RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

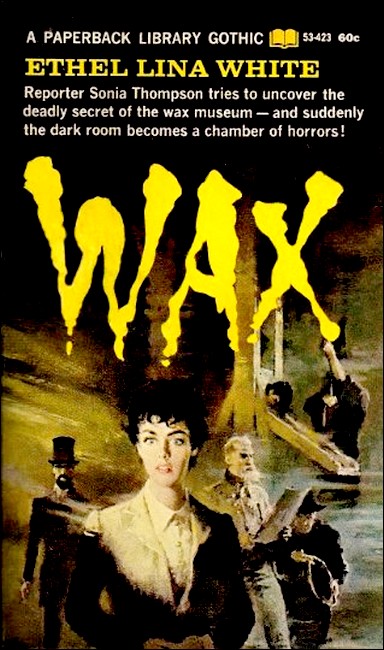

"Wax," Collins, London, 1935

AS the Town Hall clock struck two, the porter of the Riverpool Waxwork Gallery stirred uneasily in bed.

"What's the matter, Ames?" asked his wife sleepily.

"Nothing," was the reply. "Only, I remember taking a candle with me into the Horrors, and I can't rightly say as I took it out again."

Instantly there was an upheaval under the quilt, followed by an eruption of blankets. Then an elephantine hump, silhouetted on the reflected light of the wall, told Ames that his wife was sitting up in bed.

"That Gallery's our bread," she declared. "Besides, think of my poor figures trapped in a fire. You get up, Ames, and make sure the candle's out."

"Oh, I doubted it. I remember. Lay down again."

But Mrs. Ames had surged out of bed and was slipping into her shoes. Having achieved his object, her husband drew the blanket over his head. Salving his conscience by repeating, "I doubted it," he went to sleep again.

With her tweed coat buttoned over her nightdress, and her hat, adorned with an eye veil, perched on top of her curlers, Mrs. Ames went out into the night. She was not nervous of the darkness, while the Gallery was only the length of a short street away.

Directly she turned the key in the great lock and pushed open the massive mahogany doors, she felt that she was really at home. She had brought her pocket-torch, for she knew that if she switched on the light, a policeman might notice the illumination and feel it his duty to investigate. And, as she was one of those free and fearless souls who strew the grass of public parks with chocolate paper and cigarette stumps, she had an instinctive distrust of the law.

She entered the Gallery, and then stood on the threshold—aware of a change. This was not the familiar place she knew so well.

It seemed to be full of people. Seen in the light from the street lamp, which streamed in through the high window, their faces were those of men and women of character and intelligence. They stood in groups as though in conversation, or sat apart in solitary reverie.

But they neither spoke nor moved.

When she had seen them last, a few hours ago, under the dim electric globes, they had been a collection of ordinary waxworks, representing conventional historical personages and Victorian celebrities. Only a few were in really good condition, while some were ancient, with blurred features and threadbare clothes.

But now, they were all restored to health and electric with life. Napoleon frowned as he planned a new campaign. Charles II. mistook her for an orange-girl and ogled her. Henry VIII. shook with silent laughter.

Mrs. Ames felt absurdly abashed by the transformation. She knew she had only to snap on the light to shatter the illusion. Restrained by the memory of the policeman, she did her best to put the figures back in their proper places.

"Hallo, dearies," she called. "Mother's popped in to see you."

Her voice echoed queerly under the domed mahogany roof. She had a vague impression that the Waxworks resented her liberty, as she hurried towards the Hall of Horrors.

A crack of light which outlined its doors told her that her husband had been too optimistic about his memory. This smaller Gallery had not been wired, for it held no lurid attractions. She rushed inside, to see a guttering candle stuck upon the floor.

Although no damage had been done, her indignation swept away imagination. But after she had blown out the flame, she became dimly afraid of her surroundings.

There was no special reason for her to feel nervous. The Hall of Horrors housed only a small number of selected murderers, whom, normally, she despised. These figures were not spectacular, like her cherished Royalties. They wore dull coats and trousers, and could easily be mistaken for nonentities such as Gladstone and Tennyson.

But, as she threw her torch over them, a pinprick of light gleamed in each glassy eye, imparting a fiction of life. They seemed to be looking at her with intent and furtive speculation, as though she were the object of a private and peculiarly personal inventory.

Suddenly she remembered that she was among a company of—poisoners.

Although she was furious with herself for her weakness, her nerve crashed. It was in vain that she reminded herself that these were, in reality, her very own Waxworks. She treated them as her children. It was true that they were a neglected family, for she was an amiable sloven; but, occasionally, she brushed their clothes and hair, or cleaned their faces with a lick of spit.

Now, however, as she hurried down the Gallery, she felt that they had grown alien and aloof. They seemed to regard her with unfriendly eyes, as though she had interrupted some secret and exciting mystery.

They resented her presence. At this hour, the gallery belonged to Them.

Mrs. Ames lost no time in taking their hint. She shuffled through the door, locked it behind her, and ran down the street in flapping shoes. Less than five minutes later, she woke up her husband, to relate her experience.

"I was never so scared in my life. They weren't like the Waxworks I knew. All the time I was there, they were watching me, just as if it was their place, and I'd no right there...Go on, laugh. You've been safe and warm in bed, after trying to burn the gallery down...But you listen to me, Ames. I tell you, those figures were up to some business of their own. And I felt in my bones that it was no good business either."

BEFORE ever she saw her, Sonia Thompson looked upon Mrs. Cuttle as a predestined victim.

She was stupid, complacent, blind. She possessed what other women coveted, but had not the wit to appraise its value, or the imagination to guard it. And she was at the mercy of unscrupulous persons.

Of course, the first suggestion was the result of idle gossip. The impression it made upon Sonia was probably due to the fact that she was both physically tired and mentally excited, and therefore, strung up to a condition of sensitised perception.

When, afterwards, she looked back on her first night at Riverpool, it always appeared intangible as the dust of a dream, so that she could not be sure of her memory. Every place seemed to be dark, and buildings rocked. There was confusion of senses, and optical illusion, in which men were transformed into waxworks and waxworks into men.

She had travelled direct from Geneva, and she still swayed with the motion of the train when she signed the register of the Golden Lion Hotel.

"Sonia Thompson." She lingered for a moment to look at it.

"Wonder if that name will ever be famous," she thought.

The coffee-room had a sunken floor, dark flock wallpaper, and was dimly lit. Apparently the windows were hermetically sealed, and the odours of heavy Victorian dinners—eaten long ago—were marooned on the warm still air. Directly she had gulped down a quick meal of bacon and eggs, Sonia went out to explore the town.

It was between nine and ten, when Riverpool looked especially dreary, with shuttered shops and deserted streets. A fine spit of rain was falling which slimed the cobbles of the road. She wandered rather than walked, while the Channel steamer pitched again under her feet, so that—occasionally—she reeled in a nightmare of wet heaving pavements and flickering lights.

It was in a sober and stationary moment that she found herself standing outside the Waxwork Gallery.

The place had a sinister reputation. Built in 1833, it had been unlucky almost from its beginning. The speculative builder who erected it had hanged himself in the Hall of Horrors. During the Hungry Forties a tramp had been found inside—dead from starvation. In the Naughty Nineties a painted woman of the town had been murdered in the alcove, wherein was staged—appropriately—the final tableau in the career of Vice.

Only recently, there had been a fresh link in the chain of tragedies. A stranger—a commercial traveller—had sought a free lodging in the Gallery, and had paid his bill, according to precedent. The porter discovered him in the morning, lying in Virtue's bed; and the worthy patriarch had a corpse for a bedfellow.

The post-mortem disclosed cirrhosis of the liver. A letter, vowing ferocious vengeance, and signed, "Your loving husband," indicated an unfaithful wife. The combined effect of rage and drink had been a fit.

Although Sonia knew nothing of its history, she felt the pull of some macabre attraction which drew her inside the Gallery. Directly she passed through its massive doors, she was further excited by its peculiar and distinctive atmosphere—sour-sweet, like the stale perfume of a soiled lace handkerchief.

The building was large and dim, panelled with mahogany and draped with tawdry black velvet, filmed with dust. One side had been built into alcoves which housed tableaux depicting scenes in the careers of Virtue and Vice. In spite of being faintly lit with a few pendant electric globes, it smelt of gas.

At first blink, Sonia thought the gallery was full of curious people. Then she realised that she was being tricked in, the usual way. She spoke to the commissionaire at the door, before she discovered that she was asking her question of a dummy.

