RGL e-Book Cover ©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover ©

Pearson's Magazine, December 1930, with "Waxworks"

SONIA made her first entry in her notebook:

"Eleven o'clock. The lights are out. The porter has just locked the door. I can hear his footsteps echoing down the corridor. They grow fainter. Now there is silence. I am alone."

She stopped writing to glance at her company. Seen in the

light from the street lamp, which streamed in through the high

window, the room seemed to be full of people. Their faces were

those of men and women of character and intelligence. They stood

in groups, as though in conversation, or sat apart, in solitary

reverie.

But they neither moved nor spoke. When Sonia had last seen them in the glare of the electric globes, they had been a collection of ordinary waxworks, some of which were the worse for wear. The black velvet which lined the walls of the Gallery was alike tawdry and filmed with dust. The side opposite to the window was built into alcoves, which held highly moral tableaus, depicting contrasting scenes in the career of Vice and Virtue. Sonia had slipped into one of these recesses, just before closing time, in order to hide for her vigil.

It had been a simple affair. The porter had merely rung his bell, and the few courting couples which represented the public had taken his hint and hurried towards the exit.

No one was likely to risk being locked in, for the Waxwork Collection of Oldhampton had lately acquired a sinister reputation. The foundation for this lay in the fate of a stranger to the town—a commercial traveller—who had cut his throat in the Hall of Horrors.

Since then, two persons had, separately, spent the night in the Gallery and, in the morning, each had been found dead.

In both cases the verdict had been "Natural death, due to heart failure."

The first victim—a local alderman had been addicted to alcoholism, and was in very bad shape. The second his great friend—was a delicate little man, a martyr to asthma, and slightly unhinged through unwise absorption in spiritualism.

While the coincidence of the tragedies stirred up a considerable amount of local superstition, the general belief was that both deaths were due to the power of suggestion, in conjunction with macabre surroundings. The victims had let themselves be frightened to death by the Waxworks.

Sonia was there, in the Gallery, to test its truth.

She was the latest addition to the staff of the Oldhampton Gazette. Bubbling with enthusiasm, she made no secret of her literary ambitions, and it was difficult to feed her with enough work. Her colleagues listened to her with mingled amusement and boredom, but they liked her as a refreshing novelty. As for her fine future, they looked to young Wells—the Sporting Editor—to effect her speedy and painless removal from the sphere of journalism.

On Christmas Eve, Sonia took them all into her confidence over her intention to spend a night in the Wax works, on the last night of the old year.

"Copy there," she declared. "I'm not timid and I have fairly sensitive perceptions, so I ought to be able to write up the effect of imagination on the nervous system. I mean to record my impressions, every hour, while they're piping-hot."

Looking up suddenly, she had surprised a green glare in the eyes of Hubert Poke.

When Sonia came to work on the Gazette she had a secret fear of unwelcome amorous attentions, since she was the only woman on the staff. But the first passion she awoke was hatred.

Poke hated her impersonally, as the representative of a force, numerically superior to his own sex, which was on the opposing side in the battle for existence. He feared her, too, because she was the unknown element, and possessed the unfair weapon of charm.

Before she came, he had been the star turn on the Gazette. His own position on the staff gratified his vanity and entirely satisfied his narrow ambition. But Sonia had stolen some of his thunder. On more than one occasion she had written up a story he had failed to cover, and he had to admit that her success was due to a quicker wit.

For some time past he had been playing with the idea of spending a night in the Waxworks, but was deterred by the knowledge that his brain was not sufficiently temperate for the experiment. Lately he had been subject to sudden red rages, when he had felt a thick hot taste in his throat, as though of blood. He knew that his jealousy of Sonia was accountable. It had almost reached the stage of mania, and trembled on the brink of homicidal urge.

While his brain was still creaking with the idea of first-hand experience in the ill-omened Gallery, Sonia had nipped in with her ready-made plan.

Controlling himself with an effort, he listened while the sub-editor issued a warning, to Sonia.

"Bon idea, young woman, but you will find the experience a bit raw. You've no notion how uncanny these big deserted buildings can be."

"That's so," nodded young Wells. "I once spent a night in a haunted house."

Sonia looked at him with her habitual interest. He was short and thick-set, with a three-cornered smile which appealed to her.

