RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

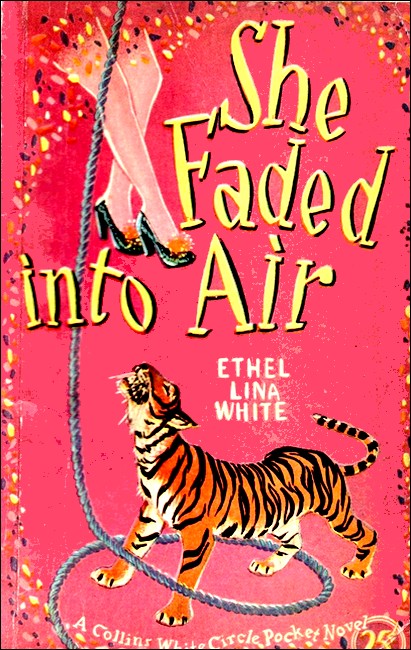

"She Faded Into Air," Collins Crime Club, London, 1941

"She Faded Into Air," Harper Brothers, New York, 1941

THE story of the alleged disappearance of Evelyn Cross was too fantastic for credence. According to the available evidence, she melted into thin air shortly after four o'clock on a foggy afternoon in late October. One minute, she was visible in the flesh—a fashionable blonde, nineteen years of age and weighing about eight and a half stone.

The next minute, she was gone.

The scene of this incredible fade-out was an eighteenth-century mansion in Mayfair. The Square was formerly a residential area of fashion and dignity. It had escaped a doom of complete reconstruction, but some of the houses were divided up into high-class offices and flats.

This particular residence had been renamed "Pomerania House" by its owner, Major Pomeroy. He speculated in building property and had his estate office, as well as his private flat, on the premises.

The ex-officer might be described as a business gentleman. Besides being correctly documented—Winchester, Oxford and the essential clubs—he had not blotted his financial or moral credit. In appearance he conformed to military type, being erect, spare and well dressed, with a small dark tooth-brush moustache. His voice was brisk and his eyes keen. He walked with a nonchalant manner. He had two affectations—a monocle and a fresh flower daily in his buttonhole.

Shortly after four o'clock on the afternoon of Evelyn Cross' alleged disappearance, he was in the hall of Pomerania House, leaning against the door of his flat, when a large car stopped in the road outside. The porter recognized it as belonging to a prospective client who had called previously at the estate office to inquire about office accommodation. With the recollection of a generous tip, he hurried outside to open the door.

Before he could reach it, Raphael Cross had sprung out and was standing on the pavement. He was a striking figure, with the muscular development of a pugilist and a face expressive of a powerful personality. Its ruthless force—combined with very fair curling hair and ice-blue eyes—made him resemble a conception of some old Nordic god, although the comparison flattered him in view of his heavy chin and bull-neck.

He crashed an entrance into the hall, but his daughter, Evelyn, lingered to take a cigarette from her case. She was very young, with a streamlined figure, shoulder-length blonde hair and a round small-featured face. With a total lack of convention she chatted freely to the porter as he struck a match to light her cigarette.

"Confidentiality, we shouldn't have brought our dumb-bell of a chauffeur over from the States. He's put us on the spot with a traffic cop."

"Can't get used to our rule of the road," suggested the porter who instinctively sided with Labour.

"It is a cockeyed rule to keep to the left," admitted Evelyn. "We took a terrible bump in one jam. I'm sure I heard our number plate rattle. You might inspect the damage."

To humour her, the porter strolled to the rear of the car and made a pretence of examining the casualty before he beckoned the chauffeur to the rescue. When he returned to the hall, the major had already met his visitors and was escorting them up the stairs.

The porter gazed speculatively after them, watching the drifting smoke of the girl's cigarette and the silver-gold blur of her hair in the dusk. The skirt of her tight black suit was unusually short so that he had an unrestricted view of her shapely legs and of perilously high-heeled shoes.

As he stood there, he was joined by an attractive young lady with ginger hair and a discriminating eye. Her official title was "Miss Simpson," but she was generally known in the building by her adopted name of "Marlene." She was nominally private secretary to a company promoter who had his office on the second floor; but as the post was a sinecure she spent much of her time in the ladies' cloakroom on the ground floor, improving her appearance for conquest.

"Admiring the golden calf?" she asked, appraising the quality of the silken legs herself before they disappeared around the bend of the staircase.

"She's got nothing on you there, Marlene," declared the porter.

He had a daughter who was a student at a commercial school and was biased in favour of typists.

"Except her stockings, Daddy. Where's the boss taking them?"

"I was asking myself that. The gent's a party after an office. There's only a small let vacant, right at the top and that's not in his class."

"Maybe the girl's going to Goya to get her fortune told," suggested the ornamental typist, tapping her teeth to suppress a yawn.

For nearly ten minutes she lingered at the foot of the stairs, chatting to the porter and on the outlook to intercept any drifting male. The place, however, was practically deserted, so presently she mounted the flight on her way back to her office. She paused when she reached the landing of the first floor, where there were three mahogany doors in line, each embellished with a chromium numeral.

Just outside the middle door—No. 16—the major stood talking to Raphael Cross. Impressed by the striking appearance of the fair stranger, she patted the wave of her ginger hair and lingered in the hope of making a fresh contact.

Consequently she became a witness to the beginning of the amazing drama which was later entered in Alan Foam's case book as "Disappearance of Evelyn Cross."

Although she was friendly with the major, on this occasion he was neither responsive nor helpful. He merely returned her smile mechanically. Only a keen observer might have noticed a flicker of satisfaction in his hawk-like eye, as though he had been expecting her.

Then he started the show, like the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, by pulling out his watch.

"Your daughter's keeping you a dickens of a time," he remarked to Cross. "I thought she said she'd be only a minute. You're a patient man."

"Used to it." Cross grimaced in continental fashion. "I'll give her a ring."

He prodded the electric bell of No. 16 with a powerful forefinger. After a short interval it was opened by the tenant of the apartment—Madame Goya.

She was stout, shortish and middle-aged. Her blued-white permanently waved hair did not harmonize with an incongruous dusky make-up and orange lipstick. Her eyes were dark, treacly and protruding, in spite of being set in deep pouches. She wore an expensive black gown which flattered her figure and a beautiful emerald ring.

"Will you tell my daughter I'm ready to go,' said Cross.

"Pardon?" asked the woman aggressively. "Your daughter?"

When Cross amplified his request, she shook her head.

"Miss Cross was here only to make an appointment. She left some time ago."

"Left?" echoed Cross. "Which way?"

"Through this door, of course."

He stared at her as though bewildered.

"But the major and I have been standing outside," he said, "and I'll swear she never came out."

"Definitely not," agreed Major Pomeroy. "Are you sure she's not still inside, madame?"

"If you don't believe me, come in and see for yourself," invited Madame Goya.

Throbbing with curiosity, the ornamental typist crept to the closed door of No. 16, after the men had gone inside. She heard voices raised in angry excitement and the sound of furniture being bumped about. Presently the major came out alone. His face wore a dazed expression as he took hold of her elbow.

"You've just come upstairs. Beautiful, haven't you?" he asked. "I suppose you did not notice a blonde in black coming down?"

"No," she replied. "I didn't meet a pink elephant either. It's not my day for seeing things. What's all the blinking mystery?"

"Hanged if I know," said the major helplessly. "Boss out, isn't he? Be a good girl and nip round to every office and flat in the place. Ask if anyone's seen her. They haven't. I know that. But I've got to satisfy her father."

The ornamental typist made no objection to being useful, for a change. She spun out her inquiries to a series of social calls throughout Pomerania House. True to the major's forecast, no one had seen a loose blonde, so presently she returned to the first floor.

Raphael Cross, the fair stranger who had attracted her fancy, had come out of No. 16 and was pacing the landing as though on the verge of distraction. Her first glance at him told her that it was no time for overtures. His features were locked in rigid lines and his eyes looked both fierce and baffled. He glared after the figure of the porter as the man returned to his station in the hall. The major spoke to him in a low voice.

"You heard what the fellow said. I've known him for years before I employed him. He's definitely reliable."

"The hell he is," growled Cross. "Someone's lying. Where's my girl?"

