RGL e-Book Cover ©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover ©

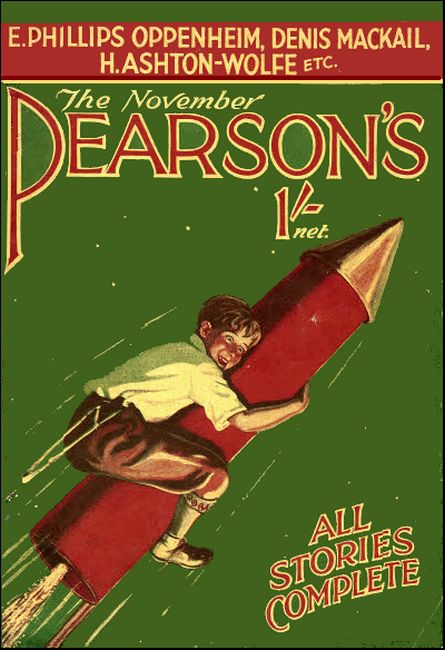

Pearson's, November 1928, with "The Scarecrow"

"THIS is death!" thought Kay.

It had come so suddenly that she felt no fear. The first pang of horror had not yet stirred within her brain. She was numb with sheer surprise.

A moment ago, she had been laughing into the eyes of a man whom she believed to be her friend. They were dull eyes, dark in colour.

Suddenly, they had grown dense as mud, and then burst into a green flame. Even as she stared, hypnotised by the change, his fingers shot out and gripped her throat.

The supper-room was of discreet arrangement. Other couples were whispering on the other side of the screen. The orchestra jerked out jazz in a deafening blare.

Kay had one moment of stark realisation. Rescue seemed hopeless. The fingers around her neck were clamped like an iron vice. Already everything was beginning to swim.

"The end!" she thought.

Then it grew dark.

THAT was over three years ago. Today, Kay was, apparently, not a penny the worse for her experience. She carried no scar on her throat, and only the least bruise on her nerves.

A waiter—who had miraculously chanced to glance round the screen—had been her salvation. Afterwards, she had a conversation with the head doctor of the mental hospital where Waring was confined.

"It was such a shock," she said, "when he suddenly turned on me, because I always thought he liked me—quite."

"May I ask the exact nature of your relations?" inquired the doctor.

"He'd asked me to marry him," answered Kay frankly, "and I had refused him. But we went on being friends. I had not the slightest idea that he harboured any grudge."

Dr. Perry smiled down at her, for he liked her type; a healthy bobbed-haired girl with resolute brown eyes.

"I hope you will try to forget all this bad business," he said. "Remember, you've now nothing to fear."

And now, for the first time in three years, Kay was afraid.

It was all William's fault.

William was the man to whom she was engaged. He was a doctor in the nearest town, and he rang her up whenever he had a chance. The wire was their blessed line of communication, and Kay rushed to the telephone the instant she heard the preliminary tinkle.

She was about to broadcast a kiss, when she was arrested by his words.

"Look here, Kay. I've news. But—don't be alarmed! There's nothing in the world to be frightened about."

And then, of course, she began to feel afraid.

"What's the matter?" she asked.

"Well—Waring's escaped."

Involuntarily, Kay glanced out of the window. In front of her was an expanse of bare fields, with low hedges, running to meet the white skyline. It looked windswept and very empty.

She laughed, to show William Tree that she was not afraid.

"Well, if he comes here, I shall be in the soup."

William hastened to reassure her.

"I'll be over with you as soon as my old stinkpot will bring me. Don't worry about Waring! I'll fix everything all right."

Smiling, Kay hung up the receiver. It was a definite comfort to know that she would soon be seeing William. As he resembled an ardent pugilist rather than a soothing young physician, the mere sight of him would be bracing.

She lit a cigarette and sat down to think. But her thoughts were curded with memories of the old hectic life, when she had been an art student at Chelsea, and the harmless flirtations, which had culminated in the tragedy of Waring.

Again she saw the tawdry restaurant revolving around her in mad circles of light and colour, as the fingers tightened round her throat.