"Did you see anything?" she asked.

"No. I cleared out before the show came on. Windy. After a bit, one can imagine anything."

It was then that Poke introduced a new note into the discussion by his own theory of the mystery deaths. Sitting alone in the deserted gallery, Sonia preferred to forget his words. She resolutely drove them from her mind while she began to settle down for the night.

Her first action was to cross to the figure of Cardinal Wolsey and unceremoniously raise his heavy scarlet robe. From under its voluminous folds she drew out her cushion and attaché case, which she had hidden earlier in the evening.

Mindful of the fact that it would grow chilly at dawn, she carried on her arm her thick white tennis coat. Slipping it on, she placed her cushion in the angle of the wall, and sat down to await developments.

The gallery was far more mysterious now that the lights were out. At either end it seemed to stretch away into impenetrable black tunnels. But there was nothing uncanny about it, or about the figures, which were a tame and conventional collection of historical personages. Even the adjoining Hall of Horrors contained no horrors, only a selection of respectable looking poisoners.

Sonia grinned cheerfully at the row of waxworks which were visible in the lamplight from the street.

"So you are the villains of the piece," she murmured. "Later on, if the office is right, you will assume unpleasant mannerisms to try to cheat me into believing you are alive. I warn you, old sports, you'll have your work cut out for you.... And now I think I'll get better acquainted with you. Familiarity breeds contempt."

She went the round of the figures, greeting each with flippancy or criticism. Presently she returned to her corner and opened her notebook ready to record her impressions.

"Twelve o'clock. The first hour has passed almost too quickly. I've drawn a complete blank. Not a blessed thing to record. Not a vestige of reaction. The waxworks seem a commonplace lot, without a scrap of hypnotic force. In fact, they're altogether too matey."

Sonia had left her corner, to write her entry in the light which streamed through the window. Smoking was prohibited in the building, and, lest she should yield to temptation, she had left both her cigarettes and matches behind her, on the office table.

At this stage she regretted the matches. A little extra light would be a boon. It was true she carried an electric torch, but she was saving it, in case of emergency.

It was a loan from young Wells. As they were leaving the office together he spoke to her confidentially.

"Did you notice how Poke glared at you? Don't get up against him. He's a nasty piece of work. He's so mean he'd sell his mother's shroud for old rags. And he's a cruel little devil, too. He turned out his miserable pup to starve in the streets, rather than cough up for the licence."

Sonia grew hot with indignation.

"What he needs to cure his complaint is a strong dose of rat poison," she declared. "What became of the poor little dog?"

"Oh, he's all right. He was a matey chap, and he soon chummed up with a mongrel of his own class."

"You?" asked Sonia, her eyes suddenly soft.

"A mongrel, am I?" grinned Wells. "Well, anyway, the pup will get a better Christmas than his first, when Poke went away and left him on the chain... We're both of us going to overeat and over drink. You're on your own, too. Won't you join us?"

"I'd love to."

ALTHOUGH the evening was warm and muggy the invitation

suffused Sonia with the spirit of Christmas. The shade of Dickens

seemed to be hovering over the parade of the streets. A red-nosed

Santa Claus presided over a spangled Christmas tree outside a toy

shop. Windows were hung with tinselled balls and coloured paper

festoons. Pedestrians, laden with parcels, called out seasonable

greetings.

"Merry Christmas."

Young Wells' three-cornered smile was his tribute to the joyous feeling of festival. His eyes were eager as he turned to Sonia.

"I've an idea. Don't wait until after the holidays to write up the Waxworks. Make it a Christmas stunt and go there to-night."

"I will," declared Sonia.

It was then that he slipped the torch into her hand. "I know you belong to the stronger sex," he said. "But even your nerve might crash. If it does, just flash this torch under the window. Stretch out your arm above your head, and the light will be seen from the street."

"And what will happen then?" asked Sonia.

"I shall knock up the miserable porter and let you out."

"But how will you see the light?"

"I shall be in the street."

"All night?"

"Yes. I sleep there." Young Wells grinned. "Understand," he added loftily, "that this is a matter of principle. I could not let any woman—even one so aged and unattractive as yourself—feel beyond the reach of help."