"Oh, we'll find her. I admit it's an extraordinary affair. Almost uncanny. I'm at a loss to account for it, myself. But you may be sure there's some simple explanation."

"I know that. This is a put-up job. There's someone behind all of this. It's an infernal conspiracy."

Major Pomeroy stiffened perceptibly, while the sympathy died from his eyes.

"Who do you suspect?' he asked coldly.

"I'll tell you when I've got my girl back. I don't leave this ruddy place without her. Order that porter to see to it that no one goes out of this building until there's been a systematic search through."

"Certainly... Shall I ring up the police?"

The question checked Cross' hysteria like a snowball thrown in his face. He hesitated and gnawed his lip for some seconds before he made his decision.

"No, Pomeroy." His voice was low. "This may be kidnapping. If it is, the police are best kept out."

The major's hostility melted instantly.

"I understand," he said in a feeling voice. "Come down to my office and I'll ring up a reliable private detective agency."

Halfway down the stairs, he returned to caution Marlene.

"Keep your eyes open and your mouth shut—there's a good girl."

"Cross my heart."

Within two minutes after the men had entered the major's office, she was telling the whole story to the tenant of the flatlet, No, 15. This lady—according to her visiting card inserted in the slot of the door—was named "Viola Green," while her occupation was supposed to be that of a mannequin.

She limped out onto the landing, her hands in her pockets and a cigarette between her lips; yet, in spite of her pose of nonchalance, there was no hint of stereotyped boredom in her face. Her expression in its vivid expectancy was a challenge to the future, as though she claimed the maximum from life and refused to admit to compromise.

She was distinctly attractive, although both face and figure were somewhat too thin. Her short black hair had bright brown gleams and her eyes were hazel-green. She wore black slacks, a purple-blue pullover and rubbed silver sandals.

Although the majority of males in Pomerania House were on friendly terms with Marlene Simpson, the women avoided speaking to her. Viola Green was the exception. She was not only unhampered by snobbery or moral criticism, but she was responsive to a psychic bond between them.

Both girls were held in allegiance to the lure of the profession. Viola had studied at an academy of dramatic art, while Marlene had toured the provinces as a glamour girl in a cheap revue. Total lack of success had forced them into uncongenial jobs, but their thwarted instincts drew them together to discuss the stars of stage and screen with passionate interest.

On this occasion, Viola only wanted to hear the scenario of the drama on the first-floor landing.

"So what?" she asked, with an economy of language familiar to Marlene.

She listened to the story with wide-eyed open-mouthed interest, but at its end she made the requisite ribald comment.

"Well, I've heard of people wanting to reduce quickly, but that's overdoing it... Was she kidnapped?"

"That's what it looks like to me," replied the ornamental typist. "I saw her go up and I was mucking about in the hall all the time afterwards. But she never came down, unless she's the Invisible Man."

"What's your guess?" asked Viola.

"I believe Goya stunned and gagged her. She'd about ten minutes to play with. Then she hid her in a cubby-hole behind the panelling. There might be one behind the mirror or at the back of the clothes closet. But the blonde's father swears he won't go until she is found, so he'll soon scoop her out... Oh boy, you should see father—hundred per cent Aryan and like an earthquake. He's got that look in his eye that tells you he knows all the answers."

Viola, who was growing bored, distracted her attention.

"Your telephone's been ringing for ages," she said.

"Yes, I heard it," commented Marlene. "Sounds quite profane. I seem to recognize my master's voice. Perhaps I'd better listen to his little trouble. See you later. Bye-bye."

She mounted the stairs in a leisurely fashion while Viola stood and gazed down into the hall. About this time, when dusk blurred its modern improvements, the old mansion had power to fascinate her. She did not recall the patched and powdered ghosts of Berkeley Square but only the lately receded tide of the last century, as she thought of the families who had lived private lives within those walls.

In those spacious days, the offices had been double drawing rooms where parties were held. Girls in white tulle frocks had sat on the stairs and flirted with their partners behind feather fans. Children had peeped down enviously from between the banisters.

But now the clocks were stopped and the music stilled. Sighing at the thought, she limped across to the tall windows at the end of the landing. Outside, the Square Garden was spectral with misted shadows and tremulous with tattered leaves shaking from the plane trees. In the distance a sports car hooted through the darkness.

It was driven by Alan Foam, who was on his way to investigate the alleged disappearance of Evelyn Cross.

Viola was still gripped by the story, although her common sense rejected it as nonsense. At that time she was yearning after her old gods and suffering from histrionic starvation. Unable to resist the chance of dramatizing herself, she stretched out her hands and groped in the air. "Lost girl," she whispered. "Where are you?"

As she waited, the lights were turned on throughout the building. She heard the faint tapping of typewriters and the distant ringing of telephone bells. The atmosphere of Pomerania House was entirely normal—commercial and financial.

There was no warning wave from the future to tell her that this was a prelude to a moment charged with horror, when she would cry out in anguish to someone who was not there and get no answer from the empty air.

WHEN Alan Foam was asked why he had become a private detective he explained that he liked solving riddles and wanted an occupation which would take him out-of-doors. His original ambition had been the secret service, but circumstances forced him to accept his father's compromise of a share in the firm of Girdlestone & Gribble.

On the whole he was disappointed with the work. Instead of adventures, his main activities were protecting people from blackmail and aiding them to procure divorce. In the course of a few years he became tough and cynical, with no illusions as to the fragrance of hotel bedrooms and with a conviction that the human species had evolved the most deadly type of blood-sucking parasite.

At times when his mind rebelled against its storage of gross details, he considered the antidote suggested by his mother.

"Why don't you marry, Alan?"

"Waiting for the right girl," he told her. 'I've checked too many hotel registers."

"Well, hurry up and find her." She added inconsequently, "You used to be such a dear little boy." There were times, however, when he was keenly interested in his work, especially when his enterprise had been recognized by his superiors. It was after one of these rare occasions that he leaped to the telephone and tried to disentangle the statement from Major Pomeroy's secretary.

It appeared so unlike the routine case of disappearance that he was afraid it was too good to be true.

"You say she's gone—but she never left the building?" he queried.

"Well, it sounded like that when they were both shouting at me," replied the girl doubtfully. "But it doesn't make sense. I suppose I got it wrong."

"Never mind. I'm on my way."

As Foam scorched through the dun shadows of the Square, he was struck by its derelict appearance. It seemed darkened by a pall of antiquity and decay. The old houses might have been barnacled hulks of vessels stranded in a dry-dock by the receded tide of fashion.

When he approached Pomerania House, it suddenly glowed with lighted windows. A large and powerful car was parked outside, while the porter stood on the pavement, fraternally scanning the stop press in the chauffeur's paper.

Following his custom, Foam looked keenly at both men. The chauffeur was a clumsy Hercules, showing a section of standardized glum face below his goggles. The porter appealed more to Foam as a type of labour. He was elderly, with a square, sensible face and steady blue eyes.

He did not return Foam's approval, for he looked at him sourly. The detective understood the reason for his instinctive antipathy. He knew that he was regarded as a by-product of the police force and consequently to be avoided like a mild form of plague.

The porter stiffened as he spoke to the chauffeur in his official voice.

"Your guv'nor says not to wait for him. He may be kept here till midnight."

"Am I to come back and fetch Miss Evelyn?" asked the chauffeur.

His voice was tinctured with curiosity, but the porter was not to be drawn.

"I've given you the message," he said. After the car had driven on, he spoke to Foam. "From the agency? You're expected. This way." Foam followed him through the lobby and into the hall of Pomerania House. As he looked around him he had partly the sensation of being in a museum. Its proportions were fine, although some of its space had been encroached on by offices. Most of the panelling on the walls had been preserved and also a large oval portrait in a tarnished gilt frame, which hung over the original carved mantelpiece. This was a painting of a former owner of the house by Sir Joshua Reynolds and depicted a Georgian buck with full ripe cheeks and a powdered wig.

The old crystal chandelier—long disused—was still suspended from the ceiling. The statue of a nymph, posed on a pedestal, gazed reproachfully at all who used the telephone booth, as though it were the bathing hut where she had left her clothes and to which they denied her re-entry.