Apart from the Waxworks, the place seemed to be empty. No other visitors inspected the collection, which was large and second-rate. She picked out Henry VIII., in a buff suit padded and slashed with scarlet; Elizabeth, in grimed ruff and blister-pearls; Mary of England, pasty as dough, but resplendent in new plum satin.

As she paused before Charles II., who had preserved his swagger and leer, although his white velvet suit had yellowed to the tint of parchment, a second trick was played upon her. Two figures seated in a shady corner suddenly came to life, and moved, swiftly and silently, towards the exit.

Sonia could see only the back of the man, who was tall and broad-shouldered. His lady, too, had the collar of her coat drawn up to the level of her eyes; but under her tilted cap was a gleam of conspicuous honey-gold hair.

They threaded their way expertly through the groups of Waxworks, and had slipped through the door almost before Sonia could realise that they were not a delusion.

She was staring in their direction when Mrs. Ames came out of the Hall of Horrors. As usual, she was doing duty for her husband, who was in bed with seasonal screws.

Sonia turned at the sound of flapping footsteps, and saw a tall stooping woman, with big regular features, large mournful eyes, and a mild sagging face. She wore a dirty smock of watercress-green, and a greasy black velvet ribbon in her grey hair, which was cut in a long Garbo bob.

In her relief at meeting someone who was definitely human, Sonia spoke to her with enthusiasm.

"What a marvellous place. It has atmosphere."

"It has not." Mrs. Ames' voice was indignant. "Besides I like it. It's healthy."

"No, no. I meant—tradition, background. One feels there are stories here...Who was that couple who went out just now?"

"Couple?" repeated Mrs. Ames. "I saw no couple."

"But you must have seen them," insisted Sonia. "They had to pass you. A tall man with a white muffler, and a lady with fair hair."

Mrs. Ames' face remained blank.

"You must have been mistaken, or else seen ghosts," she said. "Plenty of ghosts here—or ought to be. Would you like a catalogue, miss?"

"Why?" Sonia spoke absently, for she was still baffled by the mystery. "All the figures are labelled."

"Only for the public. The intelligent visitors always like to have them explained."

Sonia was not exactly impressed by this test of intelligence. She looked at Mrs. Ames, and decided that if her face were lifted and made of wood, it would be a handsome figure-head for a ship. She saw it, wet and magnified, rising and falling triumphantly through a smother of green sea—and again, the Channel steamer pitched under her feet.

Suddenly, it occurred to her that a journalist should not neglect any chance of learning some local history.

"Perhaps you could show me round instead?" she asked.

As a coin was slipped into her palm, Mrs. Ames revived like a wilting flower after aspirin has been added to its water. She swept, like an argosy in full sail, towards Henry VIII., and introduced him with a grand flourish.

"This is the finest figure in our collection. Henry Rex Eight. Magnificent torso. I've sat for the figure myself, so I should know."

"And where is his collection of wives?" asked Sonia.

"Only six, miss," remarked Mrs. Ames stiffly. "And he was married to all of them. Not many gentlemen, to-day, as can say as much...This is Charles the Second."

"And I suppose he was another pure and virtuous king?"

"Well, miss "—Mrs. Ames hesitated—"if he wasn't a king, perhaps we might call him a naughty boy. But, whatever he did, he paid for it. He was executed at Whitehall...This is Elizabeth. A very clever queen. She never married, but had lovers, so they called her 'Good Queen Bess.'...Bloody Mary. When she was dead, they cut open her heart, and found 'Calais' written on it."

Sonia began to feel that her shilling was not wasted on Mrs. Ames. The woman was a character and probably had a Past. Her voice was educated, although the foundations of her history had slipped.

"Is this the oldest figure in the collection?" she asked, as she paused before a pathetic waxwork, with a blurred pallid face, and a robe of moth-eaten black velveteen.

"One of them," replied Mrs. Ames sadly. "Mary of Scotland. But she's worn the worst. She—she's got to go. But we keep putting it off."

She gulped as though she were discussing the fate of some pet animal, while Sonia sighed in sympathy.

"Poor doomed Mary," she murmured. "She reminds me of my favourite doll. I wouldn't go to sleep without her. They burned her because they said she was germy, and gave me a new one which I slaughtered on the spot. But Mother always knows best...I do feel for you about poor Mary. I expect she's real to you."

As a wave of sympathy spread between them, Mrs. Ames relaxed into gossip.

"As real as the townspeople. In fact, some of the Waxworks remind me of them, and I get quite mixed. Henry the Eighth is the spit of Alderman Cuttle. He's got the big shop, like Selfridge, and he's going to be our next mayor. He's a terror for the ladies. I could fall for him myself. And Elizabeth's got the same red hair and sharp face as Miss Yates. She's Alderman Cuttle's secretary, but she means to be the second Mrs. Cuttle."

"Is the Alderman's wife dead?" asked Sonia.

"Not yet."

"What's Mrs. Cuttle like?"

"Like a sack of potatoes, except she hasn't got their eyes. She'll need them. She was only a nurse, but she pulled the Alderman through a bad illness, and he married her. And now she stops the way. I wouldn't be in her shoes for all her fine house."

Mrs. Ames sniffed ominously and passed on to the next figure.

"This is Cardinal Wolsey. I expect you recognise him, for he's the advertisement for woollen pants. He said, 'If I had served—'"

"Yes, thanks," interrupted Sonia, "but I've seen enough. I've had a long journey. I'll just rest for a minute and then I'll go."

As she dropped down on a wooden chair, she realised that she was desperately tired and not quite normal. The lack of ventilation had drained her of her energy; but, while her legs felt leaden, her brain ticked away feverishly.

Her nerves quivered to the spur of sharpened senses; she became aware of hidden life—a stealthy movement behind a curtained alcove—the stir of a whisper.

"Do you get many visitors?" she asked.

"Now and again," was the vague reply. "The fact is, miss, the Gallery's got a—a bad name. They say you can't stay here all night and live to tell the tale."

"That's intriguing." Sonia felt a flicker of reviving interest. "Some one ought to test that theory."

"Someone did. Last month. And they found him, next morning, dead as frozen mutton. He threw a fit and passed out."

"Oh, tough luck. Coincidence, I suppose. Curious. It might be an idea for a newspaper. Perhaps I'll try it out and write it up, myself."

As she spoke, Sonia had the feeling that the Waxworks were listening to her. The Gallery had suddenly grown still and silent as a stagnant pond.

"Are you a writer?" asked Mrs. Ames.

"Yes, I'm on the staff of the Riverpool Chronicle. At least, I will be. To-morrow. I really must push off now."

She sprang to her feet, and then staggered in momentary vertigo. The walls of the gallery rocked and there were rushes of darkness. Afterwards, she believed that she was gripped by a premonition of the future, for she was filled with horror of the Gallery.

She saw the Waxworks, not as harmless dummies, but as malign agents in a corrupt traffic, while Mrs. Ames' face—wooden and gigantic—tossed in the swell of a grey sea. It dwindled to life size, and she realised that she had grasped the woman by her arm.

"A bit dizzy?" asked Mrs. Ames.

"Only a black out," replied Sonia. "I'm quite fit now, thanks. Good-night. I'll come and see you again."

Directly Sonia had gone, Mrs. Ames glanced at the clock, and then closed the Gallery. It was a simple business; she merely rang a hand-bell, and the public—represented by a few couples—immediately took the hint.

It was a curiously furtive and speedy exodus. They slipped out of corners and alcoves, and reached the door by circuitous routes. Each respected the anonymity of the other. No greeting was exchanged, although they might probably speak in the street.

For the Gallery had sunk to be a place of assignation—of stolen meetings and illicit love. People no longer came to view the carefully renewed bloodstains in the alcove—which, officially, could not be washed out—or to shudder at the builder's rope, which was the star relic in the Hall of Horrors. They came only to whisper and kiss.

It is true that it witnessed the course of true romance when sweethearts sought sanctuary from the streets. It is also true that every one looked respectable and behaved discreetly. A middle-aged pair might be obviously prosperous tradespeople; but, if the man were Mr. Bones the butcher, the inference was that the lady was Mrs. Buns the baker.

Mrs. Ames watched the last couple steal through the door, with a sentimental smile which said plainly, "Aren't we all?" Then she rang her bell again, shouted "Every one out?" and switched off the light.

On the threshold, she turned back to speak to her beloved Waxworks.

"Good-night, dearies. Be good. And if you can't be good, be careful."

SONIA had barely returned to her hotel when she saw a ghost.

The Golden Lion was an old coaching inn, and, although large and rambling, had been modernised only to a limited extent. Instead of a lounge, there was an entrance hall, with uneven oaken floor, which led directly to the private bar.

