First Printed 1956

How came I to be ? Whence am I ? To serve what

purpose did I come ? To go again ! How can I

learn aught—naught knowing ?

PREFACE

We cannot doubt that we men have our roots in the natural order, but we can and do wonder if our fruits belong to the same world. The question whether there is some affinity between the total man and the total universe, or whether we are but accidental intruders upon the cosmic scene, is one that must concern every man—for upon the answer hangs the decision as to the values that should rule our lives. A total question demands a total answer, and this could not be given except in terms of the whole of human experience—including all that man has learned in recent centuries about himself and the universe. Such an undertaking is manifestly impossible of accomplishment unless all experience can be brought into a coherent system capable of apprehension by that limited and capricious instrument, the human mind. The Systema Universi has proved a will-o'-the-wisp, leading many a powerful intellect into a morass of vain speculation. Since the failure of Hegel's Cosmosophy, Comte's Panhylism, Fechner's Panentheism, and Bergson's Panpsychism —to name but four noteworthy essays at an all-embracing scheme— philosophers have turned away from the question of questions to follow the prevalent cult of specialization in the hope that to be precise about little things may prove safer than to be vague about everything.

Meanwhile the frontiers of human knowledge have been thrust back in all directions—history, prehistory, and palaeontology; ethnology and comparative religion; psychology and physiology; biochemistry, embryology, and genetics; physics, astronomy, and mathematics— each has brought its quota of well-ascertained facts that collectively have created a situation that has perhaps never before existed in the long history of human cultures. We need no longer speculate about many things that our forerunners assigned to metaphysics or theology; nor is it permissible to do so. Science has killed the old speculative philosophy, but has put nothing in its place. There is now before us the material for a new synthesis; but it is so immense in its extent and so bewildering in its variety that no one human mind can compass one hundredth part of it. No modern Pico della Mirandola could challenge the learned world to discourse on every known subject. No modern Descartcs would venture to assert that he had mastered all the sciences.

And yet a synthesis is necessary; for unless all knowledge can be brought into a coherent system, we shall have either to abandon the hope of finding man's place in the universe or else to accept with pious

resignation, dogmas that disregard the lessons of natural science, and acquiesce in the continuing divorce of fact and value that has been the chief cause of our present bewilderment.

More than thirty-five years have passed since, in the spring of 1920, I became convinced that many intractable problems would be resolved if we could overcome the handicap of thinking in terms of events in space and time only, and could widen our horizons to include the unseen and unexplored dimension of eternity. I set myself to study the dilemmas of science and philosophy—such as the ether paradox or the antinomy of free-will and universal law—to see if the material for knowing eternity might not be lying unnoticed before our eyes.

Soon afterwards I met Gurdjieff, who made me see that to know more is not enough, and that it is necessary to be more if we would penetrate beyond the veil of space and time. In the succeeding years, I learned from him the elements of a comprehensive cosmology that gave promise of reconciling fact and value and of laying the foundations of a new Weltanschauung. Gurdjieff's cosmology, though magnificent in its bold outline, was nevertheless far from adequate in its treatment of the data of modern science. For many years I wrestled with the problem of reconciling the two. Finally, in 1940, I decided to make a fresh start, and the present book began to be written. Little by little I saw the fragments fall into place, and realized that the systematization of all human experience was more than a remote possibility. The task was quite beyond my own powers, and could not even have been attempted without the co-operation of specialists who helped me with what I regarded as the crucial problem—the demonstration that the mathematical and physical sciences required an ampler framework of dimensions than those of space and time, even as generalized by the work of Minkowski and Einstein.

The undertaking continued to expand, and it became clear that the two great problems of systematizing all fact and reconciling all values could be accomplished if only we could put aside for ever the narrow terrestrialism that is so strange a relic of the Middle Ages and still dominates all discussion of human destiny.

The present volume deals only with the systematization of facts; but it was written in parallel with the second volume, which I hope to prepare for publication within one or two years. Only when read together can the relevance of the work for the question of man's place in the universe become apparent. In the meantime, I wish to make it clear that this book is not a presentation of Gurdjieff's cosmology. It is my own essay, and much that it contains is derived from sources quite uncon-

nected with Gurdjieff's teaching. It aims at a presentation accessible, not only to professional philosophers, but to every reader who is prepared to undertake the not inconsiderable task of mastering the basic conception and gaining familiarity with the special terminology necessary in avoid misleading associations. Nevertheless, it could not have been written without the stimulation of Gurdjieff's inspired insight into the cosmic scheme, nor without the grounding in his methods which I have been fortunate to receive from him personally, and from his great pupil and exponent, P. D. Ouspensky.

Not long before Gurdjieff's death in October 1949, I spoke to him about this work and told him of the line I was taking. He showed by his comments that he fully grasped its implications, but disclaimed any personal interest, saying, "It is your work and not mine—all the same, it will be good publicity for Beelzebub", referring to his own book, All and Everything, published posthumously in 1950. I accept this assessment. In Gurdjieff's All and Everything there are insights far deeper than I myself could attain, and the reader who feels the need to find, not merely a new world-outlook, but a new way of life, is counselled to take Gurdjieff's work and study it as I have done, After perhaps thirty careful readings, I still discover in it new depths of meaning and—I am glad to say—new evidence that the main conceptions of my own work are in accord with the direct intuitions of a genius that I do not hesitate to describe as superhuman.

Among the many 'crumbs from the ideas-table' of Gurdjieff that have nourished my thinking, I count as of first importance the doctrine of Reciprocal Maintenance according to which every recognizable entity on every scale of existence participates in the universal exchange of energies—supporting and being supported by the existence of others. Reciprocal Maintenance is the corner stone of Gurdjieff's teaching in so far as it illuminates both fact and value, yet it is but one of his many daring and original conceptions. He left behind him no orderly system of thought, nor did he appear to be interested in systematic exposition

leaving it to his followers to reap the harvest of the ideas which he had sown.

Several books have appeared treating of one or other aspect of Gurd-jieff's teaching and methods, and still more have been inspired by his ideas without mentioning their source. I do not wish to claim Gurdjieff's authority for anything I have written, nor even for the interpretation I have placed upon his own written word; but I do wish to acknowledge the inspiration of his teaching and, perhaps even more, the influence of his individuality upon my life.

The form of the book itself is an integral part of the exposition, for I hold that systematization of material demands systematization of presentation. The division into two parts corresponds to the dualism of rationalism and empiricism which the book seeks to reconcile in the correlative triads of Function, Being, and Will and Hyponomic, Autonomic, and Hypernomic modes of existence. Proceeding in this way, the rational and the empirical are forced at every stage to come to terms. Such a method would scarcely have been practicable even fifty years ago; for our empirical knowledge was then still by no means comprehensive enough to fill the vessel of rational speculation. Now the tables have been turned, and speculation—even the most audacious—is overwhelmed by the avalanche of empirical discovery.

Of necessity this work is uneven—in few of the subjects treated can I claim the assurance of a specialist—but I have set myself as far as possible to hold the balance between all the branches of science without regard to my own particular studies. Such a book must inevitably teem with errors, omissions, faulty selection of evidence, and inaccurate summarizing. It has not been my aim to produce a compendium of the sciences or a systema naturae in the seventeenth-century style. I have essayed the far more hazardous task of showing that experience itself when patiently interrogated will teach us its own lesson and answer the question whether or not man in his totality and the universe in its totality are manifestations of the same laws and made upon the same pattern.

I greatly wished to write in a language that would readily be followed by any serious reader. Unfortunately the subject-matter is so vast that the use of special signs to designate recurrent complex notions was unavoidable. For most purposes verbal signs have sufficed, but in Chapters 13-16 the use of mathematical symbolism could have been avoided only at the price of a greatly lengthened exposition. There is, however, little mathematics in the book—many hundreds of pages of mathematical analysis have been omitted or condensed into the three appendices—nor have I often attempted to marshal and present even a selection of the evidence in support of some of the assertions made. In consequence of these limitations of a practical nature, many passages have the appearance of unfounded speculation or, what is even worse, of a biased selection of illustrative material. I can only hope that those who realize that we must, at all costs, discover a means of looking at all that natural science has discovered in the last centuries as one coherent whole will be prepared to give the method a trial; and, if they are specialists in one or other of the subjects treated, will rather fill in the gaps and correct the errors than condemn the enterprise.