He with these relics of the eighteenth century, the flagged marble floor, as well as the shallow treads of the curving mahogany staircase, was covered with the thick rubber flooring of commerce. The radiators were not concealed and the panel lighting was modern, to correspond with the low painted doors leading to the reconstructed portions. The porter jerked his thumb towards the staircase.

"Up there," he said. "First floor. I can't take you up. My orders are not to leave this door."

"No lift?" asked Foam.

"No. The boss did as little conversion as possible... One never knows."

Foam nodded to show he understood the threat—the shadowy pick of the house breaker swinging over the old mansion. He hurried across the hall and ran up the stairs, covering three steps in each stride.

Three persons—two men and a stout woman—stood on the first landing, while a ginger-haired girl loitered on the flight of stairs leading up to the next floor. Foam recognized Major Pomeroy, whom he knew by sight, but in any case it would have been easy to pick out the father of the missing girl. Cross was plainly gripped by violent emotion, for his large hands were clenched and his jaws set in an effort to control his facial muscles.

The major came forward to meet him and introduce him to his client; but Foam cut out the preliminaries. Ignoring the others, he telescoped the incoherent explanations he had received over the telephone into a concise statement as he spoke to Cross.

"Your daughter has disappeared and there is no time to lose. Give me the facts."

Braced by the curt voice, Cross recovered his self-control.

"We came here together just about four," he said. "My daughter went into that room." He nodded towards No. 16. "She never came out."

"Then she must be inside still," said Foam.

"No. She has disappeared."

Foam stared at him, wondering whether he were knave or fool. He might be the instigator of some cunning trick—as yet unidentified—or himself the victim of a confidence trick.

"Who is the tenant of No, 16?" he asked.

"I am," declared the stout woman, surging forward. "I am Goya. Madame came to see me about placing an order for hand-made gloves."

Although he was repulsed by her huge painted frog-mouth, her meretricious appearance, Foam spoke pleasantly.

"Let me have your story, please."

"It's a pleasure," said Goya grandly. "Madame stood just inside the door. I looked up and asked, 'Appointment?' You must understand my time is too valuable to waste on chance callers. She shook her head, so I said, 'Kindly write for one. Good afternoon.' She left at once. In fact, she was in and out again without opening and shutting the door a second time."

Foam turned to Cross.

"While you were waiting, I suppose you and the major were talking? Can you remember what it was about?"

Cross looked blankly at the major who answered for him. "We started by discussing business—I was trying to interest Mr. Cross in some office accommodation, but he was unable to make an immediate decision. So we began to argue about Danzig."

"Then I suggest that you were too engrossed to notice when your daughter slipped past you—especially as you were not expecting her to come out so soon."

"No, it's a pack of lies," declared Cross. "The major and I stood here, facing the door. It was shut. We can both of us swear she never came out."

"I'm afraid it's not so simple as that," agreed the major. "The porter was in the hall and he states positively that she never came downstairs or left the building. One of the typists was there with him—and her story is the same as his... Miss Simpson. Would you mind coming down for a minute?"

The ginger-haired girl came down the stairs with the assurance of an ex-"Lovely". Rolling her eyes at Cross, she smiled at Foam.

"The major's got one of his facts wrong," she said. "I'm a private secretary—not a typist. But I'll sign on the dotted line for the rest."

"That brings us back to No. 16," admitted Foam. "Is there any other way out of it? No door of communication between it and one of the adjoining rooms?"

"Definitely not," declared the major.

Foam glanced at the doors to the right and left of No. 16. "Who rent these?" he asked.

"Two girls on their own," replied Major Pomeroy. "Miss Power is in No. 57 and Miss Green in No. 15. Neither of them saw Miss Cross. We have also inquired at all the flats and offices in the building. Every effort has been made to find her."

Foam continued to gaze reflectively at the doors. "I suppose you have the customary references with your tenants?" he asked, as he considered the dubious personality of Madame Goya.

"I do not," replied the major. "To my mind, that rule penalizes strangers. I prefer a gentleman's agreement. I can trust to my judgment to size up anyone. Besides an unsatisfactory tenant gets spot-notice."

He laughed as he added, "I've discovered that references are not infallible. For instance, I don't know a thing about Miss Power except that she is a student. But she's an ideal tenant—quiet and regular with her payments. On the other hand, Miss Green is a bishop's granddaughter and she's a little scamp."

"Quite. I'll have a look at No. 16. But I want a word with the porter first."

Feeling a need to clarify the situation, Foam hurried downstairs. He was not satisfied by what he had already heard. Although three persons had given him the same facts, he could not ignore the factor of mass suggestion. But he instinctively trusted the porter, who reminded him of a gardener he had known in boyhood.

When he reached the hall, the man was at his post, watching the door.

"What's your name?' asked Foam.

"Higgins," replied the porter.

"Well, Higgins, can you be sure that it was Mr. Cross' daughter that you saw go upstairs? The lights were not turned on."

"I saw her face when I lit her fag," replied the porter positively. "She came here once before with her father, so I knew her by sight."

"Did you actually see her go into No. 16?"

"No. You can't see the landing from the hall because of the bend of the stairs. But I saw the three of them go up, and so did Marlene Simpson."

"Is there a back entrance to Pomerania House?"

"Yes, the door's over there. But she'd have to come down the stairs and cross the hall to reach it—and she didn't. It's a blinking mystery to me."

Foam was on the point of turning away when he asked another question on impulse.

"Higgins, you see a good many people. In confidence, can you place Mr. Cross?"

"I'd say he was a gentleman," replied the porter. "Not Haw-haw, like the boss, but a bit colonial."

"And Miss Cross?"

"Ah, there you have me. I know a lady and I know a tart; but when they try to behave like each other, I get flummoxed."

"You mean—Miss Cross was lively?"

"That's right."

"Thanks, Higgins. That's all."

Foam was on the point of going upstairs when he stopped to peep through the open door of an office which had Major Pomeroy's name painted on the frosted glass panels. A little girl with a pale, intelligent face and large horn-rimmed glasses stopped typing and looked up at him expectantly.

"I'm from the agency," he explained. "Do you happen to know Mr. Cross' private telephone number?"

He blessed her for her instant grasp of his meaning.

"That's been attended to," she said. "The major told me to ring up the apartment hotel where Mr. Cross is staying before I got on to you. They had no news of her, but the major said it was too soon."

"Nice work," approved Foam. "Keep ringing the number."

Running upstairs to the landing where Cross and the major were still waiting, he opened the door of No. 16.

It was a typical example of the architecture of its period—large and lofty, with an ornate ceiling and cornice decorated with plaster mouldings of birds, flowers and fruit. The walls were panelled with cream-painted-wood, much of which was hidden by fixtures—a cupboard wardrobe, a tall erection of book shelves and a full-length mirror in a tarnished gilt frame. A huge oil painting of a classical subject—a goddess supported by super-clouds and surrounded by a covey of cupids—took up much space.

It was furnished in modern style, with a conventional suite of a divan and two large easy chairs which might have come from any window of a furnishing store. The colouring of the upholstery was neutral and toned with the buff Axminster carpet. Madame Goya's personal taste was indicated by cushions of scarlet and peacock blue and by a couple of sheepskin rugs dyed in distinctive tints of jade and orange. The open grate had also been modernised with built-in tiles and an electric fire.

Such was No. 16—the room in which, according to the inference of the evidence, a girl had faded into air.

FOAM did not need the aid of Euclid to reject the vanishing theory as absurd. If the girl were actually lost inside Pomerania House, it stood to reason that she must be still there—in the flesh. It seemed to him that the mystery admitted one of two explanations.

The first was that Evelyn Cross had slipped away voluntarily out of the house. Unfortunately, the chances of this were remote, since it involved choosing the identical blind moment of four witnesses, all endowed with normal senses.

The second was that she had been kidnapped—in which case Goya must be the agent. This, too, was not a watertight theory. Apart from the necessity of co-operation with another person—or persons—in Pomerania House, Goya would have to devise as ingenious and foolproof hiding place for her victim, in view of the inevitable search of her premises.

Foam considered that such a crime would be highly hazardous, but he had no choice in the matter he had either to find the girl—dead or alive—or to disprove her father's suspicions. Cross was in no mental state to wait patiently for proof that Evelyn had merely slipped away. Besides, delay was dangerous because, in the worst case, the girl would be gagged and trussed-up in a restricted space, with a shortage of air.