Sonia sank down on the first deep leather chair, and was opening her cigarette case, when she recognised, a few yards away, the spectre of the Waxworks.

He had not materialised too well. In the dim gallery, he had been a tall romantic figure. Here, he was revealed as a typical Club man, with a hard, clean-shaven face and black varnished hair. It is true that his profile had the classical outline of a head on an old coin; but it was a depreciated currency.

"Who is that?" she whispered, as the waiter came forward with a lighted match.

"Sir Julian Gough," was the low reply.

"Of course. Isn't his wife tall, with very fair hair?"

"No, miss." The waiter's voice sank lower. "That would be Mrs. Nile. The doctor's wife. That's the doctor—the tall gentleman with the white scarf."

Sonia forgot her exhaustion as she studied the communal life of the bar. Dr. Nile was a big middle-aged man, with rather a worried face and a charming voice. Sonia decided that, probably, he was not clever, but scored over rival brains by his bedside manner.

"I wonder if he knows what I've seen to-night," she thought.

On the surface, the men did not appear to be hostile. They exchanged casual remarks, and seemed chiefly interested in the contents of their glasses. Sonia decided that it was a dull drinking scene, as she listened sleepily to the burr of voices and the clink of glasses. The air was hazed with skeins of floating smoke and it was very warm.

She was beginning to nod over her cigarette, when she was aroused by a shout of laughter. A big burly man, accompanied by two ladies, had just rolled into the bar. Although he was not in the least like Henry the Eighth, she recognised Alderman Cuttle by Mrs. Ames' description. He was florid and ginger, with a deep organ voice and a boisterous laugh.

"Well, ma. How's my old sweetheart tonight?" he roared, as he kissed the stout elderly proprietress on the cheek.

"Not leaving home for you," she replied, pushing him away with a laugh. "Brought the beauty chorus along?"

"Just these two girls, ma. Miss Yates has been working late and can do with a gin and it. And Nurse Davis works all the time. Eh, nurse?"

As he spoke he winked at the nurse. She was a mature girl of about forty-five, plump, with a heart-shaped face and a small mouth, curved like a bow. She wore very becoming uniform.

As for the other "girl," Miss Yates, Sonia could not imagine her meagre painted cheeks with a youthful bloom. She looked hard, ruthless and artificial. Her sharp light eyes were accentuated by green shading powder, and her nails were enamelled ox-blood. Her best points were her light red hair and her wand-like figure.

She wore what is vaguely described as a "Continental Mode" of black and white, which would not have been out of place in Bond Street.

As she watched her thin-lipped scarlet mouth, and listened to her peacock scream laugh, Sonia remembered the stupid shapeless wife at home.

"Poor Mrs. Cuttle," she thought. "That woman's cruel and greedy as Mother Ganges."

With the alderman's entrance, fresh life flowed into the stagnant bar. There was no doubt that the man possessed that indefinite quality known as personality. His remarks were ordinary, but his geniality was unforced. He seemed to revel in noise, much in the spirit of a boy with a firework.

His popularity, too, was amazing. The women clustered round him like bees on a sunflower; but the men, also, plainly regarded him as a good sport. It was obvious that he had both sympathy and tact. Although he regarded the limelight as his special property he could efface himself. Sonia noticed that he, alone, listened to Dr. Nile's longwinded story about an anonymous patient without a trace of boredom.

He fascinated her, so that she could not remove her gaze from him; but, while the amorous alderman flirted as much with the plain elderly barmaid as with the others, he showed no interest in herself.

Sir Julian had already remarked that she was an attractive girl, for he repeatedly tried to catch her eye with the object of putting her into general circulation. But the alderman cast her one penetrating glance from small almond-shaped hazel eyes. It was impersonal, but appraising—and it might have reminded Mrs. Ames of the scrutiny of the poisoners in the Hall of Horrors.

"Thinks me too young," thought Sonia. "How revolting."

As she pressed out her cigarette, the landlady looked across at her young guest.

"Did you have a nice walk?" she asked professionally.

"Yes, thanks," replied Sonia. "I discovered your Waxwork Gallery."

As she spoke, she had an instinctive sense of withdrawals and recoils, as though she had thrown a stone into a slimy pool, and disturbed hidden forms of pond life.

"That's rather a low part of the town," said the landlady. "I'm ashamed to say I've never been in the Gallery myself."

"Neither have I," declared Sir Julian.

"Oh, you should drop in, Gough," remarked the alderman. "I do, myself, from time to time. Just to keep old Mother Ames on her toes. Civic property, you know...Ever been there, Nile?"

"Once, only," replied the doctor. "Ames called me in to see that poor chap the other day. He wanted to know if he was dead."

Sir Julian burst into a shout of laughter.

"That's a good one," he said. "They wanted to make sure he was dead, so they called in the doctor. No hope for him after that."

Sonia saw the sudden gleam in the doctor's sleepy brown eyes. She noticed, too, that Cuttle did not join in the amusement, which was short-lived.

"What did the poor fellow really die of, doctor?" he asked.

"A fit. He was in a shocking state. Liver shot to bits, and so on."

"I know that. But what caused the fit?"

"Ah, you have me there, Cuttle. Personally, I'd say it was the Waxworks."

"How?"

"Probably they frightened him to death."

"Rot," scoffed Sir Julian.

"No, sober fact," declared the doctor. "You've no idea how uncanny these big deserted buildings can be at night. There are all sorts of queer noises...When I was a student, I once spent a night in a haunted house."

"See anything?" asked the alderman.

"No, for a reason which will appeal to your sense of humour, Gough. I cleared out just before the show was due to start. I wasn't a fool, and I realised by then that—after a time—one could imagine anything."

"Now, that's interesting, doctor." The alderman put down his glass and caught Miss Yates' eye. "Time to go Miss Yates."

The red-haired woman got down from her stool and adjusted her hat.

"Now, don't you two hold any business conferences on the way home," advised the barmaid archly.

"No," chimed in the landlady. "You must behave, now you're our future mayor. You'll have to break your engagement with the lady."

"Lady?" repeated the alderman, in a voice rough with sincerity. "I'm not going to meet a lady. I'm going home to have supper with my wife."

The women only screamed with sceptical laughter. As she went out of the hall, Sonia heard their parting advice.

"Good-night. Be good."

"And if you can't be good, be careful."

It struck her that the stale vulgarism might have been the spirit of the place...

Secrecy.

Directly Alderman Cuttle was outside the hotel, he slipped his great hand through his companion's arm. Linked together, they strolled slowly down the deserted High Street, talking in whispers.

At the black mouth of the Arcade they parted. Miss Yates' arms clasped the alderman possessively around his neck as he lowered his head.

"Good-night, my darling," she said.

"Good-night, my girl. You won't forget what I told you?"

"Do I ever? Can't you trust me by now?"

"I do, my sweet. I do."

Their lips met in a kiss. The tramp of official footsteps sounded in the distance, but the alderman did not break away. When Miss Yates had dived into the Arcade, he strolled on until he met the approaching policeman.

"Good-night, officer," he said.

"Good-night, sir."

The man saluted respectfully, but the alderman dug him in the ribs.

"At my old tricks again, eh, Tom?" he chuckled. "Do you remember you and me with that little red-haired piece at the lollypop shop?"

"You bet," grinned the policeman. "You always were partial to red hair, Willie. I remember, too, as you always cut me out."

"That's my Mae West curves." The alderman slapped his broad chest. "We've hit the high spots, eh, Tom? But we're both married now. And there's no one like a good wife. Always remember that, Tom."

The policeman looked puzzled. He and the alderman had attended the local Grammar School, and, in spite of the difference in their social positions, had remained friends. But, even in the old days, he had never been able to fathom the depth of young Cuttle's sincerity; and now, after many years, he remained the same enigma.

"I want you to know this, Tom," went on the alderman. "The people here call me a gay boy. Maybe. Maybe. But, next year, when I'm mayor, remember what I'm telling you now...I've always been faithful to my wife."

He added with a change of tone, "Good-night, officer. Cigar?"

"Thank you, sir. Good-night, sir."

The policeman stared after the retreating figure. The alderman's deep organ voice had throbbed with feeling, even while a dare-devil had winked from one hazel eye. He told himself that William Cuttle still had him guessing.

Almost within the next minute he was a spectator of a distant comedy. The alderman had met one of his numerous flames, and was chasing her round a lamppost.

The girl was Caroline Brown—Dr. Nile's dispenser and secretary. Of mixed parentage—Scotch and Spanish—she had the tremulous beauty of a convolvulus. But, while the surface was mother, the under-tow was pure father.

