Every sun that we discern in the midnight sky, every human creature, every dhyani-chohan whose presence we may instinctively feel, is not only an evolving and progressing entity -- especially in the cases of the stars and of the gods -- but is also an entity which, motivated by celestial love and wisdom divine, each one in accordance with its own karmic powers and to the extent that it may, has halted on its path or advances slowly on its path, in order to give help to the multitudes and hosts of less progressed entities trailing along behind.

Thus a star, our sun for instance, is not only an evolving god in its divine and spiritual and intellectual and psychical and astral aspects, but is also bending towards us from its celestial throne as it were, and thus appears in our own material realms helping us, giving us light, urging us upwards. -- G. de Purucker, The Four Sacred Seasons

At the time of the summer solstice, often referred to as the Great Renunciation, a human being of Christ-like soul makes a solemn vow to forgo his further progress in order to help those around and behind him struggling to achieve their own spiritual development. This is the bodhisattva vow: to follow the path of compassion.

Each of us, in the privacy of our innermost being, may consciously choose to become a channel for the reception of light that it may flow out into the world. And once the vow to awaken is registered deep within the soul, an Ariadne thread seems to guide us, and we know that we must "accept the cosmos" -- groan if we will, but work with and never against the workings of the cosmos in ourselves and in our environs.

What do we mean by renunciation? Let's take a simple analogy of a person gifted along several lines, musically, artistically, or in a literary sense -- there is something burning within him that would like to develop one or more of those talents. But a call comes, and without hesitation he gives up those private goals. Something still more profound pulls him to forget his personal ambitions and aspirations, and offer himself where most needed.

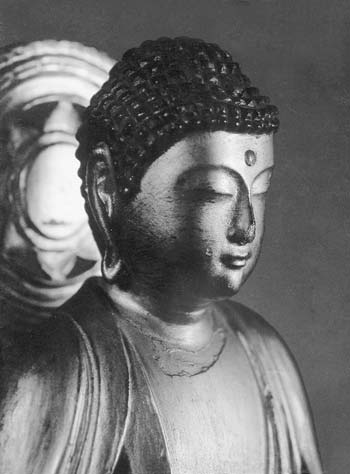

The buddha of compassion that we are most familiar with is Gautama. When he attained enlightenment under the bodhi tree, legend tells that he remained in a state of wonderment for forty-nine days, during which he was tempted to think, "Who will understand what I have to offer? How can I explain to others what I have experienced?" Then mighty Brahma swiftly dropped a thought into his heart: "If only a few, or even one person, understands . . ." So Gautama came back to the world as buddha, "enlightened," and gave his first sermon, "Setting in Motion the Wheel of the Law," to the five monks who had been with him earlier.

There followed forty-five years of ministry, in which Gautama, now Buddha, taught the Middle Way between extremes, the Four Noble Truths on the cause and cure of suffering, and the Noble Eightfold Path: right views, right aspirations, right speech, right conduct, right means of livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration. The Pali word translated as "right" is samma, meaning "perfected, utmost." The Buddhist scriptures were written down long after the Buddha talked with his disciples as they walked from village to village. What has come down which is of prime importance is that every one of us has the buddha-nature within. The Mahayana School in particular emphasizes the compassionate aspect of the bodhisattva, "he whose essence is wisdom."

Undoubtedly Gautama made the noble vow many lifetimes ago to become Tathagata -- one of those who have "Thus come" or "Thus gone": ``I shall not enter into final nirvana before all beings have been liberated.'' He was one in a succession of buddhas and bodhi- sattvas who come out of an urgency to awaken souls from ignorance.

One of Buddha's injunctions to the brethren was: If you would attain the heights, you must be "eager to learn." Similarly, the Bhagavad-Gita urges Arjuna to "stand up and fight!" We mustn't go on sleeping the sleep of death: the current of life is ever forward, and if we allow ourselves to become lethargic, spiritually and otherwise, we drift backwards.

In contrast to the summer solstice, the autumnal equinox is called the Great Passing, which pertains to the entering of nirvana and leaving forever the world of men, as the pratyeka buddhas do (pratyeka means "for oneself"). These beings are lofty and spiritual, though not yet of the line of compassion. They do not yet have the full wisdom or power of the "complete or perfect buddhas," the buddhas of compassion. The knowledge of the pratyeka or "private" buddhas is likened to the light of the moon, whereas that of the "complete" buddhas is likened to the thousand-rayed disc of the autumnal sun.

How is it possible that a person who has attained buddhahood has not learned the lessons of caring? Many Buddhist and theosophical writings place a strong emphasis on compassion in order that we realize that NOW is the time to check our motive and ask ourselves: "What do we most deeply want?" If we can answer that question truly and honestly, we will know how much of our concern is self-centered and how much is other-centered. If we were completely, singly, altruistically motivated then we would indeed shine like the thousand-rayed disc of the autumnal sun.

The pratyeka path is one of limitation. We can imagine that in the long course of his evolution every buddha of compassion has at one time either been a pratyeka buddha or been tinctured with that quality of thought. We don't really burn with that profound sense of identity with everyone unless we have suffered, unless we have gone through many "failures" and have been selfish and self-centered. At our heart, however, even now we are cosmic organisms, part of the sacrificial act that brought the universe into being. That every creature "has halted on its path or advances slowly on its path, in order to give help," is a stunning concept. Everything above is bending downward, just as everything less progressed is looking upwards, a two-way flow of consciousness. There is a cosmic purpose, a cosmic love, a concern and caring of the whole universe for the smallest atom -- and that includes every human being, too. It is strengthening to realize that there is a network of compassion and altruism throughout humanity and the cosmos. This is the ground of our hope and purpose.

Let us trust that this beautiful season of the summer solstice will influence our world, which needs to learn in a deeper dimension the meaning of true renunciation. Not as something sad or solemn, but as a joyous giving of that which we count most precious, and a joyous giving up of that which we count unprecious. Anyone, no matter what his outer stature and religion, who is living by the inner code of doing good, being alert and sensitive to understanding the need of those near or far, is adding to the light-energies in this world. Such a one is affecting in remarkably strong and potent ways the thought-consciousness of humanity.

(From Sunrise magazine, June/July 2003; copyright © 2003 Theosophical University Press)

Agape means love for another self not because of any lovable qualities which he or she may possess, but purely and entirely because it is a self capable of experiencing happiness and misery and endowed with the power to choose between good and evil. To love a man is thus more than a feeling, it is a state of the will. -- Obert C. Tanner