| Family XVIII. CORVINAE. CROWS. GENUS III. GARRULUS, Briss. JAY. |

Next >> |

Family |

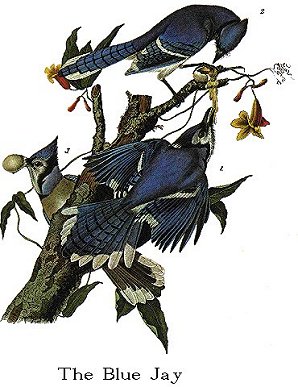

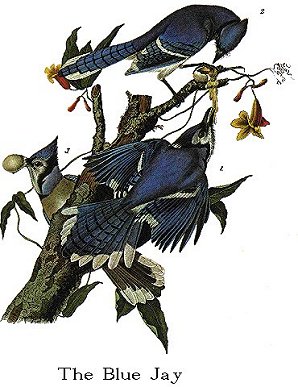

THE BLUE JAY. [Blue Jay.] |

| Genus | GARRULUS CRISTATUS, Linn. [Cyanocitta cristata.] |

Reader, look at the plate in which are represented three individuals of

this beautiful species,--rogues though they be, and thieves, as I would call

them, were it fit for me to pass judgment on their actions. See how each is

enjoying the fruits of his knavery, sucking the egg which he has pilfered from

the nest of some innocent Dove or harmless Partridge! Who could imagine that a

form so graceful, arrayed by nature in a garb so resplendent, should harbour so

much mischief;--that selfishness, duplicity, and malice should form the moral

accompaniments of so much physical perfection! Yet so it is, and how like

beings of a much higher order, are these gay deceivers! Aye, I could write you

a whole chapter on this subject, were not my task of a different nature.

The Blue Jay is one of those birds that are found capable of subsisting in

cold as well as in warm climates. It occurs as far north as the Canadas, where

it makes occasional attacks upon the corn cribs of the farmers, and it is found

in the most southern portions of the United States, where it abounds during the

winter. Every where it manifests the same mischievous disposition. It imitates

the cry of the Sparrow Hawk so perfectly, that the little birds in the

neighbourhood hurry into the thick coverts, to avoid what they believe to be the

attack of that marauder. It robs every nest it can find, sucks the eggs like

the Crow, or tears to pieces and devours the young birds. A friend once wounded

a Grouse (Tetrao umbellus), and marked the direction which it followed, but had

not proceeded two hundred yards in pursuit, when he heard something fluttering

in the bushes, and found his bird belaboured by two Blue Jays, who were picking

out its eyes. The same person once put a Flying Squirrel into the cage of one

of these birds, merely to preserve it for one night; but on looking into the

cage about eleven o'clock next day, he found the animal partly eaten. A Blue

Jay at Charleston destroyed all the birds of an aviary. One after another had

been killed, and the rats were supposed to have been the culprits, but no

crevice could be seen large enough to admit one. Then the mice were accused,

and war was waged against them, but still the birds continued to be killed;

first the smaller, then the larger, until at length the Keywest Pigeons; when

it was discovered that a Jay which had been raised in the aviary was the

depredator. He was taken out, and placed in a cage, with a quantity of corn,

flour and several small birds which he had just killed. The birds he soon

devoured, but the flour he would not condescend to eat, and refusing every other

kind of food soon died. In the north, it is fond of ripe chestnuts, and in

visiting the trees is sure to select the choicest. When these fail, it attacks

the beech nuts, acorns, pears, apples, and green corn.

While at Louisville, in Kentucky, in the winter of 1830, I purchased

twenty-five of these birds, at the rate of 61 cents each, which I shipped to New

Orleans, and afterwards to Liverpool, with the view of turning them out in the

English woods. They were caught in common traps, baited with maize, and were

brought to me one after another as soon as secured. In Placing them in the

large cage which I had ordered for the purpose of sending them abroad, I was

surprised to see how cowardly each newly caught bird was when introduced to his

brethren, who, on being in the cage a day or two, were as gay and frolicsome as

if at liberty in the woods. The new comer, on the contrary, would run into a

corner, place his head almost in a perpendicular position, and remain silent and

sulky, with an appearance of stupidity quite foreign to his nature. He would

suffer all the rest to walk over him and trample him down, without ever changing

his position. If corn or fruit was presented to him, or even placed close to

his bill, he would not so much as look at it. If touched with the hand, he

would cower, lie down on his side, and remain motionless. The next day,

however, things were altered: he was again a Jay, taking up corn, placing it

between his feet, hammering it with his bill, splitting the grain, picking out

the kernel, and dropping the divided husks. When the cage was filled, it was

amusing to listen to their hammering; all mounted on their perch side by side,

each pecking at a grain of maize, like so many blacksmiths paid by the piece.