I have acknowledged my primary and overriding indebtedness to Gurdjieff. I wish also to express my grateful appreciation to those who have helped me in the task. The first is Mr. (now Professor) M. W. Thring, who devoted hundreds of hours to the search for a means of interpreting my conceptions of time and eternity in mathematical terms. Without his brilliant labours the central chapters of this book could not have been written. After him, the task was taken up by Mr. R. L. Brown, with whom I worked out the six-dimensional geometry o± Chapter 15 and clarified for myself the all-important distinction—never hitherto made—between the three inner dimensions of time, eternity, and hyparxis. The latter term has been introduced to designate that time-like determining-condition by which coupling, interaction, and the arising of consciousness are made possible. In Chapter 4 on language,

I have been much helped by the advice and criticism of Mr. Henry Boys,

and in the biological chapters by Dr. Isobel Turnadge. Dr. Maurice Vernet has helped me both by his books and by many fruitful discussions and I have been greatly encouraged to find that we reached similar conclusions regarding the nature and role of life from quite different

starting-points. Mr. Anthony Pirie has read the whole work in proof.

My pupils at the Institute for the Comparative Study of History, Philosophy, and the Sciences have provided me with a touchstone by their reactions to the many readings of the manuscript in study groups and summer courses.

In the course of fifteen years since I started writing this book, it has been revised and completely rewritten at least a dozen times. The arduous task of interpreting my spoken and written word fell for the first nine years upon Miss Cathleen Murphy, and for the last five upon Mrs. Joan Cox. Mrs. E. Sawrey-Cookson has laboured for two years to improve the presentation. To these three ladies, and to many others who have helped me, I owe a debt hard to repay. My publishers and, in particular, Mr. Paul Hodder-Williams have stimulated and encouraged me in this undertaking; it is nearly ten years since we agreed that the hook should be published. As year has succeeded year and the work has remained unfinished, their patient confidence that the task should and would be accomplished has never faltered. I am indeed grateful to them.

Notwithstanding all the help I have received, I am well aware how far the book falls short of the standards of a Hartmann or a Lotze. The only justification for its publication is the conviction that the task of system-atizing all human knowledge can no longer be delayed and the realization that those better qualified as specialists—including professional philosophers—would fear to tread so hazardous a path.

The tasks remaining to be accomplished are twofold. We must first search for a coherent and adequate system of values that will help us to understand why we men exist and how we must live to justify our existence. The modern world obstinately—and rightly—declines to wear the old garments of systems and theologies that are neither sound in their cosmology nor true to experience. Henceforth we shall neither accept what we feel but do not understand nor yet act upon any 'categorical imperative' that fails to evoke the assent of our feelings. The human species—that must be regarded as an individualized being —is passing from childhood to adolescence. We can no longer be content with the naive beliefs and speculations that gave shape to our behaviour in the days of infancy.

As experience accumulates it must, more and more, take its place as the main source of judgments—but values discovered in subjective experience can be satisfying only if confirmed by convincing evidence that they are both valid and significant upon the cosmic scale also.

We should, above all, mistrust any value system that is applicable only to human life on the earth or to some fanciful picture of similar life in other worlds, here or 'beyond'. In the present volume I have emphasized the homogeneity of fact on all scales and all levels. What may be called the 'cosmic intuition' compels us to demand a similar universal homogeneity in any acceptable system of values. This requires, inter alia, a comprehensive reconciliation of value and fact that can be found only in some third principle capable of harmonizing all possible experience and of giving meaning to all possible existence. The endeavour to express the nature of this universal reconciling principle is the second task to be undertaken.

It so happens—and this may well be evidence that our destiny is guided, or at least influenced by, some Higher Power—that, at this critical phase, our knowledge of the universe, including that of human nature and human history, has grown immensely. There is every reason to expect that the advance will continue and will confer upon mankind a greater power of action than in any period of the past. The destructive and self-destructive activities of the human race have gained a terrifying momentum. Although there are signs of counteraction, mankind is still far from having grasped the extent to which values will have to be re-valued if we are to survive. Fortunately there are grounds for hoping that the growth of knowledge is preparing the way for a better grasp of the true significance of life on the earth and of the universal order. As we become increasingly aware of the laws that govern the universal transformations of energy we shall change our

attitude towards our value systems also. An important element in this revaluation must be the abandonment of humanistic aesthetics and earth-bound theologies. All that exists, great and small, is concerned in the search for values, and we men must accept the fact that our little schoolroom, the earth, is not the centre of the universe.

We cannot, however, be satisfied with the mere negation of geo-centrfcity. If our values are to be both universal and positive, we must find some key to understanding the 'why' as well as the 'what' of the cosmic process. The postulate of the homogeneity of fact and value will prove to be an instrument of unlimited power and when applied to the elucidation of the Doctrine of Reciprocal Maintenance it can give us a working answer to all the fundamental questions of our existence. I cannot hope to do more than give expression to the little I have learned from others and understood myself of the cosmic scheme.

J. G. Bennett. Coombe Springs, June 1956.

|

CONTENTS |

||

|

Preface |

vii |

|

|

Introduction |

3 |

|

|

FIRST BOOK: THE FOUNDATIONS |

||

|

PART ONE: METAPHYSICS |

||

|

Chapter |

1. Points of Departure |

17 |

|

i.i.i. |

First and Last Questions |

17 |

|

The rational quest for final principles of explanation having failed, we must turn to an uncompromising relativism. Our principles must be empirical and susceptible of elaboration and refinement. |

||

|

I.I.2. |

The Drama of Uncertainty |

19 |

|

Uncertainty and hazard are undoubtedly elements of all our human experience—we should therefore test the assumption that all existence is subject to hazard—this would mean that the universe is dramatic. |

||

|

I.1.3. |

The Limitations of Human Perceptions |

21 |

|

We must accept and allow for the limitations of the sense perceptions and intellectual powers of man—the short duration of human existence and the defectiveness of records result in the loss of the greater part of experience acquired in each age. |

||

|

I.1.4. |

Forms of Thought |

23 |

|

Thinking of three kinds, (a) associative, (b) logical, which includes the dialectic, and (c) supra-logical—notwithstanding its extreme rarity, supra-logical thinking responsible for all significant advances in science and art. |

||

|

I.1.5. |

The Significance of Number |

26 |

|

The importance of multi-term systems in all experience gives number a significance beyond arithmetic—numbers qualitative as well as quantitative. |

||

|

I. 1. 6. Concrete Forms and Magic The concrete significance of number directly given in experience—the ancient belief that understanding of numbers confers magical powers now discredited—belief in magic still prevails in disguised forms no less naive than the former—the true significance of concrete forms. |

28 |

|

I.1.7. The Gradual Approach We shall follow method of progressive approximation— neither deductive nor inductive—reconciles empiricism and rationalism. |

29 |

|

Chapter 2. The Progression of the Categories |

31 |

|

I.2.1. Categories and Principles The distinction between concrete and abstract statements —abstraction unavoidable but aim is to achieve utmost concreteness possible—categories are concrete forms recognized in experience—primary statements about categories are principles—nature of our categories explained— distinguished from those of Aristotle, Kant, Whitehead. |

31 |

|

I.2.2. The Numerical Series of Categories Categories form an orderly progression—each associated with a number prescribing number of terms required for its realization—the first twelve categories stated—distinguished from Hegel's progression of the notion. |

33 |

|

I.2.3. Wholeness |

35 |

|

Wholeness omnipresent but relative—gradations of wholeness imply different degrees of togetherness—wholeness the property of being oneself. |

|

|

I.2.4. Polarity Polarity the dyad of connection and disjunction—every pair a dyad but most dyads trivial—polarity gives rise to force. |

