9 - The Growth of Christianity

Christianity, together with Buddhism and Islam, is one of the world's three most widespread religions. Jesus told his apostles that they must 'go forth', carrying the message of love and forgiveness far and wide, and they obeyed him immediately. Only a few weeks after the crucifixion, they were already moving out among people telling them the glad tidings that the Messiah had indeed come, and had brought healing, joy, and life eternal for all who would follow him. And not only that he had come, but that he was with them even now, and would be forever. I am with you always, even unto the end of the world,' he had said.

At first the apostles—all of whom were Jews—moved about and spread the word only among other Jews. But then Simon Peter, who was the leader of the apostles, and who had been the first one to recognise the Christ in Jesus, had a vision in which he was told that he should go out also among the non-Jews, or Gentiles. He obeyed this command, and so began the real missionary work of the Christians, which, through the centuries, has taken them into the farthest and strangest corners of the globe. It is a work that has brought great joy, but also hardship, danger, and even death.

The first of the Christian martyrs was a man called Stephen, who was stoned to death because of his faith. But this was only the beginning. Countless numbers of Christians were cruelly persecuted and put to death for more than 300 years. Yet the harder the Roman authorities and the Pharisees tried to stamp them out, the greater their numbers grew.

Paul of Tarsus

Perhaps there was no one person more determined to see them wiped out than a man who lived in the Cilician city of Tarsus. This man belonged to a Jewish family, but was also a Roman citizen, so he was known by both his Jewish name, Saul, and his Roman name, Paul. He was an exceptionally clever and studious man, well versed in the learning of his day, and in every detail of Hebrew law.

Not long after the crucifixion, the Pharisees of Jerusalem sent a message to Paul, asking him to come and help destroy a troublesome group of people who called themselves Christians, and who were openly defying the law of their forefathers.

Eager to help, Paul set out for Jerusalem, and there hunted down the Christians with terrifying thoroughness and cruelty. Then, learning that their numbers were also increasing in Damascus, he set out to destroy them there as well.

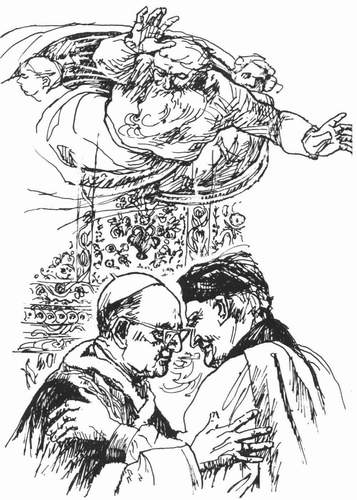

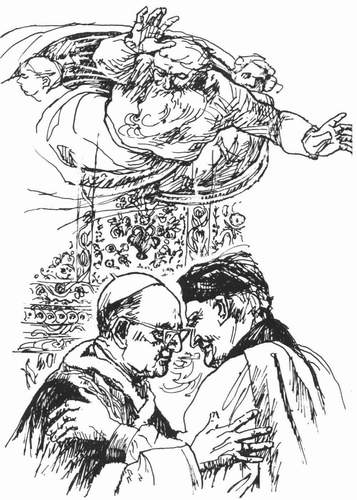

But a strange thing happened to him on the way. A vision of the Christ confronted him with such power and radiance that he fell from his horse, blinded, and when he rose to his feet again, he did so not as the persecutor of Christ's followers, but as their champion and mouthpiece—one of the greatest in the whole history of Christianity.

While Simon Peter founded the first Christian Church, and carried the words of Jesus and the spirit of Christ throughout all the lands nearby, Paul of Tarsus carried them much farther, even crossing the seas into foreign countries. Wherever he went he organised the Christians into groups or churches, renewed their courage and their strength, and greatly increased their numbers with his inspiring words.

Jesus's teaching was, above all, a teaching of love—and love became the very fabric of the talks and writings of Paul.

'Though I speak with tongues of men and of angels and have not love! ... I am nothing,' he wrote.

He spoke untiringly about God's love for his children, the human race:

Tor I am persuaded that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers ... shall be able to separate us from the love of God'—nor from our birthright as 'heirs of God, and joint heirs with Christ'.

