| Family XVI. AGELAINAE. MARSH BLACK-BIRDS. GENUS II. MOLOTHRUS, Swains. COW-BIRD. |

Next >> |

Family |

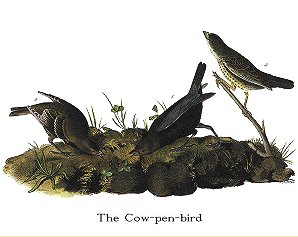

THE COW-PEN-BIRD. [Brown-headed Cowbird.] |

| Genus | MOLOTHRUS PECORIS, Gmel. [Molothrus ater.] |

The works of Nature are evidently perfect in all their parts. From the

manifestations of consummate skill everywhere displayed, we must infer that the

intellect which planned the grand scheme, is infinite in power; and even when we

observe parts or objects which to us seem unnecessary, superfluous, or useless,

it would be more consistent with the ideas which we ought to have of our own

feeble apprehension, to consider them as still perfect, to have been formed for

a purpose, and to execute their intended function than to view them as abortive

and futile attempts.

The seed is dropped on the ground. It imbibes moisture, swells, and its

latent principle of life receiving an impulse, slowly unfolds. Its radicle

shoots down into the earth, its plumule rises toward the sky. The first

leaflets appear, and as we watch its progress, we see it assuming size and

strength. Years pass on, and it still enlarges. It produces flowers and

fruits, and gives shelter to multitudes of animated beings. At length it stands

the glory of the forest, spreading abroad its huge arms, covering with its dense

foliage the wild animals that retreat to it for protection from the sun and the

rain. Centuries after its birth, the stately tree rears its green head to the

sky. At length symptoms of decay begin to manifest themselves. The branches

wither, the core dies and putrefies. Grey and shaggy lichens cover its trunk

and limbs. The Woodpecker resorts to it for the purpose of procuring the

insects which find shelter beneath its decayed bark. Blackness spreads over the

heavens, the muttering of the thunder is heard. Suddenly there comes on the ear

the rushing noise of the whirlwind, which scatters the twigs and the foliage

around, and meeting in its path the patriarch of the forest, lays him prostrate

on the ground. For years the massy trunk lies extended on the earth; but it is

seen gradually giving way. The summer's sun and the winter's frost crumble it

into dust, which goes to augment the soil. And thus has it finished its course.

Look again at the egg, dropped on its curious bed, the construction of

which has cost the parent bird many labours and anxieties. It also is a seed,

but it gives rise to a very different object. Fostered by the warmth imparted

by the anxious parent, the germ which it contains swells into life, and at

length bursting its fragile enclosure, comes tottering into existence. To

sustain the life and contribute to the development of this helpless being, the

mother issues in quest of food, which she carefully places in its open throat.

Day after day it acquires new development under the fostering care of its nurse,

until at length, invested with all the powers which Nature intended to bestow

upon it, it spreads its pinions to the breeze, and sallies forth to perform the

many offices for which it is destined.

How often have I watched over the little bird in its nest, and marked the

changes which day after day it exhibited: the unfolding of its first scanty

covering of down, the sprouting of its plumelets, the general enlargement of all

its parts! With what pleasure have I viewed the development of its colouring

and the early manifestations of its future habits!

Amid these wonderful operations of Nature, there is one which has

occasionally engaged my attention, and occupied my thoughts, ever since I first

became acquainted with the bird of which I now proceed to speak.

The Cow-bird, which in form and character is allied to the Crow Black-bird,

the Redwing, the Orchard Oriole, and other species, differs from these birds in

one important circumstance, which approximates it to the Cuckoo of Europe, a

bird entirely different in habits and appearance. Like that bird, it makes no

nest of its own, but deposits its eggs, one at a time, in the nests of other

birds, leaving them to the care of a foster-parent.

In the State of Louisiana, the Cow-pen-bird, or as it is also called, the

Cow Blackbird, or Cow Bunting, is seen only at long intervals. Some years pass

without the appearance of a single individual there. At other times immense

flocks are observed mixing with the Redwings, Crow Blackbirds and Robins,

searching about the farm-yards, the fields, and the meadows with great diligence

for food. At such times they are easily approached, and are shot in great

numbers, being considered more delicate and better flavoured than the species

with which they associate, excepting the Robin. Like the Redwings, they seek

the swamps and the margins of lakes and rivers, where they roost among the tall

sedges, flags, and other aquatic plants. When disturbed in these retreats, they

rise in a dense mass, perform various evolutions in the air, and alight again to

resume their repose. At daybreak, they return to the cultivated parts of the

country to search for food. In Georgia and South Carolina, they occur in great

abundance every winter. Some also spend the winter in Virginia and Maryland, as

well as in the States of Kentucky and Indiana, where I have observed them

lingering about farm-houses and cow-pens during severe weather. Great flocks,

however, retire much farther south. I have seen many of these birds passing

high in the air, at mid-day, in the month of October, pursuing their course

steadily, as if bent upon a long journey.

