RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

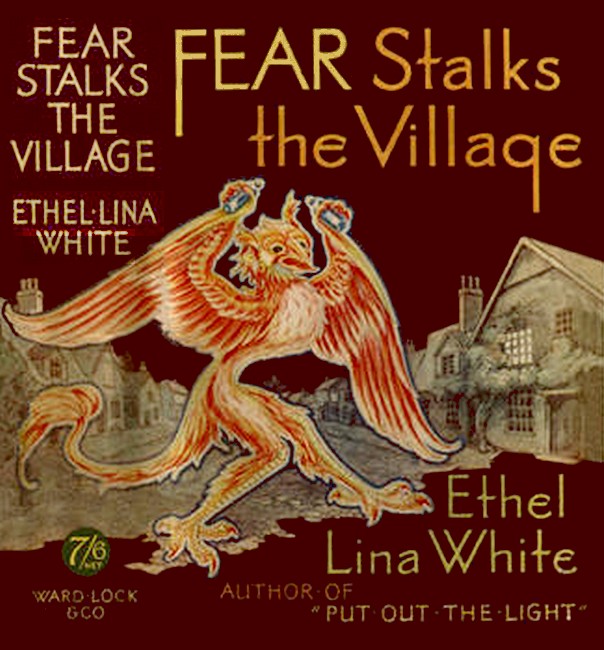

"Fear Stalks the Village," Ward Lock & Co., London, 1932

THE village was beautiful. It was enfolded in a hollow of the Downs, and wrapped up snugly—first, in a floral shawl of gardens, and then, in a great green shawl of fields. Lilies and lavender grew in abundance. Bees clustered over sweet-scented herbs with the hum of a myriad spinning-wheels.

Although the cottages which lined the cobbled street were perfect specimens of Tudor architecture, the large houses on the green were, chiefly, of later date. The exception was a mellow Elizabethan mansion—'Spout Manor', on Miss Asprey's printed note-paper—but known locally by its original name of 'The Spout'. This was the residence of Miss Decima Asprey, the queen of the village—an elderly spinster of beautiful appearance and character, and possessed of the essential private means.

Miss Asprey's subjects were not only well-bred and charming, but endowed with such charity that there was no poverty or unemployment in the village. The ladies had not to grapple with a servant problem, which oiled the wheels of hospitality. If family feuds existed, they were not advertised, and private lives were shielded by drawn blinds. Consequently, the social tone was fragrant as rosemary, and scandal nearly as rare as a unicorn.

A perfect spot. Viewed from an airplane, by day, it resembled a black-and-white plaster model of a Tudor village, under a glass case. At night, however, when its lights began to glow faintly, it was like some ancient vessel, with barnacled hull and figure-head, riding in the peace of a forgotten port.

It was a spot which was rarely visited. There was no railway station, no floating population, and a stagnant birth-rate. Even Death seldom knocked at its doors, for the natives resented the mere idea of dying in such a delightful place.

But local prejudice, which had discouraged the Old Gentleman with the Scythe, was not strong enough to bar the triumphant progress of the motor-bus. Denied passage through its streets, the reeling green monster dropped its fares just outside the village, before it looped back to the London road.

One afternoon, in early summer, it brought a woman novelist from London—a thin, fashionable, attractive person, who wrote sensational serials, in order to live, although sometimes, when slumbering dreams stirred, she questioned their necessity. Although her high French heels seemed literally wrenched from city pavements, she had made the sacrifice in order to visit a friend, Joan Brook, who was companion to a local lady.

At the invitation of Lady d'Arcy—Joan's employer—the novelist had been entertained at the Court, a massive biscuit-hued Georgian pile, surrounded with lush parkland, and about a mile from the village. During their tea they had both been conscious of mangled strands of friendship, as they talked of impersonal matters.

Each viewed the other from the detached standard of criticism. Joan thought her friend's lips suggested that she had been affectionately kissing a freshly-painted pillar-box, while the novelist considered that the girl had run to seed badly. But when they walked back to the village they had been insensibly welded together in harmony, by the waving beauty of the fields, ripening for hay and steeped in the glow of sunset. Joan's sunburnt face proclaimed the fact that she never wore a hat, but the novelist, too, took off her tiny mesh of crocheted silk, without a thought of the set of her wave. Smoking as they sauntered, they entered the shady tunnel of the Quaker's Walk, half a mile of chestnut avenue.

"Like it?" asked the novelist.

"Love it." Joan's blue eyes glowed. "I know you think I'm buried. But this corpse hopes the Trump won't sound just yet. I've never been so happy."

"Pray it may last...Any social life?"

"Tennis and garden-parties, later on. The three big houses are the Hall, the Towers and the Court. The Court is ours. The Squire lives at the Hall. The rich people of the neighbourhood live at the Towers, but they're always away."

"Any men?"

"Two. The parson and Major Blair. The Major's a manly man and he belongs to Vivian Sheriff, the Squire's daughter. Vivian and I are the only girls here."

The novelist raised her painted butterfly brows.

"Let me get this straight," she said. "There's the Vivian-girl and the biological specimen. That leaves you and the padre. What's he like?"

"Rather a thrill. Big and black, with a voice like a gong. You should hear him hammer and bellow on Sundays. But I believe he's the genuine thing."

"Going to marry him?"

Joan was conscious of a slight recoil, so that she had to remind herself of her former standard of modern frankness.

"If he doesn't break away, I may," she replied. "After all, I've had to submit meekly to employers all my life, and I'd like to do some bossing myself, for a change. Purely, can't you see me telling the cottagers to boil their potatoes in their skins, and not to have any more babies?"

"I'd believe anything of you, Brook," remarked her friend. "By the way, what's your Lady d'Arcy like?"

"Big and vague, and drifts about aimlessly. I've nothing to do but to act as some sort of anchor. I get a big salary which I can't spend here. But it's not wasted at home. They're nearly sunk, bless 'em."

The novelist's face was not painted to be revealing, but she nodded to show her sympathy with the prevailing economic depression as she studied Joan through her monocle. The girl was tall and strong, with a face expressive of character, and fearless eyes. She wore a sleeveless white tennis-frock and silver slave-bangles on her brown arms. Although she had grown more solid, she seemed to be of compact virtues and charm.

"Well? The verdict?" asked Joan.

"Guilty!" replied her friend. "You're a last year's model. You've put on weight. Your lips look indecently like lips. And—darling, I'm jealous as hell."

"I know I wouldn't swap jobs with you." Joan gave a contented laugh. "This is really a marvellous place, Purley. Everyone has a pedigree and a private income. Everyone's kind. And, my dear, everyone's married."

"I get it. No love-babies, no drains. Gosh, what a picture!" As the two women emerged from the gloom of the avenue they saw the village with its ancient cottages and choked flower-gardens, all steeped in the carnation glow of sunset. At each step they seemed to turn a fresh page of a fairy-tale, with illuminated borders jumbled with box-edging, sage, damson-trees, beehives and a patchwork quilt of peonies, pinks and pansies. Golden girls and boys skipped in the street, while cats were growing mysterious as they awaited the herald—twilight. Soon their real life would begin.

The novelist surrendered herself to the enchantment, although her lip curled at evidence of the survival of the Feudal System, for all the children bobbed to the 'quality'.

As they lingered on the green, Joan pointed to a solid house of buff stucco, adorned with a clock-tower.

"That's 'Clock House'," she said. "The Scudamores live there. I hope we'll meet them, for they're types. They're terribly nice and terribly happily-married. I call them 'The Spirit of the Village'. You'd find them 'Copy'."

The novelist stifled her groan, as Joan proceeded to do the honours of the village. She waved her cigarette towards a grey stone house which was backed by the Norman church.

"The Rectory. My future home." She forced the note of impudence. "Just behind us is the doctor's house, but the walls hide it. It's Queen Anne and rather sweet. He and his wife always play tennis after dinner. You can hear them."

As they stood, listening, the dull thuds behind the rose-red bricks mingled with the faint laughter of children and the cawing of rooks in the elms. Suddenly, the novelist fell prostrate before the cumulative spell of the village.

"It's perfect," she declared. "I wonder if I could rent a cottage for the summer."

"If you did you'd never go back to London," Joan told her. "Nobody ever goes away, not even for holidays. Look out. Here are the Scudamores."

She guiltily hid her cigarette behind her back, as a middle-aged couple advanced, arm-in-arm, over the cobbles. The man had a clean-shaven, long-lipped, legal face, to proclaim him a lawyer with the best County connection, together with a nose which had been in his family for centuries.

His wife was also tall, and possessed of bleached beauty and elegance. Her luxuriant fair hair was fast fading to grey, and her draperies were indefinitely grey-green in colour, like a glacier-fed river.

