is strange to remember how suddenly I loved him. By the hounds of Diana, was I not young in those days!

"That afternoon we had walked abroad together, watching where April wove its tinted glory, and delighting in those immortal lovers, the sunshine and the rose. Now in the twilight we strolled up and down the cypress walks of Santa Prisca. Sometimes it seems to me my life holds but the single flower of that starlit incantation. The night breeze thrilled with imagined kisses, my life was empty and lonesome—what wonder if in that hour's fever we turned one to the other. The same silver-throated voice spoke on the same golden words. I would have died rather than spoil that perfect evening. Do you grudge me that once in my life I knew the divine spark. I named my infant 'Alcione' in remembrance of that halycon hour. Oh, generous friend, if you would but be a father to that fatherless child!"

It was easy to discern Atteone behind the reticence of this confession, so I brought it to an abrupt conclusion.

IN 1907, twenty-five years after Vaini's discovery, the authorities excavated the Temple of Diana Aventina. They were surprised to find the passage my tutor had so laboriously opened. From the crypt we had entered they brought forth the fragments of a female statue.

I went to watch this labour of archaeological savants, with one of whom I was acquainted. "It is noticeable," he observed, "that these walls have been disturbed in recent years."

"Yes," I answered, restraining a smile, "an adept in curious arts, named Professor Vaini, penetrated their inner shrine."

"How do you know this?" exclaimed the Italian, startled from his suave urbanity.

"I was his fellow-searcher," I carelessly replied.

"And did you find anything?" asked the learned man with professional jealousy. "Yes," I answered, remembering the emotion of that wild adventure. "I found Vaini's Love."

TWENTY-EIGHT years have flown since that "Merry" Christmas, and all mentioned in this story but I have passed away. The garden of Santa Prisca has been modernised, and its new custode cares for none of these things. I occasionally visit it, and always with unchanged interest, for in its shade Yesterday is marvellously interwoven with To-morrow. In springtime, beneath the Roman glory, that peach blossom, wherein Vaini read a transcendent meaning, still breathes its fragrance of immortal days. It is in such hours one feels that so long as roses strew their petals Nature will be young—that beneath winter's brooding the sweetest love-bird song is fashioned for the spring. And, musing, in that place which to this day retains an impress of his scholarly peace, I delight myself with the thought that when years ago Vaini's earthly day ended, he found not night, but the faces of friends.

It is here that in imagination I behold again Eufrasia, a figure of prismatic hues, as though her memory drew a sheaf of colours from the light. I recall her bizarre confession, a story trembling with the passion of her race, albeit that passion had grown lifeless as yellowing love-letters. I see again the hair parted Madonna-wise over Diana's brow, and the light in her eyes like a flash of garnets, and listen to the cadence of her voice. I remember that the sight of her was like awaking and opening my eyes upon the stars. In those heedless instants I was drawn to her by the thought that she loved flowers, and birds, and care-free things, and the calm of the wildwood and December's silver garden, and the furtive steps of spring. So vivid in these years remains her phantom presence, so near and lustrous-eyed and kindling, that I wonder if, indeed, there be but a hand's-breadth between the living and the dead. And it comes back to me that when the dying Vaini sank into his last repose, he said, with a sigh, "Sleep is good." Then, suddenly rousing himself as in the presence of a new-found light, he whispered, "Fior di Persico!"

So vivid in these years remains her phantom presence, so near

and lustrous-eyed and kindling, that I wonder if, indeed, there

be but a hand's-breadth between the living and the dead.

— William Waldorf Astor.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.