Sacred Texts Taoism Index Previous Next

13. 1. Favour and disgrace would seem equally to be feared; honour and great calamity, to be regarded as personal conditions (of the same kind).

2. What is meant by speaking thus of favour and disgrace? Disgrace is being in a low position (after the enjoyment of favour). The getting that (favour) leads to the apprehension (of losing it), and the losing it leads to the fear of (still greater calamity):--this is what is meant by saying that favour and disgrace would seem equally to be feared.

And what is meant by saying that honour and great calamity are to be (similarly) regarded as personal conditions? What makes me liable to great calamity is my having the body (which I call myself); if I had not the body, what great calamity could come to me?

3. Therefore he who would administer the kingdom, honouring it as he honours his own person, may be employed to govern it, and he who would administer it with the love which he bears to his own person may be entrusted with it.

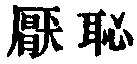

, 'Loathing Shame.' The chapter is difficult to construe, and some disciples of Kû Hsî had to ask him to explain it as in the case of ch. 10. His remarks on it are not to my mind satisfactory. Its object seems to be to show that the cultivation of the person according to the Tâo, is the best qualification for the highest offices, even for the government of the world. Par. 3 is found in Kwang-dze (XI, 18 b) in a connexion which suggests this view of the chapter. It may be observed, however, that in him the position of the verbal characters in the two clauses

, 'Loathing Shame.' The chapter is difficult to construe, and some disciples of Kû Hsî had to ask him to explain it as in the case of ch. 10. His remarks on it are not to my mind satisfactory. Its object seems to be to show that the cultivation of the person according to the Tâo, is the best qualification for the highest offices, even for the government of the world. Par. 3 is found in Kwang-dze (XI, 18 b) in a connexion which suggests this view of the chapter. It may be observed, however, that in him the position of the verbal characters in the two clauses

of the paragraph is the reverse of that in the text of Ho-shang Kung, so that we can hardly accept the distinction of meaning of the two characters given in his commentary, but must take them as synonyms. Professor Gabelentz gives the following version of Kwang-dze: 'Darum, gebraucht er seine Person achtsam in der Verwaltung des Reiches, so mag man ihm die Reichsgewalt anvertrauen; . . . liebend (schonend) . . . übertragen.'