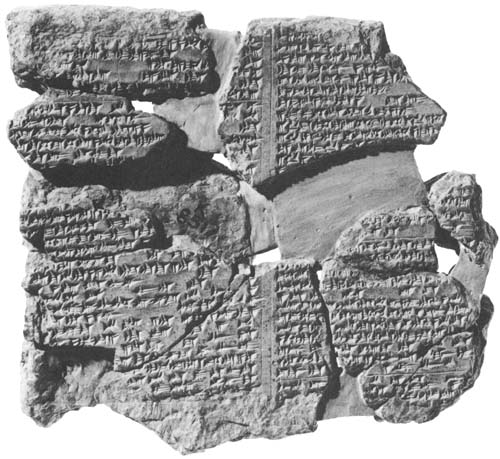

The Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest and most moving stories rooted in the ancient wisdom-tradition of mankind. Recited for nearly three millennia, it was virtually lost for another two with the advent of Christianity. Modern generations came to know about Gilgamesh only after the first cuneiform fragments of his story were excavated in 1853 at Nineveh from the library of the last great Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, who reigned in the 7th century BC. Almost twenty years elapsed, however, before the clay tablets were deciphered by George Smith at the British Museum. On December 3, 1872, he announced to the newly-formed Society of Biblical Archaeology that he had "discovered among the Assyrian tablets . . . an account of the Flood" in one of the story's later episodes. This stirred up considerable interest and, before long, more fragments of Gilgamesh were unearthed, both at Nineveh and in the ruins of other ancient cities.

After nearly one hundred fifty years of archaeology and patient scholarship, the general consensus is that the 7th-century tablets, written in the Semitic Akkadian language, are a copy of a 12-tablet "Standard Version" dating back to about 1200 BC, composed by a Babylonian priest named Sin-leqi-unninni. This version in turn is a conflation and revision of earlier Babylonian traditions, themselves rooted in a number of Sumerian stories written centuries earlier in the third millennium. Since neither the Sumerians nor Babylonians wrote history in the modern sense, exact dating is difficult, nor do we know with certainty when and where the epic version actually originated.

From the Sumerian King List, we do know there was an historical Gilgamesh -- in Sumerian spelled gis-bil-ga-mes, conjectured to mean "the (divine) old one is youthful" (1): a name probably given at an initiation or coronation rite, symbolic of spiritual rebirth and divine kingship. He reigned sometime between 3000 and 2500 BC in the city-state of Uruk near the Euphrates in what is now southern Iraq. According to the Babylonian epic, Gilgamesh himself inscribed his story on a stone tablet. It had widespread and long-lasting appeal, for versions have been found all over the Mesopotamian region, and as far north in Asia Minor as the Hittite capital of Hattusha (Bogazkoy). This is fortunate because modern translations of Gilgamesh have literally been pieced together from widely-scattered fragments. There is no single complete rendition of the Standard Version extant, and what we do have comprises variant Sumerian, Hittite, and Akkadian streams.

Fragment of Gilgamesh Tablet 11 (British Museum)

Nevertheless, while story details often differ, Gilgamesh reflects much of the Sumerian world view as well as that of the Babylonians and Assyrians, who first conquered the Sumerians and then assimilated their culture. Like all epics, Gilgamesh contains both historical and mythic elements in all its versions, and thus is meant to be interpreted on several levels. In addition to its very human themes of friendship, courage, the problem of death, and the meaning of life, it is also an initiatory tale about the quest for enlightenment, the revelation of divine mysteries, the duality of man, and the evolutionary unfoldment of our spiritual nature. Implicit in the narrative are the cosmology and other metaphysical doctrines of the ancient sanctuaries. Even the physical composition of the Babylonian recension discloses an intentional number symbolism: 12 tablets, each containing about 300 lines divided into 6 columns. More importantly, Gilgamesh is meant to be read as an extended metaphor, a spiritual biography as much about ourselves as about the Sumerian hero-king. Calling across nearly 5,000 years, it is a potent reminder of the timelessness and relevance of the ancient spiritual path.

Gilgamesh is a human story and it begins with his beginnings, not with the story of cosmic genesis, which nevertheless underpins the tale. Although no Sumerian theogony or creation story has yet been found, one has been provisionally reconstructed. (2) Briefly, the gods and goddesses unfold from the nameless divine mystery as follows: in the beginning there was An (Babylonian Anu), first-born of the primeval sea, i.e., waters of Space. He is forefather of the gods and ruler of the heaven beyond the heavens. Like the Greek Ouranos he was united to Earth (Ki) and begot Enlil, Lord of Air, the breath and word and "spirit of the heart of Anu." Enlil begot the Moon, Nanna/Suen (Babylonian Sin), and Nanna in turn begot two of the most important deities in Gilgamesh: Utu (Shamash), the Sun, omniscient god of Justice; and Inanna (Ishtar-Venus), Queen of Heaven, goddess of Love and Strife. Other major characters include Enki (Ea), another "son of Anu," Lord of Earth and the watery Abyss, also Lord of Wisdom and a co-creator and benefactor of humanity; and Aruru ("seed-loosener"), sister of Enlil and goddess of creation ("lady of the silence").

The divine world was intimately linked with humanity. The Sumerian King List records eight divine kings who had reigned for a period of 241,200 years after "the kingship was lowered from heaven." Then the Flood swept over the five cities of their rulership. After the Flood, the kingship was once again lowered from heaven and our hero reigned as Uruk's fourth or fifth sovereign.

This three-part series of articles presents an abridged version and interpretation of Gilgamesh, based on the Babylonian recension and supplemented by the older traditions. To preserve the atmosphere of the story, the wording follows the terse but richly symbolic text as closely as possible. (3)

Gilgamesh was "the one who saw the abyss. He was wise and knew everything; Gilgamesh, who saw secret things, opened the hidden place(s) and carried back a tale of the time before the Flood -- he traveled the road, he was weary, worn out with labor, and, returning, engraved the story on stone."

