Light filled the screen, and a chart appeared. At the top, Jerym read the words: MATRIX OF T'SEL; below that was a bunch of stuff. He hoped it wasn't going to be like school.

"This," Dak-So said, gesturing with a light pointer, "is not the T'sel. It is an introduction to it." His eyes were faintly luminous as he scanned the room. "Trainee Alsnor!"

Having the regimental executive officer call his name hit Jerym like a jolt of electricity, knocking the breath out of him. After a moment he managed to answer. "Yes Sir!"

"Trainee Alsnor, when you were a child, what did you dream of being? Some day."

A picture flashed in Jerym's mind, one he hadn't remembered in years. He'd been about seven years old, sitting in the living room watching a story about a war. Probably some fictional war set on a trade world somewhere—he couldn't remember much about it. But it had had T'swa in it; actors made up like T'swa, they had to be, and he'd thought it was really great. He'd told Lotta—she was watching it with him—he'd told her that when he was big, he was going to be a T'swa!

"A mercenary, sir!" he answered.

"When did you first dream about being a mercenary?"

"When I was—" He flashed to an earlier time. When he was really little. Could he have been only two or three? It seemed like it. His parents had been watching— Watching reruns of some of the same cubeage Captain Gotasu had shown them in the messhall, the second day he'd been here! He'd been playing with something—what it was didn't come to him now—but much of his attention had been on the screen. And he'd known then what he would someday be.

"—two or three years old, sir!" And hadn't recalled it since! He'd been into playing "soldier" after that, by himself and with other kids in the park, which older people didn't like. Some parents hadn't liked their children playing with him at all, because they usually ended up playing war. And he'd played warrior in his mind when the weather was bad or before he went to sleep. He'd never been someone else in his dreaming, either. He'd always been himself, grown.

"Thank you, Alsnor." Jerym realized then that he'd stood up when his name was called, and sat back down. Dak-So continued.

"Did any of the rest of you dream of being a warrior or mercenary or soldier a lot when you were children?" A general assent arose, not loud and boisterous, but thoughtful, contemplative. It occurred to Jerym that the others, or most of them, were recalling as he had.

"Then perhaps it is real to you that a person, every person, begins life with an intention, a purpose to be something more or less specific. Be it athlete, dancer, warrior, farmer . . . Something.

"Now look at the screen."

Jerym had forgotten the screen. He gave it his attention.

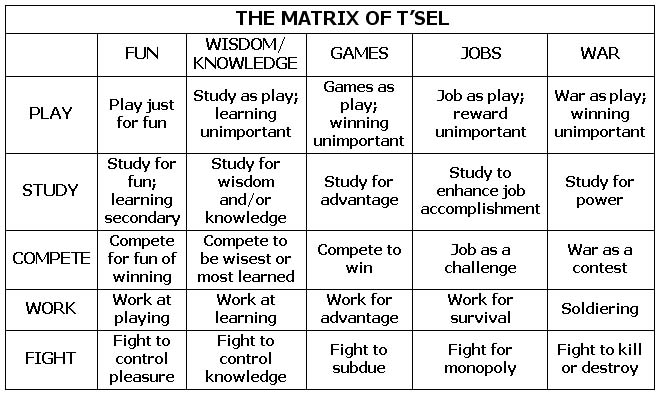

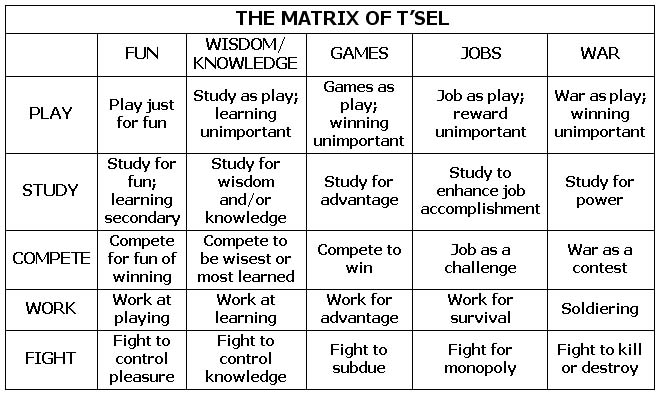

"There is a row across the top, in capital letters, defining categories of purposes from Fun to War. The words here, of course, are in your own language, Standard. The originals are in Tyspi, my language, and the translations, being restricted largely to one-word headings, are not precise. In fact, they differ slightly in different translations. But they provide a useful approximation.

