RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

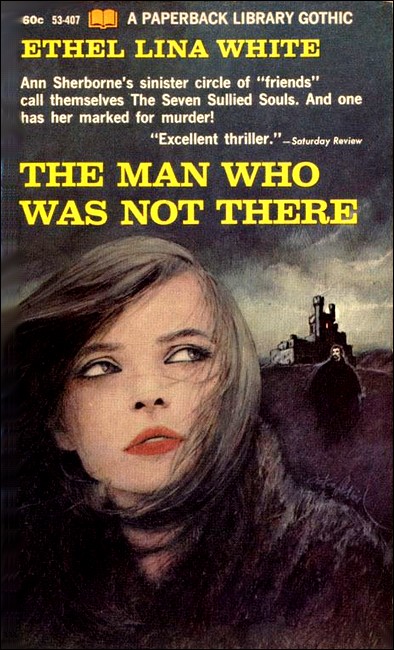

"The Man Who Loved Lions," Collins Crime Club, London, 1943

"The Man Who Was Not There," Harper & Brothers, New York, 1943

ANN SHERBORNE gazed at the ringed date in her pocket-diary. It was the fourteenth of November, 1941.

"After all these years," she thought, "it has come at last. I can't believe it. It's to-night..."

Seven years ago, on a wild November evening, high up in a turret-room which seemed to sway in the wind, this reunion had been arranged. Richard—their host—handed to each guest a card of typed instructions, reflecting his peculiar humour which specialised in insult.

Reunion of THE SULLIED SOULS at Ganges, November the fourteenth, 1941. According to custom, the tower- door will be left open—trustfully and without prejudice to character—from eight to twelve. Bring this card for purpose of identification. In seven years we shall all be changed and inevitably for the worst. Do not fail to keep this appointment, dead or alive, but preferably if dead. You will be livelier company."

At the time of their last meeting, Ann only anticipated a temporary separation from her companions. Within forty-eight hours, however, she was on her way to Burma, with her parents. Her father was a brilliant engineer—as well as an intermittent drunkard—so that his wife had to work overtime to keep him anywhere near dry-level.

The quiet little woman was responsible—indirectly—for some fine constructional work. When she died, she kept the contract in the family by passing on her job to Ann.

During the weeks and months spent in exile, Ann never forgot the reunion. At the beginning of each fresh year, she drew a circle round the date in her pocket-diary. She used to stare at the enchanted numeral in a passion of longing. Richard's card of admission grew grimed and limp from being read in many a different scene and climate—high up in boulder-blocked mountains and besides sliding brown tropical rivers; above the snow-line and in the glare of the desert.

As the years passed, her first doubts began to sharpen into fear. War broke out and her father decided not to return to England. When he signed a contract with a water corporation in Florida, she gave up hope of keeping her appointment in the flesh.

"There's only one way," she told herself. "Get a monkey's paw, mail it to Richard and pass out. He'll attend to the rest."

Near the end of October, 1941, her father died suddenly. At the time it seemed too late for her to return as all the odds were against her...But on the evening of the fourteenth, she was in a hotel in the heart of London, waiting for the minutes to pass before she set out for the place of reunion.

She sat at a small table in the crowded lounge, wedged in her place by a pack of occupied seats, while a continuous procession of people streamed past in search of a vacancy. Beside her was an elderly man who had come down from Lancashire on business. A keen judge of values, he had noticed her at breakfast and was struck by the force of character evident in her steadfast eyes and resolute lips.

He was engaged in reading through his list of future engagements and he snapped the band around his book at the same moment as Ann closed her diary. Their eyes met and they smiled at the duplicated action. He had noticed previously that to her, a stranger was just another human-being and not a possible plague- contact, so he risked speaking to her.

"We both seem to be checking-up on our dates. Are you in business?"

She hesitated because the reunion was her secret; but since the shadow of the tremendous event was beginning to sag over her, she looked at his shrewd kindly face and was tempted to talk.

"My date isn't business. I'm meeting people I've not seen for ages."

"Friends?" he asked.

"No...It's queer, but really I know nothing about their private lives. I can't think how we ever got together. We were students at a college in London and we attended the same biology lectures."

"Did you form a club?"

His interest was so kindly that it redeemed his questions from curiosity and Ann was encouraged to expand.

"It was more like a cult. Richard wanted devil-worship but no one would back him up. So we used to meet secretly and discuss world affairs. Richard was always planning purges and he kept a list of victims. He called us 'THE SEVEN SULLIED SOULS.'"

"And were you sullied?" asked the Manchester man, smiling at the pompous title.

"I can only speak for myself," Ann told him. "I was sixteen and very pure. But I kept quiet about my age and all that. As a matter of fact, I can't believe that anything could happen to either James or Victoria. James was one of those vague people you forget and Victoria was wrapped up in her work. But John and Isabella were so glamorous that I don't think they could stop affairs...And I could believe anything of Richard."

Even in the heat of the lounge, she shivered at the recollection of his face—intermittently revealed in the leaping firelight—as they sat in the darkened tower-room. Deep lines gashed it from his extravagantly-arched nostrils to his mouth. She remembered too the corpse-like pallor of his skin, the shining black hair and the sinister upward slant of his brows.

"We were all of us rather afraid of Richard," she confessed. "He was older than the rest of us and not a regular student. He was just rubbing up biology and he used to sneer at the lecturer. He thought it funny to say hurtful things."

"Why didn't you kick him out?"

"Because, in a way, he helped to make the thrill. He seemed a sort of distorted genius. Besides, to be honest, we wanted to meet at his house. He lived with a wealthy uncle and there were always refreshments and drinks."

The marble pillars and gilded walls of the hotel lounge faded out as Ann thought of the last session in the tower-room. She remembered the roaring wind and the trails of ivy which tapped on the window-panes.

"We'll hold a reunion here, seven years from to-night," declared Richard. "By then, my old uncle should be hanged and I shall be lord of the manor. Possibly one of you may be successful, and damned, but I promise the rest of you jobs. Something in the Hercules tradition."

"I bar elephant-stables," said one of them. "Otherwise, count me in. Already I feel a man with a future."

Of course it was Stephen who spoke—Stephen who was merely amused by Richard and whose laughter could extract the sting from the most envenomed remark.

As Ann lapsed into silence, the Manchester man's interest deepened into a vague sense of responsibility. The hotel was large, central, and gave excellent value. It was termed "cheap and popular," so it attracted a mixed collection of guests, among whom were some cheap and popular gentlemen. The Manchester man had noticed that while some of these had tried to get acquainted with Ann, she seemed unaware of them, as though she were preoccupied with an exclusive interest.

"Have you kept in touch with any of 'THE SULLIED SOULS'?" he asked.

"No," she replied. "I've been abroad and lost touch. My father died at the end of October."

"How very sad," he said, shocked by so recent a loss.

"Not for him." Her voice was level. "It was one of those illnesses you're thankful to be out of...At the time, it seemed impossible to keep my date. Every one told me so. But I went on trying and haunting agencies and bribing people. And then, almost at the last moment, I got a cancellation in an air-liner. A palmist had told the man there would be a terrible accident."

"So you're not superstitious?"

"But I am. I was expecting the crash, all the way, but I just hoped I might be lucky."

"Used to flying, I suppose?"

"No, it was my first trip. It was awful. Whenever we dropped, I left my stomach behind me, up in the air...But it was worth it for it was quick. I made London with time in hand."

Again the Manchester man wondered what object had exacted such furious drive and fixity of purpose. Then he calculated the girl's age as twenty-three while he counted the number of the "Sullied Souls."

"You've mentioned five names," he said casually. "You make six. Wasn't there a seventh member of your club?"

"Yes. Stephen."

The radiance of her face told the Manchester man why she had flown to England.

"Stephen was wonderful," she declared. "He had everything. And he gave out all he had."

Then she looked at her watch, pressed out her cigarette and began to collect her belongings.

"Nearly time to dress," she said in a different voice. "I've been boring you but you asked for it. I thought talking about it would help me to realise it, but I can't. I can't believe that in a short time we shall all be together again, after seven years."