She drifted round the lamppost before the alderman's clumsy rushes, like a flower wafted by the west wind; and, when at last he caught her, all he got was a stinging slap in the face.

With peals of laughter she broke loose, while he strolled on, chuckling, and humming snatches of "Sing to me, gipsy."

His house was situated in the best residential quarter of the town. It was a large, solid, grey stone building, surrounded by two acres of well-kept garden. Everything was scrupulously tidy. The drive was cemented, and the lawn—decorated with clumps of non-seasonal enamel crocuses—was edged with a low railing, painted metallic-silver.

The taste was his wife's. Like a good husband, he gave Mrs. Cuttle a free hand both with exterior and interior decorations.

Whatever the result from an artistic standard on a raw autumn night, his home appeared comfortable and prosperous. Mrs. Cuttle had the reputation of being a careful housekeeper, but economy was not allowed to spoil his welcome. An electric lamp outside the front door lighted his way up the stone steps, guarded with lions; and, when he was inside, the centrally-heated hall was thickly carpeted and curtained from draughts.

Cuttle rubbed his hands with satisfaction as he looked around at well-polished furniture and a pot of pink azaleas on a porcelain stand at the foot of the staircase.

"Louie," he called. "I'm home."

At his shout, Mrs. Cuttle came out of the dining-room. She was stout, with a heavy face, dull hair, and a clouded complexion. She wore an unbecoming but expensive gown of bright blue chenille-velvet.

It was she who presented the cheek—and her husband who kissed. But he did so with a hearty smack of relish.

"It's good to come back to you, my duck," he told her. "What have you got for me to-night?"

"More than you deserve so late. Curried mutton."

The alderman sniffed with appreciation, as arm-in-arm they entered the dining-room. It was typical of the prosperous convention of a former generation, with a thick red-and-blue Turkey carpet, mahogany furniture, and an impressive display of plate upon the massive sideboard.

The table was laid as for a banquet, with gleaming silver, elaborately folded napkins, and many different kinds of glasses. Vases were stuffed with choice hot-house flowers which no one looked at or admired. The central stand, piled with fruit, was evidently an ornament, for it was studiously ignored by the alderman and his wife.

The supper was being kept hot on a chafing-dish and they waited on themselves. Both made a hearty meal, eating chiefly in silence. Cuttle was the type of man who did not talk to women when they represented family, and his wife was constitutionally mute. Sometimes she asked questions, but did not seem interested in his replies.

"Why are you late, Will?"

"Business?"

"How is it?"

"So-so."

"Did Miss Yates stay late, too?"

"Did you ever see a dream walking? Did you ever hear of staff working overtime? No."

"What d'you think of the mutton, Will? It's the new butcher."

"Very good. Nothing like good meat. Gough was telling me Nile wants to put him on fruit. Pah. Pips and water."

"Sir Julian could do with dieting. His colour is bad. Is he still meeting Mrs. Nile in the Waxworks?"

"I never heard that he did." The alderman yawned and rose. "Well, my love, I'm for bed."

Mrs. Cuttle looked at the marble clock.

"It's too soon after a heavy meal. Better let me mix you a dose."

"No, you don't, old dear." Cuttle roared with laughter. "You had your chance to poison me when you were nursing me. Now I'm married I'm wise to your tricks."

"A few more late suppers and you'll poison yourself," said Mrs. Cuttle sharply.

"Well, I don't mind a pinch of bi-carb, just to oblige a good wife. I never knew such a woman for drugs. How would like it if the worm turned and I poisoned you for a change?"

"You couldn't if you tried. You've got to understand how poisons work."

The alderman looked thoughtful. He was a good mixer, and he had the local reputation of being able to talk on any subject.

He gave his wife a playful slap.

"Be off to bed. I want to look up something."

His own study was unlike the rest of the house, being bare and austere, with walls of grey satin wood and chromium furniture. The touches of colour were supplied by a dull purple leather cushion and a bough of forced lilac in a silver stand.

Mrs. Cuttle dimly resented this room. She had nursed her husband in sickness and in health, chosen his meals, mended his pants. She believed she knew him inside out, but for this hint of unexplored territory.

The alderman walked directly to the bookcase and drew out an encyclopaedia. With his wife's taunt rankling in his mind, he opened the book at the section "P," and ran his finger down the pages until he reached "POISONS."

EARLY next morning, Sonia arrived at the offices of the Riverpool Chronicle. It was a ramshackle building in the old part of the town, and not far from the Waxwork Gallery. The district itself was rather unsavoury. Instead of attaining the dignity of age, it seemed incrusted with the accretions of Time, as though the centuries—tramping through it—had spattered it with the refuse of years.

But Leonard Eden—the owner and editor—liked the neighbourhood. His paper was not only a rich man's hobby, but a refuge from a talkative wife. He was happy in his shabby sunny room, overlooking the stagnant green river, for he was not allowed to talk at home, and he had views which he liked to express on paper.

He left the practical end to his staff; young Wells, the sub editor; Lobb, the reporter; and Horatio, the office boy and the office authority on spelling. If they were not enthusiastic over his news of an amateur addition, Leonard appeared blandly unconscious of the fact.

He was a numb, courteous gentleman, with a long pale face, a monocle, and a stock; and, although he was popularly credited with the brain of a sleepy-pear, his hobby cost him considerably less than a racehorse or a lady.

When he interviewed Sonia at his London hotel, she believed that her appointment was due to the fact that he recognised her flair for journalism. Bubbling with enthusiasm, she lost herself in a labyrinth of words to which he barely listened.

He belonged to a generation that delighted in a pretty ankle, and resented that fact that when skirts rose, imagination ceased to soar. So he admired Sonia's lashes, while he decided that it would be a kindly deed to let her rub off her rough edges for a few months at his office, at a nominal salary. Besides being his god-daughter, he was a relative; her father had recently remarried, and the family horizon was dark with storm.

As for her fine future, he was confident that some young man would soon remove her, painlessly and permanently, from the sphere of journalism.

He lost no time in taking her to the main office and losing her there. Lobb was out, but Wells' dog occupied the editorial chair, while Wells scraped his pipe as a preliminary to work.

Leonard murmured a languid introduction.

"Mum-mm Wells. Miss Thompson. Did I mention her to you, Wells? Mr. Wells will find you some odds and ends and explain anything. Don't overdo it to-day."

There was a moment of stunned silence after the door had closed, while Horatio, in the background, hurriedly smoothed his hair with moistened palms.

"Didn't you expect me?" asked Sonia.

"Well, we'd heard a rumour," replied Wells, "but we didn't actually believe in you."

"Isn't that like my cherished Leonard? By the way, what d'you call him? The 'Chief?'"

"No. 'Buns.'"

"Oh...Well, will you call me 'Thompson,' and treat me just like a man? I mean, I don't want to cramp your style, or have preferential treatment."

In spite of her overture, young Wells already felt the first hint of restriction as he looked at her. She was an attractive young creature, with slanting butterfly brows, generous red lips, and the greyhound build of her generation. She wore the standardised fashion of swagger-coat and small hat, tilted over one eye, but her vivid face saved her from the reproach of mass production.

Young Wells knew instinctively that she was free from herd instinct. She would lead—and he would follow. She would smash precedent, create chaos, upset routine.

Perhaps, he heard, too, faintly in the distance, the clang of closing doors, and fought against his fate; for man is, by nature, a free animal and dreads the thought of the inevitable cage.

But while he regarded her bleakly, he found favour in her eyes. He was rather short and thickset, and she liked his broad shoulders and three-cornered smile.

"It's the dream of my life to work on a paper," she said. "What are you, by the way?"

"I'm rather a composite person," Wells told her. "I'm the sub and the sporting editor, and Kathleen, and Uncle Dick."

"I'll be Kathleen."

"No you won't. You're too young for the Women's Page. You have no idea of the questions you'll have to answer. I've come to the conclusion women have no refinement."

"Don't be absurd...Are you all the staff?"

"No. Lobb's our star turn. He's out now. He covers the water front and I cover the pubs. And here's Horatio."

Soma's smile made Horatio—who was impressionable—her slave.

"Are you going to be a journalist, too?" she asked.

"No, miss. An editor. My mother says there's always plenty of room at the top."

"You go and tell that to the old man, and study his reaction," advised Wells. Then he glanced at the clock. "Ten to eleven, you young slacker."

The youth vanished, after another languishing glance at Sonia. She looked around the big untidy room, with the frosted-glass windows, the sun-blistered paint, the ink-stained table, the battered typewriters—and then she sighed.

"Not a bit like the Pictures?" asked Wells. "One more illusion gone west?"