She greeted Lady d'Arcy's companion with a gracious bow, but did not even glance at her companion.

"She didn't really like me," murmured the novelist when the Scudamores had passed. "Do I look like a fallen woman? Tell her I'm respectable, if painted."

"My dear," gurgled Joan, "she's so charitable that she would not take a chance of disliking you. That's why she wouldn't look. She's a bit overwhelming, but a real Christian...I say, Purley."

As Joan paused and regarded her friend intently, the novelist braced herself to meet the inevitable question.

"Can't you make a story out of this village?"

"You would say that." The novelist's tone was acid. "But, my good woman, what possible copy could I find here? Jane Austen's beaten me to Cranford. The truth is, my child, if there'd been no Fall, there'd be no Publishers and no Lending Libraries."

"But there must be a story everywhere," persisted Joan.

"Not for me."

"Oh, come, Purley, have a shot at it. I want to be amused."

The novelist puckered up her painted lips in a whimsical smile.

"All right," she conceded. "But I'll have to follow my own special line. Something like this. This village seems an earthly paradise, with a population of kindly gracious souls. But the flowers are growing on slime. When twilight falls, they light their lamps and draw down their blinds. And then—when no one can see them they lead their real lives."

"For example?" urged Joan.

"Well, to begin with, that highly-respectable married couple, who disapproved of my lips, are not really married to each other, but are living in sin."

"You priceless chump. Tell me the story of their double life."

"No, I must outline my synopsis first and collect my characters...Hum. The Parsonage is hidden by those discreet yews, so the Rector hasn't got to wait until dark. I think, at this moment, he's throwing a bottle-and-pyjama party with some very hot ladies from town. As for your doctor, he's slowly poisoning his wife, and their tennis is his opportunity. When they've finished their game, she'll be thirsty, and her devoted husband will see to it that she gets the right quencher. Something safe, and very painful."

"Ugh," grimaced Joan. "When I'm Mrs. Padre, I'll ban your novels in our village library."

Once again she was urged to speak recklessly of her designs on the Rector, from a clouded feeling that she was protecting herself from the unforgivable charge of sentiment. Lighting another cigarette, she strolled after her friend, who was peering through the scrolls of lacey iron-work which ornamented the gates of 'The Spout'.

In the distance, against a background of laurels, the novelist saw an austere, silver-haired woman, seated on a bench beside a lily-pond. Her hands were clasped and her eyes raised as though in meditation. She held her pose so rigidly that the folds of her white gown appeared to be carven marble, creating the illusion of an enshrined saint.

But even as the novelist readjusted her monocle, the statue dissolved into life at a touch of warm humanity. Down the yew alley, pottered a little dumpy woman, carrying a glass of milk on a tray. The tall lady patted her shoulders, in thanks, and then drained the glass hastily, as though in obedience to the laws of nutrition, but with a supreme contempt for digestion.

When she walked towards the house, followed by her companion, the difference in their heights was ludicrous, for she was above the usual stature, while her employee was below the average.

"Miss Asprey and her companion, Miss Mack," whispered Joan. "She's an earthly saint, and so good she's not quite human. Miss Mack simply worships her, and runs after her like a little dog."

"Then they shall go into my serial," announced the novelist. "Listen. In reality, your pure, saintly Miss Asprey is a secret sadist. Directly the blinds are drawn, she will begin to torture her poor little companion."

"Can you help being a fool?" asked Joan unkindly.

"You asked for this story, didn't you? Now I'll outline the plot, while we're waiting to go to the bus."

Leaning against the white posts which ringed the green, Joan listened dreamily to her friend's sensational story, which foamed with melodramatic incidents. But even while she laughed at its utter absurdity, she resented it, subconsciously, as an outrage.

'What's the matter with me?' she wondered. 'Purley's really terribly funny. It's only a leg-pull. But—it's cheap.'

She was grateful when her friend grew tired, and glanced at her watch.

"Better be pushing on," she remarked. "Although I just hate to leave this."

The grass was like water-silk, mottled with bars of sunken gold and the cottages rocked through a lavender mist. Twilight was veiling the street as they walked towards the inn, but there were no lights in the village. People sat at open windows, or hung over gates, exchanging greetings and gossip with passers-by. Everyone seemed to be sharing the universal friendship of this interval 'between the lights'.

The moment of withdrawal was at hand.

Presently the novelist stopped, arrested by the sight of a dim, low, lath-and-plaster building, enclosed within a paved garden.

"Gosh, I can smell mildew," she said. "I take it, that is the oldest house in the village."

"I knew you'd make that mistake," exulted Joan. "Every tripper does. That's only a fake-antique, built from fragments of old barns, and it's got every sort of modern improvement. I love it, but the village resents it, especially as its owner is a newcomer. She's only been here eleven years."

"Who's the lucky woman?" sighed the novelist.

"Our local novelist—Miss Julia Corner."

Instantly the writer registered that automatic nonrecognition of her profession towards other members of the tribe.

"Never heard of her. What name does she write under?"

"Her own, and she does jolly well, too. She's a dear old Jumbo, with a perfectly grim sense of humour."

"Hum." The novelist thought of her own tiny mansion-flat. "Evidently, she makes virtue pay. Any special line?"

"Yes, she's the President of our local Temperance Society, and she makes the children sign the Pledge."

"Then, to pay her out for having a better house than me, I'll put her into my serial. She's a secret drinker and hides a bottle of whisky in her wardrobe. At this minute, she is lying under the bed, dead drunk."

Even as she spoke, the oaken door, white with age, was opened, and a massive figure blocked the entry, waving a teapot, in welcome.

"Come in for a cup of tea," she shouted.

"Sorry, but we're catching the bus," called Joan.

Instantly Miss Corner swayed down the flagged path to the garden gate, moving with the deceptive speed of an elephant. The writer from London saw a big red face, radiant with good-nature, bobbed iron-grey hair—cut in a fringe—and beaming eyes behind large horn-rimmed spectacles. Miss Corner wore an infantile Buster Brown blouse, adorned with wide collar and ribbon bow, and a grey tweed skirt.

"I'm just writing a short tale for the Christmas Number of a Boy's Annual," she announced proudly. "It's commissioned, of course. I take a generic interest in boys. Won't you come in and be introduced to my collaborator—Captain Kettle?"

She laughed heartily at her joke, but the source of her amusement was the stranger's painted lips and monocle. When Joan introduced her friend, she held out her big hand cordially.

"A fellow writer?" she exclaimed. "What name do you write under?"

"I'm sorry, but we mustn't stop," said Joan hastily.

"Pity," remarked Miss Corner. "I should love to talk shop. For instance, do you let yourself be grabbed by your characters, or do you go out deliberately to collect copy?"

"She's already found a story in this village," said Joan.

"Then I presume it's for your Parish Magazine," grinned Miss Corner. "Well, since you persist in going, I must return to my boys. Good-bye. Give my love to my special boy—Eros."

They heard her chuckle rumbling from behind the sweet-briar hedge as they walked away.

"What'd you think of her?" asked Joan.

The novelist did not reply, for she was suddenly gripped with overwhelming nostalgia. At that moment, London seemed so far away—a place to which she would never return. She felt as though she were being held by the village—no longer a sunset pool of beauty—but a witched, forgotten spot of whispers, and echoes, and old musty twilight stories.

"Are we far from the inn?" she asked wearily.

"No. Nearly there."

"Good. I could do with a gin-and-it."

The King's Head was a long, low, ancient building, with the faded oil-painting of some dead monarch pendant above its doorway. A faint glow from a hanging ironwork lantern flickered feebly on peeling plaster walls and tiny lattice windows. The writer flopped down on an old settle and stared out at the spread of dark silent country.

"Didn't you want a drink?" asked Joan hospitably.

"No. Desire is dead."

The friends sat in silence, which was presently broken by the novelist.

"Do people ever try to get away from here?" she asked.

"They don't want to," replied Joan. "Miss Asprey has a housemaid—Ada—who's the most beautiful girl I've seen. You'd think she'd want to go on the Stage or the Films, but her only ambition is to be Miss Asprey's parlourmaid. It would take about a ton of dynamite to shift her to Hollywood."

The writer made no comment, for her very mind seemed root-bound.

And then—suddenly—the miracle happened. Two golden sparks appeared in the distance, while a murmur vibrated through the darkness. As they watched, the lights grew brighter and larger, and then were lost in a dip of the landscape. But the hum deepened into a snarl, and round the bend of the road reeled a green monster motor-bus, with brilliant windows and the magic name 'LONDON' glowing in flaming letters.

