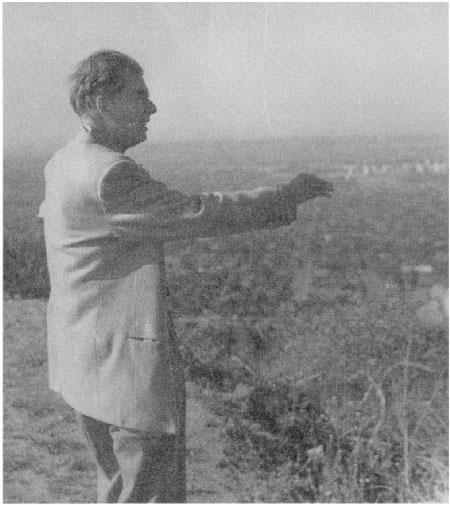

Aldous Huxley at his home in the Hollywood Hills during his first mescaline experience, May 6, 1953. Photo: Humphry Osmond

MOKSHA

Aldous Huxley’s

Classic Writings

on Psychedelics and the

Visionary Experience

Edited by Michael Horowitz

and Cynthia Palmer

Preface by Albert Hofmann

Foreword by Humphry Osmond

Introduction by Alexander Shulgin

Park Streek Press

Rochester, Vermont

Dedicated to

Sunyata, Jubal, Winona, Uri, Joaquin

GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGMENT is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: To Chatto and Windus, Ltd., for “Wanted: A New Pleasure” from Music at Night and Other Essays, Copyright © 1931 by Aldous Huxley, and a selection from The Olive Tree and Other Essays, Copyright © 1936 by Aldous Huxley. To the Curtis Publishing Company for “Drugs That Shape Men’s Minds,” from The Saturday Evening Post, Copyright © 1958 by The Curtis Publishing Company. To Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc., for a selection from This Timeless Moment by Laura Archera Huxley, Copyright © 1968 by Laura Archera Huxley. To Grune & Stratton, Inc. for “Mescaline and the ‘Other World’,” Copyright © 1956 by Grune & Stratton, Inc. To Harper and Row, Publishers, Inc., and Chatto and Windus, Ltd., for portions of Brave New World, Copyright © 1932 by Aldous Huxley; Time Must Have a Stop, Copyright © 1944 by Aldous Huxley; The Devils of Loudun, Copyright 1952 by Aldous Huxley; The Doors of Perception, Copyright © 1954 by Aldous Huxley; Heaven and Hell, Copyright © 1955 by Aldous Huxley; Brave New World Revisited, Copyright © 1958 by Aldous Huxley; Island, Copyright © 1962 by Aldous Huxley; Aldous Huxley 1894-1963: A Memorial Volume, edited by Julian Huxley, Copyright © 1965 by Julian Huxley; Forty-five letters (abridged) from Letters of Aldous Huxley, edited by Grover Smith, Copyright © 1969 by Laura Huxley; “Brave New World Revisited: Proleptic Meditations on Mother’s Day, Euphoria and Pavlov’s Pooch”, as it appeared in Esquire Magazine, Copyright © 1956 by Laura Huxley, by permission of Mrs. L. Huxley. To Laura Archera Huxley, for “Exploring the Borderlands of the Mind,” Copyright © 1962 by Aldous Huxley; “Culture and the Individual,” Copyright © 1963 by Aldous Huxley (courtesy G.P. Putnam’s Sons and H.M.H. Publishing Co., Inc.; originally appeared in Playboy); and “Visionary Experience,” Vol. 2 of The Human Situation, (Recorded) Lectures by Aldous Huxley, and reprinted by permission. To the Journal of Clinical Psychology for “Visionary Experience”, Copyright © 1962 by Aldous Huxley. Reprinted by permission. To New American Library, Inc., for a selection from High Priest, by Timothy Leary, Copyright © 1968 by League for Spiritual Discovery. To The New York Academy of Sciences, for “The History of Tension,” Copyright © 1957 by The New York Academy of Sciences. To the Parapsychology Foundation, Inc., for “The Far Continents of the Mind,” Copyright © 1957 by the Parapsychology Foundation, Inc. To The Psychedelic Review, for a selection from The Psychedelic Review, Vol. 1, no. 3, Copyright © 1964 by The Psychedelic Review. To University Books, Inc., for selections from The Psychedelic Experience, by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert, Copyright © 1964 by Richard Alpert, Timothy Leary, and Ralph Metzner. To Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, for “The Final Revolution,” Copyright © 1959 by Charles C. Thomas, Publisher. To The Viking Press, Inc., for “Interview with Aldous Huxley,” from Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, Second Series, Copyright © 1963 by The Paris Review, Inc.; All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Viking Penguin, Inc.

Contents

CHAPTER

4 1936 Propaganda and Pharmacology

PART II: Psychedelic and Visionary Experience

8 1953 May Morning in Hollywood

10 1954 The Doors of Perception

12 1954 The Far Continents of the Mind

13 1955 Mescaline and the “Other World”

15 1955 Disregarded in the Darkness

18 1956 Brave New World Revisited

24 1958 Drugs That Shape Men’s Minds

30 1960 Harvard Session Report

33 1961 Visionary Experience (Copenhagen)

34 1961 Exploring the Borderlands of the Mind

39 1963 Culture and the Individual

APPENDIXES

Editors’ Note

THE PRESENTATION IS chronological, except for the placement of one of the “Visionary Experience” lectures in an appendix at the end, and minor discrepancies arising from our attempt to organize each year’s correspondence. Addresses are arranged according to the dates they were delivered, rather than when they were printed; essays, according to the date of their first appearance in print, rather than their publication in book form. The memoirs of Humphry Osmond and Laura Huxley are placed in the time zone in which they belong rather than their date of publication.

In the interest of reproducing the complete texts of a number of very scarce and difficult-to-obtain essays and lectures, we have risked some occasional repetition which we hope is balanced by the virtue of providing those subtle variations in the language and ideas of a master prose stylist.

The spelling of mescalin(e) has not been standardized, as preference is pretty well split between the popular use of the shorter form, and the more scientific use of the longer. Huxley’s personal spelling of the word psychodelic has been retained, as this was clearly his preference.

“Bedford” refers to Sybille Bedford’s superb Aldous Huxley: A Biography (New York: Knopf, Harper & Row, 1974). The “Smith” number at the head of a letter refers to Professor Grover Smith’s monumental edition of Letters of Aldous Huxley (New York: Harper & Row, 1969). Although references are to the first U. S. editions of Huxley’s books, it should be noted that of the works reprinted in this volume all except Time Must Hare a Stop were first published in London by Chatto and Windus.

• • •

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of Robert Barker, a director of The Fitz Hugh Ludlow Memorial Library, who conceived of this anthology and provided source material and research. We thank Joan Wheeler Redington for providing the transcript of the “Visionary Experience” record album, and for comparing the French and English versions of the Planeté and Fate articles. We are very grateful to Mrs. Laura Huxley for her invaluable support and assistance at every stage of our endeavors, and to Michael R. Aldrich, Executive Curator of the Ludlow Library, for editorial assistance. We also thank Humphry Osmond, Alexander T. Shulgin, Timothy Leary and Ralph Metzner for supplying materials from their archives.

We welcome communication from Aldous Huxley readers who may have or know of any additional material for MOKSHA.

Michael Horowitz

Cynthia Palmer

Foreword

AS AN AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER, I was flattered that Michael Horowitz and Cynthia Palmer wanted to use my picture of Aldous Huxley surveying Los Angeles from the Hollywood Hills on May 6, 1953. I had provided the mescaline and had been with him and his wife Maria when the doors of perception were cleansed. However, when it was suggested that I write a foreword to this new edition, I became uneasy. This book is an admirable selection of Aldous’s writings on a subject he had studied for many years and whose great importance he understood very well. Moksha is readable, enjoyable, and, best of all, browsable. One can nibble on its psychedelic pages, but what could I possibly add to what Aldous himself has written?