She shuddered. It was unpleasant to reflect that, at this moment, Waring was in her neighbourhood—hiding behind outhouse or hayrick—picking up her trail. He might be twenty miles away—or he might be near.

Unpleasant, too, to dwell on her isolation. She and her mother were alone on the chicken-farm, for they could afford no outside labour. And her mother—called by maternal request 'Milly'—was, at this juncture, hopeless.

In other respects, however, she was the mainstay of their speculation, for, while Kay did the rough land-work, she tended the incubators, with excellent results. The worst thing about her was her appearance; a featherweight of a woman with hollow rouged cheeks, she looked ridiculous in the trousers which were her idea of a smart country outfit.

Kay shook her head in decision.

"Milly musn't know."

She walked to the window and looked out over the checkerboard of fields. The nearest bungalow was more than a quarter of a mile away. She could see the telegraph wires which bordered the main road, and also her own solitary line, shaking in the wind.

But, with the bareness, came a sense of security. She was grateful for the absence of undergrowth with its sinister suggestion of concealment.

Suddenly, as her eyes wandered on, her heart gave a sharp double-knock and then seemed to stop.

Standing amid the young trees of the cherry orchard, was a man.

THE next moment she burst into a peal of laughter.

Her man was a scarecrow.

She had made him the preceding evening—shamelessly neglecting her chores and her proper share of work, in the thrill of a new job. Her artistic training had assisted in his manufacture, so that he was a padded masterpiece of reality.

To help the illusion, the scarecrow was not dressed in the usual rags. In the absence of these—and reflecting that weather could not spoil it, during the short time that the cherries were ripening—Kay had clothed her dummy in a weatherproof left behind him at the bungalow by her brother, who was on a ship.

Its collar was turned up to meet nearly the broad-brimmed slouch hat. Big boots, with padded leggings and stuffed gloves completed the outfit.

IT was almost dark when her task was completed. This was the first time she had seen the scarecrow by daylight.

It had given her a distinct shock. Her nerves were still quivering, as she stood gazing out of the window. The scarecrow was so grotesquely lifelike. In the distance, he seemed to assume a real personality. His movements appeared to be independent of the wind. As she watched it, she almost expected to see it walk from the orchard.

She began to grow nervous.

"I'm sure I never made that," she murmured. "It looks alive."

There was no time for idling, for she had yet to visit the egg-house. But, even as she took out the key, she knew that work was impossible, unless she first satisfied herself about the scarecrow.

She was surprised at her own distaste. As she swung open the gate leading into the orchard, she recoiled instinctively at the sight of the figure lurking amid the dwarf trees.

It seemed to be waiting for her. At any moment—she expected it to spring.

"Absurd!" she said aloud.

Screwing up her will-power, she ran towards it, like a young war-charger. And, as she came nearer, it lost its lifelike outlines, and became—quite definitely—a stuffed dummy.

"Thank Heaven!"

In that half-sob of relief, Kay learnt the measure of her fear.

Then, at the sound of a familiar hoot from the lane, she dropped the key of the egg-house on the grass, and rushed back to the bungalow. She reached it, just as the dilapidated car chugged to the door.

Although not given to demonstration, they hugged each other.

"I'm still here," laughed Kay, releasing herself. "You'll never get rid of me, and you'd better give up hoping."

Then Milly appeared, and before Kay could warn him, William had blurted out the situation.

"You've both of you got to clear out this instant, and come back with me into the town," he commanded. "It's only a question of hours. Dr. Perry and his staff are out, combing the district."

Kay—a big bonny girl in breeches though she appeared—was ready enough to go. The opposition came from an unexpected quarter—the fragile Milly.

"The idea!" she exclaimed. "Do you expect me to leave my chicks and incubators, at this critical stage? It's monstrous."

William and Kay beat themselves, in vain, against the wall of her resolution. She refused to hear argument.

"All I know is," she declared, "that every penny I possess is wrapped up in this farm. And as for Waring, I'm not frightened of him. I always found him most quiet and unassuming. In fact, quite impossible. Besides, I had some experience in that Chelsea riot of Kay's."

