RGL e-Book Cover ©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover ©

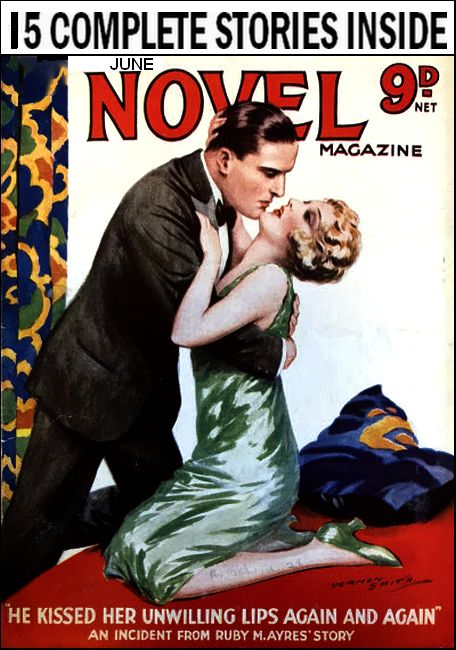

The Novel Magazine, June 1928, with "The Uninvited Guest"

"LOOK! She's burning the table cloth!"

The country girl cried out in horror as the ultra-smart, Eton-cropped young woman at the next table pressed her cigarette-end against the snowy damask.

The town youth—who was the country girl's cavalier—wrinkled his nose in disgust.

"Rotten bad form Gives her away. I'll bet anything she's a crasher."

"Crasher?" Echoed the country girl, whose name was Teddy. "Whatever is that?"

They were in the supper room of an expensive mansion, which was the scene of one of the biggest balls of the season. Delphiniums and madonna lilies were banked up almost to the deep blue Italian ceiling, and, through the great crystal doors, Teddy could see the red lacquer and gilt of the famous Chinese salon.

"Marvellous!" she whispered.

Outwardly she resembled any London debutante She was both slim and shingled, and dressed in a petal-frock of orchid mauve. Her liquid powder and lipstick were of the right shades, in these days of sales catalogues, any country girl who knows her job, need not look classified.

But, inwardly, Teddy was about as sophisticated as a child at its first pantomime. It thrilled her, just to remember the last night she had stood at the garden gate at home, staring at the dark, quiet fields, scented with new mown hay. Within 24 hours the express had rattled her up to London. She had barely been enfolded within the powdery hug of her old schoolmate, Rosamond when Rosamond's special cavalier had called at the tiny basement flat, to carry them off to the ball.

Piccadilly was jammed with traffic and glittered with the lights of congested vehicles. To Teddy it was a dark lane, stuck with fireflies, as, steeped in enchantment, she lay back while the others cursed each traffic block.

Her happiness suffered its first check when Rosamond's cavalier informed her of the existence of the crasher.

She looked at him in real dismay.

He was a typical town youth, charming and correct; but he had an uneasy feeling that he would rather be dancing with Rosamond.

"Crasher'," she repeated. "Is it really true, Mr. Parnell, that people in London come to balls without invitations."

"Crowds," Parnell assured her. "Easiest thing in the world. Your hostess doesn't one-half of her guests. You see, she broadcasts for dancing, men. Take me. I was told to bring a friend—but I brought you."

"Sweet of you," said Teddy, gratefully, "But it makes me feel quite guilty to think I don't know my hostess."

As she spoke she looked up and met the full gaze of a man who, in spite of the throng, had arrested her attention and held it, by his air of high adventure.

Young Parnell smiled.

"I'm vouching for you. But, seriously, this crasher business is overdone. I was at a dance last week where there was a famine, half-time. In common decency the crasher should bar the buffet. Hulloa, Rosamond!"

His face grew wistful, as Rosamond, beautiful in a sheath of crushed golden tissue, appeared—partnerless.

Teddy was growing awkward, for Parnell was Rosamond's property, when the situation was suddenly saved. The fascinating stranger had whispered in. Parnell's ear, and he had mumbled an introduction.

Next minute they were wandering together towards the ballroom, and the adventure was spiced with the personal element.

Teddy looked up into her partner's blue-black eyes—chill as Arctic seas, they held the glint of high adventure.

"You're a friend of Mr. Parnell's, I suppose," she said. "Have you known him long?"

"Long enough to know him." He looked at her and added abruptly:—"Are you from the country?"

Teddy made a grimace. She hoped that her dress looked like the French model from which it had been copied.