When the gods created Gilgamesh, the Great Goddess (Aruru) designed the image of his body; heavenly Shamash, god of the Sun, endowed him with beauty, while Adad, god of the Storm, granted him courage. His form was surpassing: eleven cubits his height, nine spans the breadth of his chest. "Two-thirds of him was divine, one-third human" -- Gilgamesh is essentially spiritual, but not yet fully divinized. (4)

We first meet mighty Gilgamesh as Uruk's young and unruly king, known chiefly for having built the walls of that city and its inner sanctuary, the temple of Anu and Ishtar. The walls were made of oven-fired brick resting on foundations laid by the seven sages, antediluvian kings who had taught humanity the arts of civilization. Secured by its seven-bolted gate, Uruk is described as triform, being comprised of 1) the city proper, 2) the orchards, and 3) the claypits, corresponding to spirit, soul, and body. Cities of divine kingship, moreover, were conceptualized by the ancient Mesopotamians as earthly reflections of preexisting heavenly models inhabited and ruled by the gods. The cosmos is a polity: as above, so below.

Child and hero of Uruk, Gilgamesh was famous, powerful, taking the forefront as a leader should, still walking in the rear bearing his brothers' trust. Yet no one inside or outside the city could withstand the passionate strength of their young protector. The men of Uruk fumed in their houses: "Gilgamesh leaves no son to his father; his lust leaves no bride to her groom; yet he is the shepherd of the city, strong, handsome, and wise." The great god Anu heard their lamentation and called to the mother of creation: "You, Aruru, who created humanity, create now a second image of Gilgamesh: may the image be equal to the impetuosity of his heart. Let the two of them strive with one another, that Uruk may have peace."

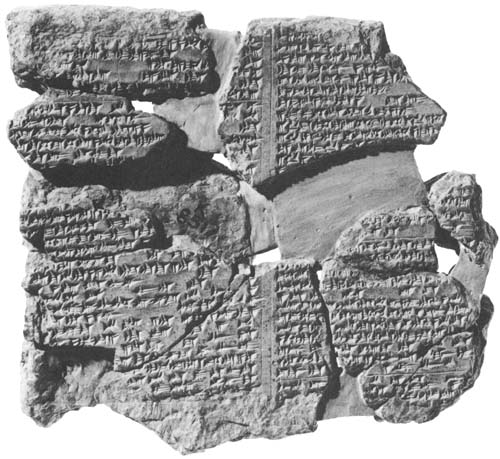

Gilgamesh, 8th Century BC, Palace of Sargon II, Khorsabad

Gilgamesh, 8th Century BC, Palace of Sargon II, Khorsabad

Hearing this, Aruru formed an image of Anu in her heart. She washed her hands, pinched off clay, and threw it into the wilderness. Valiant Enkidu she created, a warrior like the war god Ninurta. His whole body was thickly covered with hair, his head covered with the long hair of a woman. He knew neither people nor a homeland; he was clothed in the clothing of Sumuqan, the god of cattle and beasts. He ran with the gazelles on the grass; with the wild animals he drank at the waterholes. This was primordial man -- as the text has it, "man-as-he-was-in-the-beginning" -- representing the earliest human races before mind and self-consciousness were awakened.

One day a stalker, a hunter, met Enkidu face to face at a waterhole. Benumbed with fear, the trapper retreated to his house and spoke to his father about the powerful man in the hills who fills up the pits, tears out the traps, and allows the beasts to slip through his hands. The father counseled his son to go to Gilgamesh in Uruk. "Ask him to give you a temple courtesan, so that the wild man may be subdued by a woman's power. When next he comes down to drink at the watering place he will embrace her, and then the wild beasts will reject him." And so it came to pass -- six days and seven nights, joined with the courtesan. When sated by her charms, Enkidu set his face toward his animals; but they scattered, wheeling away. Enkidu tried to run after them, but his knees failed. He grew weak; he could not run as before, "yet he now had knowledge and wider mind."

Enkidu turned to the courtesan. She spoke; and as she spoke, he heard (with awareness and understanding): "You have become beautiful, like a god, Enkidu. Let me therefore lead you to the heart of Uruk, to the temple of Anu and Ishtar, where Gilgamesh is." Enkidu agreed, though he boasted that he would cry out in Uruk that he alone is powerful; that he is the one who changes fates. The courtesan cautioned him that Gilgamesh is the stronger, he is "the joy-woe man, . . . ceaselessly active day and night."

And so she advised Enkidu to make himself "an enemy to his anger," to temper his arrogance: "For the god of Justice, Shamash the Sun, loves Gilgamesh; Anu, Enlil, and Enki have widened his mind, so that even before you come from the mountain, Enkidu, Gilgamesh will have seen you in dreams."

Gilgamesh had two dreams, first of a shooting star which fell on him -- so heavy he could not lift nor move it. The land of Uruk encompassed it. The people gathered about it, and Gilgamesh embraced it like a wife. In the second dream Gilgamesh saw an axe fall over the assembly of Uruk, and he hugged it as if it were his wife, too. Puzzled as to their meaning, he went to his mother, the wise goddess Ninsun, who "untied the dreams." She told him that both the star of heaven and the axe were his companion who was coming. "This companion is powerful, has awesome strength, and is able to save a friend" -- nevertheless, she adds mysteriously, "He is the one who will [abandon/rescue] you" (the tablet is broken here and may be read either way).

Back in the mountain wilderness, at the same moment that Ninsun is enlightening Gilgamesh, the courtesan does the same for Enkidu: "When I look at you, you have become like a god. Why do you yearn to run wild again with the beasts in the hills? Get up from the ground, up from the bed of a shepherd." The advice of the woman came into Enkidu's heart. She divided her clothing and covered him, and kept the other part for herself (an allusion to the separation of the sexes). She brought him to a shepherd's house and taught him to eat cooked food, including bread, which he had not known. He drank wine, seven goblets, which made his mind loose and his heart light (intoxicated by material life). He rubbed his hairy body and anointed himself with oil. Enkidu had become a man. He put on a garment and appeared like a bridegroom. He seized weapons to hunt lions. Shepherds could now lie down, for Enkidu would guard them -- a hero like no one else.

