| Family XXIV. TROCHILINAE. HUMMING-BIRDS. GENUS I. Linn. TROCHILUS HUMMING-BIRD. |

Next >> |

Family |

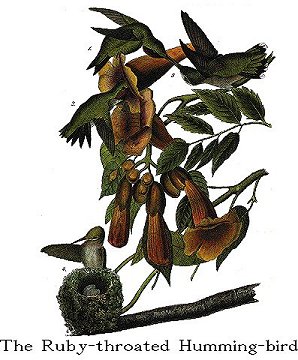

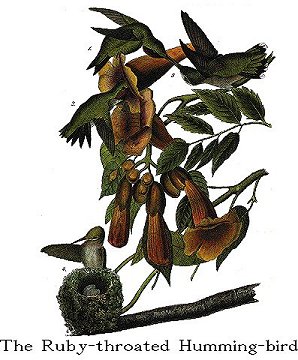

THE RUBY-THROATED HUMMING-BIRD. [Ruby-throated Hummingbird.] |

| Genus | TROCHILUS COLUBRIS, Linn. [Archilochus colubris.] |

Where is the person who, on seeing this lovely little creature moving on

humming winglets through the air, suspended as if by magic in it, flitting from

one flower to another, with motions as graceful as they are light and airy,

pursuing its course over our extensive continent, and yielding new delights

wherever it is seen;--where is the person, I ask of you, kind reader, who, on

observing this glittering fragment of the rainbow, would not pause, admire, and

instantly turn his mind with reverence toward the Almighty Creator, the wonders

of whose hand we at every step discover, and of whose sublime conceptions we

everywhere observe the manifestations in his admirable system of

creation?--There breathes not such a person; so kindly have we all been blessed

with that intuitive and noble feeling--admiration!

No sooner has the returning sun again introduced the vernal season, and

caused millions of plants to expand their leaves and blossoms to his genial

beams, than the little Humming-bird is seen advancing on fairy wings, carefully

visiting every opening flower-cup, and, like a curious florist, removing from

each the injurious insects that otherwise would ere long cause their beauteous

petals to droop and decay. Poised in the air, it is observed peeping

cautiously, and with sparkling eye, into their innermost recesses, whilst the

etherial motions of its pinions, so rapid and so light, appear to fan and cool

the flower, without injuring its fragile texture, and produce a delightful

murmuring sound, well adapted for lulling the insects to repose. Then is the

moment for the Humming-bird to secure them. Its long delicate bill enters the

cup of the flower, and the protruded double-tubed tongue, delicately sensible,

and imbued with a glutinous saliva, touches each insect in succession, and draws

it from its lurking place, to be instantly swallowed. All this is done in a

moment, and the bird, as it leaves the flower, sips so small a portion of its

liquid honey, that the theft, we may suppose, is looked upon with a grateful

feeling by the flower, which is thus kindly relieved from the attacks of her

destroyers.

The prairies, the fields, the orchards and gardens, nay, the deepest shades

of the forests, are all visited in their turn, and everywhere the little bird

meets with pleasure and with food. Its gorgeous throat in beauty and brilliancy

baffles all competition. Now it glows with a fiery hue, and again it is changed

to the deepest velvety black. The upper parts of its delicate body are of

resplendent changing green; and it throws itself through the air with a

swiftness and vivacity hardly conceivable. It moves from one flower to another

like a gleam of light, upwards, downwards, to the right, and to the left. In

this manner, it searches the extreme northern portions of our country, following

with great precaution the advances of the season, and retreats with equal care

at the approach of autumn.