At the far end of her room, Madame Goya sat at a small table near the radiator, stitching gloves. An adjustable lamp threw a cone of light upon her work, but left her face in shadow. Behind her were closely drawn window curtains of lined brown velvet.

Foam looked around for the evidence of a bed other than the inadequate divan, before he asked a question.

"Do you sleep here, madame?"

"I?" repeated the lady incredulously. "What a grim idea. I have a flat in St. John's Wood—This is merely a lock-up place of business."

It did not suggest a workshop to Foam's suspicious eye. It was so tidy and free from snippets or threads that he suspected the glove-making to be a blind to some dingier profession. At the same time he remembered the major's statement about objectionable tenants, so concluded that the line could not be too obvious.

He turned to the major.

"You searched the room thoroughly, of course?" he asked, "What about the window?"

"It was closed and the shutters bolted," replied Major Pomeroy. "This room is nearly hermetically sealed—Madame prefers to work by artificial light."

Foam's nose confirmed the statement. The temperature was that of a forcing frame, while the air smelt of burnt pastilles, rotten apples and fog. He glanced at the open door of the cupboard wardrobe which revealed a fur coat on a stretcher, and then crossed to the long mirror.

"Sure there is no door hidden behind this?" he asked as he tried to shake the frame.

"Look for yourself," invited the major. "The rawl-plugs are fixed as tight as a vice and there are no signs of tampering. You can take it from me that I've examined and tested every fixture personally."

"Not enough," declared Foam. "They must all come down."

He was surprised by the relief in Cross' eyes.

"I'll say this for you. Major," he said. "You know how to pick them. This young man seems to understand." Holding Foam's arm in a powerful clutch, as though to enforce his sympathy, he went on speaking. "You understand, don't you? I'm a stranger over here in a strange city and my daughter disappears in a strange house; not a friend near. No one I can trust or count on. It's like banging at a locked door. I can't get in."

"Everything is being done," said the major in a soothing voice, "I've rung up my builder and asked him to come over. He should be here soon."

"Soon?" repeated Cross with savage scorn. "Stop spoon-feeding me with dill water. While we're wasting time, what's happening to her? It's easy for you to be calm, but it's my girl that's gone. I'll break up the place if I have to do it myself."

As he spoke he gripped the mirror and tried to tear it from the wall.

In spite of his acquired crust and his ingrained suspicion of emotion, Foam felt a certain sympathy with his client. He had recently lost a favourite dog while he was exercising it in one of the parks. He soon regained it since his profession gave him a pull in dealing with dog thieves; but he still remembered the sharp thud of his heart when no cocker spaniel answered to his whistle and the horrible emptiness of the expanse of grass.

In order to give Cross time to recover, he turned to Major Pomeroy. "Who is this builder you've sent for?" he asked.

"He's the man who does all my conversion work," explained the major. "He's only in a small way of business, but he's honest and capable. His name's Morgan. To save time"—he stressed the words for Cross' benefit—"I told him to bring along a couple of men with picks, just in case it may be necessary."

"Good. I'll see if he's come."

Glad of an excuse to leave the torrid room, Foam went outside onto the landing and looked down into the hall. As he waited, he took note of his surroundings. The upper portion of the mansion had been redecorated recently, for the rough parchment-tinted paper was clean; but there were a number of scratches on the enamel paint of the staircase wall, evidently caused by the arrival and removal of furniture.

The damage seemed to point to the conclusion that, in spite of his system, the major's tenancies were short-lived. He was beginning to wonder the cause when the major gave him a practical proof of his consideration. He came out of No. 16 and stood beside Foam.

"It's fair to put you wise," he said in a rapid whisper. "I can't vouch for Cross. I know nothing about him. Better watch your interests and ask for a cheque in advance."

"Thanks. That's—"

Foam broke off as Cross appeared. Biting on a cigarette and blowing it up into continuous smoke he began to tramp the landing as though unable to keep still. As he passed No. 15, the door was opened and a dark girl, wearing slacks, limped outside.

With her arrival, a new element entered into Foam's life. He was one of those men who invest the past with glamour and whose boyhood was his happiest memory. Although he still lived in the same house—and liked it very much—it had shrunk and changed for the worse. The meals were not so good as they used to be. His parents had aged regrettably. The rest of the family had grown into uncongenial adults with families of their own. And the weather—which used to be perpetual summer—had gone to blazes.

Among the friends of his boyhood was the gardener who had borne a resemblance to the porter of Pomerania House; but his most treasured recollection was of a black-haired schoolgirl who had spent one holiday at the house next door. She was from the country and she introduced him to new adventures of her own invention.

He never forgot that enchanted summer or the girl who taught him to play. He never saw her again, but the instant he caught sight of the tenant of No. 15, he felt a rush of welcome as though he were recapturing the companion of his youth. Even while he knew that the lady in trousers must be Miss Green and "a little scamp," according to the major's description, he fell under the old spell.

She was certainly not shy, for she challenged attention by making an entrance as though she were on the stage. Her gaze flashed over the men like the sweep of a searchlight. Foam thought he had never seen so arresting a face as her eyes met his as though in unconscious greeting. Even when she spoke to Raphael Cross in a voice which was trained in elocution, he acquitted her of any charge of boldness. He felt instinctively that she was snatching a rare opportunity to test her personality and to hold the attention of an audience. "Have you found your daughter yet?" she asked.

Cross shook his head without speaking. As the girl looked compassionately at him, Foam felt absurdly jealous of the fine build and fair curly hair of his client.

"Of course not," the girl told him. "You've set about it entirely the wrong way. Why didn't you tell that young man"—her glance indicated Foam—"that you've lost an exclusive model gown? Leave out all mention of the girl who was wearing it. She'll only weaken the case... don't you realize that no one cares about the human element? All the laws are framed to protect property."

"Isn't that rather sweeping?" asked Major Pomeroy.

"I call it an understatement," declared the girl. "The law imprisons for theft but they only fine for cruelty. If I murdered you, the press would make me into a public heroine. I should be called a beautiful young brunette. But if I pinched a stamp off you, I should be put into quod and the papers would describe me as a young person. That's because stamps are property—and property is sacred."

"But why pick on me?" asked the major indulgently. "Oh, by the way, this is Mr. Foam. He will probably want to interview you about—"

He bit off the end of his sentence—in deference to Cross' feelings—and mentioned the girl's name.

"This is Miss Green, the tenant of No. 15."

"Viola Green," supplemented the girl. "I'm called 'Greeny' on the set. Nice cool little name, does it make you think of tender young lettuce?"

"No." said Foam. "Unripe apples."

He was determined not to be biased by Viola's attraction. In order to escape, he turned to the major with a suggestion: "While we are waiting for the builder, suppose I have a few words with Miss Power? Merely routine."

"You'll find her at home," said Viola, who seemed uncrushable. "Power's a lady. She peeks behind curtains while I run out into the street to see the accident. And she's incredibly rich. She has all the proper pots and pans. I know, for I borrow them."

When Miss Power opened the door of No. 17 in response to the major's ring, Foam summed her up in his first glance.

"Country rectory."

She was about twenty-seven—probably younger—with short blunt features and a set expression which suggested strength of character. She was not perceptibly powdered and used no lipstick. Her thick fair hair was brushed back and worn in a small knot at her neck. She wore a tailor-built suit of blue-and-green speckled tweed—the skirt of which was calf length and revealed sports stockings and stout brogues.

"Will you come in?" she asked formally, after the major had explained Foam's standing.

As he looked round him, Foam noticed that the room was smaller than Madame Goya's and bore signs of being a living-place. It had evidently been converted into a flatlet by the expedient of chopping off a strip at one end, for part of it was concealed by a cream-painted wooden partition.

There was the same standardized suite and buff Axminster carpet as in Goya's apartment, with the addition of a cheap wardrobe and an oak bureau. The central table was piled with books and papers, besides a portable typewriter and two framed photographs. One was a cabinet portrait of a clergyman—the other a hockey team of schoolgirls, wearing tunics and long black stockings.

The faces were too small for recognition at that distance, but Foam was certain that Miss Power was among the players—probably as captain. Miss Power apologized for the disorder.