Just as Uruk is the earthly reflection of its heavenly archetype, Enkidu, sometimes called Gilgamesh's second self, is portrayed here as a reverse image or physical counterpart of Gilgamesh: the human-animal vehicle of spirit, soul, and higher mind. His name, moreover, implies a special relation with Enki, Lord of Earth and Wisdom, and may be translated "Enki's knees" or "Enki's creation." Note also Enkidu's transformation and evolution from an asexual, unselfconscious protohuman formed in the image of Anu to hermaphrodite ("joined with the courtesan"), followed by separation, final physicalization, and the awakening of understanding or self-conscious mind through "love" -- in the Platonic sense of Eros (cf. Symposium, Diotima's speech, §§202-4).

The story resumes with a traveler on his way to Uruk who informs Enkidu of Gilgamesh's lustful ways: there is to be a wedding and the king will take "first rights" -- he goes first, the husband after. Enkidu's face grew pale and he hastened to the holy city. There the people gathered about him, saying to each other, "He looks just like Gilgamesh -- but he is shorter, and stronger of bone. Now Gilgamesh has met his match."

In Uruk a bridal bed was made. The bride waited for the bridegroom, but in the night Gilgamesh got up and came to the house. Enkidu blocked the way. He put out his foot and prevented Gilgamesh from entering the house. They grappled, holding each other like bulls. They broke the doorposts and the walls shook. Gilgamesh bent his knees and planted his foot in the ground. The fury suddenly died and Enkidu addressed Gilgamesh: "There is not another like you in the world . . . Enlil has given you the kingship, for your head is elevated above all other men." Enkidu and Gilgamesh embraced and their friendship was sealed.

The language of Gilgamesh, from his prophetic dreams ("I loved [Enkidu] and embraced [him] as a wife") to the bridal bed in Uruk -- Enkidu's in retrospect -- clearly refers to a "sacred marriage": the spiritual union or blending of the inner and outer man. None of the extant material names a victor, but the Old Babylonian story given above suggests that the initial strife or "wrestling" is brought to an abrupt end by mutual recognition: Gilgamesh "bent his knees" (to Enkidu's stature) and "planted his foot in the ground." Both phrases are apparent wordplays on Enkidu's name, indicating a successful (or "victorious") bonding and assimilation. Enkidu's subsequent acknowledgment and friendly embrace with Gilgamesh confirm their acceptance of the relationship.

Up to this point the story has been prologue -- an allegory about the evolution and creation both of mankind and of a truly human individual. >From here on Gilgamesh and Enkidu go as one, faithful to each other until death. In the Sumerian stories, Enkidu remains the servant of Gilgamesh; in the Babylonian version, Gilgamesh's mother adopts Enkidu -- he becomes not only the servant, companion, and friend of Gilgamesh, but also his younger "brother." Viewed as a single composite character, Gilgamesh-Enkidu represents the conjoining of heaven and earth, of spirit, soul(s), and body, in a full sevenfold partnership (5) necessary for one to succeed in the hero's quest.

Once he has "fallen" in with his earthly companion, Enkidu, we see a more human side of Gilgamesh. As one of the oldest recorded versions of the Fall motif, both of angels and men, the story is perhaps closer to the original wisdom-doctrine than our customary interpretations. Absent is the sense of evil imputed by later theologians. There seems to be instead a beneficent necessity to this mixing of high and low, of spiritual and physical elements -- for we must not forget what the wise goddess Ninsun, mother of Gilgamesh, said of Enkidu: "This is a strong companion, able to save a friend."

Yet, as the story resumes, Enkidu bemoans the effects of being citified. "Friend," he said to Gilgamesh, "a cry chokes my throat, my arms are slack, and my strength has turned to weakness." Perhaps wishing to save his friend in turn, Gilgamesh proposed that they journey to the Cedar Forest to conquer its guardian, the ferocious god-giant Humbaba, cloaked or armored with his seven terrifying halos. Enkidu hesitated, replying that it will be no equal match: "Humbaba's roar is the Flood, his mouth is fire, and his breath is death. Why do you wish to do this thing?"

Gilgamesh's motives are mixed: besides stirring his friend out of the doldrums, killing Humbaba would drive evil out of the land. But his more immediate interest, prompted by Enkidu's fear of death, gradually centers on another goal. "Who, my friend, can ascend to the heavens? Only the gods dwell forever with Shamash (the Sun). As for humans, their days are numbered, their achievements are but a puff of wind." Nevertheless, even though Humbaba threatens mortal danger, "through the opening of his mouth, the heavens are entered." Toward the Land of the Living Gilgamesh set his mind, determined to "raise a name for himself." Acts of heroism, he believed, will confer a kind of immortality; the tales of his exploits will be remembered by posterity.

Like Enkidu, the counselors of Uruk tried to dissuade the would-be hero: "Gilgamesh, you are young, your courage carries you too far, you cannot know what this enterprise means. Humbaba is not like men who die, no one can stand against his weapons." Gilgamesh was undeterred by their advice or Enkidu's repeated pleas.

At this point the story reveals a deeper motive which Gilgamesh feels but cannot fully comprehend, for he still lacks the maturity and perception to recognize its source. Woven into the Babylonian version of Gilgamesh is a rich thread of astronomical symbolism which here connects Gilgamesh's journey with the twelve-day New Year festival of the Spring Equinox (Akitu), implying initiatory significance. This is confirmed when his mother Ninsun prays to Shamash (man's solar and solarizing principle), asking why he gave Gilgamesh such a restless heart: "Now you push him to go on a long journey to the place of Humbaba, to face a battle he cannot know about, and travel a road he cannot know. . . . May your consort commend him to the watchmen of the night."

After receiving counsel from his mother, Gilgamesh and Enkidu set off (with seven warriors and fifty unmarried men in the Sumerian version) on an arduous journey to Enlil's forest where they plan to destroy its seven-terrored guardian and to fell the Great Cedar. Enkidu led the way, for he knew the road to the forest, had seen Humbaba, and was experienced in battles. He was to protect Gilgamesh and help bring him safely through.