I wish it were in my power at this moment to impart to you, kind reader,

the pleasures which I have felt whilst watching the movements, and viewing the

manifestation of feelings displayed by a single pair of these most favourite

little creatures, when engaged in the demonstration of their love to each

other:--how the male swells his plumage and throat, and, dancing on the wing,

whirls around the delicate female; how quickly he dives towards a flower, and

returns with a loaded bill, which he offers to her to whom alone he feels

desirous of being united; how full of ecstacy he seems to be when his caresses

are kindly received; how his little wings fan her, as they fan the flowers, and

he transfers to her bill the insect and the honey which he has procured with a

view to please her; how these attentions are received with apparent

satisfaction; how, soon after, the blissful compact is sealed; how, then, the

courage and care of the male are redoubled; how he even dares to give chase to

the Tyrant Fly-catcher, hurries the Blue-bird and the Martin to their boxes; and

how, on sounding pinions, he joyously returns to the side of his lovely mate.

Reader, all these proofs of the sincerity, fidelity, and courage, with which the

male assures his mate of the care he will take of her while sitting on her nest,

may be seen, and have been seen, but cannot be portrayed or described.

Could you, kind reader, cast a momentary glance on the nest of the

Humming-bird, and see, as I have seen, the newly-hatched pair of young, little

larger than humble-bees, naked, blind, and so feeble as scarcely to be able to

raise their little bill to receive food from the parents; and could you see

those parents, full of anxiety and fear, passing and repassing within a few

inches of your face, alighting on a twig not more than a yard from your body,

waiting the result of your unwelcome visit in a state of the utmost despair,

--you could not fail to be impressed with the deepest pangs which parental

affection feels on the unexpected death of a cherished child. Then how pleasing

is it, on your leaving the spot, to see the returning hope of the parents, when,

after examining the nest, they find their nurslings untouched! You might then

judge how pleasing it is to a mother of another kind, to hear the physician who

has attended her sick child assure her that the crisis is over, and that her

babe is saved. These are the scenes best fitted to enable us to partake of

sorrow and joy, and to determine every one who views them to make it his study

to contribute to the happiness of others, and to refrain from wantonly or

maliciously giving them pain.

I have seen Humming-birds in Louisiana as early as the 10th of March.

Their appearance in that State varies, however, as much as in any other, it

being sometimes a fortnight later, or, although rarely, a few days earlier. In

the Middle Districts, they seldom arrive before the 15th of April, more usually

the beginning of May. I have not been able to assure myself whether they

migrate during the day or by night, but am inclined to think the latter the

case, as they seem to be busily feeding at all times of the day, which would not

be the case had they long flights to perform at that period. They pass through

the air in long undulations, raising themselves for some distance at an angle of

about 40 degrees, and then falling in a curve; but the smallness of their size

precludes the possibility of following them farther than fifty or sixty yards

without great difficulty, even with a good glass. A person standing in a garden

by the side of a Common Althaea in bloom, will be as surprised to hear the

humming of their wings, and then see the birds themselves within a few feet of

him, as he will be astonished at the rapidity with which the little creatures

rise into the air, and are out of sight and hearing the next moment. They do

not alight on the ground, but easily settle on twigs and branches, where they

move sidewise in prettily measured steps, frequently opening and closing their

wings, pluming, shaking and arranging the whole of their apparel with neatness

and activity. They are particularly fond of spreading one wing at a time, and

passing each of the quill-feathers through their bill in its whole length, when,

if the sun is shining, the wing thus plumed is rendered extremely transparent

and light. They leave the twig without the least difficulty in an instant, and

appear to be possessed of superior powers of vision, making directly towards a

Martin or a Blue-bird when fifty or sixty yards from them, and reaching them

before they are aware of their approach. No bird seems to resist their attacks,

but they are sometimes chased by the larger kinds of humble-bees, of which they

seldom take the least notice, as their superiority of flight is sufficient to

enable them to leave these slow moving insects far behind in the short space of

a minute.