As William groaned, Kay's face suddenly lit up.

"Milly's right," she asserted. "We're safer here. To begin with, we don't know that he will want to attack me again. And if he does, how can he possibly find us here?"

William smoked in silence for a time.

"That's true," he said presently. "Presuming it is a case of l'idée fixe, he can't know where you are. The only way he can find out is through me."

"You?" cried Kay.

"Yes. He connects us. He was jealous of me before he went off his rocker. He'll probably make a bee-line for Chelsea. Do the people at your old studio know your address?"

Kay shook her head.

"There have been relays of tenants since then. The tide has long ago washed away all traces of poor undistinguished me."

"Good. Well, he'll do a bit of lurking there—and then he'll stalk me."

Kay promptly clapped his cap upon his head.

"Then back you go, my lad, before you give the show away."

Even as she spoke, a shadow chased away her smile.

"You don't think he's already followed you here?" she asked.

"Not he," said William. "He's not had time to get back from his Chelsea lurk. I believe if I do a bit of lurking myself, he'll step into my trap, and then you'll be safe again."

KAY held his arm rather tightly as they walked towards his car; and William's kiss, too, was lingering—and his voice slightly husky.

"Bless you and keep you safe! I—I don't like the idea of leaving you two women alone, without a man."

Kay began to laugh.

"But we have got a protector. One of the best. He scared me, and he'd scare off anyone."

Still laughing, she ran him round to the orchard-gate, and pointed to the scarecrow.

"Look! There's our man."

TOWARDS evening, the wind rose yet higher, driving before it sheets of torrential rain. In spite of her common sense, Kay dreaded the hours of darkness. Their ugly matchbox bungalow seemed no protection against the perils of the night. She heard footsteps in every gust of wind—voices in every howl. Sleep was out of the question, and she made no attempt to go to bed.

"If I have to die, I'll die in my boots," she resolved.

Rather to her surprise, the valiant Milly shared her vigil, although she asserted that her anxiety was on the score of the roofs of the chicken houses. Together, the two women sat in the lamp-lit sitting-room, listening to the rattle of corrugated iron, the slash of the rain against the windows, and the shrieking of the wind.

And, as Kay waited, those tense moments of ordeal at the Chelsea restaurant took deferred payment of her nerves. The menace of Waring overshadowed his reality. He seemed always to be just the other side of the wall, outside the window, outside the door; watching, waiting, listening—gloating over her distress.

As the hours passed slowly and the uproar increased, she felt that she would almost welcome his actual presence—as something she could get at grips with—rather than this long drawn-out torture of suspense.

Presently, a sigh from Milly distracted her attention, and she saw that her mother had fallen asleep—one rouged cheek pressed against the tablecloth.

She stirred the fire, and, having glanced at the clock, nerved herself to unbolt the window.

To her relief, the night was over. Vivid white gashes striped the torn sky.

"The dawn!" she cried joyfully.

She thought vaguely of making fresh tea; but—overpowered with sudden weariness—she sank into the nearest chair and dropped into a deep sleep.

Dr. William Tree also spent a bad night. On his homeward way, his ancient bone-shaker struck permanently, so that he had to accept a tow back to the town.

His first action had been to ring up the sanatorium. Dr. Perry, who was obviously distraught with worry, had no news beyond the fact that it was believed that Waring had been recognised on the London express.

"Chelsea," murmured William.

He went to bed feeling annoyed and worried, and lay listening to the buffets of the wind. Several times, he thought that someone was making a forcible entry through his window; and it struck him that his own jerry-built villa, on the fringe of the town, must be a fortress in comparison with the lonely bungalow, exposed to the full fury of the storm.

About seven o'clock, he felt he could ring up Kay, without shortening her sleep, and he dashed to the telephone.

After waiting impatiently for several minutes, the operator spoke down the wire.

"Sorry, but the line's out of order."

William's heart grew leaden with apprehension.

"Why?" he snapped. "What's wrong?"

"It's the gale," explained the operator. "There are lines down all over the country."

William accepted the explanation, but he did not like it.