After some reflection, I realized that the frontispiece of this new edition gives me an opportunity to correct a curious error in Sybil Bedford’s splendid biography of Aldous. Readers of The Doors of Perception may recall a passage about the aesthetic and mystical experience the author has gazing at the fabric and folds of his gray flannel trousers while he is under the effects of the mescaline. Miss Bedford, on the testimony of a friend of the Huxleys, disputes the “gray flannel trousers” and replaces them with blue jeans. But, in fact, the original draft of Doors was a report to me, which included a description of the gray bags (pants), which were the informal dress of Englishmen of Aldous’s vintage. If you look at the picture I took that day, you can see those transformed trousers and judge for yourself.

Reminiscences of events nearly thirty years past are often misleading and sometimes self serving, but I still regret the lack of enterprise shown by those “saurians” of the Ford Foundation, as Aldous himself called them in a letter to me. He asked them to provide a very modest support for a project with psychedelics, which he, John Smythies, Abram Hoffer, and I hoped to pursue. Had they done as he wished, we would have acquired a better working knowledge of these remarkable substances during a period of relative calm, for in retrospect there is something to be said for the supposed dullness of the Eisenhower years.

We planned to introduce some very talented people to psychedelics in a leisurely way and to use their reports as a source of information for gauging the best and safest way for employing these tools of mind expansion. Since Aldous’s taste in human beings was so catholic, thanks to his longstanding interest in Jungian typology and his friendship with Dr. William Sheldon of somatotyping fame, we might have even recruited a few Ford executives and engineers. They could have explored the universe of automobiles: Who knows, they might have discovered that their wheeled creations are not indigenous to Detroit and could be built anywhere in the world. They might have even paid more attention to what the Japanese were doing, but the “saurians,” alas, were cautious, slow, short-sighted, and unimaginative in 1953.

Enough of hindsight and might-have-beens. What then? Aldous wrote so well and so much that even the best selections have gaps. As Samuel Johnson exclaimed when shown a volume called The Beauties of Shakespeare, “Pray sir, where are the other ten volumes?”

If nothing else, I can make certain that readers of this volume become acquainted with his brief, profound essay about human differences, wherein Aldous describes a walk he took in London about fifty years ago. Going down Arundel Street, he noticed that the Christian World was published at Number Seven, while the Feathered World was at Number Nine. He meditated on that great gulf that separates Christian from feathered folk, noting the chasm that divides members of different species. He then turned his attention to a single species—his own. Here are the last two hundred words or so of “A Meditation in Arundel Street”:

The gulf that separates the lover’s, say, or the musician’s world from the world of the chemist is deeper, more uncompromisingly unbridgeable than that which divides Anglo-Catholics from macaws or geese from Primitive Methodists. We cannot walk from one of these worlds into another; we can only jump. The last act of Don Giovanni is not deducible from electrons, or molecules, or even from cells and entire organs. In relation to these physical, chemical, and biological worlds it is simply a non sequitur. The whole of our universe is composed of a series of such non sequiturs. The only reason for supposing that there is in fact any connection between the logically and scientifically unrelated fragments of our experience is simply the fact that the experience is ours, that we have the fragments in our consciousness. These constellated worlds are all situated in the heaven of the human mind. Some day, conceivably, the scientific and logical engineers may build us convenient bridges from one world to another. Meanwhile we must be content to hop. Solvitur saltando. The only walking you can do in Arundel Street is along the pavements.

I first read this wonderful essay some years after his death, when his interest in the differences between human beings, about which he had often spoken, were beginning to preoccupy me. My colleagues and I are starting to build some of the bridges between those constellated worlds that are situated in the heaven of the human mind. We believe that among other instruments needed for these endeavors are psychedelics. Indeed I once called them “the mindcraft of the noösphere,” using the term developed by the philosopher-paleontologist, Teillard de Chardin, a great friend of Sir Julian Huxley, Aldous’s elder brother. Like spacecraft, mindcraft must be used with crews who are well trained, with ground staff of high ability, planning operations and monitoring progress. It is not just a matter of shooting off rocket capsules into space and hoping for the best. Aldous’s understanding of this is one of the major themes running through the selections of Moksha, a book I highly recommend for its profound insight into psychedelic and visionary experience.

Humphry Osmond

Preface

IN THE MID-1950s when Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell appeared, I found therein descriptions of experiences and the articulation of ideas which, since the discovery of LSD twelve years earlier, had constantly occupied my mind.

By that time scientific research along the broadest lines had already been carried out with LSD in medicine, biology, pharmacology, and psychiatry, and about one thousand papers had already been published. But it seemed to me a fundamental potentiality of this chemical agent had not yet been sufficiently considered or recognized, namely its ability to produce visionary experiences. I was therefore very pleased to learn that a person of such great literary and spiritual rank as Aldous Huxley, using mescaline which exhibits similar qualitative effects as LSD, had turned to a profound study of this phenomenon. Research on mescaline had been done as early as the turn of the century, but interest in this drug had afterwards largely diminished.

About the same time that Huxley carried out his experiments with mescaline, I held LSD sessions with the well-known German author Ernst Jünger in order to gain a more profound knowledge of the visionary experiences produced by the drug in the human mind. Ernst Jünger recorded his experiences in an essay entitled Besuch auf Godenholm (Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt a.M., 1952), which gives in literary form the essence of his interpretations. On the other hand, Aldous Huxley in the aforementioned books not only provides a masterly description of his encounter with mescaline, but also an evaluation of this type of drug from the highest spiritual and mental point of view, taking into account sociological, aesthetic, and philosophical aspects.

Aldous Huxley indeed advocated the use of certain drugs, which led some people who studied his works superficially, or not at all, to reproach him with being to a certain extent guilty for the rising wave of drug abuse, or even of being a drug addict himself. This accusation has of course no justifiable basis, as Huxley has only dealt with substances for which Humphry Osmond has created the term “psychedelic.” These are the psychotropic agents which had so far been denominated in scientific literature by the terms “phantastica,” “hallucinogens,” or “psychotomimetics.” These are not narcotic addiction-producing substances like the opiate heroin, or like cocaine, with their ruinous consequences for body and mind of which Huxley warned emphatically.

Psychotropic substances of plant origin had already been in use for thousands of years in Mexico as sacramental drugs in religious ceremonies and as magical potions having curative effects: The most important of these psychedelics are: mescaline, found in the peyotl cactus; psilocybin, which I have isolated from sacred Mexican mushrooms called teonanacatl; and, of course, LSD. Despite the fact that LSD (Lysergsäure-diäthylamid, lysergic acid diethylamide) is a semisynthetic substance which I have prepared in the laboratory from lysergic acid contained in ergot, a fungus growing on rye, from the viewpoint of its chemical constitution as well as its psychotropic mode of acting, it belongs to the group of Mexican sacramental drugs. This classification is further justified because we have found in another Mexican sacramental drug ololiuqui the active substances lysergic acid amide and lysergic acid hydroxyethylamide, which are, as the chemical terms express, very closely related to lysergic acid diethylamide.

Ololiuqui is the Aztec denomination for the seeds of certain morning glory species. LSD can be regarded as an ololiuqui drug raised to higher potency because, whereas the active dose of the ololiuqui constituent lysergic acid amide amounts to 2 mg (0.002 g), a similar effect can be produced with as little as 0.05–0.1 mg of LSD.

There are the profound consciousness-altering psychic effects of peyotl, teonanacatl, and ololiuqui which made the Indians of the Latin American countries so respectful and awestruck of these drugs, causing these people to place a taboo on them. Only a ritually clean person, one prepared by a period of prayer and fasting, had the right and qualification to ingest these drugs and then only in such a purified body as their divine nature could develop, whereas the impure felt themselves going insane or mortally stricken.

It was the endeavor of Aldous Huxley to show how the inward power of these sacramental drugs could be used for the welfare of people living in a technological society hostile to mystical revelations. The collected essays and lectures in the present volume will promote better understanding of these ideas. In Huxley’s view, the use of psychedelics should be part of a technique of “applied mysticism,” which he described to me in a letter of February 29, 1962 as

a technique for helping individuals to get the most out of their transcendental experience and to make use of their insights from the “other world” in the affairs of “this world.” Meister Eckhart wrote that “what is taken in by contemplation must be given out in love.” Essentially this is what must be developed—the art of giving out in love and intelligence what is taken in from vision and the experience of self-transcendence and solidarity with the universe.