And just as untiringly he repeated Jesus's teachings that we should never do harm to anyone, not even to our bitterest enemies:

'Bless them which persecute you: bless, and curse not ... if thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink. ... Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good'.

And he established churches with such genius that he transformed Christianity from a hope and a dream into a practical reality—into a great, organised religion. More important, he established it as a religion not just for one race of people but for all races—a truly 'catholic' religion.

But of course he did not do this unopposed. As the greatest of the Christian leaders, he was also one of the most persecuted. He was imprisoned, starved, beaten, stoned, and again and again he narrowly escaped death, until finally in A.D. 65, in a frightful massacre of Christians in Rome, he and the great apostle Simon Peter were both brutally executed. For this, unhappily, was the way in which the human race first welcomed the teachings of Christ:

'A new commandment I give unto you, that you love one another. As I have loved you, so you shall love one another.'

Christians of East and West

About three centuries of continued persecution then passed. But when Constantine, the Roman Emperor, became a converted Christian, the whole story changed. Christianity was now the official religion of the Roman Empire and its followers, at last, were safe from wholesale persecution.

But the moment they were freed from outside enemies, they began disagreeing among themselves. They quarrelled about all sorts of things, mainly about whether Jesus was a man or God Himself. Then, when the sacred writings were translated from Greek into Latin, many meanings were slightly changed, and these slight changes led to huge arguments.

From having been the religion that Jesus taught, for the comfort of the downtrodden, for the uplifting of the humble—a glowing inner faith and hope for the poor, the sorrowful and the sick—Christianity became the religion of the upper classes, a rather gaudy showpiece of high society. And it also became the subject for loud quarrels between the leaders of its churches.

No wonder that many people turned aside from all of this noise and wrangling, in an effort to find peace within themselves. They left their homes in the cities, and all of their belongings except the most humble necessities. They lived alone in the surrounding deserts, and were actually the first of the Christian monks.

Christianity was already a very widespread religion, governed by many bishops; and above the bishops were five church leaders, called Patriarchs, or Popes. Of these, the Popes of Constantinople and of Rome were the most important, and perhaps for this very reason they were unfriendly towards each other.

As Constantinople was now the capital of the Roman Empire, its Pope felt that he should have greater authority than the Pope of Rome. And the Pope of Rome felt that he should have greater authority because Rome had been the scene of so much early Christian history, and so many of the martyrs had met their deaths there.

As the centuries passed, one thing after another seemed to widen the gap between these two sections of the Christian Church—Constantinople in the east and Rome in the west. Finally, in the middle of the eleventh century, after a disagreement about certain doctrines and practices, the Pope of Rome excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople and all of his followers, and the Patriarch retaliated by excommunicating the Pope. 'Excommunication' means that a person is expelled from the church and is no longer allowed to take part in its rites and ceremonies; a very serious thing to do to a Pope or Patriarch!

Then, in the 12th century, the Moslems invaded Jerusalem and conquered it, feeling that it was even more sacred to them than to the Jews or the Christians. This was a great tragedy, because armies of soldiers set out from various Christian countries to win it back again. These were known as the Crusaders.

The first of them were a noble band of men, inspired by high motives. But as the years passed and wave after wave of Crusaders marched across Europe, their motives became mixed, and were often bad rather than good. Many young men joined up just for the thrill and adventure of it, others with the idea of loot, still others because they believed that by becoming Crusaders they would be forgiven any crime or sin. And in the long run, they behaved so badly that history has scarcely a good word to say for them.

The worst thing they did was to complete the break between east and west, apparently beyond repair. They swooped down upon their fellow Christians in Constantinople, demanding to be housed and fed by them, trying to crush the authority of their Church under the heel of Rome, and in general treating them with such contempt that it seemed as if their real aim must have been to overthrow the Christians of the east rather than the Moslems.

Bitterness led to more bitterness, and the passing centuries brought no relief. The Christian Church in the east—now known as the Eastern Orthodox—had always been a power under the State, certainly not over it or equal to it—and so it has remained to the present day. That of the west, however, with its centre at Rome, gradually became a great political power which ruled over emperors as well as over the common people.