"Don't go," urged the Manchester man. "Wait for the postscript."

His kindly face had grown grave as he fumbled for words.

"Suppose—Are you sure the others will remember the date?"

"Of course." Her voice was confident. "They couldn't forget."

"Well, my dear, I'm John Blunt. And I'm a grandfather. Will you take some advice from an old-stager? Just ring up this Richard and make sure that it is a date. Remember, you're not used to the black-out."

Ann's face was thoughtful as she considered the advice.

"I can't ring up," she said. "It's unlikely that Richard would answer the phone and I can't leave a message. No one must know of our meetings. Secrecy was one of our vows."

"Hum. What's the address?"

"Ganges, Yellow-forge, Surrey. The house is right out in the country, at the end of the Tube. A local bus passes the gates."

While the Manchester man was jotting down the details, he asked another question.

"What time do you expect to be back?"

"Not much later than one-thirty. We used to catch the last train."

"Well, I warn you, if you don't show up, I shall make inquiries about you. I don't like to see a young girl running risks."

"What risk?"

"The risk of a big disappointment, to begin with. You've not seen these folks for years. They're bound to be changed and you may be disillusioned."

"I know...But it's my chance. I've got to get in touch with someone again. This is the only way."

Pushing back her chair, Ann rose from the table.

"Good-bye," she said. "Thank you for everything."

The Manchester man watched her progress through the lounge. She seemed to steer a way amid the crowd by instinct, for she looked ahead as though she were seeing one face only, smiling at her at the end of a long road.

He grunted and then slumped back in his chair as he began to revise his engagement list. Presently he was joined by his wife—a massive woman with a pleasant face. She had accompanied him to London for the trip and also to keep an eye upon him.

According to custom, he told her dutifully about his promise to Ann. His story got the usual reception, while she hid her pride in his unselfish character.

"Just like you, Will. Even more daft than usual. I've no patience with headstrong girls who run into scrapes and expect other people to get them out. You've a heavy day to-morrow and you need the sleep you can get. You might consider you owe your loyalty to me and the girls. Besides what you propose is utterly useless."

"Why?" he asked.

"Because if she runs into danger, by the time you could take any sort of action, it would be too late to save her."

Ann's heart beat fast as she rose in the lift up to the fifth floor. It was difficult to believe that somewhere in the blackness of the countryside was the dark pile of Ganges—the focal point for six sentimental pilgrims. Her search through a postal directory had established its existence and also the fact that its owner was still Sir Benjamin Watson.

"No stable jobs for us," she chuckled. "I'm glad Richard has not cashed-in."

When she reached her room, it was still too early to start, so she lay on her bed and smoked while she recalled the journey out to Ganges. The Sullied Souls always met at Piccadilly Circus Underground Station, where—after a race down the escalators—they crowded into the first train. Every one talked and nobody listened as they shouted across the carriage, swaying from straphangers and treading on the toes of other passengers.

Afterwards came the interlude of the bus ride through dark lonely country lanes—so dimly visible in the rush of light from their window, that they seemed to be on a ship, ploughing through cold still waters in search of adventure.

High up in her hotel room, Ann watched the smoke curling from her cigarette as she thought of her companions. All had one thing in common—the name of an English king or queen. Isabella was doubly royal, since her first name was "Mary."

"Stephen, Richard, Victoria, Ann, Isabella, James and John," recited Ann.

James was pale, rather fleshy and smooth-haired. He wore thick glasses and in spite of his youth, his clothes suggested a prosperous professional man. Victoria had an oval expressionless face, black almond eyes and a straight fringe. Her hands were strong with square-tipped fingers which repelled Ann because of Victoria's passion for dissection.

These were the two students who always got the highest marks in examinations, but Ann credited them only with brains which could register degrees like a gas-cooker. Their useful glow was incomparable with the brilliant fire of other Souls. She regarded Isabella as a genius, even while she chose perversely to concentrate on the development of her personality.

She reminded Ann of a picture she had seen of a fatal light which lured benighted travellers into a bog. Behind the flame was lightly sketched a face of unearthly beauty and allure. Isabella had similar delicate features—the same fastidious lips and elfin gleam in her eyes. She was provocative, impersonal and elusive—attracting masculine homage only to reject it.

John was her opposite number—an arrogant golden youth, fair, fascinating and unstable. He assumed the devilry of a Mayfair playboy and dissipated his talents in versatility; but Ann was too dazzled by his personality to be critical. In her deep humility, she worshipped both John and Isabella with the gaping admiration of a tourist in a hall of immortal statues. She expected no notice from them and she received none, but their indifference could not hurt her because she was deeply in love with Stephen.

At the age of sixteen, she concentrated upon him the force of a strong and steadfast nature. Sitting silent at the meetings, she used to watch his face and treasure his words. She retained vivid memories of the way his hair grew and the clean-cut corners of his mouth. Unhappily, she felt so sure that he must be in her life forever, that she never dreamed of any parting.

The news of the family departure to Burma left her stunned with shock. At the time, she was too bewildered with the rush and too modest and doubtful of his interest in her, even to write him a note of farewell. Her only consolation was the prospect of her return to England and the hope of meeting him again.

As years passed and she remained in exile, she tried to obtain his address, only to meet with repeated disappointments. Letter after letter returned to her with a faithful instinct which rivalled her own loyalty. But whenever she felt loneliest, she looked at the ringed figures in her calendar...Every thought and every action led up to a date.

And that date was to-night.

She jumped off her bed, drew a fur coat over her suit and pulled a discouraging little hat—sold to her as the latest fashion—over one eye. A few minutes later she was on her way to the reunion, sinking downward in the lift and pushing through the crowded vestibule. She carried a gas-mask and a pocket-torch, but in spite of their reminds of war conditions, she had not realised the completeness of the black-out.

When she had passed through the revolving-doors, the light gradually dimmed until she swung round to face a wall of darkness. While her eyes were still dazzled from the illumination of the lounge, it seemed an absolute eclipse. Presently, however, she distinguished faint gleams from passing traffic and circles mottling the pavement, thrown downward by electric torches. She could see no pedestrians while she heard voices and footsteps, as though the city were inhabited by an invisible race; but as she lingered in the entrance, she collided with a solid body.

Someone wished to enter the hotel. Stepping aside, she stared before her, when she became aware gradually of blurred shapes passing by. They were so dim and formless that they suggested survivors from a prehistoric race, groping in their eternal midnight. But as her eyes adapted themselves to the black-out the scene became more normal.

As she watched it she had a sense of being cheated. When she had looked forward to this moment, she had visualised a pre-war London—the brilliant street lights, the changing colours of advertisement signs and the glowing façades of theatres and cinemas. It was a keen disappointment and made her apprehensive of the future.

"I expect they are all waiting for me in the Underground," she thought hopefully.

The station was only a few yards from the hotel and she crossed the narrow street in a reckless rush. As she was stumbling down the steps of the nearest entrance she saw the light of the booking-hall around the corner, as though in fulfilment of her dreams. Instantly the years were forgotten and it seemed only yesterday that she hurried down the subway in her eagerness to meet her companions.

Breaking into a run, she burst into the hall, expecting to hear her name called by a familiar voice. When no one claimed her, she paused to look around her. After years spent in solitude, she got an impression of confusion and haste. Every one appeared to be in a hurry to get home. On that evening, there were only a few loiterers and there seemed to be no friendly reunions.

Standing in their usual place she looked at the clock.

"It's the time we always met," she reflected. "I'd better stay put."

As the minutes passed, she grew too impatient to stand and watch the constant stream of passengers, so she went in search of the others. After she had completed the round of the booking-hall without meeting any one who resembled a Sullied Soul, she felt chilled with fresh disappointment.

"Perhaps we've passed without recognising each other," she thought. "I wonder if I've changed much."

She tried to stare impersonally into a strip of mirror at the back of a shop window. It reflected a tall slender girl, wearing a closely-fitting nigger-brown suit under an open fur coat. Her dark hair waved to her shoulders and her eyes glowed with excitement in a pale anxious face.