It looked so utterly incongruous in that forsaken wilderness, as to appear unreal, like a vision of the Mechanical Age of the Future projected before the incredulous vision of some dreamer in the Past.

At the sight of it, the novelist's heart leaped in welcome. London. It reminded her that she was going back to grime and noise—to pavements and city lights. In her joy, she was swept away on a wave of insincere enthusiasm.

"I've loved every minute," she declared. "Good thing I'm going back, or the village might have got me, too."

"Too?" echoed Joan. "What d'you mean by that?"

The writer looked at her friend and was suddenly aware of the origin of her change.

"You're in love, Brooky," she said accusingly. "The village can't get you, because a man's got in first. Well, good-bye. Don't forget to tell me how my serial works out."

"I won't," promised Joan. "Shame you've got to go back."

"A shattering shame."

Joan was guiltily conscious of relief as she watched her friend climb briskly into the bus. In her turn, the novelist sank gratefully into her seat, and waved her hand in farewell. She was leaving peace and beauty, and she left them gladly. When the dark countryside began to slide slowly past the window, she watched it flow behind her, with a smile on her lips.

She was going back to London.

Joan stood before the inn and watched the motor-bus, until it had roared out of sight. Slowly the dust sifted down again, to mingle with the soil of its origin. The fumes of petrol rose higher and higher, until they were dissipated in the aether. The faint snarl of the engine sped on its journey to the last lone star.

'I'm glad old Purley's gone,' thought Joan, lighting another cigarette for company.

When she walked slowly through the village, the moon had risen and was silvering the old Tudor buildings, transforming them to ebon and ivory. Everyone had gone indoors; the lamps were lit and the blinds were drawn. Once again, the old ship rode at anchor in the dead port of Yesterday.

Joan was reminded of her friend's serial, by those screened windows, and her lip curled with derision. She knew each lighted interior so well, and was familiar with the evening's procedure. Miss Corner was tapping away at her incredible epic of how the Mile was won by the smallest boy in the school. The doctor and his wife were reading, for they subscribed to a London Library. In this big house they listened in to classical music on the air, and in that small one they drank cocoa and played Patience.

Everywhere was domestic drama, staged in the peace of Curfew. There were contented servants in comfortable kitchens; well-fed cats and dogs sleeping on rugs; clocks ticking away serene hours.

There was nothing to tell her that her friend's fantastic melodrama was justified by even one instance of insecurity and misery, or what was really happening behind drawn blinds. Only the walls heard—and they kept their secret.

TWO days had passed since the novelist's return to London, and nothing survived her visit but a few gnat-bites on her ankles and a filmy memory. The village retained even less of her personality; Joan washed her entirely from her mind, while no one mentioned the painted stranger with the monocle. The picture-paper which was printing her current serial was not in local circulation, so not even her work remained.

But, although life flowed on with the tranquillity of a brimful glassy river, the peace and security of the village was about to be shattered. Like a certain small animal which precedes a beast-of-prey, the novelist had been the herald of disaster. The communal harmony was static; but the first disrupting incident was timed for that evening.

Dr. Perry was late in coming home to dinner. He pushed open his garden-gate with his habitual sense of a mariner returning to port, as he saw the mellow red-brick front of the Queen Anne house. The shaven lawn was veined with evening sunlight, and the wide border of tall pink tulips and forget-me-nots—although imperceptibly past perfection—was still a cloud of shot azure and rose.

He was met on the steps of the porch by a reproachful wife. He had married his dispenser—the daughter of an impoverished Irish peer—and, therefore a stranger; but the village had accepted her on the credential of her husband.

At first sight, they appeared an ill-assorted couple. The doctor belonged to one of the oldest families, and was pale and thin, with a pleasant manner and a tired voice, while his wife was very dark and possessed a parched, passionate beauty.

The black rings around her eyes and her crumpled evening-gown of golden tissue gave her the appearance of a disreputable night-club hostess greeting the dawn; but a strong scent of violet-powder was a clue to a domestic occupation. She had just finished the job of bathing two resisting infants, and, as maternity was, to her, an emotional storm, she had exhausted herself with their wriggles and her own intense rapture.

"Well, Marianne," said her husband, kissing her lightly, "how's the family?"

"In bed," replied Marianne Perry, in her deep, throbbing voice, "I do wish you'd been here to see them in their bath. Micky nearly swam."

"Good. But you look a wet rag," remarked the doctor, as they walked through the wide, panelled hall. The western sun shone through delphinium-blue curtains, revealing an artistic interior, which was rather marred by scattered toys and two perambulators parked in corners.

"Got a pain." Marianne clasped the region of her waist. "Darling, are you poisoning me, so that you can marry my rival, Miss Corner?"

The doctor was false to the London novelist's conception of a double-character, for he displayed no anxiety.

"Too many green gooseberries," he said lightly. "Better take some bicarbonate of soda. It'll settle you, one way—or the other."

"Make me sick? I want my dinner, you brute." Marianne dragged the doctor away from the staircase. "No, you can't change. You're too late. Dinner's dished up."

Arm-in-arm, they entered the dining-room, a pleasant, well-proportioned apartment, hung with oatmeal linen and furnished with a walnut suite. The table-silver was tarnished and the service sketchy, but the meal was remarkably good. Apparently the doctor was not making a success of poisoning his wife, for she ate with a good appetite, in spite of her alleged pain.

"How's the practice?" she asked presently.

"As usual," replied the doctor. "Nothing revealing."

"Been to see Miss Corner?"

"No."

"Liar. Let me see your case-book."

The doctor laid it on the tablecloth without comment.

"I'm going to make up the books after dinner," announced his wife, flicking open the pages.

She spoke with relish, for this was a favourite occupation. The village took its health seriously, and was punctilious in its payments, so that she knew that she was not merely rolling up a paper income when she added up the columns.

"'J.C.', 'J.C.'," she murmured. "Miss Corner's as good as an annuity. What's the matter with her?"

"Suppose you ask her yourself?"

"I know. She's too fat. Is she rich?"

"I don't know."

"But, Horatio, that house cost thousands to build, and there is no money shortage there. She pays her cook seventy. She can't do it on her silly books."

"No?"

"'No?'" Marianne parodied her husband's toneless voice. "My good man, are you ever interested in anything or anyone?"

"That's a curious charge to make." The doctor spoke with his usual inertia, but there was a fugitive gleam in his quiet eyes. "Actually, I endure a chronic condition of frustrate curiosity...I admit, I care nothing for anyone's income, so long as he pays my bill, and I can't get excited about common-or-garden ailments. But—I would like to know what is really at the back of anyone's mind."

"Does anyone?" asked Marianne. "Do you know me?"

"No." The doctor winced as his wife began to dismember a fowl with her usual furious energy. "I wish I did. I should know then why you insist on carving. You'd make a devastating surgeon."

"I carve, because I hate to see you with a knife. You're so deadly professional that I feel I'm watching an operation. And that's a true message from the Back of Beyond, Mr. Curious...By the way, Micky's got a new word. It sounded just like 'bloody'. But I'm waiting for him to say it again, and living in hope."

During the remainder of the meal, Marianne talked exclusively of her infants. Before it was actually finished, she sprang to her feet and again clasped her waist passionately.

"I was a fool to have any dinner," she exclaimed. "My inside's woke up and is swearing at me like mad."

"Bicarbonate," murmured her husband. "How about some tennis, later on?"

"No, my beloved, Momma's no time to play with her biggest baby, this evening. After I'm through with the dispensing I'm going to get busy on those books."

Her eyes glowed at the prospect, and she entirely forgot her interior grumbles.

"I just love it," she declared. "Figures are a real joy to me. I ought to have been a bookie. And all the time I'm jotting down items I'm saying, 'Here's a packet of rusks for baby', and 'Here's new woollen panties for Micky'. What are you going to do?"

"Finish my novel."

The doctor strolled into the drawing-room, which was a cool, pleasant place, of faint pastel-tints, and green from the shade of plane-trees. Stretched on the faded old-rose divan, with his boots wrinkling the silken spread, he lost himself in the translation of a Russian play. Presently, Marianne entered, loaded with stationery, which she dumped down on the bureau.

She gave a cry at the disorder of the couch.

"Curse you, darling. Those cushions are clean."

The doctor slipped guiltily off the divan.

"I think I'll go and smoke a pipe with the padre," he said.

"Do. Go before I slay you. Give my love to that young man and tell him to stop shouting in the pulpit. As a mother, I protest against his waking up all the babies in Australia. And you needn't hurry back, for you're not popular. Leave me your novel."

The doctor fished it up from the carpet.