His young practice was still in the flopping stage and his case-book was awkwardly spaced. It would be impossible to get out to the bungalow until the late afternoon; but he decided to express a letter which would reach Kay that morning, to cheer her with news of his intended visit.

He dashed off his note, meaning to cycle with it to the post office, before breakfast. Just as he was on the point of leaving the surgery, however, his ears caught the exaggerated sound of laurel-bushes scraping against the thin outside wall of the villa.

In a flash, he concealed himself behind the door and waited.

The lower sash of the open window was lifted still higher, and a man slipped into the room. William had a vision of a furtive figure and an unshaven blur of face, as the intruder tiptoed to the mantelshelf and pounced on the letter addressed to Kay.

It made William sick to listen to his exultant pants and chuckles, as he gloated over his prize. He felt his own muscle, and thanked his Maker for endowing him with supernormal strength.

TEN minutes later, Dr. Perry was listening to his breathless but triumphant message.

"Dr. Tree speaking. I'm holding your man here. How soon can you lift him?"

"Immediately," was the prompt answer. "I can just catch the express. That'll be quicker than car, and bring me in at nine-thirty. Hold him, whatever you do. He's cunning and slippery as an eel."

William rang off, and then called up a colleague to take his morning round. Deciding to postpone his meal, since it was doubtful whether the brain-specialist had yet breakfasted, he sank into a chair, to wait, in lethargic relief, after his strain.

Presently, he glanced at the clock. It was twenty minutes past nine. His responsibility was nearly over. He decided to walk to the gate, in five minutes' time, in order to greet Dr. Perry.

He drew a deep breath at the thought. Heaven alone knew what it would mean for his peace of mind, when he knew that Waring was safe back in the sanatorium.

He looked up, with a start of surprise, as his housekeeper opened the door and Dr. Perry hurried into the dining-room.

"Got him safe?" he asked.

"Boxed and barred."

"Good."

The specialist wiped his brow and accepted a cup of coffee.

"A couple of my men are coming along directly," he explained. "I hadn't time to wait for them. The instant I got your message I dropped everything and came. He'll take some shifting."

"He's a bit of a man-eater," admitted William. "I'm very sorry I didn't meet you, Doctor. I fully intended to."

As he spoke, he glanced at the clock. It was still twenty minutes past nine.

"Hullo!" he exclaimed. "Clock's stopped. What time d'you make it?"

The specialist glanced at his watch.

"Twenty to ten. A clock that stops just about the right time could be a source of real mischief," he added thoughtfully.

"Quite," agreed William. "Was your train late?"

"I didn't catch the express, after all. Lost it by a minute. I came by car, but I stepped on the gas."

He stopped to watch the rain which was pelting against the window. It reminded him of something.

"By the way," he said, "when the rain came on, I couldn't stop to put up the hood. And, as I didn't want the seats to get soaked standing outside, I took the liberty of running the car into your garage."

William's face turned grey.

"The garage?" He spoke with an effort. "But—it was locked."

"Not locked. A bar across the staples."

"I know."

William leapt to his feet.

"Hurry, man!" he cried. "You've let Waring out!"

As he dashed through the door, his eye fell upon the clock, and he reflected bitterly, that had he been waiting at the gate, as had been his intention, the tragedy would have been averted.

For a stopped clock—the most harmless object in its futility—can, on occasion, become potent with the powers of life and death.

WHEN the two men reached the shed—which served for garage—the double doors were wide open and the car had gone.

They stared at each other, in stunned horror.

"Didn't you see him when you ran your car in?" asked William.

"No. It was dark and he was possibly hiding behind the door. Why—in Heaven's name—didn't you lock the door?"

"Key was lost, and I hadn't bothered about it, because no one would want my old stinkpot. And the garage seemed the safest place for Waring, as it was without windows. I'd warned my housekeeper and the surgery-boy—and there was no one else."

"But why didn't you truss him up?"

William shrugged wearily.

"What with? I keep bandages in my surgery, not rope. We had the devil of a dust-up. By sheer luck, I knocked him out, and when he was groggy, managed to drag him to the garage."