He cut into her thanks as he turned away with a parting warning.

"Don't use the torch for light, or the juice may give out. It's about due for a new battery."

As Sonia looked at the torch, lying by her side, it seemed a link with young Wells. At this moment he was patrolling the street, a sturdy figure in old tweed overcoat, with his cap pulled down over his eyes. As she tried to pick out his footsteps from among those of the other passersby it struck her that there was plenty of traffic, considering that it was past twelve o'clock.

"The witching hour of midnight is another lost illusion," she reflected.

"Killed by night clubs, I suppose."

It was cheerful to know that so many citizens were abroad, to keep her company. Some optimists were still singing carols. She faintly heard the strains of "Good King Wenceslas." It was in a tranquil frame of mind that she unpacked her sandwiches and thermos.

"IT'S Christmas Day," she thought, as she drank hot coffee.

"And I'm spending it with Don and the pup."

At that moment her career grew misty, and the flame of her literary ambition dipped as the future glowed with the warm firelight of home. In sudden elation, she held up her flask and toasted the waxworks.

"Merry Christmas to you all! And many of them."

The faces of the illuminated figures remained stolid, but she could almost swear that a low murmur of acknowledgement seemed to swell from the rest of her company—invisible in the darkness.

She spun out her meal to its limit, stifling her craving for a cigarette. Then, growing bored, she counted the visible waxworks, and tried to memorise them.

"Twenty-one, twenty-two... Wolsey, Queen Elizabeth, Guy Fawkes. Napoleon ought to go on a diet. Ever heard of eighteen days, Nap? Poor old Julius Caesar looks as though he'd been sunbathing on the Lido. He's about due for the melting-pot."

In her eyes they were a second-rate set of dummies. The local theory that they could terrorise a human being to death or madness seemed a fantastic notion.

"No," concluded Sonia. "There's really more in Poke's bright idea."

Again she saw the sun-smitten office—for the big unshielded window faced south—with its blistered paint, faded wallpaper, ink-stained desks, typewriters, telephones, and a huge fire in the untidy grate. Young Wells smoked his big pipe, while the sub-editor—a ginger, pigheaded young man—laid down the law about the mystery deaths.

And then she heard Poke's toneless dead man's voice.

"You may be right about the spiritualist. He died of fright—but not of the waxworks. My belief is that he established contact with the spirit of his dead friend, the alderman, and to learned his real fate."

"What fate?" snapped the sub-editor.

"I believe that the alderman was murdered," replied Poke.

He clung to his point like a limpet in the face of all counter-arguments.

"The alderman had enemies," he said. "Nothing would be easier than for one of them to lie in wait for him. In the present circumstances, I could commit a murder in the Waxworks, and get away with it."

"How?" demanded young Wells.

"How? To begin with, the Gallery is a one-man show and the porter's a bonehead. Anyone could enter and leave the Gallery without his being wise to it."

"And the murder?" plugged young Wells.

With a shudder Sonia remembered how Poke had glanced at his long knotted fingers.

"If I could not achieve my object by fright, which is the foolproof way," he replied, "I should try a little artistic strangulation."

"And leave your marks?"

"Not necessarily. Every expert knows that there are methods which show no trace."

Sonia fumbled in her bag for the cigarettes which were not there.

"Why did I let myself think of that, just now?" she thought. "Really too stupid."

As she reproached herself for her morbidity, she broke off to stare at the door which led to the Hall of Horrors.

When she had last looked at it, she could have sworn that it was tightly closed.... But now it gaped open by an inch.

She looked at the black cavity, recognising the first test on her nerves. Later on, there would be others. She realised the fact that, within her cool, practical self, she carried an hysterical neurotic passenger, who would doubtless give her a lot of trouble through officious suggestions and uncomfortable reminders.

She resolved to give her second self a taste of her quality, and so quell her at the start.

"That door was merely closed," she remarked, as, with a firm step she crossed to the Hall of Horrors and shut the door.

"One o'clock. I begin to realise that there is more in this than I thought. Perhaps I'm missing my sleep. But I'm keyed up and horribly expectant. Of what? I don't know. But I seem to be waiting for—something. I find myself listening—listening. The place is full of mysterious noises. I know they're my fancy.... And things appear to move. I can distinguish footsteps and whispers, as though those waxworks which I cannot see in the darkness are beginning to stir to life."