37 |

|

I.2.5. Relatedness |

38 |

|

All relationships reducible to combination of three independent terms—affirming, denying, and reconciling elements— complex multi-term relationships always reducible to triads of the three elements. |

|

I.2.6. |

Subsistence |

40 |

|

Subsistence as primitive identity—arises by the limitation of |

||

|

existence within a framework—requires four terms. |

||

|

I.2.7. |

Potentiality |

41 |

|

Potentiality as complex identity—arises by super-imposition |

||

|

of triads—requires not less than five terms—potentiality |

||

|

associated with sensitiveness and hence life. |

||

|

I.2.8. |

Repetition |

42 |

|

Repetition as combination of difference, identity, and |

||

|

relatedness—requires minimum of six terms—repetition is |

||

|

rhythmicity—also the condition of knowledge. |

||

|

I.2.9. |

Structure |

43 |

|

Structure as organized wholeness—permits self-regulation |

||

|

—requires seven terms—the search for universal form of all |

||

|

forms—illustrated by growth of acorn to oak tree. |

||

|

I.2.10. |

Individuality |

45 |

|

The property of being a free agent—selves—power of |

||

|

choice—initiative residing in organized structures—re- |

||

|

quires eight terms. |

||

|

I.2.II. |

Pattern |

46 |

|

Passive pattern a result of orderly process—active pattern as |

||

|

source of order—pattern universal—requires nine terms. |

||

|

I.2.12. |

Creativity |

47 |

|

Power to evoke patterns—creativity polar in character— |

||

|

ten terms required. |

||

|

I.2.I3. |

Domination |

47 |

|

Power to reconcile order and disorder—domination does not |

||

|

participate—relatedness of universal forms—domination, |

||

|

need, and necessity—prior to creativity—requires eleven |

||

|

terms. |

||

|

I.2.14. |

Autocracy |

48 |

|

Underived power—autocracy as 'law unto itself'—last |

||

|

category of the natural order—but precursor only of cate- |

||

|

gories of value—source of methodological rule of universal |

||

|

similarity. |

|

Chapter |

3. The Elements of Experience |

49 |

||

|

I. |

3 |

. I. |

Hyle |

49 |

|

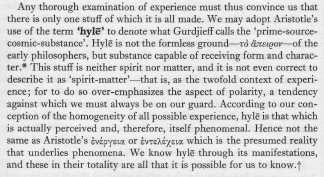

Experience as the given totality—'reality' to be left undefined—experience necessarily incomplete and inconsistent —specialization though permissible in natural science must be renounced in philosophy—prevalence of dualistic theories due to limitation of human thought—understanding possible only if all experience made of one stuff—the term hyle introduced to designate material sub-stratum of existence. |

||||

|

I |

•3 |

.2. |

The Triad of Experience |

54 |

|

Experience not monomorphous—function, being, and will elements differing in essential nature—all three are primary —Ouspensky's analogy of being and function. |

||||

|

I. |

3. |

3. |

Process and Function |

56 |

|

Process the knowable aspect of experience—knowledge confined to function—functions are the behaviour of wholes—functions the actualization of reality—every description necessarily functional. |

||||

|

I. |

3. |

4. |

Being as Togetherness |

58 |

|

Being the unknowable element of experience—determined states of experience—not actualized—Hegel and Schopenhauer. |

||||

|

I. |

3. |

5. |

Will as the Active Element |

60 |

|

Questions 'how' and 'why' answerable only in terms of will —will determines values but laws also implied—will not known but experienced through understanding—Schopenhauer, Hartmann, and Wittgenstein—cosmic significance of will to be studied through laws. |

||||

|

I. |

3. |

6. |

The Aspects of the Triad of Experience |

62 |

|

Function, being, will: primary triad of experience in three aspects—cosmic, subjective, objective—the universal process—(a) the cosmic aspect of function—knowledge the subjective aspect, behaviour the objective—(b) consciousness the subjective aspect of being—materiality objective— being itself cosmic—hence consciousness universal but not in sense of panpsychism—(c) authorizmos the cosmic aspect of will—objective aspect as law, subjective aspect as understanding—tertiary and further derived combinations of primary triad give rise to the diversity of experience. |

||||

|

I.3.7 |

The Primary and Secondary Forms of the Triad |

67 |

|

Each aspect is a triad—comparison with Spinoza's Ethics— |

||

|

the diversity of content of experience. |

||

|

PART TWO: EPISTEMOLOGY |

||

|

Chapter |

4. Language |

71 |

|

2.4.1. |

Communication |

71 |

|

The isolation of centres of consciousness normal for man |

||

|

but not necessarily universal—communication a characteris- |

||

|

tically human problem—dependent upon function—grada- |

||

|

tions of language—sign—symbol—gesture—linguistic ele- |

||

|

ment. |

||

|

2.4.2. |

Meaning |

73 |

|

Language: the communication of meanings—meaning: the |

||

|

recognition of a recurrent element in experience derived |

||

|

from the categories—content and . context—stability of |

||

|

context a condition of communication—conceptual signs and |

||

|

expressive signs—seven qualities of language—Ogden and |

||

|

Richards. |

||

|

2.4.3. |

Fictitious and Authentic Languages |

76 |

|

Defects of language—universal meanings—language de- |

||

|

pends upon reference—authentic language of four kinds— |

||

|

mixed language—sign language of philosophy—symbolical |

||

|

language referring to being—gestural language communica- |

||

|

tions of will. |

||

|

2.4.4. |

Spurious Language |

78 |

|

Defects of spurious language examined—remedied by in- |

||

|

flections and gestures—dependent upon personal relation- |

||

|

ship. |

||

|

2.4.5. |

Authentic but Mixed Language |

79 |

|

Mixed language serviceable but limited in scope—authentic |

||

|

language independent of subject-matter—requires stable |

||

|

context—methods of technical reference and logical abstrac- |

||

|

tion. |

||

|

2.4.6. |

Sign Language |

81 |

|

Language of philosophical signs requires context of shared |

||

|

experience—meaning of signs—categories as basic linguistic |

||

|

elements—clarification of signs requires reflective attention |

||

|

—philosophical signs form groups as numerous as there are |

||

|

distinct stable contexts—each discipline furnishes its own |

||

|

context—'one sign—one meaning'. |

|

2.4.7. |

Symbolical Language Signs inadequate to express relativity of wholeness—being-language requires symbolism—intuitions of meanings without abstraction—intuitions raw material for constructing being-language—signs instruments of knowledge, whereas symbols evoke states of consciousness liberated from function—symbols synthetic. |

85 |

|

2.4.8. |

Gesture Language Gesture language an act of will—concerted action no evidence of common understanding—distinction of linguistic elements—uniqueness of gestures—merging of language, art, and magic—historical gestures. |

89 |

|

Chapter |

5. Knowledge |

93 |

|

2.5.1. |

The Meaning of Knowledge Knowledge as link of sameness and difference—subjectivity of knowledge debars it from verifying its own content —errors of objectivism—of subjectivism—'knowing how'— operationalist theory of knowledge—pseudo-knowledge and information—knowledge must include both 'knowing what' and 'knowing how'. |

93 |

|

2.5.2. |

Knowledge as Order in Function Correspondence—Descartes, Hegel, Dewey, Russell— non-human knowledge—animals and machines—acquisition of knowledge and ordering process—knowledge as order in function—relationship of one to many. |

96 |

|

2.5.3. |

Non-discriminative Knowledge Gradations of knowledge—examples of non-discriminative knowledge resembling instinct—Lloyd Morgan and Norbert Wiener—cybernetics—knowledge present in inorganic wholes such as crystals. |

98 |

|

2.5.4. |

Polar or Discriminative Knowledge Selective, as distinct from passive, adaptation—animal knowledge polar—the comic and the tragic—polar knowledge lacking in objective reference. |

I0I |

|

2.5.5. |

Relational Knowledge Relational knowledge the precursor of understanding— overcomes barrier between subjective and objective experience—communicable—suspense of judgment—resolution of contradictories. |

103 |

|

2.5.6. |

Subjective and Objective Knowledge |

104 |

|

Reaction, discrimination, and relationship as three forms of subjective knowledge—need for a systematic epistem-ology—forty-nine distinct forms of knowledge—the gradations of objective knowledge. |

||

|

2.5.7. |

Subsistential or Value Knowledge |

106 |

|

Concrete knowledge as opposed to abstract—recognition of existence implies self-consciousness—as pre-requisite of value knowledge. |

||

|

2.5.8. |

Potential or Effectual Knowledge |

107 |

|

Knowledge of potentialities inaccessible to sense-experience alone—without this knowledge effectual action impossible —nevertheless effectual knowledge rare among individuals but recognizable in biological species. |

||

|

2.5.9. |

Cyclic or Transcendental Knowledge |

109 |

|

Knowledge of cycles not given in ordinary experience—in that sense transcendental—requires direct participation— derives from common pattern. |

||

|

2.5.I0. |

Structural or True Knowledge |

109 |

|

Objective knowledge of structure directly self-verifying— true knowledge neither absolute nor final but complete in itself—Gurdjieff's aphorism of knowledge. |

||

|

2.5.II. |

Revealed Knowledge |

III |

|

Revealed knowledge not confined to religious experience— accessible only to conscious individuality—occurs in scientific discovery. |

||

|

PART THREE: METHODOLOGY |

||

|

Chapter |

6. The Methods of Natural Philosophy |

115 |

|

3.6.I. |

The Method of Progressive Approximation |

115 |

|

Theories and laws of nature—science and technology— the method of specialization—scientific cosmology—specialization useless for cosmology—the method of progressive approximation not heuristic—the elucidation of meanings. |

|

3. |

6 |

.2. |

The Discrimination of Meaning |

117 |

|

Fact the experience of functional order—atomic facts— facts need not be actual—nor given directly in sense experience—nevertheless facts all of one kind—facts relative to a past experience—facts without value content—values cannot be known—meaning of 'ought'—fact and value inseparable in experience but can be isolated for purpose of study—facts have no meaning—meaning different from either fact or value—meaning a property of the will. |