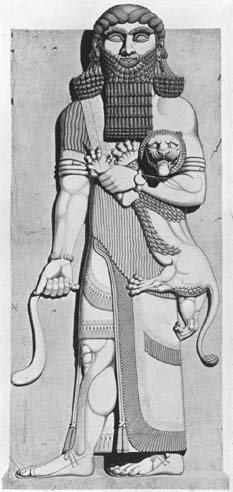

Humbaba, c. 7th century BC, (British Museum)

After traveling twenty leagues (6) they broke bread; after thirty more they pitched camp. Every three days they covered the equivalent of a 45-day march. The exact length of the journey is not known, but is likely to have been six days, a mountain (or mountain range) being crossed each night before arriving at the seventh: the Cedar Mountain. After each day's journey they dug a well before the setting Sun, then Gilgamesh climbed a mountain to secure a dream, a favorable message from Shamash.

Five dreams are preserved, at least partially. (7) In the first, Gilgamesh stood in a deep mountain gorge, and the mountain fell down on him. A bravely optimistic Enkidu attempted to interpret the dream: "Your dream is good. The mountain is Humbaba. Now, surely, we will seize and kill him, and throw his body down on the plain." In the second, the mountain fell and struck Gilgamesh, taking hold of his feet. Then came a blazing light and in it was someone whose grace and beauty were greater than the beauty of this world. He pulled Gilgamesh out from under the mountain, gave him water to drink. He comforted him and set his feet on the ground.

The third and fourth dreams also seemed propitious. The fifth, however, was both hopeful and foreboding: Gilgamesh took hold of a bull from the wild who raised dust deep into the sky with its bellows. He sank to his knees and, similar to the second dream but more fully explained, was extricated by Shamash and given water by his inner god, the "old man who begot and respects you" -- the divine Lugalbanda (note the two-part divine, one-part human relationship).

As Gilgamesh and Enkidu approached the forest, their trepidation grew. Shamash sent a message from the sky: "Humbaba has removed six of his seven cloaks. Hurry, do not let him hide in the forest thickets." Humbaba thundered like the god of the storm. Enkidu's arms became stiff with fear. Gilgamesh reassured him: "Have we not crossed all the mountains? Are you not experienced in combat? Touch [my heart], you will not fear death. Take my hand, let us go on together. Do not let the combat diminish your courage; forget death. One cannot stand alone. When two go together each will shield himself and save his companion." Arriving at the forest gate they fell silent and came to a halt. They saw the height of the Great Cedar. Where Humbaba walked, a path was made. The road was good. Enkidu acknowledged the encouragement of Gilgamesh with a mirrored wisdom of his own: "A slippery path is not feared by two people who help each other. . . . A three-ply towrope cannot be cut." (8)

Much of Tablet V here is undecipherable or missing; but earlier versions relate that Gilgamesh and Enkidu began cutting down trees, provoking Humbaba to rage. A battle ensued and, with the assistance of Shamash, Humbaba was defeated. He wept and pled for his life, promising Gilgamesh to become his servant, to cut down as much wood as would be necessary for his palace. Gilgamesh would have taken pity but for Enkidu, who was not beguiled by Humbaba's tricks and deceit. In one version of the Sumerian story, Enkidu compares Humbaba, if he were released, to a "captive warrior given freedom, a captive priestess returned to the cloister, a captive priest returned to his wig [pretentious dress and empty rituals]; he will confuse the mountain road for you." This overtly hints at what Humbaba ("whose face often changes") partly represents, and more subtly foreshadows what lies ahead for Gilgamesh -- the "mountain road" -- a theme brought to climactic development in the later tablets of the Babylonian version, as will be seen in Part III of this series.

Even though divine consequences would surely follow, Enkidu urged Gilgamesh to lay the axe to Humbaba's neck. Humbaba uttered an ominous curse against Enkidu: "May he not live the longer of the two." Enkidu shouted to Gilgamesh to pay these words no heed: "Do not listen to Humbaba!" They cut off his head; trees were felled, including the Great Cedar whose crown scraped the sky. From its timber a door was made -- 72 cubits high, 24 cubits wide, 1 cubit thick -- for Enlil's temple in Nippur. Gilgamesh and Enkidu -- their names will now be remembered by posterity, and by the gods.

Returning to Uruk in the flush of victory, Gilgamesh washed and dressed himself in his royal robes. When he put on his crown, great Ishtar lifted her eyes and beheld his manly beauty. "Be my lover," she entreated him, "would that you be my husband and I your wife. I offer you wealth, fame, and unrivaled power if you would but pledge yourself to me." Gilgamesh was not so easily tempted. What could he, still part mortal, offer in return to the Queen of Heaven? Just how well would it go with them? "You're an oven," he said to her warmly,

. . . that goes out in the cold.

A loose door that keeps out neither wind nor storm.

. . . .

A battering ram that shatters in the land of the enemy

A shoe that bites the owner's foot.

He then recited a litany of lovers Ishtar had wronged, from Tammuz to Ishallanu, her father's gardener whom she turned into a frog or dwarf. Ishtar flew up to heaven in a rage and complained bitterly to Anu: "Father, Gilgamesh insulted me!" "Come now," said Anu, "didn't you yourself pick a fight with Gilgamesh? He merely recounted your bad faith and your curses." The words fell on deaf ears. Ishtar demanded she be given the Bull of Heaven (9) to destroy Gilgamesh, or else she would smash the gates of the Netherworld: the dead would rise and devour the living. Anu capitulated and placed the bull's nose rope in Ishtar's hands, who promptly drove it down to Uruk.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu (note Enkidu's apelike face in this unusual depiction). Cylinder seal from Ur, 3rd millennium BC, height 1-1/2 inches.

When the Bull landed on earth, it snorted so powerfully a hole opened up swallowing one hundred men. A second snort -- two hundred men swallowed up. A third snort and a hole opened before Enkidu, who then seized the bull by its thick tail, crying out to Gilgamesh, "Friend, we have made ourselves a great name. How shall we overthrow him?" Like a matador, mighty Gilgamesh thrust his knife in one swift blow to its neck, just behind the horns. Crashing down, the bull heaved a mighty sigh. Gilgamesh and Enkidu tore out its heart and set it before Shamash.

Ishtar cursed Gilgamesh; he had slandered her and killed the Bull of Heaven. When Enkidu heard her cursing, he tore out the bull's thigh and threw it in her face. Ishtar propped up the thigh and, together with her temple courtesans, set up a great lamentation. Meanwhile Gilgamesh claimed the horns, the symbol of mastery and wisdom, and hung them in the room of his rulership. Gilgamesh and Enkidu washed their hands in the Euphrates; they embraced, and rode triumphantly through the streets of Uruk. Gilgamesh, the best-formed of heroes; Enkidu, the most powerful among men.