"Better not," he advised. "Like a woman, you'll miss its philosophy, and pick out all the improper bits. And then you'll slang men, generally, for their filthy taste...Good-bye, Marianne."

He left his wife feverishly turning over the pages of a ledger, while he mounted the shallow wide oaken staircase, in order to wash and change his coat. When he had finished his toilet, he stole into the night-nursery, where the two babies lay asleep, each with doubled fists and damp, downy head.

Although one was ten months the elder, there was a strong likeness between them; both were palpable little doctors, and outwardly ignored relationship with their temperamental mother. They were luxuriant babies, too, in expensive sleeping-suits, and tucked up under delicately-hued, ribbon-bound, air-cell blankets. Opulent satin bows decorated their white enamelled cots, and they had huge furry animal-toys for bed-fellows.

As the doctor stood looking down at them, the door was softly opened, and Marianne entered. A strap of her golden gown had slipped from her shoulder, and a lock of dark hair fell over her cheek, giving her a semblance of utterly disreputable allure. She threw her bare arm around her husband's neck and completed a picture of domestic happiness.

"Aren't they beautiful—beautiful?" she crooned.

"They are," agreed the doctor.

Marianne's clasp on his shoulder tightened to a clutch, and she burst into tears.

"Ought we to have done it?" she cried. "They're so helpless—so entirely dependent on us. Suppose anything happened to you? Or to me? Strangers to care for them. Suppose the practice went down? What would become of them?"

Her husband instinctively shut his eyes as though blinded by the glare of tragedy. The next moment he had recovered his self-possession, as he patted his wife's arm, with a gentle laugh.

"You're morbid. It's probably due to acidity. You'd better go and take that bicarbonate."

TEN minutes later Dr. Perry lay stretched on a shabby 'Varsity chair on the Rector's yew-shaded lawn, while his host paced the daisied grass, waving his pipe, and declaiming as he tramped. In his character of a human dynamo, he was a source of interest to the doctor's curious mind; and, as he smoked, he studied him with cool detachment.

The Reverend Simon Blake was a tall, bull-necked man, of great muscular strength, with blunted, classic features, crisp coal-black hair, and flashing, arrogant eyes. He looked rather like the offspring of a union between a battered Roman emperor and an anonymous plebeian mother. His voice was strong and vibrant, and all his gestures expressed vehemence. He appeared never to have acquired the habit of sitting, and he talked continuously.

Dr. Perry knew that his display of overflowing vitality was misleading, and that he was only in the process of rekindling fires which had blazed too fiercely, and died. It was the last back-kick of nervous tension which made him such a restless planet of a fellow. He had worked himself out in a Dockside parish, sticking to his job long after he was beaten. Not until he had crashed, both mentally and physically, had he consented to accept this living in the country.

"Sit down, man," urged the doctor. "You're like the spirit of atomic energy."

The Rector obediently dropped down on his protesting chair, with the force of machinery, only to spring up again.

"This place, doctor," he said, "is perfect. I pray I may end my days here. Look at it, now."

He waved his pipe towards the village street, which staged the usual sunset pageant. Children skipped and played on the cobbles, exactly like golden girls and boys and little chimney-sweepers, long passed to dust. Women gossiped over their garden gates, just as they had gossiped in Tudor times, and they talked of much the same things. At a quarter-to-eight, Mr. and Mrs. Scudamore emerged from the gates of the Clock House for their evening stroll. The lady wore a feathered hat and a fichu of real lace, and all the village did homage to the Honiton point.

The doctor studied the Rector, and he—in his turn—watched the stately advance of the pair. The clergyman noticed how the lawyer's frost-bitten face thawed whenever he spoke to his wife, and he was delighted by her responsive smile. Yet they were not too engrossed in each other to pass a couple of sunburnt children, in old-fashioned lilac sun-bonnets. The little girl took a sugar almond out of her mouth, to prove that its colour had turned from pink to white, and the Scudamores rather overdid their pantomimic surprise at the miracle.

The doctor's lip curled slightly, but the Rector beamed.

"Lovers still," he said. "That's a perfect marriage."

"In the sight of God and the neighbours," murmured the doctor. He added with a bleak smile, "There is only one danger in this 'God save the Squire and his relations' attitude. The villagers would be too sunken in tradition to complain, in case of abuse. They know they wouldn't be believed."

"Abuse?" echoed the Rector. "Here? Are you mad?"

"Probably. Most of us are, if we're normal. By the way, when I get a free Sunday I'm coming to hear you preach, padre. You're the one man who can keep me awake."

The Rector grinned in a boyish, half-bashful manner.

"I know I'm a noisy fellow," he confessed, "but oratory is my talent. It's out of place here, but I dare not let it rust. Besides, it may do secret good. Who knows?"

He knew that his red-hot Gospel, with which he had blasted his old Parish to attention, was like a series of bombs exploding under the arches of the Norman church. But habit persisted, and he exhorted his hearers, every Sunday, to search their hearts for hidden sin. The congregation remained tranquil, while he liked the sound of his own organ-voice.

The Scudamores had disappeared round the bend when the delicately-wrought iron gates of 'The Spout' were opened to let out a girl. In the distance she looked like Joan Brook; and the doctor, who was also misled, watched the sudden flicker of interest in the Rector's face. When she drew nearer, however, it was evident that Joan was only her model, for she was far more beautiful than Lady d'Arcy's companion.

Her hair was red-gold, her eyes blue-green, and her complexion a compound of cherries and cream, while her features and her unwashed milky teeth were perfect. She wore a sleeveless white frock of cheap crÍpe-de-Chine, silk stockings of the shade known as 'muddy water', and silver slave-bangles on her shapely arms. Only her red hands betrayed her dedication to the tasks of domestic service.

It was Ada—Miss Asprey's famous housemaid, and the acknowledged beauty of the district. She crossed the green, and then lingered under the wall of the raised Rectory garden, in order to consult her wrist-watch, which, outwardly, was exactly like Joan Brook's. Directly she saw the two men smoking above her, she dropped as simple a curtsy as any of the village children.

"Good evening, Ada," beamed the Rector. "Finished with work?"

"Yes, sir," smiled Ada.

"What do you find to do on your evenings out?" asked the Rector.

"Plenty, sir."

"And you never get bored, or miss the Pictures?"

"Oh, no, sir." Ada's violet eyes were filled with reproach. "I'm going home, to see our mother's new baby."

"A new baby? Fine. What is it?"

"A boy, sir."

Glancing again at her watch, she dropped a second curtsy, and hurried in the direction of the Quakers' Walk.

"Now, isn't that refreshing?" demanded the Rector. "Compare it with stuffy cinemas, with their crime and sex pictures...By the way, I didn't know Mrs. Lee had a baby. How old is he?"

"About twenty-six," replied the doctor. "He's the Squire's new chauffeur."

The Rector laughed heartily at himself.

"Fell for it, didn't I? She took me up the garden. But after all, she's got the real thing, and that's better than watching canned love on a screen."

"Hum, in the one case, fourpence may be the extent of the damage. In my profession I've learned that tinned goods may be less harmful than in their original state."

"No." The Rector's eyes blazed. "Not here. There's no immorality in the village. And no class-hatred or modern unrest. They reflect the general tone of kindness and good breeding. I've never known a place with so little scandal. And the charity almost overlaps. No wretched slums, no leaky roofs or insanitary conditions."

"I agree," said the doctor in his tired voice. "But this fact remains. None of the local ladies use makeup, not even my own civilised wife, because Mrs. Scudamore has decreed that paint is an outrage on good taste. Yet, do you ever see cracked lips, or damaged skins?"

"What are you driving at?" asked the Rector.

"Merely that they must use vanishing-cream and colourless lip-salve...The moral is, padre, that human nature remains the same, everywhere, and dark places exist in every mind."

"Well, you probably know more about that than I do." The Rector's voice was regretful. "People no longer confide their difficulties and doubts to their parson. But, as a doctor, you must catch them off guard."

"Do I?" The doctor smiled as he tried, in vain, to catch a small white moth. "No, padre, they always put on clean pillow-slips for the doctor's visit."

The Rector made no comment; at last, even he was drugged to silence by the combined spell of twilight and tobacco. The purple and gold bars of sunset had faded from the sky—the voices of the gossiping women were stilled. People went indoors, to eat dinner or to prepare supper. The Scudamores made their stately re-entry of the Clock House—arm-in-arm, to the very last cobble-stone. In the gloom of the Quakers' Walk, Miss Asprey's beautiful Ada kissed and cuddled her mother's new baby, who had grown a Ronald Colman moustache.