The nest of this Humming-bird is of the most delicate nature, the external

parts being formed of a light grey lichen found on the branches of trees, or on

decayed fence-rails, and so neatly arranged round the whole nest, as well as to

some distance from the spot where it is attached, as to seem part of the branch

or stem itself. These little pieces of lichen are glued together with the

saliva of the bird. The next coating consists of cottony substance, and the

innermost of silky fibres obtained from various plants, all extremely delicate

and soft. On this comfortable bed, as in contradiction to the axiom that the

smaller the species the greater the number of eggs, the female lays only two,

which are pure white and almost oval. Ten days are required for their hatching,

and the birds raise two broods in a season. In one week the young are ready to

fly, but are fed by the parents for nearly another week. They receive their

food directly from the bill of their parents, which disgorge it in the manner of

Canaries or Pigeons. It is my belief that no sooner are the young able to

provide for themselves than they associate with other broods, and perform their

migration apart from the old birds, as I have observed twenty or thirty young

Humming-birds resort to a group of trumpet-flowers, when not a single old male

was to be seen. They do not receive the full brilliancy of their colours until

the succeeding spring, although the throat of the male bird is strongly imbued

with the ruby tints before they leave us in autumn.

The Ruby-throated Humming-bird has a particular liking for such flowers as

are greatly tubular in their form. The common jimpson-weed or thorn-apple

(Datura stramonium) and the trumpet-flower (Bignonia radicans) are among the

most favoured by their visits, and after these, honeysuckle, the balsam of the

gardens, and the wild species which grows on the borders of ponds, rivulets, and

(deep ravines; but every flower, down to the wild violet, affords them a certain

portion of sustenance. Their food consists principally of insects, generally of

the coleopterous order, these, together with some equally diminutive flies,

being commonly found in their stomach. The first are procured within the

flowers, but many of the latter on wing. The Humming-bird might therefore be

looked upon as an expert fly-catcher. The nectar or honey which they sip from

the different flowers, being of itself insufficient to support them, is used

more as if to allay their thirst. I have seen many of these birds kept in

partial confinement, when they were supplied with artificial flowers made for

the purpose, in the corollas of which water with honey or sugar dissolved in it

was placed. The birds were fed on these substances exclusively, but seldom

lived many months, and on being examined after death, were found to be extremely

emaciated. Others, on the contrary, which were supplied twice a-day with fresh

flowers from the woods or garden, placed in a room with windows merely closed

with moschetto gauze-netting, through which minute insects were able to enter,

lived twelve months, at the expiration of which tune their liberty was granted

them, the person who kept them having had a long voyage to perform. The room

was kept artificially warm during the winter months, and these, in Lower

Louisiana, are seldom so cold as to produce ice. On examining an orange-tree

which had been placed in the room where these Humming-birds were kept, no

appearance of a nest was to be seen, although the birds had frequently been

observed caressing each other. Some have been occasionally kept confined in our

Middle Districts, but I have not ascertained that any one survived a winter.

The Humming-bird does not shun mankind so much as birds generally do. It

frequently approaches flowers in the windows, or even in rooms when the windows

are kept open, during the extreme heat of the day, and returns, when not

interrupted, as long as the flowers are unfaded. They are extremely abundant in

Louisiana during spring and summer, and wherever a fine plant of the

trumpet-flower is met with in the woods, one or more Humming-birds are generally

seen about it, and now and then so many as ten or twelve at a time. They are

quarrelsome, and have frequent battles in the air, especially the male birds.

Should one be feeding on a flower, and another approach it, they are both

immediately seen to rise in the air, twittering and twirling in a spiral manner

until out of sight. The conflict over, the victor immediately returns to the

flower.

If comparison might enable you, kind reader, to form some tolerably

accurate idea of their peculiar mode of flight, and their appearance when on

wing, I would say, that were both objects of the same colour, a large sphinx or

moth, when moving from one flower to another, and in a direct line, comes nearer

the Humming-bird in aspect than any other object with which I am acquainted.

Having heard several persons remark that these little creatures had been

procured, with less injury to their plumage, by shooting them with water, I was

tempted to make the experiment, having been in the habit of killing them either

with remarkably small shot, or with sand. However, finding that even when

within a few paces, I seldom brought one to the ground when I used water instead

of shot, and was moreover obliged to clean my gun after every discharge, I

abandoned the scheme, and feel confident that it can never have been used with

material advantage. I have frequently secured some by employing an insect-net,

and were this machine used with dexterity, it would afford the best means of

procuring Humming-birds.