Thus ends the sixth tablet, the midpoint of the twelve-tablet story -- an important junction marking the transition from the temptations and trials of this world to the greater mysteries of death and rebirth.

The main themes of Humbaba, the Cedar Forest, and the Bull of Heaven were skillfully synthesized in the later Greek story of Theseus and the Minotaur, an allegory about the conquest and mastery of one's animal nature in the labyrinthian "forest" of incarnated life. To prevent the annual sacrifice of seven youths and seven maidens (representing the bipolar principles of our sevenfold nature), Theseus entered the winding underworld darkness which leads inevitably to the hungry minotaur who would devour him (note the winding features of Humbaba's mask, the "fortress of the intestines," representing our insatiable appetitive nature). Like Gilgamesh, who was urged to "stand against Humbaba" devoid of all but one of his seven protective auras, Theseus was advised to "slay" the minotaur while he slept. His release from the Labyrinth was ensured by a clew of thread, symbol of divine wisdom and guidance, supplied by King Minos' daughter, Ariadne, whom he subsequently married. King (spirit), daughter (wisdom), hero (human soul): saved by yet another version of the "three-ply towrope."

Tablet VII begins with Enkidu speaking to Gilgamesh the next morning: "Hear the dream I had last night. The great gods were in council and Anu said to Enlil, 'Because they have slain the Bull of Heaven, and Humbaba, too, for that reason one of them must die. The one who stripped the mountain of its cedars must die.' But Enlil said, 'Enkidu must die; Gilgamesh shall not die.' Shamash rejoined that it was by Enlil's command that the Bull and Humbaba were killed. 'So why should innocent Enkidu die?' 'Because,' said Enlil, 'you, Shamash, went down to them daily.'" Having recounted the dream, Enkidu then lay down sick before Gilgamesh.

"Oh my brother, my dear brother!" cried Gilgamesh, tears streaming. "They would free me at the cost of my brother. Must I never again see my brother with my eyes?" In his fever, Enkidu at first became angry, cursing both the trapper who had tricked him, and the temple courtesan who had widened his mind and brought him to Uruk. If it hadn't been for them, he thought, this undignified way of dying would never have come to pass. Why could he not die a manly death in battle? Shamash heard Enkidu, and spoke to him from heaven, reminding him of the benefits he had derived from the courtesan and Gilgamesh: had he not enjoyed the food of the gods, the drink of kings, fine clothes, honor, position, and -- to be valued above all -- Gilgamesh's beloved friendship? With these words Enkidu's angry heart grew still. Twelve days he lay dying, at the beginning of which he was beset by a disturbing vision of the Netherworld, its purgative mansions, its denizens, and his judgment and fate recorded on the Tablet of Destinies. As he slowly slipped away, Gilgamesh wept:

He was the axe at my side, the dagger in my belt, the shield in front of me, my festive garment, my splendid attire. An evil has risen up and robbed me. . . . Now what is this sleep that has taken hold of you? You've become dark. You cannot hear me . . . And he -- he does not lift his head. I touched his heart, it does not beat.

Gilgamesh covered his friend's face like a bride's. Like an eagle he circled over him. Like a lioness whose whelps are lost he paced back and forth. Gilgamesh tore out rolls of his hair. He threw down his fine clothes like things unclean. Then he issued a call through the land: "Artisans, make for my friend an image. Enkidu! of lapis lazuli is your chest, of gold your body.''

Gilgamesh wept for Enkidu; he roamed the hills. Then a despairing thought entered his mind, stopping him suddenly: "Me -- will I too not die like Enkidu? Sorrow has come into my belly. I fear death!" From despair to determination, he felt the desire for knowledge swell in his heart: "I will seize the road, the wheel-rim (10); quickly I will go to the house of Utanapishtim, the Faraway One, son of the great king Ubaratutu. I approach the entrance of the mountain at night. I see lions and am terrified. I lift my head to the moon god. To the [lamp] of the gods my prayers ascend: . . . Preserve me!"

Grieving for his dead companion Enkidu, Gilgamesh seized the road in search of knowledge. He entered the wilderness, crossed uncrossable mountains, and traveled the seas -- all without sleep to calm his face. He battled wild beasts, covered himself with their skins, and ate their flesh. Shamash, god of the Sun, grew worried and bent down to Gilgamesh: "Where are you wandering? The life that you seek you will never find." Gilgamesh answered, "When I enter the Netherworld, will rest be scarce? . . . Let my eyes see the sun and be saturated with light! When may the dead see the rays of the sun?"

He arrived at length at Mount Mashu which guards the coming and going of Shamash. Its twin peaks reached the vault of Heaven, its feet touched the Netherworld below. Guarding its gate were the two Scorpion-people, whose terror is awesome and whose glance is death. When they saw Gilgamesh approach, the Scorpion-man called to his woman: "The one who comes to us, his body is the flesh of the gods." The woman said, "(Only) two-thirds of him is god, one-third is human." The Scorpion-man then called to Gilgamesh: "Why have you undertaken this long journey, whose crossings are perilous?"

Shamash (the Sun) between Mashu's Twin Peaks, Akkadian, 3rd millennium BC (British Museum).

Gilgamesh replied, "I have come to seek Utanapishtim (11) my forefather, who stands in the assembly of the gods and has found eternal life. Death and life I wish to know."

"Never has a mortal man done that," said the Scorpion-man. "No one has traveled the remote path of the mountain, for it takes twelve double-hours (12) to reach its center; thick is its darkness and there is no light." Gilgamesh was not dissuaded and commanded that the gate be opened. The Scorpion-man spoke to King Gilgamesh, flesh of the gods: "Go safely, then; for you the gate is open."