"But—later?"

"Later? I was all in. Think I'd risk a second fight in the garage, and probably get knocked out myself? I thought I'd wait for you and your men to tackle him. The chances were a thousand to one against anyone letting him out, and he'd be there now, but for that infernal clock."

Dr. Perry shrugged his shoulders impatiently.

"Well, there's no time to waste. We can trace him through the car. That is, if he's not too cunning to dump her, once he's got clear away."

SUDDENLY, William's mind recovered from its shock. He had a ghastly recollection of his letter to Kay shaking in the fever of Waring's clutch.

"My God!" he cried. "He's gone after the girl!"

It taxed Dr. Perry's specialised training to calm his frenzy, and restrain him from riding off on his old push-bicycle, in pursuit. He was still shaken by his brain-storm, when the car—hired, by telephone, from the nearest garage—splashed over the muddy road, on its way to the bungalow.

The sky was blotched with heavy clouds, which travelled over the heavens and burst in local storms, like slanting black wires. Sometimes, a white gleam of light would pass, like a searchlight, over the fields. The scene was unearthly and foreboding as a bad dream.

William sat in dumb agony, wrenching his thoughts from the fear that they might be too late. Yet he was stung by the irony of the rescue. They two were responsible for the situation. They had unloosened a ravening Waring upon a defenceless Kay. One had supplied her address and the other had given him liberty and a car.

At last, they reached the bungalow, set amid its cropping chicken-coops and pens.

William rose up in his seat and then gave a shout of joy.

"They're safe! Hullo!"

He pointed to a rising slope, where two figures were outlined against a livid sky; one, in trousers and incongruous dangling green earrings—the other in short wine-red skirt and sweater, facing the wind with the vigour and radiance of youth.

Dr. Perry gave them but one glance.

He, too, had risen in his seat and his keen eye had espied a far-off object in a tributary lane.

"The car. Ditched. Look out, Tree! He must be somewhere near."

"If he is, we'll soon have him out," responded William cheerfully, leaping from the car.

"What's that?" asked Dr. Perry sharply, as they passed through the gate.

William laughed.

"Took you in, too? That's Kay's scarecrow."

"A mighty realistic one." Dr. Perry gave it a longer look. "Come, there's not much cover here."

It was the work of a few minutes to search the chicken-houses, although William stopped in the middle, to greet Kay and her mother and to explain the situation.

Fortified by daylight and the presence of two men, both remained calm.

"He might have slipped into the bungalow, while we were out," said Kay. "It's plain he's nowhere here. Come and look!"

Dr. Perry, however, lingered. His eye swept over field and low hedge. There was no ditch or furrow, and hardly cover for a fox.

Then his glance was once again caught and arrested by the scarecrow.

He touched William's arm and spoke in a low voice.

"I'd like a closer inspection of that gentleman."

The two men advanced warily: but, as they drew nearer the scarecrow, the illusion of humanity faded.

Dr. Perry laughed.

"A fine take-in," he confessed. "Your young friend has some idea of anatomy. Studied art, you say? Well, now for the bungalow."

The scarecrow hung mute and lifeless. It had played its part in the grim conspiracy. It had held the eye and distracted the attention of those who might have made a closer search.

Directly the voices had faded behind the closed doors of the bungalow, there was a stir, followed by a disruption, in a large pile of leaves, rotting into mould.

From under the heap, emerged an earth-stained figure, which writhed its way swiftly over the grass, to its ally—the scarecrow.

A MINUTE later, the scarecrow hung again on its supporting poles. The collar of its weatherproof met the brim of its hat; its hands and legs looked no more lifelike than the padded gloves and breeches, which were buried with the rest of the straw, under the leaf-mould.

There was only one difference. A button—wrenched off, in the mad haste—was missing from the middle of the coat.

But the scarecrow was content. It had only to wait. It must not stir a muscle, lest someone should be watching from the bungalow. Its two enemies were there. And to hang from the pole, like a bat, was easy, for while the body was slack, the mind could wander.