"Any human activity can be fitted into one of these categories.

"So. In which of them does Warrior fit?"

A number of voices answered: "War."

"And a farmer?"

"Job."

"What of a dancer?"

There was less unanimity on dancer; some said Job and a few Games, but more, after hesitation, said Fun. Of course it's Fun, Jerym thought. If we're talking about purposes.

"Very good. And on the left we have a capitalized series from Play to Fight. Now consider a possibility. Consider the possibility that a person is born to follow one of these purposes, from Fun through War. Depending on his environment and personal history, he will pursue that purpose if possible, at one of the levels from Play to Fight. Though he may also Work at Job, in order to survive. In many cultures, as a small child, he will be at the top, at Play. Often to move downward over the years until, usually from the level of Work, sometimes from that of Fight, he falls off the chart with his purpose abandoned."

Dak-So paused. "Look the matrix over. At what intersection of columns and rows do T'swa warriors fit?"

Answers started popping almost at once, building toward a consensus for War at Fight. Jerym felt an elbow nudge his arm, and Carrmak, grinning next to him, murmured "War and Play."

Jerym's eyes found the intersect of War and Play, and was irritated with Carrmak. Victory unimportant? Tell that to the T'swa!

"Tell me," Dak-So said, "when you have had fights lately, what are called 'fights,' how many of you tried to kill or destroy your opponent?"

No one spoke up.

"We have here a confusion because of words," Dak-So said. "This chart, this translation, has a column headed War, but with a subheading Battle, to better cover the full meaning in Tyspi. So for the sake of discussion, consider what you were doing as 'battling.' Did you battle to kill, or did you battle for pleasure? Or as a contest?"

The answers began quickly, divided between pleasure and contest. Jerym couldn't see much difference.

"Excellent! I will not tell you why the T'swa battle. Not now. I will point out, though, that when we have asked you why you have started fights, or done other destructive acts, no one has said to injure or destroy. Mostly the answers have been something like 'for fun,' or 'to see if I could take him.' Or 'to see what would happen.' Injury and destruction occurred, but they were not the purpose of the acts."

"Sir!" someone called. "Can I ask a question?"

"Ask."

"I read once that you guys, you T'swa, fight for money. That it costs a lot of money to hire a T'swa regiment. Wouldn't that put you at Work on the chart? Or at Job?"

"We do not make War to get money, although we receive money for it. Money is not our purpose, it is only a means. Most of it goes to our lodge, to finance the training of other boys such as we were, helping them fulfill their purpose. To make possible our way of life—the more than eleven years of training, the warring on various and interesting worlds with various and interesting conditions. And to care for us when we are unable.

"Let me mention that what you are doing, training as warriors, falls under the concept labeled here as War. A warrior delights in good, intelligent training. You may wish to examine whether you enjoy yours or not.

"Now, are there other questions?"

There were; more than thirty minutes' worth. Then Dak-So cut them off and they left the hall by companies, for more training.

From the assembly, Voker went with Dak-So to the T'swa colonel's office. There Dak-So poured them each a glass of cold watered fruit juice, the favorite T'swa drink.

"Carlis," Dak-So said, "despite your rather limited contact with the trainees, I must say you know them very well. Our presentations to them took hold better than I'd expected."

Voker grinned. "They're my people, Dak. I've dealt with them—coped with them, handled them, what have you—all my life. For most of that time, forty-one years, I was one of them. Lived as one of them, thought like they do, and had the Sacrament like all my generation, though in me it somehow didn't take the way it normally did.

"But you were right this morning. We do need to deliver the T'sel. If we can. What we did this afternoon was a start. It set things up, and I expect it to reduce the disorders considerably. But there's a lot of aberration there."

After they left the assembly hall, Jerym was too busy to think any more about the Matrix of T'sel or what it might mean to his life. When they finished training that evening and went to their barracks, each bunk had a printout of the Matrix of T'sel on it.

He put his on his shelf. He'd look at it when he wasn't so tired.

After showering he went to his bed. Next to Carrmak's. The lights were still on, and Carrmak was lying on top of the covers, looking at his copy. Jerym, before he lay down, saw Carrmak purse his lips and nod at whatever he'd just read, his eyebrows arched. Tomorrow, Jerym decided, he'd look his over during dinner break.