5 - The 'Kami Way' of Japan

Way back in the very beginning (according to Japanese folklore)—before anything else existed—there was the god of the Centre of Heaven, or Ame-no-minaka-nushi-no-kami. Then two other gods appeared: of birth and of growth.

Next, Izanagi-no-mikoto and Izanami-no-mikoto came down from the High Plain of Heaven and gave birth to everything there is, including the great Eight Islands (or Japan), and many gods (or kami) as well.

The most powerful of these was the Sun Goddess, kami of the High Plain of Heaven. Her brother was kami of the Earth, and the Moon Goddess was kami of the world of darkness.

But kami, although divine, are not always perfect, and long ago (in what we might call the Dreamtime of Japan) the Sun Goddess's brother behaved so badly toward her that she took refuge in a cave, high up in the heavens, and darkness fell upon the whole world.

Nothing like this had ever happened before. Her brother was promptly cast out into the lower realms, while up in the heavens a host of kami—anxious and dismayed—tried their hardest to entice the Sun Goddess out again by dancing and playing music around the entrance of her cave.

Fortunately their efforts were not in vain. She at last relented and reappeared, whereupon light returned to the heavens and the earth.

Happily, things also went well for her brother. In exile, his good conduct was such that he won his way back into the good graces of the other kami, and one of his descendants (the kami of Izumo) ruled over the Eight Islands with great wisdom and kindness.

Next, Ninigi-no-mikoto (the Sun Goddess's grandson) was told that he must go down and become the ruler of Japan. And, as symbols of his power, he was given three special tokens: a mirror, a sword, and a string of gemstones.

Once down on Earth, he had friendly discourse with the kami of Izumo, who finally agreed to give over to him the rulership of the outer world while he himself took charge of that other world beyond human sight. He also promised to watch over and protect Ninigi-no-mikoto in every possible way.

Ninigi-no-mikoto governed Japan wisely and well, and eventually it was his great-grandson who, as the Emperor Jimmu, became the first mortal ruler of Japan.

Kami are never Strangers

Certainly this story goes back into the misty past, yet the kami of the Japanese people have never remained in the long-ago or far-away. Rather, they are everywhere and all the time. Kami are rocks, mountains, trees, rivers, animals, and everything else in the natural world. Kami are the stars, the sun and the moon. They are the spirits of noble ancestors and national heroes, also of thinkers and inventors who have done great works. They are the guardian spirits of certain groups or territories, and some of them can even be responsible for such things as the distribution of water and the making up of medicines.

Kami stand for order and justice, and for the happiness that comes when people live and work together peacefully.

Kami are also the spirits of ordinary human beings, of what we call 'the man and woman in the street'. And since kami are always thought of with feelings of reverence, this is probably the reason why most Japanese people are so generous and courteous.

No wonder that the great religion of Japan is called Shinto, which means 'the kami way'. And considering that the kami are as closely interwoven with Japan's history as they are with the daily experiences of its people right down to the present time, it seems only natural that Shinto was never begun or introduced by any one person.

There was Moses for Judaism, Mohammed for Islam, Jesus for Christianity, but generation after generation of Japanese people themselves for Shinto.

Neither are there any sacred scriptures for Shinto, explaining it or laying down its rules, nothing to which kami-worshippers can go for reference. So it is not surprising that there is much about Shinto that even the Japanese themselves do not clearly understand. Yet this is not particularly important, for it of ten happens that when we reason about a thing too much, we lose the spirit of it, whereas Shinto is something that the Japanese truly feel— in their daily lives, and in the world and the people around them.

We have already seen how Hindus worship many gods, whereas in reality the God of Hinduism is only One. And we might, in a sense, say the same thing about Shinto, although Shinto doesn't actually name any one supreme being, or creator. Instead, there is a realisation that harmony and goodwill among people, towards one another and the natural world, will somehow be reflected and rejoiced over among the kami. And out of such joyous harmony, creativeness arises. So we might say that Shinto recognises a state of harmony as the Creator.

The Shrines of Shinto

But of course, this does not prevent the people in general from doing homage to any number of separate kami for whom they might have special sentiment or affection. And the proper place to do such homage is a shrine. So, considering that kami are ever-present in the lives, thoughts and feelings of the Japanese people, it is to be expected that the shrines of Shinto should be part and parcel of the 'scenery' of Japan. As indeed they are. And a very beautiful part too, blending so perfectly with their surroundings that they often look as if they have actually grown there, just as the trees, the bamboo bushes, the mosses and the ferns have grown.

Ideally, a Shinto shrine is set in a forest or a grove— wherever Nature is at its loveliest—for it has always been well known that kami feel happiest and most 'at home' in such places.

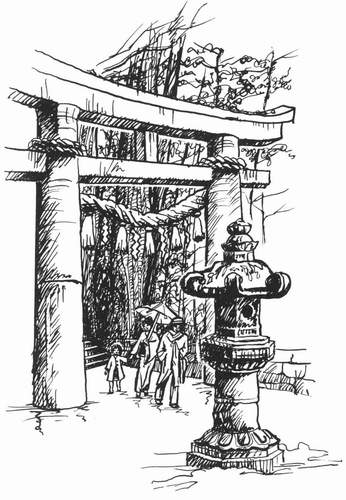

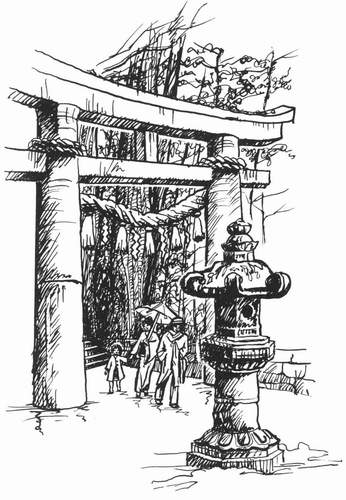

Usually you have to climb long flights of steps to reach a shrine. And perhaps at the beginning of the steps, or farther away still, is a special gateway (or torii) telling whoever passes through it that this is now sacred ground, with the ordinary world left behind.