In his last and most touching book, the utopian novel Island, Aldous Huxley describes the kind of cultural structure in which the psychedelics—in his narration called “moksha-medicine”—could be applied in a beneficial manner. Moksha is therefore a very appropriate title for the present book, for which we have to be very grateful to the editors.

Albert Hofmann

Burg i.L.

Switzerland

Introduction

MOKSHA Is A collection of Aldous Huxley’s writings taken largely from the last decade of his life. An appreciation of these addresses, essays and letters, and of the value he placed upon them, requires some introduction to the writer as well as to the written heritage he has left us. Aldous Leonard Huxley was born on July 26, 1894, into a notable literary and scientific family. He was the third son of Dr. Leonard Huxley—teacher, editor, man of letters—and of Julia Arnold, niece of the poet Matthew Arnold and sister of the novelist, Mrs. Humphrey Ward. He was the grandson of T. H. Huxley, the scientist, and the great-grandson of a formidable moralist, Dr. Thomas Arnold. His eldest brother, Julian, died February 21, 1975, ending that generation of world-recognized Huxleys.

Huxley’s own writings best document his transition from poet to novelist to mystic to essayist to scientist. At the age of sixteen a disastrous eye infection left Huxley substantially blind, putting an end to a hoped-for medical career. Forced to depend upon braille for reading, a guide for walking, and a typewriter for writing, he considered his disability irreversible, and his early poems such as The Defeat of Youth (1918) and Leda (1920) express bitterness. However, the title poem of The Cicadas (1931) shows a recovery from this morbidness, and in a storm of productivity Huxley turned from poetry to the novel, shocking the reading public with Chrome Yellow (1921), Antic Hay (1923), and Those Barren Leaves (1925). He was compared with two contemporary literary rebels, Noel Coward and Richard Aldington; however, whereas these latter attacked the middle class without suggestions for improvement, Huxley’s writings provided the seeds of constructive synthesis. In the collection of travel essays Jesting Pilate (1926) and his novel Time Must Have a Stop (1944), one can see the polish of phrase that was to become his signature, and catch glimpses of the philosophical concerns which were soon to command his attention.

Brave New World (1932) preceded George Orwell’s 1984 by some twenty years and is today perhaps the best-known work of Huxley. A disturbingly large number of his prophecies have been fulfilled. In this novel Huxley presents a panacea-drug called Soma (Christianity without tears, morality in a bottle) which must be contrasted with his later creation Moksha (a process of education and enlightenment).

Huxley’s view of the scientist, as one who bridges the disciplines of religion and philosophy with science, follows principles he had first laid down in Time Must Have a Stop. In this novel he carefully avoided extremes of commitment: he felt that in a quest for truth and understanding, to have no hypothesis would deny one a motive or reason for experimentation, whereas to construct too elaborate a hypothesis would result in finding out what one knows to be there and ignoring all the rest. His “minimum working hypothesis” assumes the existence of a Godhead or Ground, a transcendent and immanent selflessness, with which one must become identified through love and knowledge.

The meeting with Dr. Humphry Osmond in 1953, which provided the crucible for Huxley’s personal experiments in challenging this “minimum working hypothesis,” is the logical starting place for this present collection of writings. Mescaline, then a little-studied drug found in the dumpling cactus Anhalonium lewinii, was to serve as the catalyst for this experiment. Mescaline was first isolated from the plant in 1894 by Heffter, first synthesized by Spath in 1919, and pharmacologically explored by Rouhier and Beringer in the middle 1920s. Yet by the early 1950s, only clinical and physiological studies had been recorded concerning the effects of this drug; there had been no literary or humanistic inquiry.

The results of Huxley’s scientific-humanistic inquiry were profound and immediately apparent. The short-term consequences were the recording of the drug-induced experiences in The Doors of Perception (1954), and the elaboration upon these and their extrapolation to other consciousness phenomena in Heaven and Hell (1956). The longer term consequence of this experiment and the several that followed convinced Huxley of the soundness of his working hypothesis: that there was a Ground and it was the “everything that is happening everywhere in the universe,” or better, the awareness of this “everything.” He was fascinated by the potential in drugs such as mescaline, LSD, and psilocybin to provide a learning experience normally denied us within our educational system. His lectures, novels and essays repeated the theme of desperation and hope. In an article in Playboy (Nov. 1963) he expressed despair that “in a world of explosive population increase, of headlong, technological advance and of militant nationalism, the time at our disposal—for the discovery of new energy sources for overcoming our society’s psychological inertia—is strictly limited.” The hope, as expressed in his utopian fantasy Island (1962), is that “a substance akin to psilocybin could be used to potentiate the non-verbal education of adolescents and to remind adults that the real world is very different from the misshapen universe they have created for themselves by means of their culture-conditioned prejudices.”

In Island the concept of such a drug is developed with the introduction of a fungus, Moksha. From its name it is apparent that it is not the Soma presented in Brave New World; Moksha is derived from the Sanskrit word for “liberation” and Soma from the Greek for “body.” In this book Huxley again precipitated controversy ahead of his time with his description of the death process as a learning process, and one which may be enriched by the administration of psychedelic drugs. The sincerity of this concept is evident in his ultimate experiment, in which he received two small doses of LSD, one several hours before death and a second just prior to death. In the last moments, he was conscious and peaceful.

During the last decade of his life, Huxley was intentionally controversial, yet he was desperately sincere. It is impossible to guess what he would write today, some fifteen years later, following the extensive proselytization for the use of psychedelic drugs that occured in the late 1960s. There was an explosive usage at that time, often by people who had not prepared themselves for the experience or for the personal integration of its values. Whatever he might have written, Huxley’s role in literature and in the expression of the philosophy of consciousness expansion can never be denied.

Alexander T. Shulgin

Lafayette, California

“But he who contemplates the 3rd mantra of OM, i.e., views God as Himself, becomes illuminated and obtains moksha. Just as a serpent, relieved of its oldened skin, becomes new again, so the yogi who worships the 3rd mantra relieved of his mortal coil, of his sins and earthly weaknesses, and freed with his spiritual body to roam about throughout God’s Universe, enjoys the glory of the All-Pervading Omniscient Spirit, ever and evermore. The contemplation of the last mantra blesses him with moksha or immortality.”

From The Mandukyopanishat being The Exposition of OM

the Great Sacred Name of the Supreme Being in the Vedas.

Trans. Pandit Guru, Datta Vidyarthi,

Prof, of Psychical Sciences, Lahore. Lahore, 1893.

“Open your eyes again and look at Nataraja up there on the altar. Look closely. In his upper right hand, as you’ve already seen, he holds the drum that calls the world into existence and in his upper left hand he carries the destroying fire. Life and death, order and disintegration, impartially. But now look at Shiva’s other pair of hands. The lower right hand is raised and the palm is turned outwards. What does that gesture signify? It signifies, ‘Don’t be afraid; it’s All Right.’ But how can anyone in his senses fail to be afraid, when it’s so obvious that they’re all wrong? Nataraja has the answer. Look now at his lower left hand. He’s using it to point down at his feet. And what are his feet doing? Look closely and you’ll see that the right foot is planted squarely on a horrible little subhuman creature—the demon, Muyalaka. A dwarf, but immensely powerful in his malignity, Muyalaka is the embodiment of ignorance, the manifestation of greedy, possessive selfhood. Stamp on him, break his back! And that’s precisely what Nataraja is doing. Trampling the little monster down under his right foot. But notice that it isn’t at this trampling right foot that he points his finger; it’s at the left foot, the foot that, as he dances, he’s in the act of raising from the ground. And why does he point at it? Why? That lifted foot, that dancing defiance of the force of gravity—it’s the symbol of release, of Moksha, of liberation. Nataraja dances in all the worlds at once—in the world of physics and chemistry, in the world of ordinary, all-too-human experience, in the world finally of Suchness, of Mind, of the Clear Light… .”

From Aldous Huxley’s Island (1962)

The bronze sculpture of Nataraja is by Tamilnadu, 10th century, Chola Dynasty. Reproduced courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Anonymous Gift.