I have represented several of these pretty and most interesting birds, in

various positions, feeding, caressing each other, or sitting on the slender

stalks of the trumpet-flower and pluming themselves. The diversity of action

and attitude thus exhibited, may, I trust, prove sufficient to present a

faithful idea of their appearance and manners. A figure of the nest you will

also find has been given; it is generally placed low, on the horizontal branch

of any kind of tree, seldom more than twenty feet from the ground. They are far

from being particular in this matter, as I have often found a nest attached by

one side only to a twig of a rose-bush, currant, or the strong stalk of a rank

weed, sometimes in the middle of the forest, at other times on the branch of an

oak, immediately over the road, and again in the garden close to the walk.

This interesting gem of the feathered tribe proceeds as far north in summer

as the 57th parallel. Dr. RICHARDSON obtained it on the plains of the

Saskatchewan, and Mr. DRUMMOND found its nest near the sources of the Elk river.

It does not occur on the Columbia river, where the Nootka Humming-bird is

abundant. A few were seen by me in Labrador, and, on the other hand, I met with

it entering the United States in crowds in the beginning of April, advancing

eastward along the shores of the Mexican Gulf. The weather having become very

cold one morning, many were picked up dead along the beaches, and those which

bore up were so benumbed as almost to suffer the members of my party to take

them with the hand. My friend Dr. BACHMAN has heard this species uttering a few

sweet notes, sometimes when perched on a twig, and at other times on wing. The

eggs measure half an inch in length by 41 lines in breadth.

HUMMING-BIRD, Trochilus Colubris, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. ii. p. 26.

TROCHILUS COLUBRIS, Bonap. Syn., p. 98.

TROCHILUS COLUBRIS, NORTHERN HUMMING-BIRD, Swains. & Rich. F. Bor. Amer.,vol. ii. p. 323.

RUBY-THROATED HUMMING-BIRD, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 588.

RUBY-THROATED HUMMING-BIRD, Trochilus colubris, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. i.p. 248; vol. v. p. 544.

Male, 3 1/4, 4 1/2.

In summer, from Texas to lat. 57 degrees, and in all intermediate districts

east of the Rocky Mountains. Common. Migratory.

Adult Male.

Bill long, straight, subulate, depressed at the base, acute; upper mandible

rounded, its edges overlapping. Nostrils basal, linear. Tongue very extensile,

filiform, divided towards the end into two filaments. Feet very short and

feeble; tarsus slender, shorter than the middle toe, partly feathered; fore toes

united at the base; claws curved, compressed, acute.

Plumage compact, imbricated above and on the throat with metallic lustre,

blended beneath. Wings long, narrow, a little incurved at the tip, the first

quill longest. Tail forked when closed, when spread even in the middle and

laterally rounded, of ten broad feathers, the outer curved inwards.

Bill and feet black. Iris of the same colour. Upper parts generally,

including the two middle tail-feathers, green, with gold reflections. Quills

and tail purplish-brown. Throat, sides of the head, and fore neck,

carmine-purple, spotted with black, varying to crimson, orange, and deep black.

Sides of the same colour as the back; the rest of the under parts greyish-white,

mixed with green.

Length 3 1/2 inches, extent of wings 4 1/4; bill along the ridge 3/4, along

the gap 5/6; tarsus 1/6, toe 1/4.

Adult Female.

The female differs from the male in wanting the brilliant patch on the

throat, which is white, as are the under parts generally, and in having the

three lateral tail-feathers tipped with the same colour.

Dimensions the same.

Young Bird.

The young birds have the under parts brownish-white, the tail tipped with

white, and are somewhat lighter in their upper parts. In autumn the young males

begin to acquire the red feathers of the throat.