"Rather a mess—but I'm studying at high pressure for an advanced exam. I've been working here all day. I've already told Major Pomeroy that I've seen no strange girl. No one, in fact."

"Did you hear her voice?" asked Foam.

"No."

"Are these walls thick?"

Miss Power glanced interrogatively at the major, who answered the question.

"As a matter of fact, the dividing wall between No. 16 and No. 17 is merely lath and plaster. The original wall was removed during the conversion. I had to take in some of Madame Goya's apartment to make the flatlet."

"Rather a risk of disturbance in the case of a noisy tenant," commented Foam.

"I hear nothing of the next-door tenant," remarked Miss Power coldly.

Foam realized that it was characteristic of her type to profess ignorance of her neighbour's name, although she must see it daily on Goya's door. He also concluded that the glove maker's mysterious occupation was discreet, for Miss Power would not hesitate to lodge complaints.

"Does the second door lead to your bedroom?" he asked, glancing at the partition.

"No," replied Miss Power, "I sleep here on the divan. Kitchen, bath and the rest are down that end. Slum conditions—but one has to pay for an address... You can look inside."

Foam inspected the premises alone, for the major took the opportunity to go outside. There was the anticipated clutter of cramped domestic fixtures, but no sign of an extra exit. Unless, however, the builder revealed a secret egress from No. 16, the adjoining flatlets were free from suspicion.

"Thank you," he said. "I hope I shall not have to disturb your work again. If you should learn of anything unusual about this building or the tenants, will you let me hear. This is my number."

Her swift glance at the photograph of the hockey team made him aware of his blunder. He had outraged her code of playing the game. Ignoring his card, she opened the door.

"I'm too busy working to notice anyone or anything," she told him coldly.

It was a relief to return to the landing and into a friendlier atmosphere. His heart felt absurdly light when Viola limped to meet him, as though she, too, recognized a bond between them. She might have been the playmate of his childhood inviting him to play, when she whispered to him from a corner of her mouth:

"The major's in the hall, giving the builder the lowdown... Isn't this a thrill? Aren't you loving it?"

"I should," replied Foam. "I'm getting paid for it."

"Oh, of course. I forgot you're a cop. You look just a nice boy, with no brains and rather tough... Well, from the criminal angle, how does Power strike you? She reminds me of an underdeveloped 'still.' Too true to type... do you suspect her—or anyone?"

With a rare wish to humour her, he compromised. "I'll tell you someone whom I trust. It's Higgins."

"Who's 'Higgins'?" asked Viola.

"The hall porter, of course."

Viola began to laugh heartlessly. "You poor sap, don't you know the first rule is never tell your real name to a policeman? The porter is 'Pearce.' He double-crossed you all right."

And then—swiftly and sweetly—just as his childish playmate used to relent after she made fun of him—Viola changed her mood.

"You win," she said. "Pearce really is honest. He's hopeless at telephone lies. The time I've wasted, trying to corrupt him... Not dishonest lies. Just professional swank. You've got to swank in the profession... look, here's the builder."

She stopped talking to gaze with frank interest at the builder. He was a burly Esau, with shaggy hair and bushy eyebrows. His face was hollowed by elongated pits—the graves of original dimples—and his brown eyes were a challenge to humbug. He gave an impression of bluff honesty, plus intelligence, but minus any scruples with regard to personal feelings.

Foam liked him on sight, from his bowler hat to his square-toed boots. He commended him, too, for the brisk manner with which he came to the point.

HAVING made his protest, the builder was now officially on the job. Calling his men from the hall, he clumped into No. 16 and gave a quick look around it.

"Everyone outside, please," he ordered. As the only inmate of the room, Madame Goya recognized the personal note. She surged forward, her fat arms outstretched like the wings of a guardian angel, resisting pollution of her premises.

"Pardon," she contradicted, "I shall stay. This is my flat. I am within my legal rights to see what goes on here."

The builder, who was married, knew when he was outclassed he turned instinctively to the major for protection.

"Can we run out the furniture, chief?" he asked.

"Afraid not," replied the major nonchalantly. "It would block the landing."

"All right, you're the boss. But I warn you we'll waste time shifting all this junk about... Madame, I am sure you would prefer to remove your valuables yourself?"

The workmen exchanged grins when Goya, with slow and measured movements, cleared from the book shelves a collection of odd china, dead flowers, cigarettes, packs of cards, cosmetics, a crystal, cactus plants and a tea outfit, besides a few novels which bore the labels of a twopenny lending library. She piled them up dangerously on the chairs and also upon the marble mantelpiece which had been retained when the grate was modernized.

"Now then, get a move on," ordered the builder impatiently. "Start and shift the glass."

Following his instructions, the men unscrewed the long mirror and propped it against an armchair. Its removal revealed no outline of a concealed door through which Evelyn Cross might have been whisked. There was nothing more incriminating than long drooping moustaches of cobwebs on the wall. The cupboard wardrobe was next wrenched from its position—not without damage to the panelling. Then the huge goddess came down to earth with a bump when her frame was swung off its nails.

Soon the room was cluttered with fixtures, but Goya persisted in remaining, although the builder chased her from one refuge to another as he examined and sounded the woodwork. The major also stayed, apparently to protect his interests. Foam and Viola could only get an occasional glimpse of the proceedings, for Raphael Cross blocked the doorway.

At first he watched every movement with concentrated eagerness; but with lack of results, his keenness staled and he could not control his impatience. As he paced the landing again, Viola drew Foam's attention to the fact he kept lighting cigarettes, only to throw them away after a few puffs.

"He's like a planet," she whispered, "No rest for him... It makes me boil. You can see he's in hell—but the major is only worried about the damage to his precious property... Oh, come along—I want a front stall for the show."

She plucked Foam's arm and dragged him across to the doorway. He noticed that she seemed actually to thrive on excitement, for her colour grew deeper under her rouge. Although he felt a curious pleasure in sharing the experience, he considered it his duty to warn her of a possible shock.

"I'm going to say something you may not like," he told her.

"Sounds like an overture," she remarked. "But I'm a modern girl. I can take it."

"Just this. That girl's father is nearly off his rocker. Now I suspect he has grounds for his guess—whatever it is. That's why I want you to go back to your flat while the going's good.'

"Why?"

"Because they may find her—and a murdered body is not a pleasant sight."

Although her eyes expressed horror at the prospect, she was not convinced.

"That's all right," she assured him. "I can't be sick for lack of raw material."

At that moment, as though he were following Foam's train of thought, the builder spoke to Major Pomeroy.

"The panelling is O.K., chief. We'll try the floor next for loose boards."

He gave the order to the men.

"Roll up the carpet. Shift the stuff as you go along."

Wedged into a corner by a displaced divan, Madame Goya made an angry protest. "Am I included in the 'stuff'? Let me out, you idiots."

Then she turned to jeer at the builder.

"I don't know what you think you're doing. If there was a trapdoor in the floor, the girl would have dropped through the ceiling of the room below. Very clever of you."

Her eyes bulged at the builder's blunt explanation.

"A body could be wedged in the space between the floor and the ceiling boards," he told her.

"A body?" she repeated, in the rising note of hysteria. "Ah, now I'm beginning to understand. I've been very dense. I've only just realized that I am under suspicion."

As the builder retreated before her threatening advance Major Pomeroy tried to soothe her.

"No one is suspected," he said. "The idea is farcical. We are simply doing our best to satisfy Mr. Cross that his daughter is not on the premises."

"Indeed? That doesn't fool me. Now it's my turn to give orders. I insist on this room being hacked to bits, to clear my character."

"That's not necessary," explained the builder. "I've tested every inch of the walls and there's not the smell of a hollow ring."

"What are you holding up the work for?" demanded Cross, pushing his way into the room. His ice-blue eyes glittered angrily at the major's explanation. "Haven't I made myself plain?" he asked. "Strip the walls—and to hell with the expense."

"Finish the floor first," said the builder.

His examination proved a lengthy business, owing to the accumulation of furniture. There were constant checks and displacements while the men rolled back yard after yard of carpet to expose dirty, stained boards. Foam was growing bored when a diversion was created by the major's secretary whom he had met in the office. She entered the room quietly and slipped a typewritten paper into her employer's hand. He glanced at it and then strolled across to Cross.