"Now, I wonder how you knew that," she said forlornly.

"I didn't. I ask all my partners that. In hopes. Once I fell in love with a country girl. Adorable creature. Freckled like a cowslip. She need to water the milk for market. I helped her do it. I staved on in the country until my cash gave out. I was bitten by bulls, but I stuck it—for her. Since then I've been searching for another country girl.

"Why?"

"To fall in love again."

"But you must know crowds of London girls, if you want to fall in love," said Teddy. "I expect you know lots of people here."

He threw her what Teddy would describe as "an old-fashioned look.

"Not so many. Do you?"

"Of course not. I'm a stranger. But, according to Mr. Parnell, there are a lot of other strangers here. Uninvited guests, I mean.... Look! There's one."

They had halted by the carved mantelpiece, which was one of the marvels of the mansion. A sleek-haired woman, with geranium-red lips, repeated the gesture of the girl at the supper table. She put down her cigarette and left it smouldering on the mantelpiece.

Teddy sprang forward and picked it up.

"That's the second time I've seen that happen tonight. Appalling. Take it from me," she added with proud sophistication, "that woman's a crasher."

Her partner began to laugh.

"No, you're mistaken. That lady's well known in society. Chucking about her cigarette stubs is only one of her playful little tricks."

"Well! I call it an abuse of hospitality," said Teddy.

"Quite. But that sort of graceful gesture is hot characteristic of the crasher. He's generally an acquisition—a good dancer and wel-behaved; finally, he's a bit of a buccaneer and does it for the sport. I rather admire him, myself.'

"You can't!" said Teddy.

"Why not? It shows a spirit of adventure. Life's so tame. So far the game's dead easy, but you never know when you are going to be shown up. I don't envy the crasher that. Hot. Let's go out!"

They crossed the road and sat under the shade of the plane trees that fringed the park. The foliage glittered like jade in the light of the electric standards. Red buses lurched by in the road. From the house floated the strains of the band. Teddy thought of last night; the empty fields, only the harsh cry of the corncrake and the gurgle of the watercress-choked brook.

Her life had been empty as the night. She met men—in novels and on the screen. As she caught the smile in the blue-black eyes of the stranger, she exulted in a sense of contrast.

"You were introduced to me merely as Teddy," he said. "Another name, by any chance?"

"An awful one. I'm fearfully ashamed of it. Smith."

Her partner looked at her thoughtfully. "That's my idea of rather a useful name," he observed. "Mine is Brown. Spelt with two b's."

"Like the pencil," said Teddy. "B.B. means 'very soft.' I don't think you are that."

"Thanks. I'll return the compliment.'

"Of course." Teddy laughed. "Country girls are up to all the tricks of the trade. Don't forget we always water the milk!"

During the next hour under the plane trees, they made the joint discoveries that Brown's other name was Valentine; that he cherished a secret passion for leeks, but had an aversion for walking over the joints of paving stones.

Further—that Teddy's lucky day was Friday; that she had an ambition to fly, but had only got so far as going down a coal-mine.

"Of course," she admitted, "it was down instead of up. But it was a thrill, with real rats. Oh, good gracious! There's Rosamond."

She sprang to her feet as a slim figure in a golden tissue frock, accompanied by a black coat, appeared on the steps of the mansion.

They waved to her frantically. "Going on?" asked Brown.

"Yes. To a Mrs. Eddystone's dance, in Hertford street."

Brown pulled down the corner of his mouth.

"Oh, haven't you been asked?" cried Teddy. "What a pity."

"I've received no invitation. But—is that an obstacle?"

As they crossed the road, Teddy put out her hand impulsively.

"Good-bye. I've enjoyed to-night like anything."

"Aren't you going in to get your cloak?" asked Brown.

"No. We left our things in the car. Oh, I—I must have a last peep! It looks like a scene on the stage."

Teddy looked reluctantly through the great glass doors.

"Going on is a silly idea, just when one is nicely set," she remarked. "And it does seem so rude not to wish your hostess good-night."

"It you want to," said Brown, "there she is."

At his words, Teddy had a sharp pang of I disappointment. Brown had indicated a stout brunette in kingfisher blue.

Yet, earlier in the evening, Parnell had pointed out to Teddy the gracious lady of the mansion—a willowy aristocrat in green and silver—her beautiful hair powdered by time.

Brown had given himself away by his ignorance.

He was a crasher.