Lights began to prick the gloom, while the first star trembled in the faint green sky. Across the green, little golden diamonds, like clustering bees, glowed through the lattice-panes of Miss Asprey's Elizabethan mansion.

The Rector was stirred, by the sight of them, to a revival of enthusiasm.

"As you say," he remarked, "no one can be perfect. Yet Miss Asprey is as nearly a saint as any woman can be. She has an influence on me which is almost spiritual. I go to see her whenever I'm worked-up and jumpy, and I come away with my prickles all smoothed down."

The doctor studied him, through his glasses, as though he were something on a microscope-slide.

"Do you? Interesting. As a matter-of-fact, I've also noticed that that good lady seems to possess some soothing quality. But it's disastrous to a man of my lethargic nature. After I've been at 'The Spout', I feel about as torpid as though I'd taken veronal. I used not to notice it, so I suppose I'm growing old, or extra slack."

Both men spoke casually, and their words were lost upon utterance. They could not tell, then, that when they were plunged, later, into the dark labyrinth of mystery, a gramophone record of the evening's conversation would hold a clue to one of the key-positions.

"You ought to take a holiday," advised the Rector.

"Too much fag."

The doctor's dragging voice was scarcely audible. Night was dropping on the village in veil upon veil of cloudy blue, citrine, and grey. The men sank lower in their chairs and sucked at their pipes, at peace with Nature and themselves. They might have been sunken in the subaqueous gloom of a fathomless sea—untroubled by the screws of steamers churning the waters above.

Yet, even then, the first blow was about to fall on the village. Far away, in the distance, sounded the postman's double-knock. Presently, he appeared in sight, a little globe of a man, with steel-rimmed spectacles. He rejected the Rectory, but entered the gates of 'The Spout'. They heard his familiar rat-tat, and then they saw him come out of the garden again, and go on his way—but they did not recognise him for the herald of disaster.

Presently the Rector stirred to life.

"Chilly," he remarked. "We'd better go in and have a whisky."

As the men rose stiffly from their low chairs, the Rectory gate creaked, and Rose—Miss Asprey's unhappily-named parlourmaid—stalked up the gravel drive. She was a gaunt, long-lipped dragoon of a woman, and had been in service at a Bishop's palace, so did not pay the local homage to the parson. Her voice was harsh as she gave her commands.

"Miss Asprey's compliments, and will you please to come over, at once."

"Is it urgent?" asked the Rector, not too pleased at the prospect, for his lighted study windows called him, and the whisky was waiting.

"The mistress says please come at once, as it's most important."

"Certainly, then, I'll be over directly."

Rose's tall, black-and-white figure led the way down the path, as the Rector turned to Dr. Perry.

"I suppose you won't wait for me?"

"Thanks, padre, I will," replied the doctor. "I believe Gillie Potter is on the air tonight, so I'll amuse myself with your Wireless."

As he looked after his host, his usually listless eyes were bright with interest, and he meant to wait until midnight, if necessary, for the Rector's return.

For he was positive that his famished curiosity was going to have a feast, and that—for the first time in the history of the village—there would be no clean pillow-slips.

WHEN the golden diamonds gleamed through the windowpanes of Miss Asprey's dining-room, she was seated at her evening meal, with her companion, little Miss Mack, and quite unconscious that, across an empty stretch of grass, two men were discussing her character.

As she sat in a high-backed carven chair, and mechanically ate what the parlourmaid had piled upon her plate, she seemed unaware of her surroundings, for she stared at the opposite wall, as though trying to pierce it with the intensity of her vision.

In the early sixties, she was slender and upright as a girl. Her face bore traces of former beauty, in spite of many lines, and a sharpening of nose and chin—forerunner of the fatal nutcracker. The tint of her complexion was pale ivory, and her expression both pure and austere. She wore a black velvet dinner gown, which suited the silver glory of her hair so well as to suggest that even saints have their share of vanity.

Although she looked so fragile, her appetite was enormous, but she appeared to eat without enjoyment—rather like a machine crushing fodder which was necessary for the repair of a body worn out by a consuming flame-like spirit. Not only was she a woman of tireless energy, broken by lapses into fierce concentrated meditation, but she adhered to the habits of her early life.

The only child of wealthy parents, Decima Asprey had been at the same school in Germany as Miss Julia Corner; but she was much older than the novelist, and had left to be presented at Court. After one Season only, she grew tired of leading the life of an average Society girl, and went into Retreat, with the idea of becoming a nun. Commonsense prevailed, however, so that she chose a career better suited to her temperament, becoming Matron of a Home for Fallen Women, in a large industrial city.

She did not spare herself in well-doing, and—like the Rector—she overworked and finally broke down. While she was only in the early thirties, she came to the village to recuperate, and stayed there for nearly thirty years. The Elizabethan mansion—Spout Manor—was then in the market, and after she had bought it she never slept under another roof, in contrast to Queen Elizabeth I's alleged habit for trying strange beds.

Very soon her gently dominant character asserted itself, and she became ruler of the village. Mr. Sheriff—as head of the oldest family—held the prestige of Squire; the Scudamores were self-appointed guardians of the public tone; but above them all, shone Miss Decima Asprey.

She sat at the head of the long dining-table, and the gaunt Rose waited on her assiduously, while little Miss Mack 'made a long arm', and helped herself. She was a stocky little woman, about twenty-five years younger than her employer, with a pale, clear, polished complexion, like a china doll's, light blue eyes, and faintly smiling lips. She looked rather stupid, through over-amiability, but serene and good.

Upstairs, in her bedroom, a half-finished letter lay inside her blotter. It was addressed to a certain Miss Smith, of London, and was filled with praise of Miss Asprey, and contentment with her happy lot.

'Miss Asprey is an Earthly Angel,' she had written. 'She took me in, when I was down and out, and I feel I can never do enough to repay her. She is so very kind and good, and gives me light work, which makes the time pass quickly and pleasantly. I look and feel much better. I am only living to repay her for what she has done to me. This house is beautiful, all wood, and everyone says it is like a Museum.'

Now this was rather noble of little Miss Mack, for 'the Spout' was not at all to her personal taste. She preferred rose-pink wall-paper, electric-light, and a nice clean white tablecloth. Visitors might praise the historic perfection of the Tudor mansion, and rave over its furniture, which were all genuine period pieces; but they sat, for a short time only, on its hard oaken chairs, and then rolled away, on cushioned seats, back into the Twentieth Century.

As she munched her bread-and-cheese Miss Mack's china-blue eyes roamed about the room, semi-lit by one hanging oil-lamp. The panelled walls—black with age—were rendered invisible by the shadows. The oaken table was bare, save for some mats of coarse hand-woven linen. The food was chiefly vegetarian—lentil-soup, salad, biscuits, butter, cheese and fruit. There was only barley-water to drink, although the temperature remained low at 'the Spout'.

Miss Mack looked distrustfully at the dish of green-stuff, for she did not like raw lettuce, which did not satisfy her appetite, and only gave her flatulence.

'If you're lucky, you get a rumble,' she thought. 'If you're unlucky, you get a slug.'

Then she remembered the beautiful food she had once enjoyed, when she stayed with a farmer uncle in the country. When they killed a pig, there was a feast of good things—faggots, brawn, chitterlings, and a delicious dish, called 'Black pudding'. She had been told that it was made from the blood of pigs—but that did not alter the fact that it was both filling and savoury.

In the distance, she could hear the postman's double-knock, but without interest, for few people wrote to the insignificant Miss Mack. Then her watchful eyes noticed that her idol, Miss Asprey, gave a slight shiver, and, instantly, she was on her stumpy feet, ready for service.

"May I fetch you a shawl, Miss Asprey?" she asked.

"No, thank you." Miss Asprey rose and walked to the door, followed by Miss Mack, whom she waved back to her chair. "Please sit down and finish your meal," she commanded.

When the door was closed behind her, Miss Mack spoke to Rose.

"What are you having for supper, in the kitchen?"

"Poached eggs and cocoa," was the reply.

Miss Mack smacked her lips.

"It's cold, this evening," she remarked. "And it smells dampish."

"That's the water," Rose told her. "The mistress told me that, in the old days, this was a farm, with a real water-spout. You may depend on it, the water is still hiding itself, somewhere. Water never goes."

She snapped her lips together and stood at attention, as Miss Asprey returned.

"Miss Mack," she asked, "did you empty my waste-paper basket, today?"

"Yes, Miss Asprey," replied Miss Mack, with conscious virtue. "I gave the bits to Ada, and she burned them with the other rubbish, in the garden incinerator."

Miss Asprey nodded without comment, and relapsed into silence. As the postman's knock sounded louder, Miss Mack took her courage in both hands.