Sonia dropped her pencil at the sound of a low chuckle. It seemed to come from the end of the Gallery, which was blacked out by shadows.

As her imagination galloped away with her she reproached herself sharply.

"Steady, don't be a fool. There must be a cloak-room here. That chuckle is the air escaping in a pipe—or something. I'm betrayed by my own ignorance of hydraulics."

In spite of her brave words she returned rather quickly to her corner.

WITH her back against the wall she felt less apprehensive. But

she recognised her cowardice as an ominous sign.

She was desperately afraid of someone—or something—creeping up behind her and touching her.

"I've struck the bad patch," she told herself. "It will be worse at three o'clock and work up to a climax. But when I make my entry, at three. I shall have reached the peak. After that every minute will be bringing the dawn nearer."

But of one fact she was ignorant. There would be no recorded impression at three o'clock.

Happily unconscious, she began to think of her copy. When she returned to the office—sunken-eyed, and looking like nothing on earth—she would then rejoice over every symptom of groundless fear.

"It's a story all right," she gloated, looking at Hamlet. His gnarled, pallid features and dark, smouldering eyes were strangely familiar to her.

Suddenly she realised that he reminded her of Hubert Poke.

Against her will, her thoughts again turned to him. She told herself that he was exactly like a waxwork. His yellow face—symptomatic of heart-trouble—had the same cheesy hue, and his eyes were like dull black glass. He wore a denture which was too large for him, and which forced his lips apart in a mirthless grin.

He always seemed to smile—even over the episode of the lift—which had been no joke.

It happened two days before. Sonia had rushed into the office in a state of molten excitement, because she had extracted an interview from a personage who had just received the Freedom of the City. This distinguished freeman had the reputation of shunning newspaper publicity, and Poke had tried his luck, only to be sent away with a flea in his ear.

At the back of her mind, Sonia knew that she had not fought level, for she was conscious of the effect of violet-blue eyes and a dimple upon a reserved but very human gentleman. But in her elation she had been rather blatant about her score.

She transcribed her notes, rattling away at her typewriter in a tremendous hurry, because she had a dinner engagement. In the same breathless speed she had rushed towards the automatic lift.

She was just about to step into it when young Wells had leaped the length of the passage and dragged her back.

"Look where you're going," he shouted.

Sonia looked—and saw only the well of the shaft. The lift was not waiting in its accustomed place.

"Out of order," explained Wells before he turned to blast Hubert Poke, who stood by.

"You almighty chump, why didn't you grab Miss Fraser, instead of standing by like a stuck pig?"

At the time Sonia had vaguely remarked how Poke had stammered and sweated, and she accepted the fact that he had been petrified by shock and had lost his head.

FOR the first time she realised that his inaction had been

deliberate. She remembered the flame of terrible excitement in

his eyes and his stretched ghastly grin.

"He hates me," she thought. "It's my fault. I've been tactless and cocksure."

Then a flood of horror swept over her.

"But he wanted to see me crash. It's almost murder."

As she began to tremble the jumpy passenger she carried reminded her of Poke's remark about the alderman.

"He had enemies."

Sonia shook away the suggestion angrily.

"My memory's uncanny," she thought. "I'm stimulated and all strung up. It must be the atmosphere.... Perhaps there's some gas in the air that accounts for these brain-storms. It's hopeless to be so utterly unscientific. Poke would have made a better job of this."

She was back again to Hubert Poke. He had become an obsession.

Her head began to throb and a tiny gong started to beat in her temples. This time she recognised the signs without any mental ferment.

"Atmospherics. A storm's coming up. It might make things rather thrilling. I must concentrate on my story. Really, my luck's in."

She sat for some time, forcing herself to think of pleasant subjects—of arguments with young Wells and the tennis tournament. But there was always a point when her thoughts gave a twist and led her back to Poke.

Presently she grew cramped and got up to pace the illuminated aisle in front of the window. She tried again to talk to the waxworks, but this time it was not a success.

They seemed to have grown remote and secretive, as though they were removed to another plane, where they possessed a hidden life.

Suddenly she gave a faint scream. Someone—or something—had crept up behind her, for she felt the touch of cold fingers upon her arm.