As Teddy squashed into the two-seater, she observed that Piccadilly was no longer starred with fireflies. There were only lights. Foggy lights, too, although there was no rain.

"What ages you and your man were parked outside," said Rosamond. "Was he nice, and what's his name?"

"Brown."

Parnell glanced at Rosamond.

"Rather a useful sort of name—Brown," he observed.

Teddy turned upon him suddenly.

"But he's your friend. You ought to know all about him."

Parnell laughed

"I've a bit of a confession to make. I mistook him for another chap I knew slightly. But, probably, he's one of the Browns of Peckham. And his coat was the right cut."

Both Parnell and Rosamond began to laugh. Their mirth moved Teddy to righteous wrath.

"I call that rotten. You don't know what kind of suspicious character you were palming off on me. I've read that these society crushes are thick with detectives, looking out for cat burglars."

"Don't worry," said Rosamond. "No one would carry you off, even if you paid him for it. Sheik-stuff does not appeal to the modern partner. No nerve."

Teddy was moved to defence of her late partner.

"Mr. Brown has the necessary nerve, anyway," she announced defiantly.

"How do you know?"

Teddy remained silent. Whatever happened she would not give the crasher away.

Presently Parnell stopped the car. "Let's park here!" he said.

It was easy to tell at which house the ball was in progress. But in spite of lights and awning, Teddy curled her lip.

"What dingy street!"

"It's only Mayfair, darling," said Rosamond. "Considered not too bad an address. For a country lass, you seem to be giving yourself airs."

"I only meant I liked the other house better," explained Teddy.

Already she felt a hundred years older than the girl of last night. She thought with longing, of the brilliant scene she had just left.

In a dream she followed the others into the ballroom. Second-rate decorations, to her eyes; dim illuminations and a poor crowd.

She heard a whisper pass between Parnell and Rosamond,

"You must find Teddy a partner."

"Quite. Why, here's luck! Teddy, our friend Mr. Brown is here, looking for you!"

Teddy blinked, as suddenly the lights grew brighter. The adventurous blue-black eyes were laughing down into hers.

Then she remembered her suspicions.

"I thought you said you'd not been invited here," she said.

"Well—have you?"

"No. But that's different." Brown laughed.

"A little thing like the lack of an invitation doesn't beep me away. I judge a house by its door knocker, and I rather fancied the cut of this one. Mercury—the god of dishonest people. Besides, I wanted to see you again."

"But think of the risk!" cried Teddy.

"Isn't that pretty cool, coming from you?"

"You mean I like risks. But I was invited to go down the coal-mine."

Brown shrugged his shoulders.

"I'm here, any way. Won't you dance?" Teddy pinched her little finger.

"I'm not sure that I want to dance with you."

"Why, what's wrong? I don't seem the success I was ten minutes ago. What happened in the car to change the whole course of my destiny?"

Teddy's lips softened.

"First of all," she said, "will you answer me two questions truthfully?"

"Nothing to do with the income tax?"

"Don't be silly! First, is Brown really your name?"

"No."

"But—why?"

"I chose that name to go with Smith."

Teddy's colour rose.

"My name is Smith," she said. "I was born and christened Teddy Smith, and I can prove it in a Court of Law."

"Think again before you swear to it!" warned Brown.

Teddy laughed.

"Of course, my name is really Theodora. But I am Smith."

"What's the second question?" asked Brown.

"Well—it's rather a personal one. But—are you really an uninvited guest?"

"Yes."

"Oh, dear!" cried Teddy, in dismay. Brown only laughed at her.

"What are you going to do about it? Expose me to my hostess? That is, if you know who she is."

"I may know better than you."

"Then point her out to me!"

Teddy looked around for Rosamond and Parnell, but they had spun away. She felt abandoned to her fate.

Her humiliation lay in the fact that she really welcomed her fate. Suddenly she decided to accept the situation. If the crasher liked to run the risk, it was none of her affair....

The Charleston claimed them. Later, when Teddy met Rosamond she spoke quite kindly of the house.

"I understand now what you mean. This place isn't so showy as the other, but it has atmosphere. That ceiling is Adams, isn't it?"

Rosamond put her tongue in her cheek as she nodded, and Teddy danced off again.

Sitting on the stairs, Brown related some of his war experiences. They meant much to him, but were not so sensational as Teddy expected.

"Didn't you get the V.C.?" she asked. "No. But I got the gate."

"But I'm sure you did something really cheeky. Held up a regiment of Germans with a penny pistol, or rescued your colonel under fire."