Gilgamesh entered the mountain; he took the Road of the Sun, the night road followed by Shamash. When he had gone one double-hour, thick was the darkness; there was no light, he could see neither behind him nor ahead of him. Even after seven double-hours, there was darkness still. At eight, he was hurrying. At nine, the north wind bit into his face. Ten, "the [rising] was near." Eleven, he came out before the sunrise. At twelve double-hours there was brilliance. Before him was a garden planted with trees of the gods, fruited with carnelians, lapis lazuli, and other radiant gems -- a delight to behold. (13)

As Gilgamesh walked about, she raised her eyes and saw him -- Siduri, the tavern-keeper, who dwells at the edge of the sea and gives refreshing drink to the spiritually thirsty. Because of his wild appearance and aggressiveness, she barred her gate. From her roof she called out: "Let me learn of your journey." He told her of his adventures with Enkidu, their friendship, and Enkidu's death. Six days and seven nights he had wept for Enkidu. He feared death. Now he searched for Utanapishtim to learn the secret of life. But Siduri -- like those before her -- tried to dissuade Gilgamesh from continuing on, reminding him that when the gods created mankind, they allotted death to it, retaining life in their own keeping. "Be therefore happy with the pleasures given to man," she said,

Let your belly be full. Make every day a day of rejoicing. Dance and play every night. Let your raiment be clean. Let your wife rejoice in your breast, and cherish the little one holding your hand. -- Old Babylonian version (Sippar iii.1-14)

Again Gilgamesh would not be deterred. He had traveled a long, wearying distance in search of knowledge. What, he asked, is the way on from there? Siduri replied that never had there been a crossing of the sea; none went but Shamash. Painful is the crossing, troublesome the road, and the Waters of Death block its passage. But there at the shore, she pointed out, lives Urshanabi, (14) ferryman to Utanapishtim. "With him are the Stone Things. He picks up the Urnu snakes in the forest. If it is possible, cross with him, or else retrace your steps."

For reasons unexplained, Gilgamesh raised his axe and attacked the Stone Things, smashing them in his fury. Hearing the commotion Urshanabi returned from the forest, asking Gilgamesh why he looked so terrible. Gilgamesh repeated his woeful tale, then in turn demanded to know the road to Utanapishtim, the Faraway One. Urshanabi explained that Gilgamesh's own hands prevented his crossing, for he had smashed the Stone Things. "They enabled my crossing, for my hands must not touch the Waters of Death." The Stone Things have been variously conjectured to be idols, magical amulets, shore pylons holding a crossing rope ("Urnu snakes"), and magnetic lodestones for navigation. Their meaning remains a mystery, but the Hittite version offers a faint clue by having Urshanabi call them "those two stone images which always carried me across."

Nevertheless, the inventive Urshanabi wished to help, and sent Gilgamesh to the forest to cut punting poles (300 in the Old Babylonian version, each 60 cubits in length). The 45-day voyage to the Waters of Death was completed in three. Once there, the poles were used to punt the boat, one pole each push, so that Gilgamesh, too, would not touch the lethal waters. When the last pole was gone, they hung their clothing from Gilgamesh's outstretched arms to sail the remaining distance. As they approached the shore, Utanapishtim saw that the Stone Things were smashed and that a stranger was on board. He asked Gilgamesh why he looked so wasted and desolate, and Gilgamesh once again recounted his tale of grief and weariness.

Instead of offering comforting words, the Faraway One jolted him by going straight to the point: "Why do you [chase] sorrow, Gilgamesh, you who have been made of the flesh of the gods and man? . . . No one can see the face or hear the voice of Death. Do we build a house forever? Do we seal a contract for all time? Do brothers divide their inheritance forever? Does hostility last forever between enemies? Does the river always rise higher, bringing on floods? The dragonfly floating on the water, gazing upon the face of the Sun -- suddenly, all is emptiness! The sleeping and the dead, how alike they are! An image of Death cannot be depicted, even though man is [imprisoned by it]. The great gods established Death and Life, but the days of death they do not disclose."

"But you, Utanapishtim," said Gilgamesh, "your features are no different from mine. I am like you. How is it that you stand in the assembly of the gods and have obtained eternal life?"

Utanapishtim replied: "I will tell you a secret of the gods, Gilgamesh; I will reveal to you a mystery. Shortly after the Flood had been decreed for mankind by the great gods, Enki -- without breaking oath -- advised me to tear down my house and build a boat, to abandon possessions and save life. Into the vessel was to go the seed of all living creatures." Worth noting is the same concept found in ancient India, where Vishnu counsels Vaivasvata Manu: "Seven rain clouds will bring destruction. The turbulent oceans will merge together into a single sea. They will turn the entire triple world into one vast sheet of water. Then you must take the seeds of life from everywhere and load them into the boat of the Vedas" (Matsya Purana 2.8-10).

Enki gave Utanapishtim instruction on the boat's dimensions and construction. It was to measure 120 cubits on a side, six decks dividing it into seven levels, all measured to a height of 120 cubits, with nine compartments inside. On the (sixth?) day it was completed. The boat was launched with difficulty, until two-thirds was submerged. Then after everything had been loaded in, including all the craftsmen, the deluge came. Raging storms reached to the heavens, turning all that was light into darkness. As in a battle no man could see his fellow. Even the gods, terror-stricken by the tempest, fled to the heaven of Anu, cowering like dogs. Ishtar cried out like a woman in travail; Belet-ili (Aruru) lamented that the olden time had turned to clay because she had spoken evil in the assembly of the gods.

Six days and seven nights the winds blew. At sunrise on the seventh day they subsided and the storm ceased. Utanapishtim opened a window and light fell on his face. Water was everywhere. All was silence. All mankind had turned to clay. On the submerged peak of Mt. Nisir the ship landed. After another seven days, he sent a dove forth, but it came back. He sent a swallow out; it returned too. Then a raven, and this one did not return. When the waters receded, he went forth from the boat and poured a libation to the gods. But Enlil was furious: all mankind was to have been destroyed. Who had revealed the secret? Enki reproved Enlil for causing the Flood, then explained how in a vision given to Utanapishtim the secret had been discovered. His fate must be decided by Enlil, who then declared that Utanapishtim and his wife shall become like gods. And from the boat the gods took them to the faraway land, to dwell at the Mouth of Rivers -- sacred rivers symbolic of the continuous stream of divine wisdom flowing into human life.

