| Family XV. FRINGILLINAE. FINCHES. GENUS XII. CORYTHUS, Cuv. PINE-FINCH. |

Next >> |

Family |

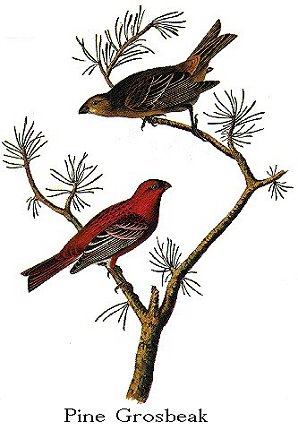

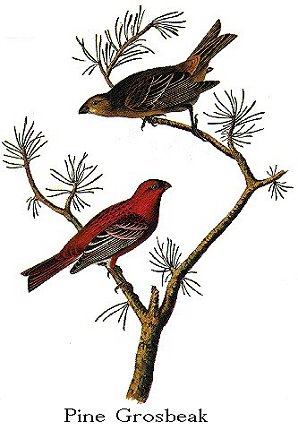

PINE GROSBEAK. [Pine Grosbeak.] |

| Genus | CORYTHUS ENUCLEATOR, Linn. [Pinicola enucleator.] |

In WILSON'S time, this beautiful bird was rare in Pennsylvania; but since

then it has occasionally been seen in considerable numbers, and in the winter of

1836, my young friend J. TRUDEAU, M. D., procured several in the vicinity of

Philadelphia. That season also they were abundant in the States of New York and

Massachusetts. Some have been procured near the mouth of the Big Guyandotte on

the Ohio; and Mr. NUTTALL has observed it on the lower parts of the Missouri. I

have ascertained it to be a constant resident in the State of Maine, and have

met with it on several islands in the Bay of Fundy, as well as in Newfoundland

and Labrador. Dr. RICHARDSON mentions it as having been observed by the

Expedition in the 50th parallel, and as a constant resident at Hudson's Bay. It

is indeed the hardiest bird of its tribe yet discovered in North America, where

even the Rose-breasted Grosbeak, though found during summer in Newfoundland and

Labrador, removes in autumn to countries farther south than the Texas, where as

late as the middle of May I saw many in their richest plumage.

The Pine Grosbeak is a charming songster. Well do I remember how delighted

I felt, while lying on the moss-clad rocks of Newfoundland, near St. George's

Bay, I listened to its continuous lay, so late as the middle of August,

particularly about sunset. I was reminded of the pleasure I had formerly

enjoyed on the banks of the clear Mohawk, under nearly similar circumstances,

when lending an attentive ear to the mellow notes of another Grosbeak. But,

reader, at Newfoundland I was still farther removed from my beloved family; the

scenery around was thrice wilder and more magnificent. The stupendous dark

granite rocks, fronting the north, as if bidding defiance to the wintry

tempests, brought a chillness to my heart, as I thought of the hardships endured

by those intrepid travellers who, for the advancement of science, had braved the

horrors of the polar winter. The glowing tints of the western sky, and the

brightening stars twinkling over the waters of the great Gulf, rivetted me to

the spot, and the longer I gazed, the more I wished to remain; but darkness was

suddenly produced by the advance of a mass of damp fog, the bird ceased its

song, and all around seemed transformed into chaos. Silently I groped my way

to the beach, and soon reached the Ripley.

The young gentlemen of my party, accompanied by my son JOHN WOODHOUSE, and

a Newfoundland Indian, had gone into the interior in search of Rein Deer, but

returned the following afternoon, having found the flies and musquitoes

intolerable. My son brought a number of Pine Grosbeaks, of different sexes,

young and adult, but all the latter in moult, and patched with dark red, ash,

black and white. It was curious to see how covered with sores the legs of the

old birds of both sexes were. These sores or excrescences are, I believe,

produced by the resinous matter of the fir-trees on which they obtain their

food. Some specimens had the hinder part of the tarsi more than double the

usual size, the excrescences could not be removed by the hand, and I was

surprised that the birds had not found means of ridding themselves of such an

inconvenience. One of the figures in my plate represents the form of these

sores.