"Mind signing this?" he asked casually. "It's merely to indemnity me for damage. Better read it first."

Ignoring the advice, Cross scrawled his signature with a force which drove the pen into the paper. The major shrugged as he placed it inside his note case. "Not too satisfactory for me," he explained to Foam in a whisper "Merely a gentleman's agreement, it doesn't cover the ground, but I could not worry the poor chap with details." As he spoke, there was evidence of an increasing bill. With a crash, followed by the splintering of glass, the long mirror fell forward against the marble mantelpiece.

Madame Goya screamed like a steam siren before she began to blame the nearest workman.

"It wasn't me, mum." he declared firmly. "You moved the chair it was laying against."

"But it shouldn't have been on the floor at all," she wailed. "It was safe on the wall. Who's going to buy me a new mirror?"

"That will be taken care of," promised the major quickly as the builder rose from his knees. He dusted the knees of his trousers and shook his head.

"Floor's not been tampered with," he said. "The window's screwed and the grate sealed. That only leaves the panelling."

The men began the work of demolition in a gingerly manner, first loosening the panels before removing them carefully. Instead of commending their caution, however, their slow progress only exasperated Cross to fury.

"Smash it up," he commanded.

The builder caught the major's eye and nodded.

"It's only cheap wood," he said. "It's not genuine old stuff."

The men seemed to enjoy their job after they had received license to wreck. They hacked at the wood and tore it down in jagged sections while Viola gasped with rapture.

"Gorgeous," she said. "I'm just in a mood to appreciate a nice spot of destruction."

"Why?" asked Foam.

"Because property can't feel. No nerves."

"Any connection with the I.R.A.?"

"No, no initials by request."

"Then why have you got this extraordinary grudge against property?"

"Because I am one of the unemployed," Viola told him. "Yesterday, I was a mannequin. I was showing a dress when I slipped on the polished floor and did a nose dive. I passed out cold—but no one bothered about a little thing like that. They reserved their sympathy for the model gown. I'd split it when I fell and it was ruined. So I was sacked."

She stopped her story and caught hold of his hand.

"I've got to clutch someone," she said. "I've been mopping it up—but now I'm growing afraid. There's only one panel left. It will be there—behind the last bit."

She infected Foam with some of her apprehension. In spite of his common sense he could feel the electric quality of her suspense vibrating in her fingers as he watched the swinging picks of the men. He heard the heavy breathing of Raphael Cross, while Madame Goya stood motionless like an idol.

Then the last section of panelling was removed—to reveal only a blank plaster surface...

Foam was conscious of deep relief—and unconscious of a stifled flicker of disappointment. This case had promised to be something out of the ordinary. In spite of sordid eavesdropping and vigils, his sense of romance was not extinct. The secret service was still the poster of a thrilling film—plastered with foreign travel labels and drilled with bullet holes.

But now the alleged disappearance of Evelyn Cross was revealed as the wild guesswork of hysteria. A man had lost his head and played the fool. Probably a drink too many over the odds.

The time was still to come when he would envisage the case as a newspaper poster of a crime, with blood-stained corners flapping in the wintry rain—a record hideous with gruesome details of cold-blooded murder...

At first, no one dared to look at Raphael Cross. The workmen began to grin but quickly composed their faces in recognition of an awkward situation. Then the builder spoke to Major Pomeroy.

"The way out," he said, "is through this door. It's close on six. I'll be seeing you in the morning, chief."

He hurried away as though to avoid any further argument, while the others straggled after him. As he reached the landing, the decorative typist—Marlene—began to descend the flight of stairs leading to the second floor. She was dressed for her homeward journey, for she wore a fur coat and a comedian's hat; but she had been waiting for her chance to see the mysterious Evelyn Cross again.

The sound of six notes striking from a church tower in the Square made the builder glance at the tall grandfather's clock which stood out from the wall in one corner of the landing.

"Stopped," he commented. "That's the worst of these antiques."

"Oh, Grandpa still toddles more or less," explained Viola. "At his age, he likes a rest now and again—but he was going strong this afternoon."

Her words made Foam glance casually at the clock, when he noticed that the hands were stationary at seven minutes past four. This was about the time when Evelyn Cross had visited Pomerania House.

He could never explain the impulse which made him suddenly open the back of the case. As he groped in the interior, he could feel two foreign bodies which had interfered with the mechanism of the works. Drawing them out, he held them for inspection.

A pair of fashionable ladies' shoes with very high heels.

THERE was no doubt in Foam's mind as to their ownership, He turned instinctively to Raphael Cross who was staring at them as though stunned.

"Are these your daughter's shoes?" he asked.

"Yes," replied Cross dully.

"Can you identify them positively?"

Cross twisted his mouth in doubt before he shook his blonde head.

"Of course not," she said. "But it's the kind she always wears."

"You're sure there are no distinctive marks?" insisted Foam, thrusting the shoes into his hand.

"Hell, how should I know? Her shoes all look alike to me."

Although he himself hardly knew pink from blue, Foam was annoyed by this lack of paternal perception. Before he could connect the shoes positively with the missing girl, he would have to establish her claim by the tedious process of elimination.

Fortunately Viola came to his rescue.

"They aren't mine, worse luck," she said. "And they aren't Power's. She always wears the sensible sort, with low heels. Perhaps they belong to Madame Goya—"

"Pardon," broke in a confident voice. "Those shoes are mine."

Foam did not need Viola's gasp to realize that the claimant was a courageous opportunist. The decorative typist—Marlene—stepped forward and took the shoes from Cross' limp hands.

"I bought them last week, in my lunch hour, at the Dolcis in Shaftesbury Avenue," she explained glibly. "They had a sale on. You can see the soles aren't marked. I've not worn them yet."

"Last week?" commented Foam. "Why didn't you take them home?"

"Because I've been out to dinner and pictures every evening. I couldn't lug a parcel round with me."

"But how did they get inside the clock case?"

"I can't even guess," replied the girl lightly. "Someone's idea of clean fun, I suppose... Well, thanks frightfully for finding them. Bye-bye."

"And try checking up on that tale," muttered Viola ironically, as she watched Marlene's triumphant descent. "A sale and the lunch-hour rush. Nice little combination... Well, she's got them now for keeps—and good luck to her."

"Am I right in concluding that young lady has a successful technique?" asked Foam.

"Positively stunning," Viola told him. "She eats on the house. Everyone takes her out, from the boss to the office boy. Fair play to her; she treats them all alike... Now I'd be nice to the boy and snub the director. That's snob complex, really."

She stopped talking as Madame Goya came on to the landing—her draped figure looking massive and majestic as the Statue of Liberty.

"Don't let the men go," she commanded Major Pomeroy. "They'll have to move my things at once. It's up to you to find me good temporary quarters in this house... Impress on the builder to make a rush job of renovating No. 16. I can't risk losing my connection."

"You shall have preferential treatment," the major assured her with dreary patience. "If you will go down to my office, I'll join you as soon as I possibly can."

He glanced uneasily at Cross, who still stood staring into vacancy—and then basely shifted his responsibility to Foam.

"You'll want to discuss this business with Mr. Cross," he said. "What about my flat? It's next to my office. You'll find drinks there."

"Nothing for me," broke in Cross. "I've got to get this clear. Where's Evelyn? Where's my girl?"

He staggered slightly and stared helplessly around him, as though trying to find a chair.

Instantly Viola slipped her thin arm through his and marched him into No. 15. She pushed him down onto the divan and then ducked behind the partition at the end of the room. When she came back, she was holding a small tumbler. "Drink this, darling, and you'll feel better," she invited Cross.

When he made no attempt to take it—but sat and rubbed his eyeballs—she changed her tactics and gave him a smart slap on the cheek.

"Snap out of it," she commanded.

His response to treatment was immediate. His eyes lost their daze of apathy and the muscles of his face ceased twitching. For one moment, he glared at her as though he would attack her; then his fury gave way to surprise and he swallowed the brandy.

"Thanks," he said. "You understand."

His self-control restored, he turned to Foam.

"Now, young man," he said briskly, "I want to hear your opinion."