The Flood story, adapted from the independently-composed Atrahasis Epic, (15) was evidently inserted into the Babylonian Standard Version as an expansion of Utanapishtim's lessons about the impermanence and periodicity of manifested existence. Furthermore, not only does it explain Utanapishtim's role as forefather, protector, and preserver, it tacitly asserts the possibility of man's immortality, forming a natural bridge to the next sequence of events.

Utanapishtim asked Gilgamesh, "Who will convene the gods, so that you may find the life you are seeking? Come, you must not sleep for six days and seven nights." Try as he would, Gilgamesh could not withstand the onslaught of sleep and almost immediately succumbed to it. He was awakened by Utanapishtim on the seventh day, only to learn that he had failed in his objective. Gilgamesh had achieved much, but conscious immortality was beyond his capacity to sustain; for there were life-lessons still to be mastered. Bereft of his physical (Enkidu) self, he lamented: "What can I do, where can I go? A thief has stolen my flesh. Death lives in the house where my bed is; wherever I set my feet, Death is." Return to Uruk he must, to "suffer" again the "death," and rebirth, of imbodied life.

That Gilgamesh's journey is an allegory from the Mysteries may be seen more clearly in light of the following excerpt, written over a millennium later by Plutarch (as quoted by Themistius):

If the belief in immortality is of remote antiquity, how can the dread of death be the oldest of all fears? . . .

. . . [When the soul dies] it has an experience like that of men who are undergoing initiation into great mysteries; and so the verbs teleutan (die) and teleisthai (be initiated), and the actions they denote, have a similarity. In the beginning there is straying and wandering, the weariness of running this way and that, and nervous journeys through darkness that reach no goal, and then immediately before the consummation every possible terror, shivering and trembling and sweating and amazement. But after this a marvellous light meets the wanderer, and open country and meadow lands welcome him; and in that place there are voices and dancing and the solemn majesty of sacred music and holy visions. And amidst these, he walks at large in new freedom, now perfect and fully initiated, celebrating the sacred rites, a garland upon his head, and converses with pure and holy men; . . ." -- "De Anima," Moralia xv.177-8 (Loeb)

Though not yet "perfected," Gilgamesh had nevertheless earned the garland of a lesser degree, for the text here alludes to the basic initiatory themes of baptism and rebirth (spiritual and physical). Utanapishtim directed Urshanabi to ferry Gilgamesh to the place of washing, to throw off his old skins and let the sea carry them away, that his fair body may be seen. "Let the band around his head be replaced with a new one. Let him be clad with a royal garment, the robe of life. Until he finishes his journey to the city, may his garment not show age, but may it still be quite new."

As they were sailing away, Utanapishtim's wife reminded her husband that Gilgamesh was weary and needed help to return to Uruk. So Utanapishtim revealed to Gilgamesh another secret of the gods: under the sea there is a wondrous plant, like a flower with thorns, that will return a man to his youth. Gilgamesh then opened the conduit, tied stones to his feet, plunged into the deep, and retrieved the plant. "In Uruk I shall test it on an old man. Its name shall be 'Old Man Grown Young' [nearly identical in meaning with Gilgamesh's Sumerian name]. I will then eat it that I may return to my youth." After twenty double-hours they broke off a morsel; after thirty, they stopped for the night. While Gilgamesh bathed in a pool, a serpent smelled the plant's fragrance. It came up from the water and snatched the plant, sloughing off its skin as it returned to the water. Seeing that the plant of rejuvenation had disappeared, Gilgamesh sat down and wept. For whom was the blood of his heart spent? "I have not won any good for myself; for the earth-lion I have obtained the boon. . . . Let us withdraw, Urshanabi, and leave the boat on the shore." Perhaps a glimmer here of realization; the story makes a point about self-forgetfulness still to be learned -- and about readiness: that full enlightenment is the work of lifetimes.

Another day's journey and they arrived at Uruk, whereupon Gilgamesh picked up the thread of his past. "Go up, Urshanabi, onto the walls of Uruk. Inspect the base; view the brickwork. Is not the very core made of oven-fired brick? Did not the seven sages [or creators] lay down the plan of its foundations? In Uruk, the house of Ishtar, one part is city, one part orchards, and one part claypits. Three parts and the Ishtar temple [Eanna], Uruk's wall encloses." And spirit, soul, and body again make up Gilgamesh who, chastened but wiser from his experience, now resumes his life's work, symbolized by the guardian wall of Uruk which ever protects our humanity.

Ziggurat in the Eanna Sector at Uruk (Andre Parrot, Sumer)

Thus concludes the eleventh tablet and the main part of the story. Tablet 12 is a partial translation of the Sumerian poem "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld." Because the episode appears to be out of sequence (Enkidu is alive), many commentators have called it an appendix. While this assessment has merit, the story's content and placement suggests deliberate symbolic intent: twelve was numerically and philosophically important to the Babylonians as it marked the end of a cycle and the prelude to the next. Consistent with the theme of reimbodiment, Enkidu is once again reunited with Gilgamesh, though he soon descends alone into the Netherworld to retrieve two objects belonging to Gilgamesh which had fallen there. The subject of the underworld (which can also stand as a metaphor for our world) relates directly to Enkidu's death vision at the beginning of Tablet 7, the exact midpoint of the 12-tablet version. Furthermore, Tablet 12 contains only about half the lines of the others and ends abruptly, no text missing, nothing said about the last days of Gilgamesh, story incomplete. A Sumerian-language poem of uncertain origin, "The Death of Gilgamesh," seems to have been intentionally omitted from the 12-tablet version, possibly because its stress on the permanence of death was philosophically inconsistent with the epic's more hopeful outlook. The twelfth tablet suggests instead -- albeit between the lines -- that we have not heard the final chapter, but have reached only another turning point in the cycle of life.

Regardless of the imperfections of text, translation, and interpretation, the resurrection of Gilgamesh from the rubble of the past is an impressive witness to the timelessness and universality of our spiritual and human heritage. Like Buddhist terma texts intentionally buried for the benefit of later generations, Gilgamesh has been recovered at a propitious time. For whatever progress we may have achieved (or failed to accomplish) in the several millennia since it was first inscribed, his story is a powerful reminder of a single sacred truth about who we are: companions, friends, and brothers all of us, traveling the road of life together on a heroic quest that is -- in its essence -- one part human, two parts divine.