I was assured that during mild winters, the Pine Grosbeak is found in the

forests of Newfoundland in considerable numbers, and that some remain during the

most severe cold. A lady who had resided there many years, and who was fond of

birds, assured me that she had kept several males in cages; that they soon

became familiar, would sing during the night, and fed on all sorts of fruits and

berries during the summer, and on seeds of various kinds in winter; that they

were fond of bathing, but liable to cramps; and that they died of sores produced

around their eyes and the base of the upper mandible. I have observed the same

to happen to the Cardinal and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks.

The flight of this bird is undulating and smooth, performed in a direct

line when it is migrating, at a considerable height above the forests, and in

groups of from five to ten individuals. They alight frequently during the day,

on such trees as are opening their buds or blossoms. At such times they are

extremely gentle, and easily approached, are extremely fond of bathing, and

whether on the ground or on branches, move by short leaps. I have been much

surprised to see, on my having fired, those that were untouched, fly directly

towards me, until within a few feet, and then slide off and alight on the lower

branches of the nearest tree, where, standing as erect as little Hawks, they

gazed upon me as if I were an object quite new, and of whose nature they were

ignorant. They are easily caught under snow-shoes put up with a figure of four,

around the wood-cutters' camps in the State of Maine, and are said to afford

good eating. Their food consists of the buds and seeds of almost all sorts of

trees. Occasionally also they seize a passing insect. I once knew one of these

sweet songsters, which, in the evening, as soon as the lamp was lighted in the

room where its cage was hung, would instantly tune its voice anew.

My kind friend THOMAS M'CULLOCH Of Pictou in Nova Scotia, has sent me the

following notice, which I trust will prove as interesting to you as it has been

to me. Last winter the snow was exceedingly deep, and the storms so frequent

and violent that many birds must have perished in consequence of the scarcity of

food. The Pine Grosbeaks being driven from the woods, collected about the barns

in great numbers, and even in the streets of Pictou they frequently alighted in

search of food. A pair of these birds which had been recently taken were

brought me by a friend, but they were in such a poor emaciated condition, that I

almost despaired of being able to preserve them alive. Being anxious, however,

to note for you the changes of their plumage, I determined to make the attempt;

but notwithstanding all my care, they died a few days after they came into my

possession. Shortly after, I received a male in splendid plumage, but so

emaciated that he seemed little else than a mass of feathers. By more cautious

feeding, however, he soon regained his flesh and became so tame as to eat from

my hand without the least appearance of fear. To reconcile him gradually to

confinement, he was permitted to fly about my bedroom, and upon rising in the

morning, the first thing I did was to give him a small quantity of seed. But

three mornings in succession I happened to lie rather later than usual, and each

morning I was aroused by the bird fluttering upon my shoulder, and calling for

his usual allowance. The third morning, I allowed him to flutter about me some

time before shewing any symptom of being awake, but he no sooner observed that

his object was effected than he retired to the window and waited patiently until

I arose. As the spring approached, he used to whistle occasionally in the

morning, and his notes, like those of his relative the Rose-breasted Grosbeak,

were exceedingly rich and full. About the time, however, when the species began

to remove to the north, his former familiarity entirely disappeared. During the

day he never rested a moment, but continued to run from one side of the window

to the other, seeking a way of escape, and frequently during the night, when the

moonlight would fall upon the window, I was awakened by him dashing against the

glass. The desire of liberty seemed at last to absorb every other feeling, and

during four days I could not detect the least diminution in the quantity of his

food, while at the same time he filled the house with a piteous wailing cry,

which no person could hear without feeling for the poor captive. Unable to

resist his appeals, I give him his release; but when this was attained he seemed

very careless of availing himself of it. Having perched upon the top of a tree

in front of the house, he arranged his feathers, and looked about him for a

short time. He then alighted by the door, and I was at last obliged to drive

him away, lest some accident should befall him.

"These birds are subject to a curious disease, which I have never seen in

any other. Irregularly shaped whitish masses are formed upon the legs and feet.