||||

|

3 |

.6 |

.3 |

Phenomena as Primary Data |

122 |

|

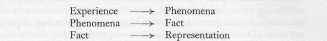

Phenomenon is experience from perspective of function— fact results from reducing phenomena to knowledge—content of knowledge less than content of phenomena—phenomena refer to normal experience of man. |

||||

|

3.6.4. |

The Place of Values in Natural Philosophy |

124 |

||

|

Natural science deals with facts—seeks to eliminate distinctions of consciousness—the method of statistical reduction— value judgments unavoidable but must be recognized and allowed for. |

||||

|

3 |

.6 |

.5. |

The Homogeneity of Fact as a Basic Postulate |

126 |

|

Postulate of the homogeneity of fact—science constantly improving means of reducing phenomena to fact—the role of the hypothesis—the provisional nature of scientific generalizations. |

||||

|

3 |

.6 |

.6. |

The Postulate of Universal Similarity |

128 |

|

All knowledge implies correspondence—without universal similarity there could be no transition from atomic to total facts—observation and the observer—intuition of universal similarity the mark of scientific genius. |

||||

|

3 |

.6 |

.7. |

The Postulate of the Stratification of Existence |

131 |

|

Levels of existence—the universal scale of being—the interrelations of strata—mutual statistical inaccessibility—levels of organization. |

||||

|

3 |

.6. |

8. |

The Postulate of Complementarity |

132 |

|

The dynamic and static aspects of experience—odd and even categories—concentration and expansion—the variety of processes—Fantappie's entropic and syntropic trends— the visible and invisible—cyclicity—concentration and expansion reconciled by cyclicity. |

|

3 |

.6 |

.9. |

The Postulate of the Universal Validity of Framework |

||

|

Laws |

135 |

||||

|

The search for universal laws—applicable only to the dis- |

|||||

|

tinction of possible and impossible situations—framework as |

|||||

|

the form of phenomena—determining-conditions—etern- |

|||||

|

ity, time, hyparxis, and space—framework illustrated by |

|||||

|

game of chess—mechanism, framework, and stratification. |

|||||

|

Chapter |

7. Possibility and Impossibility |

140 |

|||

|

3 |

.7 |

.I. |

The Meaning of 'Impossibility' |

140 |

|

|

Logical and physical impossibility—impossibility and im- |

|||||

|

probability—distinction of possible and potential. |

|||||

|

3 |

.7 |

.2. |

Situations, Occasions, and Actualizations |

142 |

|

|

Situation as abstract fact—occasion as possible situation— |

|||||

|

actualization as phenomenally fixed occasion—regularities |

|||||

|

of function distinguished from conditions of occurrence— |

|||||

|

cow eating grass—existence of round square—the determin- |

|||||

|

ing conditions discovered in the transition from phenomena |

|||||

|

to fact—nature as the totality of phenomena—framework as |

|||||

|

the laws of nature—logical consistency inapplicable to fact |

|||||

|

—distinction between rules and laws. |

|||||

|

3 |

.7 |

.3. |

The Search for Universal Laws |

145 |

|

|

Statements about impossibility imply universal laws— |

|||||

|

classification of phenomena—Kant, Husserl—successive- |

|||||

|

ness as an example of framework. |

|||||

|

3. |

7. |

.4. |

Universal Laws Governing Possibility |

147 |

|

|

Formulation of laws of framework first task of natural phil- |

|||||

|

osophy—their status—example from probability theory. |

|||||

|

3. |

7. |

5. |

Framework as the Condition of Possibility |

149 |

|

|

Framework—the totality of universal conditions that deter- |

|||||

|

mine whether a situation is possible or impossible—the |

|||||

|

framework laws relative to the form of consciousness— |

|||||

|

derive from will. |

|||||

|

3. |

7. |

6. |

The Four Determining-conditions of Framework |

150 |

|

|

The four determining-conditions—referred to existence and |

|||||

|

behaviour—hyparxis and the laws of will—classification |

|||||

|

and logic—the distinctness of framework laws complete only |

|||||

|

at the level of unconscious materiality—conditions neither |

|||||

|

known nor experienced—framework as non-arbitrariness of |

|||||

|

the phenomenal universe—framework rules—inner and |

|||||

|

outer determining-conditions. |

|||||

|

Chapter |

8. The Laws of Framework |

153 |

|

|

3.8.I. |

Framework as the Self-limitation of the Will |

153 |

|

|

The determining-conditions to be found only in the study of phenomena relative to a given state of consciousness. |

|||

|

3.8.2. |

Time as the Condition of Actualization |

153 |

|

|

Actualization as fixation by selection—actualization successive, conservative, and irreversible—characteristics of time. |

|||

|

3.8.3. |

Eternity as the Condition of Potentiality |

156 |

|

|

Potential existence and actual existence interconvertible— eternity as the storehouse of potentialities—illustrated by existence of a tree—eternity multivalent, synchronous, reversible, and imperishable—the reversal of the laws of thermodynamics—definition of virtue as negative entropy —definition of apokrisis as interval in eternity—illustrated by analogy of sheets of paper—three types of consciousness— characteristics of eternity. |

|||

|

3.8.4. |

Space as the Condition of Presence |

164 |

|

|

Definition of presence—Plato, Poincare, Whitehead, Alexander, Wittgenstein—extension and position derived from presence—proper-presence—interval—configuration—surface—point. |

|||

|

3.8.5. |

Hyparxis as the Condition of Recurrence |

166 |

|

|

Hyparxis as reconciling condition—hyparxis and will— hyparxis and meaning—hyparxis and recurrence—the natural numbers—cyclicity of hyparxis—ableness-to-be— the hyparchic interval. |

|||

|

3.8.6. |

The Universal Laws of Phenomena |

I7O |

|

|

Classification of framework laws—statistics—conservation— irreversibility — co-existence — classification — correspondence—the universal applicability of framework laws. |

|||

|

PART FOUR: SYSTEMATICS |

|||

|

Chapter |

9. Existential Hypotheses |

175 |

|

|

4.9.1. |

The Field of Scientific Inquiry |

175 |

|

|

The task of natural philosophy—specifiable groups of phenomena—phenomena relative to consciousness—knowledge of fact never more than approximate—revealed knowledge and knowledge of fact not reducible to any common denominator—MacTaggart's distinction of intensive and extensive facts. |

|||

|

4.9.2. |

The Relativity of Existence |

177 |

||

|

Levels of being common ground to mechanists and vitalists —Aristotle, J. S. Haldane, J. Huxley, J. B. S. Haldane, J. Needham, J. H. Woodger—morphology of G. St. Hilaire— S. Alexander's levels of existence—the relationship of more and less—togetherness as single-valued intensive magnitude. |

||||

|

4.9.3. |

The Scale of Being |

179 |

||

|

The transcendental morphologists—Buffon and Goethe— Aristotle and Cuvier—existence and wholeness—the scale of being must be one-dimensional. |

||||

|

4.9.4. |

Potency as the Criterion of Level |

180 |

||

|

Independence of the environment—how far is an entity itself?—individuation—the threefold character of existence, hypernomic, autonomic, and hyponomic—potency the maximum degree of individuation accessible to members of a class—experience stratified by a relationship of potency— behaviour-patterns and hypothesis formation. |

||||

|

4.9.5. |

Working Hypotheses |

183 |

||

|

Distinction between hypotheses and philosophical systems and summarized statements—phenomenology of Husserl —examples: Kepler and Copernicus—Faraday and Clerk Maxwell—Bell and Green—Balmer and Bohr—Mendel and Weismann—van Beneden and Platner—every working hypothesis relates to existence as well as to mechanism. |

||||

|

4.9.6. |

Hypotheses and Determining Conditions |

185 |

||

|

Margenau's requirements of a scientific hypothesis— Karl Pearson's 'construct'—the pattern of potency—Henri Poincare—hypothesis formation and will. |

||||

|

4.9.7. |

The Existential Hypotheses |

187 |

||

|

Systematic classification of the sciences—existential hypotheses the most powerful instruments of scientific investigation. |

||||

|

4.9.8. |

The Basic Hypotheses |

188 |

||

|

Three basic modes—twelve levels of potency—hyponomic dominant or physical existence—autonomic dominant or organic existence—hypernomic dominant or universal existence—transitional hypotheses. |