"Miss Asprey, I wonder if I may have porridge for supper, please?"

Miss Asprey raised her brows in surprise, and waved her white hand over the salad.

"This is better for you. It supplies the Vitamin C which is necessary to your diet."

"Porridge is more filling, Miss Asprey."

"But you are getting too stout. Do you weigh, every morning, after your bath?"

Miss Mack blinked at the unexpected question. The bathroom was a primitive cell, and, as there was no gas on the premises, the hot-water supply was dependent on the kitchen fire, plus a defective system of pipes.

"Yes, Miss Asprey," said Miss Mack untruthfully, for she dared not confess that she bathed only on Saturday night, when the cook was out, so that she could stoke up the stove herself. "And, if you please, may I have porridge for my supper? It's quite cheap."

"If you really wish it, of course. And it's not a question of expense, but of your own good." Miss Asprey's voice was astringent, but her companion's china-blue eyes were serene.

'I'll ask for poached eggs, next,' she decided. 'And, after that, something that's really tasty.'

The postman's knock shook the house, and Rose stalked from the room. She returned, a minute later, with a letter on a pewter salver, which she offered to Miss Asprey.

Miss Mack was still dreaming of savoury pudding, made—perhaps—with blood, so that she was not watching Miss Asprey with her usual dog-like fidelity. But, at the sound of a sharply-drawn breath, she looked up, to see Miss Asprey staring at an open letter.

It was obvious that she was upset, for she waited to regain complete self-control before she spoke to the parlourmaid.

"Rose, go to the Rectory and tell the Rector I wish to see him immediately, please." Then she turned to Miss Mack with another request. "When the Rector comes, bring him to me, in the parlour, please."

Miss Mack obediently left her unfinished supper and waited in the dark porch, like a patient sentinel. When the Rector's huge figure loomed through the twilight, he was several paces in front of Rose, although that well-trained person was marching at the double.

As the Rector looked down into the perpetually smiling face of the little woman, she delivered her employer's message.

"Miss Asprey's expecting you in the parlour."

Like a cyclone, the Rector whirled into the living-room, which, like the dining-room, was panelled and dimly-lit. There were violet window-curtains, a few books and a bowl of white lilac—but not a single cushion, rug, or newspaper. Miss Asprey was seated on an oaken settle, with a high back; and, as he entered, the Rector received his impression of her as one whose heart had never been warmed at the fires of Life.

To his mind, she seemed to have withdrawn from grosser contact into the purity of her own soul. His surprise and shock was therefore the greater, when she spoke to him, without any greeting.

"I sent for you, Rector, because I have just received an anonymous letter. It is an attack on my moral character. Will you read it, please?"

He stared at her with incredulous horror, for once, at a loss for words.

"But—but—it's impossible," he said, at last.

Miss Asprey held out the letter, with fingers which trembled slightly.

"Read it," she repeated.

To his eternal credit—for he was consumed by curiosity—the Rector refused.

"No," he said. "You may wish me to read it tonight, but you'll probably think differently, tomorrow."

Miss Asprey shook her gleaming silver head.

"I've nothing to fear from tomorrow, and I fear no one," she told him. "But, after reading this, perhaps, I fear myself. It fills me with doubts—makes me wonder if I know my own heart—as it really is. If I were a Roman Catholic, I should unburden myself in the Confessional. As it is, I have no other course but to ask you to read this letter, and then—if you can—grant me Absolution."

"If that is really your wish, then I'll read it."

Having made his protest, the Rector picked up the letter briskly. It was printed, in block letters, on paper of excellent quality, and was correctly composed and spelt. It began with I the sentence—'You presumed to sit in judgment on unfortunate women whom you dragged out of the gutter, probably against their own wish, but are you, yourself better than the lowest of these?' It continued in the same strain, each line covered with the slime of insinuation, as though a slug had crawled over the pages.

The Rector exploded several times as he read it, and, at the end, he crushed it up angrily between his strong fingers and threw it on the floor.

"Foul," he declared. "Any anonymous letter is a knife in the back, but this one is specially outrageous...Can you tell me, Miss Asprey, if you have any—any suspicions as to the writer?"

"No," replied Miss Asprey. "Besides, the writer does not matter. I only want to know what you think of me."

True to his impulsive nature, the Rector acted without forethought. On this occasion, his muscles leaped to obey his instinct, before his mind creaked into motion, so that he was betrayed into a theatrical gesture. Stooping down, he kissed Miss Asprey's thin white hand, in silent homage.

Before he could feel ashamed, he was rewarded by the glitter of suppressed tears in her eyes.

"That's what I think," he told her. "But I also think that some evil-minded person is jealous of you."

As the door creaked slightly he looked up sharply, and then picked up the letter. Presently he glanced towards Miss Mack, who sat, watchfully, in the shadow of the wall, and pounced on her with a question.

"How do you spell 'judgment,' Miss Mack?"

As he had expected, she spelt it, 'judgement'.

"Exactly," he muttered. "Thank you." He turned to Miss Asprey. "This letter has been written by an educated person. Now, what, exactly, is your wish? Shall I try to trace it back to its source?"

"But can you do that? It is anonymous."

"I haven't the foggiest idea. But I have a friend—a chap with nothing to do, who's potty on puzzles. He'd enjoy getting his teeth into it."

Miss Asprey's answer was to replace the letter on the salver, and to apply a lighted match to one corner.

"That is what I'm going to do with the letter," she said. "My mind is now completely at rest again."

As she watched the paper blaze and then crumble into dust, her expression grew tranquil and the strain faded from her eyes.

But the Rector was suddenly rent with a vague foreboding of future evil. Acting on impulse, he picked up the envelope, which had begun to catch fire, and pinched out the charred patch.

"May I keep this?" he asked. "It may come in useful, supposing there's another letter."

Miss Asprey hesitated and then bowed her stately head.

"Certainly," she said. "But I am confident the matter is ended...Thank you for coming. Good night."

Miss Mack pattered across to the door, which she opened, to make the Rector understand that he was dismissed. He lingered, as he wondered whether he should try to repeat his success, and kiss the hand of the afflicted lady in farewell. But she seemed to have forgotten his existence, so he followed Miss Mack's hint, and left.

He carried away with him a memory of Miss Asprey's face glimmering whitely against the dark wood, as though she were already enshrined, and fading away to the bleak immortality of a saint.

He walked slowly back to the Rectory, in a depressed mood, and horrified at the mere idea that his perfect village sheltered a poisonous mind. But as he passed each person of the limited social circle in review, he was able to shake his head and brace his shoulders, as though he had shaken off a load.

No one he knew could have done this thing. To his mind, it was obvious that this letter had been written by some unbalanced person who had known Miss Asprey in the past, and who bore her a grudge. The fact that the envelope was stamped with the village post-mark was of small importance, as this subterfuge could be arranged.

When he entered his cheerful study, the whisky was on the table and the Wireless turned on. The essential parts of a fat spaniel—named 'Charles', after Dickens—were crowded on the doctor's lap, while the dog, from his intelligent look, was helping their guest to solve a chess-problem in the evening paper.

"Well?" asked Dr. Perry eagerly.

"Well," echoed the Rector, crossing to the table and juggling hospitably with the various bottles. "Soda or plain water, doctor? Say 'when'."

Dr. Perry bit his lip and pulled Charles' silky ears for moral support, before he repeated his question.

"Well? Was it so important?"

The Rector laughed as he hunted in a cupboard for the biscuit-barrel.

"It was nothing," he said. "She was just a bit upset. That's all."

"I see," said the doctor quietly. "That's all." He took his glass. "Thanks. Prosit."

The Rector felt sorry for his baffled curiosity, but he was guarding the secret of the Confessional. He turned to his dog, who was registering all the symptoms of acute starvation at the sight of the biscuits.

"Here you are, Charles," he said, tossing him a cracknel. "You're an overfed scoundrel, but you know your poor fish of a master can't resist a moist nose and swimmy eyes. But it's no good our friend the doctor looking pathetic, is it, Charles? We've nothing for him. By the way, doctor, please don't mention the fact that Miss Asprey sent over for me this evening."

"I quite understand." Dr. Perry laughed acidly. "You're giving me my own medicine—'Shall a doctor tell?'...My dear padre, not for worlds would I wish you to betray a confidence. There is no one I respect more than Miss Asprey, although there are many I like better. I am sorry she has suffered annoyance."

"How do you know she has?" asked the Rector.

"I don't, so, naturally, my mind is busy with every absurd impossibility...Well, I suppose I must go home and see if I still have the same wife."

Dr. Perry glanced at the clock, tossed off his whisky, and rose to go.