"I couldn't. I was my colonel. I don't know why you harp on this idea of my nerve. Are you getting hungry?

"Yes. It's ages since the last supper."

"Then we'll go down. They made a feature of the spread in this house. None of your bite-and-toothful affairs here."

Teddy cried out as she caught sight of the supper room through the glass doors.

"Fruit growing on real trees! Yes? What's that?"

A fat, powdered footman repeated his request.

"Your card of invitation, madam?"

Teddy had turned and pointed out the golden Rosamond and her cavalier, who were standing a few paces from them down the queue.

"They have mine...."

Suddenly the smile left her face as she remembered that Brown was a crasher and had no card....

The inevitable show-up was at hand.

She made a lighting decision to stand by him.

"I don't think I want any supper," she said, "Let's dance again!"

To her surprise he merely nodded to the footman as he drew her through the doors.

"You know you're hungry," he said, "and so am I."

Teddy gasped as he steered her to tactfully placed table apart from the mob.

"But you hadn't an invitation."

"Didn't need one. Mrs. Eddystone is my aunt."

Teddy felt as though a jam of ice had melted round her heart as Brown went on.

"Quaint idea this, of showing cards. There were 200 extra guests at my aunt's last affair and some people never got a crumb, so she vowed she'd be even with the crasher. I hear there's some idea of wearing a badge."

"But why didn't they ask you for our invitation cards at the door?" asked Teddy.

"Because it's impossible to know who have already shown theirs, with people drifting in and out all the time... But would you excuse me a moment? There are some people over there I know."

In blissful content Teddy watched him fight his way through the crowded room. Then her glance shifted to the glass doors of the supper room.

She was just in time to see Rosamond and Parnell interrogated by the powdered footman, so she stood up in order to attract their attention.

Her movement caught Rosamond's eyes. Her face scarlet with mortification, she made a frantic signal to Teddy before she practically ran away on the heels of the vanishing Parnell.

In incredulous horror Teddy watched and interpreted the ignominy of their departure. In that moment she realized her own position.

She was a crasher.

She had crashed into the houses of total strangers—smoked their cigarettes, eaten their food, drunk their wine. That she had been an innocent offender made no difference to the cold fact.

As her brain grew clearer she understood the reason why they had left their wraps in the car and made such informal entries. Unused to London, she had thought it to be the custom.

She had been completely taken in. If she had questioned how Rosamond—a mannequin at three pounds a week—could have gained the entry to such houses, she had the explanation in the fact that the invitations had proceeded from that young exquisite, Parnell.

Looking up, she realized that the worst was in store. The footman, to whom she had pointed out Rosamond as her sponsor, was advancing in her direction.

Teddy tried to grapple with her exact problem. She knew that if a total stranger were found in any one's house, at home, he would be handed over to the police. In any case, she would be the victim of a horribly unpleasant scene. Parnell and Rosamond had made their get away, but she was trapped.

At any moment Brown might return to the table, to be the witness of her exposure.

"Not before him!" she murmured desperately.

The footman's circuitous advance was blocked by an eddy of fresh guests. It was her moment for action. Her quick eyes had already noticed a door at the far end of the room.

She slipped through the press like an electric hare, praying that the footman had lost sight of her. It was exactly like a bad nightmare, and she wished that she could wake up and find herself where she was last night, in the safety of the dark, scented country.

As she ran, her brain worked like a racing engine. The door might be locked. If it were, she was doomed. Or it might lead to the servants' quarters, in which case she was still doomed.

But she banked on the chance that it might lead to a room which would communicate with the great hall. Once there she could leave the house with dignity.

As her fingers, gripped the door handle her heart fluttered with suspense. To her joy the knob yielded easily. In another second she was on the safe side of the door with the supper room shut out. Then she discovered that both surmises had been wrong, for the door led to a spiral staircase.

"Never mind!" she said. "It will probably lead to a passage which connects with the gallery."

If she could only reach the great central staircase she would be safely shuffled again into the pack of the guests and could make a speedy exit.

It was the work of a minute to rush up the stairs. They ended in a short passage barred by another door.

She opened it cautiously, only to be met with fresh disappointment.

She found herself in a small apartment—probably a dressing room—which, in turn, led to a large bedroom. From the nearness of the orchestra Teddy could tell that this room opened out directly to the central gallery, which was her goal. She could see its door, which was slightly open, outlined in brilliant light, and could hear laughter and footsteps.