PRECOGNITION

1931

A Treatise on Drugs

ALDOUS HUXLEY

Phantastica, Louis Lewin’s epochal survey of psychoactive drugs used around the world, made its English-language appearance in 1931. Sometime that year—either in London where his first play The World of Light was produced, or on the French Riviera where he was writing Brave New World—Aldous Huxley came upon this “unpromising-looking treasure” and “read it from cover to cover with a passionate and growing interest” It appears likely that Lewin’s treatise served to introduce Huxley to the history of drugs and their effects, although 22 years would pass before he made the first experiment upon himself, with mescalin—and paid tribute to Lewin in the first line of the book resulting from that experiment. (There is no evidence to support Francis King’s assertion that Aleister Crowley introduced Huxley to mescalin in Berlin in the 1920s.) Huxley’s earliest printed text on drug-taking touches on themes he would return to again and again in his later work: the widespread and pervasive use of drugs, their importance in religious ceremony, man’s predilection for occasional vacations from the everyday world, the problem of addiction, the failure of prohibition, and drugs of the future.

THE OTHER DAY I discovered, dusty and neglected on one of the upper shelves of the local bookshop, a ponderous work by a German pharmacologist The price was not high; I paid and carried home the unpromising-looking treasure. It was a thick book, dense with matter and, in manner, a model of all that literary style should not be. Strictly, an unreadable book. Nevertheless, I read it from cover to cover with a passionate and growing interest. For this book was a kind of encyclopedia of drugs. Opium and its modern derivatives, morphia and heroin; cocaine and the Mexican peyotl; the hashish of India and the near East; the agaric of Siberia; the kawa of Polynesia; the betel of the East Indies; the now universal alcohol; the ether, the chloral, the veronal of the contemporary West—not one was omitted. By the time I had reached the last page, I knew something about the history, the geographical distribution, the mode of preparation and the physiological and psychological effects of all the delicious poisons, by means of which men have constructed, in the midst of an unfriendly world, their brief and precarious paradises.

The story of drug-taking constitutes one of the most curious and also, it seems to me, one of the most significant chapters in the natural history of human beings. Everywhere and at all times, men and women have sought, and duly found, the means of taking a holiday from the reality of their generally dull and often acutely unpleasant existence. A holiday out of space, out of time, in the eternity of sleep or ecstasy, in the heaven or the limbo of visionary phantasy. “Anywhere, anywhere out of the world.”

Drug-taking, it is significant, plays an important part in almost every primitive religion. The Persians and, before them, the Greeks and probably the ancient Hindus used alcohol to produce religious ecstasy; the Mexicans procured the beatific vision by eating a poisonous cactus; a toadstool filled the Shamans of Siberia with enthusiasm and endowed them with the gift of tongues. And so on. The devotional exercises of the later mystics are all designed to produce the drug’s miraculous effects by purely psychological means. How many of the current ideas of eternity, of heaven, of supernatural states are ultimately derived from the experiences of drug-takers?

Primitive man explored the pharmaceutical avenues of escape from the world with a truly astonishing thoroughness. Our ancestors left almost no natural stimulant, or hallucinant, or stupefacient, undiscovered. Necessity is the mother of invention; primitive man, like his civilised descendant, felt so urgent a need to escape occasionally from reality, that the invention of drugs was fairly forced upon him.

All existing drugs are treacherous and harmful. The heaven into which they usher their victims soon turns into a hell of sickness and moral degradation. They kill, first the soul, then, in a few years, the body. What is the remedy? “Prohibition,” answer all contemporary governments in chorus. But the results of prohibition are not encouraging. Men and women feel such an urgent need to take occasional holidays from reality, that they will do almost anything to procure the means of escape. The only justification for prohibition would be success; but it is not and, in the nature of things, cannot be successful. The way to prevent people from drinking too much alcohol, or becoming addicts to morphine or cocaine, is to give them an efficient but wholesome substitute for these delicious and (in the present imperfect world) necessary poisons. The man who invents such a substance will be counted among the greatest benefactors of suffering humanity.

1931

Wanted, A New Pleasure

ALDOUS HUXLEY

Living on the French Riviera and observing the mores of a hedonistic society for whom alcohol and cocaine were the drugs of choice, Huxley in this short essay—a spin-off from the writing of Brave New World—assumes a tone of playful irony in describing a “heavenly, world-transfiguring drug” that future scientists might create. The sensation nearest to the experience of the drug is the thrill of speed—meaning not, of course, some amphetamine-type reaction, but literally, fastness.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY SCIENCE discovered the technique of discovery, and our age is, in consequence, the age of inventions. Yes, the age of inventions; we are never tired of proclaiming the fact. The age of inventions—and yet nobody has succeeded in inventing a new pleasure.

It was in the course of a recent visit to that region which the Travel Agency advertisements describe as the particular home of pleasure—the French Riviera—that this curious and rather distressing fact first dawned on me. From the Italian frontier to the mountains of the Esterel, forty miles of Mediterranean coast have been turned into one vast ‘pleasure resort’ Or to be more accurate, they have been turned into one vast straggling suburb—the suburb of all Europe and the two Americas—punctuated here and there with urban nuclei, such as Men-tone, Nice, Antibes, Cannes. The French have a genius for elegance; but they are also endowed with a genius for ugliness. There are no suburbs in the world so hideous as those which surround French cities. The great Mediterranean banlieue of the Riviera is no exception to the rule. The chaotic squalor of this long bourgeois slum is happily unique. The towns are greatly superior, of course, to their connecting suburbs. A certain pleasingly and absurdly old-fashioned, gimcrack grandiosity adorns Monte Carlo; Nice is large, bright, and lively; Cannes, gravely pompous and as though conscious of its expensive smartness. And all of them are equipped with the most elaborate and costly apparatus for providing their guests with pleasure.

It was while disporting myself, or rather while trying to disport myself, in the midst of this apparatus, that I came to my depressing conclusion about the absence of new pleasures. The thought, I remember, occurred to me one dismal winter evening as I emerged from the Restaurant des Ambassadeurs at Cannes into one of those howling winds, half Alpine, half marine, which on certain days transform the Croisette and the Promenade des Anglais into the most painfully realistic imitations of Wuthering Heights. I suddenly realized that, so far as pleasures were concerned, we are no better off than the Romans or the Egyptians. Galileo and Newton, Faraday and Clerk Maxwell have lived, so far as human pleasures are concerned, in vain. The great joint-stock companies which control the modern pleasure industries can offer us nothing in any essential way different from the diversions which consuls offered to the Roman plebs or Trimalchio’s panders could prepare for the amusement of the bored and jaded rich in the age of Nero. And this is true in spite of the movies, the talkies, the gramophone, the radio, and all similar modern apparatus for the entertainment of humanity. These instruments, it is true, are all essentially modern; nothing like them has existed before. But because the machines are modern it does not follow that the entertainments which they reproduce and broadcast are also modern. They are not. All that these new machines do is to make accessible to a larger public the drama, pantomime, and music which have from time immemorial amused the leisures of humanity.

These mechanically reproduced entertainments are cheap and are therefore not encouraged in pleasure resorts, such as those on the Riviera, which exist for the sole purpose of making travellers part with the maximum amount of money in the minimum space of time. In these places drama, pantomime, and music are therefore provided in the original form, as they were provided to our ancestors, without the interposition of any mechanical go-between. The other pleasures of the resorts are no less traditional. Eating and drinking too much; looking at half or wholly naked ballerinas and acrobats in the hope of stimulating a jaded sexual appetite; dancing; playing games and watching games, preferably rather bloody and ferocious games; killing animals—these have always been the sports of the rich and, when they had the chance, of the poor also. No less traditional is that other strange amusement so characteristic of the Riviera—gambling. Gambling must be at least as old as money; much older, I should imagine—as old as human nature itself, or at any rate as old as boredom, as old as the craving for artificial excitement and factitious emotions.