"Actually I look younger," she decided. "It's the short skirt and the kid hair style. I've lost weight too. But really there's nothing to it. I ought to recognise them."

She told herself that in the course of seven years, no one would grow bald or acquire a stomach of the first magnitude. A girl might change the colour of her hair or a man might grow a beard, but the salient features would remain. She was trying to pierce problematic disguises when she noticed that the hands of the clock pointed to a quarter to seven.

It was the accustomed signal to wait no longer for stragglers but to dash down to the train. Since she had committed herself to a time-table which covered the hours of eight to twelve, it was important to keep to schedule.

Her face dulled as she stood on the descending escalator, since there was no rival Atlanta to race down the steps. Boarding a train in dignity, she managed to procure a seat. In spite of these improved conditions, the carriage appeared a dull place minus Genius and Beauty, to proclaim their opinions, without deference to the corns or ear-drums of the Public.

As she looked around her, the various uniforms reminded her that she intended to get into one of the Services as soon as possible. Crediting her companions with her own patriotism, she considered an ominous explanation for their absence.

"Of course, they've all joined up and can't get leave. Actually I'd forgotten the war. And the war's too big for me to fight. What's the good of going on?"

Even as she weakened, she recalled her dominant purpose.

"I must go on or I'll never see Stephen again. It's my only chance. Ganges is all that matters. If Richard isn't there to open the door. I must get inside the tower-room somehow. I must stay there from eight to twelve, on the chance that Stephen might come to the reunion. If he doesn't come, someone else must remember the date. That person may tell me where to find Stephen."

Then the light returned to her eyes at a further reflection.

"What a mug. I expected them to meet at Piccadilly Circus, when they are all scattered. They will be coming from different stations. One of them might even be coming on this train."

She thought of them set at various points in a circle and gradually drawing together, like the spokes of a wheel, until they met at Ganges. As she smiled, a man—hatless and wearing a belted camel-coat—stared at her as though he interpreted her smile as an overture, but lacked energy to follow it up. He was tall and heavily-built, with a gross handsome face and dull eyes devoid of a spark of spirit.

Ann could not understand her instinctive recoil, until she got a clue from his hair, gleaming under a light. It was very fair and had a strong natural wave. She knew that she disliked him because it was too easy to imagine him as a slender blond youth with a clear-cut arrogant face and sparkling blue eyes—a golden youth who might resemble John.

She fought the suggestion.

"No. I won't believe it. It's not John. He couldn't have changed so much in seven years...Besides, he doesn't know me. That proves he is a stranger."

She was grateful when the train ran into the open and the reduced lighting of the carriage made it impossible for her to see him clearly; but she was vaguely disturbed by the fact that—while the train grew emptier at every station—he did not leave his seat. When the terminus was reached, as she climbed the stairs, she could distinguish the blur of his light coat in front of her.

After she passed through the screens of the booking-hall, she came out in what appeared to be total blackness. With the exception of some stars, the night was clouded and unusually dark. As she waited, she saw moving lights, rather like the coals of a dying fire, and realised they were the dimmed lamps of motor traffic.

She felt both bewildered and nervous as she remembered that she had to cross the road to reach the bus stop. She was further worried by the recollection that the buses to Yellow-forge ran infrequently and that the Souls used to sprint to make their connection. Although she knew that the timetable was probably altered, she dared not linger outside the tube station.

When she tried to reach the other side, she found that she had lost her traffic-sense completely. After deciding that some feeble oncoming lights were still safely distant, she was about to dash in front of them, when she was arrested by the finding of brakes and a burst of profanity from the driver. At the same time, someone gripped her arm and dragged her back to the pavement. She thought instinctively of the man with the debased face, so it was a relief to hear a woman's voice.

"Don't you know better than to cross against the lights?" it asked.

"No," replied Ann frankly, "I don't."

When she explained the circumstances, her rescuer grew friendly.

"I'm from the Dominions myself," she said. "Australia."

"How lovely," said Ann enviously. "It's daylight there."

"And real sunshine. I'm in the A.T.S. I'll see you across Jordan. Look, there's the amber. The lights are going to change. Now."

Armed by the friendly Australian, Ann crossed the road safely and was steered to a darkened vehicle which was on the point of starting.

"Yellow-forge bus," said the uniformed girl, pushing Ann up the steps. "Good-bye. Happy landing."

As the bus moved on, Ann congratulated herself on her progress. The most difficult part of her journey was over as she would alight just outside the gates of Ganges. When the conductress came to collect her fare, she remembered the name of the stage—King William the Fourth—a small public- house.

After she received her ticket she was able to relax. Her watch told her that she had time in hand, even if she had some difficulty in locating the tower-door in the black-out. She could see nothing of the countryside, but there was the old sense of adventure—of being on a mystery cruise over some fabulous sea—as the darkness flowed past.

"Every yard, every second is taking me nearer to Stephen," she thought.

Conscious that she was growing sleepy from the strain of peering through the gummed muslin which protected the window, she looked down the dimly-lit vehicle.

To her dismay, the seat in front of her was occupied by the big fat man who was a caricature of a mature John. She stared at the roll of fat on his neck and his thick wavy hair while she tried to subdue her panic.

"It's not John. He's not going to Ganges. It's just coincidence he's on the Yellow-forge bus."

Unfortunately the shock of seeing him had awakened all the latent fears which the kindly Manchester man had sown in her mind. She began to wonder whether Ganges existed only within the pages of the telephone directory. After every blitz, houses remained listed, although they were reduced to rubble. Presently she could endure the suspense no longer and appealed to the conductress.

"I want to get out at Ganges. Will you please tell me when we come to it."

"Ganges?" repeated the girl doubtfully. "Do you mean the Zoo?"

A submerged memory returned to Ann. Although she had never seen Ganges by daylight, Richard had boasted about his uncle's collection of wild animals. It was a modest one, comprising varieties of deer, a small cat house, a monkey colony and a penguin pool, yet it was a source of heavy expenditure.

"Big Ben's spending a fortune on the blighters," grumbled Richard. "He's trying to reproduce their natural surroundings, to kid them they're not in captivity. It suits me as I've got my hoof well in. There's a tribe of relatives—pedigree and mongrels—but I'm the only blighter that's up in zoology. The idea is I'm Big Ben's heir, on condition I keep on the Zoo."

As she remembered the explanation, Ann accepted the existence of the Zoo as comforting proof of the survival of Ganges.

"So the Zoo's still there?" she remarked as a feeler.

She realised that she had introduced a controversial subject when a big shapeless woman who resembled Mrs. Noah, spoke sharply.

"Yes, still here, but it wouldn't be if it wasn't a rich man's hobby. It's a proper scandal and it didn't ought to be winked at."

"Hush, Ma," said a girl's voice. "It's no business of ours."

"Maybe not, but I speak for others. What about young Perce?"

An invisible man, sitting further down the bus, defended the Zoo.

"Sir Benjamin's all right. Hasn't he promised to give a Spitfire? He can spend his money as he likes. Young Perce had no business to climb railings. He was trespassing."

"The poor lad said he lost his way in the dark—and he had to deliver."

"He should have delivered his groceries by daylight. He was a darn fool to go wandering about the grounds in the black- out."

"You're telling me," agreed the matron. "You wouldn't catch me in there, not if the king asked me to meet him. You might stumble against anything in the dark."

The conductress interrupted the discussion by ringing her bell.

"Ganges," she announced. "Take care, miss."

As she got up Ann glanced apprehensively at the back of the big fair man, but to her great relief, he did not rise from his seat. Evidently Ganges meant nothing to him. He was still motionless when she looked after the bus, rolling again on its way.

"Thank goodness," she muttered. "That's the end of him."

Snapping on her torch, she saw before her the familiar entrance to Ganges, where stone pillars were crowned with roughly-carved elephants. On one post a notice was displayed—"WARNING. PRIVATE ZOO. KEEP TO PATH."

She felt a thrill when she pushed open one heavy wrought-iron gate, Stephen was only just around the bend. But even as she exulted, she started at a low noise. It was distant—yet it seemed to stir the air—a heavy sawing sound with a shattering quality—like a snarl imprisoned in a roll of thunder. For a moment she thought it was a train coughing in a tunnel, but as it was repeated she recognised it.