Certainly this position was not relished by kings and nobles, who wished to hold absolute control over material matters. But the Church argued that the things of the spirit must, by their very nature, be more powerful than those of the body. In 1077, Pope Gregory VII excommunicated King Henry IV of Germany and the king, begging to be taken back again into the Church, was kept waiting barefooted in the snow for three days before the Pope would listen to him. So now, it seemed that there could be no further argument about which held the greater power. Yet the argument did continue, together with many other troubles, embittering the passing years.

The picture was not completely dark, however, for about that time—in the 12th and 13th centuries—lived Francis of Assisi, one of the greatest of all Christian saints, the friend of everything in God's creation, no matter how grand or small, beautiful or ugly, healthy or diseased. There were great numbers of people who followed him in his wonderful way of life, and these—called the Franciscan Friars—became known everywhere for their goodness and charity. Yet at the same time terrible things were happening in the 'Christian' world.

The strange thing about evil is that it can sometimes come about when people are most strongly upholding righteousness. This, in a way, explains the Inquisition— one of the most feared and hated names in history. It began in the 13th century, and lasted for about 200 years. It acted as a kind of court, inquiring into the lives and thoughts of anyone suspected of heresy (views about Christianity different from those of the 'official' Church) and those whom it found guilty, it usually tortured to death.

It condemned all who were not Christians, and any Christian who criticised the Church, or the infallibility of the Pope. Of course, this 'infallibility', or perfection, did not refer to the Pope as a man, but to the idea that he stood for—the idea of Christianity itself, taught by Jesus, and first organised into a Church by Simon Peter. When confusion arose, and the man himself was thought of as infallible, it was only natural for many people to object, because at that time, there were some very bad Popes indeed.

No doubt, when the officers of the Inquisition ordered such people to be tortured and killed, they felt sure that they were stamping out evil. But also, in their zeal, they were forgetting the words of Jesus himself—'Neither do I condemn thee'.

In the earliest days, the followers of Christianity were martyrised by the Romans and Pharisees. Now, they were martyrising one another. However, those who lost their lives did not lose them in vain, for nothing speaks louder than the blood of martyrs, and at last, towards the beginning of the 16th century, changes began to take place throughout the Christian world.

The Coming of Protestantism

In England, Christianity had been known from the early centuries. But in A.D. 597 a branch of the Roman Catholic Church was established there by Augustine, acting on the instructions of the Pope. A few centuries later, a stirring of unrest began to be felt in the English Church, whose leaders could not see why they must always look to Rome for leadership. In the early part of the 16th century, they broke away altogether. The beliefs and rituals of the English Church remained the same as those of the Roman Catholic one, but it declared itself independent of Rome— the Church of England.

Then, here and there in other countries as well, there arose whole groups of people openly protesting against the way in which the Church at that time was acting—just as if Christ had never walked the Earth, preaching love, humility, forgiveness, and the giving-over of worldly goods.

A wealthy man in France, called Peter Waldo, gave all of his own riches away to the poor, and dedicated himself to living as well as preaching the words of Jesus. And, even in spite of cruel persecutions, a great many people became his followers.

John Wyclif, in England, also objected strongly to certain Church practices. He wanted the services to be read in English instead of in Latin, so that even uneducated people could understand them. And he strongly denied the infallibility of the Pope.

On the last day of October in 1517, a history-making event took place. A German monk by the name of Martin Luther nailed a long sheet of writing to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. First, a small number of people stopped to read it in passing; then more and more of them came in a steadily swelling stream, and the practice of Christianity was never quite the same again.

On that sheet of paper, Martin Luther had written a bitter protest against the 'un-Christianly' actions of the Church in those days, including one known as the sale of indulgences. This began, and lasted for a time, in the 16th century. It started with the worthy practice of giving money to the Church, but it led to the unfortunate belief that these gifts of money would compensate for any wrong that the giver might have done, and Luther just would not agree that the favour of God could be bought.

There were many people inside the Church itself who realised that the time for big changes had come, in this and in many other ways, but Luther's drastic actions angered them. The Pope ruled that he was no longer a monk of the Christian Church, and forbade all Christians from reading any of his works.