Officially, this closes the list of pleasures provided by the Riviera entertainment industries. But it must not be forgotten that, for those who pay for them, all these pleasures are situated, so to speak, in a certain emotional field—in the pleasure-pain complex of snobbery. The fact of being able to buy admission to ‘exclusive’ (that is generally to say, expensive) places of entertainment gives most people a considerable satisfaction. They like to think of the poor and vulgar herd outside, just as, according to Tertullian and many other Fathers of the Church, the Blessed enjoy looking down from the balconies of Heaven on to the writhings of the Damned in the pit below. They like to feel, with a certain swelling of pride, that they are sitting among the elect, or that they are themselves the elect, whose names figure in the social columns of the Continental Daily Mail, or the Paris edition of the New York Herald. True, snobbery is often the source of excruciating pain. But it is no less the source of exquisite pleasures. These pleasures, I repeat, are liberally provided in all the resorts and constitute a kind of background to all the other pleasures.

Now all these pleasure-resort pleasures, including those of snobbery, are immemorially antique—variations, at the best, on traditional themes. We live in the age of inventions; but the professional discoverers have been unable to think of any wholly new way of pleasurably stimulating our senses or evoking agreeable emotional reactions.

But this, I went on to reflect, as I shouldered my way through the opposing gale on the Croisette, this is not, after all, so surprising. Our physiological make-up has remained very much what it was ten thousand years ago. True, there have been considerable changes in our mode of consciousness; at no time, it is obvious, are all the potentialities of the human psyche simultaneously realized; history is, among many other things, the record of the successive actualization, neglect, and reactualization in another context of different sets of these almost indefinitely numerous potentialities. But in spite of these changes (which it is customary to call, incorrectly, psychic evolution), the simple instinctive feelings to which, as well as to the senses, the purveyors of pleasure make their appeal, have remained remarkably stable. The task of the pleasure merchants is to provide a sort of Highest Common Denominator of entertainment that shall satisfy large numbers of men and women, irrespective of their psychological idiosyncrasies. Such an entertainment, it is obvious, must be very unspecialized. Its appeal must be to the simplest of shared human characteristics—to the physiological and psychological foundations of personality, not to personality itself. Now, the number of appeals that can be made to what I may call the Great Impersonalities common to all human beings is strictly limited—so strictly limited that, as it has turned out, our inventors have been unable hitherto to devise any new ones. (One doubtful example of a new pleasure exists; I shall speak of it later.) We are still content with the pleasures which charmed our ancestors in the Bronze Age. (Incidentally, there are good reasons for regarding our entertainments as intrinsically inferior to those of the Bronze Age. Modern pleasures are wholly secular and without the smallest cosmic significance; whereas the entertainments of the Bronze Age were mostly religious rites and were felt by those who participated in them to be pregnant with important meanings.)

So far as I can see, the only possible new pleasure would be one derived from the invention of a new drug—of a more efficient and less harmful substitute for alcohol and cocaine. If I were a millionaire, I should endow a band of research workers to look for the ideal intoxicant. If we could sniff or swallow something that would, for five or six hours each day, abolish our solitude as individuals, atone us with our fellows in a glowing exaltation of affection and make life in all its aspects seem not only worth living, but divinely beautiful and significant, and if this heavenly, world-transfiguring drug were of such a kind that we could wake up next morning with a clear head and an undamaged constitution—then, it seems to me, all our problems (and not merely the one small problem of discovering a novel pleasure) would be wholly solved and earth would become paradise.

The nearest approach to such a new drug—and how immeasurably remote it is from the ideal intoxicant!—is the drug of speed. Speed, it seems to me, provides the one genuinely modern pleasure. True, men have always enjoyed speed; but their enjoyment has been limited, until very recent times, by the capacities of the horse, whose maximum velocity is not much more than thirty miles an hour. Now thirty miles an hour on a horse feels very much faster than sixty miles an hour in a train or a hundred in an aeroplane. The train is too large and steady, the aeroplane too remote from stationary surroundings, to give the passengers a very intense sensation of speed. The automobile is sufficiently small and sufficiently near the ground to be able to compete, as an intoxicating speed-purveyor, with the galloping horse. The inebriating effects of speed are noticeable, on horseback, at about twenty miles an hour, in a car at about sixty. When the car has passed seventy-two, or thereabouts, one begins to feel an unprecedented sensation—a sensation which no man in the days of horses ever felt. It grows intenser with every increase of velocity. I myself have never travelled at much more than eighty miles an hour in a car; but those who have drunk a stronger brewage of this strange intoxicant tell me that new marvels await any one who has the opportunity of passing the hundred mark. At what point the pleasure turns into pain, I do not know. Long before the fantastic Daytona figures are reached, at any rate. Two hundred miles an hour must be absolute torture.

But in this, of course, speed is like all other pleasures; indulged in to excess, they become their opposites. Each particular pleasure has its corresponding particular pain, boredom, or disgust. The compensating drawback of too much speed-pleasure must be, I suppose, a horrible compound of intense physical discomfort and intense fear. No; if one must go in for excesses one would probably be better advised to be old-fashioned and stick to overeating.

1932

Soma

ALDOUS HUXLEY

In his futuristic novel Brave New World, a so-called “perfect drug” is commercially developed and marketed widely. Huxley called it soma after the oldest recorded drug, cited in the ancient Hindu scripture, the Rig-Veda, where it is regarded as an inebriating drink: “a very strong alcoholic beverage . . . obtained by fermentation of a plant and worshipped like the plant itself” (Lewin, Phantastica, p. 161). R. G. Wasson later attempted to show that the soma brew employed the psychoactive mushroom Amanita muscaria. In a 1960 interview, Huxley described the soma of his novel as “an imaginary drug” bearing no resemblance to mescalin or LSD, “with three different effects: euphoric, halluncinant, or sedative—an impossible combination.”

“WE HAVE THE World State now. And Ford’s Day celebrations, and Community Sings, and Solidarity Services.”

“Ford, how I hate them!” Bernard Marx was thinking.

“There was a thing called Heaven; but all the same they used to drink enormous quantities of alcohol.”

“Like meat, like so much meat.”

“There was a thing called the soul and a thing called immortality.”

“Do ask Henry where he got it.”

“But they used to take morphia and cocaine.”

“And what makes it worse, she thinks of herself as meat.”

“Two thousand pharmacologists and bio-chemists were subsidized in A.F. 178.”

“He does look glum,” said the Assistant Predestinator, pointing at Bernard Marx.

“Six years later it was being produced commercially. The perfect drug.”

“Lets bait him.”

“Euphoric, narcotic, pleasantly hallucinant.”

“Glum, Marx, glum.” The clap on the shoulder made him start, look up. It was that brute Henry Foster. “What you need is a gramme of soma”

“All the advantages of Christianity and alcohol; none of thek defects.”

“Ford, I should like to kill him!” But all he did was to say, “No, thank you,” and fend off the proffered tube of tablets.

“Take a holiday from reality whenever you like, and come back without so much as a headache or a mythology.”

“Take it,” insisted Henry Foster, “take it.”

“Stability was practically assured.”

“One cubic centimetre cures ten gloomy sentiments,” said the Assistant Predestinator, citing a piece of homely hypnopædic wisdom.

“It only remained to conquer old age.”

“Damn you, damn you!” shouted Bernard Marx.

“Hoity-toity.”

“Gonadal hormones, transfusion of young blood, magnesium salts…”

“And do remember that a gramme is better than a damn.” They went out, laughing.

“All the physiological stigmata of old age have been abolished. And along with them, of course…”

“Don’t forget to ask him about that Malthusian belt,” said Fanny.

“Along with them all the old man’s mental peculiarities. Characters remain constant throughout a whole lifetime.”

“… two rounds of Obstacle Golf to get through before dark. I must fly.”

“Work, play—at sixty our powers and tastes are what they were at seventeen. Old men in the bad old days used to renounce, retire, take to religion, spend their time reading, thinking—thinking!”

“Idiots, swine!” Bernard Marx was saying to himself, as he walked down the corridor to the lift.

“Now—such is progress—the old men work, the old men copulate, the old men have no time, no leisure from pleasure, not a moment to sit down and think—or if ever by some unlucky chance such a crevice of time should yawn in the solid substance of their distractions, there is always soma, delicious soma, half a gramme for half-holiday, a gramme for a week-end, two grammes for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon; returning whence they find themselves on the other side of the crevice, safe on the solid ground of daily labour and distraction, scampering from feely to feely, from girl to pneumatic girl, from Electro-magnetic Gold Course to…”

… The group was now complete, the solidarity circle perfect and without flaw. Man, woman, man, in a ring of endless alternation round the table. Twelve of them ready to be made one, waiting to come together, to be fused, to lose their twelve separate identities in a larger being.