The scarecrow knew that she was here. It had heard her voice as it lay under the pile of leaf-mould. But there was another voice beside, and he wanted her—alone.

It knew it had but to wait, and she would come. On the ground, beside it, lay a key. She was always dropping keys. Once, she had dropped the key of her flat in the scarecrow's studio, and, because it had grasped the obvious implication, she had made a terrible scene.

She would fool men no more. The scarecrow was waiting for her to come. Two minutes would suffice—and then, its enemies might come.

They would find nothing left of any use to them.

INSIDE the bungalow, voices were raised in discussion and laughter. Only Dr. Perry chafed at the delay, for he was anxious to pick up the trail. Milly—who had donned femininity with high-heeled French shoes and a long red cigarette-holder—tried to charm him in vain.

"Waring can't be far off," he asserted. "You and I'd better move on, Tree."

William shook his head.

"If he's lurking around, I'm not going to leave Kay."

"Oh, I feel quite safe now." Kay laughed happily. "But I'll own up, I simply can't face another night."

"You shan't," declared William. "If he's not caught by then, I'll sleep in the sitting-room. But it will be safer to catch him. Perhaps, I'd better look around for about half an hour."

Dr. Perry clinched his decision.

"Wisest course, Tree. We're bound to get him if we're systematic. I'll follow the road in the car, while you beat the fields."

"In this rain, and without a coat?" protested Kay indignantly.

Then her face cleared.

"I have it. The scarecrow is wearing Roly's old Burberry. You'd better have that."

"Righto. That's a clinking dummy of yours, Kay."

She gurgled.

"I loved making it. And I feel a worm to strip it, when it protected us so nobly through that horrible night."

William walked to the door, but turned, on the threshold, at Kay's voice.

"I just want to see you, one minute, in the kitchen."

He knew what she meant. He had not kissed her yet. With a sheepish beam on his face, he hastened to follow her into the adjoining room.

Fate must be blind, for how otherwise, could she deliberately fight against the helpless? Even while the lovers lingered—Kay's cheek pressed against William's tweed shoulder—the wind shook the last drop from the inky cloud.

William—self-conscious but aloof—appeared from the kitchen, in obedience to Dr. Perry's hail.

"Sorry to keep you waiting. Kay wanted something nailed up. Hullo! It's stopped raining. Good egg! I won't bother about that coat now, Kay. Sooner we're off the better."

Milly kissed her hand to the men, and then called to Kay.

"When you've seen them off, just take these eggs to the egg-house, angel."

"All right."

Kay picked up the basket and then turned to the empty nail on the wall.

"Now, what have I done with that blessed key?" she cried, "I know I had it yesterday."

"Always losing keys," laughed William.

"Think back," advised Milly.

Kay proceeded to think back, to Dr. Perry's ill-concealed annoyance. But, suddenly, she gave a cry of triumph.

"I know. I was just going to date those eggs, yesterday, when I heard William's stinkpot. I must have left it in the orchard."

She walked with the men to the orchard, and the scarecrow heard her voice. At the sound of her laughter, it tensed its muscles. The waiting was nearly over.

HER hand on the gate, she turned to wave farewell to the two men. She felt happy in William's presence, and in the warm glow of her relief. The night held no more terrors for her. William would be there. Even the sun was going to shine for her.

Her joy was visible in the radiance of her smile. The brightening light bronzed her brown hair. William thought he had never seen a sweeter picture.

"Do look at my scarecrow," she said with a chuckle. "It's waiting to make love to me. Wouldn't you like to touch it and see if it's alive?"

Both men laughed as they shook their heads.

"You don't get us twice," said William. "We've been had, both of us."

"I'm not surprised," said Kay. "He scared me, and I made him. Good-bye—and don't be long!"

The men turned away and she opened the orchard gate, just as the sun broke through the cloud.

It travelled over the field and fell upon the scarecrow. As it did so, a spark of fire glinted from the gap in its coat, where the button was missing.

Kay only noticed her key. She was running towards it, when she felt William's hand upon her arm.

"Come back!" His voice was low and tense. "Perry, make ready! That scarecrow's wearing a watch-chain."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.