"It's very peaceful. But I did think of it like—like you said. You know. Telephones ringing like mad and every one using language. Doesn't a big story ever break?"

"Oh, yes. Sometimes a woman sets her chimney on fire on her neighbour's washing day."

"Then—it's not, a real newspaper office?"

"Yes, it is—if you're a real journalist."

There was a rasp in young Wells' voice, which Sonia resented in spite of her plea for non-preferential treatment.

"Well, I've had no experience," she confessed.

"But you're here. That's your answer."

There was a brief silence. Then Wells' dog got down from his chair and pointedly laid his head on Soma's knee, after a preliminary sniff. Young Wells took the hint and relented.

"You shall be Kathleen," he said. "As a matter of fact, a lady has just told Buns that she reads my page to get a good laugh. He had me on the carpet. He's very sensitive over the paper, remember...And you can have the Children's Corner, Film Notes, Poultry World, Gardening—"

"But I don't know—"

"Just lift them from any reliable source. Three parts The Gardener, and one part Beverley Nichols is the mixture for our Gardening Column—"

He broke off at a tinkling sound outside the door.

"Miss Thompson," he said solemnly, "you are about to share in our great moment, when the whole building vibrates with dynamic life."

"Oh, do you mean going to press?" asked Sonia eagerly.

"No."

"But—it can't be putting the paper to bed?"

"Where did you learn your weird language? No. Here it is." He flung open the door. "Eleven o'clock cocoa."

He laughed at Sonia's disappointed face, as Horatio entered with a tray and three steaming cups.

"It's an inspired idea," he said. "Buns always has it, so we have it too, to keep us from going Red."

Sonia enjoyed the cocoa-party, even while she dimly resented it. She had pictured her plunge into journalism as a dive into molten emotions, and a frantic race against time, to the stamp of overdriven machines.

But, even while she sipped her cocoa, while the clock ticked lazily on, a new element was creeping into her life. Young Wells looked at her with fresh interest.

"I'm wondering why girls leave home," he said presently.

"Meaning me?" she asked. "Well, you shall have the story of my life, but I warn you it's pathetic...Nobody loves me at home. The only time I was popular with my father was before I was born. I believe he mistook me for a boy. And he's just gone and married a girl who was at school with me."

"Poor girl," said Wells with feeling. "I bet you gave her hell."

"You bet I did." Sonia added, "For one ghastly moment, I thought you were going to pity me. Such a lot of men have poor-kidded me since the marriage. And I loathe it."

"I knew that. Here's Lobb. Trust him to turn up in time for the cocoa. He's a meal hound."

Sonia looked curiously at the tall gaunt man who had just entered. He was a striking figure for Riverpool, for he wore a cape and slouched black felt hat. Yet, in spite of appearing shabby, unhappy, and ill, his ravaged face held some of the dark broken beauty of a fallen angel.

"This is our Miss Thompson," said Wells. "She's real."

Sonia saw the light leap up in Hubert Lobb's sunken eyes, like fire rising through charred ash. He stared at her almost thirstily, as though he were refreshed by her youth.

"We'd come to regard you as fabulous. Rather like a unicorn," he explained, as he dropped down on a chair and drank his cocoa quickly, draining his cup.

Sonia, who was watching him, wondered compassionately whether he had come out without a proper breakfast. After glancing at his dusty coat, she decided that he was at the mercy of a neglectful landlady.

He met her speculative gaze with a half-smile.

"A new venture, isn't it?" he asked. "I hope you'll let me help you in any difficulty. But—you won't be here long."

"No," Sonia spoke eagerly. "This is only a jumping-off place for Manchester or Birmingham. After that, London."

"Ah. If I'd one grain of your enthusiasm, plus my weight of failures, I should be—" He pointed upwards and added, "Not here. As things are, Horatio has the only chance of being in the first flight."

"All the same, I rather envy you. You've lived. I feel so—unbegun."

Young Wells, who had noticed Sonia's interest in his colleague, thought it time to intervene.

"How's your wife, Lobb?"

"Not too well, thanks."

"And the kid?"

"Perfectly fit."

"Coming home for the holidays?"

"I suppose so." Lobb rose, the light in his eyes extinguished. "I suppose I must do some work—. or what passes for work here. By the way, Mrs. Forbes, wife of the chemist in Flannel Street, had her bag snatched last night."

"That's new for Riverpool. We're looking up. Does she know who lifted it?"

"No, too dark. She says someone snatched it and was round the corner in a flash."

"Much chink?"

"The week's housekeeping money...Do you want to see me, sir?"

He spoke to Leonard Eden, who stood drooping in the doorway.

"No, Lobb. Sonia, my wife is expecting you to dinner. As early as you can get out. Better not start here to-day. Just get the feel of things. Wells will give you a copy of the Chronicle for you to study. If you want anything for the office, my wife has an account at Cuttle's. Have it charged. Good-bye, my dear...Wells, downstairs, please."

Leonard drifted from the room, and Wells prepared to follow him. He stopped, however, to speak to Sonia.

"What's wrong here? Do you really want to shop?"

"Of course. I simply must have an amusing waste-paper basket. And a vase. I can't work without flowers. And a cushion. Shall I get some for the rest of you?"

"Please do." Wells spoke with deadly sweetness. "My colour's blue. I can't work unless everything's blue. But it must match my eyes."

As the door slammed, Horatio, who had been typing furiously to impress Sonia, moistened his lips nervously.

"Oh, Miss Thompson, if you got him a cushion, he'd pitch it into the fire. Why, he's the best centre-forward the team's ever had. And he's captain."

"Then he should play back. I always did. Hockey, I mean. We'll discuss the point one day, Horatio. Good-bye, angel."

She patted Wells' airedale, whose name was "Goal," and then glanced into the inner office, where Lobb was rattling away on a defective machine.

"Apparently a story has broken at last," she murmured.

Since bag-snatching had become epidemic, she could not enter into the general excitement, although she realised that it was a local novelty.

But no one, with the exception of the victim, knew of the exceptional feature connected with this special theft.

RIVERPOOL had already astonished Sonia by the unexpected size of its Waxwork Gallery and also of its chief hotel. It had a third surprise for her in Alderman Cuttle's shop.

It revealed him as a man of ambition and taste. Although not a modern trade palace of marble and metal, it was unnecessarily spacious and expensively decorated in grey and silver. The carpets were thick purple pile and the assistants all wore violet.

It was run on a skeleton staff, and when Sonia entered there were only a few customers. But the apparent slackness of trade did not worry the alderman, who was laughing heartily as he chatted to Miss Yates.

The daylight showed up the hardness of the woman's face and the patches of rouge on her high cheek-bones. She wore a skin-tight black satin gown, and spectacles with an orange frame to match her hair.

She took no notice of Sonia, but stared exclusively at her clothes—her eyes passing directly from her scarf to her hat, and leaping the gap of her face. But the alderman, who looked vast in long baggy grey plus-fours, gave her an impressive welcome.

"I'm honoured to see you here, Miss Thompson. I hope you will test my claim that you can do as well here as in London or Paris. Although we never tout for custom, I think we can satisfy the most critical taste."

"I'm sure you can if Miss Yates' dress is a sample," said Sonia diplomatically.

"Ah, you've got the name already. The journalistic instinct, I suppose. You see, we know all about you. Penalty of fame."

His laugh rolled down the building, as Miss Yates beckoned to an assistant and walked away. He certainly made Sonia's shopping easy, for he had a selection of articles brought from different departments. While she worked through her list, he lingered, giving advice and chatting casually.

Although she did not intend to be drawn, she thawed gradually under the geniality of his manner. His questions ceased to appear curiosity and became genuine personal interest.

"How do you stimulate your imagination?" he asked. "Strong tea? Alcohol? Or do you smoke opium like de Quincey?"

"I don't imagine." Sonia could not resist feeling flattered at being mistaken for an experienced journalist. "I just write up facts."

"I see. I do the murder, and you tell the tale. Ha, ha. Have you decided where you are going to live?"

"Yes. Tulip House."

"Oh, no. That's not quite good enough for you. They've just converted a house, and Nurse Davis has a charming flatlet there. Why not take a little flat?"

"I don't want the bother. And they say Miss Mackintosh makes her people comfortable. Besides—this is the real reason—I like the name of the house."

"Yes, that's how ladies generally pick a horse." He lowered his voice, although the assistant had gone to another department, "I often lay money for my lady customers. Not too profitable for me. They expect their winnings, but they usually forget to pay when they lose."

Again his loud laugh rolled through the shop.

"Thanks, but I don't bet," Sonia told him.

