*Goethe, Faust.

We awake each day to a gender specific world; our behavior, clothes, and language all have a sexual orientation to which we must be sensitive. Being both products and proponents of our culture, the more aware we are of the underlying forces and compulsions, the less we are at their mercy. In determining whether the "sexing" of everything is more than just an ephemeral cultural phenomenon, we can look to universal principles which seem to express themselves as masculine and feminine energies.

Examining the feminine separate from the masculine is a little like trying to understand only one of the colors of the rainbow -- how can we know a single hue except in relation to its sibling shades? As H. P. Blavatsky said, "Are not the prismatic rays fundamentally one single white ray? From the one they become three; from the three, seven; from which seven primaries they fall into infinitude" (Secret Doctrine Commentary 1:23). Just as the reds and blues of the rainbow don't really hint at the purity of white light from which they spring, so too masculine and feminine polarities only dimly suggest the wholeness which is their source. Some say spirit is masculine and matter feminine. Some consider the holy spirit to be feminine. Whatever the feminine principle is, it is an essential and equal partner, not a deficient masculine principle.

Traditionally spirit or logos is seen as a masculine principle, while the feminine is associated with earth, matter, mother, and the form side of life. It is easy to mistakenly equate spirit with the invisible and matter with the visible realms, but spirit and substance exist on all planes, so that matter has an immense range of gradations in the visible and invisible spheres.

Perhaps we can imagine a time of wholeness when there was no duality, no feminine or masculine energies; a time before time, before the heavens and the worlds; a time that was and was not, in a space that was and was not -- containing everything as well as nothing. When the time was ripe for the birth of the universe, it is said that there was activity on inner invisible planes (that is not so difficult to imagine since much of our activity takes place on invisible planes: our feelings and beliefs, memories, thoughts, and dreams). From this mysterious unknown origin sparked a complex chaos, a multifaceted Oneness. Infinitely diverse, yet each united to the whole in the way our fingers are, parted, distinct, yet together on one hand -- like many stars in one sky, thoughts in one mind.

And just as human intelligence thinks and reflects on human planes, cosmic intelligence was said to be at work on cosmic planes. The Bible pictures this as the earth being without form and void. The Tibetans describe it as the Void which embraces all things; the Hopi call it Tokpela, Endless Space. We will call it Wholeness, and everything -- spirit and matter, masculine and feminine principles, you and I -- were and are part of it.

Diversity flows out from the one reality magically and in an orderly way, the way leaves do from a branch. What is within expresses without, in the way a vague idea grows gradually more defined and gives birth to a well-formed thought or series of concepts. Or as a film negative develops slowly in its chemical bath till a clearly defined image evolves. Or as a single seed nourished by sun and moon, water and earth, progressively grows the male and female aspects it requires to reproduce itself, the feminine growing simultaneously with the masculine principle. Diversity begins as duality.

The Chinese yin-yang symbol portraying the negative or feminine (yin) and the positive or masculine (yang) which proceeded from the One, the Tao, illustrates this dual but unified oneness. (1) Duality within wholeness is not an optional pairing like salt and pepper or ham and eggs, but an interdependent relationship where one cannot exist without the other. Like the coupling of oxygen and hydrogen to make water, one isn't more or less essential than the other. But though both are essential, inseparable, and rooted in the same source, they are different.

Commonly the masculine principle is said to be related to action, spirit, light, and energy. But it cannot act in the abstract; it must have a vehicle of substance and form; and the vehicle must fit the function, no matter how subtle or invisible. So wherever the masculine expresses itself, it can only do so through the feminine.

On cosmic planes, The Secret Doctrine presents the waters of space as feminine, and the akasa, the aethers, and astral regions as all having their feminine aspects. The upper aether is called the Celestial Virgin, the immaculate mother who, after being fertilized by Divine Spirit, brings matter and life into existence. The feminine -- vessel of birth and rebirth, and existing on all planes -- can passively or actively foster transformation. If there is no form, if the divine is not embodied, there is no love or compassion, for only in a body can the highest wisdom have any effect in the manifested worlds. Compassion needs form, and the virgin birth, once thought to be a singular event, may be seen to be a continual compassionate process.