To the eye these lumps appear not unlike pieces of lime; but when broken, the

interior presents a congeries of minute cells, as regularly and beautifully

formed as those of a honey-comb. Sometimes, though rarely, I have seen the

whole of the legs and feet covered with this substance, and when the crust has

broken, the bone was bare, and the sinews seemed almost altogether to have lost

the power of moving the feet. An acquaintance of mine kept one of these birds

during the summer months. It became quite tame, but at last it lost the power

of its legs and died. By this person I was informed that his Grosbeak usually

sang during a thunder-storm, or when rain was falling on the house."

While in the State of Maine, I observed that these birds, when travelling,

fly in silence, and at a considerable height above the trees. They alight on

the topmost branches, so that it is difficult to obtain them, unless one has a

remarkably good gun. But, on waiting a few minutes, you see the flock, usually

composed of seven or eight individuals, descend from branch to branch, and

betake themselves to the ground, where they pick up gravel, hop towards the

nearest pool or streamlet, and bathe by dipping their heads and scattering the

water over them, until they are quite wet; after which they fly to the branches

of low bushes, shake themselves with so much vigour as to produce a smart

rustling sound, and arrange their plumage. They then search for food among the

boughs of the taller trees.

Male, 8 1/2, 14. Female, 8 1/4, 13 1/2.

From Pennsylvania and New Jersey, in winter, eastward to Newfoundland.

Breeds from Maine northward. Common. Migratory.

PINE GROSBEAK, Loxia Enucleator, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. i. p. 80.

PYRRHULA ENUCLEATOR, Bonap. Syn., p. 119.

PYRRHULA (CORYTHUS) ENUCLEATOR, Pine Bullfinch, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer. vol. ii. p. 262.

PINE GROSBEAK or BULLFINCH, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 535.

PINE GROSBEAK, Pyrrhula Enucleator, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iv. p. 414.

Adult Male.

Bill short, robust, bulging at the base, conical, acute; upper mandible

with its dorsal outline convex, the sides convex, the edges sharp and

overlapping; lower mandible with the angle short and very broad, the dorsal line

ascending and slightly convex, the sides rounded, the edges inflected; the acute

decurved tip of the upper mandible extending considerably beyond that of the

lower; the gap-line deflected at the base.

Head rather large, ovate, flattened above; neck short; body full. Legs

short, of moderate strength; tarsus short, compressed, with six anterior

scutella, and two plates behind, forming a thin edge; toes short, the first

proportionally stout, the third much longer than the two lateral, which are

about equal; their scutella large, their lower surface with large pads covered

with prominent papillae. Claws rather long, arched, much compressed, laterally

grooved, and acute.

Plumage soft, full, rather blended, the feathers oblong. At the base of

the upper mandible are strong bristly feathers directed forwards. The wings of

moderate length; the primaries rounded, the second and third longest, and with

the fourth and fifth having their outer webs slightly cut out. Tail rather

long, emarginate, of twelve strong, broad, obliquely rounded feathers.

Bill reddish-brown. Iris hazel. Feet blackish-brown, claws black. The

general colour of the plumage is bright carmine, tinged with vermilion; the

feathers of the fore part of the back and the scapulars greyish-brown in the

centre; the bristly feathers at the base of the bill blackish-brown; the middle

of the breast, abdomen, and lower tail-coverts, light grey, the latter with a

central dusky streak. Wings blackish-brown; the primaries and their coverts

narrowly edged with reddish-white, the secondaries more broadly with white; the

secondary coverts and first row of small coverts tipped with reddish-white, the

smaller coverts edged with red.

Length to end of tail 8 1/2 inches, the end of wings 6 1/4, to end of claws

6 3/4; extent of wings 14; wing from flexure 4 3/4; tail 4; bill along the ridge

(7 1/2)/12, along the edge of lower mandible 7/12; tarsus (9 1/2)/12; first toe

(4 1/2)/12, its claw 5/12; middle toe 8/12, its claw 5/12.

Female.