They drank a great deal, eat broken pacan nuts, grapes, dried fruits of all

sorts, and especially fresh beef, of which they were extremely fond, roosted

very peaceably close together, and were very pleasing pets. Now and then one

would utter a cry of alarm, when instantly all would leap and fly about as if

greatly concerned, making as much ado as if their most inveterate enemy had been

in the midst of them. They bore the passage to Europe pretty well, and most of

them reached Liverpool in good health; but a few days after their arrival, a

disease occasioned by insects adhering to every part of their body, made such

progress that some died every day. Many remedies were tried in vain, and only

one individual reached London. The insects had so multiplied on it, that I

immersed it in an infusion of tobacco, which, however, killed it in a few hours.

On advancing north, I observed that as soon as the Canada Jay made its

appearance, the Blue Jay became more and more rare; not an individual did any of

our party observe in Newfoundland or Labrador, during our stay there. On

landing a few miles from Pictou, on the 22nd of August, 1833, after an absence

of several months from the United States, the voice of a Blue Jay sounded

melodious to me, and the sight of a Humming-bird quite filled my heart with

delight.

These Jays are plentiful in all parts of the United States. In Louisiana,

they are so abundant as to prove a nuisance to the farmers, picking the newly

planted corn, the peas, and the sweet potatoes, attacking every fruit tree, and

even destroying the eggs of pigeons and domestic fowls. The planters are in the

habit of occasionally soaking some corn in a solution of arsenic, and scattering

the seeds over the ground, in consequence of which many Jays are found dead

about the fields and gardens.

The Blue Jay is extremely expert in discovering a fox, a racoon, or any

other quadruped hostile to birds, and will follow it, emitting a loud noise, as

if desirous of bringing every Jay or Crow to its assistance. It acts in the

same manner towards Owls, and even on some occasions towards Hawks.

This species breeds in all parts of the United States, from Louisiana to

Maine, and from the Upper Missouri to the coast of the Atlantic. In South

Carolina it seems to prefer for this purpose the live oak trees. In the lower

parts of the Floridas it gives place in a great measure to the Florida Jay; nor

did I meet with a single individual in the Keys of that peninsula. In

Louisiana, it breeds near the planter's house, in the upper parts of the trees

growing in the avenues, or even in the yards, and generally at a greater height

than in the Middle States, where it is comparatively shy. It sometimes takes

possession of the old or abandoned nest of a Crow or Cuckoo. In the Southern

States, from Louisiana to Maryland, it breeds twice every year; but to the

eastward of the latter State seldom more than once. Although it occurs in all

places from the sea-shore to the mountainous districts, it seems more abundant

in the latter. The nest is composed of twigs and other coarse materials, lined

with fibrous roots. The eggs are four or five, of a dull olive colour, spotted

with brown.

The Blue Jay is truly omnivorous, feeding indiscriminately on all sorts of

flesh, seeds, and insects. He is more tyrannical than brave, and, like most

boasters, domineers over the feeble, dreads the strong, and flies even from his

equals. In many cases in fact, he is a downright coward. The Cardinal Grosbeak

will challenge him, and beat him off the ground. The Red Thrush, the

Mocking-bird, and many others, although inferior in strength, never allow him to

approach their nest with impunity; and the Jay, to be even with them, creeps

silently to it in their absence, and devours their eggs and young whenever he

finds an opportunity. I have seen one go its round from one nest to another

every day, and suck the newly laid eggs of the different birds in the

neighbourhood, with as much regularity and composure as a physician would call

on his patients. I have also witnessed the sad disappointment it experienced,

when, on returning to its own home, it found its mate in the jaws of a snake,

the nest upset, and the eggs all gone. I have thought more than once on such

occasions that, like all great culprits, when brought to a sense of their

enormities, it evinced a strong feeling of remorse. While at Charleston, in

November 1833, Dr. WILSON of that city told me that on opening a division of his

aviary, a Mocking-bird that he had kept for three years, flew at another and

killed it, after which it destroyed several Blue Jays, which he had been keeping

for me some months in an adjoining compartment.

The Blue Jay seeks for its food with great diligence at all times, but more

especially during the period of its migration. At such a time, wherever there

are chinquapins, wild chestnuts, acorns, or grapes, flocks will be seen to

alight on the topmost branches of these trees, disperse, and engage with great

vigour in detaching the fruit. Those that fall are picked up from the ground,

and carried into a chink in the bark, the splinters of a fence rail, or firmly

held under foot on a branch, and hammered with the bill until the kernel be

procured.