"Two o'clock. They're only wax. They shall not frighten me. But they're trying to. One by one they're coming to life.:.. Charles the Second no longer looks sour dough. He is beginning to leer at me. His eyes remind me of Hubert Poke."

Sonia stopped writing, to glance uneasily at the image of the Stuart monarch. His black velveteen suit appeared to have a richer pile. The swart curls which fell over his lace collar looked less like horsehair. There really seemed a gleam of amorous interest lurking at the back of his glass optics.

Absurdly, Sonia spoke to him in order to reassure herself.

"Did you touch me? At the first hint of a liberty, Charles Stuart, I'll smack your face. You'll learn a modern journalist has not the manners of an orange girl."

Instantly the satyr reverted to a dummy in a moth-eaten historical costume.

Sonia stood, listening for young Wells' footsteps. But she could not hear them, although the street now was perfectly still. She tried to picture him, propping up the opposite building, solid and immovable as the Rock of Gibraltar.

But it was no good. Doubts began to obtrude.

"I don't believe he's there. After all, why should he stay? He only pretended, just to give me confidence. He's gone."

She shrank back to her corner, drawing her tennis coat closer for warmth. It was growing colder, causing her to think of tempting things—of a hot water bottle and a steaming teapot.

PRESENTLY she realised that she was growing drowsy. Her lids

felt as though weighted with lead, so that it required an effort

to keep them open.

This was a complication which she had not foreseen. Although she longed to drop off to sleep, she sternly resisted the temptation.

"No. It's not fair. I've set myself the job of recording a night spent in the Waxworks. It must be the genuine thing."

She blinked more vigorously, staring across to where Byron drooped like a sooty flamingo.

"Mercy, how he yearns! He reminds me of—No, I won't think of him... I must keep awake... Bed... blankets, pillows... No."

Her head fell forward, and for a minute she dozed. In that space of time she had a vivid dream.

She thought that she was still in her corner in the Gallery, watching the dead alderman as he paced to and fro, before the window. She had never seen him, so he conformed to her own idea of an alderman—stout, pompous, and wearing the dark-blue, fur-trimmed robe of his office.

"He's got a face like a sleepy pear," she decided. "Nice old thing, but brainless."

And then, suddenly, her tolerant derision turned to acute apprehension on his account, as she saw that he was being followed. A shape was stalking him as a cat stalks a bird.

Sonia tried to warn him of his peril, but, after the fashion of nightmares, she found herself voiceless. Even as she struggled to scream, a grotesquely long arm shot out and monstrous fingers gripped the alderman's throat.

In the same moment she saw the face of the killer. It was Hubert Poke.

SHE awoke with a start, glad to find that it was but a dream.

As she looked around her with dazed eyes, she saw a faint flicker

of light. The mutter of very faint thunder, together with a

patter of rain, told her that the storm had broken.

It was still a long way off. for Oldhampton seemed to be having merely a reflection and an echo.

"It'll clear the air," thought Sonia.

Then her heart gave a violent leap. One of the waxworks had come to life. She distinctly saw it move, before it disappeared into the darkness at the end of the Gallery.

She kept her head, realising that it was time to give up.

"My nerve's crashed," she thought. That figure was only my fancy. I'm just like the others. Defeated by wax."

Instinctively, she paid the figures her homage. It was the cumulative effect of their grim company, with their simulated life and sinister associations, that had rushed her defences.

Although it was bitter to fail, she comforted herself with the reminder that she had enough copy for her article, she could even make capital out of her own capitulation to the force of suggestion.

With a slight grimace she picked up her notebook. There would be no more on-the-spot impressions. But young Wells, if he was still there, would be grateful for the end of his vigil, whatever the state of mind of the porter.

She groped in the darkness for her signal-lamp. But her fingers only scraped bare polished boards.

The torch had disappeared.

In a panic, she dropped down on her knees, and searched for yards around the spot where she was positive it had lain.

It was the instinct of self-preservation which caused her to give up her vain search.

"I'm in danger," she thought. "And I've no one to help me now. I must see this through myself."

She pushed back her hair from a brow which had grown damp.

"There's a brain working against mine. When I was asleep, someone —or something—stole my torch."