"No vices?"

"One. I write."

He cast her a penetrating glance from his small hazel eyes.

"Do you think you will like Riverpool?" he asked.

"I've hardly seen it yet. But I'm enchanted with the Waxworks. I intend to do a series of feature articles about it."

"Oh, good. I take an interest in it myself. I believe I am the only member of the council to use our private key. As future mayor, I believe these municipal relics should be preserved. Sometimes when I've an oddment of silk or velvet, and we're slack in the workrooms, I re-dress a model. At this moment, Parnell is wearing one of my suits. He was getting too much an advertisement for the Nudists."

"I'll look out for it," said Sonia.

"Mrs. Ames will show it to you. She's a character, but she has got to be watched. She clings to her old figures until they're nearly verminous."

"I know. She's terribly upset, at present, about Mary of Scotland. I suppose—you couldn't—"

"Mary? Ah, yes. She's about done for. She'll have to be scrapped."

For a moment, Sonia thought she surprised a gleam of cruelty in his eyes, as though he was discussing the fate of a real person who had displeased him.

"Absurd," she thought. "Why should he dislike a waxwork?"

Although her shopping was finished, the alderman still lingered. When the bill was paid and the assistant went to the cash-desk for change, he spoke confidentially.

"Quite made up your mind about Tulip House?"

"Quite."

"Then, there's an end of it. But I'd like to give you a word of warning under the hat about the other lodgers."

"Miss Mackintosh has already told me about them." Sonia spoke stiffly. "I understand Miss Blair is your mannequin, and Miss Brown is Dr. Nile's dispenser. She said they were both nice quiet girls."

"So they are. Bless my soul, yes. No, it's Miss Munro—the teacher at St. Hildegarde's College. She's peculiar—to say the least of it. Very peculiar. If you're wise, you won't get friendly with her."

Before Sonia could speak, he changed the subject.

"I expect you'll find it dull at first, with no friends. My wife will ask you to tea if you care to come. We're plain people—but she'll be your mayoress next year...Well, Bessie?"

He broke off, as a pale pretty girl approached with the stereotyped mincing step of a mannequin.

"Lady Priday is outside," she told him.

"I'll come at once."

The alderman strode down the aisle like a cyclone. He made Sonia think of a tempestuous draught which creates a vacuum in its wake, for directly he had gone the shop seemed empty and flat.

When she left a few minutes later, he was chatting to a lady who was seated inside an impressive Lanchester. They appeared to be on excellent terms, for her laughter mingled with his.

Apparently he did not notice Sonia; but, after she had passed, she turned suddenly and saw his reflection in a side-window.

He was looking after her with an expression of acute dislike in his eyes.

It reminded her of the flash of hatred with which she believed he had discussed poor Mary's fate; but this time it was not her imagination.

Apart from a shock to her vanity, she was principally perplexed, for she was used to rather more than her fair share of attention.

"If I'm not his type and he's bored, he wouldn't glare like that," she thought. "No. I've done something. What? I've spent money at his shop—but he can't hate me for that."

Before she had walked far, she believed she had found the solution.

It was the Waxwork Gallery.

"Of course," she decided. "He meets his ladies there. He is afraid I might attract other people if I write it up."

She tasted an anticipatory glow of the power of the press.

She went early to Leonard Eden's house, which was not the old Georgian mansion—indicated by his monocle and stock—but a modern sun-trap with butterfly wings. During dinner Mrs. Eden kept up her record for monologue, and Sonia realised the motive for Leonard's hospitality when she saw him steal happily away to his library.

Her hostess had talked her into a state of coma, when at last she was sent back in the car, for it was raining torrents. She thought, as she drove through it, that she had never seen any place more desolate than the dark deserted town, with its streaming pavements and puddled roads.

It was like the vision of a nightmare of a hundred years ago, and she was glad when she reached the Golden Lion.

"A dirty night," said the porter, as he opened the glass doors.

"Yes," she replied, "I pity any one out in this weather."

She regretted that it was her last night in the hotel, for her bedroom seemed doubly warm and luxuriant in contrast with the rain which lashed against her panes. It was newly decorated, with white walls, striped with silver, and cupids stamped over the blue bed-hangings.

On the dressing-table was a note which had been sent by hand. As she read it, she rather repented her criticism of the alderman, for it proved that not only were his impulses hospitable, but that he was prompt in action.

It was from Mrs. Cuttle, inviting her to tea at Stonehenge Lodge. She studied the note with interest, for already she was subconsciously concerned with Mrs. Cuttle. It was written in a thick, immature writing, with the backward slant adopted by some schoolgirls when they first try to make their script appear adult. The paper was thick and the address heavily stamped.

"I'll go," decided Sonia. "How that poor woman must loathe having strange girls wished upon her."

Although she was tired, she lay awake for a long time tossing in bed; and when at last she slept, she had confused dreams. She thought Mrs. Ames was showing her round the Waxwork Gallery. She was in the nude, but Sonia accepted it as quite the right conduct for a former artist's model. The figures were people whom she had already met in the town. Alderman Cuttle, glossily tinted and wearing grey plus-fours, stared at her with blind glass eyes. Hubert Lobb was crowned with an enormous black hat, under the shade of which his features were yellow wax.

The most appealing Waxwork was a shapeless figure, with a slit bodice which exposed straw stuffing.

"Poor Mrs. Cuttle," wailed Mrs. Ames. "She's doomed."

Then the dream shifted, and Sonia found herself in a shop, which stretched out in endless vistas after the manner of a nightmare. She had urgent need of a long list of articles, but she could not get served because all the assistants were Waxworks. She recognised Henry the Eighth behind the ribbon counter, while Elizabeth wore spectacles with orange rims.

Suddenly she was awakened by the sound of shrill ringing.

Her heart leaping from shock, she jumped up in bed, and snapping on the light looked at her watch. It was ten minutes past three. At that hour in the morning, there was an urgency in the telephone bell which she feared was the prelude to bad news.

In a panic, she picked up the receiver and heard the sleepy mumble of the porter who had connected the call with the extension.

"Hallo," she called.

A voice seemed to limp over the wire. It was faint and breathless, as though the person had been running.

"Are—you—there?"

"Yes," she replied. "Who are you?"

"Are you Room Eight, Golden Lion?"

"Yes. Who are—"

"I want to speak to my cousin. Miss Smith. She's staying here, in this room."

"I'm sorry, but you've got the wrong number," Sonia told the voice.

"No, please wait. It's so desperately urgent. Don't ring off...Are you alone?"

"Yes."

"So am I. So terribly alone."

The distress in the Voice touched Sonia's pity.

"Where are you speaking from?" she asked.

"From a call-office."

Sonia looked at the outside darkness with a shudder. The rain was still streaming down the glass. When she realised that a woman was out in merciless weather at that time of the morning alone—she felt almost ashamed of her own security and comfort.

"Why don't you ask the porter if your cousin is staying here?" she asked. "You've probably been told the wrong room."

There was no reply but a strangled sob. Sonia began to wonder whether the cousin were a fiction born of necessity.

"Are you in trouble?" she ventured.

"Trouble?" The voice laughed bitterly. "I'm drowning in deep water."

"Well." Sonia hesitated and then took the plunge. "If you'll come here and ask for me, perhaps I may be able to—to help."

"No. I'm past help."

"But—I don't understand—"

"You couldn't understand. I'm desperately lonely. I wanted to hear another voice. To know someone was alive beside myself. Devils are following me...I'm afraid."

"What are you afraid of?"

Two words jolted over the wire so faintly that at the time Sonia could not distinguish them. Then silence followed. She spoke several times, but got no reply. Presently she gave up and rang off.

"Pray it was a practical joke," she muttered. She looked around her bridal blue and silver room, and the festive cupids for reassurance, before she switched off the light.

Just as she was dropping off to sleep, the last two despairing words stirred inside her ear like the murmur of the sea in a shell.

"I'm doomed."

WHEN Sonia walked in at the gate of Stonehenge Lodge two afternoons later, she felt, not only an old member of the staff of the Chronicle, but that London had withdrawn to an incredible distance. The ancient town, with its worn cobbles, its murmurous underground river and hollowed pavements, had hypnotised her almost to the belief that she had lived there all her life.

When she was shown into the drawing-room Mrs. Cuttle was entertaining two other guests; or, to be accurate, she was at home to them while they entertained her.

Sonia had been prepared to find her hostess the pathetic creature of her dream. She had come in a generous spirit—eager to champion her, if help were necessary or possible. It was, therefore, rather a disappointment to discover that the lady was stolid, prosperous, and very well satisfied with herself.

