RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

BILLIE'S thumbs were turned down. "Kill! Kill it!" she shrieked.

In front was the dilapidated wood-shed, criss-crossed with stacks of sweet-smelling timber. Above was the clear blue stain of a cloudless sky. The sun-baked ground was a scene of the wildest riot and disorder. Sawdust flew into the hot, quivering air as a swarm of rats, a couple of terriers, and two sunburnt men in flannel shirts doubled and cut, turning the yard into an arena of strife.

On the outer fringe of the conflict, poised on a log, were the two spectators of the rat-hunt. They formed a curious contrast. Belinda Salt, commonly known as Billie, the apple of her father's eye, the idol of the station, and the belle of the whole district, was quivering with excitement as she leaned, with her body poised at a dangerous angle, over the yard. An ecstatic puppy was tucked under one arm. Her clear skin was tanned, her eyes were fearless, and her hair a copper glory. The vitality that seethed from every line of her face and every gesture of her lithe form bubbled up constantly from a vast reserve of energy. As her male belongings said proudly, Billie was full of ginger.

Her companion stood gazing apparently at the hunt with listless unconcern. As a matter of fact his eyes were steadily focusing a low line of blue hills in the distance. He was tall and fair, and had regular features. His face and figure bore testimony to race. His manner was stamped with the hall-mark of Eton and Oxford. His clothes, with silent but eloquent voice, rose up and called a good tailor blessed. He smoked a cigarette, apparently unconscious of his companion's clamour.

Billie's eager eyes watched every detail with vivid interest. Her upbringing was responsible for her crude tastes; for the girl's mother, by dying early, had turned her baby over to her men-folk and the universal mother. Between them they had made a good job of the girl's rearing, according to the broad terms of the contract—sun, wind, freedom, and masculine devotion all contributing their share. But while the essentials were sound, the details of necessity were lacking.

Billie jumped up and down, urging on the men with increasing vigour. So

engrossed was she in the sport that she never noticed when the frantic pup

slipped from her arm and joined the fray. But a piteous howl roused her, and

she turned to see a huge grey rat hanging on to the white coat of her pet.

With a cry of dismay she cried out to her silent companion.

Billie jumped up and down, urging on the men with increasing vigour.

"Oh! look, look Mr. Tygarth—look! Be quick and get him. Quick!"

Tygarth never moved. Apparently he was absorbed in re-lighting his cigarette. Billie gave him one quick glance, but she did not repeat her appeal. Springing off the log, she dashed into the mêlée, to return a minute later with the puppy. Tygarth turned his head slowly.

"What's happened?" he asked. "I was just trying to get this thing to draw."

"I noticed you were absorbed," answered the girl. "This bad pup got loose, so I had to go to his rescue."

As she spoke she shook her hand impatiently, and Tygarth noticed that a small splash of red had speckled the sawdust.

"Good heavens! You've got a bite," he exclaimed. "Here, let me tie up your hand."

Billie looked him squarely in the eyes.

"No, thank you, Mr. Tygarth," she said, quietly. "I prefer not to trouble you. Forster will do it."

She called out, and immediately the hunt was suspended, both Dyke and Forster crowding round their queen in concern. As they bore her off between them to their universal remedy, the cold-water tap, Forster looked back to shout to Tygarth:—

"You should not have allowed this to happen. You want more eye-wash, young man."

But Tygarth remained motionless, sucking at his cold cigarette, his face absolutely devoid of expression as he watched the shadows drifting over the hills.

Tygarth came of a race of mighty warriors and hunters. From the first Tygarth, surnamed the Tiger, killing had been their occupation and pleasure. They killed men for work, and beasts for play. The Tiger now only survived on the coat of arms, and the savagery of the original strain had been watered down to a streak of the courage that had made the name of Tygarth famous.

The Tygarths had always been attracted by feminine courage, and had chosen wives of similar stern material. But one Lady Tygarth of an earlier day had been cast in a gentler mould, for, before her marriage, she was destined to be a Bride of the Church. Throughout her life she was an earthly angel, and when she died a feather dropped from her wing, and, floating down the ages, lighted on the forehead of the present Dennis Tygarth. From the very purity of its source it was the white feather, and Dennis Tygarth was utterly and hopelessly a coward.