It was the roar of a lion.

In that moment, her courage died and she turned to run. The gossip in the bus acquired a double-edge as she realised that the Zoo was no longer the Garden of Eden of seven years before. It contained savage beasts which were controlled by human agency...And it was admitted that the personal element is fallible.

A few steps across the road would bring her flush with the little public house which was a fare stage. Common sense urged her to catch the next bus back to the tube terminus. It would stop by the station entrance and from there, it was almost a straight run back into her bedroom at the hotel.

As she hesitated, she remembered one of the rare occasions in the past when Stephen had seemed aware of her existence.

"Promise me you'll never meet Richard alone, or go to Ganges without the gang," he said earnestly.

"But you're pally with him," she reminded him.

"Different for me. I cultivate him because he's such a clever devil. He's a sadist and he talks a lot of smut, but when I've chucked out the husks, I can usually get a grain of something useful from him."

He added abruptly, "Don't be impressed by the parrot-talk you hear at Ganges. There's nothing to it. The monkeys at the Zoo can put on a better show."

At that moment she felt the force of his warning. But the memory had reminded her too vividly of Stephen. After waiting seven years for this evening, it would be contemptible cowardice to turn back. All she had to do was to obey instructions—"KEEP TO PATH"—and she would be safe.

When she flashed her torch before her, she was relieved to see that the way was marked with whitened stones. She was surprised to find it unchanged—going uphill and into hollows—because the gossip in the bus had led her to expect altered conditions. When she left England, Sir Benjamin Watson was not only wealthy but he had expectations from a millionaire uncle who was being kept alive, in spite of the total loss of his faculties from senile decay.

The fact that Sir Benjamin had given a Spitfire to the nation seemed to prove that he had come into his inheritance and was now a very rich man. In the circumstances, it seemed strange to find no improvements in the property. Ganges was built on rough rising ground and its natural features were preserved without any attempt at landscape-gardening. There was a ravine, a wood, a lake and a hillock, while the house was reached by a path which climbed a humpy pasture.

Soon Ann began to regret the absence of a properly-made drive. Whoever was responsible for blazing out the trail had apparently assumed that strangers were as familiar with the scene as himself. In places the number of stones was skimped and the white paint had worn off so many that it became difficult to keep to the path. She felt ruts underfoot and blundered into a bush which blocked her way, only to find on the other side a field of coarse grass, unbroken by any track.

As she stopped to plot her course she thought of the unlucky errand-boy who had lost his way also. Her presence was unauthorised—even as his—and she must accept any consequence of trespassing on forbidden territory.

"Go on?" she asked herself. "Or go back and try to find where I went wrong? But Perce climbed palings, so the big idea would be to avoid short-cuts...I'll go on."

She had hardly made the decision when she found her way blocked by a strong stockade.

"Palings," she said. "Definitely this is where I go back."

While she stood there she heard voices on the other side of the enclosure. They were too far away for successful listening- in, but she got the impression of an argument. One voice sounded so blurred and stupid as to be unhuman; it seemed to protest against some course while the other voice urged encouragement.

Suddenly she managed to distinguish words. "All right...Come on, old man...Sleep it off...Soon be all right."

"Well," she reflected, "if one of them is Caliban, the other appears to be civilised. If I could make him hear he might direct me to the tower door."

Before she could cup her mouth something blotted out the stars in the patch of sky before her—something long and sinuous that writhed in the air like a serpent.

She recognised it as an elephant's trunk and turned to run. Had it been daylight, she would have felt no fear, but the darkness turned any encounter into a risk of being crushed. Mrs. Noah, in the bus, had declared that you might stumble upon anything. She realised that the country people were strongly opposed to the Zoo and that probably they had good reason for their indignation.

Although the monster was on the other side of the palings, those blurred voices had destroyed her confidence. If a keeper were drunk, he might leave a gate open, so that the animals could wander over the pasture. Flashing her torch before her she stumbled wildly down a slope, until the light shone on a line of uneven white stones.

In her fright she had forgotten the reunion and the tower- room. With a shock of surprise she found herself in a small paved courtyard which seemed familiar. There was a sundial in the centre and a damp flagged path led up to a small lancet-shaped wooden door.

It was the entrance to the tower-room. When she turned the handle she discovered that it was unlocked, as though in expectation of guests. She entered a dark lobby and stood at the foot of the winding stone stair, listening for the sound of voices from above. In the old days one always heard the excited hum, like grasshoppers on a hot day. But now the only sound was a distant elephant's trumpet—high and thin as though it were calling a retreat.

A rush of questions hurtled in her mind. Was any one waiting up in the tower? Who would it be? Stephen—or Richard, against whom she had been warned? When she remembered the myriad times she had looked forward to that moment, it seemed ironic that she actually feared to mount the steps. At last she found the courage and crept upwards, straining her ears for any sound that might warn her of danger.

As she reached the last spiral she saw a beam of electric light shining from the tower-room. This was contrary to precedent, for their meetings were lit only by the flames from a coal fire. As she saw the place distinctly for the first time, its glamour was destroyed with its loss of mystery. It was smaller than she had imagined, with blacked-out windows set high in the walls. There were the same shabby divan and chairs which were never occupied, since they preferred to sprawl upon cushions piled before the fire. The table at the back which used to be crowded with bottles and heaped plates now held only a decanter. The grate was empty and its coals replaced with electric- current.

Someone was sitting slumped in one of the deep chairs. He rose as she entered and held out an unsteady hand. It was a big fair man—her fellow-passenger in the train and bus.

"Hallo," he said. "Who are you? I am John."

THE shock of the encounter was so heavy that it left Ann stunned and incredulous. She felt she was in a nightmare where the dreamer has only to dread something to make it happen. If she had not traced a debased likeness to John in her fellow- passenger, this impostor would not have crashed his way to the reunion.

Her confusion was increased by the fact that she could not account for his presence. The last time she had seen him, he was half-asleep in the bus, rolling on towards Yellow-forge. She was positive that no one had followed her through the gates of Ganges. Yet the litter of cigarette ash upon the table was proof that he had been smoking in the tower-room for some time before her own arrival.

He typified the unwelcome change which the Manchester man had warned her to expect. Since she had begun her journey everything had been different. She had met with new features, each of which held a certain degree of horror; the black-out, the roar of a lion, a drunken mumble of protest—all these led up to this crowning disappointment.

It was in vain that she tried to thrill at the knowledge that she was actually inside the tower-room—the scene of her happiest memories. Only by closing her eyes could she see it again in the leaping firelight which lit up youthful faces and accentuated the mystery of the shadowed background...Now it was stripped of glamour as the crude light glared down on it, exposing its bare discomfort and revealing the inflamed face of the fair stranger.

Instead of answering his question she unzipped her bag and drew out a dog-eared grubby card which she laid on the table.

"There's some mistake," she said coldly. "You are a stranger to me. I've come here for a reunion. Here's proof of my identity."

Instead of showing signs of confusion, a slow smile spread over the impostor's face. After fumbling in his wallet, he slapped down a similar card over hers, like a child playing "Snap."

"This is wizard," he said. "Someone's remembered the jolly old reunion. But who the hell are you?"

She gazed steadily into his dull eyes.

"You couldn't remember me," she told him, "because you are not a member of our secret society. You don't know our names and you never knew them. So it can mean nothing to you if I tell you I am 'Ann.'"

"Ann?" he repeated stupidly. "Ann was the silent kid who never giggled or flirted. No, you're not Ann. You're trying to put a fast one over me because I'm tight. But I've seen you somewhere before...Give me time. Something's going to click here."

He touched his head and then snapped his fingers.

"I know. You're the girl in the train. You tried to get off with me. Sorry I couldn't follow it up, my dear. Another engagement. This...But you've no business here. I know you are not Ann."

"And I know you've stolen John's card. What have you done to him?"

The man ignored the charge as he stared at her with puzzled eyes.

"Actually I believe it is Ann," he said after a pause. "I'm beginning to recognise bits and pieces. It's Ann grown into a beautiful lady like the advertisement...What soap is it? I forget...But it's our Ann. Come to my heart."