Something? The waxworks became instinct with terrible possibility as she stared at them. Some were merely blurred shapes—their faces opaque oblongs or ovals. But others—illuminated from the street—were beginning to reveal themselves in a new guise.

Queen Elizabeth, with peaked chin and fiery hair, seemed to regard her with intelligent malice. The countenance of Napoleon was heavy with brooding power, as though he were willing her to submit. Cardinal Wolsey held her with a glittering eye.

Sonia realised that she was letting herself be hypnotised by creatures of wax—so many pounds of candles moulded to human form.

"This is what happened to those others." she thought. "Nothing happened. But I'm afraid of them. I'm terribly afraid.... There's only one thing to do I must count them again."

She knew that she must find out whether her torch had been stolen through human agency; but she shrank from the experiment, not knowing which she feared more—a tangible enemy or the unknown.

AS she began to count, the chilly air inside the building

seemed to throb with each thud of her heart.

"Seventeen, eighteen." She was scarcely conscious of the numerals she murmured. "Twenty-two, twenty-three."

She stopped. Twenty-three? If her tally were correct, there was an extra waxwork in the Gallery.

On the shock or the discovery came a blinding flash of light, which veined the sky with fire. It seemed to run down the figure of Joan of Arc like a flaming torch. By a freak of atmospherics, the storm, which had been a starved, whimpering affair of flicker and murmur, culminated, and ended in what was apparently a thunder-bolt.

The explosion which followed was stunning; but Sonia scarcely noticed it in her terror.

THE unearthly violet glare had revealed to her a figure which

she had previously overlooked.

It was seated in a chair, its hand supporting its peaked chin, and its pallid, clean-shaven features nearly hidden by a familiar broad-brimmed felt hat, which—together with the black cape—gave her the clue to its identity.

It was Hubert Poke.

Three o'clock.

Sonia heard it strike, as her memory began to reproduce, with horrible fidelity, every word of Poke's conversation on murder.

"Artistic strangulation." She pictured the cruel agony of life leaking—bubble by bubble, gasp by gasp; it would be slow—for he had boasted of a method which left no tell-tale marks.

"Another death," she thought dully. "If it happens everyone will say that the Waxworks have killed me. What a story.... Only, I shall not write it up."

THE tramp of feet rang out on the pavement below. It might

have been the policeman on his beat; but Sonia wanted to feel

that young Wells was still faithful to his post.

She looked up at the window, set high in the wall, and, for a moment, was tempted to shout. But the idea was too desperate. If she failed to attract outside attention, she would seal her own fate, for Poke would be prompted to hasten her extinction.

"Awful to feel he's so near, and yet I cannot reach him," she thought. "It makes it so much worse."

She crouched there, starting and sweating at every faint sound in the darkness. The rain, which still pattered on the skylight, mimicked footsteps and whispers. She remembered her dream and the nightmare spring and clutch.

It was an omen. At any moment it would come....

Her fear jolted her brain. For the first time she had a glimmer of hope.

"I didn't see him before the flash, because he looked exactly like one of the waxworks. Could I hide among them, too?" she wondered.

She knew that her white coat alone revealed her position to him. Holding her breath, she wriggled out of it, and hung it on the effigy of Charles II. In her black coat, with her handkerchief-scarf tied over her face, burglar fashion, she hoped that she was invisible against the sable-draped walls.

Her knees shook as she crept from her shelter. When she had stolen a few yards, she stopped to listen.... In the darkness, someone was astir. She heard a soft padding of feet, moving with the certainty of one who sees his goal.

Her coat glimmered in her deserted corner.

In a sudden panic, she increased her pace, straining her ears for other sounds. She had reached the far end of the Gallery, where no gleam from the window penetrated the gloom. Blindfolded and muffled, she groped her way towards the alcoves which held the tableaux.

Suddenly she stopped, every nerve in her body quivering. She had heard a thud, like rubbered soles alighting after a spring.

"He knows now." Swift on the trail of her thought flashed another. "He will look for me. Oh, quick!"

She tried to move, but her muscles were bound, and she stood as though rooted to the spot, listening. It was impossible to locate the footsteps. They seemed to come from every quarter of the Gallery. Sometimes they sounded remote, but, whenever she drew a freer breath, a sudden creak of the boards close to where she stood made her heart leap.