|

Chapter |

10. The Classification of the Sciences |

190 |

|

A. Subanimate Existence—Hyponomic Entities |

||

|

4.10.1. |

The Character of Hyponomic Existence |

190 |

|

The physical world passive in all its actualizations—a passive |

||

|

element is also present in entities of higher potency—hyle in |

||

|

the indeterminate ground state—determination of thing- |

||

|

hood. |

||

|

4.10.2. |

The Hypothesis of Existential Indifference |

191 |

|

Unipotent entities—framework laws independent of the |

||

|

nature of existents—generalized geometry—dynamics— |

||

|

statistics—semantics—logic—common character of frame- |

||

|

work sciences—knowledge of framework laws older than |

||

|

history—simple and primitive. |

||

|

4.10.3. |

The Hypothesis of Invariant Being |

193 |

|

Entities without mutual action and self-identical—bipo- |

||

|

tence—polar existence and forces—field theories. |

||

|

4.10.4. |

The Hypothesis of Identical Recurrence |

195 |

|

The perpetuum mobile—tripotent entities unobservable but |

||

|

approximations found in nature—electro-magnetic radia- |

||

|

tion—statistical mechanics and quantum theory. |

||

|

4.10.5. |

The Hypothesis of Composite Wholeness |

197 |

|

Change and endurance—composite wholeness dependent |

||

|

upon store of potentialities—quadripotence—the superfluity |

||

|

of means for the attainment of ends—thinghood. |

||

|

4.10.6. |

The Transitional Hypothesis of Active Surface |

198 |

|

The significance of the boundary surface—exchanges of hyle |

||

|

—Ostwald's world of disregarded sizes—the colloid state— |

||

|

potential energy gradients. |

||

|

4.10.7. |

The Bifurcation of Existence |

200 |

|

The direction of functional comprehensiveness—that of |

||

|

being-intensity. |

||

|

Chapter |

11. The Classification of the Sciences |

202 |

|

B. Animate Existence—Autonomic Entities |

||

|

4.11.1. |

The Character of Autonomic Existence |

202 |

|

Life the reconciliation of affirmation and denial—life and |

||

|

death—ableness-to-use the environment—self-preservation. |

|

4.11.2. |

The Hypothesis of Self-renewing Wholeness |

203 |

|

Organized potency—self-renewal and quinquepotence— non-reproductive self-renewal. |

||

|

4.11.3. |

The Hypothesis of Reproductive Wholeness |

205 |

|

Sexipotence—reproduction—growth and regeneration— cells—the stability of cell patterns—the cell as the atom of life. |

||

|

4.11.4. |

The Hypothesis of Self-regulating Wholeness |

207 |

|

Maintenance and regulation of functional balance—the septempotent organism—individuation begins with self-regulation—sexual reproduction—the seven-fold structure of the organism. |

||

|

4.11.5. |

The Hypothesis of Self-directing Wholeness |

209 |

|

The power of choice—conscious self-direction—octopo-tence and individuality—the role of conscious reconciliation. |

||

|

4.11.6. |

The Transitional Hypothesis of Biospheric Wholeness |

210 |

|

H. R. Mill, Suss, Vernadsky—the biosphere—all organic life as one whole—biospheres probably not limited to the earth —biological orders and the biospheric time-scale—eightfold structure of biosphere. |

||

|

Chapter |

12. The Classification of the Sciences |

|

|

C. Supra-animate Existence—Hypernomic Entities |

214 |

|

|

4.12.1. |

The Character of Hypernomic Existence |

214 |

|

Existence beyond life—the cosmic affirmation—Harding's 'Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth'—hypernomic existence associated with supra-individual consciousness. |

||

|

4.12.2. |

The Hypothesis of Sub-creative Wholeness |

216 |

|

'Mother Earth'—novempotence and pattern—living and dying as limitations of existence. |

||

|

4.12.3. |

The Hypothesis of Creative Wholeness |

217 |

|

The stars as atoms of the universe—creativity and decem-potence—independence of the stars. |

||

|

4.12.4. |

The Hypothesis of Super-creative Wholeness |

219 |

|

The galaxies—undecimpotence and domination—related-ness and transcendence. |

|

4.12.5. |

The Hypothesis of Autocratic Wholeness |

220 |

|

The knowable universe—duodecimpotence—autocracy as |

||

|

the ultimate fact. |

||

|

4.12.6. |

The Universal Systematics of Natural Philosophy |

221 |

|

The table of the classification of the sciences |

||

|

(a) Hyponomic dominating—the physical world—things |

||

|

(b) Autonomic dominating—the animate world—life. |

||

|

(c) Hypernomic dominating—the supra-animate world— |

||

|

celestial existence. |

||

|

SECOND BOOK: THE NATURAL SCIENCES |

||

|

PART FIVE: THE DYNAMICAL WORLD |

||

|

Chapter |

13. The Representation of the Natural Order |

229 |

|

5.13.1. |

The Natural Order |

229 |

|

The affirmation of a natural order as a fundamental axiom |

||

|

—yet order not absolute—'Without disorder freedom impos- |

||

|

sible—determining conditions subject to relativity of exis- |

||

|

tence. |

||

|

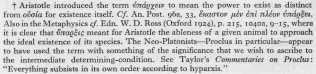

5.13.2. |

The Inexhaustibility of Phenomena |

230 |

|

The spurious dichotomy of appearance and reality—repre- |

||

|

sentation of experience by diagram of unity, function, being, |

||

|

and will—human thought limited to pairs of these four— |

||

|

natural philosophy mainly concerned with function—unity |

||

|

as self-consistency of natural order—framework as omni- |

||

|

presence of universal laws—the stratification of existence. |

||

|

5.13.3. |

Mathematics |

233 |

|

Mathematics as abstract language of the will—paradox of |

||

|

universality of mathematics and non-mathematicalness of |

||

|

sense experience—the gestural quality of mathematics— |

||

|

mathematical operators—mathematics the characteristic |

||

|

language of the natural order. |

||

|

5.13.4. |

The Representation Manifold |

236 |

|

Will and the triad—mathematics and three-term relation- |

||

|

ships—means of description—representation an act of will |

||

|

relating behaviour to framework—the representation mani- |

||

|

fold. |

||

|

5.13.5. |

The Geometric Symbols |

238 |

|

|

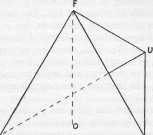

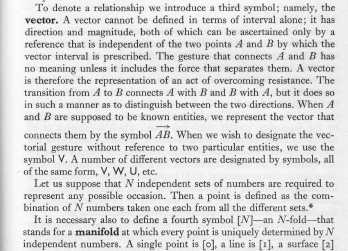

Geometry—dimensions—wholeness and points—polarity and intervals—relationship and vectors—subsistence and pencils—[N]-folds. |

|||

|

5.13.6. |

Geometry |

240 |

|

|

The representation of framework without reference to existence—time, eternity, and hyparxis as internal determining-conditions—space as external determining-condition. |

|||

|

5.13.7. |

Eternity as a Fifth Dimension |

241 |

|

|

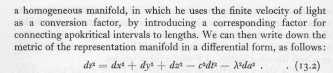

Einstein and Minkowski—null-intervals—cosmodesics— null-vectors and null angles—conservative systems require five-dimensional manifold—angular momentum and sixth dimension. (cf. Appendix to Chapter 13, p. 490, Five-Dimensional Physics. |

|||

|

5.13.8. |

The Existential Tract and the Cosmodesic |

243 |

|

|

All possible conservative inner states representable in existential tract—unconstrained actualizations and cosmodesics —representation applies only to facts and not to phenomena directly. |

|||

|

5.13.9. |

Eternity-blindness |

245 |

|

|

Human sense-perceptions confined to actualizations— potentialities extended in eternity—not perceived—can nevertheless be inferred. |

|||

|

5.13.10. |

The Universal Observer Q |

246 |

|

|

Measurements in the existential tract—representation manifold of Q—Q's direction of eternity unique—Q's manifold free from curvature. |

|||

|

Chapter |

14. Motion |

248 |

|

|

5.14.1. |

Non-interacting Relatedness |

248 |

|

|

Simplification of representation possible for invariant being—interaction not studied in dynamics—approximation to a perpetuum mobile—consistent and inconsistent related-ness—kinematical sciences—wave forms—rigid connectedness and ideal plasticity. |

|||

|

5.14.2. |

Relative Rigidity and Quasi-rigidity |

250 |

||

|

Entities and instruments of dynamical science—rulers and clocks—meaning of 'rigidity'—congruent transformations —relativity of measurements—quasi-rigid bodies. |

||||

|

5.14.3. |

The Entities of Dynamical Science |

253 |

||

|

The observations of O and Q—linkage of inner and outer determining-conditions—triangulation—potential energy and apokritical interval—the universe U—the universal observer Q—the human observer O—the massive space-extended rigid object M—the measuring system O-M-R— the observed object P. |