As if for the purpose of gleaning the country in this manner, the Blue Jay

migrates from one part to another during the day only. A person travelling or

hunting by night, may now and then disturb the repose of a Jay, which in its

terror sounds an alarm that is instantly responded to by all its surrounding

travelling companions, and their multiplied cries make the woods resound far and

near. While migrating, they seldom fly to any great distance at a time without

alighting, for like true rangers they ransack and minutely inspect every portion

of the woods, the fields, the orchards, and even the gardens of the farmers and

planters. Always exceedingly garrulous, they may easily be followed to any

distance, and the more they are chased the more noisy do they become, unless a

Hawk happen to pass suddenly near them, when they are instantly struck dumb,

and, as if ever conscious of deserving punishment, either remain motionless for

awhile, or sneak off silently into the closest thickets, where they remain

concealed as long as their dangerous enemy is near.

During the winter months they collect in large numbers about the

plantations of the Southern States, approach the houses and barns, attend the

feeding of the poultry, as well as of the cattle and horses in their separate

pens, in company with the Cardinal Grosbeak, the Towhe Bunting, the Cow Bunting,

the Starlings and Grakles, pick up every grain of loose corn they can find,

search amid the droppings of horses along the roads, and enter the corn cribs,

where many are caught by the cat and the sons of the farmer. Their movements on

the wing are exceedingly graceful, and as they pass from one tree to another,

their expanded wings and tail, exhibiting all the beauty of their graceful form

and lovely tints, never fail to delight the observer.

Although this species proceeds up the Missouri river to the eastern

declivities of the Rocky Mountains, it is not found on the Columbia. Dr.

RICHARDSON says that it "visits the Fur Countries, in summer, up to the 56th

parallel, but seldom approaches the shores of Hudson's Bay." He is, however,

mistaken when he says that "it frequents the Southern States only in winter;"

for it is found there at all seasons, and breeds in every district of them, as

well as in the Texas, where I found it, although it was rare. The eggs measure

an inch and half an eighth in length, and seven-eighths in breadth.

BLUE JAY, Corvus cristatus, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. i. p. 2.

CORVUS CRISTATUS, Bonap. Syn., p. 58.

GARRULUS CRISTATUS, Blue Jay, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii.p. 293.

BLUE JAY, Corvus cristatus, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. ii. p. 11; vol. v.p. 475.

Feathers of the head elongated, oblong; tail much rounded. Upper parts

light purplish-blue; wings and tail ultramarine, secondaries, their coverts, and

tail-feathers barred with black, and tipped with white; a narrow band margining

the forehead, loral space, and a band round the neck, black; throat and cheeks

bluish-white; lower parts greyish-white, tinged with brown.

Male, 12, 14.

Breeds from Texas eastward and northward to the Fur Countries, and as far

as the bases of the Rocky Mountains. Abundant. Resident in the Middle,

Interior, and Southern States.

The roof of the mouth is rather flat, anteriorly with three ridges; the lower

mandible moderately concave with a median ridge; posterior aperture of nares linear,

8 twelfths long, with the edges papillate; width of mouth 7 1/2 twelfths. The tongue

is 9 1/2 twelfths long, emarginate and papillate at the base, flat above, horny toward

the end, with the tip slit and lacerated. The oesophagus, [a b c], 3 1/4 inches long, 6 twelfths wide at the commencement, but suddenly tapering to 3 twelfths. The lobes of the liver are very unequal, the right being 1 inch 2 twelfths in length, the other 9 twelfths. The stomach, [c d e], is very large, of a broadly elliptical, compressed form, 1 inch in length,

10 twelfths in breadth; its lateral muscles of considerable thickness, the left

being 4 twelfths; the tendons large; the epithelium very dense, tough, rugous,

of a dark brown colour. It is filled with remains of insects and mineral

substances. The intestine, [e f g h i], is 16 1/2 inches long, from 4 twelfths

to 2 1/2 twelfths in width; the coeca, [h], 3 twelfths long, 1/2 twelfth wide,

and 1 1/4 inches distant from the extremity; the cloaca, [i], ovate, 8 twelfths

in breadth.

The trachea is 2 inches 5 twelfths long, considerably flattened toward the

lower part; its rings 56 in number, rather broad, and well ossified, with two

additional dimidiate rings; the bronchi of moderate size, with 12 half rings.

The lateral muscles are rather slender; there are four pairs of inferior

laryngeal muscles.

THE TRUMPET-FLOWER.

BIGNONIA RADICANS. Pursh, Flor. Amer., vol. ii. p. 420.

| Next >> |