The shape of a torii is beautifully simple—two upright pillars with a beam across the top—and it is as much a part of Japan as are cherry-blossoms and fans.

Often you will see young men standing near a torii and throwing pebbles, hoping that one at least will settle on the top of it, for if it does, the meaning is 'great good luck'.

As well as little piles of pebbles on top, a torii usually has a heavy straw rope stretched across it, hung with zigzag paper strips. These are special reminders of the kami, and offerings to them as well.

All trees are cherished by the kami, and therefore also by the Japanese. But there is sometimes a particularly sacred one, perhaps actually the dwelling-place of a kami, and this will have an enclosure around it, and a straw-rope 'girdle' about its trunk with short strips of paper hanging from it. It may also have a tiny torii all to itself. It may be within the grounds of a shrine, or far away somewhere in the middle of a forest.

After you pass through the large temple torii, you will often find beautiful stone 'lanterns' placed on either side along the walkway. Sometimes these are covered with moss, and have been standing there for hundreds of years.

Often too, as special guardians, there are animal figures carved in stone: usually dogs and lions, looking rather ferocious to frighten off evil spirits. And sometimes there are monkeys, foxes, deer and horses, all ready to do service to the kami.

The Shinto Way of Praying

If you were a Japanese, you would probably be serving the kami in some way—by 'feeling' them, with reverence, in your innermost soul, and by making small daily offerings to them, just to prove your devotion.

Your gift might be quite simple, like rice, salt, fish, grain, cakes. It might be a piece of silk or cotton cloth, perhaps money or jewels, or simply a sprig of the sacred sakaki tree, or a bunch of flowers. You would place this in front of your own little household shrine, or else take it to a large public one.

Before approaching or worshipping the kami, however, you would 'purify' yourself by rinsing your mouth and fingertips.

Having made your offering, you would bow in front of the shrine, murmur words of praise to the kami, express gratitude or make some special request. You would also state who you are, and describe the gifts you have brought.

You would make sure of attracting the kami's attention by clapping your hands twice, or by ringing a bell if one should happen to be placed there, and you would leave only after again bowing and expressing your devotion and awe.

You might then buy a printed prophecy of your future, and after reading this carefully, you would fold it lengthwise and twist it around a twig or a piece of wire meshing nearby, as a means of asking the kami to fulfil the prophecy if it is good, or to protect you if it is bad. And, since so many thousands of people do this, the wire-netting enclosures, as well as any small trees and bushes around public shrines, look as if they are covered with pure-white blossom, or with snow.

The Essence of Shinto

Unless you were an actual attendant at the shrine, you wouldn't normally enter its inner sanctuary. But if you did, you would find that one of the most sacred objects there was a mirror—doubtless in memory of the mirror that Ninigi-no-mikoto brought down with him from the High Plain of Heaven.

It is said that this original mirror used to be held in the central shrine in the grounds of the emperor's palace, Then, centuries later, it was moved to the inner shrine at Ise. So naturally, this shrine at Ise is the most sacred in all Japan. It is dedicated not only to the great Sun Goddess, but to the feeling of respect for the emperor, and to the whole history, ancestry and culture of the Japanese nation.

There are many Buddhist images and temples in Japan, and many thousands of Japanese Buddhists. But whereas Buddhism is a 'travelling' religion which has found its way into many countries, Shinto is wholly Japanese, with more than 60 000 000 followers. In a very real sense, Shinto is Japan, and it would be hard to imagine it anywhere else.

Also, it would be difficult to find anyone who could clearly explain Shinto, for it is not learnt so much as felt. You feel it in the beauty of Nature, which gives you a sense of closeness with the kami. You feel it in the thrill of approaching a shrine, and in the mystic rites that you perform there. You feel it in the goodness and harmony of the whole world, protected as it is by the unlimited blessings of the kami.

Bad things do happen in the world, to be sure, but these do not come from man or from any other part of the natural world. Whatever form they may take—accidents, disasters, pollution, war—they are evil (or maga) and are caused by evil spirits (or magatsuhi) which came from the world of darkness and must somehow be sent back there.

Man himself is a child of the kami (in the same way that Christianity refers to people as 'children of God')—and if he is tempted into behaving badly, this again is something which has come from outside his own true self, for his true self is wholly good.

In fact, the entire world is, in reality, good, since the kami are everything and everywhere: living things as well as non-living, matter as well as spirit. But if man is actually to experience them in his life, he himself must do something about it.

He must constantly recognise the presence of the kami or, as other religions would say, Brahman, Allah, Jehovah, God. He must constantly realise his own oneness with them, and work toward harmony, brotherhood and peace. In this way he will be able to keep maga where it belongs—in the world of darkness. And he will truly be able to experience Heaven on Earth.