His cowardice was as much a disease as insanity, or a craving for alcohol. It was deep-seated, its roots reaching down to the very rock-bed of Fear. Perhaps the worst feature in the case arose from the fact that not one of the Tygarths had the courage to acknowledge this failing in their heir, and to openly tackle it. They held their heads high, affecting not to notice the record of nursery, school, and college. Finally, they sent him abroad to the Salts' ranch, with the unspoken hope that the wilder life of the Australian bush might foster his stunted manhood.

Sandy-creek was a bad place for cowards. Dennis's nervous shrinkings from animals reached a climax of spasms of terror at the unknown insects and reptiles. But his fear culminated in the knowledge that one day Billie would find him out.

When he first arrived he was not popular. Billie complained that the Englishman's complexion was fairer than her own. Forster and Dyke, who were learning sheep-farming, shied at his silk shirts and fancy ties. Dr. Beaver, who was staying at the homestead whilst he pursued a course of investigations, was the first to diagnose Dennis's disease. And he held his peace.

Presently Billie began to annex the newcomer, and the jealousy of Forster and Dyke grew apace. After a month, however, perplexity began to mingle with her friendship. With hard-set mouth, Dennis waited for the disillusionment of the girl whom he had learned to adore. Bit by bit the truth leaked out. Hints were dropped, and ugly rumours spread about the station. As Dennis's fair skin peeled daily under the rays of the Southern sun, so the outer scales of his armour of self-protection were rubbed away under the test of each fresh incident. With the unlucky episode of the puppy the last shred was stripped away, and the girl saw the pock-marks of the scourge which the youth had tried to conceal.

Tygarth waited by the creek, watching the muddy water eddy by, till the short twilight smudged the sunlit land. When the windows of the dining-room shone like glow-worms he slowly crept back towards the house. He heard shouts of laughter, and the clinking of glass and cutlery, as he stood outside the door. Then, stiffening his lip, he turned the handle and slipped into his place at the supper-table.

No one took the least notice of him but Daddy Salt, who stopped in his task of carving to exclaim at Tygarth's pallid face.

"Bless my soul, the boy looks like a boiled rag," he said.

Billie turned her scornful eyes on Dennis. He noticed that her hand was bandaged.

"No, Daddy, not like a boiled rag," she corrected. "He looks like a striped thing that has run in the wash."

No one could have told from Tygarth's sphinx-like face that he had grasped her meaning, but every pulsation of his heart hammered home the truth. His tiger stripes were not a fast colour.

"Let the boy have his supper now, and don't worry him," interposed the kindly Salt. "By the way, Tygarth," he added, "a letter came for you by the mail to-day."

As Forster passed the envelope down the table he commented on the crest. "Why a tiger?" he queried.

Bitterly conscious of the irony, Tygarth explained clearly and at length. When he paused he looked up, and noticed a grin dodging from face to face before his suspicious eye. Then Billie spoke, innocently.

"It takes a long time for a tiger to become a domesticated cat," she observed. "I suppose now, that as the Tiger, your ancestor, is at one end of the chain and you are at the other, by the process of civilization you must have become—er—humanized. In future I shall no longer call you Tygarth. Instead, from this day forward, I formally christen you—the Tabby."

Dennis tried to smile at the outburst of cheers that followed, knowing well that his new name was the outward sign of his degradation.

After that night an era of persecution began for the Tabby. Dr. Beaver and Daddy Salt, absorbed in their different interests, took no notice, but Billie, Forster, Dyke, and all the hands on the run daily subjected the Tabby to a pitiless course of ragging. Every day they contrived a fresh test for his courage, and every day his quivering nerves gave way before the ordeal and he gave a more thorough exhibition of cowardice. But, as of old, the same curse followed him. No one openly accused him of his fault. Had Billie spurned him with her foot and trampled on him Tygarth would have hailed her overtures with relief. All his life he had longed to speak of his shame, feeling the mere mention would take away some of the sting. But Billie preferred to give him his medicine in the old nursery fashion. A snub was wrapped in a smile, an insult larded over with flattery, while at the bottom of the jam of Billie's sweetest speeches lay the bitter sneer. Treated thus, with outward politeness, Tygarth preserved a stony countenance, which further enraged the Inquisitorial Council of Three.