Before she could protest, he crushed her in his arms and began to dance but after a few staggering revolutions, he released her and dropped into a chair.

"Sorry," he apologised, "can't keep an even keel. Room's too small...Ann, I've always wanted to meet you again, to ask you something. It's been biting me all these years...Remember our last night when I kissed you in the bus. Instead of biffing me, like you used to, you let me. It was like kissing cold fish...Now that was out of character—and I've often wondered why."

Ann dared not trust her voice to speak. In that memory John had given her positive proof of his identity.

She remembered how she had hoped that Stephen would sit beside her in the bus, on their homeward way, but John was first to slip into the vacant seat. Her disappointment was so keen that she was dead to sensation and had been scarcely conscious of the kiss.

As she remained silent, John picked up his card and began to re-read it.

"Insulting tripe," he said. "Typical of Richard. Remember his stable jobs? Joke is, they've got elephants now. Actually they have everything. The old man's potty on his zoo. Gives the animals a home from home, on the model of a happy Christian family; mister, missus and Tertium Quid."

"I wonder Richard isn't here," remarked Ann dully. "Perhaps he's forgotten."

"He had forgotten all right and so had Isabella. I was the faithful hound who remembered. Touching, but I loved those old days. But when I reminded Richard of the reunion he was quite keen. Hopes to gloat over our failures. Remember this register?"

He fumbled under his evening paper which was thrown upon the table and produced a double sheet of stiff paper. It was yellow with age and bore seven signatures.

"It's the roll call he made us sign our last evening," explained John. "His idea is we all sign on again. Evidence of attendance at his reunion, in black and white...Now watch me sign on the dotted line. Darling, which of them is the dotted line? Just guide my hand to the starting-post."

While he was scrawling with an unsteady hand, Ann looked over his shoulder at the list of names. At the sight of one signature, she forgot her first disappointment and was glad of John's presence. She realised that he might be able to give her news about Stephen; but because she dreaded his ridicule, she made an oblique approach.

"Have you kept in touch with any of the Sullied Souls, John?"

"All of them," he replied.

"Oh. Have they changed much?"

"Only in spots. Richard and Isabella are the same—only more so."

"I'm glad Isabella is still beautiful. Did she have a career?"

"Someone else's. She married and scoops in the dough. Victoria is a doctor. Got a practice up north. She had an Old Age Pension, looking after Big Ben's old uncle—but he died on her...Poor devil. Fancy having to die, looking at that."

Ann's heart beat faster. She was getting nearer to Stephen's name. Only one other Sullied Soul blocked the way.

"James?" she inquired.

"He's a prosperous bloke. Lectures and coaches in biology, plus sidelines."

"And Stephen?"

"Who's he? Never heard of the chap."

The check was so unexpected that Ann felt as though she had run into a brick wall.

"You must remember Stephen," she insisted. "He was leader."

"No," corrected John. "Richard was leader."

"But Stephen was leader of the opposition. He never let Richard get away with anything."

"Oh, that blighter." John blew out his cheeks. "I'd clean forgotten him. He was a dirty spoilsport. He never let any of us make a pass at you."

Ann was sidetracked by her own astonishment. Her inferiority complex had caused her to worship her companions in silence, but she had no idea of the attraction of her youthful gravity, founded on experience. While the others shouted their views on those subjects which are dealt with adequately in realistic novels, she, alone, had first-hand knowledge of poverty, alcoholism and the symptoms of certain unadvertised illnesses.

"I can't believe you," she said. "No one would want to make a pass at me. I was so stupidly young."

"That was the attraction," chuckled John. "You were young. We only had the other girls to get you."

Although she felt sure that he was lying, it thrilled Ann to hear that Stephen had acted as her guardian angel.

"Haven't you heard anything about Stephen?" she persisted.

"No," replied John. "He just dropped out. While we are waiting, what about a spot?"

It did not need a specialised knowledge to tell her that John had already drunk more than he could carry. She caught his arm before his fingers closed around the decanter.

"We must wait for Richard," she said. "If we don't we are giving him a swell chance to insult us...Tell me about yourself. What's your work?"

To her relief he swallowed the bait of her assumed interest.

"I'm a journalist," he replied.

"That's brainy. Are you married?"

"Yes, if you can call it that. I've certain matrimonial privileges. I feed a lady with expensive tastes and I pay her dress bills. Another chap gets all the rest. That's modern marriage...Ann, I could kill that other chap."

"Why don't you?"

"Because I can never keep track of him. He's always a different chap...Ann, I'm going to ask you something and I want a straight answer...Why didn't you recognise me?"

"If it comes to that, why didn't you recognise me?"

"Because you've grown into a glamour girl. But I can't see how I've changed. I look the same in the glass. Filled out a bit, of course, but my hair's still thick and I don't give at the knees. Last time you saw me what was I like?"

"Like a young Greek god."

Directly she spoke, Ann regretted her words because of the misery in John's eyes.

"Don't know any gods," he said with a forced laugh. "They're not in my street. But I get the idea. No pubs in Elysium. That what you mean?...Actually, I can't write unless I'm boozed and I have an expensive wife. Disgusted?"

"Of course not." Ann felt a rush of sympathy. "I'm only sorry. Can't you shake out of it?"

"Actually, I could. Nobody would believe this, but really I am a domestic chap. I want a home and kids. And I could have them, even now. There's the right sort of girl in my life—a girl who would pick up my bits and make them into a man. None of your cock-eyed gods."

It was characteristic of Ann to go to the point.

"Can you get a divorce from your wife?" she asked.

"Definitely," John assured her. "Any number of them. Actually I'm too weak to make the break. I've got her under my skin. That kind of hold."

"Still, I wish you could. I'd like to think of you with a happy ending, John, because of those old days."

She realised that her sympathy was a mistake when John began to gulp. To stop him from becoming maudlin, she asked him a question.

"How did you get here before me? I left you in the bus."

"I baled out about half a mile further on. There's a new entrance now—a short-cut to the house, all uphill and up steps."

As he explained, John drummed with his fingers on the table and glanced pointedly at the decanter.

"What do we do now?" he asked.

"I stay here until twelve," Ann told him. "I want to meet the others."

"If I hunt round I might produce Richard and Isabella. You can wash out the rest. Too far for Victoria to come out of sentiment, for she's got none. And there's no money in it for James."

"There's still Stephen."

"That bloke again? He's dead. Must be. There's a war on. He's either one of the Few or one of the Great Majority. Same thing in the end."

"No, he's not dead. I know he's alive. He must be."

John stopped drumming the table and looked at her with troubled eyes.

"It's getting plain to me why you've come," he said. "Ann, do believe me. It's a hundred to one chance you will meet him here. Take my tip and go—at once—while the going's good."

"Why?"

"You may well ask. Do you remember Richard's hooded look?"

Ann nodded as she remembered how occasionally Richard seemed to withdraw himself completely behind the shutter of leaden drooped lids. At such moments she felt acutely apprehensive and prayed that she might never see his eyes lest they revealed too much. She still felt chilled as John went on speaking.

"I bumped into Richard outside, on my way up. He was running like hell—and he had his hooded look...That means it's not safe to hang around. It means that things are going to happen. And when things happen he doesn't want people there to see them happen. If they did catch on, well, it might be too bad for them...Got the idea?"

"Yes. You're trying to make me windy. But it's childish. If Richard were a criminal lunatic, he'd be certified. Besides why should he pick on me to attack, especially here with people round? He has no interest in me, one way or the other."

After a struggle, John managed to rise from his chair. He lurched to the door—listened—and then closed it.

"You've forgotten one thing," he said. "Richard is in control of this outfit and he's got a queer sense of humour. He's got us to come here on the Q.T. Don't you think a Zoo rather a loaded toy for him to play about with?"

Although Ann remembered her fright when she blundered up against the elephant-house, she summoned her common sense.

"The animals are all safe in cages," she said. "Are they specially savage?"