On depriving a specimen of this bird of its feathers, one finds its

proportions very different from what he may have previously imagined. Thus, the

body is remarkably robust, of an ovate form, much deeper than broad, on account

of the extreme size of the crest or keel of the sternum, which is so extended as

to leave for the abdomen a space not more than a fifth of its own length. The

feet, although very small, are yet proportionally as large as those of a

Cormorant; the femur and tibia being relatively large, while the tarsus is

extremely short, and the toes of moderate size, the anterior incapable of being

widely spread, and the middle or third scarcely exceeding the two lateral; in

which respect the foot has some resemblance to that of the Swifts. The hind toe

is articulated remarkably high on the tarsus, it being placed very nearly at the

height of one-third of its length. The bones of the wings are very short; the

humerus and cubitus extremely so, although proportionally strong. The neck is

very elongated, being 10 twelfths of an inch in length, whereas the body,

including the coccyx, is only 9 twelfths. The head is rather large, depressed

in front, with a deep hollow between the eyes, which are very large, and the

bill is disproportionately elongated. The pectoral muscles are of extreme size,

exceeding by much the entire bulk of the rest of the body with the neck and

head, the height of the crest of the sternum being 4 twelfths, or nearly half

the length of the body. The body of the sternum is remarkably flat, and so thin

as to be almost perfectly transparent; it is narrow anteriorly, where it is

2 1/4 twelfths in breadth, but gradually enlarges to 4 twelfths; the posterior

edge forms a semicircle, and is destitute of notch. The pubic bones almost meet

in front, where they are cartilaginous. The heart is extraordinarily large,

occupying half the length of the cavity of the body, of an elongated conical

form, 3 1/4 twelfths long, and 2 twelfths in breadth at the base. The right

lobe of the liver is much larger than the left, the former being 5 twelfths in

length, the latter 4 twelfths.

The whole length of the head is 1 1/4 inches, of which the bill is 10

twelfths. The upper mandible is slightly concave beneath in its whole length,

the lower a little more deeply concave, the edges of both thin, those of the

lower erect and overlapped by the upper. The nostrils are covered by a very

large projecting membranous flap, feathered above.

The tongue is, to a certain extent, constructed precisely in the same manner as that of the Wood-peckers.

The basi-hyal bone is 1 1/2 twelfths long, the apo-hyal bones 2 twelfths, the

apo-hyal and cerato-hyal together 1 inch 2 twelfths, the glosso-hyal or

terminal bones 4 1/2 twelfths. There is no uro-hyal bone, any more than in the

Woodpeckers, and the glosso-hyal is double at the end. The horns of the hyoid

bone are thus greatly elongated, recurving over the occiput, near the top of

which they meet, and thence proceed directly forward, in mutual proximity,

lodged in a deep and broad groove, along the middle of the forehead, until near

the anterior part of the eye, where they terminate, fig. 3. The crura of the

lower mandible, fig. 4, do not meet until very near the tip, and from the

inner and lower surface of each near the junction or angle, there proceeds

backward a slender muscle, which is attached to the hyoid bone at the junction

of the apo-hyal and cerato-hyal, whence it proceeds all the way to the tip of

the latter, the muscle and bone being enclosed in a very delicate sheath, which

is attached to the subcutaneous cellular tissue between the nostrils. The

tongue, properly so called, moves in a sheath, as in the Woodpeckers; its length

is 10 twelfths. When it is protruded, the part beyond this at the base appears

fleshy, being covered with the membrane of the mouth forming the sheath, but the

rest of its extent is horny, and presents the appearance of two cylinders

united, with a deep groove above and another beneath, for the length of 3

twelfths, beyond which they become flattened, concave above, thin-edged and

lacerated externally, thick-edged internally, and, although lying parallel and

in contact, capable of being separated. This part, being moistened by the fluid

of the slender salivary glands, and capable of being alternately exserted and

retracted, thus forms an instrument for the prehension of small insects, similar

in so far to that of the Woodpeckers, although presenting a different

modification in its horny extremity, which is more elongated and less rigid.