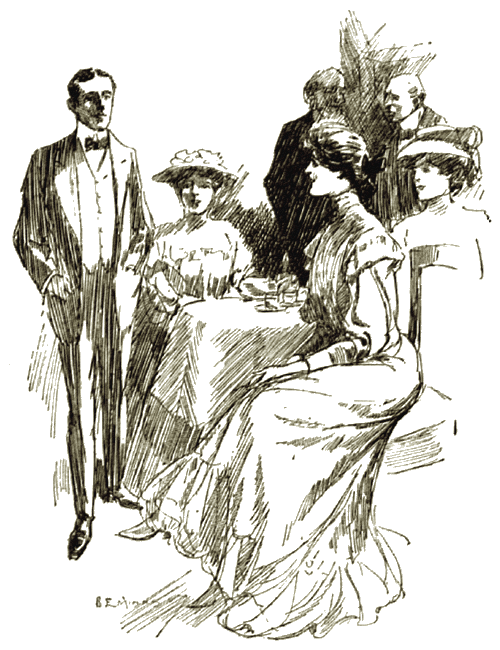

One afternoon, as Tygarth wandered listlessly on to the veranda, longing for the pitiless Australian blue and gold to change to his native green, and dreaming of trout-streams, a familiar sound floated out through the open French windows. The rattling of china and the buzz of conversation, stabbed with high-pitched feminine notes of exclamation, proclaimed a social function. As he entered the drawing-room he realized that he was assisting at the rites of a formal call.

These were visitors of a different type to the chance pilgrims who dropped in lightly at any hour on the Salt ménage, and who flapped away as suddenly on the casual wing of an angel unawares. The lavish hospitality of which these strangers partook was now pared down to a frigid entertainment which Dennis hailed as English afternoon tea. Billie presided over the teapot with her usual nonchalant air of dignity. But, true to feminine tradition, she had dressed for her own sex in a fashion she had never troubled to display to her male subjects, and as Dennis looked at her lace and flounces he felt himself subjugated anew by her queenly beauty.

A brief introduction enlightened him as to the identity of the visitors. The dry-skinned, wizened man, the large, gorgeous lady, and the two smart maidens stood revealed as Theophilus Berry, the richest squatter in the district, his wife, and his daughters.

With a sigh of relief Tygarth concerned himself with the transit of the tea-cups, feeling he had stepped from the savage region of the Southern Cross to his native sphere of the civilized world.

Billie noticed the change. Tygarth, answering to the call of his early training, was a different being to the cowardly youth who had cringed round the sheep-runs. Even the silk shirt and immaculate parting seemed now to take their right place in the general scheme of fitness, and appeared no longer a mixture, but a blend. For the first time the girl realized that two Tiger attributes—the steady eye and free bearing—had survived the watering-down process and chosen to reappear in this degenerate descendant.

Half cross with herself for her sudden interest, she glanced at her chosen pals, Forster and Dyke. They suffered badly from the contrast; as they squirmed their legs desperately to hide their uncompromising boots they appeared nervous and awkward. In short, for the first time Tygarth shone, solely from the fact that he now possessed what he had hitherto lacked—a fitting background.

The Hon. Theophilus Berry beamed at Tygarth and invited him to ride over

soon. Mrs. Berry seconded the invitation, and also beamed—in a manner

that was too maternal for Billie's taste, in view of the Berry girls' evident

overtures of friendship. It was true that Ruby Berry's face was freckled to

the semblance of a bran-mash, but Pearl was passably pretty, and had the

further advantage of being fresh from a finishing school in Brussels. So, to

her surprise, the despotic Billie found herself joining in the running, once

the Berrys had fairly made the pace, and helping to swell Tygarth's little

triumph.

The Hon. Theophilus Berry beamed at Tygarth and invited him to ride over soon.

But, after his long abstinence, the strong dose of flattery was as dangerous to Dennis as an over-lavish meal to a starving man. In a short time the unaccustomed kindness of Pearl Berry turned his head. Billie had treated him like a cur; now he would have none of her patting, and at the first opportunity he snapped back.

"It's a real treat to meet someone fresh from England," said Ruby Berry.

"It's a still greater treat to me to talk to a lady again," replied Tygarth.

The sudden sparkle in Billie's eyes asked the question framed by Miss Berry's lips.

"But you see Miss Salt daily?"