At last she reached the limit of endurance. Unable to bear the suspense of waiting, she moved on.

Her pursuer followed her at a distance. He gained on her, but still withheld his spring. She had the feeling that he held her at the end of an invisible string.

"He's playing with me, like a cat with a mouse," she thought.

If he had seen her, he let her creep forward until the darkness was no longer absolute. There were gradations in its density so that she was able to recognise the first alcove. Straining her eyes, she could distinguish the outlines of the bed where the Virtuous Man made his triumphant exit from life, surrounded by a flock of his sorrowing family and their progeny.

Slipping inside the circle, she added one more mourner to the tableau.

THE minutes passed, but nothing happened. There seemed no

sound save the tiny gong beating inside her temples. Even the

raindrops had ceased to patter on the skylight.

Sonia began to find the silence more deadly than noise. It was like the lull before the storm. Question after question came rolling into her mind.

"Where is he? What will he do next? Why doesn't he strike a light?"

As though someone were listening-in to her thoughts, she suddenly heard a faint splutter as of an ignited match. Or it might have been the click of an exhausted electric torch.

With her back turned to the room, she could see no light. She heard the half-hour strike, with a faint wonder that she was still alive.

"What will have happened before the next quarter?" she asked.

Presently she began to feel the strain of her pose, which she held as rigidly as any artist's model. For the time— if her presence were not already detected—her life depended on her immobility.

As an overpowering weariness began to steal over her, a whisper stirred in her brain:

"The alderman was found dead on a bed."

The newspaper account had not specified which especial tableau had been the scene of the tragedy, but she could not remember another alcove which held a bed. As she stared at the white dimness of the quilt she seemed to see it blotched with a dark, sprawling form, writhing under the grip of long fingers.

To shut out the suggestion of her fancy, she closed her eyes. The cold, dead air in the alcove was sapping her exhausted vitality, so that once again she began to nod. She dozed as she stood, rocking to and fro on her feet.

Her surroundings grew shadowy. Sometimes she knew that she was in the alcove, but at others she strayed momentarily over strange borders.... She was back in the summer, walking in a garden with young Wells. Roses and sunshine....

She awoke with a start at the sound of heavy breathing. It sounded close to her—almost by her side. The figure of a mourner kneeling by the bed seemed to change its posture slightly.

Instantly maddened thoughts began to flock and flutter wildly inside her brain.

"Who was it? Was it Hubert Poke? Would history be repeated? Was she doomed also to be strangled inside the alcove? Had Fate led her there?"

She waited, but nothing happened. Again she had the sensation of being played with by a master-mind&mdash:dangled at the end of his invisible string.

Presently she was emboldened to steal from the alcove, to seek another shelter. But though she held on to the last flicker of her will, she had reached the limit of endurance. Worn out with the violence of her emotions and physically spent from the strain of long periods of standing, she staggered as she walked.

She blundered round the gallery, without any sense of direction, colliding blindly with the groups of wax-work figures. When she reached the window her knees shook under her and she sank to the ground—dropping immediately into a sleep of utter exhaustion.

SHE awoke with a start as the first grey gleam of dawn was

stealing into the Gallery. It fell on the row of waxworks,

imparting a sickly hue to their features, as though they were

creatures stricken with plague.

It seemed to Sonia that they were waiting for her to wake. Their peeked faces were intelligent and their eyes held interest, as though they were keeping some secret.

She pushed back her hair, her brain still thick with clouded memories. Disconnected thoughts began to stir, to slide about.... Then suddenly her mind cleared, and she sprang up—staring at a figure wearing a familiar black cape.

Hubert Poke was also waiting for her to wake.

He sat in the same chair, and in the same posture, as when she had first seen him, in the flash of lightning. He looked as though he had never moved from his place—as though he could not move. His face had not the appearance of flesh.

As Sonia stared at him, with the feeling of a bird hypnotised by a snake, a doubt began to gather in her mind. Growing bolder, she crept closer to the figure.

It was a waxwork—libellous representation of the actor—Kean.

Her laugh rang joyously through the Gallery as she realised that she had passed a night of baseless terrors, cheated by the power of imagination. In her relief she turned impulsively to the waxworks.