"Good grief, no. Tame as kittens. Richard and the old man take them about on leads, like dogs. They're bred in captivity and used to private baths and bedside telephones. But my point is this. They can be frightened. Suppose any one threw a lighted cracker when Big Ben was passing with one of his kittens, what price his control then?...Ann, go back before you meet Richard again. He's out of your life. For the love of Mike don't let him in again."

Ann smiled at him as she shook her head.

"John, you're rather sweet," she told him. "But get a load of this. I've come to the reunion. That stands."

He looked at her firm lips and his own trembled as though he regretted the contrast. Seeking consolation his hand moved towards the decanter but he drew it back again.

"If it's like that with you," he said, "I'll find the others."

She guessed his objective was to find a drink elsewhere, but she watched him go with a tolerant smile. While she felt she was unqualified to judge him without knowledge of the facts, she was filled with anger when she thought of the woman who had exploited his weakness.

"If ever I meet his wife," she thought, "I'm bound to tell her she's a stinker."

It was a relief to be alone and without John's presence as a reminder of destructive change. As she looked around the tower-room, she decided that some of its past charm could be restored.

"Actually it's the same except for the fire," she reflected. "I never saw it properly before, so I imagined it. That's all there is to it. I'll fix it."

Zealous as an A.R.P. warden, she mounted a chair and drew down a shade of dark-blue crinkled paper which had been rolled back. It shrouded the bulb and reduced the illumination to a funereal gloom, only relieved by the radiance of the electric fire. Once again there was shadowed mystery as the walls shrank into invisibility, like pimpernels closing before the threat of rain.

Brooding alone in the warmth, Ann recaptured some of the spell of the past. It seemed to her rather like a miracle to be actually back inside the tower-room. All that had happened that evening was but the prelude to the real adventure. A few false notes had been struck and the limiting had been too strong—but such slight hitches would be forgotten when the curtain rose.

Her tranquillity was suddenly shattered by a low rasping sound. It was not a roar, but rather like a purr which thickened intermittently to a snarl, as though in hint of underlying menace. She could not locate it, but it seemed to be everywhere at the same time—above, below and all around her—throbbing on the air like a fevered pulse or a distant gong.

"It's near," she thought. "Close to the house. Or even inside."

In the silence that followed, her imagination broke loose from her control and ran wild. She had a horrible suspicion that Richard was indulging his cankered sense of humour and unleashing a tigress to act as lady-receptionist at the reunion.

"He always hated Stephen," she thought. "Suppose he's planning for him to walk into a trap."

Without care for her own safety, she opened the door and stood on the small landing, gazing down into the well of the circular stair. It was too dark for her to see the lobby at the bottom but she heard someone coming up the steps. Her heart beat faster as she listened, because the footsteps were those of a man. They were too steady to be John's, while Richard was unlikely to use the outside entrance when a door on the landing led to the main staircase of the house.

The inference was a choice between James and Stephen—a fifty-fifty chance.

Hope flared up—to be killed by bitterest disappointment. As she threw the light of her torch downwards, it gleamed on black shiny hair on a flat head which reminded her vaguely of a snake...Once started, the reunion was continuing to function. Within a few seconds she would be linked up again with its sinister promotor—Richard.

While she waited she grew conscious of miserable seeping fear. It was inexplicable in the light of past experience, when her father had declared—in hackneyed phrase—that she had not a nerve in her body. Although she was not so immune as he boasted, during some narrow escapes, she had contrived the impression of thumbing her nose at danger.

As she stood on the landing, she realised that she was missing the stimulus of motion. When she was chased by a grizzly—and when her canoe was drawn into rapids, thundering towards the lip of an abyss—she had been sustained by the heat of excitement. She had to run—to fight; but it was a cold-blooded business to wait and listen while the footsteps wound around the spiral.

With an instinct to protect herself, she flashed the light in Richard's face when he was a few steps below her. It was evident that he mistook her for someone else, for he whispered with savage exultation:

"It's all right. By now—he must be dead."

With an instinctive dread of turning her back upon him, Ann receded before his advance into the tower-room.

"Why this dimness?" he asked harshly. "It seems someone has a sense of dramatic values...Stop flashing that light in my eyes. I know you are not Isabella. Who are you?"

"Guess," said Ann, snapping off her torch.

As she looked at him under the shaded bulb, her first impression was that he had kept a tally of the years in his face. It was so seamed that, in the dim light, he was not unlike a painted brave. She noticed too that he was possessed by some violent excitement. His pallid skin glistened and there was a curious greenish glare at the back of his eyes. He carried with him a strong sweet perfume as of a funeral wreath.

"You must be Ann," he said, changing his corncrake note to his most charming accent. "And a very lovely Ann. Growing-up has suited you better than some of us. Do you remember how you used to call John a golden boy?"

"Yes," she agreed. "He and Isabella made a perfect pair. A golden girl and a golden boy. I used to hate you when you would quote that bit about them turning to dust like chimney- sweepers."

"Actually I was prophetic. But I haven't welcomed you to our reunion, Ann."

As he held both her hands within his moist palms, the artifice of his stiff grin made his face resemble a vulpine mask.

"I hoped you would come," he said, "to renew old contacts and happy memories. It will be instructive for you to realise what time can do to us. You really must meet John."

"I have," she said curtly.

"Then I am sorry I was not there to re-introduce you. I think that covers everything."

In the old days Ann had been too overawed by her brilliant company to challenge any statement of Richard's. Therefore it was tonic to her self-respect to realise that, in her case, the years had brought courage with clearer vision.

"He seems to have been unlucky in his wife," she remarked.

Richard cackled softly as he picked up the register from the table.

"I see John's characteristic signature is here," he said. "Will you sign, please. I don't want to think I have dreamed you when I wake up afterwards."

When she returned the paper, Ann was ashamed of her scrawl which was as shaky as John's. Conscious of Richard's smile, she tried to explain her nervousness.

"Any one would think I was a hard drinker. Actually I'm so terribly excited about the reunion."

He glanced at her keenly before he spoke in his grand manner.

"I am flattered that my wish to reassemble you all has met with so much response. You must admit I fed and wined my disciples in lavish style. It is natural for me to retain my interest in them now they have passed from my control. Of course, there will not be a full muster. With Isabella, we are four. The betting is no one else will come. But even if one other person turns up, there is bound to be one absentee and probably two."

"That sounds like you," said Ann boldly, forcing her laugh. "You want to crab the reunion in advance. But I am counting to meet every one—or our meeting will be spoilt."

"The faithful heart in real life. Very touching...Where have you been all this time and what have you done?"

"Abroad. The unusual things."

"You've developed some definite character, Ann. I am looking forward to your meeting with Isabella. She's used to playing lead. She—"

He broke off when he discovered that she was not listening to him.

"You appear to have extra keen ears," he remarked. "Can you hear any one on the stairs?"

"Yes." The glow faded from Ann's eyes, "But it's a woman."

"Then it's probably Isabella. I must warn her about my uncle. He is very seriously ill."

Richard delayed his return for a little time. Straining her ears with natural curiosity, Ann caught the sound of a woman's voice cut off in a question. As she listened to the buzz of whispers, she wondered whether Isabella were married to Richard. Her presence at Ganges, while Sir Benjamin was so ill, seemed to point to the fact that she was a resident. Ann remembered too that, in the past, she used to annoy Richard by an assumption of ownership.

There seemed no doubt of the identity of their present interests. When the pair entered the tower-room, the same unholy fire burned in Isabella's eyes, as though to welcome a deferred death.

"Are they waiting for Sir Benjamin to die to get his money?" she wondered. A second thought—darkly dramatic—was instantly crushed. "Are they planning to murder him to- night?"

"Meet little Ann," said Richard with a theatrical wave.

Isabella came forward with outstretched hands. She brought with her light, excitement and glamour. The waves of her blonde hair and her silver lamé gown gleamed under the veiled pendant. At first glance she appeared to have grown more beautiful but as Ann looked closely she felt a sense of loss.

The faerie gleam had vanished from Isabella's eyes. Now they were pure wanton while the lines of her beautiful lips were hard. Gone, too, was her mystery and the fugitive quality of her smile. While she might still blind and bewilder belated travellers, they would no longer confuse her with the Flame which lured them into the bog.