Tygarth shook his head. "Miss Salt is such an excellent sportsman, and has such wonderful courage and skill, that one overlooks the fact that she belongs to the weaker sex."

The youth uttered the words straight from a heart rankling with many an old wound scored thereon by Billie. He experienced the unholy joy of a small boy who has thrown a snowball at a policeman, all unconscious that a stone was embedded in his soft pellet.

Billie felt that her supreme power, her feminine charm, had been impeached. She glared at Dyke and Forster with burning eyes and read their anger in their crimson faces, while even Dr. Beaver's listless eyelids appeared to be suddenly wired. By mental telegraphy the sentence of lynch-law was passed by common consent, and all settled down to the task of showing up Tygarth.

"Talking of sport," said Forster, breaking the silence, "our friend, Mr. Tygarth, has given us many a surprising—I think I may call them surprising—exhibition of his skill. You know, Mrs. Berry, he is too modest to tell you himself, but he is descended from a particularly bloodthirsty and courageous ancestor. He was called the Tiger. Our friend preserves the traditions."

Pearl's eyes grew wide.

"How splendid!" she said. "We miss that sort of thing in Australia. Then, of course, you came here for sport and excitement."

A suppressed laugh flickered round the room, and Pearl was surprised to see a faint colour rise in Tygarth's nonchalant face.

"No, no; nothing of the sort," he answered, hastily. "I came merely for health."

"I thought you looked a little delicate. But our climate and Miss Salt's care will make a new man of you."

"That would be an impossibility."

Even the Berry family stared at the note of scorn in Billie's voice. Mrs. Berry seized helplessly at the obvious explanation.

"Ah, she means you don't take enough care of yourself. That's like a man, especially an Englishman. You are all for sport. What is it you say? 'Let me go and kill something'!"

The colour ebbed from Tygarth's face as he waited for Billie's comment.

"You have just hit it," she said. "Once the excitement of slaughter is on him he thinks of nothing else. Why, I came home the other day with a bite on my hand as a result of his rat-hunting."

"How reckless of him!"

A shout of bottled-up laughter belled up from Forster's throat. Dyke and Beaver followed suit, while the Berry family stared in amazement. Billie had repaid her score with interest, but the China mask of Tygarth's face could not enlighten her to the fact that, false to the principle of true sport, she was hitting a man who was down.

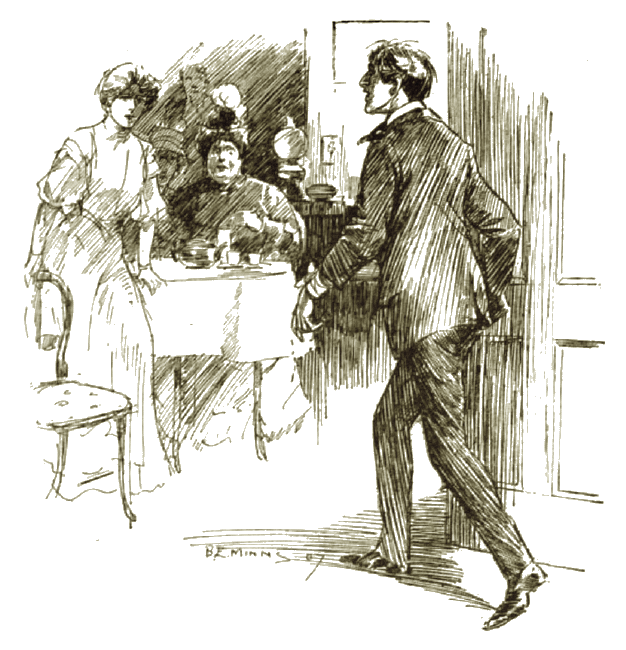

"Tabby," she said, lightly, "just run to my sitting-room and put your hand

inside my work-basket. I have left a box of chocolates there."

"Tabby," she said, "just run to my sitting-room and put your hand inside my work-basket.

"Why do you call him Tabby?" asked Pearl, curiously.

"I will spare his blushes," was the malicious answer. "Wait until he is gone and you shall have the whole story."

Only Beaver caught the look in Tygarth's eyes as he abruptly left the room, but it startled him by its strained intensity.

"She's driving that boy too far," he reflected. "Like all young things, she is ignorant of her strength."

Directly the door closed behind him Billie faced her visitors.