As she sat enthroned in a corpulent chair, she reminded Sonia of an over-stuffed satin pin-cushion. Her eyes were blue and expressionless, except when they rested on the tea-table which gleamed with the best silver. Then they reflected complacency.

Sonia recognised Nurse Davis—still in becoming uniform. The other girl, who was tall, slight, and had honey-gold hair, was introduced as Mrs. Nile.

She chatted like a fountain, while Nurse Davis rolled on like a river, leaving Sonia free to study the room. It was large and crowded with good furniture; the carpet was a hand-made Sparta—the hangings expensive. But there was too much of everything; from the Italian landscapes on the walls to the vases which held more flowers than they could display effectively.

"It's the room of a greedy person," thought Sonia. Then she softened her judgment to "Or someone who's been kept short."

In spite of its size the drawing-room was warm and airless. A huge fire burned in the brass dog-grate, and heavy blue velvet curtains shut out the still grey November daylight.

Presently Sonia felt too torpid even to attempt to talk. At the same time her mind remained acutely receptive and tuned in to capture every impression.

She seemed to be a spectator of some domestic drama. At first the action was sluggish, for the talk was of servants. Nurse Davis declared that there was a domestic famine, and told long stories of the local ladies' shifts and difficulties. She had barely stopped for breath when Mrs. Nile gave a lively exaggeration of the system of bribery and corruption by which she said she kept her servants.

Mrs. Cuttle listened with pursed lips and nods. Presently she explained her own domestic arrangements.

It was like listening to a vast cistern being emptied drop by drop. She spoke slowly—often pausing to capture an elusive word. Yet she remained unflurried, and resisted any attempt to hurry or help her account.

"My girls are quite good. Well, not too bad. But I have to let them sleep out. It suits me. They come at seven and prepare the supper before they go."

This was the gist of her long and detailed statement. But had she been outside Time, instead of being enclosed in a padded chair, she might have realised the future significance of her domestic arrangements.

When at last she ran dry, Nurse Davis rushed into the gap.

"Your house is always so beautifully kept," she gushed. "This room looks as if it had just been spring-cleaned."

Mrs. Nile caught Sonia's eye with an elfin grin.

"Mrs. Cuttle has no pets," she said.

"No." Mrs. Cuttle nodded complacently. "Mr. Cuttle would like one, but cats scratch the furniture and dogs bring in dirt. I have a husband, so I don't want an animal."

"And I have a husband, two dogs, and a cat with expectations," remarked Mrs. Nile. "You can't keep a good woman down."

Still listening with detachment, Sonia decided that she liked Lilith Nile. She might be provocative and indiscreet, but she was also good-natured, amusing and gay.

Presently Mrs. Cuttle explained the delayed tea. "I'm waiting for my husband."

"I suppose he'll be bringing some girls along?" suggested Nurse Davis archly.

"I wouldn't put it past him. They won't leave him alone."

She spoke with placid indifference; and, when a few minutes later the alderman burst in, accompanied by Miss Yates and his model, Bessie Blair, Sonia saw no change in her face.

The alderman went directly to his wife and kissed her.

"Here we are, my love. These girls have missed their tea, so I ran them up in the car. They've been out at Lady Priday's. Poor Bessie's been modelling all the afternoon."

"Sit down, Bessie," invited Mrs. Cuttle.

She spoke a second after both her visitors were seated.

Miss Yates, who managed to look willowy even in a short belted fur coat, was completely at home. She ran her sharp eyes over the room, as though, when she was its mistress, she would know how to deal with its deficiencies, or rather superfluities. Sonia could see that she was both quick and capable; she watched Mrs. Cuttle slowly pouring out tea, as though she ached to sweep her off her chair and finish the job.

The alderman introduced a new element into the stuffy room. Every one grew more vital, and ceased to talk of servants and clothes. He flirted indiscriminately with the ladies, with the exception of Miss Yates and Sonia. But, while he was distantly polite to her, Sonia felt that there was an understanding between Miss Yates and himself.

As she watched him ogling Nurse Davis, whose pink bow-shaped lips and dimpled cheeks were wreathed in smiles, it struck her that the alderman was a figure which might become legendary. When the Twentieth Century had rolled away, an old civic Register and contemporary gossip's diary might resurrect the Amorous Alderman as a brilliant, fantastic figure capering against the faded tapestry of the past.

Already his flirtations and popularity were proverbial. On this occasion he was specially tender to his mannequin, Bessie Blair. Pale, with brown hair and green eyes, she had the symmetrical figure and features of a model, together with a reverential attitude towards clothes.

"Cake, Bessie?" asked Miss Yates.

Sonia was sure that Mrs. Cuttle resented the invitation. She opened her lips dumbly, as though in a vain struggle for speech. At that moment her stupid blue eyes were pathetic, as they strained against her handicap of inarticulation.

"Oo, they do look tempting," said Bessie, "but I daren't. The icing might start my tooth aching again. The stopping has come out of a back tooth."

"Dear, dear," clicked Nurse Davis. At the call to her sympathy, she changed instantly from a voluptuous Reubens goddess to a kind and motherly soul. "I've something that will cure that."

Opening her bag, she drew out a small case containing glass tubes.

"I've just been giving a patient a hypodermic," she explained. "Here, Bessie. Crunch this morphine tablet and put it in your tooth, but be careful not to swallow the saliva."

"Why?" asked Bessie.

"Because it's poison."

"Oo!" Bessie took up the case and read the names on the tubes. "Digitaline, atropine, strychnine, hyoscine, morphine...I thought you couldn't get poisons?"

"You couldn't. But I'm a nurse and use them medically."

"But how thrilling. I got The Trial of Madeline Smith out of the free library. It must be thrilling to be in a famous trial. Every one looking at you, and describing you and your dress, and wanting to marry you."

"But what about the eight o'clock walk?" asked the alderman.

"Madeline Smith got off. And anyway, she'd be dead by now. Nurse, do tell me. How many of these little things would it take to kill any one?"

"Let me think." Nurse Davis was purposely vague. "Each pilule is one seventieth of a grain. Perhaps eight or ten. But even a doctor can't say definitely. All drugs and poisons act differently on different people. And there's always an outside chance of an abnormal case."

"Anyway, there's somebody's death in that wee bottle," persisted Bessie. "Isn't it thrilling? How long would they take to act?"

"About a quarter of an hour if injected. Four or five hours, perhaps, taken by the mouth."

"Would the person know she was taking poison?"

"Yes. You'd have to disguise the taste in some highly seasoned food."

It was plain that Bessie was fascinated by the poisons. But as she watched the girl's empty, amiable face, Sonia received the feeling that she was but the mouthpiece of a stronger will. She was a model; usually, a lay-figure on which to drape clothes—now, a machine wound up to ask questions.

"Which would taste least?" she persisted.

"Hum," pondered Nurse Davis. "I should say digitaline was the least bitter."

"And what would it do?"

"It's a narcotic, so it would make you very sleepy. The breathing becomes stertorous, and there are some unpleasant symptoms. The least exertion is fatal. Gradually the heart slows down and then it stops."

"How thrilling," gasped Bessie. "Suppose any one took a fatal dose, could you bring them round again?"

"Yes, if the dose is not too heavy, and it's taken in time with a stomach-pump and a wash-out. But once it's right in the system you're good as dead."

Involuntarily Sonia studied the circle of listeners. She noticed Miss Yates' strained face, her greedy hollow palms and curving crimson-tipped fingers. The laughter-lines sprayed round the alderman's eyes had deepened to spurs in his concentration. Pretty Mrs. Nile was thoughtful, and seemed to have grown a few years older. Bessie's cheeks were flushed with excitement.

Mrs. Cuttle alone was unmoved, as she dipped a corner of her napkin into hot water and wiped a spot of grease off the teapot.

Sonia shuddered. She told herself that, here in the room, were three women who would like to be sitting in Mrs. Cuttle's chair. She was the predestined victim—superfluous, stupid, helpless.

The alderman broke the spell with a laugh like an exploding bombshell.

"Well, Nurse, now you've told this young lady exactly how to poison some one, you'd better tell her what she'll get if she tries it on."

With a feeling of relief Sonia shook off her morbid fancy. She saw the scene as it was in reality—a prosperous middle-class drawing-room, filled with ordinary people of sound morals and conventional virtues. The alderman was a clumsy bumble-bee, blundering from flower to flower; but he always kissed his wife before he went out and when he came home.

And yet—in spite of the muffins and the best china—in that warm, flower-fragrant room, the Spirit of Murder had actually struggled to birth in the dark cell of one brain.