||||

|

5.14.4. |

The Laws of Motion |

257 |

||

|

The basic dynamical experiment—the two fundamental directions of time and eternity—the fact of eternity-blindness—unobservable constraints—accelerations as displacements in eternity—unified field theory in five dimensions. (cf. also Appendix to Chapter 14, p. 499, 'Unified Field Theory—Simplified Mathematical Treatment'.) |

||||

|

PART SIX: THE WORLD OF ENERGY |

||||

|

Chapter |

15. The Universal Geometry |

263 |

||

|

6.15.1. |

The Representation of Relatedness |

263 |

||

|

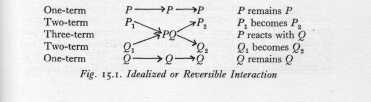

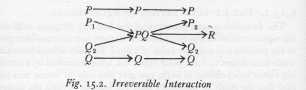

The representation of coupling requires magnitudes distinct from mass and charge—geometry of reversible interaction—kinds of interaction. |

||||

|

6.15.2. |

Types of Relatedness |

265 |

||

|

Simple and compound entities—relationships—internal and external—conjunctive and disjunctive—external and conjunctive relationships governed by hyparxis. |

||||

|

6.15.3. |

The N-dimensional Geometry |

267 |

||

|

N-dimensional geometry—postulate of homegeneity of all hyponomic occasions—N-dimensional manifold divided into two independent sub-manifolds K and J—four kinds of interval required. |

||||

|

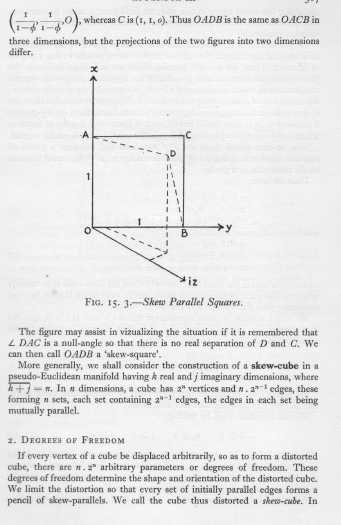

6.15.4. |

Skew Parallelism |

268 |

||

|

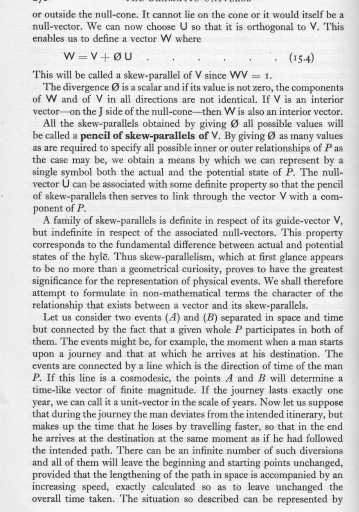

Skew-parallelism—extension of Minkowski's four-dimensional geometry—definition of pencil of skew-parallels— guide-vectors and null-vectors. |

||||

|

6.15.5. |

Pencils of Skew-parallels |

271 |

||

|

Tripotence of skew-parallels—transitive and intransitive |

||||

|

forms—degrees of freedom—(a) the alpha-pencil—(b) the |

||||

|

beta-pencil (c) the gamma-pencil—(d) the delta-pencil. |

||||

|

6.15.56. |

The Four Types of Pencil and the Four Determining- |

|||

|

conditions |

274 |

|||

|

The alpha-pencil and eternity—the beta-pencil and time— |

||||

|

the gamma- and alpha-pencils being transitive correspond |

||||

|

to space and eternity—delta-pencils and hyparxis—the |

||||

|

simple harmonic oscillator—the rotational and hence |

||||

|

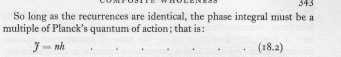

recurrent character of delta-pencils—quantization of |

||||

|

hyparxis. |

||||

|

6.15.7. |

Characteristics of the Universal Geometry |

278 |

||

|

Distinction between a conventional and a concrete geometry |

||||

|

—thirteen characteristic requirements of an universal |

||||

|

geometry. |

||||

|

6.15.8. |

The Sixth Dimensionality of the Hyponomic World |

279 |

||

|

All characteristics of hyponomic entities and their occasions |

||||

|

must be susceptible of representation in the [6] geometry— |

||||

|

over-specification and under-specification—the theorem of |

||||

|

fitness of the manifold—(for proof of the theorem refer to |

||||

|

Appendix III, Chapter 15, p. 506, 'The Geometrical Repre- |

||||

|

sentation of Identity and Diversity'.) |

||||

|

Chapter |

16. Simple Occasions |

282 |

||

|

6.16.1. |

Simple Interactions |

282 |

||

|

Simple events—occasions without change—universe of two |

||||

|

identical elastic spheres. |

||||

|

6.16.2. |

Reversibility |

282 |

||

|

Discussion of the two-sphere universe—illustrating how |

||||

|

potentialities constitute a reserve of energy. |

||||

|

6.16.3. |

The Quantum of Action. |

285 |

||

|

The significance of action—Maupertuis, Hamilton, and |

||||

|

Helmholtz—least and varying action—the delta-pencil has |

||||

|

exact requirements for representing action—action and |

||||

|

coupling—action and ableness-to-be—Planck's quantum |

||||

|

of action as unit of hyparchic magnitudes. |

||||

|

6.16.4. |

Electro-magnetic Radiation |

289 |

|

Counterparts in eternity as projection of hyparchic recurrences—properties of electro-magnetic radiation—projection from hyparxis via eternity into space-time—energy and momentum of light. |

||

|

6.16.5. |

Geometrical Mechanics |

292 |

|

Kaluza, de Broglie, Rosenfeldt, and Podalanski—quantization of our framework inherent in rotational character of delta-pencil—Schrodinger and Born wave-function. |

||

|

6.16.6. |

The Concept of Virtuality |

293 |

|

Virtuality defined as state of hyle in which entities exist without determination—virtual state unobservable—reservoir of existence—conservation of potentialities—the corpuscular state and the determining conditions. |

||

|

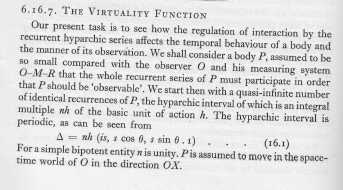

6.16.7. |

The Virtuality Function |

296 |

|

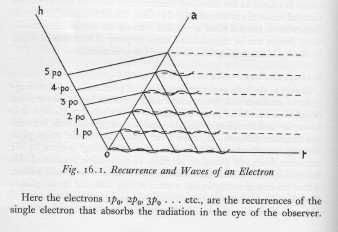

The rotational property of the delta-pencil projects into wave in eternity—wave function as measure of virtuality— description of the delta-pencil—the circle in eternity (ikl, ilm, k cos 0, k sin 0, 0)—the material wave equations. |

||

|

6.16.8. |

The Solitary Electron in the Hyle-field |

298 |

|

Potential energy field of infinitesimal intensity called the 'hyle-field'—Eddington's solitary electron universe— relativistic de Broglie equation for material wave. |

||

|

6.16.9 |

The Potential Energy Barrier |

299 |

|

Experiment of electron diffraction—explanation in terms of hyparchic oscillator. |

||

|

PART SEVEN: THE WORLD OF THINGS |

||

|

Chapter |

17. Corpuscles and Particles |

305 |

|

7.17.1. |

Unipotence—the Emergence of Materiality |

305 |

|

Equipotent layers as determining levels in eternity—four gradations of hyponomic world—further discussion of the hyle—relativity of materiality—illustration of ocean, spray, and vapour. |