All observers who have written on the tongue of the Humming-birds, have

represented it as composed of two cylindrical tubes, and the prevalent notion

has been that the bird sucks the nectar of flowers by means of these tubes. But

both ideas are incorrect. There are, it is true, two cylindrical tubes, but

they gradually taper away toward the point, and instead of being pervious form

two sheaths for the two terminal parts or shafts of the glosso-hyal portion of

the tongue, which run nearly to the tip, while there is appended to them

externally a very thin-fringed or denticulate plate of horny substance. The

bird obviously cannot suck, but it may thrust the tip of the tongue into a

fluid, and by drawing it back may thus procure a portion. It is, however, more

properly an organ for the prehension of small insects, for which it is obviously

well adapted, and being exsertile to a great extent enables the bird to reach at

minute objects deep in the tubes and nectaries of flowers. That a Humming-bird

may for a time subsist on sugar and water, or any other saccharine fluid, is

probable enough; but it is essentially an insect-hunter, and not a honey-sucker.

The oesophagus, fig. 2, is 1 inch 4 twelfths long, 1 1/2 twelfths in width at the top, but toward the lower part of the neck enlarged to 1 3/4 twelfths. On entering the thorax, it contracts to 1/3 twelfths; and the

proventriculus is 1 1/4 twelfths. The stomach is extremely small, of a roundish

or broadly elliptical form, 1 1/4 twelfths in length, and 1 twelfth in breadth.

The proventricular glands form a complete belt, 2 twelfths in breadth. The

walls of the stomach are moderately muscular; the epithelium dense, with broad

longitudinal rugae, four on one side, three on the other, and of a pale red

colour. In the stomach were fragments of small coleopterous insects. The

intestine is 2 inches 2 twelfths in length, from 1 1/4 twelfths to 1/2 twelfth

in width. It forms six curves, the duodenum returning at the distance of 3

twelfths. There are no coeca. The cloaca is very large and globular.

The trachea, fig. 1, is 9 twelfths long, being thus remarkably short on

account of its bifurcating very high on the neck, for if it were to divide at

the usual place, or just anteriorly to the base of the heart, it would be 4 1/2

twelfths longer. In this respect it differs from that of all the other birds

examined, with the exception of the Roseate Spoonbill, Platalea Ajaja, the

trachea of which is in so far similar. The bronchi are exactly 1/2 inch in

length. Until the bifurcation, the trachea passes along the right side,

afterwards directly in front. There are 50 rings to the fork; and each bronchus

has 34 rings. The breadth of the trachea at the upper part is scarcely more

than 1/2 twelfth, and at the lower part considerably less. It is much

flattened, and the rings are very narrow, cartilaginous, and placed widely

apart. The bronchial rings are similar, and differ from those of most birds in

being complete. The two bronchi lie in contact for 2 twelfths at the upper

part, being connected by a common membrane. The lateral muscles are extremely

slender. The last ring of the trachea is four times the breadth of the rest,

and has on each side a large but not very prominent mass of muscular fibres,

inserted into the first bronchial ring. This mass does not seem to be divisible

into four distinct muscles, but rather to resemble that of the Flycatchers,

although nothing certain can be stated on this point.

THE TRUMPET-FLOWER.

BIGNONIA RADICANS, Willd. Sp. Pl., vol. iii. p. 301. Pursh, Flor. Amer.,vol. ii. p. 420.

--DIDYNAMIA ANGIOSPERMIA, Linn.--BIGNONIAE, Juss.

This splendid species of bignonia, which grows in woods and on the banks of

rivers in all the Middle and Southern States, climbing on trees and bushes, is

distinguished by its pinnate leaves, with ovate, widely serrate, acuminate

leaflets, and large scarlet flowers, of which the funnel-shaped tube of the

corolla is thrice the length of the calyx. The pods are of a brown colour, from

four to seven inches long, and contain a double row of kidney-shaped light brown

seeds.

| Next >> |