The Cow-pen-bird, after passing the winter in the Southern States, or in

regions nearer the equator, makes its appearance in the Middle States about the

end of March or beginning of April, arriving in small parties. Their flight is

performed chiefly under night; and during the day they are seen resting on the

trees, or frequenting the banks of streams in quest of food. They continue to

be seen in small flocks until the beginning of June, when they disappear, the

various flocks having successively passed northward.

Its flight is similar to that of the Redwing, with which it frequently

associates in its rambles. During spring and summer it feeds on insects, larvae

and worms, frequenting the cornfields, meadows and open places.

The males and females arrive together; but contrary to the general practice

among the feathered tribes, these birds do not pair. The males seem to regard

the females with little interest. The numberless acts of endearment, the many

carrollings, joyous flights, and bursts of ecstatic feeling, which other birds

display at the commencement of the breeding season, are entirely dispensed with.

When a particular intimacy takes place between two individuals of different

sexes, it soon ceases, and the same individuals mate with others. The sexual

attachment intended for the benefit of the young brood does not take place,

because in this species the young are not to be reared by their parents, but to

be left to the care of birds of other kinds. The Cow-pen Buntings, in fact,

like some unnatural parents of our own race, send out their progeny to be

nursed.

When the female is about to deposit her eggs, she is observed to leave her

companions, and perch upon a tree or fence, assuming an appearance of

uneasiness. Her object is to observe other birds while engaged in constructing

their nests. Should she not from this position discover a nest, she moves off

and flies from tree to tree, until at length, having found a suitable repository

for her egg, she waits for a proper opportunity, drops it, flies off, and

returns in exultation to her companions.

The birds in whose nests the eggs of the Cow Bunting are thus deposited,

are all smaller than itself. That which is most frequently favoured with the

unwelcome gift is the Maryland Yellow-throat. The other species in which I have

found the egg of the Cow-bird are the Chipping Sparrow, the Blue-bird, the

Yellow-bird, several Fly-catchers, especially the Blue-grey and the White-eyed,

and the Golden-crowned Thrush. The nests of these birds are very different in

form, size and materials, as well as in position, some being placed high on

trees, others in low bushes, and that of the Thrush on the ground.

It is also a very remarkable circumstance, that although the Cow-bird is

larger than the species in the nests of which it deposits its eggs, the eggs

themselves are not much superior in size to those of their intended

foster-parents. This is equally the case with the European Cuckoo, which

selects, for the purpose of depositing its egg, the nest of the Titlark,

Hedge-Sparrow, or some other small bird. And here, as in so many other cases,

may we observe the adaptation of means to ends which nature has so admirably

made. The egg of the Cuckoo, in fact, is not so large as that of the Skylark, a

bird which, to the other, hardly bears the proportion of one to six. The

intention here has not been by a similarity in size and coloring, to deceive the

bird in whose nest the egg, is placed, for, on all occasions, the individuals on

which the gift have been bestowed, receive it unwillingly, and, in fact,

manifest great alarm and resentment. On the contrary, the object has been to

secure the development of the embryo, by adapting the size of the egg to the

capability of imparting heat to it.

Should the Cow-bird deposit its egg in a nest newly finished, and as yet

empty, the owners of the nest not unfrequently desert it; but, when they have

already deposited one or more eggs, they generally continue their attachment to

it. There is reason for believing, however, that, on all occasions, they are

aware of the intrusion that has been effected.

The Cow-bird never deposits more than one egg in a nest, although it is

probable it thus leaves several in different nests, especially when we consider

the vast numbers of the species that are to be seen on their return southward.

It does not make a forcible entrance, but watches its opportunity, and when it

finds the nest deserted by its guardians, slips to it like one bent on the

accomplishment of some discreditable project. When the female returns, and

finds in her nest an egg which she immediately perceives to be different from

her own, she leaves the nest, and perches on a branch near it, returns and

retires several times in succession, flies off, calling loudly for her mate, who

soon makes his appearance, manifesting great anxiety at the distress of his

spouse. They visit the nest together, retire from it, and continue chattering

for a considerable time. Nevertheless, the obnoxious egg retains its position,

the bird continues to deposit its eggs, and incubation takes place as usual.

The egg of the Cow-bird is of a regular oval form, pale greyish-blue, sprinkled

with umber-brown dots and short streaks, which are more numerous at the larger

end.