Holding her breath, she advanced a step into the bedroom. It was the most wonderful apartment she had ever seen, with its aquamarine walls and coral and diver furniture. A subdued light filtered through a great mother-of-pearl bowl, suspended from the ceiling.

Teddy took another step, when she was arrested by the sounds of a rustle and a cough.

To her horror she realized that someone was in bed. A frail old lady, in a plum satin peignoir was propped up amid the monstrous cushions of the bed.

Suddenly Teddy remembered that Brown had told her of Mrs. Eddystone's mother, who—after listening to the wireless until every station had closed down—insisted on her door being ajar in order to enjoy the dance music.

She slipped back into the darkness of the dressing room. It was maddening to be thus arrested, with safety only the other side of the door. For half a minute she considered the idea of making a dash for it.

Her commonsense rejected the plan. If the old lady screamed, she had a vision of every one pursuing her down the stair-case, with the absurdity of a comedy film.

She walked over to the open window of the dressing room. Outside was a small balcony, supported by slender iron pillars, which arose from the verandah on the ground floor.

To Teddy, who had made many an escape from her bedroom window, it was the easiest descent. The only danger lay in detection from the road.

She stood for some time in hesitation, fearing to venture. Presently, however, she gritted her teeth. It meant the murder of her orchid frock, and she kissed one fragile petal as she climbed over the balcony.

"What a night!" she murmured as she lowered herself down the pillar, foot by foot, to the sound of rending georgette.

Before she reached the bottom she knew that her luck was out. A circle of light played on her face, and she literally fell into the arms of a waiting policeman.

Resisting an instinctive desire to kick, Teddy spoke with dignity.

"Thank you. Mr. Officer. Not that I required any help. May I ask why you are detaining me?"

"What are you doing here?" was his stern response.

"Surely you could see I was merely leaving the house."

The policeman looked at her closely as he propelled her towards the front door.

"We must see about that," he said.

Teddy felt that the bad dream was growing intolerable. She felt she must wake up, or die, when she saw the tall figure of Mr. Brown on the doorstep. He won staring down the street. When his eyes fell upon her he gave a cry of greeting.

"I was just looking for you," he said. "Where did you get to?"

Teddy realized that his recognition might prove her salvation.

"Will you kindly explain to this officer that I'm a guest and not a cat-burglar?" she said haughtily. "You see, he saw me coming down from that window."

Mr. Brown's adventurous eyes lit up as she indicated the balcony. She thanked her lucky stars that she was dealing with a quick wit.

"Great!" he said. "Then you've won. What did I bet you you wouldn't do it?"

The policeman looked prim, but his disapproval vanished in the rustle of a note. Almost in the same second Brown hailed a taxi.

"I'll take you home. Nip in!"

Teddy sank back on the seat, suddenly humiliated by the shame of her adventure. She nearly broke down when she tried to explain.

"Honestly, I believed Rosamond was a properly invited guest. Honestly, I never dreamt we were crashers. Honestly, I didn't!"

"Of course not," agreed Brown. "It was a horrible suck-in for you. Now, when shall I see you again?"

"Never."

In spite of his appeals, she turned from him with averted face.

"You don't understand. I feel too humiliated. I never want to see you again. No, it's no good. Never!"

"That's done it," said Brown ruefully. "Now, will you, in turn, believe me when I tell you that I'm a crasher, too, for the first time in a pure life?"

"You—a—crasher?"

Teddy's eyes were sparkling as she turned and faced him—the chasm which divided them bridged. "Tell me all!"

"Your fault," grumbled Brown. "I was a common-or-garden guest at the first house, of course: but I wanted to see you again, so I determined to be a crasher, for the first and last time, at the Eddystones'. I went straight to that fat, powdered footman, and said, 'Didn't know my aunt was giving a dance. Tell her I'm here, at once!' I mumbled a name, and slipped him a note, feeling sure the chap wouldn't bother about the message. That was why, when we met at the supper room. I got by him, through my bluff, plus his guilty conscience. But I lived a lifetime in that second. I felt I couldn't stick being exposed before you, and I vowed I'd never crash again... What a night!"

"What a night!" echoed Teddy.

They were passing Piccadilly Circus, where once a winged god used to surmount a fountain. But, even in his exile by the Thames[*], Eros heard their laughter.

[* The famous statue was removed to Embankment Gardens in 1922 for the construction of the Underground station at Piccadilly Circus and returned to its former location when the station was completed in 1931.—Ed.]

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.