"You ask why I call him Tabby'?" she demanded. "Because he deserves no other name. Because he is a disgrace to the race of Englishmen. Because he is a miserable, half-baked coward."

From behind the frail door Tygarth's burning ears heard a confused babel. Billie's words had called forth incredulous dissent on the part of the Berry faction, and vehement support from Dyke and Forster. He waited for Billie's clear voice to resurrect the first discreditable incident. Then he rushed down the passage in the direction of the sitting-room.

When Billie stopped at length in her recital, through sheer lack of breath, she saw she had wasted her eloquence, for the Berry family was apparently unconvinced. The girl appealed anew to her male belongings, but Mr. Berry shook his grizzled head.

"That's the smartest two-year-old I have seen out here for many a cold day," he said, dryly. "And I reckon, p'r'aps, an old man like me can size him up better than you fine bucks. We don't run against each other."

"That's about it, pa," chimed in Mrs. Berry. "These young men are jealous. Such a nice manner he has too. I will never believe him a coward."

"He is," flamed Billie. "I say he is; and I am not a man."

"But you are a girl, my dear, and apparently he has not grasped the fact," was the dry answer.

"He hinted as much," said Pearl, acidly.

Billie grew scarlet under the raillery of the Berry family.

"Very well," she said. "I will prove what I have said. I am not piqued because the Tabby has not noticed me. I would not look at him, for he is a coward. See now. I have sent him to my basket. Crusty, my pet lizard, always goes to sleep there every afternoon. He lives on my roof, and the Tabby has never seen him. Mark my words, he will think him dangerous, and have a fit, for he is the biggest and ugliest specimen you could find. Now listen. You will have to acknowledge me right."

"Suppose he should kill him?" queried Pearl.

A shout of laughter drowned Billie's reply. "Kill him? Not he—he hasn't the pluck! He dare not touch a rat. There, what did I say? Oh, listen, listen!"

She opened the door, and her visitors rose and stood, with strained ears, in a semicircle in the doorway. As they listened, from a little way farther down the passage and muffled by closed doors, came the sound of a cry of fear. Then followed strange confused noises, as if someone were furiously rushing round the room. A piece of furniture, apparently, was thrown over with a loud thud. The sounds died away after that, till the silence was shattered by the crash of broken glass.

An expression of doubt broke over the serenity of Theophilus Berry's hatchet face. He beckoned to the others.

"Get back to the drawing-room," he said. "We'll see this thing out. We'll be in at the death."

They had barely re-seated themselves, when the door at which they were all

staring was thrown open, and Tygarth staggered in. The change in the youth

was incredible. His face was flushed, and in his blue eyes burned a light of

triumph. A bandage was tightly fastened round his wrist and his tie was

crooked. He crossed over to Billie, lurching at every step.

Tygarth staggered in.

"I've killed him," he shouted. "I've killed him."

Billie turned pale. "You have killed him?" she repeated. "Oh, how could you? You low, cowardly brute! You've done it for revenge. You've killed my pet. Oh, I hate you, I hate you!"

Tygarth's jaw fell as he listened to the vehement words. All the joy was whipped cleanly off his face.

"Your pet?" he stammered. "But—it was dangerous."

"Dangerous It would not hurt a mouse."

"But it bit me," Dennis persisted. "Look!"

He pointed to his wrist.

Billie's scornful eyes flickered alertly over the stained bandage.

"Lies won't serve you," she said, instantly. "That's a cut; it is no bite."

A confused expression stole over Tygarth's face, and he rocked slightly.

Theophilus Berry exchanged a glance with Dr. Beaver.

"It's a cut," persisted Billie. "Done with glass, and from a broken bottle. You can't deny it."

"No, no; but—"

Dennis's voice trailed off into a mumble. All his strength seemed concentrated in an effort to keep his heels together; but it was plain by the beaten look on his face that not one of Billie's words missed its billet.

"Don't say another word," she commanded, sharply. "You must get up a little earlier in the morning to get the better of an Australian girl. I have eyes. Now, listen. To sustain your reputation for courage you have killed a perfectly harmless animal, and you couldn't even do that without Dutch courage. You have been drinking. You reek of brandy. You are not fit to be in a lady's presence. Go this instant, you—you—you Tabby!"