"Good-bye, padre," he said, patting Charles' head. "I admire you for your admirable policy of silence, and I bear you no ill-will."

The Rector's jaw dropped in surprise as the doctor added, "But I confess I should have liked your account of how the saintly Miss Asprey defended her honour."

WHEN Miss Asprey declared that the affair was ended she did not know that the parlourmaid was listening outside the door. Rose lingered in the hall, not only to satisfy her own curiosity, but to be forewarned of any annoyance which might threaten her mistress.

She possessed a testimonial from a Bishop's wife to prove her loyalty and discretion, and she did not repeat an actual word of what she overheard. But—like an unconscious germ-carrier—she liberated the poison in her system by gradual leakage. Somehow or other, she conveyed an impression to the cook, who transferred it to the beautiful Ada, in the form of a hint. Ada promptly elaborated this to a whisper, and then passed it on to the Squire's chauffeur.

Within twenty-four hours, through the Wireless of village communication, the rumour spread that Miss Asprey's moral character had been attacked in an anonymous letter from an evil-minded person, who was jealous of her.

Miss Corner was sitting cross-legged in her library, smoking and reading, when her cook-housekeeper told her about the letter. The novelist was on friendly terms with her staff, as she studied their comfort; in fact, it was rather a local grievance that their bathroom was far superior to Miss Asprey's.

The housekeeper's story fell rather flat, for Miss Corner was still bewitched by Edith Sitwell's Bath. She might sell cheap home-brew herself, with her insipid romances and absurd school-stories, but she could appreciate rare vintage—and her library-shelves testified to selective literary taste.

She puffed away grimly at her cigarette, as she mechanically listened to the tale, while the shrunken pupils of her eyes betrayed the fact that she was still marooned in the Eighteenth Century, and half-drunken from the savour of exquisite language.

'Russets, shalloons, rateens and salapeens.' The sentence swam through her brain, like an elusive gust of mignonette borne on a vanished summer breeze.

Her housekeeper—Mrs. Pike—became conscious that her story had fallen unaccountably flat, and began to apologise for it.

"Of course, madam, we don't know all that was in the letter. Depend on it, we've only been told the half."

"In every story," remarked Miss Corner, "there's the half we tell, and the half that others tell, and the half that's true. Add that up, Mrs. Pike, and see what it comes to."

Then, taking pity on the woman's bewilderment, she changed the subject.

"I'm throwing a little bun-fight this afternoon," she said. "You must provide a lavish tea, for the look of the thing, for it'll all be left. I'm expecting Mrs. Sheriff, Mrs. Scudamore, and Lady d'Arcy."

"Well, you'll have something to talk about, for a change," remarked Mrs. Pike, as she produced her housekeeping-tablet.

As a matter-of-fact, the incident of the anonymous letter only seemed to prove that the life-blood of the little community was too healthy to admit infection. It was received either with raised brows of polite incredulity, or with gusts of healing laughter. Yet, even at this early stage, certain events indicated that the village was not immune to poison, but only resistant.

Dr. Perry was motoring out to visit a country patient, when, at the cross-roads, he met Vivian Sheriff—the Squire's daughter—who was also driving a Baby Austin. They were not especially friendly, but their cars always insisted on stopping to fraternise with each other, so their owners had to make the best of it.

"I'm just cooling my engine," explained the doctor hastily. "We've been exceeding the speed-limit. How's your little car behaving?"

"Never better," boasted Vivian. "But my petrol's rather low." Then, as though dimly conscious that she was clutched in the grip of machinery, and had to await its Robot pleasure, she began to gossip.

"Heard about Miss Asprey's anonymous letter?" she asked.

The doctor had not heard; but, as he listened to Vivian, his eyes gleamed with interest, which gave way to resentment. This, then, was the origin of the Rector's secret mission. He, himself, had been present at the birth of an intriguing human development, and had been shut out in the cold.

But the Rector, apparently, had lost no time in spreading the story. In the doctor's eyes his admirable policy of silence was now revealed as pure pose.

'The fellow's nothing but a human gramophone,' he thought contemptuously, as the cars grew suddenly tired of each other and agreed to start.

An hour later, when Dr. Perry met the Rector trudging along the road with his fishing-tackle his greeting was rather cool. He still felt slightly disgusted, while the Rector was horrified by his own unworthy suspicion, as Dr. Perry's parting remark kept stirring in his mind. How did the doctor know that the letter attacked Miss Asprey's moral character?

Both men talked of fly-fishing, but did not refer to the letter. The doctor offered the Rector a lift, which was refused. A little of the poison had spread.

The subject was also raised at the Hall, where Lady d'Arcy was having lunch with the Squire's family. Mrs. Sheriff, who was a youthful, flaxen-haired little person—rather gummy, but with a sweet and self-sacrificing disposition—was human enough to be mildly excited.

"I wonder who wrote it," she exclaimed, with school-girlish interest.

Her husband pulled down his lip, and the vague Lady d'Arcy drifted up to the occasion, for the Rector had made no idle boast that the village was almost free from the vice of scandal.

"Not one of us," said Lady d'Arcy, in her lightest voice and changed the subject.

Her speech sounded above reproach, but the Squire frowned, pulled his lip again, and grew thoughtful. The village accepted no one who had not been a resident for fifteen years. Companions and governesses did not count, of course, while Mrs. Perry crept in under her husband's wing.

There remained only the Martins—the rich absentee owners of the Towers—and the local novelist.

Miss Julia Corner had entirely returned from Bath, and was her usual genial self when she acted as hostess at her tea-party. She wore a white muslin peasant blouse, with juvenile short sleeves and a round neck. A string of corals encircled her fat neck and her grey fringe was freshly-cut. She flourished her tea-pot dangerously as she beamed upon her guests, who were of the younger generation.

Owing to some curious run of bad-luck, both the Squire's wife and Lady d'Arcy had sent deputies. Kind little Mrs. Sheriff—when she pleaded a racking headache—had rebelled against her husband, and insisted that Vivian should take her place. The vague Lady d'Arcy, who was sufficiently practical to make use of others—merely told Joan to offer her apologies.

Joan's inventive powers proved equal to the strain, and she was only too glad to stay, for, although she had acquired a certain respect for Art, in Chelsea, she was a backslider where Miss Corner's comfortable home was concerned.

It had its own electric-plant, so that the novelist was able to indulge her passion for brilliant lighting, and it possessed a perfect system of central-heating. In spite of the scraps of Fourteenth-century barns which composed its outer walls, its interior was entirely modern, with built-in drawers and cupboards, amusing metal furniture, aluminium-sprayed rubber curtains and planet-lamps. In the place of pictures, there were numerous mirrors.

"I like to see a lot of Julias," explained Miss Corner. "Those fat girls are my company. You've heard, haven't you, how a fat girl can love, even if no one loves her?"

Vivian's smile was polite and non-committal, for she was not feeling entirely at her ease. She was a pretty girl—fair-haired and turquoise-eyed—with exquisite colouring. Like most of the local ladies, she had the delicate air of one reared entirely under glass, so that, in comparison with her, Joan looked like a rosy apple placed beside a hot-house peach.

They appeared to be the same age, although, in reality Vivian possessed only the sterilised youth of the village.

She raised her gossamer brows when Joan began to talk about the anonymous letter.

"What do you think about it, Miss Corner?" she asked.

"Thrilled," replied the novelist. "It's been said that the anonymous letter-writer is the only really interesting criminal."

"I think it's disgusting," said Vivian. "And to send it to Miss Asprey—of all people."

"Why should she be exempt?" demanded Miss Corner. "She's not sacred, is she?"

"No. But she's so—so spiritual. I've rather a passion for her. I think she must have an aura—a blue or violet one. Anyway, I'm sure she's an influence for good. Whenever I am at 'The Spout', I'm conscious of being in a state of perfect peace."

As it was difficult to connect Vivian with any emotion, neither Joan or Miss Corner were impressed.

"You're lucky," declared the novelist. "I wish I could say the same. She always seems to drain my brain dry of ideas, and she makes me feel like a wet rag. In fact, when I'm in process of literary gestation I don't dare go near her barn."

"Barn?" echoed Vivian reproachfully. "Miss Asprey's house and furniture are perfect Tudor period."

"Yes, and I don't sit down in the Sixteenth Century. It's true that Nature has thoughtfully provided me with padding—but it's not fair to count on guests bringing their own cushions...But Miss Brook has nothing to eat."

Miss Corner broke off to offer Joan a selection of cakes.

"Those flaky things are dee-licious," she said, "but they're not safe to be let loose without a plate. They're the underhand kind that spit cream in your eye. Here you are, my dear—plate and nappy. I'm not one of your Society sadists, who tempt pure young girls to eat oranges in public...Hum. Mrs. Scudamore's late."