Incubation has been continued for nearly a fortnight, and the young

Cow-bird bursts the shell. Another remarkable occurrence now takes place. The

eggs of the foster-bird are yet unhatched, and soon after disappear. In every

case the Cow-bird's egg is the first hatched, and herein also is manifested the

wisdom of Nature; for the parent-birds finding a helpless object, for whose

subsistence it behoves them to provide, fly off to procure food for it. The

other eggs are thus neglected, and the chicks which they contain necessarily

perish. Birds have probably the means of knowing an addle egg, for, when any

such remain after the hatching of the others, they always remove them from the

nest; and, in the present case, the remaining eggs are soon removed, and may

sometimes be seen strewn about in the vicinity of the nest. In the case of the

Cuckoo matters are differently managed, for the young bird of that species very

ungratefully jostles out of the nest all his foster-brothers and sisters, that

he may have room enough for himself. If we are fond of admiring the wisdom of

Nature, we ought to mingle reason with our admiration; and here we might be

tempted to suspect her not so wise as we had imagined, for why should the poor

Yellow-throat have been put to the trouble of laying all these eggs, if they

are, after all, to produce nothing? This is a mystery to me; nevertheless, my

belief in the wisdom of Nature is not staggered by it.

As the young Cow-bird grows up, its foster-parents provide for it with

great assiduity, and manifest all the concern and uneasiness at the intrusion of

a stranger, that they would do were their own offspring under their charge.

When fully fledged, the young bird is of a sooty-brown colour. Long after it

has left the nest, it continues to be fed by its affectionate guardians, until

it is at length able to provide for itself.

Towards the end of September, the old and young Cow-birds congregate in

vast numbers, and are seen wending their way southward, sometimes by themselves,

more frequently intermingled with other species, such as the Purple Grakles and

the Redwings, which they join in their plundering expeditions. They are to be

seen in the Middle States until near the end of October, although unusually

severe weather sometimes forces them southward at an earlier period.

This species derives its name from the circumstance of its frequenting

cow-pens. In this respect it greatly resembles the European Starling. Like

that bird it follows the cattle in the fields, often alights on their backs, and

may be seen diligently searching for worms and larvae among their dung. In

spring, the cattle in many parts of the United States are much infested with

intestinal worms, which they pass in great quantities, and on these the Cow-bird

frequently makes a delicious repast.

It has no song properly so called, but utters a low muttering sort of

chuckle, in performing which, it is seen to swell out its throat, and move the

feathers there in succession, in a manner very much resembling that of the

European Starling.

The young bird from which I made the present figure was sent to me by my

friend THOMAS NUTTALL, Esq., through Dr. TRUDEAU. It is the same as that

described by the former gentleman under the name of "Ambiguous Sparrow,

Fringilla ambigua," at p. 485 of his Manual of the Ornithology of the United

States and of Canada. On inspecting it, however, I at once felt convinced that

it was nothing else than a young Cow-pen-bird, scarcely fledged, it having been

found "in the early part of the summer of 1830." With the view, therefore, of

preventing further mistakes I thought it well to figure it.

It is in the habit of retiring to rest and spending the night on the reeds

bordering ponds in unfrequented places, as are the rest of our "Blackbirds."

One of their roosting-places is alluded to by my young friend Dr. THOMAS M.

BREWER, Of Boston, in a letter, as follows:--"The four Cow Blackbirds which I

obtained the last day you were with us, were shot in the marshes of Fresh Pond,

by Mr. CHARLES E. WARE. I went to the pond a day or two after, but was unable

to procure any, as it was so late in the afternoon that they were all gone to

roost in the reeds, and I could see them in thousands, nay, tens of thousands.

The rustling noise they made was truly deafening."

"You can hardly expect," continues Dr. BREWER, "that I should add any thing

to the detailed account which I have already given you of this bird, and yet I

cannot but think that much remains to be told respecting its habits. Many

circumstances relative to its history still solicit the attention of the

inquisitive naturalist, but of these I am not at present qualified to speak.

There is one subject, however, on which I may offer a few remarks, namely, its

laying in the nest of Fringilla tristis. WILSON first asserted that it burdens

that species with the charge of its egg; but Mr. NUTTALL denies the possibility

of such an occurrence, on the ground that the Cow Blackbirds are not present at

the time when the Goldfinch is breeding. For this, however, Mr. ORD takes him

to task, and states that he has himself seen a Cow Bunting's egg in the nest of

the bird in question. Now, it appears to me, that when we consider how

extremely incorrect WILSON'S description of the nest and eggs of Fringilla

tristis is, very little reliance can be placed upon his assertion in this case.