The following two books integrate the more recent discoveries and additions to our knowledge of Gilgamesh:

George, Andrew R., The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation, Barnes and Noble, Inc., New York, 1999. Includes the Sumerian and Old Babylonian texts.

Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, The Epic of Gilgamesh, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1989

Other helpful translations and/or renderings:

Gardner, John, and John Maier, Gilgamesh: The Version of Sin-leqi-unninni, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1984

Heidel, Alexander, The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1949

Sandars, N. K., The Epic of Gilgamesh, Penguin Books, Baltimore, 1960

Temple, Robert, He Who Saw Everything: A Verse Version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Rider, London, 1991

Related Sources:

Fiore, Silvestro, Voices from the Clay: The Development of Assyro-Babylonian Literature, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1965

Jacobsen, Thorkild, The Sumerian King List, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1939

------, The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1976

Knoche, Grace F., "Two-Thirds God, One-Third Human," Sunrise, Nov 1980

------, The Mystery Schools, Theosophical University Press, Pasadena, 1999

Kramer, S. N., History Begins at Sumer, Thames & Hudson, London, 1958

------, Sumerian Mythology, Revised Edition, Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1961

Maier, John, ed., Gilgamesh: A Reader, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Wauconda, IL, 1997

Tigay, Jeffrey H., The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1982; reprint, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Wauconda, IL, 2002

www.gilgameshonline.com

The Epic of Gilgamesh: An Outline with Bibliography and Links

(From Sunrise magazine, October/November 1999, December 1999/January 2000; February/March 2000; copyright © 1999 Theosophical University Press)

ENDNOTES:

1. Similar in concept is the name of Chinese sage Lao-tzu, which means both the "Old Boy" and "Old Master." (return to text)

2. Interestingly, the principal source is the prologue to the Sumerian story, "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld," part of which comprises Tablet 12 of the Babylonian version of Gilgamesh. (return to text)

3. Adapted from renderings by John Gardner and John Maier, Andrew George, Maureen G. Kovacs, Alexander Heidel, and N. K. Sandars, to whom I am indebted (see bibliography above). (return to text)

4. In theosophic terms "two-thirds divine, one-third human" fits well with the higher triad of the sevenfold human constitution: atman (divine essence), buddhi (awakened spirit), and manas (human mind). His titanic form -- later called the "flesh of the gods" -- undoubtedly refers to his inner spiritual form and stature. (return to text)

5. This is an interpretation based on the text's symbolism: Gilgamesh is two parts divine, one part human. It follows that Enkidu, as his "reflection," is one part human, two parts animal; the synthesizing principle which unites them (the text suggests Anu) is the implied seventh -- seven being one of the most frequently recurring numbers in the story and in universal symbolism. (return to text)

6. Beru, literally a "variable interval," which can indicate a unit of (1) distance, commonly about 10 kilometers, (2) time, 120 minutes (a "double-hour") but variable, or (3) arc, usually 30 degrees or 1/12 of a circle. (return to text)

7. The number and sequence here follows that of Andrew George, The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation (Barnes & Noble, 1999) which incorporates the latest discoveries and scholarship. (return to text)

8. First used in the original Sumerian story, this symbol of strength in union was incorporated by the author of Ecclesiastes (4:9-12). Compare also the "sacred triple cord" of the Brahman sannyasin, the Masonic "cable-tow" of brotherhood, and more particularly the Hindu sutratman or "thread-self" -- man's immortal lifeline connecting him with his inner divinity. For an interpretive essay on this universal symbol, see Sunrise, April/May 1989, "Saved by a Three-ply Towrope." (return to text)

9. The constellation Taurus. During the 4th and 3rd millennia BC, the sun rose in the neighborhood of Taurus at the spring equinox. That the Sumerian priest-initiates were aware of the sun's precession through the zodiacal constellations (a cycle of approximately 25,800 years) is suggested by the Sumerian King List: after the Flood, the divine kingship was lowered and dwelt in Kish for 24,510 years, after which it was moved to Uruk; 2,044 years then elapsed (almost exactly 1/12 of 24,510) until the beginning of Gilgamesh's 126-year reign. In theosophic tradition a one-twelfth part of the precessional Great Year is known as a messianic cycle. Judaism is accordingly linked with the ram -- Aries; Christianity with the fish -- Pisces. The association of Gilgamesh with the messianic cycle, moreover, is consistent with his divinization as Lord of the Netherworld and identification with the "annually" dying and rising god Dumuzi. (return to text)

10. Interpreted astronomically, the wheel-rim symbolizes the "road" or orbit of the celestial wheel, and is a reference to Gilgamesh's impending initiatory journey. The underlying motif of the allegories presented thus far concerns a fundamental objective of the Mysteries: before the secret of life may be known, the initiant must shed his lower nature which "entombs" his divine essence -- i.e., his physical/Enkidu self must "die" (temporarily), so that his spiritual self may know and be known by the god within. For a concise overview of initiatory patterns and symbols of the Mystery tradition, see Grace F. Knoche, The Mystery Schools, Theosophical University Press, 1999. (return to text)

11. Also spelled Utnapishtim and Uta-napishti, Babylonian for "He has found life"; in Sumerian literature he is known as Ziusudra ("Life of long days") and called "Preserver of the Seed of Mankind." Berossus spelled his name Xisuthros or Sisithros. (return to text)

12. Beru, "variable interval," see Note 6 above. (return to text)

13. Cf. Plato, Phaedo §110; Revelation 21:18. (return to text)

14. Urshanabi's name implies a number symbolism, for it means "Priest [or Servant] of 2/3rds." He is the son-in-law of Ea/Enki (numerical value 40, 2/3rds of Anu's 60). The name accordingly denotes his role as priest/servant to Gilgamesh, who is 2/3rds divine. (return to text)

15. Atrahasis, "Surpassingly wise," is an epithet of Utanapishtim as the survivor of the Flood. For a comparison of the Sumerian, Babylonian, and Hebrew accounts of the Flood, see Alexander Heidel, The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels, pp. 102-19, 224-69. (return to text)