|

7.17.2. |

The Corpuscular State—Bipotence |

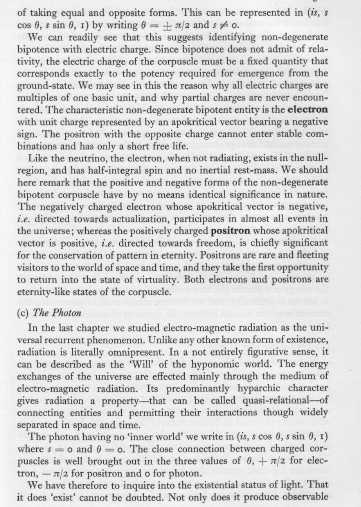

308 |

|

Corpuscle defined as hyle determined but not individuated |

||

|

—corpuscular occasions reversible and not identifiable— |

||

|

corpuscles bipotent—without identity—the four types of |

||

|

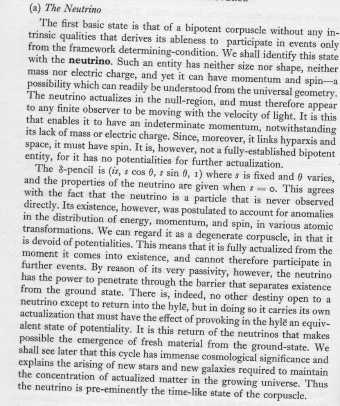

corpuscle: (a) the neutrino—(b) the electron and positron |

||

|

—(c) the photon—(d) the corpuscular mesons—characteris- |

||

|

tics of each related to the determining conditions—the |

||

|

corpuscular state universal. |

||

|

7.17.3. |

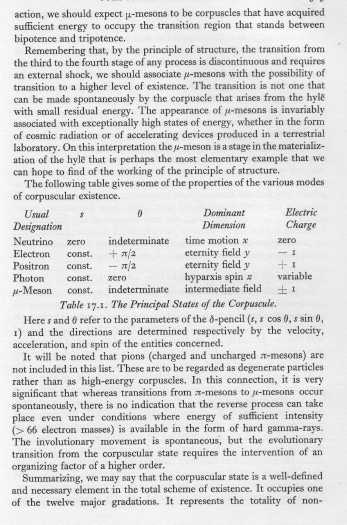

The Particulate State—Tripotence |

314 |

|

Tripotence—the particle as simple tripotent entity having |

||

|

no parts—particles relational—particles massive—but not |

||

|

subsistent—protons, neutrons, nucleons, and heavy mesons. |

||

|

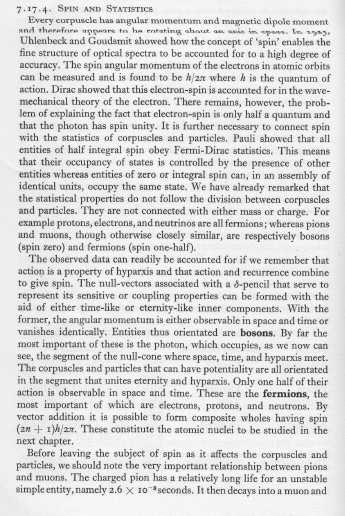

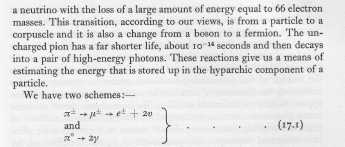

7.17.4. |

Spin and Statistics |

318 |

|

Electron spin and quantum numbers—half-integral spin |

||

|

and Fermi statistics—zero and integral spin and Bose |

||

|

statistics—the components of the delta-pencil in time, |

||

|

eternity, and hyparxis—identification of fermions and |

||

|

bosons with time- and eternity-like orientation—dis- |

||

|

cussion of pions and muons—gravitation and the speed of |

||

|

light. |

||

|

7.17.5. |

The Threefold Character of Time |

319 |

|

Presence of existing entities links the determining conditions |

||

|

—whereby each acquires some of the characteristics of |

||

|

the remainder—time-like time actual and successive—etern- |

||

|

ity-like time virtual and conservative—hyparxis-like time |

||

|

recurrent and irreversible. |

||

|

7.17.6. |

The Regenerative Ratio |

322 |

|

Irreversibility as universal property—the universal decay |

||

|

constant—non-degenerative entities have perfect regenera- |

||

|

tive ratio between potentiality and actualization—the exact |

||

|

regenerative ratio R defined—the hypothesis of temporal |

||

|

equivalence—the ratio between dynamical and thermo- |

||

|

dynamical measures of time—evaluation of R—discloses |

||

|

connection with the fine structure constant of atomic |

||

|

spectra—R as a measure of ableness-to-be—Eddington's |

||

|

deduction of x. |

||

|

Chapter |

18. Composite Wholeness |

328 |

|

7.18.1. |

Quadripotent Entities |

328 |

|

Meanings of the word 'thing'—part and whole—definition |

||

|

of composite wholeness—change without ceasing to be one- |

||

|

self—the pattern of potentialities and the life-history—the |

||

|

threefold aspect of composite wholeness. |

||

|

7.18.2. |

Intensive, Extensive, and Coupling Magnitudes |

331 |

|

Coupling magnitudes associated with hyparxis—encoun- |

||

|

tered in experimental physics—heat content and magnetic |

||

|

energy—coupling theorem for composite wholeness—the |

||

|

relationship of tripotent and quadripotent entities. |

||

|

7.18.3. |

The Coupling of Recurrences |

332 |

|

The transfer of potentialities from eternity into hyparxis— |

||

|

the coupling energy—projection into space-time—distinc- |

||

|

tion of internal coupling composite wholes which are the |

||

|

atomic nuclei and externally coupled which comprise all |

||

|

space-extended objects—atomic nuclei as degenerate quod- |

||

|

tripotent entities. |

||

|

7.18.4. |

The Stability of Composite Wholes |

334 |

|

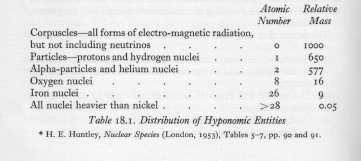

Coupling energies of the atomic nuclei—beryllium and |

||

|

helium—factors determining stability—distribution of mass |

||

|

among different hyponomic entities, corpuscles, particles |

||

|

and heavy nuclei—rarity of stable composite wholes more |

||

|

complex than alpha particles. |

||

|

7.18.5. |

The Atomic Nucleus |

337 |

|

Factors determining stability of nuclei—models of the |

||

|

nucleus—antinomy of droplet and shell models—reconciled |

||

|

by distinguishing eternal and hyparchic elements—chief |

||

|

characteristics of nucleus accounted for with our model— |

||

|

stable nuclides and the magic numbers—example of zircon- |

||

|

ium—nuclear isomerism. |

||

|

7.18.6. |

The Masses of the Nuclides |

340 |

|

General formula for stability of nuclides—the mass defect |

||

|

formula—mass of heaviest stable nuclei predicted from |

||

|

regenerative ratio—uranium and trans-uranic elements. |

||

|

7.18.7. |

The Neutral Atom |

342 |

|

The atom and the problem of the non-radiating electron |

||

|

resolved in terms of identical recurrence—simple character |

||

|

of atomic subsistence. |

||

|

7.18.8. |

The Chemical Bond |

344 |

|

Polar and non-polar linkages—Heitler-London model— |

||

|

increase of potentiality in passing from atomic to molecular |

||

|

species. |

||

|

7.18.9. |

Heat |

346 |

|

The hyparchic character of specific heat—the meaning of |

||

|

'temperature'. |

|

7.18.10. |

Material Objects The structure of the hyponomic world—the properties of material objects not wholly predictable from atomic considerations—the van der Walls forces—surface forces and passive endurance. |

347 |

|

7.18.11. |

The Higher Gradations of Thinghood The whole and part relationship—passively adapted quadripotent entities—example of pebble—things have recognizable pattern—things of autonomic origin—things as instruments—universal character of quadripotence. |

349 |

|

PART EIGHT: LIFE |

||

|

Chapter |

19. The Bases of Life |

353 |

|

Autonomic Existence Life as the reconciliation of creativity and mechanicalness —support of consciousness—pervasive role of life—life exemplifies potentiality—life not definable in functional terms alone—sensitivity common to all life. |

353 |

|

|

8.19.2. |

Sensitivity-Sensitivity associated with hyparxis does not imply pan-psychism—sensitivity connected with coupling but only organized in life—organized sensitivity is first law of biology. |

356 |

|

8.19.3. |

Rhythm Rhythm the organization of repetition—associated with hyparxis—second law of biology—rhythm is the second condition of life. |

357 |

|

8.19.4. |

Pattern Pattern as organized structure—pattern is affirmation of higher order—the interplay of organization and disorganization—third law of biology—the pattern of interacting potentialities is the third condition of life—Maurice Vernet and fundamental excitability. |

358 |

|

8.19.5. |

Individualization The individual as self-directing—the completed manifestation of the autonomic world—individuality and consciousness. |

359 |

|

8.19.6. |

The Threshold of Life The four autonomic existential hypotheses—characteristics of life: excitability, specificity, flexibility, and stability— the significance of surfaces. |

360 |

|

8.I9.7. |

The Colloidal State Surfaces and surface layers—free surface energy of colloids —potential energy gradient—sensitivity of colloids—the hypothesis of active surface. |

361 |

|

8.19.8. |

The Significance of Protein Complexity of living matter—the inherent variability of proteins—inaccessibility of protein forms—Leathes and Gort-ner—protein isomerism—structure of proteins and organizing pattern. |