Tygarth turned on his heel. "Remember, I did it for you," he said, thickly. Then his head fell, and were it not for Beaver's arm he would have slid to the ground. With a nod to the doctor Berry slipped round to the other side, and, thus supported, Tygarth staggered from the room.

Directly he had gone a storm of voices broke loose. Reckless of her visitors, Billie prolonged the scene by bursting into tears—half in sorrow for her pet and half in anger against the Tabby. The Berry girls looked miserable and uncomfortable, while Dyke and Forster groaned for vengeance at every convulsive wriggle of Billie's shoulders. Mrs. Berry alone displayed a spasm of forbearance.

"My dear," she said to Billie, "you must not judge the poor young man too harshly. I have no doubt that such a state of nerves proceeds from ill-health. It's all diet, my dear. With proper feeding—"

"All the feeding in the world would not put one drop of red blood into his putrid, blue-blooded veins," growled Forster. "He is rotten, through and through."

Billie dried her eyes. "He did it for my sake," she said, faintly. "Did you hear his crowning insult? My darling Crusty!"

She spoke tenderly, yet even the sweetest cadences of a mourner's voice are powerless to quicken the dead or to explain the sudden resurrection that followed. For, at the sound of his name, a huge green lizard suddenly shot, with a ripping noise, up the reed curtain, and hung on to the cornice. With fascinated eyes, everyone watched him.

"Crusty!" screamed Billie. "It is—it is Crusty!"

For a few seconds all stood in a ring, worshipping the motionless reptile. Then Mrs. Berry's placid voice rippled through the ferment of excitement.

"What I want to know," she remarked, "is this: What did that young man really kill?"

Billie sprang to her feet. "Come along, all of you," she cried. "We'll soon find out."

They flocked out into the corridor in a confused heap, Mrs. Berry flapping along in the rear. As they passed one of the bedrooms they heard the sound of footsteps passing up and down. Berry's wizened face appeared through a slit in the door.

"Forster, Dyke, you two—come in here and lend a hand," he shouted.

The women rushed on into the sitting-room. It was in a state of disorder. A couple of chairs were overturned and a cluster of roses lay strewn on the matting. Billie's eyes went instantly to the bowl in which the flowers had stood, and she gave a faint shriek to see that the water was of a deep crimson colour.

But her cry was swallowed up in a yell from Mrs. Berry.

"Look!" she shrieked.

Something black was hanging from the basket. Ruby touched it lightly, and then recoiled in horror as it gradually slid to the ground. It seemed to the terrified women, as inch after inch slowly descended, that there was no end to the hideous spectacle. But at last, with a sudden rush, the whole weight of the creature fell with a soft thud, and they saw on the ground the carcass of a deadly swamp-snake. Its coils still twitched convulsively, but its head was crushed to the semblance of a flat-iron.

With a recollection of Billie's former outburst, Mrs. Berry instinctively produced her handkerchief. But Billie did not cry this time. She only repeated her former remark, "He did it for my sake." Then she added, slowly, "I have taunted him to his death."

"Nonsense, my dear," said Mrs. Berry, cheerfully, although she wiped her eyes, "the young man knew what to do. He took proper precautions, and acted promptly. This explains everything, blood, brandy, and all. They will bring him round all right. It will be a slight attack of blood-poisoning, perhaps, and after that, why, it will only be a question of diet."

But Billie waved aside all comfort. Her strained ears only heard the sound of footsteps in the adjoining room, that passed and repassed with measured tread.

The afternoon wore away. When the evening breeze was springing up the door of the room adjoining the sitting-room was slowly opened, and Theophilus Berry, pale and exhausted, limped out into the corridor. A shaft of red sunlight dazzled his tired eyes, so that he nearly stumbled over a little figure that was kneeling beside the door. Though white and limp, in her battered finery, he recognised his radiant hostess.

She looked up at his grim face, and saw that it was scored with the signs of a conflict waged against the Silent Adversary.

He regarded her sternly.

"You are to blame for this, young woman," he said, gravely.

Billie bowed her head in anguish.

"Don't tell me!" she cried. "Don't tell me Tabby is dead!"

For answer the old man drew out his large half-hunter.

"The Tabby died two and a half hours ago," he said, slowly, "but the tiger

in a man dies harder. Tygarth of Tygarth will live."

"The Tabby died two and a half hours ago," he said, slowly.