The President stood up, made the sign of the T and, switching on the synthetic music, let loose the soft indefatigable beating of drums and a choir of instruments—near-wind and super-string—that plangently repeated and repeated the brief and unescapably haunting melody of the first Solidarity Hymn. Again, again—and it was not the ear that heard the pulsing rhythm, it was the midriff; the wail and clang of those recurring harmonies haunted, not the mind, but the yearning bowels of compassion.

The President made another sign of the T and sat down. The service had begun. The dedicated soma tablets were placed in the centre of the dinner table. The loving cup of strawberry ice-cream soma was passed from hand to hand and, with the formula, “I drink to my annihilation,” twelves times quaffed. Then to the accompaniment of the synthetic orchestra the First Solidarity Hymn was sung.

Ford, we are twelve; oh, make us one,

Like drops within the Social River;

Oh, make us now together run

As swiftly as thy shining Flivver.

Twelve yearning stanzas. And then the loving cup was passed a second time. “I drink to the Greater Being” was now the formula. All drank. Tirelessly the music played. The drums beat. The crying and clashing of the harmonies were an obsession in the melted bowels. The Second Solidarity Hymn was sung.

Come, Greater Being, Social Friend,

Annihilating Twelve-in-One!

We long to die, for when we end,

Our larger life has but begun.

Again twelve stanzas. By this time the soma had begun to work. Eyes shone, cheeks were flushed, the inner light of universal benevolence broke out on every face in happy, friendly smiles. Even Bernard felt himself a little melted. When Morgana Rothschild turned and beamed at him, he did his best to beam back. But the eyebrow, that black two-in-one—alas, it was still there; he couldn’t ignore it, couldn’t however hard he tried. The melting hadn’t gone far enough. Perhaps if he had been sitting between Fifi and Joanna… . For the third time the loving cup went round. “I drink to the imminence of His Coming,” said Morgana Rothschild, whose turn it happened to be to initiate the circular rite. Her tone was loud, exultant. She drank and passed the cup to Bernard. “I drink to the imminence of His Coming,” he repeated, with a sincere attempt to feel that the coming was imminent; but the eyebrow continued to haunt him, and the Coming, so far as he was concerned, was horribly remote. He drank and handed the cup to Clara Deterding. “It’ll be a failure again,” he said to himself. “I know it will.” But he went on doing his best to beam.

The loving cup had made its circuit. Lifting his hand, the President gave a signal; the chorus broke out into the third Solidarity Hymn.

Feel how the Greater Being comes!

Rejoice and, in rejoicings, die!

Melt in the music of the drums!

For I am you and you are I.

1936

Propaganda And Pharmacology

ALDOUS HUXLEY

Brainwashing was a subject to which Huxley returned again and again. The rise of Fascism in the 1930s occasioned a long essay from his pen, “Writers and Readers,” which includes a passage on the latest chemical methods of mind-rape. Even after his positive experiences with psychedelic substances two decades later, he continued to warn against the phenomenon of “pharmacological attack.”

… THE PROPAGANDISTS of the future will probably be chemists and physiologists as well as writers. A cachet containing three-quarters of a gramme of chloral and three-quarters of a milligram of scopolamine will produce in the person who swallows it a state of complete psychological malleability, akin to the state of a subject under deep hypnosis. Any suggestion made to the patient while in this artificially induced trance penetrates to the very depths of the sub-conscious mind and may produce a permanent modification in the habitual modes of thought and feeling. In France, where the technique has been in experimental use for several years, it has been found that two or three courses of suggestion under chloral and scopolamine can change the habits even of the victims of alcohol and irrepressible sexual addictions. A peculiarity of the drug is that the amnesia which follows it is retrospective; the patient has no memories of a period which begins several hours before the drug’s administrations. Catch a man unawares and give him a cachet; he will return to consciousness firmly believing all the suggestions you have made during his stupor and wholly unaware of the way this astonishing conversion has been effected. A system of propaganda, combining pharmacology with literature, should be completely and infallibly effective. The thought is extremely disquieting… .

1944

A Boundless Absence

ALDOUS HUXLEY

Huxley’s novel Time Must Have a Stop contains a remarkable and prophetic description of a post-death state that strongly resembles ego-annihilation under a moderate to strong psychedelic.

THERE WAS NO pain any longer, no more need to gasp for breath, and the tiled floor of the lavatory had ceased to be cold and hard.

All sound had died away, and it was quite dark. But in the void and the silence there was still a kind of knowledge, a faint awareness.

Awareness not of a name or person, not of things present, not of memories of the past, not even of here or there—for there was no place, only an existence whose single dimension was this knowledge of being ownerless and without possessions and alone.

The awareness knew only itself, and itself only as the absence of something else.

Knowledge reached out into the absence that was its object. Reached out into the darkness, further and further. Reached out into the silence. Illimitably. There were no bounds.

The knowledge knew itself as a boundless absence within another boundless absence, which was not even aware.

It was the knowledge of an absence ever more total, more excruciatingly a privation. And it was aware with a kind of growing hunger, but a hunger for something that did not exist; for the knowledge was only of absence, of pure and absolute absence.

Absence endured through ever-lengthening durations. Durations of restlessness. Durations of hunger. Durations that expanded and expanded as the frenzy of insatiability became more and more intense, that lengthened out into eternities of despair.

Eternities of the insatiable, despairing knowledge of absence within absence, everywhere, always, in an existence of only one dimension… .

And then abruptly there was another dimension, and the everlasting ceased to be the everlasting.

That within which the awareness of absence knew itself, that by which it was included and interpenetrated, was no longer an absence, but had become the presence of another awareness. The awareness of absence knew itself known.

In the dark silence, in the void of all sensation, something began to know it. Very dimly at first, from immeasurably far away. But gradually the presence approached. The dimness of that other knowledge grew brighter. And suddenly the awareness had become an awareness of light. The light of the knowledge by which it was known.

In the awareness that there was something other than absence the anxiety found appeasement, the hunger found satisfaction.

Instead of privation there was this light. There was this knowledge of being known. And this knowledge of being known was a satisfied, even a joyful knowledge.

Yes, there was joy in being known, in being thus included within a shining presence, in thus being interpenetrated by a shining presepce.

And because the awareness was included by it, interpenetrated by it, there was identification with it. The awareness was not only known by it but knew with its knowledge.

Knew, not absence, but the luminous denial of absence, not privation, but bliss.

There was hunger still. Hunger for yet more knowledge of a yet more total denial of an absence.

Hunger, but also the satisfaction of hunger, also bliss. And then as the light increased, hunger again for profounder satisfactions, for a bliss more intense.

Bliss and hunger, hunger and bliss. And through everlengthening durations the light kept brightening from beauty into beauty. And the joy of knowing, the joy of being known, increased with every increment of that embracing and interpenetrating beauty.

Brighter, brighter, through succeeding durations, that expanded at last into an eternity of joy.

An eternity of radiant knowledge, of bliss unchanging in its ultimate intensity. For ever, for ever.

But gradually the unchanging began to change.

The light increased its brightness. The presence became more urgent. The knowledge more exhaustive and complete.

Under the impact of that intensification, the joyful awareness of being known, the joyful participation in that knowledge, was pinned against the limits of its bliss. Pinned with an increasing pressure until at last the limits began to give way and the awareness found itself beyond them, in another existence. An existence where the knowledge of being included within a shining presence had become a knowledge of being oppressed by an excess of light. Where that transfiguring interpenetration was apprehended as a force disruptive from within. Where the knowledge was so penetratingly luminous that the participation in it was beyond the capacity of that which participated.

The presence approached, the light grew brighter.

Where there had been eternal bliss there was an immensely prolonged uneasiness, an immensely prolonged duration of pain and, longer and yet longer, as the pain increased, durations of intolerable anguish. The anguish of being forced, by participation, to know more than it was possible for the participant to know. The anguish of being crushed by the pressure of too much light—crushed into ever-increasing density and opacity. The anguish, simultaneously, of being broken and pulverized by the thrust of that interpenetrating knowledge from within. Disintegrated into smaller and smaller fragments, into mere dust, into atoms of mere nonentity.