"Ann," she cried, "how you've changed. You used to be adorably dignified and reserved—unlike any one else. But now you're typed. You've developed herd-instinct...Darling, it's divine to see you again but I could slay you for spoiling yourself."

As she listened to the ungenerous greeting, Ann felt the surge of her old inferiority complex; but as she continued to look at Isabella she realised that life was repaying its debt. For the first time she faced Isabella on equal terms.

"If I followed my crowd," she said, "I should be wearing a bearskin or a string of beads. But I never went native, although I have lived in some very rough places."

"The country, I suppose? Wales?"

"Alaska, Brazil, Africa, America. And the rest."

"How foul. Didn't you loathe it?"

"Loved it. I got ingrained dirt in my knees. It made me feel so manly."

Richard's neighing laugh was tribute to Ann's nonchalance.

"Ann makes us appear quite small town," he remarked to Isabella. "By the way, she had met our John Cumberland, Esquire. And now she wants to meet his wife. Could it be arranged?"

"Meet her is the last thing I wish to do," flashed Ann. "I couldn't be too far away from her. I've seen what she has done to John."

Isabella's cheeks suddenly flamed under her rouge and her eyes were hostile as she glared at the girl.

"I reserve my sympathy for his wife," she said.

"This is where I come in," put in Richard. "Sorry, Ann dear. I forgot to tell you that Isabella is Mrs. John Cumberland."

The news tested Ann's acquired poise severely and made her feel very young and inexperienced. Her lips trembled as she realised fully the shoddy shrines before which she had worshipped. It was difficult to realise that two hours before she was telling the Manchester man about the glory that was Ganges.

"I'm sorry," she murmured.

Isabella acknowledged her apology with a shrug as she spoke to Richard.

"Cigarette."

Ann noticed that she could not demonstrate her unconcern without the aid of smoke. After blowing a ring, she asked Ann a languid question.

"What about you? Married?"

"No," replied Ann.

"Living with a man?"

"No."

"No personal experience. Good grief, how dull."

Although the shock of meeting Isabella had hurt her more than the change in John, Ann suddenly faced up to reality. She admitted that the brilliant company of the Seven Sullied Souls existed only in her imagination. They were ordinary clever students whom she had sprinkled with star-dust, glorifying charm to beauty and talent to genius.

"Stephen knew," she thought. "He told me not to be taken in by them because they belonged to the monkey-house. They've not changed. They've always been a rotten lot. I've been a sucker. But I've lost nothing, for I never had it."

It was a tribute to Stephen's judgment that he had seen always through their pose of glib phrases—garnished with cheap malicious wit and lacking ideas or human kindness.

"I'm safe now," she told herself jubilantly. "I can't be hurt again. Stephen is the one that matters. I came to meet him."

Richard seemed to read her thoughts.

"I'm not expecting either Dr. Pybus or Professor Short," he said. "Victoria and James to you. They are so professional they would shy at writing 'Zoo-man' in their engagement-book...That is how they visualise me—with a fork and straw—perpetually bedding-down beasts...But I feel sure Stephen will show up."

Although she knew her rising colour would betray her secret to Richard, Ann asked him an eager question.

"How do you know? Have you seen him recently?"

"Very recently," replied Richard. "He looked very fit and all that. R.A.F, uniform, of course. They call him 'Lucky Pardon.' He'll come though."

"Did you mention the reunion?"

"No, but he did. He talked about you. Asked questions and so on. Of course, I couldn't answer them then. But he is hoping to meet you here to-night."

Ann was too dazed with happiness to notice that Isabella was looking at Richard through narrowed lids while her lips formed a soundless word—"Liar." Then to her surprise Richard held out his hand.

"I am so glad to have met you again, Ann," he said in his most charming voice. "When the war is over we must have a real reunion, with a banquet and champagne. But—as things are—I have to ask you to go. We are expecting my uncle's death at any minute. I should be with him now. Good-bye."

THE blow was so unexpected that Ann was staggered. She had been prepared for difficulties and even for danger, but not for a bland announcement—"Not at home."

The door was slammed in her face.

"But, Richard," she pleaded, "may I stay up here? I've waited for this reunion for so many years. I've been cut off from every one—and it means everything to me. I—I can't explain. Please, please. I won't make a sound. No one will know I'm here."

"Trust the servants to know," said Isabella. "And trust them to have a perfectly good dirty explanation. At a time like this one can't be too careful. Richard's the heir—and his relatives are in the house."

"Isabella understands," commented Richard. "All sorts of rumours might fly around. I can't risk people saying I was entertaining a pretty lady in the tower-room, while my poor old uncle was passing out alone."

"But Isabella's here," persisted Ann.

"Isabella is such an old friend that she counts as family."

Ann made a last effort.

"The others will be coming to the reunion," she argued. "If I stay up here, I can explain what has happened and send them away."

"Stephen is the only one who is likely to come," said Richard. "Give me your address and I'll ask him to get in touch with you."

The request sounded reasonable but Ann was suspicious. Although all she wanted was to make contact with Stephen, she knew she could not trust any promise made by Richard. In spite of her simplicity, she got the impression that he and Isabella were playing the same game—and one without rules and referee. Something evil was being planned and the reunion was an unwelcome complication.

She realised too that she had ruined her chance of remaining in the tower-room by letting Richard see her desperate eagerness. He and Stephen had always been antagonistic, so he would welcome a chance to score over a rival. Yet although he lauded deceit as a mental accomplishment and despised honesty as a brainless blundering instinct, he had betrayed himself to Ann by his two different voices. When he disguised his natural grating note with honied accents, he practically advertised the fact that he was telling a lie.

Although her instinct was always to charge out into the open and take on more than her fighting weight, she knew that she must use guile, if she were to meet Stephen again. Even while she hated the necessity she plotted rapidly.

"Pretend to go. Then slip back and wait in the downstair lobby. It's dark there."

To her surprise she discovered that she was a natural liar as she looked at Richard with convincingly steady eyes.

"I haven't an address," she told him. "I don't know how long I shall be at my hotel. Will you ask Stephen for his address. I'll ring you up to-morrow and get it. Good-night."

"Yes, do please ring me up. Allow me."

Isabella stood aloof while Richard helped Ann to put on her coat but her glance was scornful as she appraised the quality of the fur. Then to Ann's astonishment Richard drew from his pocket a creased white scarf. As he opened his light coat she noticed, for the first time, that he was wearing shabby evening- clothes.

It was so unusual that he should dress for dinner, in the circumstances, that her suspicions flared up again. But she forgot them as she discovered the source of the perfume which she had connected with a death-chamber. In the buttonhole of Richard's coat was a crushed white hyacinth.

He noticed her stare.

"Picked it up from the greenhouse floor," he explained. "I'm going to see you off the premises. A zoo is not the safest place if you should lose your way in the black-out."

"No," she protested. "I can follow the white stones. Your uncle might want you."

"I'll risk him. He's taking his time about dying. But I might get into trouble with the coroner if I risked you."

Suddenly Ann thought of Stephen—probably pressed for time and steering a correct course to Ganges by the stars. She remembered one occasion when they caught their last train back to London, only through his flair in finding a short-cut to the station.

Fear for his safety made her confess that she had trespassed.

"I wandered round before I reached the tower-room and I found myself by the elephant-house. I heard voices. I don't want to make mischief but one of them sounded drunk. I hope it wasn't a keeper."

She missed the glance which flashed between Richard and Isabella.

"Thanks," said Richard. "I must look into it. I've taken on a heavy responsibility...Come on, Ann. Back in a few minutes, Isabella."

Guided by Richard's fingers around her elbow—and eager to get rid of her escort—Ann ran down the spiral stair. Directly the tower door was closed behind them she stopped with a cry of dismay.

"It's like the catacombs," she said. "Stop while I get out my torch."

Richard laughed as he took her arm and dragged her on.

"You won't need a torch with me," he told her. "I can see in the dark. Besides I know my way about blindfolded...Just trust yourself to me."