"Suppose we consider the facts," suggested Foam. "Will you admit that your daughter could not have been kidnapped inside this house? It takes a complicated conjuring apparatus to work the 'Vanishing Lady Illusion'—and the builder proved the room had not been tampered with. Do you accept his report—and the evidence of your own eyes?"

"I must," said Cross.

"Good. The alternative theory is that she faded into air... Do you believe in the supernatural?"

"Hell, no."

"Then the only explanation is this. Your daughter slipped past you when all of you were too engrossed to notice her. This sort of thing has happened before. Famous pictures have been stolen from galleries when they've been crowded with tourists. The thief has contrived to choose the psychological moment when his confederate distracted their attention... Of course, in your daughter's case, it was unintentional and not deliberate. I feel sure she'll soon be back at your hotel."

Foam stressed his words for he wanted to convince not only his client but himself. While common sense forced him to accept his own explanation, he knew that he had not flattened out every snarl in the tangle. It was true that five persons had declared that Evelyn Cross had gone upstairs and had not returned; but four of these witnesses were not entirely reliable. Cross was neurotic and the major influenced by his own interests, while neither Madame Goya nor Marlene inspired complete confidence.

There remained the porter. Foam believed that his testimony was both honest and truthful; but he could not acquit the man of a natural self-deception. He was sure that Pearce did not remain at his post with the fidelity of the lava-submerged sentry at Herculaneum, because when he arrived at Pomerania House the porter was outside the house and fraternizing with Raphael Cross' chauffeur.

Up to this point, therefore, the inference was that Evelyn Cross had made a voluntary disappearance—which was a rational deduction. Unfortunately, Foam's complete confidence had been flawed by the discovery of the shoes. Since it was obvious that they belonged to her—in spite of the typist's claim—they introduced an element of mystery into the case.

Foam could not understand why Evelyn should have removed them as a preliminary to walking upon fog-slimed pavements, while her choice of a boot closet was even more perplexing. The mere act of opening and shutting the clock case would advertise her presence on the landing and shatter any alternative idea that she wished to creep away noiselessly upon stockinged soles.

He was relieved when Cross sprang from his chair with restored vigour. "I am sure you are right," he said to Foam. "There's no need to worry."

As he looked around him, his keen eyes' remarked the poverty of Viola's apartment. The familiar suite and buff Axminster carpet seemed to indicate that Major Pomeroy had semi-furnished these three rooms in order to exact an increased rental. There was little else besides a cretonne curtain—with pierrots printed on a black ground—which concealed a row of pegs and served as a substitute for a wardrobe.

Instead of a mirror, a large bill of a stage performance by the London Repertory players was pinned over the mantelpiece. Cross picked out the name of "VIOLA GREEN" printed in small type.

"Professional?" he asked, looking at her with new interest.

"I'm trying to be one," she confessed. "It's funny. Power looks like a vicar's daughter and probably comes from a brothel. Now I am a scallywag, but I really am a parson's daughter. We're a tragic family. We're all in the church, and we want to go on the stage."

"What happens then?" asked Cross.

"We have to stick in the church. The tragedy is we have no talent. But fate's most ironic blow is this: My grandfather really is a born comedian, yet he will persist in being a bishop. No ambition."

"Never mind. Perhaps I can help you. I've some influence in a film company... No strings to the offer, my dear. You've been good to me and I don't forget. I have a daughter of my own." The light gleamed on his fair, curling hair as he expanded his broad shoulders and drew himself up to his full height. His head was thrown back so that his heavy chin was merged into the powerful muscles of his neck. At that moment, he presented such a splendid type of self-assertive manhood that Foam—who was glad to be ordinary—felt a twinge of jealousy.

"Here's my card," said Cross. "Send in your bill and you shall have a cheque. You stood by, and that helped... Good evening."

"I'll come down with you," offered Viola.

Foam did not attempt to accompany them, for he wanted to snatch the chance of making a few notes. Whenever he took up a new case, it was his custom to jot down his first impression of every person. It was essential to capture these mental snapshots without conscious thought, so that it could not be a reasoned opinion but merely an instinctive recognition of personality.

The second step was to put the results in his office drawer and forget about them until the time came to compare them with his up-to-date knowledge of a client.

On this occasion, he was afraid that he might be unable to trap an unbiased impression of Viola. Trying to make his mind a blank, he scrawled rapidly across the small pages of his notebook, as though his fingers were the medium of automatic writing.

He snapped the elastic band over his book as Viola limped back into the room.

"Sit down," she invited. "I've still chairs left. If you'd come last week, you'd have seen me in all my glory with a gorgeous meretricious suite of veneered walnut. All the wrong people admired it. But the plain van took it away... Sorry I have no booze. Your client had the last drop."

"What do you think of him?" asked Foam curiously.

"Good looking in that way," commented Viola casually. "Gosh, he registered enough emotion for twenty fathers. I've got a hunch he is a sugar daddy. It would be enough to make him all steamed up if his girl walked out on him and he couldn't produce her to her lawful parents."

Foam had too expert a knowledge of faked relationships to reject Viola's theory. As he was not concerned with the morality of a case, he even welcomed it because it helped to explain his own instinctive distrust of Cross. He had attributed it to unworthy prejudice, based on a dislike of spectacular good looks. But now he realized that the root of his suspicion was his inability to credit Cross with the ordinary feeling of a father. He could not imagine him tossing a baby up in the air or running a small daughter to school in his car. On the other hand, he could picture him at the races, cigar in the corner of his mouth, hat tilted over one eye and accompanied by a flash lady friend.

He realized that Viola had curled herself in a big chair and was looking up at him with inquiring eyes.

"He made rather a nasty crack when he told you to send in your bill." she said.

"I shall charge him for my time," explained Foam.

"Tell me all about your work."

He slew the impulse to magnify his job.

"I do hole-and-corner jobs for people who don't want police limelight," he said. "It's a sordid life. My mother thinks it has made me a rough and common person."

"It's made you real. I've no use for fakes... have you got a fag?"

As he lit her cigarette, he asked her a question. "Have you any idea of Goya's real business?"

"I should say it's crystal gazing and a spot of blackmail," she replied. "Crowds of society people steal up to consult her. My guess is she's in with a bunch of business crooks and gets tips from tainted sources. I mean she bets on certainties and sometimes sells the dope to her clients. She knows which horse is going to be pulled and which round the heavyweight is going to sleep."

"Have you heard of any trouble with the police?"

"No. She'd be too cautious. When I asked her to tell me my fortune, you should have seen the dirty look she gave me."

Although he believed the case was finished, Foam continued to tap her feminine intuition for the pleasure of watching each change of expression which swept over her vivid face. "Have you any slant on Miss Power?" he asked.

"No. If she's what she looks like, you know as much about her as I."

"The major, then?"

"Oh, he's a gentleman—even when I'm late with my rent. But he's like a gull after money. He sees it miles away and swoops."

"Thanks. Thanks for everything. I've got to get back to the office."

She looked after him wistfully when he reached the door. "It's been fun, hasn't it?" she said. "Come in again and tell me the end of the story."

"I'll do that... But this is the end of the case." Foam spoke confidently and with conviction.

On his return to the office, he outlined the affair to his senior—Mr. Gribble—who agreed that Cross had been fooled, not so much by his daughter as by his own conscience. Such a fury of suspicion and fear indicated a murky past when it was based on the certainty of enemy action.

"That's his own affair," was the cynical official opinion. "Find out if his cheque is good."

Another case had broken, so Foam worked late. Just as he was about to leave, he rang up Cross' hotel, merely for confirmation.

"Is that the bureau?" he asked. "Can you tell me whether Miss Evelyn Cross is in?"

"No," replied the clerk. "She went out this afternoon and she's not come back yet."

Foam had lived that moment before... For an instant, he felt a sense of frustration and loss, as though he were staring again at a stretch of empty grass and whistling to a dog which was already far in the distance.

He shook off the impression. Opening his notebook, he reread the high-pressure jottings he had made in No. 15 on the characters in the case.

"Raphael Cross. Volcanic. Too good looking. Unfatherly, dark horse."

"Major Pomeroy lean, long faced, well dressed. Old school tie, decent instincts. God save the King."

"Madame Goya. White hair, dirty face. Fishy business. Wouldn't play cards with her."

"Miss Power. Blonde, solid, tweedy hard voice. Been to right school."