When a copy of this order was sent to Luther himself, he defiantly burned it in public. For the rest of his life, he wrote and preached continuously against the Roman Church. He translated the Bible into German, and he organised many churches which, though Christian, had no contacts with Rome. These churches were made up of thousands of people who, like Luther, Waldo and Wyclif, 'protested' against Roman practices. So it was that Protestantism began.

Just when Martin Luther was nailing his famous protest on the door of a church in Germany, there was an eight-year-old boy in France called John Calvin—a very bright boy for whom everyone predicted a most promising future. Of course no one, at that time, could have guessed that his name would some day be among the greatest in the Protestant movement. Yet only 18 years later, he had already written a book called Institutes of the Christian Religion, which established him as a true leader in that movement. Fortunately for him, he went to Switzerland to write it, since in the France of those days people were burnt at the stake for being Protestants.

His teachings (called Calvinism) spread rapidly throughout Europe, and even became the basis of Presbyterianism in Scotland. John Knox, the great Scottish Protestant who later founded that religion, met Calvin in Switzerland and accepted many Calvinistic ideas among his own.

But although Protestantism began in a blaze of righteousness, it did not continue in the same way. A Swiss by the name of Ulrich Zwingli fought ardently for many years to separate the Church from the State, making it a purely spiritual power without political interests. He also insisted that all statues should be removed from Christian churches, since people tended to worship them as idols, and he had many other ideas which were so extreme that even Luther could not accept them, so that when these two great Protestants met, they quarrelled violently.

Also in Switzerland, a group of people known as the Anabaptists had arisen, with many ideas of their own, especially regarding baptism. They believed that people should be baptised when they were adults and could understand the meaning of this event, not when they were newborn babies. There were many followers for this movement, which finally gave rise to the Baptists, Quakers and Congregationalists. But they were persecuted so savagely by the other Protestants that even the Catholic Inquisition could not have treated them more cruelly.

Over 2000 of them were killed within 13 years at the beginning of the 16th century.

And afterwards, the Quakers were hunted down with just as much bitterness, despite the quiet and loving attitudes which led to their being called the Society of Friends.

But over a period of about two centuries, the ferocity of religious persecutions and wars seemed to have spent itself, so that Methodism came into being fairly peacefully toward the middle of the 18th century, under the leadership of John Wesley.

Christianity Today

Today, over 2000 years after the birth of Jesus, enormous strides are being made at last toward the true practice of Christianity—toward understanding and love. Just after the middle of this century, Pope John opened his arms to all Christian churches, whether Eastern or Protestant, and to all mankind, whether black or white, rich or poor. And in a great work called Pacem in Terns (Peace on Earth) he put into writing a step-by-step, practical approach to a vision of world peace.

Following him, Pope Paul broke with tradition by moving out into the world in person, far and wide.

His friendly meeting with the Archbishop of Canterbury—in 1966, over-watched by Michelangelo's inspired paintings in the Sistine Chapel—helped to melt away the hatreds of centuries. And his expressions of deep respect toward great religions other than Christianity will, it is to be hoped, become a pattern for all time.

Meanwhile, the Protestants also are working toward Church unity through what is known as the World Council of Churches. The idea is that all of the Protestant religions—and also, now, many of the Orthodox churches—should set aside their differences of opinion and work together for the good of the world—feeding the poor, sheltering the homeless, helping refugees, furthering education.

It may not seem too difficult for the various Protestant churches to work together, but for Catholic and Protestant ones to unite in any way has always appeared impossible. Now, however, even that is gradually taking place, to the extent that, in recent years, the heads of many Protestant churches (Lutheran, Presbyterian, Anglican, Methodist) have travelled to Rome and met with the Pope, not as strangers, but as fellow Christians.

In the world and in the human heart today, things are happening which have never happened before. In the past, one or two separate people here and there may have realised the good in other people's religions, and dreamt— without really hoping—of a time when barriers would be broken down and mankind would unite as the one affectionate family. Certainly not a family all thinking in exactly the same way, but respecting one another's different outlooks and loving one another no less because of them. Today, not mere individuals, but whole great organisations are dreaming the same thing, and seeing some hope of the dream coming true. And when it does come true, it will bring with it the wonderful blessing of world peace.