The female is scarcely inferior to the male in size. The bill is dusky,

the feet as in the male. The upper part of the head and hind neck are

yellowish-brown, each feather with a central dusky streak; the rump

brownish-yellow; the rest of the upper parts light brownish-grey. Wings and

tail as in the male, the white edgings and the tips tinged with grey; the cheeks

and throat greyish-white or yellowish; the fore part and sides of the neck, the

breast, sides, and abdomen ash-grey, as are the lower tail-coverts.

Length to end of tail 8 1/4 inches, to end of wings 6 1/4, to end of claws

6 3/4; extent of wings 13 1/2; wing from flexure 4 1/2; tail 3 10/12; tarsus

(9 1/2)/12; middle toe and claw 1 1/12.

Young fully fledged.

The young, when in full plumage, resemble the female, but are more tinged

with brown.

An adult male from Boston examined. The roof of the mouth is moderately

concave, its anterior horny part with five prominent ridges; the lower mandible

deeply concave. Tongue 4 1/2 twelfths long, firm, deflected at the middle,

deeper than broad, papillate at the base, with a median groove; for the distal

half of its length, it is cased with a firm horny substance, and is then of an

oblong shape, when viewed from above, deeply concave, with two flattened

prominences at the base, the point rounded and thin, the back or lower surface

convex. This remarkable structure of the tongue appears to be intended for the

purpose of enabling the bird, when it has insinuated its bill between the scales

of a strobilus, to lay hold of the seed by pressing it against the roof of the

mandible. In the Crossbills, the tongue is nearly of the same form, but more

slender, and these birds feed in the same manner, in so far as regards the

prehension of the food. In the present species, the tongue is much strengthened

by the peculiar form of the basi-hyoid bone, to which there is appended as it

were above a thin longitudinal crest, giving it great firmness in the

perpendicular movements of the organ. The oesophagus [a b c d], Fig. 1, is two

inches 11 twelfths long, dilated on the middle of the neck so as to form a kind

of elongated dimidiate crop, 4 twelfths of an inch in diameter, projecting to

the right side, and with the trachea passing along that side of the vertebrae.

The proventriculus [c], is 8 twelfths long, somewhat bulbiform, with numerous

oblong glandules, its greatest diameter 4 1/2 twelfths. A very curious

peculiarity of the stomach [e], is, that in place of having its axis continuous

with that of the oesophagus or proventriculus, it bends to the right nearly at a

right angle. It is a very powerful gizzard, 8 1/2 twelfths long, 8 twelfths

broad, with its lateral muscles 1/4 inch thick, the lower very distinct, the

epithelium longitudinally rugous, of a light reddish colour. The duodenum,

[f, g], first curves backward to the length of 1 1/4 inches, then folds in the

usual manner, passing behind the right lobe of the liver; the intestine then

passes upwards and to the left, curves along the left side, crosses to the

right, forms about ten circumvolutions, and above the stomach terminates in the

rectum, which is 11 twelfths long. The coeca are 1 1/4 twelfths in length and

1/4 twelfth in diameter. The entire length of the intestine from the pylorus to

the anus is 31 1/2 inches (in another male 31); its greatest breadth in the

duodenum 2 1/2 twelfths, gradually contracting to 1 1/4 twelfths. Fig. 2,

represents the convoluted appearance of the intestine. The oesophagus [a b c];

the gizzard [d], turned forwards; the duodenum, [e f]; the rest of the

intestine, [g h]; the coeca, [i]; the rectum, [i j], which is much dilated at

the end.

The trachea is 2 inches 2 twelfths long, of uniform diameter, 1 1/2

twelfths broad, with about 60 rings; its muscles like those of all the other

species of the Passerinae or Fringillidae.

In a female, the oesophagus is 2 inches 10 twelfths long; the intestine 31

inches long.

In all these individuals and several others, the stomach contained a great

quantity of particles of white quartz, with remains of seeds; and in the

oesophagus of one was an oat seed entire.

Although this bird is in its habits very similar to the Crossbills, and

feeds on the same sort of food, it differs from them in the form and extent of

its crop, in having the gizzard much larger, and the intestines more than double

the length, in proportion to the size of the bird.

| Next >> |