"My congratulations," she said. "You are my masters."

They did not seem entirely satisfied by her homage, for they continued to watch her with an expression half benevolent and half sinister.

"Wait!" they seemed to say.

Sonia turned from them and opened her bag to get out her mirror and comb. There, among a jumble of notes, letters, lipsticks and powder compresses, she saw the electric torch.

"Of course!" she cried. "I remember now, I put it there. I was too windy to think properly.... Well, I have my story. I'd better get my coat."

The Gallery seemed smaller in the returning light. As she approached Charles Stuart, who looked like an umpire in his white coat, she glanced down the far end of the room, where she had groped in its shadows before the pursuit of imaginary footsteps.

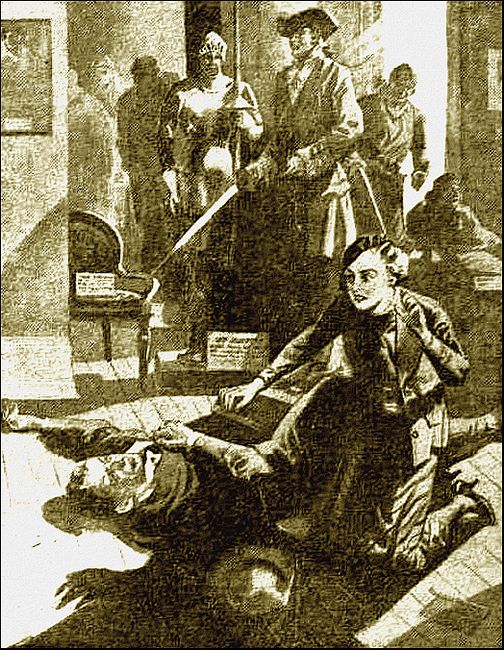

A waxwork was lying prone on the floor. For the second time she stood and gazed down upon a familiar black cape—a broad-brimmed conspirator's hat. Then she nerved herself to turn the figure so that its face was visible.

She gave a scream. There was no mistaking the glazed eyes and ghastly grin. She was looking down on the face of a dead man.

It was Hubert Poke.

She gave a scream. There was no mistaking the glazed eyes and

ghastly grin. She was looking down on the face of a dead man.

THE shock was too much for Sonia. She heard a singing in her

ears, while a black mist gathered before her eyes. For the first

time, in her life she fainted.

When she recovered consciousness she forced herself to kneel beside the body and cover it with its black cape. The pallid face resembled a death-mask, which revealed only too plainly the lines of egotism and cruelty in which it had been moulded by a gross spirit.

Yet Sonia felt no repulsion—only pity. It was Christmas morning, and he was dead, while her own portion was life triumphant. Closing her eyes, she whispered a prayer of supplication for his warped soul.

Presently, as she grew calmer, her mind began to work on the problem of his presence. His motive seemed obvious. Not knowing that she had changed her plan, he had concealed himself in the Gallery, in order to poach her story.

"He was in the Hall of Horrors at first," she thought, remembering the opened door. "When he came out he hid at this end. We never saw each other, because of the waxworks between us; but we heard each other."

She realised that the sounds which had terrified her had not all been due to imagination, while it was her agency which had converted the room into a whispering gallery of strange murmurs and voices. The clue to the cause of death was revealed by his wrist-watch, which had smashed when he fell. Its hands had stopped at three minutes to three, proving that the flash and explosion of the thunderbolt had been too much for his diseased heart— already overstrained by superstitious fears.

SONIA shuddered at a mental vision of his face, distraught with terror and pulped by raw primal impulses, after a night spent in a madman's world of phantasy.

She turned to look at the waxworks. At last she understood what they seemed to say:

"But for us, you would have met—at dawn."

"Your share shall be acknowledged, I promise you," she said, as she opened her notebook.

"Eight o'clock. The Christmas bells are ringing and it is wonderful just to be alive. I'm through the night, and none the worse for the experience, although I cracked badly after three o'clock. A colleague who, unknown to me, was also concealed in the Gallery has met with a tragic fate, caused, I am sure, by the force of suggestion. Although his death is due to heart-failure, the superstitious will certainly claim it is another victory for the Waxworks."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.