And this dust and the ever-increasing denseness of that opacity were apprehended by the knowledge in which there was participation as being hideous. Were judged and found repulsive, a privation of all beauty and reality.

Inexorably, the presence approached, the light grew brighter.

And with every increase of urgency, every intensification of that invading knowledge from without, that disruptive brightness thrusting from within, the agony increased, the dust and the compacted darkness became more shameful, were known, by participation, as the most hideous of absences.

Shameful everlastingly in an eternity of shame and pain.

But the light grew brighter, agonizingly brighter.

The whole of existence was brightness—everything except this one small clot of untransparent absence, except these dispersed atoms of a nothingness that, by direct awareness, knew itself as opaque and separate, and at the same time, by an excruciating participation in the light knew itself as the most hideous and shameful of privations.

Brightness beyond the limits of the possible, and then a yet intenser, nearer incandescence, pressing from without, disintegrating from within. And at the same time there was this other knowledge, ever more penetrating and complete, as the light grew brighter, of a clotting and a disintegration that seemed progressively more shameful as the durations lengthened out interminably.

There was no escape, an eternity of no escape. And through ever longer, through ever-decelerating durations, from impossible to impossible, the brightness increased, came more urgently and agonizingly close.

Suddenly there was a new contingent knowledge, a conditional awareness that, if there were no participation in the brightness, half the agony would disappear. There would be no perception of the ugliness of this clotted or disintegrated privation. There would only be an untransparent separateness, self-known as other than the invading light.

An unhappy dust of nothingness, a poor little harmless clot of mere privation, crushed from without, scattered from within, but still resisting, still refusing, in spite of the anguish, to give up its right to a separate existence.

Abruptly, there was a new and overwhelming flash of participation in the light, in the agonizing knowledge that there was no such right as a right to separate existence, that this clotted and disintegrated absence was shameful and must be denied, must be annihilated—held up unflinchingly to the radiance of that invading knowledge and utterly annihilated, dissolved in the beauty of that impossible in candescence.

For an immense duration the two awarenesses hung as though balanced—the knowledge that knew itself separate, knew its own right to separateness, and the knowledge that knew the shamefulness of absence and the necessity for its agonizing annihilation in the light.

As though balanced, as though on a knife-edge between an impossible intensity of beauty and an impossible intensity of pain and shame, between a hunger for opacity and separateness and absence and a hunger for a yet more total participation in the brightness.

And then, after an eternity, there was a renewal of that contingent and conditional knowledge: “If there were no participation in the brightness, if there were no participation… .”

And all at once there was no longer any participation. There was a self-knowledge of the clot and the disintegrated dust; and the light that knew these things was another knowledge. There was still the agonizing invasion from within and without, but no shame any more, only a resistance to attack, a defense of rights.

By degrees the brightness began to lose some of its intensity, to recede, as it were, to grow less urgent. And suddenly there was a kind of eclipse. Between the insufferable light and the suffering awareness of the light as a presence alien to this clotted and disintegrated privation, something abruptly intervened. Something in the nature of an image, something partaking of a memory.

An image of things, a memory of things. Things related to things in some blessedly familiar way that could not yet be clearly apprehended.

Almost completely eclipsed, the light lingered faintly and insignificantly on the fringes of awareness. At the centre were only things.

Things still unrecognized, not fully imagined or remembered, without name or even form, but definitely there, definitely opaque.

And now that the light had gone into eclipse and there was no participation, opacity was no more shameful. Density was happily aware of density, nothingness of untransparent nothingness. The knowledge was without bliss, but profoundly reassuring.

And gradually the knowledge became clearer and the things known, more definite and familiar. More and more familiar, until awareness hovered on the verge of recognition.

A clotted thing here, a disintegrated thing there. But what things? And what were these corresponding opacities by which they were being known?

There was a vast duration of uncertainty, a long, long groping in a chaos of unmanifested possibilities.

Then abruptly it was Eustace Barnack who was aware. Yes, this opacity was Eustace Barnack, this dance of agitated dust was Eustace Barnack. And the clot outside himself, this other opacity of which he had the image, was his cigar. He was remembering his Romeo and Juliet as it had slowly disintegrated into blue nothingness between his fingers. And with the memory of the cigar came the memory of a phrase: “Backwards and downwards.” And then the memory of laughter.

Words in what context? Laughter at whose expense? There was no answer. Just “backwards and downwards” and that stump of disintegrating opacity. “Backwards and downwards,” and then the cachinnation, and the sudden glory.

Far off, beyond the image of that brown slobbered cylinder of tobacco, beyond the repetition of those three words and the accompanying laughter the brightness lingered, like a menace. But in his joy at having found again this memory of things, this knowledge of an identity remembering, Eustace Barnack had all but ceased to be aware of its existence.

1952

Downward Transcendence

ALDOUS HUXLEY

In an epilogue to The Devils of Loudun, his historical account of mass hysteria and exorcism in a 17th-century French convent, Huxley drew on the ideas of Philippe de Félice in Foules en Delire, Ecstases Collectives, that there were three kinds of self-transcendence: downward, upward, and horizontal. Drug-taking, elemental sexuality, and herd poisoning were avenues toward the first category. Chemical methods of self-transcendence gave at best only momentary revelation and at considerable cost. After taking mescalin, however, he wrote (to Osmond) of his belief that this drug “can be used to raise the horizontal self-transcendence which goes on within purposive groups … so that it becomes an upward transcendence… .”

WITHOUT AN UNDERSTANDING of man’s deep-seated urge to self-transcendence, of his very natural reluctance to take the hard, ascending way, and his search for some bogus liberation either below or to one side of his personality, we cannot hope to make sense of our own particular period of history or indeed of history in general, of life as it was lived in the past and as it is lived today. For this reason I propose to discuss some of the more common Grace-substitutes, into which and by means of which men and women have tried to escape from the tormenting consciousness of being merely themselves.

In France there is now one retailer of alcohol to every hundred inhabitants, more or less. In the United States there are probably at least a million desperate alcoholics, besides a much larger number of very heavy drinkers whose disease has not yet become mortal. Regarding the consumption of intoxicants in the past we have no precise or statistical knowledge. In Western Europe, among the Celts and Teutons, and throughout medieval and early modern times, the individual intake of alcohol was probably even greater than it is today. On the many occasions when we drink tea, or coffee, or soda pop, our ancestors refreshed themselves with wine, beer, mead and, in later centuries, with gin, brandy and usquebaugh. The regular drinking of water was a penance imposed on wrongdoers, or accepted by the religious, along with occasional vegetarianism, as a very severe mortification. Not to drink an intoxicant was an eccentricity sufficiently remarkable to call for comment and the using of a more or less disparaging nickname. Hence such patronymics as the Italian Bevilacqua, the French Boileau and the English Drinkwater.

Alcohol is but one of the many drugs employed by human beings as avenues of escape from the insulated self. Of the natural narcotics, stimulants and hallucinators there is, I believe, not a single one whose properties have not been known from time immemorial. Modern research has given us a host of brand new synthetics; but in regard to the natural poisons it has merely developed better methods of extracting, concentrating and recombining those already known. From poppy to curare, from Andean coca to Indian hemp and Siberian agaric, every plant or bush or fungus capable, when ingested, of stupefying or exciting or evoking visions, has long since been discovered and systematically employed. The fact is strangely significant; for it seems to prove that, always and everywhere, human beings have felt the radical inadequacy of their personal existence, the misery of being their insulated selves and not something else, something wider, something in Wordsworthian phrase, “far more deeply interfused.” Exploring the world around him, primitive man evidently “tried all things and held fast to that which was good.” For the purpose of self-preservation the good is every edible fruit and leaf, every wholesome seed, root and nut. But in another context—the context of self-dissatisfaction and the urge to self-transcendence—the good is everything in nature by means of which the quality of individual consciousness can be changed. Such drug-induced changes may be manifestly for the worse, may be at the price of present discomfort and future addiction, degeneration and premature death. All this is of no moment. What matters is the awareness, if only for an hour or two, if only for a few minutes, of being someone or, more often, something other than the insulated self. “I live, yet not I, but wine or opium or peyotl or hashish liveth in me.” To go beyond the limits of the insulated ego is such a liberation that, even when self-transcendence is through nausea into frenzy, through cramps into hallucinations and coma, the drug-induced experience has been regarded by primitives and even by the highly civilized as intrinsically divine. Ecstasy through intoxication is still an essential part of the religion of many African, South American and Polynesian peoples. It was once, as the surviving documents clearly prove, a no less essential part of the religion of the Celts, the Teutons, the Greeks, the peoples of the Middle East and the Aryan conquerors of India. It is not merely that “beer does more than Milton can to justify God’s ways to man.” Beer is the god. Among the Celts, Sabazius was the devine name given to the felt alienation of being dead drunk on ale. Further to the south, Dionysos was, among other things, the supernatural objectification of the psychophysical effects of too much wine. In Vedic mythology, Indra was the god of that now unidentifiable drug called soma. Hero, slayer of dragons, he was the magnified projection upon heaven of the strange and glorious otherness experienced by the intoxicated. Made one with the drug, he becomes, as Soma-Indra, the source of immortality, the mediator between the human and the divine.