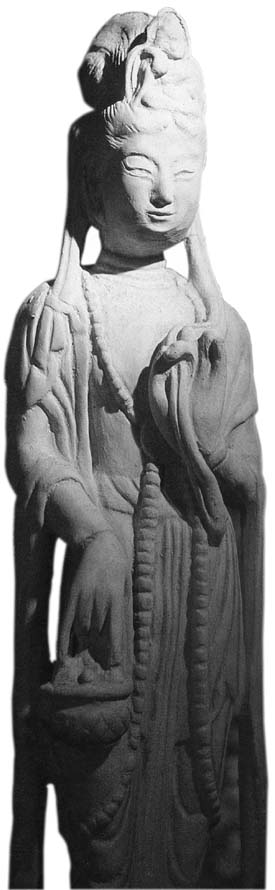

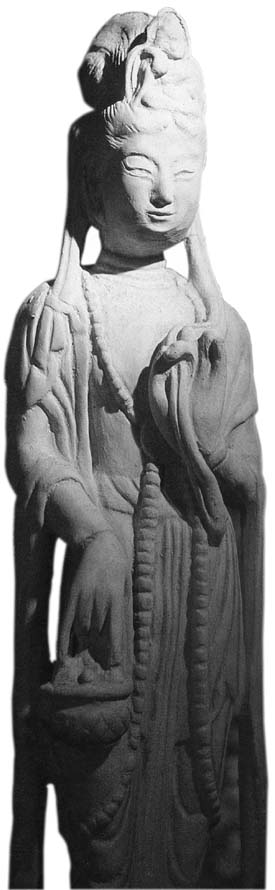

The celestial energy patterns were grounded in antiquity through symbols. Secret wisdom was often represented by a female form while the male figure stood for the unknowable mystery. This secret wisdom, also known as the Female Soul, was called Sophia by the Gnostics, Sephirah by the Jews, Sarasvati by the Hindu, and the Holy Ghost by early Christians. They were vessels of truth, of divinity, high wisdom embodied. And here is the connection to matter: not matter in a physical sense, but in the sense of having substance, a body; something that exists in time and space. Giving birth to form is said to be the task of the feminine principle, and when we give birth to anything, a child, a painting, a feeling, we make tangible and sensible something that has previously been imperceptible.

Everything we see is made of substance, and everything we can imagine is a vessel for something more refined, more spiritual, which, like nesting dolls, reveals yet another vehicle for something even more subtle. Everything is a soul and has a soul; and just as souls are sacred vessels of secret wisdom, so too is mind.

The mind is generally considered masculine because of its active creative aspects, but in The Voice of the Silence, Blavatsky refers to the human ego both as "manas" or "mental discrimination" (p. 74) and as "she" and "her" (pp. 3-4), a paradox without the key to interpretation. Once we have thought something, we have in a sense materialized it. The mental impulse is masculine, but as a receptacle mind is feminine; as soon as thought (masculine) takes shape, it exists in a world of time and the feminine principle. The contents of mind, our thoughts and dreams, are thus feminine vessels containing seeds of even more subtle thoughts.

Not only does the masculine, upon closer examination, include the feminine and vice versa, but the relationship undergoes a recurring series of metamorphoses. Blavatsky explained the rhythmic interblending of primal forces this way, using atma as the divine, buddhi for spirit, and manas for mind:

It is curious and interesting to remark in the ancient cosmogonies, especially in the Egyptian and the Indian, how perplexing and intricate are the relationships of the Gods and Goddesses. The same Goddess is mother, sister, daughter and wife to a God. This most puzzling allegory is no freak of the imagination, but an effort to explain in allegorical language the relation of the "principles," or, rather, the various aspects of the one "principle." Thus we may say that Buddhi (the vehicle of Atma) is its wife, and the mother, daughter, and sister of the Higher Manas, or rather Manas in its connection with Buddhi, which is for convenience called the Higher Manas. Without Buddhi, Manas would be no better than animal instinct, therefore she is its mother; and she is its daughter, child or progeny, because without the conception which is only possible through Manas, Buddhi, the Spiritual Power, or Sakti, would be inconceivable and unknowable. -- Collected Writings 11:501-2

This, then, explains how the Kabbalists understand Shekinah to be wife, daughter, and mother of the heavenly man, Adam Kadmon, or in the Egyptian pantheon, how Isis is considered both mother and spouse of Osiris.

Cycling downwards into more mundane affairs, from warring to healing, writing to singing, from queen of the crossroads to queen of the sea, spinning and weaving, birthing and cooking -- embracing all the human arenas from death, fate, and magic to agriculture and rainmaking -- anciently, feminine deities ruled. Throughout the history of the earth there is virtually no aspect of life that was not given over to the feminine principle, including being Mother of God (as were the Christian Mary, the Canaanite Astarte, Egyptian Isis, and Hindu Deva- ki). There is overwhelming anthropological evidence of worldwide worship of feminine deities; according to the Encyclopedia of Religion, "The emergence of virtually every major civilization was associated in some way with goddess worship."