363 |

|

8.19.9. |

The Enzymes Enzymes as autonomic agents—their connection with inorganic catalysts—auto-catalytic nucleic acids—synthesis of proteins. |

366 |

|

Chapter |

20. Living Beings |

369 |

|

8 .20 .1 . |

The Triad of Life Physico-chemical laws and the directiveness of organic activity—J. S. Haldane and E. S. Russell—vitalism and mechanism—neither concept adequate—life and the sensitive state of hyle—neither active nor passive—polymorphic sensitivity. |

369 |

|

8.20.2. |

Quinquepotence—Viruses The virus analogous to the corpuscle—dependent upon cells —colloidal character—specificity of viral proteins—four gradations of quinquepotence: proteins, enzymes, crystalliz-able viruses and cell-forming viruses—complexity of virus structure—response to radiation—basis of all life—virus as degenerative autonomic existence—dimorphic sensitivity. |

370 |

|

8.20.3. |

Sexipotence—the Cells Definition of cell as reproductive unity—six characteristics of cell life—of these, reproduction alone specific—protoplasm as ground state of life—mitosis and meiosis— Virchow, Sherrington, and Woodger—the cell not individualized—sensitivity of cells—reproduction as reconciliation of eternity and time. |

376 |

|

8.20.4. |

Septempotence—Organism |

381 |

|

The organic structure—eternal pattern—temporal history— |

||

|

hyparchic self-regulation—plant and animal morphology— |

||

|

St. Hilaire and Richard Owen—structure physiological |

||

|

rather than anatomical—also relates to development— |

||

|

embryology, (a) the pattern of potentialities—(b) differen- |

||

|

tiation—(c) determination—(d) self-regulation. |

||

|

8.20.5. |

The Hyparchic Regulator |

386 |

|

Driesch and experimental morphogenesis—the structure |

||

|

of sensitivity — fertilization — gastrulation — neurulation |

||

|

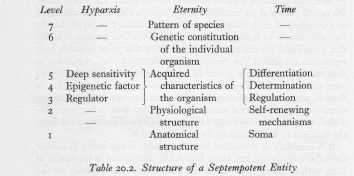

—the hypothesis of the hyparchic regulator—table showing |

||

|

structure of septempotent entity—genetic characteristics |

||

|

and the eternal pattern—acquired characteristics and the |

||

|

hyparchic regulator. |

||

|

8.20.6. |

The Cycle of Life and Food |

388 |

|

The cycle of life processes from fertilization to death—the |

||

|

duration of life—virtue regeneration and food—table |

||

|

showing states of hyle in septempotent entities— |

||

|

autotrophic vegetation—reciprocal maintenance—the chem- |

||

|

ical elements essential for life—the struggle for existence— |

||

|

the hazards of life necessary for its autonomic role— |

||

|

hazard alone makes it possible for an entity to be itself. |

||

|

8.20.7. |

The Hazards of Life |

393 |

|

The physiological variability—the pathological limits of |

||

|

existence—the limitations of the hyparchic regulator—the |

||

|

epigenetic factor as superior regulator—eternal pattern as |

||

|

final resource—conditions of life sensitive to the regulative |

||

|

mechanisms—organic sensitivity and non-adaptive charac- |

||

|

ters—the three hyparchic factors—regulator, epigenetic |

||

|

factor and organic sensitivity—organic sensitivity as the |

||

|

seat of consciousness. |

||

|

Chapter |

21. The Unity of Life |

397 |

|

8.21.1. |

Octopotence—Complete Individuality |

397 |

|

Life required to exist between polar forces of hypernomic |

||

|

and hyponomic worlds—consciousness as the reconciling |

||

|

factor in all the conflicts of existence—individuality more |

||

|

than sensitivity—both historical and non-historical—indivi- |

||

|

dual not a machine—self-determination implies the power |

||

|

of choice—animals sensitive only, not individualized. |

|

8.21 |

.2. |

The Conditions of Choice |

400 |

|

Tenderness and toughness of the living organism—com- |

|||

|

plexity of regulating mechanism—consciousness situated |

|||

|

in epigenetic factor can give experience of choice—rarity |

|||

|

and sporadic character of voluntary action—a statistical |

|||

|

analysis of voluntary and involuntary actions—human acts |

|||

|

of choice mostly trivial. |

|||

|

8.21 |

.3. |

The Gradations of Individuality |

402 |

|

Distinction drawn between individuation and individualiza- |

|||

|

tion—true individuality implies potency to initiate processes |

|||

|

—depends upon consciousness of epigenetic factor—man |

|||

|

as a degenerate individual—three gradations of true indivi- |

|||

|

duality—(a) consciousness of genetic constitution, giving |

|||

|

ableness-to-be oneself—(b) awareness of pattern of species |

|||

|

—(c) awareness of universal cosmic role of life. |

|||

|

8.21 |

.4. |

Organism and Species |

404 |

|

Genetic constitution and sexual reproduction—division of |

|||

|

sexes permits distinction of inner and outer worlds—not |

|||

|

separate organisms but whole species constitute the true |

|||

|

individuals—the stability of species and their coherence— |

|||

|

zoological and botanical specificity—stability of the eternal |

|||

|

pattern—illustrated by examples from genetic science. |

|||

|

8.21 |

.5. |

The Unity of the Species |

407 |

|

The septempotent organism as 'atom' of the species— |

|||

|

species and environment—Ouspensky,Thompson,Coleridge, |

|||

|

and Dobzhansky—unity and integrity of the species— |

|||

|

Vernet's formulation—the specificity of the sensitive |

|||

|

excitability of the organism—characteristic rhythms |

|||

|

of species—the norm or specific pattern—the species |

|||

|

dominates the type—stability of species not ultimate— |

|||

|

genera, families, and orders. |

|||

|

8.21 |

.6. |

The Origin of Species |

411 |

|

Distribution of variations—lack of evidence that the new |

|||

|

eternal pattern can arise through mutation and selection— |

|||

|

observed variability ascribed to hyparchic regulator—the |

|||

|

species as a conscious individual—discussion of objections |

|||

|

—taxonomy and the patterns of organic life—inadequacy |

|||

|

of ordinary mutations—Goldschmidt, Haldane, and Fisher |

|||

|

—origin of species neither causal nor purposive but regula- |

|||

|

tive—taxonomic criteria—the hyparchic regulator of bio- |

|||

|

sphere true source of ecological order—organic excitability— |

|||

|

arising of species illustrated by Crataegus—mechanism of |

|||

|

speciation and the formation of new genera—synthesis of |

|||

|

species Galeopsis tetrahit—three factors. |

|

8.21 |

.7. |

The Biosphere |

419 |

|

Life on earth recurrent series of biospheric existences—the |

|||

|

biosphere as higher gradation of true individuality—exem- |

|||

|

plifies trimorphic octopotence—orthogenesis as biospheric |

|||

|

counterpart of epigenesis in the organism—the eternal |

|||

|

pattern of separate genera derived from general pattern of |

|||

|

the biosphere—Suss, Vernadsky, Goldschmidt and Vino- |

|||

|

gradov—the analogy of the biosphere and the colloids— |

|||

|

both two-dimensional—the biosphere as transition from |

|||

|

autonomic to hypernomic existence—role of the biosphere |

|||

|

in the earth's history—the concentrations of the elements |

|||

|

—transformations of energy—the biosphere related to the |

|||

|

sun and moon—the time cycles of the biosphere—the |

|||

|

dominant forms of life in each biospheric cycle—the con- |

|||

|

sciousness of the orthogenetic factor. |

|||

|

8.21 |

.8. |

The Hypernomic Role of the Biosphere |

424 |

|

Pattern to which existence of biosphere conforms—pattern |

|||

|

derives from planet—creativity of sun reconciled with |

|||

|

earth pattern—individuality of biosphere—transformation |

|||

|

of energies required for higher forms of existence—special |

|||

|

character of biospheric energies. |

|||

|

PART NINE: THE COSMIC ORDER |

|||

|

Chapter |

22. Existence Beyond Life |

429 |

|

|

9.22 |

..1. |

The Four Hypernomic Gradations |

429 |

|

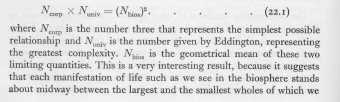

Immortality a state beyond life—organizing power that |

|||

|

regulates existence but without participating—'existence |

|||

|

beyond life' discussed—F. Schiller—Plato—-the hyper- |

|||

|

nomic gesture—the universe neither mechanical toy nor |

|||

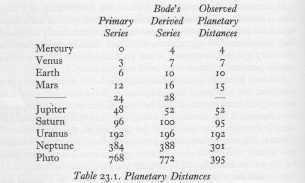

|