The novelist glanced at the clock and poured herself another cup of tea, while her eyes grew speculative, with pin-prick pupils.

"Let's get back to Miss Asprey," she said. "Have you noticed that though she looks as if a puff of air would blow her away, she's unusually strong. And her brain still bites like a badger...Sometimes, I wonder if she draws her reserves from others, now that she's growing old. When I first came here I wasn't conscious of being affected by her, and it's odd the way her powers don't seem to fail with age. You know, my dears, there are people who sap your vitality."

"You mean—human vampires?" Vivian's flower-like face grew pink. "But that's a terrible thing to say of Miss Asprey."

Joan hastened to change the subject.

"I wonder you don't keep a pet, Miss Corner," she said. "Cats and dogs are better company than looking-glasses."

"I'd love to," replied the novelist wistfully. "But—I'm alone."

"That's what I meant."

"And that's what I meant, too. If anything happened to me, what about them? I'm too fond of animals to risk them."

Joan missed the hint of tragedy which clouded the novelist's eyes, for she was looking at the inch of Oxford-blue ribbon on Miss Corner's broad white chest.

"Is that your Temperance badge?" she asked.

"Yes," replied the novelist. "That is to show I drink nothing—in public."

Joan laughed with her hostess, because she remembered her friend's ridiculous serial.

"I think Miss Asprey's letter is nothing but a silly practical joke," she declared. "And if the joker follows it with a second, you will, probably, be accused of being a secret drinker."

"But I am," grinned Miss Corner. "Only, no one in the village possesses any sense of humour, except the doctor."

"Dr. Perry?" cried Vivian incredulously. "He's always so quiet."

"Exactly. Beware the dog that doesn't bark. Did you know he has a secret passion for me? There is someone who loves a fat girl...This is our guilty signal."

She picked up an empty black-and-gilt tea-cup, and, crossing to one of the small windows, balanced it on top of the open casement.

With the insolence of youth, Joan thought she was rather pathetic. And the novelist, from her safe vantage of experience, pitied Joan. 'No beauty, no money, no talent,' she reflected. 'If she grabs the parson, her market's made. If she doesn't, Heaven help her.'

She looked up with her usual beam of welcome, as her loyal, stupid maid—May—announced Mrs. Scudamore.

The important lady made her usual gracious entrance and created her special impression. She was wearing a last year's gown and coatee, of grey lace, and appeared, definitely, a middle-aged English-woman, of the type that is accepted as representative, on the Continent.

Her good features were just a shade too large; she displayed too much hair, and not enough style.

But everyone paid instinctive homage to the Spirit of the Village. Joan, who was lounging back in her chair, with outstretched feet, drew herself upright. Vivian looked relieved, as though welcoming moral support, while Miss Corner whispered to May, 'Fresh tea-pot.'

Mrs. Scudamore was very gracious to everyone. Presently, when she was sipping tea and subduing one of the treacherous cakes—after having declined a plate—she spoke, smilingly, to Joan.

"What were you laughing about when I came in? You sounded very merry."

"I expect we were talking about Miss Asprey's anonymous letter," replied Joan.

"An anonymous letter? Here?...Oh dear."

Mrs. Scudamore gave a faint scream. She—the exponent of perfect manners—had committed the unpardonable breach of spilling her tea. It was a complete catastrophe, for she dropped both the cup and saucer, smashing the china and drenching the beautiful gold-and-blue Persian carpet.

Miss Corner was entirely kind, and hid her natural feelings under a cover of good-natured laughter. Presently, when the mopping operations were over, Mrs. Scudamore recovered her poise and asked for further details about Miss Asprey's letter.

"How very unpleasant," she remarked. "It betrays an odious mind. But it is really too absurd. A charge of immorality against Miss Asprey—of all people. And at her age."

"Age has nothing to do with it," shouted Miss Corner. "I'm fifty-five, and I'd do anything for the sake of literary experience."

Joan saw the swift, involuntary glance which flashed between Mrs. Scudamore and Vivian.

'I wish you hadn't said that,' she thought.

Unaware of any need of caution, Miss Corner went from bad to worse.

"I simply can't understand all this silly worship of Miss Asprey," she said. "You see, I went to school with her. Of course, I was much younger, for she's sixty-four. But, even then, I was a little novelist, only my books were more mature than The Young Visitor. Decima was one of the big girls, with long, fair pigtails—but I took her measure, all right."

"Fair plaits. She must have looked like Marguerite," murmured Vivian.

"Marguerite, without the guts to go to hell. And I don't see she's made a success of her life. She chucked her job when she was still a young woman. After all, I've stuck to mine."

Annoyed by the lack of response from her guests—for even Joan looked thoughtful—Miss Corner began to brag.

"Perhaps I'm too proud about my work, but I've given—and I still give—a lot of happiness. All she did was to drag miserable girls into her Hostels, cram them with thick bread-and-butter, and set them to scrub floors and sing hymns."

She flashed her glasses aggressively at her guests.

"I don't suppose anyone has any notion of my huge fan-mail," she boasted. "Little boys—I love boys—write to me, begging for another of Joey's adventures. 'Dearest Miss Corner, I can hardly bear to wait for the next instalment. You don't know how thrilled I am by naughty Sam.' Or, 'Please, please, dear Miss Corner, tell me some more about Jimmy. I just adore him.' That's my reward, and please Heaven, I'll die in harness."

Joan thought that the letters sounded more like the effusions of little girls, and felt guilty of disloyalty, when—at the hoot of a motor-horn—Miss Corner gave her a conspiratorial wink. Unabashed by Mrs. Scudamore's surprised expression, she crossed to the window and removed the signal.

Two minutes later, when Dr. Perry entered the room, his hostess received him with a brimming cup.

"Here's your rotten weak China," she said. "Never mind. If I'm spared, I'll yet turn you into a strong Indian."

The doctor looked intently at Miss Corner, before he seated himself beside Joan, to the girl's secret satisfaction. Although she had chosen the Rector for her own, she considered Dr. Perry the most interesting man in the village. While there seemed nothing special in him to understand, she was aware that she did not understand him.

"We've been talking about it," she whispered.

"It?" He laughed slightly. "Oh, you mean the famous, or rather—infamous—letter...Who told you about it?"

"The padre."

"The padre, of course. The professional custodian of secrets. Ridiculous, isn't it?"

Joan noticed that he was only giving her a corner of his attention, for his eyes still lingered on Miss Corner. It was plain, from her understanding smile, that he was on terms of intimacy with the novelist. While Joan was sufficiently experienced to know that the laws of attraction are inexplicable, Miss Corner's grinning red face reminded her so strongly of the Leg of Mutton, in Alice Through the Looking-Glass, that she discarded the possibility of a romantic attachment for an uglier motive.

'Miss Corner's a rich spinster,' she thought. 'Suppose he is ingratiating himself with her, to get her to leave him her money. Mercy. I'm as bad as old Purley.'

But she knew that her friend would carry her lurid speculations a stage further, and she shuddered as her imagination suddenly shied at a gruesome reflection.

'A gentle smiling poisoner.'

She wrenched the idea from her mind.

'I'm a horror,' she thought contritely. 'It's Purley's fault. She started it, and now suspicion seems in the air.'

Restored to commonsense, she listened to Mrs. Scudamore, whose large, mild eyes were like searchlights, picking out the faces of her social disciples in order to secure their attention.

"Of course," she hinted gently, "I shall not allude to the letter when I next meet Miss Asprey. My silence will assure her of my entire sympathy. But I should only insult her if I let her think that I'd given even a minute's thought to such a wicked and ridiculous slander."

Her reassuring smile was the unspoken rider to her little speech. 'Now, you all know how to behave.'

"Yes." Vivian's fair face flushed, and she spoke too quickly. "Shall we all promise, that, whatever we may hear about each other, we won't believe it?"

At the unguarded request, everyone stared at her, aghast, for her words seemed to hint at the actual existence of secret swamps. In the silence that followed a dark flicker shook through the room.

It was the first warning of the approach of Fear.

THE next day was sultry, with blazing sunshine and a cloudless sky. Hot weather always filled Joan with extra energy, so that after she had safely settled Lady d'Arcy for the afternoon, she determined to walk to the top of the Downs, to get a breeze.

When she came out of the tenebrous Quakers' Walk, the thatched cottages of the village looked like golden bee-hives, and the old pump seemed to nod in the drowsy heat. Everyone seemed to be under the spell of the Sleeping Beauty, for Joan met no one in the cobbled street.