"Viola Green. Brunette. Too thin. Wears trousers. Anti-property bias. Stimulating."

It seemed to him a pitiably poor collection of drivel. Such a pallid crop of potted personalities was not worth, pencil or paper.

Yet there—under his eyes—were two separate clues which, later, were to help him towards a solution of the mystery.

FOAM was fortunate in the possession of a pleasant home background. His parents lived in a large house in Highgate, which—in spite of family prosperity—resisted change and clung to its shabby old-fashioned comfort. The furniture and carpets had grown to be such old friends that renovation was out of the question. Usually, pets had to be ejected from the best chairs when they left their fur behind them in token of ownership.

In spite of these shortcomings, the atmosphere was genial and the standard of living lavish. In winter, huge fires leaped up the wide chimneys and often set them afire; while Foam Senior was as discriminating over his cellar as his wife was generous in her housekeeping.

The father was an officially retired doctor who retained a few favoured patients for the sake of occupation. He took a keen interest in his son's work, regarding the agency's sordid cases as a substitute for lurid fiction. Alan pandered to his weakness, for he knew that he could trust in his professional reputation for keeping secrets.

That night, after he had reported his day's work, the doctor looked at him severely over his glasses.

"Are you satisfied with the findings?" he asked. "If it were my case I should want a post-mortem... To take one point, how do you account for the complication of the discarded shoes?"

"Why should I?" asked Foam. "There is no more definite proof that they belong to the Cross girl than to the typist. My own guess isn't evidence."

"Then mark my words, my boy, there's another guess coming to you."

Mrs. Foam, who was excluded from official confidences, overheard the last sentence.

"Alan doesn't guess," she contradicted. "He deduces—in the same way that you diagnose."

"Rubbish," chuckled the doctor, "I may ask my patients questions and observe their symptoms, but I have to guess what double-crossing is going on inside them. We all guess. Even you have to guess what time to put dinner."

He winked at Alan, inviting him to share his amusement over his wife's wrath. Long experience of meals all around the clock had made her expert in dealing with the eternal conspiracy of a doctor's household against the cook. For the rest, she was a kindly, capable woman, who sat on boards and knew as much about drains as a plumber.

"I organize," she cried indignantly.

The subject of meals reminded Alan of a girl who had claimed immunity to sickness from a basic cause. He wondered whether she were hungry. It was true that she had been unemployed for a very short time; but he could imagine her spurning her final wage envelope as a grand gesture of compensation for the damaged gown.

"How does a girl make out when she is sacked?" he asked his mother.

"She goes to her exchange and claims insurance while she is unemployed," explained Mrs, Foam.

"But this girl's not organized. She's a fathead and too film crazy to keep a decent job."

"Can she act?"

"She thinks she's rotten, but off the stage she puts on a very good show."

"Then I should ask her out to dinner as often as possible."

Mrs. Foam's eyes gleamed with pleasure behind her glasses, although she preserved her poker face. This was the first time Alan had expressed interest in a girl.

The following morning, directly he reached the office, Foam had a call put through to Cross' hotel. At first he did not recognize the voice which replied when he asked for his client. It was no longer roughened by emotion, but confident and even jaunty.

"I suppose your daughter is back?" he asked with stressed heartiness.

"No," replied the voice casually. "But I heard from her this morning."

Although it was not the news he had predicted. Foam drew a deep breath of relief.

"Good," he said. "I was sure you would hear. Where was the letter posted?"

"Oxford," replied Cross. "It was just a picture post card of some college. The time stamped on it is ten-thirty p.m., last night."

"Does it clear up the mystery?"

"Practically. Hold on a minute and I'll read it to you."

After a short wait, Cross' voice boomed down the wire.

"I've found it. It says, 'Sorry to walk out on you, but I had a date for a week-end in the country. I'm still a hick and my friend is swell. And did I fool you! All your fault for butting in. Back on Monday.'"

"Is it her handwriting?" asked Foam.

"I'd say it was."

"Did she take your car?"

"No. She says she's with a friend... Well, this takes care of everything. Send in your bill. I want to get clear of the whole affair."

"Thanks." Foam spoke absently, for he was still chewing an undigested chunk of the post card. "What does she mean when she says it was your fault that she had to fool you?"

"I think I know," chuckled Cross. "When she goes out, she always comes in the car with me and I drop her somewhere. She told me to put her down at Pomerania House, but really she was going to meet this friend of hers in the Square. I threw a spanner in the works when I said I'd come in with her and see Major Pomeroy. Her appointment with the Madame was only fake... Anyway, that's my guess."

"Sounds plausible," agreed Foam. He was about to ring off when Cross spoke to him again.

"Will you be seeing little Greeny soon?" he asked.

As he listened to the familiar title, Foam's ears began to burn. He felt the impotent anger of an outclassed rival as he remembered his last vivid impression of Raphael Cross—flamboyant and forceful—his blonde hair gleaming under the electric light. In the space of a few minutes he had cloven an entrance into Viola's life, compelling her confidence.

"I shall be seeing her tonight," he said quickly.

"Good," commented Cross. "Will you tell her I may be able to pull off a good job for her? Something in her line... That girl would never stand behind a counter or tap a machine. She warns a bit of the spice of life. I should know something about girls, with one of my own."

"What is the nature of the job?" asked Foam.

"Companion to William Stirling's daughter. I met them in the Queen Mary, coming across."'

"'You mean Stirling, the millionaire?"

"Millionaire, my foot. The chap's a multi-millionaire who gave his wife diamonds to the value of a quarter of a million, British currency, just as you and I give our wives a diamond bracelet."

Foam was beginning to realize that Cross' use of the plural was typical of an extravagant standard. Apparently the man had to exaggerate values as well as emotions.

"How can you recommend Miss Green?" he asked. "You know nothing about her."

"Oh, Mrs. Stirling will take up her social references. But she will rely on me to give her the personal slant. I'm a judge of character. That girl has guts. I was going over the edge when she blacked my eye."

"She only flicked your face," corrected Foam.

"Same thing. She saved me... I shall be seeing Mrs, Stirling this afternoon. Tell Greeny to ring her up this evening and mention my name. Mrs. Stirling won't go after her. She'd better clinch it while the going's good. Tomorrow there'll be a queue of applicants after the job, a mile long."

"I'll try to impress her with the importance," promised Foam, who was beginning to discount the face value of Cross' statements. In order to prove to himself that he was not jealous of such a comedian, he added casually, "Why don't you go and see her yourself?"

There was a short silence. When Cross broke it, he had ceased to bellow like a stag in the mating season.

"I can't bring myself to enter that house again," he said in a husky voice. "It will stir up the mud in my brain. That's something I must forget."

"I understand," said Foam.

"Then it's more than I do. I can't make out if that bunch is on the level. The major seemed a gentleman. When Greeny went back upstairs, he told me she often stings him for her rent, but he doesn't like to turn her out. The fact is, his sort shouldn't be in business. Too soft... Now just take down Mrs. Stirling's number and see to it that Greeny rings her."

When Foam rang off, he gave the bookkeeper instructions to send in the bill of Messrs. Girdlestone & Gribble. Since the case was officially ended, he tried to forget it; but at the back of his mind was a vague unrest, probably a symptom of a grumbling curiosity.

He wanted to see the elusive Evelyn Cross in the flesh and hear the exact details of how she had managed to slip away from Pomerania House. Further, he wanted to appease his vague distrust of Raphael Cross, which persisted in spite of the fact that Viola's new patron had entrusted him with a welcome commission.

He switched on to a new case where his client—a retired schoolmistress—was being blackmailed through the indiscretion of a talking parrot; and he worked at it with savage energy, mainly because the blood-sucker was a youth with blonde curling hair.

It was fairly late in the evening when he was free to visit Pomerania House, directly he entered the hall, he smelt the acrid odour of distemper. There was further evidence that the house decorator was in action, in lightish smudged footsteps on the red rubber flooring of the stairs.

"Have they started work on No. 16 already?" he asked Pearce.

"Started and finished," replied the porter. "They made a rush job of it because Madame carried on so about being turned out of her room. The builder had to put on all his men. It was only papering. It's the painting as takes the time. Do you want to see the major?"

"No. Miss Green."

"She's in. Go right up."