"WHERE do you live?" asked Lilith Nile as Sonia rose to go.

"Tulip House."

"Then I'll come with you. It's on my way."

Although it was early, the November twilight had already deepened into darkness. The lamp over the front door lit up the cemented drive; but, outside in the lonely residential road, the time might have been midnight. Occasionally the illumined window of a house gleamed through its barrier of bare trees, or a lamp cast a feeble circle of light on the damp pavement.

Mrs. Nile talked continuously as they rustled through layers of rusty leaves; she asked questions, but, mercifully, did not expect replies.

"Did you see the autumn crocuses? Pathetic, aren't they? How d'you like Tulip House? My husband's dispenser digs there. She is frightfully sweet-looking. He says she's a little wiz at the work, and better than a man...You can't think how grateful I am for a new face. But I hope you're not discreet. Discreet people are so boring. As you've noticed, I'm indiscreet, on principle—or rather, lack of principle."

"Why?" asked Sonia to fill in the pause.

"Because it's expected of me. I say idiotic things just to see their silly faces. Every one here is waiting for me to come a cropper. So why should I disappoint them?"

"I seem to have heard something like that before."

"You mean—I'm dramatising myself?" asked Mrs. Nile, with unexpected penetration. "Well, you're bound to hear about me, if you've not already...Dr. Nile chose his wife from a tainted source. You see, I've one mother—and several fathers."

"What fun," said Sonia lightly. "You can pick your own."

"It's nice of you to be so modern about it. But it's the only thing I'm old-fashioned about. I always feel a father is one of those little facts which should be cut and dried."

Sonia was touched by the slight quiver in the elder girl's voice.

"I've been up against it myself," she said. "And you may be interested to hear that my trouble was a father—and a very definite one. A bit like the Barrett of Wimpole Street. After he married we had nothing but rows. So I cleared out. That's my solution. Work."

"You're lucky. I've nothing to do. No family—no servant worries. I was pulling their legs just now. Servants always adore me."

"What about sport? Golf?"

"I was an hotel child, and I never learned to play games. Except one. And that's the one my mother plays."

"Then why don't you start something?" persisted Sonia. "A bridge club, or some dances?"

"You can't get up things here. At least, you can't keep them spinning. The first may be a success, but the next will be a flop, You've got to depend on some one influential, and she's bound to drop out, and the whole thing collapses."

"What are the people like?" asked Sonia curiously.

"Lousy."

"No, but seriously. I want to understand them, because I'm going to work here. Have you heard I'm the new 'Kathleen?'"

"I'll write and consult you about my affairs. Plenty of them. I'm following in father's footsteps—one of my fathers."

"I'll tell you how the people strike me," remarked Sonia. "They're keeping a secret."

"No." Again Mrs. Nile surprised Sonia with a flash of shrewdness. "One half is keeping a secret. The other half is trying to find it out."

"Which is Alderman Cuttle doing?"

"Neither. He's perfectly obvious. Out to flirt with anything in a skirt."

"Not with me. He doesn't like me."

"Aha, who's dramatising herself now? You've the usual features. That's enough for him...And here's the parting of the ways."

They halted under a central lamp-post, from which radiated five residential roads. While they chatted, the Town Hall clock began to strike.

"Quarter to six," remarked Lilith Nile. "Later than I thought...Look here, I may play the fool, but I'd never let my husband down. He's given me things that other people take for granted. They mean everything to me. But he's got to trust me. And now I must fly home to him."

Sonia glanced down the dark vistas of stone garden walls topped by shrubs.

"What lonely roads," she said. "Are you nervous of walking home alone?"

"I don't. Ask the town. And what's there to be nervous of? Nothing ever happens here."

Fate, with dramatic effect, chose that moment to give the lie to her words. The garden gate of a large house, half-way down one avenue, was pushed open and two maids ran out into the road. One was in a parlourmaid's livery, the other wore a cooking-overall.

They stopped, panting, by the lamp.

"Have you seen a man running this way?" asked the cook.

"No," replied Sonia. "Why?"

"One of my ladies has had her bag snatched on her way home. I suppose there's not a policeman about?"

They looked down all the deserted roads, and then the cook shook her head.

"He's got clean away. Yes, mum, my mistress has 'phoned the police station. Come back, Nellie."

"That's the second snatch-and-grab," said Lilith jubilantly. "I wonder if we're in for an epidemic. What fun. Come back with me and see my angel Peke."

"No. I've got to have dinner, and then I'm going to the Waxworks."

"No, not there," called Mrs. Nile, as she turned down Arcacia Avenue. "All the low characters of the town go there. Including myself."

It was characteristic of Sonia to think of other people instead of her own concerns. Although she was younger than Mrs. Nile, she felt her senior. Presently she came to the conclusion that it was a case of transposed development. When she was a wretched hotel child, Lilith Nile was probably a premature woman, used to every kind of sordid shift. Now that she was grown up, she was trying to play.

And when a married woman starts to become juvenile in a small town, she is naturally rather a monkey-puzzle to her neighbours.

"Pathetic in a way," thought Sonia. "But I like her."

Tulip House was an old residence, situated in the heart of the town, and formerly occupied by Dr. Mackintosh, of mid-Victorian period. Its long narrow windows and double flight of steps were set flush with the pavement. Inside were large rooms, a fine hall, and a winding staircase.

The shabby furniture and worn carpets testified to a succession of boarders, by means of whom Miss Mackintosh—the doctor's daughter—preserved her childhood's home. She was an excellent cook, and, in spite of its shortcomings, Tulip House was clean and comfortable.

When Sonia entered, Miss Mackintosh stood at the foot of the stairs talking to Miss Munro, the History teacher at St. Hildegarde's. Sonia had been interested in her because of the alderman's warning, but so far, she had been invisible. Like Sonia, she had her private sitting-room, and she never used the communal rooms.

The hall was dimly-lit with one gas jet, but Sonia could see that Miss Munro belonged to a different world from that of the other boarders. There was distinction in the lines of her tall thin figure, and a suggestion of elegance in her tight dark suit. Her large eyes looked as if they had been recently blacked, in the dead white oval of her face.

Sonia credited her with pride, reserve, and fastidious taste. She felt instinctively that Miss Munro was not concerned with surface values. She might ignore her coat, but she would be meticulous about its lining.

"You ladies should know each other, as you'll be meeting in the house," said Miss Mackintosh.

Sonia advanced with a smile which met with no response. Miss Munro merely bowed stiffly, and then turned pointedly away and began to mount the staircase.

Miss Mackintosh began to canvass for breakfast orders.

"Would you like haddock?"

"Is she always as rude?" asked Sonia indignantly.

"Or perhaps you'd prefer eggs?"

It was evident that Miss Mackintosh would not discuss her boarders. Sonia respected her reserve and went into the dining-room, where Caroline Brown—beautiful and fragile, as though spun of roses and the west wind—was adding up figures in a small account-book while she devoured an enormous tea.

Bessie Blair, who had just returned from Stonehenge Lodge, looked on enviously.

"How you dare. If I ate dripping-toast, I should put on stones."

"I can give you something to keep you slim for all time," offered Caroline. "A dear little worm in a gelatine capsule."

"Don't be disgusting." Bessie continued to look critically at Caroline's sylph-like figure. "It beats me why you slave, when you could be a mannequin."

"I'm not a sap," said Caroline. "A face lasts about five minutes, but the rest of you goes on for years, and it's got to be fed. I'm saving in the Halifax Building Society for my old age. I had an aunt in a beauty chorus, and all she did was to come home with a bundle in her arms. I had to bring it up just as I'd finished with my little brothers and sisters. But I always prefer illegitimate children. They're like mongrels, more intelligent and affectionate."

She scraped the jam spoon with skilful spatulate fingers which contrasted so oddly with her floral face, and got up from the table.

"The alderman's taking me to the pictures," she announced. "Aren't I lucky?"

"Not my idea of luck to go out with a fat married man," said Sonia.

"Ah, it's easy to see you've never paid for your pictures."

"But what is the special attraction about the alderman?"

"He pays."

Bessie looked thoughtful as she shook her head.

"No, Caroline, there is something about the boss. I think it must be his strength. I've seen him tear a trade journal in two."

Sonia was to remember that remark later, in different circumstances. At the time, in the shabby comfort of the room, with cheerful company, it made no impression.

She ate her dinner with a book propped in front of her, and directly it was finished she walked to the Waxwork Gallery. The instant she passed through the mahogany doors, and smelt its characteristic odour, she was gripped by the fingers of the past. The advertisements in old magazines in her grandmother's book-cupboard suddenly stirred in her memory.