In modern times beer and the other toxic short cuts to self-transcendence are no longer officially worshipped as gods. Theory has undergone a change, but not practice; for in practice millions upon millions of civilized men and women continue to pay their devotions, not to the liberating and transfiguring Spirit, but to alcohol, to hashish, to opium and its derivatives, to the barbiturates, and the other synthetic additions to the age-old catalogue of poisons capable of causing self-transcendence. In every case, of course, what seems a god is actually a devil, what seems a liberation is in fact an enslavement. The self-transcendence is invariably downward into the less than human, the lower than personal…

To what extent, and in what circumstances, it is possible for a man to make use of the descending road as a way to spiritual self-transcendence? At first sight it would seem obvious that the way down is not and can never be the way up. But in the realm of existence matters are not quite so simple as they are in our beautifully tidy world of words. In actual life a downward movement may sometimes be made the beginning of an ascent. When the shell of the ego has been cracked and there begins to be a consciousness of the subliminal and physiological othernesses underlying personality, it sometimes happens that we catch a glimpse, fleeting but apocalyptic, of that other Otherness, which is the Ground of all being. So long as we are confined within our insulated selfhood, we remain unaware of the various not-selves with which we are associated—the organic not-self, the subconscious not-self, the collective not-self of the psychic medium in which all our thinking and feeling have their existence, and the immanent and transcendent not-self of the Spirit. Any escape, even by a descending road, out of insulated selfhood makes possible at least a momentary awareness of the not-self on every level, including the highest. William James, in his Varieties of Religious Experience, gives instances of “anaesthetic revelations,”1 following the inhalation of laughing gas. Similar theophanies are sometimes experienced by alcoholics, and there are probably moments in the course of intoxication by almost any drug, when awareness of a not-self superior to the disintegrating ego becomes briefly possible. But these occasional flashes of revelation are bought at an enormous price. For the drug-taker, the moment of spiritual awareness (if it comes at all) gives place very soon to subhuman stupor, frenzy or hallucination, followed by dismal hangovers and, in the long run, by a permanent and fatal impairment of bodily health and mental power. Very occasionally a single “anaesthetic revelation” may act, like any other theophany, to incite its recipient to an effort of self-transformation and upward self-transcendence. But the fact that such a thing sometimes happens can never justify the employment of chemical methods of self-transcendence. This is a descending road and most of those who take it will come to a state of degradation, where periods of subhuman ecstasy alternate with periods of conscious selfhood so wretched that any escape, even if it be into the slow suicide of drug addiction, will seem preferable to being a person.

PSYCHEDELIC AND VISIONARY EXPERIENCE

1953

Letters

Dr. Humphry Osmond was a research psychiatrist studying the relationship between the mescalin experience and schizophrenia at the University of Saskatchewan when he and Huxley first met. Huxley’s invitation to Dr. Osmond and his anticipation of taking mescalin are documented in the following letters.

TO DR. HUMPHRY OSMOND [SMITH 623]

740 N. Kings Rd.,

Los Angeles 46, Cal.

10 April, 1953

DEAR DR. OSMOND,

Thank you for your interesting letter and accompanying article, and for the very kind and understanding things you say of my Devils. It looks as though the most satisfactory working hypothesis about the human mind must follow, to some extent, the Bergsonian model, in which the brain with its associated normal self, acts as a utilitarian device for limiting, and making selections from, the enormous possible world of consciousness, and for canalizing experience into biologically profitable channels. Disease, mescaline, emotional shock, aesthetic experience and mystical enlightenment have the power, each in its different way and in varying degrees, to inhibit the functions of the normal self and its ordinary brain activity, thus permitting the “other world” to rise into consciousness. The basic problem of education is, How to make the best of both worlds-the world of biological utility and common sense, and the world of unlimited experience underlying it. I suspect that the complete solution of the problem can come only to those who have learned to establish themselves in the third and ultimate world of ‘the spirit’, the world which subtends and interpenetrates both of the other worlds. But short of this ultimate solution, there may be partial solutions, by means of which the growing child may be taught to preserve his “intimations of immortality” into adult life. Under the current dispensation the vast majority of individuals lose, in the course of education, all the openness to inspiration, all the capacity to be aware of other things than those enumerated in the Sears-Roebuck catalogue which constitutes the conventionally “real” world. That this is not the necessary and inevitable price extorted for biological survival and civilized efficiency is demonstrated by the existence of the few men and women who retain their contact with the other world, even while going about their business in this. Is it too much to hope that a system of education may some day be devised, which shall give results, in terms of human development, commensurate with the time, money, energy and devotion expended? In such a system of education it may be that mescaline or some other chemical substance may play a part by making it possible for young people to ‘taste and see’ what they have learned about at second hand, or directly but at a lower level of intensity, in the writings of the religious, or the works of poets, painters and musicians.

I hope very much that there may be a chance of seeing you in these parts during the Psychiatric Congress in May. One of the oddest fish you will meet at the congress will be a friend of ours, Dr. [—], who is perhaps the greatest living virtuoso in hypnosis. (Incidentally, for some people at least, deep hypnotic trance is a way that leads into the other world—a less dramatic way than that of mescaline inasmuch as the experiences are entirely inward and do not associate themselves with sensory perceptions and the character of things and people ‘out there’ but still very definitely a way.) If you are coming along to the meeting, we can provide a bed and bath—but unfortunately the accommodation is too small for more than one. You will be free to come and go as it suits you, and there will always be something to eat—though it may be a bit sketchy on the days when we don’t have a cook. In any case I look forward to seeing you and to the opportunity of discussing at greater length some of the problems raised in your letter and the articles by Dr. Smythies and yourself.

Yours sincerely,

Aldous Huxley

740 N. Kings Rd.,

L A 46, Cal.

19 April, 1953

DEAR DR. OSMOND,

Good! We shall expect you on the third. May I suggest that you take the air line bus to the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, from which we can come and retrieve you—or from which it is easy to take a cab. Going to meet planes at the air port has become such a nightmare, with the increase of traffic, that my wife, who drives the car, begs everyone to come as far as the Roosevelt—which is quicker for the traveller as well as easier for the meeter.

Hoffmann La Roche has told my young doctor friend that they must send to Switzerland for a supply of mescaline—so it may be weeks before it get here. Meanwhile do you have any of the stuff on hand? If so I hope you can bring a little; for I am eager to make the experiment and would feel particularly happy to do so under the supervision of an experienced investigator like yourself.

Yours very sincerely,

Aldous Huxley

1953

May Morning In Hollywood

DR. HUMPHRY OSMOND

Here Dr. Osmond recounts “that improbable journey” that took him to Los Angeles with a dose (0.4 g) of mescalin for Huxley, whom he guided on the trip immortalized in Doors of Perception. The classic anxieties of the guide are humorously expressed: though Aldous “seemed like an ideal subject,” Osmond momentarily feared he would become known as “the man who drove Aldous Huxley mad” Osmond remained one of Huxley’s closest friends during his last decade; many of Huxley’s most important letters pertaining to psychedelics are addressed to him.