We are used to images of the feminine as they connect with earth (Mother Nature, Mother of the World, or Earth Mother), but are less familiar with feminine deities who also rule the sun and heavens. The Japanese emperor was thought to be a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu, who was also known as Heaven Shining She, the Great Woman Who Possesses Noon, and Shining Buddha of Heaven. In Mesopotamia, Ishtar-Inanna was revered as Queen of Heaven. Devotees of Mighty Anat, Lady of northern Canaan (1400 BC), sang about "Her power in battle . . . , still She was called upon as Mistress of the Lofty Heavens; Ruler of Dominion; Controller of Royalty; Virgin, yet Progenitor of People; Mother of All Nations; Sovereign of All Deities" (Merlin Stone, Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood, 1984, pp. 120-1) and more. Modern popes have called their Mother Mary the Queen of the Universe, Queen of Heaven, Seat of Wisdom, and even the Spouse of the Holy Spirit.

Understanding the rhythmic flow of primordial energies, we can see how this came to be. Many cosmologies tell of a time before death entered the world, where there was a kind of eternal life, a Golden Age when an androgynous humanity was virtually mindless. Then self-reflective consciousness stirred awake, death entered, and the sexes separated. What was One in the dreamtime became two, but the price was death. Prior to this there had been no seasons, timelessness reigned. But after this, time asserted itself and began cycling; awakening moved to flowering, decline, and death; then an incubation followed by a new awakening and fufillment, followed by a new death.

The monthly death of the moon gave rise to comparisons with earthly death. The ancients noticed women's menstrual cycles being closely aligned to the phases of the moon, and soon other characteristics were said to be shared -- inconstancy, shapeshifting, mystery, secrets. Deities who reigned on the moon, also ruled the earth. While Westerners see a man in the moon, for Chinese, Arabians and others, the earth goddess was also moon goddess. From this duality arose threeness.

Feminine deities arose who had three faces or three aspects, just as there were three moon phases: dark, full, crescent. Sin, an early Babylonian moon god, "was triune and the moon goddess who replaced him, was represented by the Three Holy Virgins." (2) Hecate Triformis had three natures; a statue (Hecaterion of Marienbad) showing her as a threefold woman recognizes her power in heaven, on earth, and below. In addition to the three Norse norns and three Greek fates, there are the three Russian Zoryas, keepers of dawn, day, and night. Among the Celts, the Morrigan was called the Holy Trinity, which embodied not only the Moon waxing, but full, and waning; the Daughter, Mother, and Grandmother; warrior, young woman, and mighty Queen.

So we see again the movement of the One finding expression first as Duality, which produces the Three, and from the Three, infinity. This threeness connects to the natural rhythms of life, the cycles of manifested universal energies. The three aspects of the moon, or of the deities or of anything, can remind us that each event has a past, present, and future. Oneness seems to work on the invisible planes --we can be of one heart and one mind -- but on the visible planes we must embody duality. It is dangerous to try to separate wholeness into only feminine or only masculine, as this seeks to stop the cycle of eternal becoming. Whenever we attach ourselves to only one aspect, the unacknowledged half reasserts itself. No matter how often we try to isolate the south from the north pole by cutting a magnet in two, wholeness, bipolarity, reestablishes itself. We never meet one without the other. In the Kabbalah Sephirah (divine intelligence) is female, but when she begins to act like a creator she becomes male. This eternal coupling is even depicted in the human body which has both gender characteristics (one dominant and one recessive) suggesting that being rooted in both we can act creatively from both.

Reconnecting with our inner wholeness allows us to grow, but we must renew this daily. Someone once asked, "I have an idea what it means to be a child of God. What does it mean to be an adult of God?" Maturing, learning to be "an adult of God," is the ongoing process that takes us from Wholeness to duality, and from the two to three, and back again. And while the masculine and feminine eternally express themselves, we don't have to choose one or the other, but can take our cues from the recurring cycles that move through us as outer and inner events.

Worldwide, expectant parents make life and death decisions based on gender-revealing sonograms and other tests; globally we are so captivated by sexuality we rarely ask what it serves. Contemplating the feminine principle, we are reminded that the divine cannot embody on any plane without structure and form; love needs a way to express itself, and we each have it within us to be the means for that expression.

Everyone is master of his own wisdom -- says a Tibetan proverb and he is at liberty either to honour or degrade his slave. -- KH, The Mahatma Letters, p. 138

FOOTNOTES:

1. "Tao produced the One, the One produced the Two, the Two produced the Three, and the Three produced the ten thousand things" (Liu Xiaogan quoting Lao Tzu, Our Religions, p. 241). (return to text)

2. M. Esther Harding, Woman's Mysteries Ancient and Modern, 1976, p. 218. (return to text)