I can add my testimony to the authority of Mr. NUTTALL as to the absence of the

Cow-bird from this State while the Goldfinch is breeding here. The former

leaves Massachusetts before the first of July, sometimes earlier, indeed by the

middle of June, and never lays on its return late in September. I have never

found the nest of the Goldfinch before the 7th of August, although Mr. NUTTALL

states that it breeds in July. But then Mr. ORD says that he has himself

witnessed the occurrence. I would be the last person to doubt that gentleman's

veracity, nor have I the slightest idea that he would wilfully make a

mistatement; yet I cannot help thinking that in this matter he has been

deceived. Perhaps he is correct: but, in that case, he must either have in his

part of the country a distinct species of Goldfinch, or its habits and those of

the Cow-bird must be very different there from what they are here. At all

events, it is utterly impossible that such an occurrence could ever have taken

place in Massachusetts. I think, therefore, that the Goldfinch should be struck

from the list of those species in the nests of which the Cow-bird lays. On the

other hand, Sylvia Blackburniae and S. vermivora are to be added to it. The

Cow-bird is very common at Boston, having its eggs in the nests of the

White-eyed Vireo, the Red-eyed, and any other that it chances to encounter, and

departing in autumn for the south.

COW BUNTING, Emberiza pecoris, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. ii. p. 145.

ICTERUS PECORIS, Bonap. Syn., p. 53.

MOLOTHRUSS PECORIS, Cow-pen or Cuckoo Bunt, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii. p. 277.

COW TROOPIAL, or Cow Blackbird, Icterus pecoris, Nutt. Man., vol. i.p. 178.

COW-PEN-BIRD, Icterus pecoris, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. i. p. 493; vol. v.p. 233, 490.

Male with the head and neck sooty-brown, the body black, glossed with

green, the fore part of the back with blue. Female considerably smaller,

greyish-brown, the lower parts lighter. Young with the upper parts

greyish-brown, the quills and tail darker; wing-coverts and secondary quills

narrowly edged with light brown, primaries with whitish; lower parts dull

yellowish-white, the sides marked with a series of dark brown pointed spots.

Male, 7, 11 1/2.

Dispersed from Texas northward to lat. 68 degrees, and throughout the

United States. Great numbers winter in the Southern States.

An adult male of this species preserved in spirits presents the following

characters. The roof of the mouth has three longitudinal ridges anteriorly, the

middle ridge terminated by a soft prominence, similar to that of the Buntings,

behind which the palate descends in the same manner as in them. The posterior

aperture of the nares is oblong, with an anterior slit. The tongue is 7

twelfths long, fleshy, tapering, flat above, horny towards the end, and pointed.

The oesophagus, which is 3 1/4 inches long, passes along the right side of the

neck, accompanied by the trachea; its diameter at the commencement is 4

twelfths, but it immediately dilates into a crop, which extends to the length of

1 1/2 inches, its greatest width being 1/2 inch; it then contracts to 1/4 inch,

and enters the thorax. The proventriculus measures 4 1/2 twelfths broad. The

stomach is a strong muscular gizzard, 9 twelfths long, 7 1/2 twelfths broad, a

little compressed; the lateral muscles large and distinct; the epithelium tough,

longitudinally rugous, and of a reddish-brown colour. The contents of the

stomach are grains of wheat. The intestine is rather short, and of moderate

diameter, being 9 1/2 inches long, and varying from 2 twelfths to 1 1/2 twelfths

in breadth; the diameter of the rectum 2 1/2 twelfths, being the same as that of

the gut immediately before it; and there is scarcely any distinct cloaca, the

width of that part being not more than 4 twelfths. The coeca, 1 inch distant

from the extremity, are 3 twelfths long, 1/2 twelfth in diameter.

The trachea is 2 inches 2 twelfths long, rather wide in proportion to the

size of the bird, although not more than 11 twelfths in diameter. The rings are

58; the bronchial half rings about 15. The lateral muscles are moderate; the

sterno-tracheal extremely slender. There are four pairs of inferior laryngeal

muscles, as in all the singing-birds, whether thick-billed or not.

The digestive organs of this bird are in all respects precisely similar to

those of the Finches, Grosbeaks, Buntings, and other allied genera.

The oesophagus, [a b c d], is considerably dilated on the neck; the

stomach, [e], is a strong muscular gizzard, having the lateral muscles large and

distinct, the lower prominent, the epithelium longitudinally rugous. The

intestine, of which the commencement only is here represented, [f g], is rather

short and of moderate width. The coeca are an inch distant from the extremity,

and about a quarter of an inch in length; and the rectum forms only a slight

dilatation in place of a cloaca.

| Next >> |