She wished he had not used the words which were spoken in his softest voice. They made her realise that she was deeply distrustful of her guide. She was completely at his mercy as she blundered along blindly, obeying the pressure of his arm.

"I like the dark," he said. "It gives me a sense of power. I feel like the Invisible Man, because I can see others and they cannot see me. But it's a pity you are in partial eclipse, Ann. Of course, you know you've grown beautiful."

His last words were spoken so tenderly that his voice might have been that of a romantic lover. Ann reflected what a shock it would be—after being wooed by Richard in the blackness—when his dark scored face was revealed in a beam of light.

As he went on talking, she made a disturbing discovery. Although they had crossed the flagged courtyard, they were not walking over the beaten earth of the main path. Instead, her feet first crunched gravel and then stumbled over rough grass.

"Where are you taking me?" she asked. "I know this is not the right way."

"It's a short-cut," he replied. "You haven't been here before."

His fingers tightened on her arm and he whispered in her ear.

"Of course you noticed that Isabella was jealous as hell. You have made a great comeback. In future I'm going to see a lot of you. What do you say to that?"

Feeling that some response was expected, Ann spoke without thought.

"I'm thinking about something else, Richard. You were expecting us to meet here to-night. The door was open and the tower-room was lit. You made a register. So what made you change your mind about the reunion?"

"Because, to quote Browning more or less, 'the net hath caught the fish.' I wanted the reunion to pull in one person only. You. Don't you know I've always been crazy about you? Now listen..."

Although his face was touching hers, Ann did not shrink from him. All her attention was gripped by the threat of a new peril.

The path which had been sloping downhill gradually, had become a steep incline. As the gradient grew sharper, she had somewhat the sensation of slipping down a chute. She was forced to quicken her pace to keep her footing, while every fresh step into the darkness seemed to be leading down to the mouth of a shaft. Soon she must run—run faster and ever faster—until her feet shot out into vacancy and she crashed down into blackness. A hideous suspicion flashing across her mind made her scream:

"Stop, stop. You are taking me down to the bear-pit."

"Don't be a little fool," cackled Richard. "I may pay a bear but I do my own hugging." His arm tightened around her as though to illustrate his words. "Now you must trust yourself entirely to me. We are coming to a steep flight of steps. Feel with your feet...That's right. I won't let you fall."

As she was bumped down the treads of an invisible stone stair, Ann began to feel ashamed of herself. Her father's praise—"Not a nerve in her body"—reproached her with cowardice. She felt that even the grizzly was qualified to sneer at her, for allowing herself to be lugged about like a parcel.

"I've made a complete fool of myself," she confessed when they reached level ground. "I felt so helpless, not being able to see."

"I understand," Richard assured her suavely. "Besides, you took a bit of a jolt about Stephen. Too bad missing him...Now we are coming out on the road."

Ann heard the clang of an iron gate closing behind them.

"What luck," remarked Richard. "There's a bus coming in the right direction. Can you see its lights?"

"No, but I can hear it coming."

"Then it's 'Good-bye,'" His voice changed. "We won't kiss, my sweet. You've been putting on an excellent act but you didn't fool me. You made your mistake when you let me make love to you while you are all out for Stephen. Not like you, Ann, and most revealing. It told me all I wanted to know...Here's your Black Maria."

He snapped on his torch for the first time, throwing its light down as he hailed the driver. As he helped Ann into the dim interior of the bus, he spoke in a low voice.

"Don't try to come back. You will find the tower door locked."

AS Ann slumped down in her seat and watched the darkness flicker past the window, she was filled with the bitterness of defeat. In spite of obstacles, she had succeeded in getting inside the tower-room; but now she was outside again—back at her beginnings. To make matters worse, the situation had deteriorated, since there was no longer an open door.

Yet when she remembered his warped nature, Richard's hostile attitude was not inexplicable. While he extracted unnatural pleasure from her disappointment, there was no reason for her to imagine a dark mystery. The inference was that the reunion had clashed with a more important date.

"I'm meant to meet Stephen," she told herself, "or I wouldn't have got that eleventh-hour reservation in the plane. It's up to me to try again."

She appealed to the conductor—no charming girl in grey and blue uniform—but a soured elderly man.

"I want to get off at Ganges. How much?"

"I took you on at Ganges," he objected.

"But I want the main entrance. Please put me down there."

The man punched a ticket, counted some coppers into her palm and then climbed to the upper-deck. Relieved of the responsibility of immediate action, Ann closed her lids. She got no relief—for sections of faces whirled before her eyes like the fragments of a bombed picture gallery; Richard, seamed and malignant—Isabella, in her debased beauty—John, a pathetic wreck. She saw them from every angle—profile, full-face and three-quarter—passing and repassing...

When the conductor came down the stairs, he looked at her suspiciously over his spectacles.

"Didn't you want Ganges?" he asked. "We've passed it. I stopped the bus for you."

Ann remembered the tinkle of a bell, followed by a brief halt, but she had not connected the signal with herself. Instantly she was plunged into panic.

"Stop the bus," she called.

As she jumped from her seat a passenger disagreed with the conductor.

"We haven't come to Ganges yet. Not the main gates. New to the route, aren't you, mate?"

"Not so new as to want you to teach me my business. That was Ganges we passed."

While the men argued Ann did not know which of them to believe. No one else in the bus appeared to have local knowledge, or sufficient interest to give a casting vote. All she knew was that while she awaited conviction the bus was rolling steadily back towards the tube terminus.

"Put me out, please," she said to the conductor.

Feeling that he had scored his point, the man rang the bell instantly and helped her down with a caution, "Mind how you cross, miss."

There was no traffic and she reached the other side of the road in safety; but instead of the stone wall which encircled the grounds of Ganges, she saw a high bank, topped with fenced bushes and trees. They seemed proof that she had overshot her mark, so she turned and began to retrace her steps, in order to reach the main entrance gates.

After a while she grew worried about the feeble gleam cast by her torch and doubtful about its battery. If it failed completely she knew that she had no chance of finding her way back to the tower-room. To conserve it, she snapped off the light and guided herself by touch, walking briskly and hoping to feel the gritty surface of stone, instead of sodden vegetation.

It seemed to her that the bank stretched out endlessly. Brambles caught her fur sleeve, while her fingers grew cold and grimed from contact with docks, fallen leaves and snail-slimed ivy-trails. Presently the darkness made her grow nervous. It seemed strange that—after braving the dangers of savage places—she had come back to the safety of the English countryside to learn the meaning of fear. Yet even while she tried to concentrate on thoughts of Stephen she felt afraid.

She found herself thinking of Hare and Burke, who used to spring on their victims from behind and press pitch-plasters over their mouths. It was a numbing sensation to reflect that—even then—someone might be following her. Richard might enjoy the thrill of stalking human quarry. At any moment, she might feel the grip of hands around her throat...

She forgot her imaginary terrors at the sound of a clock striking in the distance. The three chimes told her that it was a quarter to nine. At the reminder that precious time was running to waste, the tower-room seemed very far away. It was possible that while she was following the course of the bank, Stephen had arrived at Ganges. He could come and go without meeting her. And they would never meet, for Richard and Isabella would assure him that she too had gone and left no address.

Suddenly she realised that she was walking in the wrong direction. She had believed the conductor when he told her that they had passed Ganges, whereas the man who contradicted him had been right. Now that it was too late, she remembered that the main gates of the zoo were opposite William the Fourth. The inn was a recognised halt, so the bus would have stopped there as a matter of course, instead of merely slowing down at the tinkle of a bell.

The inference was that she had got out at some intermediate point and was now skirting another part of the grounds—thus working back to the new short-cut, where she had parted from Richard. It maddened her to reflect that—instead of making progress—she was farther from her goal, since she had to cover the same ground twice. Although she was probably nearer to the steps, she dared not risk trying to reach the house by an unfamiliar route.

Setting her lips she turned and guided herself back by the touch of her right hand sweeping the bank. As she ran she began to wonder what Stephen would do when he found that the door of the tower-room was locked, contrary to the promise of entry. She was positive that he would not come so far without making an effort to get inside. Probably he would ring at the front door in defiance of the secrecy rule.